Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

This paper analyzes the representation of children’s gender in toy advertising on television during three different periods. To achieve our purpose, this study examines seven variables: Toy typologies, Gender, Values, Voiceovers, Period, Actions depicted and Interaction between characters. These variables are taken from previous works that have studied the uses and preferences in toy selection according to gender, and research that studies the ways in which advertising represents children and toys. The sample comprises 595 toy commercials broadcast on the TVE1, TVE2, Telecinco, Antena 3, Cuatro, La Sexta, Boing and Disney Channel television channels. The period of study is October to January 200910, 201011 and 201112. The choice of this period is because most toy commercials are broadcast for Christmas. The most important results are: the percentage of male characters is higher than female characters; the advertising of vehicles and action figures is associated with male characters; the values associated with vehicles and action figures are: competition, individualism, ability, physical development, creativity, power and strength, and the values associated with dolls and accessories are beauty and motherhood.

1. Introduction

The earliest approaches to toys and play appear in Pedagogy and Psychology theory at the start of the 20th century. Pestalozzi wrote of the educational functionality of toys and stated that children should be given toys as a way of encouraging their first experiments because they act as a stimulus for ingenuity and observation (1928: 156). Vygotski said that the most important part of play was not satisfaction but the objective project, even though the child was not conscious of it (2003: 79). Huizinga defined free play as a cultural activity born out of reality but which adapts to the rules set by the players, and in which the child develops an imaginative action since the game is not everyday life but a sphere in which the child knows what to do as if it were so (2005: 25). Erikson provides another classic approach from the Psychoanalysis perspective in which he reflects on the theoretical development of the stages of youth, and concludes that between the ages of four and five the child is rehearsing future social roles through games, dressing up, stories and toys (2004: 144).

A review of the research which is related to our study gives us a state of the question that groups together works according to their objectives. The most important studies on the gender-based uses and preferences in toy selection are Carter & Levy (1988) and Martin, Eisenbud & Rose (1995), whose aims were to measure the influence of social stereotypes in toy selection. They conclude that boys prefer toys that have already been assigned to their gender and reject those that have not. They also noted that boys tended to select toys according to taste in cases where there was no gender stereotyping.

Cherney (2005), Martin, Eisenbud & Rose (1995), Bradbard & Parkman (1983), Bradbard (1985), Miller (1987) and Cherney (2005) analyze the selection preferences of a single gender only, while Francis (2010) draws up categories of toys based on their educational value for children aged between 3 and 5. Cugmas (2010) sustains that a preference towards one toy or another relates to the child’s imitation of the roles or behaviors they observe in their parents. Cherney & Dempsey (2010) study the features and uses of neutral toys compared to toys classified by gender, and conclude that the perception of the physical characteristics of the toy, its behavior and educational application depends on whether it is aimed specifically at boys or girls.

Important studies of advertising’s forms and methods in representing boys and toys include Espinar (2007) and Cherney & London (2006), who identify the differences in the way infant girls and boys are depicted in the media. Other works measure and analyze the degree of regulatory compliance in terms advertising aimed at young children: Pérez-Ugena, Martínez & Salas (2010), Nicolás (2010) and Pérez-Ugena (2008).

Bringué & de los Ángeles (2000) review studies of the subject from the Social Psychology and Cognitive Development perspective. Ruble, Balant & Cooper (1981) conclude that television and advertising influence the child’s cognitive development. Liebert (1986) considers that children who watch a lot of TV have a greater tendency towards violence and stereotypical opinions of race and gender.

Robinson, Saphir & Kraemer (2001) measure the time a group of 8-year-olds spent in front of the TV, watching videos and playing videogames, and determined that those who were less exposed to TV advertising asked for fewer toy purchases from their parents. Pine & Nash (2003) state that 68% of boys and 78% of girls between 4 and 5 who watched a lot of television were favorably impressed by brand-name toys advertised on TV. Pine, Wilson & Hahs (2007) analyze child cognitive and psychological development in relation to the influence of TV content.

Halford, Boyland & Cooper (2008) affirm that obese children tend to watch more TV and consume more of the brand-name products advertised on television than other youth groups. Bakir & Palan (2010) observe children aged between 8 and 9 and note differences in boys and girls in terms of attitude towards advertising, according to the gender and cultural implications of the content. Bakir, Blodgett & Rose (2008) state that the response to advertising stimuli depends not only on gender but also on age.

Keller & Kalmus (2009) consider that the evaluation of brands and the degree of consumption in children in Slovenia was directly related to age, the level of education and economic status, not just to the socializing role that the media can play. Chan & McNeal (2004) state that the effects of advertising stimuli on children aged 6 to 14 in China depended on age, for as they get older they show a greater understanding of the economic relation between advertising and the television channel. Pine & Nash (2002) and Buijzen & Valkenburg (2000) measure the effect of advertising on children’s lists of toy choices sent to Father Christmas or the Magic Kings. Along similar lines, the theoretical base and results provided by Ward, Walkman & Wartella (1977), Young (1990), Kunkel (1992), Steuter (1996) and Smith (1994), among others, are all worthy of note.

Other works directly related to this theme include Browne (1998), who compared advertising in the USA and Australia, concluding that males are projected as wiser, more active, aggressive and instrumental than females, and also that non-verbal conduct in males implied greater control and dominance than in females. Johnson & Young (2002) find that the language used in advertising has a bearing on gender differences and social stereotype representation, while Kahlenberg & Hein (2010) take a sample of 455 spot commercials to investigate the representation of gender stereotypes in minors in advertising on the «Nickelodeon» channel in 2004. This study analyzed stereotypes through gender representation, sexual orientation, age and the color of the surroundings in the advert settings to conclude that there were differences in the representation of children based on gender, in the use of the toys and in the environment of their use and socialization. Indoor contexts were most widely used in adverts for toys aimed at girls and outdoor contexts for boys. Recent research such as the «Study on boys, toys and the Internet» in 2012 looked at the process of toy purchases online. Following this presentation of the state of the question, our study now analyzes the differences in gender representation in TV advertising for toys aimed at infants during three time periods (Christmas 2009, 2010 & 2011).

2. Material and methods

The opening hypotheses are: Hypothesis 1: there are gender differences in the advertising of children’s toys broadcast over Christmas, as seen in the increase in adverts for dolls aimed at girls and for scale-model vehicles and war toys aimed at boys. Hypothesis 2: TV advertising aimed at children foments the differences between boys and girls via stereotyping and the values already associated to each gender. Our sample consists of TV commercials for toys broadcast on TVE1, TVE2, Telecinco, Antena 3, Cuatro, La Sexta, Boing and Disney Channel between October and January 2009, 2010 and 2011. The channels selected are of the general interest type that broadcast nationwide and which transmit programming content aimed at children. Christmas was chosen as it is the period when most toy advertising is broadcast. We eliminated duplications from the sample as well as commercials for videogames since they are governed by specific self-regulatory codes. The final sample consisted of 595 adverts chosen at random over the three-year period analyzed. We developed a content analysis sheet based on Kahlenberg & Hein (2010), Blakemore & Centers (2005), Moreno (2003), Ferrer (2007), the Audiovisual Council of Andalusia, the 2008 CEACCU report, the Self-Regulatory Code for the Advertising of Children’s Toys (1993 and 2011), the Self-Regulatory Code for Television Content and Children and the findings of the Monitoring Commission on Advertising for Children (2003). We took into account the General Law on Audiovisual Communication (7/2010) and the General Law on Advertising (34/1988), and also used these sources to produce a datasheet based on variables such as product type, the gender represented, messages-values, voiceovers, time period, actions represented and interaction between characters. We set up a control group of 10% of the spots, which were analyzed by each codifier. Afterwards, we analyzed all the results in order to avoid codification discrepancies (Kahlenberg & Hein, 2010).

3. Analysis and results

3.1. Toy types

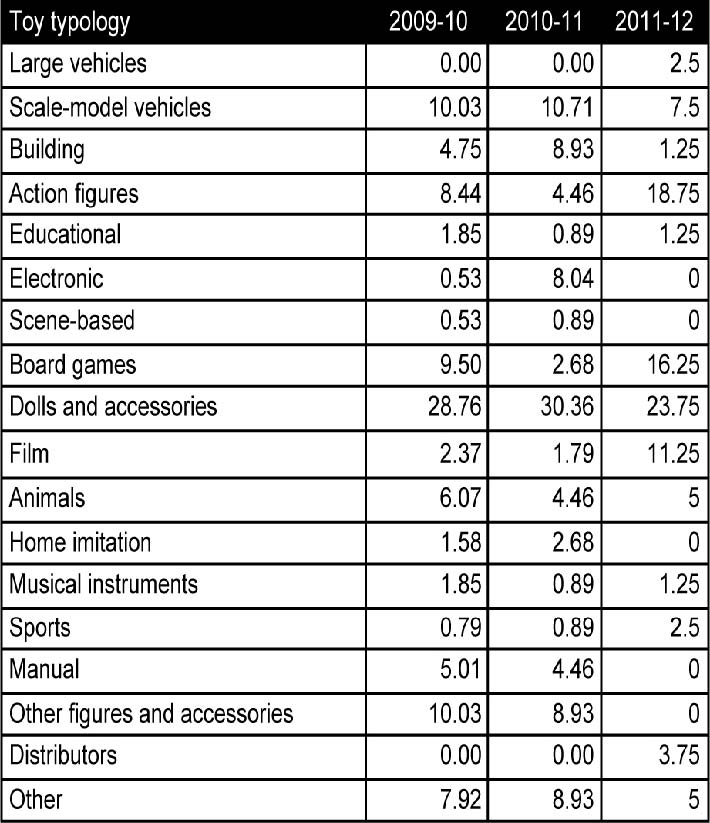

The results show that 77.5% of the adverts focus on just five of toy types: dolls and accessories; action figures; table games; films and scale-model vehicles. The toy type most advertised across the three-year period was dolls and accessories. Advertising for scale-model vehicles and other figures fell in the third year while adverts for action figures, table games and films increased considerably (See table 1).

3.2. Gender representation

The results confirm a tendency to equality in representing each gender because in the last of the three years analyzed the percentage of adverts featuring characters of both sexes increased. In 2009-2010, females represented 36.41% of appearances in adverts to 28.5% for males, with both appearing together in 28.5%. In 2010-2011, the percentage of adverts with females only and those with both sexes were the same (30.36%). In 2011-2012, the percentage of adverts including both sexes increased to 40% while those featuring either boys or girls were less than in the previous two years. There was a significant increase in adverts without actors from 2009-2010 (13.04%) to 19.64% in 2010-2011, although with a slight dip a year later (18.75%) which can be interpreted as a tendency towards neutrality in toy representation. The overlap of variables such as Gender Representation, Period and Toy Types shows that the female presence is concentrated on dolls and accessories, which increased in each period to reach 85.71%. Representation of both genders is found most frequently in board games and dolls and accessories, which rose over the three-year period. Male representation is mainly in adverts for action figures and scale-model vehicles, a fact which yielded an interesting result in our investigation, since the final period (2011-2012) saw a fall to 18.8% in the presence of male doll characters when accompanied by female doll characters.

The representation of females in advertisements in Spain is clearly linked to the values, meanings and roles that advertising associates with the characters represented in this toy typology, along with those of toy animals and musical instruments. The presence of female characters alone, without male characters, is non-existent in all other typologies. This contrasts with the representation of male characters whose presence is spread across the spectrum of toy typologies, which we can assume to mean that the values, meanings and roles associated to male characters are more numerous and varied.

3.3. Voiceovers

The value with the greatest presence over the three-year period is the male voiceover. In 2009-2010, it was 51.9% male to 46.7% female; in 2010-11, 49.11% to 42.85% and in 2011-12, 56.25% to 30%. The relation between the gender of the voiceover and the gender of the characters represented shows a tendency toward the use of voices of both genders combined: 0% in 2009-10, 4.55% in 2010-11 and 15.79% in 2011-12. The same pattern emerges for the female gender, since in 2011-12, 14.29% of adverts which featured only female characters used male and female off-screen voices whereas previously this option had never been used. What particularly stands out is the disappearance of the male voiceover in adverts which exclusively feature females. Although the male voiceover is the most widely used in commercials that feature characters of both sexes, its use fell slightly in the final period in favor of combined voiceovers, which increased: 1.85% in 2009-2010 against 15.63% in 2012.

In toy typology the data on scale-model vehicles particularly stand out. This typology uses the adult male off-screen voice on an average of 79.83% of adverts for this toy. This contrasts with an average of 66.09% of commercials for dolls and accessories which use a female voiceover. The use of male and female voiceovers is similar in proportion for home imitation toys, electronic toys and manual games and animals.

3.4. Values represented

In the analysis of the Values Represented, Interaction between Characters and Actions Represented variables, the data overlapped only for dolls and accessories, scale-model vehicles and action figures, which were the toy typologies that figured most prominently for each gender. The results contrast with the assumptions proposed following the analysis of gender representation. It was assumed that the variety of values and meanings associated with the male gender ought to be greater than the variety of meanings associated with the female gender due to the fact that the male is represented in more toy typologies than the female, yet the data show this assumption to be inaccurate since quantitatively there is more variety in the meanings associated to girls than to boys. The value that figures most prominently in the dolls and accessories and scale-model vehicles typologies is fun (44.5% and 60.7%). In dolls and accessories, the other significant values are beauty, motherhood and friendship, with a limited presence for the values of power, strength, ability and physical development. Power and strength is the value most present in the action figures toy type, with competition in second place; friendship, beauty and eternity do not figure in this typology. For scale-model vehicles, fun is the most prominent value followed by competition and power and strength. We found similar data for action figures, since the friendship value is only present in 7.14% of adverts and beauty and motherhood in only 1.79%. These three typologies scored low, less than 5%, for values such as individualism (1.2% in dolls and accessories, 0% for scale-model vehicles and 3.9% for action figures), ability and physical development (0.6%, 3.6% and 2% respectively) and integration (5% for dolls and accessories and absent in the other two types).

3.5. Actions represented

The actions most widely represented in the dolls and accessories toy type are: affection-nutrition (35.8%), domestic actions and embellishment (both 28.4%), actions which are barely visible or non-existent in adverts that feature male characters. The actions most widely used in adverts for scale-model vehicles and action figures are: competition (32.1%), risk-taking (30.4%) and shows of strength (16.1%). Competition is present in 53% of adverts for action figures followed by strength (51%), with risk-taking actions appearing in 35.3% of cases. Actions that represent specific professions account for less than 10% across all toy typologies.

3.6. Interaction between characters

The lack of interaction between characters is notable in the commercials, especially for action figures (51%) and scale-model vehicles (41.1%). In dolls and accessories, the type of interaction most commonly found is friendship (46.9%) followed by non-interaction (27.1%). In action figures, friendly interactions amount to no more than 9.8% of ads while enmity and fighting account for 15.69%. This type of interaction is found in 5.36% of cases for scale-model vehicles but is non-existent in dolls and accessories. We also find maternal-filial interactions in dolls and accessories (7.4% of ads) but which appear in no other top type. Family interactions occur in 7.1% of commercials for scale-model vehicles, in 6.2% for dolls and accessories but they are absent from all action figure commercials.

4. Discussion and conclusions

In Hypothesis 1, the representation of infant genders in advertising for children’s toys according to the toy typology advertised varies greatly. Although parity in gender representation increased over the three years, this is restricted mainly to adverts for electronic toys, toys for manual play and toy animals. Female characters predominate in adverts for dolls and accessories although more male characters were starting to appear in supporting roles. Male characters are more often found in commercials for building toys, scale-model vehicles and action figures. These results tie in with works by Blackmore, LaRue & Olejnik (1979), Carter & Levy (1988), Martin, Eisenbud & Rose (1995), Campbell, Shriley, Heywood & Crook (1988) and Serbin, Poulin-Dubois, Colburne, Sen & Eischted (2001), who all concluded that toy selection is determined by gender and age. Young boys prefer toys that involve dexterity and spatial skills while girls look for dolls and educational toys. These conclusions also match those of works on gender in primates such as Alexander & Hines (2002). In terms of other types of studies, such as Freeman (2007), Cugmas (2010) and Blackmore & Centers (2005), which examined the influence of parents and teachers and their roles in children’s toy selection, our research reaffirms that the male voiceover is used more than the female, which suggests that the male voice is still considered more socially legitimate. Gender segmentation is apparent in that the female voice predominates in adverts which feature girls and the male voice for boys, while the male voice is heard in ads in which both boys and girls appear. The presence of adults in toy advertising is virtually non-existent; and then only in ads for board games and for electronic toys in which the father puts in an appearance. Self-regulatory codes and positive legislation insist on parity in gender representation and the avoidance of sexist content in advertising for minors, yet differences in the main toy typologies continue to exist although it is fair to say that gender representation is becoming more equal. Hypothesis 2 states that advertising for toys aimed at children resorts to values and stereotypes that vary according to the gender of the characters represented and the toy type being advertised, as indicated by Johnson & Young (2002) and Blackmore & Centers (2005). The values associated to both genders and disseminated across the toy typology spectrum are: fun, education, solidarity and individualism. However, more common are the values clearly differentiated by gender. Beauty is linked to the dolls and accessories toy type while this value appears in only 1.7% of commercials for scale-model vehicles. Motherhood and seduction appear in equal proportion in commercials for girls. For boys, ability and physical development are associated to scale-model vehicles and the male gender in 3.57% of cases, which is low, yet in 50% of commercials in which this value appears it is associated to this toy type and to this gender. The power and strength value features in 19.64% of commercials for scale-model vehicles and in 72.55% for action figures while it is only apparent in 0.62% of commercials for dolls and accessories. The competition value also shows clear differences in gender representation. In 93.75% of commercials it is linked to male characters. It appears in 25% of ads for scale-model vehicles and action figures but is marginal (1.23%) in dolls and accessories. Our study also shows that physical beauty, domesticity and motherhood are values that are widely represented in ads for girls’ toys. Although the motherhood value could be justified on physiological grounds and progenitor imitation, the use of beauty as a value linked exclusively to the female gender could be construed as a social message that inseparably connects beauty and women. Likewise, the use of the power and strength value in commercials aimed at boys contributes to a social discourse that promotes the differences between ability and qualities associated to each gender.

The advertisements for children’s toys encourage message types that tell girls to nurture their beauty and boys to concentrate on their power and strength. This is reinforced by voiceovers spoken in exaggerated tones, as indicated by Klinnder, Hamilton & Cantrell (2001), Johnson & Young (2002) and Del Moral (1999), and shows that advertising contributes to social representation and gender differentiation, as stated by Belmonte & Guillamón (2008), and influences the responsibility and social function of advertising in terms of culture configuration. The study of gender representation figures constantly in academic research, and from the functionalist perspective of communication studies advertising is also to be understood as an instrument in social education.

Teachers and communicators must denounce those practices that encourage social discrimination based on gender. If advertising responds to a shift in social behavior which, thanks to the consumer, benefits the advertiser, shouldn’t the advertising industry repay society by promoting social change that leads to greater gender equality? If, as previous works have shown, toys are fundamental instruments in the child’s social and cognitive development then legislation must insist that toy advertisers promote a more equal representation of gender and with greater variety because there are clear differences in gender representation between toy commercials for boys and girls.

From the educational viewpoint, toy advertising for children must encourage toy presentation from a more neutral perspective, more centered on the product than on symbolic stimulation via consumer representation/identification. An example of this was in Sweden during Christmas 2012, when a well-known brand of toys produced a unisex catalogue of toys that promoted the toys in their own right rather than from a gender perspective. It showed a girl firing a gun and a boy rocking a baby to sleep (Castillo, 2012). This could be a means of change towards social transformation, and it is a challenge that advertisers ought to take up.

References

Alexander, G. & Hines, M. (2002). Sex Differences in Response to Children´s Toys in Nonhuman Primates. Evolution an Human Behavior, 23, 469-479.

Almeida, D. (2009). Where Have All the Children Gone? A Visual Semiotic Account of Advertisements for Fashion Dolls. Visual Communication, 8, 4, 481-501.

Bakir, A. & Palan, K. (2010). How Are Children's Attitudes toward Ads and Brands Affected by Gender-related Content in Advertising? Journal of Advertising, 39, 35-48.

Bakir, A., Blodgett,, J. & Rose G. (2008). Children's Responses to Gender-role Stereo-typed Advertisements. Journal of Advertising Research, 48, 2, 255-266.

Belmonte, J. & Guillamón, S. (2008). Co-educar en la mirada contra los estereotipos de género en TV. Comunicar, 31, 115-120.

Blackmore, J., LaRue, A.A. & Olejnik, A.B. (1979). Sex-appropriate Toy Preference and the Ability to Conceptualize Toys as Sex-role Related. Development Psychology, 15, 339- 340.

Blakemore, J. & Centers, R. (2005). Characteristics of Boys´and Girls´toys. Sex Roles. 53, 619-633.

Bradbard, M. & Parkman, S.A. (1985). Gender Differences in Preschool Children Toy Request. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 145, 283-284.

Bradbard, M. (1985). Sex Differences in Adults´gifts and Childres´s Toy Request at Christmas. Psychological Reports, 56, 691-696.

Bringué, X. & De Los Ángeles, J. (2000). La investigación académica sobre la pu-blicidad, televisión y niños: antecedentes y estado de la cuestión. Comunicación y Sociedad, 13, 37-70.

Browne, B. (1998). Gender Stereotypes in Advertising on Children's Television in the 1990s: A Cross-national Analysis. Journal of Advertising, 27, 83-96.

Buijzen M. & Valkenburg, P. (2000). The Impact of Television Advertising on Chil-dren's Christmas Wishes. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 44, 3, 456-470.

Campbell, A., Shriley L. & al. (2000). Infants´ Visual Preference for Sex-congruent Ba-bies, Children, Toys and Activities: A Longitudinal Study. British Journal of Development Psychology, 18, 4, 479-498.

Carter, D. & Levy, G. (1988). Cognitive Aspects of Early Sex-role Development: The Influence of Gender Schemas on Preschoolers´memories and Preferences for Sex-typed Toys and Activities. Child Development, 59, 3, 782-792.

Castillo, M. (2012). Una campaña por el unisex. El País. (www.sociedad.elpais.com/-sociedad/2012/11/26/actualidad/1353935100_752317.html) (26-11-2012).

Chan K. & McNeal J. (2004). Children's Understanding of Television Advertising: A Revisit in the Chinese Context. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 165, 1, 28-36.

Cherney, D.I. & Dempsey, J. (2010). Young Children's Classification, Stereotyping and Play Behaviour for Gender Neutral and Ambiguous Toys. Educational Psychology, 30, 651-669.

Cherney, D.I. & London, K. (2006). Gender-linked Differences in the Toys, Television Shows, Computer Games, and Outdoor Activities of 5-to 13-year-old Children. Sex Roles, 54, 9-10, 717-726.

Cherney, D.I. (2005). Children´s and Adults Recall of Sex-stereotyped Toy Pictures: Effects of Presentation and Memory Task. Infant and Children Development, 4, 1, 11-27.

Consejo Audiovisual de Andalucía (Ed.) (2008). Estudio sobre la publicidad de juguetes campaña de navidad 2006-2007. Grupo de Trabajo de Infancia del Consejo Audiovisual de Andalucía (www.consejoaudiovisualdeandalucia.es ) (15-11-2009).

Cugmas, Z. (2010). Playing with Gender Stereotyped Toys. Didactica Slovenica-peda-goska Obzorja, 25, 130-146.

Del Moral, M.E. (1999). La publicidad indirecta de los dibujos animados y el consumo infantil de juguetes. Comunicar, 13, 220-224.

Erikson, E.H. (1995). Sociedad y adolescencia. México: Siglo XXI.

Espinar, E. (2007). Estereotipos de género en los contenidos audiovisuales infantiles. Comunicar, 29, 129-134.

Ferrer, M. (2007). Los anuncios de juguetes en la campaña de Navidad. Comunicar, 29, 135-142.

Francis, B. (2010). Gender, Toys and Learning. Oxford Review of Education, 36, 325-344.

Freeman, N.K. (2007). Preeschoolers´ Perceptions of Gender Appropriate Toys and their Parents´ Beliefs about Genderized Behaviors: Miscommunication, Mixed Messages, or Hidden Truths? Early Childhood Education Journal, 34, 5, 357-366.

Halford J., Boyland, E., Cooper, G. & al. (2008). Children's Food Preferences: Effects of Weight Status, Food Type, Branding and Television Food Advertisements (Commercials). International Journal of Pediatric Obesity, 3, 1, 31-38.

Huizinga, J. (2005). Homo ludens: El juego y la cultura, México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Jonhson, F.L. & Young, K. (2002). Gendered Voices in Children’s Television Ad-vertising. Critical Studies Media Communication, 19, 461-480.

Kahlenberg, S.G. & Hein, M.M. (2010). Progression on Nickelodeon? Gender-Role Stereotypes in Toy Commercials. Sex Roles, 62, 830-847.

Keller M. & Kalmus, V. (2009). Between Consumerism and Protectionism Attitudes towards Children, Consumption and the Media in Estonia Childhood. Global Journal of Child Research, 16, 3, 355-375.

Klinnder, L., Hamilton, J. & Cantrell, P. (2001). Children's Perceptions of Aggressive and Gender-specific content in toy commercials. Social Behavior and Personality, 29, 11-20.

Kunkel, D. (1992). Children Television Advertising in the Multichannel Environment. Journal of Communication, 42, 3, 265.

Liebert, R. (1986). Effects of Television on Children and Adolescents. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 7, 1, 43-48.

Martin, C.L., Eisenbud, L. & Rose, H. (1995). Children´s Gender-based Reasoning about Toys. Child Development, 66, 1457-1458.

Miller, C. (1987). Qualitative Differences among Gender-sterotyped Toys: Implications for Cognitive and Social Development in Girls and Boys. Sex Roles, 16, 473-487

Moreno, I. (2003). Narrativa audiovisual Publicitaria. Barcelona (España): Paidós.

Pérez-Ugena, A, (2008). Youth TV Programs in Europe and the U. S. Research Case Study Spanish Television. Doxa, 7, 43-58.

Pérez-Ugena, A., Martinez, E, & Perales, A. (2010). La regulación voluntaria en materia de publicidad: análisis y propuestas de mejora a partir del estudio del caso PAOS. Telos, 88, 130-141.

Pérez-Ugena, A., Martinez, E. & Salas, A. (2011a). Publicidad y juguetes: Análisis de los códigos deontológicos y jurídicos. Pensar la Publicidad, 4, 2, 127-140.

Pérez-Ugena, A., Martinez, E. & Salas, A. (2011b). Los estereotipos de género en la publicidad de los juguetes. Ámbitos, 20, 217-235.

Pestalozzi, J.H (1928). Cartas sobre la educación primaria dirigidas a J.P. Greaves. Madrid: La Lectura.

Pine, K. & Nash, A. (2003). Barbie or Betty? Preschool Children's Preference for Branded Products and Evidence for Gender-linked Differences. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 24, 4, 219-224.

Pine, K., Wilson, P. & Nash, A. (2007). The Relationship between Television Adver-tising, Children's Viewing and their Requests to Father Christmas. Journal of De-velopmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 28, 6, 456-461.

Robinson, T., Saphir M., Kraemer H. & al. (1981). Effects of Reducing Television Viewing on Children's Requests for Toys: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 22, 3, 179-184.

Ruble, D., Balaban, T. & Cooper, J. (1981). Gender Constancy and the Effects of Sex-typed Televised Toy Commercials. Child Development, 52, 2, 667-673.

Serbin, L.A., Poulin-Dubois, D., Colburne, K.A. & al. (2001). Gender Stereotyping in Infancy: Visual Preferences for and Knowledge of Gender-stereotyped Toys in the Second Year. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 25, 7-15.

Smith, L.J. (1994). A Content-analysis of Gender Differences in Children Advertising. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 38, 323-337.

Steuter, E. (1996). Out of the Garden: Toys and Children'sculture TV Advertising. Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, 33, 112-114.

The Cocktail analkysis, AIB, AEFJ (2012). El rol de Internet en la compra de juguetes.

Tur, V. & Luis Martínez, J. (2012). El color en spots infantiles: Prevalencia cromática y relación con el logotipo de marca. Comunicar, 38, 157-165.

Vygotski, L.S. (2003). La imaginación y el arte en la infancia. Madrid: Akal.

Ward, S., Walkman D.B. & Wartella, E. (1997). How Children Learnt to Buy. Beverly Hills (USA): Sage Publications.

Young, B.M. (1990) Television Advertising and Children. Oxford (Reino Unido): Oxford University Press.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Este trabajo analiza la representación de los géneros en la publicidad infantil española mediante el estudio de siete variables: tipos de productos, género representado, mensajesvalores, voz en off, periodo, acciones representadas e interacción entre personajes. Estas variables se recogen de trabajos que estudian los usos y las preferencias de selección de los juguetes según el género del niño y de estudios que analizan los modos y formas de la publicidad para representar a los niños y a los juguetes. El universo de la muestra lo constituyen 595 anuncios de juguetes emitidos en los canales de televisión: TVE1, TVE2, Telecinco, Antena 3, Cuatro, La Sexta, Boing y Disney Channel durante tres periodos de tiempo: Navidades de 2009, 2010 y 2011. Se ha escogido la Navidad ya que durante este periodo se emiten la gran mayoría de los anuncios de juguetes. Los resultados demuestran que, aunque hay paridad en la representación de género en la publicidad infantil de la muestra analizada, existen claras diferencias en las tipologías de los juguetes más anunciados. La publicidad de figuras de acción alberga mayor porcentaje de personajes masculinos asociados a valores como competencia, individualismo, habilidad y desarrollo físico, creatividad, poder y fuerza. Sin embargo, los anuncios de muñecas tiene mayor porcentaje de personajes infantiles femeninos y estos se asocian a los valores belleza y maternidad.

1. Introducción

Entre los primeros planteamientos acerca del juego y el juguete se encuentran los fundamentos teóricos de la Pedagogía y la Psicología de la primera mitad del siglo XX. Así, Pestalozzi, respecto a la funcionalidad educativa de los juguetes, afirmó que era conveniente proporcionar a los niños juguetes para fomentar los primeros ensayos ya que estos actuaban como un estímulo para la ingeniosidad y la observación (1928: 156). Por su parte, Vygotski afirmaba que lo principal en el juego no era la satisfacción sino el proyecto objetivo, aún cuando este fuera inconsciente para el niño (2003: 79). Huizinga definió el juego libre como una actividad cultural que nace de la realidad pero que se adaptaba a la reglas marcadas por los jugadores y en la que el niño desarrollaba una acción imaginativa, ya que el juego no era la vida corriente sino una esfera en la que el niño sabe que hace como sí (2005: 25). Otro enfoque clásico es el que desde la perspectiva psicoanalítica planteó Erikson, quien en sus reflexiones sobre el desarrollo teórico de las etapas de la juventud concluyó que entre los cuatro y los cinco años de vida el niño practicaba los futuros roles sociales mediante juegos, disfraces, cuentos y juguetes (2004: 144).

De la revisión de las diferentes investigaciones relacionadas con este trabajo resulta un estado de la cuestión que expone los trabajos agrupados según el objeto de estudio. Entre los trabajos que estudian los usos y preferencias de selección de los juguetes según cada género destacan las aportaciones de Carter y Levy (1988) y Martin, Eisenbud y Rose (1995), cuyos objetos de estudio miden la influencia de los estereotipos sociales en la selección de juguetes. Concluyeron que los niños prefieren los juguetes previamente calificados para su género y rechazaban los contrarios. También concluyeron que los niños seleccionaban los juguetes según sus gustos si estos carecían de un estereotipo sexista.

Cherney (2005), Martin, Eisenbud y Rose (1995), Bradbard y Parkman (1983), Bradbard (1985), Miller (1987) y Cherney (2005) analizaron las preferencias de selección de un solo género. Becky Francis (2010) elaboró categorías de juguetes en función de su valor educativo para niños de 3 a 5 años. Cugmas (2010) sostuvo que las preferencias hacia unos u otros juguetes estaban relacionadas con la imitación que los niños hacen de los roles o comportamientos que observan en sus padres. Mientras que Cherney y Dempsey (2010) estudiaron las características y usos de los juguetes neutros frente a los clasificados por género, para determinar que la percepción hacia las características físicas del juguete, su comportamiento y su aplicación educativa dependía de si estaba o no dirigido hacia un género concreto.

Entre los trabajos que estudian los modos y formas de la publicidad para representar a los niños y a los juguetes destacan Espinar (2007) o Cherney y London (2006), quienes identificaron las diferencias en la representación de los géneros infantiles en los medios de comunicación. Otro grupo de trabajos miden y analizan el grado de cumplimiento de la normativa o ley que regula la publicidad infantil: Pérez-Ugena, Martínez y Salas (2010), Nicolás (2010) o Pérez-Ugena (2008).

Bringué y De-los-Ángeles (2000) señalaron en su trabajo los estudios emprendidos desde la psicología social y el desarrollo cognitivo. Ruble, Balant y Cooper (1981), concluyeron que la televisión y los anuncios influían en el desarrollo cognitivo de los niños. Liebert (1986) consideró que los niños que consumían mucha televisión eran más propensos a actitudes violentas y a opiniones estereotipadas de género y raza.

Robinson, Saphir y Kraemer (2001), tras estudiar el tiempo de exposición a la televisión, el vídeo y los videojuegos por parte de niños de 8 años, concluyeron que los niños con menor exposición a la publicidad audiovisual reducían el número de peticiones de compra. Pine y Nash (2003) afirmaron que el 68% de los niños y el 78% de las niñas, de 4 a 5 años, cuya exposición a la televisión era alta, ofrecían una respuesta favorable hacia productos de marcas que realizan publicidad. Pine, Wilson y Hahs (2007) analizaron el desarrollo cognoscitivo y psicológico del niño en relación a la influencia de los contenidos televisivos.

Halford, Boyland y Cooper (2008) concluyeron que los niños obesos veían más televisión que el resto y consumían más productos de marcas anunciadas en televisión. Bakir y Palan (2010) investigaron a niños de 8 y 9 años para observar las diferencias de actitud, según género, hacia la publicidad en función de las implicaciones culturales y de género que se hacían en sus contenidos. Bakir, Blodgett y Rose (2008) afirmaron que la respuesta a estímulos publicitarios no dependía solo del género, sino también de la edad.

Keller y Kalmus (2009) consideraron que la valoración de las marcas y el grado de consumo de los niños eslovenos estaban directamente relacionados con la edad, el nivel educativo y el nivel económico de los niños y no solo con el papel socializador que podían ejercer los medios de comunicación. Chan y McNeal (2004) afirmaron que los efectos producidos por los estímulos publicitarios en China, en niños de 6 a 14 años, dependían de la edad de los individuos, ya que a medida que aumentaba la edad del sujeto, éste mostraba mayor conocimiento de la relación económica entre la publicidad y el canal televisivo. Los trabajos de Pine y Nash (2002) y Buijzen y Valkenburg (2000) midieron la influencia de la publicidad en la creación de la carta de deseos a los Reyes Magos o Papá Noel. Desde esta perspectiva, también destacan la influencia de la base teórica y los resultados de los trabajos de investigadores como Ward, Walkman y Wartella (1977), Young (1990), Kunkel (1992), Steuter (1996) y Smith (1994), entre otros.

Directamente relacionado con este trabajo destaca Browne (1998), quien comparó la publicidad de USA y Australia y concluyó que el género masculino se proyecta más sabio, activo, agresivo e instrumental que el femenino. También determinó que las conductas no verbales de los personajes masculinos implicaban mayor control o dominio que los femeninos. Johnson y Young (2002) concluyeron que el lenguaje utilizado en la publicidad incidía en diferencias de género y en la representación de estereotipos sociales, mientras que Kahlenberg y Hein (2010) investigaron la representación de los estereotipos de género de los menores en la publicidad emitida en «Nickelodeon», a través de una muestra de 455 spots emitidos en 2004. En este trabajo, se analizaron los estereotipos mediante la representación de género, la orientación sexual, la edad y el color de los entornos, para afirmar que existían diferencias en la representación de los niños según género, en la representación del uso de los juguetes y en el entorno de su utilización y socialización. Los contextos interiores eran los más representados en los anuncios de juguetes dirigidos a niñas y los contextos exteriores en los anuncios dirigidos a niños. Otros estudios más recientes, como el «Estudio sobre niños, juguetes e Internet» de 2012, estudian los procesos de compra de juguetes por Internet. Finalmente, una vez presentado el estado de la cuestión, este trabajo analiza las diferencias de representación de los géneros en la publicidad infantil de juguetes en televisión durante tres periodos distintos (Navidades 2009, 2010 y 2011).

2. Material y métodos

Las hipótesis de partida son: Hipótesis 1: Existen diferencias de género en la publicidad infantil de juguetes emitida durante la Navidad, ya que predominan los anuncios de muñecas dirigidos a niñas y los anuncios de vehículos a escala y juegos de contenido bélico dirigidos a niños. Hipótesis 2: La publicidad infantil en televisión fomenta la diferenciación entre géneros a través de estereotipos y valores asociados previamente a cada género. El universo de la muestra lo constituyen anuncios de juguetes emitidos en los canales de televisión: TVE1, TVE2, Telecinco, Antena 3, Cuatro, La Sexta, Boing y Disney Channel. El periodo de estudio aborda desde octubre a enero de 2009, 2010 y 2011. Se han seleccionado cadenas generalistas que cubren todo el ámbito nacional, y temáticas cuya programación y público son infantiles y se escoge el periodo navideño ya que durante el mismo se emiten la gran mayoría de los anuncios de juguetes. Se han eliminado de la muestra las duplicidades y los anuncios de videojuegos, puesto que se les aplican códigos de autorregulación específicos. La muestra total está formada por 595 anuncios que aleatoriamente se recogieron de los tres años analizados. Se desarrolló una ficha de análisis de contenido siguiendo las aportaciones de otros trabajos como Kahlenberg y Hein (2010), Blakemore y Centers (2005), Moreno (2003), Ferrer (2007), el Consejo Audiovisual de Andalucía o Informe del CEACCU (2008), el Código de Autorregulación de la Publicidad Infantil de Juguetes (2011 y 1993), el Código de Autorregulación de Contenidos Televisivos e Infancia y los acuerdos de la Comisión de Seguimiento de Publicidad Infantil (2003). En cuanto a las normas positivas: la Ley 7/2010, de 31 de marzo, General de Comunicación Audiovisual (LGCA), Ley 34/1988, de 11 de noviembre, General de Publicidad, de carácter general (LGP). A partir de este material se ha elaborado una ficha que recoge las variables principales: tipos de productos, género representado, mensajes-valores, voz en off, periodo, acciones representadas, interacción entre los personajes. Se aplicó un sistema de control sobre el 10% del total de los spot que fueron analizados por cada uno de los codificadores. Después se realizaron reuniones para analizar de forma conjunta los resultados con el fin de evitar discrepancias en la codificación (Kahlenberg & Hein, 2010).

3. Análisis y resultados

3.1. Tipos de juguetes

Los resultados demuestran que la mayoría de anuncios, el 77,5%, se agrupan, tan solo, en cinco grandes tipologías: 1) Muñecas y accesorios; 2) Figuras de acción; 3) Juegos de mesa; 4) Películas; 5) Vehículos a escala. La tipología de juguetes más anunciada en todos los períodos es muñecas y accesorios. Las tipologías de vehículos a escala y otras figuras descienden en el último periodo, mientras que la publicidad de figuras de acción, juegos de mesa y películas presentan significativos aumentos (véase tabla 1).

3.2. Representación de género

Los resultados confirman que existe una tendencia a la paridad en la representación de género, ya que en el último periodo analizado aumentó el porcentaje de anuncios con presencia de personajes de ambos sexos. Durante el período 2009-10 el género femenino (36,41%) fue superior al masculino (28,50%) y a la representación conjunta de ambos géneros (28,50%). En la campaña 2010-11 se igualan los porcentajes de anuncios con presencia del género femenino exclusivamente y los anuncios con presencia de ambos géneros (30,36%). En 2011-12 el porcentaje de anuncios con presencia de ambos géneros aumenta hasta el 40%, mientras que los anuncios con presencia de personajes de un solo género son inferiores a periodos anteriores. Resulta significativo el aumento desde 2009 (13,04 puntos) de los anuncios sin actores en el periodo 2010-11 (19,64%), muy similar a los datos de 2011-12 (18,75%), lo que se interpreta como una tendencia hacia la neutralidad en la presentación del juguete. El cruce de las variables Representación de género, Periodo y Tipos de juguete demuestra que el género femenino concentra su presencia en la tipología muñecas y accesorios. Esta presencia ha aumentado en cada periodo hasta alcanzar un 85,71%. La representación de ambos géneros se concentra en las tipologías juegos de mesa y muñecas y accesorios y su evolución también es positiva durante los tres periodos. Finalmente, el género masculino está presente principalmente en los anuncios de figuras de acción y vehículos a escala. Este dato refleja, además, un resultado notorio de esta investigación, ya que, en el último período analizado (2011-12), la presencia de personajes masculinos en los juguetes de muñecas se reduce a un 18,8% y siempre en compañía de personajes femeninos.

En este sentido, la representación publicitaria del género femenino en la publicidad española viene claramente asociada a los valores, significados y roles que la publicidad asocia a los personajes representados en esta tipología de juguetes, junto a juguetes animales e instrumentos musicales. La presencia de personajes femeninos, sin compañía de personajes masculinos, es inexistente en el resto de tipologías. Este hecho contrasta con la representación de personajes masculinos, ya que su presencia está repartida entre más tipologías, lo que puede suponer que los valores, significados y roles asociados a los personajes masculinos son más variados y numerosos.

3.3. Voz en off

El valor con mayor presencia es voz en off masculina en los tres periodos. En 2009-10 un 51,9% frente a un 46,7% femeninas. En 2010-11, un 49,11% frente a 42,85% femeninas. En 2011-12 un 56,25% frente a un 30% femeninas. La relación entre el género de la voz en off y el género de los personajes representados muestra una tendencia hacia el uso de voces de ambos géneros combinadas: 0% en 2009-10, 4,55% en 2010-11 y 15,79% en 2011-12. Igual ocurre en el género femenino, ya que, en 2011-12, en el 14,29% de las ocasiones con presencia de personajes solo femeninos se utilizó una voz en off combinada, mientras que antes no se hizo nunca. Destaca, especialmente, la desaparición de anuncios con voz en off masculina en anuncios con presencia exclusiva del género femenino. Si bien la voz en off adulta masculina es la más utilizada en los anuncios con personajes de ambos géneros, su uso ha descendido ligeramente en el último periodo a favor del aumento del uso de voces combinadas: un 1,85% en 2009-10 frente al 15,63% en 2011-12.

En relación a la tipología de juguetes, destacan los datos de vehículos a escala. Esta tipología utiliza la voz en off adulta masculina un 79,83% de media. El dato opuesto lo encontramos en la tipología muñecas y accesorios, con una media de 66,09% en el uso de la voz en off adulta femenina. Destaca la paridad en la utilización de la voz en off masculina y femenina en las tipologías juguetes de imitación del hogar, juguetes electrónicos, manualidades y juguetes animales.

3.4. Valores representados

Para analizar las variables Valores representados, Interacciones entre los personajes y Acciones representadas, los datos se han cruzado solo con las tipologías muñecas y accesorios, vehículos a escala y figuras de acción, por ser, éstas, las tipologías con mayor presencia según género. Los resultados contrastan con los supuestos planteados tras el análisis de la representación de género. Si bien se advertía que la variedad de valores y significados asociados al género masculino debiera ser mayor que la variedad de significados asociados al género femenino debido a que el género masculino está representado en más tipologías de juguetes que el género femenino, los datos demuestran que este supuesto no es certero, ya que cuantitativamente hay más variedad de significados asociados al género femenino que al masculino. El valor con mayor presencia en las tipologías muñecas y accesorios y vehículos a escala es la diversión (44,5% y 60,7%). En la tipología muñecas y accesorios los valores con mayor presencia, junto a diversión, son belleza, maternidad y amistad. Destaca la escasa presencia de los valores poder, fuerza, habilidad y desarrollo físico. Poder y fuerza es el valor con mayor presencia en la tipología figuras de acción, mientras que la competencia ocupa el segundo lugar y la amistad, la belleza y la eternidad no aparecen en esta tipología. En la tipología vehículos a escala, el valor diversión es el de mayor presencia, seguido de la competencia y el poder y fuerza. Similares datos encontramos en la tipología figuras de acción, ya que el valor de la amistad solo está presente en un 7,14% de los anuncios y la belleza y la maternidad tan solo en un 1,79%. Es común a las tres tipologías la baja presencia, inferior al 5%, de valores como el individualismo (1,2% en muñecas y accesorios, 0% en vehículos a escala y 3,9% en figuras de acción), la habilidad y el desarrollo físico (0,6%, 3,6% y 2% respectivamente) y la integración (5% en muñecas y accesorios y ausente en los otros dos tipos).

3.5. Acciones representadas

Las acciones más presentes en la tipología muñecas y accesorios son: afecto-nutritivas (35,8%), acciones domésticas y embellecimiento (28,4% en ambos casos). Estas acciones tienen una presencia muy baja o inexistente en los anuncios con mayor presencia de personajes masculinos. Las acciones más representadas en los anuncios de vehículos a escala y figuras de acción son: competitividad, demostraciones de fuerza y riesgo. En los juguetes del tipo vehículos a escala destacan la competitividad (32,1%) y el riesgo (30,4%), mientras que la fuerza tiene menor presencia (16,1%). Por su parte, la competitividad está presente en un 53% de los anuncios de figuras de acción, seguida de fuerza, que aparece en el 51% de los anuncios de estos juguetes. En tercer lugar se sitúan las acciones de riesgo, en un 35,3% de los casos. Las acciones de las profesiones representadas son inferiores al 10% en todas las tipologías de juguetes.

3.6. Interacción entre los personajes

Resalta el alto porcentaje de no interactividad entre los personajes en los anuncios. Este supuesto es el más frecuente en las tipologías figuras de acción (51%) y vehículos a escala (41,1%). En la tipología muñecas y accesorios, las interacciones más comunes son las amistosas (46,9%), seguidas de la no interacción entre personajes (27,1%). En figuras de acción las interacciones amistosas suponen solo un 9,80% de los casos estudiados, mientras que la enemistad y la lucha suponen un 15,69%. Esta interacción presenta un 5,36% en la tipología vehículos a escala y es nula en muñecas y accesorios. También destacan las interacciones materno-filiales (7,4%) en la tipología de muñecas y accesorios y su total ausencia en el resto de tipologías de juguetes. Las interacciones familiares están presentes en un 7,1% de los anuncios de vehículos a escala, un 6,2% en muñecas y accesorios, mientras que en figuras de acción es inexistente.

4. Discusión y conclusiones

En relación a la hipótesis 1, la representación de los géneros infantiles en la publicidad infantil según la tipología de juguete anunciada presenta notables diferencias. Aunque la paridad en la representación aumenta, ésta se aprecia, fundamentalmente, en las tipologías juguetes electrónicos, manualidades y animales. En la tipología de juguetes muñecas y accesorios predomina la representación del género femenino aunque aumenta la presencia masculina como secundaria. Por otra parte, en juguetes de construcciones, vehículos a escala y figuras de acción el género masculino es el más representado. Estos resultados están relacionados con los trabajos de Blackmore, LaRue y Olejnik (1979), el de Carter y Levy (1988), el de Martin, Eisenbud y Rose (1995), el de Campbell, Shriley, Heywood y Crook (1988) y el realizado por Serbin, Poulin-Dubois, Colburne, Sen y Eischted (2001), quienes concluyeron que la selección del juguete está determinada por el género y la edad. El género masculino infantil prefiere juguetes con capacidades y habilidades espaciales, mientras que las niñas eligen muñecas y juegos educativos.

Estas conclusiones coinciden incluso en los trabajos de género con primates, como demuestra la investigación de Alexander y Hines (2002). En relación a los resultados en otros estudios, Freeman (2007), Cugmas (2010) y Blackmore y Centers (2005), preocupados por la influencia de padres, educadores y sus roles en la selección de los juguetes por parte de los niños, esta investigación reafirma que la voz en off de los anuncios más utilizada es la masculina. Esto sugiere que la voz más legítima socialmente continúa siendo la masculina. En cualquier caso, existe una segmentación por género, dado que las voces femeninas predominan en los anuncios en los que aparecen niñas, las masculinas en las que aparecen niños, y las masculinas en los casos en los que aparecen ambos géneros representados. La presencia de adultos en los anuncios es casi nula; solo en los anuncios de juegos de mesa y en juguetes electrónicos está representando el rol de padre. Aunque los códigos de autorregulación y la ley positiva disponen respetar la paridad y evitar los contenidos sexistas para los menores en la publicidad infantil y la representación de ambos sexos tienda a la paridad, continúan las diferencias en las principales tipologías de juguetes.

En relación a la hipótesis 2, la publicidad infantil de juguetes utiliza valores y estereotipos diferentes según el género de los personajes representados y el tipo de juguete anunciando, tal y como apuntan las investigaciones de Jonhson y Young (2002) y Blackmore y Centers (2005). Existen valores asociados a ambos géneros y distribuidos con variedad entre las tipologías de juguetes, como: diversión, educación, solidaridad e individualismo. Sin embargo, es más frecuente la presencia de valores diferenciados claramente por género. Así, la belleza está vinculada a la tipología muñecas y accesorios, mientras que solo un 1,79% de los anuncios de vehículos de escala presentan este valor. Maternidad y seducción mantienen porcentajes de frecuencia similares asociados al género femenino. En relación al género masculino, la habilidad y el desarrollo físico aparecen asociados a los vehículos de escala y al género masculino en un 3,57% del total de los casos estudiados. Aunque su presencia es baja, en el 50% de las ocasiones en las que aparece este valor se asocia a esta tipología y a este género. La frecuencia del valor poder y fuerza es de 19,64% en vehículos a escala y de 72, 55% en la tipología figuras de acción, mientras que la tipología muñecas y accesorios se reduce al 0,62%. El valor competencia también ofrece claras diferencias en la representación por géneros, en el 93,75% de las ocasiones en las que aparece este valor se asocia a personajes masculinos. Su presencia es del 25% en las tipologías vehículos a escala y figuras de acción y residual en muñecas y accesorios, un 1,23%. Este trabajo concluye que la estética física, lo doméstico y la maternidad son tres valores con alta frecuencia en la representación del género femenino. Si bien la utilización de la maternidad puede justificarse mediante razones fisiológicas y de imitación hacia sus progenitores, la utilización de la belleza como valor asociado, casi exclusivamente, al género femenino puede promover un mensaje social que asocie belleza y mujer como realidad inseparable. Del mismo modo ocurre con la utilización del valor poder y fuerza en el caso del género masculino. Estos usos contribuyen a la formación de discursos sociales que promueven diferencias entre habilidades y cualidades asociadas a cada género. La publicidad infantil de juguetes fomenta mensajes del tipo: las niñas tienen que cuidar su belleza y los chicos su poder y fuerza. Esto se refuerza mediante el uso del tono exagerado en la voz en off, tal y como apuntaban los trabajos de Klinnder, Hamilton y Cantrell (2001), Jonhson y Young (2002) o Del Moral (1999). Esto demuestra que los anuncios forman parte de la representación social y de la diferenciación de género como apuntaban Belmonte y Guillamón (2008) e inciden sobre la responsabilidad y la función social de la publicidad en la configuración de la cultura.

El estudio de la representación del género es una constante en las investigaciones académicas y, desde una perspectiva funcionalista de los estudios de comunicación, la publicidad debe, también, ser entendida como un instrumento de educación social. Desde esta postura, comunicadores y educadores deben denunciar aquellas prácticas que fomenten la discriminación social por género. Si la publicidad responde a una transformación de la radiografía social de nuestra realidad en beneficio del anunciante gracias a los consumidores, ¿debe la publicidad beneficiar también a la sociedad e impulsar un cambio social hacia la igualdad de género? Si, como se recoge en los antecedentes de este trabajo, los juguetes son instrumentos fundamentales en el desarrollo social y cognitivo del niño, la legislación debe impulsar una representación de géneros más igualitaria y más variada en los anuncios de juguetes porque existen claras diferencias en la representación de género entre los juguetes dirigidos a niñas y los juguetes dirigidos a niños. Desde un punto de vista educativo, la publicidad de juguetes infantiles debiera fomentar su proyección desde una óptica más neutral centrada más en el producto y no solo en la estimulación simbólica mediante la representación/ identificación del consumidor. Ejemplo de ello sucedió las Navidades del 2012 en Suecia donde una conocida marca de juguetes apostó por la elaboración de un catálogo unisex en el que primaban los juguetes y no el género. Se mostraba a una niña disparando y a un niño acunando un bebé (Castillo, 2012). Quizá este sea un cambio que contribuya a una transformación social y sea, a un mismo tiempo, el reto que debe asumir la publicidad.

Referencias

Alexander, G. & Hines, M. (2002). Sex Differences in Response to Children´s Toys in Nonhuman Primates. Evolution an Human Behavior, 23, 469-479.

Almeida, D. (2009). Where Have All the Children Gone? A Visual Semiotic Account of Advertisements for Fashion Dolls. Visual Communication, 8, 4, 481-501.

Bakir, A. & Palan, K. (2010). How Are Children's Attitudes toward Ads and Brands Affected by Gender-related Content in Advertising? Journal of Advertising, 39, 35-48.

Bakir, A., Blodgett,, J. & Rose G. (2008). Children's Responses to Gender-role Stereo-typed Advertisements. Journal of Advertising Research, 48, 2, 255-266.

Belmonte, J. & Guillamón, S. (2008). Co-educar en la mirada contra los estereotipos de género en TV. Comunicar, 31, 115-120.

Blackmore, J., LaRue, A.A. & Olejnik, A.B. (1979). Sex-appropriate Toy Preference and the Ability to Conceptualize Toys as Sex-role Related. Development Psychology, 15, 339- 340.

Blakemore, J. & Centers, R. (2005). Characteristics of Boys´and Girls´toys. Sex Roles. 53, 619-633.

Bradbard, M. & Parkman, S.A. (1985). Gender Differences in Preschool Children Toy Request. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 145, 283-284.

Bradbard, M. (1985). Sex Differences in Adults´gifts and Childres´s Toy Request at Christmas. Psychological Reports, 56, 691-696.

Bringué, X. & De Los Ángeles, J. (2000). La investigación académica sobre la pu-blicidad, televisión y niños: antecedentes y estado de la cuestión. Comunicación y Sociedad, 13, 37-70.

Browne, B. (1998). Gender Stereotypes in Advertising on Children's Television in the 1990s: A Cross-national Analysis. Journal of Advertising, 27, 83-96.

Buijzen M. & Valkenburg, P. (2000). The Impact of Television Advertising on Chil-dren's Christmas Wishes. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 44, 3, 456-470.

Campbell, A., Shriley L. & al. (2000). Infants´ Visual Preference for Sex-congruent Ba-bies, Children, Toys and Activities: A Longitudinal Study. British Journal of Development Psychology, 18, 4, 479-498.

Carter, D. & Levy, G. (1988). Cognitive Aspects of Early Sex-role Development: The Influence of Gender Schemas on Preschoolers´memories and Preferences for Sex-typed Toys and Activities. Child Development, 59, 3, 782-792.

Castillo, M. (2012). Una campaña por el unisex. El País. (www.sociedad.elpais.com/-sociedad/2012/11/26/actualidad/1353935100_752317.html) (26-11-2012).

Chan K. & McNeal J. (2004). Children's Understanding of Television Advertising: A Revisit in the Chinese Context. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 165, 1, 28-36.

Cherney, D.I. & Dempsey, J. (2010). Young Children's Classification, Stereotyping and Play Behaviour for Gender Neutral and Ambiguous Toys. Educational Psychology, 30, 651-669.

Cherney, D.I. & London, K. (2006). Gender-linked Differences in the Toys, Television Shows, Computer Games, and Outdoor Activities of 5-to 13-year-old Children. Sex Roles, 54, 9-10, 717-726.

Cherney, D.I. (2005). Children´s and Adults Recall of Sex-stereotyped Toy Pictures: Effects of Presentation and Memory Task. Infant and Children Development, 4, 1, 11-27.

Consejo Audiovisual de Andalucía (Ed.) (2008). Estudio sobre la publicidad de juguetes campaña de navidad 2006-2007. Grupo de Trabajo de Infancia del Consejo Audiovisual de Andalucía (www.consejoaudiovisualdeandalucia.es ) (15-11-2009).

Cugmas, Z. (2010). Playing with Gender Stereotyped Toys. Didactica Slovenica-peda-goska Obzorja, 25, 130-146.

Del Moral, M.E. (1999). La publicidad indirecta de los dibujos animados y el consumo infantil de juguetes. Comunicar, 13, 220-224.

Erikson, E.H. (1995). Sociedad y adolescencia. México: Siglo XXI.

Espinar, E. (2007). Estereotipos de género en los contenidos audiovisuales infantiles. Comunicar, 29, 129-134.

Ferrer, M. (2007). Los anuncios de juguetes en la campaña de Navidad. Comunicar, 29, 135-142.

Francis, B. (2010). Gender, Toys and Learning. Oxford Review of Education, 36, 325-344.

Freeman, N.K. (2007). Preeschoolers´ Perceptions of Gender Appropriate Toys and their Parents´ Beliefs about Genderized Behaviors: Miscommunication, Mixed Messages, or Hidden Truths? Early Childhood Education Journal, 34, 5, 357-366.

Halford J., Boyland, E., Cooper, G. & al. (2008). Children's Food Preferences: Effects of Weight Status, Food Type, Branding and Television Food Advertisements (Commercials). International Journal of Pediatric Obesity, 3, 1, 31-38.

Huizinga, J. (2005). Homo ludens: El juego y la cultura, México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Jonhson, F.L. & Young, K. (2002). Gendered Voices in Children’s Television Ad-vertising. Critical Studies Media Communication, 19, 461-480.

Kahlenberg, S.G. & Hein, M.M. (2010). Progression on Nickelodeon? Gender-Role Stereotypes in Toy Commercials. Sex Roles, 62, 830-847.

Keller M. & Kalmus, V. (2009). Between Consumerism and Protectionism Attitudes towards Children, Consumption and the Media in Estonia Childhood. Global Journal of Child Research, 16, 3, 355-375.

Klinnder, L., Hamilton, J. & Cantrell, P. (2001). Children's Perceptions of Aggressive and Gender-specific content in toy commercials. Social Behavior and Personality, 29, 11-20.

Kunkel, D. (1992). Children Television Advertising in the Multichannel Environment. Journal of Communication, 42, 3, 265.

Liebert, R. (1986). Effects of Television on Children and Adolescents. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 7, 1, 43-48.

Martin, C.L., Eisenbud, L. & Rose, H. (1995). Children´s Gender-based Reasoning about Toys. Child Development, 66, 1457-1458.

Miller, C. (1987). Qualitative Differences among Gender-sterotyped Toys: Implications for Cognitive and Social Development in Girls and Boys. Sex Roles, 16, 473-487

Moreno, I. (2003). Narrativa audiovisual Publicitaria. Barcelona (España): Paidós.

Pérez-Ugena, A, (2008). Youth TV Programs in Europe and the U. S. Research Case Study Spanish Television. Doxa, 7, 43-58.

Pérez-Ugena, A., Martinez, E, & Perales, A. (2010). La regulación voluntaria en materia de publicidad: análisis y propuestas de mejora a partir del estudio del caso PAOS. Telos, 88, 130-141.

Pérez-Ugena, A., Martinez, E. & Salas, A. (2011a). Publicidad y juguetes: Análisis de los códigos deontológicos y jurídicos. Pensar la Publicidad, 4, 2, 127-140.

Pérez-Ugena, A., Martinez, E. & Salas, A. (2011b). Los estereotipos de género en la publicidad de los juguetes. Ámbitos, 20, 217-235.

Pestalozzi, J.H (1928). Cartas sobre la educación primaria dirigidas a J.P. Greaves. Madrid: La Lectura.

Pine, K. & Nash, A. (2003). Barbie or Betty? Preschool Children's Preference for Branded Products and Evidence for Gender-linked Differences. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 24, 4, 219-224.

Pine, K., Wilson, P. & Nash, A. (2007). The Relationship between Television Adver-tising, Children's Viewing and their Requests to Father Christmas. Journal of De-velopmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 28, 6, 456-461.

Robinson, T., Saphir M., Kraemer H. & al. (1981). Effects of Reducing Television Viewing on Children's Requests for Toys: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 22, 3, 179-184.

Ruble, D., Balaban, T. & Cooper, J. (1981). Gender Constancy and the Effects of Sex-typed Televised Toy Commercials. Child Development, 52, 2, 667-673.

Serbin, L.A., Poulin-Dubois, D., Colburne, K.A. & al. (2001). Gender Stereotyping in Infancy: Visual Preferences for and Knowledge of Gender-stereotyped Toys in the Second Year. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 25, 7-15.

Smith, L.J. (1994). A Content-analysis of Gender Differences in Children Advertising. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 38, 323-337.

Steuter, E. (1996). Out of the Garden: Toys and Children'sculture TV Advertising. Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, 33, 112-114.

The Cocktail analkysis, AIB, AEFJ (2012). El rol de Internet en la compra de juguetes.

Tur, V. & Luis Martínez, J. (2012). El color en spots infantiles: Prevalencia cromática y relación con el logotipo de marca. Comunicar, 38, 157-165.

Vygotski, L.S. (2003). La imaginación y el arte en la infancia. Madrid: Akal.

Ward, S., Walkman D.B. & Wartella, E. (1997). How Children Learnt to Buy. Beverly Hills (USA): Sage Publications.

Young, B.M. (1990) Television Advertising and Children. Oxford (Reino Unido): Oxford University Press.

Document information

Published on 31/05/13

Accepted on 31/05/13

Submitted on 31/05/13

Volume 21, Issue 1, 2013

DOI: 10.3916/C41-2013-18

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?