Abstract

Excessive electricity consumption negatively affects the economic growth of developing countries, and is a major cause of carbon emissions throughout the globe. The objective of this study is to investigate how the use of energy-efficient behavior reminders affects electricity conservation in a New York City Public High School. In this experiment, during the first 10 days, custodians were not reminded to turn off lights. From Day 11-20, reminders were sent to custodians every Monday and Friday to turn off the light. During Days 21-30, reminders were sent every day to remind custodians to turn off the lights. The results showed daily reminders had a significant decrease in electricity consumption compared to when no reminders were sent. Still, there was no significant difference between the percentage of lights being on, making it difficult to confirm if the custodians followed the reminders. The reminder of turning off lights was not a major source of electricity consumption and other factors might have consumed a larger portion of electricity. More schools should be studied to validate the results. Future studies/research can test the effects of energy-saving behavior reminders on electricity conservation from turning off electronic devices, such as smart boards or computers, at the end of the day or analyze custodian behaviors more precisely.

Introduction

1.1 Issues of Electricity Consumption

Electricity contributes greatly to carbon emissions. Carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gasses trap heat in the form of solar radiation within the atmosphere, leading to an increase in the global water temperature and overall global temperature (Raval & Ramanathan, 1989). An increase in global temperature can disrupt the equilibrium of Earth’s ecosystems, leading to adverse effects for both people and animals. For instance, as a result of increasing carbon dioxide levels, oceans have become more acidic. The increased acidity makes the ocean uninhabitable to marine life and upsets the balance of the ocean ecosystems (Cornwall, 2021).

In the U.S., 32% of the overall amount of carbon emissions came from electricity usage (EIA, U., 2020), making it an important factor to consider if the US wants to achieve net zero emissions by 2035 (Anonymous, 2023). It was also found that, in the EU, 20% of all carbon dioxide produced comes from electricity use, also making it important in curbing the carbon emissions in Europe (Eurostat, 2023).

Behavior, habits, and awareness relating to electricity usage play a role in electricity conservation. One study revealed that providing feedback on electricity through a website led to a 15% reduction in electricity use in residential households (Vassileva et al, 2012). Another study found a 13% reduction in electricity usage when a feedback system that allowed office workers to compare electricity use with others was used (Gulbinas & Taylor, 2014). Therefore, it is clear that altering behavior can be an effective strategy to conserve electricity.

1.2 Purpose and hypothesis

The objective of this study is to investigate the effects of energy-efficient behavior reminders on electricity conservation in a New York City Public High School setting. It was hypothesized that energy-saving actions implemented through behavior will reduce electricity consumption in a high school setting when they are implemented daily. Schools, a major source of energy usage, contribute to a large amount of the current carbon dioxide output. This large contribution can be attributed to the fact that 12.5% of New York’s population is made up of students. (Anonymous, 2022) (US Census Bureau, 2023). To reduce energy consumption as well as the resulting carbon output, New York schools must decrease the amount of electricity used. By using a New York public high school as a model, the effectiveness of altering behavior on electricity use can be gauged in a public school setting and could potentially be applied to several public high schools both in and outside of New York.

1.3 Literature Review

There have been several studies that have attempted to reduce electricity usage or develop more environmentally friendly, energy-efficient devices. For instance, it was found that by replacing compact fluorescent lamps (CFL) with light-emitting diodes (LED), a 33-35% reduction in lighting energy expenditure can be seen. A further reduction of 13-15% can be seen if smart LEDs were used instead of LEDs (Moadab et al, 2021). The reduction in electric lighting energy usage can lead to a decrease in carbon emissions. Several studies have also made improvements to heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems (HVAC). One such instance is the use of the Berkley Retrofitted and Inexpensive HVAC Testbed for Energy Efficiency (BRITE) on the Berkeley campus, which adjusts depending on the temperature to prevent a room from overcooling. BRITE was found to be 30-70% more energy efficient compared to two-position control, another way HVAC is controlled (Aswani et al, 2011). Another example can be seen in the development of solar-powered air conditioners. Solar-powered air conditioners rely on solar energy, which does not result in the production of carbon dioxide. In addition, solar-powered air conditioners are more energy efficient than conventional air conditioners, providing an incentive for their use (Zheng et al, 2018). The development of environmentally friendly devices and the illustration that they work demonstrate that there is great potential in reducing the amount of electricity consumed.

While studies testing electricity depletion and behavior have been done, there are few instances where the impact of energy-efficient behavior reminders on electricity consumption was investigated in a high school setting. Several studies have observed how habits such as turning off appliances (G. Kavulya, B. Becerik-Gerber, 2012) or one’s political ideology (Gromet et al., 2013) have influenced electricity conservation, but these were often done in offices or residential buildings and were not explored in a New York City public high school. By investigating this context, the study seeks to fill a critical gap in the research done on electricity consumption in school settings, exploring whether behavior reminders can be effectively tailored and implemented in educational institutions to promote energy conservation. The unique aspect of this study is its focus on the effectiveness of behavior reminders in a high school setting, particularly within a New York City public high school. This focus on a high school environment, which differs significantly from typical study settings, underscores the importance of understanding how energy-saving interventions might need to be adapted for different institutional contexts. Furthermore, the study's use of real-time data collected over days, weeks, or even months provides a more accurate and credible assessment of electricity consumption compared to traditional methods that rely solely on monthly electricity bills.

Methods

2.1 Preparation

Prior to sending any reminders, the number of classrooms and room numbers were recorded onto an Excel spreadsheet before the experiment. This was done to eliminate the process of skipping any classrooms and to keep the data collected as consistent as possible. Additionally, every Sunday an email was sent to our AP Science coordinator to call the custodian's supervisor to relay the messages on specific days (Depending on the experimental group). The timing of the call is completely dependent on the AP Science coordinator. The custodian supervisor will then relay the message to the custodians. The message told to the custodians was not disclosed, but it was hypothesized that they were told to look out for any lights during their shift.

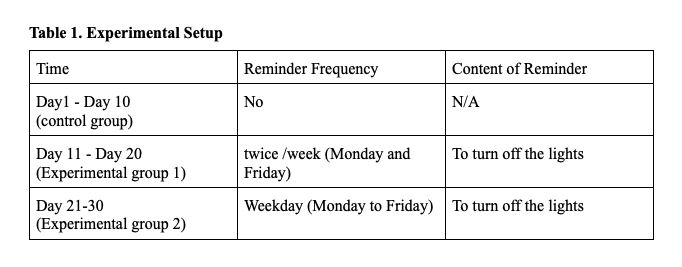

2.2 Experimental Setup From Days 1 to 10 of the experiment, there were no reminders sent to custodians. Following that, from Days 11 to 20, reminders were sent to custodians through direct contact every Friday and Monday. Then, from Days 21-30, reminders were sent to custodians through direct contact every school day. During the beginning of the school day, the amount of classrooms with light and smartboards on were recorded between 7:10 AM and 7:20 AM for 20-30 minutes. Other aspects were not included in this experiment. The control group consisted of no reminders to custodians throughout the whole duration of this experiment. The first experimental group consisted of reminders every Monday and Friday to turn off the lights and smartboards. The second experimental group consisted of reminders every day to custodians to turn off lights and smartboards.

2.3 Measurements/Data Collection

The electricity consumption was accessed from the website “[1]” and recorded onto a 4 GB USB drive. Every Friday, the website was accessed from an office on the first floor of the school. When assessing the website, it was crucial to select the correct school, time, and day of the data being recorded. Specifically, the electricity consumption was recorded in 15-minute increments. After exporting onto the USB drive, it was then taken home and analyzed on Saturday. The data was then analyzed and put into Excel. After the experiment was over, the data was averaged out and compared to other experimental groups by using the line/bar graph function in Excel. Furthermore, the number of lights turned on for each floor of the building was recorded and compiled into an Excel spreadsheet. The data was then averaged out by doing (% of light on) / (total # of lights) and compared with other experimental groups using the bar graph function on Excel.

2.4 Safety

To ensure safety for the participants, when recording data on the number of rooms with either smartboard or light on, they were not allowed to touch anything in the room. A supervisor knew when the participants were performing the experiment in case of any incidents. Additionally, the participants moved carefully throughout the halls when observing classrooms.

2.5 Data Analysis The amount of electricity, in kilowatt-hours, was accessed from the website “http://nuenergen.com” and recorded onto a 4 GB USB drive. The data on the percentage of classrooms and electricity consumption was stored in an Excel spreadsheet. The mean and standard deviation were calculated using the function in Excel. The percentage of lights was calculated by dividing the number of classroom lights by the total number of classrooms. The data was put into a bar graph and the electricity consumption was put into another line graph. It was then compared to see if the impact of setting reminders can reduce electricity consumption. With the data, it was then put into ANOVA to find if there was a significant difference. ANOVA (Analysis of variance) was used on https://astatsa.com/OneWay_Anova_with_TukeyHSD.

Document information

Published on 09/02/26

Submitted on 04/07/24

Volume 8, 2026

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?