Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

Taking notes is a common strategy among higher education students, and has been found to affect their academic performance. Nowadays, however, the use of computers is replacing the traditional pencil-and-paper methodology. The present study aims to identify the advantages and disadvantages associated with the use of computer (typing) and pencil-and-paper (handwriting) for taking notes by college students. A total of 251 social and health science students participated in the study. Two experimental conditions were chosen: taking notes by hand (n=211), and taking notes by computer (n=40). Those that used computer-written notes performed better on tasks based on reproducing the alphabet, writing sentences, and recognizing words (p

1. Introduction

Traditional handwriting is becoming increasingly uncommon as the use of electronic devices increases. Computers are part of the work routines of a large number of professions, and electronic devices are used at all stages of the education cycle as learning tools for academic purposes (to study, to complete assignments, to take classroom notes and to search for information) (Sevillano-García, Quicios-García, & González-García, 2016). Many people record their thoughts by typing in multiple digital settings (blogs, websites, twitter messages, comments on social networks etc.). In fact, it is not uncommon to associate progress and innovation in the teaching and learning process with the use of computerised systems. It seems that in some schools in the USA and Germany, handwriting is no longer part of the curriculum. Students learn the alphabet as it appears on a computer keyboard (Paschek, 2013: 19). In short, handwriting is becoming less common due to the use of computers and smartphones.

Some studies have been very persistent in emphasising the advantages of keyboard typing over handwriting (Rogers & Case-Smith, 2002). This enthusiasm is not new: throughout history, whenever new technological tools have appeared, in one way or another they have moved into the field of education. This was the case, for example, with the now obsolete typewriter, whose educative values were highlighted in several publications of the time (Conard, 1935).

Recently there has been renewed interest in verifying the advantages or disadvantages of writing by hand or with a keyboard. However, results are far from being conclusive (Longcamp, Zerbato-Poudou, & Velay, 2005; Sülzenbrück, Hegele, Rinkenauer, & Heuer, 2011).

Some of these studies have been done with schoolchildren, emphasizing the superiority of handwriting with regard to both the reproduction of letters of the alphabet and the quality of written composition (Berninger, Abbott, Augsburger, & Garcia, 2009; Connelly, Gee, & Walsh, 2007). Others have highlighted the cognitive processes associated with digital writing, such as working memory (Bui & Myerson, 2014; Smoker, Murphy, & Rockwell, 2009), and the «qwerty» effect (Jasmin & Casasanto, 2012). The «qwerty» effect refers to the influence of the position of letters on the keyboard and the meaning of words. What we do know, however, is that taking notes in the classroom facilitates learning. It seems that a positive correlation exists between the amount of classroom notes taken and the amount of information encoded during the class (Bui, Myerson, & Hale, 2013). This advantage can be explained by the word generation effect (Rabinowitz & Craik, 1986), which indicates that when information is re-elaborated by a student it is more easily remembered than when it is only heard or read. However, quality of notes can be much more important than quantity, and this is consistent with the levels of processing theoretical framework (Craik & Lockhart, 1972). Extensive literature exists about this topic, mainly based on studies using handwriting (see meta-analysis in Kobayashi, 2005). As stated by Bui & al. (2013), it is possible that taking notes in class using digital devices changes the balance between quantity and quality. However, more empirical research on its effects on learning is needed.

Nowadays, considering the expansion of new technologies, the number of students taking notes with a computer or tablet is significantly increasing (Cassany, 2012; Weaver & Nilson, 2005), and the old fashioned pen-and-paper method is decreasing. Some studies encourage the use of electronic devices as aids for learning strategies (Hyden, 2005; Tront, 2007), whereas other researchers argue exactly the opposite claiming that these resources hinder and diminish students’ academic performance (Fried, 2008; Kay & Lauricella, 2011; Ragan, Jennings, Massey, & Doolittle, 2014).

Bui & al. (2013) designed several experiments to study the relationship between remembering information and different strategies for taking classroom notes. In one experiment, some participants took notes using laptops and others by hand. Those using computers obtained better results in short-term memory tasks, and the conclusion was that participants who used laptops to take classroom notes wrote more content and recalled more information in free short-term recall tasks. Recently, Beck (2014) tried to replicate and expand the experiment by Bui & al. (2013), but obtained considerably different results. He studied the differences between both short-term and long-term memory tasks. Beck’s (2014) study found that the computer was a powerful tool for registering quantitative information. Although university students taking notes with a laptop recorded significantly higher amounts of information, they did not reach significant differences in short-term or long-term memory tasks. However, students taking handwritten notes scored higher in memory tasks.

The lack of conclusive research about the advantages and disadvantages of using different approaches to taking classroom notes in different behavioral areas is noticeable, and it motivated us to study the consequences of several learning processes in higher education. Since it is increasingly common to see university students using computers (or tablets) as writing tools for taking classroom notes, writing assignments, and so on, the aim of our research was to discover the differences in the amount and quality of recalled information according to the notetaking procedure used: traditional handwriting or computer writing. Consequently, particular attention was paid to analysing the effects of information coding and recording methods on memory, in the framework of levels of processing (Cermak & Craik, 2104; Craik & Lockhart, 1972; Lockhart & Craik, 1990). This approach argues that tasks requiring only superficial processing result in lower recall performance than tasks requiring deeper processing. Thus, a hypothesis was formulated stating that the use of a computer, as it allows for a higher speed of notetaking, increases the quantity of classroom notes, but that the lower amount of time that computer-typing students spend processing is detrimental to the memory trace of the information.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

A total of 251 students of the University of Cadiz were evaluated. The students came from social and health science programmes (Psychology n= 134; Pre-school Teacher Education programme, n=57; and Primary School Teacher Education programme, n=60). A total of 54 students were men and 197 women, and their average age was 19.2, SD=1.2. They voluntarily participated in the study. All students were Spanish speakers, 9% were left-handed and 91% right-handed. Participants were distributed into two groups: (1) those who regularly took classroom notes using computer devices (n=40); and (2) those who regularly took handwritten classroom notes (n=211). The size of the groups reflects the sociological reality of students’ routine use of computers (or tablets) when taking classroom notes in the university.

2.2. Material and procedure

Participants completed all tasks in groups of approximately 40 students, using their own laptops or pen and paper. All students received information about his/her participation in a general psychology experiment, but they initially did not receive further explanation about the purpose of the study. The experiment was conducted during normal class time. The students participated voluntarily in the experiment, and they did not receive extra credits or any other academic compensation. At least two researchers were present during the experimental sessions in order to supervise students’ activities. Three different tasks were administered:

• Task 1. Repetitive surface processing task: write the letters of the alphabet in alphabetical order as many times as you can in 30 seconds. When the time was up, the examiner stopped the stopwatch and said loudly, «Time’s up», and all participants had to stop writing. Participants who were taking classroom notes by hand were provided with a sheet of paper. Students who used computers were asked to open a new word document, save it as a «.doc» file, and then submit it immediately to an e-mail address provided. The specific verbal instruction for this task was: «Write the letters of the alphabet in alphabetical order as many times as possible». Responses scored one point for each alphabet completed in the correct alphabetical order.

• Task 2. Verbal fluency repetitive task: write all the sentences you can in 2 minutes. The first sentence should start with the verb «write» (for handwriting participants) or with the verb «read» (for computer writing participants). Handwriting students received the following instruction: «Please write as many sentences as you can in the time given. The first sentence must start with «write» or, in the case of computer writing students, «to read»; all the others can be anything you like». Each correctly written and consistent sentence scored one point. Sentences considered illegible, misspelt, incorrect and/or inconsistent scored zero.

• Task 3. Memory Task. A list of 35 common words was presented. Words were written in the left column of a piece of paper or on the computer screen. Handwriting participants had to copy them in the right column of the paper, and computer typing participants had to copy the list on the right side of the word document. When the task was finished, all assignments were collected, and a «distracting task» was administered on a new piece of paper or document. The distracting task consisted of solving as many 5-figure multiplications as possible during 5 minutes. Immediately after the distracting task, participants were given 5 minutes to write all the words they could recall from the original word list that they had previously copied on a sheet of paper or on the computer (memory task). Next, a 5 minute break was provided. Finally, a word recognition task was administered, which consisted of a list of 40 words (35 true and 5 false) presented on a sheet of paper or on the computer screen. Participants had to indicate which words corresponded to the stimulus words that had originally been presented.

All tasks were administered in one 40-minute experimental session, during the 2014-15 and 2015-16 academic years. Tasks 1 and 2 were designed based on methodology used by Berninger & al. (2009). Task 3 was designed following methodology used by Smoker & al. (2009). Sessions were held in university classrooms where participants usually received their regular teaching. The lighting and sound conditions were acceptable and the students’ collaboration was satisfactory. Reliability between two observers was calculated for all students’ responses (reliability average was 95.8%).

3. Results

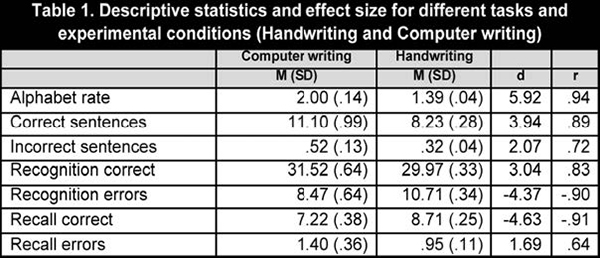

In order to analyse the differences between students’ scores on the three tasks proposed, a statistical descriptive analysis was carried out (table 1).

Table 1 shows that the group that worked with a computer wrote the alphabet a greater number of times and achieved a higher number of correct sentences. Moreover, their performance was higher in the recognition task. However, the results were the opposite in the recall task in which participants who were using handwriting obtained better results. The differences between both groups are relevant considering the effect size.

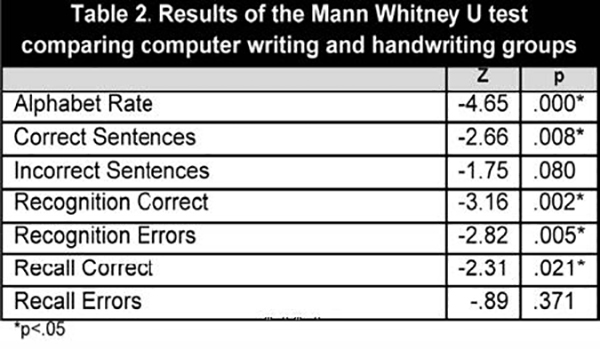

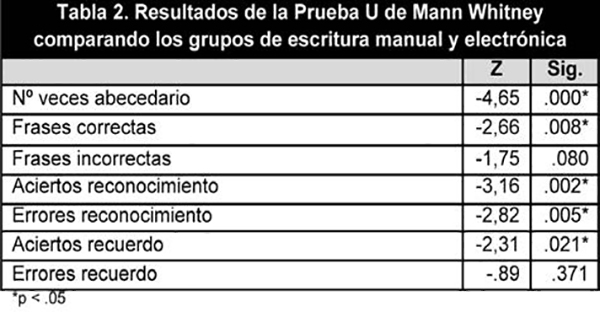

To compare whether the differences between the two groups were statistically significant, a one-way analysis of variance was calculated. In order to do this, the necessary quantitative principles were compared. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov (p<.05) comparison indicated that the sample was not normally distributed. Therefore, the ANOVA calculation as a procedure for hypothesis testing was not appropriate. Consequently, we chose the non-parametric Mann Whitney U test to check the null hypothesis: the differences between the two groups in the three tasks were not significant (table 2).

As can be seen in table 2, the differences between computer writing and handwriting experimental conditions were significant for several tasks. As was expected, students who took classroom notes by computer wrote the alphabet a higher number of times than those who used handwriting (p<.0001). In addition, the number of correct sentences written by the students was higher in the computer writing group (p<.008). Similarly, the number of incorrect phrases was also higher for this group, although non-significant differences between groups were found (p>.05).

With regard to the short-term memory tasks -the recognition and recall tasks- the differences were in function of the experimental conditions (computer writing and handwriting). In the recognition task participants using computer writing scored higher than those using handwriting. Differences were statistically significant for correct answers and errors. Students who used the computer got a higher number of correct responses on recognition tasks (p<.002), while handwriting students obtained a statistically significant higher number of errors (p<.005).

In the free recall task, the handwriting group achieved a better result. The number of recalled words was higher and statistically more significant for this group than for the computer writing group (p<0.021). The handwriting group made fewer errors, but the differences were not statistically significant (p>.05).

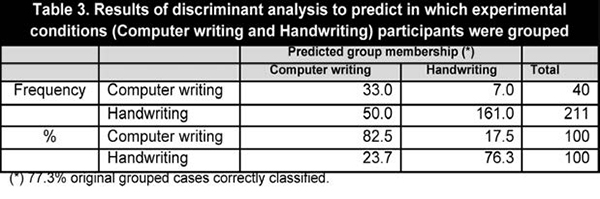

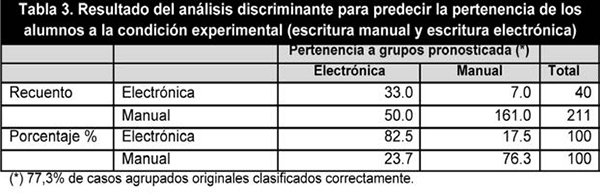

In addition, a discriminant analysis was performed between the two experimental conditions in order to obtain a mathematical function to classify students according to the discriminating variables, namely their scores in the three tasks. This technique provided a supervised statistical analysis data-vector classification procedure of the two categories (handwriting and computer writing conditions). The analysis was based on a mathematical decision-boundary-hyperplane able to statistically categorise both groups of participants, reducing the probability of misclassification. This distribution was compared to the data obtained in the experiment and a scattering matrix was constructed. This matrix was able to corroborate a diagonal line with the total proportion of correctly-classified participants. Moreover, the extra-diagonal data points represented the false positive and false negative classification process (table 3).

According to the discriminant analysis, 82.5% of participants from the condition «computer writing» were correctly classified. In addition, 76.3% were classified as belonging to the condition «handwriting». As a result, the data suggested that there was a characteristic pattern addressing the differences in the memory task achievement as a function of the information-recording approach. Because the number of participants in both conditions was dissimilar, it was concluded that a total of 77.3% of the original groups were correctly classified by the discriminant analysis.

At the same time, an equal group contrast using the Wilks’ Lambda test statistic was carried out. Then the result was calculated by Chi-square estimation. This multivariate analysis of variance rejected the equality between groups hypothesis (Wilks’ Lambda =.780; X2=60.98; p<0.0001). Consequently, it was concluded that the differences between participants of both experimental conditions were statistically significant, supporting the results shown in table 3.

4. Discussion and conclusions

This paper analyses how taking classroom notes by hand or computer is related to academic performance and immediate recall. Nowadays, digital keyboarding is very common in university classrooms, and there is a huge variety in the way that university students take notes and in what devices they use. Therefore, studies are being carried out to establish which procedures may increase significant information recall, and how students interpret content.

The activity in which higher education students usually spend most of the time during traditional lectures is taking notes (Moin, Magiera, & Zigmond, 2009). According to some studies, this activity involves cognitive processing and offers a higher probability for later recovery of content than when students only pay attention to the lecturer’s information without taking notes (Dunlosky, Rawson, Marsh, Nathan & Willingham, 2013). Notetaking is a multidimensional process because the students must pay attention to the explanation, select the relevant information and then translate it into specific phrases (Steimle, Brdiczka, & Mühlhäuser, 2009; Stefanou, Hoffman, & Vielee, 2008). Several higher order cognitive processes are involved in taking classroom notes, such as attention and memory. Considering the memory process, it seems that taking notes facilitates recall of information both qualitatively and quantitatively (Einstein, Morris & Smith, 1985; Fisher & Harris, 1973). This is one of the reasons why taking classroom notes is a very common student activity.

The results of this experiment suggest that the computer is an efficient tool for recording information because students using the computer could write the alphabet a greater number of times than those writing by hand. This data coincides with Beck’s (2014) study, which also found an improvement in the quantitative registration of information. Computer writing users also wrote more sentences than handwriting students did, which could be because these types of surface processing tasks can be enhanced by new technologies. However, the results we found in memory tasks significantly differed from those obtained by Bui & al. (2013), and are coincident with the data found by Beck (2014) in that handwriting students performed statistically significantly better than computer writing participants in the short-term free recall task. However, in the recognition task, computer writing students scored significantly higher results.

How can we explain these results? One possible explanation can be found in the levels of processing framework (Cermak & Craik, 2014; Craik, 2002). Performing a task that involves considering words as objects or sets of letters, as happens in taking classroom notes using computer devices, leads to very superficial processing. This kind of processing consequently affects the encoding and recall of content. The superficial processing may be successful in tasks that do not require deep processing, such as a recognition task involving short-term memory encoding. This explanation would support some results of our experiment. However, when a task involves processing words as semantic units, processing at a deeper level of analysis is required, making it more likely that the words will be remembered and that students will obtain better results in a free recall task. Using the computer as a tool for notetaking involves an initial advantage by increasing the amount of information recorded, as can be seen in the results for Tasks 1 and 2, but this efficiency is lower when the task demands a deeper coding level: this is more efficiently achieved using handwriting. The computer writing achievement is higher in those tasks where the retrieval of information requires a lower level of processing, whereas handwriting students’ performance is higher when the task requires a deeper encoding (Mueller & Oppenheimer, 2014; Treisman, 2014). When the information input needs to be «translated» to specialised codes, it leads to the formation of more complex mnemonic representations. For example, listening to a lecture requires a phonological processing, but writing the ideas heard also requires their «translation» into orthographic processing, which can facilitate information recall. The advantage of computer writing is clear as to the amount of notes that can be taken; however, this is not automatically transferred to the quality of the information collected. We can process information more deeply when we can organise it more significantly, and this can lead to longer-term learning (Bui & al., 2013).

There is still extensive room for research in this area, but it is possible that to progress from an automatic repetition of letters or words (Tasks 1 and 2 of our experiment) to writing full semantic and grammatically meaningful sentences (as happens when taking classroom notes in university settings) can be more efficiently done by hand. This way of taking notes increases memory processing because it appears to encourage more complex and stable memory links (Smoker & al., 2009). The Spanish writer Rafael Sánchez Ferlosio said that «in order to struggle against the secondary effects of amphetamine abuse, I spent a lot of time practising calligraphic tasks» (El País Semanal, 25-10-2015: 62). There is no data to support his intuition. However, in the face of current controversy, teachers could be making a mistake in suppressing handwriting from the school curriculum (Clayton, 2015): «Those who are skilled at handwriting will always have an advantage over those that just use computer writing as the only means of written communication. Technological advances could progress backwards and it is not unlikely that handwriting will replace keyboards in the future as the best way to interact with computers» (Clayton, 2015: 65). The current study suggests a research topic, linking the way university students take classroom notes to levels of information processing, and the possibilities of semantically coding the information. The differences that exist between handwriting and computer writing registering procedures should be analysed for tasks that require deeper levels of processing than simple transcription. Similarly, both short-term and long-term recall differences should be assessed.

References

Beck, K.M. (2014). Note Taking Effectiveness in the Modern Classroom. The Compass, 1(1). (http://goo.gl/7k4TOj) (2015-09-05).

Berninger, V.W., Abbott, R.D., Augsburger, A., & Garcia, N. (2009). Comparison of Pen and Keyboard Transcription Modes in Children with and without Learning Disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 32, 123-141. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/27740364

Bui, D.C., & Myerson, J. (2014). The Role of Working Memory Abilities in Lecture Note-taking. Learning and Individual Differences, 33, 12-22. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2014.05.002

Bui, D.C., Myerson, J., & Hale, S. (2013). Note-taking with Computers: Exploring Alternative Strategies for Improved Recall. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(2), 299-309. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0030367

Cassany, D. (2012). En línea. Leer y escribir en la Red. [On line. Reading and Writing on the Web]. Barcelona: Anagrama.

Cermak, L.S., & Craik, F.I. (2014). Levels of Processing in Human Memory (PLE: Memory) (Vol. 5). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Clayton, E. (2015). La historia de la escritura. [The History of Writing]. Madrid: Siruela.

Conard, E.U. (1935). A Study of the Influence of Manuscript Writing and of Typewriting on Children’s Development. The Journal of Educational Research, 29(4), 254-265. doi: 10.1080/00220671.1935.10880582

Connelly, V., Gee, D., & Walsh, E. (2007). A Comparison of Keyboarded and Handwritten Compositions and the Relationship with Transcription Speed. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(2), 479-492. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/000709906X116768

Craik, F. I. M. & Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of Processing: A Framework for Memory Research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11, 671- 684. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5371(72)80001-X

Craik, F.I. (2002). Levels of Processing: Past, Present... and Future? Memory, 10(5-6), 305-318. doi: http://dx.doi.org/0.1080/096582102440001

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K.A., Marsh, E.J., Nathan, M.J., & Willingham, D.T. (2013). Improving Students’ Learning with Effective Learning Techniques: Promising Directions from Cognitive and Educational Psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4-58. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1529100612453266

Einstein, G.O., Morris, J., & Smith, S. (1985). Note-taking, Individual Differences and Memory for Lecture Information. Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(5), 522-532. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.77.5.522

Fisher, J.L., & Harris, M.B. (1973). Effect of Note Taking and Review on Recall. Journal of Educational Psychology, 65(3), 321-325. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0035640

Fried, C.B. (2008). In-class Laptop Use and its Effects on Student Learning. Computers & Education 50(3), 906-914. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2006.09.006

Hyden, P. (2005). Teaching Statistics by Taking Advantage of the Laptop’s Ubiquity. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 101, 37-42. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tl.184

Jasmin, K., & Casasanto, D. (2012). The Qwerty Effect: How Typing Shapes the Meanings of Words. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 19(3), 499-504. doi: 10.3758/s13423-012-0229-7

Kay, R., & Lauricella, S. (2011). Exploring the Benefits and Challenges of Using Laptop Computers in Higher Education Classrooms: A Formative Analysis. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 37(1), 1-18. (http://goo.gl/qh3Wjw) (2015-11-07).

Kobayashi, K. (2005). What Limits the Encoding Effect of Note-taking? A Meta-analytic Examination. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 30, 242–262. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2004.10.001

Lockhart, R.S., & Craik, F.I.M. (1990). Levels of Processing: A Retrospective Commentary on a Framework for Memory Research. Canadian Journal of Psychology, 44(1), 87-112. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0084237

Longcamp, M., Zerbato-Poudou, M.T., & Velay, J.L. (2005). The Influence of Writing Practice on Letter Recognition in Preschool Children: A Comparison between Handwriting and Typing. Acta Psychologica, 119(1), 67-79. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2004.10.019

Moin, L., Magiera, K., & Zigmond, N. (2009). Instructional Activities and Group Work in the U.S. Inclusive High School Co-taught Science Class. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 7, 677-697. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10763-008-9133-z

Mueller, P.A., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2014). The Pen is Mightier than the Keyboard. Advantages of Longhand over Laptop Note Taking. Psychological Science, 25, 1159-1168. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0956797614524581

Paschek, G. (2013). Las ventajas de escribir a mano. [Advantages of Handwriting]. Mente y Cerebro, 62, 18-21.

Rabinowitz, J.C., & Craik, F.I. (1986). Specific Enhancement Effects Associated with Word Generation. Journal of Memory and Language, 25, 226-237. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0749-596X(86)90031-8

Ragan, E.D., Jennings, S.R., Massey, J.D., & Doolittle, P.E. (2014). Unregulated Use of Laptops over Time in Large Lecture Classes. Computers & Education, 78, 78-86. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2014.05.002

Rogers, J., & Case-Smith, J. (2002). Relationships between Handwriting and Keyboarding Performance of Sixth-grade Students. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 56(1), 34-39. doi:10.5014/ajot.56.1.34

Sevillano, M.L., Quicios, M.P., & González-García, J.L. (2016). Posibilidades ubicuas del ordenador portátil: percepción de estudiantes universitarios españoles [The Ubiquitous Possibilities of the Laptop: Spanish University Students’ Perceptions]. Comunicar, 46(24), 87-95. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C46-2016-09

Smoker, T.J., Murphy, C.E., & Rockwell, A.K. (2009). Comparing Memory for Handwriting versus Typing. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 53(22), 1.744-1.747. Sage Publications. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/154193120905302218

Stefanou, C., Hoffman, L., & Vielee N. (2008). Note Taking in the College Classroom as Evidence of Generative Learning. Learning Environments Research, 11, 1-17. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10984-007-9033-0

Steimle, J., Brdiczka, O., & Mühlhäuser, M. (2009). Collaborative Paper-based Annotation of Lecture Slides. Educational Technology & Society, 12, 125-137. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2009.27

Sülzenbrück, S., Hegele, M., Rinkenauer, G., & Heuer, H. (2011). The Death of Handwriting: Secondary Effects of Frequent Computer Use on Basic Motor Skills. Journal of Motor Behavior, 43(3), 247-251. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222895.2011.571727

Treisman, A. (2014). The Psychological Reality of Levels of Processing. In L.S. Cermak & F.I. Craik (Eds.), Levels of Processing in Human Memory (pp. 301-330). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Tront, J.G. (2007). Facilitating Pedagogical Practices through a Large-scale Tablet PC Development. IEEE Computer 40(9), 62-68. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/MC.2007.310

Weaver, B.E., & Nilson, L.B. (2005). Laptops in Class: What are they good for? What can you do with them? New Directions in Teaching and Learning, 101, 3-13. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tl.181

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

La toma de apuntes es una estrategia generalizada del alumnado de Educación Superior y se ha constatado su influencia en el rendimiento académico. El uso del ordenador está desplazando al método tradicional de lápiz y papel. El presente estudio pretende arrojar luz sobre las ventajas y los inconvenientes derivados del uso de uno u otro método en la toma de apuntes en las aulas universitarias. Un total de 251 estudiantes universitarios de ciencias sociales y ciencias de la salud participaron en el estudio. Se plantearon dos condiciones experimentales: toma de notas de forma manual (n=211) y de manera electrónica (n=40). Se hallaron diferencias a favor del grupo que usó el ordenador en las tareas basadas en completar el abecedario, escribir frases y reconocer palabras anotadas previamente (p

1. Introducción

Es cada vez menos frecuente la escritura manual tradicional que el hacerlo a través de dispositivos electrónicos. El ordenador protagoniza las rutinas laborales de una gran cantidad de profesiones y, desde los inicios de la escolarización hasta la educación superior, se utilizan los instrumentos electrónicos como herramientas de aprendizaje y para fines académicos (elaboración de trabajos, estudio, intercambio de apuntes, búsqueda de información académica) (Sevillano, Quicios, & González-García, 2016). Muchas personas acostumbran a plasmar sus pensamientos tecleando en múltiples escenarios digitales (blogs, comentarios en páginas web, búsquedas en proveedores de información, mensajes en twitter, comentarios en redes sociales, etc.). De hecho, no es raro asociar el progreso y la innovación de los procedimientos de enseñanza-aprendizaje con el uso de sistemas informatizados. Parece que en algunas escuelas de Estados Unidos y de Alemania la escritura manual ya no figura en el curriculum, aprendiendo los alumnos el alfabeto tal y como aparece en un teclado de ordenador (Paschek, 2013: 19). En definitiva, los ordenadores y los teléfonos inteligentes están colaborando a que escribir a mano sea cada vez menos frecuente.

Algunos estudios han sido muy insistentes en destacar las bondades de escribir en un teclado respecto a la escritura manual (Rogers & Case-Smith, 2002). Este entusiasmo no es nuevo, sino que cuando en la historia han aparecido nuevos instrumentos tecnológicos, de una u otra forma, se han trasladado al ámbito de la educación. Así ocurrió, por ejemplo, con la ya obsoleta máquina de escribir, cuyo valor curricular fue destacado en publicaciones de la época (Conard, 1935).

Recientemente, ha surgido un renovado interés por fundamentar las ventajas o inconvenientes de la escritura manual o a través de un teclado, pero los resultados están lejos de ser concluyentes (Longcamp, Zerbato-Poudou, & Velay, 2005; Sülzenbrück, Hegele, Rinkenauer, & Heuer, 2011).

Algunos de estos trabajos se han realizado con escolares, destacando la superioridad de la escritura manual tanto en la reproducción de letras del alfabeto como en la calidad de la composición escrita (Berninger, Abbott, Augsburger, & García, 2009; Connelly, Gee, & Walsh, 2007). Incluso otros han destacado los procesos cognitivos asociados a la escritura digital, tales como la memoria de trabajo (Bui & Myerson, 2014; Smoker, Murphy, & Rockwell, 2009) o el llamado efecto «qwerty» (Jasmin & Casasanto, 2012) referido a la influencia de la posición de las letras en el teclado sobre el significado de las palabras. En realidad, lo que conocemos es que tomar notas en clase es beneficioso para facilitar el aprendizaje, y parece ser que se da una correlación positiva entre la cantidad de notas que se toman y la cantidad de información codificada durante una clase (Bui, Myerson, & Hale, 2013). Este beneficio puede explicarse por el llamado efecto generación de palabras (Rabiowitz & Craik, 1986), que indica que cuando uno reelabora la información se recuerda mejor, en comparación a cuando solo la oye o la lee. No obstante, la calidad de las notas puede ser mucho más importante que la cantidad, en consistencia con lo que nos indica el marco teórico de los niveles de procesamiento (Craik & Lockhart, 1972). La extensa literatura existente al respecto (ver meta-análisis de Kobayashi, 2005) ha estado basada fundamentalmente en estudios sobre la escritura manual. Como señalan Bui y otros (2013), es posible que la toma de apuntes en clase mediante sistemas digitales cambie el equilibrio entre cantidad y calidad, y se necesite más investigación empírica sobre sus efectos en el aprendizaje.

Actualmente, con el auge de las nuevas tecnologías, está aumentando considerablemente el número de alumnos que toman notas con un ordenador o tableta (Cassany, 2012; Weaver & Nilson, 2005), en lugar del tradicional método de lápiz y papel. Existen trabajos que respaldan el uso de los dispositivos electrónicos como medio de apoyo en las distintas estrategias de aprendizaje (Hyden, 2005; Tront, 2007). Sin embargo, otras investigaciones defienden exactamente lo contrario. Es decir que este tipo de materiales dificultan y empobrecen los resultados académicos de los alumnos (Fried, 2008; Kay & Lauricella, 2011; Ragan, Jennings, Massey, & Doolittle, 2014).

Bui y otros (2013) estudiaron a través de varios experimentos la relación existente entre el recuerdo de la información y los distintos modos o estrategias para tomar apuntes. En uno de los experimentos algunos participantes tomaban notas mediante ordenadores portátiles y otros, manualmente. Los resultados apoyaron el uso del ordenador para llevar a cabo la tarea, ya que estos, en las pruebas de recuerdo inmediato, fueron mejores para dicho grupo. El experimento concluyó que aquellas personas que utilizaban la escritura electrónica para tomar notas, apuntaron más contenido que cuando lo hicieron mediante escritura manual. Asimismo, en dicho experimento los estudiantes que tomaron nota con el ordenador recordaron más información en tareas de recuerdo libre inmediato. Recientemente, Beck (2014) trató de replicar y ampliar los resultados obtenidos por Bui y otros (2013), estudiando las diferencias existentes entre la ejecución de alumnos tanto en tareas de recuerdo inmediato como a largo plazo. Los resultados hallados por Beck (2014) difirieron considerablemente de los encontrados por Bui y otros (2013). En el experimento de Beck (2014) se constató que la escritura electrónica era una herramienta potente de registro cuantitativo de información, ya que los estudiantes universitarios que trabajaron con él anotaron significativamente más información. Sin embargo, no hubo diferencias significativas en las tareas de recuerdo inmediato ni demorado. Por el contrario, los estudiantes que trabajaban con bolígrafo y papel alcanzaron un mayor recuerdo de la información.

Esta falta de acuerdo sobre las ventajas e inconvenientes de las herramientas usadas para la escritura en diferentes campos conductuales nos ha inclinado a conocer su efecto sobre distintos procesos de aprendizaje que se producen en el ámbito de la enseñanza universitaria. En efecto, es cada vez más frecuente ver en las aulas de enseñanza superior alumnado que utiliza los ordenadores (o tabletas) como herramienta de escritura para tomar apuntes en clase, redactar trabajos de grupo, etc. Por ello, se planteó como objetivo de este trabajo, conocer en este tipo de alumnado las diferencias en la cantidad y calidad de la retención de la información en función del modo de toma de apuntes, es decir, escritura tradicional manual o escritura electrónica. En consecuencia, se pretendió analizar particularmente los efectos del modo de codificación y registro de la información sobre el recuerdo de esta, bajo el marco teórico de los niveles de procesamiento (Cermak & Craik, 2014; Lockhart & Craik, 1990), que defiende que llevar a cabo una actividad que se procese de manera superficial trae consigo un recuerdo de la información más pobre que cuando se realiza de manera más profunda. Se planteó la hipótesis de que la escritura electrónica favorece la toma de una mayor cantidad de anotaciones, ya que dicho dispositivo contribuye a una mayor velocidad de registro; sin embargo, la menor cantidad de tiempo que se dedica en este procesamiento puede ir en detrimento de la huella de memoria en la información registrada.

2. Material y métodos

2.1. Participantes

Un total de 251 alumnos de la Universidad de Cádiz, procedentes de cursos y titulaciones diferentes pertenecientes al área de ciencias sociales y ciencias de la salud (grados de psicología n=134, educación infantil n=57 y educación primaria n=60), fueron evaluados. Del total de estudiantes 54 eran hombres y 197, mujeres; cuya edad media fue de 19,2 años; sd=1.2, participando en este estudio de manera voluntaria. Todos los alumnos eran de habla castellana, el 9% eran zurdos y el resto diestros. Los participantes fueron divididos en dos grupos, aquellos que habitualmente tomaban apuntes en su ordenador personal (n=40) –condición experimental «escritura electrónica»– y los que lo hacían en papel y bolígrafo (n=211) –condición experimental «escritura manual»–. La proporción en el tamaño de los grupos y en su género, refleja la realidad sociológica de los estudiantes que acostumbran a utilizar el ordenador (o tableta) como procedimiento habitual para tomar apuntes en la universidad.

2.2. Material y procedimiento

Los participantes realizaron las tareas en grupos de aproximadamente 40 alumnos utilizando sus propios ordenadores portátiles con los que habitualmente asistían a clase, o bien papel y bolígrafo. Previamente a la realización del estudio se informaba a los estudiantes sobre su participación en un experimento de psicología, sin ofrecerles mayor explicación acerca del objetivo del estudio. Los experimentos se realizaban en horas lectivas cedidas voluntariamente por algún profesor universitario. El alumnado participaba voluntariamente en el experimento sin recibir a cambio ninguna recompensa académica por hacerlo. En todas las sesiones experimentales había al menos dos experimentadores para el control de las actividades. Las tareas administradas fueron las siguientes:

• Tarea 1. Tarea repetitiva de procesamiento superficial: Escribir el abecedario en orden alfabético manual o electrónicamente tantas veces como dé tiempo durante 30 segundos. Transcurrido el tiempo, el examinador paraba el cronómetro y decía en voz alta «se acabó el tiempo», para que todos los participantes dejaran de escribir. Para los participantes que acostumbraban a tomar apuntes tradicionalmente a mano se les facilitaba una hoja de papel en blanco. Para los estudiantes que acostumbraban a tomar apuntes en ordenador debían abrir un nuevo documento en el procesador de textos Word y después grabarlo en un archivo «.doc» que remitirían inmediatamente a una dirección de correo electrónico facilitada. La instrucción era la siguiente: «Escriban las letras del abecedario en orden alfabético tantas veces como se pueda». Se contabilizaba 1 punto por cada abecedario escrito correctamente en orden alfabético.

• Tarea 2. Tarea repetitiva de fluidez verbal: Escribir todas las frases que dé tiempo durante dos minutos mediante escritura manual o escritura electrónica. La primera de las frases debía empezar por la palabra «escribir» (para los que escribían manualmente), o por la palabra «leer» (para los que escribían electrónicamente). A los estudiantes que escribían a mano se les proporcionaba la instrucción: «Escriban tantas frases como les dé tiempo. La primera frase que empiece por la palabra escribir; las demás pueden ser cualquiera». Se contabilizó cada una de las palabras legibles, correctamente escritas y coherentes con el texto con 1 punto. Del mismo modo, se consideraron erróneas aquellas ilegibles, con faltas ortográficas o no coherentes con el texto.

• Tarea 3. Tarea de memoria: Se presentaba una lista de 35 palabras comunes en la columna izquierda de una hoja de papel o en la pantalla del ordenador facilitada en el mismo momento a todos los estudiantes. Los participantes de la condición de escritura manual debían copiarlas en la columna derecha; en la condición de escritura electrónica lo hacían igualmente a la derecha de la hoja del procesador de textos. Una vez terminada la tarea, se les recogía y se les entregaba otra tarea distractora en una hoja de papel, consistente en resolver todas las multiplicaciones de cinco cifras que les fuesen posibles durante cinco minutos. Inmediatamente después de la tarea distractora, se pedía a los participantes que escribieran en un máximo de cinco minutos todas las palabras que recordasen del listado que anteriormente habían copiado, en una hoja de papel o en el ordenador (test de memoria). A continuación, se dejaban cinco minutos de descanso e inmediatamente después se realizaba un test de reconocimiento de palabras donde en una lista de 40 palabras (35 verdaderas y 5 falsas) presentadas en una hoja de papel o en el ordenador, los participantes debían señalar cuáles eran las que se correspondían con las palabras estímulo presentadas inicialmente.

Las tareas fueron administradas en una sesión experimental de aproximadamente 40 minutos durante los cursos académicos 2013-14 y 2014-15. Las tareas 1 y 2 respondían a un formato modificado de la metodología utilizada por Berninger y otros (2009). Para el desarrollo de la tarea 3 se utilizó el método desarrollado por Smoker y otros (2009). Las sesiones fueron realizadas en las aulas universitarias donde habitualmente recibían su docencia reglada. Las condiciones de iluminación y sonido eran satisfactorias y la colaboración desinteresada del alumnado participante fue generalizada. En todas las evaluaciones se calculó la fiabilidad entre dos codificadores de las respuestas, encontrándose una media de fiabilidad del 95,8%.

3. Análisis y resultados

En primer lugar, para analizar las diferencias existentes entre los alumnos a la hora de llevar a cabo las distintas tareas propuestas se realizó un análisis de tipo descriptivo que se presenta recogido en la tabla 1.

En la tabla 1 se puede observar cómo el grupo que trabajó con el ordenador escribió un mayor número de veces el abecedario y alcanzó un mayor número de frases correctas. Asimismo, su ejecución fue mayor en la tarea de reconocimiento. Sin embargo, los resultados fueron a la inversa en el caso de la tarea de recuerdo. Los participantes de la condición «escritura manual» obtuvieron mejores resultados. Las diferencias entre ambos grupos se respaldan en los datos recogidos sobre el tamaño del efecto.

Asimismo, para estudiar si las diferencias existentes entre ambos grupos eran estadísticamente significativas se planteó un análisis de la varianza. Para ello, se estudiaron los supuestos necesarios para llevarla a cabo. Los resultados obtenidos de la prueba estadística de Kolmogorov-Smirnov (p<.05) indicaron que la muestra no se distribuía normalmente y, por tanto, no apoyaron el uso de la Anova como procedimiento para el contraste de hipótesis. En consecuencia, se optó por la prueba no paramétrica U de Mann Whitney para poder contrastar la hipótesis nula, es decir, que las diferencias entre ambos grupos en la ejecución de las distintas tareas fueron inexistentes.

Como podemos observar en la tabla 2, las diferencias entre ambas condiciones en la ejecución de algunas tareas fueron significativas. Como cabía esperar los alumnos que trabajaron con el ordenador escribieron un mayor número de veces el abecedario que aquellos que anotaron mediante escritura manual (p< .0001). Asimismo, el número de frases correctas que escribieron los alumnos fue mayor en el grupo que usó el ordenador (p<.008). Del mismo modo, el número de frases incorrectas también fue mayor para dicho grupo aunque en este caso las diferencias no fueron significativas (p>.05).

Con respecto a las tareas que implicaban a la memoria a corto plazo, es decir, la tarea de reconocimiento y recuerdo, los resultados difirieron en función de la condición en la forma en que se tomaron las notas. En primer lugar, en la tarea de reconocimiento los resultados apuntaron a favor de una mejor ejecución de los alumnos en la condición de escritura electrónica. Las diferencias fueron significativas tanto en aciertos como en errores. Los alumnos que usaron el ordenador obtuvieron un mayor número de aciertos y difirieron significativamente de los que no lo hicieron (p<.002). Al mismo tiempo los alumnos que realizaron la tarea mediante escritura manual obtuvieron un mayor número de errores arrojando una diferencia también significativa (p<.005).

En segundo lugar, en la tarea de recuerdo libre, los alumnos que habían trabajado con bolígrafo y papel obtuvieron un mejor rendimiento, ya que el número de palabras recordadas por ellos fue mayor que el de los participantes que utilizaron la escritura electrónica, siendo esta diferencia significativa (p<.021). Con respecto a los errores, los alumnos de la condición «escritura manual» obtuvieron menos errores, pero dicha diferencia no llegó a ser significativa (p>.05).

Asimismo, se realizó un análisis discriminante para establecer una diferenciación entre ambas condiciones y obtener una función capaz de clasificar a los alumnos en base a los valores obtenidos en las variables discriminadoras, como fue la ejecución en las distintas tareas empleadas en el estudio. Por tanto, esta técnica de análisis estadístico facilitó una clasificación supervisada de vectores de datos numéricos en dos categorías (en este caso, condición escritura manual y electrónica). Dicho análisis se basó en la obtención de un hiperplano frontera capaz de delimitar ambos grupos de participantes. Esta distribución se comparó con los resultados reales arrojando una matriz de clasificación donde su diagonal representaba los totales o porcentajes de los individuos bien clasificados y donde los elementos extra diagonales representaron los falsos positivos y falsos negativos del procedimiento de clasificación (tabla 3 en la página siguiente).

Según los cálculos y los resultados obtenidos del análisis discriminante, el 82,5% de los participantes pertenecientes a la condición «escritura electrónica» fueron clasificados correctamente en su grupo y un 76,3% fueron catalogados como pertenecientes a la condición «escritura manual». Como consecuencia podemos deducir que existe un patrón que conlleva una diferencia en los resultados de las tareas de recuerdo en relación con el modo de registro de la información. Al diferir el número de participantes en ambas condiciones, se concluyó que en total un 77,3% de casos agrupados originales fueron clasificados correctamente.

De manera complementaria, se llevó a cabo un contraste de igualdad de grupos basado en el estadístico Lambda de Wilks y resuelto por una aproximación Chi-cuadrado, el cual determinó el rechazo de la hipótesis de igualdad entre los grupos (Lambda de Wilks =.780; X2=60.98; p<.0001). En consecuencia, se concluyó que las diferencias en ejecución existentes entre los participantes de ambas condiciones fueron estadísticamente significativas, apoyando los resultados mostrados anteriormente.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

En este trabajo se ha analizado la forma de tomar apuntes con papel y bolígrafo o bien a ordenador en un amplio grupo de estudiantes universitarios, comparando las diferencias de ejecución y su variación en la capacidad de recuerdo inmediato. Las formas como se toman apuntes y los medios para llevarlo a cabo difieren entre los estudiantes, particularmente en esta época en la que los medios digitales son muy comunes en las aulas universitarias. Por ello, se están desarrollando estudios para conocer qué procedimientos pueden, en mayor medida, favorecer el recuerdo de la información y prestar atención al modo de codificación del contenido por parte del alumnado.

La actividad en la que el alumnado de educación superior suele ocupar la mayoría del tiempo durante las clases magistrales tradicionales es la toma de apuntes (Moin, Magiera, & Zigmond, 2009). De acuerdo con algunos estudios, esta actividad implicaría un procesamiento cognitivo y ofrecería una mayor posibilidad de recuerdo del contenido, que cuando únicamente se atiende a la información sin tomar notas (Dunlosky, Rawson, Marsh, Nathan, & Willingham, 2013). La toma de apuntes es un proceso complejo ya que en primer lugar el alumno debe atender a la explicación, seleccionar la información a plasmar y parafrasearla (Stefanou, Hoffman, & Vielee, 2008; Steimle, Brdiczka, & Mühlhäuser, 2009). Diversos procesos cognitivos de orden superior están implicados en la toma de notas, tales como la atención y la memoria. Con relación a este último aspecto parece que la toma de notas facilita el recuerdo de la información tanto cualitativa como cuantitativamente (Einstein, Morris, & Smith, 1985; Fisher & Harris, 1973), siendo una de las razones por las cuales es una actividad de estudio generalizada entre el alumnado.

Los resultados del presente experimento sugieren que la escritura electrónica es una herramienta eficiente de registro de información, en el sentido de que los estudiantes que usaban el ordenador registraron un mayor número de veces el abecedario que aquellas personas que lo hicieron manualmente, coincidiendo con el estudio de Beck (2014), donde también encuentra una mejora en el registro cuantitativo de información. Esta tarea de ejecución superficial puede verse ayudada por las nuevas tecnologías. Asimismo, a la hora de escribir frases también plasmaron un mayor número sobre el ordenador que en papel. No obstante, los resultados hallados con respecto al recuerdo discrepan significativamente de los obtenidos por Bui y otros (2013) y se encuentran en la línea de los hallados por Beck (2014), ya que en la tarea de recuerdo libre inmediato se obtuvieron mejores resultados en los estudiantes del grupo que escribió sobre papel, pero en este caso esta superioridad fue significativa. Sin embargo, hay que añadir que en la tarea de reconocimiento, los estudiantes de la condición escritura electrónica fueron superiores de manera significativa.

¿Cómo podemos explicar estos resultados? Una de las posibles vías de explicación se encontraría en el marco teórico de los niveles de procesamiento (Cermak & Craik, 2014; Craik, 2002). La realización de una tarea que implica el tratamiento de las palabras como objetos o conjuntos de letras, tal y como ocurre en la toma de notas mediante ordenador, induce a un procesamiento muy superficial que influye, en consecuencia, en el recuerdo y la codificación del contenido a recordar. Este procesamiento superficial conduciría al éxito en tareas que no requieran de una codificación profunda, tales como una tarea de reconocimiento que implique la memoria a corto plazo, apoyando los resultados obtenidos en la investigación. Sin embargo, cuando una tarea conlleva tratar las palabras como unidades semánticas, se lleva a cabo un procesamiento en niveles de análisis más profundos, haciendo más probable su recuerdo y, por tanto, obteniéndose mejores resultados en una tarea de recuerdo libre. El uso del ordenador como herramienta de toma de apuntes conlleva una ventaja inicial, por cuanto incrementa la cantidad de información registrada, como se puede observar en los resultados obtenidos de la tarea 1 y 2. No obstante, esa eficiencia es menor cuando la tarea exige una codificación más profunda. Esto parece conseguirse más eficientemente empleando el bolígrafo y el papel. El éxito del alumnado es mayor en aquellas tareas en que la recuperación de la información requiera un menor nivel de procesamiento, al contrario de lo que ocurre con la toma de notas en papel, en la que el alumno es mucho más eficiente cuando la tarea requiere una codificación más profunda (Mueller & Oppenheimer, 2014; Treisman, 2014). Cuando los inputs de información necesitan ser «traducidos» a códigos especializados, ello arrastra la formación de representaciones mnémicas más complejas. Escuchar una clase requiere un procesamiento fonológico, pero escribir las ideas escuchadas exige además su «traducción» al procesamiento ortográfico, lo cual puede beneficiar a la memoria. La ventaja de la escritura electrónica es clara en cuanto a la cantidad de notas que se pueden tomar, sin embargo, esto no se transfiere automáticamente a la calidad de la información recogida. Podemos procesar la información más profundamente cuando podemos organizarla de manera más significativa, y esto llevaría a un aprendizaje a más largo plazo (Bui & al., 2013).

Existe todavía un amplio espacio para la investigación sobre este tema. Puede que el paso de una actividad basada en la reproducción automática de letras o palabras (tareas 1 y 2 de nuestro experimento), a desarrollar frases con sentido gramatical y contenido semántico significativo (como el requerido en la toma de apuntes en educación superior), resulte más eficiente cuando se hace a mano, puesto que esta forma de anotación favorece los procesos de memoria, ya que parece que establece enlaces más complejos y estables (Smoker & al., 2009). El escritor español Rafael Sánchez-Ferlosio manifestaba que «para superar los daños que le habían causado los años de consumo abusivo de anfetaminas se dedicó a ejercicios caligráficos» (El País Semanal, 2015-10-25: 62). No hay datos que puedan confirmar esta intuición personal de nuestro genial ensayista. Sin embargo, dada la controversia actual, los educadores podrían cometer un error cuando eliminan la escritura en papel (Clayton, 2015: 65): «El que sabe escribir en papel tendrá siempre una ventaja sobre los que solo utilizan el formato digital como vía de comunicación escrita. Los avances técnicos podrían evolucionar a la inversa, y no es inconcebible que la escritura a mano sustituya a los teclados como forma de interacción con los ordenadores». En este sentido, el trabajo actual sugiere una línea de investigación conectando el medio con el que toman apuntes los estudiantes de nivel superior y la profundidad de procesamiento de la información recogida, así como la posibilidad de codificarlos de manera semántica. Podrían analizarse las diferencias existentes entre ambos modos de registro en tareas que requieran un nivel de procesamiento más profundo que la mera transcripción. Del mismo modo, sería procedente no solo evaluar las diferencias en el recuerdo de la información a corto plazo, sino también a largo plazo.

Referencias

Beck, K.M. (2014). Note Taking Effectiveness in the Modern Classroom. The Compass, 1(1). (http://goo.gl/7k4TOj) (2015-09-05).

Berninger, V.W., Abbott, R.D., Augsburger, A., & Garcia, N. (2009). Comparison of Pen and Keyboard Transcription Modes in Children with and without Learning Disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 32, 123-141. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/27740364

Bui, D.C., & Myerson, J. (2014). The Role of Working Memory Abilities in Lecture Note-taking. Learning and Individual Differences, 33, 12-22. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2014.05.002

Bui, D.C., Myerson, J., & Hale, S. (2013). Note-taking with Computers: Exploring Alternative Strategies for Improved Recall. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(2), 299-309. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0030367

Cassany, D. (2012). En línea. Leer y escribir en la Red. [On line. Reading and Writing on the Web]. Barcelona: Anagrama.

Cermak, L.S., & Craik, F.I. (2014). Levels of Processing in Human Memory (PLE: Memory) (Vol. 5). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Clayton, E. (2015). La historia de la escritura. [The History of Writing]. Madrid: Siruela.

Conard, E.U. (1935). A Study of the Influence of Manuscript Writing and of Typewriting on Children’s Development. The Journal of Educational Research, 29(4), 254-265. doi: 10.1080/00220671.1935.10880582

Connelly, V., Gee, D., & Walsh, E. (2007). A Comparison of Keyboarded and Handwritten Compositions and the Relationship with Transcription Speed. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(2), 479-492. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/000709906X116768

Craik, F. I. M. & Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of Processing: A Framework for Memory Research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11, 671- 684. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5371(72)80001-X

Craik, F.I. (2002). Levels of Processing: Past, Present... and Future? Memory, 10(5-6), 305-318. doi: http://dx.doi.org/0.1080/096582102440001

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K.A., Marsh, E.J., Nathan, M.J., & Willingham, D.T. (2013). Improving Students’ Learning with Effective Learning Techniques: Promising Directions from Cognitive and Educational Psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4-58. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1529100612453266

Einstein, G.O., Morris, J., & Smith, S. (1985). Note-taking, Individual Differences and Memory for Lecture Information. Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(5), 522-532. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.77.5.522

Fisher, J.L., & Harris, M.B. (1973). Effect of Note Taking and Review on Recall. Journal of Educational Psychology, 65(3), 321-325. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0035640

Fried, C.B. (2008). In-class Laptop Use and its Effects on Student Learning. Computers & Education 50(3), 906-914. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2006.09.006

Hyden, P. (2005). Teaching Statistics by Taking Advantage of the Laptop’s Ubiquity. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 101, 37-42. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tl.184

Jasmin, K., & Casasanto, D. (2012). The Qwerty Effect: How Typing Shapes the Meanings of Words. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 19(3), 499-504. doi: 10.3758/s13423-012-0229-7

Kay, R., & Lauricella, S. (2011). Exploring the Benefits and Challenges of Using Laptop Computers in Higher Education Classrooms: A Formative Analysis. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, 37(1), 1-18. (http://goo.gl/qh3Wjw) (2015-11-07).

Kobayashi, K. (2005). What Limits the Encoding Effect of Note-taking? A Meta-analytic Examination. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 30, 242–262. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2004.10.001

Lockhart, R.S., & Craik, F.I.M. (1990). Levels of Processing: A Retrospective Commentary on a Framework for Memory Research. Canadian Journal of Psychology, 44(1), 87-112. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0084237

Longcamp, M., Zerbato-Poudou, M.T., & Velay, J.L. (2005). The Influence of Writing Practice on Letter Recognition in Preschool Children: A Comparison between Handwriting and Typing. Acta Psychologica, 119(1), 67-79. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2004.10.019

Moin, L., Magiera, K., & Zigmond, N. (2009). Instructional Activities and Group Work in the U.S. Inclusive High School Co-taught Science Class. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 7, 677-697. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10763-008-9133-z

Mueller, P.A., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2014). The Pen is Mightier than the Keyboard. Advantages of Longhand over Laptop Note Taking. Psychological Science, 25, 1159-1168. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0956797614524581

Paschek, G. (2013). Las ventajas de escribir a mano. [Advantages of Handwriting]. Mente y Cerebro, 62, 18-21.

Rabinowitz, J.C., & Craik, F.I. (1986). Specific Enhancement Effects Associated with Word Generation. Journal of Memory and Language, 25, 226-237. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0749-596X(86)90031-8

Ragan, E.D., Jennings, S.R., Massey, J.D., & Doolittle, P.E. (2014). Unregulated Use of Laptops over Time in Large Lecture Classes. Computers & Education, 78, 78-86. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2014.05.002

Rogers, J., & Case-Smith, J. (2002). Relationships between Handwriting and Keyboarding Performance of Sixth-grade Students. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 56(1), 34-39. doi:10.5014/ajot.56.1.34

Sevillano, M.L., Quicios, M.P., & González-García, J.L. (2016). Posibilidades ubicuas del ordenador portátil: percepción de estudiantes universitarios españoles [The Ubiquitous Possibilities of the Laptop: Spanish University Students’ Perceptions]. Comunicar, 46(24), 87-95. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C46-2016-09

Smoker, T.J., Murphy, C.E., & Rockwell, A.K. (2009). Comparing Memory for Handwriting versus Typing. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 53(22), 1.744-1.747. Sage Publications. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/154193120905302218

Stefanou, C., Hoffman, L., & Vielee N. (2008). Note Taking in the College Classroom as Evidence of Generative Learning. Learning Environments Research, 11, 1-17. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10984-007-9033-0

Steimle, J., Brdiczka, O., & Mühlhäuser, M. (2009). Collaborative Paper-based Annotation of Lecture Slides. Educational Technology & Society, 12, 125-137. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2009.27

Sülzenbrück, S., Hegele, M., Rinkenauer, G., & Heuer, H. (2011). The Death of Handwriting: Secondary Effects of Frequent Computer Use on Basic Motor Skills. Journal of Motor Behavior, 43(3), 247-251. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222895.2011.571727

Treisman, A. (2014). The Psychological Reality of Levels of Processing. In L.S. Cermak & F.I. Craik (Eds.), Levels of Processing in Human Memory (pp. 301-330). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Tront, J.G. (2007). Facilitating Pedagogical Practices through a Large-scale Tablet PC Development. IEEE Computer 40(9), 62-68. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/MC.2007.310

Weaver, B.E., & Nilson, L.B. (2005). Laptops in Class: What are they good for? What can you do with them? New Directions in Teaching and Learning, 101, 3-13. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tl.181

Document information

Published on 30/06/16

Accepted on 30/06/16

Submitted on 30/06/16

Volume 24, Issue 2, 2016

DOI: 10.3916/C48-2016-10

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?