m (text errors, images) (Tag: Visual edit) |

m (errades de redacció i llengua) (Tag: Visual edit) |

||

| Line 139: | Line 139: | ||

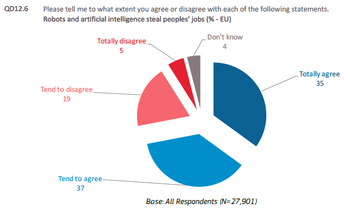

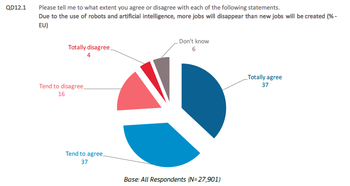

<span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">'''Figure 4''' – Responses to Eurobarometer survey with regard to perception of RAAI impact on work. Source:European Commission</span></div> | <span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">'''Figure 4''' – Responses to Eurobarometer survey with regard to perception of RAAI impact on work. Source:European Commission</span></div> | ||

| − | Employees from developing economies seem more aware and mainly optimistic compared to employees from more developed economies. In Asia-Pacific and Latin | + | Employees from developing economies seem more aware and mainly optimistic compared to employees from more developed economies. In Asia-Pacific and Latin America, there is more awareness of automation, with fewer workers (approximately 1 in 20) stating they don’t know how automation will affect their jobs (Randstad, 2017). People, being more positive toward RAAI impact, are eager to re-train their skills. However, they are less aware of the negative sides of RAAI (Randstad, 2017). |

| − | ====4.1. | + | ===== 4.1.3. The majority of employees around the world is not aware of the impact of RAAI on their job ===== |

| + | Existent research suggests that the majority of potentially affected workers is not aware nor worried about this ongoing transformation process and they are not adequately planning their career (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Randstad, 2017). Despite media coverage, employees across the world are quite unconcerned by the threat of automation, believing it will have no effect on themselves (39%) or make their job better (40%) – (Randstad, 2017). Despite their expectations that technology will negatively impact human employment in general, most workers think that their jobs or professions will still exist in 50 years (Smith, 2015). | ||

| − | + | Over half of employees in Asia Pacific and Latin America believe that automation will make their job better (Randstad, 2017). In contrast, developing economies could be the most affected by RAAI, having the majority of the population working on low-skill/low-pay jobs. In 1986, Kennet already warned developing countries to avoid long-term industrialization strategies centered on the labor-intensive manual assembly of electronic products, where robotization was expected to proceed most quickly (Kennet, 1986). | |

| − | + | In North America and Europe instead, less than a third of employees believe that robots will make their jobs better (Randstad, 2017). The majority of people in the USA, New Zeeland, and Europe are not aware of the impact that RAAI will probably have on their job (Cascio & Montealegre, 2016) and, despite being mainly pessimistic, they are not planning their careers accordingly (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Randstad, 2017). In spite of being worried about the negative impact of RAAI on jobs, 53% of respondents to Eurobarometer (2017), don’t think their job could be done at least in part by a robot or artificial intelligence. On the contrary, one research made in Japan (Morikawa, 2017), shows how employees are more aware of which educational background will reduce the risk to lose jobs. | |

| − | + | Two recent surveys, one conducted by Pew Research Centre (2015) and the other by Gallup (2017), pointed toward the idea that the effects of automation, which are increasingly permeating many aspects of American life, are not apparent to many workers. Only 13% of U.S. workers (Gallup, 2017) indicated they were worried about technology eliminating their job; workers were more than twice as likely to worry about losing benefits (Figure 5). <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | Two recent surveys, one conducted by Pew Research Centre (2015) and the other by Gallup (2017), pointed toward the idea that the effects of automation, which are increasingly permeating many aspects of American life, are not apparent to many workers | + | |

| − | + | ||

| − | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | + | |

[[Image:draft_Rimbau_465905313-image7.png|500px]] </div> | [[Image:draft_Rimbau_465905313-image7.png|500px]] </div> | ||

| Line 163: | Line 160: | ||

<span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">'''Figure 6''' – Responses to Eurobarometer survey with regard to perception of RAAI impact on work. Source:European Commission</span></div> | <span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">'''Figure 6''' – Responses to Eurobarometer survey with regard to perception of RAAI impact on work. Source:European Commission</span></div> | ||

| − | In conclusion, despite what well respected business people, scientists, and academics are predicting, a sizable portion of workers do not perceive RAAI to be a threat | + | In conclusion, despite what well-respected business people, scientists, and academics are predicting, a sizable portion of workers do not perceive RAAI to be a threat to them. |

| − | ===4.2. Impact of RAAI on workers’ well being=== | + | === 4.2. Impact of RAAI on workers’ well being === |

| + | Different theories from previous studies identify critical issues when evaluating the impact of technological transitions on the employees (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Autor, 2015; O’ Connor et al., 1992; Nelson, 1990; Cumming & Marning, 1977; Parson et al., 1991; Frey & Osborne, 2013). Self-image and self-worth, associated to control, autonomy and power, are a particularly relevant (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Autor, 2015; O’Connor et al., 1992; Parson et al., 1991; Nelson, 1990; Cumming & Marning, 1977; Day et al., 2012). When people lose control on their job or feel uncertainty or lack of ability related to RAAI in their workplace, they become increasingly pessimistic, cynic and depressed, and this affects their self-image. This, in turn, has a significant impact on their well-being (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Akintayo, 2010; Cumming & Marning, 1977; Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Schatsky & Schwartz, 2015; Frey & Osborne, 2013; Parson et al., 1991) and leads to turnover intentions, compromising the stability of the organization and the society as well (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Frey & Osborne, 2013; O’Connor et al., 1992; Parson et al., 1991). | ||

| − | + | Many of such adverse impacts may be caused by increased job demands or reduced job resources, which are commonly reported to have a negative effect on employee health and well-being. For example, employees may experience changes in the needed competencies and the addition of new tasks to their traditional job descriptions as stressful. In this vein, Wixted & Sullivan (2017) found that the upward trend of automation in manufacturing increased the requirement for supervisory monitoring and consequently, cognitive demand, which in turn was related distress in employees. A survey to workers in a manufacturing plant that adopted automation showed that they perceived it had reduced human interaction, communication, and clarity of responsibilities (Campagna et al., 2015). On the other hand, automation may also improve working conditions when it eliminates or reduces repetitive and tedious tasks. Campagna et al. (2015), for example, showed that working conditions were perceived as improved. | |

| − | + | Automation may also generate both benefits and disadvantages for employee health and safety. On the one hand, automation has clear potential of reducing accidents in industries such as mining and transportation (IISD and Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment Center, 2016; Lafrance, 2015). Conversely, the potential negative impact of automation on employment might increase the global incidence of mental and physical health issues that are linked to unemployment and job anxiety (BSR, 2014). Indeed, global studies of workers who lost their jobs through mass layoffs have shown that they experienced on average double the risk of developing clinical depression and 4-6 times the risk of developing substance abuse problems and engaging in domestic violence (Brenner et al., 2014). | |

| − | + | Furthermore, the impact of RAAI on individuals may depend on variables such as age, level of studies and skills, department type and occupational category of the technology used (Chao & Kozloswki, 1986; Vietez & Carcia, 2001). For example, Chao & Kozloswki (1986) demonstrated that low-skill workers could react negatively toward the implementation of robots, perceiving them mainly as threats to their job security. High-skill workers responded more positively toward the robots and saw the implementation as providing opportunities to expand their skills. Workers’ career orientation may also impact their view of RAAI. For example, McMurtrey, Grover, Teng, & Lightner (2002) found that technically oriented specialists found CASE tools satisfying, while managerially oriented workers showed decreased job satisfaction with CASE implementation. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | Furthermore, the impact of RAAI on individuals may depend on variables such as age, level of studies and skills, department type and occupational category of the technology used (Chao & Kozloswki, 1986; Vietez & Carcia, 2001). For example, Chao & Kozloswki (1986) demonstrated that low-skill workers could react negatively toward the implementation of robots, perceiving them | + | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | === 4.3. Occupations and a focus on service industries === | ||

It is difficult to reach conclusions about worker perceptions of RAAI in different industries and occupations. More research is indeed needed, and in particular in the service industries since most literature of impact on workers has been conducted in manufacturing environments. Some examples of recent results in service settings are provided below. | It is difficult to reach conclusions about worker perceptions of RAAI in different industries and occupations. More research is indeed needed, and in particular in the service industries since most literature of impact on workers has been conducted in manufacturing environments. Some examples of recent results in service settings are provided below. | ||

| − | + | Pharmacy. Research assessing the impact of robotics on the employment and motivation of employees in the healthcare sector, where mid-level hospital jobs that do not require a bachelor’s degree are quickly disappearing (Qureshi&Syed, 2014), seems particularly necessary. James et al. (2013) reported that installing ADS (Automatic Dispenser System) in the pharmacy area of a national hospital had a positive impact on most of the staff experience of stressors, improving working conditions and workload. Technicians, instead, reported that they felt like ‘production-line workers and their skills. Robot malfunction was, as well, a source of stress. | |

| − | + | Accountants. Rai et al. (2010) conducted a survey about IT knowledge levels among Australian accountants. They concluded that their IT knowledge was lower than their perception towards the importance of these technologies. Accountants had a high IT knowledge in email and communication software, and electronic spreadsheets, while knowledge of systems development and programming tools was low. The most significant alignment between importance and knowledge was in accounting software. On the other hand, the most prominent gap was found in security management skills. Accountants perceived that IT security was essential to their roles; however, they viewed themselves as lacking knowledge in this area. | |

| − | + | Radio and television program production. Rintala and Suolanen (2017) explained how due to digitalization the work processes in the media industry had been changed. According to their results, there had been changes in job descriptions and competency requirements. The job descriptions of journalists became more post-bureaucratic, whereas those of editors remained bureaucratic. The interviewees experienced the changes in competence requirements as both positive and negative regarding the quality working life. On the one hand, the digitalization of production technology offered new learning experiences and increased motivation at work. However, learning to use new technology was also related to experiences of stress. | |

| − | ===4.4. Increasing attention on RAAI impact on employees === | + | === 4.4. Increasing attention on RAAI impact on employees === |

| + | This review found a rising attention on the impact of RAAI on employees by government bodies, international recruiting firms and researchers, with a high number of surveys and results published in 2017 (Eurofund, 2016; Brougham & Haar, 2017; Morikawa, 2017; Randstad, 2017; Swift, 2017; Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2017; Wisskirchen et al., 2017). Some countries and companies in the EU are putting into place experimental programs to bridge the skills gaps (Nelson, 1990; Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Han, 2009; Flamm, 1986; Wisskirchen et al., 2017) and to link the technical knowledge of experienced workers and technicians to the digital factory, and favor knowledge transition to the digital natives (Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Magone & Mazali, 2016; Autor, 2015; Eurofund, 2016) as well as create Digital Leaders to be studied as best practice (Larjovouri et al., 2016; Wisskirchen et al., 2017). | ||

| − | + | ==== 4.4.1. Governmental focus ==== | |

| + | Governmental positions are well represented by EU’s “Foundation Seminar Series 2016: The impact of digitalization on work” (Rodriguez Contrera, 2016), where participants stated their belief that digitalization will generate new opportunities and increase potential growth. Most of the national contributions reported plans and strategies designed to support digital transformation and to exploit the benefits of the new digital era. National teams agreed on the importance of social dialogue to raise awareness about digital challenges and the subsequent implications for working conditions. | ||

| − | + | The European Commission recently acknowledged the need to invest in people to facilitate transitions between jobs. Vocational education, training and access to lifelong learning that focuses on new skills that keep pace with technological development and ease changes from one job to another were highlighted together with the proposal to set up a European Labor Authority (Social Summit for Fair Jobs and Growth, Nov. 2017). Governments must also provide the policy incentives and education systems to support the acquisition of skills necessary to get the jobs created or changed by the deployment of robots and automation. | |

| − | + | These goals will require intensified and coordinated public-private sector collaboration (IFR, 2017). Governments and firms must work to create an environment that will enable workers, companies, and nations to reap the rewards of these improvements. This effort means supporting investments in research and development in robotics and, most importantly, providing education and skills re-training for existing and future workers (IFR, 2017). | |

| − | + | ==== 4.4.2. Organizational focus ==== | |

| − | + | According to a report by Deloitte (Schatsky & Schwartz, 2015), leaders face two core options about how to apply cognitive technologies, namely a cost strategy and a value strategy (Figure 7). “These choices will determine whether their workers are marginalized or empowered and whether their organizations are creating value or merely cutting costs.” When leaders plan to bring cognitive technologies into their organizations, they should consider which set of automation options will be more in line with their talent and competitive strategies.<div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | According to a report by Deloitte (Schatsky & Schwartz, 2015), leaders face two core options about how to apply cognitive technologies, namely a cost strategy and a value strategy (Figure 7). “These choices will determine whether their workers are marginalized or empowered | + | |

| − | + | ||

| − | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | + | |

[[Image:draft_Rimbau_465905313-image9.png|500px]] </div> | [[Image:draft_Rimbau_465905313-image9.png|500px]] </div> | ||

| Line 207: | Line 198: | ||

<span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">'''Figure 7''' – Automation choices vs cost/value strategy. Source: Schatsky & Schwartz (2015), p. 15</span></div> | <span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">'''Figure 7''' – Automation choices vs cost/value strategy. Source: Schatsky & Schwartz (2015), p. 15</span></div> | ||

| − | In any case, if organizations want their automation strategies to succeed, they will need to create and maintain a work environment that encourages innovative | + | In any case, if organizations want their automation strategies to succeed, they will need to create and maintain a work environment that encourages innovative attitudes and behaviors (Larjovouri et al., 2016; Nelson, 1990), and grant adequate training (Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Parson et al., 1991) to handle more complex functions (Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Han, 2009). |

| − | When looking to implement automation strategies, companies should focus on how they will re-train their employees to equip them with appropriate skills, since automation makes | + | When looking to implement automation strategies, companies should focus on how they will re-train their employees to equip them with appropriate skills, since automation makes specific skill sets obsolete (Randstad, 2017; IFR, 2017). Skill re-engineering programs should be organized for workers at regular intervals to make them aware and foster skills acquisition and utilization (Akintayo, 2010). |

| − | Moreover, performance management systems will have to be redesigned too, since individual performance is the degree of task automation. The results of one of Bravo & Ostos research (2017) suggest that “depending on the level of automation, the contribution of knowledge and perceived usefulness on performance change in intensity”. In traditional methods of evaluating performance, good or poor execution of tasks is assumed to be under the responsibility of the individual. In contrast, at high levels of automation, the results may depend | + | Moreover, performance management systems will have to be redesigned too, since individual performance is the degree of task automation. The results of one of Bravo & Ostos research (2017) suggest that “depending on the level of automation, the contribution of knowledge and perceived usefulness on performance change in intensity”. In traditional methods of evaluating performance, good or poor execution of tasks is assumed to be under the responsibility of the individual. In contrast, at high levels of automation, the results may depend mainly on the technology. Thus, new methods to evaluate performance are also necessary (Bravo & Ostos, 2017). |

| − | Future studies should be continued in this area to enable employees, employers, and government/ | + | Future studies should be continued in this area to enable employees, employers, and government/policymakers to prepare for these potential changes (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Vietez & Carcia, 2001). |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | === 4.5. Employee inclusion and inspirational leadership === | ||

Change acceptance and a positive up-skilling of the employees can be promoted by inclusion strategies and inspirational leadership that generate trust, both at political and at organizational level (Akintayo, 2010; Merrit, 2011; Larjovouri et al., 2016; Cumming & Marning, 1977; Lin & Popovic, 2002; Argote & Goodman, 1985; Schatsky & Schwartz, 2015). | Change acceptance and a positive up-skilling of the employees can be promoted by inclusion strategies and inspirational leadership that generate trust, both at political and at organizational level (Akintayo, 2010; Merrit, 2011; Larjovouri et al., 2016; Cumming & Marning, 1977; Lin & Popovic, 2002; Argote & Goodman, 1985; Schatsky & Schwartz, 2015). | ||

| − | ====4.5.1. | + | ==== 4.5.1. Employee inclusion ==== |

| + | To live this technological transition with less anxiety, employees need involvement as stakeholders in the process. This transition also has to include focusing on the positive outcomes, clear job descriptions, get timely training, clear understanding of each individual's fears, a well planned strategy and transparent communication (Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Autor, 2015; Parson et al, 1991; Nelsonl, 1990; Markus & Robey, 1988; Cumming & Marning, 1977; Akintayo, 2010; Merrit, 2011; Day et al., 2012; Larjovouri et al., 2016; Lin & Popovic, 2002; Argote & Goodman, 1985; Chao & Kozlowski, 1986; Fink et al., 1992). | ||

| − | + | Larjovouri et al. (2016) recommended a participatory management style, which could foster workers’ participation at the planning and implementation stages of technological innovation, as well as in decision-making and workers’ supportiveness towards implementation of technological innovations. However, a study realized on a Japanese manufacturing plant in the 80s, demonstrated how workers participation in the process of digitalization had a positive impact only on those involved in the transition. Later generations of employees, not having taken part in the technological change, felt alienated by automatisms and routines (Shodt, 1988). Therefore, new methodologies to ensure a long-term commitment for newcomers are also necessary (Olson & Lucas, 1982). | |

| − | + | ||

| − | Larjovouri et al. (2016) recommended a participatory management style, which could foster workers’ participation at the planning and implementation stages of technological innovation, as well as in decision-making and workers’ supportiveness towards implementation of technological innovations. However, a study realized on a Japanese manufacturing plant in the 80s, demonstrated how workers participation | + | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | ==== 4.5.2. Inspirational leadership ==== | ||

In the context of technological change, many concerns arise from misunderstandings and miscommunications of managerial policies which are based on beliefs and expectations rather than fact and accurate information (Linda Argote & Goodman, 1985). | In the context of technological change, many concerns arise from misunderstandings and miscommunications of managerial policies which are based on beliefs and expectations rather than fact and accurate information (Linda Argote & Goodman, 1985). | ||

| − | During the first stage of a digitalization process, management should not only | + | During the first stage of a digitalization process, management should not only notify employees about the immediate effect that the introduction of RAAI will have on the existing jobs and organizational structure, but it should also inform of the issues that provoked RAAI’s arrival (Fink et al., 1992). By making the employees aware of the need for change, it is hoped that those workers affected by the technological change will accept it as necessary and beneficial (Moniz, 2015). |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | A strategic-level leadership of digitalization along with servant leadership contribute to employee well-being in digital transformations, and together these aspects support digitalization (Larjovouri et al., 2016). In addition to the concept of technostress, some authors suggest that a particular type of work engagement, called “techno-work engagement” may also manifest itself (Larjovouri et al., 2016) under an inspirational leadership style. At a minimum, managers have an obligation to clarify policies regarding technological change so that rumors and false expectations do not dominate (Cunningam et al., 1991). | |

==5. Conclusions== | ==5. Conclusions== | ||

| Line 241: | Line 225: | ||

The advent of RAAI will expose employees to constant and incremental technological advances, and education itself will be probably not enough to keep the pace with it for a large part of the workforce (Autor, 2015; Frey & Osborne, 2013; Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2012). Those individuals able to foresee and anticipate the changes in their future career will be better positioned in the new labor market (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Flamm, 1986; Cumming & Marning, 1977; Akintayo, 2010). | The advent of RAAI will expose employees to constant and incremental technological advances, and education itself will be probably not enough to keep the pace with it for a large part of the workforce (Autor, 2015; Frey & Osborne, 2013; Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2012). Those individuals able to foresee and anticipate the changes in their future career will be better positioned in the new labor market (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Flamm, 1986; Cumming & Marning, 1977; Akintayo, 2010). | ||

| − | But the majority of people seems to be unaware of these | + | But the majority of people seems to be unaware of these significant changes. Thus, they can be at risk of being expelled from the labor market in 5 to 15 years (Frey & Osborne, 2013). Therefore, an awareness campaign and timely planned re-conversion are urgent needs (Autor, 2015; Frey & Osborne, 2013). Each different field and profession will address a specific degree of impact (Frey & Osborne, 2013; Parson et al., 1991), the service sector being the main potentially impacted (Frey & Osborne, 2013; Qureshi, 2014). Governments and companies must focus on providing the right skills to current and future workers to ensure a positive impact of RAAI on employment, job quality and wages (IFR, 2017). More research is required in this area to ensure that employees are well positioned for changes and employers can manage these changes in a positive way (Brougham & Haar,2017). |

Involving the individuals in such transitions has been proved to bring positive results (Parson et al., 1991) and reduce social costs (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Frey & Osborne, 2013; Parson et al., 1991). To get such individual involvement, it will be necessary to identify the correct strategy to motivate change and avoid protests and resistance (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Frey & Osborne, 2013; O’Connor et al., 1992; Han, 2009; Parson et al., 1991; Nelson, 1990; Fink et al., 1992). All stakeholders, including the labor force, have to be part of this dialogue (Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Bosstrom et al., 2016). | Involving the individuals in such transitions has been proved to bring positive results (Parson et al., 1991) and reduce social costs (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Frey & Osborne, 2013; Parson et al., 1991). To get such individual involvement, it will be necessary to identify the correct strategy to motivate change and avoid protests and resistance (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Frey & Osborne, 2013; O’Connor et al., 1992; Han, 2009; Parson et al., 1991; Nelson, 1990; Fink et al., 1992). All stakeholders, including the labor force, have to be part of this dialogue (Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Bosstrom et al., 2016). | ||

| − | To support specific actions based on the peculiarity of each country, industry and company structure, more targeted research on how the interaction with RAAI will affect human work, the organization and the society as a whole | + | To support specific actions based on the peculiarity of each country, industry and company structure, we urgently need more targeted research on how the interaction with RAAI will affect human work, the organization and the society as a whole (Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Markus & Robey, 1988; Chao & Kozlowski, 1986; IEEE Global Initiative, 2017). Both Frey & Osborne’s and OECD’s models, already show evidence of some difference in computerization impact on jobs between countries, and Randstad’s survey points out a significant difference of perception comparing employees from USA and Europe to those from Asia Pacific and Latin America. Country-specific research would also be useful (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Frey & Osborne, 2013; Han, 2009; Flamm, 1986), with a high priority on developing countries and China, which are expected to be the ones most at risk (Flamm, 1986). |

| − | + | Previous studies can provide useful methodologies for future research (Olson & Lucas, 1982; Day et al., 2012; Larjovouri et al., 2016; Argote & Goodman, 1985; Parson et al., 1991). The work by Jarvenpaa et al. (1997) provides an interesting methodology for studying employees’ perception of automation technology implementation. Their longitudinal case study design and 4-years period data collection could be implemented as a methodology for further studies on RAAI impact on individual workers. Parson et al. 1992, offer another model as a framework for human and organizational responses to technologically driven change by focusing the attention on the impact of people’s attitudinal and behavioral responses to technologically driven change (Parson et al., 1992).<span id='_GoBack'></span>. | |

<big>'''References '''</big> | <big>'''References '''</big> | ||

Revision as of 18:48, 19 April 2018

the impact of Robotics, Automation and Artificial Intelligence (RAAI)

at the employee level – a scoping review

b Universitat Oberta de CatalunyaThis research has benefited from the support of Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness. Grant agreement No. DER2017-82444-R, project title "Digitalización y Trabajo: el impacto de la economía 4.0 sobre el empleo, las relaciones laborales y la protección social"

Abstract

Robotics, automation and artificial intelligence (RAAI) are changing how work gets done, but there’s a shortage of research on their impact from the employee’s perspective. Therefore, we conducted a scoping review to explore the existing research to support policymakers’ as well as managers' decisions and to stimulate further research on the aspects that have received less attention. The main conclusions are the following: a) the majority of employees seem not to be aware of the major changes that will occur and do not feel threatened; b) the service industries are probably going to be most affected and therefore further studies addressing different sectors and occupations are needed; c) involving employees in the transition process may give good results and reduce social cost; d) A significantly different perception is observed between employees from Europe and USA and those of Asia - Pacific and Latin America; e) companies should focus on how to train their employees with appropriate skills, which would encourage positive attitudes and behaviours from employees.

Keywords. Robotics, Automation, Artificial Intelligence, Employees’ perspective, Scoping review

(1) Corresponding Author.

1. Introduction

Human activity is characterized by a wide variety of actions (Flam, 1998). Technology advancements have been trying to emulate such functionality with the aim to overcome human tolerance to debilitating human conditions but also to reduce the impact of labor costs (Han, 2009). The ongoing fourth industrial revolution, with sensing and the Internet, allows the Smart Factory to collect data and even make decisions (Magone & Mazali, 2016). In a time when robotics, automation and artificial intelligence (RAAI) are changing how work gets done, these increasing advances in technology, and the fast speed at which changes are happening have attracted academic and non-academic attention on the impact that technological change could have on employment.

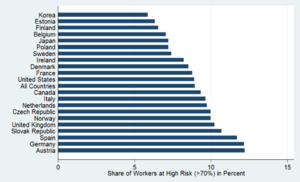

Major research by Frey & Osborne (2013) started an animated debate on the impact that RAAI could have on jobs. Due to the effects of RAAI (Brougham & Haar, 2016), in 10 to 20 years 47% of the existing jobs in the USA could be at risk of becoming redundant (Frey & Osborne, 2013). The main criticism to Frey & Osborne’s study is that it is not work which is at risk but jobs (Bowen, 1966 quoted in Autor, 2015), or mainly specific tasks. Following this task-based approach, the OECD elaborated an updated study on the impact of RAAI in the OECD countries labor market and estimated an average 9% impact, with significant differences by nation (Figure 1) (Arntz et al., 2016). Changes in technology, as well, impact productivity (IFR, 2017) contributing to alter the types of jobs available and what those jobs pay (Autor, 2015; IFR, 2017).

In spite of this significant debate on whether there is a real risk of job losses (Frey & Osborne, 2013; Brzesky & Bart,2015; Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2017; Arntz et al., 2016) or just a need of re-skilling (Autor, 2016; IFR, 2017; Brougham & Haar, 2016), the impact of RAAI on the individual employee has received little attention (Brougham & Haar, 2016; Morikawa, 2017). There is apparently a dearth of research on how employees perceive working within an increasingly automated environment (Brougham & Haar, 2016; Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Frey & Osborne, 2013; O’Connor et al., 1990; Day et al., 2010; Chao & Kozlowzki, 1986) where RAAI can carry out non-routine tasks and interact with human workers at different levels (Han, 2009; Frey & Osborne, 2013; Schatsky & Schwartz, 2016), in some situations even outperforming human workers (Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Schatsky & Schwartz, 2016; Grace et al., 2017). All these trends have a potential effect on employees’ sense of self-worth and career satisfaction and, in turn, on organizations and the society as a whole (Brougham & Haar, 2016; Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Schatsky & Schwartz, 2016; Nelson, 1990; Olson & Lucas, 1982; Akintayo, 2010; Chao & Kozlowzki, 1986; Day et al., 2012; Argote & Godman, 1985; Larjovouri, 2016; Lin & Popovic, 2002). However, little is known about such employee-level impacts due to RAAI.

Motivated by these premises, this paper provides a scoping review of the existing literature on how employees perceive the gradual implementation of RAAI in the workplace. Its ultimate objective is to map the state of the art of research and other types of field studies on the employees’ perception of RAAI impact to their job, as well as to identify specific aspects where new and deeper research is needed. This understanding might help policy makers, workers’ organizations, researchers and managers to better address organizational digitalization for a successful transition in to the new digital era (Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Autor, 2015; Markus & Robey, 1988; O'Connor et al., 1992; Parson et al., 1991) and reduce potential negative outcomes (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Frey & Osborne, 2013; Han, 2009; Fink et al., 1992; Flamm, 1986; Parson et al., 1991).

The following section will present some additional evidence on why the impact of RAAI on jobs could be different from past technological revolutions, making it necessary and urgent to further research on the individual level impacts of this transition. Section two will be detailing the scoping review methodology followed to develop this paper. The last two sections will list the findings and draft relevant conclusions on the existing research on employees’ perception of RAAI impact on jobs, as well as point out areas that require further research.

2. RAAI impact on jobs and the need for individual level research

Keynes already advanced the risk of technological unemployment (Keynes, 1963) and technological anxiety has always been a typical reaction to such changes. However, human labor has been able to adapt to changes through the acquisition of new skills through education (Frey & Osborne, 2013). Some authors argue that this will be challenged by the present technological paradigm due to RAAI. Impacts from RAAI over the next decade are expected to be significant, requiring employees to rethink what constitutes a career and work (Brougam & Haar, 2017).

What is new in this fourth industrial revolution is that automation will not be limited to manual and physical tasks, as it tended to happen in the past. Computing technology is developing toward the contribution to cognitive tasks as well (Frey & Osborne, 2013; Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2011; Cascio & Montealegre, 2016). With the advances in technology and the incremental surpass of different engineering bottlenecks, computerization could be eventually extended to the vast majority of tasks (Frey & Osborne, 2013).

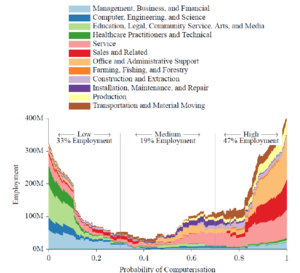

Frey & Osborne’s model identified which jobs were more at risk of automation, resulting in low-skills, low-wage occupations to be the most affected (Frey & Osborne, 2013). Recent research suggests an increasing polarization of the job marker toward the two extremes of low vs. high skills and salaries (Autor et al., 2003; Frey & Osborne, 2013; Arntz et al., 2016; Autor & Price, 2012), with a continual decline in labor input of routine tasks together with an emerging increase of non-routine manual tasks (Autor & Price, 2012) (Figure 2). There is also a potential of creating regional differences within and between countries (Arntz et al., 2016).

As a whole, current research has not reached a consensus about the impact of automation on labor markets (Economist, 2018). In the long term, with increasing technological advance, there is the possibility that RAAI could perform most of the work (Autor, 2015; Frey & Osborne, 2013). Increasingly, non-routine tasks will be taken over by intelligent robots, and routine cognitive tasks will probably be performed by sophisticated artificial intelligence systems (Flamm, 1986). Thus, employees will be likely occupied in abstract tasks (those that require problem-solving, intuition, persuasion and creativity, Autor & Price, 2013) or will need to turn themselves into “new artisans” (Autor, 2015) or ¨augmented workers¨ (Magone & Mazali, 2016), meaning “proactive, dedicated, creative and assuming increasing responsibility”. It is clear, thus, that many jobs will disappear or will change substantially so that a significant reorganization of jobs will take place, affecting high- and low-skilled workers alike (Brynjolfsson et al., 2018). What is not so clear is how are workers perceiving this trend, what is RAAI’s impact on workers of different industries or occupations, and what can governments and organizations do to pave the way for employees’ transition towards an increasingly automated workplace.

3. Methods

This paper presents a scoping review of very diverse sources on the impact of RAAI on individual workers. The scoping review methodology, as opposed to the systematic review, was chosen because it answers broader questions beyond those related to the effectiveness of treatments or interventions (JBI, 2015; Asksey & O'Malley, 2005; Petticrew & Roberts, 2006; Levac et al., 2010).

The research is based on data taken from different papers on the related topics, web portals, public websites of concerned organizations, various journals, professional newspapers, and magazines, as well as public news websites. Substantial information has been gathered from these sources thus allowing for appropriate analysis, compilation, interpretation, and structuring of the entire study. In an attempt to identify and categorize the individual perception of RAAI and its impact on the employees, the selected literature is reviewed and analyzed in this paper.

To conduct this scoping review, a protocol was firstly defined which specified the objectives, inclusion criteria and methods (JBI, 2015; Petticrew & Roberts, 2006) and was adapted throughout the search process. The focus was to identify existing literature on how employees perceive the advent of RAAI in the working environment. With a worldwide scope, all papers covering employees at any organizational level, without any discrimination of industry or degree of automated technology were included.

Following the strategy search criteria for scoping reviews (JBI, 2015), the first search through keywords was conducted in two academic databases accessible from Universidad Oberta de Catalunya (UOC) library: ProQuest ABI/Inform Collect and JSTOR. The used keywords included: employees’ perception + technology and employees’ perception + work automation. Further research was conducted using some of the keywords contained in the titles of the papers found in the initial literature search and by asking experts in the field about relevant references. Additional keywords were identified during the search phase. Through reference harvesting and hand-searching during the paper selection, more relevant literature and authors were identified.

Publications by professional associations as well as opinion articles were included as potential sources for literature and findings. Grey literature search was performed as a final research stage via Agency databases (European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology; Oxford Institute for the Future; OECD), Web search engines (Google, Google Scholar, Bing, Bing Academic, Yahoo), Social networking sites (Research Gate, Accademia, Mendeley), and Professional organizations and associations (PeewResearch Centre - think thank; Torino Nord-Ovest – Social Enterprise).

In a first phase of the research, there was not a limit regarding the date of publication to accept papers and documents. This was so to provide a broader picture of the existing relevant literature and because our review was based on the assumption that recent literature on this topic is limited. Due to the expected reduced amount of recent literature on this topic, similar past surveys and research about technological impact as viewed from the employees’ perspective were included for comparison and suggestions on possible methodologies for future research. A majority of studies focused on the technological change occurred in the 60’s, 80’s and 90’s. In a second phase, the year scope was limited to the last 10-15 years to focus on the most recent technological changes and mainly on the individuals’ perceptions due to increasing use of RAAI in the working environment, resulting in very few academic papers dedicated to this topic before 2011.

The primary language of research was English since the majority of available research has been made by English speaking authors or published in English. The same keywords were translated to Italian, Spanish and French, and were included to broaden the spectrum of the analysis. As expected, the resulting literature obtained through the accessed databases were mainly written in English. Other publications or grey literature were searched for in other languages. Opinion articles and non-academic magazines or website newspapers in Italian, Spanish and French were included randomly.

After the initial listing of articles was obtained, their title, abstracts and (if available) tables of contents were inspected to ensure that they met the following criteria for inclusion:

· Topic: impact of the use of robots and artificial intelligence in the working environment from the perspective of employees

· Participants: employees at any organizational level.

· Context: general (any industry) and global.

Two people were involved in the search and selection of the papers for three months. Included studies were further classified between supportive studies for our background introduction and papers object of revision. Since the fact that automation will have an impact on employment is not under discussion, papers that were focused on justifying this aspect will not be included in the findings selection. The primary focus is on employees’ perceptions and the impact of the technological transition on the employees’ performance and behaviors, as well as how to address this from different perspectives.

All the literature was listed in a table including the following items:

|

Title |

Author and Publication info |

Year |

Subject |

Population |

Design |

Primary Outcome |

The selected literature was mainly identified based on the Subject, Population and Primary Outcome. The authors can provide the mentioned table upon request. Recurring topics and main ideas were identified and grouped to extract the findings for this paper.

4. Findings

Through the collection of papers identified until the moment of submission of this paper, some preliminary results about the perception of RAAI impact from the employees’ perspective have been found. Findings have been grouped into the categories of awareness, impact on worker’s well-being; focus on specific occupations and industries; attention from government bodies and organizations; and employee inclusion and leadership.

A key limitation of the following findings is that research for this paper was limited mainly to English language and had a broad scope, as it wasn’t focused on any geographical area and it didn’t select research on any specific type of workers.

4.1. Awareness

Findings regarding awareness include workers’ ideas about the potential impact of RAAI on the labor market, as well as their perception of the specific impact of RAAI on their own jobs.

4.1.1. Workers around the world are worried about the negative impact of technology on jobs

Findings regarding awareness include workers’ ideas about the potential impact of RAAI on the labor market, as well as their perception of the specific impact of RAAI on their jobs.

4.1.2. Workers around the world are worried about the negative impact of technology on jobs

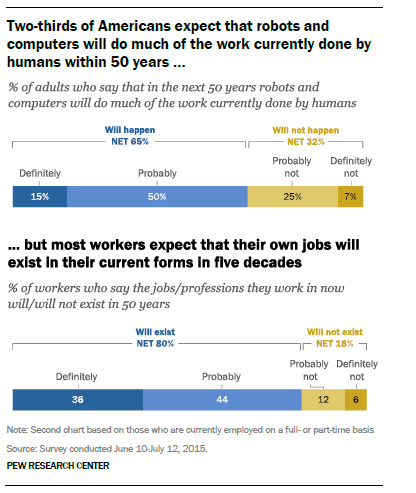

Surveys conducted in different geographical areas support this finding. In a recent Eurobarometer survey dedicated to the European population perception on the impact of robotics and AI, respondents expressed widespread concerns that the use of robots and artificial intelligence would lead to job losses (Figure 4). Europeans seem pessimistic about the impact robots and artificial intelligence have on jobs and in 2017 they were much less likely to say they would be comfortable having a robot assist them at work than they were in 2014 (Eurobarometer, 2017).

Employees from developing economies seem more aware and mainly optimistic compared to employees from more developed economies. In Asia-Pacific and Latin America, there is more awareness of automation, with fewer workers (approximately 1 in 20) stating they don’t know how automation will affect their jobs (Randstad, 2017). People, being more positive toward RAAI impact, are eager to re-train their skills. However, they are less aware of the negative sides of RAAI (Randstad, 2017).

4.1.3. The majority of employees around the world is not aware of the impact of RAAI on their job

Existent research suggests that the majority of potentially affected workers is not aware nor worried about this ongoing transformation process and they are not adequately planning their career (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Randstad, 2017). Despite media coverage, employees across the world are quite unconcerned by the threat of automation, believing it will have no effect on themselves (39%) or make their job better (40%) – (Randstad, 2017). Despite their expectations that technology will negatively impact human employment in general, most workers think that their jobs or professions will still exist in 50 years (Smith, 2015).

Over half of employees in Asia Pacific and Latin America believe that automation will make their job better (Randstad, 2017). In contrast, developing economies could be the most affected by RAAI, having the majority of the population working on low-skill/low-pay jobs. In 1986, Kennet already warned developing countries to avoid long-term industrialization strategies centered on the labor-intensive manual assembly of electronic products, where robotization was expected to proceed most quickly (Kennet, 1986).

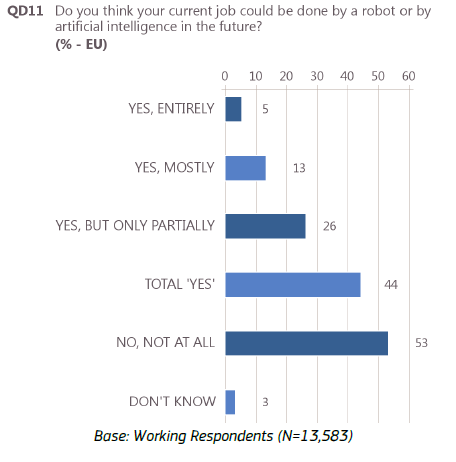

In North America and Europe instead, less than a third of employees believe that robots will make their jobs better (Randstad, 2017). The majority of people in the USA, New Zeeland, and Europe are not aware of the impact that RAAI will probably have on their job (Cascio & Montealegre, 2016) and, despite being mainly pessimistic, they are not planning their careers accordingly (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Randstad, 2017). In spite of being worried about the negative impact of RAAI on jobs, 53% of respondents to Eurobarometer (2017), don’t think their job could be done at least in part by a robot or artificial intelligence. On the contrary, one research made in Japan (Morikawa, 2017), shows how employees are more aware of which educational background will reduce the risk to lose jobs.

Two recent surveys, one conducted by Pew Research Centre (2015) and the other by Gallup (2017), pointed toward the idea that the effects of automation, which are increasingly permeating many aspects of American life, are not apparent to many workers. Only 13% of U.S. workers (Gallup, 2017) indicated they were worried about technology eliminating their job; workers were more than twice as likely to worry about losing benefits (Figure 5).In conclusion, despite what well-respected business people, scientists, and academics are predicting, a sizable portion of workers do not perceive RAAI to be a threat to them.

4.2. Impact of RAAI on workers’ well being

Different theories from previous studies identify critical issues when evaluating the impact of technological transitions on the employees (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Autor, 2015; O’ Connor et al., 1992; Nelson, 1990; Cumming & Marning, 1977; Parson et al., 1991; Frey & Osborne, 2013). Self-image and self-worth, associated to control, autonomy and power, are a particularly relevant (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Autor, 2015; O’Connor et al., 1992; Parson et al., 1991; Nelson, 1990; Cumming & Marning, 1977; Day et al., 2012). When people lose control on their job or feel uncertainty or lack of ability related to RAAI in their workplace, they become increasingly pessimistic, cynic and depressed, and this affects their self-image. This, in turn, has a significant impact on their well-being (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Akintayo, 2010; Cumming & Marning, 1977; Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Schatsky & Schwartz, 2015; Frey & Osborne, 2013; Parson et al., 1991) and leads to turnover intentions, compromising the stability of the organization and the society as well (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Frey & Osborne, 2013; O’Connor et al., 1992; Parson et al., 1991).

Many of such adverse impacts may be caused by increased job demands or reduced job resources, which are commonly reported to have a negative effect on employee health and well-being. For example, employees may experience changes in the needed competencies and the addition of new tasks to their traditional job descriptions as stressful. In this vein, Wixted & Sullivan (2017) found that the upward trend of automation in manufacturing increased the requirement for supervisory monitoring and consequently, cognitive demand, which in turn was related distress in employees. A survey to workers in a manufacturing plant that adopted automation showed that they perceived it had reduced human interaction, communication, and clarity of responsibilities (Campagna et al., 2015). On the other hand, automation may also improve working conditions when it eliminates or reduces repetitive and tedious tasks. Campagna et al. (2015), for example, showed that working conditions were perceived as improved.

Automation may also generate both benefits and disadvantages for employee health and safety. On the one hand, automation has clear potential of reducing accidents in industries such as mining and transportation (IISD and Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment Center, 2016; Lafrance, 2015). Conversely, the potential negative impact of automation on employment might increase the global incidence of mental and physical health issues that are linked to unemployment and job anxiety (BSR, 2014). Indeed, global studies of workers who lost their jobs through mass layoffs have shown that they experienced on average double the risk of developing clinical depression and 4-6 times the risk of developing substance abuse problems and engaging in domestic violence (Brenner et al., 2014).

Furthermore, the impact of RAAI on individuals may depend on variables such as age, level of studies and skills, department type and occupational category of the technology used (Chao & Kozloswki, 1986; Vietez & Carcia, 2001). For example, Chao & Kozloswki (1986) demonstrated that low-skill workers could react negatively toward the implementation of robots, perceiving them mainly as threats to their job security. High-skill workers responded more positively toward the robots and saw the implementation as providing opportunities to expand their skills. Workers’ career orientation may also impact their view of RAAI. For example, McMurtrey, Grover, Teng, & Lightner (2002) found that technically oriented specialists found CASE tools satisfying, while managerially oriented workers showed decreased job satisfaction with CASE implementation.

4.3. Occupations and a focus on service industries

It is difficult to reach conclusions about worker perceptions of RAAI in different industries and occupations. More research is indeed needed, and in particular in the service industries since most literature of impact on workers has been conducted in manufacturing environments. Some examples of recent results in service settings are provided below.

Pharmacy. Research assessing the impact of robotics on the employment and motivation of employees in the healthcare sector, where mid-level hospital jobs that do not require a bachelor’s degree are quickly disappearing (Qureshi&Syed, 2014), seems particularly necessary. James et al. (2013) reported that installing ADS (Automatic Dispenser System) in the pharmacy area of a national hospital had a positive impact on most of the staff experience of stressors, improving working conditions and workload. Technicians, instead, reported that they felt like ‘production-line workers and their skills. Robot malfunction was, as well, a source of stress.

Accountants. Rai et al. (2010) conducted a survey about IT knowledge levels among Australian accountants. They concluded that their IT knowledge was lower than their perception towards the importance of these technologies. Accountants had a high IT knowledge in email and communication software, and electronic spreadsheets, while knowledge of systems development and programming tools was low. The most significant alignment between importance and knowledge was in accounting software. On the other hand, the most prominent gap was found in security management skills. Accountants perceived that IT security was essential to their roles; however, they viewed themselves as lacking knowledge in this area.

Radio and television program production. Rintala and Suolanen (2017) explained how due to digitalization the work processes in the media industry had been changed. According to their results, there had been changes in job descriptions and competency requirements. The job descriptions of journalists became more post-bureaucratic, whereas those of editors remained bureaucratic. The interviewees experienced the changes in competence requirements as both positive and negative regarding the quality working life. On the one hand, the digitalization of production technology offered new learning experiences and increased motivation at work. However, learning to use new technology was also related to experiences of stress.

4.4. Increasing attention on RAAI impact on employees

This review found a rising attention on the impact of RAAI on employees by government bodies, international recruiting firms and researchers, with a high number of surveys and results published in 2017 (Eurofund, 2016; Brougham & Haar, 2017; Morikawa, 2017; Randstad, 2017; Swift, 2017; Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2017; Wisskirchen et al., 2017). Some countries and companies in the EU are putting into place experimental programs to bridge the skills gaps (Nelson, 1990; Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Han, 2009; Flamm, 1986; Wisskirchen et al., 2017) and to link the technical knowledge of experienced workers and technicians to the digital factory, and favor knowledge transition to the digital natives (Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Magone & Mazali, 2016; Autor, 2015; Eurofund, 2016) as well as create Digital Leaders to be studied as best practice (Larjovouri et al., 2016; Wisskirchen et al., 2017).

4.4.1. Governmental focus

Governmental positions are well represented by EU’s “Foundation Seminar Series 2016: The impact of digitalization on work” (Rodriguez Contrera, 2016), where participants stated their belief that digitalization will generate new opportunities and increase potential growth. Most of the national contributions reported plans and strategies designed to support digital transformation and to exploit the benefits of the new digital era. National teams agreed on the importance of social dialogue to raise awareness about digital challenges and the subsequent implications for working conditions.

The European Commission recently acknowledged the need to invest in people to facilitate transitions between jobs. Vocational education, training and access to lifelong learning that focuses on new skills that keep pace with technological development and ease changes from one job to another were highlighted together with the proposal to set up a European Labor Authority (Social Summit for Fair Jobs and Growth, Nov. 2017). Governments must also provide the policy incentives and education systems to support the acquisition of skills necessary to get the jobs created or changed by the deployment of robots and automation.

These goals will require intensified and coordinated public-private sector collaboration (IFR, 2017). Governments and firms must work to create an environment that will enable workers, companies, and nations to reap the rewards of these improvements. This effort means supporting investments in research and development in robotics and, most importantly, providing education and skills re-training for existing and future workers (IFR, 2017).

4.4.2. Organizational focus

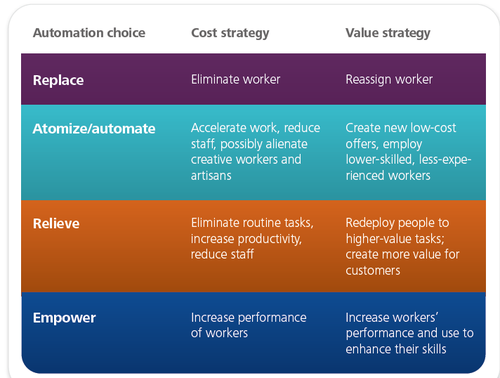

According to a report by Deloitte (Schatsky & Schwartz, 2015), leaders face two core options about how to apply cognitive technologies, namely a cost strategy and a value strategy (Figure 7). “These choices will determine whether their workers are marginalized or empowered and whether their organizations are creating value or merely cutting costs.” When leaders plan to bring cognitive technologies into their organizations, they should consider which set of automation options will be more in line with their talent and competitive strategies.In any case, if organizations want their automation strategies to succeed, they will need to create and maintain a work environment that encourages innovative attitudes and behaviors (Larjovouri et al., 2016; Nelson, 1990), and grant adequate training (Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Parson et al., 1991) to handle more complex functions (Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Han, 2009).

When looking to implement automation strategies, companies should focus on how they will re-train their employees to equip them with appropriate skills, since automation makes specific skill sets obsolete (Randstad, 2017; IFR, 2017). Skill re-engineering programs should be organized for workers at regular intervals to make them aware and foster skills acquisition and utilization (Akintayo, 2010).

Moreover, performance management systems will have to be redesigned too, since individual performance is the degree of task automation. The results of one of Bravo & Ostos research (2017) suggest that “depending on the level of automation, the contribution of knowledge and perceived usefulness on performance change in intensity”. In traditional methods of evaluating performance, good or poor execution of tasks is assumed to be under the responsibility of the individual. In contrast, at high levels of automation, the results may depend mainly on the technology. Thus, new methods to evaluate performance are also necessary (Bravo & Ostos, 2017).

Future studies should be continued in this area to enable employees, employers, and government/policymakers to prepare for these potential changes (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Vietez & Carcia, 2001).

4.5. Employee inclusion and inspirational leadership

Change acceptance and a positive up-skilling of the employees can be promoted by inclusion strategies and inspirational leadership that generate trust, both at political and at organizational level (Akintayo, 2010; Merrit, 2011; Larjovouri et al., 2016; Cumming & Marning, 1977; Lin & Popovic, 2002; Argote & Goodman, 1985; Schatsky & Schwartz, 2015).

4.5.1. Employee inclusion

To live this technological transition with less anxiety, employees need involvement as stakeholders in the process. This transition also has to include focusing on the positive outcomes, clear job descriptions, get timely training, clear understanding of each individual's fears, a well planned strategy and transparent communication (Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Autor, 2015; Parson et al, 1991; Nelsonl, 1990; Markus & Robey, 1988; Cumming & Marning, 1977; Akintayo, 2010; Merrit, 2011; Day et al., 2012; Larjovouri et al., 2016; Lin & Popovic, 2002; Argote & Goodman, 1985; Chao & Kozlowski, 1986; Fink et al., 1992).

Larjovouri et al. (2016) recommended a participatory management style, which could foster workers’ participation at the planning and implementation stages of technological innovation, as well as in decision-making and workers’ supportiveness towards implementation of technological innovations. However, a study realized on a Japanese manufacturing plant in the 80s, demonstrated how workers participation in the process of digitalization had a positive impact only on those involved in the transition. Later generations of employees, not having taken part in the technological change, felt alienated by automatisms and routines (Shodt, 1988). Therefore, new methodologies to ensure a long-term commitment for newcomers are also necessary (Olson & Lucas, 1982).

4.5.2. Inspirational leadership

In the context of technological change, many concerns arise from misunderstandings and miscommunications of managerial policies which are based on beliefs and expectations rather than fact and accurate information (Linda Argote & Goodman, 1985).

During the first stage of a digitalization process, management should not only notify employees about the immediate effect that the introduction of RAAI will have on the existing jobs and organizational structure, but it should also inform of the issues that provoked RAAI’s arrival (Fink et al., 1992). By making the employees aware of the need for change, it is hoped that those workers affected by the technological change will accept it as necessary and beneficial (Moniz, 2015).

A strategic-level leadership of digitalization along with servant leadership contribute to employee well-being in digital transformations, and together these aspects support digitalization (Larjovouri et al., 2016). In addition to the concept of technostress, some authors suggest that a particular type of work engagement, called “techno-work engagement” may also manifest itself (Larjovouri et al., 2016) under an inspirational leadership style. At a minimum, managers have an obligation to clarify policies regarding technological change so that rumors and false expectations do not dominate (Cunningam et al., 1991).

5. Conclusions

The advent of RAAI will expose employees to constant and incremental technological advances, and education itself will be probably not enough to keep the pace with it for a large part of the workforce (Autor, 2015; Frey & Osborne, 2013; Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2012). Those individuals able to foresee and anticipate the changes in their future career will be better positioned in the new labor market (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Flamm, 1986; Cumming & Marning, 1977; Akintayo, 2010).

But the majority of people seems to be unaware of these significant changes. Thus, they can be at risk of being expelled from the labor market in 5 to 15 years (Frey & Osborne, 2013). Therefore, an awareness campaign and timely planned re-conversion are urgent needs (Autor, 2015; Frey & Osborne, 2013). Each different field and profession will address a specific degree of impact (Frey & Osborne, 2013; Parson et al., 1991), the service sector being the main potentially impacted (Frey & Osborne, 2013; Qureshi, 2014). Governments and companies must focus on providing the right skills to current and future workers to ensure a positive impact of RAAI on employment, job quality and wages (IFR, 2017). More research is required in this area to ensure that employees are well positioned for changes and employers can manage these changes in a positive way (Brougham & Haar,2017).

Involving the individuals in such transitions has been proved to bring positive results (Parson et al., 1991) and reduce social costs (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Frey & Osborne, 2013; Parson et al., 1991). To get such individual involvement, it will be necessary to identify the correct strategy to motivate change and avoid protests and resistance (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Frey & Osborne, 2013; O’Connor et al., 1992; Han, 2009; Parson et al., 1991; Nelson, 1990; Fink et al., 1992). All stakeholders, including the labor force, have to be part of this dialogue (Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Bosstrom et al., 2016).

To support specific actions based on the peculiarity of each country, industry and company structure, we urgently need more targeted research on how the interaction with RAAI will affect human work, the organization and the society as a whole (Cascio & Montealegre, 2016; Markus & Robey, 1988; Chao & Kozlowski, 1986; IEEE Global Initiative, 2017). Both Frey & Osborne’s and OECD’s models, already show evidence of some difference in computerization impact on jobs between countries, and Randstad’s survey points out a significant difference of perception comparing employees from USA and Europe to those from Asia Pacific and Latin America. Country-specific research would also be useful (Brougham & Haar, 2017; Frey & Osborne, 2013; Han, 2009; Flamm, 1986), with a high priority on developing countries and China, which are expected to be the ones most at risk (Flamm, 1986).

Previous studies can provide useful methodologies for future research (Olson & Lucas, 1982; Day et al., 2012; Larjovouri et al., 2016; Argote & Goodman, 1985; Parson et al., 1991). The work by Jarvenpaa et al. (1997) provides an interesting methodology for studying employees’ perception of automation technology implementation. Their longitudinal case study design and 4-years period data collection could be implemented as a methodology for further studies on RAAI impact on individual workers. Parson et al. 1992, offer another model as a framework for human and organizational responses to technologically driven change by focusing the attention on the impact of people’s attitudinal and behavioral responses to technologically driven change (Parson et al., 1992)..

References

ACEMOGLU D., AND P. RESTREPO (2017) Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets, MIT.

AKINTAYO, D.I. (2010) “Job Security, Labour-Management Relations and Perceived Workers’ Productivity in Industrial Organizations: Impact Of Technological Innovation”, International Business & Economics Research Journal 9(9).

ARGOTE, L. and P.S. GOODMAN, The Organizational Implications of Robotics, Carnegie Mellon University, 1985.

ARKSEY, H.; and L. O'MALLEY (2005) “Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework”, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, 1, 19-32.

ARNTZ, M., T. GREGORY and U. ZIERAHN (2016), The Risk of Automation for Jobs in OECD Countries: A Comparative Analysis, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Paper 198 .OECD Publishing, Paris

AUTOR, D.H. and B. PRICE (2013) “The Changing Task Composition of the US Labor Market: An Update of Autor, Levy, and Murnane (2003)”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics.

AUTOR, D.H. (2015) “Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 29(3), 3–30.

BOSTROM, N., A. DAFOE and C. FLYNN (2016), Policy Desiderata in the Development of Machine Superintelligence.

BRENNER, M. H, E ANDREEVA, T THEORELL, et al. (2014). “Organizational Downsizing and Depressive Symptoms in the European Recession: Experience of Workers in France, Hungary, Sweden, and the United Kingdom,” PLOS One (May 2014, 9:5): 1-14.

BRAVO, E.R. and J. OSTOS (2017) “Performance in computer-mediated work: the moderating role of level of automation”, Cogn Tech Work 19, 529–541.

BROUGHAM, D. and J. HAAR (2017a) “Employee assessment of their technological redundancy”, Labour & Industry: a journal of the social and economic relations of work.

BROUGHAM, D. AND J. Haar (2017b) “Smart Technology, Artificial Intelligence, Robotics, and Algorithms (STARA): Employees’ perceptions of our future workplace”, Journal of Management & Organization, 1–19.

BROWN, R.B. (2006) Doing Your Dissertation in Business and Management, The Reality of Researching and Writing, SAGE Publications, London.

BRYNJOLFSSON and A. MCAFEE, E. (2012) Race Against The Machine, Digital Frontier Press.

BRYNJOLFSSON, E.; MITCHELL, T.; ROCK, D. (2018) “What can machines learn, and what does it mean for the occupations and industries?”. American Economic Association Annual Meeting. Jan. 6th. Philadelphia, PA, USA.

BRZESKI, C.; I. BURK (2015) The Robots are Coming, Economic Research. ING DiBa.

BSR (2017) Automation: A framework for a sustainable transition. April. Retrieved from https://www.bsr.org/reports/BSR_Automation_Sustainable_Jobs_Business_Transition.pdf

CAMERON, N. (2017) Will robots take your job?, New human frontiers series polity.

CAMPAGNA, L., A. CIPRIANI, L. ERLICHER, P.NEIROTTI, L. PERO, Le persone e la fabbrica. Una ricerca sugli operai Fiat Chrysler in Italia, Saggi GueriniNEXT, 2015.

CASCIO, W.F. and R. MONTEALEGRE (2016), How Technology Is Changing Work and Organizations, Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 3, 349–375.

CHAO, G.T. and S.W.J. KOZLOWSKI (1986) “Employee Perceptions on the Implementation of Robotic Manufacturing Technology”, Journal of Applied Psychology 71(1), 70–76.

CHUTTUR, M.Y. (2009), Overview of the Technology Acceptance Model: Origins, Developments and Future Directions, Working Papers on Information Systems 9(37).

CUMMINGS, T.G. and S.L. MANRING (1977), The Relationship between Worker Alienation and Work-Related Behavior, Journal of Vocational Behavior 10, 167–179.

CUNNINGAM, J.B.; J.FARQUHARSON and D.HULL (1991), “A profile of Human Ferars of Technological change”, Technological Forecasting And Social Change 40, Elsevier Science Publishing Co., Inc., 355-370

DAY, A.; N. SCOTT, S. PAQUET and L. HAMBLEY (2012), Perceived Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Demands on Employee Outcomes: The Moderating Effect of Organizational ICT Support, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 17(4), 473–491.

E. Di NUCCI and F.S. de SIO (2014), Who’s Afraid of Robots? Fear of Automation and the Ideal of Direct Control, Pisa University Press, Pisa.

ECONOMIST (2018) “Economists grapple with the future of the labour market”. Jan 11th. Retrieved on Jan 20th from https://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21734457-battle-between-techno-optimists-and-productivity-pessimists?utm_content=bufferd022f&utm_medium=social&utm_source=linkedin.com&utm_campaign=buffer

EDWARDS, C.; A. EDWARDS, P.R. SPENCE and D. WESTERMAN (2016) “Initial Interaction Expectations with Robots: Testing the Human-To-Human Interaction Script”, Communication Studies 67(2), 227–238.

ELLIOT, S.W. (2016), The challenge computer pose to work and education, Computers and the Future of Skill Demand, OECD Publishing, Paris, Chapter1 and Chapter 5.

EUROFOUND (2016), Foundation Seminar Series 2016: The impact of digitalisation on work, Eurofound, Dublin.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2016), Social Summit for Fair Jobs and Growth.Concluding report. European Commission, Stockolm, November.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2017), Attitudes towards the impact of digitisation and automation on daily life, Special Eurobarometer 460, Wave EB87.1 – TNS opinion & social, May

FINK, R.L., R.K. ROBINSON AND W.B. ROSE Jr. (1992), “Reducing Employee Resistance to Robotics: Survey Results on Employee Attitudes”, International Journal of Manpower 13(1), 59–63.

FLAMM, K. (1986) International Differences in Industrial Robot Use: Trends, Puzzles, and Possible Implications for Developing Countries, The Brookings Institution, Washington D.C.,

GRACE, K.; J. SALVATIER, A. DAFOE, B. ZHANG and O. EVANS (2017), When Will AI Exceed Human Performance? Evidence from AI Experts. Future of Humanity Institute. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/pdf/1705.08807.pdf

HAN, C. (2009) “Human-Robot Cooperation Technology”, An Ideal Midway Solution Heading Toward The Future Of Robotics And Automation In Construction, Keynote III,13–18.

IEEE (2017) Ethically Aligned Design (EAD) - Version 2. A Vision for Prioritizing Human Well-being with Autonomous and Intelligent System, retrieved on Jan. 10th 2018 from http://standards.ieee.org/develop/indconn/ec/auto_sys_form.html

IFR (2017) The Impact of Robots on Productivity, Employment and Jobs, A positioning paper by the International Federation of Robotics, May. Retrieved from https://ifr.org/ifr-press-releases/news/position-paper

IISD AND COLUMBIA CENTER ON SUSTAINABLE INVESTMENT CENTER. (2016) “Mining a Mirage.” IISD and Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment Center, Sept. Retrived from: http://ccsi.columbia.edu/files/2015/07/mining-a-mirage-CCSI-IISD-EWB-2016.pdf.

JAMESA, K.L., D. BARLOWB, A. BITHELLD, S. HIOME, S. LORDD, P. OAKLEYC, M. POLLARDD, D. ROBERTSF, C. WAYG and C. WHITTLESEAB (2013) The impact of automation on pharmacy staff experience of workplace stressors, International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 21, 105–116.

JÄRVENPÄÄ, E. (1997) “Implementation of Office Automation and Its Effects on Job Characteristics and Strain in a District Court”, International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 9(4), 425–442.

JBI (2015), Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2015 edition, Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews, JBI.

KEYNES, J.M. (1963) Essays in Persuasion, W.W.Norton & Co., New York, 1963.

LARJOVUORI, R., L. BORDI, J. MÄKINIEMI and K. HEIKKILÄ-TAMMI (2016), The Role Of Leadership And Employee Well-Being In Organizational Digitalization, 26th Annual RESER Conference, 1159–1172.

LEVAC, D.; H. COLQUHOUN, K. K O’BRIEN (2010) “Scoping studies: advancing the methodology”, Implementation Science, 5-69

LIN, Z. and A. POPOVIC (2002), The Effects of Computers on Workplace Stress, Job Security and Work Interest in Canada, Human Resources Development Canada Publications Centre,Quebec.

LITTELL, J.H.; J. CORCORAN, V. PILLAI (2008), Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis, Oxford University Press, New York.

MAGONE A. and T. MAZALI (2016) Industria 4.0 Uomini e macchine nella fabbrica digitale, Edizioni Guerini e Associati, Milan.

MCMURTREY, M. E., GROVER, V., TENG, J. T., & LIGHTNER, N. J. (2002). Job satisfaction of information technology workers: The impact of career orientation and task automation in a CASE environment. Journal of Management Information Systems, 19(2), 273-302.

MERRITT, S.M. (2011) “Affective Processes in Human–Automation Interactions”, Human Factors 53(4), 356–370.

MOKYR, J.; C. VICKERS, and N.L. ZIEBARTH (2015), “The History of Technological Anxiety and the Future of Economic Growth: Is This Time Different?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 29(3), 31–50.

MONIZ, A.B. (2013) “Robots and humans as co-workers? The human-centred perspective of work with autonomous systems”, IET Working Papers Series 3.

MORIKAWA, M. (2017) “Who Are Afraid of Losing Their Jobs to Artificial Intelligence and Robots? Evidence from a survey”, GLO Discussion Paper 71.

NELSON D.L. (1990), “Individual adjustment to information-driven technologies: A critical review”, MIS Quarterly 14, 79–98.

O’CONNOR, E.J.; C.K. PARSON and R.C. LIDEN (1992) “Responses to New Technology: A Model For Future Research”, The Journal of High Technology Management Research 3(1), 111–124.

OCDE (2016), Automatisation et travail indépendant dans une économie numérique, Synthèses sur l’avenir du travail, Éditions OCDE, Paris.

OLSON, M.H. and H.C. LUCAS Jr. (1982), The Impact of Office Automation on the Organization: Some Implications for Research and Practice, Communications of the ACM 25(11).

OSBORNE, M.A. and C.B. FREY (2013), The Future Of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs To Computerisation?, University of Oxford.

PARSONS, C. K.; R. C. LIDEN, E. J. O’CONNOR and D. NAGAO. (1991) “Employee Responses to Technologically-Driven Change: The Implementation of Office Automation in a Service Organization”. Human Relations, Vol. 44, N. 12

PETTICREW, M. and H. ROBERTS (2006), Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences, Blackwell Publishing, UK.

QURESHI, M.O., R.S. SYED (2014), The Impact of Robotics on Employment and Motivation of Employees in the Service Sector, with Special Reference to Health Care, Safety and Health at Work 5, 198–202.

RAI, P., S. VATANASAKDAKUL and C. AOUN (2010), "Exploring perception of IT skills among Australian accountants: An alignment between importance and knowledge", AMCIS 2010 Proceedings 153 .

RANDSTAD (2017), Randstad Employer Brand Research 2017, Global report, Randstad.

RINTALA, N. and S. SUOLANEN (2017), The Implications of Digitalization for Job Descriptions, Competencies and the Quality of Working Life, De Gruyter Open, 53–67.

SCHAEFER, K.E.; J.Y.C. CHEN, J.L. SZALMAAND P.A. HaNcOck (2016) A Meta-Analysis of Factors Influencing the Development of Trust in automation: Implications for Understanding Autonomy in Future Systems, Human Factors 58(3), 377–400.

SCHATSKY, D. and J. Schwartz (2015). “Redesigning Work In An Era Of Cognitive Technologies”, Deloitte Review 17.

SHODT, F.L. (1988) Inside the Robot Kingdom. Japan, Mechatronics and the coming robotopia, Japan, Mechatronics and the coming robotopia

SMITH, A. (2016) Public Predictions for the Future of Workforce Automation, Pew Research Center.