Abstract

With architectural firms, owners are often managers whose characteristics may influence the firm structure. This study investigated the relationships between ownership characteristics, organizational structure, and performance of architectural firms. Utilizing a sample of architectural firms from Nigeria, a questionnaire survey of 92 architectural firms was carried out. Data were analyzed using multiple analysis of variance (MANOVA) and regression analyses. A generally low level of specialization of duties was observed even though professional service firms were defined as highly specialized firms. For most of the firms, level of formalization was moderate or high, while level of centralization was mostly low. Results revealed a direct significant relationship between legal ownership form and formalization dimension of structure. In addition, the centralization dimension of structure influenced firm performance. However, no direct relationship between ownership characteristics and performance was noted, although different fits of ownership characteristics and structural variables were observed. The results suggest that principals of architectural firms should match their characteristics with the firm structure to enhance performance in relation to profit.

Keywords

Architectural firm ; Professional service firm ; Ownership ; Organizational structure ; Performance

1. Introduction

What is the relationship between the ownership characteristics of architectural firms, structure, and firm performance? This research question guides this paper. In recent times, researchers have investigated different forms of ownership of professional service firms. Very relevant in this context is the study by Greenwood and Empson (2003) , who attempted to determine why partnership forms of ownership may be particularly effective for delivery of professional services. In spite of the fact that ownership has been noted as a critical organizational variable in determining professional service firm outcomes (Kang and Sorensen, 1999 ), Demsetz and Villalonga (2001) found no significant relation between legal ownership structure and firm performance. Thus, it will appear that ownership influences other organizational factors, which in turn influence firm performance. For architectural firms with owners cum managers who are often not specially trained in organizational management, form of ownership may influence the ways in which firms are organized. This is likely because the way the owners organize their firms will depend on their training and experiences. However, very few empirical studies have been conducted on the subject, especially in architectural firms, which have been noted to be peculiar (Blau, 1984 ). Although structure has generally been described in terms of specialization, centralization, and formalization (Zhou and De Wit, 2009 ), there has been little description of the structure of architectural firms in these terms. Even less is known about the ways the ownership characteristics of architectural firms are related to these structures and to the performance of firms.

Description of the structure of architectural firms as well as the relationship among ownership characteristics of architectural firms, their structures, and their performance are explored in this study. In particular, two questions are addressed. First, how do architects (as owners of firms who often also manage them) organize their firms? Second, what types of relationships exist between the ownership and structure of architectural firms and performance? By these, the study is expected to provide empirical evidence of the description of the structure of architectural firms in terms of their centralization, formalization, and specialization, which are dimensions by which organizational structure is often described. The importance of this study also lies in its potential to indicate how architectural firms fit their structure to their ownership characteristics to enhance profit.

2. Literature review

Different ownership forms used in professional service firms have been identified in literature. These include partnership (Wilhelm and Downing, 2001 ; Pinnington and Morris, 2002 ; Greenwood and Empson, 2003 ); public corporation (Schulze et al., 2003 ); and private corporations, namely, limited liability and unlimited liability companies (Greenwood et al., 2007 ). Greenwood and Empson (2003) describe professional partnership as a form of ownership that represents an agreement between two or more persons, with each partner being jointly and severally liable for the debts of the other. Professional partnership is not a legal entity. Greenwood and Empson (2003) further noted that although private corporations share many characteristics of the partnership in that senior professionals own private corporations, it is a legal entity. The limited liability company provides the limited liability of a corporation and flexibility of partnership. The basic difference between limited and unlimited liability companies, according to Chappell and Willis (2000) , is that when faced with debt, shareholders of an unlimited liability company contribute in the proportion of their shareholdings, while shareholders of limited liability company have no further liability as the company simply winds up. However, the ownership of the public company is in the hands of the shareholding public, as the name implies (Chappell and Willis, 2000 ), although professional registration bodies would insist that a professional should control the company. This ownership form is excluded from this study because owners of public corporations are not necessarily the managers. One ownership form that has received very little empirical study in the professional setting is sole proprietorship.

Greenwood et al. (2007) referred to the firms with other legal ownership forms apart from public corporations as internally managed professional firms. They found differences in performance within these internally managed professional service firms depending on whether they are partnerships or private corporations. There were two reasons given for expecting the partnership to perform better than private corporations. The first was that partnerships in professional service firms are reputed to be more client interest-driven and less profit-driven than private corporations (Greenwood and Empson, 2003 ). For this reason, Deephouse (2000) suggested that partnerships would attract more clients, charge more for services, and record higher performance. The second reason for expecting partnerships to outperform private corporations was tendered by Greenwood et al. (2007) , who suggested that the wider scope of liability of partnerships might lead to better management of those firms, leading to higher performance.

The fact that ownership forms differ suggests that the way the principals will organize their firms may differ based on the ownership structure. One pointer to this is that Chua et al. (2009) in their study of family firms found that the structure of family firms vary from that of non-family firms. The fact the owners of architectural firms are often not trained in organizational management, yet they manage their firms personally, may also suggest that the characteristics of owners may influence firm structure. Previous studies have found a correlation between managers' characteristics and firm performance. For example, Hitt et al. (2001) and Pennings et al. (1998) found that education and experience of managers influenced firm performance. Within the construction industry, Fraser (2000) and Kim and Arditi (2010) found that the educational level, involvement in continuing education, number of firms worked for, membership of professional bodies, and leadership style influenced the performance of construction firms. With architectural firms, however, these managers are often the owners and the relationship may differ. It may therefore be worthwhile to investigate the relationship between ownership characteristics and structure of firms and the attendant individual and combined effects on the performance of architectural firms.

The foregoing discussed studies on the influence of ownership characteristics and performance as well as ownership characteristics and structure. In addition to these relationships, however, a number of factors have been hypothesized to moderate the relationship between ownership and performance. One of such factors is number of hierarchical levels (Durand and Vargas, 2003 ). Greenwood and Empson (2003) suggested that formal hierarchies and bureaucratic controls are unlikely to succeed in a professional service firm because the professional staff is expected to have autonomy and freedom to perform well. They suggested that the partnership and private corporation professional service firms would perform well because they use collegiate rather than hierarchical controls. This suggests that flatter hierarchies may outperform multi-layered ones. Hierarchy is an aspect of structure that represents the level of centralization of decision-making in architectural firms. This is an aspect of structure defined by Willem and Buelens (2009) as the extent to which decision-making power is concentrated in top management level of the organization. Pertusa-Ortega et al. (2010) suggested that decentralization involving the distribution of authority fosters the incorporation of a greater number of individuals in the management of the organization. They suggested that decentralization enables members of organizations to act autonomously, thereby fostering better business opportunities. On the contrary, centralization reduces generation of creative solutions as experimentation and circulation of ideas are reduced. Going by this observation, one would expect that high centralization would lead to poor performance in creative firms such as architectural firms.

Structure, according to Zhou and De Wit (2009) , is the way in which an organization organizes and coordinates its works. In addition to centralization, other dimensions of structure are formalization and specialization. Specialization has been referred to as complexity by Pertusa-Ortega et al. (2010) , and departmentalization by Zhou and De Wit (2009) . It is the extent to which organizational tasks are divided into subtasks and people are allocated to execute only one of these subtasks. High-level specialization exists when each person performs only a limited number of tasks, while low-level specialization implies that people perform a range of different and frequently changing tasks. Formalization, on the other hand, is the extent to which the rights and duties of the members of the organization are determined and the extent to which these are written down in rules, procedures, and instructions. Architectural firms are professional service firms where professionals have autonomy on aspects of the work under their control, according to Mills et al. (1983) . This suggests that decision-making in such organizations is decentralized. However, a high degree of specialization of duties and formalization of office procedures may exist. These have yet to be proven empirically.

Based on the literature review, the present study investigates a four-way relationship. Direct relationships are expected between ownership characteristics and structure, ownership characteristics and performance, as well as structure and performance. The fourth relationship expected pertains to interaction effects of ownership and structure on performance.

3. Research methods

Architectural firms included in the study were selected from the 342 firms listed in the Register of architectural firms licensed to practice in Nigeria (ARCON, 2006 ). A total of 157 were selected from the list of 342 firms. Sampled firms were randomly selected from six cities where 77.7% of firms were located. These cities were Lagos, Abuja, Kaduna, Enugu, Port Harcourt, and Ibadan. Firms selected were those that carried out core architectural services and were headed by registered architects. Principals of the firms were asked to fill out the questionnaires. Questionnaires were administered between February and May 2008, with the aid of 15 field assistants. Only 92 questionnaires were returned, representing a response rate of 58.6%.

One of the limitations of the study was the difficulty in locating most of the firms at the addresses indicated on the register (ARCON, 2006 ). Moreover, many principals refused to fill the questionnaires, citing time constraints.

Firms in the study were asked to indicate the tasks performed exclusively by at least one staff member. Existence of departments within the firms was investigated as well. These two questions will suggest the level of specialization within the firms. For the level of formalization of office procedures, firms were asked to rate how formal seven office procedures were on a Likert scale of 1–3. Informal office procedures were rated as 1, fairly formal office procedures as 2, and very formal office procedures as 3. Rating of formalization for all activities was added for each firm and re-coded. Total scores ranged from 7 to 21.

Totals ranging between 7 and 11 were re-coded as informal, 12 to 16 as fairly formal, and between 17 and 21 as very formal. Firms were asked to indicate persons who formulated decisions on certain issues within the firm. This was ranked in order of seniority from 1 to 6 for any staff, any administrative staff, any architect, administrative manager, senior architect, and principal partner, respectively. Level of centralization of decision-making within the firms was obtained from this. Scorings between were re-coded: 8 and 16 as low degree of centralization; 17–32 as moderate degree of centralization; and between 33 and 48 as high degree of centralization. These are represented in Table 1 .

| Construct | Variables |

|---|---|

| Ownership | Legal structure of firm, age, gender, educational qualification, and experience of the founding principal |

| Specialization | Number of tasks exclusively performed by at least one staff |

| Existence of departments | |

| Formalization (1—informal, 3—very formal) | Communication with staff within the office |

| Communication with other professionals | |

| Communication with clients | |

| Financial matters and budgeting | |

| Management decisions | |

| Staff working conditions and job descriptions | |

| Meetings in the office | |

| Centralization of decision-making (1—any staff, 8—principal of firm) | How to acquire new jobs and clients |

| Collaborations with other firms | |

| Management of non-design staff | |

| Fees to be charged for projects | |

| Hiring/promotion of architects | |

| Design ideas to be used in projects | |

| Managing projects | |

| Salaries of staff | |

| Firm performance | Perception of the profit of the firm in the last 2 years |

Firm performance was measured in terms of the perception of the firms' profit in the last 2 years. Perception of the principals was adopted because of paucity of data on actual profits of the firms; the principals were not willing to divulge such information. Perception of the principals was adopted because Wall et al. (2004) found that subjective measures of performance obtained from top management were as valid as objective measures. Ownership characteristics of the firms were measured using the legal structures of firms, gender, age, qualification, experience, and leadership styles of the principals.

Prevalent levels of structural dimensions are presented in frequencies. This gave an idea of how architectural firms generally organized their firms in terms of centralization, specialization, and formalization. Multiple analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed to investigate the direct influence of ownership characteristics on the structural variables. This is because the structure entered as the dependent variable had more than one dimension. To investigate the dimensions of structure that influenced firm performance, regression analysis was carried out. To investigate the direct influence of ownership characteristics of performance and the interaction effect of ownership characteristics and structure on performance, hierarchical regression analysis was performed. This was to ensure that direct effects of ownership characteristics and structure are first removed before the interaction effect is investigated.

4. Results

Sole principals (Table 2 ) owned most of the firms that responded to the questionnaire. Most of the principals were men and the age range of the responding principals were mostly 41 years and above. Most of the principals had the Bachelor of Architecture or Master of Science in Architecture, which in Nigeria are equivalent professional degrees required to practice architecture. The principals were quite experienced, with years of experience mostly 16 years and above. Most of the principals were visionary and innovative leaders, or productivity-oriented achievers. Level of specialization of duties was mostly low, with just about half of the firms having departments. Level formalization of office activities was mostly moderate to high, while only about a quarter of the firms exhibited high centralization of decisions.

| Firm profiles | Percentage of occurrence |

|---|---|

| LEGAL STRUCTURE OF OWNERSHIP | |

| Sole principal | 52.3 |

| Partnership | 21.6 |

| Unlimited liability company | 8.0 |

| Limited liability company | 18.1 |

| GENDER OF PRINCIPAL | |

| Male | 89.8 |

| Female | 10.2 |

| AGE OF PRINCIPAL | |

| Below 30 years | 1.2 |

| 31–40 years | 22.4 |

| 41–50 years | 43.5 |

| 51–65 years | 27.1 |

| Above 65 years | 5.9 |

| HIGHEST QUALIFICATION OF PRINCIPAL | |

| HND | 3.5 |

| BSc | 3.5 |

| MSc | 43.5 |

| BArch | 42.4 |

| Others | 7.1 |

| YEARS OF EXPERIENCE OF ARCHITECT | |

| 1–5 years | 1.5 |

| 6–10 years | 12.1 |

| 11–15 years | 15.2 |

| 16–20 years | 18.2 |

| 21–25 years | 21.2 |

| 26 years and above | 31.8 |

| MANAGEMENT STYLE OF PRINCIPAL | |

| A mentor in the firm | 9.3 |

| A visionary and innovative leader | 38.4 |

| An efficient manager | 11.6 |

| A productivity-oriented achiever | 40.7 |

| LEVEL OF SPECIALIZATION | |

| No specialization of task | 9.5 |

| Very few tasks are specialized | 41.7 |

| Moderate level of specialization | 21.4 |

| High specialization of tasks | 19.0 |

| Very high specialization of tasks | 8.3 |

| EXISTENCE OF DEPARTMENTS | |

| Departments exist | 45.9 |

| Departments do not exist | 52.9 |

| Not sure | 1.2 |

| LEVEL OF FORMALIZATION OF OFFICE PROCEDURES | |

| Low formalization | 16.3 |

| Moderate formalization | 45.0 |

| High formalization | 38.8 |

| LEVEL OF CENTRALIZATION OF DECISIONS | |

| Decentralized | 40.3 |

| Moderate centralization | 31.9 |

| High centralization | 27.8 |

| PERCEPTION OF THE FIRM'S PROFIT | |

| Not so good | 28.1 |

| Very good | 71.9 |

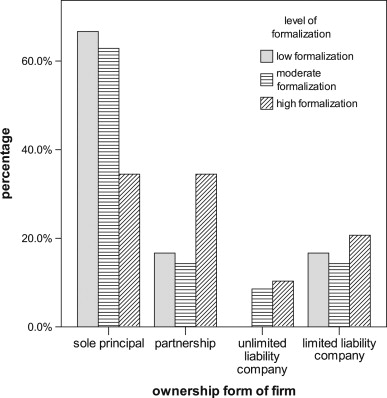

A one-way between groups multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed to investigate how the ownership characteristics of the architectural firms influenced their structure. The independent variables were the ownership characteristics of the firms, while the dependent variables were the dimensions of structure investigated in the study. From the results, influence of the ownership characteristics of the firms on their structure was significant. (F(3,63) =1.35, p <0.05, Wilks' Lambda=0.83, partial eta squared=0.62). The test of between-subjects effects shows that only the formalization of office procedures was significantly influenced by the legal ownership forms of the firms (F(3,63) =3.12, p <0.05, partial eta squared=0.13). Mean scores of the firms on formalization were used to plot a graph based on their legal ownership forms. Fig. 1 demonstrates that most of the architectural firms with the sole principal ownership form operated the low level of formalization, while most of the partnership and unlimited liability firms operated moderate to high levels of formalization.

|

|

|

Fig. 1. Legal structures of the firms by the level of formalization of office procedures. Source : Authors fieldwork (2008). |

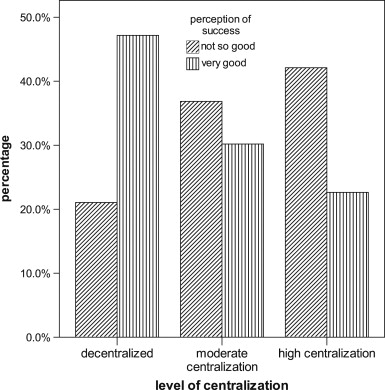

Regression analysis of the direct relationship between organizational structure and performance also indicated a significant relationship (R2 =0.108, p <0.05). In particular, centralization of decisions dimension of structure significantly influenced firm performance. Mean performance scores of the firms by the level of centralization of decisions in Fig. 2 show that most of the architectural firms with decentralized decision-making performed best, while those with highly centralized structure were the least performers. However, no direct relationship between the ownership characteristics of the firms and their performance in profit was observed.

|

|

|

Fig. 2. Level of centralization of decisions and perception of firm success. Source : Authors fieldwork (2008). |

Investigating the interaction effects of the structure and ownership characteristics of the firms on their performance was important in this study as well. Hierarchical regression analysis was therefore used to investigate the relationship among ownership, structure, and performance of the firms. Structural variables were entered first to control for any effect that structure may have on performance. A significant effect may indicate the presence of a direct relationship. Ownership characteristics were entered second to investigate the direct relationship between ownership characteristics and firm performance. With these, the main effects were eliminated before the interaction effect of ownership and structure on firm performance was investigated.

Interaction between ownership characteristics and structure were entered in the third step. Significant effect here would indicate that the relationship between ownership and performance is moderated by the firm structure. Results of the hierarchical regression analysis for performance are displayed in Table 3 . Results show that firm structure was significantly related to performance (R2 change=0.108, p <0.05), accounting for 10.8% of the variance in firm performance. Centralization of decision-making (Wald=6.875, p =0.009) was the variable that significantly influenced performance. With the structure controlled, however, the ownership characteristics did not significantly influence the performance of the firms. This suggests no direct influence of the ownership characteristics on the performance of the firms.

| Variables | Performance Wald | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | ||

| Structure | Specialization of duties | 2.094 | 1.289 | 3.716c |

| Formalization of office procedures | 2.704 | 3.208c | 2.835 | |

| Centralization of decision-making | 6.875a | 5.046b | 1.807 | |

| Ownership | Experience of principal | 0.153 | 2.735c | |

| Gender of principal | 0.128 | 2.450 | ||

| Age of principal | 0.028 | 3.058c | ||

| Highest qualification of principal | 2.255 | 1.455 | ||

| Management style of principal | 1.584 | 3.678c | ||

| Legal structure of firm | 0.072 | 4.629b | ||

| Structure/ownership interaction | Experience of principal×specialization | 4.156b | ||

| Gender of principal×specialization | 2.420 | |||

| Age of principal×specialization | 3.024 | |||

| Qualification of principal×specialization | 2.854 | |||

| Management style of principal×specialization | 2.583 | |||

| Legal structure of firm×specialization | 0.373 | |||

| Experience of principal×formalization | 2.051 | |||

| Gender of principal×formalization | 3.197 | |||

| Age of principal×formalization | 2.840 | |||

| Highest qualification of principal×formalization | 2.999 | |||

| Management style of principal×formalization | 0.007 | |||

| Legal structure of firm×formalization | 4.210b | |||

| Experience of principal×centralization | 0.846 | |||

| Gender of principal×centralization | 1.738 | |||

| Age of principal×centralization | 3.220c | |||

| Highest qualification of principal×centralization | 0.142 | |||

| Management style of principal×centralization | 3.615c | |||

| Legal structure of firm×centralization | 2.173 | |||

| R2 change | 0.044 | 0.348a | ||

| R2 | 0.108a | 0.152 | 0.500a | |

a. p <0.01, two-tailed test.

b. p <0.05, two-tailed test.

c. p <0.10, two-tailed test.

Source : Authors fieldwork (2008).

Ownership characteristics/structure interaction, on the other hand, accounted for significant incremental variance (R2 change=0.348, p <0.001), resulting in a further 34.8% difference in performance. This result suggests that although ownership characteristics may not have directly influenced the performance of the firms, these characteristics interact with the structure of the firms to influence performance. Ownership characteristics that interacted with the specialization dimension of structure was the experience of the principal (Wald=4.156, p =0.041), while the formalization of office procedures interacted with the legal structure of the firms (Wald=4.21, p =0.040) to influence performance. Ownership characteristics that interacted with the centralization dimension of structure to influence performance are age (Wald=3.220, p =0.092) and management styles of the principal (Wald=3.615, p =0.082).

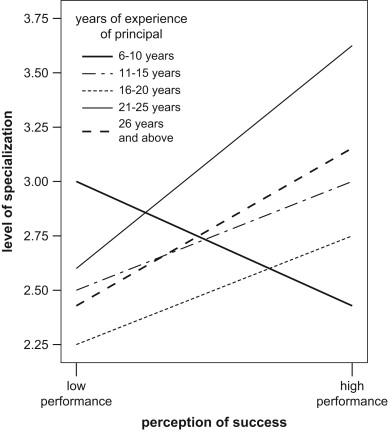

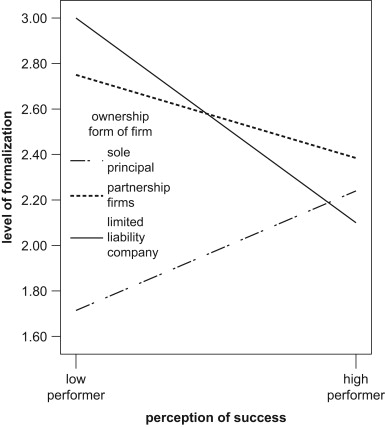

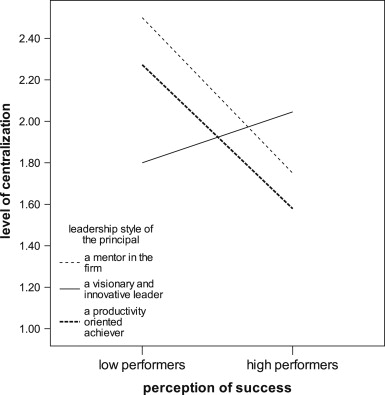

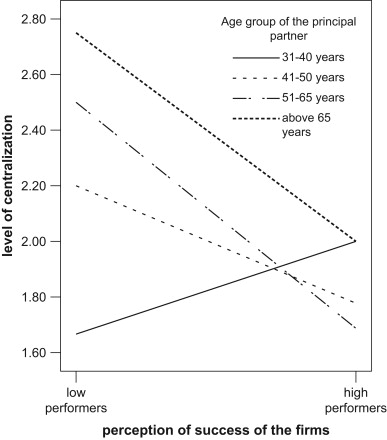

A closer look at the data (Fig. 3 ) reveals that firms that had principals with very few years of experience performed well with low level of specialization, while principals with experience greater than 10 years performed better with higher levels of specialization. Data likewise reveal that firms owned by sole principals performed well with high levels of formalization, while firms with the partnership or limited liability forms of ownership performed well with lower levels of formalization (Fig. 4 ). In addition, having a principal who is a visionary and innovative leader and operating high level of centralization resulted in good performance (Fig. 5 ); firms with principals whose leadership style was mentorship or productivity orientation performed well when they operated low level of centralization of decisions. The results (Fig. 6 ) further show that firms owned by young principals aged between 31 and 40 years performed better when they operated high levels of centralization of decisions. With older principals, however, firms performed better when they operated lower levels of centralization of decisions.

|

|

|

Fig. 3. Level of specialization of duties, experience of principals, and perception of firm success. Source : Authors fieldwork (2008). |

|

|

|

Fig. 4. Level of formalization of office procedures, legal structure of firms, and perception of firm. Source : Authors fieldwork (2008). |

|

|

|

Fig. 5. Level of centralization of decisions, leadership style of principals, and perception of firm success. Source : Authors fieldwork (2008). |

|

|

|

Fig. 6. Level of centralization of decisions, age of principals, and perception of firm success. Source : Authors fieldwork (2008). |

Levels of centralization of decision interacted with the management style and age of the principal to influence performance. Fig. 6 shows that firms with mentors or productivity-oriented achievers as principals performed better when they operated lower levels of centralization of decision. On the contrary, firms with visionary and innovative leaders as principals performed better when they operated higher levels of centralization of decisions. Firms owned by young principals between 31 and 40 years likewise performed better when they operated high levels of centralization of decisions. With older principals, however, firms performed better when they operated lower levels of centralization of decisions.

5. Discussion

Although sole principal-owned professional service firms have been accorded little attention in previous studies, this legal ownership form is most predominant in this study. This may be an evidence of the quest for job creation engendered by the prevalent high unemployment rate currently recorded in Nigeria. It also possibly suggests that architecture as a profession is easily sustained as individual practice. The profile likewise suggests a predominant male ownership. This is possibly because entrepreneurial demands of creation and management of architectural firms may be too tedious for women. About three-quarters of the firms were owned by principals aged above 40 years, suggesting that most of the principals may have gained experience elsewhere before starting their own firms. This is possibly also indicated by the findings that almost 90% of the principals held above 10 years of experience.

Although Mills et al. (1983) suggested that professional service firms would exhibit a high level of specialization, most architectural firms in the study exhibited low to moderate levels of specialization. This may suggest that although professional services are specialized services requiring professionals who specialize in their tasks, professionals performed more than one task within the architectural firms in the study. In addition, the low to moderate levels of specialization was observed in the data in spite of the fact that almost half of the firms indicated having departments. It is possible that even within the departments, the staff continues to multi-task. It may be insightful to investigate the types of departments that exist in architectural firms and the manner by which they operate. In line with the suggestion of Mills et al., however, the level of centralization in most of the firms was generally not so high. This is because most of the firms either were decentralized or exhibited a moderate level of centralization. This possibly suggests that professionals in the firms were given free hand to operate as well as to participate in the administration of the firms. Most of the firms likewise exhibited moderate to high levels of formalization. This suggests that although the professionals had a free hand to operate in most of the firms, they had written guidelines.

Interaction effects between ownership and structure generated interesting results. First, ownership characteristics did not significantly influence the centralization and specialization aspects of structure. This suggests that other variables of the firm, apart from ownership characteristics, may influence these dimensions of structure. However, level of formalization of office activities was influenced by the legal form of ownership. The reason why most of the sole principal firms exhibited the lowest level of formalization may be that they are not incorporated and therefore may not need to report their activities to any regulatory body. In addition, there is no second party to question whatever the sole principal does as such a person holds sway and may change rules at will. However, this is not the case with firms that had other forms of ownership. While partnerships report to partners, limited and unlimited liability firms are required by the Corporate Affairs Commission to keep records and submit them on occasion.

As earlier noted, Pertusa-Ortega et al. (2010) suggested that decentralization enables members of organizations to act autonomously, thereby fostering better business opportunities. This appears to be the case as decentralized firms performed best, suggesting that the inputs of professionals in architectural firms are highly important in running the firms to achieve best performance. Moreover, it possibly suggests that when architectural firms allow their employees to participate in management, they profit more. It is not immediately clear why the levels of specialization and formalization do not directly influence firm performance. However, it is possible that these dimensions of structure work through other factors in influencing the performance of architectural firms.

In line with the findings of Demsetz and Villalonga (2001) , the legal form of ownership of the firms as well as other ownership characteristics of architectural firms did not directly influence firm performance in terms of profit. This appears contrary to the findings of Fraser (2000) and Kim and Arditi (2010) on managers of construction firms. However, it suggests that influence of managers who are owners on firm performance may differ from the influence of managers who are not owners.

Based on the results, one can infer that the influence of ownership characteristics on performance is more in terms of interaction with other variables than direct influence. This is because the interaction of ownership characteristics and structure accounted for 34.8% of variance in performance in profits. Level of specialization, for example, which had no significant direct influence on firm performance, interacted with the years of experience to influence the firms. Poor performance recorded by firms when low experience of principals is combined with high level of specialization of firms may be explained. One reason why this may be so is that these principals are possibly merely starting off and, as such, the cost incurred by having one person exclusively in charge of any duty may not be balanced by the benefits to be derived from such specialization. With principals having more than 10 years experience, however, the firms performed better when they operated higher levels of specialization. An explanation for this may be that the experiences of these principals and possibly a highly specialized workforce place them at an advantage to attract specialized projects, which may often attract higher profits. Firms with experienced principals but lower specializations of tasks may not be able to attract such jobs or may have to sublet part of such jobs if they attract them, reducing the profits that may accrue to them.

Another way that the interaction of ownership characteristics and structure influenced performance was in terms of the way certain legal structures suited particular levels of formalization and resulted in better performance of the architectural firms. Although Greenwood and Empson (2003) explained that professional partnerships are expected to perform better because they are more likely to attract more clients and charge more fees because they are more client-oriented than private corporations, the findings of this study show that partnerships that adopt a high level of formalization perform better than those that adopt a low level of formalization. The same applies to limited liability companies as well. However, the opposite applies to sole principal firms. These results suggest that the level of formalization often associated with particular legal structures may need to be moderated for better performance. This is because when one person owns a firm, there is a tendency that there will be no agreement, rules, or regulations. The fact that the sole principal owned firms in the study performed better with higher levels of formalization of office procedures may therefore be explained by the fact that a higher level formalization than would be expected of such firms may help to coordinate activities, and thus reduce waste and inefficient procedures, leading to savings and increased profits. However, such firms may lose profit through lower formalization levels as only one principal may not adequately achieve efficiency, with tasks performed unsystematically. With partnerships and limited liability companies in the study, which are often expected to have written agreements, codes of practice, and procedures, better performance is recorded when those rules and procedures are played.

Another interaction effect on performance was recorded with level of centralization and leadership styles as well as the age of the firms. Although it had been found earlier that firms with decentralized structure performed best while firms with highly centralized structure performed worst, it appears this may also be situational. Why firms with principals that were visionary and innovative leaders performed better with high levels of centralization is unclear, since innovation of architectural firms is often linked to the professional workforce (Brown et al., 2010 ). Therefore, it will be expected that the staff is allowed to participate in decision-making to achieve higher innovation. The results, however, suggest that this innovation is not independent but coordinated. This is possibly because having a leader who is visionary and innovative may suggest that the firm pursues new ideas, which may not lend itself to discussion. This follows from the fact that following new ideas to gain profit may necessitate being the first in the market and thus taking immediate actions, which only the principals can effect. Higher levels of centralization may lead to faster actions and thus profit benefits of being the pacesetter.

Firms with principals described as either mentors or productivity-oriented achievers may have performed better with lower levels of centralization for certain reasons. It appears that firms with mentors as leaders may be better off when staff members are allowed to participate in decision-making. This may be because a mentor may often invest time and resources in helping the staff learn the business to be able to hold sway even when the owner is not around. One may expect that this kind of system will run better and be more productive with input of many who also represent the firm in words and actions. With higher levels of centralization of decisions, however, mentor-led firms in the study did not perform well. This is possibly because the gains of staff training may not have been harnessed to offset the cost in time and resources.

The result for firms owned by productivity-oriented achievers is similar. The result also suggests that firms owned by productivity-oriented achievers may also perform better when they allowed others, who are possibly also professionals in the field, to bring their ideas to the table by participating in running the firms. Another finding from the study is that firms with principals aged between 31 and 40 years performed better with higher levels of centralization. One explanation for this may be that firms with principals aged between 31 and 40 may not have grown to be experienced professionals whom they can trust to make the right decisions in their payrolls. Leaving decision-making to unqualified persons may lead to losses. Decentralization, however, works best for firms with principals older than 40, who may have grown to have more qualified professionals on their payroll and are confident enough to leave the running of the firms in the hands of others.

6. Conclusions

This study described the structure of architectural firms in Nigeria in terms of centralization, specialization, and formalization. An important finding is that a generally low level of specialization was observed. Thus, it appears that although architectural firms are engaged in trading specialized knowledge, professionals may multi-task within the firms themselves. Specialization often referred to in literature may be more in terms of overall tasks rather than the internal operations of firms. However, this needs to be investigated in the context of other professional service firms.

Relationships among ownership characteristics, organizational structure, and performance of architectural firms were investigated as well. Three of the relationships in the conceptual framework were found to be significant (Fig. 3 ). The relationship between ownership characteristic and performance was found to be insignificant, confirming the findings of Demsetz and Villalonga (2001) in the context of architectural firms. The findings also confirmed the findings of previous authors that the level of centralization influences firm performance. In particular, decentralization was observed in most high-performing firms. Although previous studies found significant relationships between managers' characteristics and performance, the findings of this study also suggest that no significant relationship exists between characteristics of principals who are both owners and managers and the performance of architectural firms. However, this is non-conclusive and requires further investigation.

Findings of this study have implications for practice. Findings suggest that certain fits of structure and ownership characteristics lead to better performance. One such fit is that high level of specialization leads to higher profit, except in firms headed by principals with very few years of experience. This suggests a need for architectural firms in Nigeria to reduce the levels of multi-tasking to record better performance in profit, except where the principals are not sufficiently experienced to manage the process. The fact that most architectural firms in the study exhibited low levels of centralization of decisions and most firms that performed well in terms of profit possibly recorded these low levels of centralization also has implications for the practice of the profession. This is especially true in light of the fact that all profitable firms in the study, except those with principals aged between 31 and 40 years or whose leadership style is visionary and innovative, recorded low centralization of decision-making. This suggests a need for architectural firms to allow inputs of other professionals in the firms in their decision-making process, except when it hampers the vision of the owner or the stage of life of the owner implies reduced capability to harness the input of others. In addition, it appears that architectural firms may need to moderate their required levels of formalization of office procedures as required by the laws setting them up to achieve greater success. This is because, where high level of formalization is ordinarily required, lower levels of formalization make for better success and vice versa. This can possibly explain why a generally moderate level of formalization of office procedures was observed among the architectural firms in the study.

There are a few limitations to this study. First, the study was performed in Nigeria. There may be a need to conduct similar studies in other countries so that the results can becompared to establish the limits of generalization. Another limitation to this study is the unavailability of data on the profit of the firms, urging the researchers to rely on the perception of the principals, which Walls et al. (2004) noted as a valid measurement of profit as well. Future studies may consider more objective measures of profit.

Appendix.

Questionnaire

Dear Sir/Madam,

Kindly give candid answers to the questions below. The questionnaire is designed to collect information on the organizational structure of architectural firms in Nigeria. I would be grateful if the principal or a senior partner completes the questionnaire. Please be assured that the information, which you will provide, will be treated in strict confidence and the results will be published only in an aggregated form. Your firm will remain anonymous.

Thank you.

General instruction

Please answer the following questions by ticking the relevant answers. Some questions may require you to circle one answer only, whereas others may request you to circle more than one number. The numbers beside the answers are for official use only.

Section A: (Organizational profile)

Section A1

- How would you describe the form of ownership of this firm?

Sole principal [1] Partnership [2] Unlimited liability company[3]

Limited liability company [4] Public company [5] Not Sure [6]

- What is the sex of the principal partner? Male [1]Female [2]

- Please tick the age group of the principal partner.

Below 30 [1] 31–40 [2] 41–50 [3] 51–65 [4] Above 65 [5]

- What is the highest qualification of the principal partner in architecture?

HND [1] BSc [2] MSC[3] BArch [4] Others [5] (specify……… …….…)

- How would you describe the principal?

A mentor in the firm [1] A visionary and innovative leader [2]

An efficient manager [3] A productivity oriented achiever [4]

Others [5] (Please specify………………………………………….)

- What is your perception of the success of your firms profit in the last 2 years?

Very good [1] Good [2] Fair [3] Not so good [4] Very Poor [5]

- Does the firm have departments/work units (accounting, personnel, transportation, etc)?

Yes [1]No [2] Not sure [3]

- Which of the following activities are dealt with exclusively by at least one full time personnel? (Please tick as many as apply)

| a. Public/clients relations | d. Sourcing for job | g. Transport | j. Modeling |

| b. Personnel | e. Maintenance | h. Training | k. Site meetings |

| c. Working drawing | f. Accounts | i. Designe | l. Welfar |

- How formal (written or documented) are the following office tasks?

| Task | Informal [1] | Fairly formal [2] | Very formal [3] |

| a. Communication with staff within the office | |||

| b. Communication with other professionals outside the office | |||

| c. Communication with clients | |||

| d. Financial matters and budgeting | |||

| e. Management decisions | |||

| f. Staff working conditions and job descriptions | |||

| g. Meetings in the office |

- Who usually takes decisions about the following?

| Issues requiring decisions | Principal partner[1] | Senior architects[2] | Any architect[3] | Admin. manager/accountant[4] | Any admin staff[5] | Any staff[6] |

| a. How to get new jobs and clients | ||||||

| b. Collaborations with other firms | ||||||

| c. Managing the non-design staff | ||||||

| d. Fees to be charged for projects | ||||||

| e. Hiring/promotion of architects | ||||||

| f. Design ideas to use in projects | ||||||

| g. Managing projects | ||||||

| h. Salaries of staff |

References

- Architects Registration Council of Nigeria (ARCON), 2006 Architects Registration Council of Nigeria (ARCON), 2006. Register of Architectural Firms Entitled to Practice in the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

- Blau, 1984 J. Blau; ‘Architecture and Daedalean Risk’, Architects and Firms: A Sociological Perspective on Architectural Practice; MIT Press (1984) pp. 133–145

- Brown et al., 2010 A.D. Brown, M. Kornberger, S.R. Clegg, C. Carter; Invisible walls and silent hierarchies: a case study of power relations in an architecture firm; Human Relations, 63 (2010), pp. 525–550

- Chappell and Willis, 2000 D. Chappell, C.J. Willis; The Architect in Practice; (8th ed.)Blackwell Science Ltd., UK (2000)

- Chua et al., 2009 J.H. Chua, J.J. Chrisman, E.B. Bergiel; An agency theoretic analysis of professionalized family firm; Entrepreneurship, Theory and Practice, 1042–2587 (2009), pp. 355–372

- Deephouse, 2000 D.L. Deephouse; Media reputation as a strategic resource: An integration of mass communications and resource based theories; Journal of Management, 26 (6) (2000), pp. 1091–1112

- Demsetz and Villalonga, 2001 H. Demsetz, B. Villalonga; Ownership structure and corporate performance; Journal of Corporate Finance, 7 (2001), pp. 209–233

- Durand and Vargas, 2003 R. Durand, V. Vargas; Ownership, organization, and private firms' efficient use of resources; Strategic Management Journal, 24 (7) (2003), pp. 667–675

- Fraser, 2000 C. Fraser; The influence of personal characteristics on effectiveness of construction site managers; Construction Management and Economics, 18 (1) (2000), pp. 29–36

- Greenwood et al., 2007 R. Greenwood, D.L. Deephouse, S.X. Li; Ownership and performance of professional service firms; Organization Studies, 28 (2007), pp. 219–238

- Greenwood and Empson, 2003 R. Greenwood, L. Empson; The professional partnership: relic or exemplary form of governance?; Organization Studies, 24 (2003), pp. 909–933

- Hitt et al., 2001 M.A. Hitt, L. Bierman, K. Shimizu, R. Kochhar; Direct and moderating effects of human capital on strategy and performance in professional service firms: a resource-based perspective; Academy of Management Journal, 44 (1) (2001), pp. 13–28

- Kim and Arditi, 2010 A. Kim, D. Arditi; Performance of minority firms providing construction management services in the US transportation sector; Construction Management and Economics, 28 (8) (2010), pp. 839–851

- Kang and Sorensen, 1999 D.L. Kang, A.B. Sorensen; Ownership, organization and firm performance; Annual Review of Sociology, 25 (1999), pp. 121–144

- Mills et al., 1983 P.K. Mills, J.L. Hall, J.K. Leidecker, N. Margulies; Flexiform: a model for professional service organizations; Academy of Management Review, 8 (1) (1983), pp. 118–131

- Pennings et al., 1998 J.M. Pennings, K. Lee, A. Wiitteloostuijn; Human capital, social capital and firm dissolution; Academy of Management Journal, 41 (1998), pp. 425–440

- Pertusa-Ortega et al., 2010 E.M. Pertusa-Ortega, P. Zaragoza-Saez, E. Claver-Cortes; Can formalization, complexity, and centralization influence knowledge performance?; Journal of Business Research, 63 (3) (2010), pp. 310–320

- Pinnington and Morris, 2002 A. Pinnington, T. Morris; Transforming the architect: ownership form and archetype changes; Organizational Studies, 23 (2) (2002), pp. 189–210

- Schulze et al., 2003 W.S. Schulze, M.H. Lubatkin, R.N. Dino; Toward a theory of agency and altruism in family firms; Journal of Business Venturing, 18 (2003), pp. 473–490

- Wall et al., 2004 T.D. Wall, J. Michie, M. Patterson, S.J. Wood, M. Sheehan, C.W. Clegg, M. West; On the validity of subjective measures of company performance; Personnel Psychology, 57 (1) (2004), pp. 95–118

- Wilhelm and Downing, 2001 W.J. Wilhelm Jr., J.D. Downing; Information Markets: What Business Can Learn from Financial Innovation; Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA (2001)

- Willem and Buelens, 2009 A. Willem, M. Buelens; Knowledge sharing in inter-unit cooperative episodes: the impact of organizational structure dimensions; International Journal of Information Management, 29 (2009), pp. 151–160

- Zhou and De Wit, 2009 H. Zhou, G. De Wit; Determinants and Dimensions of Firm Growth; Scientific Analysis of Entrepreneurship and SMEs (SCALES), Netherlands (2009)

Document information

Published on 12/05/17

Submitted on 12/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?