ABSTRACT

In the 21st century, the international community has assumed the responsibility of protecting individuals and groups from unlawful human rights abuse. This article analyzes the political tensions faced by domestic courts when they attempt to enforce international human rights norms. After presenting divergent models, it analyzes how multilateral norms relate to both the nations domestic law and its foreign policy. It then examines two models of human rights enforcement, followed by a comparison of the Mexican and U.S. models. This comparison shows that although both countries presented different approaches (one from within, USA; and one from the outside, Mexico) both of them enforce the norm of international responsibility to protect.

RESUMEN

Hoy los derechos humanos son una política global sustentada en la responsabilidad de la comunidad internacional de proteger a personas y grupos de abusos. Una de las políticas para hacerla efectiva ha sido el legal enforcement. Este artículo analiza las tensiones políticas que enfrentan los poderes judiciales domésticos cuando asumen la responsabilidad de proteger derechos humanos en la medida en que los ubica como actores no sólo de la política doméstica sino también de la internacional. Poniendo el énfasis en diferentes líneas de política judicial que pueden tener lugar, en primer término se analizan los vínculos entre las diferentes jurisdicciones legales de derechos humanos mostrando la importancia estratégica de los poderes judiciales domésticos y en segundo lugar se analizan dos modelos de legal enforcement de derechos humanos el de México y el de Estados Unido de los que se sostiene que si bien son diferentes constituyen formas de hacer efectiva la regla de la responsabilidad internacional de protección una desde adentro y otra desde afuera respectivamente, evidenciando las tensiones políticas que deben enfrentar en estos escenarios.

Keywords

Legal enforcement of human rights ; Human rights politics ; Domestic judiciaries ; Mexico ; U.S.A.

Palabras clave

Aplicación de normas legales de derechos humanos ; Política de Derechos Humanos ; Poderes judiciales ; México ; Estado Unidos de Norteamérica

I. INTRODUCTION

It is common to hear people discuss a “human rights revolution”. In practical terms, this refers to the adoption by domestic institutions of human rights standards that have already been developed by foreign governments, international agencies and organizations.1 This article will focus on diverse human rights enforcement models, with special emphasis on two cases: Mexico and the United States. Its main goal is to analyze the underlying tensions between international norms and domestic judicial institutions and legal doctrines, and the scope of each branch of the government.

The relation between international and domestic jurisdictions in regard to human rights legal enforcement has received special attention in the literature about diffusion of human rights norms2 . Both domestic and international courts have became key actors in this scenario.3 This article argues that even when there is an accepted social norm 4 behind human rights regimes today: that the international community cannot accept human rights abuses at the domestic level (even when this situation can fluctuate from one moment to another); this norm is known as the international responsibility to protect (United Nations, A/63/677); there has been no international consensus with regard the models of human rights legal enforcement at the domestic level.

The norm of the international responsibility to protect is as the same time the one that expresses the maximal aspiration of the contemporary human rights global community as well as the one that became especially problematic in the arena of domestic judicial politics5 . In other words, the adoption of human rights by domestic judicial decision-making is not merely the result of domestic politics but also a consequence of each States foreign policy that judges need take into account in their rulings concerning these topics and their legal doctrines regarding international law.6 As such, it presents a host of unprecedented problems and opportunities.

One of the sources of the human rights as transnational policy7 is the impulse of different models of legal enforcement8 . This article proposes that each model faces unique challenges regarding both national sovereignty and international influence in domestic affairs. Judges on both multinational and domestic tribunals confront this inherent tension between national and international interests on a daily basis9 . However the main focuses of this article are the domestic judiciaries, specifically the path they assume about the international responsibility to protect.10

This article intends to: a) systematize different ways of human rights legal enforcement11 from the point of view of judicial institutions; and b) show the dilemmas faced by domestic courts regarding human rights legal enforcement.

To better understand these enforcement models, the article first analyzes diverse jurisdictions and their corresponding legal institutions, all of which are based upon domestic courts that apply human rights norms that have either been enacted and/or adjudicated by multinational bodies. Second, focusing at the domestic level, the article evaluates two contrasting human rights legal enforcement models used by Mexican and U.S. federal courts. The Mexican one will be called human rights from the outside, and the USA one will be called human rights from within. Although both nations are active in the international human rights community12 (e.g., the Inter-American System of Human Rights) the United States applies a “dual approach to International Human Rights Law”13 by using a domestic model in U.S. territory and applying different standards for other nations, meanwhile Mexico has been increasingly under international scrutiny with regard to human rights abuses. These models are closely linked to (a) the host countrys foreign policy regarding human rights; (b) domestic legal doctrine about human rights adjudication and international law; (c) the decision-making authority of each nations federal courts. Third part of the article presents some final remarks.

II. HUMAN RIGHTS ENFORCEMENT. JURISDICTIONS AND LEGAL INSTITUTIONS

After World War II, the international community established standards for both human rights abuse and crimes against humanity, and these norms included diverse enforcement mechanisms implemented at national, regional and international levels. But it was until the end of the Cold War that the effectiveness of these enforcement mechanisms became an issue for the international community14 . In other words, human rights took the form of standards adopted by the international community15 and gradually evolved to the point of becoming enforceable. Enforcement became feasible in many cases through judicial decision making by regional courts, international ad hoc tribunals, international courts or domestic judiciaries.

As standards for human rights enforcement became more widespread, disputes arose at both domestic16 and international and regional levels regarding the scope of protection available in sovereign nation-states.17 Unsurprisingly, many observers regard legal enforcement as a key to human rights protection.18

Enforcement mechanisms were developed in a wide range of jurisdictions and entities ranging from multilateral tribunals to domestic courts. As a result, national debates often involved questions concerning the legitimacy of international legal norms in domestic courts;19 as well as the legal and political issues faced by local courts in enforcing laws or rulings enacted or adjudicated elsewhere.20 This article focuses on the tensions and challenges faced by domestic courts regarding human rights enforcement.

For this reason, the “legal enforcement of human rights” refers not only to international tribunals (e.g., Rwanda and ex Yugoslavia) and regional bodies (e.g., European Court of Human Rights or the Inter-American Court of Human Rights) but also to domestic judiciaries.

In effect, human rights accountability and enforcement take into account different jurisdictions and legal institution that use different mechanism to achieve their goals. For example the enforcement can come from International, regional or domestic jurisdictions through international, regional or individual courts that can prosecute individuals or States.

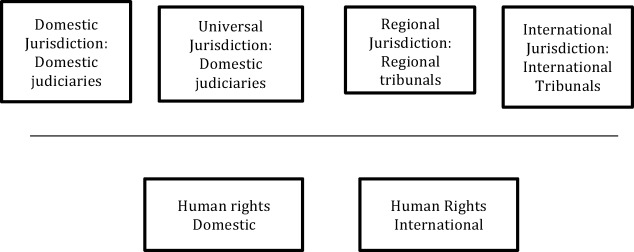

The first step in this article is to present the diverse jurisdictions and legal institutions involved in human rights enforcement. These jurisdictions and legal institutions are schematized as a continuum from foreign to domestic levels regarding their origin and scope of their rulings. Graph 2 places these jurisdictions and judicial institutions related to these on the continuum.

Graph 2.

Jurisdictions for human rights enforcement.

Although every jurisdiction can legally enforce human rights issues and humanitarian law, they differ in their relation to the national government. In the human rights domestic side (to the extreme left), “domestic jurisdiction” refers to the standing of local courts to enforce laws imposed on its own citizens. A good example of this are the prosecutions against human rights violations perpetrated by the military dictatorships of Argentina21 and Chile.22 The main actors in these procedures are domestic courts enforcing both national and international human rights law.23 In human rights international side (to the extreme right), “international jurisdiction” refers to the standing of international or multilateral courts to prosecute crimes against humanity or human rights abuses of citizens of different States in accordance with international norms. A good example of the latter are the rulings of the International Criminal Court (ICC).

Between these two extremes are mixed combinations between “the domestic” and “the international” jurisdictions; the two cases analyzed in the next section exemplify this mix.

“Universal jurisdiction” refers to the ability of one domestic judiciary to sue citizens of other States for human rights abuses “of such gravity that affect the interest of the international community as a whole”.24 Regional jurisdiction, on the other hand, describes the ability of multilateral judicial institutions to enforce human rights norms prosecuting member States of the System (not individuals). Three judicial institutions of this kind currently exist: (a) European Court of Human Rights; (b) Inter-American Court of Human Rights; and (c) African Court of Human Rights. 25

It is also important to mention that every jurisdiction is linked with judicial institutions. The domestic one with the judiciaries of each country; the universal jurisdiction with the domestic judiciaries of countries different of the perpetrator of human rights abuses or even of the victim of crimes against humanity; regional jurisdictions with regional tribunals and international jurisdiction with current or special international tribunals.

It is worth noting that even when different domestic and not domestic judicial institutions enforce human rights in the same case, this relationship is ruled by principles of concurrency, complementary and/or subsidiarity26 between domestic, regional or international courts. At the center of this complex network of jurisdictions and judicial institutions are local courts.

Table 1 bellow illustrates some of the main features of each jurisdiction for the enforcement of human rights norms: their scope; main characteristics; types of processes allowed; adjudicants standing; victims’ rights to litigate, etc. For reasons of space, and of the goal of this article, related to regional jurisdiction solely the Inter-American System of Human Rights shall be analyzed as regional jurisdiction as both nations are active members. For international jurisdiction, the focus will be on the ICC.

| Jurisdictions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic Jurisdiction | Universal Jurisdiction | Regional Jurisdiction | International Jurisdiction | |

| Judicial Institutions | Domestic courts (Judiciary) | Domestic courts in the name of the “Law of the Nations” | Interamercian Court of Human Rights | International Tribunals: International Criminal Court International Tribunal for the Ex Yugoslavia International Tribunal for Rwanda |

| Special tribunals organized for the UN as an answer to a States request: | ||||

| Special Court for Sierra Leone Special Tribunal for Lebanon. | ||||

| Who can be put on trial | Individuals | Individuals | State | Individuals |

| How can be the perpetrators put on trial (Types of enforcement for perpetrators) | Criminal procedure | Criminal procedure | State responsibility for Human rights abuses. | International criminal procedure |

| Civil procedure | Civil procedure | |||

| How can the victims participate on trials | Private prosecution | Private prosecution | Litigation (part of the case) | Private prosecution (ICC) |

| Civil action | Civil action | |||

| Type of remedies for victims | Reparations | Reparations | Reparations | Reparations |

| Other types of enforcement | International Human Rights Legal measures Administrative measures Pedagogic measures | |||

| Juridical legitimacy in the case | Prosecutor | Prosecutor | Inter-American Commission of Human Rights | Prosecutor |

| Private prosecution (victims’ participation) | Private prosecution (victims’ participation) | Private Prosecution (victims’ participation and legal representation) | ||

| Defense (public or private | Defense (public or private | Defense (public or private | ||

| Relationship between domestic, regional and international courts. | Complementarity with other courts and international institutions | Subsidiarity | Subsidiarity and complementarity, concurrency with other courts | |

| Citizenship of the accused | Citizen | Non citizen | Only State accountability | Individuals (ICC) |

| Citizens of the object states of the Tribunals | ||||

Source: Author elaboration based in legal documents.

In the table above, we can see that there are (a) diverse sources for each jurisdiction; (b) several ways for victims of human rights abuses to participate in the procedures; and (c) diverse links between international legal institutions and domestic judiciaries (subsidiarity, complementarity or concurrency). In every case, domestic courts play a fundamental role, either as main actors or as secondary actors (that failed to properly adjudicate the alleged abuse). Although human rights enforcement begins in local courts, they do not necessarily end there, as foreign or multinational judicial institutions, agencies and bodies may also be actively involved.

As we can see, there are many avenues to human rights enforcement that combine domestic and not domestic institutions and jurisdictions. To better understand these relationships here is proposed that it is necessary to study of the politics of the domestic judiciaries into their concrete contexts of human rights politics27 . This approach will be called: judicial politics of human rights.

Although multiple legal institutions and jurisdictions are often involved in the legal enforcement of human rights, the study of the relationships between them does not adequately explain their decision making process. 28 In other words, to better understand the process we need to take into account the dilemmas that judges and justices face adjudicating inside the context of real human rights politics of legal enforcement characterized (as was already pointed) for the links between of multiple jurisdictions of legal enforcement. We call this approach: judicial politics of human rights.

As the next section explains, judges must face three dilemmas in this process: a) take a “sovereigntist” or “cosmopolitan” legal approach related with their legal ideology; b) maintain the separation of powers between the executive and legislative branches or promote the concept of “multilateral justice”; or c) maintain the territoriality of their rulings or develop an extraterritoriality doctrine.

In the next section, human rights enforcement models incorporated by the federal judiciaries in both Mexico and the U.S. over the last ten years are analyzed with respect to the three issues above. While the Mexican judiciary has transitioned to a model of legal enforcement “from the outside”, the U.S. judiciary continues to enforce human rights “from within”.

III. TWO HUMAN RIGHTS ENFORCEMENT MODELS: MEXICO AND THE U.S.A.

Mexico and the United States are similar regarding some aspects of human rights politics and political institutional frameworks: both nations are active members of the international community (e.g., members of the UN Human Rights Counsel) and the Inter-American System (with representatives in the Inter-American Commission, and a Mexican citizen as judge of the Inter-American Court).

Both nations are presidential democracies with bicameral congresses and federal judiciaries headed by a Supreme Court. The federal courts in both nations have significant autonomy from the executive and legislative; and both have constitutional review powers.

Despite these similarities, however, domestic judiciaries are organizationally distinct with regard to human rights legal enforcement. While the Mexican federal judiciary is centered on the Supreme Court,29 the U.S. federal judiciary is more decentralized, with a Supreme Court that has the final word in cases originating in local district courts.

While Mexico has permitted international scrutiny of human rights enforcement since 1998 – including the contentious jurisdiction of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights – the U.S. maintains a dual approach regarding human rights law: active promotion on an international level, but not active to apply these same multilateral norms domestically.

These two path constitute the context of human rights politics of legal enforcement in which the judiciaries of each country are embedded into. While in Mexico we can see a trajectory of gradual acceptation of international human rights norms and multilateral bodies as part of the juridical system; in the United States while the State Department embraced multilateral human rights treaties and bodies, the senate do not ratify them on many cases and as a result some federal judges embrace the norm of the responsibility to protect through domestic statutes.

For a good indication of how much the two countries differed with respect to acceptance of international human rights treaties, see Table 2 below.

| Treaties | Mexico | U.S. |

|---|---|---|

| Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (1998) | Ratified | Signatory |

| Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (in force 3 May 2008) | Ratified | Signatory |

| International Convention for the Protection of all Persons from Enforced Disappearance (in force 23 December 2010). | Ratified | Non Signatory |

| International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (in force 1 July 2003) | Ratified | Non Signatory |

| Convention Against Torture, and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (in force 26 June 1987). | Ratified | Ratified |

| Convention on the Rights of the Child (in force 2 September 1990) | Ratified | Signatory |

| Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination (in force 4 January 1969) | Ratified | Ratified |

| International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (CCPR) (in force 23 March 1976) | Ratified | Ratified |

| International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights | Ratified | Signatory |

| Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (in force 3 September 1981) | Ratified | Signatory |

| Ratification rate | 100% | 30% |

Source: Human rights Atlas (http://www.humanrightsatlas.org/atlas/ )

In Table 3 , it is possible to see a similar, even clearer trend regarding adherence to Inter-American human rights treaties.

| Mexico | U.S. | |

|---|---|---|

| American Convention on Human Rights (1968) | Ratified | Signatory |

| San Salvador Protocol | Ratified | Non Signatory |

| Inter-American Convention About forced disappearences of persons | Ratified | Non Signatory |

| Interamerican Convention on prevention and sanction torture | Ratified | Non Signatory |

| Inter-American Convention for the ellimination of all forms of discrimination against persons with disabilities | Ratified | Non Signatory |

| Inter-American Convention to prevent, sanction and eradicate all forms of violence against woman | Ratified | Non Signatory |

| Ratification Rate | 100% | 14% |

Source: Elaboration based on American States Organization Records (http://www.oas.org/es/sla/ddi/tratados_multilaterales_interamericanos_firmas_mater ia.asp )

The next sections first explore general trends in both countries, and then analyze the main features of the judicial politics of human rights enforcement in each one.

1. Mexico from legal sovereigntism to legal cosmopolitanism

The Mexican judiciarys relationship to international human rights law changed from “legal sovereigntism” to contested “legal cosmopolitanism”. The turning point came when the Mexican Supreme Court of Justice ratified a ruling by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights against Mexico in the Rosendo Radilla case in 2009.30

The importance of this case can be more fully appreciated by placing it in the context of Mexican human rights policies in general.

Most academics agree that in 1994, after the public emergence of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation in the state of Chiapas, Mexican human rights policies abruptly shifted in both foreign and domestic affairs.31 For the first time, the nation opened itself to international scrutiny on human rights issues; while simultaneously, human rights abuses started to be seen as a domestic problem. Examples of this change include the creation of the National Commission of Human Rights in 1990, and its constitutional recognition as an autonomous body in 1999.32

Another major change occured in 2000, when the Revolutionary Institutional Party (“PRI” for its Spanish-language acronym) – which had held power for over seventy years – lost the presidential election. The new president, Vicente Fox Quesada, decided both to open the countrys human rights policies to external scrutiny and actively participate in international human rights forums.

At the same time, human rights issues took on greater importance in domestic policy. Notable changes included the creation of a Human Rights office in the Ministry of the Interior (Secretaría de Gobernación ); and a National Human Rights Program approved in 2004 which promoted the inclusion of human rights approach in domestic policies. 33

Despite these efforts, however, human rights advocacy also suffered notable defeats, including the cancelation of the National Human Rights Program in 2006.34 A Constitutional Reform on human rights was not approved until 2011 – more than a decade after political change.

In 2006, when Felipe Calderons administration came to office, the federal governments priority changed from human rights to national security. During this time, human rights violations increased notably.

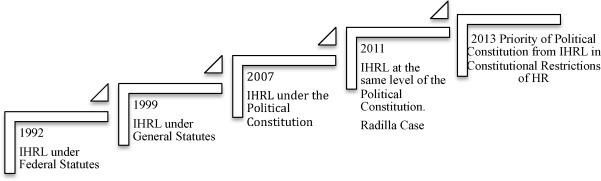

Given the Mexican governments recognition of human rights as a key component of both domestic and international affairs – at least rhetorically – the federal judiciary began to adapt domestic human rights enforcement through gradual changes in its interpretation of the hierarchy of international law. This evolution can be observed in the time line shown below (Graph 2 ).

Graph 2.

Process of change in the Mexican Supreme Courts Interpretation of the Hierarchy of International Human Rights Law (IHRL).

As we can see, the acceptance process for international human rights law took place incrementally over the course of twenty years. This occurred despite current disputes between judges who espouse either “legal sovereigntist” or “legal cosmopolitanist” views. As noted above, the turning point occured when the Supreme Court affirmed the Inter-American Human Rights Court ruling in the Rosendo Radilla case.35

The next section analyzes how the Mexican judiciary regards the hierarchy of International Human Rights Law in the turning point in this process the Rosendo Radilla Vs Mexico case..

2. The Mexican Federal Judiciary and the Rosendo Radilla Case

Rosendo Radilla Pacheco was a peasant from the State of Guerrero who was “forcibly disappeared” in 1974. Since that time, he has yet to be found. The disappearance occurred while he was traveling on a bus that was stopped by members of the Mexican Army, who detained him because he had allegedly composed “corridos” (songs) against the Army.36

As a result of his disappearance, the victims family filed several lawsuits in Mexican court. The first, filed in 1992, was dismissed for lack of evidence. In 2001, Tita Radilla, the victims daughter, joined with the Association of Relatives of Disappeared People37 and the Mexican Commission for the Defense and Promotion of Human Rights38 to file a complaint before the Inter-American Human Rights Commission. The Commissions report, issued in 2005 and left unanswered by the Mexican government, elevated the case to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which ruled against Mexico on November 23, 2009.39

It is worth mentioning that three additional suits followed this ruling: Rosendo Cantu (ICHR, 2010);40 Fernández Ortega (ICHR, 2010);41 and Cabrera García and Montiel Flores (better known as Campesinos Ecologistas “peasant ecologists”) (ICHR, 2010). 42 In each case, the Inter-American Court noted the human rights violations suffered by the victims; a lack of due diligence used in the investigations; and the inappropriate application of military justice to civilian abuses.

The following sections examine the Radilla case, which constituted a turning point in the Mexican Supreme Courts transition to a model of “human rights from the outside”.

In the Radilla ruling, the Inter-American Court held the Mexican government liable for violating the victims rights to liberty, personal integrity, legal standing; physical and mental integrity; and judicial guarantees and protection for his family. The tribunal also held that the military court where the case had been tried failed to respect due process standards established under international law; in particular, the American Convention of Human Rights.43

The ruling also required that the Inter-American Court monitor the Mexican governments follow up, including submission within one year of a progress report regarding its compliance with the sentence.

Regarding this article main goal is important to mention a request made by the President of the Supreme Court oriented to discuss (as a body) the implications for the judiciary of the Inter-American Court ruling in Radilla Pacheco v. Mexican United States (Suprema Corte de Justicia, Exp. 489/2010). 44 This request marked a radical change in the way the Supreme Court dealt with Inter-American System of Human Rights decisions; even though the Radilla Pacheco ruling was addressed generically to the Mexican State, the Supreme Court as the head of the federal judiciary began deliberations oriented to define the scope and limits of its duties and responsibilities regarding the Inter-American Courts rulings at the domestic level.

Based on this consultation, the Supreme Court decided, by a majority of 8 votes, that despite not having received express notice by the Executive about their duty to comply with the judgment, they would fulfill their obligation without coordination with other branches of the Mexican government (Suprema Corte de Justicia, Exp 489/2010).45 They also ordered compliance with the entire sentence (not only those that applied to the judiciary). In effect, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of legal cosmopolitanism (at least with respect to rulings by the Inter-American Court).

From this case, the Mexican Supreme Court began to analyze how to articulate their relationship with the Inter-American System of Human Rights given the qualifications made for the Mexican State to the jurisdiction of the Inter-American Court, the reservations against the American Convention on Human Rights and the American Convention on Forced Disappearance of Persons, as well as the interpretative declarations made related to these, and other obligations pursuant to this ruling46 .

The Mexican Supreme Court deliberated about (a) the relation between domestic legislation and international human rights law; and (b) the relation between domestic lower courts and their international counterparts.

From the point of view of the judicial politics of human rights legal enforcement, regarding the relationship between domestic legislation and international human rights law the Mexican judiciary faced a dilemma between “legal sovereigntism” and “legal cosmopolitan” doctrinal approaches in which it seemed to choose the latter, paving the way for the judiciary to operate as key actor for the diffusion of international human rights standards. This is especially noteworthy considering that this interpretation was, and still remains, bitterly contested in the same Supreme Court.47 On the other hand, regarding the relation between domestic lower courts and their international counterparts, the doctrinaire changes thus marked a new approach by the Supreme Court oriented to adapt and define a “legitimate path” to embrace International Human Rights Law at the domestic level. A good example of this trend is the permission allowed to the lower courts to make “diffuse conventionality review”48 changing the hierarchical organization of the judiciary on constitutional decision-making.

The Mexican judiciary now faces legal challenges regarding its new-found “cosmopolitanist” human rights approach.49 It is clear that this is a transitionary phase, and that the current Supreme Court has a final word on the process yet.

Before the Radilla ruling, the prevalence of a sovereigntist legal approach that prioritizes domestic law was evident, despite the fact that Mexico had already ratified numerous multinational treaties. One prominent example is that in the early 2000s in response to human rights violations during the “Dirty War” against leftist opposition in the 1970’ the Supreme Court referred the Enforced Disappearance Act enacted as part of the Federal Criminal Code without any reference to the American Convention on Forced Disappearances of Persons that had already been ratified by Mexico50 .

After Radilla case, rulings by Mexican federal courts were characterized by a delicate balance between enforcement of domestic legislation and Supreme Court precedents and compliance of international law. It is worth noting that this trend was already observed even before the Constitutional Reform on Human Rights issues was enacted on June 2011, as shown in Graph 2 .

This reform basically positioned international human rights norms at the same level as the Mexican Constitution. The clearest example of this shift was the already- mentioned consultation requested by the Supreme Court President regarding the Radilla decision. In effect, the change in domestic law was preceded by a change in the Supreme Courts entire approach to international human rights standards.

The most telling evidence of this change appeared in Supreme Court ruling 912/2011, in which it proposed a shift both in its external relations with the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and domestic relations with judges and magistrates of lower courts.

It recast its relationship with the Inter-American Court by accepting all rulings against Mexico by the Court of Human Rights as mandatory and viewing the Courts jurisprudence as optional guidance for the judiciary. (Suprema Corte de Justicia, Acuerdo Expediente 912/2010).51

Domestically, the Supreme Court held that the Radilla ruling produced different types of challenges at administrative and judicial levels. These challenges are: a) the lower level courts’ ability to use international human rights law as precedent; and b) the scope of military jurisdiction. In relation to the former, it held (by a vote of 7 to 11 votes) that all federal and local judicial entities could make a “conventionality” review of domestic law using as a benchmark the American Convention of Human Rights (which implies to make inapplicable the statutes inconsistent with the American Convention on Human Rights).

In regard to the latter, the Court excluded the application of military law in human rights cases, stating that all courts in the country should interpret Article 13 of the Constitution (which establishes military jurisdiction) as well as Art. 57 of the Code of Military Justice, in line with the American Convention on Human Rights. This interpretation will become a major legal benchmark.52

As a result of the changes in the model of human rights legal enforcement e, the Mexican Supreme Court faced two dilemmas regarding the international responsibility to protect norm: (a) the tension between domestic enforcement (i.e., sovereignty) and supra-national interpretation; and (b) a separation of powers doctrine that favored multilateral norms over national sovereignty that has a lot of domestic resistance.

The following section analyzes the U.S. model.

3. The United States: Human rights from the inside

The relationship of the Supreme Court of the United States (referred to hereinafter as “SCOTUS”) regarding the norm of the international responsibility to protect in human rights issues y can be defined as a model of “human rights from within”. Most SCOTS justices – for ideological reasons – view reliance on foreign and international law as a weakening of both democratic sovereignty and judicial accountability. For this reason, it applies domestic law to domestic issues and domestic law to international human rights issues but pursuant to the “Law of the Nations53 ”.

The enforcement of human rights as global policy is unfeasible without the active participation of the United States, both for better and for worse. The SCOTUS rulings on this topic are immerse in the context of the nations policies and politics (both foreign and domestic) on human rights issues.

As noted above, a tension exists between domestic and international application of U.S. human rights policy. While internationalists advocate the incorporation of multilateral norms and treaties into domestic law, sovereigntists place national sovereignty over international cooperation.54 While the U.S. played a leading role in the enactment of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, its role during the Cold War showed little commitment to these norms.55 The sole exception was the Carter administration, which elevated human rights to a major international cause, especially in Latin America.

After the end of the Cold War, the nations foreign policy changed but its dual approach to human rights continued, probably as a result of the Senates reluctance to ratify human rights treaties. This situation worsened after 9/11, when national security became the nations top priority.

Even when the human rights movement in the U.S. worked to “Bring Human Rights Home” (incorporate international human rights standards in domestic law)56 this initiative has never been strong enough to change the status quo. As noted above, many if not most American jurists (certainly a majority of SCOTUS justices) tend to view the incorporation of international law into American jurisprudence as a weakening of both democratic sovereignty and judicial accountability.57 As Justice Antonin Scalia commented: “The basic premise that American law should conform to the laws of the rest of the world ought to be rejected out of hand.” Seeing this as an all or nothing equation, Justice Scalia drove to a reductio ad absurdum : “The Court should either profess its willingness to reconsider all matters in the light of views of foreigners, or else it should cease putting forth foreigners’ views as part of the reasoned basis of its decisions. To invoke alien law when it agrees with ones own thinking, and ignore it otherwise, is not reasoned decision making, but sophistry.”(Roper Vs Simmons , 112 S.W 3.d 397, affirmed (2005))

As a result of this judicial doctrine, domestic U.S. human rights enforcement has never been as open to outside scrutiny as in other countries.

Through litigation based on domestic law (mostly the Alien Tort Statute), the federal courts recognized and the Supreme Court confirmed certain international norms to repair alien human rights victims from their abuses in countries different to the US. This “human rights from the inside” approach has been subsequently contested, as analyzed in the next section.

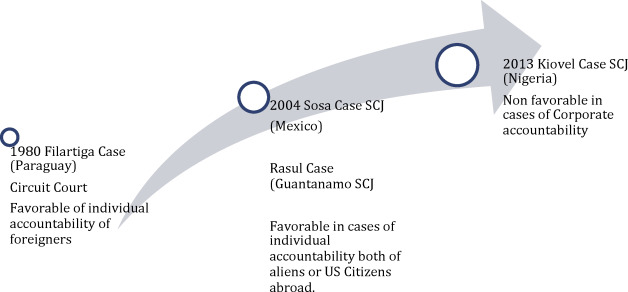

The use of the Alien Tort Statute (referred to hereinafter as the “ATS”) to establish civil liability for human rights abuses committed abroad USA was a turning point in the recognition of the international responsibility to protect. ATS was used for the first time as a human rights tool in Filartiga v. Peña Irala58 and then in many cases as Kiovel v. Dutch Petroleum59 . The graph below shows some important milestones in the use of the ATS by the Supreme Court.

Graph 3.

Judicial rulings regarding human rights abuses in the United States.

4. The inside model

The U.S. judiciarys rulings in these matters exemplify the model “human rights from within legal enforcement” approach. The U.S. courts took into account the “Law of the Nations”60 in a contemporary context, as recognition of international responsibility to protect human rights norm but based on domestic law: 1789 ATS (28 U.S.C. § 1350).

In effect, the application of this statute represents a choice between domestic and universal jurisdiction, allowing the judiciary of USA to sue a citizen of another State linked with61 or living in the USA for grievances against humanity or human rights, based in the recognition of the norm of the international responsibility to protect.

In the latter part of the twentieth century, as many commentators have noted, many courts began citing the ATS as a source of human rights law.62 The turning point was Filartiga v. Peña Irala63 (1980) during the Carter administration.

This case involved Dolly and Joel Filartiga, children of a Paraguayan doctor living in Paraguay who served poor patients and was an outspoken critic of the Stroessner dictatorship. When Doctor Filartiga was away from home, an armed group broke into the house, then proceeded to abduct, torture and murder his son Joel.

Despite the Filartiga familys attempt to seek justice for the killing, the Paraguayan justice system failed to even properly investigate the case.

In 1979, when Dolly Filartiga was living in Washington DC, she discovered that one of Joels murderers, Americo Peña Irala, was also residing in Brookling (New York). The Filartigas immediately sought legal advice at the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), which sued Peña under the Alien Tort Statute.64

The ATS established that the “district court shall have original jurisdiction of any civil action by an alien for a tort only (civil liability), committed in violation of the Law of the Nations or a treaty of the United States” (28USC §1350). After several appeals, the Second Circuit of the District of Columbia finally reinstated the lawsuit and debated whether the alleged human rights infringement constituted a violation of the Law of the Nations. The circuit court finally recognized that torture did violate the Law of the Nations, and granted a reparation of U.S. $10 million dollars to the Filartiga family.

This decision was a turning point in U.S. federal law concerning international human rights issues. Based on Filartiga , many lawsuits for human rights violations committed abroad were filed by both aliens and U.S. citizens in cases of torture committed during the “war on terror,” 65 as well as by public officers and private agents.66

As the Center for Justice and Accountability has noted,67 various legal approaches have been taken in ATS cases: a) Individual accountability : human rights violations perpetrated by foreigners against foreigners in other countries who are living in the U.S., such as Filartiga; b) Governmental accountability : human rights violations perpetrated by U.S. officers against persons in other countries (or areas like Guantanamo Bay) such as Rasul v. Bush (2004); 68 and c) Corporate Liability , such as Due v. Unocal (2009) 69 or Kiovel v. Dutch Petroleum Co . (2013), 70 in which corporations are accused of participating in human rights violations against citizens of foreign countries (Burma and Nigeria, respectively).

The first approach was confirmed by Sosa v. Alvarez Machain71 (2004), which held that the ATS granted jurisdiction to the federal courts to hear cases involving “universally accepted norms” of international law.

The second approach, involving human rights abuses committed by U.S. officers against foreigners outside the U.S., was established by Rasul v. Bush72 (2004), which held that the U.S. Justice System had the authority to decide if non-U.S. citizens held in Guantanamo Bay were wrongly detained.

The third approach, corporate liability, was determined by Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co case (2013), 73 which rejected the plaintiffs’ claims about the international responsibility of corporations for human rights violations that take place outside the U.S. Its main argument was that the ATS did not apply extraterritorially in this case because it does not expressly affirm this right.

As many have concluded,74 the SCOTUS supports the use of international human rights norms when they are clearly set forth in law – except in cases involving corporate liability. In other words, established that cases must “touch and concern” to the United States to be considered by the federal justice system of the country.

IV. TWO MODELS, SOME SIMILARITIES

Notwithstanding their differences, some similarities exist between the Mexican and U.S. approaches that shed light on problems shared by all domestic courts that attempt to embrace cosmopolitan human rights standards.

- Socialization of human rights norms : The adoption of certain human rights principles by courts was and remains controversial. In both the U.S. and Mexico, there have been advances and setbacks between sovereigntist and cosmopolitan approaches.

- Separation of Powers : Autonomous legal decisions about international human rights norms may infringe on the foreign policy powers of the Executive Branch, expanding (at the risk of constitutional violation) the judicial branchs role in international affairs.

Despite these similarites, there are also many differences between the two models, most notably concerning extraterritoriality and hierarchy .

Extraterritoriality refers to the legitimate rights of the judiciary of one country to judge the citizens of a foreign country. In the U.S., this problem can be seen in many of the rulings regarding the use of the ATS. For example, under what conditions can a domestic court extend its jurisdiction to judge human rights violations committed in other countries? In the “human rights from within” model, foreign cases are admissible: (a) if the country where the human rights violations were committed is unable to bring the case to justice; or (b) if domestic law specifically allows extraterritorial powers.

Hierarchy. Although extraterritoriality is not a problem in Mexico, Mexican courts face another major issue: hierarchy. Do international norms in domestic human rights enforcement cases take precedence over domestic law? Put differently, is international human rights law considered at the same level of importance as the nations constitution?

And if the Supreme Court rules that international human rights law deserve the same level of judicial review as domestic law, to what extent can lower courts apply these norms in domestic cases without change judicial hierarchy?

In sum, while in the U.S. the main issue is the relationship “from the inside to the outside”; in Mexico, the problem is the relationship “from the outside to the inside”. However both of them are examples of ways to enforce the international responsibility to protect norm. The scope is in what cases the jurisdiction of the international community can rule at the domestic level.

V. FINAL REMARKS

This article has attempted to show two distinct human rights enforcement models currently in operation. Since World War II, diverse ways of human rights enforcement have been developed. Although no way necessary excludes any others, they illustrate two major concerns: a) human rights legal enforcement is polarized between legal sovereigntism and legal cosmopolitanism doctrines; and b) the conditions that allow human rights legal enforcement into and between States.

Probably the main remark of this article is that human rights legal enforcement is a contested arena and the judges and justices that are immerse in it face different dilemmas: the legal doctrine one, the separation of powers one; the extraterritoriality one and the judicial organization one.

The different models show diverse ways in which human rights legal enforcement are possible, from the strictly domestic to international ones. But once this was stated the second step was to analyze some of the dilemmas that judges took into account in their actual decisions.

The aim of this second step was to fill the gap between human rights and judicial politics. Two contrasting models were compared: the one that followed the Mexican judiciary after 2010 with the Radilla case, and the one that followed the U.S. judiciary after the Filartiga case of 1979.

The Mexican federal judiciary was a clear example of a contested change in the legal doctrine that favored the human rights from the outside, specifically from the Interamerican System. On the other hand, the U.S. judiciary was a clear example of contested legal doctrine that favored human rights from the inside.

But what were the main dilemmas that the judges dealt with, and continue to deal with, in

In the last decades we testify a “justice cascade”75 following diverse human rights legal enforcement models: Two Ad Hoc International Tribunals (For Rwanda and for the Former Yugoslavia and the ICC were established; the Pinochet affair took place; Efrain Rios Montt was prosecute for genocide in Guatemala; thousand of trials against Argentinian perpetrators of human rights abuses had been made etc. The examples developed here can be understood as part of this “cascade” and this dilemmas. Here some reasons about why, how and in what cases some judges have accepted international human rights norms were given. Nevertheles, more comparative research on the topic must be done to better understand the tensions that domestic judges and judicial institutions face in this endeavor 76 . To do that a judicial politics approach embedded in human rights politics and policies context (like the one applied) here can be helpful.

Notes

1. See Charles R. Beitz, The idea of human rights (Oxford University Press, 2011).

2. SeeKathryn Sikkink, The justice cascade: How human rights prosecutions are changing world politics ( W.W. Norton, 2011); Beth A. Simmons, Mobilizing for human rights: international law in domestic politics (Cambridge University Press, 2009); Emilie M. Hafner-Burton, International regimes for human rights, 15 Annual Review of Political Science 265,286 (2012). doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-031710-114414.

3. Cesare P.R. Romano, Proliferation of international judicial bodies: The pieces of the puzzle, 31 Int’l L.& Pol. , 709,751 (1999).

4. Social norm is defined as an “appropriate behavior” See Kathryn Sikkink, The justice cascade : How human rights prosecutions are changing world politics 11 (W.W. Norton, 2011)

5. Judicial politics are defined as “…the analysis of the political process through which the courts are constituted, and (judicial) decisions are taken and implemented” Keith Whittington; Daniel Kelemen; Gregory Caldeira. (2008). The study of law and politics. In Keith Whittington; Daniel Kelemen; Gregory Caldeira (Eds.), THE OXFORD HANDBOOK OF LAW AND POLITICS (pp. 4-14). Oxford: OUP Oxford.

6. Courtney Hillebrecht, The domestic mechanisms of compliance with international human rights law: Case studies from the inter-american human rights system, 34 -4 Human Rights Quarterly 959,985 (2012).

7. See Heinz Klug, Transnational human rights: Exploring the persistence and globalization of human rights, 1-1 Annual Review of Law and Social Science , 85,103 (2005) doi:10.1146/annurev.lawsocsci.1.041604.115903.

8. SeeKathryn Sikkink, The justice cascade: How human rights prosecutions are changing world politics 11 (W.W. Norton, 2011); Hunjoon Kim & Kathryn Sikkink, Explaining the deterrence effect of human rights prosecutions for transitional Countries1, 54-4 International Studies Quarterly , 939,963 (2010).

9. See Alexandra Valeria Huneeus, Courts resisting courts: Lessons from the inter-american Courts struggle to enforce human rights, 44-3 Cornell Int.L.J , 101,142 (2011); Erik Voeten, The impartiality of international judges: Evidence from the european court of human rights, 102-4 American Political Science Review 417,432 (2008).

10. United Nations General Assembly. Implementing the responsability to protect. Report of the Secretary General. A/63/677U.S.C. (2009).

11. Mahmoud Cherif Bassiouni , The future of human rights in the age of globalization , 40-1-3, Denver Journal of International Law & Policy 22,43 (2011).

12. Although it is still premature to say that Mexico decided to change this role in the international community regarding human rights in 2015 the Foreign Ministry of Mexico seems to change this disposition assuming an open critical approach to the recommendations of the international mechanisms like the Forced Disappearances or the Special rapporteur on Torture rejecting this reports.

13. See Curtis A. Bradley & Jack L. Goldsmith, Customary international law as federal common law: A critique of the modern position , 4-110, Harvard Law Review 815,876 (1997).

14. See Neil J. Kritz, Coming to terms with atrocities: A review of accountability mechanisms for mass violations of human rights, 59-4 (autumn) Law and Contemporary Problems , 127,152 (1996); Emilie M. Hafner-Burton, International regimes for human rights, 15 Annual Review of Political Science 265,286 (2012). doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-031710-114414.

15. See Gideon Sjoberg, et al., A sociology of human rights. 48-1 Social Problems 11-47 (2001).

16. Kathryn Sikkink, The transnational dimension of the judicialization of politics in Latin America, in The judicialization of politics in Latin America 263,292 (Rachel Sieder, et al., eds., 2005); Naomi Roht-Arriaza, The Pinochet effect: Transnational justice in the age of human rights (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005).

17. SeeRachel Sieder, et al., The judicialization of politics in Latin America (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005); Jeong-Woo Koo, & Francisco O. Ramirez, F. O., National incorporation of global human rights: Worldwide expansion of national human rights institutions, 1966-2004, 87-3 Social Forces , 1321,1353 (2009).

18. SeeJeffrey Davis, Justice across borders: The struggle for human rights in U.S. Courts (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

19. See Eric A. Posner, The perils of global legalism (University of Chicago Press, 2009); Roberto Gargarella, Human rights, international courts and deliberative democracy, in Critical perspectives in transitional justice (Nicola Palmer et al, eds., 2012); John Hagan & Ron Levi, Justiciability as field effect: When sociology meets human rights, 22-3 Sociological Forum , 372,380 (2007).

20. See Jeffrey Staton & Alexia Romero, Clarity and compliance in the Inter-American human rights system. American Political Science Association Meetings (2011); Emilia Justyna Powell & Jeffrey K. Staton, Domestic judicial institutions and human rights treaty violation, 53-1 International Studies Quarterly , 149,174 (2009); Alexandra Valeria Huneeus, Courts resisting courts: Lessons from the inter-american Courts struggle to enforce human rights, 44-3 Cornell Int.L.J , 101,142 (2011); Karen Alter , Establishing the supremacy of european law : The making of an international rule of law in Europe (Oxford University Press, 2001); Rachel Kerr, The international criminal tribunal for the former yugoslavia : An exercise in law , politics , and diplomacy (Oxford University Press, 2004); william A. schabas , the UN international criminal tribunals : The former Yugoslavia , Rwanda and Sierra Leone (Cambridge University Press, 2006); David Pion-Berlin, The Pinochet case and human rights progress in Chile: Was Europe a catalyst, cause or inconsequential? 36-3 Journal of Latin American Studies , 479,505 (2004); Erik Voeten, The politics of international judicial appointments: Evidence from the European court of human rights, 61(Fall) International Organization 669,701 (2007); Dancy, Geoff., & Sikkink, Kathryn. (2011). Ratification and human rights prosecutions: Toward a transnational theory of treaty compliance. NYUJ Int’l L.& Pol., 44 , 751.

21. See Catalina Smulovitz, The past is never past: Accountability and justice for past human rights violations in Argentina (2012) (Unpublished manuscript).

22. See Cath Collins , Post-transitional justice : human rights trials in Chile and El Salvador . (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010).

23. See Karina Ansolabehere Sesti, Difusores y justicieros: Las instituciones judiciales en la política de derechos humanos, 22-44 , Perfiles Latinoamericanos 143,169 (2014).

24. Program of Law and Public Affairs, Introduction, THE PRINCETON PRINCIPLES ON UNIVERSAL JUSTICE, 23,(2001) (AUG 3,2015) https://lapa.princeton.edu/hosteddocs/unive_jur.pdf . The Pinochet case was an excellent example of the use of this jurisdiction. See David Pion-Berlin, The Pinochet case and human rights progress in Chile: Was Europe a catalyst, cause or inconsequential? 36-3 Journal of Latin American Studies, 479,505 (2004).

25. Each of them belongs to the European, the interamerican, and the African systems of human rights respectively.

26. These principles are established in international law to established the relationship between domestic and international institutions. The can be understood as follow: a) concurrency principle refers to the primacy of an international tribunal over the domestic courts, for example to prosecute crimes against humanity or human rights abuses, the main example of this principle are the Ad Hoc Tribunals for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia; b)complementarity principle refers to the primacy of domestic courts over the international ones that only can, for example, prosecute human rights abuses and when the nation state be unwilling or unable to prosecute this crimes, the International Criminal Court follows this principle; c) the subsidiarity principle means that the international tribunal only will have jurisdiction after all domestic procedures are exhausted, the Interamerican System is guide by this principle.

27. Even when there is not an standard definition of Human rights politics, here they will be understood as follow: the various political processes through which human rights’ norms, ideas and discourse are disseminated, acquiring particular characteristics in different social, political and legal contexts . One of the basic features of contemporary human rights’ politics is its essentially transnational character, which recognizes both governmental and non-governmental agents as key actors of these processes

28. There are some samples of studies of the judicial politics of human rights judicial institutions. See Erik Voeten, The impartiality of international judges: Evidence from the European court of human rights, 102-4 American Political Science Review 417,432 (2008); Erik Voeten, The politics of international judicial appointments: Evidence from the european court of human rights, 61(Fall) International Organization 669,701 (2007).

29. See Karina Ansolabehere Sesti , La política desde la justicia . México (FLACSO-Fontamara, 2007).

30. Rosendo Radilla Pacheco et al v. México, Case 2009 Inter-Am. Ct. H.R., (Nov. 23, 2009).

31. Id.

32. See John Ackerman , Organismos autónomos y democracia : El caso de México (Siglo XXI, 2007).

33. See Alejandro Anaya Muñoz, Transnational and domestic processes in the definition of human rights policies in México , 31-1, Human Rights Quarterly 35,58 (2009)

34. Id.

35. File 912/2011.

36. A corrido is a traditional Mexican music genere.

37. Asociación de Familiares de Desaparecidos de México- AFADEM.

38. Comisión Mexicana de Defensa y Promoción de Derechos Humanos

39. See Silvia Dutrénit Bielous, Sentencias de la corte interamericana de derechos humanos y reacciones estatales: México y Uruguay ante los delitos del pasado, 61- aug. América Latina hoy , 79,99 (2012).

40. Rosendo Cantú et al v. México, Case 2010 Inter-Am. Ct. H.R., (Aug. 31, 2010).

41. Fernández Ortega et al. v. México, Case, 2010 Inter-Am. Ct. H.R., (Aug. 30, 2010).

42. Cabrera García &Montiel Flores v. México Case, 2010 Inter-Am. Ct. H.R., (Nov. 26, 2010).

43. Rosendo Radilla Pacheco et al v. México, Case 2009 Inter-Am. Ct. H.R., (Nov. 23, 2009).

44. Suprema Corte de Justicia, Exp 489/2010.

45. Id.

46. Crónica del pleno y las salas sesiones 4, 5, 7, 11, 12 y 14 de julio de 2011 , Pleno de la Suprema Corte de Justicia [S.C.J. N.] [Supreme Court], (Méx.).

47. On September 3rd 2013, the Mexican Supreme Court main chamber made a decision that stated that in the case of contradiction between the Constitution and the International Treaties, the constitution must prevail. Looking at this decision it is clear that the change from a sovereigntist legal culture to an internationalist one is a disputed process and this debate has only begun.

48. “Control de Convencionalidad Difuso” in spanish.

49. Roger Cotterrell, Why must legal ideas be interpreted sociologically? 25-2 Journal of Law and Society , 171,192 (1998).

50. Suprema Corte de Justicia, Tesis de Jurisprudencia P/J 87/2004.

51. Suprema Corte de Justicia, Acuerdo 912/2010.

52. See Christina Cerna, Unconstitutionality of article 57, section II, paragraph a) of the code of military justice and legitimation of the injured party and his family to present an appeal for the protection of constitutional rights , 107-1 American Journal of International Law 199,206 (2013).

53. The idea of Law of the Nations originates in the XVIII Century and refers to the customs, norms and treaties accepted as standards of “good” behavior for the international community.

54. See Tom Farer, Democracy, human rights and the United States: Tradition and mutation, in Human rights regimen in the Americas 56, 83 (Mónica Serrano & Vesselin Popovski, eds., 2010).

55. See Samuel Moyn , The last utopia : Human rights in history (Harvard University Press 2010).

56. See Cynthia Soohoo et al. , Bringing human rights home (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007); Shareen Hertel & Kathryn Libal , Human rights in the united states : Beyond exceptionalism (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

57. See Kathryn Sikkink, The justice cascade: How human rights prosecutions are changing world politics (W.W. Norton, 2011).

58. Filartiga v. Peña Irala, 630 F.2d 876 2d. Cir. (1980).

59. Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co. , 133 S.Ct. 1659 (2013).

60. The idea of Law of the Nations was originated in the XVIII Century, to refer to the customs and values that the international community accepts as bases of the relationships beetwen its members. Contemporarily this idea is behind the idea of human rights legal enforcement.

61. Refers to pleople with “close ties” with USA, for example a person or a company that makes business within the United States.

62. See Jeffrey Davis , Justice across borders : The struggle for human rights in U.S. Courts (Cambridge University Press, 2008); Beth Stephens , International human rights litigation in U.S. Courts (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2008).

63. Filartiga v. Peña Irala, 630 F.2d 876 2d. Cir. (1980).

64. See Center for Constitutional Rights [CCR] Filartiga v. Peña Irala, http://ccrjustice.org/ourcases/past-cases/fil%C3%A1rtiga-v.-pe%C3%B1-irala , (last visited Aug.15th 2013).

65. An example of this line of litigation was Rasul v. Bush, 542 U.S. 466. (2004).

66. To see an extended description of many of the most important cases using ATS it is possible to consult the web page of Center for Constitutional Rights http://www.cja.org/article.php?id=334 (consulted 03/05/2015)

67. See The Center for Justice & Accountability [CJA], The Alien Tort Statute. A means of redress for survivors of human rights abuses, http://www.cja.org/article.php?id=435 , (last visited Aug. 15th 2013).

68. Rasul v. Bush, 542 U.S. 466. (2004).

69. Doe v. Unocal, 395 F.3d 932 (9th Cir. 2002).

70. Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co. , 133 S.Ct. 1659 (2013).

71. Sosa v. Alvarez-Machain, 542 U.S. 692 (2004).

72. Rasul v. Bush, 542 U.S. 466. (2004).

73. Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co., 133 S.Ct. 1659 (2013).

74. See Jeffrey Davis , Justice across borders : The struggle for human rights in U.S. Courts (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

75. SeeKathryn Sikkink, The justice cascade: How human rights prosecutions are changing world politics (W.W. Norton, 2011); Kathryn Sikkink & Hum Joon Kim, The justice cascade: The origins and effectiveness of prosecutions of human rights violations. 9-1 Annual Review of Law and Social Science 269,285 (2013). doi:10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-102612-133956; Tricia D. Olsen, et al., Transitional justice in balance: Comparing processes, weighing efficacy (U.S. Institute of Peace, 2010).

76. Ezequiel Gonzalez Ocantos, Persuade them or oust them: Crafting judicial change and transitional justice in Argentina 46-4 Comparative Politics, Forthcoming , 279,298 (2014).

Document information

Published on 15/05/17

Submitted on 15/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?