Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

Connected learning explains how people can build learning pathways that connect their interests, relationships, and formal learning to lead toward future opportunities such as careers. However, most learning systems are not set up ideally for connected learning; for instance, most schools still teach disciplines as discrete units that do not connect to students’ interests outside of school. We do not yet know enough about the structure of naturally occurring connected learning ecologies that do connect youth learning across contexts and help them follow pathways toward careers and other desired outcomes. Learning more about what works well on these pathways will allow us to design connected learning environments to help more youth have access to these desired opportunities. This paper analyzes two case studies of cosplayers –hobbyists who make their own costumes of media characters to wear at fan conventions– who benefited from well-developed connected learning ecologies. Cases were drawn from a larger interview study and analyzed as compelling examples of connected learning. Important themes that emerged included relationships with and sponsorship by caring others; unique pathways that start with a difficult challenge; economic opportunities related to cosplay; and comparisons with formal school experiences. This has implications for how we can design connected learning ecologies that support all learners on unique pathways toward fulfilling futures.

1. Introduction

Learning researchers have long studied learning that takes place in authentic communities outside of schools, whether that be apprenticeships of tailors and midwives (Lave & Wenger, 1991) or rocket-building hobbyists (Azevedo, 2011). The learning that takes place within the context of extracurricular interests and hobbies is not always valued in the wider society; however, it is often viewed as less important than school learning (Lave, 2011), even when these engagements lead to additional learning opportunities and are sometimes the main way that young people learn about modern media (Barron, 2010; Jenkins, Purushotma, Weigel, Clinton, & Robison, 2006).

Connected learning (Ito & al., 2013) provides a framework that helps to conceptualize learning related to youths’ interests and relationships with others in a way that connects to future-oriented opportunities like school, higher education, careers, and political clout. However, we know very little about how learners navigate these pathways in ways that could inform the future design of learning environments. While the connected learning pathways of youth have been studied (Ito & al., 2013; Barron, 2010), we know much less about those of adults who have successfully built on their passions toward meaningful, lasting career opportunity. One way to learn more about this is to turn to retrospective case studies (Maltese & Tai, 2010) to gather adults’ histories of what worked well for them, so this can be applied to the intentional design of connected learning environments.

Cosplay (Bender, 2017) –the depiction of characters from media properties through costumes and roleplay (thus the portmanteau “cosplay”), usually at fan events like conventions– provides a case of how learning can be connected to future opportunity. As part of this hobby, cosplayers are motivated to pursue their interests, learn numerous skills, connect with mentors and networks, and enrich their experience of life. Sometimes they are fortunate enough that they are able to navigate pathways toward career opportunities that are relevant to cosplay. In these cases, cosplayers have benefited from a successfully connected learning ecology. However, the system is not always set up to legitimize the skills they are learning in their hobby, connect their school learning to it or broker career opportunities related to their skills. By looking at differences between positive connected learning in cosplay and contrasting examples of disconnected learning in schools, we may glean insights into how we can redesign learning ecologies at all levels to support unique pathways toward future opportunity for all learners, especially those who have been systematically disenfranchised by lack of access to resources or sponsors who can legitimize their out-of-school interests.

In investigating the perspectives of cosplayers on their practice, we ask: What sorts of learning pathways exist in cosplay? How can this hobby connect cosplayers to future opportunities? How can we make it –and learning ecologies in general– work better for those who do not experience connections between their extracurricular interests and future opportunities? Interviews with two cosplayers provided particularly positive examples of connected learning: with caring adults acting as sponsors and providers of resources, both were able to follow pathways toward careers relevant to their hobby, and they continue to pursue life opportunities like freelance work and mentorship of others that enrich their lives and connect to their hobby.

1.1. Connected learning

In a networked, digital world, today’s youth need ways to connect the networks, interests, and skills they are building both on and offline, in and out of school, to sites of opportunity. Legitimizing the interests and experiences of youth will help all youth to tread their own unique paths. In their 2013 report, Ito, Salen, and Sefton-Green introduced the framework of “connected learning” to describe and explain phenomena that connect various spheres of learning in a synergistic way that leads to future opportunities. Since then, Ito and others (2013) have been editing a new report that reformulates some aspects of the framework. At the time of this writing, the updated framework puts a new emphasis on connected learning environments as not only being interest-driven and participatory but also following the principles of being “production-centered”, organized around a “shared purpose”, and inclusive of opportunities for “sponsorship” and “pathway building” for youth. The new report also describes how connected learning environments thrive at the intersection of three spheres: “relationships” (e.g. with peers, family, and mentors), “interests” (e.g., in fandom), and “opportunity” (expanding beyond the original report’s focus on “academics” to include careers, political enfranchisement, etc.).

Each of these contributes uniquely to an environment that connects and legitimizes learning between different settings throughout the lifespan. Interest tends to provide the spark that leads to long-term engagement in connected learning activities (Hidi & Renninger, 2006). Production helps encourage active learning as young people make, share, remix, and reflect on artifacts (Papert, 1980). A shared purpose ensures community cohesion as everyone works toward common goals, regardless of age or other demographic differences. Relationships with peers provide a context important to youth, and relationships, in general, are important for building a shared purpose. Sponsorship, in particular, whether by providing resources or opportunities to delve further into an interest, is a special sort of relationship that will be explored further in the data. Sponsors help provide access to pathways that let youth explore interests and move toward opportunities for positive outcomes in academics, careers, and life enrichment in general. Each of these spheres and principles is applied to the context of cosplay below.

1.2. Why study pathways?

Many connected learning scholars call for studying learning pathways (Barron, 2010; Kumpulainen & Sefton-Green, 2014) to help us better understand the way learning works over the long-term (“learning lives”), and because short-term learning interventions do little good when systemic barriers prevent youth from pursuing a fulfilling future (Philip, Bang, & Jackson, 2017). This calls for studying how youth learn skills that are applicable to future goals, how mentors broker opportunities for them, and how we can facilitate this for all youth. An enriching life should be the goal of all education, going beyond the walls of the school into people’s futures as contributing members of society (Bell, Bricker, Reeve, Zimmerman, & Tzou, 2013 for another perspective on studying learning pathways). This is why a connected learning framework that reaches beyond the school day to connect it to young people’s hobbies, home lives, and jobs is particularly well suited for the study of learning pathways.

Some similar previous work has traced the paths of youth through “technobiographies” of their interest-driven, outside-of-school engagements with technology (Barron, 2010), but this work is limited to youth and possibilities for future economic opportunities, rather than adults who have achieved these opportunities. Barron, Gomez, Pinkard, and Martin (2014) reported on the Digital Youth Network, an attempt to cultivate a connected learning ecology, and traced how youth within the program became proficient with new media over time and across settings, but this also focused on youth. The original connected learning report (Ito & al., 2013) also traced the paths of several young people to illustrate examples of connected learning, but except for one, these were all youth as well. A recent survey operationalized the connected learning spheres and principles as did the present study, in order to measure youths’ experiences with connected learning, but it was again limited to youth (Maul & al., 2017). Bell and others (2013) traced STEM-related learning pathways of youth through in-depth ethnographies, identifying ways that youth engaged in STEM, such as learning about biology through health-related behaviors, over time in various settings. While this study went a long way in legitimizing youths’ outside-of-school STEM-related activity and how it connects across settings, it again focused on youth. A gap remains in tracing the paths of adults from their youthful engagement in interests, supported by relationships and sponsors, toward opportunities such as careers.

Maltese and Tai (2010) interviewed 116 graduate students and scientists to determine the experiences that sparked their interest in science. Like the present study, this research involved interviewing adults to determine retrospectively the experiences that set them on their current path toward science careers. However, it did not trace their entire path, and it focused only on science.

Recent work also tells us that most coordinators of youth-serving programs conceptualize ways for youth to connect to more advanced opportunities within their programs, rather than between programs (Akiva, Kehoe, & Schunn, 2017), implying that we need more examples of how caring adults can help youth connect interests and opportunities between settings. An analysis of connected learning pathways that led to favorable outcomes can help provide the guidance these youth-serving organizations are seeking.

1.3. Cosplay: Connected learning in action

Cosplayers vary greatly in their engagement, from those that create “closet” cosplays from combinations of ordinary clothes that could be found in a closet, to those that buy professionally made costumes, to those that make their own from scratch. They could copy a character’s outfit exactly as it appears on TV, in a movie, video game, comic, etc., or they might design an alternate version of the outfit, such as “steampunk”, a faux-Victorian aesthetic complete with trinkets that look like they are “steam-powered”. Most cosplayers wear their costumes to fan conventions (“cons”), where they can pose for pictures, meet other fans cosplaying from the same fandom, shop for goods from their favorite fandoms, and attend panels celebrating geeky topics. In this sense, cosplay is a participatory culture that both celebrates media as it is and “poaches” and reinterprets it through wearing costumes that allow fans to be the characters (Jenkins, 2012). Like other participatory cultures, cosplay is open to creative participation by all who are interested, it supports creation and sharing, it involves informal mentorship either in person or through online tutorials/resources, members believe their creations matter, and members have a social connection with each other (Jenkins & al., 2006). These all help to support the learning process in cosplay, which is robust as it is in other participatory cultures (Jenkins & al., 2006).

Cosplay fits in well with a connected learning framework, especially for those who follow a pathway involving learning how to make their costumes. It may start from an “interest” in fandom or from “relationships” with friends who wish to put together a cosplay group at a con. The skills developed and relationships built both online and offline can provide “pathways” toward “opportunities”, such as design skills applicable to a career, or meeting people who may become future business clients. Since cosplay is an expensive hobby, “sponsorship” is important, and many young cosplayers rely on parents and other caring adults to financially sponsor their first forays into cosplay by paying for materials, con attendance, etc. Sometimes these adults also provide lessons in skills needed for cosplay, like sewing or sculpting. Otherwise, cosplayers can build their pathways through online resources such as tutorials, demonstrations, and online discussion groups where they can ask questions and receive advice. The “shared purpose” of the cosplay community –to make or otherwise acquire costumes of characters to wear at fun events like cons– means that members of the community are willing to help and welcome each other, both online and in person at cons. This is a “production-centered” practice because of the production of costumes and performances “in character”.

However, not every cosplayer manages to access economic and enfranchisement opportunities through their hobby. Most environments are not set up to allow such access, even if it is desired. So while cosplay, in general, is successful at connecting interests and learning, we must study exceptional cases that also connect to economic opportunities if we wish to find principles for pathway design that can lead all youth toward such opportunities.

In approaching this research, we were guided by the following questions: What sorts of learning pathways exist in cosplay? How can this hobby connect cosplayers to future opportunities? How can we make it –and learning ecologies in general– work better for those who do not experience connections between their extracurricular interests and future opportunities?

2. Material and methods

To explore cosplayers’ pathways, the lead author was situated as an embedded ethnographer in the cosplay community as part of a research project on the math inherent in textile crafts funded by the National Science Foundation in the United States (Peppler & Gresalfi, 2014). After obtaining informed consent, ten cosplayers participating in regional fan conventions were interviewed, using a semi-structured interview protocol that asked how the participants had learned the skills needed for cosplay, what drove them to participate in this hobby, stories about particular projects, and how online and in-person communities were involved in their practice. Throughout each interview, cosplayers discussed their experiences with their current occupation, and with school, particularly focusing on math classes because of the larger math-related research project. The interview protocol was intended to determine aspects of the community and craft context that led to learning of crafts (in this case, the craft of cosplay), as well as to contrast math used in crafts with math used in school. While the interview did not ask about connected learning principles specifically, it is perhaps unsurprising that they emerged from discussions of interest-driven hobbies, relationships with a community, and academic and occupational opportunities.

The cosplayers were interviewed individually, except for one case in which three cosplayers spoke with the interviewer at the same time. Interviews took place in person, over the phone, or via video conference and lasted approximately 45 minutes to an hour. Two interviewees were male, and eight were female. They were selected through a process of convenience sampling –cosplayers the interviewer knew personally—that led to snowball sampling– friends of the first wave of cosplayers. They ranged in age from 21 to 33 at the time of the interview, and all were White Americans living in the United States.

All interviews were transcribed and reviewed by the lead author in order to identify cases of compelling connected learning pathways. In analyzing the interviews, we found that the cosplayers described cosplay as a worthwhile force in their lives and described thorough learning pathways of how they learned to cosplay and continued to engage in their hobby. For many of the cosplayers, their hobby remained disconnected from any economic opportunities like their careers. Two interviews stood out as exceptional cases of connections between cosplay and careers, from which design insights for connected learning pathways could be gleaned. These acted as models of positive deviance (Pascale, Sternin, & Sternin, 2010) and extreme cases (Flyvbjerg, 2006) that, among all the interviews, provided the most information and suggestions for how a well-developed connected learning model could be scaled, such as showing how cosplay could lead to economic opportunities. The other interviews either did not show direct connections between cosplay and careers, or, in one case, was missing crucial details due to time constraints placed on the interview. Extreme cases often provide the richest information about how a phenomenon works and thus are justified for inclusion (Flyvbjerg, 2006). This was the case here.

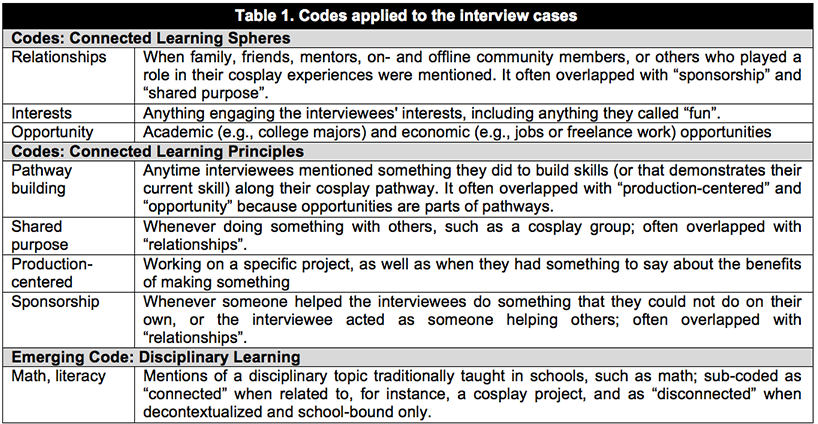

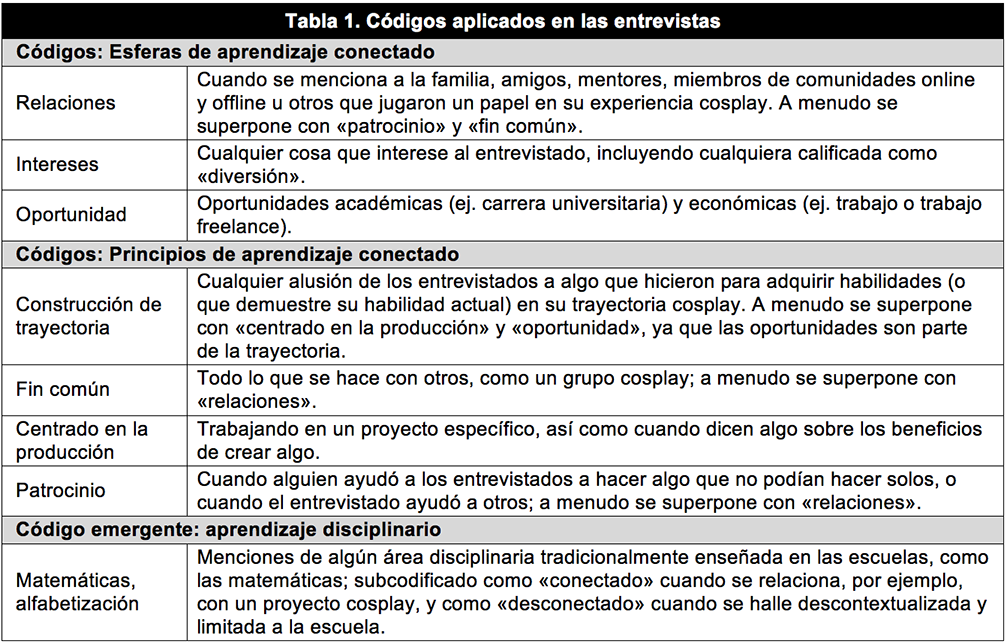

Interviews were split into analytically relevant chunks (usually a sentence or a few sentences on the same topic). Each chunk was inputted into Microsoft Excel and coded a priori according to the connected learning spheres and principles; then the data was further consolidated into themes. The coding remained open to emerging themes. Each code is described in Table 1 below.

In addition to the connected learning framework-related codes, another theme emerged related to the discussion of disciplinary topics traditionally taught in schools (e.g., math). Those instances that mentioned disciplinary learning were sub-coded as “connected” or “disconnected” to interests, projects, etc., depending on how the interviewee discussed it.

Codes were combined into themes detailed in Results below, and anecdotes and quotes related to the themes were drawn from the interviewees’ reports to illustrate design principles for making learning pathways more connected to interests, relationships, and opportunities.

3. Results

The following presents a summary of each of the two cosplay cases, followed by the themes derived from the coding of the interviews.

3.1. Introducing connected cosplay cases

Lexi (all names are pseudonyms) had been cosplaying for nine years and was 31 at the time of the interview. With her artist mother as a sponsor of learning new craft skills and her friends encouraging her to join their cosplay group, Lexi dove right into the hobby with a costume that was a big challenge to sew. Now, she uses the knowledge she gained about clothing from cosplay in her job for a large intimate-wear company. She continues to seek opportunities to express fashion creatively through designing for local fashion shows and freelance fashion consulting work. Lexi often cosplays from video games she enjoys, and almost always cosplays with a group of friends from the same series, such as when she cosplayed from the TV show “Avatar: The Last Airbender” and also helped to make costumes from the same show for non-sewers in her group. She almost always cosplays male characters, partly because it makes it less likely for men to show a romantic interest in her. As a woman who has been in a committed relationship with another woman for many years, this is a desirable outcome but also allows her to play with gender in ways she enjoys. See Figure 1 for an example of Kuja, a male video game character Lexi has cosplayed. Kuja wears a revealing costume, and Lexi delightedly reported receiving confused reactions about her gender when wearing this cosplay. For her, cosplay is “just kind of nice to step outside of yourself for a bit”.

Figure 1. Lexi as Kuja from Final Fantasy IX (left)

Tim’s interest in entertainment design was supported early by his enrollment in a performing arts middle and high school that he now, at 33 during the interview, works for as a sculpture teacher. Like Lexi, he began to cosplay in order to join friends at fan conventions and to express his love for particular characters. Now he is paying forward the sponsorship he received, and is encouraging others’ interests in art and cosplay; he lets students bring cosplay projects into his class, sometimes even brings his own to class, and allows friends to use his studio at home to work on cosplay and learn techniques from him. He is well accomplished at both sewing and prop design. Figure 1 shows one of Tim’s cosplays, that of Captain Harlock, a character from various TV shows and movies, including “Space Pirate Captain Harlock”. Tim has always loved this character, ever since he first encountered him in one of the first animes he ever watched. He described Harlock as “dark” and “mysterious” and went into great detail about how he made this “dream” costume, from molding Harlock’s gun out of silicone to attaching snaps to the cape so it will not tear. He also described the costume as “never finished”, detailing his plans to add an animatronic bird to it, to represent Harlock’s pet parrot. His passion for cosplay manifests as a continuous challenge to himself.

Figure 2. Tim as Captain Harlock from “Space Pirate Captain Harlock” and other works (right).

Results of the analysis of the two cases showed that while all aspects of the connected learning framework played a role in the participants’ paths, relationships (particularly peers and sponsors), challenging starts, and economic and enriching opportunities were particularly strong themes. Both interviewees also discussed math classes as a disconnected experience that contrasted with their experience of learning how to cosplay.

3.2. Themes3.2.1. Caring others: Friends, family, sponsors

As a combination of the codes of “relationships”, “shared purpose”, and “sponsorship”, this theme emerged as very common in the data and was consequential in motivating initial and continued engagement in cosplay. Both Lexi and Tim, like most cosplayers, got into the hobby because friends wanted them to join their cosplay group at conventions, so their relationships with peers who also shared their interests provided initial motivation. Shared interests in a fandom and the shared purpose of celebrating those interests at conventions were also catalysts for making new friends. As Tim put it, “There’s a big difference in cosplay by yourself and cosplay in a big group. It is so much more fun… Whenever you have like two or three people, and then you are like, ‘Oh hey, you are from our show,’ you grab them, and they spend the day with you; like, you are making friends the whole time”. Peers are vital to the lives of youth and young adults, and cosplayers are no exception.

Sponsorship by caring adults (Barron, Martin, Takeuchi, & Fithian, 2009) played an important role too. In Lexi’s case, her mother is an artist who always encouraged her, growing up, to learn new skills by doing, and is the one who gave Lexi her first sewing machine when she expressed interest in sewing her cosplays. Later, Lexi received sponsorship and legitimization of her interests from the realm of formal education in her Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) master’s program, where she learned how to integrate electronics into clothing. Tim received sponsorship from formal education as well, such as when he attended a performing arts school for middle and high school, where he learned costume design for theatre, and his undergraduate program in Entertainment Design, where he learned skills like resin-cast molding that he can use to make cosplay props. Beyond these formal routes, both cosplayers learned a great deal from online sources and in-person mentors.

3.2.2. Pathways: Starting big

“Pathway building” was the most common code, but an interesting finding emerged in terms of how cosplay pathways tended to begin. While all ten cosplayers followed unique pathways, a common theme that emerged across most of the interviews was that of taking on huge challenges early in the process of becoming a cosplayer. For instance, the first costume Lexi ever sewed involved sewing bias tape along the curves of an underbust corset-like garment. It was not easy; she said, “If you are ever wanting to learn how to sew, don’t do bias taping on a curve”. She was motivated to take on this challenge because she wanted to join her friends’ group of steampunk-style characters from the video game “Final Fantasy VIII”. She says she has not backed down from a challenge ever since: “I kind of started on a hard one and kind of haven’t stopped since then. Literally every time I make something, I learn something new about how to sew”.

Tim, as well, took on challenges that were beyond what his skill level “should” have been. For the first cosplay he wore at a convention, he chose a version of his character’s costume that was not very popular among cosplayers, meaning he had fewer online resources to draw from in order to figure out how to make it. Though he had a great deal of formal training in costume design for theatre, cosplay turned out to be altogether different, and he engaged in trial-and-error to develop skills needed to complete his cosplays. Now he is expert enough that he can make his own sewing patterns and tell how to construct a costume just by looking at it.

3.2.3. Opportunities: Beyond school and jobs

While a less frequent code, “opportunities” helped identify the two cases as outstanding because of the way both Lexi and Tim use skills they learned in cosplay in their jobs and opportunities outside their careers. Lexi continues to learn a great deal about clothing in her job for the digital division of a well-known brand of intimate-wear. However, she gets to do more creative work outside of her job, such as designing a line of interactive, electronically-enhanced clothing for a local fashion show. She does freelance fashion consulting, and her cosplay and fashion design work allow her to get her name on the map for potential clients. This allows her to be a sponsor for others by sharing her knowledge of creative clothing design.

Tim is a sculpture teacher at the same performing arts school he attended as a child. He regularly incorporates cosplay props into his classroom both by bringing in his own and letting students bring in theirs. This sponsorship of others’ interest in cosplay is one of his passions; he hopes to one day establish a permanent cosplay studio in his hometown where cosplayers can gather for lessons and collaborative work. He already takes a leadership role in organizing social events for his local cosplay community as well as volunteering for the local anime convention.

3.2.4. Disconnected learning: A contrast

This code emerged from the data, largely from the interview’s occasional focus on math. Many interviewees –not just the cosplayers– in the larger research project expressed dissatisfaction with their experience with math classes. Lexi and Tim were no exception. Lexi struggled with the highly theoretical math classes she took as part of her undergraduate program in aerospace engineering, saying she would have preferred applications to concrete contexts. She said these math classes “had no basis in reality… It was completely based in a weird surreality that certain people enjoy and I’m not terribly fond of”. In contrast, she said math in cosplay is applied directly to the project the cosplayer is working on.

Most of Tim’s experiences with math classes seemed similarly disconnected from his interests. He lamented that math is not often taught in a way that connects to topics of relevance to students’ lives, contrasting a problem about a train needing to coordinate speed with schedules and passenger numbers, with a problem that involved his interest in cosplay: how could he appropriately budget to buy materials for multiple costumes. It seems that people who have experienced connected learning can recognize how disconnected traditional school learning tends to be.

4. Discussion and conclusion

The data addressed our research questions by showing us how Tim and Lexi’s unique learning pathways in cosplay worked well for them, how their hobby connected to economic opportunities both within and outside careers, and how we can design for connected learning that works well for all learners. Tim and Lexi’s experiences with cosplay learning pathways led to positive outcomes primarily because they connected to important aspects of their lives, as the connected learning framework would suggest. Relationships with peers motivated their initial engagement, and adult sponsors provided access to materials and skills, whether in person or online. They both began their cosplay journeys with a challenge that “should” have been beyond their current skill levels, but they managed it and continued to challenge themselves. This contrasts with conventional views of learning as following a step-by-step trajectory from easier to more difficult, suggesting that when appropriately motivated, learners will surmount challenges “beyond their level”. Both cosplayers were also fortunate to be able to apply their cosplay experiences to their careers, but they also felt a sense of fulfillment from opportunities beyond their careers in which they could sponsor others’ interests in cosplay and clothing. Finally, they both recognized how disconnected their math classes had been from their lives and contrasted that with the way math in cosplay did connect to their interests and goals, suggesting that school should do the same.

These findings help validate the emerging updated connected learning framework’s focus on opportunities in general rather than on “academics” only. Tim and Lexi’s careers and outside-career economic opportunities were important results of their connected learning pathways that would have been missed with an exclusive focus on school. Additionally, this work shows the value of tracing the pathways of adults, in order to see how opportunities play out successfully and how we can help all learners access similarly successful pathways. These cases also help to show the variety of meaningful opportunities that can exist, beyond both school and careers. Future work on connected learning should take all this into account.

To create a more effective connected learning system that values all learners’ interests and skills, and orients them toward economic and political opportunities, these cosplayers show us that we need to 1) Legitimize learners’ interests rather than dismiss them as frivolous. 2) Support their relationships with peers as positive motivators. 3) Act as sponsors who provide access to skills and resources. 4) Support youths’ goals even if they seem beyond their current skill level. 5) Recognize opportunities both inside and outside of careers as ways to enhance creative expression and meaningful relationships with others. Considering how disconnected most traditional schooling is from the rest of youths’ lives, these cosplayers also suggest that 6) School learning should be applied to contexts that matter to students’ interests and future plans.

One way schools have been integrating interest-driven learning into the curriculum is through the growing trend of makerspaces (Wardrip & Brahms, 2016). By providing space and materials for the open-ended making of student-choice projects, schools can sponsor students’ interests, whatever they might be, while students develop production-centered design skills that could be applicable to future opportunities. With a makerspace, a school does not have to be centered on arts like Tim’s was in order to support student interests, nor will students have to wait for graduate school as Lexi did, before learning an interesting hands-on topic like e-fashion. If provided with the proper resources and sponsorship, students could even work on cosplay in a school makerspace, and perhaps set out on a path from there toward a career, just like Tim and Lexi. Even if the makerspace or other interest-driven activity is outside of school, schools could still provide legitimization by, for instance, giving class credit or taking it into account in college applications.

Only when we create supports for unique pathways both in and out of school, throughout the lifespan, will equitable connected learning be accessible to all.

Notes

A preliminary analysis of this data was presented at ICLS (International Conference of the Learning Sciences) 2018. The International Society of the Learning Sciences owns the copyright of the proceedings paper.

Funding Agency

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation of the United States under Grant No. 1420303 awarded to Kylie Peppler.

References

Akiva, T., Kehoe, S., & Schunn, C.D. (2017). Are we ready for citywide learning? Examining the nature of within-and between-program pathways in a community-wide learning initiative. Journal of Community Psychology, 45(3), 413-425. https://doi.org/10.1002

Azevedo, F. S. (2011). Lines of practice: A practice-centered theory of interest relationships. Cognition and Instruction, 29(2), 147-184. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2011.556834

Barron, B. (2010). Conceptualizing and tracing learning pathways over time and setting. Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education, 109(1), 113-127. https://bit.ly/2nFWKvP

Barron, B., Gomez, K., Pinkard, N., & Martin, C.K. (2014). The Digital Youth Network: Cultivating digital media citizenship in urban communities. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. https://bit.ly/2MolBCG

Barron, B., Martin, C.K., Takeuchi, L., & Fithian, R. (2009). Parents as learning partners in the development of technological fluency. International Journal of Learning and Media, 1(2), 55-77. https://doi.org/10.1162/ijlm.2009.0021

Bell, P., Bricker, L., Reeve, S., Zimmerman, H.T., & Tzou, C. (2013). Discovering and supporting successful learning pathways of youth in and out of school: Accounting for the development of everyday expertise across settings. In B. Bevan, P. Bell, R. Ste

Bender, S. (2017). Cosplay. In K. Peppler (Ed.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of out-of-school learning (pp. 155-157). Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781483385198

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219-245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

Hidi, S., & Renninger, K.A. (2006). The four-phase model of interest development. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 111-127. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_4

Ito, M., Gutiérrez, K., Livingstone, S., Penuel, B., Rhodes, J., Salen, K. ... &, Watkins, S.C. (2013). Connected learning: An agenda for research and design. Irvine, CA: Digital Media and Learning Research Hub. https://bit.ly/2iOeKoh

Jenkins, H. (2012). Textual poachers: Television fans and participatory culture. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1016/0363-8111(93)90051-d

Jenkins, H., Purushotma, R., Weigel, M., Clinton, K., & Robison, A.J. (2006). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: Media education for the 21st Century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. https://bit.ly/2ENQPLi

Kumpulainen, K., & Sefton-Green, J. (2014). What is connected learning and how to research it? International Journal of Learning and Media, 4(2), 7-18. https://doi.org/10.1162/IJLM_a_00091

Lave, J. (2011). Apprenticeship in critical ethnographic practice. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226470733.001.0001

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511815355

Maltese, A.V., & Tai, R.H. (2010). Eyeballs in the fridge: Sources of early interest in science. International Journal of Science Education, 32(5), 669-685. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690902792385

Maul, A., Penuel, W.R., Dadey, N., Gallagher, L.P., Podkul, T., & Price, E. (2017). Measuring experiences of interest-related pursuits in connected learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 65(1), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016

Papert, S. (1980). Mindstorms: Children, computers, and powerful ideas. New York, NY: Basic Books, Inc. https://bit.ly/2MvEF1L

Pascale, R. T., Sternin, J., & Sternin, M. (2010). The power of positive deviance: How unlikely innovators solve the world’s toughest problems. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press. https://bit.ly/2OAbZSv

Peppler, K., & Gresalfi, M. (2014). Re-crafting mathematics education: Designing tangible manipulatives rooted in traditional female crafts. https://bit.ly/2McuShP

Philip, T.M., Bang, M., & Jackson, K. (2017). Articulating the ‘how’, the ‘for what’, the ‘for whom’, and the ‘with whom’ in concert: A call to broaden the benchmarks of our scholarship. Cognition and Instruction, 36(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.

Reich, J., & Ito, M. (2017). From good intentions to real outcomes: Equity by design in learning technologies. Irvine, CA: Digital Media and Learning Research Hub. https://bit.ly/2MN7WSC

Wardrip, P.S., & Brahms, L. (2016). Taking making to school: A model for integrating making into classrooms. In K. Peppler, E. Halverson, & Y. Kafai (Eds.), Makeology: Makerspaces as learning environments, Vol 1 (pp. 97-106). New York, NY: Routledge. http

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El aprendizaje conectado explica cómo las personas pueden construir rutas de aprendizaje conectadas a sus intereses, sus relaciones y al aprendizaje formal que lleven a oportunidades de futuro en una carrera profesional. Sin embargo, la mayoría de los sistemas de aprendizaje no están diseñados para una experiencia de aprendizaje conectado. Por ejemplo, casi todas las escuelas siguen enseñando asignaturas como unidades cerradas que no conectan con los intereses de los alumnos fuera de la escuela. Todavía no sabemos lo suficiente sobre la estructura de los ambientes naturales de aprendizaje conectado que sí activan la experiencia de aprendizaje con diferentes contextos y llevan a los alumnos hacia un camino de crecimiento. Aprender más sobre lo que funciona en estas rutas de aprendizaje nos permitirá diseñar entornos de aprendizaje conectado para ayudar a más jóvenes a obtener los resultados deseados. El presente trabajo analiza dos casos prácticos de «cosplayers» –aficionados que crean sus propios disfraces de personajes ficticios y los llevan a convenciones y eventos– que se beneficiaron de entornos de aprendizaje conectado correctamente desarrollados. Aspectos importantes que surgieron en el estudio incluyen las relaciones con el apoyo y cuidado de y hacia los otros: dos caminos únicos que comienzan con un difícil desafío: las oportunidades económicas derivadas del cosplay y las comparaciones con otras experiencias escolares formales. Todo ello afecta la manera de diseñar entornos de aprendizaje conectado que apoyen a todos los alumnos en sus caminos únicos hacia el futuro.

1. Introducción

Investigadores del área del aprendizaje llevan años estudiando el aprendizaje que tiene lugar en comunidades reales fuera de las escuelas, como los aprendices de sastre y comadronas (Lave & Wenger, 1991) o los aficionados que construyen cohetes (Azevedo, 2011). El aprendizaje que se enmarca dentro de intereses particulares y aficiones extracurriculares no siempre es valorado socialmente, en cambio es visto como menos importante que el aprendizaje dentro de la escuela (Lave, 2011) en los casos en que dichos intereses llevan a oportunidades de estudio adicionales o cuando son el principal recurso de los jóvenes para aprender sobre los medios modernos (Barron, 2010; Jenkins, Purushotma, Weigel, Clinton, & Robison, 2006).

El aprendizaje conectado (Ito & al., 2013) nos da un marco que ayuda a conceptualizar el aprendizaje en relación a los intereses de los jóvenes y a sus relaciones con otros de un modo que conecta con las oportunidades más orientadas al futuro como la escuela, la educación superior, las carreras universitarias o la influencia política. Sin embargo, es poco lo que sabemos sobre cómo los estudiantes recorren estos caminos de cara a poder orientar el diseño de los entornos de aprendizaje futuros. Si bien las rutas de aprendizaje conectado de los jóvenes han sido estudiadas (Ito & al., 2013; Barron, 2010), es muy poco lo que sabemos sobre el de los adultos que han logrado canalizar su pasión hacia oportunidades profesionales trascendentes y duraderas. Una manera de aprender más sobre esto es mirar en retrospectiva algunos casos prácticos (Maltese & Tai, 2010) para reunir el testimonio de adultos que tuvieron estas experiencias y, así, poder aplicarlas al diseño intencional de un entorno de aprendizaje conectado.

El «cosplay» (Bender, 2017) es la presentación de personajes de ficción mediante disfraces y juegos de roles –de ahí la voz compuesta «cosplay», un híbrido de los vocablos ingleses «costume» (disfraz) y «play» (juego)–, en diferentes eventos como convenciones de fans; lo que nos da un ejemplo de cómo el aprendizaje puede estar conectado con las oportunidades futuras. Como parte de este hobby, los «cosplayers» están motivados para profundizar en sus intereses, aprender habilidades, establecer conexiones con mentores y redes de aficionados y enriquecer su experiencia vital. En estos casos, los cosplayers se han visto beneficiados por un entorno de aprendizaje conectado exitoso; pero el sistema no siempre permite legitimar las habilidades aprendidas en su hobby, conectarlas con su aprendizaje académico o crear oportunidades profesionales relacionadas con ellas. Al observar las diferencias entre el aprendizaje conectado positivo en el cosplay y algunos ejemplos de aprendizaje desconectado en las escuelas podemos aprender sobre cómo rediseñar los entornos de aprendizaje a todos los niveles para apoyar los aprendizajes individuales hacia una oportunidad futura de todos los estudiantes, especialmente de aquellos que han sido sistemáticamente desplazados por falta de acceso a recursos o patrocinios que sirvan para legitimar sus intereses extraescolares. Al investigar las perspectivas de los cosplayers en su práctica, preguntamos: ¿Qué tipos de rutas de aprendizaje existen en el cosplay? ¿Cómo puede esta afición conectar a los cosplayers con oportunidades futuras? ¿Cómo podemos hacer que estos mecanismos –y los entornos de aprendizaje en general– funcionen mejor para aquellos que no encuentran conexiones entre sus intereses extracurriculares y un futuro profesional?

1.1. Aprendizaje conectado

En un mundo digital interconectado, la juventud de hoy necesita encontrar maneras de conectar las redes, intereses y habilidades que cultivan tanto online como offline, dentro y fuera de la escuela, con ventanas de oportunidad. Legitimar los intereses y experiencias de los jóvenes ayudará a la juventud entera a labrar sus propios caminos. En su informe de 2013, Ito, Salen y Sefton-Green introdujeron un marco de «aprendizaje conectado» para describir y explicar fenómenos que conectan distintas esferas de aprendizaje hacia oportunidades futuras. Desde entonces, Ito y otros (2013) han estado editando un nuevo informe que reformula algunos aspectos de este marco, describiendo cómo los entornos de aprendizaje conectados maximizan su efecto en la intersección de tres esferas: «relaciones» (por ej. con compañeros, familia y mentores), «intereses» (por ej. en un hobby o club de fans), y «oportunidad» (que se expande más allá del foco inicial del informe en lo «académico» para incluir carreras profesionales, emancipación política, etc.).

Cada uno de estos puntos contribuye singularmente a la creación de un entorno que conecta y legitima el aprendizaje en diferentes contextos a lo largo de la vida. El interés en un área concreta tiende a generar la motivación que lleva a un compromiso a largo plazo en actividades de aprendizaje conectado (Hidi & Renninger, 2006). La producción sirve para alentar el aprendizaje activo en tanto en cuanto los jóvenes fabrican, comparten, remezclan y se ven reflejados en artefactos (Papert, 1980). Un fin común garantiza la cohesión de la comunidad en la medida en que todos trabajan para alcanzar metas comunes, sin importar la edad u otras diferencias demográficas. Las relaciones con los compañeros crean un contexto que es importante para la juventud, así como las relaciones en general son importantes para la construcción de un fin común.

1.2. ¿Por qué estudiar trayectorias?

Muchos estudiantes conectados se prestan al estudio de trayectorias de aprendizaje (Barron, 2010; Kumpulainen & Sefton-Green, 2014) para ayudarnos a entender mejor cómo funciona el aprendizaje a largo plazo («estudio vital»), y debido a que las intervenciones de aprendizaje a corto plazo dan un pobre resultado cuando existen barreras sistemáticas que impiden a los jóvenes aspirar a un futuro gratificante (Philip, Bang, & Jackson, 2017). Esta situación reclama un estudio sobre cómo aprenden los jóvenes aquellas habilidades aplicables a sus metas futuras, cómo logran los mentores mediar para crear oportunidades, y cómo podemos facilitar esto a toda la juventud. La meta de toda educación debería ser vivir una vida enriquecedora, ir más allá de los muros de la escuela y labrarse un futuro como miembros productivos de la sociedad (Bell, Bricker, Reeve, Zimmerman, & Tzou, 2013) para conocer otra perspectiva sobre el estudio de trayectorias de aprendizaje. Es por ello que un marco de aprendizaje conectado va más allá de la jornada escolar para conectarla con los hobbies de los estudiantes.

Trabajos previos de carácter similar han estudiado la trayectoria de los jóvenes mediante «tecnobiografías» autodirigidas con tecnología fuera de la escuela (Barron, 2010). Barron, Gomez, Pinkard y Martin (2014) crearon la Red Digital Juvenil, un intento de cultivar un entorno de aprendizaje conectado, y explicaron cómo los jóvenes que participaban en el programa alcanzaron el dominio de los nuevos medios con el tiempo y sin importar el contexto. Otro estudio reciente puso en práctica las esferas y principios del aprendizaje conectado de manera similar al presente estudio, con el objetivo de comparar las experiencias de los jóvenes con el aprendizaje conectado, pero una vez más estuvo limitado a la juventud (Maul & al., 2017). Bell y otros (2013) trazaron trayectorias de aprendizaje en las áreas de ciencias de jóvenes estudiantes mediante minuciosas etnografías, identificando las maneras en que estos jóvenes se involucraban en el estudio de la ciencia, como por ejemplo el aprendizaje de biología mediante comportamientos vinculados a la salud, en un periodo largo de tiempo y en distintos contextos.

Maltese y Tai (2010) entrevistaron a 116 estudiantes graduados y científicos para determinar qué experiencias avivaron su interés en la ciencia. Como el presente estudio, esa investigación incluía entrevistas con adultos para determinar en retrospectiva cuáles fueron las experiencias que marcaron su camino presente hacia una carrera científica. Sin embargo, no trazó su trayectoria completa, y solo se enfocó en el área de ciencias.

1.3. Cosplay: Aprendizaje conectado en acción

Hay cosplayers de todos los tipos, desde aquellos que crean cosplays «de armario» mediante combinaciones de prendas comunes que se encuentran en cualquier armario, hasta aquellos que compran disfraces hechos por profesionales o los que fabrican su propio disfraz desde cero. Tal vez copien el atuendo de un personaje de manera idéntica a como aparece en la televisión, en una película, videojuego, cómic, etc., o tal vez diseñen una versión alternativa de ese atuendo, con un estilo «steampunk», una falsa estética victoriana con accesorios de estética «steam-powered». La mayoría de cosplayers llevan sus disfraces a convenciones de fans («cons»), donde posan para fotos, conocen a otros fans con quienes comparten intereses, compran artículos relacionados con sus aficiones preferidas y asisten a charlas sobre los mismos temas. En este sentido, el cosplay es una cultura participativa que celebra los productos mediáticos al tiempo que los «falsifica» y reinterpreta con disfraces que permiten a los fans convertirse literalmente en personajes (Jenkins, 2012). Como otras culturas participativas, el cosplay está abierto a la participación creativa de cualquiera que esté interesado, apoya dicha creación y la voluntad de compartirla, involucra formas informales de patrocinio ya sea en persona o mediante tutoriales/recursos online, sus miembros creen que sus creaciones importan, y tienen una conexión social entre ellos (Jenkins & al., 2006). Todo ello ayuda a respaldar el proceso de aprendizaje en el cosplay, donde es tan firme como en otras culturas participativas (Jenkins & al., 2006).

El cosplay encaja bien en un marco de aprendizaje conectado, sobre todo para aquellos que siguen una senda que implica aprender desde la fabricación de sus propios disfraces, algo que comienza con un «interés» en determinado fenómeno, o con «relaciones» con amigos que están buscando armar un grupo de cosplay para ir a una convención. Las habilidades desarrolladas y las relaciones construidas tanto online como offline pueden crear «caminos» hacia «oportunidades», como desarrollar habilidades comparables a una carrera profesional. Dado que el cosplay es un hobby caro, el patrocinio es importante y muchos jóvenes cosplayers dependen de sus padres y otros adultos para que financien sus primeras incursiones en el cosplay pagando materiales, asistiendo a los eventos, etc. Por otro lado, los cosplayers pueden construir su trayectoria usando recursos online como tutoriales, demostraciones y grupos de debate donde pueden hacer preguntas y recibir consejos. La «meta común» de la comunidad cosplay –fabricar o adquirir disfraces de personajes para llevarlos a eventos como convenciones– implica que los miembros de la comunidad están dispuestos a ayudar y se dan la bienvenida mutuamente, tanto online como en persona en las convenciones. Y, por supuesto, esta es una práctica «centrada en la producción» debido a la producción de disfraces y a las actuaciones «en personaje».

Sin embargo, no todos los cosplayers logran acceder a oportunidades económicas o de patrocinio mediante su hobby. La mayoría de entornos no están configurados para permitir dicho acceso, aunque sea deseado. Así que mientras el cosplay en general es exitoso a la hora de conectar intereses y aprendizaje, debemos estudiar los casos excepcionales que también lo conectan con oportunidades de crecimiento económico si deseamos hallar los principios de diseño de trayectorias profesionales que puedan proporcionar esas oportunidades para todos los jóvenes.

Al enfocar esta investigación nos guiamos por las siguientes preguntas: ¿Qué tipos de trayectorias de aprendizaje existen en el cosplay? ¿Cómo puede este hobby conectar a los cosplayers con oportunidades de futuro? ¿Cómo podemos hacer que el cosplay –y los entornos de aprendizaje en general– funcione mejor para los que no experimentan conexiones entre sus intereses extracurriculares y las oportunidades de futuro?

2. Materiales y métodos

Para explorar las trayectorias de los cosplayers el autor principal se ubicó como un etnógrafo integrado en la comunidad cosplay como parte de un proyecto sobre la matemática inherente a las artes textiles financiado por la Fundacion Nacional de Ciencias de los Estados Unidos (Peppler & Gresalfi, 2014). Tras obtener su consentimiento informado se entrevistó con diez cosplayers que participaban en convenciones de fans regionales, usando un protocolo de entrevista semiestructurada en el que se preguntaba cómo habían aprendido los participantes las habilidades necesarias para el cosplay, qué les llevaba a participar de este hobby, historias sobre sus proyectos particulares y cómo las comunidades online y offline están involucradas en su práctica. En cada entrevista los cosplayers hablaron de sus experiencias con su actual ocupación y en la escuela, enfocándose especialmente en las clases de matemáticas, debido al proyecto de investigación supuestamente relacionado con este área. El protocolo de entrevista fue diseñado para determinar aspectos de la comunidad y de su contexto que llevaron al aprendizaje de técnicas artesanales (en este caso, la técnica del cosplay), así como para comparar las matemáticas usadas en esta área con las usadas en la escuela. Si bien la entrevista no incluía preguntas específicas sobre principios de aprendizaje conectado, probablemente no deba sorprendernos que este tema surgiera de la discusión sobre hobbies, relaciones con una comunidad y oportunidades académicas o profesionales.

Los cosplayers fueron entrevistados individualmente salvo un caso en que tres cosplayers hablaron al mismo tiempo con el entrevistador. Las entrevistas fueron en persona, por teléfono o por videoconferencia y duraron aproximadamente entre 45 minutos y una hora. Dos entrevistados eran hombres, y ocho eran mujeres. Fueron seleccionados mediante un proceso de muestreo de conveniencia –cosplayers a quienes el entrevistador conocía en persona– que llevó a un muestreo bola de nieve: amigos de la primera ola de cosplayers. Sus edades oscilaban entre los 21 y los 33 años en el momento de la entrevista, y todos eran americanos caucásicos residentes en los Estados Unidos.

Todas las entrevistas fueron transcritas y revisadas por el autor principal para identificar casos convincentes de trayectorias de aprendizaje conectado. Al analizar las entrevistas hallamos que los cosplayers describían el cosplay como una fuerza importante en sus vidas y describían minuciosas trayectorias de aprendizaje en relación a cómo se iniciaron en el cosplay y siguieron vinculados a este hobby. Para muchos de los cosplayers, su hobby siguió desconectado de cualquier oportunidad económica o profesional. Dos entrevistas destacaron como casos excepcionales de conexión entre el cosplay y una carrera profesional, de las que se pueden inferir conocimientos aplicables al diseño de trayectorias de aprendizaje conectado. Estos ejemplos actuaron como modelos de desviación positiva (Pascale, Sternin, & Sternin, 2010) y como casos extremos (Flyvbjerg, 2006) que fueron, de entre todas las entrevistas, los que más información y sugerencias aportaron sobre cómo un modelo de aprendizaje conectado bien diseñado podría desarrollarse, explicando cómo el cosplay podría llevar a oportunidades económicas. En cuanto a las otras entrevistas o bien no mostraron conexiones directas entre el cosplay y las carreras profesionales o, en un caso, faltaban detalles cruciales debido a los límites temporales de la entrevista. Los casos extremos a menudo son los que mejor información aportan sobre cómo funciona el fenómeno, lo que justifica su inclusión (Flyvbjerg, 2006). Este era el caso aquí reflejado.

Las entrevistas fueron divididas en segmentos analíticamente relevantes (normalmente de una frase o unas pocas frases sobre el mismo tema). Cada segmento fue introducido en Microsoft Excel y codificado a priori de acuerdo con las esferas y principios de aprendizaje conectado; luego se dividieron los datos por tema. El código permaneció abierto a temas emergentes. Cada código está descrito en la Tabla 1.

Además de los códigos de aprendizaje conectado relacionados al marco de trabajo, otro tema surgió en relación al debate sobre las áreas disciplinarias tradicionalmente enseñadas en las escuelas (por ej. las matemáticas). Las instancias en que se menciona este aprendizaje disciplinario fueron subcodificadas como «conectadas» o «desconectadas» de los intereses, proyectos, etc., dependiendo de la exposición del entrevistado.

Los códigos se combinaron para dar forma a los temas detallados en los resultados más abajo, y las anécdotas y citas relacionadas con los temas fueron sacadas de los informes de los entrevistados para ilustrar principios de diseño para fabricar trayectorias de aprendizaje más conectadas a sus intereses, relaciones y oportunidades.

3. Resultados

A continuación se presenta un resumen de cada uno de los dos casos de cosplay, seguido de los temas derivados de la codificación de las entrevistas.

3.1. Presentación de casos de cosplay conectado

Lexi (todos los nombres son pseudónimos) llevaba practicando cosplay nueve años y tenía 31 en el momento de la entrevista. Con su madre artista como sponsor en el aprendizaje de nuevas habilidades y sus amigas animándola a unirse a su grupo cosplay, Lexi se sumergió en el hobby con un disfraz cuya elaboración fue un gran desafío. Ahora utiliza los conocimientos adquiridos del cosplay sobre costura en su trabajo para una gran empresa de ropa íntima. Sigue buscando oportunidades para expresarse creativamente a través de la moda, diseñando para shows de moda locales y trabajando como consultora de moda freelance. A menudo Lexi practica el cosplay inspirado en videojuegos que disfruta, y casi siempre lo hace con un grupo de amigos que se disfrazan de personajes de la misma serie, como cuando lo hicieron con el programa de televisión «Avatar: The Last Airbender» y ayudó a crear los disfraces del mismo programa para aquellos de su grupo que no cosían. Casi siempre se disfraza de personajes masculinos, en parte porque de esta manera es menos probable que los hombres muestren un interés romántico hacia ella. Como mujer que lleva muchos años comprometida en una relación con otra mujer, este es un resultado deseable, pero también le permite jugar con su género en formas que disfruta. Ver la Figura 1 para conocer un ejemplo de Kuja, un personaje masculino de videojuego interpretado por Lexi. Kuja lleva un traje revelador, y Lexi se mostró divertida al contar que había habido reacciones de confusión hacia su género cuando llevó este disfraz. Lo que le gusta del cosplay es que «es agradable poder salirse de uno mismo por un rato».

Figura 1. Lexi como Kuja de «Final Fantasy IX»

El interés de Tim por el diseño y la industria del entretenimiento pronto se vio respaldado por su inscripción en una escuela secundaria de artes escénicas para la que ahora, a sus 33 años en el momento de la entrevista, trabaja como profesor de escultura. Como Lexi, comenzó a practicar el cosplay para unirse a sus amigos en convenciones de fans y para expresar su afición por determinados personajes. Ahora está devolviendo la ayuda que recibió, y alienta el interés de otros en el arte y el cosplay. Deja que sus alumnos lleven proyectos de cosplay a clase, a veces hasta lleva los suyos propios, y permite a sus amigos usar el estudio que tiene en casa para trabajar en el cosplay y aprender sus técnicas. Es muy hábil tanto cosiendo como diseñando accesorios. La Figura 1 muestra uno de los cosplays de Tim, el del Capitán Harlock, un personaje de varios programas de televisión y películas como «Space Pirate Captain Harlock». Tim siempre ha adorado este personaje desde que lo conoció en una de las primeras películas «anime» que vio. Describe a Harlock como «oscuro» y «misterioso», y da muchos detalles cuando cuenta cómo hizo este disfraz soñado, desde moldear la pistola de Harlock con silicona hasta enganchar broches a la capa para que no se rompa. También describió el disfraz como «nunca terminado», detallando sus planes para añadir un pájaro animatrónico, para representar el loro de Harlock. Su pasión por el cosplay se manifiesta como un continuo desafío.

Figura 2. Tim como Captain Harlock de «Space Pirate Captain Harlock».

Resultados del análisis de los dos casos mostraron que si bien todos los aspectos del marco de trabajo de aprendizaje conectado jugaron un papel en la trayectoria de los participantes, las relaciones (sobre todo con compañeros y sponsors), los comienzos difíciles y las oportunidades eran temas con especial peso. Ambos entrevistados también hablaron de las clases de matemáticas como una experiencia desconectada que contrastaba con su experiencia de aprendizaje en el cosplay.

3.2. Temas3.2.1. Cuidar a otros: Amigos, familia, sponsors

Como combinación de los códigos «relaciones», «fin común» y «patrocinio», este tema se reveló como muy común en los datos, y fue clave para motivar la involucración inicial y continuada en el cosplay. Tanto Lexi como Tim, como la mayoría de cosplayers, se introdujeron en este mundo porque sus amigos querían que se unieran a su grupo de cosplay en las convenciones, de manera que su relación con compañeros que compartían su mismo interés supuso un acicate inicial. El interés compartido por un hobby y el fin común de celebrar esos intereses en las convenciones también hicieron de catalizadores a la hora de hacer nuevos amigos. Como dijo Tim: «Hay una gran diferencia entre practicar cosplay solo y hacerlo en un grupo grande. Es mucho más divertido, cuando te encuentras a dos o tres personas y les dices: ‘Eh, sois de nuestro mismo programa’, y los llevas contigo y pasas el día con ellos; todo el tiempo estás haciendo amigos». Las amistades son vitales en la vida de los jóvenes, y los cosplayers no son una excepción a esto.

El patrocinio por parte de adultos (Barron, Martin, Takeuchi, & Fithian, 2009) también jugó un papel importante. En el caso de Lexi, su madre es una artista que siempre la animó cuando crecía a aprender nuevas habilidades practicando, y fue ella quien le dio a Lexi su primera máquina de coser cuando mostró interés en crear sus propios cosplays. Más adelante, Lexi recibió patrocinio y la legitimación de sus intereses en el ámbito de la educación formal en su maestría en Interacción Humanos-Computadoras, donde aprendió cómo integrar dispositivos electrónicos en la ropa. Tim también recibió patrocinio desde el ámbito de la educación formal, como cuando asistió a una escuela de artes escénicas en secundaria, donde aprendió diseño de vestuario para teatro, y sus estudios de Diseño del Entretenimiento, donde aprendió habilidades como el moldeado sobre yeso de resina que puede usar para crear accesorios de cosplay. Más allá de estas trayectorias formales, ambos cosplayers aprendieron mucho de fuentes online y mentores.

3.2.2. Trayectorias: Empezar a lo grande

«Construcción de trayectorias» fue el código más común, pero un hallazgo interesante surgió en la forma en que las trayectorias del cosplay tendían a empezar. Si bien los diez cosplayers siguieron caminos únicos, un tema común que surgió en casi todas las entrevistas fue el hecho de afrontar grandes desafíos al principio del proceso de convertirse en cosplayers. Por ejemplo, para el primer disfraz que cosió, Lexi tuvo que coser unas cintas a lo largo de las curvas de una especie de corsé. No fue fácil, ella misma dijo: «Si alguna vez quieres aprender a coser, no lo hagas cosiendo cinta en una curva». Afrontar este desafío le motivaba porque quería unirse a su grupo de amigos disfrazados de personajes estilo steampunk del videojuego «Final Fantasy VIII». Y, dice que, desde entonces no ha dejado de enfrentarse a ningún desafío: «Empecé con algo difícil y desde entonces no he parado. Literalmente cada vez que hago algo aprendo algo nuevo sobre cómo coser».

Tim también afrontó desafíos que estaban más allá de lo que debía ser su nivel. Para el primer cosplay que llevó a una convención escogió una versión de traje para su personaje que no era muy popular entre cosplayers, por lo que tenía menos recursos online para dibujar el patrón y hacerlo. Si bien tenía muchas horas de práctica formal en diseño de vestuario para teatro, el cosplay resultó ser algo totalmente distinto, y se sumergió en un proceso de ensayo y error hasta desarrollar las habilidades necesarias para completar sus cosplays. Ahora es un experto capaz de crear sus propios patrones y de saber cómo hacer un disfraz con solo mirarlo.

3.2.3. Oportunidades: más allá de la escuela y el trabajo

Si bien es un código menos frecuente, el epígrafe «oportunidades» ayudó a identificar los dos casos destacados por la manera en que Lexi y Tim aplican las habilidades aprendidas en el cosplay en sus trabajos y en distintas oportunidades fuera de su ámbito profesional. Lexi sigue aprendiendo sobre vestuario en su trabajo para la división digital de una conocida marca de ropa íntima. Sin embargo, desarrolla un trabajo más creativo fuera de su profesión, como diseñar una línea de ropa interactiva con dispositivos electrónicos para un show de moda local. Hace consultoría de moda freelance, y su trabajo de cosplay y diseño de moda le permiten poner su nombre en el mapa para clientes potenciales. Esto le permite hacer de sponsor con otros compartiendo su conocimiento sobre el diseño creativo de ropa.

Tim es profesor de escultura en la misma escuela de artes dramáticas a la que asistió de pequeño. A menudo incorpora accesorios de cosplay a sus clases, tanto llevando los suyos propios como permitiendo que sus alumnos lleven los suyos. Este patrocinio del interés de otros en el cosplay es una de sus pasiones; espera algún día establecer un estudio permanente de cosplay en su pueblo natal donde los cosplayers puedan reunirse para recibir lecciones y realizar trabajo colaborativo. Ya adopta un papel de liderazgo organizando eventos sociales para su comunidad local de cosplay, así como haciendo voluntariado en la convención local de anime.

3.2.4. Aprendizaje desconectado: Un contraste

Este código surgió de los datos, en gran medida del ocasional foco de la entrevista en las matemáticas. Muchos entrevistados –no solo los cosplayers– en el proyecto de investigación principal expresaron su insatisfacción con su experiencia en clase de matemáticas. Lexi y Tim no son una excepción. A Lexi le costó adaptarse a la parte teórica de las clases de matemáticas que recibía como parte de sus estudios de ingeniería aeroespacial, y dice que habría preferido estudiar aplicaciones a contextos concretos. Dice que estas clases matemáticas «no estaban basadas en la realidad... Estaban completamente basadas en una extraña surrealidad que cierta gente disfruta y que no me gusta». En contraste, dice que las matemáticas en el cosplay se aplican directamente al proyecto en el que está trabajando el cosplayer.

La mayoría de experiencias de Tim en clase de matemáticas parecían estar igualmente desconectadas de sus intereses. Lamenta que las matemáticas no se enseñen de manera que se conecten con temas relevantes para la vida de los estudiantes, comparando un problema sobre un tren que debe coordinar su velocidad con ciertos horarios y números de pasajeros con un problema que involucraba su interés por el cosplay: cómo podría hacer un presupuesto para comprar materiales para muchos disfraces. Pareciera que las personas que han experimentado el aprendizaje conectado son capaces de reconocer lo desconectada que suele estar la enseñanza tradicional en las escuelas.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

Los datos recogidos en nuestra investigación que muestran lo bien que funcionó el cosplay en las trayectorias de Tim y Lexi, nos hacen preguntarnos cómo conectaron su hobby con una oportunidad económica tanto dentro como fuera del ámbito profesional/académico, y cómo podemos diseñar un modelo de aprendizaje conectado que funcione bien con todos los estudiantes. Las experiencias de Tim y Lexi con las trayectorias de aprendizaje en cosplay funcionaron bien principalmente porque los conectaron con aspectos importantes de sus vidas, como sugiere el marco de trabajo de aprendizaje conectado. Las relaciones con sus compañeros motivaron su arranque inicial, y los sponsors adultos les dieron acceso a materiales y habilidades, ya fuera en persona u online. Ambos comenzaron su experiencia en el cosplay con un desafío que estaba por encima de sus posibilidades en ese momento, pero lograron afrontarlo y siguieron afrontando retos. Esto contrasta con una visión convencional del aprendizaje como una trayectoria paso a paso de lo más fácil a lo más difícil, y sugiere que cuando la motivación es adecuada, los estudiantes superarán desafíos «por encima de su nivel». Por último, ambos reconocen lo desconectadas que sus clases de matemáticas habían estado de sus vidas, y compararon esto con la forma en que las matemáticas en el cosplay se conectaron con sus metas e intereses, sugiriendo que las escuelas deben hacer lo mismo.

Estos hallazgos ayudan a validar el foco del marco de trabajo de aprendizaje conectado emergente sobre las oportunidades en general más que solo en lo académico. Para crear un sistema de aprendizaje conectado más efectivo, que valore los intereses y habilidades de todos los alumnos y los oriente hacia oportunidades económicas y políticas, estos cosplayers nos muestran que debemos: 1) Legitimar los intereses del alumno en vez de desecharlos por frívolos; 2) Apoyar sus relaciones con compañeros o posibles motivadores; 3) Actuar como sponsors que dan acceso a habilidades y recursos; 4) Apoyar las metas de los jóvenes aunque parezcan fuera de su alcance; 5) Identificar oportunidades tanto dentro como fuera del ámbito académico/profesional como formas de potenciar la expresión creativa y establecer relaciones significativas con otros; 6) El aprendizaje en la escuela debería aplicarse a contextos relacionados con los intereses y planes futuros de los alumnos.

Una manera en que las escuelas han estado integrando el aprendizaje autodirigido en sus programas es mediante la creciente tendencia de poner espacios de creación a disposición de los alumnos (Wardrip & Brahms, 2016). Al proporcionar espacio y materiales para la elaboración de proyectos escogidos por los alumnos, las escuelas pueden patrocinar sus intereses, sean los que sean, al tiempo que ellos desarrollan habilidades de diseño centradas en la producción que podrían ser aplicables a oportunidades futuras. Si se acompaña de los recursos y patrocinios adecuados, los alumnos podrían incluso trabajar en un cosplay en un espacio de creación escolar, y quizá comenzar una trayectoria hacia una carrera profesional, igual que Tim y Lexi. Aunque el espacio de creación u otra actividad autodirigida se desarrolle fuera de las escuelas, estas aun pueden legitimarlo, por ejemplo, dando créditos de estudio o teniendo esa experiencia en cuenta en las solicitudes que se mandan a las universidades. Sólo cuando creamos apoyos para fomentar trayectorias únicas tanto dentro como fuera de la escuela, durante toda la vida, el aprendizaje conectado será accesible a todos.

Apoyos

Este estudio está patrocinado por la Fundación Nacional de Ciencias de los Estados Unidos (Beca 1420303), concedida a Kylie Peppler.

Referencias

Akiva, T., Kehoe, S., & Schunn, C.D. (2017). Are we ready for citywide learning? Examining the nature of within-and between-program pathways in a community-wide learning initiative. Journal of Community Psychology, 45(3), 413-425. https://doi.org/10.1002

Azevedo, F. S. (2011). Lines of practice: A practice-centered theory of interest relationships. Cognition and Instruction, 29(2), 147-184. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2011.556834

Barron, B. (2010). Conceptualizing and tracing learning pathways over time and setting. Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education, 109(1), 113-127. https://bit.ly/2nFWKvP

Barron, B., Gomez, K., Pinkard, N., & Martin, C.K. (2014). The Digital Youth Network: Cultivating digital media citizenship in urban communities. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. https://bit.ly/2MolBCG

Barron, B., Martin, C.K., Takeuchi, L., & Fithian, R. (2009). Parents as learning partners in the development of technological fluency. International Journal of Learning and Media, 1(2), 55-77. https://doi.org/10.1162/ijlm.2009.0021

Bell, P., Bricker, L., Reeve, S., Zimmerman, H.T., & Tzou, C. (2013). Discovering and supporting successful learning pathways of youth in and out of school: Accounting for the development of everyday expertise across settings. In B. Bevan, P. Bell, R. Ste

Bender, S. (2017). Cosplay. In K. Peppler (Ed.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of out-of-school learning (pp. 155-157). Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781483385198

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219-245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

Hidi, S., & Renninger, K.A. (2006). The four-phase model of interest development. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 111-127. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_4

Ito, M., Gutiérrez, K., Livingstone, S., Penuel, B., Rhodes, J., Salen, K. ... &, Watkins, S.C. (2013). Connected learning: An agenda for research and design. Irvine, CA: Digital Media and Learning Research Hub. https://bit.ly/2iOeKoh

Jenkins, H. (2012). Textual poachers: Television fans and participatory culture. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1016/0363-8111(93)90051-d

Jenkins, H., Purushotma, R., Weigel, M., Clinton, K., & Robison, A.J. (2006). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: Media education for the 21st Century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. https://bit.ly/2ENQPLi

Kumpulainen, K., & Sefton-Green, J. (2014). What is connected learning and how to research it? International Journal of Learning and Media, 4(2), 7-18. https://doi.org/10.1162/IJLM_a_00091

Lave, J. (2011). Apprenticeship in critical ethnographic practice. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226470733.001.0001

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511815355

Maltese, A.V., & Tai, R.H. (2010). Eyeballs in the fridge: Sources of early interest in science. International Journal of Science Education, 32(5), 669-685. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690902792385

Maul, A., Penuel, W.R., Dadey, N., Gallagher, L.P., Podkul, T., & Price, E. (2017). Measuring experiences of interest-related pursuits in connected learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 65(1), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016

Papert, S. (1980). Mindstorms: Children, computers, and powerful ideas. New York, NY: Basic Books, Inc. https://bit.ly/2MvEF1L

Pascale, R. T., Sternin, J., & Sternin, M. (2010). The power of positive deviance: How unlikely innovators solve the world’s toughest problems. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press. https://bit.ly/2OAbZSv

Peppler, K., & Gresalfi, M. (2014). Re-crafting mathematics education: Designing tangible manipulatives rooted in traditional female crafts. https://bit.ly/2McuShP

Philip, T.M., Bang, M., & Jackson, K. (2017). Articulating the ‘how’, the ‘for what’, the ‘for whom’, and the ‘with whom’ in concert: A call to broaden the benchmarks of our scholarship. Cognition and Instruction, 36(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.

Reich, J., & Ito, M. (2017). From good intentions to real outcomes: Equity by design in learning technologies. Irvine, CA: Digital Media and Learning Research Hub. https://bit.ly/2MN7WSC

Wardrip, P.S., & Brahms, L. (2016). Taking making to school: A model for integrating making into classrooms. In K. Peppler, E. Halverson, & Y. Kafai (Eds.), Makeology: Makerspaces as learning environments, Vol 1 (pp. 97-106). New York, NY: Routledge. http

Document information

Published on 31/12/18

Accepted on 31/12/18

Submitted on 31/12/18

Volume 27, Issue 1, 2019

DOI: 10.3916/C58-2019-03

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?