Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

This study focuses on the relationship between preadolescents and youtubers, with the objective of observing how tweens integrate youtubers as referents of a teen digital culture. From a socio-psychological and communicological perspective, a mixed methodological design was applied to carry out the audience study, which was divided into two parts: a quantitative analysis of the audience via a survey administered to 1,406 eleven-twelve year old students of Catalan Secondary Schools, and a qualitative analysis of the preadolescence audience using three focus groups. The quantitative data was analysed with SPSS and the qualitative data with the help of the Atlas.ti software. The results demonstrate that tweens consider youtubers as referents for entertainment and for closeness to a teen digital culture, but not really as a role models or bearers of values as influencers. Also, preadolescents show some dimensions of Media Literacy, since they recognise youtubers’ commercial strategies and their role as actors and professionals. The study notes gender bias in some aspects, and is an introduction to observation of the social functions of youtubers amongst teenagers, individuals who are in the process of constructing their identity and on the point of becoming young adults.

1. Introduction and state of art

Today’s adolescents and young adults, so-called millennials (Strauss & Howe, 2000), were born and have grown up in an environment permeated by media, and so their “natural” ecosystem can be described as the 2.0 social media environment. A number of studies have highlighted the role of media in the socialisation of children and young people, although until only a few years ago this meant the so-called traditional mass media (Arnett & al., 1995). In today’s media ecosystem (Jenkins, 2006), colonised by countless devices, screens, social networks and apps, young people have an increasing number of options from which to choose and they have access to them at an increasingly young age.

The complex relationship between media and young people during the last century started out life with the identification of young people as belonging to a certain market niche. This led to the establishment, or rather, the recognition of a key stage in human development. Teens, young people between 13 and 19 years of age, were originally targeted in the 1950s by cinema, radio and television (Davis & Dickinson, 2004; Ross & Stein, 2008). Tweens or preadolescents, young people between 9 and 13 years old, were then identified as a market segment in the 1980s (Ekström & Tufte, 2007).Tweens, young consumers, are neither children nor adults (Linn, 2005); they are “between human being and becoming”, as pointed out by Larocca & Fedele (2017).

Psychology and sociology have taught us that adolescence is a key stage of life and development in which adolescents are in the process of constructing their idea of themselves, as they make choices related to fundamental issues (academic, gender, etc.), which will influence their future life. Hence, they are more susceptible to the influence of the environment (Bernete, 2009), and it becomes essential to understand how adolescents interact with the digital environment (Blomfield & Barber, 2014).

We also know that the interaction of children with YouTube involves a series of characteristics, such as collaboration with peers and family, interaction with viewers, learning opportunities, civic engagement and identity formation (Lange, 2014; Lenhart & al., 2015), but there is still a need for research into the way in which so-called influencers may serve as guides in the processes of socialisation and identity construction of tweens.

Also, as summarized by Fedele (2011), we know that audiences can attribute to media four main kinds of social functions: entertainment (e.g. fun, humour, spending time, avoidingboredom, escaping routine), consumption situation (e.g. ritual, structural and relational use), narrative (e.g.: bardic and storytelling functions), and socialisation functions (e.g. personal identity and community building, learning about reality, society modelling, sharing and commenting, identification and admiration, parasocial relationships). As for social functions, social networks as Instagram, Facebook and YouTube have become a relevant area of social interrelation for adolescents in the context of their identity building process (Ahn, 2011). As for YouTube, according to Pérez-Torres & al. (2018: 63), young users show a mostly passive use, a characteristic that may largely favour the role of youtubers as model references in the construction of youth identity.

From these theoretical standpoints, the overall aim of the study is to observe how tweens integrate youtubers as referents of a teen digital culture, that is to say, to discover what preadolescents are attracted to regarding youtubers, which of the mentioned social functions they attribute to youtubers, and how they integrate the models and values proposed by youtubers, in their capacity as influencers.

This study combines a set of different theoretical perspectives: a constructivist approach, the tradition of cultural studies, the theory of uses and gratifications, and a gender perspective, since previous studies pointed out that girls and boys use social media in a different way (Oberst, Chamarro, & Renau, 2016).

1.1. The emergence of youtubers as an “authentic performance” for the young

Youtuber boom really took off in 2012, with the change of the YouTube interface, and by 2016 YouTube had become the second largest social network in the world after Facebook and the first in digital content (Bonaga & Turiel, 2016: 128). As these authors point out, the platform combines the sought-after sensation of intimacy between youtubers and users with the ability to position videos on search engines (YouTube uses Big Data analysis). In addition to the economic benefits and the huge global market represented by the platform, youtubers can become commercial brands and role models at the same time (Lovelock, 2017), especially amongst the very young. The ability to improvise, to change, and to surprise is a world away from the scripted and hermetic programming of traditional media and this makes youtubers very attractive to adolescents. According to Montes-Vozmediano, García-Jiménez & Menor-Sendra (2018: 68), “videos by adolescents are watched twice as much, and those by youtubers are those with the greatest impact”.

The idea of youtubers as Web 2.0 micro-celebrities is connected to Senft’s definition (2012), which refers to joining together “the double aspect of ‘authentic’ performance of self on social media as a ‘brand identity’” with “wisely managed ‘authenticity’ for commercial gain”. As Smith (2017: 3) states, “microcelebrity is fraught with difficulties around authenticity vs. self-interested promotion (Senft, 2012) and negotiating intimacy with commercial interest (Abidin, 2015)”. On the one hand a Celebrity Studies research line analyses youtubers and vloggers beyond commercial interests, framing 2.0 celebrities in “a state of ‘selfhood’ which allows each person equal space to consummate a unique vision of themselves” (Smith, 2016: 1). On the other, several studies point out celebrities’ symbolic markers of “authenticity” as representations of the working class (Biressi & Nunn, 2005; Oliva, 2014).

Successful youtuber microcelebrities, whom Bonaga and Turiel (2016: 120) define as “creators”, become influencers: “As the name indicates, influencers are those who use their ability to communicate to influence the behaviour and opinions of third parties”. Jerslev (2016: 5233) also asserts that “microcelebrity strategies are especially connected with the display of accessibility, presence, and intimacy online”.

Youtubers, then, are an integral part of a teen culture as influencers and protagonists who help –directly or indirectly– to initiate the adolescents into multimedia products specifically aimed at them. The fact that many successful youtubers are young people themselves makes it all the more valuable to analyse their relationship with adolescent internet users (Westenberg, 2016), since they may be role models through both identification and admiration mechanisms (i.e.: socialisation function).

To work as a role model (Calhoun, 2010) a person’s behavior or their success can be emulated by others, especially by younger people. This notion is related to the aspirational models (real or fictional), which must be sufficiently removed to constitute an object of desire, but not so far as to be perceived as inaccessible or in such a way that all possibility of contact is lost (Massonnier, 2008: 47).

The identity building function, the manner in which characters are identified and empathised with, and even the parasocial relationships engaged in by media audiences have been documented over decades (e.g. Hoffner & Buchanan, 2005; Iguartua-Perosanz & Muñiz-Muriel, 2008; Livingstone, 1988). Many youtuber followers for example, especially those who have been followers for some time, expect certain familiar aspects which connect them to their youtuber, such as greetings, nicknames or “certain linguistic devices (e.g. overstressed or long vowels) (Dredge, 2016a) for comic or ludic effect, thereby inviting playful commentary and injecting gaiety into the community” (Cocker & Cronin, 2017: 8), and followers will protest when they do not appear on a regular basis.

Despite the differences in format between television and the internet, and the opportunities to interact, and despite adolescents’ perception that they have greater freedom when interacting with the internet (Aranda, Roca, & Sánchez-Navarro, 2013), there are psychological mechanisms which are activated similarly by followers of television fiction and those on social media. For this reason, as it will be explained below, categories which are normally used for fictional characters will be employed in this study to analyse what tweens like of youtubers, given that so-called “influencers” are representations of real people.

2. Material and methodology

A mixed method approach (Creswell & Plano-Clark, 2007) was employed in this audience study, specifically a sequential explanatory design (Creswell, 2014), which was divided into two phases: (1) Quantitative analysis of the audience via survey; (2) Qualitative analysis of the audience with focus groups. The protection of human subjects was guaranteed in the study, in accordance with protocols that were approved by the financing institution and the Research Ethics Committee at the Ramon Llull University.

2.1. Description of youtuber profiles

10 of the 20 most highly followed Spanish-language youtubers were selected (Socialblade, 2016) in order to ensure balance in terms of gender and variety in terms of YouTube channels thematic categories (videogames, music, memes/jokes, beauty/fashion, etc.). These were, in decreasing order of subscribers: ElrubiusOMG, Vegetta777, Willyrex, ZacortGame, ElrincondeGiorgio, Wismichu, Staxx, Auronplay, ExpCaseros and YellowMellowMG.

The prominence of channels related to videogames should be pointed out (in line with the findings of Gómez-Pereda, 2014) as well as channels linked to entertainment and, in the case of ExpCaseros, self-learning experiments. All 10 can be considered influencers as they have more than a million subscribers (Berzosa, 2017), they present themselves as creators, generally using a language based on humour and proximity, they also generally have a presence on other channels and media, as well as being the focus of a true transmedia strategy.

2.2. Analytical instruments2.2.1. The questionnaire

Following a pilot survey (n=85) to test and validate the methodological tool in three secondary schools in Barcelona, Catalonia, a questionnaire was developed to discover what preadolescents look for in the world of youtubers and if they project themselves in any way.

A Google form entitled “Young people’s preferences” was designed for the definitive survey and was administered online in the classroom in the presence of teachers. The schools were contacted via email and the teachers were instructed on how to administer the questionnaire and told specifically not to mention the word “YouTube” explicitly.

The questionnaire, written in both official languages of Catalonia (Catalan and Spanish), had two parts:

• Five questions regarding sociodemographic data (age, gender, school, etc. with a strict respect for maintaining anonymity),

• Eight questions on the subject matter of the study: one open question and the rest with closed answers (some multiple choice and others on a 5 point Likert scale).

Among other questions, respondents were asked the reasons why they were interested in the 10 youtubers of the list. The characteristics they had to evaluate were based on a typology used in analysis of fictional characters: identification with a character, admiration towards a character, coolness, characters’ closeness to own interests, entertainment and socialisation functions, such as sharing with a peer group (Buckingham, 1987; Fedele, 2011; García-Muñoz & Fedele, 2011; Iguartua-Perosanz & Muñiz-Muriel, 2008; Medrano & al., 2010).

The survey was undertaken during the month of December, 2016 by pupils in the first year of ESO (Compulsory Secondary Education, 11-12 years of age) in 41 public and private secondary schools in Catalonia, yielding a total of 1406 valid responses, 716 girls (50.9%) and 690 boys (49.1%). As for age, 87.1% (n=1,224) of the participants were 12 years old, with an average age of x=12.11 (Median=12, Mode=12).

SPSS software was used to carry out the descriptive analysis and provided frequency tables and descriptive statistics (mean, mode, median, and standard deviation) and bivariant analysis using the Chi square, Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests, depending on the type of variable (level of significance p<0,05).

2.2.2. Focus group interview script

The objective of the focus groups was to delve into preadolescents’ feelings about, and interest in, youtubers. Moderators followed an interview script using semi-structured questions, which were grouped into 21 categories based on the variables of the quantitative phase, amongst which, for the purposes of this article, the following stand out:

• Youtubers’ functions, e.g. identification, admiration, coolness, closeness, entertainment, peer-related functions.

• Media literacy, e.g. media production and dissemination processes (Ferrés & Piscitelli, 2012); the role of youtubers as actors and professionals.

The three focus groups, each of six participants (three boys and three girls), were carried out between January and March 2017. The participants from the focus groups were selected according to the following criteria: the school and the pupils’ availability, being talkative, and having different levels of interest in the subject “Information technology”. The focus groups were recorded and transcribed verbatim and analysed following the procedure of Thematic Analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Four different researchers in pairs and an official trainer of Atlas.ti, who discussed how to categorize reponses until reaching a final consensus, carried out the coding process. The qualitative analysis was carried out with the help of Atlas.ti software.

The results of the Focus Group contributions were identified in the following way: Focus group number (FG1, FG2, FG3) + Participant (Boy/Girl) + Participant Number (in contribution order).

3. Analysis and results

3.1. Tweens’ preferences related to youtubers

The youtubers from the list most recognised by tweens in the survey sample were AuronPlay (78.2%, n=1,120), ElrubiusOMG (74.1%, n=1,042), and Wismichu (66.4%, n=933). Moreover, participants could indicate other youtubers that they liked, and this was done by 55.3% (n=777), with 271 different youtubers mentioned, a fact that demonstrates a wide diversity amongst what tweens watch on YouTube. The other youtubers mentioned included DjMaRiio (2.7%, n=38) and two women, Dulceida (2,6%, n=36) and Yuya (1,2%, n=17).

3.2. Social functions attributed to youtubers

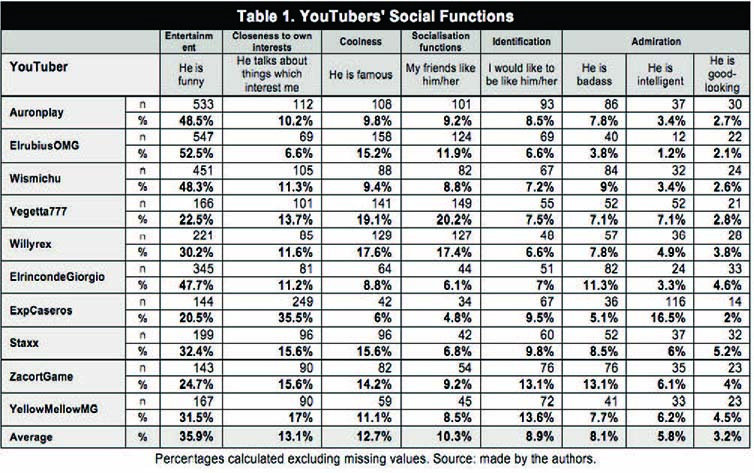

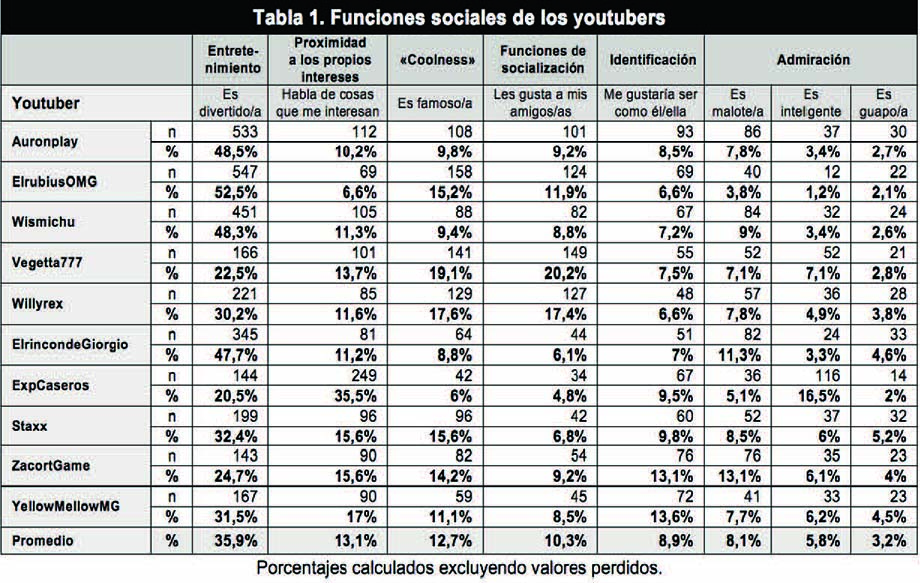

The social functions attributed by participants, varied a great deal by youtuber, as shown in Table 1, with the entertainment function being the most valued one. In particular, concerning the second most valued function, closeness to their own interests, it has to be stressed that it is most valued in the case of ExpCaseros (35.5%, n=249), the only youtuber focused on self-learning experiments. On the other hand, both coolness and socialisation functions were attributed to youtubers by more than 10% of tweens in the sample. Finally, items related to identification and admiration were valued by fewer respondents.

There are significant gender differences in the ratings of most of the proposed youtubers, which was more noticeable in the case of male youtubers (Auronplay: p<0.001; ElRubiusOMG: p<0.001; Vegetta777: p<0.001; Willyrex: p=0.001; Zacortgame: p<0.001) compared to the one female youtuber on the list, YellowMellowMG (p=0.022). In particular, boys tend to place more value on the identification function (even in the case of YellowMellow), while girls tend to place more value value on socialisation functions. Also, especially in the case of gamers’ channels, boys place more value on closeness to their interests, while girls place more value on the entertainment function. Finally, as for admiration functions, boys place more value on the attributes “intelligent” and “badass” (also in the case of YellowMellowMG), while girls place more value on a male youtuber being “good-looking”.

In terms of identification, it is noteworthy that 9 out of 10 of the proposed youtubers were male, which is more than probably the reason why girls did not choose this characteristic.

Once more, the case ExpCaseros is worth noticing, since no gender differences were found for this self-learning experiments Youtuber, so that both girls and boys like him for the same reasons, including the closeness to their interests.

There are differences in the open option (p=0.001), above all in relation to Dulceida, who was only mentioned by girls (5%, n=36) and in relation to DjMaRiio, who was only mentioned by boys (5.5%, n=38).

The number of mentions to youtubers made in the qualitative results do coincide with the three first youtubers on the quantitative list, AuronPlay, ElRubiusOMG and Wismichu, but there are also many other comments on other youtubers, such as Dulceida and Yuya.

The characteristics mostly mentioned by participants are knowledge (admiration function) and humour (entertainment function), particularly in the case of Hamza Zaidi (though not included in the list), even if there was also evidence of the importance given to identification and closeness with some youtubers, as can be seen in the following fragment from FG3:

– FG3-Boy1: Hamza. Hamza Zaidi. He’s from Morocco, but he’s Spanish and speaks Spanish and everything and he’s very funny.

– Moderator: And do you imitate him? Or what’s funny about him?

– FG3-Girl2: No, it’s that sometimes he uses expressions which we say ... [...] we don’t laugh at him.

– Moderator: So you don’t laugh at him, then, but he is funny.

– FG3-Boy1: No, he does it on purpose. For example, instead of saying “bed”, he says “beeeeed”.

– Moderator: And you say that when you are out in the playground and things?

– FG3-Boy1: Yes.

3.3. Media literacy dimensions

Both in the open questions of the survey and in the qualitative phase, several comments denote a sort of media literacy in the participants, since they are able to recognise both media production and dissemination processes, and what being a youtuber means.

First, in the survey the respondents were asked in an open question what they do not like about YouTube. Some of them indicate, in the open option, items that can be categorised as YouTube commercial mechanisms (3.5%, n=49) –as the bell, the clickbait, and overall the ads–, the lack of netiquette and rude behaviours of particular youtubers (5%, n=70), and the risks for minors (0.4%, n=6), as in the case of the protection of their identity and privacy. Also, in the qualitative phase, preadolescents have either an explicit (FG3Boy2: “Google pays for monetization on YouTube”; FG3Boy1: “And if you put ads [on your channel] you get paid more”) or implicit understanding of the dynamics and commercial demands of youtubers.

This implicit understanding is connected to the reasons for liking and disliking youtubers, since participants –in particular girls– are critical of offensive comments or behaviour. For instance, the two youtubers at the top of the ranking, AuronPlay and Wismichu, favourably rated as “badass”, are also unpopular with some participants in the focus groups, while one of those most commented upon youtuber and most highly rated for authenticity, knowledge and respect for her followers is Yuya:

– FG3-Girl1: (I don’t like) big-heads. That’s why I like Yuya, because she has a lot of followers but she hasn’t changed (...) and she respects her followers more than others.

– FG3-Boy4: She’s very calm, she is. (...)

– Moderator: It’s the real her? She is not fake?

– FG3-Girl1: No, she’s like that.

Second, almost all the boys and girls in the focus groups recognised that there was a difference between the character on YouTube –with its pros (fame and money) and cons (loss of intimacy and anonymity, risks associated with fame)–, and the real person:

– FG1-Boy3: And a lot of youtubers also say that they often act out a character on YouTube, but that afterwards they are very different.

– Moderator: They say that?

– (Some): Yes. [...]

– FG3-Boy3: For example Wismichu said in a video that he was really funny in videos but he was more serious in real life.

– FG3-Boy2: I also saw a video with youtubers... and when you see them in that video they are really nice and friendly, but when they do their own videos they turn really badass. They say things like: “I don’t like that”, or “Get out of here!”.

On the other hand, participants recognise the role of youtubers as professionals and workers. In the survey, 4.5% (n=63) of respondents said they would like to be a youtuber when they grow up, an option indicated more by boys (7.2%, n=50) than by girls (1.8%, n=13) (p<.0.001), while 9 participants (0.6%), 2 girls and 7 boys, indicated that they already had their own YouTube channel. In the focus groups, participants also pointed out that being a youtuber could be a profitable and enjoyable profession, although it could also be very stressful and challenging.

4. Discussion and conclusions

The aim of the study was to delve into the risks and the opportunities associated with the relation between tweens and specific social media actors, the youtubers. The quantitative and qualitative results have allowed us to respond to the overall objective.

Related to tweens’ preferences and youtubers’ functions in tweens’ life, on the one hand, it can be stated that preadolescents are more attracted to entertainment and the feeling of being part of a digital teen culture, which they can share with their peer group. On the other hand, even if they recognise some kind of attraction of fame amongst the models embodied by youtubers, they distrust the short-term nature and the risks related to this job; they are also wary of certain attitudes and codes youtubers express which may be offensive.

With regard to the possible ability of youtubers to foster models as influencers, we have observed that the characteristics valued depend a lot on the particular youtuber. At the time this study was completed, the youtubers best-known by preadolescents were AuronPlay, ElrubiusOMG and Wismichu, who were also regarded as the funniest. But when participants were asked to mention spontaneously who they liked and why, there were many more, including women such as Dulceida and Yuya, thus representing better gender and ethnic background, as well as channel subject variety.

Preadolescents value the humour of youtubers above all else, and in a very distant second place, the proximity of youtubers to young people’s interests, that is the entertainment and socialisation functions aimed at sharing the content with their peers. It is significant that Yuya is the youtuber who received the most favourable comments and this was because of her knowledge, her good relationship with her followers and her authenticity.

Aspects such as coolness, sharing with peers, or identification are more highly rated than others such as looks, or intelligence as factors of attraction.

The participants in our study are well acquainted with youtubers as public figures and micro-celebrities, but they admire their comic nature and their knowledge more than their look or the brand images, which they may represent. They are still present as reference for entertainment and sociability, whilst not being of chief importance and without creating a desire in participants to become a reflection of the so-called influencers.

So we could say that youtubers are incorporated into tweens’ leisure time practices and that are seen more as actors of a teen digital culture, rather than as identification or admiration models as influencers, mostly given the critical attitude preadolescents have of them. When preadolescents are asked what they want to be when they are older, being a youtuber is seen more as a hobby than a profession. Hence, it can be observed that YouTube still has a limited impact on young people at this stage of their identity development.

This does not diminish the fact that preadolescents know and imitate youtubers’ language and expressions, or follow those they like, and even enjoy some of the “badass” youtubers, nor does it mean that that they do not recognise the risks of the loss of intimacy and the abuses which are present and may become amplified by the digital environment. The comments of our participants show they know what it is to be media literate in production and dissemination processes and, lesser, in ideology and values dimensions (Ferrés & Piscitelli, 2012): They comment on commercial strategies, they are comfortable using information terms such as monetization, and they are very critical of offensive and discriminatory attitudes.

Lastly, gender bias is clearly evident not only in the lower number of female youtubers and the social functions attributed to youtubers, but also in the fact that there are three times more boys than girls who have had a YouTube channel and there are four times more boys interested in a future as youtubers.

There is a need for more research into the role of exclusion and the function of refuge which social media might exercise over the youngest boys and girls, as noted by Michikyan and Suárez-Orozco (2016: 413): “Conscientiousness maintained a consistently protective role over time while hostile classroom contexts increased vulnerability over time, particularly for girls”. There is also room for further research to look into differences according to age group and to analyse whether social media foster the development of the new generations’ individual and differentiated characteristics –in the sense of creating a mirage of social diversity and identity on the platforms, as in Jenkins (2006)– and if they do so both as consumers and prosumers. We agree with Pérez-Torres & al. (2018), when they point out that it is recommendable to increase the sample of youtubers, using selection criteria not based on the number of followers, and extend the analysis to blogs and Instagram.

Fully incorporated in the digital ecosystem as they are, it seems that preadolescents are on the point of making the leap into full adolescence. Once there, they may find themselves lacking referents. In this sense, we would argue that educommunication in schools and the idea of the prosumer should be made more of. YouTube and youtubers should not only be used as a form of animated information or as a way of identifying those guilty of performing in today’s “market of the ego” (Rivière, 2009); youtubers contribute to the range of opportunities and servitudes of the neoliberal system we belong to, which includes gender stereotypes.

Funding agency

This study is part of the activities of the Tractor Projects (2017) supported by the University Ramon Llull in Barcelona and “La Caixa” Foundation (Spain) and funded by CAC, Audiovisual Council of Catalonia (Researcher grants 49/2016).

References

Ahn, J. (2011). The effect of social network sites on adolescents´ social and academic development: current theories and controversies. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(8), 1435-1445. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21540

Aranda, D., Roca, M., & Sánchez-Navarro, J. (2013). Televisión e Internet. El significado de uso de la red en el consumo audiovisual de los adolescentes. Quaderns del CAC, 39(XVI), 15-23. https://bit.ly/2si7mTQ

Arnett, J.J., Larson, R., & Offer, D. (1995). Beyond effects: adolescents as active media users. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 24, 511-518. https://bit.ly/2KWwebl

Bernete, F. (2009). Usos de las TIC, relaciones sociales y cambios en la socialización de los jóvenes. Revista de estudios de juventud, 88, 97-114. https://bit.ly/2kwxkzo

Berzosa, M. (2017). Youtubers y otras especies. Barcelona: Ariel-Fundación Telefónica.

Biressi, A., & Nunn, H. (2005). Reality TV. Realism and revelation. London: Wallflower Press.

Blomfield, C.J., & Barber, B.L. (2014). Social networking site use: Linked to adolescents’ social self-concept, self-esteem, and depressed mood. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66, 56-64. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12034

Bonaga, C., & Turiel, H. (2016). Mamá, ¡quiero ser youtuber!. Barcelona: Planeta.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Buckingham, D. (1987). Public secrets: Eastenders and its audience. London: BFI.

Calhoun, C.J. (Ed.) (2010). Robert K. Merton: Sociology of science and sociology as science. New York: Columbia UP.

Cocker, H., & Cronin, J. (2017). Charismatic authority and the youtuber. Unpacking the new cults of personality. Marketing Theory, 17(4), 455-472. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593117692022

Creswell, J.W. (2014). Research design. Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (4th. ed.). Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J.W., & Plano-Clark, V.L. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Davis, G., & Dickinson, K. (Eds.) (2004). Teen TV: Genre, consumption, identity. London: BFI.

Ekström, K.M., & Tufte, B. (Eds.) (2007). Children, media and consumption. On the front edge. Göteborg: Göteborg University.

Fedele, M. (2011). El consum adolescent de la ficció seriada televisiva. Barcelona: UAB, Tesis Doctoral. https://goo.gl/mswUJC

Ferrés, J., & Piscitelli, A. (2012). Media competence. Articulated proposal of dimensions and indicators. [La competencia mediática: Propuesta articulada de dimensiones e indicadores]. Comunicar, 38(XIX), 75-82. https://doi.org/10.3916/C38-2012-02-08

García-Muñoz, N., & Fedele, M. (2011). Television fiction series targeted at young audience: Plots and conflicts portrayed in a teen series. [Las series televisivas juveniles: tramas y conflictos en una «teen series»]. Comunicar, 37, 133-140. https://doi.org/10.3916/C37-2011-03-05

Gómez-Pereda, N. (2014). Youtubers. Fenómeno de la comunicación y vehículo de transmisión cultural para la construcción de identidad adolescente. Universidad de Cantabria. https://bit.ly/2L0Amaa

Hoffner, C., & Buchanan, M. (2005). Young adults’ wishful identification with television characters: The role of perceived similarity and character attributes. Media Psychology, 7, 325-351. https://bit.ly/2sdcuta

Igartúa, J.J., & Rodriguez-de-Dios, I. (2016). Correlatos motivacionales del uso y la satisfacción con Facebook en jóvenes españoles. Cuadernos.info, 38, 107-119. https://doi:10.7764/cdi.38.848

Igartúa-Perosanz, J.J., & Muñiz-Muriel, C. (2008). Identification with the characters and enjoyment with features films. An empirical research. Communication & Society 21(1), 25-52. https://bit.ly/2LAkgVP

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture. New York: New York University Press.

Jerslev, A. (2016). In the time of the microcelebrity: Celebrification and the youtuber Zoella. International Journal of Communication, 10, 5233-5251. https://bit.ly/2shZq4T

Larocca, G., & Fedele, M. (2017). Television clothing commercials for tweens in transition: A comparative analysis in Italy and Spain. In E. Mora & M. Pedroni (Eds.), Fashion tales: Feeding the imaginary (pp. 407- 424). Peter Lang.

Lenhart, A., Smith, A., Anderson, M., Duggan, M., & Perrin, A. (2015). Teens, technology and friendships. Pew Research Center. https://bit.ly/2L0Hxzd

Linn, A. (2005). Consuming kids: The hostile takeover of childhood. New York: First Anchor Books.

Livingstone, S. (1988). Why people watch soap opera: An analysis of the explanations of British viewers. European Journal of Communication, 3, 55-80. https://doi:10.1177/0267323188003001004

Lovelock, M. (2017). ‘Is every youtuber going to make a coming out video eventually?’: YouTube celebrity video bloggers and lesbian and gay identity, Celebrity Studies, 8(1), 87-103. https://doi:10.1080/19392397.2016.1214608

Massonnier, V. (2008). Tendencias de mercado. Están pasando cosas. Buenos Aires: Granica.

Medrano-Samaniego, C., Cortés, P.A., Aierbe, A., & Orejudo, S. (2010). TV programmes and characteristics of preferred characters in television viewing: A study of developmental and gender differences. Cultura y Educación, 22(1), 3-20. https://doi:10.5944/educXX1.13951

Michikyan, M., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2016). Adolescent media and social media use: implications for development. Journal of Adolescent Research, 31(4), 411-414. https://doi:10.1177/0743558416643801

Montes-Vozmediano, M., Garcia-Jiménez, A., & Menor-Sendra, J. (2018). Teen videos on YouTube: Features and digital vulnerabilities. [Los vídeos de los adolescentes en YouTube: Características y vulnerabilidades digitales]. Comunicar, 54(XXVI), 61-69. https://doi.org/10.3916/C54-2018-06

Oberst, U., Chamarro, A., & Renau, V. (2016). Gender stereotypes 2.0: Self-representations of adolescents on Facebook. [Estereotipos de género 2.0: Auto-representaciones de adolescentes en Facebook]. Comunicar, 48(XXIV), 81-90. https://doi.org/10.3916/C48-2016-08

Oliva, M. (2014). Celebrity, class and gender in Spain: an analysis of Belén Esteban's image. Celebrity Studies, 5(4), 438-454. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2014.920238

Pérez-Torres, V., Pastor-Ruiz, Y., & Abarrou-Ben-Boubaker, S. (2018). Youtuber videos and the construction of adolescent identity. [Los youtubers y la construcción de la identidad adolescente]. Comunicar, 55, 61-70. https://doi.org/10.3916/C55-2018-06

Rivière, M. (2009). La fama. Iconos de la religión mediática. Barcelona: Noema.

Ross, S.M., & Stein, L.E. (Eds.) (2008). Teen television: Essays on programming and fandom. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Senft, T.M. (2012). Microcelebrity and the branded self. In J. Hartley, J. Burgess, J., & A. Bruns (Eds.), A companion to new media dynamics (pp. 346-354). Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

Smith, D. (2017). The tragedy of self in digitised popular culture: The existential consequences of digital fame on YouTube. Qualitative research, Special issue: Qualitative methods and data in digital societies, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794117700709

Smith, D.R. (2016). Imagining others more complexly: Celebrity and the ideology of fame among YouTube’s ‘Nerdfighteria’, Celebrity Studies, 7(3), 339-353, https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2015.1132174

Socialblade (2016). Top youtuber channels from Spain. https://bit.ly/2ISEngv

Strauss, W., & Howe, N. (2000). Millennials rising: The next great generation. New York, NY: Vintage Original.

Westenberg, W. (2016). The influence of youtubers on teenagers. Master Thesis. University of Twente.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El presente estudio se centra en la relación entre preadolescentes y youtubers, con el objetivo de observar cómo los primeros integran a los youtubers como referentes de una cultura digital juvenil. Desde una perspectiva sociopsicológica y comunicativa, se aplicó un diseño metodológico mixto para llevar a cabo el estudio de audiencia, organizado en dos partes: un análisis cuantitativo de la audiencia a través de un cuestionario administrado a 1.406 estudiantes de once-doce años de institutos en Cataluña, y un análisis cualitativo de la audiencia preadolescente a partir de tres «focus group». Los datos cuantitativos se analizaron con SPSS y los cualitativos con la ayuda del programa Atlas.ti. Los resultados demuestran que los preadolescentes consideran a los youtubers como referentes para el entretenimiento y por su proximidad a una cultura digital juvenil, pero no realmente como modelos o portadores de valores en tanto que «influencers». Además, los preadolescentes muestran alguna dimensión de Alfabetización Mediática, al identificar las estrategias comerciales de los youtubers y sus roles profesionales. El estudio da cuenta de un sesgo de género en algunos aspectos, y resulta una introducción a la observación sobre las funciones sociales de los youtubers entre los adolescentes, personas que están en pleno proceso de construcción de sus identidades y a punto de convertirse en jóvenes adultos.

1. Introducción y estado de la cuestión

Las actuales generaciones de adolescentes y jóvenes, los denominados «millenials» (Strauss & Howe, 2000), han nacido y crecido en un ambiente mediatizado, por lo que su ecosistema «natural» se puede describir como el del entorno 2.0 de las redes sociales. Diversos estudios han destacado a menudo el papel de los medios de comunicación en el proceso de socialización de niños y jóvenes (Arnett, Larson, & Offer, 1995), en referencia, hasta hace pocos años, a los llamados medios de masas tradicionales. En el actual ecosistema mediático (Jenkins, 2006), colonizado por innumerables dispositivos, pantallas, redes sociales y aplicaciones, los jóvenes tienen cada vez más opciones entre las que elegir y tienen acceso a ellas a una edad cada vez más temprana.

La compleja relación entre los medios y los jóvenes permitió durante el siglo pasado la identificación de los jóvenes como un determinado nicho de mercado para posteriormente establecer, o más bien reconocer, una etapa clave del desarrollo humano. Primero fue en la década de los 50, cuando los adolescentes o «teens», jóvenes de entre 13 y 19 años de edad, fueron objeto de interés por parte del cine, la radio y la televisión (Davis & Dickinson, 2004; Ross & Stein, 2008). Y ya en la década de los ochenta, los preadolescentes o «tweens», jóvenes entre 9 y 13 años, fueron identificados como un segmento de mercado aparte (Ekström & Tufte, 2007), unos jóvenes consumidores que, como preadolescentes, no son ni niños ni adultos (Linn, 2005); están «entre el ser y el devenir», como señalan Larocca y Fedele (2017).

La psicología y la sociología nos han mostrado que la adolescencia es una etapa clave de la vida y del desarrollo en la que la persona se va definiendo como individualidad, a la vez que toma decisiones relacionadas con cuestiones fundamentales (académicas, de género, etc.) que influirán en su vida futura. Por tanto, los adolescentes son más susceptibles a la influencia del entorno en la construcción de su «yo» (Bernete, 2009), y por ello resulta esencial comprender cómo interactúan con el entorno digital (Blomfield & Barber, 2014).

En relación a YouTube, también se considera que la interacción de los niños implica elementos como la colaboración con su grupo de pares y con la familia, la interacción con otros usuarios, las oportunidades de aprendizaje, el compromiso cívico y la formación de la identidad (Lange, 2014; Lenhart & al., 2015), pero todavía falta investigación sobre la forma en que los llamados «influencers» pueden actuar como guías en los procesos de socialización y construcción identitaria de los preadolescentes.

Además, tal y como recoge Fedele (2011), sabemos que el público puede atribuir a los medios cuatro tipos principales de funciones sociales: funciones de entretenimiento (por ejemplo, diversión, humor, pasar el tiempo, evitar el aburrimiento, evasión de la rutina), funciones de situación de consumo (por ejemplo, función ritual, estructural y relacional), funciones narrativas (por ejemplo, funciones bárdica y narrativa) y funciones de socialización (por ejemplo, función identitaria, comunitaria, de aprendizaje sobre la realidad, función modeladora, función de compartición con el grupo de pares a través de conversaciones, función de identificación y admiración con y hacia los personajes, relaciones parasociales con los personajes). En cuanto a las funciones sociales, redes sociales como Instagram, Facebook y YouTube se han convertido en un área relevante de interrelación social para los adolescentes en el contexto de su proceso de construcción de la identidad (Ahn, 2011). En el caso de YouTube, según Pérez-Torres y otros (2018: 63), los jóvenes usuarios muestran un uso mayoritariamente pasivo, una característica que puede favorecer en gran medida el rol de los youtubers como modelos de referencia en la construcción de la identidad juvenil.

A partir de estas premisas teóricas, el objetivo general de este estudio es observar cómo los preadolescentes integran a los y las youtubers como referentes de una cultura digital adolescente, es decir, descubrir qué atrae a los preadolescentes de los youtubers, cuáles son las funciones sociales que les atribuyen, y cómo integran en sus vidas los modelos y valores propuestos por los youtubers, en su capacidad como «influencers».

La presente investigación combina diferentes perspectivas teóricas: un enfoque constructivista; la tradición de los estudios culturales; la teoría de usos y gratificaciones, y una perspectiva de género, dado que estudios previos señalan que niñas y niños utilizan las redes sociales de manera diferente (Oberst, Chamarro, & Renau, 2016).

1.1. La eclosión de los youtubers como una «performance auténtica» para los jóvenes

La eclosión de los youtubers se produce en 2012, con el cambio de la interfaz de YouTube, y ya en 2016 YouTube se convierte en la segunda red social más grande del mundo, después de Facebook, y la primera en contenido digital, como indican Bonaga y Turiel (2016: 128).

Como señalan dichos autores, la plataforma combina la sensación de intimidad deseada entre usuarios y youtubers, con la habilidad de posicionar vídeos gracias a los motores de búsqueda (YouTube usa el análisis de Big Data). Además de los beneficios económicos y del enorme mercado global que representa la plataforma, los youtubers pueden convertirse al mismo tiempo en marcas comerciales y modelos a seguir (Lovelock, 2017), especialmente entre los más jóvenes. La capacidad para improvisar, cambiar y sorprender se aleja tremendamente de la programación guionizada y hermética de los medios tradicionales, lo cual hace que los youtubers resulten muy atractivos para los adolescentes. Según Montes-Vozmediano, García-Jiménez y Menor-Sendra (2018: 68), «los vídeos de adolescentes se ven el doble, y los de los youtubers son los de mayor impacto».

La conceptualización de los youtubers como microcelebridades de la Web 2.0 conecta con la definición de Senft (2012), que señala «el doble aspecto de la presentación ‘auténtica’ de uno mismo en las redes sociales como una ‘identidad de marca’ con el sabio manejo de esa ‘autenticidad’ con fines comerciales». Como afirma Smith (2017: 3), «la microcelebridad está plagada de dificultades en torno a la autenticidad versus la autopromoción interesada (Senft, 2012), y la negociación de la intimidad con el interés comercial (Abidin, 2015)». Por un lado, hay una corriente de investigación sobre los «Celebrity studies» que analiza a los youtubers y vloggers más allá de los intereses comerciales, enmarcando a las celebridades 2.0 en «un estado de ‘mismidad’ que permite a cada persona un mismo espacio para consumir una visión única de sí mismos» (Smith, 2016: 1). Por otro lado, varios estudios señalan los marcadores simbólicos de «autenticidad» de las celebridades como representaciones de la clase trabajadora (Biressi & Nunn, 2005; Oliva, 2014).

En tanto que microcelebridades, los youtubers de éxito, a quienes Bonaga y Turiel (2016: 120) definen como «creadores», tienen la cualidad de llegar a ser «influencers»: «Como el propio nombre indica, se trataría de toda aquella persona que mediante la capacidad de comunicación logra influir en los comportamientos y opiniones de terceras personas». Jerslev (2016) también afirma que «las estrategias de microcelebridad están conectadas sobre todo con la exhibición de accesibilidad, presencia e intimidad online».

En consecuencia, los youtubers son una parte integral de la cultura adolescente en tanto que «influencers», protagonistas y guías iniciáticos en el consumo de productos multimediáticos dirigidos, directa o indirectamente, al «target» adolescente. El hecho de que muchos youtubers existosos sean a su vez jóvenes hace aún más valioso el análisis de su relación con los internautas adolescentes (Westenberg, 2016), ya que pueden actuar como modelo a través de mecanismos de identificación y admiración (es decir, pueden responder a una función de socialización).

Para actuar como un modelo a seguir o «role model» (Calhoun, 2010), el comportamiento de esa persona o su éxito puede ser emulado por otros, especialmente por personas más jóvenes. Esta noción está relacionada con los modelos aspiracionales (reales o ficticios), que deben mostrarse lo suficientemente lejanos como para constituir un objeto de deseo, pero no tan distantes como para ser percibidos como inaccesibles o de manera que se pierda toda posibilidad de contacto (Massonnier, 2008: 47).

La función identitaria, los procesos de identificación y empatía con los personajes, e incluso la relación parasocial que las audiencias pueden establecer con ellos han sido destacados como usos mediáticos durante décadas (Hoffner & Buchanan, 2005; Iguartua-Perosanz & Muñiz-Muriel, 2008; Livingstone, 1988). En este sentido, muchos seguidores de youtubers, especialmente aquellos que lo han sido durante tiempo («followers»), esperan de ellos ciertos elementos familiares que los conectan con sus youtubers, como saludos, apodos o «ciertos dispositivos lingüísticos (por ejemplo, vocales muy enfatizadas o alargadas) (Draga, 2016a) para conseguir efectos cómicos o lúdicos, invitando así a comentarios bromistas e inyectando alegría en la comunidad» (Cocker & Cronin, 2017: 8), y estos mismos seguidores protestarán si estos conectores no aparecen de manera regular.

A pesar de las diferencias de formato y oportunidades de interacción entre la television e Internet, e incluso de una percepción entre los adolescentes de mayor libertad para interactuar con Internet (Aranda, Roca, & Sánchez-Navarro, 2013), existen mecanismos psicológicos que se activan de manera similar entre los seguidores de la ficción seriada televisiva y los de las redes sociales.

Por esta razón, como se explica más adelante, las categorías que normalmente se utilizan para los personajes de ficción se adoptan en este estudio para analizar qué les gusta a los preadolescentes de los youtubers, a partir de la suposición de que los llamados «influencers» no dejan de ser representaciones de personas reales.

2. Material y métodos

En el presente estudio de la audiencia se empleó un enfoque metodológico mixto (Creswell & Plano-Clark, 2007), en concreto un diseño explicativo secuencial (Creswell, 2014), que se dividió en dos fases: 1) Un análisis cuantitativo de la audiencia mediante un cuestionario; 2) Un análisis cualitativo de la audiencia a través de grupos de discusión. La protección de los participantes se garantizó en la investigación, de acuerdo con los protocolos aprobados por la institución financiera y por el Comité de Ética en Investigación de la Universidad Ramón Llull de Barcelona.

2.1. Descripción de los perfiles de los youtubers

Se seleccionaron 10 de los 20 youtubers hispanohablantes con más seguidores (Socialblade, 2016) para asegurar el equilibrio en términos de género y variedad de categorías temáticas de los canales de YouTube (videojuegos, música, memes/bromas, belleza/moda...). Los youtubers seleccionados fueron, en orden decreciente de suscriptores: ElrubiusOMG, Vegetta777, Willyrex, ZacortGame, ElrincondeGiorgio, Wismichu, Staxx, Auronplay, ExpCaseros y YellowMellowMG.

Debe destacarse el predominio de los canales relacionados con los videojuegos (en línea con los hallazgos de Gómez-Pereda, 2014), así como los canales vinculados al entretenimiento y, en el caso de ExpCaseros, los experimentos de autoaprendizaje. Estos diez youtubers pueden considerarse «influencers», ya que tienen más de un millón de suscriptores (Berzosa, 2017), se presentan a sí mismos como creadores, utilizando generalmente un lenguaje basado en el humor y la proximidad y, en la mayoría de los casos, están presentes y son activos en otros canales y medios, de acuerdo a una verdadera estrategia transmediática.

2.2. Instrumentos de análisis2.2.1. El cuestionario

Tras una encuesta piloto (n=85) para probar y validar la herramienta metodológica en tres institutos de secundaria de Barcelona se desarrolló el cuestionario definitivo para identificar qué buscan los preadolescentes en el mundo de los youtubers y si se proyectan en ellos de alguna manera.

Para la encuesta definitiva se diseñó un formulario de Google titulado «Preferencias de los jóvenes» que se administró online en las aulas en presencia de los docentes. Los institutos fueron contactados por correo electrónico y los profesores fueron instruidos sobre cómo administrar el cuestionario, recibiendo la indicación de no mencionar explícitamente la palabra «YouTube».

El cuestionario, escrito en las dos lenguas oficiales de Cataluña (catalán y castellano), constaba de dos partes:

• Cinco preguntas sobre datos sociodemográficos (edad, sexo, escuela, etc., respetando el anonimato),

• Ocho preguntas sobre el tema del estudio: una de naturaleza abierta y el resto con respuestas cerradas (algunas de opción múltiple y otras en una escala de Likert de cinco puntos).

Entre otras cuestiones, se preguntó a los encuestados las razones por las cuales estaban interesados en los 10 youtubers de la lista. Las características que tenían que valorar se basaban en una tipología de análisis de personajes de ficción: identificación con un personaje, admiración hacia un personaje, «coolness» (si el personaje les parecía «guay»/«cool»), cercanía de los personajes a sus propios intereses, entretenimiento y funciones de socialización, como la compartición con su grupo de iguales ( Buckingham, 1987; Fedele, 2011; García-Muñoz & Fedele, 2011; Iguartua-Perosanz & Muñiz-Muriel, 2008; Medrano & al., 2010).

La encuesta fue administrada durante el mes de diciembre de 2016 a alumnos del primer curso de ESO (Educación Secundaria Obligatoria, 11-12 años de edad) de 41 institutos públicos y privados de Cataluña, lo que arroja un total de 1.406 respuestas válidas, 716 niñas (50,9%) y 690 niños (49,1%). En cuanto a la edad, el 87,1% (n=1.224) de los participantes tenían 12 años, con una edad media de x=12,11 (mediana=12, moda=12).

Se empleó el software SPSS para realizar tanto el análisis descriptivo, mediante tablas de frecuencia y estadísticos descriptivos (media, moda, mediana y desviación estándar) como el análisis bivariante, llevado a cabo mediante las pruebas de Chi cuadrado, Mann-Whitney y Kruskal-Wallis, según el tipo de variable (nivel de significación p <0,05).

2.2.2. El guion de los grupos de discusión

El objetivo de los grupos de discusión fue ahondar en los sentimientos de los preadolescentes y en su interés hacia los youtubers. Los moderadores siguieron un guion a partir de preguntas semiestructuradas, que se agruparon en 21 categorías basadas en las variables de la fase cuantitativa, entre las cuales, a los fines de este artículo, se destacan las siguientes:

• Funciones de los youtubers, como identificación, admiración, buena onda («coolness»), cercanía, entretenimiento, funciones relacionadas con el grupo de pares.

• Alfabetización mediática, como procesos mediáticos de producción y difusión (Ferrés & Piscitelli, 2012); el papel de los youtubers como actores y profesionales.

Los tres grupos de discusión, cada uno de seis participantes (tres chicos y tres chicas), se realizaron entre los meses de enero y marzo de 2017. Los participantes se seleccionaron de acuerdo con los siguientes criterios: la disponibilidad de la escuela y de los alumnos, que estos fuesen habladores, y con diferentes niveles de interés en la asignatura «Tecnología de la información». Los grupos de discusión se grabaron y se transcribieron literalmente para ser analizados siguiendo el procedimiento del análisis temático (Braun & Clarke, 2006). El proceso de codificación fue llevado a cabo por cuatro investigadores agrupados por parejas y por una instructora oficial de Atlas.ti, que discutieron cómo clasificar las respuestas hasta llegar a un consenso final. El análisis cualitativo se efectuó con la ayuda del software Atlas.ti.

Los resultados de las contribuciones de los grupos de discusión se identificaron de la siguiente manera: Número del grupo focal (FG1, FG2, FG3) + Participante (Chico/Chica) + Número de participante (por orden de intervención).

3. Análisis y resultados

3.1. Preferencias de los preadolescentes relativas a los youtubers

Los youtubers de la lista más reconocidos por los preadolescentes en la encuesta fueron AuronPlay (78,2%, n=1.120), ElrubiusOMG (74,1%, n=1.042) y Wismichu (66,4%, n=933). Además, los participantes podían indicar otros youtubers que les gustaran, opción escogida por el 55,3% (n=777) de la muestra, con 271 youtubers diferentes mencionados, un hecho que demuestra una gran diversidad en lo que los preadolescentes ven en YouTube. El resto de youtubers mencionados incluyen a DjMaRiio (2,7%, n=38) y a dos mujeres, Dulceida (2,6%, n=36) y Yuya (1,2%, n=17).

3.2. Funciones sociales atribuidas a los youtubers

Las funciones sociales atribuidas por los participantes variaron en gran medida según cada youtuber, como se muestra en la Tabla 1, siendo la función de entretenimiento la más valorada. En particular, con respecto a la segunda función más valorada, la cercanía a los propios intereses de los preadolescentes, debe destacarse que es la opción más valorada en el caso de ExpCaseros (35,5%, n=249), el único youtuber cuyo canal se centra en experimentos de autoaprendizaje. Por otro lado, tanto la atracción por la notoriedad («coolness»), como las funciones de socialización son atribuidas a los youtubers por más del 10% de los preadolescentes de la muestra. Finalmente, los elementos relacionados con la identificación y la admiración son valorados por un menor número de encuestados.

Se observan diferencias de género significativas en las valoraciones de la mayoría de los youtubers propuestos, más evidente en el caso de los youtubers masculinos (Auronplay: p<0,001; ElRubiusOMG: p <0,001; Vegetta777: p <0,001; Willyrex: p=0,001; Zacortgame: p <0,001) en comparación con la única youtuber de la lista, YellowMellowMG (p=0,022). En particular, los chicos tienden a valorar más la función de identificación (incluso en el caso de YellowMellow), mientras que las chicas tienden a valorar más las funciones de socialización. Además, especialmente en el caso de los canales de videojuegos, los chicos valoran más la proximidad a sus intereses, mientras que las chicas valoran más la función de entretenimiento. Finalmente, en cuanto a las funciones de admiración, los chicos valoran más atributos como «inteligente» y «malote» (también en el caso de YellowMellowMG), mientras que las chicas valoran más que un youtuber masculino sea «atractivo».

En términos de identificación, es relevante que 9 de los 10 youtubers propuestos sean hombres, lo cual es un motivo más que probable de que las chicas no elijan esta función.

De nuevo cabe destacar el caso ExpCaseros, ya que no se muestran diferencias significativas de género en relación a este youtuber que se dedica a experimentos de autoaprendizaje, dado que a chicas y chicos les gusta por las mismas razones, incluida la cercanía a sus intereses.

En relación a la opción abierta existen diferencias de género significativas (p=0,001), sobre todo en los casos de Dulceida, que solo es mencionada por chicas (5%, n=36) y de DjMaRiio, que solo es mencionado por chicos (5,5%, n=38).

El número de menciones a youtubers realizadas en la fase cualitativa coincide con los tres primeros youtubers de la lista cuantitativa, AuronPlay, ElRubiusOMG y Wismichu, pero también hay muchos otros comentarios sobre otros youtubers, como Dulceida y Yuya.

Las características recurrentes más mencionadas por los participantes son los conocimientos de los youtubers (función de admiración) y su humor (función de entretenimiento), particularmente en el caso de Hamza Zaidi (a pesar de no estar incluido en la lista), aunque también se evidencia la importancia otorgada a la identificación y a la percepción de cercanía con algunos youtubers, como se puede ver en el siguiente fragmento de FG3:

– FG3-Chico1: Hamza. Hamza Zaidi. Es de Marruecos, pero es español y habla español y todo, y es muy gracioso.

– Moderadora: ¿Y lo imitas? ¿O qué tiene de gracioso?

– FG3-Chica2: No, es que a veces usa expresiones que repetimos... [...] no nos reímos de él.

– Moderador: Entonces no os reís de él, pero es divertido.

– FG3-Chico1: No, lo hace a propósito. Por ejemplo, en lugar de decir «cama», dice «caaaaama».

– Moderadora: ¿Y eso lo repetís cuando estáis en el patio de recreo y así?

– FG3-Chico1: Sí.

3.3. Dimensiones de la alfabetización mediática

Tanto en las preguntas abiertas del cuestionario como en la fase cualitativa, varios comentarios denotan un cierto grado de alfabetización mediática en los participantes, ya que son capaces de identificar tanto los procesos de producción como los requerimientos de difusión de los medios, así como lo que significa ser un youtuber.

En primer lugar, en el cuestionario se les formulaba en una pregunta con una opción abierta sobre si había algún aspecto que no les gustara de YouTube. Algunos de ellos indican, en la opción abierta, elementos que pueden clasificarse como mecanismos comerciales de YouTube (3,5%, n=49) –como la campana, el «clickbait» y, en general, los anuncios–, la falta de «netiquette» y los comportamientos groseros de algún youtuber en concreto (5%, n=70), y los riesgos para los menores (0,4%, n=6), como en el caso de la protección de su identidad y privacidad. Además, en la fase cualitativa, los preadolescentes manifiestan un conocimiento explícito (FG3Chico2: «Google paga por la monetización en YouTube»; FG3Chico1: «Y si sacas anuncios [en tu canal] te pagan más») o implícita de las dinámicas y demandas comerciales de los youtubers.

Esta comprensión implícita está relacionada con los motivos de agrado o desagrado por los youtubers, ya que los participantes, en particular las chicas, son críticos con los comentarios o comportamientos ofensivos. Por ejemplo, los dos primeros youtubers del «ranking», AuronPlay y Wismichu, calificados favorablemente como «malotes», resultan también impopulares entre algunos participantes en los grupos de discusión, mientras que uno de los youtubers que merece más comentarios y la mejor valoración por su autenticidad, su conocimiento y el respeto hacia sus seguidores es la youtuber Yuya:

– FG3-Chica1: (No me gustan) los chulos. Por eso me gusta Yuya, porque tiene muchos seguidores pero ella no ha cambiado (...) y respeta a sus seguidores más que los demás.

– FG3-Chico4: Ella es muy tranquila, sí que lo es. (...)

– Moderadora: ¿Es ella así realmente? ¿No es una pose?

– FG3-Chica1: No, ella es así.

En segundo lugar, casi todos los chicos y chicas de los grupos de discusión reconocieron que había una diferencia entre el personaje en YouTube –con sus pros (fama y dinero) y contras (pérdida de intimidad y de anonimato, riesgos asociados con la fama)–, y la persona real:

– FG1-Chico3: Y muchos youtubers también dicen que a menudo representan a un personaje en YouTube, pero luego son muy diferentes.

– Moderadora: ¿Eso dicen?

– (Algunos): Sí. [...]

– FG3-Chico3: Por ejemplo, Wismichu dijo en un vídeo que él aparecía como alguien muy gracioso en los vídeos, pero que en la vida real era más serio.

– FG3-Chico2: Yo también vi un vídeo con youtubers... y cuando los ves en ese vídeo son muy amables y amistosos, pero cuando hacen sus propios vídeos se vuelven más desagradables. Dicen cosas como: «No me gusta eso», o «¡Sal de aquí!»

Por otro lado, los participantes reconocen el rol de los youtubers como profesionales y trabajadores. En el cuestionario, el 4,5% (n=63) de los encuestados dijeron que de mayores les gustaría ser youtubers, una opción escogida más por chicos (7,2%, n=50) que por chicas (1,8%, n=13) (p<0,001), mientras que 9 participantes (0,6%), 2 chicas y 7 chicos, indicaron que ya tenían un canal propio en YouTube. En los grupos de discusión, los participantes también señalaron que ser un youtuber podría ser una profesión rentable y agradable, aunque también podría resultar muy estresante y llena de desafíos.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

El objetivo de la investigación ha sido profundizar en los riesgos y las oportunidades asociados a la relación entre preadolescentes y unos agentes concretos de las redes sociales, los youtubers. Los resultados cuantitativos y cualitativos nos han permitido responder al objetivo general.

En relación con las preferencias de los preadolescentes y las funciones de los youtubers en la vida de estos jóvenes, por un lado, se puede afirmar que lo que más atrae a los preadolescentes es el entretenimiento y la sensación de formar parte de una cultura digital juvenil, que pueden compartir con su grupo de iguales. Por otro lado, incluso reconociendo algún tipo de atracción por el modelo de notoriedad que encarnan los youtubers, desconfían de esa fama a corto plazo y de los riesgos relacionados con este trabajo; también tienen reservas sobre ciertas actitudes y códigos que expresan los youtubers dado que pueden ser ofensivos.

Respecto a la posible capacidad de los youtubers para fomentar modelos de influencia, hemos observado que las características valoradas dependen en gran medida del youtuber en particular. En el momento en que se completó este estudio, los youtubers más conocidos por los preadolescentes eran AuronPlay, ElrubiusOMG y Wismichu, que también fueron percibidos como los más divertidos. Pero cuando se les pidió a los participantes que mencionasen espontáneamente qué youtubers les gustan y por qué, emergieron muchos más, incluidas youtubers mujeres como Dulceida y Yuya, lo que significa una mejor representatividad de la diversidad de origen étnico y de género, así como también aparece una más amplia variedad de temáticas por lo que se refiere a los canales de YouTube.

Los preadolescentes valoran sobre todo el humor de los youtubers, y en un lejano segundo lugar valoran la proximidad de los youtubers a los propios intereses de los jóvenes; es decir, las funciones de entretenimiento y socialización señalan hacia la compartición de contenido con sus iguales. Es significativo que Yuya sea la youtuber que recibió los comentarios más favorables y que los motivos fueran por sus conocimientos, su buena relación con sus seguidores y su autenticidad.

Como factores de atracción destacan aspectos como la «coolness» o la identificación con algún youtuber y el poder compartirlo con los compañeros, ítems que obtienen una valoración más alta que otros, como la apariencia o la inteligencia de los youtubers.

Los participantes de nuestro estudio están familiarizados con los youtubers en tanto que figuras públicas y microcelebridades, pero admiran su vis cómica y sus conocimientos más que su aspecto físico o la imagen de marca que puedan representar. No son valoraciones con porcentajes muy elevados pero todas ellas están referidas al entretenimiento y la sociabilidad, sin que por ello se pueda deducir el deseo de los participantes de sentirse reflejados en los llamados «influencers».

Podemos considerar que los youtubers están incorporados en las prácticas de ocio de los preadolescentes y que actúan ya como referentes de una cultura digital adolescente, pero no podemos referirnos propiamente a una integración de los modelos y valores propuestos por los youtubers en tanto que «influencers», sobre todo dada la actitud crítica que los preadolescentes manifiestan sobre ellos. En este sentido es relevante que cuando se les pregunta a los preadolescentes qué quieren ser de mayores, ser youtuber se considera más un «hobby» que una profesión.

Por lo tanto, se puede concluir que YouTube todavía tiene un impacto limitado en los jóvenes en esta etapa del desarrollo de su identidad.

Esto no disminuye el hecho de que los preadolescentes conocen e imitan el lenguaje y expresiones de los youtubers, o siguen a los que les gustan, e incluso disfrutan con algunos de los youtubers «malotes», ni tampoco significa que no reconozcan los riesgos de la pérdida de intimidad y los abusos que se presentan o amplifican en el espacio digital. Los participantes de nuestro estudio son conocedores de lo que conocemos como alfabetización mediática, con sus comentarios sobre los procesos de producción y difusión y, en menor medida, sobre las dimensiones de ideología y valores (Ferrés & Piscitelli, 2012): comentan estrategias comerciales, se sienten cómodos usando datos y términos técnicos con propiedad, como «monetización», y son muy críticos con las actitudes ofensivas y discriminatorias.

Por último, el sesgo de género resulta evidente no solo por la menor presencia de youtubers mujeres y por las funciones sociales atribuidas a los youtubers, sino también en el hecho de que los chicos triplican el número de chicas que han tenido un canal de YouTube y casi cuatriplican a las chicas interesadas en un futuro profesional como youtubers.

Es necesario investigar más sobre elementos de exclusión o sobre la función de refugio que las redes sociales podrían ejercer sobre los chicos y las chicas más jóvenes, como señalan Michikyan y Suárez-Orozco (2016: 413): «La conciencia mantiene un papel protector consistente con el tiempo, mientras que los contextos hostiles en el aula aumentan la vulnerabilidad en el tiempo, especialmente para las niñas». También se requieren nuevas investigaciones que analicen las diferencias según el grupo de edad y si las redes sociales fomentan el desarrollo de características individuales y diferenciadas entre las nuevas generaciones –en el sentido del espejismo de la diversidad social e identitaria en las plataformas, según Jenkins (2006)–, y si los jóvenes las utilizan tanto como consumidores como prosumidores. Coincidimos con Pérez-Torres y otros (2018), cuando señalan que es recomendable aumentar la muestra de youtubers, utilizando criterios de selección que no se basen en el número de seguidores, y extender el análisis a blogs e Instagram.

Totalmente incorporados en el ecosistema digital, da la impresión de que los preadolescentes están a punto de dar el salto a la plena adolescencia y que, una vez allí, se pueden sentir más huérfanos de referentes. En este sentido, consideramos que deberían tener mayor protagonismo las propuestas de educomunicación en los centros educativos y la noción de prosumidor. YouTube y los youtubers no deben servir solo como una especie de información animada o para señalar a los culpables del actual «mercado del ego» (Rivière, 2009); los youtubers forman parte de las oportunidades y de las servidumbres del sistema neoliberal en el que vivimos, incluidos los estereotipos de género.

Apoyos

Este estudio forma parte de los Proyectos Tractor (2017), apoyado por la Universidad Ramon Llull de Barcelona y la Fundación La Caixa (España), y fue financiado por el Consejo Audiovisual de Cataluña (CAC): Ayuda a la investigación 49/2016.

Referencias

Ahn, J. (2011). The effect of social network sites on adolescents´ social and academic development: current theories and controversies. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(8), 1435-1445. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21540

Aranda, D., Roca, M., & Sánchez-Navarro, J. (2013). Televisión e Internet. El significado de uso de la red en el consumo audiovisual de los adolescentes. Quaderns del CAC, 39(XVI), 15-23. https://bit.ly/2si7mTQ

Arnett, J.J., Larson, R., & Offer, D. (1995). Beyond effects: adolescents as active media users. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 24, 511-518. https://bit.ly/2KWwebl

Bernete, F. (2009). Usos de las TIC, relaciones sociales y cambios en la socialización de los jóvenes. Revista de estudios de juventud, 88, 97-114. https://bit.ly/2kwxkzo

Berzosa, M. (2017). Youtubers y otras especies. Barcelona: Ariel-Fundación Telefónica.

Biressi, A., & Nunn, H. (2005). Reality TV. Realism and revelation. London: Wallflower Press.

Blomfield, C.J., & Barber, B.L. (2014). Social networking site use: Linked to adolescents’ social self-concept, self-esteem, and depressed mood. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66, 56-64. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12034

Bonaga, C., & Turiel, H. (2016). Mamá, ¡quiero ser youtuber!. Barcelona: Planeta.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Buckingham, D. (1987). Public secrets: Eastenders and its audience. London: BFI.

Calhoun, C.J. (Ed.) (2010). Robert K. Merton: Sociology of science and sociology as science. New York: Columbia UP.

Cocker, H., & Cronin, J. (2017). Charismatic authority and the youtuber. Unpacking the new cults of personality. Marketing Theory, 17(4), 455-472. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593117692022

Creswell, J.W. (2014). Research design. Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (4th. ed.). Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J.W., & Plano-Clark, V.L. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Davis, G., & Dickinson, K. (Eds.) (2004). Teen TV: Genre, consumption, identity. London: BFI.

Ekström, K.M., & Tufte, B. (Eds.) (2007). Children, media and consumption. On the front edge. Göteborg: Göteborg University.

Fedele, M. (2011). El consum adolescent de la ficció seriada televisiva. Barcelona: UAB, Tesis Doctoral. https://goo.gl/mswUJC

Ferrés, J., & Piscitelli, A. (2012). Media competence. Articulated proposal of dimensions and indicators. [La competencia mediática: Propuesta articulada de dimensiones e indicadores]. Comunicar, 38(XIX), 75-82. https://doi.org/10.3916/C38-2012-02-08

García-Muñoz, N., & Fedele, M. (2011). Television fiction series targeted at young audience: Plots and conflicts portrayed in a teen series. [Las series televisivas juveniles: tramas y conflictos en una «teen series»]. Comunicar, 37, 133-140. https://doi.org/10.3916/C37-2011-03-05

Gómez-Pereda, N. (2014). Youtubers. Fenómeno de la comunicación y vehículo de transmisión cultural para la construcción de identidad adolescente. Universidad de Cantabria. https://bit.ly/2L0Amaa

Hoffner, C., & Buchanan, M. (2005). Young adults’ wishful identification with television characters: The role of perceived similarity and character attributes. Media Psychology, 7, 325-351. https://bit.ly/2sdcuta

Igartúa, J.J., & Rodriguez-de-Dios, I. (2016). Correlatos motivacionales del uso y la satisfacción con Facebook en jóvenes españoles. Cuadernos.info, 38, 107-119. https://doi:10.7764/cdi.38.848

Igartúa-Perosanz, J.J., & Muñiz-Muriel, C. (2008). Identification with the characters and enjoyment with features films. An empirical research. Communication & Society 21(1), 25-52. https://bit.ly/2LAkgVP

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture. New York: New York University Press.

Jerslev, A. (2016). In the time of the microcelebrity: Celebrification and the youtuber Zoella. International Journal of Communication, 10, 5233-5251. https://bit.ly/2shZq4T

Larocca, G., & Fedele, M. (2017). Television clothing commercials for tweens in transition: A comparative analysis in Italy and Spain. In E. Mora & M. Pedroni (Eds.), Fashion tales: Feeding the imaginary (pp. 407- 424). Peter Lang.

Lenhart, A., Smith, A., Anderson, M., Duggan, M., & Perrin, A. (2015). Teens, technology and friendships. Pew Research Center. https://bit.ly/2L0Hxzd

Linn, A. (2005). Consuming kids: The hostile takeover of childhood. New York: First Anchor Books.

Livingstone, S. (1988). Why people watch soap opera: An analysis of the explanations of British viewers. European Journal of Communication, 3, 55-80. https://doi:10.1177/0267323188003001004

Lovelock, M. (2017). ‘Is every youtuber going to make a coming out video eventually?’: YouTube celebrity video bloggers and lesbian and gay identity, Celebrity Studies, 8(1), 87-103. https://doi:10.1080/19392397.2016.1214608

Massonnier, V. (2008). Tendencias de mercado. Están pasando cosas. Buenos Aires: Granica.

Medrano-Samaniego, C., Cortés, P.A., Aierbe, A., & Orejudo, S. (2010). TV programmes and characteristics of preferred characters in television viewing: A study of developmental and gender differences. Cultura y Educación, 22(1), 3-20. https://doi:10.5944/educXX1.13951

Michikyan, M., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2016). Adolescent media and social media use: implications for development. Journal of Adolescent Research, 31(4), 411-414. https://doi:10.1177/0743558416643801

Montes-Vozmediano, M., Garcia-Jiménez, A., & Menor-Sendra, J. (2018). Teen videos on YouTube: Features and digital vulnerabilities. [Los vídeos de los adolescentes en YouTube: Características y vulnerabilidades digitales]. Comunicar, 54(XXVI), 61-69. https://doi.org/10.3916/C54-2018-06

Oberst, U., Chamarro, A., & Renau, V. (2016). Gender stereotypes 2.0: Self-representations of adolescents on Facebook. [Estereotipos de género 2.0: Auto-representaciones de adolescentes en Facebook]. Comunicar, 48(XXIV), 81-90. https://doi.org/10.3916/C48-2016-08

Oliva, M. (2014). Celebrity, class and gender in Spain: an analysis of Belén Esteban's image. Celebrity Studies, 5(4), 438-454. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2014.920238

Pérez-Torres, V., Pastor-Ruiz, Y., & Abarrou-Ben-Boubaker, S. (2018). Youtuber videos and the construction of adolescent identity. [Los youtubers y la construcción de la identidad adolescente]. Comunicar, 55, 61-70. https://doi.org/10.3916/C55-2018-06

Rivière, M. (2009). La fama. Iconos de la religión mediática. Barcelona: Noema.

Ross, S.M., & Stein, L.E. (Eds.) (2008). Teen television: Essays on programming and fandom. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Senft, T.M. (2012). Microcelebrity and the branded self. In J. Hartley, J. Burgess, J., & A. Bruns (Eds.), A companion to new media dynamics (pp. 346-354). Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

Smith, D. (2017). The tragedy of self in digitised popular culture: The existential consequences of digital fame on YouTube. Qualitative research, Special issue: Qualitative methods and data in digital societies, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794117700709

Smith, D.R. (2016). Imagining others more complexly: Celebrity and the ideology of fame among YouTube’s ‘Nerdfighteria’, Celebrity Studies, 7(3), 339-353, https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2015.1132174

Socialblade (2016). Top youtuber channels from Spain. https://bit.ly/2ISEngv

Strauss, W., & Howe, N. (2000). Millennials rising: The next great generation. New York, NY: Vintage Original.

Westenberg, W. (2016). The influence of youtubers on teenagers. Master Thesis. University of Twente.

Document information

Published on 30/09/18

Accepted on 30/09/18

Submitted on 30/09/18

Volume 26, Issue 2, 2018

DOI: 10.3916/C57-2018-07

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?