(Created page with "<span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_es"></span>Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)</span> ==== Abstract ==== This...") |

m (Scipediacontent moved page Draft Content 444139225 to Briones Lara 2016a) |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 18:34, 27 March 2019

Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

This paper presents the results of an international collaboration on ethics teaching for personal and professional values within the area of formal higher education using new communication technologies. The course design was based on the dialogic technique and was aimed at clarifying the students’ own values, defining their own positions related to ethical dilemmas, developing argumentative strategies and an ethical commitment to their profession and contribution to society. The online dialogue between heterogeneous groups of students based on their cultural background –the main innovation of this training– was possible thanks to the technological and administrative support of the participating universities. To analyze the effect of this innovative training we employed a quasi-experimental design using a control group, i.e., without the option of online dialogue with students from another culture. University students from Spain (University of Cantabria) and Chile (Universidad Autónoma de Chile) participated in this study. The positive results, which included better scores and positive assessments of both debate involvement and intercultural contact by students who participated in the new teaching program, support the main conclusion that the opening of international dialogue on moral dilemmas through new communication technologies contributes significantly to improve ethics training in higher education.

1. Introduction

The contribution of higher education institutions for the training of professionals with strong ethical convictions is a subject of special interest. It is fundamental that higher education institutions, besides focusing on professional preparation, should also consider the development of personal skills such as critical thinking (Nussbaum 2005). In this sense, the Global Declaration on Higher Education (UNESCO, 2009: 2) has recognized that present society lives in a deep crisis of values, and therefore, «higher education must not only give solid skills for the present and future world but must also contribute to the education of ethical citizens committed to the construction of peace, the defence of human rights and the values of democracy». Ultimately, ethical education becomes a necessity, and the University has been identified as one of the entities responsible for this education, in European as well as American contexts (Escámez, García-López, & Jover, 2008; Esteban & Buxarrais, 2004; Jover, López, & Quiroga, 2011; Muhr, 2010; Petrova, 2010).

This teaching of ethics in university classrooms is especially necessary in the case of future professionals in the fields of Psychology and Education, as their professional work is, to a great extent, a pillar on which the development of the rest of the members of society rests. However, this training, as shown by Bolívar (2005), becomes a «null curriculum» of the university degrees, in the sense that it is part of the curriculum by omission when the necessary dimensions are not explicitly included for its future application in professional practice. Guerrero and Gómez (2013) have confirmed the absence of teaching of ethics and morality to the students in the Latin American region. Especially in the degrees of Psychology and Education, the great importance that the students and professional schools have given to professional ethics in their education has been noted, at the same time that they have mentioned the scarce or non-attention given to this in their university training (Bolívar, 2005; Río, 2009). The results regarding the Teaching degree students were especially interesting (Bolívar, 2005), as it evidenced the generalized absence of the moral character of the teacher’s education and the professional teacher’s ethics, as the focus is more centred on providing the teachers with contents and technical skills than with a critical social conscience. As for Psychology, and specifically in the Chilean environment, research by Alvear, Pasmanik, Winkler and Olivares (2008), shows that these professionals have a preference for using their own personal judgement before taking into consideration deontological ethics when making decisions that are ethical in character. With this in mind, Pasmanik and Winkler (2009) argue that this tendency is probably due to the ethical training received during the university years, characterized by being scarce, theoretical and decontextualized, neglecting reflection and debate.

It is also relevant to point out that the didactic developments that truly specify how to deal with the teaching of values in the classroom are scarce (Molina, Silva, & Cabezas, 2005; Rodríguez, 2012). Most of the literature available is focused on reflections about the need to teach values in higher education, or analyzes the perspectives of different agents that are involved in it (Buxarrais, Esteban, & Mellen, 2015; Escámez & al., 2008; García, Sales, Moliner, & Ferrández, 2009; Jiménez, 1997). Even fewer in number are the publications that discuss the joint participation of universities from different countries, using the possibilities that new communication technologies have opened for this, although these have been exploited for the learning of other content, with positive results (Zhu, 2012) and have therefore confirmed that discussions online can be a powerful tool for the development of critical thinking (Guiller, Durndell, & Ross, 2008).

By taking into account what was discussed above, we developed a proposal for the teaching of ethics in higher formal education through the development of a dialogic methodology and the use of new communication technologies that allow for contact between students from different cultures and degree programmes. The final aim of this training was to teach the university students to rationally and autonomously construct their values so that they may develop their own well-reasoned ethical principles. This will not only allow them to position themselves with arguments in face of society’s demands, but will optimize their professional performance. The quasi-experimental, international and applied character of this contribution, which centres on the teaching of ethics at university, is a key piece that can push forward the purpose of higher education.

1.1. Innovating in ethics education

The training designed for this research creates an active methodology that is based on dialogic techniques that intend for the students to clarify their values and use them to take a stand on a subject, avoiding indoctrination in the resolution of moral conflicts. The basis of this dialogic methodology lies in the cognitive theory of moral development by Kohlberg (1981) and other theoretical developments that bring together feelings and cognition (Benhabib, 2011), and that defend a moral education that helps individuals to «confront the other viewpoint without losing the possibility to accessing or appealing to universal horizons of values» (Gozálvez & Jover, 2016: 311). Therefore, the need to facilitate a framework and a procedure so that values can be experienced, constructed and lived, is raised. The dialogic technique is an appropriate active methodology, as values are inserted into the dialogue (as it requires judgement by the other) and at the same time, through listening, reflection and reasoning, these same values are approached. Also, the students, through reflection and the clash of opinions on conflictive situations that are of personal and professional interest, re-structure their reasoning, thereby enhancing their moral development (López, Carpintero, Del-Campo, Lázaro, & Soriano, 2010; Meza, 2008).

The training designed herein also tries to bolster reasoning strategies, as the psychological processes of argumentation are especially linked to ethics, and the mastery of the reasoning process has great importance for family, social, political and academic life. Yepes, Rodríguez y Montoya (2006) have described reasoning as the use of words to produce discourses in which a position is taken in a reasoned-with manner when confronting a topic or a problem. They have also argued that it is part of the thought process that involves the laws of reasoning (logic), the rules of approval and refusal (dialectics), and the use of verbal resources with the aim of persuading with reference to feelings, emotions and suggestions (rhetoric). The characteristics of the argument are linked to learning about values, as the argument implies the opposite of accepting obtuse, fanatical positions that cling to a single point of view.

On the other hand, the procedure designed highlights the special care that is given to the preparation of the debate, its management, and the creation of collaborative groups. Good dialogue requires that the participants freely express what they think, feel and believe, and many can show resistance when facing this risk (Barckley, Cross, & Howell, 2007). The participation of the students in a rewarding dialogue implies a challenge in contexts that are characterized by the fomenting of a passive attitude, which is characteristic of old models of higher education. Therefore, it is important to make efforts to achieve an adequate management of the classroom that guarantees an environment of trust that can stimulate the participation of all the students in the debate. The procedure selected to reach this objective was the progressive panel debate technique. As Villafaña (2008) has pointed, it allows for the delving into the study of a topic, following through and optimizing ideas or conclusions; it weighs the contributions of all the participants, and brings together the members of a group around a common topic.

At this point it is also convenient to point out that the role of the teacher in the managing of the dialogic technique in the classroom and online is essential. Therefore, taking into account the studies by Cantillo and others (2005), Meza (2008), and Bender (2012), we stress the inclusion of specific processes and resources at each stage. It is essential that the instructions make clear that the objective of the activity is to individually and jointly think and reason about possible moral solutions. For this, the dialogue and proposed questions and objections will be employed. In the debate, it is important that the teacher puts questions that guide the discussion, starting with exploratory questions that confirm that the dilemma has been understood. It is also important that the students define their stand on a topic, make clear their thinking structure and have the opportunity to recognize that behind the same opinion, there could be very different reasons. Progress is made in the debate by increasing its complexity and stimulating a higher level of moral reasoning by, for example, bringing in new information, with questions about events that happened in its context, and according to universal consequences. Also, in the online dialogues, it is important to explicitly clarify what is expected from the discussion (i.e. as related to the frequency and quality of the participation) and explain the style of the interventions online, as the debate is not typical of formal work (Bender, 2012).

1.2. International collaboration for the teaching of ethics in international higher education

The teaching of the ethics procedure presented in this research work was applied at the Autonomous University of Chile and the University of Cantabria (Spain). The participating students were enrolled in class subjects that coincided with the teaching of skills such as socio-moral reflection, critical comprehension of reality, dialogue and argumentation, perspective-taking and an attitude of respect and tolerance towards other opinions, as well as the meta-knowledge of their own self and existence. The coincidence in the curriculum allowed for the joint creation of this teaching program, which would be further enhanced by the strength that cultural diversity provides in bolstering critical thinking (Loes, Pascarella, & Umbach, 2012). Shared learning about ethics, then, sought to optimize the dialogic tool (through the debate on ethical dilemmas), guaranteeing diversity in the online group debate of the students thanks to the internationalization and support of the Information and Communication Technologies (ICT).

The Spanish students were enrolled in the course named Teaching values and personal competencies for teachers, which was part of the coursework found in the Teacher Training for Early Childhood Education and Primary Education degrees. The general objectives of this course included the development of strategies for their socio-emotional and ethical development, promoting the teachers’ well-being and coexistence in the educational community, as well as reflection on their or others’ way of being.

The Chilean participants were enrolled in the Personal Development IV course of the Psychology degree, whose main objectives were the development of the psychologist’s role and his/her commitment to professional ethics. In this course, the students applied the personal and interpersonal skills knowledge acquired to group contexts in the educational environment. As this was their first professional practice of the degree, it was fundamental that they were conscious of the need for ethical preparation for the exercising of their profession.

2. Methods

2.1. Research design and participants

In this study, 226 university students participated in two groups. In the training group, 147 students participated, 69 from the Autonomous University of Chile (UA) and 78 from the University of Cantabria (UC). In the control group (they received ethics training without the option of online dialogue), 79 students from the UC participated.

The data on the academic results were analysed from the entire sample. The analysis of the evaluation of the training, on the other hand, was performed only on the 46 students who gave their opinion (13 from the training group in the UC and 24 from the UA, and 9 from the control group) as this was anonymous and voluntary.

2.2. Procedure

The following key stages in this innovative training in values were considered:

a) The creation of «twinned groups» –culturally heterogeneous- and the ICT. A collaboration agreement was established between the two universities to guarantee the protection of data and the confidentiality of the students, as well as to achieve the opening of the Moodle platform and the ICT, created by the Spanish university for this purpose, to the Chilean students.

In the classrooms of each participating university, groups of four or five members were created, and these were twinned to a similarly-sized group from the other university. In the virtual platform Moodle, a wiki per twinned group was created, so that they could confidentially share, create and edit diverse types of content related to their approaches, as well as to talk and dialogue among themselves.

b) Design of the materials shared: bibliography, lectures, exercises, dilemma, and evaluation rubric. All the students had the same materials and bibliography available, and the professors employed the same presentations for their lectures. Also, a formative and summative evaluation was designed that contributed to the training of the students.

c) Implementation of the sessions and activities: The training was developed over a period of four weeks. The sequence of the sessions were carried out simultaneously in both universities and planned as shown below:

The first session (2 hours) started with a lecture on values and their importance for personal development and coexistence. It continued with training in consistent value clarification exercises to first identify the student’s own values. Then, the identification of values and counter-values was performed using interactive processes found in ethical dilemmas. For the teaching of argumentative skills, identification activities of different types were performed, and the dialogic argumentative structure was practiced on controversial subjects of the student’s own choosing (adapted from Yepes & al., 2006). This session culminated with the presentation of the ethical dilemma, which consisted on the trailer for the film «Into the wild», accompanied by a script in which the students are urged, through questioning, to identify and reason the values and counter-values present, and to reflect on their positions on it. This situation was chosen as a type of moral dilemma, with the object of involving the students not only rationally, but also emotionally. These types of situations, which are close to the personal (private) environment, are considered to be the most accurate to work with when dealing with dilemmas (Meza, 2008).

In the second week (1 hour) the application of the progressive panel debate technique started. The students worked in small groups in the classroom, so that they expressed their thoughts individually; then, they debated and created a report that contained the viewpoints heard in the group. It was only in the training group where the students were urged to share this report with the twinned group through the Moodle wiki; in addition they were asked to dialogue online outside of the classroom for a week.

In the third session (1 hour) a great assembly took place in the classroom. The students developed their individual viewpoints post-debate, outside the classroom.

In the last week, the professors gathered the student’s individual viewpoint reports that were created pre- and post-debate, to evaluate them according to the evaluation rubric. Additionally, through an online poll, the training was evaluated using the students’ perception of the training they received.

2.3. Instruments of evaluation2.3.1. Evaluation rubric of the academic results

The evaluation rubric was composed of the following criteria, which were grouped into three sections that had a relative weight on the final mark (shown between parentheses).

a) In the individual pre-debate approaches, the degree in which the values and counter-values were identified was evaluated, as well as the quality of the argument used on their initial stance (25% in the training group and 50% in the control).

b) Regarding the participation in the online debate, the fact that the students published the report created in the small groups on the debate in the Moodle wiki, the quality of said reports and the comments from the twinned group in the wiki were taken into account (35% in the training group).

c) In the post-debate viewpoints, we took into account the addition of values and counter-values by students. We also looked at the extent to which the final viewpoints were developed, drawing from new arguments and/or delving into those that had been already present, starting with or identifying the stances that were shown in the debates (40% in the training group and 50% in the control).

2.3.2. Assessment of their own participation

The students evaluated their participation in the debates using two items: one on their participation in the class debates, and another about their online participation. This last was not applicable to the control group, as it did not include online debates. The scale of the response oscillated between 1 (nothing) and 10 (much). The items were: «How much did you participate in the debate created in the classroom? How much have you participated in the debate developed in the wiki?»

Also, the perceived quality of the participation was measured using seven items (a=.77, N=46) taken from Cantillo & al. (2005: 69). The st*udents answered by using a frequency scale where 1 indicated «never»; 2, «sometimes» and 3, «always». Some examples of these items are: «When I want to participate, I ask to have the word» and «I do not attack personally».

2.3.3. Evaluation of the training

Lastly, four open-ended questions were also asked, so that the students reflected on and gave information about the meta-knowledge they had acquired (i.e. what did you learn?), their preferences (i.e. what did you like best? And the least?), and also provided some suggestions to improve the methodology and the procedures in the future versions (i.e. what suggestions could you give to improve and innovate this training?).

3. Results

3.1. Academic results

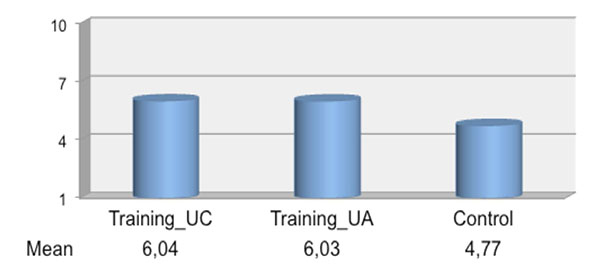

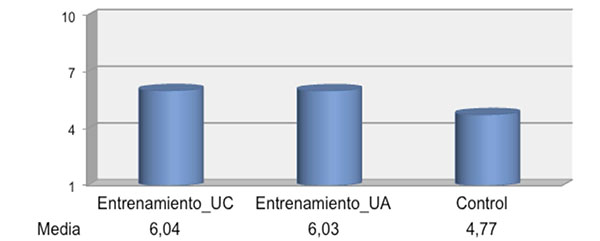

As we observe in figure 1, the students in the training group obtained better results as compared to those in the control group.

Figure 1. Average of the marks obtained in each of the groups (maximum score = 10).

The Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric analysis applied due to the lack of homogeneity of variances (Levene test: F (2,223)=3.65, p<.05) confirmed that the differences in the marks obtained were significant (?2(2)=22.76, p<.001). Pair-wise comparison of the training and control groups with the Mann-Whitney U test resulted in differences only when comparing the control group with the other two training groups. Therefore, the Chilean students (U=1657.5, p< .001) and the Spanish students in the training group (U=1927, p<.001) had better marks than the students in the control group.

3.2. Participation on the debates

First, the differences on the assessment of the participation on the debates performed in the classroom are presented. Non-parametric tests were performed, given that the assumptions of normality of the scores were not met, either for the participation in the classroom (Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S)=0.154, p<.01) or the participation online (K-S=0.167, p<.01).

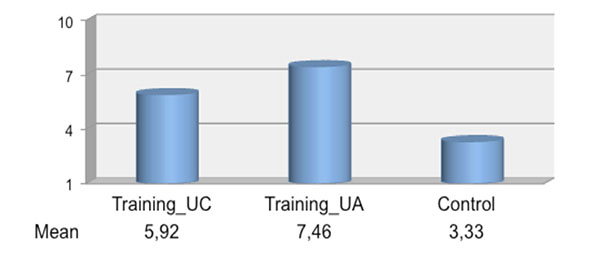

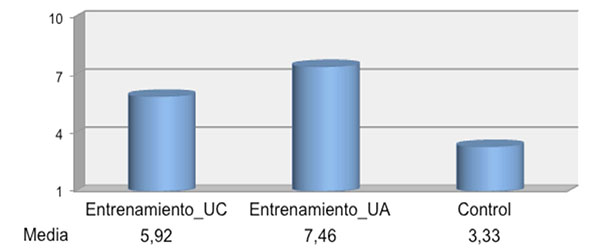

The Kruskal-Wallis test showed significant differences (?2(2)=11.78, p<.01) for the variable «participation in the classroom debates». Also, the Mann-Whitney U test confirmed that the differences between the three groups were significant when comparing the control group with the training groups composed by Chilean students (U=11, p<.01) and Spanish students (U=48.50, p<.05). Therefore, it was shown that students in the training group more positively valued their participation in the classroom as compared to the control group (figure 2).

Figure 2. Average of the scores from the assessment of the their own participation in the classroom debates (maximum score=10).

For each of the conditions, the one sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied, with the test value equal to the average from the answer scale (5.5). This test confirmed that the students in the control group had scores that were significantly lower than this value (T=5, p<.05), while the scores of the students in the training groups, the Chilean students (T=88.5, p<.05) as well as the Spanish students, had scores that were closer to this value (T=184, p=.33).

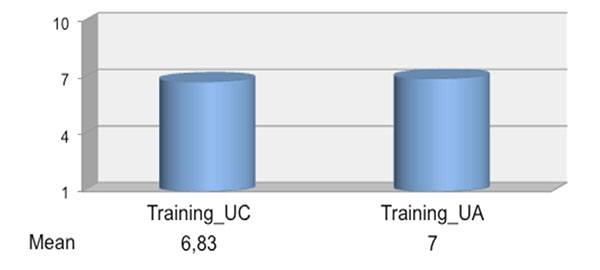

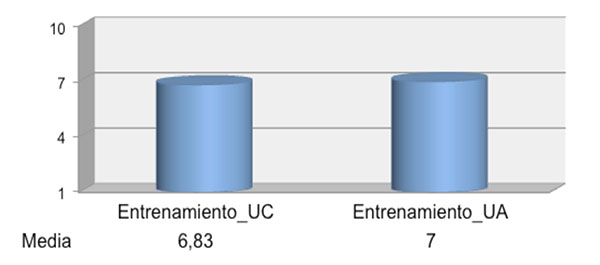

In respect to the online participation in the debates, the Mann-Whitney U test did not show significant differences between the two training groups (U= 152.5, p=.78), as their scores were similar (Figure 3). The one sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used with the test value set equal to the average from the answer scale (5.5). This allowed us to confirm that the scores from the Spanish students (T=238, p<.05) were significantly higher than this test value, and that the Chilean students’ scores did not significantly differ from it (T=60.50, p=.09).

Figure 3. Average of the scores from the assessment of their own participation in the online debates (maximum score=10).

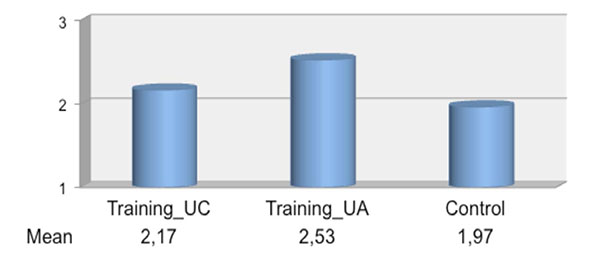

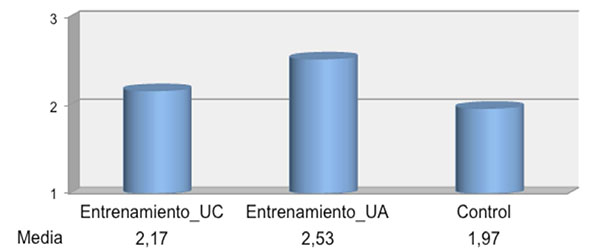

As the score’s assumptions of normality were not met (K-S=0.169, p<.01), non-parametric analyses were performed on the results of the study on the perception of the quality of participation. The Kruskal-Wallis test showed significant differences ?2(2)= 7.90, p<.05) between groups. The Mann-Whitney U test was significant when comparing the control group with the Chilean training group (T=19.50, p<.01), as well as when comparing the two training groups (T=222.50, p<.05). The one sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test with the test value set equal to the average from the answer scale (2), confirmed that the Chilean students’ scores significantly differed from it (T=85, p<.01), and therefore, they were the ones that had the best perception on the quality of their participation on the debates (figure 4).

Figure 4. Average of the scores from the assessment of the quality of their participation in the debates (maximum score=3).

3.3. Evaluation of the innovative teaching of ethics

The students’ evaluation on the different elements of this innovative training program through content analysis of the answers to four open-ended questions is presented below.

In respect of the first question, which referred to the aspects of the training that they most appreciated, the answer of sharing ideas with different students was noted for its frequency (i.e. due to the diversity in cultures and opinions). Variations of this answer were present in 50% of the Chilean students’ comments and 57% of the Spanish students’. On the second question, which asked what they liked the least, 67% of the Chilean students and 100% of the Spanish students expressed their displeasure at the low amount of participation and interaction between them, as they would have liked to have had more expression of opinions and debate by all the students in the twinned groups.

The third question asked about what they had learned thanks to this training, and we found that the UA students, as well as the UC students, pointed to the opportunity to get to know and identify their own and others’ values, debating by reasoning their own stance, and the students specified: «to listen to the people better and try to understand them», «to not judge people due to their decisions, outlandish as they may seem», «having different points of view about the same topic».

Lastly, the fourth open-ended question allowed us to gather their suggestions for the improvement of the future application of this training program. The UC students pointed to the optimization of the coordination to foment participation and interaction (100%), and the UA students mentioned the inclusion of debate topics that were more related to the course, and the improvement of the coordination and time (100%).

4. Discussion

The pedagogic proposal in ethics education described here reflects on the need to plan and develop initiatives from this type of university environment, due to the positive reception by all the participants –professors and students- and as reflected by the results obtained. We believe that the proposal brings to light, in the university classrooms, the difficult task of training upright professionals that together with their scientific and technical training, allows them to build and generalize their social commitment and their humanistic training (Hodelín & Fuentes, 2014).

The active and dialogic methodology designed for this study allowed us to confirm that the possibility to debate in a structured and guided form about a moral dilemma with students from other cultures through the use of communication technology, had favourable effects on the identification of values and stances, on the quality of argument produced and additionally on the participants’ self-evaluation of their own contributions to the debates. The students who were part of this training also expressed a great appreciation for the knowledge gained and debating with different people who had different ideas, and the exercise of comprehension, reasoning and reflection that this activity entailed. These results were very significant as regards the number of intervention sessions, which led us to hypothesize that a more prolonged intervention would bring with it more positive results, and most probably, would be longer lasting as well. As for its application, it would be advisable to plan the online debate following the indications by Bender (2012) on the creation of questions that motivate the participation of the students, without forgetting the adequate management of the cultural differences found in online collaborative behaviour (Kim & Bonk, 2002). It is also important to attend to aspects of the experimental studies to guarantee their external and internal validity (Meza, 2008), for example by adjusting the timetable among all the participants. Furthermore, we believe that the results as a whole point to the need of greater openness and contact between the universities in the different parts of the world. In this sense, we believe that university teaching should offer training in the necessary skills for students’ professional performance away from their own countries. The new communication technologies facilitate this type of training by allowing online interaction with people from all over the world (Merryfield, 2003).

On the other hand, the pedagogic design described herein implies the real application of the truly needed ethics education, which is currently difficult to work with in the university classroom. Thanks to the methodology applied, we overcame one of the limitations mentioned by the teachers when dealing with ethics-related work with the students, which is the possibility of indoctrinating certain values and specific practices (García & al., 2009). From the innovative training described, we uphold the deontological codes of the profession, as well as the universal declarations of human rights and values, so that from this point on, the students are the ones who, through dialogue with diverse types of people, critical thinking and argumentation, solidly construct their personal and professional ethics (Gozálvez & Jover, 2016; Martínez, 2011).

Lastly, it is important to highlight that the internationalization of educational practices require a great effort by all the agents involved, as well as a complex bureaucracy due to the requirement of protecting the students’ data at the universities. However, «if a higher education institution wants to have a teaching system that integrates technologies, it is crucial to have the right institutional technological support. Higher education institutions should provide lecturers and students with technological systems to enable an educational model that integrates technologies to be developed» (Duart, 2011: 11). Taking care of these aspects guarantees an adequate coordination, which is essential so that the educational practices described here become a reality. In this way, we hope that the pedagogic proposal described here serves as a guide, the results reached become the starting point for the reflection on ethics education in the university classrooms, and the difficulties mentioned become another incentive for the passion of training future professionals at the university, as the development of personal and professional ethics will be their best business card.

Support

This work was performed under the framework of a Teaching Innovation Project which was funded by the University of Cantabria (school year 2014-15).

References

Alvear, K., Pasmanik, D., Winkler, M.I., & Olivares, B. (2008). ¿Códigos en la posmodernidad? Opiniones de psicólogos/as acerca del Código de Ética Profesional del Colegio de Psicólogos de Chile (A.G.). Terapia Psicológica, 26, 215-228. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48082008000200008

Barckley, E.F., Cross, K.P., & Howell, C. (2007). Técnicas del aprendizaje colaborativo. Madrid: Morata.

Bender, T. (2012). Discussion-based Online Teaching to Enhance Student Learning. Theory, Practice and Assessment. Virginia: Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Benhabib, S. (2011). Dignity in Adversity: Human Rights in Troubled Times. Cambridge/Malden: Polity Press.

Bolívar, A. (2005). El lugar de la ética profesional en la formación universitaria. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 10, 93-123. (http://intel.ly/1HSx9Bh) (08-07-2015).

Buxarrais, M.R., Esteban, F., & Mellen, T. (2015). The State of Ethical Learning of Students in the Spanish University System: Considerations for the European Higher Education Area. Higher Education Research and Development, 34(3), 472-485. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2014.973835

Cantillo, J., Domínguez, A., Encinas, S., Muñoz, A., Navarro, F., & Salazar, A. (2005). Dilemas morales. Un aprendizaje de valores mediante el diálogo. Valencia: Nau Llibres.

Duart, J.M. (2011). La Red en los procesos de enseñanza de la Universidad [The Net on Teaching Processes at the University].Comunicar, 37, XIX, 10-13. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C37-2011-02-00

Escámez, J., García-López, R., & Jover, G. (2008). Restructuring University Degree Programmes: A New Opportunity for Ethics Education? Journal of Moral Education, 37(1), 41-53. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03057240701803676

Esteban, F., & Buxarrais, M.R. (2004). El aprendizaje ético y la formación universitaria más allá de la casualidad. Teoría de la Educación. 16, 91-108 (http://bit.ly/1P8UZRt) (24-07-2015).

García, R., Sales, A., Moliner, O., & Ferrández, R. (2009). La formación ética profesional desde la perspectiva del profesorado universitario. Teoría de la Educación, 21(1), 199-221 (http://bit.ly/1N7E1wd) (24-07-2015).

Gozálvez, V., & Jover, G. (2016). Articulación de la justicia y el cuidado en la educación moral: del universalismo sustitutivo a una ética situada de los derechos humanos. Educación XXI, 19(1), 311-330. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5944/educXX1.14221

Guerrero, M.E., & Gómez, D.A. (2013). Enseñanza de la ética y la educación moral, ¿permanecen ausentes de los programas universitarios? Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 15(1), 122-135 (http://bit.ly/1QHPs4m) (24-07-2015).

Guiller, J., Durndell, A., & Ross, A. (2008). Peer instruction and critical thinking: Face-to-face or on-line discussion? Learning and Instruction, 18(2), 187-200. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.03.001.

Hodelín, R., & Fuentes, D. (2014). El profesor universitario en la formación de valores éticos. Educación Médica Superior, 28(1), 115-126 (http://bit.ly/1jjlyF6) (24-07-2015).

Jiménez, J.R. (1997). La educación en valores y los medios de comunicación. Comunicar, 9, 15-22 (http://bit.ly/1NOUfL) (28-07-2015).

Jover, G., López, E., & Quiroga, P. (2011). La universidad como espacio cívico: valoración estudiantil de las modalidades de participación política universitaria. Revista de Educación, número extraordinario, 69-91 (http://bit.ly/1P8SzSO) (24-07-2015).

Kim, K.J., & Bonk, C.J. (2002). Cross-cultural Comparisons of Online Collaboration. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 8. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2002.tb00163.x

Kohlberg, L. (1981). Essays in Moral Development. New York: Harper.

Loes, Ch., Pascarella, E., & Umbach, P. (2012). Effects of Diversity Experiences on Critical Thinking Skills: Who Benefits? The Journal of Higher Education, 83(1), 1-25. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2012.0001

López, F., Carpintero, E., Del-Campo, A., Lázaro, S., & Soriano, S. (2010). Valores y desarrollo moral. In El bienestar personal y social y la prevención del malestar y la violencia (pp. 127-184). Madrid: Pirámide.

Martínez, M. (2011). Educación, valores y democracia. Revista de Educación, número extraordinario, 15-19 (http://bit.ly/1LOI53l) (01-07-2015).

Merryfield, M. (2003). Like a Veil: Cross-cultural Experiential Learning Online. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 3(2), 146.-171(http://bit.ly/1PYJwm1) (02-07-2015).

Meza, J.L. (2008). Los dilemas morales: una estrategia didáctica para la formación del sujeto moral en el ámbito universitario. Actualidades Pedagógicas, 52, 13-24. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.19052/ap.1324

Molina, A.T., Silva, F.E., & Cabezas, C.A. (2005). Concepciones teóricas y metodológicas para la implementación de un modelo pedagógico para la formación de valores en estudiantes universitarios. Estudios Pedagógicos, XXXI(1), 79-95. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-07052005000100005

Muhr, T. (2010). Counter-hegemonic regionalism and higher education for all: Venezuela and the ALBA. Globalization, Societies and Education, 8(1), 39-57. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14767720903574041

Nussbaum, M. (2005). El cultivo de la humanidad. Una defensa clásica de la reforma en la educación liberal. Barcelona: Paidós.

Pasmanik, D., & Winkler, M.I. (2009). Buscando orientaciones: Pautas para la enseñanza de la ética profesional en Psicología en un contexto con impronta postmoderna. Psykhe, 18(2), 37-49. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-22282009000200003

Petrova, E. (2010). Democratic Society and Moral Education. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2, 5635-5640. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.919

Río, C. (2009). La docencia de la ética profesional en los estudios de psicología en España. Papeles del Psicólogo, 30(3), 210-219 (http://bit.ly/1MCgE0J) (05-07-2015).

Rodríguez, R.M. (2012). Educación en valores en el ámbito universitario. Propuestas y experiencias. Madrid: Narcea.

UNESCO (2009). Conferencia Mundial sobre la Educación Superior, 2009: La nueva dinámica de la educación superior y la investigación para el cambio social y el desarrollo. Comunicado (http://bit.ly/1on8wrg) (03-07-2015).

Villafaña, R. (2008). Dinámicas de grupo. (http://bit.ly/1IgbDqz) (04-06-2015).

Yepes, G.I., Rodríguez, H.M., & Montoya, M.E. (2006). Experiencia de aprendizaje 4: Actos discursivos: la argumentación. En G.I. Yepes, H.M. Rodríguez & M.E. Montoya (Eds.), El secreto de la palabra: Rutas y Herramientas (http://bit.ly/1R6etpk) (07-07-2015).

Zhu, C. (2012). Student Satisfaction, Performance, and Knowledge Construction in Online Collaborative Learning. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 15(1), 127-136 (http://goo.gl/xlon1X) (05-07-2015).

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

En este trabajo se presentan los resultados de una colaboración internacional para la formación ética centrada en valores personales y profesionales dentro de la educación formal superior empleando las nuevas tecnologías de la comunicación. La formación diseñada basada en la técnica dialógica pretende que el estudiante clarifique sus valores, se posicione ante dilemas éticos y desarrolle estrategias argumentativas, así como un compromiso ético con su profesión y contribución a la sociedad. La principal innovación de esta formación es la incorporación del diálogo online entre grupos de estudiantes heterogéneos por su origen cultural, esto fue posible gracias a la colaboración de dos universidades y al apoyo tecnológico y administrativo aportado por las mismas. Para analizar el efecto de esta formación innovadora se ha empleado un diseño cuasi-experimental con grupo control, en el que se formaba en valores pero no existía la posibilidad de un diálogo online con estudiantes de otra cultura. En este estudio participaron estudiantes de la Universidad Autónoma de Chile y de la Universidad de Cantabria (España). Entre los resultados obtenidos destacamos las mejores calificaciones y positiva valoración de la participación en los debates y del contacto intercultural por parte de los estudiantes que siguieron la formación más innovadora. Estos resultados permiten concluir que la apertura internacional del diálogo gracias al uso de las tecnologías de la comunicación contribuye de forma significativa a la formación ética en la educación superior.

1. Introducción

La contribución desde las instancias educativas superiores a la formación de profesionales con fuertes convicciones éticas es una temática de especial interés. Resulta fundamental que la educación superior además de centrarse en la preparación profesional considere el desarrollo de competencias personales tales como el razonamiento crítico (Nussbaum, 2005). En este sentido, la Declaración Mundial sobre la Educación Superior (UNESCO, 2009: 2) reconoce que la sociedad actual vive una profunda crisis de valores y que, por tanto, «la educación superior debe no solo proporcionar competencias sólidas para el mundo de hoy y de mañana, sino contribuir además a la formación de ciudadanos dotados de principios éticos, comprometidos con la construcción de la paz, la defensa de los derechos humanos y los valores de la democracia». En definitiva, la formación ética se presenta como una necesidad y se ha identificado a la Universidad como una de las entidades responsables, tanto en contextos europeos como americanos (Escámez, García-López, & Jover, 2008; Esteban & Buxarrais, 2004; Jover, López, & Quiroga, 2011; Muhr, 2010; Petrova, 2010).

Esta formación ética en las aulas universitarias es especialmente necesaria en el caso de los futuros profesionales de la Psicología y la Educación, puesto que su labor profesional supone en gran medida un pilar en el que se sustenta el desarrollo de los demás miembros de la sociedad. Sin embargo, esta formación, como indica Bolívar (2005), se convierte en el «currículum nulo» de las carreras universitarias, en el sentido de currículum por omisión al no incluirse de forma explícita las dimensiones necesarias para su futura aplicación en la práctica profesional. Guerrero y Gómez (2013) confirmaron esta ausencia de educación ética y moral de la persona en la región iberoamericana. Concretamente en las titulaciones de Psicología y Educación, se ha puesto de manifiesto la gran importancia que los estudiantes y los colegios profesionales dan a la ética profesional en su formación, a la vez que expresan la escasa o nula atención prestada desde su formación universitaria (Bolívar, 2005; Río, 2009). Especialmente interesante es el resultado sobre los alumnos de Magisterio (Bolívar, 2005) que evidencia una ausencia generalizada del carácter moral de la educación y de la ética profesional docente, pues el foco está centrado más en proveer a los maestros con contenidos y competencias técnicas, que con una conciencia social crítica. En cuanto a la Psicología, y concretamente en el ámbito chileno, la investigación de Alvear, Pasmanik, Winkler y Olivares (2008) pone de manifiesto que estos profesionales muestran una preferencia por su propio juicio personal, antes que por la consideración del código deontológico, en la toma de decisiones con base ética. A este respecto, Pasmanik y Winkler (2009) sostienen que esta tendencia probablemente se deba a la formación ética recibida durante los años universitarios, caracterizada por ser escasa, teórica y descontextualizada, descuidando a su vez la reflexión y el debate.

Es relevante también señalar que son escasos los desarrollos didácticos que realmente concretan cómo enfrentar en las aulas universitarias la formación en valores (Molina, Silva, & Cabezas, 2005; Rodríguez, 2012). La mayoría de la literatura disponible se centra en reflexiones sobre la necesidad de formar en valores en la educación superior, o bien analiza las perspectivas de diferentes agentes implicados en la misma (Buxarrais, Esteban, & Mellen, 2015; Escámez & al., 2008; García, Sales, Moliner, & Ferrández, 2009; Jiménez, 1997). Menos aún son las publicaciones que versan sobre la participación conjunta de universidades de diferentes países, utilizando las posibilidades que las nuevas tecnologías de la comunicación han abierto, si bien estas han sido aprovechadas para el aprendizaje de otros contenidos con resultados positivos (Zhu, 2012) y han confirmado, de esta forma, que la discusión online puede ser una poderosa herramienta para el desarrollo del pensamiento crítico (Guiller, Durndell, & Ross, 2008).

Considerando lo expuesto, desarrollamos en la educación formal superior una propuesta de formación ética mediante el desarrollo de la metodología dialógica, y el uso de las nuevas tecnologías de la comunicación para permitir el contacto entre estudiantes de diversas culturas y titulaciones. La finalidad de esta formación es contribuir a que los estudiantes universitarios construyan racional y autónomamente sus valores y a que, consecuentemente, desarrollen unos principios éticos propios y razonados que les permitan tanto posicionarse con argumentos ante las demandas de la sociedad, como un óptimo desempeño profesional. El carácter cuasi-experimental, internacional y aplicado de nuestra aportación, que concreta en la realidad universitaria la educación ética, supone una pieza clave para avanzar en los propósitos de la educación superior.

1.1. Innovando en la educación ética

La formación diseñada desarrolla una metodología activa basada en la técnica dialógica que pretende que el estudiante clarifique sus valores y se posicione ante los mismos evitando el adoctrinamiento en la resolución de conflictos morales. La base de esta metodología dialógica subyace en la teoría cognitiva del desarrollo moral de Kohlberg (1981) y en otros desarrollos teóricos que aúnan afecto y cognición (Benhabib, 2011), y que defienden una educación moral que ayude a «situarse frente al otro concreto sin perder por ello la posibilidad de apelar a horizontes generales de valor» (Gozálvez & Jover, 2016: 311). Por tanto, se plantea la necesidad de facilitar un marco y un procedimiento para que los valores se experimenten, se construyan y se vivan. La técnica dialógica supone una metodología activa apropiada dado que los valores están insertos en el diálogo (pues requiere de la apreciación del otro) y, a la vez, mediante la escucha, la reflexión y la argumentación se hace un acercamiento a los mismos. Además, los estudiantes, mediante la reflexión y la confrontación de opiniones sobre situaciones conflictivas que sean de su interés personal y profesional, se replantean sus razonamientos favoreciendo su desarrollo moral (López, Carpintero, Del-Campo, Lázaro, & Soriano, 2010; Meza, 2008).

La formación diseñada pretende además potenciar las estrategias argumentativas, dado que los procesos psicológicos propios de la argumentación están vinculados especialmente con la ética, y el dominio del proceso argumentativo tiene gran importancia para la vida familiar, social, política y académica. Yepes, Rodríguez y Montoya (2006) describen que la argumentación consiste en el uso de la palabra para producir discursos en los cuales se toma una posición de manera razonada frente a una temática o una problemática. Plantean que es un evento del pensamiento en el cual se involucran las leyes del razonamiento (la lógica), las reglas para probar o refutar (la dialéctica), y el uso de recursos verbales con el fin de persuadir, aludiendo a los afectos, las emociones y las sugestiones (la retórica). Estas características de la argumentación están vinculadas con la formación en valores; pues la argumentación supone lo contrario a asumir posiciones obcecadas, fanáticas y aferradas a un solo punto de vista.

Por otra parte, del procedimiento diseñado destaca el especial cuidado que se presta a la preparación para el debate, la gestión del mismo y la creación de grupos colaborativos. Un buen diálogo requiere que los participantes expresen libremente lo que piensan, sienten y creen, y muchos pueden presentar resistencias a afrontar ese riesgo (Barckley, Cross, & Howell, 2007). La participación de los estudiantes en un diálogo provechoso supone un reto en contextos caracterizados por fomentar una actitud pasiva, característica de antiguos modelos de la educación superior. Por lo tanto, conviene esforzarse en lograr una adecuada gestión del aula que garantice un clima de confianza y estimule la participación de todos los estudiantes en el debate. El procedimiento seleccionado para alcanzar dicho objetivo fue la técnica de debate denominada panel progresivo pues, como señala Villafaña (2008), permite profundizar en el estudio de un tema, madurar y optimizar ideas o conclusiones, valorar la contribución de todos e integrar a los miembros de un grupo en torno a un tema común.

En este punto conviene también señalar que es esencial el papel del docente en el manejo de la técnica dialógica en el aula y online, así siguiendo a Cantillo y otros (2005), Meza (2008), y Bender (2012), destacamos la consideración en cada etapa de determinados procesos y recursos. Es esencial que en las instrucciones se aclare que el objetivo de la actividad es pensar y razonar individual y conjuntamente posibles soluciones morales y que para ello se empleará el diálogo y el planteamiento de preguntas y objeciones. En el debate, prima que el docente realice cuestiones que guíen la discusión, comenzando con preguntas exploratorias que permitan comprobar que se ha entendido el dilema y que los estudiantes definan su postura, aclaren su estructura de pensamiento y tengan la oportunidad de reconocer que detrás de una misma opinión puede haber razones muy distintas. Se progresa en el debate aumentando la complejidad y estimulando un modo elevado de razonamiento moral, por ejemplo, aportando información nueva, con preguntas sobre hechos ocurridos en su contexto y atendiendo a consecuencias universales. Además, en el diálogo online conviene clarificar explícitamente las expectativas de dicha discusión (ejemplo: en cuanto a la frecuencia y calidad de la participación) y explicar el estilo de las intervenciones online, pues no es el característico de los trabajos formales (Bender, 2012).

1.2. Colaboración internacional para la formación ética en educación superior

La formación ética presentada en este artículo fue llevada a cabo en la Universidad Autónoma de Chile y la Universidad de Cantabria (España). Los estudiantes participantes cursaban asignaturas que coincidían en el entrenamiento de competencias tales como la reflexión socio-moral, la comprensión crítica de la realidad, el diálogo y la argumentación, la toma de perspectiva y una actitud de respeto y tolerancia hacia otras opiniones, así como el meta-conocimiento del propio ser y estar. Esta coincidencia permitió la realización conjunta de esta formación, que se vería favorecida por la fortaleza que supone la diversidad cultural para potenciar el pensamiento crítico (Loes, Pascarella, & Umbach, 2012). La formación ética compartida, por tanto, trató de optimizar la herramienta dialógica (mediante el debate de dilemas éticos) garantizando la diversidad en el grupo de debate online de los estudiantes gracias a la internacionalización y el apoyo en las tecnologías de la información y comunicación (TIC).

Los estudiantes de la universidad española seguían la asignatura denominada «Formación en valores y competencias personales para docentes», impartida en las titulaciones de Grado en Magisterio en Educación Infantil y en Educación Primaria. Los objetivos generales de esta asignatura implican el desarrollo de estrategias para el propio desarrollo socio-emocional y ético, la promoción del bienestar docente y la convivencia en la comunidad educativa, y la reflexión sobre la forma de ser y estar, propia y del otro.

Los participantes chilenos estudiaban la asignatura de Desarrollo Personal IV de la titulación de Psicología cuyos objetivos primordiales son el desarrollo del rol del psicólogo y su compromiso con la ética profesional. En esta asignatura los estudiantes aplican los conocimientos adquiridos sobre las competencias personales e interpersonales en contextos grupales del ámbito educativo. Puesto que se trata de la primera práctica profesional de la carrera, es fundamental que tomen conciencia de la necesidad de una preparación ética para el ejercicio de su profesión.

2. Método

2.1. Diseño de la investigación y participantes

En este estudio participaron 226 estudiantes universitarios en dos condiciones. En la condición de entrenamiento participaron 147 estudiantes, 69 de la Universidad Autónoma de Chile (UA) y 78 de la Universidad de Cantabria (UC). En la condición de control (reciben formación ética sin opción al diálogo online) participaron 79 estudiantes de la UC.

Los datos sobre los resultados académicos se analizaron con toda la muestra. Por otra parte, dado que la valoración de la formación fue anónima y voluntaria, los análisis relativos a dicho indicador se realizaron con los 46 estudiantes que dieron su opinión (13 en la condición de entrenamiento en la UC y 24 en la UA, y 9 en la condición de control).

2.2. Procedimiento

En la formación innovadora en materia de valores se han contemplado las siguientes etapas claves para su desarrollo:

a) Creación de grupos hermanados -heterogéneos culturalmente- y de las TIC. Se estableció un acuerdo de colaboración entre las dos universidades para garantizar la protección de datos y la confidencialidad de los estudiantes, así como para lograr la apertura a los estudiantes chilenos de la plataforma Moodle y de las TIC creadas para tal efecto en la universidad española.

En las aulas de cada universidad participante, se crearon grupos de cuatro o cinco miembros y estos se hermanaron con otro grupo de similar tamaño de la otra universidad. En la plataforma virtual Moodle se creó una wiki por grupo hermanado para que de forma confidencial pudieran compartir, crear y editar diversos tipos de contenidos relativos a sus aproximaciones, así como conversar y dialogar entre ellos.

b) Diseño de los materiales compartidos: bibliografía, exposiciones magistrales, ejercicios, dilema y rúbrica de evaluación. Todos los estudiantes dispusieron de los mismos materiales y bibliografía y las profesoras emplearon las mismas presentaciones para sus clases expositivas. Además, se diseñó una evaluación formativa y sumativa que contribuyera al entrenamiento de los estudiantes.

c) Puesta en marcha de las sesiones y actividades. La formación se desarrolló durante cuatro semanas. La secuencia de las sesiones, llevadas a cabo simultáneamente en las dos universidades, se contempló como sigue:

La primera sesión (dos horas) comienza con una clase expositiva sobre los valores y su importancia para el desarrollo personal y la convivencia. Continúa con los ejercicios de entrenamiento en la clarificación de valores consistentes en un primer acercamiento a la detección de los propios valores, para pasar a la identificación de valores y contravalores en situaciones de interacción propias de los dilemas éticos. Para el entrenamiento de la capacidad argumentativa se realizan tareas de identificación de distintos tipos de argumentos y se practica la estructura argumentativa dialógica en temas controvertidos de su interés (adaptación de Yepes & al., 2006). Esta sesión culmina con la presentación del dilema ético, que consiste en el tráiler de la película «Hacia rutas salvajes» (Into the wild), acompañado de un guion en el que se les insta mediante preguntas a identificar y razonar los valores y contravalores presentes, y a reflexionar sobre su posicionamiento ante el mismo. Se selecciona esta situación como tipo de dilema moral, con el objeto de involucrar a los estudiantes no solo de forma racional, también de forma emotiva. Este tipo de situaciones cercanas al ámbito personal se considera el más acertado para trabajar con dilemas (Meza, 2008).

La segunda semana (una hora) comienza con la aplicación de la técnica de debate de panel progresivo. Así, los estudiantes trabajan en su pequeño grupo dentro del aula, de manera que individualmente van expresando su aproximación; después debaten y realizan un acta que recoge los planteamientos escuchados en el grupo. Únicamente, en la condición de entrenamiento se insta a los estudiantes a que compartan este acta con el grupo hermanado en la wiki de la plataforma virtual Moodle, y a que durante una semana dialoguen online fuera de clase.

En la tercera sesión (una hora) tiene lugar la gran asamblea en el aula. Posteriormente, los estudiantes desarrollan su aproximación individual post debate, fuera del aula.

Durante la última semana las profesoras recogen las aproximaciones individuales pre y post debate de sus estudiantes para evaluarlas según la misma rúbrica de evaluación. Además, se evalúa la formación considerando la percepción de la propia formación seguida mediante una encuesta online.

2.3. Instrumentos de evaluación2.3.1. Rúbrica de evaluación de los resultados académicos

La rúbrica de evaluación comprende los siguientes criterios agrupados en tres apartados con un peso relativo en la nota final (expresado entre paréntesis):

a) En la aproximación individual pre-debate se evalúa el grado en el que se identifican valores y antivalores, y la calidad argumental del posicionamiento inicial (25% en la condición de entrenamiento y 50% en la de control).

b) En la participación en el debate online se considera que los estudiantes publiquen en la wiki de Moodle el acta del debate realizado en el pequeño grupo, la calidad de dichas actas y de los comentarios realizados a los compañeros hermanados en la wiki (35% en la condición de entrenamiento).

c) En la aproximación individual post debate se considera si los estudiantes añaden valores y antivalores; y la medida en la que desarrollan su aproximación final nutriéndose de nuevos argumentos y/o profundizando en los que ya presentaban, partiendo o identificando los posicionamientos vertidos en los debates realizados (40% en la condición de entrenamiento y 50% en la de control).

2.3.2. Apreciación de la propia participación

Los estudiantes valoran su participación en los debates utilizando dos ítems, uno sobre su participación en los debates de clase, y otro acerca de su participación online. Este último ítem no es aplicable a la condición de control, pues esta no incluye debates online. La escala de respuesta a estos ítems osciló entre 1 (nada) y 10 (mucho). Los ítems se plantearon como sigue: «¿Cuánto has participado en el debate generado en el aula?, ¿Cuánto has participado en el debate desarrollado en la wiki?».

Además, se midió la calidad percibida de la participación mediante siete ítems (a=.77, N=46) tomados de Cantillo y otros (2005: 69). Los estudiantes respondieron utilizando una escala de frecuencia en la que 1 implica nunca; 2, a veces, y 3, siempre. Algunos ejemplos de estos ítems son: «Cuando quiero participar pido la palabra» y «No hago ataques personales».

2.3.3. Valoración de la formación

Finalmente, se plantearon cuatro preguntas abiertas con el objeto de que los estudiantes reflexionaran y también informasen sobre el meta-conocimiento alcanzado (es decir: ¿qué has aprendido?), sus preferencias (es decir: ¿qué es lo que más te ha gustado? ¿lo que menos?) y también sobre sus sugerencias para mejorar la metodología y el procedimiento en próximas ediciones (es decir: ¿qué sugerencia/s nos harías para la mejora e innovación de esta formación?).

3. Resultados

3.1. Resultados académicos

Como podemos observar en la figura 1, los estudiantes de la condición de entrenamiento obtuvieron mejores resultados que los de la condición de control.

Figura 1. Media de las calificaciones en cada una de las condiciones (puntuación máxima =10).

El análisis no paramétrico Kruskal Wallis, realizado debido a la falta de homogeneidad de las varianzas (Prueba Levene: F(2,223)=3,65, p<.05), confirmó que estas diferencias en las calificaciones obtenidas fueron significativas (?2(2)=22,76, p<.001). Comparando por pares los grupos de entrenamiento y de control con la prueba U de Mann-Whitney, se obtuvieron diferencias únicamente al comparar el grupo de control con los otros dos grupos de entrenamiento. Por tanto los estudiantes chilenos (U=1.657.5, p<.001) y españoles de la condición de entrenamiento (U=1927, p<.001) presentaron mejores calificaciones que los estudiantes del grupo control.

3.2. Participación en los debates

En primer lugar se presentan las diferencias en cuanto a la apreciación de la participación en los debates realizados en el aula. Se realizaron pruebas no paramétricas dado que no se cumplía el supuesto de normalidad de las puntuaciones ni para la participación en el aula (Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S)=0.154, p<.01) ni para la participación online (K-S=0.167, p<.01).

La prueba de Kruskal Wallis mostró diferencias significativas (?2(2)=11.78, p<.01) para la variable participación en los debates del aula. Además, la prueba U de Mann-Whitney confirmó que las diferencias entre los tres grupos son significativas al comparar la condición de control con la de entrenamiento de estudiantes chilenos (U=11, p<.01) y de estudiantes españoles (U=48,50, p<.05). Por tanto, se demostró que los estudiantes de la condición de entrenamiento valoraban más positivamente su participación en el aula que los de la condición de control (figura 2).

Figura 2. Media de las puntuaciones de la apreciación de la propia participación en los debates del aula (puntuación máxima=10).

En cada condición se realizó la prueba de Wilcoxon de los rangos con signo para una muestra, con el valor de prueba igual a la mediana de la escala de respuesta (5,5), y se confirmó que los estudiantes de la condición de control presentaban unas puntuaciones significativamente inferiores a este valor (T=5, p<.05), mientras que las puntuaciones de los estudiantes de la condición de entrenamiento, tanto de estudiantes chilenos (T=88,5, p<.05) como de estudiantes españoles, presentaban puntuaciones cercanas a este valor (T=184, p=.33).

En cuanto a la participación on-line en los debates, la prueba U de Mann-Whitney no mostró diferencias significativas entre los dos grupos de la condición de entrenamiento (U=152.5, p=.78), sus puntuaciones fueron semejantes (figura 3). La prueba de Wilcoxon de los rangos con signo para una muestra, con el valor de prueba igual a la mediana de la escala de respuesta (5.5), nos permitió confirmar que las puntuaciones de los estudiantes españoles (T=238, p< .05) fueron significativamente superiores a este valor de prueba, y que las de los estudiantes chilenos no diferían significativamente de la misma (T=60,50, p=.09).

Figura 3. Media de las puntuaciones de la apreciación de la propia participación en los debates online (puntuación máxima=10).

Dado que no se cumple el supuesto de normalidad de las puntuaciones (K-S=0.169, p<.01) realizamos análisis no paramétricos en el estudio de la percepción sobre la calidad de la participación. La prueba de Kruskal Wallis mostró diferencias significativas (?2(2)=7.90, p<.05) entre los grupos. La prueba U de Mann-Whitney resultó significativa al comparar el grupo control con el grupo chileno de entrenamiento (T=19,50, p<.01), y al comparar los dos grupos de entrenamiento (T=222.50, p<.05). La prueba de Wilcoxon de los rangos con signo para una muestra, con el valor de prueba igual a la mediana de la escala de respuesta (2), confirmó que las puntuaciones de los estudiantes chilenos diferían significativamente de la misma (T=85, p<.01), y que por tanto, eran los que mejor percepción tenían de la calidad de su participación en el debate (figura 4).

Figura 4. Media de las puntuaciones de la apreciación de la calidad de la propia participación en los debates (puntuación máxima=3).

3.3. Valoración de la formación ética innovadora

Presentamos la valoración que los estudiantes realizaron sobre distintos elementos de la formación innovadora a través del análisis de contenido de las respuestas a las cuatro preguntas abiertas.

En cuanto a la primera cuestión, referida a los aspectos de la formación que más apreciaban, destacó por su frecuencia la respuesta de compartir ideas con otros estudiantes diferentes (ejemplo: por la diversidad cultural y de opiniones). Variantes de esta respuesta estuvieron presentes en el 50% de los comentarios de estudiantes chilenos y el 57% de los estudiantes españoles. En relación a la segunda pregunta, en la que indicaban qué les había gustado menos, el 67% de los estudiantes chilenos y el 100% de los españoles expresaron su disgusto hacia la baja participación e interacción entre ellos, pues les hubiera gustado una mayor expresión de opiniones y debate por parte de todos los estudiantes de cada grupo hermanado.

En la tercera pregunta, sobre lo que consideraban que habían aprendido gracias a esta formación, obtuvimos que tanto los estudiantes de la UA como los de la UC señalaban la oportunidad de conocer e identificar valores propios y ajenos, debatir argumentando la propia postura, y los estudiantes españoles puntualizan: «a escuchar mejor a la gente e intentar comprenderles», «a no juzgar a la gente por sus decisiones por descabelladas que parezcan», «tener diferentes puntos de vista sobre un mismo personaje».

Finalmente, la cuarta pregunta abierta nos permitió recoger sus sugerencias de mejora para futuras aplicaciones del programa de formación. Desde la UC señalan la optimización de la coordinación para fomentar la participación e interacción (100%) y desde la UA, la inclusión de temas de debate más relacionados con la asignatura y la mejora de la coordinación y los tiempos (100%).

4. Discusión

La propuesta pedagógica en educación ética aquí descrita refleja la necesidad de plantear y desarrollar iniciativas de este tipo en el ámbito universitario, dada la acogida positiva de todos los participantes -profesoras y estudiantes- y su reflejo en los resultados obtenidos. Consideramos que esta propuesta concretiza en las aulas universitarias la difícil tarea de formar a profesionales integrales, que unida a su preparación científica y técnica, les permita construir y generalizar su compromiso social y formación humanística (Hodelín & Fuentes, 2014).

La metodología activa y dialógica diseñada nos permite confirmar que la posibilidad de debatir de una forma estructurada y guiada sobre un dilema moral, con estudiantes de otras culturas mediante el uso de las tecnologías de la comunicación, tiene efectos favorables sobre la claridad en la identificación de valores y posicionamientos, la calidad en la argumentación e incluso sobre la valoración de la propia participación en los debates realizados. Los estudiantes que siguieron esta formación, además, expresaron una gran estima por el conocimiento y el debate con personas diferentes, con ideas distintas, y el ejercicio de comprensión, razonamiento y reflexión que la actividad conlleva. Estos resultados son muy significativos en consideración al número de sesiones de la intervención, lo que lleva a hipotetizar que una intervención más prolongada conllevaría consecuencias aún más positivas y, probablemente, más duraderas. De cara a su aplicación sería asimismo aconsejable cuidar el debate on-line siguiendo las indicaciones de Bender (2012) en cuanto a la realización de preguntas que motiven la participación de los estudiantes, sin olvidar la adecuada gestión de las diferencias culturales en las conductas colaborativas online (Kim & Bonk, 2002) y atender a los aspectos propios de los estudios experimentales para garantizar su validez externa e interna (Meza, 2008), como por ejemplo, ajustar al máximo el cronograma entre los participantes. Por otra parte, consideramos que en conjunto estos resultados apuntan a la necesidad de una mayor apertura y contacto entre las universidades de diferentes partes del mundo. En este sentido, creemos que la formación universitaria debería entrenar las habilidades necesarias para desempeñarse como profesionales más allá de las fronteras de los propios países. Las nuevas tecnologías de la comunicación facilitan esta formación al permitir la interacción online con personas de todo el mundo (Merryfield, 2003).

Por otro lado, el diseño pedagógico aquí descrito supone una aplicación real de un aspecto tan necesario, pero a la vez tan difícil de trabajar en las aulas universitarias, como es la educación ética. Con la metodología utilizada, superamos además una limitación señalada por los docentes a la hora de enfrentarse al trabajo ético con los estudiantes, y es la posibilidad de adoctrinar en valores y prácticas concretas (García & al., 2009). Desde la formación innovadora descrita se defiende la consideración de los códigos deontológicos propios de la profesión, además de las declaraciones universales en materia de derechos y valores humanos, para que a partir de ahí sean los propios estudiantes quienes mediante el diálogo con personas diversas, el pensamiento crítico y la argumentación construyan de manera sólida su ética personal y profesional (Gozálvez & Jover, 2016; Martínez, 2011).

Finalmente, es necesario señalar que la internacionalización de la práctica educativa requiere de un gran esfuerzo por parte de todos los agentes implicados, además de una intrincada burocracia dada la exigencia de la protección de datos de los estudiantes en las universidades. Sin embargo, si se quiere disponer «de un sistema docente que integre las tecnologías se requiere del suficiente apoyo tecnológico institucional. La Universidad debe proveer a los docentes y a los estudiantes de los sistemas tecnológicos que permitan el desarrollo de un modelo educativo que integre las tecnologías» (Duart, 2011: 11). El cuidado de estos aspectos garantiza una adecuada coordinación, esencial para que prácticas educativas como la aquí descrita sean posibles. De este modo, esperamos que la propuesta pedagógica descrita sirva de guía, los resultados alcanzados supongan un punto de partida para la reflexión en torno a la educación ética en las aulas universitarias y las dificultades comentadas un acicate más en la pasión por formar en la Universidad a futuros profesionales, pues el desarrollo de una ética personal y profesional será su mejor carta de presentación.

Apoyos

Este trabajo se realizó bajo el marco de un Proyecto de Innovación Docente subvencionado por la Universidad de Cantabria (curso 2014-15).

Referencias

Alvear, K., Pasmanik, D., Winkler, M.I., & Olivares, B. (2008). ¿Códigos en la posmodernidad? Opiniones de psicólogos/as acerca del Código de Ética Profesional del Colegio de Psicólogos de Chile (A.G.). Terapia Psicológica, 26, 215-228. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48082008000200008

Barckley, E.F., Cross, K.P., & Howell, C. (2007). Técnicas del aprendizaje colaborativo. Madrid: Morata.

Bender, T. (2012). Discussion-based Online Teaching to Enhance Student Learning. Theory, Practice and Assessment. Virginia: Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Benhabib, S. (2011). Dignity in Adversity: Human Rights in Troubled Times. Cambridge/Malden: Polity Press.

Bolívar, A. (2005). El lugar de la ética profesional en la formación universitaria. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 10, 93-123. (http://intel.ly/1HSx9Bh) (08-07-2015).

Buxarrais, M.R., Esteban, F., & Mellen, T. (2015). The State of Ethical Learning of Students in the Spanish University System: Considerations for the European Higher Education Area. Higher Education Research and Development, 34(3), 472-485. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2014.973835

Cantillo, J., Domínguez, A., Encinas, S., Muñoz, A., Navarro, F., & Salazar, A. (2005). Dilemas morales. Un aprendizaje de valores mediante el diálogo. Valencia: Nau Llibres.

Duart, J.M. (2011). La Red en los procesos de enseñanza de la Universidad [The Net on Teaching Processes at the University].Comunicar, 37, XIX, 10-13. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C37-2011-02-00

Escámez, J., García-López, R., & Jover, G. (2008). Restructuring University Degree Programmes: A New Opportunity for Ethics Education? Journal of Moral Education, 37(1), 41-53. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03057240701803676

Esteban, F., & Buxarrais, M.R. (2004). El aprendizaje ético y la formación universitaria más allá de la casualidad. Teoría de la Educación. 16, 91-108 (http://bit.ly/1P8UZRt) (24-07-2015).

García, R., Sales, A., Moliner, O., & Ferrández, R. (2009). La formación ética profesional desde la perspectiva del profesorado universitario. Teoría de la Educación, 21(1), 199-221 (http://bit.ly/1N7E1wd) (24-07-2015).

Gozálvez, V., & Jover, G. (2016). Articulación de la justicia y el cuidado en la educación moral: del universalismo sustitutivo a una ética situada de los derechos humanos. Educación XXI, 19(1), 311-330. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5944/educXX1.14221

Guerrero, M.E., & Gómez, D.A. (2013). Enseñanza de la ética y la educación moral, ¿permanecen ausentes de los programas universitarios? Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 15(1), 122-135 (http://bit.ly/1QHPs4m) (24-07-2015).

Guiller, J., Durndell, A., & Ross, A. (2008). Peer instruction and critical thinking: Face-to-face or on-line discussion? Learning and Instruction, 18(2), 187-200. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.03.001.

Hodelín, R., & Fuentes, D. (2014). El profesor universitario en la formación de valores éticos. Educación Médica Superior, 28(1), 115-126 (http://bit.ly/1jjlyF6) (24-07-2015).

Jiménez, J.R. (1997). La educación en valores y los medios de comunicación. Comunicar, 9, 15-22 (http://bit.ly/1NOUfL) (28-07-2015).

Jover, G., López, E., & Quiroga, P. (2011). La universidad como espacio cívico: valoración estudiantil de las modalidades de participación política universitaria. Revista de Educación, número extraordinario, 69-91 (http://bit.ly/1P8SzSO) (24-07-2015).

Kim, K.J., & Bonk, C.J. (2002). Cross-cultural Comparisons of Online Collaboration. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 8. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2002.tb00163.x

Kohlberg, L. (1981). Essays in Moral Development. New York: Harper.

Loes, Ch., Pascarella, E., & Umbach, P. (2012). Effects of Diversity Experiences on Critical Thinking Skills: Who Benefits? The Journal of Higher Education, 83(1), 1-25. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2012.0001

López, F., Carpintero, E., Del-Campo, A., Lázaro, S., & Soriano, S. (2010). Valores y desarrollo moral. In El bienestar personal y social y la prevención del malestar y la violencia (pp. 127-184). Madrid: Pirámide.

Martínez, M. (2011). Educación, valores y democracia. Revista de Educación, número extraordinario, 15-19 (http://bit.ly/1LOI53l) (01-07-2015).

Merryfield, M. (2003). Like a Veil: Cross-cultural Experiential Learning Online. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 3(2), 146.-171(http://bit.ly/1PYJwm1) (02-07-2015).

Meza, J.L. (2008). Los dilemas morales: una estrategia didáctica para la formación del sujeto moral en el ámbito universitario. Actualidades Pedagógicas, 52, 13-24. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.19052/ap.1324

Molina, A.T., Silva, F.E., & Cabezas, C.A. (2005). Concepciones teóricas y metodológicas para la implementación de un modelo pedagógico para la formación de valores en estudiantes universitarios. Estudios Pedagógicos, XXXI(1), 79-95. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-07052005000100005

Muhr, T. (2010). Counter-hegemonic regionalism and higher education for all: Venezuela and the ALBA. Globalization, Societies and Education, 8(1), 39-57. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14767720903574041

Nussbaum, M. (2005). El cultivo de la humanidad. Una defensa clásica de la reforma en la educación liberal. Barcelona: Paidós.

Pasmanik, D., & Winkler, M.I. (2009). Buscando orientaciones: Pautas para la enseñanza de la ética profesional en Psicología en un contexto con impronta postmoderna. Psykhe, 18(2), 37-49. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-22282009000200003

Petrova, E. (2010). Democratic Society and Moral Education. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2, 5635-5640. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.919

Río, C. (2009). La docencia de la ética profesional en los estudios de psicología en España. Papeles del Psicólogo, 30(3), 210-219 (http://bit.ly/1MCgE0J) (05-07-2015).

Rodríguez, R.M. (2012). Educación en valores en el ámbito universitario. Propuestas y experiencias. Madrid: Narcea.

UNESCO (2009). Conferencia Mundial sobre la Educación Superior, 2009: La nueva dinámica de la educación superior y la investigación para el cambio social y el desarrollo. Comunicado (http://bit.ly/1on8wrg) (03-07-2015).

Villafaña, R. (2008). Dinámicas de grupo. (http://bit.ly/1IgbDqz) (04-06-2015).

Yepes, G.I., Rodríguez, H.M., & Montoya, M.E. (2006). Experiencia de aprendizaje 4: Actos discursivos: la argumentación. En G.I. Yepes, H.M. Rodríguez & M.E. Montoya (Eds.), El secreto de la palabra: Rutas y Herramientas (http://bit.ly/1R6etpk) (07-07-2015).

Zhu, C. (2012). Student Satisfaction, Performance, and Knowledge Construction in Online Collaborative Learning. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 15(1), 127-136 (http://goo.gl/xlon1X) (05-07-2015).

Document information

Published on 31/03/16

Accepted on 31/03/16

Submitted on 31/03/16

Volume 24, Issue 1, 2016

DOI: 10.3916/C47-2016-10

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?