Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

This study describes the concepts, historical precedents, language and fundamental experiences of artivism. It shows the research activities from two main universities (Complutense de Madrid in Spain and Nottingham Trent in UK) as well as other cultural institutions (Élan Interculturel from France and Artemiszio from Hungary), which have explored the educational potential of artivism as a new way of achieving social engagement using innovation and artistic creation. The paper defines precisely artivism as a new language which appears outside the museums and art academies, moving towards urban and social spaces. Artivism is a hybrid form of art and activism which has a semantic mechanism to use art as a means towards change and social transformation. The analysis collects some central experiences of the artivist phenomenon and applies semantic analysis, archiving artivist experiences, and using urban walks and situational research, analyses the educational and formative potential of artivists and their ability to break the classroom walls, and to remove the traditional roles of creator and receptor, student and professor, through workshop experiences. Finally, it reflects upon the usefulness of artivism as a new social language and an educational tool that breaks the traditional roles of social communication.

1. Artivism. Conceptual basis

At the dawn of the XXI century, Artivism (a blending of art and activism) arose spontaneously as a global language. It evolved from urban and graffiti art, and situationism, all of which were creative forms from the twentieth-century (Ardenne, 2008; Andreotti & Costa, 1996; Abarca, 2017; Szmulewicz, 2012). With the new century, a communicative explosion stretched beyond technological media, towards urban spaces. Cities became full of conquered spaces regained for expression. The genres, expressive modes, and communication tools, which a massive transcoding (Manovich, 2005) has blended into a new common space, laid the basis for experimentation and transformation of the ways of communicating.

Artivism is based on the recovery of artistic activity for the purpose of immediate social intervention (Expósito, 2013). As explained by Abarca (2016: 2-3), it has specific features that make it eminently ephemeral and practical in its permanent balance between visibility, durability, and risk. As this expert says, “working with a specific context implies playing with the meanings and connotations of the objects that compose it. As with any other form of public art, the final result of a work of urban art is always the sum of the meanings proposed by the artist and those of the elements that were in place”. If the art fulfilled standard functions of transmission of ways of doing things in times long past, of representing the human space, of anchoring social and cultural dynamism in profound perceptions (Coomaraswamy, 1996; Campbell, 1992; Maslow, 1988), the arrival of artivism took a new look at the old concepts by fighting the mercantilist and elitist status of artistic activity.

By applying methodologies of urban walks and analysis in situ (Clarck & Emmel, 2008; Pink, 2007) in our cities, we find an anonymous, ephemeral, collective and dynamic art that invades spaces and spheres of activity traditionally reserved for expressive omission (urban areas, means and places of transition and transport, non-places or sites that have lost their meaning (Augé, 2009), empty containers and moments or times that have lost their function (Sánchez-Ferlosio, 2000), all of which are transformed into the voice of a new, young and creative society.

In the words of Lippard (1984), artivism is not an “oppositional” art (it does not try to criticize or systematically oppose anything) but works with alternative images, metaphors, irony, humor (Fernandez-De-Rota, 2013), provocation or compassion, to generate an informative process. It is both an “outward” and “inward” art, according to Lippard. What distinguishes it from simple political art is the progressive character, under development, which leads it to work within contexts, to be directly involved in the public social space and to represent in direct contact with the recipients (Gianetti, 2004).

Simon Sheikh (2009), with the same idea, indicates that activist art subverts the very notion of ??the aesthetic object, entering into a process of involvement more important than the creative process itself. In progress and dynamic, artivism changes materials and media, practices and styles, roles and rituals, and ceases to be idiomatic in the art world, to become pragmatic in social life (Sheikh, 2009).

The language of artivism is multiple and generative; it does not respect fixed cultural rules. As Abarca points out (2016: 5), “thanks to the unregulated nature of their practice, urban artists can ignore the limits dictated by private property that determine where they can or cannot act. A work of urban art can simultaneously cover two or more contiguous surfaces belonging to different owners, thus ignoring the division of matter and space demarcated by money. Urban art can, therefore, make visible how these limits of action and physical boundaries are arbitrary and cultural. It can return space and matter to its natural state when everything was for everyone’s use, and nobody owned anything”.

Artivism coincides with the most extensive and complex institutional and political crisis in the whole world, in which disenchantment and the dissolution of political symbolism (Dayan, 1998) have led to a lack of faith in traditional political processes.

Our thread will go diachronically from an analysis of the background to the phenomenon, to the study of the language of artivism, specifically addressing the socio-political functions of this language, and finally showing observations obtained from workshops with students that illustrate the formative potential of artivism.

2. Background and first experiences

To understand the phenomenon, we must trace the emergence of political and rupture art in the context of this century. Artivism has its roots in the artistic avant-gardes of the early XX century (Dada, Futurism, Surrealism) (Riemchneider & Grosenick, 1999). Throughout the twentieth century, new names for art such as performance, happening, body, land, video or conceptual art, have implied an essential element of artivism: “the dematerialization of the artistic object” (Valdivieso, 2014: 7): “The background of artivism should be sought within what we might call counter-cultural movements of leftist activism, such as the situationist International (France), the Hippies (USA), the Indiani Metropolitani (Italy), the Provos (Holland) or the Spassguerilla (Germany); all of them emerged in the decade of the sixties and seventies of the last century. In the Spanish case, these practices of creative activism were not articulated until the eighties and nineties within groups such as Agustín Parejo School or La Fiambrera”.

The conceptual art of the mid-twentieth century provides another critical feature, according to Hodge (2016: 186), “they argued that the final product itself is not as important as the process, so that artistic gifts are irrelevant to their goals... conceptual art is an artistic form that confronts and questions the idea of ??producing traditional works of art (...) it has always challenged the established ideas of production, exhibition, and contemplation of art (...) Conceptual artists focus on their ideas and produce an art strange to traditional painting and sculpture that does not need to be seen in a gallery. They deliberately create works that are difficult to classify according to artistic traditions (...) they often reflect their frustration and irritation towards society and political issues”.

One of the trends of XX century art gradually evolved towards a type in which the art object is not the essential element, but placed more importance on the process of generating the work and removing the commercial value of the created object. Contributing to this are the social movements that appear at the end of the XX century, such as the “alter-globalization movement” or “anti-globalization”, which, by the end of the century, generated a new protest vocabulary that would be applied in different contexts of artivism.

In 2014, Julia Ramírez-Blanco, in her work “Artistic Utopias of revolt”, proposes a genealogy of community protest environments, as an art of liberated space, a space taken up by activism to grant social, community or political functions.

In “Art, liquid?”, Bauman (2007: 43) reflecting about the third culture, describes this new art: “Liquid modernity is a situation in which distance, the lapse of time between the new and the discarded, between creation and scum, have been drastically reduced. The result is that destructive creation and creative destruction converge in the same act”.

All the social movements of the beginning of the XXI century are already, in the words of De-Soto (2012), “open source revolutions where knowledge, techniques, practices, and strategies are learned and replicated with improvements”. For these movements, the essential language is artivism. Let’s analyze how it works.

3. The language of artivism: Semantic analysis

Of the artivist forms that we have analyzed and will use in the examination of their social and educational functions, a rich range of expressions have been obtained that use art as a way of channeling ideas. In these, the individual or collective artist, anonymous or identified, recovers a function of correction of a social imbalance (Gianetti, 2004). The strength of artivism lies not merely in its aesthetic avant-garde, but in its catalytic power to point out injustice, inequality or emptiness in human development. This is the common attribute of artivism, where the language it uses is a fundamental feature.

The re-semantical action (to create or rescue new meanings) of the objects, spaces or buildings in the artistic phenomena that we have recorded, functions to revitalize the world of human sensations and cognition. It leaves a trace of the necessary humanization of life in large cities, whose psychological transformation and alienation (Simmel, 2002; Appadurai, 2001) has led to non-places and spaces without meaning, stealing the individual’s capacity to participate.

The groundbreaking, revolutionary and transformative dimension is used here as a way to find a new language. The truncated meanings, the violation of aesthetic categories and conventions, and the break with the traditional order are used to regain communication with the social world.

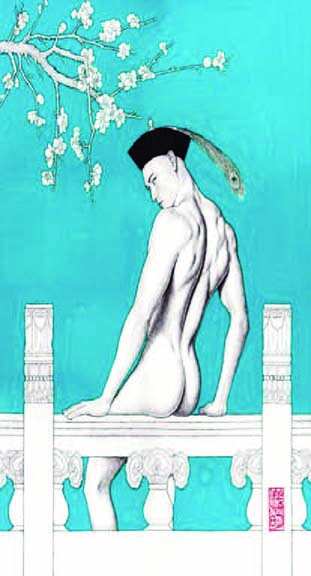

As analyzed by Kombarov (2017: 2), expert in the work of the artivist Pier Pavlensky, whose performance in Moscow is shown in the illustration above, artivism is a means of effective expression because it does not individualize the meaning, but “divides it”, that is to say, by breaking or splitting it into precise planes unlike the usual ones, it re-signifies human presence. Kombarov considers artivism as a new language different from the media, the advertising world, and the cultural industry. This new language appeals to subjectivization, to the use of the body, and other diverse communication systems to avoid the loss of meanings.

The language of artivism often implies the use of the artist’s subject as a means for the disruption of abstraction, or to avoid the loss of representative capacity, and to recover individual freedom of expression. According to Kombarov, the total subjectivization and use of the body and its capabilities in space brings the subject into the public discourse empty of humanity, saturated with imaginary manipulation. In the work of the artist Pavlensky, the positioning of the artist’s body, and the presentation of the subject in the urban space is a process to generate a new human presence. In this process, the subjectivity of the artist is used as a bifurcation system of political discourse, to make it reach the receiver: “The structure of subjectivity is bifurcated: subject is understood as the sensational subject of desires and bodily needs, and on the other hand, the desiring subject finds himself in the discourse, denoting his biological level through the symbolic” (Kombarov, 2017: 4).

This language allows using bodies or objects (Barbosa-de-Oliveira, 2007) as a sensory channel to transmit intellectual experiences that materialize with force: they recreate a space, an object, a subject. These processes link the recipients with the artist in new ways (Kombarov, 2017: 5). As this author understands, the truth, in the process of progressive loss of representational capacity implied in mass society and mass communication, hardly appears anymore, except as an event.

Artivists generate events because they break the structure of conventional communication, erupting into the social space to attract attention and inoculate thought in their recipients. They do it through emotionalization, subjectivization, the rupture and invasion of spaces, or through adapting non-artistic means and times to artistic expression.

In this performance by Pavlensky, the Russian artist sewed his mouth to make a photo session in the Red Square in Moscow, expressing not only political content but an entirely new language. What we see in this artivist is the re-establishment of the power of the body to transmit the desire for freedom. The repressive act is denounced here with beauty, integrity, and clarity. As Lethaby (2017), of the British Arts and Crafts movement, said in the XIX century, preceding artivism, “art is liberated humanity, and everything else is slavery”.

4. Artivism as experiences of autonomy, resistance or disobedience

Artivism is a current language of independence and freedom. In our research activities, we have recorded hundreds of artivism experiences around the globe. We will now highlight some essential prototypes from our archive to study their cases. A clear example is Banksy, graffiti artist, political activist and unidentified film director, who carries out his work from Bristol in the United Kingdom anonymously. The artist defines graffiti as the revenge of the lower class or guerrilla that allows an individual to wrestle power, territory, and glory, in front of a larger and better-equipped enemy. Banksy’s works have addressed various political and social issues, including anti-war, anti-consumerism, and anti-fascism.

Banksy attacks various rules of conventional art. The first one is the authorship of the artist and the cult of the ego. The anonymity of the author, and the always transgressive character of his pieces, which appear on surfaces and spaces of all kinds and all over the world, ends with the convention of art in museums and places of worship. With this communicative power, he draws attention to realities and situations, as he has recently done in the border territories dividing Israel and Palestine. In addition, it fulfills the requirement of ephemeral art, which has been erased or eliminated in many parts of the world. And it is entirely outside the market.

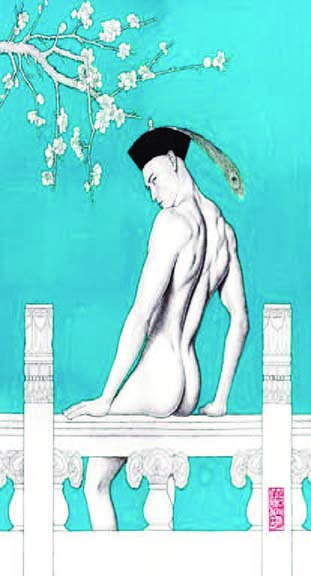

Especially compelling is the case of China where, under apparent calm, powerful forms of artivist protest have been developing. One of the most famous is the Chinese artivist Ai-Wei-Wei. Another crucial example is that of the artivist Wang-Zi. As a gay man, something considered a crime in his country; he has resorted to the popular art of paper cuttings that constitute a collective cultural memory, to represent the life and emotions of the gay individual. Wang-Zi has been incorporating new forms of artistic expression into his repertoire.

In Spain, the economic crisis of recent years has become a true incubator for artivism. Luzinterruptus, a collaborative and anonymous group created in 2008 and working in large cities such as Madrid and Berlin, is characterized by interventions in the public space using light as raw material. In 2014, they carried out their protest action in Madrid “The Police Is Present”, in rejection of what is popularly known as the muzzle law, referring to the Organic Law of Protection of Citizen Security, approved by the Popular Party in July 2015.

The artivists of this group work with the luminous flux and its supports, and their performances are always associated with this element. To protest about the presence of police in the streets, they generated a visual trompe l’oeil with illuminated boxes on cars. The playfulness, surprise, and creation make us visualize the idea of ??artists. As indicated by Clark & ??Kallman (2011), “in an increasingly alienated public space, these displays, which recover the artistic voice, bring us closer again to the “civitas”, to the “active democratic citizenship space”.

A similar Spanish example is that of the collective Basurama, founded in 2001, which is an example of activist creativity that has centered its area of ??study and action on production processes and the generation of waste involved. The “Agostamiento Project” was a site-specific contribution to the “Abierto x Obras program” that took place in the old cold storage room of the Slaughterhouse in Madrid. The collective proposed an interior landscape created by planting 7,000 sunflowers that had been cultivated next to the inhabitants of the “Gran Vía del Sureste”, in the “Ensanche de Vallecas”, an iconic neighborhood of the real estate bubble. Their creation, in the words of Basurama, “is an invitation to chat and eat sunflower seeds, looking to the future from the darkest place”. This project was made in Madrid in 2016.

The rediscovery of public space or the shared world allows artivists to illuminate social life. With it, the artivists get “a spatial reconfiguration of the perceptible and the thinkable, as a promise of a new territory of the possible” (Segura-Cabañero & Simó-Mulet, 2017). Following these outstanding examples analyzed from our files, let us proceed with an explanation of the links between artivism and educational contexts to which we may have access.

5. Educational functions. Artivism workshops

Once the prototypes were known, we developed experiences in artivism workshops for young people. After several weeks working with artivists and young university students, artivism turned out to be a fundamental educational form, in addition to a language and way of communicating and expressing autonomy, dissidence, and opposition. If, as we know, the revolution of the XXI century is above all an educational revolution, in which the learning communities obtain their education from breaking the limits in classrooms, in search of new identities, new ways of understanding meanings and adopting new educational roles (Wenger 1998; Aparicio-Guadas, 2004), artivism offers us a new channel for educational communication.

Indeed, education, which has been in crisis for over a decade must abandon the hindrances identified by researchers (Aguaded, 2005): the absence of freedom, the “writing-centrism”, the mastery of theoretical knowledge, students in a passive and receptive position, and rigidity in positions and academic roles (Aguaded, 2005: 30). Instead, in the “educommunication” leading up to the halfway point of the XXI century, the approaches to education proposed by authors such as Paulo Freire and Mario Kaplún rule, in which not only communication and education are seen in intimate relation, but with a liberating purpose of global civic education (Middaugh & Kahne, 2013; Pegurer-Caprino & Martínez-Cerdá, 2016). In the processes in which educommunication advances towards constituting a liberating element and a generator of active communities capable of empowering themselves, artivism can provide all the necessary elements to re-signify teaching and move away from the formation of mercantilism or the extreme reification of culture.

As De-Gonzalo and Pérez-Prieto, who collaborated with us in the workshops as leading artists, state in their work “La Intención” (2008), these are some of the normal educational functions of artivism that are effects of this part of our work:

1) Artivism integrates the individual in the symbolic construction of reality, away from the passive positions to which global communication, digital technologies or advertising and political indoctrination lead. Artivism is immediate social intervention, participation, and active awakening. Culture is fundamentally experienced (La Intención, 2008). And art is of great interest for those phenomena that engender what these authors call “generative chains” (2008). These generative chains are effectively produced in workshops with young people, renewing in them the impulse towards the conservation and generation of culture, that is, producing true education.

2) Artivism generates in people languages ??to express themselves, becoming emitters, and not just recipients of messages. The manufactured, constructed character, the craftsmanship of artivist interventions teaches how to proceed to participate, moving away from the traditional forms of art and leading to the disappearance of their effect on everyday life.

3) Culture is a necessary food for human socialization. With it the individual is freed from competitive, passive, commodified views of life, adopting a playful, hedonistic, shared or generous vision of it. Artivism is a social ethics literacy, which leads to a “non-individualistic autonomy” of the person (2008). In the world of art, the simple political idea of ??the search for equality is transcended, in favor of an idea not of egalitarian unification, but of similar creative expansion of the diverse, in a qualitative and attributive equality.

4) In the end, artivism guarantees the integration of the individual in a construction of collective spaces and contexts, which is both individual and marked by the creative personality of each human being in their different capacity. Art and creation have personal traces, and at the same time, they are collective and collaborative contributions. It is again a transcendent function of the individualistic/social dilemma of the non-artistic ways of conceiving social life.

Artistic literacy has to do with the ability of art to re-establish and channel human expression. As Abarca (2016: 8) indicates, “a work of urban art allows the viewer to measure the physical dimension of the environment by projecting its own physical dimension on it”. The creative environments generated in artivism humanize spaces (Garnier, 2012) and involve young people, as we can see in the workshops we have organized. Creativity expands in a network among young people (Hernandez-Merayo & al., 2013). This art regains its educational function because it gives young people an active and participatory role.

The sociopolitical literacy of artivism works at deep levels of human experience, beyond the construction of the usual maps of meaning and universes in which the media, political institutions, economic and productive powers emit their dominant imaginaries (Castoriadis, 1975). At this deep cognitive level, art can establish new ways of facing the human experience (Toro-Alé, 2004; García-Andújar, 2009). And, when it triggers actions such as the construction of a collage or the painting of a wall in an urban garden, what we appreciate is how it anchors cognition and direct action in a unique educational link. As Abarca (2016: 9) reiterates, “urban art is, therefore, a call to action. It makes the viewer aware of its own power. It brings us back to the time when each person could reorder their environment as much as the potential of their body allowed before the moment in which the power of a few began to determine the limits of action of all others. It evokes that inherently human reality, repressed by the alienating environment in which we live”.

The process of converting artivism into a form of social literacy has multiple beneficial results. This is a series of results from our research that we wish to highlight here, obtained from the direct participation of young people in our artivism workshops:

• It directly connects with the need for practical integration and participation of young people sentenced today to passive roles and rejected by the professional world.

• It rescues the normal functions of art towards its de-commodification and recovery of a spontaneous and non-speculative character.

• It breaks academic and professional barriers about who can or cannot intervene, reversing the traditional roles of cultural expression.

• It re-signifies urban spaces degraded or without personality.

• It acts at the level of fundamental cognitions of the environment in which we live. It undoes the tendency to fictionalize social life, encouraged by the rise of digital media, indicating the immediate material dimension of human existence.

• It connects the life of young people with material and pragmatic aspects that make them co-responsible for the social structure and urban context. It invites participation in their creative environments and transmits to young people the spirit of rupture and liberation that always accompanies dynamic initiatives of social action. These results derive from the concrete experiences of artists, students and researchers in the artivism environment. In educational contexts related to citizen participation, social action and the development of communication, artivism liberates an entirely new capacity and energy.

6. Conclusions

Our study establishes concepts, linguistic descriptions and cultural and educational functions of artivism, with examples on a global scale, and explores its potential as a new formative language.

The development of analyses, archive, and experiences in workshops has allowed us to justify the importance of the artivist phenomenon in real contexts of education and social life.

As Lippard (1984) observes, artivism tends to see art as a mutually stimulating dialogue, and not as a specialized lesson or an ideology imparted from above. Its dynamism, its expressiveness, the rupturing structure of its language, makes it an art for non-artists, an instrument of creation for the non-creative, and therefore, an ideal way toward change and social evolution. It is a new form of freedom.

According to Valdivieso (2014: 20), the attention that the “official channels” of the world of art have been giving to artivism lately entails a danger: the instrumentalization of protest movements, from the art system, and the reduction of these to mere artistic expressions, thus neutralizing and anesthetizing its political and social intentions through its “museumalization”.

However, artivism moves away from pure aesthetic art and approaches non-artistic expression, to environments and non-artistic media, as Mullin (2017) says. It creates a dialogue with amateurism, with the hybrid and heterodox spirit. It introduces rupture, the carnivalesque, and mockery in traditional canonical styles. All this leads it to the reintegration of art in the social environment, and to enrich the conventional artistic medium with imagination and life, while putting it at the service of educational needs, which are vital today.

Funding agency

This research is carried out and disseminated with the help of the European Project 2016-1-FR02-KA205-011291 “Artivism: Artistic Practices for Social Transformation”. Erasmus + Key Action 2 “Strategic Partnership” Program.

References

Abarca, J. (2006). Del arte urbano a los murales. ¿Qué hemos perdido. In P. Soares-Neves (Ed.), Street art & urban creativity scientific journal, 2, 2. Lisboa. www.urbanario.es

Abarca, J. (2009). Qué es en realidad el arte urbano. Tribuna Complutense 88, Madrid, 2009-05-26.

Abarca, J. (2010). El papel de los medios en el desarrollo del arte urbano. Revista de la Asociación

Abarca, J. (2017). Breve introducción al grafitti. [blog]. https://bit.ly/2rB6iLe

Aguaded, I. (2005). Strategies of edu-communication in audiovisual society. [Estrategias de edu-comunicación en la sociedad audiovisual]. Comunicar, 23, 25-34. https://bit.ly/2rHA1Ci

Aladro, E. (2017). El lenguaje digital, una gramática generativa. CIC, 22, 136-151. https://doi.org/10.5209/CIYC.55968

Aladro, E. (2018). Los mapas, la vida digital y los mundos que descibrimos. Telos. https://bit.ly/2Is0oWv

Andreotti, L., & Costa, X. (1996). Situacionistas: Arte, política, urbanismo. Barcelona: Museu d’Art Contemporani.

Aparicio-Guadas, P. (2004). The resorts in the creativity and emancipation development. [Recursos en el desarrollo de la creatividad y la emancipación]. Comunicar, 23, 143-149.

Appadurai, A. (2001). La Modernidad desbordada. Dimensiones culturales de la globalización. México: FCE.

Aragonesa de Críticos de Arte, 12, septiembre de 2010.

Ardenne, P. (2008). Un arte contextual. Murcia: Cendeac.

Augé, M. (2009). Los no lugares. Espacios en el anonimato. Antropología de la modernidad. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Barbosa-De-Oliveira, L.M. (2007). Corpos indisciplinados. Ação cultural em tempos de biopolítica. São Paulo: Beca.

Bauman, Z. (2007). Arte, ¿líquido? Madrid: Sequitur.

Bourriaud, N. (2006). Arte relacional. Buenos Aires: Adriana Gil Editora.

Bourriaud, N. (2008). Topocrítica. El arte contemporáneo y la investigación geográfica. In M.A. Hernández-Navarro (Ed.), Heterocronías, tiempo, arte y arqueología. Murcia: Cendeac.

Campbell, J. (1992). Las máscaras de dios. Vol III: Mitología creativa. Madrid: Alianza.

Carpiano, R.M. (2009). Come take a walk with me: The ‘go-along’ interview as a novel method for studying the implications of place for health and well-being. Health & Place, 15, 263-272.

Castoriadis, C. (1975). La institución imaginaria de la sociedad. Barcelona: Tusquets.

Clark, A., & Emmel, N. (2008). Walking interviews: More than walking and talking. Presented at ‘Peripatetic Practice: A workshop on walking’. London, March 2008.

Clark, T.N., & Kallman, M. (2011).The global transformation of organized groups: New roles for community service organizations, non-profits, and the new political culture. Beijing: Ministry of Civil Affairs.

Coomaraswamy, A. (1996). La transformación de la naturaleza en arte. Barcelona: Kairós.

Dayan, D. (1998). La historia en directo. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili.

De-Gonzalo, M., & Pérez-Prieto, P. (2008). La Intención. Un proyecto de Marta De-Gonzalo y Publio Pérez-Prieto sobre Educación y para una Alfabetización Audiovisual. Madrid: Entreascuas.

De-Soto, P. (2012). Los mapas del #15M: El arte de la cartografía de la multitud conectada en redes, movimientos y tecnopolítica. Barcelona: Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, Internet Interdisciplinary Institute.

Expósito, M. (2013). La potencia de la cooperación. Diez tesis sobre el arte politizado en la nueva onda global de movimientos. Barcelona: MACBA. https://bit.ly/2rAHSRU

Fernández-De-Rota, A. (2013). El acontecimiento democrático. Humor, estrategia y estética de la indignación. Revista de Antropología Experimental, 13, 1-25. https://bit.ly/2Ik3nkr

Frúgoli, J., & al., (Eds.) (2006). As cidades e seus agentes: Prácticas e representações. Belo Horizonte: Pucminas / Universidade da São Paulo.

García-Andújar, D. (2009). Reflexiones de cambio desde la práctica artística. In J. Carrión, & L. Sandoval (Eds.), Infraestructuras emergentes. Valencia: Barra Diagonal, pp. 100-103.

Garnier, J.P. (2012). De la réappropiation de l'espace public au développement urbain durable: Des mythes aux réalités, en Alternatives non-violentes 165 (octubre), 8-13. https://bit.ly/2rOBK91

Gianetti, C. (2004). Agente interno. El papel del artista en la sociedad de la información. Inventario, 10, 1-5. Madrid: AVAM. https://bit.ly/2jWCuo1

Hernández-Merayo, E., Robles-Vilchez, C., & Martínez-Rodríguez, J.B. (2013). Interactive youth and civic cultures: The educational, mediatic and political meaning of the 15M. [Jóvenes interactivos y culturas cívicas: sentido educativo, mediático y político del 15M]. Comunicar, 40, 54-61. https://doi.org/10.3916/C40-2013-02-06

Hodge, S. (2016). 50 cosas que hay que saber sobre arte. Barcelona: Ariel.

Kombarov, V. (2017). Alone voice onstage at Russianmedia : Subjectivation through bodily symbolism as avant-garde political discourse (Pavlensky Case). Presented at ESA Congress, Athens, August 2017.

Lethaby, W.R. (2017). Catálogo de la Exposición «William Morris y Compañía: El movimiento Arts and Crafts británico». Madrid: Fundación Juan March.

Lippard L. (1984). Trojan horses, activist art and power en VVAA (1984): Art after Modernism. Rethinking representation. New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art.

Manovich, L. (2005). El lenguaje de los nuevos medios de comunicación. Barcelona: Paidós,

Maslow, A. (1998). La personalidad creadora. Barcelona: Kairós.

Middaught, E., & Kahne, J. (2013). New media as a tool for civic learning. [Nuevos medios como herramienta para el aprendizaje cívico]. Comunicar, 40, 99-108. https://doi.org/10.3916/C40-2013-02-10

Mullin, A. (2017). Feminist art and the political imagination. https://bit.ly/2I7sKps

Pegurer-Caprino, M., & Martinez-Cerdá, J.F., (2016). Media literacy in Brazil: Experiences and models in non-formal education. [Alfabetización mediática en Brasil: experiencias y modelos en educación no formal]. Comunicar, 49, 39-48. https://doi.org/10.3916/C49-2016-04

Pink, S. (2007). Walking with video. Visual Studies, 22, 240-252. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725860701657142

Ramírez-Blanco, J. (2014). Utopías artísticas de revuelta. Madrid: Cátedra, Cuadernos Arte.

Riemchneider, B., & Grosenick, U. (1999). Art at the end of the Millenium. Köln: Taschen.

Sánchez-Ferlosio, R. (2000). El alma y la vergüenza. Madrid: Destino.

Segura-Cabañero, J., & Simó-Mulet, T. (2017). Espacialidades desbordadas, en Arte, Individuo y Sociedad, 29, 219-234. https://bit.ly/2GgBFPN

Sheikh S. (2009). Positively trojan horses revisited journal #09. New York: e-flux. https://bit.ly/2IBuUgI

Simmel, G. (2002). Las grandes ciudades y la vida del espíritu. Madrid: Taurus.

Szmulewicz R.I. (2012). Fuera del cubo blanco. Lecturas sobre arte público contemporáneo. Santiago de Chile: Metales Pesados.

Toro-Alé, J.M. (2004). Crea-ti-vity, body and communication. [Crea-ti-vida-d, cuerpo y comunicación]. Comunicar, 23, 151-159. https://bit.ly/2Nf4dOi

Valdivieso, M. (2014). La apropiación simbólica del espacio público a través del artivismo. Las movilizaciones en defensa de la sanidad pública en Madrid. Scripta Nova, 18(493), 1-27. https://bit.ly/2IokbCW

Wang, X., Yu, Z., Cinderby, S., & Forrester, J. (2008). Enhancing participation: Experiences of participatory geographic information systems in Shanxi province. China Applied Geography, 28, 96-109. http://10.1016/j.apgeog.2007.07.007

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Este estudio describe los conceptos, antecedentes, lenguaje y experiencias fundamentales del artivismo, a partir de las actividades de estudio en la Universidad de Nottingham Trent y en la Universidad Complutense de Madrid, con la colaboración de otras entidades culturales como la francesa Élan Interculturel (Francia) y Artemiszio (Hungría), explorando la capacidad educativa de nuevas formas de compromiso social mediante la innovación y creación artística. El artículo acota y define el artivismo como un nuevo lenguaje que surge del desborde de la creación artística académica y museística, hacia los espacios y lugares sociales. El artivismo, hibridación del arte y del activismo, tiene un mecanismo semántico en el que se utiliza el arte como vía para comunicar una energía hacia el cambio y la transformación. El análisis recoge algunas de las principales experiencias en artivismo mediante diversas técnicas –estudio de ejemplos de artivismo mediante análisis semántico, realización de archivo de fenómenos artivistas siguiendo metodologías de paseos urbanos e investigación situacional, y estudio de la capacidad didáctica y formativa de los artivistas y sus trabajos por su facilidad para romper los muros de las aulas e invertir los roles de creador y espectador, alumno y profesor, mediante experiencias en talleres– para de esta manera reflexionar finalmente sobre la utilidad del artivismo como nuevo lenguaje social y como herramienta educativa, capaz de romper los roles tradicionales de la comunicación social.

1. Artivismo. Bases conceptuales

El artivismo (arte y activismo unidos) surge espontáneamente en el albor del siglo XXI como un lenguaje global. Es heredero del arte urbano, del situacionismo y del arte del grafitti, provenientes del siglo XX (Ardenne, 2008; Andreotti & Costa, 1996; Abarca, 2017; Szmulewicz, 2012). Con el nuevo siglo, una explosión comunicativa desborda los medios tecnológicos hacia los espacios urbanos. Las ciudades se pueblan de espacios reconquistados para la expresión. Los géneros, los modos expresivos, las herramientas de comunicación, que una transcodificación masiva (Manovich, 2005) ha fundido en un nuevo espacio común, ponen la base para la experimentación y transformación de los modos de comunicar.

El artivismo se basa en la recuperación de la acción artística con fines de inmediata intervención social (Expósito, 2013). Como recoge Abarca (2016), tiene unos rasgos específicos que lo hacen eminentemente efímero y práctico: en él existe un permanente equilibrio buscado entre visibilidad, durabilidad y riesgo. Como dice este experto, «trabajar con un contexto concreto implica jugar con los significados y connotaciones de los objetos que lo componen. Como ocurre con cualquier otra forma de arte público, el resultado final de una obra de arte urbano es siempre la suma de los significados propuestos por el artista y los de los elementos que estaban en el lugar». Si el arte cumplió en su momento funciones normales de transmisión de modos de hacer las cosas, de representar el espacio humano, de anclar en percepciones profundas el dinamismo social y cultural (Coomaraswamy, 1996; Campbell, 1992; Maslow, 1988), el artivismo viene a refrescar aquella antigua capacidad, combatiendo la evolución mercantilista y elitista de la actividad artística.

Aplicando metodologías de paseos urbanos y análisis en situación (Clarck & Emmel, 2008; Pink, 2007) en nuestras ciudades hallamos un arte anónimo, efímero, colectivo, dinámico, que invade espacios y esferas de actividad tradicionalmente reservadas a la omisión expresiva (espacios urbanos, medios y lugares de transición y transporte, no lugares o lugares que han perdido su sentido (Augé, 2009) y contenedores vacíos y momentos o tiempos que han perdido su función (Sánchez-Ferlosio, 2000), para convertir a todos ellos en la voz de una sociedad nueva, joven y creativa.

En palabras de Lippard (1984), el artivismo no es un arte «oposicional» (no trata de criticar u oponerse sistemáticamente a nada), sino que trabaja con imágenes alternativas, metáforas, ironía, humor (Fernandez-De-Rota, 2013), provocación o compasión para generar un proceso informativo. Es tanto un arte «hacia fuera» como «hacia dentro», según Lippard. Lo que lo distingue del simple arte político es el carácter progresivo, en desarrollo, que lleva a trabajar dentro de los contextos, a implicarse directamente en el espacio social público y a representar en contacto directo con los receptores (Gianetti 2004). Simon Sheikh (2009) en la misma idea, indica que el arte activista subvierte la idea misma del objeto estético, entrando en un proceso de implicación más importante que el proceso creativo. Procesual y dinámico, el artivismo cambia de materiales y medios, de prácticas y de estilos, de roles y rituales, dejando de ser idiomático en el mundo del arte, para ser pragmático en la vida social (Sheikh, 2009).

El lenguaje del artivismo es múltiple y generativo, no respeta las reglas culturales fijas. Como apunta Abarca (2016: 5), «gracias a la naturaleza no regulada de su práctica, un artista urbano puede ignorar los límites dictados por la propiedad privada que determinan dónde puede o no puede actuar. Una obra de arte urbano puede cubrir simultáneamente dos o más superficies contiguas pertenecientes a diferentes dueños, ignorando así la división de materia y espacio demarcada por el dinero. El arte urbano puede por tanto hacer visible cómo estos límites de acción y estas demarcaciones físicas son arbitrarias y culturales. Puede devolver el espacio y la materia a su estado natural, cuando todo era de uso de todos y nadie poseía realmente nada».

El artivismo coincide con la crisis institucional y política más extensa y compleja en todo el globo, en la que el desencanto y la disolución del simbolismo político (Dayan, 1998) han llevado a una falta de fe en los procesos políticos tradicionales.

Nuestro hilo conductor irá diacrónicamente del análisis de los antecedentes del fenómeno, al estudio del lenguaje del artivismo, para abordar ya concretamente las funciones sociopolíticas de dicho lenguaje y, finalmente, mostrar observaciones obtenidas en talleres con estudiantes que ilustran el potencial formativo del artivismo.

2. Antecedentes y primeras experiencias

Para comprender el fenómeno debemos rastrear el surgimiento del arte político y rupturista en los antecedentes de nuestra época. El artivismo tiene sus raíces en las vanguardias artísticas del comienzo del siglo XX (dadá, futurismo, surrealismo) (Riemchneider & Grosenick, 1999). A lo largo del siglo XX nuevos nombres para el arte como performance, happening, body art, land art, video art o arte conceptual, implican un elemento esencial del artivismo: «la desmaterialización del objeto artístico» (Valdivieso, 2014: 7). «Sus antecedentes habría que buscarlos dentro de lo que podríamos denominar movimientos contraculturales de activismo de izquierdas, tales como la Internacional situacionista (Francia), los Hippies (EEUU), los Indiani Metropolitani (Italia), los Provos (Holanda) o la Spassguerilla (Alemania); todos ellos surgidos en las décadas de los años sesenta y setenta del pasado siglo. En el caso español estas prácticas de activismo creativo no se articularon hasta las décadas de los ochenta y noventa dentro de colectivos como Agustín Parejo School o La Fiambrera».

El arte conceptual de mitad del siglo XX aporta a su vez otro rasgo clave, según Hodge (2016: 186), «defendían que el producto final en sí no es tan importante como el proceso, de manera que las dotes artísticas son irrelevantes para sus metas... el arte conceptual es una forma artística que confronta y cuestiona la idea de producir obras de arte tradicionales... siempre ha desafiado a las ideas establecidas de producción, exposición y contemplación del arte (…). Los artistas conceptuales se concentran en sus ideas y producen un arte ajeno a la pintura y la escultura tradicionales que no necesita ser visto en una galería. Generan deliberadamente obras difíciles de clasificar de acuerdo a las tradiciones artísticas... con frecuencia reflejan su frustración e irritación para con la sociedad, y temas políticos».

El arte del siglo XX evoluciona progresivamente, en una de sus facetas, hacia un tipo en el que el objeto artístico no es lo esencial, que prima el proceso de generación de la obra y se deshace del valor comercial del objeto creado. A ello contribuyen los movimientos sociales que empiezan a darse a finales del siglo XX, como el «movimiento alter-globalizador», o «antiglobalización» generando a finales del siglo un nuevo vocabulario de protesta que va a ser aplicado en distintos contextos del artivismo. En 2014, Julia Ramírez-Blanco con su Utopías artísticas de revuelta propone una genealogía de los entornos de protesta comunitarios mediante el arte del espacio liberado, espacio tomado por el activismo para otorgarle funciones sociales, comunitarias o políticas.

En «Arte, ¿líquido?», Bauman (2007: 43), sobre la tercera cultura, describe este nuevo arte: «La modernidad líquida es una situación en la que la distancia, el lapso de tiempo entre lo nuevo y lo desechado, entre la creación y el vertedero han quedado drásticamente reducidos. El resultado es que convergen en el mismo acto la creación destructiva y la destrucción creativa».

Todos los movimientos sociales del comienzo del siglo XXI son ya, en palabras de De-Soto (2012), «revoluciones de código abierto donde saberes, técnicas, prácticas y estrategias son aprendidas y replicadas con mejoras». Para estos movimientos el lenguaje esencial es el del artivismo. Vamos a analizar cómo funciona.

3. El lenguaje del artivismo: Análisis semántico

De las formas artivísticas que hemos analizado y de las que hablaremos al analizar sus funciones sociales y educativas, se obtiene una rica gama de expresiones que utilizan el arte como vía de canalización de ideas. En ellas, el artista individual o colectivo, anónimo o identificado, recupera una función de corrección del desequilibrio social (Gianetti, 2004). La fuerza del artivismo no radica simplemente en su vanguardia estética, sino en su poder revulsivo para señalar la injusticia, la desigualdad o el vacío en el desarrollo humano. Este es el rasgo común del artivismo. Y es el lenguaje que utiliza lo que constituye su rasgo fundamental.

La resemantización (recubrir o rescatar significados) de los objetos, espacios o edificios en los fenómenos artísticos archivados tiene una función revivificante en el mundo de sensaciones y cogniciones humanas. Deja huella de la humanización necesaria de la vida en las grandes ciudades, cuya psicologización y alienación (Simmel, 2002; Appadurai, 2001) ha conducido a los no-lugares y espacios sin significado, hurtados a la participación del individuo.

La dimensión rompedora, revolucionaria y transformadora es usada aquí como vía para fundar una nueva lengua. Los lenguajes truncados, la violación de las categorías y convenciones estéticas, y la ruptura con el orden tradicional, se utilizan para la recuperación de la comunicación con el mundo social.

Como analiza Kombarov (2017: 2), experto en la obra del artivista Pier Pavlensky, cuya performance en Moscú vemos en el Gráfico 2, el artivismo es un medio de expresión eficaz porque no individúa la expresión, sino que, «dividuándola», es decir, rompiéndola o dividiéndola precisamente en planos diversos a los habituales, resemantiza la presencia humana. Kombarov considera el artivismo como un nuevo lenguaje, diferente al de los medios de comunicación, la publicidad y la industria cultural. Este nuevo lenguaje apela a la subjetivización, al uso del cuerpo, y otros sistemas diversos de comunicación para eludir la pérdida de significados.

El lenguaje del artivismo implica a menudo el uso del sujeto artista como medio para la disrupción de la abstracción, o para evitar la pérdida de capacidad expresiva, y para recuperar la libertad de expresión individual. Según Kombarov, la total subjetivización y uso del cuerpo y sus capacidades en el espacio, literalmente hace entrar al sujeto en el discurso público vaciado de humanidad, saturado de manipulación imaginaria. En la obra del artivista Pavlensky, la colocación del cuerpo del artista, la presentación del sujeto en el espacio urbano, es un proceso para generar una nueva presencia humana. En ese proceso, la subjetividad del artista se usa como sistema de bifurcación del discurso politico, para hacerlo llegar al receptor: «La estructura de la subjetividad se bifurca: el sujeto se comprende como sujeto sensorial con deseos y necesidades corporales, y por otra parte, el sujeto que desea se encuentra a sí mismo en el discurso, denotando su nivel biológico a través del simbólico» (Kombarov, 2017: 4).

Este lenguaje permite usar cuerpos u objetos (Barbosa-de-Oliveira, 2007), como cauce sensorial, para transmitir experiencias intelectuales que se materializan con fuerza: recrean un espacio, un objeto, un sujeto. Esos procesos vinculan a los receptores con el artista de maneras nuevas (Kombarov, 2017: 5). Como recoge este autor, la verdad, en el proceso de pérdida progresiva de capacidad representacional implicada en la sociedad de masas y en la masificación comunicativa, no aparece ya apenas, sino como un suceso. Los artivistas generan sucesos porque rompen la estructura de capas de la comunicación convencional irrumpiendo en el espacio social para atraer la atención e inocular pensamiento en sus receptores. Lo hacen mediante la «emocionalización», mediante la subjetivización, mediante la ruptura y la invasión de los espacios o mediante la adaptación de los medios y los tiempos no artísticos a la expresión artística.

En esta performance de Pavlensky, el artista ruso se cosió literamente la boca para realizar una sesión de fotografías en la Plaza Roja de Moscú, expresando, no solamente contenido político, sino un lenguaje completamente novedoso. Lo que vemos en este artivista es la refundación del poder del cuerpo para transmitir las ansias de libertad. El acto represor se denuncia aquí con belleza, con integridad y claridad. Como Lethaby (2017), del movimiento Arts and Crafts británico, decía en el siglo XIX, precediendo al artivismo «el arte es humanidad liberada, y todo lo demás es esclavitud».

4. El artivismo como experiencias de autonomía, resistencia o desobediencia

El artivismo es un lenguaje actual de autonomía y libertad. En nuestras actividades investigadoras hemos archivado cientos de experiencias de artivismo en todo el globo. De nuestro archivo destacamos prototipos esenciales para estudiar sus casos. Un ejemplo claro es el caso de Banksy, grafitero, activista político y director de cine de identidad no verificada, quien desarrolla su trabajo desde Reino Unido (Bristol) de manera anónima. El artista define el grafitti como la venganza de la clase baja o guerrilla que permite a un individuo arrebatar el poder, el territorio y la gloria, a un enemigo más grande y mejor equipado. Las obras de Banksy han abordado diversos temas políticos y sociales, incluyendo el antibelicismo, anti-consumismo, o el antifascismo.

Banksy arremete contra diversas reglas del arte convencional. La primera es la autoría del artista y el culto al ego. El anonimato del autor, y el carácter siempre transgresor de sus piezas, que aparecen en superficies y espacios de todo tipo y en todo el mundo, acaba con la convención del arte en museos y lugares de culto. Con ese poder comunicativo atrae la atención sobre realidades y situaciones, como ha hecho recientemente en territorios de frontera de Israel/Palestina. Además, cumple el requisito de arte efímero, que es borrado o eliminado en muchas partes. Y está completamente fuera del mercado.

Especialmente interesante es el caso de China donde bajo una aparente tranquilidad, se han ido desarrollando formas de protesta artivista de gran alcance. Una de las más célebres es el artivista chino Ai Wei Wei. Un caso excepcionalmente importante es el del artivista Wang-Zi. En su condición de homosexual, algo considerado delito en su país, ha recurrido al arte popular de los recortes de papel que constituyen un recuerdo cultural colectivo, para representar la vida y las emociones del individuo homosexual. Wang-Zi ha ido incorporando nuevas formas de expresión artística a su repertorio.

En España, la crisis económica de los últimos años, se ha convertido en verdadera incubadora para el artivismo. Luzinterruptus, grupo colaborativo y anónimo creado en 2008 que trabaja en grandes ciudades como Madrid y Berlín, se caracteriza por realizar intervenciones en el espacio público utilizando la luz como materia prima. En 2014 llevaron a cabo en Madrid su acción-denuncia. La policía está presente, un rechazo a la conocida popularmente como Ley Mordaza en referencia a la Ley Orgánica de Protección de la Seguridad Ciudadana, aprobada por el Partido Popular en julio de 2015.

Los artivistas de este grupo trabajan con el fluido luminoso y sus soportes. Realizan intervenciones siempre asociadas a este elemento. En este caso, para protestar por la presencia de policía en las calles, generaron un trampantojo visual con cajas iluminadas sobre los automóviles. El juego, sorpresa y creación nos hacen visualizar la idea de los artistas. Como indican Clark y Kallman (2011), en un espacio público cada vez más alienado, estas intervenciones recuperando la voz artística lo acercan nuevamente al «civitas», al «espacio de ciudadanía democrática activa».

Un ejemplo español similar es el del colectivo Basurama, fundado en 2001, que constituye un ejemplo de prácticas de creatividad activista que ha centrado su área de estudio y actuación en los procesos productivos, y la generación de desechos que estos implican. Su proyecto «Agostamiento» fue una intervención «site-specific» dentro del programa «Abierto x Obras» que tiene lugar en la antigua cámara frigorífica del Matadero en Madrid. El colectivo propuso un paisaje interior extraído de la plantación de 7.000 girasoles que había cultivado junto a los vecinos y vecinas de la Gran Vía del Sureste, en el Ensanche de Vallecas, un barrio símbolo de la burbuja inmobiliaria. Su creación, en palabras de Basurama, «invita a charlar y a comer pipas, mirando hacia el futuro desde lo más oscuro». Este proyecto fue realizado en Madrid en 2016.

El redescubrimiento del espacio público o del mundo compartido permite a los artivistas iluminar la vida social. Con ello los artivistas consiguen «una reconfiguración espacial de lo perceptible y lo pensable, como garante de un nuevo territorio de lo posible» (Segura-Cabañero & Simó-Mulet, 2017). Obtenidos ejemplos sobresalientes y archivados en nuestro análisis, procedemos a explicar los vínculos en contextos educativos del artivismo a los que hemos podido tener acceso.

5. Funciones educativas. Los talleres de artivismo

Una vez conocidos los prototipos, desarrollamos experiencias en talleres de artivismo con jóvenes. Tras varias semanas de trabajo con artivistas y jóvenes universitarios, el artivismo resulta ser, además de un lenguaje y una forma de comunicar y expresar autonomía, disidencia y oposición, una forma educativa fundamental. Si, como sabemos, la revolución del siglo XXI es sobre todo una revolución educativa, en la que las comunidades de aprendizaje obtienen su formación a partir de rupturas de los límites en las aulas, en búsqueda de nuevas identidades, nuevas formas de entender los significados y utilizando nuevos roles educativos (Wenger, 1998; Aparicio-Guadas, 2004) el artivismo nos ofrece un cauce nuevo para la comunicación educativa.

Efectivamente la educación en crisis desde hace una década debe abandonar las rémoras que se señalan, desde el mundo de los investigadores (Aguaded, 2005), la ausencia de libertad, el «escrituro-centrismo», el dominio de los saberes teóricos y de las posiciones pasivas y receptoras en los estudiantes, o la rigidez en las posiciones y roles académicos (Aguaded, 2005: 30). En su lugar, se imponen, en la educomunicación del siglo XXI ya hacia su mitad, los enfoques de la educación planteada por autores como Paulo Freire y Mario Kaplún, en que no solamente comunicación y educación son vistas en íntima relación, sino con una finalidad libertadora, de educación cívica global (Middaugh & Kahne, 2013; Pegurer-Caprino & Martinez-Cerdá, 2016). En los procesos en los que la educomunicación avanza hacia constituir un elemento libertador y generador de comunidades activas y capaces de empoderarse, el artivismo puede aportar todos los elementos necesarios para resemantizar la enseñanza y alejar la formación del mercantilismo o la excesiva reificación de la cultura.

Tal y como De-Gonzalo y Pérez-Prieto, que colaboraron con nosotros en los talleres como artistas guía, recogen en su obra «La intención» (2008), estas son algunas de las funciones normales educativas del artivismo que son resultados de esta parte de nuestro trabajo:

1) El artivismo integra al individuo en la construcción simbólica de la realidad, alejándolo de las posiciones pasivas a las que la comunicación global, las tecnologías digitales o la publicidad y el adoctrinamiento político le conducen. El artivismo es intervención social inmediata. Participación, y despertar activo. La cultura es fundamentalmente experiencia (La intención, 2008). Y del arte interesan sobremanera aquellos fenómenos que generan lo que estos autores denominan «cadenas generativas» (2008). Esas cadenas generativas se producen efectivamente en los talleres con jóvenes, continuando en ellos el impulso hacia la conservación y generación de la cultura, es decir, la verdadera educación.

2) El artivismo genera en las personas lenguajes para expresarse, convirtiéndose en emisores, y no solo receptores de mensajes. El carácter fabricado, construido, artesano de las intervenciones artivistas enseña cómo proceder a intervenir, alejándonos de las formas ideales del arte y del borrado de su incidencia en la vida cotidiana.

3) La cultura es un alimento necesario para la socialización humana. Con ella el individuo se libera de las visiones competitivas, pasivas, mercantilizadas de la vida, adoptando una visión lúdica, hedonista, compartida o generosa de la vida. El artivismo es una alfabetizadora ética social, que lleva a una «autonomía no individualista» de la persona (2008). En el mundo del arte, se transciende la simple idea política de la búsqueda de la igualdad, a favor de una idea no de unificación igualitaria, sino de expansión creativa similar de lo diverso, en una igualdad cualitativa y atributiva.

4) El artivismo garantiza, por último, la integración del individuo en una construcción de los espacios y contextos colectivos, que es a la vez individual y marcada por la personalidad creadora de cada humano en su distinta capacidad. El arte y la creación tienen huellas personales, y al mismo tiempo, son contribuciones colectivas y colaborativas. Es de nuevo una función trascendente al dilema individualismo/socialidad de las formas no artísticas de concebir la vida social.

La alfabetización artística tiene que ver con la capacidad del arte para refundar y canalizar la expresión humana. Como indica Abarca (2016: 8), «una obra de arte urbano permite al espectador medir la dimensión física del entorno proyectando su propia dimensión física sobre este». Los ambientes creativos generados en el artivismo humanizan los espacios (Garnier, 2012) e involucran a los jóvenes, como podemos ver en los talleres que hemos organizado. La creatividad se expande en red en los jóvenes (Hernandez-Merayo, Robles, & Martínez, 2013). Este arte recupera su función educativa porque da a los jóvenes un rol activo y participativo.

La alfabetización sociopolítica del artivismo trabaja en niveles profundos de la experiencia humana, más allá de la construcción de los habituales mapas de sentido y universos en los que los medios de comunicación, las instituciones políticas, los poderes económicos y productivos, emiten sus imaginarios rectores (Castoriadis, 1975). El arte puede en este nivel cognitivo profundo instaurar nuevas formas de afrontar la experiencia humana (Toro-Alé, 2004; García-Andújar, 2009). Y lo que apreciamos, cuando desencadena acciones como la construcción de un collage o la pintura de un muro en un jardín urbano, es como ancla cognición y acción directa en un vínculo educativo único. Como reitera Abarca (2016: 9), «el arte urbano es, por tanto, una llamada a la acción, hace al espectador consciente de su propio poder. Nos devuelve al tiempo en que cada persona podía reordenar su entorno tanto como le permitiera el potencial de su cuerpo, antes de que el poder de unos pocos comenzara a determinar los límites de acción de todos los demás. Evoca esa realidad inherentemente humana, de cuya represión ha surgido el alienante entorno en que vivimos».

El proceso de convertir el artivismo en una forma de alfabetización social tiene múltiples resultantes beneficiosas. Se trata de una serie de resultados de nuestra actividad investigadora que deseamos resaltar aquí, obtenidos de la directa participación de los jóvenes en nuestros talleres de artivismo:

• Conecta directamente con la necesidad de integración práctica y de participación de los jóvenes condenados hoy en día a papeles pasivos, y rechazados por el mundo profesional.

• Rescata las funciones normales del arte hacia su desmercantilización y recuperación de un carácter espontáneo y no especulativo.

• Rompe las barreras académicas y profesionales sobre quién puede o no puede intervenir, invierte los roles tradicionales de la expresión cultural.

• Resignifica espacios urbanos degradados o sin personalidad.

• Actúa en el nivel de las cogniciones fundamentales del entorno en que vivimos. Deshace la tendencia a la psicologización e imaginarización de la vida social, alentada por el auge de los medios digitales, indicando la dimensión material inmediata de la existencia humana.

• Conecta la vida de los jóvenes con aspectos materiales y pragmáticos que los corresponsabilizan de la estructura social y del contexto urbano. Invita a intervenir en sus ambientes creativos y contagia a los jóvenes el espíritu rupturista y liberador que acompaña siempre a las iniciativas dinámicas de acción social. Estos resultados derivan de las experiencias concretas de artistas, estudiantes e investigadores en el entorno del artivismo. En contextos educativos relacionados con la participación ciudadana, la acción social y el desarrollo de la comunicación el artivismo libera una capacidad y energia completamente novedosas.

6. Conclusiones

Nuestro estudio establece conceptos, descripciones lingüísticas y funciones culturales y educativas del artivismo, con ejemplos a escala global, y explora su potencial como nuevo lenguaje formativo. El desarrollo de análisis, de archivo y de experiencias en talleres, nos ha permitido justificar la importancia del fenómeno artivista en contextos reales de educación y vida social.

Como Lippard (1984) observa, el artivismo tiende a ver el arte como un diálogo mutuamente estimulante, y no una lección especializada o una ideología impartida desde arriba. Su dinamismo, su expresividad, la estructura rupturista de su lenguaje, lo convierte en un arte para los no artistas, en un instrumento de creación para los no creativos, y por ello, en la vía idónea de cambio y evolución social. Es una nueva forma de libertad.

Según Valdivieso (2014: 20), la atención que vienen prestando últimamente los «canales oficiales» del mundo del arte al artivismo conlleva un peligro: la instrumentalización de los movimientos de protesta, desde el sistema del arte, y la reducción de estos a meras expresiones artísticas, neutralizando y estetizando así sus intenciones políticas y sociales a través de su «musealización».

Pero el artivismo se aleja del arte estético puro y se acerca a la expresión no artística, a los entornos y medios no artísticos, como dice Mullin (2017). Dialoga con el amateurismo, con el espíritu híbrido y heterodoxo. Introduce la ruptura, lo carnavalesco, la burla, en los canónicos estilos tradicionales. Todo ello lo lleva a reintegrar el arte en el medio social, y a reinsuflar con imaginación y vida el medio artístico tradicional, al mismo tiempo que se pone al servicio de las necesidades educativas, hoy vitales.

Apoyos

Esta investigación se realiza y difunde con la ayuda del Proyecto Europeo 2016-1-FR02-KA205-011291 «Artivism: Artistic practices for social transformation», Programme Erasmus+ Key Action 2 «Strategic Partnership».

Referencias

Abarca, J. (2006). Del arte urbano a los murales. ¿Qué hemos perdido. In P. Soares-Neves (Ed.), Street art & urban creativity scientific journal, 2, 2. Lisboa. www.urbanario.es

Abarca, J. (2009). Qué es en realidad el arte urbano. Tribuna Complutense 88, Madrid, 2009-05-26.

Abarca, J. (2010). El papel de los medios en el desarrollo del arte urbano. Revista de la Asociación

Abarca, J. (2017). Breve introducción al grafitti. [blog]. https://bit.ly/2rB6iLe

Aguaded, I. (2005). Strategies of edu-communication in audiovisual society. [Estrategias de edu-comunicación en la sociedad audiovisual]. Comunicar, 23, 25-34. https://bit.ly/2rHA1Ci

Aladro, E. (2017). El lenguaje digital, una gramática generativa. CIC, 22, 136-151. https://doi.org/10.5209/CIYC.55968

Aladro, E. (2018). Los mapas, la vida digital y los mundos que descibrimos. Telos. https://bit.ly/2Is0oWv

Andreotti, L., & Costa, X. (1996). Situacionistas: Arte, política, urbanismo. Barcelona: Museu d’Art Contemporani.

Aparicio-Guadas, P. (2004). The resorts in the creativity and emancipation development. [Recursos en el desarrollo de la creatividad y la emancipación]. Comunicar, 23, 143-149.

Appadurai, A. (2001). La Modernidad desbordada. Dimensiones culturales de la globalización. México: FCE.

Aragonesa de Críticos de Arte, 12, septiembre de 2010.

Ardenne, P. (2008). Un arte contextual. Murcia: Cendeac.

Augé, M. (2009). Los no lugares. Espacios en el anonimato. Antropología de la modernidad. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Barbosa-De-Oliveira, L.M. (2007). Corpos indisciplinados. Ação cultural em tempos de biopolítica. São Paulo: Beca.

Bauman, Z. (2007). Arte, ¿líquido? Madrid: Sequitur.

Bourriaud, N. (2006). Arte relacional. Buenos Aires: Adriana Gil Editora.

Bourriaud, N. (2008). Topocrítica. El arte contemporáneo y la investigación geográfica. In M.A. Hernández-Navarro (Ed.), Heterocronías, tiempo, arte y arqueología. Murcia: Cendeac.

Campbell, J. (1992). Las máscaras de dios. Vol III: Mitología creativa. Madrid: Alianza.

Carpiano, R.M. (2009). Come take a walk with me: The ‘go-along’ interview as a novel method for studying the implications of place for health and well-being. Health & Place, 15, 263-272.

Castoriadis, C. (1975). La institución imaginaria de la sociedad. Barcelona: Tusquets.

Clark, A., & Emmel, N. (2008). Walking interviews: More than walking and talking. Presented at ‘Peripatetic Practice: A workshop on walking’. London, March 2008.

Clark, T.N., & Kallman, M. (2011).The global transformation of organized groups: New roles for community service organizations, non-profits, and the new political culture. Beijing: Ministry of Civil Affairs.

Coomaraswamy, A. (1996). La transformación de la naturaleza en arte. Barcelona: Kairós.

Dayan, D. (1998). La historia en directo. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili.

De-Gonzalo, M., & Pérez-Prieto, P. (2008). La Intención. Un proyecto de Marta De-Gonzalo y Publio Pérez-Prieto sobre Educación y para una Alfabetización Audiovisual. Madrid: Entreascuas.

De-Soto, P. (2012). Los mapas del #15M: El arte de la cartografía de la multitud conectada en redes, movimientos y tecnopolítica. Barcelona: Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, Internet Interdisciplinary Institute.

Expósito, M. (2013). La potencia de la cooperación. Diez tesis sobre el arte politizado en la nueva onda global de movimientos. Barcelona: MACBA. https://bit.ly/2rAHSRU

Fernández-De-Rota, A. (2013). El acontecimiento democrático. Humor, estrategia y estética de la indignación. Revista de Antropología Experimental, 13, 1-25. https://bit.ly/2Ik3nkr

Frúgoli, J., & al., (Eds.) (2006). As cidades e seus agentes: Prácticas e representações. Belo Horizonte: Pucminas / Universidade da São Paulo.

García-Andújar, D. (2009). Reflexiones de cambio desde la práctica artística. In J. Carrión, & L. Sandoval (Eds.), Infraestructuras emergentes. Valencia: Barra Diagonal, pp. 100-103.

Garnier, J.P. (2012). De la réappropiation de l'espace public au développement urbain durable: Des mythes aux réalités, en Alternatives non-violentes 165 (octubre), 8-13. https://bit.ly/2rOBK91

Gianetti, C. (2004). Agente interno. El papel del artista en la sociedad de la información. Inventario, 10, 1-5. Madrid: AVAM. https://bit.ly/2jWCuo1

Hernández-Merayo, E., Robles-Vilchez, C., & Martínez-Rodríguez, J.B. (2013). Interactive youth and civic cultures: The educational, mediatic and political meaning of the 15M. [Jóvenes interactivos y culturas cívicas: sentido educativo, mediático y político del 15M]. Comunicar, 40, 54-61. https://doi.org/10.3916/C40-2013-02-06

Hodge, S. (2016). 50 cosas que hay que saber sobre arte. Barcelona: Ariel.

Kombarov, V. (2017). Alone voice onstage at Russianmedia : Subjectivation through bodily symbolism as avant-garde political discourse (Pavlensky Case). Presented at ESA Congress, Athens, August 2017.

Lethaby, W.R. (2017). Catálogo de la Exposición «William Morris y Compañía: El movimiento Arts and Crafts británico». Madrid: Fundación Juan March.

Lippard L. (1984). Trojan horses, activist art and power en VVAA (1984): Art after Modernism. Rethinking representation. New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art.

Manovich, L. (2005). El lenguaje de los nuevos medios de comunicación. Barcelona: Paidós,

Maslow, A. (1998). La personalidad creadora. Barcelona: Kairós.

Middaught, E., & Kahne, J. (2013). New media as a tool for civic learning. [Nuevos medios como herramienta para el aprendizaje cívico]. Comunicar, 40, 99-108. https://doi.org/10.3916/C40-2013-02-10

Mullin, A. (2017). Feminist art and the political imagination. https://bit.ly/2I7sKps

Pegurer-Caprino, M., & Martinez-Cerdá, J.F., (2016). Media literacy in Brazil: Experiences and models in non-formal education. [Alfabetización mediática en Brasil: experiencias y modelos en educación no formal]. Comunicar, 49, 39-48. https://doi.org/10.3916/C49-2016-04

Pink, S. (2007). Walking with video. Visual Studies, 22, 240-252. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725860701657142

Ramírez-Blanco, J. (2014). Utopías artísticas de revuelta. Madrid: Cátedra, Cuadernos Arte.

Riemchneider, B., & Grosenick, U. (1999). Art at the end of the Millenium. Köln: Taschen.

Sánchez-Ferlosio, R. (2000). El alma y la vergüenza. Madrid: Destino.

Segura-Cabañero, J., & Simó-Mulet, T. (2017). Espacialidades desbordadas, en Arte, Individuo y Sociedad, 29, 219-234. https://bit.ly/2GgBFPN

Sheikh S. (2009). Positively trojan horses revisited journal #09. New York: e-flux. https://bit.ly/2IBuUgI

Simmel, G. (2002). Las grandes ciudades y la vida del espíritu. Madrid: Taurus.

Szmulewicz R.I. (2012). Fuera del cubo blanco. Lecturas sobre arte público contemporáneo. Santiago de Chile: Metales Pesados.

Toro-Alé, J.M. (2004). Crea-ti-vity, body and communication. [Crea-ti-vida-d, cuerpo y comunicación]. Comunicar, 23, 151-159. https://bit.ly/2Nf4dOi

Valdivieso, M. (2014). La apropiación simbólica del espacio público a través del artivismo. Las movilizaciones en defensa de la sanidad pública en Madrid. Scripta Nova, 18(493), 1-27. https://bit.ly/2IokbCW

Wang, X., Yu, Z., Cinderby, S., & Forrester, J. (2008). Enhancing participation: Experiences of participatory geographic information systems in Shanxi province. China Applied Geography, 28, 96-109. http://10.1016/j.apgeog.2007.07.007

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Document information

Published on 30/09/18

Accepted on 30/09/18

Submitted on 30/09/18

Volume 26, Issue 2, 2018

DOI: 10.3916/C57-2018-01

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?