Abstract

The benefits of climate adaptation policy are sometimes underestimated because its nonuse values perceived by people indirectly affected are usually ignored. Using data from a representative sample of Beijing’s urban population, it is shown that people living at a distance perceive nonuse values of climate change adaptation measures aimed at improving the environmental conditions in the Tarim River Basin in Northwest China. Using the contingent valuation method the monetized benefit of a particular set of climate adaptation measures experienced by a Beijing household is approximated. It is concluded that not only the preferences of local people, but also of people living in other parts of China should be considered when deciding if a climate adaptation policy is worthwhile implementing from a social welfare point of view.

Keywords

climate policy ; Tarim River Basin ; cost-benefit analysis ; nonuse values ; contingent valuation method

1. Introduction

Climate policy measures can be roughly subdivided into mitigation measures and adaptation measures. Mitigation policy aims at a reduction of greenhouse gas emissions with the overall goal of slowing down climate change and global warming. Since greenhouse gases like CO2 , CH4 , etc., are global pollutants which have the same effect on world climate irrespective of where they are emitted, mitigation policy creates benefits for people all over the world. Adaptation policy on the other hand does not seek to influence the global climate but, instead, is meant to reduce the negative consequences of climate change for a specific region. The benefits created by adaptation policy are only of local importance while mitigation policy yields global benefits.

Mitigation and adaptation measures are usually financed out of public funds. Before implementing a particular project or policy, decision makers should make sure that this makes sense from a social point of view, i.e., that the social benefits accruing from such a project outweigh its costs. Comprehensive environmental cost-benefit analysis requires that all benefits accruing from a project are included [ Mitchell and Carson , 1989 ]. The fact that more people directly benefit from mitigation policy as compared to adaptation policy has consequences for the welfare economic appraisal of the former as compared to the latter. In practice, social benefits generated by a climate policy are calculated as the sum of changes in the utility of all households affected by this policy. As a consequence, social benefits depend both on the increase of wellbeing of individual households and on the number of households considered. Consequently, since the wellbeing of many more people worldwide is affected by mitigation measures than by adaptation measures, the former will always appear more attractive in a cost-benefit analysis than the latter, at least from a global perspective [ Hanley et al. , 1993 ].

There is a growing interest in assessing public views on climate change and of adaptation policies. Quantitative surveys on this topic have been carried out in many countries [ Ebi and Semenza, 2008 ; Lowe et al ., 2006 ; Luo et al ., 2009 ; Rebetez, 1996 ; Semenza et al ., 2008 ]. Deng et al ., 2011 ; Deng et al ., 2012 ], for instance, assessed public perceptions of climate change and adaptation measures in the Urumqi River Basin and the Aksu River Basin in Northwest China. The latter two studies focus on the preferences of the local population towards different adaptation measures. However, until now no attention has been paid to the quantification of benefits accruing from these measures also in other parts of China or even for China as a whole.

In this paper we want to show that adaption policy measures are often undervalued in cost-benefit analysis because only their so-called use values are considered, while the nonuse values they create are neglected. If it can be shown that some adaptation policy measures in the context of climate policy create also nonuse values in addition to the use values, this might lead to a new assessment of such measures and it might increase their chances of being approved in the political decision process [ Carson and Hanemann , 2005 ]. It is obvious that the systematic undervaluation of adaptation policy measures resulting from the neglect of nonuse values they create might have the consequence that they are declined because they do not pass the cost-benefit test, though they create high nonuse values which are not considered in this test [ Ahlheim , 2002 ]. Of course, the existence of nonuse values depends on the cultural background of the people affected by these measures and of the society they live in. Especially in an emerging country like China many people might still underestimate the importance of climate adaptation measures in comparison with economic policy measures triggering economic growth of the country, especially if the adaptation measures are conducted in faraway regions of the country [ Harris , 2006 ].

In this study we test empirically the hypothesis that also in a growth-oriented economy like China nonmaterialistic values like the nonuse values of climate policy are perceived and respected by the population. Since environmental awareness usually increases with education level [ Dunlap et al. , 2000 ], we suppose that nonuse values of climate policy are more likely to be perceived by the people living in big cities as compared to people living in remote areas. Therefore, we conduct a survey in Beijing where we ask people to assess a climate change adaptation project to be implemented in a faraway region, in this case in the Tarim River Basin in Xinjiang autonomous region. Of course, the population of Beijing is not representative for the Chinese population, but in the context of this study it serves as a suitable example for the people potentially benefiting from the nonuse value of climate adaptation policy in the Tarim River Basin. This approach can then be extended to other regions of China.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: the next section provides information concerning the impact of climate change on the Tarim area; section 3 introduces the theoretical concept of nonuse values, the contingent valuation method and the survey; in section 4 , survey results are presented and analyzed, followed by some concluding remarks.

2. Research areas

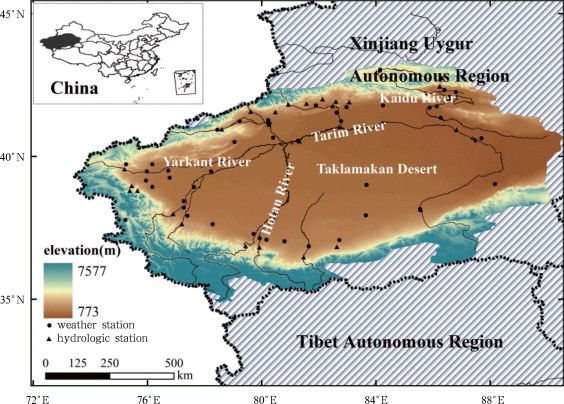

The Tarim River, located in an arid desert region in Northwest China, is the longest river in Central Asia. Figure 1 shows the location of the Tarim River and its basin. The natural environment as well as most economic activities and settlements in the Tarim River Basin directly depend on water from the Tarim River [ Thevs , 2011 ]. Since the 1950s agricultural activity, especially the extremely water intensive production of cotton, has expanded and the population in the oasis cities along the Tarim River has grown considerably. As a consequence, the Tarim River loses water as it flows downstream and the lowest parts of the river’s downstream reaches are completely desiccated due to the extensive exploitation of river water in the upper reaches. The dramatic loss of water resources in the lower reaches has led to a severe deterioration of the highly vulnerable riparian ecosystems, desertification and loss of biodiversity, negatively affecting the living conditions of local people and the development of the entire region. Due to the predicted impacts of climate change, i.e., increasing temperatures, changes in seasonal precipitation and glacier melting, the problem of water shortage will become more and more serious and the effects on the entire region will be disastrous [ Chen et al. , 2013 ]. Worst-case scenarios predict the complete desiccation of the Tarim River leading to a merging of the Taklamakan Desert into the southern part of the Gobi Desert.

|

|

|

Figure 1. The Tarim River Basin in Northwest China and locations of meteorological and hydrological stations source: China Meteorological Administration |

The environmental problems of the Tarim River Basin have been extensively studied by Chinese and foreign researchers and since the turn of the century the Chinese Government has heavily invested in projects aimed at improving the situation. Furthermore, two World Bank projects (1991–1997 & 1998–2005) led to improvements of the water distribution infrastructure and the establishment of mechanisms for sustainable water management in the region [ WB , 2007 ]. However, water shortage remains a problem and the environmental deterioration in the lower reaches of the Tarim River is progressing [ Tao et al. , 2008 ]. Taking into account the predicted impacts of climate change on the Tarim area, an integrated river basin management, in particular an improved water management and, in conjunction, a more sustainable land management, is urgently needed [ Chen et al. , 2013 ]. It is clear that the scientific development, the implementation and the maintenance of such a climate adaptation policy are very costly and that it will require further investments by the Chinese Government. An important question is whether these high costs can be justified from a social point of view. Environmental cost-benefit analysis can be used by decision makers in order to decide whether this climate adaptation policy should be implemented or not.

3. Data and method

3.1. The concept of nonuse values

Krutilla [1967] pointed out that people can gain utility from a natural resource without using it. With this observation he introduced the above mentioned concept of the nonuse values of public goods into the discussion on the appraisal of public projects. Following the total value approach, both use values and nonuse values need to be assessed for a comprehensive valuation of public goods or projects.

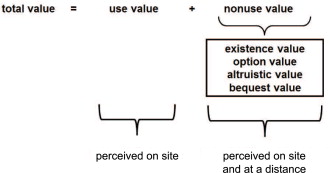

The nonuse value of a natural resource can be disaggregated into its existence value (preservation of the resource for its own sake, i.e., in absence of any intention to ever use it), its option value (arising from preserving the option of using the natural resource in the future), its altruistic value (accruing from the pleasure of knowing that others will enjoy the natural resource), and its bequest value (generated by the enjoyment of knowing that future generations can benefit from the natural resource). In contrast to the use values that can only be enjoyed by the direct users of an environmental resource, e.g., people living on site, nonuse values can also be experienced at a distance (Fig. 2 ). This latter feature of nonuse values has important consequences for environmental cost-benefit analysis.

|

|

|

Figure 2. The total value of an environmental resource |

Since social benefits depend both on the increase of wellbeing of individual households and on the number of households considered, a critical question is to decide on the relevant population when assessing social benefits [ Hanley et al. , 2003 ]. In many cases, the impacts of global climate change are most serious in scarcely populated regions. The high costs of public climate adaptation projects could not be justified only by the benefits accruing to people directly affected, because the aggregated benefits would be very low due to the small number of households affected. However, due to its nonuse values, not only people on site but also those living far away might obtain benefits from projects leading to improved environmental conditions. Future generations are often the main beneficiaries of climate policy, so that the bequest value is likely to be quite high. As explained above, considering only the benefits enjoyed by local people would lead to a dramatic underestimation of the social value of a public project and thus to misleading results of the environmental cost-benefit analysis.

In developing and emerging countries household budgets are often tight, traveling is luxury and for many households economic prosperity matters more than environmental protection. Thus, the question arises whether the above argument also holds for population considered in present study, i.e., whether people in China perceive so-called nonuse values at all.

3.2. The Contingent Valuation Method

In an environmental economic assessment costs and benefits, expressed in monetary terms, need to be compared to each other. Whereas the economic cost of projects in the environmental sector can be calculated based on market prices, the assessment of the benefits accruing to society as a whole is more challenging. Changes in social welfare due to a change in environmental quality are not reflected by market prices and have to be estimated using environmental valuation methods.

The Contingent Valuation Method (CVM) is widely accepted and the most popular technique for the evaluation of public projects in environmental sector, including climate adaptation policy [ Carson and Hanemann , 2005 ]. The CVM is an interview-based method where a representative sample of households affected by an environmental project is asked to state their willingness to pay (WTP) for the realization of that project. It is assumed that a household’s WTP reflects the utility it gets from the implied environmental improvement in monetary terms. The sum of the individual WTPs of all households affected equals the overall social value of the environmental improvement. In practice, the overall social value is calculated by multiplying the average WTP of a representative household sample by the number of all households affected. In contrast to indirect valuation methods, such as the travel cost method or the hedonic price method, CVM allows for a comprehensive measurement of both use values and nonuse values [ Ahlheim and Frör , 2003 ].

Because of its suitability for the estimation of the total economic value of public projects in environmental sector, the CVM is a powerful assessment instrument in the context of climate adaptation policy. In addition to measuring social benefits in monetary terms, factors determining a household’s WTP (household size, income, etc.) as well as environmental attitudes of the respondents are investigated in a CVM study. As highlighted by Deng et al. [2012] understanding the public view on climate adaptation and mitigation measures is essential in the overall context of climate policy.

3.3. Sample population, questionnaire design and sampling method

The water and land management project considered in this study is thought to increase the wellbeing of people living on site (e.g., in the Tarim River Basin) and also of people living far away due to its nonuse values. This paper focuses on the nonuse values experienced by households indirectly affected by the project and therefore only investigates the view of people living far away from the project area.

The city of Beijing was chosen as a study site because its residents may be viewed as a good example of a population indirectly affected by the water and land management project in the Tarim area. Because of the relatively small sample size (303), only adults currently living in one of the six urban districts of Beijing were sampled.

The questionnaire was jointly designed by Chinese and German researchers based on interviews with experts in the field of water and land management in Xinjiang autonomous region and on in-depth interviews with Beijing citizens. Prior to the main survey, different versions of the questionnaire were thoroughly pretested (100 pretest interviews in total). In addition, several citizen expert group (CEG) workshops were held. Citizen experts are normal people, i.e., no scientific experts, representing their fellow citizens. CEGs are very useful in adapting CVM surveys to the specific socio-cultural context of the survey population. Well-designed CEG workshops can help to minimize biases in CVM studies [ Ahlheim et al. , 2010 ]. The questionnaire was steadily adapted based on information and suggestions obtained from CEGs.

The final questionnaire was structured in five parts, containing 1) demographic questions, 2) warmup questions concerning prior knowledge of the Tarim River Basin, 3) a third part containing a detailed description of the environmental and social problems resulting from water shortage, the project and the payment scenario, and the WTP elicitation question, 4) several follow-up questions on environmental issues, and 5) questions on household data. In order to increase the response rate, respondents were offered a monetary compensation of 30 RMB (about 3.80=C) for their efforts.

Since conventional household interviews were not possible for reasons of safety, 18 students of Minzu University of China conducted intercept face-to-face interviews in the surroundings of six subway stations in July 2012. The subway stations Dongzhimen, Xizhimen, Liujiayao, Guomao, Renmin University, and Weigongcun were chosen in order to access different groups of the population in different districts of the city. Interviews were not conducted directly at the subway station, but at suitable places such as cafes, restaurants, public parks, etc. Quota for gender, age and education based on official data from the Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics [ BMBOS , 2012 ] were employed in order to ensure representativeness of the sample. Out of 305 questionnaires, only 2 had to be discarded, leading to 303 valid interviews.

The third column in Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the survey sample. For comparison, official statistical data is provided in the fifth column. Since the data of the sample is very similar to the official data, it can be concluded that the sample is representative.

| Variable | Sample (303) | 95% confidence interval | Beijing Statistical Yearbook 2011a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 53.0% | [47%, 59%] | 52.0% |

| Female | 47.0% | [41%, 53%] | 48.0% | |

| Age | 18–29 | 30.3% | [25%, 36%] | 29.7% |

| 30–39 | 21.4% | [17%, 26%] | 21.0% | |

| 40–60 | 34.2% | [30%, 41%] | 34.6% | |

| > 60 | 14.1% | [9%, 17%] | 14.6% | |

| Education | Without or elementary education | 10.9% | [7%, 14%] | 12.3% |

| Middle education | 54.9% | [49%, 60%] | 54.9% | |

| Higher education | 34.2% | [29%, 40%] | 32.8% | |

| Ethnicity | Han | 94.7% | [92%, 97%] | 95.9% |

| Minorities | 5.3% | [3%, 8%] | 4.1% | |

| Disposable annual household income (RMB) | 83,621 | [73714, 93528] | 81,404b | |

| District of residence | Dongcheng | 11.2% | [7%, 14%] | 7.8% |

| Xicheng | 9.9% | [7%, 13%] | 10.6% | |

| Chaoyang | 24.3%* | [20%, 30%] | 30.3% | |

| Fengtai | 19.4% | [15%, 24%] | 18.0% | |

| Shijingshan | 1.6%* | [0.2%, 3%] | 5.3% | |

| Haidian | 33.6% | [28%, 35%] | 28.0% |

a. BMBOS [2012]

b. Average annual disposable income per capita multiplied by the average family size

- . Sample characteristics that are statistically different from the official data

4. Results

4.1. The attitude of Beijing citizens towards environmental deterioration in the Tarim River Basin

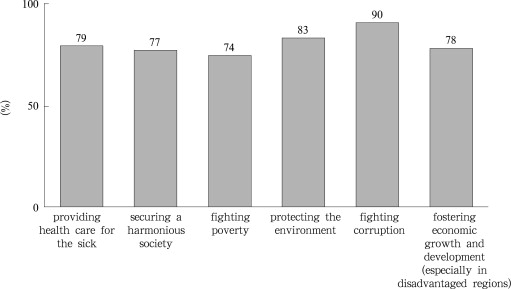

The attitude of Beijing citizens towards environmental problems in general and the environmental problems in the Tarim River Basin in particular was investigated in this survey. A general awareness of the need of protecting the environment can be seen as a precondition for the valuation of an environmental improvement occurring at distance and generating mainly nonuse value for the respondents in the sample. Interviewees were therefore asked to judge the importance of different tasks of the Chinese Government. As can be seen from Figure 3 environmental protection is viewed as the second most important task of government. It can be inferred, that people living in Beijing are very concerned about environmental problems in general. According to the majority of respondents, environmental protection should be given priority even over economic growth and over fighting poverty.

|

|

|

Figure 3. Public perceptions on the most important tasks of government (percentage of respondents who answered agree or strongly agree to the survey question Considering several fields of government activities, how important do you find the following tasks of government?) |

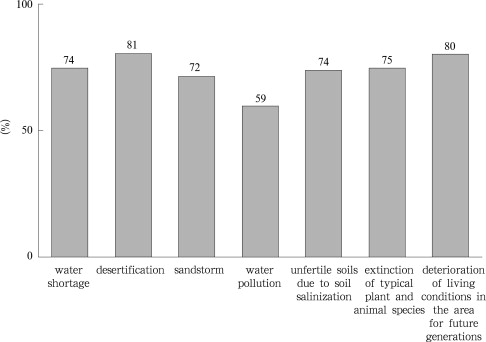

During the interviews, respondents were provided with a detailed description of the causes and consequences of environmental problems occurring in the Tarim River Basin. Afterwards they were asked how serious they found these problems. All seven problems listed were seen as very serious or extremely serious by the majority of respondents. Desertification of the landscape, the living conditions of future generations and extinction of typical plants and animal species are considered the three most urgent problems (Fig. 4 ). Note that 97% of people have never been to the Tarim River Basin and only 6% have relatives living in this area. In other words, the vast majority is not directly concerned by these issues. Therefore, high concern for the natural conditions as well as for future generations can be seen as an indicator that Beijing citizens experience nonuse values when thinking of environmental improvements in the Tarim area.

|

|

|

Figure 4. Public perceptions of environmental problems in the Tarim River Basin (percentage of respondents who answered agree or strongly agree to the survey question In your opinion, how serious do you find the following problems occurring in the Tarim River Basin?) |

4.2. Beijing citizens’ attitude towards a more sustainable water and land use management in the Tarim area

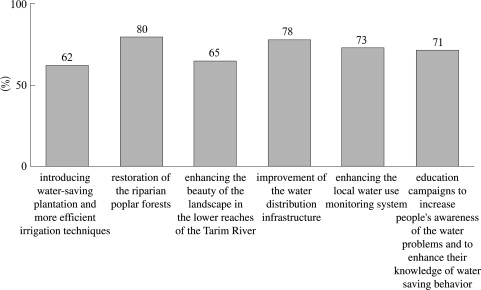

After the description of water shortage problem and its impacts the project scenario was read out by the interviewers. It was highlighted how a more sustainable water and land management project would lead to improved environmental conditions in the Tarim River Basin, especially under the predicted impacts of global climate change on the region. Some of the adaptation measures of this project were explained in more detail. Next, respondents were asked to state their opinion concerning the importance of these measures (Fig. 5 ).

|

|

|

Figure 5. Public opinion on selected policy measures of a more sustainable water and land management (percentage of respondents who answered important or very important to the survey question How important do you find the different measures to improve environmental conditions in the Tarim River Basin? ) |

Note that judging rather technical measures aimed at improving environmental conditions in an area located far away is not an easy task for survey respondents. The results reported in Figure 5 should not be interpreted as a recommendation for decision makers concerning the implementation of measures. However, some conclusions concerning the preferences of the population living far away from the Tarim River Basin can nevertheless be drawn. Beijing citizens stated a preference for the two short-term measures, namely afforestation and improvement of the water distribution infrastructure. Measures that are likely to take longer before being effective (education campaigns, enhancing the beauty of landscape) are less popular among the respondents. The relatively low importance ascribed to water-saving plantation and the improvement of irrigation techniques is at odds with the results of Deng et al. [2011] , a study in the Urumqi River Basin, where a very similar adaptation measure was ranked as most important by local residents. However, in accordance with the results of the Beijing survey, improvements of water distribution infrastructure were the second most-preferred adaptation measure in this same study.

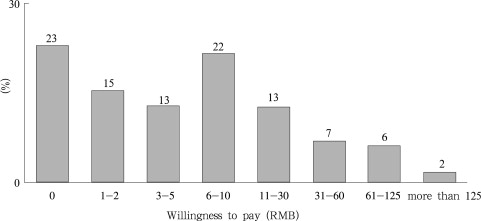

Finally, respondents were asked whether they personally would be willing to make a financial contribution in order to get sustainable water and land management program in the Tarim area implemented. They were told that the implementation of the program depended on the WTP of every household in China. Only if the total contribution of all Chinese households covered the costs, the project could be implemented. They were asked to select the maximum monthly amount that their household would be willing to contribute over the next 10 years from a payment card, i.e., from a list of ascending payment intervals. Figure 6 shows the distribution of WTP statements. Twenty-three percent of the respondents stated a zero WTP.

|

|

|

Figure 6. Distribution of WTP |

The majority of households with a non-zero WTP wants to pay 10 RMB per month or less. The average WTP, calculated based on the midpoints of the payment card intervals, is 16.50 RMB. Considering the purchasing power of Beijing households and the time span of this monthly payment (10 years), this amount can be interpreted as a considerable contribution to an environmental project generating exclusively nonuse values to a population living far away from the Tarim area.

4.3. Nonuse value of a more sustainable water and land use management in the Tarim area

Since a more sustainable water and land management in the Tarim area does not directly affect the citizens of Beijing, the mean WTP of 16.50 RMB can be interpreted as the monetary equivalent of the nonuse values experienced by the survey respondents.

Survey results indicate that the majority of respondents attribute a high importance to the improvement of the living conditions of future generations, the prevention of desertification and the protection of plants and animals (Fig. 4 ). Thus, WTP seems to reflect both existence and bequest values. In addition, the existence of altruistic preferences was tested using several follow-up questions subsequent to the elicitation question. For instance, 73% of the respondents that had stated a non-zero WTP agreed or strongly agreed with the statement I feel that we should do something to help the people in the Tarim area and I am glad that I now have the opportunity to do that and 69% said I want to contribute to the water management program because local people will live an easier and happier life if it will be realized .

At the end of the interview, respondents were asked whether they wanted to keep the 30 RMB they were offered as a compensation for participating in the interview, or if they wanted to donate the money to people living in the Tarim area. Fifty-nine percent of the respondents donated their gifts. High agreement to the follow-up questions on altruistic preferences as well as the considerable number of respondents willing to make a donation to the Tarim area indicate that Beijing residents’ stated WTP for the climate adaptation measures in the Tarim area encompasses altruistic motives.

During test interviews and CEG meetings it became clear that the Tarim area is not a popular tourist destination for Beijing citizens. Accordingly, the option value of improved environmental conditions in the Tarim area is likely to be quite low. The survey results confirm what was found during in-depth interviews and CEG meetings: only 4% of the respondents had ever been to the Tarim area; among these respondents only four stated touristic motives as reasons for their stay. Thus, the WTP of Beijing citizens mainly reflects the existence value and bequest value of improved environmental conditions in the Tarim area as well as altruistic preferences.

5. Discussion and conclusions

The existence of nonuse values of environmental improvements increases the social value of environmental projects beyond their mere use values. The fact that nonuse values might be experienced even by people living far away from the project area is especially important for the assessment of public projects in sparsely populated regions where use values are rather small. For a comprehensive assessment of the overall value of such projects also people living in regions far away from the project site must be surveyed in order to assess the nonuse values they might obtain from the environmental project in question.

In this study it was found that a more sustainable water and land management leading to an improvement of the environmental situation in the Tarim River Basin under the impression of future climate change is also welcomed by people living in Beijing. Their willingness to contribute financially to an improvement of the natural environment and living conditions in this remote (as viewed from Beijing) region can be explained by the existence of nonuse values. People in Beijing are very concerned about the impending environmental deterioration in Northwest China as a consequence of climate change, particularly with a view on future generations, the desertification of landscape, loss of biodiversity and the welfare of local people① .

One limitation of this study is the rather small sample size. Due to the low number of observations, no regression analysis was conducted and therefore no conclusions concerning the impact of indicators for nonuse values on WTP can be drawn. A larger study with over 2,000 interviews is in preparation in order to derive stronger and more comprehensive results.

Critics frequently address the hypothetical response bias in CVM studies leading to an overstatement of WTP [ Hausman , 2012 ]. The existence of a hypothetical bias can be checked by comparing stated WTP with actual behavior of respondents. In this study we offered respondents the chance to donate the money we had given them as a compensation for participating in our interviews. This donation would benefit people in the Tarim area directly. While the share of people willing to donate real money to the Tarim area was lower than the share of people willing to pay for climate adaptation measures in the hypothetical setting (59% and 77% respectively) the amount of the donation (30 RMB) was almost twice as high as the stated average monthly WTP (16.50 RMB). Thus, the donation experiment provides at least some evidence that the majority of respondents in Beijing is indeed willing to give up some money for the wellbeing of people living in the Tarim area. This fact can be seen as an indication that there exist altruistic feelings of Beijing residents towards people living in the Tarim area. This finding makes the existence of nonuse values of climate change adaptation measures in the Tarim River Basin plausible and lets our WTP results appear realistic.

Summing up, the WTP of Beijing citizens for an environmental improvement without any direct effect on their wellbeing indicates that people in emerging countries like China also seem to perceive nonuse values. Not accounting for them would lead to an underestimation of the social value accruing from environmental projects, especially in the context of climate policy. The results of the present study indicate that for a comprehensive assessment of climate adaptation projects in China also the preferences of people living in regions far away from the project site should be considered for the decision if such a project is worthwhile implementing from a social welfare point of view.

In practice, a full cost-benefit analysis of climate adaptation policy in remote areas requires that the monetary estimate for the social benefit encompasses the preferences of all Chinese people both directly and indirectly affected by that policy. Although outside of the scope of present study, we suggest to use a measure of aggregate WTP derived from a sample representative of the entire Chinese population for assessing whether the implementation of climate adaptation measures in the Tarim River Basin is worth its costs.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted in the context of the Sino-German joint research project SuMaRiO which is founded by the German Ministry of Education and Research, and as an international cooperation project, supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology (No. 2011DFG23440). This work is also supported by the National Science Foundation of China (No. 41171406). We also want to thank Prof. DAI Tang-Ping and his students from Minzu University of China for supporting the survey in Beijing.

References

- Ahlheim, 2002 M. Ahlheim; Zur ökonomischen bewertung von umweltveränderungen; B. Genser (Ed.), Finanzpolitik und Umwelt (2002), pp. 9–71 B. Ed., Berlin

- Ahlheim and Frör, 2003 M. Ahlheim, O. Frör; Valuing the nonmarket production of agriculture; Agrarwirtschaft, 52 (2003), pp. 356–369

- Ahlheim et al., 2010 M. Ahlheim, B. Ekasingh, O. Frör, et al.; Better than their reputation: Enhancing the validity of contingent valuation mail survey results through citizen expert groups; Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 53 (2010), pp. 163–182

- BMBOS (Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics), 2012 BMBOS (Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics); Beijing Statistical Yearbook 2011, China Statistics Press (2012), p. 580

- Carson and Hanemann, 2005 R.T. Carson, W.M. Hanemann; Contingent valuation; K.G. Maler (Ed.), et al. , Handbook of Environmental Economics. Volume 2. Valuing Environmental Changes, Elsevier (2005), pp. 821–936

- Chen et al., 2013 Y. Chen, C. Xu, Y. Chen, et al.; Progress, challenges and prospects of eco-hydrological studies in the Tarim River Basin of Xinjiang, China; Environmental Management, 51 (2013), pp. 138–153

- Deng et al., 2012 M.-Z. Deng, D.-H. Qin, H.-G. Zhang; Public perceptions of climate and cryosphere change in typical arid inland river areas of China: Facts, impacts and selections of adaptation measures; Quaternary International, 282 (2012), pp. 48–57

- Deng et al., 2011 M.-Z. Deng, H.-G. Zhang, W.-Y. Mao, et al.; Public perceptions of cryosphere change and the selection of adaptation measures in the Urumqi River Basin; Adv. Clim. Change Res., 2 (2011), pp. 149–158

- Dunlap et al., 2000 R.E. Dunlap, K.D. van Liere, A.G. Mertig, et al.; New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale; Journal of Social Issues, 56 (2000), pp. 425–442

- Ebi and Semenza, 2008 K.L. Ebi, J.C. Semenza; Community-based adaptation to the health impacts of climate change; American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35 (2008), pp. 501–507

- Hanley et al., 2003 N. Hanley, F. Schläpfer, J. Spurgeon; Aggregating the benefits of environmental improvements: Distance-decay functions for use and non-use values; Journal of Environmental Management, 68 (2003), pp. 297–304

- Hanley et al., 1993 N. Hanley, C.L. Spash, R. Cullen; Cost-Benefit Analysis and The Environment, Edward Elgar Publishing Limited (1993), p. 275

- Harris, 2006 P.G. Harris; Environmental perspectives and behavior in China: Synopsis and bibliography; Environment and Behavior, 38 (2006), pp. 5–21

- Hausman, 2012 J. Hausman; Contingent valuation: From dubious to hopeless; The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26 (2012), pp. 43–56

- Krutilla, 1967 J. Krutilla; Conservation reconsidered; American Economic Review, 56 (1967), pp. 777–786

- Lowe et al., 2006 T. Lowe, K. Brown, S. Dessai, et al.; Does tomorrow ever come? Disaster narrative and public perceptions of climate change; Public Understanding of Science, 15 (2006), pp. 435–457

- Luo et al., 2009 J. Luo, J. Pan, E. Li, et al.; Ethics orientation of college students towards the climate change; Impact of Science on Society (in Chinese), 3 (2009), pp. 5–9

- Mitchell and Carson, 1989 R.C. Mitchell, R.T. Carson; Using Surveys to Value Public Goods: The Contingent Valuation Method, Rff Press (1989), p. 463

- Rebetez, 1996 M. Rebetez; Public expectation as an element of human perception of climate change; Climatic Change, 32 (1996), pp. 495–509

- Semenza et al., 2008 J.C. Semenza, D.E. Hall, D.J. Wilson, et al.; Public perception of climate change: Voluntary mitigation and barriers to behavior change; American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35 (2008), pp. 479–487

- Tao et al., 2008 H. Tao, M. Gemmer, Y. Song, et al.; Ecohydrological responses on water diversion in the lower reaches of the Tarim River, China, Water Resources Research (2008), p. 44 http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2007WR006186

- Thevs, 2011 N. Thevs; Water scarcity and allocation in the Tarim Basin: Decision structures and adaptations on the local level; Journal of Current Chinese Affaires, 3 (2011), pp. 113–137

- WB, 2007 WB (World Bank), 2007[2013-02-01]: Restoring China’s Tarim River Basin. Accessed http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2007/05/29/restoring-chinas-tarim-river-basin .

Notes

①. It would be interesting to compare the preference for adaptation measures and the WTP of people living in Beijing to those of people living in the Tarim area, i.e., the population experiencing both use and nonuse values. Therefore, it is planned to conduct a similar survey with local people in the Tarim region

Document information

Published on 15/05/17

Submitted on 15/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?