Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

e-Research is changing practices and dynamics in social research by the incorporation of advanced e-tools to process data and increase scientific collaboration. Previous research shows a positive attitude of investigators through e-Research and shows a fast incorporation of e-Tools, in despite of many cultural resistances to the change. This paper examines the current state (attitudes, tools and practices) of e-Research in the field of Media and Communication Studies in Latin America, Spain and Portugal. A total of 316 researchers of the region answered an online survey during the last 2 months of 2011. Findings confirm an optimistic attitude through e-Research and an often use of e-Tools to do research. Even though, most of them informed to use basic e-Tools (e.g. e-mail, commercial videoconference, office software and social networks) instead of advanced technologies to process huge amount of data (e.g. Grid, simulation software and Internet2) or the incorporation to Virtual Research Communities. Some of the researchers said that they had an «intensive» (31%) and «often» (53%) use of e-Tools, but only 22% stated that their computer capacity was not enough to manage and process data. The paper evidences the gap between e-Research in Communications and e-Research in other disciplines; and makes recommendations for its implementation.

1. Introduction

The paradigm of «e-Science» is currently transforming the methods and tools used in scientific research (Hey & al., 2009), increasing possibilities for researchers and allowing them to discover and investigate new objects of study. Other terms such as «cyber science» (Nentwich, 2003) or «cyber infrastructure» (Atkins Report, 2003 on «e-Infrastructure in the European environment») have been used to refer to these changes in the methods of conducting scientific research. Similarly there have been more recent developments in concepts such as Science 2.0 (Waldrop, 2008) to describe the use of tools from what has been termed Web 2.0 (active and decentralized participation by users) and Open Science (Neylon & Wu, 2009), which covers the opening up of the scientific process to practices that involve the free distribution of knowledge. Concepts such as e-Research point to new practices and methods in scientific production (Dutton & Jeffreys, 2010). Specifically, e-Research refers to the advanced and intensive use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) to produce, manage and share scientific data in a collaborative context that is geographically distributed through «Collaboratories» (virtual spaces to implement research) or platforms such as Grid computing (a distributed system of computers to increase the storage and computing capacity of a research study).

This article examines the results of an investigation that had as its objective to create a diagnostic of the state of e-Research in the field of Communication Sciences in Ibero-America. Although it is generally understood that the acceptance and incorporation of an innovation is not an instantaneous act (Rogers, 2003), previous studies have found a positive attitude among social researchers towards e-Research (Dutton & Meyer, 2008), especially towards generic services and Web 2.0 platforms (Procter & al., 2010; Ponte & Simon, 2011). This reveals a rapid incorporation of many e-Tools (software, hardware and digital devices) despite some resistance to this change, expressed both culturally (Arcila, 2011) as well as in the scientific publication and production industry (Cuel & al., 2009). In this case, even though researchers from the social and human sciences are aware of the existence of the new paradigm known as e-Science (Dutton & Jeffreys, 2010), it is the exact and natural sciences –such as the High Energy Physics academic community mentioned by Gentil-Beccott and others (2009)– that have greater experience in the introduction and use of ICTs in research.

As stated by De Filippo et al. (2008), the groups that maintain a higher level of collaboration have significant potential as researchers. In fact, mainly these groups and local experts that help make possible the incorporation of technological innovations in the areas of scientific creation and production (Stewart, 2007). It is possible to affirm that the use of ICTs has serious implications in the quality and value of research (Borgman, 2007) and is now part of the success factors required for participation in Research and Development programs (Cuadros & al., 2009). In this respect, Bernius (2010) has highlighted that the open access made possible by the use of ICTs is an effective instrument for improving the management of scientific content. On the other hand, Liao (2010) has confirmed that a relationship exists between intense scientific collaboration and greater quality in the research, represented by the number of citations of a study, its impact factor, funding obtained, etc. One example of this type of scientific collaboration is the Codila Model and its later adaptation, Codila 2.0 (Collaborative Distributed Learning Activity). This program was first used in 2008 as part of an initiative for the integration of research and cooperation in software engineering, which was named «Latin American Collaboratory of eXperimental Software Engineering Research» (LCXSER).

In the field of Communication Studies, the explosion of new digital media seems to have awoken a growing enthusiasm among researchers to analyze both the messages involved as well as the subjects that produce and receive these messages. In this sense, it appears that the greater volume of information produced by academics around the globe requires increased efforts for the preservation of this data and for researchers to engage in collaborative work. The globalization of scientific work has resulted in making the use of advanced digital technologies imperative. However, a general analysis of e-Research in the discipline of Communication Studies in the Ibero-American region indicates that this is an area that is still very young and requires a lot of investment and effort to reach the levels of the other disciplines that have traditionally made intensive use of ICTs, such as the High Energy Physics academic community in Latin America that has already demonstrated strong development in the adoption of e-Research tools and methods (Briceño, Arcila & Said, 2012).

Regarding content, information sources and compiling data, even if there exists concern around advances made in this area (Jankowski & Caldas, 2004) alongside important online resources for academics (Codina, 2009), very few specific experiences of e-Research in the field of Communication Studies have been published. Among these are examples of research from the United States of America and the United Kingdom, with both countries having national organizations designed to promote e-Social Science: the National Science Foundation Office of Cyberinfrastructure in the USA and the National Centre for e-Social Science in the UK. One of the initiatives from this latter organization is the MiMeG (Mixed Media Grid) Project, finished in 2008 and based at the University of Bristol and King’s College London. This program aims to generate techniques and tools for social scientists with the goal of analyzing audiovisual qualitative data and related materials in a collaborative manner. Another program focused on integrating media management with Grid platforms is the proposal by Perrott, Harmer y Levis (2008) to create a network infrastructure for the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC).

This state of affairs poses crucial questions related to the future of scientific research in this academic field in Ibero-America. Are researchers adapting investigations in Communication Studies to the new methods of e-Research? What are the attitudes of communication researchers towards e-Research? How are e-Tools changing practices and methods in this scientific community? The answers to these questions can be used for the configuration of policies that stimulate scientific production in communication and to establish an important precedent for areas of study and research.

2. Method

With the goal of depicting the current state of e-Research in the area of Communication Studies in Ibero-America, an exploratory study that used descriptive methodologies1 was conducted. To collect data, an online survey was designed for researchers in the region with the goal of describing: 1) The attitudes of researchers towards e-Research; 2) The use of e-Tools; 3) Practices and methods related to e-Research. Among the questions posed to academics were their perceptions of the benefits of ICTs for scientific work, the type of e-Tools and platforms used, their access to advanced digital resources, habits in collaborative work and the methods for sharing the knowledge generated by e-Research. This article includes the general results of the survey and examines the main trends and variables that are evident in the answers of those surveyed.

In September 2011 the survey was submitted to a validation by a panel of experts and a pilot test. In addition a blog of the project was started online to share the progress of the research project. Once the instrument was reviewed and adjusted and versions were produced in both Spanish and Portuguese, the survey was distributed among specialist networks during the months of November and December of 2011. Each network contained a different number of members and each member received an email that invited them to take part in the survey. These included: ALAIC (253 members); AE-IC (557), the Latin Society for Social Communication (128); Friends of the Latin Magazine for Social Communication (583) and the Ibero-American Academic Network in Communication (104). In total 1,625 communication researchers received an invitation to participate in the study (a number that is unknown is one that represents the universe of communication researchers in Ibero-America, although it is possible that there were duplications among members of the networks), of which 316 responses were received (a rate of effective response rate of 19.44%), which represents a population of clinical cases.

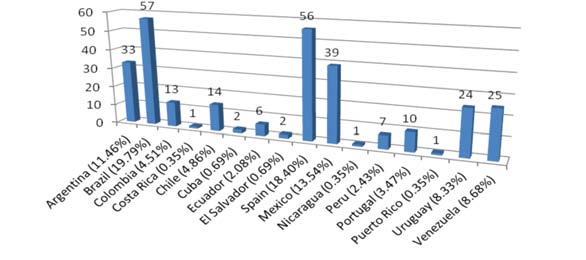

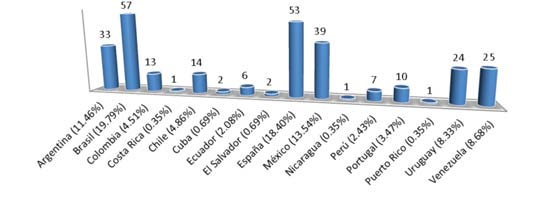

These cases involved researchers from almost all of the countries in the Ibero-American region, with the exception of participants from Bolivia, Guatemala, Honduras, Panama, Paraguay and the Dominican Republic. As can be observed in figure 1 (geographical distribution of cases studied), countries such as Brazil (19.79%), Spain (18.4%), Mexico (13.54%) and Argentina (11.46%) make up an important fraction of the sample. The researchers (54.3% females and 45.7% males) had an average age of 43 and a range of academic qualifications: bachelor’s degree (18.21%), postgraduate diploma (5.84%), master’s degree (27.49%) and doctorate (48.45%), with the majority having this final academic level. A small number of respondents were affiliated to international networks such as IAMCR, ICA or ECREA, but the majority indicated that they were part of regional networks such as ALAIC (and in fewer numbers regional networks such as FELAFACS, IBERCOM, ULEPICC, RAIC and the Latin Society of Social Communication) or in national research networks (AE-IC, Invecom, AMIC, SOPCOM, REDCOM, INTERCOM, SBPJor, FNPJ, SEICOM, etc.). In addition to the descriptive analysis of the data, tests in statistical meaning (specifically using Fisher’s exact test) to determine the associations between the main variables of the study (specifically between the intensive use of data, age and academic qualification) were conducted as part of the study.

Even if the respondents are part of almost all of the research lines that ALAIC is involved in, an important percentage of researchers stated that their academic work is related to the area of Internet and the Information Society (39.24%) which demonstrates proximity and affinity with the area of e-Research. This reality, combined with the fact that the survey was filled out online (through a self-selection process of participants) demonstrates the existence of this bias and the difficulty of generalizing the results from the group of researchers that participated in the study. However it also demonstrates the growing interest among communication academics in new technologies.

3. Analysis and results

The incorporation of digital technologies, specifically the use of personal computers and office software, is now common in all scientific fields because it is no longer possible to imagine academic or research activities without tools such as email or word processors. However, these tools represent an initial stage of the influence of ICTs in research and without a doubt emulate traditional research methods. What can be observed in the results of the study is that this first stage of influence by ICTs is evident and habitual in communication research, but that in the next stage, the intensive and advanced use of ICTs is only just beginning to be incorporated. The results of this survey show clear trends in the attitudes of scientists in this field towards e-Research, the e-Tools that they are using and their practices and methods in relation to e-Research.

An initial look shows that the respondents demonstrated a very positive attitude towards e-Research, with 69.14% classifying the use of digital technologies in research as «extremely beneficial». In this manner, around half of respondents agreed with the statements «e-Research increases my individual productivity» (47.78%), «e-Research increases the productivity of my research group» (53.48%) and «many of the new scientific questions in my field of study will require the use of e-Research tools» (47.78%). These figures show that for a considerable number of academics, there is a direct relationship between the quality of research and the use of ICTs. According to these researchers, the digital tools for e-Research are «useful» (70.25%), but more than half consider that further information and training in this area is necessary (52.85%).

An interesting piece of data is that 43.67% of communication academics are aware that e-Research tools imply new challenges in the area of research ethics. Likewise, it also brings up the issue of problems in financing these tools, give that only 6.96% of respondents considered that in their country or region there are sufficient funds provided for the development of e-Research. In this sense, respondents were clear in stating that this financing should go more towards the development of projects and studies based on e-Research methods, such as collaborative projects (71.2%), than investment in e-Infrastructure such as advanced networks, internet, computers, etc (20.57%). This represents a strong interest in stimulating scientific practices/methods instead of improving technical infrastructure. On this last point, the majority of researchers (64.77%) stated that their institution is connected to advanced networks (Internet Académica; Internet2) while 17.05% said that their institutions were not part of these networks. A considerable percentage (18.18%) responded that they did not know if their institution used these types of networks, which demonstrates that these academics have had very little involvement with advanced e-Tools.

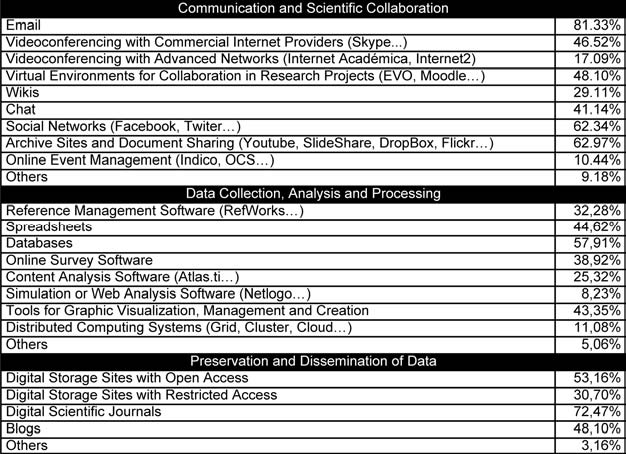

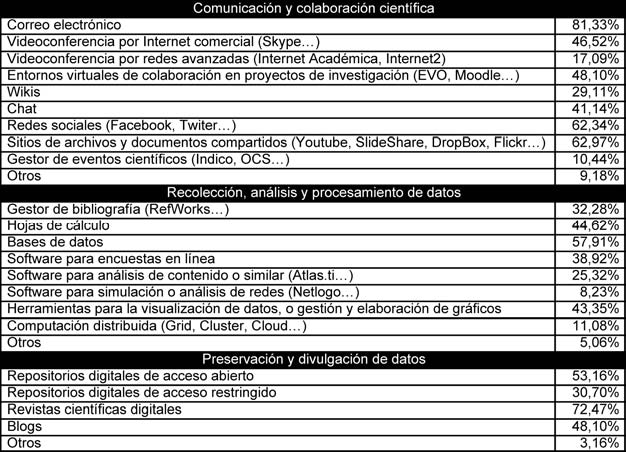

Communication researchers in Ibero-America consider that they frequently use (52.65%) or intensively use (31.06%) the so-called e-Tools (software, hardware and digital devices for collecting, processing and diffusing data) for a variety of research tasks. As can be seen in table 1, they demonstrated that they had used at least one e-Tool for scientific communication and collaboration, especially email (81.33%), archive sites and document sharing (62.97%) and social networks (62.34%). Similarly, an important number of respondents used video conferencing with commercial internet providers such as Skype (46.52%), chats (41.14%) and virtual environments for collaboration (48.10%). Apart from this last tool, which includes platforms such as EVO and Moodle (a virtual education tool but one that is also used for the design of collaborative projects (Arroyave & al., 2011), all of the other applications are commercial internet tools that have a wide diffusion amongst users. Tools such as video conferencing with advanced networks (17.09%) or organizing online scientific events (10.44%) are less commonly used.

Regarding the use of e-tools for data collection, analysis and processing, more than half of respondents (57.91%) stated that they had used databases while less respondents (44.62%) used spreadsheets and software for data visualization (43.35%). Other e-Tools such as online survey software (38.92%), reference management software (38.92%), reference management tools (32.28%) and content analysis software (25.32%) were also mentioned. However, it is important to note that simulation programs (8.23%) and distributed computing platforms like Grids or Clusters (11.08%) are not commonly used by researchers. In the area of preserving and disseminating data, many communication researchers opt for digital scientific journals (72.47%) and an important number use open access online data storage (53.16%) –with less respondents using restricted access storage– and blogs (48.10%).

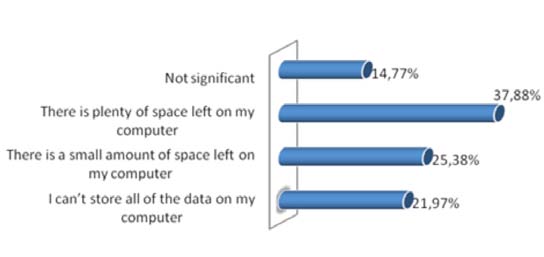

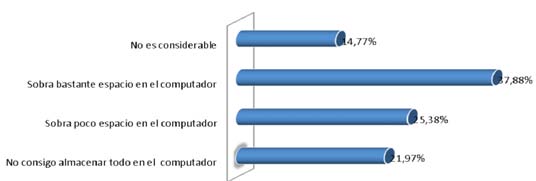

The results of the survey show that until now a large amount of researchers have used different digital tools, however if the concept of e-Research is examined (advanced and intensive use of ICTs), it is clear that a large number of the tools are for extensive use and often commercial. What represents intensive and advanced use of ICTs is most probably the quantity of data processed and the strength of the scientific collaboration. In this sense, the quantity of data produced by the use of e-Tools was a key question to make a diagnostic of the current state of e-Research in the communication field. As can be seen in figure 2, only 21.97% answered that the space in their personal computer was not sufficient to store and process data that they were producing in their research, while 37.38% stated that they still had a lot of space on their computers after storing data from their research.

Considering that the intensive use of data is the most important category in our exploratory study (given the proposal that it demonstrates real advances in the use of e-Research in the field), these results were crossed with variables in age and educational level to determine if a significant statistical relationship exists between them and whether age and educational level influence in a direct manner the intensive use of data by researchers. For this statistical analysis Fisher’s exact test was used to create a cross tabulation contingency table, concluding that: 1) there was no association observed between the categories of intensive use of data and educational level categories given that the value «p» in the contingency tables for each one of the variable categories of age range was greater than 0.05; 2) no association was observed between the categories of intensive use of data and the categories defined by age range without including the academic level of the respondent, given that the value «p» in the contingency tables for each one of the categories in academic levels was greater than 0.05.

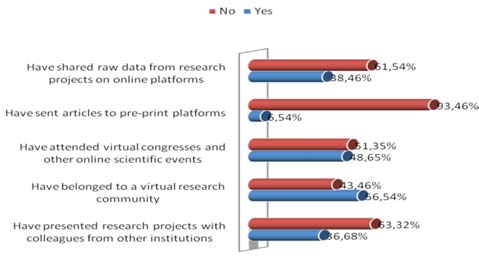

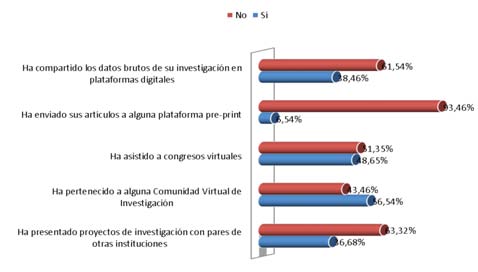

Regarding the area of scientific collaboration (figure 3), the data shows that an important percentage of researchers carry out academic work in an isolated manner, demonstrating that the dream of a geographically distributed academic community is still far from being a reality. This statement is based on the fact that 63.32% of communication researchers in Ibero-America have not presented any research project with peers from other institutions that are different to their own and more than half of these (51.25%) have not been a part of a virtual academic community. These findings demonstrate the possibility of more geographically distributed groups in future –and more intensive– collaborations occurring, which will result in the presentation of joint projects as well as the organization of specialized events. When academics were asked about their experiences in virtual research communities, classifying their satisfaction with these experiences on a scale between 1 and 10, the majority of respondents demonstrated high levels of satisfaction, scoring them with 7 (16.20%), 8 (33.1%) y 9 (18.31%). Researchers stated that in these communities, the protocols or rules of collaboration had generally been established during the process (64.79%) by those involved and in very few cases these guidelines had been verbally discussed (11.27%) or written (13.38%).

One aspect that is related to not just scientific collaboration but also to the dissemination of data is the direct publication (without passing for peer reviewing) of manuscripts and the distribution of primary or raw data from research projects. Both indicators show the advances made by e-Research in this field. Firstly, it is significant that communication researchers (93.46%) do not have the habit of sending their manuscripts to pre-print (digital) platforms even though it is widely known that publication times for traditional journals are very long (due to evaluation of manuscripts, printing, etc.) and that on many occasion fellow researchers are waiting for results from their colleagues so that they can advance in their own studies. It is interesting to note that less than half of researchers (38.46%) share their raw data in digital platforms, which can be indicative of predominantly individual work in the field. However, this has a significant impact on the results as it does not allow for their re-use (for example in replications of studies), comparisons with other data (verification) or more in-depth studies (for example through mining the data).

These results cover the different dimensions of e-Research in Communication Studies (attitudes, tools and practices) and can act as a summary of the current state of e-Research in Ibero-America. Below is a discussion of the results, comparing the field of Communication Studies with other disciplines and formulating final considerations that can serve as a guide for the incorporation of digital technologies in research.

4. Discussion and conclusions

If communication research is a relatively young field, there are important reasons to think that it is necessary to incorporate advanced methods and tools to reconfigure the discipline and even aspire to propose new objects of study. The results of this exploratory study, that is delimited to the Ibero-American region, demonstrates that there is a strong disposition among academics towards e-Research, a trend that seems to have extended to all of the social sciences. In the study conducted by Dutton and Meyer (2008), social researchers from the United Kingdom show a positive attitude towards e-Research and more than half of them (58.7%) believe that many of the new questions in research will require new tools, a point of view that is shared by academics in the Ibero-American region. This demonstrates, for example, that communication research continues to be a field that is highly dependent on general research in social sciences, as affirmed by Jensen y Jakowsky (1993) when they referred to qualitative methodologies. On the other hand, similar to what is occurring in other social disciplines, Communication Studies is a field that is very suited to the implementation of advanced digital technologies.

This last idea is linked to results that show communication researchers in Ibero-America are highly aware of: 1) the need for their own funding for e-Research projects; 2) the ethical challenges implied by the use of e-Tools and the methods involved in geographically distributed collaboration. With these concerns, it was hoped researchers would demand greater information and training in these areas. Currently, the countries in the region do not have specialist government agencies that promote e-Research and in the case of Communication Studies, the specialist scientific associations (ALAIC, AE-IC, etc.) are only just starting to formalize actions in this area, which explains the lack of development of e-Research in the discipline. Even if they are not specifically focused on Communication Studies, regional organizations such as the Latin American Cooperation for Advanced Networks (RedClara) have discovered the importance of developing what is known as e-Infrastructure as well as the dynamization of scientific practices of certain academic communities through their participation in advanced networks.

In this sense, the lack of public policies and support from individual countries to encourage, invest in and include Communication Studies in the development of e-Research makes it vital for universities to establish links between colleagues and with companies and industry to seek strategies that improve geographically distributed training, exchanges, participation and collaboration through the use of advanced technology networks. As proposed by Stewart (2007), these policies should focus on local research groups and experts who will be more effective in promoting the advanced use of ICTs in research.

On the other hand, in line with the work of Codina (2009), the results of this survey can serve to help develop a guide that details the e-Research resources and tools that academics are currently using. This will not only strengthen the use of existing tools but will also encourage the adoption of e-Tools that can greatly support the work of researchers, such as Grid systems or simulators, that have a low level of acceptance among the community. Likewise, the data can also be used to contrast these practices with other communities from the same region, especially the High Energy Physics academic communities in Latin America, who have demonstrated the most intensive use of e-Tools in scientific collaboration. A previous study (Briceño, Arcila & Said, 2012) showed that in this academic community there was a strong trend in the use of tools for online academic publication and shared management of data, yet results demonstrated a low interest in the use of commercial, mass and popular tools. This is in marked contrast to communication researchers surveyed in this present study, who demonstrated a high use (more than 60%) of social networks such as Facebook and Twitter and file-sharing sites such as Youtube, Slideshare, Dropbox and Flickr.

Even if there was no relationship found between age and educational level with the intensive and advanced use of ICTs in research – in marked difference to the results from the study of Procter & al. (2010) of researchers in the United Kingdom that found significant associations between the adoption of Web 2.0 platforms and the age, sex and academic position of the person – it can be stated that there are difficulties, some of a technical nature, that result in communication researchers in Ibero-Americana preferring commercial tools instead of advanced tools. This was demonstrated in the use of videoconference providers, in that there was a difference of almost 30% in favor of Skype. This last point however is consistent with the results found by Procter & al. (2010) in that a significant number of other researchers who participated in the study preferred the use of «generic» tools than «specific» ones.

In the case of Ibero-America, the limitations are not just of a technological nature but also a lack of knowledge of certain platforms. In the case of pre-print systems for publishing scientific research, less than 7% of researchers that responded had used them, significantly contrasting with the results of the physicists involved in high energy studies that demonstrate a high level of use of spaces such as arXiv (48.39%) or SPIRES (41.94%), sites that do not require extra technical knowledge. Additionally, given that at least half of the researchers stated that they used open access digital storage, it is evident that the existence of a specialist storage site for communication would stimulate their use of such tools.

This data suggest that there is strong level of pre-disposition towards e-Research among communication researchers in Ibero-America, but there are factors that make its implementation difficult. This is evident if it is taken into account that the term «e-Science» does not just refer to the use of commercial digital technologies, but above all the incorporation of advanced computing tools for the management of large quantities of data and to intensify scientific collaboration. This is linked to the attitudes and habits of researchers in their practices and methods of working, including multi-disciplinary teams, peer reviewing and joint publications, among others. Applying the Rogers curve (2003) in this case, apart from the innovators it also includes the first followers in the use of new tools for research and that generate new practices. In this sense, it is vital that efforts are focused on the creation of specialist organizations in the region and the establishment of policies (financing, training, etc.) directed at strengthening research activity through the use of platforms such as Internet2 or Grid computing systems. Similarly, it is necessary (as the researchers in the study noted) to increase incentives that encourage the creation of geographically distributed collaborative projects (much less than half of those surveyed responded that they had presented a research project with peers from other institutions), which can strengthen the creation of virtual research communities and increase the number of collaborations in the field.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this study would like to thank the anonymous reviewers whose comments contributed to improving the quality of the research undertaken. They would also like to thank the Observatory in Media and Public Opinion and the Department for Investigation, Development and Innovation (DIDI) at the Universidad del Norte (Colombia) for their support of this study.

Notes

1 This study also had participation from Ignacio Aguaded (Spain), Cosette Castro (Brazil), Marta Barrios (Colombia), Martín Díaz (Colombia) y Elias Suárez (Colombia).

2 The 22 groups that make up the ALAIC can be consulted at www.alaic.net.

References

Arcila, C. (2011). La difusión digital de la investigación y las resistencias del mundo científico. In E. Said (Ed.), Migración, desarrollo humano, internacionalización y digitalización. Retos del siglo XXI. (pp. 325-334). Barranquilla: UniNorte.

Arroyave, M., Velásquez, A., & al. (2011). Laboratorios remotos: diversos escenarios de trabajo. Disertaciones, Anuario Electrónico de Estudios en Comunicación Social, 4, 2, 83-94.

Atkins, D.E., Droegemeir, K.K., & al. (2003). Revolutionizing Science and Engineering through Cyberinfrastructure: Report of the National Science Foundation Blue-Ribbon Advisory Panel on Cyberinfrastructure. Washington, DC: National Science Foundation.

Bernius, S. (2010). The Impact of Open Access on the Management of Scientific Knowledge. Online Information Review, 34, 4, 583-603. (DOI: 10.1108/14684521011072990).

Borgman, C. (2007). Scholarship in the Digital Age. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Briceño, Y., Arcila, C. & Said, E. (2012). Colaboración y comunicación científica en la comunidad latinoamericana de físicos de altas energías. E-Colabora, 2, 4, 131-144.

Codina, L. (2009). Ciencia 2.0: Redes sociales y aplicaciones en línea para académicos. Hipertext.net, 7.

Cuadros, A., Martínez, A. & Torres, F. (2009). Determinantes de éxito en la participación de los grupos de investigación latinoamericanos en programas de cooperación científica internacional. Interciencia, 33, 11, 821-828.

Cuel, R., Ponte, D. & Rossi, A. (2009). Towards an Open/Web 2.0 Scientific Publishing Industry? Preliminary Findings and Open Issues. Informe Técnico de la University de Trento. (http://wiki.liquidpub.org/mediawiki/upload/b/b3/CuelPonteRossi09.pdf) (05/10/2012).

De Filippo, D., Morillo, F. & Fernández, M.T. (2008). Indicadores de colaboración científica del CSIC con Latinoamérica en bases de datos internacionales. Revista Española de Documentación Científica, 31, 1, 66-84.

Dutton, W. & Jeffreys, P. (Eds.) (2010). World Wide Research. Reshaping the Sciences and Humanities. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Dutton, W.H. & Meyer, E.T. (2008). e-Social Science as an Experience Technology: Distance From, and Attitudes Toward, e-Research. 4th International Conference on e-Social Science. Manchester (UK), 18-06-2008. (www.ncess.ac.uk/events/conference/programme/thurs/1bMeyerb.pdf) (01/10/2011).

Gentil-Beccot, A., Mele, S. & al. (2009). Information Resources in High-Energy Physics: Surveying the Present Landscape and Charting the Future Course. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60, 1, 150-160

Hey, T., Tansley, S. & Tolle, K. (Eds.) (2009). The Fourth Paradigm. Data-Intensive Scienti?c Discovery. Redmond Washington: Microsoft Research.

Jankowski, N. & Caldas, A. (2004). e-Science: Principles, Projects and Possibilities for Communication and Internet Studies. Etmaal van Communicatiewetenschap Day of Communication Science. Holland: Universidad de Twente.

Jensen, K.B. & Jankowski, N.W. (1993). Metodologías cualitativas de investigación en comunicación de masas. Barcelona: Bosch.

Liao, C. (2010). How to Improve Research Quality? Examining the Impacts of Collaboration Intensity and Member Diversity in Collaboration Networks. Scientometrics, 86, 747-761.

Nentwich, M. (2003). Cyberscience: Research in the Age of the Internet. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences.

Neylon, C. & Wu, S. (2009). Open Science: Tools, Approaches, and Implications. XIV Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing. Hawaii (USA), 09-01-2009. (http://psb.stanford.edu/psb-online/proceedings/psb09/workshop-opensci.pdf) (05/10/2012).

Perrott, R., Harmer, T. & Levis, R. (2008). e-Science Infrastructure for Digital Media Broadcasting. Computer, November, 67-72.

Ponte, D. & Simon, J. (2011). Scholarly Communication 2.0: Exploring Researchers’ Opinions on Web 2.0 for Scientific Knowledge Creation, Evaluation and Dissemination. Serials Review, 37, 3, 149-156.

Procter, R., Williams, R. & al. (2010). Adoption and Use of Web 2.0 in Scholarly Communications. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A-Mathematical Physical, 368, 4.029-4.056.

Rogers, E.M. (2003). Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press.

Stewart, J. (2007). Local Experts in the Domestication of Information and Communication Technologies, Information. Communication & Society, 10, 4, 547-569

Waldrop, M. (2008). Science 2.0. Is Open Access Science the Future? Is Posting Raw Results Online, for all to See, a Great Tool or a Great Risk? Scientific American Magazine, 21 de abril. (www.sciamdigital.com/index.cfm?fa=products.viewissuepreview&articleid_char=3e5a5fd7-3048-8a5e-106a58838caf9bf7) (01-11-2009).

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

La e-investigación está cambiando las prácticas y dinámicas de la investigación social, gracias a la incorporación de herramientas digitales avanzadas para el procesamiento de datos y el incremento de la colaboración científica. Estudios anteriores muestran una actitud positiva de los científicos hacia la e-investigación y la rápida incorporación de herramientas digitales para el trabajo académico, a pesar de las resistencias culturales al cambio. Este artículo examina el estado actual (actitudes, herramientas y prácticas) de la e-investigación en el campo de los estudios en comunicación en Iberoamérica. Un total de 316 investigadores de la región respondieron una encuesta en línea durante los últimos dos meses de 2011. Los resultados confirman una actitud positiva hacia la e-investigación y un uso frecuente de las e-herramientas. Sin embargo, la mayor parte de ellos aseguran usar e-herramientas básicas (como correo-e, videoconferencia comercial, software de oficina o redes sociales), en vez de usar tecnologías avanzadas para procesar gran cantidad de datos (como Grids, programas de simulación o Internet2) o de incorporarse a comunidades virtuales de investigación. Algunos investigadores afirmaron tener un uso «intensivo» (31%) o «frecuente» (53%) de las e-herramientas, pero solo el 22% aseguraron que la capacidad de su computador personal era insuficiente para manejar y procesar los datos. El artículo concluye evidenciando una brecha importante entre la e-investigación en comunicación y en otras disciplinas, y establece recomendaciones para su implementación en la región.

1. Introducción

El paradigma de la «e-Ciencia» está actualmente transformando las dinámicas y las herramientas de la investigación científica (Hey & al., 2009), incrementando las posibilidades de los investigadores y permitiéndoles alcanzar y descubrir nuevos objetos de estudio. Otros términos como «ciberciencia» (Nentwich, 2003) o «ciberinfraestructura» (Atkins Report, 2003) (e-Infraestructura en el ámbito europeo) se han utilizado para referirse a estos cambios en los modos de hacer científicos. Asimismo, más recientemente encontramos los conceptos de Ciencia 2.0 (Waldrop, 2008) o Ciencia Abierta (Neylon & Wu, 2009), para describir la utilización de herramientas de la llamada web 2.0 (participación activa y descentralizada de los usuarios) y la apertura del proceso científico a partir de prácticas de libre distribución de conocimientos, respectivamente. Encontrarnos conceptos como e-investigación que parecen apuntar más concretamente a las nuevas prácticas y dinámicas de producción científica (Dutton & Jeffreys, 2010). Específicamente, la e-investigación se refiere al uso avanzado e intensivo de las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación (TIC) para producir, manejar y compartir datos científicos en un contexto de colaboración geográficamente distribuido a través, por ejemplo, de «colaboratorios» (espacios virtuales para la ejecución de la investigación) o de plataformas como Grid (computación distribuida para aumentar la capacidad de almacenamiento y cómputo).

Este artículo examina los resultados de una investigación cuyo objetivo fue diagnosticar el estado de la e-investigación en el campo de las ciencias de la comunicación en Iberoamérica. Aunque sabemos que la aceptación e incorporación de una innovación no es un acto instantáneo (Rogers, 2003), estudios anteriores muestran una actitud positiva de los investigadores sociales hacia la e-investigación (Dutton & Meyer, 2008), especialmente hacia servicios y plataformas genéricas de la Web 2.0 (Procter & al., 2010; Ponte & Simon, 2011), y revelan la rápida incorporación de muchas e-herramientas (software, hardware y dispositivos digitales para levantamiento, procesamiento y difusión de datos) a pesar de la presencia de algunas resistencias al cambio, tanto de tipo cultural (Arcila, 2011) como en términos de la industria de producción y publicación científica (Cuel & al., 2009). En este caso, aun cuando las ciencias sociales y humanas son conscientes de la existencia de este nuevo paradigma llamado e-Ciencia (Dutton & Jeffreys, 2010), las ciencias exactas y naturales –como la física de altas energías mencionada por Gentil-Beccott y otros (2009)– tienen una mayor experiencia en el uso e implantación de las TIC en la investigación.

De acuerdo con De Filippo y otros (2008) los grupos que mantienen una mayor colaboración tienen un potencial investigador significativo. De hecho, son principalmente estos grupos y sus expertos locales los que posibilitan la incorporación de las innovaciones tecnológicas en las formas de creación y producción científica (Stewart, 2007). Es posible asegurar que el uso de las TIC tiene serias implicaciones en la calidad y valor de la investigación (Borgman, 2007) y que son parte de los factores de éxito para participar en programas de I+D (Cuadros & al., 2009). Al respecto, Bernius (2010) ha señalado que el acceso abierto posibilitado por las TIC es un instrumento efectivo para la mejora del manejo del conocimiento científico. Por su lado, Liao (2010) ha confirmado que existe correspondencia entre una colaboración científica intensa y una mayor calidad en la investigación representada en el número de citas, factor de impacto, montos de la financiación, etc. Un ejemplo de colaboración científica para tomar en cuenta es el Modelo Codila y su adaptación Codila 2.0 (Collaborative Distributed Learning Activity) que se comenzó a usar desde 2008 como una iniciativa para la integración en investigación y cooperación en ingeniería del software y se denominó «Latin American Collaboratory of eXperimental Software Engenieering Research» (LCXSER).

En el campo de la comunicación, la explosión de nuevos medios digitales parece haber despertado un entusiasmo aun mayor dentro de los investigadores por el análisis tanto de los mensajes como de los sujetos productores y receptores de los mismos. En este sentido, parecería que un volumen mucho mayor de información producida por académicos alrededor del globo requiere un esfuerzo superior para la preservación de los datos y para el trabajo colaborativo. La globalización del trabajo científico hace imperativo el uso de las tecnologías digitales avanzadas, sin embargo, una mirada general a la e-investigación de la comunicación en la región iberoamericana indica que esta es un terreno muy joven donde se requiere mucha inversión y esfuerzo para alcanzar los niveles de otras disciplinas que tradicionalmente han hecho un uso intensivo de las TIC, como es el caso de la física de altas energías, que en América Latina muestra un mayor desarrollo (Briceño, Arcila & Said, 2012).

En cuanto a contenidos, fuentes de información y compilaciones de datos, aunque existe tanto una preocupación (Jankowski & Caldas, 2004), como importantes recursos en línea para académicos (Codina, 2009), se conocen pocas experiencias específicas de e-investigación en el campo de la comunicación, entre las cuales podemos encontrar algunos progresos en Estados Unidos y Reino Unido, ambos países con sendas organizaciones especializadas en promover la e-Ciencia Social: la National Science Foundation Office of Cyberinfrastructure y el National Centre for e-Social Science, respectivamente. Uno de estos esfuerzos es el Proyecto MiMeG (MixedMediaGrid), finalizado en 2008 y basado en la Universidad de Bristol y en el King’s College London. Este programa apuntaba a generar herramientas y técnicas para científicos sociales con el fin de analizar datos cualitativos en formato audiovisual y materiales relacionados, de forma colaborativa. Otro programa, enfocado a integrar el manejo de medios con plataformas Grid, es la propuesta de Perrott, Harmer y Levis (2008) para crear una infraestructura de redes para la British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC).

Este panorama plantea preguntas cruciales relacionadas con el futuro de la investigación científica en este campo del saber en Iberoamérica: ¿se están adaptando los estudios en comunicación a las nuevas dinámicas de la e-investigación?, ¿cuál es la actitud de los investigadores de la comunicación ante la e-investigación?, ¿cómo están cambiando las e-herramientas, las prácticas y las dinámicas de esta comunidad científica? La respuesta a estas interrogantes puede orientar la configuración de políticas que estimulen la producción científica en comunicación y establecer un precedente importante para una línea de trabajo e investigación.

2. Método

Con el fin de conocer el estado actual de la e-investigación de la comunicación en Iberoamérica, se realizó un estudio exploratorio de tipo descriptivo1; para la recogida de datos se diseñó una encuesta en línea dirigida a investigadores de la región, con el objeto de describir: 1) las actitudes de los investigadores hacia la e-investigación; 2) el uso de e-herramientas; 3) las prácticas y dinámicas relacionadas con la e-investigación. Entre las ciuestiones expuestas a los académicos están sus percepciones sobre los beneficios de las TIC para la tarea científica, el tipo de e-herramientas y plataformas utilizadas, el acceso a recursos digitales avanzados, los hábitos de trabajo colaborativo y las vías para compartir el conocimiento generado. Este artículo da a conocer los resultados generales de la encuesta y examina las principales tendencias y variables que influyen en las respuestas de los encuestados.

En septiembre de 2011, se realizó tanto una validación por medio de panel de expertos, como una prueba piloto de la encuesta, y se puso en línea un blog del proyecto para compartir los avances de la investigación. Una vez revisado y ajustado el instrumento, en versiones en español y portugués, se procedió a distribuir la encuesta entre varias redes especializadas durante los meses de noviembre y diciembre de este mismo año. Cada red contenía un número de suscriptores a los que se les fue enviado un correo electrónico con la invitación: Lista de ALAIC (n=253), lista de la AE-IC (n=557), lista de la Sociedad Latina de Comunicación Social (n=128), lista de Amigos de la Revista Latina de Comunicación (n=583) y lista de la Red Académica Iberoamericana de Comunicación (n=104). En total fueron enviadas 1.625 invitaciones a investigadores para que participaran en el estudio (un número que desconocemos si es representativo al universo de investigadores de la comunicación en Iberoamérica y en el que es posible que estén incluidos miembros duplicados), de las cuales se obtuvieron 316 respuestas (tasa de respuesta efectiva del 19,44%), que constituyen una población de casos clínicos.

En estos casos encontramos investigadores de casi todos los países de la región Iberoamericana, a excepción de Bolivia, Guatemala, Honduras, Panamá, Paraguay y República Dominicana. Tal como se observa en la figura 1 (distribución geográfica de los casos estudiados), países como Brasil (19,79%), España (18,4%), México (13,54%) y Argentina (11,46%), conforman una importante fracción de nuestra muestra. Los investigadores (54,3% mujeres y 45,7% hombres) mostraron una edad promedio de 43 años y diferentes grados académicos: licenciatura (18,21%), especialización (5,84%), maestría (27,49%) y doctorado (48,45%), predominando esta última titulación. Un bajo número respondió estar afiliado a asociaciones internacionales como Iamcr, Ica, Ecrea, pero la mayor parte señaló estar en algunas regionales como Alaic, y en menor medida: Felafacs, Ibercom, Ulepicc, Raic, Sociedad Latina de Comunicación Social; o en redes nacionales de investigación (AE-IC, Invecom, Amic, Sopcom, Redcom, Iintercom, SBPJor, Fnpj, Seicom, etc.). Adicionalmente al análisis descriptivo de los datos, se realizaron pruebas de significación estadística (específicamente el test exacto de Fisher) para determinar las asociaciones entre las variables principales del estudio (concretamente, entre el uso intensivo de datos y la edad y el nivel académico).

Aunque los encuestados forman parte prácticamente de todas las líneas de investigación propuestas por ALAIC2, un grueso importante de los investigadores aseguró que su trabajo académico está relacionado con el campo de Internet y Sociedad de la Información (39,24%), lo que crea seguramente proximidad y afinidad con el tema de la e-investigación. Esta realidad, aunada al hecho de que la encuesta se realizó vía Internet (con un proceso de autoselección), pone de manifiesto el sesgo existente y la dificultad de generalizar los resultados a todos los investigadores, pero también da cuenta del creciente interés de los estudiosos de la comunicación por las nuevas tecnologías.

3. Análisis y resultados

La incorporación de tecnologías digitales, esto es, el uso de ordenadores personales y software de oficina, resulta un hecho en todos los campos científicos, tanto que no es posible imaginar la actividad académica o de investigación sin herramientas como el correo electrónico o el procesador de texto. Estas herramientas pertenecen, sin embargo, a una primera etapa de la influencia de las TIC en la investigación que, a todas luces, termina por emular la investigación tradicional. Lo que se observa en los resultados es que esta primera etapa de influencia de las TIC es notoria y habitual en la investigación de la comunicación, pero que la etapa siguiente, la del uso intensivo y avanzado de esas mismas tecnologías, está apenas incorporándose. Los resultados de esta encuesta muestran tendencias claras sobre las actitudes de los científicos del campo hacia la e-investigación, las e-herramientas que están utilizando y sus prácticas y dinámicas en torno a la e-investigación.

Una primera mirada nos dice que los encuestados mostraron una actitud altamente positiva hacia la e-investigación, cuando el 69,14% de ellos la calificaron de «muy beneficioso» el uso de tecnologías digitales en la investigación. En este sentido, alrededor de la mitad de ellos coincidieron con afirmaciones como «La e-investigación aumenta mi productividad individual» (47,78%), «La e-investigación aumenta la productividad de mi grupo de investigación» (53,48%) o «Muchas de las nuevas preguntas científicas en mi campo de estudio requerirán del uso de herramientas de la e-investigación» (47,78%). Lo anterior muestra que para cierta parte considerable de los académicos, existe una relación directa entre la calidad de la investigación y el uso de las TIC. Según estos investigadores, las herramientas digitales para la e-investigación son «útiles» (70,25%), pero consideran que es necesaria más información y formación en el área (52,85%).

Un dato interesante es que el 43,67% de los estudiosos de la comunicación son conscientes de que las herramientas de la e-investigación implican nuevos retos en torno a la ética. Asimismo, están al tanto de los problemas de financiamiento, ya que solo el 6,96% consideraron que en su país o región se están destinando fondos suficientes para el desarrollo de la e-investigación. En este sentido, fueron claros en expresar que dicho financiamiento debería ir más hacia el desarrollo de proyectos y estudios basados en dinámicas de e-investigación, como es el caso de los proyectos colaborativos (71,2%) que a la inversión en e-Infraestructura, es decir, las redes avanzadas, Internet, ordenadores, etc. (20,57%). Lo anterior representa un mayor favorecimiento al estímulo de las prácticas/dinámicas científicas, y menos a la infraestructura técnica. Sobre este último punto precisamente, la mayor parte de los investigadores (64,77%) manifestaron que su institución sí estaba conectada a redes avanzadas (Internet Académica; Internet2), mientras que un 17,05% señalaron que no. Un porcentaje considerable (18,18%) dijo desconocer si su institución utilizaba este tipo de redes, lo que evidencia que este porcentaje de académicos ha tenido un escasísimo uso de herramientas realmente avanzadas.

Los investigadores de la comunicación en Iberoamérica consideraron que hacían un uso frecuente (52,65%) o intensivo (31,06%) de las llamadas e-herramientas (software, hardware y dispositivos digitales para levantamiento, procesamiento y difusión de datos) para varias tareas de investigación. En primer lugar, como se aprecia en el tabla 1, manifestaron haber usado al menos una e-herramienta de comunicación y colaboración científica, especialmente el correo electrónico (81,33%), sitios de archivos y documentos compartidos (62,97%) o redes sociales (62,34%). Asimismo, una parte importante manifestó hacer uso de videoconferencia por Internet comercial –como Skype– (46,52%), de chats (41,14%) y de entornos virtuales de colaboración (48,10%). Salvo esta última herramienta, en la que se incluyen plataformas como EVO o Moodle (herramienta de educación virtual pero también usada para el diseño colaborativo (Arroyave & al., 2011), todas las demás aplicaciones son herramientas de Internet comercial y de amplia difusión entre los usuarios. Herramientas como la videoconferencia por redes avanzadas (17,09%) o los gestores de eventos científicos (10,44%), son usadas en mucha menor medida.

Con respecto al uso de e-herramientas para la recolección, análisis y procesamiento de datos, observamos que más de la mitad de los investigadores (57,91%) aseguran haber hecho uso de bases de datos y, en menor medida, de hojas de cálculo (44,62%) y de herramientas para la visualización de datos (43,35%). Otras e-herramientas como software para encuestas (38,92%), gestores de bibliografía (32,28%) o software para el análisis de contenido (25,32%) fueron también mencionadas. Sin embargo, llama la atención que programas de simulación (8,23%) o plataformas de computación distribuida como Grids o Clusters (11,08%) sean de escaso uso entre los investigadores. En tanto al tema de preservación y divulgación de los datos, vemos que los investigadores de la comunicación han apostado por las revistas científicas digitales (72,47%) y que una importante parte de ellos usa los repositorios abiertos (53,16%) (en detrimento de los de acceso restringido) y los blogs (48,10%).

Como hemos visto hasta ahora gran parte de los investigadores han manifestado hacer uso de diferentes herramientas digitales; sin embargo, si abordamos la conceptualización de la e-investigación (uso avanzado e intensivo de las TIC), nos damos cuenta de que la mayor parte de dichas herramientas son de un uso extendido y muchas veces comercial. Lo que hace intensivo y avanzado el uso de las TIC es probablemente la cantidad de datos procesados y la fuerza de la colaboración científica. En este sentido, la cantidad de datos producto del uso de e-herramientas fue una pregunta clave para diagnosticar el estado actual de la e-investigación en el campo de la comunicación. Como vemos en la figura 2, apenas un 21,97% contestó que el espacio en su computador personal no era suficiente para almacenar y procesar los datos que estaban produciendo sus investigaciones, mientras que un 37,38% aseguró que sobra mucho espacio.

Considerando que el uso intensivo de datos es la categoría más importante en nuestro estudio exploratorio (ya que pone de manifiesto el avance real de la e-investigación en el campo), se cruzaron estos resultados con las variables de edad y el nivel educativo, para determinar si existía una relación estadísticamente significativa entre ellas, es decir, comprobar si la edad y el nivel educativo influían de manera directa en el uso intensivo o no de los datos por parte de los investigadores. Para este análisis estadístico se utilizó el Test exacto de Fisher para tablas de contingencia, concluyendo que: 1) No se observa asociación entre las categorías de uso intensivo de datos y las categorías del nivel de educación, ya que el valor «p» en las tablas de contingencia para cada una de las categorías de la variable edad por rangos es mayor que 0,05; 2) No se observa asociación entre las categorías del uso intensivo de datos y las categorías definidas para los rangos de edades, sin importar el nivel académico de la persona, ya que el valor «p» en las tablas de contingencia para cada una de las categorías del nivel académico es mayor que 0,05.

En lo que tiene que ver con la colaboración científica (figura 3), vemos que si bien un porcentaje importante de investigadores realizan su trabajo académico de forma remota, todavía se está lejos del ideal de una comunidad académica geográficamente distribuida. Esta última afirmación se desprende del hecho de que el 63,32% de los investigadores de la comunicación en Iberoamérica no han presentado nunca un proyecto de investigación con pares de otras instituciones diferentes a la suya propia y que más de la mitad de ellos (51,25%) no ha asistido a un congreso de forma virtual. Sin embargo, vemos que un 56,54% asegura haber pertenecido a alguna comunidad virtual de trabajo, lo que abona el terreno para que futuras –y más intensas– colaboraciones sean posibles, dando como resultado tanto la presentación de proyectos, como la organización de eventos especializados. Cuando se les preguntó a los académicos sobre su experiencia en la comunidad virtual de investigación, calificándola del 1 al 10, la mayoría mostró altos grados de satisfacción, puntuándola fundamentalmente en 7 (16,20%), 8 (33,1%) y 9 (18,31%). Los investigadores apuntan que en estas comunidades, los protocolos o reglas de colaboración han sido esencialmente establecidos sobre la marcha por ellos mismos (64,79%) y en muy pocos casos dichas reglas se han repetido (11,27%) o han estado escritas (13,38%).

Un aspecto que tiene que ver con la colaboración científica, pero también con la compartida y difusión de datos, es la publicación directa (sin pasar por revisión de pares) de los manuscritos y la distribución de los datos primarios o brutos de la investigación. Ambos indicadores pueden dar muestra del avance de la e-investigación en el campo. En primer lugar, es significativo que los investigadores de la comunicación (93,46%) no tengan por costumbre enviar sus manuscritos a plataformas pre-print, aun cuando sabemos que los tiempos de publicación tradicionales son muy largos (por evaluaciones, impresión, etc.) y que los pares en muchas ocasiones se encuentran a la espera de nuestros resultados para poder seguir avanzando en sus propios estudios. En segundo lugar, vemos que mucho menos de la mitad de los investigadores (38,46%) suelen compartir sus datos brutos en plataformas digitales, hecho que puede estar ligado al trabajo predominantemente individual en el campo, pero que resta significativamente potencia a los resultados, pues no permite su reutilización (por ejemplo, para réplicas), su contrastación (verificación) y un examen más profundo (por ejemplo, con la minería de datos).

Estos resultados abarcan diferentes dimensiones de la e-investigación de la Comunicación (actitudes, herramientas y prácticas) y pueden resumir su estado actual en Iberoamérica. A continuación realizamos la discusión de los resultados, contrastando el campo de la comunicación con otras disciplinas, y formulando consideraciones finales que puedan servir como guía para la incorporación de tecnologías digitales en la investigación.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

Si bien la investigación de la comunicación es un campo relativamente joven, existen importantes razones para pensar que es necesaria la incorporación de dinámicas y herramientas avanzadas para reconfigurarlo y aspirar incluso a plantearse nuevos objetos de estudio. Los resultados de esta investigación exploratoria, que se acotan al espacio iberoamericano, ponen de manifiesto una buena predisposición de los académicos ante la e-investigación, cuestión que parece ser un hecho extendido en todas las ciencias sociales. Al menos en el estudio de Dutton y Meyer (2008), los investigadores sociales del Reino Unido muestran una actitud positiva y más de la mitad de ellos (58,7%) que aseguran que muchas de las nuevas preguntas de investigación requerirán de nuevas herramientas, punto en el que coinciden los académicos de la región iberoamericana. Lo anterior hace evidente, por un lado, que la investigación de la comunicación sigue siendo un campo muy dependiente de la investigación general en ciencias sociales, tal como lo han afirmado Jensen y Jakowsky (1993) al referirse a las metodologías cualitativas, y, por otro lado, que al igual que en otras disciplinas sociales, los estudios en comunicación son un campo muy fértil para la implementación de las tecnologías digitales avanzadas.

Esta última idea se une al hecho de que los investigadores de comunicación en Iberoamérica son altamente conscientes: 1) De la necesidad de financiamiento propio para proyectos de e-investigación; 2) De los retos éticos que implican el uso de e-herramientas y las dinámicas de colaboración distribuida. Con estas preocupaciones, era de esperarse que los investigadores reclamaran mayor información y formación en el área. Actualmente, los países de la región no cuentan con organismos gubernamentales especializados en la promoción de la e-investigación y, en el caso de la comunicación, las asociaciones científicas especializadas (ALAIC, AE-IC, etc.) apenas están comenzando a formalizar acciones al respecto, lo que justifica el escaso desarrollo de la e-investigación en nuestra disciplina. Aunque no orientados a los estudios en comunicación, hay, sin embargo, organismos regionales, como la Cooperación Latinoamericana de Redes Avanzadas (RedClara), que se han percatado no solo de la importancia de la llamada e-Infraestructura, sino de la dinamización de las prácticas científicas de algunas comunidades a través de las redes avanzadas.

En ese sentido, a falta de políticas públicas y apoyo de los Estados para el fomento, la inversión y la inclusión del área de la comunicación en el desarrollo de la e-investigación, es importante que las universidades comiencen a establecer vínculos entre sus pares, con las empresas y la industria para buscar estrategias que contribuyan a mejorar la formación, el intercambio, la participación y colaboración distribuida geográficamente a través de redes de tecnologías avanzadas. Asimismo, si seguimos el planteamiento de Stewart (2007), estas políticas deben procurar focalizarse en los grupos y especialmente en los expertos locales, quienes finalmente promocionarán con mayor efectividad el uso avanzando de las TIC en la investigación.

Por otro lado, en línea con el trabajo de Codina (2009) los resultados de esta encuesta pueden servir para elaborar una guía de cuáles son los recursos y herramientas de la e-investigación que los académicos de la región están actualmente usando. Esto en aras de fortalecer dichas herramientas, pero también para potenciar aquellas, como el Grid o los simuladores, que tienen poca aceptación dentro de la comunidad. Nos sirve para contrastar estas prácticas con las de otras comunidades de la misma región, en especial con la comunidad de físicos de altas energías de América Latina, en la que hemos detectado la utilización más intensiva de herramientas electrónicas de colaboración científica. Un estudio precedente (Briceño, Arcila & Said, 2012) confirma la tendencia de esta comunidad al uso de herramientas de publicación electrónica académica y de manejo compartido de datos, pero encuentra bajo interés en la implementación de herramientas comerciales, masivas y populares, cuestión que marca mucha diferencia con los investigadores en comunicación, quienes, por ejemplo, manifestaron un alto uso (más de 60%) de redes sociales como Facebook o Twitter y de sitios para compartir archivos como Youtube, Slideshare, Dropbox y Flickr.

Aunque no hallamos relación entre la edad y el nivel educativo con el uso intensivo del computador para la investigación –a diferencia del estudio de Procter y otros (2010), en investigadores del Reino Unido, donde se encontraron asociaciones significativas entre la adopción de la Web 2.0 y la edad, el sexo y la posición académica–, podríamos afirmar que existen dificultades –algunas de tipo tecnológico– que provocan que los investigadores de la comunicación de Iberoamérica prefieran las herramientas comerciales antes que las avanzadas, como sucede en el caso de las videoconferencias, en que la diferencia de uso es de casi 30% en favor de sistemas como Skype. Este último punto, sin embargo, sí es consistente con los resultados de Procter y colaboradores (2010) en el que una parte significativa de los investigadores estudiados prefirieron el uso de herramientas «genéricas» que de herramientas «específicas».

En nuestro caso, las limitaciones no solo son de tipo tecnológico sino de conocimiento de ciertas plataformas, como en el caso de los sistemas pre-print, en la que menos del 7% de los investigadores respondieron haberlas usado, a diferencia de los físicos de altas energías que usaron espacios como arXiv (48,39%) o SPIRES (41,94%), sitios que no requieren mayores conocimientos tecnológicos. Adicionalmente, si bien al menos la mitad de los investigadores manifestaron usar los repositorios de acceso abierto, es evidente que la existencia de un repositorio especializado en comunicación estimularía el uso de los mismos.

Los apartados anteriores sugieren que existe una buena predisposición hacía la e-investigación en comunicación, pero que hay factores que dificultan su implementación, sobre todo si tomamos en cuenta que la llamada e-Ciencia no se refiere solo al uso de tecnologías digitales comerciales, sino, sobre todo, a la incorporación de herramientas de computo avanzado para el manejo de grandes cantidades de datos y para la intensificación de la colaboración científica, unido a las actitudes y hábitos de los investigadores en las prácticas y dinámicas de trabajo como la conformación de equipos multidisciplinarios, revisión entre pares y la publicación colectiva, entre otros. Siguiendo la curva de Rogers (2003), además de los innovadores ya nos encontramos con los primeros seguidores en el uso de los nuevos medios para la investigación y la generación de nuevas prácticas. En este sentido, es fundamental la creación de organismos especializados en la región y el establecimiento de políticas (financiamiento, formación, etc.), dirigidas a fortalecer la actividad de investigación a partir del uso de plataformas como Internet2 o las Grids. Asimismo, se hace necesario (tal como los propios investigadores lo han reconocido) que los estímulos se dirijan a la creación de proyectos colaborativos y distribuidos geográficamente (mucho menos de la mitad de nuestros encuestados respondieron haber presentado un proyecto de investigación con pares de otras instituciones), con lo que se puede fortalecer la creación de comunidades virtuales de investigación y de colaboratorios.

Agradecimientos

Los autores de este estudio quieren agradecer a los revisores anónimos, quienes con sus comentarios contribuyeron a mejorar la calidad del estudio. Asimismo, agradecen al Observatorio de Medios y Opinión Pública y a la Dirección de Investigación, Desarrollo e Innovación de la Universidad del Norte (Colombia) por el apoyo concedido.

Notas

1 En este estudio participaron también Ignacio Aguaded (España), Cosette Castro (Brasil), Marta Barrios (Colombia), Martín Díaz (Colombia) y Elías Suárez (Colombia)

2 Se pueden consultar los 22 Grupos de Trabajo de ALAIC en www.alaic.net.

Referencias

Arcila, C. (2011). La difusión digital de la investigación y las resistencias del mundo científico. In E. Said (Ed.), Migración, desarrollo humano, internacionalización y digitalización. Retos del siglo XXI. (pp. 325-334). Barranquilla: UniNorte.

Arroyave, M., Velásquez, A., & al. (2011). Laboratorios remotos: diversos escenarios de trabajo. Disertaciones, Anuario Electrónico de Estudios en Comunicación Social, 4, 2, 83-94.

Atkins, D.E., Droegemeir, K.K., & al. (2003). Revolutionizing Science and Engineering through Cyberinfrastructure: Report of the National Science Foundation Blue-Ribbon Advisory Panel on Cyberinfrastructure. Washington, DC: National Science Foundation.

Bernius, S. (2010). The Impact of Open Access on the Management of Scientific Knowledge. Online Information Review, 34, 4, 583-603. (DOI: 10.1108/14684521011072990).

Borgman, C. (2007). Scholarship in the Digital Age. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Briceño, Y., Arcila, C. & Said, E. (2012). Colaboración y comunicación científica en la comunidad latinoamericana de físicos de altas energías. E-Colabora, 2, 4, 131-144.

Codina, L. (2009). Ciencia 2.0: Redes sociales y aplicaciones en línea para académicos. Hipertext.net, 7.

Cuadros, A., Martínez, A. & Torres, F. (2009). Determinantes de éxito en la participación de los grupos de investigación latinoamericanos en programas de cooperación científica internacional. Interciencia, 33, 11, 821-828.

Cuel, R., Ponte, D. & Rossi, A. (2009). Towards an Open/Web 2.0 Scientific Publishing Industry? Preliminary Findings and Open Issues. Informe Técnico de la University de Trento. (http://wiki.liquidpub.org/mediawiki/upload/b/b3/CuelPonteRossi09.pdf) (05/10/2012).

De Filippo, D., Morillo, F. & Fernández, M.T. (2008). Indicadores de colaboración científica del CSIC con Latinoamérica en bases de datos internacionales. Revista Española de Documentación Científica, 31, 1, 66-84.

Dutton, W. & Jeffreys, P. (Eds.) (2010). World Wide Research. Reshaping the Sciences and Humanities. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Dutton, W.H. & Meyer, E.T. (2008). e-Social Science as an Experience Technology: Distance From, and Attitudes Toward, e-Research. 4th International Conference on e-Social Science. Manchester (UK), 18-06-2008. (www.ncess.ac.uk/events/conference/programme/thurs/1bMeyerb.pdf) (01/10/2011).

Gentil-Beccot, A., Mele, S. & al. (2009). Information Resources in High-Energy Physics: Surveying the Present Landscape and Charting the Future Course. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60, 1, 150-160

Hey, T., Tansley, S. & Tolle, K. (Eds.) (2009). The Fourth Paradigm. Data-Intensive Scienti?c Discovery. Redmond Washington: Microsoft Research.

Jankowski, N. & Caldas, A. (2004). e-Science: Principles, Projects and Possibilities for Communication and Internet Studies. Etmaal van Communicatiewetenschap Day of Communication Science. Holland: Universidad de Twente.

Jensen, K.B. & Jankowski, N.W. (1993). Metodologías cualitativas de investigación en comunicación de masas. Barcelona: Bosch.

Liao, C. (2010). How to Improve Research Quality? Examining the Impacts of Collaboration Intensity and Member Diversity in Collaboration Networks. Scientometrics, 86, 747-761.

Nentwich, M. (2003). Cyberscience: Research in the Age of the Internet. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences.

Neylon, C. & Wu, S. (2009). Open Science: Tools, Approaches, and Implications. XIV Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing. Hawaii (USA), 09-01-2009. (http://psb.stanford.edu/psb-online/proceedings/psb09/workshop-opensci.pdf) (05/10/2012).

Perrott, R., Harmer, T. & Levis, R. (2008). e-Science Infrastructure for Digital Media Broadcasting. Computer, November, 67-72.

Ponte, D. & Simon, J. (2011). Scholarly Communication 2.0: Exploring Researchers’ Opinions on Web 2.0 for Scientific Knowledge Creation, Evaluation and Dissemination. Serials Review, 37, 3, 149-156.

Procter, R., Williams, R. & al. (2010). Adoption and Use of Web 2.0 in Scholarly Communications. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A-Mathematical Physical, 368, 4.029-4.056.

Rogers, E.M. (2003). Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press.

Stewart, J. (2007). Local Experts in the Domestication of Information and Communication Technologies, Information. Communication & Society, 10, 4, 547-569

Waldrop, M. (2008). Science 2.0. Is Open Access Science the Future? Is Posting Raw Results Online, for all to See, a Great Tool or a Great Risk? Scientific American Magazine, 21 de abril. (www.sciamdigital.com/index.cfm?fa=products.viewissuepreview&articleid_char=3e5a5fd7-3048-8a5e-106a58838caf9bf7) (01-11-2009).

Document information

Published on 28/02/13

Accepted on 28/02/13

Submitted on 28/02/13

Volume 21, Issue 1, 2013

DOI: 10.3916/C40-2013-03-01

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?