Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

In a globalized and media society with unprecedented technological development, institutions of higher education are adapting their training models to face this new challenge. This study aimed to determine students' self-perception of their media competence and the differential influence of an ecosystemic model of training that is being implemented experimentally. The research methodology is mixed, as both a quantitative (descriptive and inferential analysis) as well as a qualitative analysis (are made of the contents of the open reports). A total of 808 university students enrolled in the 2015-16 course in different university centres and countries (Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, and Faculty of Economics-Business of University of Oviedo (Spain) and Technological Institute of Mexico), completed a questionnaire about media competence and wrote open reports about their experience with ecosystemic models. The results showed that university students have a favorable self-perception of their level of media competence, and they consider it important to develop by means of transversal training and ecosystemic training models. Significant differences between the students of the different degrees also emerged depending on whether or not an ecosystemic approach was used to develop the subjects. In conclusion, the study shows that these models favor teaching-learning processes in the university by adapting the technology to the users and improving their media competence.

1. Introduction

Society, education and the university are destined to reinterpret their relationships at each historical moment based on the priorities that are deemed appropriate by the entities, governments, businesses or advocacy-groups that have the ability to make decisions according to the available resources in order to answer to the needs or demands of the population, in general, and of the organizations and professional workers, specifically.

If we accept this argument, then we accept the premise that society is in constant transformation (Toffler, 1980) due to its informational (Castells, 1999) and fluid (Area, 2012) characters, and that communication has an effect on the basic tasks of people in their social, work, political, economic, cultural and personal environments. This makes it necessary for the educational institutions to provide learning models that are coherent so that the citizens become competent in a media-ruled environment where the television, films, the radio, the press, computers, social networks, tablets, videogames or mobile phones form part of everyday life (Fedorov, 2014; Gozálvez, 2013). In this globalized media context, the users of this technology must have continuous literacy that will help them become “competent prosumers” (Caldeiro-Pedreira & Aguaded, 2015; Sánchez & Contreras, 2012), as these technological tools emerge and evolve in a constant spiral that demands from the people a critical and ethical analysis of a scenario where they are receptors and producers of messages.

In the process of constructing the European Higher Education Area (EHEA), the universities have been taken of this situation into account, and have therefore designed work environments by deploying different strategies that are interconnected in their objectives, their possibilities and their user’s profiles. The problems come from their intentions not being linearly translated into practice, as multiple problems arise during the implementation processes (Ferrés & Masanet, 2015), as a result of the frictions that are generated with the organizational and functional cultures of the University faculties, schools and departments, as they are full of social, cultural and political meanings that filter the external prescriptions to adapt them to interests that have different meanings.

Nevertheless, it cannot be denied that there have been many advances contributed by research studies, highlighting, among others, the importance that is attributed to the learner (León & Latas, 2005); the classroom context (Entwistle & Tait, 1990); the institutional environment (Ramsden, Martin, & Bouden, 1989); the pedagogic competence (Sánchez-Gómez & García-Valcárcel, 2002); the curriculum (Gimeno-Sacristán, 2001; 2008); technology and social networks (García-Galera, 2013); collaboration (Kolloffel, Eysink, & Jong, 2011); active methodologies (Cano, 2009); study plans (Zabalza, 2002); teaching-learning processes (Carracosa, 2005); formative (internal) evaluation (Monereo, 2009), organizational models (Buckland, 2009) and media education. Their conclusions make it necessary to reflect, in a reasoned and calm manner, on how to improve the quality of teaching at the university, starting from the experiences available and attending to the need of bolstering transversal and longitudinal media education “that overcomes the excessively-technological and instrumental vision, that due to the trends and technological advances, have frequently confounded politicians, administrators and society in general, and has distorted and ignored the inherent characteristics and qualities of the media when taking education into account” (Aguaded, 2012: 260). The main content of this article is framed within this context, and presents an overview of blended-learning teaching ecosystems that have been utilized in the last few years (Álvarez-Arregui & Rodríguez-Martín, 2013), as they have been considered a viable alternative for shifting from an information society towards a society of media knowledge and inclusiveness (DeJaeghere, 2009; Rodríguez-Martín & Álvarez-Arregui, 2014).

1.1. Training ecosystems in university teaching

Training ecosystems in higher education are relatively recent, although there are currently many innovative experiments that are promoting dynamic and collaborative relationships between community members. Among the promising proposals, we find the Modular ecosystem (Dimitrov, 2001); the Knowledge ecosystem (Shrivastava, 1998); the e-learning ecosystem for management and support of learning (Ismail, 2001); the e-learning ecosystem for governance (Chang & Lorna, 2008) or the learning ecosystem (LES) of Gült and Chang (2009). These models incorporate learning design, human resources, training for the development of basic competencies, a communication system, and different applications (Shimaa, Nasr, & Helmy, 2011). Although we coincide with the basic tenets, we believe, as do other authors, that the dangers derived from an excessive shift towards e-learning should be analyzed (Uden, Wangsa, & Damiani, 2007), as the communication potentials that in-person learning technologies bring, could be wasted. This is the reason why we prefer to align ourselves with blended-learning models.

1.2. A learning ecosystem to learn to undertake (ECOFAE)

Taking into account the research cited above, we have been developing a model at the University of Oviedo that we have applied to training projects in education, social and work areas as well as in innovation and research projects (Figure 1) that aims to develop professional communities of learning that are interconnected, cohesive and self-regulating within national and international institutions. The construction of this ecosystem is the result of posing questions and planning a reference structure that is flexible and dynamic that can be continuously perfected thanks to diagnosis, evaluations and research. The basic design of the model is composed of five phases:

– Phase I. Planning and diagnosis. Instruments that provide us with information at the start and the end of the process are prepared in order to determine the needs and the impact of the education intervention. The students complete diverse questionnaires (study habits, communication and digital competency, learning styles, etc.).

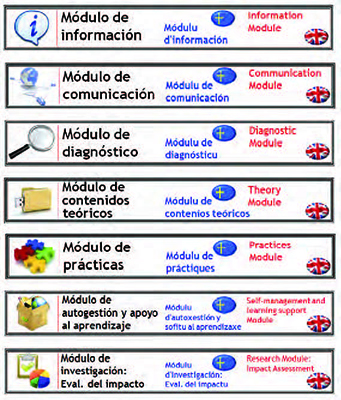

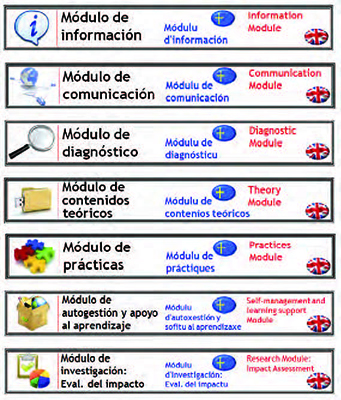

– Phase II. Design of the training context. This is constructed around two spaces, the virtual and the in-person. The virtual surroundings adopt a modular, scalable and adaptable structure (Figure 2).

• Information module. Here we incorporate the degree’s documentation, the official program of the course, the general bibliography and the news forum.

• Communication module. In this module, all the available communication tools are included (forum, Skype, blog, Facebook, Twitter, etc.).

• Diagnostic module. The elements allow the student body to understand their learning styles, study habits, media competency and previous knowledge. In Dropbox, Google calendar and in general forums, we collect what is expected and the perceptions on the subjects, which will be compared at the end of the academic year.

• Theory module. A general guideline of the contents, schemes, links, bibliographic references, presentations (PowerPoint, Prezi…) are included here, so that all the participants (student body and professionals) can access them.

• Practices module. Individual, group, in-person and virtual activities are planned.

• Self-management and learning support module. A bank of resources and good-practices are found here.

• Research and impact assessment module. Here we find the official external assessments that are conducted by the Technical Quality Unit from the University of Oviedo and internal evaluations, where we find the information provided in the forums, the blogs, the social networks, in the classroom debates and the research studies.

– Phase III. Deployment of the learning model. This is done through four systems:

- Registration and information system.

- Tutoring and counseling system.

- Relations and communications system.

• Self-assessment of learning system.

– Phase IV. Evaluation of improvement. This module is structured into three sections:

• First. This shows the results of the evaluations that are conducted by the Technical Quality Unit from the University of Oviedo.

• Second. This collects the public opinions (blogs, forums, Facebook, Twitter…) given by the students on the methodologies that are being implemented.

• Third: It compares the initial diagnostic of the participant’s profiles with their state at the end of the semester; their degree of satisfaction with the training ecosystem and the competencies acquired are determined.

– Phase V. Research on impact and transfer. Periodical research studies on the processes, results and the model design are conducted.

Talking into account this design, we put forward this research work, with the aim of determining the degree of self-perception the students have on their media competency, and to analyze the degree of influence that the blended-learning ecosystems have within it when used as a training modality. More specifically, we aim to 1) Understand the participating university student’s self-perceived media competency; 2) Evaluate the indicators of media competency that are more important for the students; 3) To determine the impact of the training ecosystems in the self-perceived media competency; 4) Analyze the value that the student body grants to the training ecosystems.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

The empirical study was conducted in Spain and in Mexico through the use of questionnaires. In the case of Spain, this was conducted at the University of Oviedo with students in the Pedagogy Degree (n=122) and the Primary Education Teacher degree (n=182), administered by the Faculty of Teacher Training and Education; as well as the Business Administration Degree (n=192) taught by the Faculty of Economics and Business. And in the case of Mexico, at the Technological Institute of Mexico (Michoacán) with students enrolled in the Business Management Engineering (n=105), in the Industrial Engineering (n=114) and the Electrical Engineering Degrees (n=103).

The target audience of the questionnaire, starting from non-probabilistic sample, was a set of 808 second and third-year students, which totaled 53.7% of the 1505 students enrolled in the 2015-16 academic year at both participating institutions. During the research study, 118 reports were contributed by the students enrolled in the Pedagogy and Teacher Degrees from the Faculty of Teacher Training and Education at the University of Oviedo (Spain; n=60) and the Industrial Engineering and Electrical Engineering Degrees from the Technological Institute (Mexico; n=58) that participated in the implementation of the ecosystemic model of training for the development of media competency.

2.2. Instruments and procedures

The instrument used to evaluate media competency was a questionnaire (77 items) that had already been statistically validated (Gozálvez-Pérez, González-Fernández, & Caldeiro-Pedreira, 2014), while a custom-made scale was used for understanding the level of satisfaction with the training model (20 items), which was validated in previous international research studies (Álvarez-Arregui & Rodríguez-Martín, 2013). These instruments were applied between October, 2015 and January, 2016, and were presented to the participants in an integrated manner divided into four sections (97 items):

• Participant profile (37 items): gender, degree, faculty, type of center attended for upper secondary education (baccalaureate), academic trajectory, mastery of languages, knowledge of computer programs, time spent and use of computers and mobile phone for study and leisure.

• Self-perceived media competency (29 items), with a range of answers of 4 points: 1 (very low), 2 (low), 3 (average) and 4 (high).

• Importance attributed to different competencies related to media education (11 items), with a range of answers of 4 points: 1 (not important), 2 (low importance), 3 (average importance), 4 (high importance).

• Design of the training ecosystem, its tools and its influence on the development of media competency (20 items), with a range of answers of 4 points: 1 (none), 2 (little), 3 (sufficient), 4 (a lot).

The sampling error was 5.5% (95%), and the level of confidence Z=1.96; p=q=0.5 (95%). The level of reliability was calculated with Cronbach’s alpha (.916); the correlation between forms (0.592), Spearman-Brown Coefficient (.770) and Guttman’s split-half (.759). Validity was determined through three internal expert reviews, two professors from the University of Oviedo, a professor from the University of Cantabria, and an expert professional from Lausanne (Switzerland).

The quantitative information from the questionnaire’s items were analyzed with the SPSS 19 software program for: reliability analysis, frequency analysis, mean differences (T-Test for independent factors, using Student’s T-test and Levene’s test to estimate equality of variances) as well as Analysis of Variance (ANOVA and the post-hoc Scheffé’s test with the one-way subprogram).

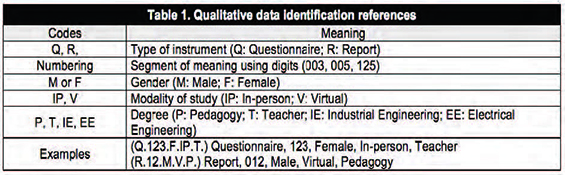

The qualitative data were generated from the comments to the open-ended questions from students enrolled in the three degrees and the 118 open reports provided by the students from the Pedagogy and Teacher degrees. The content analysis was conducted with the Aquad 7.0 program (Huber & Gürtler, 2013). The qualitative information was transcribed and exported to the program, and the analysis conducted were oriented towards reducing/grouping information through a search of keywords, elaboration of segments of meaning, cataloguing, linking and code cross-referencing. The comments that illustrated the arguments were identified with specific codes.

3. Analysis and results

3.1. Self-perceived media competency

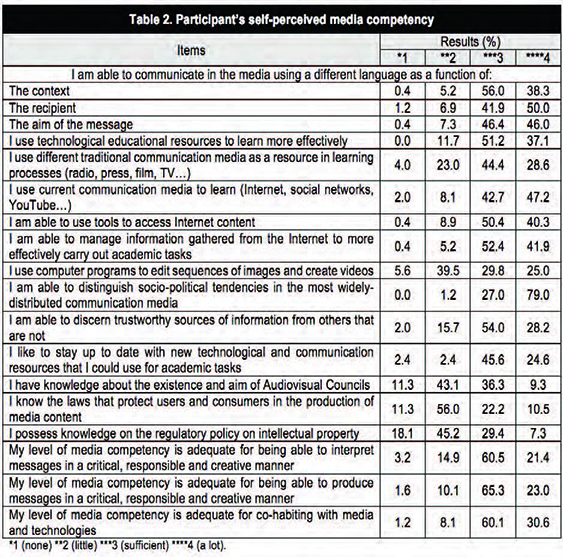

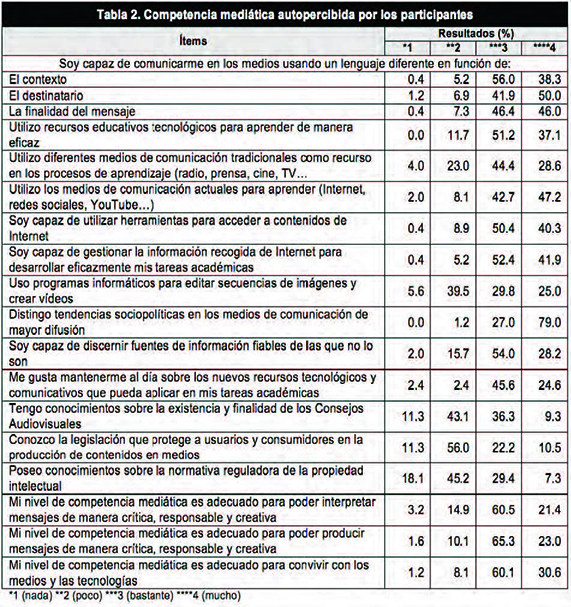

The students generally evaluated their media competence as being adequate, although some nuances should be noted. As a group, they considered themselves able (79%) to evaluate the sociopolitical tendencies of the most widely-circulated communication media, to communicate through the media by utilizing a language that was different according to the audience (50%) and the aim of the message (46%), as well as utilizing technology in their learning processes.

These general perceptions should be put into context if we take into account that only 23.4% were able to clearly differentiate between the different codes utilized by the emitter in the messages they received from the media, almost a third (30.6%) believed that their media competency had an adequate level for co-habiting with technological media. To a lesser degree, they were able to interpret and produce messages in a critical, responsible and creative manner, as well as using software programs to edit sequences of images and to create videos.

In general, they were able to differentiate between reliable and non-reliable sources of information. Their failings were associated with the lack of knowledge on the existence and/or aim of the Audiovisual Councils, legislation that protects the users in the production of media content and intellectual property. Their interest for being current on technological and communicative resources was highlighted when they could be applied to academic tasks. Therefore, the students’ predisposition in this area should be taken advantage of.

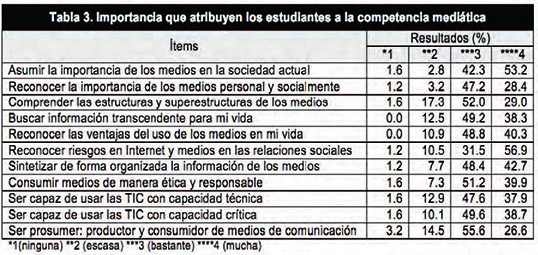

A great majority of the students positively-valued the importance of media competency in society (53.2%) and the management of information (42.7%), but they also recognized its risks (56.9%), which led to their positive opinion on their ethical and responsible consumption. They also recognized the advantages of media use in their day-to-day lives (40.3%), but they did not grant too much importance at the personal and social levels (28.4%) to using the ICT, technically or critically, as they believed that was enough to be able to use them habitually as consumers. Therefore, being a prosumer did not worry them in excess (26.6%), or trying to understand the structures and super-structures of the media.

The significant differences found in gender indicated that men communicated better as a function of the recipient (0.17). When attending a public school in the upper two academic years of high school (.018), they used, to a greater degree, computer programs to edit image sequences and create videos (.015), and were able to distinguish the sociopolitical tendencies of the media (.015).

Knowledge of Audiovisual Councils was greater in men (.031), while women had more information on the regulatory policy on intellectual property (.021). The students with a worse academic trajectory were not as worried about being up to date with technological and communicative resources that they could use in their academic tasks (.004).

Use of the computer for study and leisure had differences. In the first case, we found a negative correlation, where the lesser use of technological tools was related to a greater pre-disposition to relying on classical communication media (.000), and was shown to be less linked to the new technological media (.013). However, those who used the computer for more than three hours a day better differentiated the languages as a function of the final aim of the messages (.033), relied more on current communication media (.002), and were able to better distinguish the socio-political tendencies of the media (.009). For those students that used the computer for more than three hours a day for leisure, there was a positive correlation with their media competency in ten of the sixteen items considered, adding value to this habit.

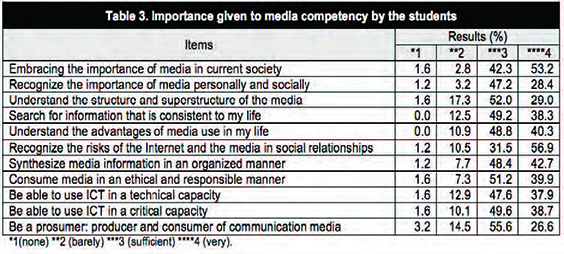

3.2. Importance of media competency

The students indicated that it is important to know the risks of the Internet and the media in their social relationships, so that their importance should be dealt with when the information they provide is adequately managed. They also mention, to a lesser degree, the need to be a “prosumer”, to be able to utilize the media in a responsible manner, access relevant information and relate in a more personal, social and professional manner. In any case, there were clusters that were not interested in understanding the superstructures of the media or being “prosumers”, which is related to unawareness, deficiencies and opposition.

The significant differences found indicated that the students from the Business Engineering degree (.017) gave more importance to communication media in society, but granted less importance to searching for information that is important for their life (.002), being a prosumer (.000) and to consume media in an ethical and responsible manner (.028). Those who attended private/public subsidized centers in the last two years of high school granted less value to the media in their personal and social lives (.001), and those who had an excellent trajectory were interested in understanding the structures and superstructures of the media (.022), to look for information that was important for their lives (.017), to consume media in an ethical and responsible manner (.000) and to being prosumers (.013).

As for the use of the computer and the mobile phone for study and leisure, in all the significant differences found, a positive correlation between a greater use of these tools and an increase in the importance that is attributed towards media education, was confirmed.

3.3. Evaluation of the learning ecosystem (ECOFAE)

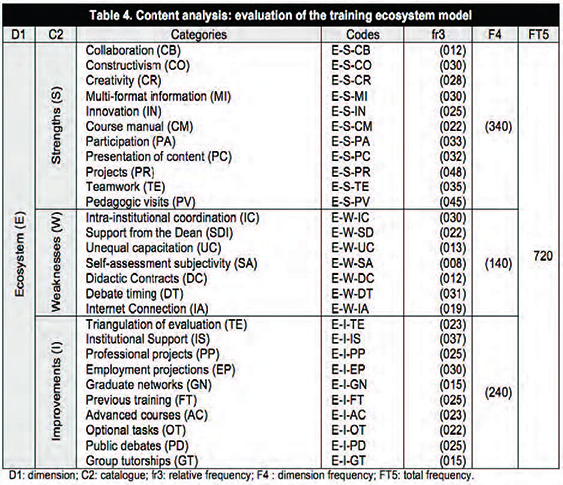

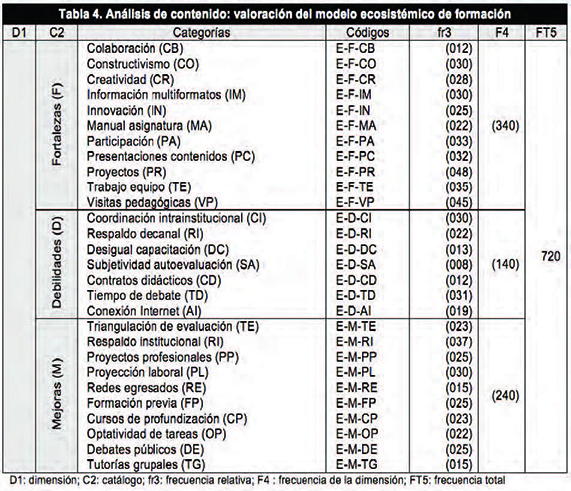

The 118 reports contributed by the students and the open-ended questions from the 808 questionnaires generated 2,400 paragraphs containing 73,425 words, which were used for content analysis.

– Catalogue 1. Strengths. 340 codes emerged. The aspects that were considered the most positive were the projects that were associated to specific thematic content or linked to real collaboration projects with socio-educational centers (inter-institutional relationships). In the same direction, we found the pedagogic visits, the increase in the participation with active methodologies of work in the classroom, and through tools available on campus and on the Web 2.0, teamwork, treatment of information in multiple formats, innovation, creativity, collaboration and the constructivist focus adopted by the professors.

• “The Snowball technique is very innovative, because we have seen that sharing with our classmate, the group, with the class and through the blog and Twitter allowed us to broaden our knowledge and what was commented in the social networks” (R.12.M.V.P.)

• “Project-based work favors collaboration between classmates, the ecosystem created is a novel way of being able to collaborate with each other…an example is when we share images in Twitter, when create entries in the blog, we upload all kinds of materials that we always have available” (R.6.F.IP.P.).

• “The project that a group presented, where they invited other professors and first-year students, where we changed classrooms according to the activity, where songs were presented, where performances were conducted, where everything that happened was recorded and directly uploaded to Twitter and the blog seemed to me a very clear example that things can be changed” (R.4.M.IP.P.).

– Catalogue 2. Weaknesses. There were 140 segments that were related to the difficulty in debating at the end of the sessions, the presentation time of the projects, the contents addressed, and the low level of coordination among the teaching staff.

The presentation of the ecosystem gave the students an initial anxiety, as it implied a change in the way that didactic relationships were commonly interpreted, although the students were conscious that this focus demanded from them a greater personal, team and collective commitment, as well as the development of proactive attitudes to deploy innovative, creative and co-responsible methodologies mediated by the ICT.

• “The drawback that I give the training ecosystem is that there was a lack of coordination with other courses, and I don’t see that the Dean supports these actions either, because there are always problems with outings, for example” (R.7.F.IP.P.).

• “The way of working is different, it sensitizes you, because when you see images of what you do in class, of the pedagogic trips, activities outside of the classroom… I don’t know how to explain it, it’s different” (Q.55.F.IP.M.).

• “The methodology used to present ourselves, to speak in public from anywhere in the classroom, the fact that your classmates can support you if your mind is blank…all these things make you more secure in yourself and to evaluate the support provided by your classmates (…)” (R.21.F.IP.P.)

– Catalogue 3. Improvements. 240 codes emerged. The following are highlighted: The need to increase the institutional support for the development of the projects, orient them to the real-life work environment and to Service-Learning, grant greater freedom in choosing of teams and projects, develop training courses when needed and change the way group tutorships are conducted, as an entire day could be used for them in order to share experiences with other classes or visit good-practices centers. The triangulation between evaluation, video-conferences and round tables with graduates, public debates or the solving of problems with technology are other necessary and logical demands if the implementation of training ecosystems in a generalized way is desired.

• “As an in-person student, I would like to be able to participate in service-learning, at least through technological tools” (R.16.M.IP.P.).

• “In the beginning, I, as well as other classmates, had problems adapting and working with the ecosystem’s tools, as we were unaware about their existence. It would be good if we could have had previous training” (R.42.F.IP.P.).

• “The work that we have done within the ecosystem could be more useful if the professors were coordinated with each other, and if we had access to practice sessions and contacts with professional workers through the social networks” (R.33.F.IP.M.).

4. Discussion and conclusions

The results obtained indicate that the blended-learning training ecosystems develop media competency in the Bachelor’s degrees and are well-accepted by the student body. They are presented as an attractive proposal that requires an initial high investment of energy in time and dedication, but can provide benefits associated to the development of professional competency, inter-disciplinarity and media literacy. The implementation of the model is backed by the greater self-perception that the students had on their media education and by the importance they granted to the need to bolster literacy in the field of knowledge as a transversal competency in university studies. Therefore, the models should be institutionally backed in the study plans so that they are integrated into organizational cultures in order to answer to the needs of the users, the professional workers and society, in agreement with contributions by other authors (Tello & Aguaded, 2009). The differences found between degrees and faculties evidence the good self-perception of the students on their media competency, in line with other research works (González-Fernández, Gozálvez-Pérez, & Ramírez-García, 2015), who highlighted the positive impact of active methodologies and the use of digital technologies in the development of this competency.

The over-valuation that the students granted their media competency was the result of their restricted view of the use of tools and programs for relating or informing themselves, as these (simple) actions do not imply a true literacy that can turn them into true prosumers. The study shows a positive correlation where it was evident that the greater the amount of time using computer systems and mobile phones for school-related tasks and leisure, the better self-perception was of media competency. This is also what occurred when the students developed group projects relying on principles that guided training ecosystems, as the processes of blended-learning teaching-learning that were created, favored media competency, the creation of professional communities and the relationships with the labor market.

A training ecosystem that is oriented towards the development of media competency increases the user’s satisfaction, independently of its initial demands. Its potential is expanded when it becomes part of the organizational culture under the auspices of the institution, as indicated by other authors (Gewerc, Montero, & Lama, 2014; Senge, 1990). The planning, design, methodologies, resources, tasks and the commitment of its sponsors has a positive effect on the participants when they work on projects that are technologically-based and oriented towards media education (García-Ruiz, Ramírez-García, & Rodríguez-Rossell, 2014).

The problems detected warn us to develop proposals of continuous improvement that could become the benchmark that guides us through the construction of future ecosystems. Therefore, the need for previous training of the users –the staff, professional workers and students–, the infrastructures, the improvement of evaluations systems, the mechanisms of coordination inside and outside of our institutions, and the institutional backing, should be attended to if we want to promote blended-learning training ecosystems in a coherent and holistic manner.

The deployment of the training ecosystems mediated by technology is significant in its use of time and resources, but it can orient processes of change in those Higher Learning institutions where ambiguity of objectives, decoupling and diversity of interests dominate over collaboration, innovation and continuous improvement. The objective of education in the 21st century is to train generations of citizens in media competency, which implies incorporating into the curriculum, in a transversal manner, a process of literacy for everyone throughout their lifetimes, so that they are fully competent in the access, interpretation and re-utilization of varied and multiple digital ways of representation of information and knowledge.

Funding agency

This research study was conducted within the framework of the Research Project “Design, Implementation and International Evaluation of Blended-learning Training Ecosystems in Higher Education (cod. PAIN1-10-001)”, granted by the University of Oviedo, and has relied on advice from the Innovation Acceleration Platform “Innobridge”, with headquarters in Lausanne (Switzerland).

References

Aguaded. I. (2012). La competencia mediática, una acción educativa inaplazable. [Media Proficiency, an Educational Initiative that Cannot Wait]. Comunicar, 39, 7-8. https://doi.org/10.3916/C39-2012-01-01

Álvarez-Arregui, E., & Rodríguez-Martín, A. (2013). Gestión de la formación en las organizaciones desde una perspectiva de cambio. Principios básicos y estrategias de intervención. Oviedo: Ediuno.

Area, M. (2012). Sociedad líquida, Web 2.0 y alfabetización digital. Aula de Innovación Educativa, 212, 55-59.

Buckland, R. (2009). Private and Public Sector Models for Strategies in Universities. British Journal of Management, 20(4), 524-536. (http://goo.gl/bPvxVt) (2016-11-25).

Caldeiro-Pedreira, M.C., & Aguaded, I. (2015). Alfabetización comunicativa y competencia mediática en la sociedad hipercomunicada. Revista Digital de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria, 9(1), 37-56. https://doi.org/10.19083/ridu.9.379

Cano, R. (2009). Tutoría universitaria y aprendizaje por competencias ¿cómo lograrlo? Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 12, 181-204. (http://goo.gl/SwlBry) (2015-11-11).

Carrascosa, J. (2005). La evaluación de la docencia en los planes de mejora de la Universidad. Educación XXI, 8, 87-101. (http://goo.gl/J5E1gP) (2015-10-04).

Castells, M. (1999). La era de la información. Fin de milenio. Madrid: Alianza.

Chang, V., & Lorna, U. (2008). Governance for e-learning Ecosystem. In E. Chang, & F. Hussain (Ed.), II IEEE International Conference on Digital Ecosystems and Technologies, 340-345. Phitsanulok (Thailand): Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

DeJaeghere, J. (2009). Critical Citizens Education for Multicultural Societies. Interamerican Journal of Education and Democracy, 2(2), 223-236. (https://goo.gl/XxOUBT) (2015-11-22).

Dimitrov, V. (2001). Learning Ecology for Human and Machine Intelligence: A Soft Computing Approach. Studies in Fuzziness and Soft Computing, 81, 386-393. (http://goo.gl/TgXmvW) (2016-11-01).

Entwistle, N., & Tait, H. (1990). Approaches to Learning, Evaluations of Teaching, and Preferences for Contrasting Academic Environments. Higher Education, 19, 169-194. (http://goo.gl/MKbfrs) (2016-08-09).

Fedorov, A. (2014). Media Education Literacy in the World: Trends. European Researcher, 67(1-2), 176-187. https://doi.org/10.13187/issn.2219-8229

Ferrés, J., & Masanet, M.J. (Coords.) (2015). La educación mediática en la universidad española. Barcelona: Gedisa.

García-Galera, M.C. (2013). Twittéalo: la Generación Y su participación en las redes sociales. Crítica, 985, 34-37. (http://goo.gl/5DbdM9) (2015-11-27).

García-Ruiz, R., Ramírez-García, A., & Rodríguez-Rosel. M. (2014). Educación en alfabetización mediática para una nueva ciudadanía prosumidora. [Media Literacy Education for a New Prosumer Citizenship]. Comunicar, 43, 15-23. https://doi.org/10.3916/C43-2014-01

Gewerc, A., Montero, L., & Lama, M. (2014). Colaboración y redes sociales en la enseñanza universitaria [Collaboration and Social Networking in Higher Education]. Comunicar, 42, 55-63. https://doi.org/10.3916/C42-2014-05

Gimeno-Sacristán, J. (2001). Educar y convivir en la cultura global. Madrid: Morata.

Gimeno-Sacristán, J. (2008). Educar por competencias. ¿Qué hay de nuevo? Madrid: Morata.

González-Fernández, N., Gozálvez-Pérez, V., & Ramírez-García, A. (2015). La competencia mediática en el profesorado no universitario. Diagnóstico y propuestas formativas. Revista de Educación, 327, 117-146. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2015-367-285

Gozálvez, V. (2013). Ciudadanía mediática. Una mirada educativa. Madrid: Dykinson.

Gozálvez-Pérez, V., González-Fernández, N., & Caldeiro-Pedreira. M.C. (2014). La competencia mediática del profesorado: un instrumento para su evaluación. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 16(3), 129-146. (http://goo.gl/x3UD69) (2015-11-19).

Gütl, C., & Chang, V. (2009). Ecosystem-based Theorical Models for Learning in Environments of the 21st Century. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 7, 1-11. (http://goo.gl/IhZOwg) (2015-12-14).

Huber, G.L., & Gürtler, L. (2013). Aquad 7. Manual del programa para analizar datos cualitativos. Tübingen: Softwarevertrieb.

Ismail, J. (2001). The Design of an e-Learning System beyond the Hype. Internet and Higher Education, 4(3-4) 329-336. (http://goo.gl/rqLPzA) (2015-12-17).

Kolloffel, B., Eysink, T., & Jong, T. (2011). Comparing the Effects of Representational Tools in Collaborative and Individual Inquiry Learning. Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 6, 223-235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-011-9110-3

León, B., & Latas, C. (2005). Nuevas exigencias en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje del profesor universitario en el contexto de la convergencia europea: la formación en técnicas de aprendizaje cooperativo. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 8(6), 45-48. (http://goo.gl/h3hT6l) (2015-11-18).

Monereo, C. (2009). Pisa como excusa. Repensar la evaluación para cambiar la enseñanza. Barcelona: Graó.

Ramsden, P., Martin, E, & Bowden, J. (1989). School environment and sixth form pupils' approaches to learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 59(2), 129-142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1989.tb03086.x

Rodríguez-Martín, A., & Álvarez-Arregui, E. (2014). Estudiantes con discapacidad en la Universidad. Un estudio sobre su inclusión. Revista Complutense de Educación 25(2), 457-479. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_RCED.2014.v25.n2.41683

Sánchez, J., & Contreras, P. (2012). De cara al prosumidor. Producción y consumo empoderando a la ciudadanía 3.0. Icono 14, 10(3), 62-84. https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v10i3.210

Sánchez-Gómez, M.C., & García-Valcárcel, A. (2002). Formación y profesionalización docente del profesorado universitario. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 20(1), 153-171. (http://goo.gl/1sJr9n) (2016-11-30).

Senge, P.M. (1990). The Fifth Discipline. The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York: Dobuleday.

Shimaa, O., Nasr, M., & Helmy, Y. (2011). An Enhanced E-Learning Ecosystem Based on an Integration between Cloud Computing and Web 2.0. International Conference on Digital Ecosystems and Technologies. Seoul: Dejeon.

Shrivastava, P. (1998). Knowledge Ecology: Knowledge Ecosystems for Business Education and Training. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press.

Tello, J., & Aguaded, I. (2009). Desarrollo profesional docente ante los nuevos retos de las Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación en los centros educativos. Pixel-Bit, 34, 31-47. (http://goo.gl/IpE3Oy) (2016-11-08).

Toffler, A. (1980). La tercera ola. Barcelona: Plaza & Janes.

Uden, L., Wangsa, I.T., & Damiani, E. (2007). The Future of e-Learning: E-learning Ecosystem. Digital EcoSystems and Technologies Conference, 7, 113 -117. https://doi.org/10.1109/DEST.2007.371955

Zabalza, M.A. (2002). La enseñanza universitaria. El escenario y sus protagonistas. Madrid: Narcea.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

En una sociedad mediática y globalizada, con un desarrollo sin precedentes de la tecnología, las instituciones de educación superior están adaptando sus modelos de formación para hacer frente a este nuevo desafío. Este estudio tuvo por objetivo conocer la autopercepción del alumnado sobre su competencia mediática y determinar la influencia diferencial de un modelo ecosistémico de formación que se está implementando de manera experimental. La metodología de investigación combina el análisis cuantitativo (descriptivo e inferencial) con el cualitativo (análisis de contenido). Un total de 808 estudiantes universitarios matriculados en el curso 2015-16 en diferentes instituciones y países (Facultad de Formación del Profesorado y Educación, y Facultad de Economía y Empresa de la Universidad de Oviedo (España) y el Instituto Tecnológico Nacional de México) cumplimentaron un cuestionario sobre competencia mediática y realizaron informes abiertos sobre su experiencia con modelos ecosistémicos. Los resultados mostraron que el alumnado universitario tiene una autopercepción favorable sobre su nivel de competencia mediática y considera importante su desarrollo a través de un aprendizaje transversal con modelos de formación ecosistémicos. También emergen diferencias significativas entre las titulaciones y países cuando se utiliza este enfoque en el desarrollo de las asignaturas. En conclusión, el estudio avala que estos modelos favorecen los procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje en la universidad cuando la tecnología se adapta a las necesidades, intereses y capacidades de las personas mejorando, por tanto, su competencia mediática.

1. Introducción

La sociedad, la educación y la universidad se ven abocadas a reinterpretar sus relaciones en cada momento histórico con base en las prioridades que se determinen como apropiadas por parte de aquellas entidades, gobiernos, compañías o grupos de presión que tienen capacidad de decisión sobre los recursos disponibles para responder a las necesidades o demandas de la ciudadanía, en general, y de las organizaciones y los profesionales, en particular.

Si asumimos esta argumentación aceptamos que la sociedad está en constante transformación (Toffler, 1980) por su carácter informacional (Castells, 1999) y líquido (Area, 2012) y que la comunicación afecta a los ejes básicos de las personas en sus ámbitos social, laboral, político, económico, cultural y personal, lo que hace necesario que las instituciones educativas proporcionen modelos de formación coherentes para que la ciudadanía sea competente en un entorno mediático donde la televisión, el cine, la radio, la prensa, los ordenadores, las redes sociales, las tablets, los videojuegos o los teléfonos móviles forman parte de la vida cotidiana (Fedorov, 2014; Gozálvez, 2013). En este contexto mediático globalizado los usuarios de esta tecnología deben tener una alfabetización continuada que les ayude a ser «prosumidores competentes» (Caldeiro-Pedreira & Aguaded, 2015; Sánchez & Contreras, 2012) porque las herramientas tecnológicas emergen y evolucionan en una espiral constante que exige de las personas un análisis crítico y ético de un escenario en donde son receptores y productores de mensajes.

En el proceso de construcción del Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior (EEES) las universidades han tenido en cuenta esta situación y diseñan entornos de trabajo desplegando estrategias diferenciales interconectadas en función de sus objetivos, de sus posibilidades y del perfil de sus usuarios. El problema es que sus intenciones no se traducen en la práctica linealmente porque afloran múltiples problemáticas en los procesos de implementación (Ferrés & Masanet, 2015) fruto de las fricciones que se generan con las culturas organizativas y funcionales de las facultades, escuelas y departamentos dado que se encuentran cargadas de significados sociales, culturales y políticos que tamizan las prescripciones externas para adecuarlas a intereses de distinto signo.

A pesar de todo, no puede negarse que han sido muchos los avances aportados desde la investigación destacando, entre otros, la importancia que se atribuye al sujeto que aprende (León & Latas, 2005); el contexto del aula (Entwistle & Tait, 1990); el entorno institucional (Ramsden, Martin, & Bouden, 1989); la competencia pedagógica (Sánchez-Gómez & García-Valcárcel, 2002); el currículum (Gimeno-Sacristán, 2001; 2008); la tecnología y las redes sociales (García-Galera, 2013); la colaboración (Kolloffel, Eysink, & Jong, 2011); las metodologías activas (Cano, 2009); los planes de estudio (Zabalza, 2002); los procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje (Carrascosa, 2005); la evaluación formativa (Monereo, 2009); los modelos organizativos (Buckland, 2009) y la educación mediática. Sus conclusiones hacen necesario reflexionar, de manera fundamentada y serena, sobre cómo mejorar la calidad de la docencia en la universidad partiendo de la experiencia disponible y atendiendo a la necesidad de potenciar una educación mediática transversal y longitudinal «que supere la visión excesivamente tecnológica e instrumental que fruto de las modas y los avances tecnológicos, a menudo ha confundido a políticos, administradores y sociedad en general y ha distorsionado e ignorado las inherentes características y cualidades que los medios tienen de cara a la educación» (Aguaded, 2012: 260). Este contexto enmarca el contenido central de este artículo que presenta un recorrido por los ecosistemas de formación «blended-learning» en los que venimos trabajando en los últimos años (Álvarez-Arregui & Rodríguez-Martín, 2013) al considerarlos como una alternativa viable para transitar desde una sociedad informacional hacia una sociedad del conocimiento mediática e inclusiva (DeJaeghere, 2009; Rodríguez-Martín & Álvarez-Arregui, 2014).

1.1. Ecosistemas de formación en la docencia universitaria

Los ecosistemas de formación en la educación superior son relativamente recientes, si bien, son muchas las experiencias innovadoras que están promoviendo relaciones dinámicas y de colaboración entre los miembros de las comunidades. Entre otras propuestas destacan el ecosistema modular (Dimitrov, 2001); el ecosistema del conocimiento (Shrivastava, 1998); el ecosistema e-learning de gestión y apoyo al aprendizaje (Ismail, 2001); el ecosistema e-learning para la gobernanza (Chang & Lorna, 2008) o el ecosistema de aprendizaje (LES) de Gült y Chang (2009). Estos modelos incorporan un diseño de aprendizaje, unos recursos humanos, una formación para el desarrollo de competencias básicas, un sistema de comunicación y diferentes aplicaciones (Shimaa, Nasr, & Helmy, 2011). Aunque coincidimos con sus postulados básicos, consideramos, al igual que otros autores, que deben analizarse los peligros derivados de un excesivo desplazamiento hacia el e-learning (Uden, Wangsa, & Damiani, 2007) porque se pueden desaprovechar las potencialidades comunicativas que brindan las tecnologías en la enseñanza presencial por lo que preferimos situarnos en modelos blended-learning.

1.2. Un ecosistema de formación para aprender a emprender (ECOFAE)

Atendiendo a los referentes citados, estamos desarrollando un modelo desde la Universidad de Oviedo que aplicamos en proyectos de formación en los ámbitos educativos, sociales y laborales así como en proyectos de innovación e investigación (Gráfico 1) que tienen por objeto desarrollar comunidades profesionales de aprendizaje interconectadas, cohesionadas y autogestionables en instituciones nacionales e internacionales. La construcción del ecosistema es el resultado de plantear y planificar una estructura de referencia flexible y dinámica que se perfeccione continuamente gracias a los diagnósticos, las evaluaciones y la investigación. El diseño básico del modelo tiene cinco fases:

– Fase I. Planificación y diagnóstico. Se preparan los instrumentos que nos proporcionan información al principio y al final del proceso para determinar las necesidades y el impacto de la intervención educativa. El alumnado cumplimenta cuestionarios diversos (hábitos de estudio, competencia comunicativa y digital, estilos de aprendizaje, etc.).

– Fase II. Diseño del contexto de formación. Se articula alrededor de dos espacios, el virtual y el presencial. El entorno virtual adopta una estructura modular, escalable y adaptable (Gráfico 2):

• Módulo de información. Aquí incorporamos documentación de la titulación, el programa oficial de la asignatura y la bibliografía general y un foro de novedades.

• Módulo de comunicación. En este módulo se integran todas las herramientas de comunicación disponibles (foro, Skype, blog, Facebook, Twitter, etc.).

• Módulo de diagnóstico. Los elementos permiten al alumnado conocer sus estilos de aprendizaje, hábitos de estudio, competencia mediática y conocimientos previos. En Dropbox, Google Calendar… y en foros generales se recogen las expectativas y las percepciones sobre las asignaturas que se contrastarán a final de curso.

• Módulo de contenidos teóricos. Aquí se incluyen un guion general de los contenidos, esquemas, enlaces, referencias bibliográficas, presentaciones (Powerpoint, Prezzi…) para que accedan a ellas todos los participantes (alumnado y profesionales).

• Módulo de prácticas. Se plantean actividades individuales, de grupo, presenciales y virtuales.

• Módulo de autogestión y apoyo al aprendizaje. Aquí se incluye un banco de recursos y buenas prácticas.

• Módulo de investigación y evaluación del impacto. Aquí se presentan las evaluaciones externas oficiales que se realizan por la Unidad Técnica de Calidad de la Universidad de Oviedo y evaluaciones internas donde se recogen informaciones aportadas en los foros, en los blogs, en redes sociales, en los debates de aula y en las investigaciones.

– Fase III. Despliegue del modelo de aprendizaje. Se realiza a través de cuatro sistemas:

• Sistema de registro e información.

• Sistema de tutoría y asesoramiento.

• Sistemas de relaciones y comunicación.

• Sistema de autogestión del aprendizaje.

– Fase IV. Evaluación para la mejora. Este módulo se articula en tres secciones:

• Primera. Muestra los resultados de las evaluaciones que se hacen desde la Unidad Técnica de Calidad de la Universidad de Oviedo.

• Segunda. Recoge las opiniones públicas (blogs, foros, Facebook, Twitter…) que manifiestan los estudiantes sobre las metodologías que se van implementando.

• Tercera. Compara el diagnóstico inicial de los perfiles de los participantes con su situación a final del semestre se determina su grado de satisfacción con el ecosistema de formación y las competencias adquiridas.

– Fase V. Investigación del impacto y transferencia. Se hacen investigaciones periódicas sobre los procesos, los resultados y el diseño del modelo.

Atendiendo a este diseño, presentamos este trabajo donde queremos determinar qué autopercepción tiene el alumnado sobre su competencia mediática y analizar el grado de influencia que en ella tienen los ecosistemas blended-learning como modalidad formativa. En concreto, queremos: 1) Conocer la competencia mediática autopercibida del alumnado universitario participante; 2) Valorar qué indicadores de la competencia mediática tienen mayor importancia para los estudiantes; 3) Determinar la incidencia de los ecosistemas de formación en la competencia mediática autopercibida; 4) Analizar el valor que atribuye el alumnado a los ecosistemas de formación.

2. Materiales y métodos

2.1. Participantes

El estudio empírico se desarrolló en España y en México a través de encuestas. En el caso español en la Universidad de Oviedo en el Grado de Pedagogía (n=122) y en el Grado Maestro en Educación Primaria (n=182), impartidos en la Facultad de Formación del Profesorado y Educación; así como en el Grado de Administración de Empresas (n=192) impartido en la Facultad de Economía y Empresa. En el caso mexicano en el Instituto Tecnológico de México (Michoacán) en el Grado de Ingeniería de Gestión Empresarial (n=105), en el Grado de Ingeniería Industrial (n=114) y en el Grado de Ingeniería Eléctrica (n=103).

El colectivo objeto de encuesta, a partir de un muestreo no probabilístico, fue de 808 estudiantes de segundo y tercer curso lo que supone un 53,7% de los 1.505 estudiantes matriculados en el curso 2015-16 en las dos instituciones participantes. En este proceso de investigación también se cumplimentaron 118 informes por estudiantes de los Grados de Pedagogía y Maestro de la Facultad de Formación del Profesorado y Educación de la Universidad de Oviedo (España; n=60) y de los Grados de Ingeniería Industrial e Ingeniería Eléctrica del Instituto Tecnológico (México; n=58) que participaron en la implementación del modelo ecosistémico de formación para el desarrollo de la competencia mediática.

2.2. Instrumentos y procedimiento

El instrumento utilizado para valorar la competencia mediática fue un cuestionario (77 ítems) ya validado estadísticamente (Gozálvez-Pérez, González-Fernández, & Caldeiro-Pedreira, 2014) mientras que para conocer la satisfacción con el modelo de formación se utilizó una escala propia (20 ítems) y validada en investigaciones internacionales previas (Álvarez-Arregui & Rodríguez-Martín, 2013). Estos instrumentos, aplicados entre octubre de 2015 y enero de 2016, se presentaron de manera integrada a los participantes en cuatro apartados (97 ítems):

• Perfil de participante (37 ítems): género, titulación, facultad, tipo de centro donde cursó bachillerato, trayectoria académica, dominio de idiomas, el conocimiento de programas informáticos, tiempo y uso del ordenador y el móvil para el estudio y el ocio.

• Competencia mediática autopercibida (29 ítems), con rango de respuesta de 4 puntos: 1 (muy baja), 2 (baja), 3 (media), y 4 (alta).

• Importancia que atribuyen a distintas competencias relacionadas con la educación mediática (11 ítems), con rango de respuesta de 4 puntos: 1 (nada importante) 2 (importancia baja), 3 (importancia media) 4 (importancia alta).

• Diseño del ecosistema de formación, de sus herramientas y de su influencia en el desarrollo de la competencia mediática (20 ítems), con rango de respuesta de 4 puntos: 1 (nada), 2 (poco), 3 (bastante), 4 (mucho).

El error muestral es del 5,5% (95%) y el nivel de confianza Z=1.96; p=q=0,5 (95%). El nivel de fiabilidad se estableció mediante el alfa de Cronbach (.916); la correlación entre formas (.592), Coeficiente Spearman-Brown (.770) y las Dos mitades de Guttman (.759). La validez se ha determinado a través de tres revisiones internas de expertos, dos profesores de la Universidad de Oviedo, una profesora de la Universidad de Cantabria y un profesional experto internacional de Lausanne (Suiza).

Las informaciones cuantitativas proporcionadas por los ítems de los cuestionarios fueron tratadas con el programa SPSS 19 para los siguientes estudios: análisis de fiabilidad; análisis de frecuencias; diferencias de medias (T-Test para muestras independientes, utilizando los estadísticos T de Student y el Test de Levene para estimar la igualdad de varianzas) y análisis de varianza (Anova y test a posteriori de Scheffé con el subprograma oneway).

Los datos cualitativos se generaron a partir de los comentarios realizados por los estudiantes en las preguntas abiertas en los tres grados y en 118 informes abiertos que realizaron los estudiantes de Pedagogía y Maestro. El análisis de contenido se realizó con el programa Aquad 7.0 (Huber & Gürtler, 2013). La información cualitativa se ha transcrito y exportado al programa y los análisis realizados se han orientado a reducir/agrupar información a través de búsqueda de palabras clave, elaboración de segmentos de significado, catalogación, vinculación y cruces de códigos. Los comentarios que ilustran las argumentaciones se identifican con una codificación específica.

3. Análisis y resultados

3.1. Competencia mediática autopercibida

Los estudiantes valoran, de manera generalizada, su competencia mediática como adecuada, si bien deben hacerse matizaciones. Como colectivo se consideran capacitados (79%) para valorar las tendencias sociopolíticas en los medios de comunicación de mayor difusión, comunicarse en los medios utilizando un lenguaje diferente en función del destinario (50%) y la finalidad del mensaje (46%) así como para utilizar la tecnología en su proceso de aprendizaje.

Estas percepciones generales deben matizarse si se tiene en cuenta que solo un 23,4% son capaces de diferenciar claramente los diferentes códigos utilizados por el emisor en los mensajes que reciben de los medios, más de un tercio (30,6%) considera que su competencia mediática tiene un nivel adecuado para convivir con los medios tecnológicos y, en menor porcentaje, son capaces de interpretar y producir mensajes de manera crítica, responsable y creativa así como utilizar programas para editar secuencias de imágenes y crear vídeos.

En general, diferencian las fuentes de información fiables de las que no lo son. Sus carencias las asocian con el desconocimiento sobre la existencia y/o finalidad de los consejos audiovisuales, la legislación que protege a los usuarios en la producción de contenidos en medios y la propiedad intelectual. Destaca su interés por la actualización tecnológica y comunicativa cuando pueden aplicarlas a las tareas académicas de ahí que debería aprovecharse esta predisposición en este entorno.

Una gran mayoría de estudiantes valoran positivamente la importancia de la competencia mediática en la sociedad (53,2%) y la gestión de información (42,7%) pero reconocen sus riesgos (56,9%) de ahí que se pronuncien positivamente a su consumo ético y responsable. Reconocen las ventajas de la utilización de los medios en la vida cotidiana (40,3%) pero no les conceden tanta importancia a nivel personal y social (28,4%) para utilizar las TIC, técnica o críticamente, porque consideran que es suficiente poder desenvolverse con ellas como consumidores de manera habitual. Por ello, no les preocupa en exceso ser «prosumer» (26,6%) o intentar comprender las estructuras y superestructuras de los medios.

Las diferencias significativas encontradas en cuanto al género indican que los hombres se comunican mejor en función del destinatario (.017). Cuando han cursado el bachillerato en centros públicos (.018), utilizan, en mayor medida, programas informáticos para editar secuencias de imágenes y crear vídeos (.015) y distinguen tendencias sociopolíticas en los medios (.015).

Los conocimientos sobre los Consejos Audiovisuales son superiores en los hombres (.031) mientras que las mujeres disponen de más información sobre la normativa reguladora de la propiedad intelectual (.021). Los estudiantes con peor trayectoria académica, muestran una mayor despreocupación por mantenerse al día sobre los nuevos recursos tecnológicos y comunicativos que puedan aplicar en sus tareas académicas (.004).

El uso del ordenador para el estudio y el ocio genera diferencias. En el primer caso, nos encontramos una correlación negativa donde, el menor uso de herramientas tecnologías se relaciona con una mayor predisposición a apoyarse en los medios de comunicación clásicos (.000) y se muestran más desvinculados de los nuevos medios tecnológicos (.013). En cambio, los que utilizan ordenadores más de tres horas al día diferencian mejor los lenguajes en función de la finalidad de los mensajes (.033), se apoyan más en los actuales medios de comunicación (.002) y distinguen mejor las tendencias sociopolíticas de los medios (.009). En aquellos estudiantes que utilizan más de tres horas el ordenador para el ocio existe una correlación positiva con su competencia mediática en diez de los dieciséis ítems considerados lo que pone en valor este aspecto.

3.2. Importancia de la competencia mediática

Los estudiantes indican que es importante conocer los riesgos de Internet y de los medios en sus relaciones sociales por lo que se debe asumir su importancia en la sociedad cuando se gestiona adecuadamente la información que proporcionan. También informan, aunque en menor medida, sobre la necesidad de ser «prosumer» para utilizar los medios de manera responsable, acceder a información relevante y relacionarse personal, social y profesionalmente. En cualquier caso, hay clústeres a los que no les preocupa comprender las superestructuras de los medios o ser «prosumer» lo que se relaciona con desconocimiento, carencias y oposición.

Las diferencias significativas encontradas indican que los estudiantes de Ingeniería Empresarial (.017) atribuyen más importancia a los medios de comunicación en la sociedad pero conceden menos a la búsqueda de información transcendente para su vida (.002), a ser «prosumer» (.000) y a consumir los medios de manera ética y responsable (.028). Los que han estudiado el bachillerato en centros concertados otorgan menos valor a los medios en su vida personal y social (.001) y los que tienen una trayectoria excelente están interesados en comprender las estructuras y superestructuras de los medios (.022), a buscar información transcendente para sus vidas (.017), a consumir los medios de manera ética y responsable (.000) y a ser prosumidores (.013).

En cuanto al uso del ordenador y del teléfono móvil para el estudio y el ocio se ratifica, en todas las diferencias significativas encontradas, una correlación positiva entre un mayor uso de estas herramientas y un incremento de la importancia que se atribuye hacia la educación mediática.

3.3. Valoraciones del ecosistema de aprendizaje (ECOFAE)

Los 118 informes elaborados por los estudiantes y las preguntas abiertas de los 808 cuestionarios generaron 2.400 párrafos con 73.425 palabras de los que se hizo un análisis de contenido (Tabla 4) (página siguiente).

– Catálogo 1. Fortalezas. Emergen 340 codificaciones. Los aspectos que destacan como más positivos son los proyectos asociados a contenidos concretos del temario o vinculados a proyectos reales de colaboración con centros socioeducativos (relaciones interinstitucionales). En la misma dirección apuntan las visitas pedagógicas, el incremento de la participación con metodologías activas de trabajo en el aula y a través de las herramientas disponibles en el campus y en la Web 2.0, el trabajo en equipo, el tratamiento de la información en múltiples formatos, la innovación, la creatividad, la colaboración y el enfoque constructivista que se adopta por parte del profesorado.

• «La técnica de la bola de nieve me ha parecido muy innovadora porque hemos comprobado que a medida que compartimos lo que sabemos con el compañero, con el grupo, con la clase y desde el blog y Twitter nos permite ampliar lo que sabemos y que se comente en las redes sociales» (I.12.M.P.M.P.).

• «El trabajo por proyectos favorece la colaboración entre compañeros, el ecosistema que se genera es una forma novedosa de poder colaborar unos con otros, de aprender unos de otros… un ejemplo lo tenemos cuando compartimos imágenes en Twitter, cuando hacemos entradas en el blog subimos todo tipo de materiales que siempre tenemos a nuestra disposición» (I.6.M.PR.P.).

• «El proyecto que presentó un grupo donde invitaron a otras profesoras y a los estudiantes de primero, donde cambiamos de aula según las actividades, donde se presentaron canciones, donde se hicieron performances, donde se grababa todo lo que pasaba y se subía directamente a Twitter y al blog me pareció un ejemplo muy claro de que las cosas pueden cambiarse» (I.4.H.PR.P.).

– Catálogo 2. Debilidades. Emergen 140 segmentos que hacen referencia a la dificultad para debatir al final de las sesiones, el tiempo de presentación de los proyectos, los contenidos abordados y la baja coordinación del profesorado.

La presentación del ecosistema les genera una cierta ansiedad inicial pues implica un cambio en la forma en la que se interpreta comúnmente la relación didáctica, si bien son conscientes que este enfoque exigen la asunción de un mayor compromiso individual, de equipo, de colectivo y de desarrollo de actitudes proactivas para desplegar metodologías innovadoras, creativas y corresponsables mediadas por las TIC.

• «La pega que le pongo al ecosistema de formación es que no hay mucha coordinación con otras asignaturas y tampoco veo que el decano apoye estas acciones porque siempre hay problemas para hacer salidas por ejemplo» (I.7M.PR.P.).

• «La forma de trabajar es diferente, te toca la fibra sensible ya que cuando ves las imágenes de lo que haces en clase, de los viajes pedagógicos, de las actividades fuera del aula… no sé cómo explicarlo es diferente» (C.55.M.PR.M.).

• «La metodología que se utiliza para presentarnos, para hablar en público desde cualquier parte de la clase, el que te apoyen los compañeros si te quedas en blanco… todas estas cosas te hacen ir cogiendo seguridad en ti misma y valorar los apoyos que te proporcionan tus compañeros» (I.21.M.PR.P.).

– Catálogo 3. Mejoras. Emergen 240 códigos. Destacan la necesidad de incrementar el respaldo institucional al desarrollo de proyectos, orientarlos al entorno laboral y al aprendizaje por servicio, dejar mayor libertad en la elección de los equipos y los proyectos, desarrollar cursos de formación cuando sea necesario y cambiar las tutorías grupales tal como están planteadas por lo que podría utilizarse el día dedicado a ellas a compartir experiencias con otras clases o bien a visitar centros con buenas prácticas. La triangulación de la evaluación, las videoconferencias, las mesas redondas con estudiantes egresados, los debates públicos o la solución de los problemas con la tecnología son otras demandas necesarias y lógicas si se quieren implementar los ecosistemas de formación de manera generalizada.

• «Como estudiante presencial me gustaría poder participar en el aprendizaje por servicio, al menos, a través de las herramientas tecnológicas» (I.16.H.NP.P.).

• «Tanto yo como algunas de mis compañeras hemos tenido problemas al principio para adaptarnos y trabajar con las herramientas del ecosistema ya que desconocíamos algunas de ellas. Sería bueno que nos formasen previamente» (I.42.M.PR.P.).

• «Los trabajos que hemos hecho dentro del ecosistema nos podrían ser más útiles si nuestros profesores se coordinasen más y tuviéramos acceso a más prácticas y contactos con profesionales a través de las redes sociales» (I.33.M.PR.M.).

4. Discusión y conclusiones

Los resultados obtenidos ponen de relieve que los ecosistemas de formación blended-learning desarrollan la competencia mediática en los estudios de Grado y tienen buena acogida por el alumnado. Se presentan como una apuesta atractiva que requiere una alta inversión de energía en tiempo y dedicación inicial pero proporciona beneficios asociados al desarrollo de la competencia profesional, a la interdisciplinariedad y a la alfabetización mediática. La implementación del modelo se avala desde la mejor autopercepción que tienen los estudiantes sobre su capacitación mediática y por la importancia que conceden a la necesidad de potenciar la alfabetización en este campo de conocimiento como competencia transversal en los estudios universitarios por lo que debería ser respaldada institucionalmente en los planes de estudio para integrarse en las culturas organizativas y responder a las necesidades de los usuarios, a los profesionales y a la sociedad coincidiendo con las aportaciones de otros autores (Tello & Aguaded, 2009). Las diferencias encontradas entre titulaciones y facultades evidencian una buena autopercepción de los estudiantes sobre su competencia mediática en línea con otras investigaciones (González-Fernández, Gozálvez-Pérez, & Ramírez-García, 2015) que destacan el impacto positivo de las metodologías activas y el uso de tecnologías digitales en el desarrollo de esta competencia.

La sobrevaloración que concede el alumnado a su competencia mediática es el resultado de su visión restringida acerca de la utilización de herramientas y programas para relacionarse e informase, ya que estos hechos no suponen una verdadera alfabetización que los convierta en prosumidores integrales. El estudio muestra una correlación positiva donde se evidencia que a más tiempo de uso de equipos informáticos y teléfonos móviles para las tareas curriculares y para el ocio, mejor es la autopercepción sobre la competencia mediática. Lo mismo sucede cuando desarrollan proyectos en grupo apoyándose en los principios que guían los ecosistemas de formación ya que los procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje blended-learning que se generan favorecen la competencia mediática, la generación de comunidades profesionales y la relación con el mercado laboral.

El ecosistema de formación orientado al desarrollo de la competencia mediática incrementa la satisfacción de los usuarios, independientemente de las exigencias iniciales que conlleva. Su potencial se expande cuando se integran en la cultura organizativa bajo el apoyo institucional tal y como indican otros autores (Gewerc, Montero, & Lama, 2014; Senge, 1990). La planificación, el diseño, las metodologías, los recursos, las tareas y el compromiso de los promotores inciden positivamente en los participantes cuando trabajan proyectos con base tecnológica orientados a la educación mediática (García-Ruiz, Ramírez-García, & Rodríguez-Rosell, 2014).

Las problemáticas detectadas nos hacen estar alerta para desarrollar propuestas de mejora continua que deben convertirse en el referente que guíe la construcción de futuros ecosistemas. Por lo tanto, deberán atenderse las necesidades de formación previa de los usuarios –profesorado, profesionales y estudiantes-, las infraestructuras, la mejora de los sistemas de evaluación, los mecanismos de coordinación dentro y fuera de nuestras instituciones y el respaldo institucional si se quieren promover ecosistemas de formación blended-learning de manera coherente e integral.

El despliegue de los ecosistemas de formación mediados por la tecnología es de hondo calado pero puede orientar los procesos de cambio en aquellas instituciones de Educación Superior donde la ambigüedad de objetivos, el desacoplamiento y la diversidad de intereses priman sobre la colaboración, la innovación y la mejora continua. El objetivo de la educación en el siglo XXI es formar generaciones de ciudadanos en competencia mediática lo que conlleva incorporar en el currículo de manera transversal un proceso de alfabetización para todas las personas a lo largo de su vida para que sean plenamente competentes en el acceso, interpretación y reutilización de las variadas y múltiples formas digitales de representación de la información y el conocimiento.

Apoyos

Este artículo se ha realizado en el marco del Proyecto de Investigación «Diseño, implementación y evaluación internacional de ecosistemas de formación blended-learning en la Educación Superior (cód. PAIN1-10-001)», concedido por la Universidad de Oviedo y ha contado con el asesoramiento de la Plataforma de Aceleración de la Innovación «Innobridge» con sede en Lausanne (Suiza).

Referencias

Aguaded. I. (2012). La competencia mediática, una acción educativa inaplazable. [Media Proficiency, an Educational Initiative that Cannot Wait]. Comunicar, 39, 7-8. https://doi.org/10.3916/C39-2012-01-01

Álvarez-Arregui, E., & Rodríguez-Martín, A. (2013). Gestión de la formación en las organizaciones desde una perspectiva de cambio. Principios básicos y estrategias de intervención. Oviedo: Ediuno.

Area, M. (2012). Sociedad líquida, Web 2.0 y alfabetización digital. Aula de Innovación Educativa, 212, 55-59.

Buckland, R. (2009). Private and Public Sector Models for Strategies in Universities. British Journal of Management, 20(4), 524-536. (http://goo.gl/bPvxVt) (2016-11-25).

Caldeiro-Pedreira, M.C., & Aguaded, I. (2015). Alfabetización comunicativa y competencia mediática en la sociedad hipercomunicada. Revista Digital de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria, 9(1), 37-56. https://doi.org/10.19083/ridu.9.379

Cano, R. (2009). Tutoría universitaria y aprendizaje por competencias ¿cómo lograrlo? Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 12, 181-204. (http://goo.gl/SwlBry) (2015-11-11).

Carrascosa, J. (2005). La evaluación de la docencia en los planes de mejora de la Universidad. Educación XXI, 8, 87-101. (http://goo.gl/J5E1gP) (2015-10-04).

Castells, M. (1999). La era de la información. Fin de milenio. Madrid: Alianza.

Chang, V., & Lorna, U. (2008). Governance for e-learning Ecosystem. In E. Chang, & F. Hussain (Ed.), II IEEE International Conference on Digital Ecosystems and Technologies, 340-345. Phitsanulok (Thailand): Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

DeJaeghere, J. (2009). Critical Citizens Education for Multicultural Societies. Interamerican Journal of Education and Democracy, 2(2), 223-236. (https://goo.gl/XxOUBT) (2015-11-22).

Dimitrov, V. (2001). Learning Ecology for Human and Machine Intelligence: A Soft Computing Approach. Studies in Fuzziness and Soft Computing, 81, 386-393. (http://goo.gl/TgXmvW) (2016-11-01).

Entwistle, N., & Tait, H. (1990). Approaches to Learning, Evaluations of Teaching, and Preferences for Contrasting Academic Environments. Higher Education, 19, 169-194. (http://goo.gl/MKbfrs) (2016-08-09).

Fedorov, A. (2014). Media Education Literacy in the World: Trends. European Researcher, 67(1-2), 176-187. https://doi.org/10.13187/issn.2219-8229

Ferrés, J., & Masanet, M.J. (Coords.) (2015). La educación mediática en la universidad española. Barcelona: Gedisa.

García-Galera, M.C. (2013). Twittéalo: la Generación Y su participación en las redes sociales. Crítica, 985, 34-37. (http://goo.gl/5DbdM9) (2015-11-27).

García-Ruiz, R., Ramírez-García, A., & Rodríguez-Rosel. M. (2014). Educación en alfabetización mediática para una nueva ciudadanía prosumidora. [Media Literacy Education for a New Prosumer Citizenship]. Comunicar, 43, 15-23. https://doi.org/10.3916/C43-2014-01

Gewerc, A., Montero, L., & Lama, M. (2014). Colaboración y redes sociales en la enseñanza universitaria [Collaboration and Social Networking in Higher Education]. Comunicar, 42, 55-63. https://doi.org/10.3916/C42-2014-05

Gimeno-Sacristán, J. (2001). Educar y convivir en la cultura global. Madrid: Morata.

Gimeno-Sacristán, J. (2008). Educar por competencias. ¿Qué hay de nuevo? Madrid: Morata.

González-Fernández, N., Gozálvez-Pérez, V., & Ramírez-García, A. (2015). La competencia mediática en el profesorado no universitario. Diagnóstico y propuestas formativas. Revista de Educación, 327, 117-146. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2015-367-285

Gozálvez, V. (2013). Ciudadanía mediática. Una mirada educativa. Madrid: Dykinson.

Gozálvez-Pérez, V., González-Fernández, N., & Caldeiro-Pedreira. M.C. (2014). La competencia mediática del profesorado: un instrumento para su evaluación. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 16(3), 129-146. (http://goo.gl/x3UD69) (2015-11-19).

Gütl, C., & Chang, V. (2009). Ecosystem-based Theorical Models for Learning in Environments of the 21st Century. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 7, 1-11. (http://goo.gl/IhZOwg) (2015-12-14).

Huber, G.L., & Gürtler, L. (2013). Aquad 7. Manual del programa para analizar datos cualitativos. Tübingen: Softwarevertrieb.

Ismail, J. (2001). The Design of an e-Learning System beyond the Hype. Internet and Higher Education, 4(3-4) 329-336. (http://goo.gl/rqLPzA) (2015-12-17).

Kolloffel, B., Eysink, T., & Jong, T. (2011). Comparing the Effects of Representational Tools in Collaborative and Individual Inquiry Learning. Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 6, 223-235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-011-9110-3

León, B., & Latas, C. (2005). Nuevas exigencias en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje del profesor universitario en el contexto de la convergencia europea: la formación en técnicas de aprendizaje cooperativo. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 8(6), 45-48. (http://goo.gl/h3hT6l) (2015-11-18).

Monereo, C. (2009). Pisa como excusa. Repensar la evaluación para cambiar la enseñanza. Barcelona: Graó.

Ramsden, P., Martin, E, & Bowden, J. (1989). School environment and sixth form pupils' approaches to learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 59(2), 129-142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1989.tb03086.x

Rodríguez-Martín, A., & Álvarez-Arregui, E. (2014). Estudiantes con discapacidad en la Universidad. Un estudio sobre su inclusión. Revista Complutense de Educación 25(2), 457-479. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_RCED.2014.v25.n2.41683

Sánchez, J., & Contreras, P. (2012). De cara al prosumidor. Producción y consumo empoderando a la ciudadanía 3.0. Icono 14, 10(3), 62-84. https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v10i3.210

Sánchez-Gómez, M.C., & García-Valcárcel, A. (2002). Formación y profesionalización docente del profesorado universitario. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 20(1), 153-171. (http://goo.gl/1sJr9n) (2016-11-30).

Senge, P.M. (1990). The Fifth Discipline. The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York: Dobuleday.

Shimaa, O., Nasr, M., & Helmy, Y. (2011). An Enhanced E-Learning Ecosystem Based on an Integration between Cloud Computing and Web 2.0. International Conference on Digital Ecosystems and Technologies. Seoul: Dejeon.

Shrivastava, P. (1998). Knowledge Ecology: Knowledge Ecosystems for Business Education and Training. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press.

Tello, J., & Aguaded, I. (2009). Desarrollo profesional docente ante los nuevos retos de las Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación en los centros educativos. Pixel-Bit, 34, 31-47. (http://goo.gl/IpE3Oy) (2016-11-08).

Toffler, A. (1980). La tercera ola. Barcelona: Plaza & Janes.

Uden, L., Wangsa, I.T., & Damiani, E. (2007). The Future of e-Learning: E-learning Ecosystem. Digital EcoSystems and Technologies Conference, 7, 113 -117. https://doi.org/10.1109/DEST.2007.371955

Zabalza, M.A. (2002). La enseñanza universitaria. El escenario y sus protagonistas. Madrid: Narcea.

Document information

Published on 31/03/17

Accepted on 31/03/17

Submitted on 31/03/17

Volume 25, Issue 1, 2017

DOI: 10.3916/C51-2017-10

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?