Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

Digital media are present in all areas of society, even configured as a new space for political socialization. This is especially applicable in the case of young people due to their high use of new technologies, as they are also trained with the necessary skills to do so. In this context, social networks have prompted the emergence of a new type of political participation: which takes place online. Therefore, this study delves into the relationship between the socialization that occurs in the network, digital skills and political participation online and offline. A quantitative survey-based methodology was used with university students from three Ibero-American countries: Mexico, Spain and Chile. The fieldwork was conducted between the months of December 2017 and June 2018. The results obtained show that young people consume mainly digital media, which does not prevent them from being critical with the quality they deserve. In this sense, the political participation actions in which they are involved are mostly developed in the network, thus participating to a lesser extent offline. Therefore, young people enter the world of politics through the consumption of information on the Internet, which favors a subsequent online political participation.

Resumen

Digital media are present in all areas of society, even configured as a new space for political socialization. This is especially applicable in the case of young people due to their high use of new technologies, as they are also trained with the necessary skills to do so. In this context, social networks have prompted the emergence of a new type of political participation: which takes place online. Therefore, this study delves into the relationship between the socialization that occurs in the network, digital skills and political participation online and offline. A quantitative survey-based methodology was used with university students from three Ibero-American countries: Mexico, Spain and Chile. The fieldwork was conducted between the months of December 2017 and June 2018. The results obtained show that young people consume mainly digital media, which does not prevent them from being critical with the quality they deserve. In this sense, the political participation actions in which they are involved are mostly developed in the network, thus participating to a lesser extent offline. Therefore, young people enter the world of politics through the consumption of information on the Internet, which favors a subsequent online political participation.

Resumen

Los medios digitales están presentes en todos los ámbitos de la sociedad, configurándose incluso como un nuevo espacio para la socialización política. Ello es especialmente aplicable en el caso de los jóvenes debido al elevado uso que realizan de las nuevas tecnologías, al estar capacitados también con las habilidades necesarias para ello. En este contexto, las redes sociales han propiciado el surgimiento de un nuevo tipo de participación política: la que tiene lugar de forma online. Por tanto, esta investigación indaga sobre la relación existente entre la socialización que se produce en la red, las habilidades digitales y la participación política en línea y fuera de línea. Se utiliza una metodología cuantitativa a partir de la realización de encuestas a jóvenes universitarios de México, España y Chile. El trabajo de campo se desarrolló entre los meses de diciembre de 2017 y junio de 2018. Los resultados obtenidos muestran que los jóvenes consumen principalmente medios digitales, lo cual no impide que sean críticos con la calidad que merecen los mismos. En relación con ello, las acciones de participación política en las que se implican se desarrollan en su mayoría en la red, participando así en menor medida fuera de línea. Por tanto, los jóvenes se introducen en el mundo de la política a través de Internet mediante el consumo de información, lo que favorece una posterior participación política online.

Keywords

Online learning, cyberactivism, survey, skills, young people, digital media, online civic engagement, socialization

Keywords

Aprendizaje en línea, ciberactivismo, encuesta, habilidades, jóvenes, medios digitales, participación online, socialización

Introduction

Digital media and political participation

In the last few years, beginning with the surge of social media, there is a new form of participation that takes place within cyberspace (Vesnic-Alujevic 2012). Political participation is understood as the set of actions and attitudes of citizens aimed at influencing the political system (Pasquino, 1996). In academia, the main topics of discussion in this respect are focused on the influence of traditional communication media on the discussion that occurs in social networks (Sveningsson, 2014; Gualda, Borrero, & Cañada 2015; Zaheer, 2016), as well as the capacity of social media to promote political participation, either online or offline (Bosetta, Dotceac, & Trenz, 2018). In this context, digital media are being configured as a new space for socialization (Resina, 2010), through which the individuals learn how to manage in this new online world (García-Peñalvo, 2016). Youth will be especially enveloped in this dynamic, as they are digital natives still in the process of shaping themselves.

In this respect, one of the most important learning activities in which youth are involved consists on learning how to be citizens. In agreement with this, digital media, as a new environment for political socialization, could contribute in the empowerment of youth to acquire the necessary abilities for participating in public life, as well as to develop new forms of activism (Hernández & al., 2013).

Therefore, new technologies are being shaped as the new stage for political participation. This could facilitate the implication of citizens in public life in a context of disaffection (Dalton, 2004), by contributing with overcoming the existing obstacles for offline participation (Grossman, 1995). In any case, this new form of political activism through the Internet would not substitute the traditional political participation offline, but it could be a complementary activity. As previous works have shown in the Mexican case, there is a strong relationship between both types of participation, online and offline (De-la-Garza & Barredo, 2017).

However, the concept of the internet as a facilitator of political activism has generated diverse objections from the academic field due to the existence of a digital divide which is based, in part, to the economic inequalities of access (Norris, 2001; DiMaggio & Hargittai 2001), and on the other hand, the inequality related to the digital skills needed for political participation online (Van-Dijk & Hacker, 2003; Hargittai 2002). In this scenario, age would condition access to new technologies, as well as the possession of digital skills needed for becoming politically involved through the internet (Albrecht 2006; Min 2010), as has been previously shown for the case of Spain (Recuero, 2016). In this sense, a prior interest in politics is required from the users in order to participate either online or offline (Casteltrione, 2016). Thus, many research studies mention that social networks such as Facebook re-enforce the civil commitment of politically-active users (Vromen, Loader, Xenos, & Bailo, 2016; Mascheroni, 2017), aside from favoring their move towards political action either online or offline (Min & Wohn, 2018).

Therefore, an interconnection would be produced between the three elements: socialization, digital skills and online/offline political participation. Thus, firstly, youth’s socialization in new technologies enables them to acquire new digital skills needed for utilizing the internet from every angle. These skills are the ones that subsequently facilitate the political socialization of youth, as they tend to introduce themselves into public life through new technologies. Therefore, young people can start to learn how to be citizens through the internet by politically participating online. This could favor the acquisition of new skills and competences that are political in character and that facilitate involvement in other types of offline participation. With the aim of recognizing how this phenomenon behaves in today’s youth, who began their process of socialization with these digital tools (Crovi, 2013), a comparative study was conducted between youth from the following Ibero-American countries: Mexico, Spain and Chile.

Youth in Mexico, Spain and Chile

In the last few years, youth have protagonized diverse activities of political participation that have been linked to their origin and/or their development with digital media. Experiences of this type can be identified in the three countries analyzed in the present research work. In Chile, the Chilean Student Winter was able to place the subject of public education in the political agenda (Aguilera, 2012; Zepeda, 2014), with the use of social media emerging as important. In this context, Vierner, Cárcamo and Scheihing (2018) posited that as the young Chileans showed an interest in politics, they had a greater tendency of adopting a critical posture against the massive communication media. Nevertheless, there was a high degree of political disaffection in Chile in young people (Mardones, 2014; Manríquez & Augusti, 2015).

As for Mexico, according to Morales (2002), youth’s mobilization has been fundamental for provoking institutional changes. With social movements after the emergence of #YoSoy132, a more participative citizenry has been strengthened with a clear commitment to diverse matters that concern this country (Portillo, 2015). It should be highlighted that the emergence of the active political participation in social media took place mainly after the birth of #YoSoy132 (Quiñónez, 2014). In the case of Spain, the new generations have more distrust towards the traditional media than social networks (Fernández, 2015).

One of the most important learning activities in which youth are involved consists on learning how to be citizens. In agreement with this, digital media, as a new environment for political socialization, could contribute in the empowerment of youth to acquire the necessary abilities for participating in public life, as well as to develop new forms of activism.

In agreement with this, Spanish youth have provided signs of their activism through the new technologies. In sometimes occasions, this online political participation has even been transferred to the traditional public space through offline political participation (García & al., 2014). The 15M movement and the Movement for Decent Housing are examples of this (Hernández & al., 2013; Haro & Sampedro 2011).

Material and methods

Objectives

The main objective of this study is to analyze the existing relationship between socialization on the Internet, the acquisition of digital skills and the political participations in both of its aspects, online and offline. In previous research, it has been shown that youth have a greater degree of activism online, as age is a variable that conditions online political participation (Norris, 2001; DiMaggio & Hargittai, 2001). Nevertheless, it is necessary to have a more in-depth understanding of the characteristics and constraints of this type of participation conducted by young people. In this respect, it has also been shown that the level of studies is a relevant variable (Albrecht, 2006; Recuero 2016), so that the combination of being young and having a high level of education would foster a greater digital activism. Therefore, the present study is focused on examining university students from Mexico, Spain and Chile, as they can fully participate politically, as legal adults. The analysis of this collective will allow us to verify whether digital media are shaped as a space for political participation in which youth learn how to become citizens.

Research design

In this study, a quantitative methodology is utilized starting with the design, application and analysis of a questionnaire given to young university students from Mexico, Spain and Chile. In the design of the questionnaire, two large sets of questions were formulated, which allowed for the comparison between countries.

In first place, we find those related with media consumption, which are aimed at identifying the digital socialization of youth, and which therefore mirror their related skills. In second place, we find the questions related to the political participation online as well as offline. In the formulation of the questions, the items proposed by previous research studies were taken into account. Thus, the reliability of the indicators utilized is guaranteed, as well as its comparability with other studies. Therefore, with respect to the consumption of media, the indicators proposed by Gómez and others (2013) in their study on political culture in the context of the presidential election in 2012 in Mexico, were taken into account.

With respect to the questions on online political participation, the items proposed by two research studies were included. Thus, a few of the elements utilized by Gil-de-Zúñiga and others (2010) were selected, such as the online signing of petitions about collective matters with which the students were in agreement. From the contribution by Vesnic-Alujevic (2012), the following activities were recovered: search for information on politics, read humorous content related to politics, watch a political video, share political information with others, participate or read discussions about politics, post information about politics in their profile, and post a “like” on a comment or a message from another user.

As for offline political participation, sometimes of the questions applied by Oser and others (2013) were included, such as contacting a politician about a public interest matter, contributing with an organization that seeks to influence public policies and others. Starting with the data collected with the use of the questionnaire, a descriptive analysis was conducted on the consumption of media as well as online and offline political participation of Mexican, Spanish and Chilean university students.

Sample

The size of the sample obtained in the study was composed of 1,239 interviews in the Mexican case, 627 interviews in the Spanish case, and 1,058 in the Chilean case. These interviews were given to Mexican, Spanish and Chilean students from public and private universities enrolled in different degrees. A non-probabilistic, convenience sampling was conducted, with the field work conducted between the second semester of 2017, and the first semester of 2018. The poll was applied through the Internet using the Google Forms platform. For the student’s participation in the poll, they were contacted by the professors from the universities that participated and collaborated in the study, so that access through the classroom is highlighted.

Results

Consumption and trust of conventional media

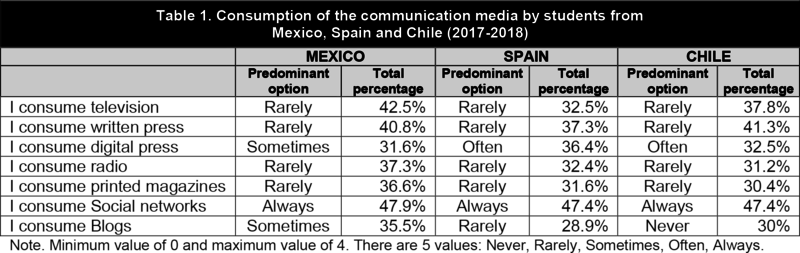

The results presented on Table 1 show the consumption of communication media for university students in Mexico, Spain and Chile. In this sense, the scarce exposure of this collective to audiovisual and written communication media was underlined. Thus, the type of media consumed least by Mexican youth was the television, as shown by most of those polled, with 42.5%, choosing the “rarely” option. In Spain and Chile, on their part, the printed press was the least consumed by university students, as most of them, 37.3% and 41.3%, respectively, indicated that they were exposed “rarely” to this medium. Following this, and with very similar results, we find the consumption of the printed press in the case of Mexican students (40.8%) and the consumption of television in the case of the Spanish and Mexican students (32.5% and 37.8%, respectively). Therefore, university youth from Mexico, Spain and Chile, have a scarce exposure to these types of media, with television and printed press reflecting the lowest consumption by all of them. Exposure to the other types of media is also reduced in the three countries examined, as shown by the numbers relative to the consumption of the radio and printed magazines.

In turn, the consumption of digital media was the greatest among the Mexican, Spanish and Chilean university students. In this respect, the high percentage of students in the three countries that confirmed utilizing social networks “always” was underlined, more specifically, 47.9% in Mexico, 47.4% in Spain, and 47.4% in Chile. The digital press, on its part, was consumed “often” by 36.4% of the Spanish and 32.5% of the Chileans, and “sometimes” by 31.6% of the Mexicans, a figure that is very close to those who declared being expose to it “often” (31.2%). As for the consumption of blogs, the behavior was less homogeneous. In this sense, it was notable that blogs were the digital media to which Ibero-American youth were least exposed to.

These data show how university students mainly and predominantly consume digital media, as compared to their scarce exposure to conventional media. Therefore, university youth share a pattern of behavior with respect to the consumption of media that is independent from the national context where they reside. This clearly shows that these young people are socializing through technological tools, so that they inform themselves about political matters through them.

|

|

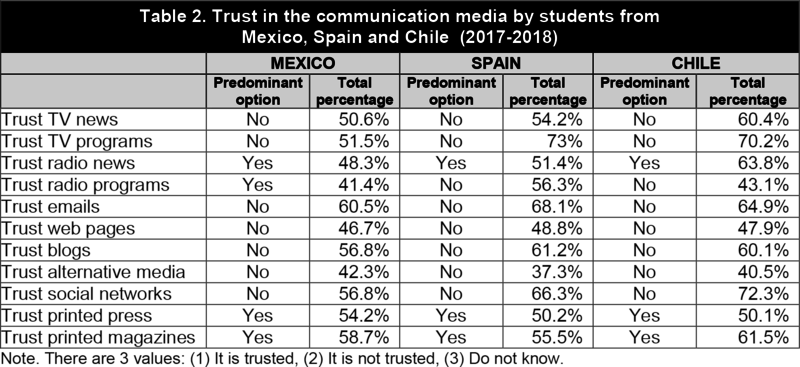

Nevertheless, the fact that these youths consume a type of media more than another does not imply that they are not able to discriminate their credibility. Related to this, Table 2 shows the results on the trust that the young Mexicans, Spanish and Chilean have on the communication media. It is noteworthy that the media that they trust the most are also the media that they least consume. Thus, most of the youth from Mexico, Spain and Chile only mentioned trusting the three conventional media. On the one hand, the printed magazines were trusted by 58.7% of the Mexican students, 55.5% of the Spanish students and 61.5% of the Chilean students, while on the other hand, and also predominantly, we find news from the radio, which generate credibility among 48.3% of Mexican youth, 51.4% of Spanish youth, and 63.8% of the Chilean youth. Lastly, 54.2% of those polled in Mexico, 50.2% in Spain, and 50.1% in Chile considered that the printed press also deserved credibility. Lastly, in the Mexican case, most of the students also trusted radio programs (41.4%).

The rest of the media, both conventional and digital, did not generate trust among the Ibero-American university students as a predominant option. As for the conventional media, the television programs generated the greatest consensus, as 51.5% of the Mexicans, 73% of the Spanish, and 70.2% of the Chileans did not trust them. The television news programs did not deserve credibility among most of the youth, with this option being predominant for 50.6% in Mexico, 54.2% in Spain, and 60.4% in Chile. As for the digital media, it is interesting to note that the students predominantly distrust them, despite their high consumption of this type of media. Thus, around six out of ten students did not trust email messages, social networks or blogs. In more detail, electronic mail did not generate trust among 60.5% of the Mexicans, 68.1% of the Spanish, and 64.9% of the Chileans.

|

|

In the case of the social networks, these numbers were 56.8%, 66.3% and 72.3%, respectively, with the results for blogs being 56.8%, 61.2% and 60.1%. Likewise, although the numbers were lower, the lack of trust on webpages were found to be 46.7% in Mexico, 48.8% in Spain, and 47.9% in Chile, with alternative media being 42.3% in Mexico, 37.3% in Spain and 40.5% in Chile. This information shows that the young, despite consuming digital media, are critical of the use they make of the new technologies. Thus, the fact that the young are socialized in the digital world enables them to have the ability to distinguish the quality of the medium they utilize.

Offline political participation

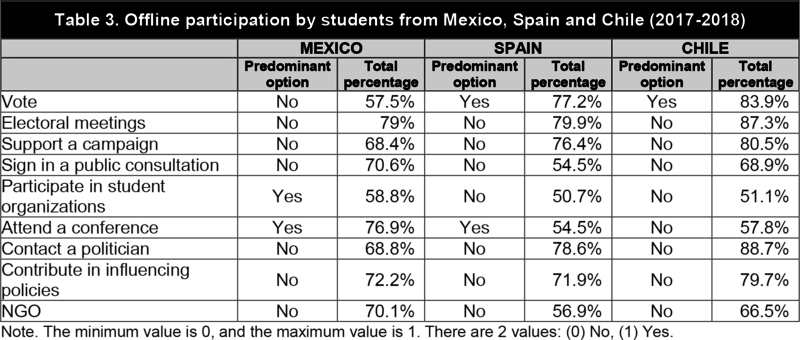

Table 3 shows the data on offline political participation by the young Ibero-American university students. In agreement with the results, this is mainly confined to the act of voting. Thus, most of those polled in Spain, 77.2%, and in Chile, 83.9%, confirmed being involved in the electoral political participation. Only Mexico was an exception to this pattern of behavior, as most of the young university students of the country, 57.5%, declared that they did not vote. In contrast, the Mexican students were greatly involved in other forms of offline political participation, such as attending a conference (76.9%) and participating in student organizations (58.8%). On the contrary, the Spanish and Chilean university students were not involved in other forms of participation, except for the former, with respect to attending a conference (54.5%).

The involvement of the youth on the remaining forms of offline activism was minor, especially in sometimes of them. Thus, more than seven out of ten polled attested to not participating in electoral meetings (79% in Mexico, 79.9% in Spain, and 87.3% in Chile), in contributing in influencing in public policies (72.2% in Mexico, 71.9% in Spain, and 79.7% in Chile), in contacting a politician (68.8% in Mexico, 78.6% in Spain, and 88.7% in Chile) and supporting a campaign (68.4% in Mexico, 76.4% in Spain, and 80.5% in Chile). These data show that the offline manners of participation mentioned were not an option for the youth for becoming involved politically. This modality can be favored by all of them and they are all related or promoted by the established political parties and the traditional political class. The participation in a NGO was also minor among the young university students in these countries, and it should be indicated that 70.1% of the Mexicans, 56.9% of the Spanish and 66.5% of the Chileans were not involved. Accordingly, most of the youth did not take part in the political participation activities offline, except for voting during elections. This implies the need to explore whether the political participation of university students is channeled through other venues, mainly through the Internet.

|

|

Online political participation

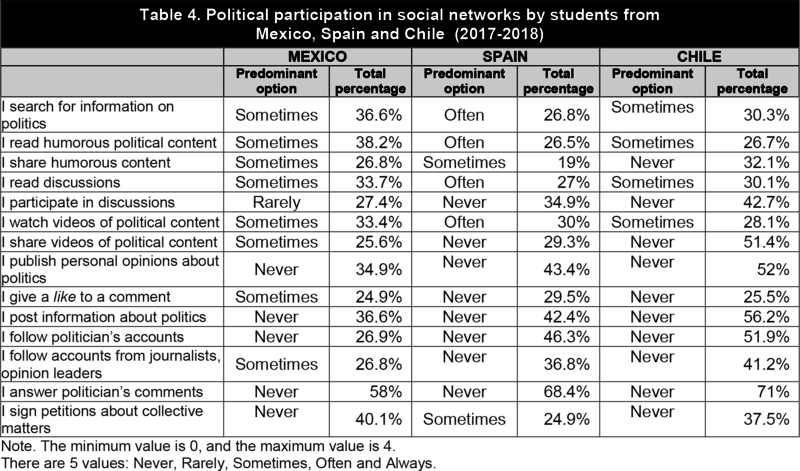

Table 4 shows the results related to online political participation. The existence of various forms of cyber activism that are conducted by most of the youth is notable. Thus, the most common acts of online participation conducted by Mexican, Spanish and Chilean university students were to search for information about politics, read humorous political content, read discussions on politics and watch political content.

Nevertheless, there are specificities between the different countries analyzed with respect to the diversity and intensity of the forms of online political participation conducted. In this sense, Mexicans were the ones who involved themselves to a greater degree in a great number of online participation activities, more specifically in nine of them. On the contrary, this participation did not reach a high intensity, as most of the students mentioned doing so “sometimes”. These forms of digital participation conducted “sometimes” by the Mexicans were: read humorous content about politics (38.2%), search for information about politics (36.6%), read discussions about politics (33.7%), watch videos of political content (33.4%), share humorous content about politics (26.8%), follow reporter’s and opinion leader’s accounts (26.8%), share a video of political content (25.6%), and give a “like” to a commentary about politics (24.9%). Likewise, 27.4% of the Mexicans participated in discussions about politics, although they did so “rarely”.

The Spanish on their part, became involved in a sometimeswhat smaller number of cyber activism activities, more specifically in six, although they did so with a greater intensity than the young Mexicans. Thus, most of the Spanish university students declared having participated “often” in watching videos of political content (30%), read discussion about politics (26.5%). Besides this, they affirmed having become involved “sometimes” in signing petitions about collective matters (24.9%) and in sharing humorous content about politics (19%). Lastly, the young Chileans were the ones that were the least involved in a smaller variety of online participation activities, more specifically, four. The intensity with which they participated in them was less than the Spanish university students, in line with what Mexican students do. Thus, most of the Chileans mentioned participating “sometimes” in searching information about politics (30.3%), read discussions about politics (30.1%), watch videos with political content (28.1%) and read humorous content about politics (26.7%).

The rest of the online participation activities were not conducted by most of the Ibero-American students. These forms of participation in which neither the Mexicans, Spanish nor Chileans were involved in, require a greater degree of activism. These are: publish personal opinions about politics, post information about politics, follow politician’s accounts and respond to politician’s comments. These results allow us to conclude that the young Mexican, Spanish and Chilean university students politically participate online to a greater degree than they do so offline. The forms of cyber activism they conducted had a passive component, as they are not related to the viewing or the reading of diverse types of content about politics. Nevertheless, the active search for political information is also a very commonly-conducted activity, which implies a more active role.

|

|

Discussion and conclusions

The new technologies have modified the habits of the citizens in all aspects of life. This new reality promotes the shaping of the digital media themselves into a new agent of socialization. In line with this, the political socialization that could be occurring at the heart of the internet takes on a special importance, especially with respect to the youth. In a time that the disaffection with the representation system pushes the citizens away from the traditional politics (Dalton, 2004), the new technologies could be shaping themselves as an alternative (Grossman, 1995). Due to this, it is of great interest to examine if the youth introduce themselves or not into politics through the Internet, and if this is the case, how this process is done and what the consequences are.

The aim of the present study was to investigate on the political socialization of the youth through the internet, the skills they have for this, and the political participation conducted online and offline. In this way, the intention was to verify if the youth initiated their contact with politics through the new technologies, hence previously requiring the necessary digital skills for this. Likewise, the aim of this contribution also aimed to observe if this online learning promoted or not the involvement of forms of online and offline participation. With this purpose, a poll was given to young university students from Mexico, Spain and Chile, reaching a sample size in each of the countries of 1,239, 627 and 1,058 students polled, respectively. The choice of the population studied is justified because the young university students are considered adults, which indicates that they can fully exercise their political rights, such as voting. The design of the poll was oriented towards obtaining information about two sets of questions. In first place, the consumption of media, as an indicator of political socialization, and on the trust placed on these media, as a reflection of the skills possessed by the youth. And in second place, on the political participation online as well as offline.

The results obtained show that the young Mexicans, Spanish and Chileans mainly consume digital communication media, so that they obtain political information through them. This is demonstrated by the social networks, followed by the digital press, being the sources to which they are most exposed to. Therefore, the youth introduced themselves to political matters through the new technologies, as it is through them that they know what is occurring in the political reality. This, together with their scarce exposure to the audiovisual and written communication media, confirms that the digital media play a political socialization role for these Ibero-American university students. Nevertheless, this political learning produced at the heart of the internet is not exempt of criticism by the youth. Thus, they are able to distinguish between credibility and trust that the media deserve, both conventional and digital. This especially important in the area of new technologies, in which the myriad of information available makes necessary being able to discriminate when facing the existence of numerous contents that are not reliable. In this sense, most of the university students from these countries do not trust the digital media they utilize, which implies that they count with an important ability to shape their own criteria, which is a necessity for performing as citizens. This civil socialization experienced by the youth in the internet seems to shape itself as a step prior to the learning of how to politically participate digitally. In this way, a significant part of the Spanish university students take part in activities of cyber activism. Nevertheless, the forms of online political participation they tend to conduct have a more passive character as they are related to reading or viewing of political content. In spite of this, they also take part in forms of participation that are more active, such a searching for political information.

As compared to the political activism that young Mexicans, Spanish and Chilean students partake in the digital networks, their decreased involvement is in offline political participation activities. Only the electoral participation, meaning voting, is predominant among the university students of the countries analyzed, except for Mexico. Nevertheless, and as already pointed out, both types of participation, online and offline, should not be considered completely different. In this sense, the consumption of political information on the internet by the youth, as well as the activities of activism they conduct online, can condition a posterior offline participation, such as voting. Nevertheless, it is necessary to continue to delve and broaden the analysis conducted in order to confirm the results obtained and to further delve into the learning about politics on the internet by the youth.

References

- AguileraO., . 2012.Repertorios y ciclos de movilización juvenil en Chile (2000-2012)Notas y Debates de la Actualidad 27(57):101-108

- AlbrechtS., . 2006.voice is heard in online deliberation? A study of participation and representation in political debates on the internet&author=Albrecht&publication_year= Whose voice is heard in online deliberation? A study of participation and representation in political debates on the internet.Information, Communication & Society 19(1):62-82

- BosettaM., DotceacA., TrenzH.J., . 2018.Political participation on Facebook during Brexit does user engagement on media pages stimulate engagement with campaigns?Journal of Language and Politics 17(2):173-194

- CasteltrioneI., . 2016.and political participation: Virtuous circle and participation intermediaries&author=Casteltrione&publication_year= Facebook and political participation: Virtuous circle and participation intermediaries.Interactions: Studies in Communication & Culture 7(2):177-196

- CroviD., . 2013.Jóvenes al fin, contraste de opiniones entre estudiantes y trabajadores. In: CroviD., GarayL.M., LópezR., PortilloM., eds. y apropiación tecnológica. La vida como hipertexto&author=Crovi&publication_year= Jóvenes y apropiación tecnológica. La vida como hipertexto. Distrito Federal: Sitesa/UNAM. 183-196

- DaltonR.J., . 2004.Democratic challenges, democratic choices. The erosion of political support in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- DarioDe-la-Garza,, DarioBarredo,, . 2017.Democracia digital en México: Un estudio sobre la participación de los jóvenes usuarios mexicanos durante las elecciones legislativas federales de 2015.Index Comunicación 7(1):95-114

- DiMaggioP., EHargittai, . 2001.From the ‘digital divide’ to ‘digital inequality’: Studying internet use as penetration increases. Working Paper nº 15. Center for Arts and Cultural Policy Studies, Woodrow Wilson School. Princeton: Princeton University.

- FernándezA., . 2015.que influyen en la confianza en los medios: explorando la asociación entre el consumo de medios y las noticias sobre el Movimiento 15M&author=Fernández&publication_year= Factores que influyen en la confianza en los medios: explorando la asociación entre el consumo de medios y las noticias sobre el Movimiento 15M.Hipertext 13:1-16

- GarcíaM.C., MercedesD.H., FernándezC., . 2014.comprometidos en la Red: El papel de las redes sociales en la participación social activa. [Engaged youth in Internet. The role of social networks in social active participation&author=García&publication_year= Jóvenes comprometidos en la Red: El papel de las redes sociales en la participación social activa. [Engaged youth in Internet. The role of social networks in social active participation]]Comunicar 43:35-43

- García-PeñalvoF.J., . 2016.socialización como proceso clave en la gestión del conocimiento&author=García-Peñalvo&publication_year= La socialización como proceso clave en la gestión del conocimiento.Education in the Knowledge Society 17(2):7-14

- H.Gil-de-Zúñiga,, A.Veenstra,, E.Vraga,, D.Shah,, . 2010.democracy: Reimagining pathways to political participation&author=H.&publication_year= Digital democracy: Reimagining pathways to political participation.Journal of Information Technology & Politics 7(1):36-51

- GómezS., TejeraH., AguilarJ., . 2013. , ed. cultura política de los jóvenes en México&author=&publication_year= La cultura política de los jóvenes en México. México: Colegio de México.

- GrossmanL.K., . 1995.The electronic republic: Reshaping democracy in the information age. New York: Viking.

- GualdaE., BorreroJ.D., CañadaJ.C., . 2015.‘Spanish Revolution’ en Twitter (2): Redes de hashtags y actores individuales y colectivos respecto a los desahucios en España&author=Gualda&publication_year= La ‘Spanish Revolution’ en Twitter (2): Redes de hashtags y actores individuales y colectivos respecto a los desahucios en España.Redes 26(1):1-22

- HargittaiE., . 2002.digital divide: Differences in people’s online skills&author=Hargittai&publication_year= Second-level digital divide: Differences in people’s online skills.First Monday 7(4):1-20

- HaroC., SampedroV., . 2011.Activismo político en Red: Del movimiento por la vivienda digna al 15M.Teknokultura 8(2):167-185

- E.Hernández,, M.C.Robles,, J.B.Martínez,, .interactivos y culturas cívicas: sentido educativo, mediático y político del 15M. [Interactive youth and civic cultures: The educational, mediatic and political meaning of the 15M&author=E.&publication_year= Jóvenes interactivos y culturas cívicas: sentido educativo, mediático y político del 15M. [Interactive youth and civic cultures: The educational, mediatic and political meaning of the 15M]]Comunicar 40:59-67

- ManríquezM.T., AugustiE.C., . 2015.Participación multi-asociativa de los jóvenes y espacio público: Evidencias desde el caso chileno.Revista Del CLAD Reforma y Democracia 62:167-192

- MardonesR., . 2014.encrucijada de la democracia chilena: una aproximación conceptual a la desafección política&author=Mardones&publication_year= La encrucijada de la democracia chilena: una aproximación conceptual a la desafección política.Papel Político 19(1):39-59

- MascheroniG., . 2017.A practice-based approach to online participation: Young people’s participatory habitus as a source of diverse online engagement.International Journal of Communication 11:4630-4651

- MinS.J., . 2010.the digital divide to the democratic divide: Internet skills, political interest, and the second-level digital divide in political internet use&author=Min&publication_year= From the digital divide to the democratic divide: Internet skills, political interest, and the second-level digital divide in political internet use.Journal of Information Technology & Politics 7(1):22-35

- MinS.J., WohnD., . 2018.the news that you don't like: Cross-cutting exposure and political participation in the age of social media&author=Min&publication_year= All the news that you don't like: Cross-cutting exposure and political participation in the age of social media.Computers in Human Behavior 83:24-31

- MoralesH., . 2002.de la movilización juvenil en México. Notas para su análisis&author=Morales&publication_year= Visibilidad de la movilización juvenil en México. Notas para su análisis.Última 17:11-39

- NorrisP., . 2001.Digital divide: Civil engagement, information poverty, and the internet worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- OserJ., HoogheM., MarienS., . 2013.online participation distinct from offline participation? A latent class analysis of participation types and their stratification&author=Oser&publication_year= Is online participation distinct from offline participation? A latent class analysis of participation types and their stratification.Political Research Quarterly 66(1):91-101

- PasquinoG., BartoliniS., CottaM., . 1996.de Ciencia Política&author=Pasquino&publication_year= Manual de Ciencia Política. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

- PortilloM., . 2015.Construcción de ciudadanía a partir del relato de jóvenes participantes del# YoSoy132.Global Media Journal México 12:1-18

- QuiñónezL.C., . 2014.y elecciones 2012: viejos y nuevos desafíos para la comunicación política en México&author=Quiñónez&publication_year= Medios y elecciones 2012: viejos y nuevos desafíos para la comunicación política en México.Nóesis 23(45):24-48

- RecueroF., . 2016. , ed. participación política online: Un análisis de sus condicionantes. Actas del XV Congreso Nacional de Educación Comparada: Ciudadanía mundial y educación para el desarrollo. Una mirada internacional&author=&publication_year= La participación política online: Un análisis de sus condicionantes. Actas del XV Congreso Nacional de Educación Comparada: Ciudadanía mundial y educación para el desarrollo. Una mirada internacional. Sevilla: Universidad Pablo de Olavide.

- ResinaJ., . 2010.Ciberpolítica, redes sociales y nuevas movilizaciones en España: El impacto digital en los procesos de deliberación y participación ciudadana.Mediaciones Sociales 7(2):143-164

- SveningssonM., . 2014.don’t like it and I think it’s useless, people discussing politics on Facebook´: Young Swedes’ understandings of social media use for political discussion&author=Sveningsson&publication_year= `I don’t like it and I think it’s useless, people discussing politics on Facebook´: Young Swedes’ understandings of social media use for political discussion.Cyberpsychology 8(3):1-16

- Van-DijkJ., HackerK., . 2003.digital divide as a complex and dynamic phenomenon&author=Van-Dijk&publication_year= The digital divide as a complex and dynamic phenomenon.The International Society 19(4):315-326

- Vesnic-AlujevicL., . 2012.participation and Web 2.0 in Europe: A case study of Facebook&author=Vesnic-Alujevic&publication_year= Political participation and Web 2.0 in Europe: A case study of Facebook.Public Relations Review 38(3):466-470

- ViernerM., CárcamoL., ScheihingE., . 2018.crítico de los jóvenes ciudadanos frente a las noticias en Chile. [Critical thinking of young citizens towards news headlines in Chile&author=Vierner&publication_year= Pensamiento crítico de los jóvenes ciudadanos frente a las noticias en Chile. [Critical thinking of young citizens towards news headlines in Chile]]Comunicar 54:101-110

- VromenA., LoaderB., XenosM., BailoF., . 2016.making through Facebook engagement: Young citizens’ political interactions in Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States&author=Vromen&publication_year= Everyday making through Facebook engagement: Young citizens’ political interactions in Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States.Political Studies 64(3):513-533

- ZaheerL., . 2016.Use of social media and political participation among university students.Pakistan Vision 17(1):295

- ZepedaR., . 2014.El movimiento estudiantil chileno: desde las calles al congreso nacional.RASE 7(3):689-695

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Los medios digitales están presentes en todos los ámbitos de la sociedad, configurándose incluso como un nuevo espacio para la socialización política. Ello es especialmente aplicable en el caso de los jóvenes debido al elevado uso que realizan de las nuevas tecnologías, al estar capacitados también con las habilidades necesarias para ello. En este contexto, las redes sociales han propiciado el surgimiento de un nuevo tipo de participación política: la que tiene lugar de forma online. Por tanto, esta investigación indaga sobre la relación existente entre la socialización que se produce en la red, las habilidades digitales y la participación política en línea y fuera de línea. Se utiliza una metodología cuantitativa a partir de la realización de encuestas a jóvenes universitarios de México, España y Chile. El trabajo de campo se desarrolló entre los meses de diciembre de 2017 y junio de 2018. Los resultados obtenidos muestran que los jóvenes consumen principalmente medios digitales, lo cual no impide que sean críticos con la calidad que merecen los mismos. En relación con ello, las acciones de participación política en las que se implican se desarrollan en su mayoría en la red, participando así en menor medida fuera de línea. Por tanto, los jóvenes se introducen en el mundo de la política a través de Internet mediante el consumo de información, lo que favorece una posterior participación política online.

Resumen

Digital media are present in all areas of society, even configured as a new space for political socialization. This is especially applicable in the case of young people due to their high use of new technologies, as they are also trained with the necessary skills to do so. In this context, social networks have prompted the emergence of a new type of political participation: which takes place online. Therefore, this study delves into the relationship between the socialization that occurs in the network, digital skills and political participation online and offline. A quantitative survey-based methodology was used with university students from three Ibero-American countries: Mexico, Spain and Chile. The fieldwork was conducted between the months of December 2017 and June 2018. The results obtained show that young people consume mainly digital media, which does not prevent them from being critical with the quality they deserve. In this sense, the political participation actions in which they are involved are mostly developed in the network, thus participating to a lesser extent offline. Therefore, young people enter the world of politics through the consumption of information on the Internet, which favors a subsequent online political participation.

Resumen

Los medios digitales están presentes en todos los ámbitos de la sociedad, configurándose incluso como un nuevo espacio para la socialización política. Ello es especialmente aplicable en el caso de los jóvenes debido al elevado uso que realizan de las nuevas tecnologías, al estar capacitados también con las habilidades necesarias para ello. En este contexto, las redes sociales han propiciado el surgimiento de un nuevo tipo de participación política: la que tiene lugar de forma online. Por tanto, esta investigación indaga sobre la relación existente entre la socialización que se produce en la red, las habilidades digitales y la participación política en línea y fuera de línea. Se utiliza una metodología cuantitativa a partir de la realización de encuestas a jóvenes universitarios de México, España y Chile. El trabajo de campo se desarrolló entre los meses de diciembre de 2017 y junio de 2018. Los resultados obtenidos muestran que los jóvenes consumen principalmente medios digitales, lo cual no impide que sean críticos con la calidad que merecen los mismos. En relación con ello, las acciones de participación política en las que se implican se desarrollan en su mayoría en la red, participando así en menor medida fuera de línea. Por tanto, los jóvenes se introducen en el mundo de la política a través de Internet mediante el consumo de información, lo que favorece una posterior participación política online.

Keywords

Online learning, cyberactivism, survey, skills, young people, digital media, online civic engagement, socialization

Keywords

Aprendizaje en línea, ciberactivismo, encuesta, habilidades, jóvenes, medios digitales, participación online, socialización

Introduction

Digital media and political participation

In the last few years, beginning with the surge of social media, there is a new form of participation that takes place within cyberspace (Vesnic-Alujevic 2012). Political participation is understood as the set of actions and attitudes of citizens aimed at influencing the political system (Pasquino, 1996). In academia, the main topics of discussion in this respect are focused on the influence of traditional communication media on the discussion that occurs in social networks (Sveningsson, 2014; Gualda, Borrero, & Cañada 2015; Zaheer, 2016), as well as the capacity of social media to promote political participation, either online or offline (Bosetta, Dotceac, & Trenz, 2018). In this context, digital media are being configured as a new space for socialization (Resina, 2010), through which the individuals learn how to manage in this new online world (García-Peñalvo, 2016). Youth will be especially enveloped in this dynamic, as they are digital natives still in the process of shaping themselves.

In this respect, one of the most important learning activities in which youth are involved consists on learning how to be citizens. In agreement with this, digital media, as a new environment for political socialization, could contribute in the empowerment of youth to acquire the necessary abilities for participating in public life, as well as to develop new forms of activism (Hernández & al., 2013).

Therefore, new technologies are being shaped as the new stage for political participation. This could facilitate the implication of citizens in public life in a context of disaffection (Dalton, 2004), by contributing with overcoming the existing obstacles for offline participation (Grossman, 1995). In any case, this new form of political activism through the Internet would not substitute the traditional political participation offline, but it could be a complementary activity. As previous works have shown in the Mexican case, there is a strong relationship between both types of participation, online and offline (De-la-Garza & Barredo, 2017).

However, the concept of the internet as a facilitator of political activism has generated diverse objections from the academic field due to the existence of a digital divide which is based, in part, to the economic inequalities of access (Norris, 2001; DiMaggio & Hargittai 2001), and on the other hand, the inequality related to the digital skills needed for political participation online (Van-Dijk & Hacker, 2003; Hargittai 2002). In this scenario, age would condition access to new technologies, as well as the possession of digital skills needed for becoming politically involved through the internet (Albrecht 2006; Min 2010), as has been previously shown for the case of Spain (Recuero, 2016). In this sense, a prior interest in politics is required from the users in order to participate either online or offline (Casteltrione, 2016). Thus, many research studies mention that social networks such as Facebook re-enforce the civil commitment of politically-active users (Vromen, Loader, Xenos, & Bailo, 2016; Mascheroni, 2017), aside from favoring their move towards political action either online or offline (Min & Wohn, 2018).

Therefore, an interconnection would be produced between the three elements: socialization, digital skills and online/offline political participation. Thus, firstly, youth’s socialization in new technologies enables them to acquire new digital skills needed for utilizing the internet from every angle. These skills are the ones that subsequently facilitate the political socialization of youth, as they tend to introduce themselves into public life through new technologies. Therefore, young people can start to learn how to be citizens through the internet by politically participating online. This could favor the acquisition of new skills and competences that are political in character and that facilitate involvement in other types of offline participation. With the aim of recognizing how this phenomenon behaves in today’s youth, who began their process of socialization with these digital tools (Crovi, 2013), a comparative study was conducted between youth from the following Ibero-American countries: Mexico, Spain and Chile.

Youth in Mexico, Spain and Chile

In the last few years, youth have protagonized diverse activities of political participation that have been linked to their origin and/or their development with digital media. Experiences of this type can be identified in the three countries analyzed in the present research work. In Chile, the Chilean Student Winter was able to place the subject of public education in the political agenda (Aguilera, 2012; Zepeda, 2014), with the use of social media emerging as important. In this context, Vierner, Cárcamo and Scheihing (2018) posited that as the young Chileans showed an interest in politics, they had a greater tendency of adopting a critical posture against the massive communication media. Nevertheless, there was a high degree of political disaffection in Chile in young people (Mardones, 2014; Manríquez & Augusti, 2015).

As for Mexico, according to Morales (2002), youth’s mobilization has been fundamental for provoking institutional changes. With social movements after the emergence of #YoSoy132, a more participative citizenry has been strengthened with a clear commitment to diverse matters that concern this country (Portillo, 2015). It should be highlighted that the emergence of the active political participation in social media took place mainly after the birth of #YoSoy132 (Quiñónez, 2014). In the case of Spain, the new generations have more distrust towards the traditional media than social networks (Fernández, 2015).

One of the most important learning activities in which youth are involved consists on learning how to be citizens. In agreement with this, digital media, as a new environment for political socialization, could contribute in the empowerment of youth to acquire the necessary abilities for participating in public life, as well as to develop new forms of activism.

In agreement with this, Spanish youth have provided signs of their activism through the new technologies. In sometimes occasions, this online political participation has even been transferred to the traditional public space through offline political participation (García & al., 2014). The 15M movement and the Movement for Decent Housing are examples of this (Hernández & al., 2013; Haro & Sampedro 2011).

Material and methods

Objectives

The main objective of this study is to analyze the existing relationship between socialization on the Internet, the acquisition of digital skills and the political participations in both of its aspects, online and offline. In previous research, it has been shown that youth have a greater degree of activism online, as age is a variable that conditions online political participation (Norris, 2001; DiMaggio & Hargittai, 2001). Nevertheless, it is necessary to have a more in-depth understanding of the characteristics and constraints of this type of participation conducted by young people. In this respect, it has also been shown that the level of studies is a relevant variable (Albrecht, 2006; Recuero 2016), so that the combination of being young and having a high level of education would foster a greater digital activism. Therefore, the present study is focused on examining university students from Mexico, Spain and Chile, as they can fully participate politically, as legal adults. The analysis of this collective will allow us to verify whether digital media are shaped as a space for political participation in which youth learn how to become citizens.

Research design

In this study, a quantitative methodology is utilized starting with the design, application and analysis of a questionnaire given to young university students from Mexico, Spain and Chile. In the design of the questionnaire, two large sets of questions were formulated, which allowed for the comparison between countries.

In first place, we find those related with media consumption, which are aimed at identifying the digital socialization of youth, and which therefore mirror their related skills. In second place, we find the questions related to the political participation online as well as offline. In the formulation of the questions, the items proposed by previous research studies were taken into account. Thus, the reliability of the indicators utilized is guaranteed, as well as its comparability with other studies. Therefore, with respect to the consumption of media, the indicators proposed by Gómez and others (2013) in their study on political culture in the context of the presidential election in 2012 in Mexico, were taken into account.

With respect to the questions on online political participation, the items proposed by two research studies were included. Thus, a few of the elements utilized by Gil-de-Zúñiga and others (2010) were selected, such as the online signing of petitions about collective matters with which the students were in agreement. From the contribution by Vesnic-Alujevic (2012), the following activities were recovered: search for information on politics, read humorous content related to politics, watch a political video, share political information with others, participate or read discussions about politics, post information about politics in their profile, and post a “like” on a comment or a message from another user.

As for offline political participation, sometimes of the questions applied by Oser and others (2013) were included, such as contacting a politician about a public interest matter, contributing with an organization that seeks to influence public policies and others. Starting with the data collected with the use of the questionnaire, a descriptive analysis was conducted on the consumption of media as well as online and offline political participation of Mexican, Spanish and Chilean university students.

Sample

The size of the sample obtained in the study was composed of 1,239 interviews in the Mexican case, 627 interviews in the Spanish case, and 1,058 in the Chilean case. These interviews were given to Mexican, Spanish and Chilean students from public and private universities enrolled in different degrees. A non-probabilistic, convenience sampling was conducted, with the field work conducted between the second semester of 2017, and the first semester of 2018. The poll was applied through the Internet using the Google Forms platform. For the student’s participation in the poll, they were contacted by the professors from the universities that participated and collaborated in the study, so that access through the classroom is highlighted.

Results

Consumption and trust of conventional media

The results presented on Table 1 show the consumption of communication media for university students in Mexico, Spain and Chile. In this sense, the scarce exposure of this collective to audiovisual and written communication media was underlined. Thus, the type of media consumed least by Mexican youth was the television, as shown by most of those polled, with 42.5%, choosing the “rarely” option. In Spain and Chile, on their part, the printed press was the least consumed by university students, as most of them, 37.3% and 41.3%, respectively, indicated that they were exposed “rarely” to this medium. Following this, and with very similar results, we find the consumption of the printed press in the case of Mexican students (40.8%) and the consumption of television in the case of the Spanish and Mexican students (32.5% and 37.8%, respectively). Therefore, university youth from Mexico, Spain and Chile, have a scarce exposure to these types of media, with television and printed press reflecting the lowest consumption by all of them. Exposure to the other types of media is also reduced in the three countries examined, as shown by the numbers relative to the consumption of the radio and printed magazines.

In turn, the consumption of digital media was the greatest among the Mexican, Spanish and Chilean university students. In this respect, the high percentage of students in the three countries that confirmed utilizing social networks “always” was underlined, more specifically, 47.9% in Mexico, 47.4% in Spain, and 47.4% in Chile. The digital press, on its part, was consumed “often” by 36.4% of the Spanish and 32.5% of the Chileans, and “sometimes” by 31.6% of the Mexicans, a figure that is very close to those who declared being expose to it “often” (31.2%). As for the consumption of blogs, the behavior was less homogeneous. In this sense, it was notable that blogs were the digital media to which Ibero-American youth were least exposed to.

These data show how university students mainly and predominantly consume digital media, as compared to their scarce exposure to conventional media. Therefore, university youth share a pattern of behavior with respect to the consumption of media that is independent from the national context where they reside. This clearly shows that these young people are socializing through technological tools, so that they inform themselves about political matters through them.

|

|

Nevertheless, the fact that these youths consume a type of media more than another does not imply that they are not able to discriminate their credibility. Related to this, Table 2 shows the results on the trust that the young Mexicans, Spanish and Chilean have on the communication media. It is noteworthy that the media that they trust the most are also the media that they least consume. Thus, most of the youth from Mexico, Spain and Chile only mentioned trusting the three conventional media. On the one hand, the printed magazines were trusted by 58.7% of the Mexican students, 55.5% of the Spanish students and 61.5% of the Chilean students, while on the other hand, and also predominantly, we find news from the radio, which generate credibility among 48.3% of Mexican youth, 51.4% of Spanish youth, and 63.8% of the Chilean youth. Lastly, 54.2% of those polled in Mexico, 50.2% in Spain, and 50.1% in Chile considered that the printed press also deserved credibility. Lastly, in the Mexican case, most of the students also trusted radio programs (41.4%).

The rest of the media, both conventional and digital, did not generate trust among the Ibero-American university students as a predominant option. As for the conventional media, the television programs generated the greatest consensus, as 51.5% of the Mexicans, 73% of the Spanish, and 70.2% of the Chileans did not trust them. The television news programs did not deserve credibility among most of the youth, with this option being predominant for 50.6% in Mexico, 54.2% in Spain, and 60.4% in Chile. As for the digital media, it is interesting to note that the students predominantly distrust them, despite their high consumption of this type of media. Thus, around six out of ten students did not trust email messages, social networks or blogs. In more detail, electronic mail did not generate trust among 60.5% of the Mexicans, 68.1% of the Spanish, and 64.9% of the Chileans.

|

|

In the case of the social networks, these numbers were 56.8%, 66.3% and 72.3%, respectively, with the results for blogs being 56.8%, 61.2% and 60.1%. Likewise, although the numbers were lower, the lack of trust on webpages were found to be 46.7% in Mexico, 48.8% in Spain, and 47.9% in Chile, with alternative media being 42.3% in Mexico, 37.3% in Spain and 40.5% in Chile. This information shows that the young, despite consuming digital media, are critical of the use they make of the new technologies. Thus, the fact that the young are socialized in the digital world enables them to have the ability to distinguish the quality of the medium they utilize.

Offline political participation

Table 3 shows the data on offline political participation by the young Ibero-American university students. In agreement with the results, this is mainly confined to the act of voting. Thus, most of those polled in Spain, 77.2%, and in Chile, 83.9%, confirmed being involved in the electoral political participation. Only Mexico was an exception to this pattern of behavior, as most of the young university students of the country, 57.5%, declared that they did not vote. In contrast, the Mexican students were greatly involved in other forms of offline political participation, such as attending a conference (76.9%) and participating in student organizations (58.8%). On the contrary, the Spanish and Chilean university students were not involved in other forms of participation, except for the former, with respect to attending a conference (54.5%).

The involvement of the youth on the remaining forms of offline activism was minor, especially in sometimes of them. Thus, more than seven out of ten polled attested to not participating in electoral meetings (79% in Mexico, 79.9% in Spain, and 87.3% in Chile), in contributing in influencing in public policies (72.2% in Mexico, 71.9% in Spain, and 79.7% in Chile), in contacting a politician (68.8% in Mexico, 78.6% in Spain, and 88.7% in Chile) and supporting a campaign (68.4% in Mexico, 76.4% in Spain, and 80.5% in Chile). These data show that the offline manners of participation mentioned were not an option for the youth for becoming involved politically. This modality can be favored by all of them and they are all related or promoted by the established political parties and the traditional political class. The participation in a NGO was also minor among the young university students in these countries, and it should be indicated that 70.1% of the Mexicans, 56.9% of the Spanish and 66.5% of the Chileans were not involved. Accordingly, most of the youth did not take part in the political participation activities offline, except for voting during elections. This implies the need to explore whether the political participation of university students is channeled through other venues, mainly through the Internet.

|

|

Online political participation

Table 4 shows the results related to online political participation. The existence of various forms of cyber activism that are conducted by most of the youth is notable. Thus, the most common acts of online participation conducted by Mexican, Spanish and Chilean university students were to search for information about politics, read humorous political content, read discussions on politics and watch political content.

Nevertheless, there are specificities between the different countries analyzed with respect to the diversity and intensity of the forms of online political participation conducted. In this sense, Mexicans were the ones who involved themselves to a greater degree in a great number of online participation activities, more specifically in nine of them. On the contrary, this participation did not reach a high intensity, as most of the students mentioned doing so “sometimes”. These forms of digital participation conducted “sometimes” by the Mexicans were: read humorous content about politics (38.2%), search for information about politics (36.6%), read discussions about politics (33.7%), watch videos of political content (33.4%), share humorous content about politics (26.8%), follow reporter’s and opinion leader’s accounts (26.8%), share a video of political content (25.6%), and give a “like” to a commentary about politics (24.9%). Likewise, 27.4% of the Mexicans participated in discussions about politics, although they did so “rarely”.

The Spanish on their part, became involved in a sometimeswhat smaller number of cyber activism activities, more specifically in six, although they did so with a greater intensity than the young Mexicans. Thus, most of the Spanish university students declared having participated “often” in watching videos of political content (30%), read discussion about politics (26.5%). Besides this, they affirmed having become involved “sometimes” in signing petitions about collective matters (24.9%) and in sharing humorous content about politics (19%). Lastly, the young Chileans were the ones that were the least involved in a smaller variety of online participation activities, more specifically, four. The intensity with which they participated in them was less than the Spanish university students, in line with what Mexican students do. Thus, most of the Chileans mentioned participating “sometimes” in searching information about politics (30.3%), read discussions about politics (30.1%), watch videos with political content (28.1%) and read humorous content about politics (26.7%).

The rest of the online participation activities were not conducted by most of the Ibero-American students. These forms of participation in which neither the Mexicans, Spanish nor Chileans were involved in, require a greater degree of activism. These are: publish personal opinions about politics, post information about politics, follow politician’s accounts and respond to politician’s comments. These results allow us to conclude that the young Mexican, Spanish and Chilean university students politically participate online to a greater degree than they do so offline. The forms of cyber activism they conducted had a passive component, as they are not related to the viewing or the reading of diverse types of content about politics. Nevertheless, the active search for political information is also a very commonly-conducted activity, which implies a more active role.

|

|

Discussion and conclusions

The new technologies have modified the habits of the citizens in all aspects of life. This new reality promotes the shaping of the digital media themselves into a new agent of socialization. In line with this, the political socialization that could be occurring at the heart of the internet takes on a special importance, especially with respect to the youth. In a time that the disaffection with the representation system pushes the citizens away from the traditional politics (Dalton, 2004), the new technologies could be shaping themselves as an alternative (Grossman, 1995). Due to this, it is of great interest to examine if the youth introduce themselves or not into politics through the Internet, and if this is the case, how this process is done and what the consequences are.

The aim of the present study was to investigate on the political socialization of the youth through the internet, the skills they have for this, and the political participation conducted online and offline. In this way, the intention was to verify if the youth initiated their contact with politics through the new technologies, hence previously requiring the necessary digital skills for this. Likewise, the aim of this contribution also aimed to observe if this online learning promoted or not the involvement of forms of online and offline participation. With this purpose, a poll was given to young university students from Mexico, Spain and Chile, reaching a sample size in each of the countries of 1,239, 627 and 1,058 students polled, respectively. The choice of the population studied is justified because the young university students are considered adults, which indicates that they can fully exercise their political rights, such as voting. The design of the poll was oriented towards obtaining information about two sets of questions. In first place, the consumption of media, as an indicator of political socialization, and on the trust placed on these media, as a reflection of the skills possessed by the youth. And in second place, on the political participation online as well as offline.

The results obtained show that the young Mexicans, Spanish and Chileans mainly consume digital communication media, so that they obtain political information through them. This is demonstrated by the social networks, followed by the digital press, being the sources to which they are most exposed to. Therefore, the youth introduced themselves to political matters through the new technologies, as it is through them that they know what is occurring in the political reality. This, together with their scarce exposure to the audiovisual and written communication media, confirms that the digital media play a political socialization role for these Ibero-American university students. Nevertheless, this political learning produced at the heart of the internet is not exempt of criticism by the youth. Thus, they are able to distinguish between credibility and trust that the media deserve, both conventional and digital. This especially important in the area of new technologies, in which the myriad of information available makes necessary being able to discriminate when facing the existence of numerous contents that are not reliable. In this sense, most of the university students from these countries do not trust the digital media they utilize, which implies that they count with an important ability to shape their own criteria, which is a necessity for performing as citizens. This civil socialization experienced by the youth in the internet seems to shape itself as a step prior to the learning of how to politically participate digitally. In this way, a significant part of the Spanish university students take part in activities of cyber activism. Nevertheless, the forms of online political participation they tend to conduct have a more passive character as they are related to reading or viewing of political content. In spite of this, they also take part in forms of participation that are more active, such a searching for political information.

As compared to the political activism that young Mexicans, Spanish and Chilean students partake in the digital networks, their decreased involvement is in offline political participation activities. Only the electoral participation, meaning voting, is predominant among the university students of the countries analyzed, except for Mexico. Nevertheless, and as already pointed out, both types of participation, online and offline, should not be considered completely different. In this sense, the consumption of political information on the internet by the youth, as well as the activities of activism they conduct online, can condition a posterior offline participation, such as voting. Nevertheless, it is necessary to continue to delve and broaden the analysis conducted in order to confirm the results obtained and to further delve into the learning about politics on the internet by the youth.

References

- AguileraO., . 2012.Repertorios y ciclos de movilización juvenil en Chile (2000-2012)Notas y Debates de la Actualidad 27(57):101-108

- AlbrechtS., . 2006.voice is heard in online deliberation? A study of participation and representation in political debates on the internet&author=Albrecht&publication_year= Whose voice is heard in online deliberation? A study of participation and representation in political debates on the internet.Information, Communication & Society 19(1):62-82

- BosettaM., DotceacA., TrenzH.J., . 2018.Political participation on Facebook during Brexit does user engagement on media pages stimulate engagement with campaigns?Journal of Language and Politics 17(2):173-194

- CasteltrioneI., . 2016.and political participation: Virtuous circle and participation intermediaries&author=Casteltrione&publication_year= Facebook and political participation: Virtuous circle and participation intermediaries.Interactions: Studies in Communication & Culture 7(2):177-196

- CroviD., . 2013.Jóvenes al fin, contraste de opiniones entre estudiantes y trabajadores. In: CroviD., GarayL.M., LópezR., PortilloM., eds. y apropiación tecnológica. La vida como hipertexto&author=Crovi&publication_year= Jóvenes y apropiación tecnológica. La vida como hipertexto. Distrito Federal: Sitesa/UNAM. 183-196

- DaltonR.J., . 2004.Democratic challenges, democratic choices. The erosion of political support in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- DarioDe-la-Garza,, DarioBarredo,, . 2017.Democracia digital en México: Un estudio sobre la participación de los jóvenes usuarios mexicanos durante las elecciones legislativas federales de 2015.Index Comunicación 7(1):95-114

- DiMaggioP., EHargittai, . 2001.From the ‘digital divide’ to ‘digital inequality’: Studying internet use as penetration increases. Working Paper nº 15. Center for Arts and Cultural Policy Studies, Woodrow Wilson School. Princeton: Princeton University.

- FernándezA., . 2015.que influyen en la confianza en los medios: explorando la asociación entre el consumo de medios y las noticias sobre el Movimiento 15M&author=Fernández&publication_year= Factores que influyen en la confianza en los medios: explorando la asociación entre el consumo de medios y las noticias sobre el Movimiento 15M.Hipertext 13:1-16

- GarcíaM.C., MercedesD.H., FernándezC., . 2014.comprometidos en la Red: El papel de las redes sociales en la participación social activa. [Engaged youth in Internet. The role of social networks in social active participation&author=García&publication_year= Jóvenes comprometidos en la Red: El papel de las redes sociales en la participación social activa. [Engaged youth in Internet. The role of social networks in social active participation]]Comunicar 43:35-43

- García-PeñalvoF.J., . 2016.socialización como proceso clave en la gestión del conocimiento&author=García-Peñalvo&publication_year= La socialización como proceso clave en la gestión del conocimiento.Education in the Knowledge Society 17(2):7-14

- H.Gil-de-Zúñiga,, A.Veenstra,, E.Vraga,, D.Shah,, . 2010.democracy: Reimagining pathways to political participation&author=H.&publication_year= Digital democracy: Reimagining pathways to political participation.Journal of Information Technology & Politics 7(1):36-51

- GómezS., TejeraH., AguilarJ., . 2013. , ed. cultura política de los jóvenes en México&author=&publication_year= La cultura política de los jóvenes en México. México: Colegio de México.

- GrossmanL.K., . 1995.The electronic republic: Reshaping democracy in the information age. New York: Viking.

- GualdaE., BorreroJ.D., CañadaJ.C., . 2015.‘Spanish Revolution’ en Twitter (2): Redes de hashtags y actores individuales y colectivos respecto a los desahucios en España&author=Gualda&publication_year= La ‘Spanish Revolution’ en Twitter (2): Redes de hashtags y actores individuales y colectivos respecto a los desahucios en España.Redes 26(1):1-22

- HargittaiE., . 2002.digital divide: Differences in people’s online skills&author=Hargittai&publication_year= Second-level digital divide: Differences in people’s online skills.First Monday 7(4):1-20

- HaroC., SampedroV., . 2011.Activismo político en Red: Del movimiento por la vivienda digna al 15M.Teknokultura 8(2):167-185

- E.Hernández,, M.C.Robles,, J.B.Martínez,, .interactivos y culturas cívicas: sentido educativo, mediático y político del 15M. [Interactive youth and civic cultures: The educational, mediatic and political meaning of the 15M&author=E.&publication_year= Jóvenes interactivos y culturas cívicas: sentido educativo, mediático y político del 15M. [Interactive youth and civic cultures: The educational, mediatic and political meaning of the 15M]]Comunicar 40:59-67

- ManríquezM.T., AugustiE.C., . 2015.Participación multi-asociativa de los jóvenes y espacio público: Evidencias desde el caso chileno.Revista Del CLAD Reforma y Democracia 62:167-192

- MardonesR., . 2014.encrucijada de la democracia chilena: una aproximación conceptual a la desafección política&author=Mardones&publication_year= La encrucijada de la democracia chilena: una aproximación conceptual a la desafección política.Papel Político 19(1):39-59

- MascheroniG., . 2017.A practice-based approach to online participation: Young people’s participatory habitus as a source of diverse online engagement.International Journal of Communication 11:4630-4651

- MinS.J., . 2010.the digital divide to the democratic divide: Internet skills, political interest, and the second-level digital divide in political internet use&author=Min&publication_year= From the digital divide to the democratic divide: Internet skills, political interest, and the second-level digital divide in political internet use.Journal of Information Technology & Politics 7(1):22-35

- MinS.J., WohnD., . 2018.the news that you don't like: Cross-cutting exposure and political participation in the age of social media&author=Min&publication_year= All the news that you don't like: Cross-cutting exposure and political participation in the age of social media.Computers in Human Behavior 83:24-31

- MoralesH., . 2002.de la movilización juvenil en México. Notas para su análisis&author=Morales&publication_year= Visibilidad de la movilización juvenil en México. Notas para su análisis.Última 17:11-39

- NorrisP., . 2001.Digital divide: Civil engagement, information poverty, and the internet worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- OserJ., HoogheM., MarienS., . 2013.online participation distinct from offline participation? A latent class analysis of participation types and their stratification&author=Oser&publication_year= Is online participation distinct from offline participation? A latent class analysis of participation types and their stratification.Political Research Quarterly 66(1):91-101

- PasquinoG., BartoliniS., CottaM., . 1996.de Ciencia Política&author=Pasquino&publication_year= Manual de Ciencia Política. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

- PortilloM., . 2015.Construcción de ciudadanía a partir del relato de jóvenes participantes del# YoSoy132.Global Media Journal México 12:1-18