Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

This study was carried out on a sample group of 1,238 adolescents from eight different cultural contexts, and aimed to determine the values perceived by subjects in their favorite television characters. It also aimed to identify any possible differences between cultural contexts. The basic hypothesis for the study was that television conveys values and constitutes one of the forces for socialization at play during adolescence. The total sample group was made up by: three Spanish sub-groups, four Latin American sub-groups and one Irish sub-group. The instrument used for exploring perceived values was the Val.Tv 0.2, which is an adaptation of Schwartz’s scale. The data were collected both by means of an on-line platform and in person. In relation to the results, in general, the values most commonly perceived by adolescents are self-management and benevolence. As regards contextual differences, although significant differences were observed in all values, in no case were they particularly notable. The only exceptions were hedonism and achievement, for which no significant differences were found at all between the different contexts. The most relevant differences were found in the values of conformity, tradition, benevolence and universalism. From an educational perspective, we can conclude that the measurement instrument used may constitute an adequate tool for decoding the values perceived by adolescents in their favorite television characters.

1. Introduction

We currently have enough data to enable us to state that adolescents watch television for a wide range of different reasons, such as: to entertain themselves, to learn about life or to identify with their own concerns and interests. In other words, they identify with the contents of television programs, and in turn, as with any other development context, the contents seen on the screen have both a positive and negative effect on adolescent viewers. In general, the media contribute to the development of adolescents’ identity in a reciprocal and multi-directional manner, and teenagers learn different values through media content (Aierbe, Medrano & Martínez de Morentin, 2010; Castells, 2009; Fisherkeller, 1997; Pindado, 2006).

We should not forget that, as a recent study indicates (Fundación Antena 3, 2010), adolescents spend an average of 4 hours a day engaging with different screen-based media, with television accounting for the majority of that time, despite not always being watched on a traditional TV set; and this screen time, as we may call it, affects and influences adolescents’ socialization and value acquisition process (Asamen, Ellis & Berry, 2008).

The analysis of the values conveyed through television has been the object of empirical research for over three decades now. Nevertheless, these values have changed over time, not only internationally, but within our own context also, as demonstrated by a number of recent studies (Bauman, 2003; Bryant & Vorderer, 2006; Del Moral & Villalustre, 2006; Del Río, Álvarez & del Río, 2004; Murray & Muray 2008). In general, a review of previous papers reveals a tendency to find fewer prosocial values and more materialistic values in television contents (Dates, Fears & Stedman, 2008; Méndiz, 2005), although other studies also highlight, for example, the fact that American television tends to convey altruistic behaviors (Smith, Smith, Pieper, Yoo, Ferris, Downs & Bowden, 2006).

However, a more detailed review of published findings regarding the values conveyed by television reveals that the results are disparate and complex. For example, Potter (1990) and Tan, Nelson, Dong & Tan (1997) found that television conveys the conventional values of the American middle class, and other authors such as Raffa (1983) calculated that antisocial values appeared more intensely than positive ones in television contents. However, the results found by other authors (Pasquier, 1996) indicate that television transmits both positive values and negative ones (or counter-values). In this sense, Pinilla, Muñoz, Medina & Acosta (2003) found that Colombian adolescents perceived mainly anti-values such as: jealousy, intrigue, hypocrisy and lack of respect.

Nevertheless, and this is relevant to our study, empirical evidence exists (derived from our previous work) to suggest that television viewers select the contents they watch in accordance with their own values (Medrano, Aierbe & Orejudo, 2010; Medrano & Cortés, 2007).

However, the assessment of the perception of values is a complex undertaking. In this study, we refer to the values perceived by adolescents in their favorite character, not to the values conveyed by the medium itself. In this sense, values are much more difficult to measure than other aspects of development, and moreover, the values of adolescents are particularly unstable, since these individuals are still at a stage in which their system of beliefs has yet to be consolidated. Adolescents exist in a neutral, interim phase, in which they no longer adhere to the beliefs of their previous stage, but have not yet adopted their adult views. This explains the vulnerability of the adolescent phase, and why it is so difficult not only to identify the value perceptions related to teenagers’ favorite characters, but also to work on these perceptions, due to the moment of transition through which subjects are passing. Adolescents have, without a doubt, become an important group to be considered in relation to the media (EDEDA, 2010). They are a strong presence and account for a large percentage of prime time viewers. Consequently, the offer has been expanded and adjusted to suit their tastes, among which we could highlight topics such as love, adventure, paranormal activity and music (Guarinos, 2009).

This study aims to explore the values perceived by adolescents in their favorite character, within the framework of reception theory (Orozco, 2010). Prior research into the perception of values is scarce, which is why this cross-cultural study is, in some ways, a pioneering piece of work in this field.

Despite the empirical difficulties of exploring the perception of values in television, we have based our work on the model developed by Schwartz & Boehnke (2003) and on the 10 dimensions established by these authors for their value scale, both in the 21 item and the 41 item versions. These 10 dimensions can be grouped into four large dimensions. Although this structure has a good degree of conceptual consistency, it also poses verification problems when the usual dimensional reduction techniques (Exploratory or Confirmatory Factorial Analyses) are applied. The technique used by Schwartz himself to demonstrate the consistency of his model is that of multidimensional analysis, which is a purely spatial solution to the circular configuration of this structure.

It is based on the existence of universal aspects of human psychology and interaction systems, which results in some of these compatibilities and conflicts between value types being present in all cultures, thus constituting the articulatory backbones of human value systems. In relation to the theoretical applicability of the model to different cultures, the authors highlight the existence of values which prevail not just in Spanish society, but in different cultures and countries also, such as Germany, Australia, the United States, Finland, Hong Kong and Israel. The differences between different cultures lie in the fact that some attach more importance to individualism, while others tend to prioritize collectivism. Thus, Schwartz’s values provide an empirical and conceptual framework for working in and comparing different cultures (Schwartz, Sagiv & Boehnke, 2000).

From an educational perspective, since our aim is to explore the values perceived by adolescents in television, and moreover, to do so with a cross-cultural sample group, we believe that the model proposed by Schwartz constitutes a valid, rigorous tool for the research being undertaken.

In this sense, insofar as it helps form adolescents’ personal identity, television also fosters the construction of values. The research data currently available in relation to these values are by no means homogenous. Community-type values appear least frequently during this period, although data does exist to indicate that they are in fact present, pointing to the existence of young people concerned about social justice (Jonson & Flanagan, 2000), social engagement (Bendit, 2000) and altruism as a kind of happiness akin to vertical collectivism.

Consequently, the situation in relation to current research and Schwartz’s model can be summed up as follows:

- Television, both in Spain and at an international level, provides contents which include both individualistic and collectivist values.

- Scarce empirical evidence exists regarding the values perceived by viewers in television contents.

- Adolescents tend to perceive their own values in television.

- Schwartz’s model is an adequate tool for exploring the values perceived by adolescents from different cultures in their favorite television character.

- Differences regarding values in different cultures are polarized between individualism and collectivism.

In accordance with the prior review of the literature, this study has a twofold objective:

- to identify the values perceived by a cross-cultural sample group of adolescents in their favorite character, within the framework of Schwartz’s model; and

- to analyze similarities and differences in the values perceived by adolescents in different cultural contexts.

2. Materials and method

This research project is an ex post-facto, descriptive-correlational, cross-cultural study. It explores the values perceived in the characters of the favorite TV programs of a group of adolescents aged between 14 and 19. 44.6% of the sample group were male and 55.4% female.

2.1. Participants

Once all the extreme cases (such as subjects who gave inconsistent responses) had been eliminated from the different cultural contexts, the sample group was distributed as follows:

The total sample group encompassed 1,238 subjects from 8 different cultural contexts; three from Spain, four from Latin America and one from Ireland.

The gender percentage was balanced for all cities. Nevertheless, in San Francisco de Macorís and Rancagua, the percentage of male subjects was 28.1% and 35% respectively. In total, the sample group was comprised by 545 boys and 676 girls. Some cases were lost, since no information was provided regarding this variable.

The sample group was selected on the basis of convenience, in accordance with the following criteria: age, academic year and type of school. Subjects were from the 4th year of secondary school or the 2nd year of the Spanish Baccalaureate (higher education) system, equivalent to the Latin American PREPA and/or Baccalaureate years 1 and 3 and the 3rd year of Junior Certificate and 2nd year of Leaving Certificate in Ireland. As regards type of school or college, the sample group was taken from two or more schools for each sub-sample (city), both state and private, or with different socioeconomic levels (although no extreme cases were included).

The 23 schools and colleges from which the sample group was selected were distributed as follows: Málaga (2 schools, one private and the other state); San Sebastián (2 schools, one state and the other private but with some state funding); Zaragoza (2 schools, one state and the other private); Rancagua (Chile) (2 schools, one state and the other private); Guadalajara (Mexico), (one private middle-class school); Macorís (Dominican Republic) (2 schools, one state and the other private); Oruro (10 state and private schools) and Dublin (2 schools, one state and the other private).

2.2. Variables and measurement instruments

The instrument used to assess the values perceived in the character of subjects’ favorite TV show was the Spanish language version of the PVQ-21 scale by Schwartz (2003), called Val.Tv 0.2. The scale measures the values perceived in subjects’ favorite characters, grouped into 10 basic values: self-direction, stimulation, hedonism, achievement, power, security, conformity, tradition, benevolence and universalism. The scale consists of 21 items, the responses to which are scored on a Likert scale, from one to six.

In order to check the reliability of the instrument, the spatial configuration of these items was verified using the “multidimensional scaling” technique presented by the SPSS, which is very similar to the SSA (Small Space Analysis). The configuration obtained was circular, very similar to that proposed by Schwartz and Boehnke (2003). Nevertheless, one exception should be highlighted: the value “power” was found to have an inadequate spatial configuration.

This spatial configuration, which is similar to that proposed by Schwartz, coupled with the fact that this instrument is comparable to those used in international studies, enables us to calculate the scores for each subscale or dimension. The analysis of the internal consistency of each dimension using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient resulted in reliability indexes of over 0.50 (the maximum was obtained for universalism a=.798 and the minimum for security a=.529), with the exception of the value “power”, which had an a =.389.

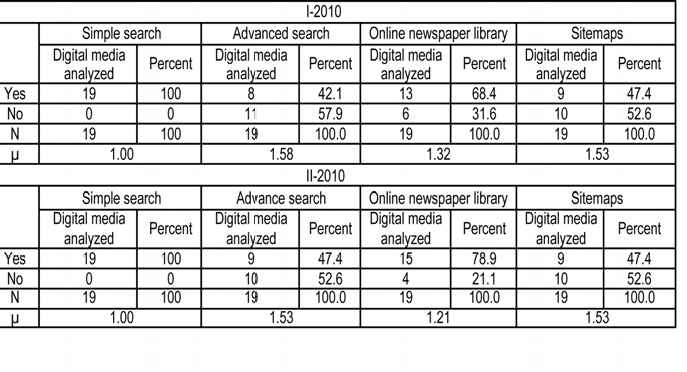

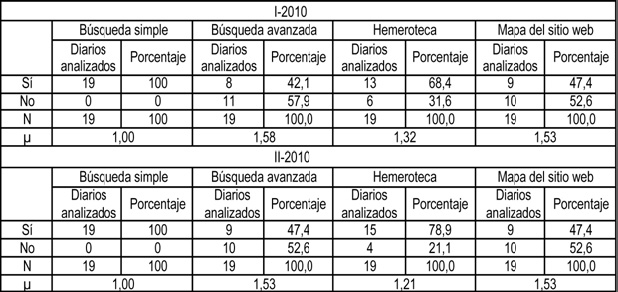

2.3. Procedure

For the data collection process, the first phase consisted of adapting the Val.Tv 0.2 scale from the Spanish version to a Bolivian, Chilean and Mexican version. Also, the original version was translated and adapted to an English version. These adaptations were all carried out without changing the meaning of the values. The scale was revised by eight experts prior to its definitive approval. In addition to other aspects, the experts were asked to assess whether the definitions of the values were applicable to each culture. The majority of participants completed the questionnaires on-line. In the Bolivian and Dominican samples, the data were collected on paper, due to the lack of computer facilities required for this kind of on-line questionnaire. Subsequently, the data gathered on paper were entered into an on-line version, in preparation for their statistical processing.

Between 20 and 30 minutes are required for the application of this scale. In relation to the data analysis, the SPSS program was used and a number of different descriptive and inferential analyses were carried out, mainly the means comparison test and parametric tests (Anova). These not only enabled the identification of the different means, but also verified the significance of these results and the effect size, or in other words, the magnitude of said differences.

3. Results

The analysis of the results focused on the study’s two established objectives. Thus, first of all, the means of the values perceived in subjects’ favorite characters were analyzed for the whole sample group, along with their significance level. This was then followed by an analysis of the differences between the eight sub-sample groups studied in relation to the values perceived in each one.

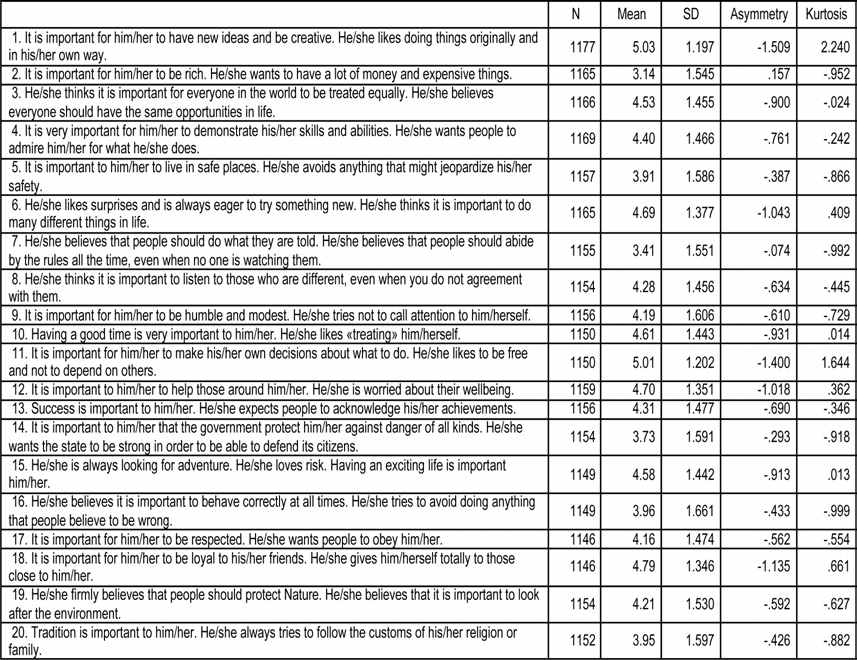

If we focus on the first objective, as shown in Table 2, only some items presented asymmetries higher than 1, and almost none of them were over 1.5. It was therefore considered that these variables were susceptible to processing using parametric tests.

In the first analysis, as shown in Table 2, the highest means were obtained for self-direction (items 1 and 11), with means of 5.03 and 5.01 respectively, followed by benevolence (items 12 and 18), with means of 4.70 and 4.79 respectively. On the other hand, the values with the lowest means were item 2 (power), with a mean of 3.14 and items 7 and 16 (conformity), with means of 3.41 and 3.96, respectively. We believe it is important to highlight the fact that self-direction can be understood as an individualistic value, while benevolence is conceptualized as a collectivist value.

Thus, self-direction is defined as applying to “an active person with independent thought. Also a person who stands out for their creativity, freedom and for choosing their own goals. The value ‘benevolence’, on the other hand, is understood as applying to a person who values the preservation and enhancement of the welfare of people with whom they have frequent personal context; a benevolence person is helpful, honest, indulgent, loyal and responsible.”

Thus, the two values with the highest scores effectively reflect two different dimensions which are not necessarily contradictory, as explained in the conclusions.

However, both the value “power”, which is defined as applying to a person who values social status and prestige, and who seeks to gain control or dominance over people and recourses, and the value “conformity”, which is defined as applying to a person characterized by their restraint of those actions, inclinations and impulses likely to upset or harm others and violate social expectations or norms, obtained the lowest means. The value “power” is also an individualistic value, while “conformity” is collectivist and refers to a person who is excessively conventional or concerned about living up to others’ expectations.

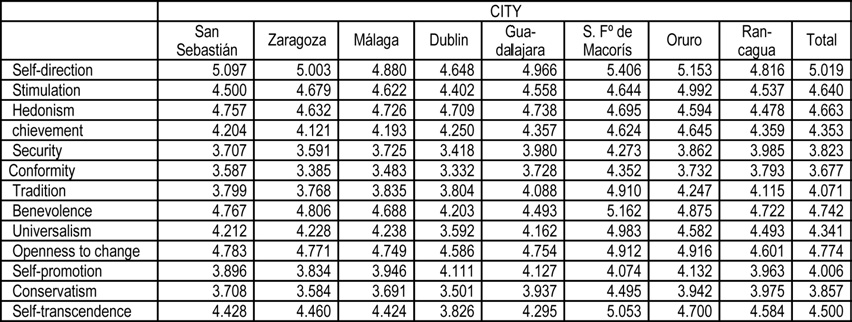

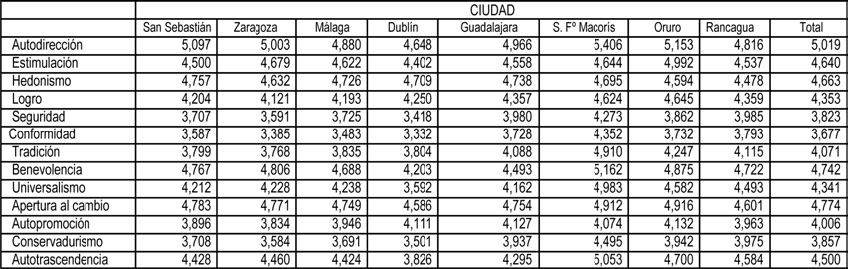

In relation to the second objective, as shown in Table 3, following an analysis of the differences between contexts, in general terms we can state that significant differences were found between the eight cultural contexts studied. Nevertheless, it is important to remember that the value “power” was not included in the calculations, due to its low level of reliability.

On an initial reading, clear differences emerge between the different cities; thus, San Sebastián, followed by Zaragoza, have the highest means (5.097 and 5.003 respectively) in the self-direction dimension.

If we look at benevolence (items 12 and 18), another of the values with the highest scores, San Francisco de Macorís has a mean of 5.162, followed by Oruro with a mean of 4.875. These scores are the highest of all those obtained on a scale where the maximum score was six. We should remember that when we talk about benevolence, we are talking about people who value the preservation and enhancement of the welfare of the people with whom they have frequent personal contact.

However, the lowest values were found for conformity (items 7 and 16). Thus, the mean for Dublin was 3.332 and the mean for Zaragoza 3.385. Conformity is understood as referring to a person characterized by their restraint of those actions, inclinations and impulses likely to upset others. It was important to determine the statistical significance of these differences, and their magnitude. The Anova revealed that all differences were statistically significant (p=.000) except in the dimensions of hedonism F (7.1165=.753; p=.627) and self-promotion F (7.1158=1.834; p=.077).

Nevertheless, when the effect size was analyzed taking these differences globally, they were found not to be great enough to be notable. Having conducted the “eta” coefficient analyses, it can be stated that the differences between the eight contexts studied are hardly relevant at all. The highest results were found for universalism (?2=.073), followed by tradition (?2=.068) and conformity (?2=.042), and the lowest results were found for hedonism (?2=.005), followed by stimulation (?2=.021).

In other words, the greatest differences were found in items 7, 16, 9, 20, 12, 3 and 8, which belong to the values of conformity (which scored very low in all contexts), tradition (with a mean of 3.804 in Dublin and 4.910 in San Francisco de Macorís) and benevolence (with a mean of 4.688 in Málaga and 5.162 in San Francisco de Macorís). In relation to universalism, the mean for Dublin was 3.592, and the mean for San Francisco de Macorís was 4.983.

4. Conclusions

If we carry out a global assessment, taking all the data into account and focusing on the pre-established objectives of the study, we can state that adolescents perceive both individualistic values (self-direction) and collectivist values (benevolence) in their favorite TV character, while the values “power” and “conformity” seem to be perceived less by the sample group on the whole. Cross-cultural differences were found in all values, with the exception of hedonism and achievement. However, these statistically significant differences are not particularly relevant, as shown by the analyses of the results. It is likely that this is due to the size of the sample, since in a detailed analysis of the data, these mean differences are not particularly extreme, and no clear differentiating trends can be detected between the different cultures. In other words, our data do not enable us to state that some cultural contexts are more inclined to perceive individualistic values, while others tend more to perceive collectivist ones.

These results coincide with those of the studies cited in the introduction to this paper (Bendit, 2000; Dates, Fears & Stedman, 2008; Del Río, Álvarez & Del Río, 2004; Méndiz, 2005). As in previous research projects, our results also indicate that television conveys individualistic or presentist values, while at the same time transmitting prosocial values. Nevertheless, it is important to clarify that our data refer only to the values perceived by adolescents.

Prior research concludes that television conveys both individualistic and collectivist values, values which are not only typical of adolescents, but which also constitute one of the characteristics of postmodern society (Castells, 2009; Goldsmith, 2010; Maeso Rubio, 2008). In our research, however, although we define the value self-direction as the achievement of personal goals, we should not necessarily interpret this to imply that self-direction clashes with benevolence. Both values, self-direction and benevolence, enable a person to be competitive and to develop their abilities to the full (achievement), while at the same time being concerned about others. These tendencies are perfectly compatible from the perspective of value development.

Nevertheless, one aspect of our data that does warrant attention is the absence of major contextual differences; this may indicate a globalization of the values conveyed and perceived through television. Although this claim requires further exploration through more qualitative studies using semi-structured interviews with young people from different cultures, the working hypothesis is of enormous interest in our attempt to understand how television may foster socialization and the acquisition of values during adolescence, a phase of particular vulnerability. Could it be that in the global village, the perception of values by adolescents is becoming increasingly similar? An initial reading of our data indicates that this is indeed the case, and moreover, the value “power” and the value “conformity” are those perceived less frequently. Bearing in mind that a relationship exists between our values and the values perceived through television, this would seem to indicate that the adolescents in our study evince little interest in becoming successful, ambitious and/or influential people (power). Furthermore, they perceive those characters they “like best” as fairly unconventional. Bearing in mind the age range of the sample group and that one of the characteristics of adolescence is the transgression of conventional norms, this last result is consistent with the assessment instrument itself.

Do these findings indicate a trend in the values of today’s society? Many authors have already warned of the ambivalence of value transmission; however, the adolescents in our study did not perceive ambivalent values and curiously enough, one of the quintessential individualistic values, power, was found to be one of the least perceived. The fact that values such as conformity, defined as restraint of those actions, inclinations and impulses likely to upset or harm others and violate social expectations or norms, as well as courtesy, obedience, self-discipline and honoring one’s parents and the elderly, scored lowest in our study is extremely interesting, and to some extent contradicts the findings of other research projects. These data are not consistent with the results of other research studies carried out in the American context, which assert that television conveys the conventional values of the middle class (Potter 1990; Tan, Nelson, Dong & Tan 1997).

Before concluding, we would like to highlight some limitations of the study, and to add a comment which goes beyond the scope of the specific results. As regards the limitations, might it not be that the design of the trial itself (a six-point Likert scale with the definition of the values in each item) fosters the social desirability bias? In other words, could it be that respondents give what they consider to be politically correct answers, rather than state what they really feel? Moreover, we should not forget that, in accordance with the reception theory (Orozco, 2010), adolescents do not perceive messages as blank pages, open to any manipulation, but rather interpret them in accordance with their own prejudices, values and ways of thinking, etc.

As regards the comment, we should point out that, in addition to its assessment function, the Scale of Television Value Domains (Val.Tv 0.2) can also be used as an instrument for fostering the explicit expression of the values perceived by adolescents in the characters of their favorite TV shows. Prompting adolescents to explicitly identify and reflect upon values is an important strategy within the psychoeducational field. The instrument presented here may help us translate the implicit messages conveyed by television, share them with others and develop a critical attitude to them. As shown by a number of different authors (Lejarza, 2010; Rajadell, Pujol & Violant, 2005), television may have an enormously constructive effect on the dissemination of values which render learning attractive and which promote the need to make an effort to acquire knowledge. There can be no doubt that teaching about and sharing television is much more effective than restricting or limiting it.

Acknowledgements

This piece of research forms part of a project funded by the Ministry of Education and Science, reference num. EDU2008-00207/EDUC, within the framework of the National Scientific Research and Technological Development and Innovation Plan.

References

Aierbe, A.; Medrano, C. & Martínez de Morentin, J.I. (2010). La privacidad en programas televi-sivos: percepción de los adolescentes. Comunicar, 35; 95-103.

Asamen, J.H.; Ellis, M.L. & Berry, G.L. (2008). Child Development, Multiculturalism, and Media. Londres: Sage.

Bauman, Z. (2003). Comunidad. En busca de seguridad en un mundo hostil. Madrid: Siglo XXI.

Bendit, R. (2000). Adolescencia y participación: una visión panorámica en los países de la Unión Europea. Anuario de Psicología, 31, 2; 33-57.

Bryant, J. & Vorderer, P. (2006). Psychology of Entertainment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawerence Erlbaum Associates.

Castells, M. (2009). Comunicación y poder. Madrid: Alianza.

Dates, J.L.; Fears, l.M. & Stedman, J. (2008). An Evaluation of Effects of Movies on Adolescent Viewers, en Asamen, J.H.; Ellis, M.L & Berry, G.L. (Eds.) Child Development, Multiculturalism, and Media. London: Sage; 261-277.

Del Moral, M.E. & Villalustre, L. (2006). Valores televisivos versus valores educativos: modelos cuestionables para el aprendizaje social. Comunicación y Pedagogía: Nuevas tecnologías y recursos didácticos, 214; 35-40.

Del Río, P.; Álvarez, A. & Del Río, M. (2004). Pigmalión. Informe sobre el impacto de la televisión en la infancia. Madrid: Fundación Infancia y Aprendizaje.

Entidad de Gestión de los Derechos de los Productores Audiovisuales EGEDA (2010). Panorama audiovisual, 2010. Madrid: EGEDA.

Fisherkeller, J. (1997). Everyday Learning about Identities Among Young Adolescents in Television Culture. Anthropology and Education Quaterly, 28, 4; 467-492.

Fundación Antena 3 (2010). En busca del éxito educativo: realidades y soluciones. Madrid: Fun-daciones Antena 3.

Goldsmith, S. (2010). The Power of Social Innovation. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Guarinos, V. (2009). Fenómenos televisivos ‘teenagers’: Prototipias adolescentes en series vistas en España. Comunicar, 33; 203-211.

Jonson, B. & Flanagan, C. (2000). Les idées des jeunes sur la justice distributive, les droits et les obligations: étude transculturelle. Revue International des Sciencies Sociales, 164; 223-236.

Lejarza, M. (2010). Desde los medios de comunicación: Enseñar y compartir la televisión, en Maeso Rubio, F. (Ed.). La TV y la educación en valores. Comunicar 31; 417-437.

Medrano, C. & Cortés, A. (2007). Teaching and Learning of Values through Television. Review International of Education, 53, 1; 5-21.

Medrano, C., Aierbe, A. & Orejudo, S. (2010). Television Viewing Profile and Values: Implications for Moral Education. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 15, 1; 57-76.

Méndiz, A. (2005). La juventud en la publicidad. Revista de Estudios de Juventud, 68; 104-115.

Murray, J.P. & Murray, A.D. (2008). Television: Uses and Effects, en Haith, M.M. & Benson, J. B. (Eds.). Encyclopedia of Infant and Early Childhood Development. NY: Academic Press; 309-318.

Orozco, G. (2010). Niños, maestros y pantallas. Televisión, audiencias y educación. Guadalajara (México): Ediciones de la Noche.

Pasquier, D. (1996). Teen Series Reception: Television, Adolescent and Culture of Feelings. Child-hood: A Global Journal of Child Research, 3, 3; 351-373.

Pindado, J. (2006). Los medios de comunicación y la construcción de la identidad adolescente. Zez, 21; 11-22.

Pinilla, E.R.; Muñoz, L.R. & al. (2003). Reality Show en Colombia: sobre la construcción social de valores. Bogotá: Comisión Nacional de Televisión CNTV.

Potter, W.J. (1990). Adolescents´perceptions of the Primary Values of Televisión Programming. Journalism Quarterly, 67; 843-853.

Raffa, J.B. (1983). Televisión: The Newest Moral Educator? Phi Delta Kappan, 65, 3; 214-215.

Rajadell, N.; Pujol, M.A. & Violant, V. (2005). Los dibujos animados como recurso de transmisión de valores educativos y culturales. Comunicar, 25.

Schwartz, S.H. & Boehnke, K. (2003). Evaluating the Structure of Human Values with Confirma-tory Factor Analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 38; 230-255.

Schwartz, S.H.; Sagiv, L. & Boehnke, K. (2000). Worries and Values. Journal of Personality, 68; 309-346.

Smith, S.W.; Smith, S.L. & al. (2006). Altruism on American Television: Examining the Amount of, and Context Surronding. Acts of Helping and Sharing. Journal of Comunication, 56, 4; 707-727.

Tan, A.; Nelson, L.; Dong, Q. & Tan, G. (1997). Value Acceptance in Adolescent Socialization: A Test of a Cognitive-functional Theory of Television Effects. Communication Monographs, 64; 82-97.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El objetivo general de este trabajo fue conocer los valores percibidos en su personaje favorito de televisión en una muestra de 1.238 adolescentes pertenecientes a ocho contextos culturales y establecer las posibles diferencias entre dichos contextos. Se parte de la hipótesis básica de que el medio televisivo trasmite valores y es una agente de socialización, entre otros, en la etapa de la adolescencia. La muestra total estuvo constituida por: tres submuestras españolas, cuatro latinoamericanas y una irlandesa. El instrumento utilizado para indagar los valores percibidos ha sido Val.Tv 0.2 que es una adaptación de la escala de Schwartz. La recogida de datos se realizó a través de una plataforma on-line y presencialmente. Respecto a los hallazgos encontrados, tomados globalmente, los valores que más perciben los adolescentes son autodirección y benevolencia. Respecto a las diferencias contextuales los datos nos indican que, a pesar de que existen diferencias significativas en todos los valores, éstas no son muy destacables. Hay que exceptuar los valores de hedonismo y logro, donde no se encontraron diferencias significativas entre los diferentes contextos. Las diferencias más relevantes se hallaron en los valores de conformidad, tradición, benevolencia y universalismo. Desde una perspectiva educativa se concluye que el instrumento de medición utilizado puede ser una herramienta adecuada para decodificar los valores percibidos por los adolescentes en sus personajes preferidos.

1. Introducción

En la actualidad se poseen datos suficientes como para poder afirmar que los adolescentes median con la televisión por razones tan diversas como: entretenimiento, aprendizaje para la vida, o identificación con sus propias inquietudes e intereses. Es decir, pueden identificarse con los contenidos televisivos y, a la vez, éstos les repercuten positiva y negativamente como cualquier otro contexto de crecimiento. Los medios, en general, contribuyen de manera recíproca y multidireccional en el desarrollo de la identidad de los adolescentes y éstos aprenden distintos valores a través de dichos medios (Aierbe, Medrano & Martínez de Morentin, 2010; Castells, 2009; Fisherkeller, 1997; Pindado, 2006).

No olvidemos que, como indica un reciente estudio (Fundación Antena 3, 2010) los adolescentes permanecen una media de 4 horas diarias ante diferentes pantallas, siendo la televisión una de las que presenta mayor permanencia, aunque sea vista en otro soporte; y dicha permanencia tiene sus repercusiones e influencia en su proceso de socialización y adquisición de valores (Asamen, Ellis & Berry, 2008).

El análisis de valores que se trasmiten en el medio televisivo es un objeto de estudio que se ha tratado empíricamente desde hace más de tres décadas. No obstante, estos valores han ido cambiando no sólo internacionalmente sino también en nuestro contexto como lo demuestran distintos trabajos (Bauman, 2003; Bryant & Vorderer, 2006; Del Moral & Villalustre, 2006; Del Río, Álvarez & del Río, 2004; Murray & Muray, 2008). En general, se observa en la revisión de trabajos previos que destacan una tendencia a encontrar en los contenidos televisivos valores menos prosociales versus valores más materialistas (Dates, Fears & Stedman, 2008; Méndiz, 2005), aunque otros trabajos, también, han destacado que por ejemplo, la televisión americana transmite conductas altruistas (Smith, Smith, Pieper, Yoo, Ferris, Downs & Bowden, 2006).

Aunque en una revisión más detallada respecto a los hallazgos de los que disponemos, referidos a los valores que transmite el medio televisivo, los resultados son dispares y complejos. Por ejemplo, Potter (1990) y Tan, Nelson, Dong & Tan (1997) encuentran que la televisión trasmite valores convencionales de la clase media americana y otros autores como Raffa (1983) hallan que los valores antisociales aparecen con más intensidad que los positivos en el medio televisivo. Mientras otros autores y sus hallazgos (Pasquier, 1996) apuntan que la televisión transmite tanto valores positivos como negativos o contravalores. En esta línea, Pinilla, Muñoz, Medina & Acosta, (2003) hallan que los adolescentes colombianos perciben, sobre todo, antivalores tales como: celos, intriga, hipocresía y falta de respeto.

No obstante, y esta afirmación es relevante para nuestro trabajo, sí tenemos evidencia empírica, derivada de nuestros trabajos previos, como para afirmar que los telespectadores seleccionan los contenidos de acuerdo a sus propios valores. (Medrano, Aierbe & Orejudo, 2010; Medrano & Cortés, 2007).

Ahora bien, la evaluación de la percepción de valores es compleja. En este trabajo nos referimos a los valores que perciben los adolescentes en su personaje preferido, no a los valores que el medio transmite. En este sentido, los valores son mucho más difíciles de medir que otros aspectos del desarrollo y, además, hay que añadir la inestabilidad de los valores de los adolescentes, en un momento donde aún no se ha consolidado su sistema de creencias. Los adolescentes se encuentran en un punto neutral donde no se adoptan las posturas de los adultos ni tampoco las de su anterior etapa. Este aspecto explica la vulnerabilidad de dicha etapa y la dificultad para, no solo conocer las percepciones en torno a valores de su personaje preferido, sino también, para trabajarlos dado el momento de transición en el que se encuentran. Lo que no cabe ninguna duda es que los adolescentes se han convertido en un colectivo a considerar en los medios de comunicación (EGEDA, 2010). Estos tienen una fuerte presencia y forman una parte importante de los espectadores del prime time. Por esta misma razón la oferta ha sido ampliada y ajustada a sus gustos de los cuales se destacan temas como el amor, la aventura, la paranormalidad y la música (Guarinos, 2009).

En este trabajo se ha tratado de conocer los valores que los adolescentes perciben en su personaje favorito dentro del marco de la teoría de la recepción (Orozco, 2010). Y si nos referimos a las investigaciones previas sobre percepción de valores la investigación es escasa, por lo que este trabajo transcultural de alguna manera resulta pionero en este ámbito.

A pesar de las dificultades empíricas para indagar en la percepción de los valores en el medio televisivo nos hemos basado en el modelo elaborado Schwartz & Boehnke (2003) y en las 10 dimensiones establecidas por estos autores para su escala de valores tanto en su versión de 21 ítems como en la versión de 41 ítems. Estas 10 dimensiones pueden agruparse en cuatro grandes dimensiones. Dicha estructura tiene consistencia conceptual pero presenta problemas de verificación mediante las técnicas de reducción dimensional habituales: Análisis Factorial Exploratorio o Confirmatorio. La técnica utilizada por el propio Schwartz para mostrar la consistencia de su modelo es el análisis multidimensional que es una solución puramente espacial al encontrar una configuración circular de esta estructura.

Se parte, pues, de la existencia de aspectos universales de la psicología humana y de los sistemas de interacción que hacen que algunas de estas compatibilidades y conflictos entre tipos de valor se encuentren en todas las culturas, y se constituyan en ejes articuladores de los sistemas de valores humanos. Respecto a la aplicabilidad teórica del modelo a diferentes culturas estos autores han puesto de manifiesto la existencia de valores que prevalecen, además de en el contexto español, en diferentes culturas y países como son: Alemania, Australia, Estados Unidos, Finlandia, Hong Kong e Israel. Las diferencias entre las distintas culturas se refieren a que unas ponen el énfasis en el individualismo, frente a otras que lo hacen en el colectivismo. Así, los valores de Schwartz proporcionan una base empírica y conceptual para trabajar en diferentes culturas y, al mismo tiempo, poder compararlas (Schwartz, Sagiv & Boehnke, 2000).

Desde una perspectiva educativa, si nuestro objetivo es conocer los valores que los adolescentes perciben el medio televisivo, y además hacerlo con una muestra transcultural, nos parece que el modelo propuesto por Schwartz es una herramienta válida y rigurosa para la investigación que se presenta.

Es este sentido, el medio televisivo, también a través de la formación de la identidad del adolescente, favorece la construcción de valores. Respecto a estos últimos, los datos de investigación disponibles no son homogéneos. Los valores de tipo comunitario son los que aparecen con menos frecuencia en este periodo, aunque, también, existen datos que indican su existencia y presentan a un joven preocupado por la justicia social (Jonson & Flanagan, 2000), la participación social (Bendit, 2000) o el altruismo como forma de felicidad cercana a un colectivismo vertical.

En consecuencia, respecto al estado de la cuestión y el modelo de Schwartz se puede sintetizar:

- La televisión tanto en el contexto del estado español como en el contexto internacional, ofrece unos contenidos en los que se presentan tanto valores individualistas como valores colectivistas.

- Existe escasa evidencia empírica respecto a los valores percibidos por los telespectadores en el medio televisivo.

- Los adolescentes tienden a percibir en la televisión sus propios valores.

- El modelo de Schwartz es una herramienta adecuada para conocer los valores percibidos por los adolescentes de diferentes culturas en su personaje favorito de televisión.

- Las diferencias acerca de los valores en las distintas culturas se polarizan entre el individualismo y el colectivismo.

De acuerdo a la revisión previa, este trabajo pretende indagar dos objetivos:

- Conocer los valores percibidos por una muestra transcultural de adolescentes en su personaje preferido desde el modelo de Schwartz.

- Analizar las semejanzas y diferencias en los valores percibidos por los adolescentes en los distintos contextos culturales.

2. Material y método

Esta investigación es un estudio ex post-facto, descriptivo-correlacional y transcultural. Estudia los valores percibidos en los personajes de los programas que más les gustan en una muestra de adolescentes con edades comprendidas entre los 14 y 19 años donde el 44,6% son varones y el 55,4% son mujeres.

2.1. Participantes

Una vez depurados tanto los casos extremos como los sujetos que han dado respuestas inconsistentes en los distintos contextos culturales, la muestra se distribuye de la siguiente manera:

Es decir, la muestra total asciende a 1238 sujetos distribuidos en 8 contextos culturales diferentes; tres en el contexto español, cuatro en el contexto latinoamericano y una en el contexto irlandés.

El porcentaje de género está equilibrado en todas las ciudades. Sin embargo, en San Francisco de Macorís y Rancagua el porcentaje de varones es de 28,1% en el primero y de 35%, en el segundo. En total, la muestra está constituida por 545 hombres y 676 mujeres. Algunos casos se han perdido ya que no nos han informado sobre dicha variable.

La muestra se obtuvo por conveniencia teniendo en cuenta los siguientes criterios: edad, curso y tipo de centro. El alumnado corresponde a 4º de la ESO y de 2º de bachillerato o lo que corresponde al contexto latinoamericano a PREPA y/o primer y tercer grado de bachillerato. Respecto al tipo de centro, la aplicación se ha realizado en dos o más centros para cada submuestra (ciudades) bien sean centros públicos y/o privados o centros con diferentes niveles socioeconómicos, que no sean extremos.

Los 23 centros donde se ha recogido la muestra se distribuyen de la siguiente forma: Málaga (2 centros, uno privado y el otro público); San Sebastián (2 centros, uno público y otro privado concertado); Zaragoza (2 centros, uno público y otro privado); Rancagua (Chile) (2 centros, uno público y otro privado); Guadalajara (México), (un único centro privado de clase media); Macorís (República Dominica) (2 centros, uno público y otro privado); Oruro (10 centros públicos y privados) y Dublín (2 centros, uno público y otro privado).

2.2. Variables e instrumentos de medida

El instrumento utilizado para evaluar los valores percibidos en el personaje de su programa favorito, se ha utilizado la escala 21 PVQ de Schwartz (2003), adaptada al castellano, y se denomina Val.Tv 0.2. Ésta mide los valores percibidos en el personaje favorito de los adolescentes agrupados en 10 valores básicos: autodirección, estimulación, hedonismo, logro, poder, seguridad, conformidad, tradición, benevolencia y universalismo. Consta de 21 ítems cuyas respuestas puntúan en una escala de tipo Lickert, con valores de entre uno y seis.

Con el fin de comprobar la fiabilidad del instrumento se procedió a comprobar la configuración espacial de estos ítems mediante la técnica de «escalamiento muldimensional» que presenta el SPSS y que es muy similar al SSA (Small Space Analysis). La configuración que se obtuvo fue circular, muy similar a la propuesta por Schwartz y Boehnke (2003). No obstante, hay que destacar una excepción en el valor «poder» que presenta una configuración espacial inadecuada.

Esta configuración espacial similar a la propuesta por Schwartz y la necesidad de manejar un instrumento comparable a los estudios internacionales nos permiten proceder al cálculo de las puntuaciones de cada subescala o dimensión. El análisis de la consistencia interna de cada dimensión mediante el coeficiente alpha de Cronbach, arroja índices de fiabilidad superiores a 0.50 (el máximo se alcanza en universalismo a=.798 y el mínimo en seguridad a=.529) si se exceptúa el valor poder que tiene un a =.389.

2.3. Procedimiento

Para la recogida de los datos, en una primera fase, se procedió a adecuar la escala Val-Tv 0.2 de la versión española a una versión boliviana, chilena y mexicana. Así mismo, se tradujo y adaptó la versión original a una versión inglesa. Estas adaptaciones se han realizado sin cambiar el sentido de los valores. La escala fue revisada por ocho expertos antes de su elaboración definitiva. Se solicitó a los expertos que, además de otros aspectos, valoraran si las definiciones de los valores eran aplicables a cada cultura. La mayoría de los participantes respondieron a los cuestionarios en la versión on-line. En las muestras bolivianas y dominicanas los datos se recogieron en papel y lápiz por carecer de las instalaciones informáticas que requieren este tipo de cuestionarios on-line. Posteriormente, los datos recogidos en papel se introdujeron en la versión on-line para su posterior tratamiento estadístico.

La aplicación de esta escala dura entre 20 y 30 minutos. Respecto al análisis de datos se ha utilizado el programa SPSS y se han efectuado diversos tipos de análisis descriptivos e inferenciales, principalmente la prueba de comparación de medias y pruebas paramétricas (Anova) que nos han permitido conocer no sólo las diferencias de medias sino, también, comprobar la significatividad de las mismas y el tamaño del efecto, es decir la magnitud de dichas diferencias.

3. Resultados

El análisis de resultados se centra en los dos objetivos planteados. Así, en primer lugar se analizan las medias de los valores percibidos en su personaje favorito en la muestra total y la significatividad de las mismas y, en segundo lugar, se analizan las diferencias culturales de los valores percibidos en las ocho muestras estudiadas.

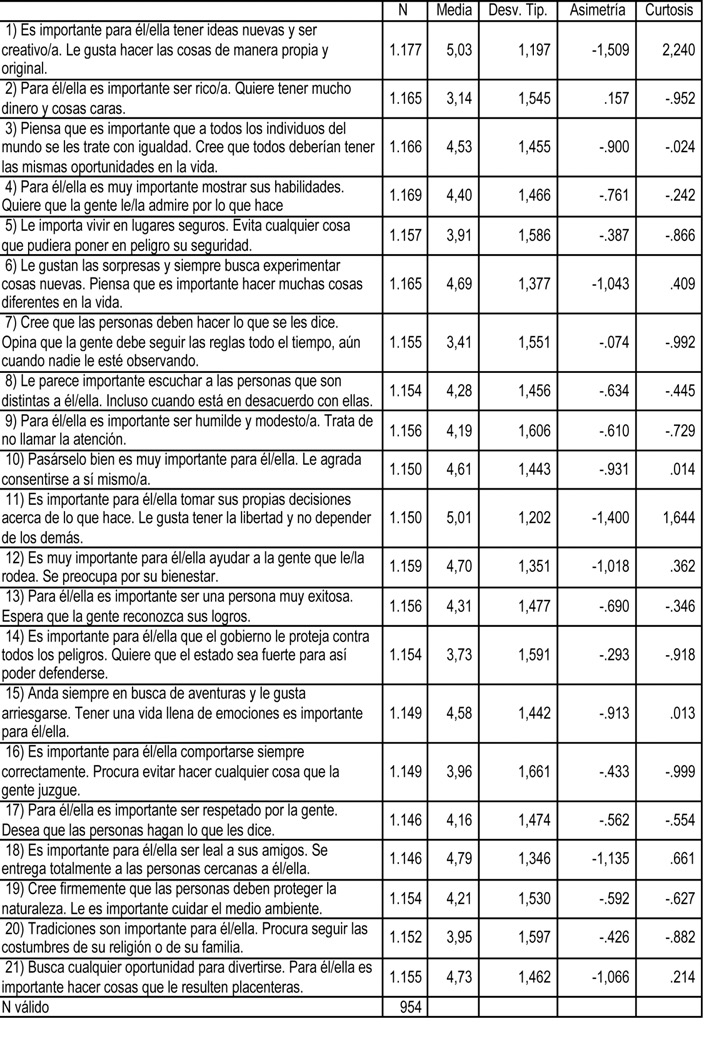

Si nos centramos en el primer objetivo, tal y como se observa Tabla 2 únicamente algunos ítems presentan asimetrías superiores a 1 y prácticamente ninguno superiores a 1,5. Por lo tanto, se ha considerado que estas variables son susceptibles de tratamiento mediante pruebas paramétricas.

En un primer análisis y fijándonos en las medias más altas, como se puede observar en la Tabla 2, se obtienen en el valor de autodirección (ítems, 1 y 11) con una media de 5,03 y 5,01 seguido del valor benevolencia (ítems, 12 y 18) con una media de 4,70 y 4,79 respectivamente. Por el contrario los valores que aparecen con medias más bajas son el ítem 2 (poder) con una media de 3,14 y el ítem 7 y 16 (conformidad) con una media de 3,41 y 3,96 respectivamente. Nos parece importante señalar que el valor autodirección se puede entender como un valor individualista, mientras que el valor benevolencia se conceptualiza como un valor colectivista.

Así el valor autodirección se define como «la persona con un pensamiento independiente y activo. Así mismo se distingue por su creatividad, libertad y elección de sus propias metas, mientras que el valor de benevolencia se entiende como aquella persona que valora la preservación y mejora del bienestar de la gente con la que se está en frecuente contacto personal; persona servicial, honesta, indulgente, leal, responsable».

Ambos valores con las puntuaciones más altas, efectivamente, reflejan dos dimensiones diferentes que no tienen por qué ser contradictorias, como se explicará en las conclusiones.

Sin embargo, tanto el valor poder que se define como la persona que valora el estatus social y el prestigio, así como el control o dominio sobre la gente y los recursos, como el de conformidad que se define como la persona que se caracteriza por su moderación en las acciones, inclinaciones e impulsos que pueden disgustar o herir a otras personas y violar las expectativas o normas sociales, han sido los dos que obtienen las medias más bajas. El valor poder es, también, un valor individualista; mientras que el de conformidad es colectivista y se refiere a una persona excesivamente convencional o preocupada por cumplir las expectativas de los demás.

Respecto al segundo objetivo, tal y como se observa en la Tabla 3, al analizar las diferencias entre los contextos, en términos generales, se puede afirmar que existen diferencias significativas entre los ocho contextos. No obstante, es preciso recordar que el valor de «poder» no ha sido calculado por el bajo nivel de fiabilidad mostrado.

En una primera lectura se detectan diferencias entre las distintas ciudades; así se puede observar que San Sebastián, seguido de Zaragoza, presentan la medias más altas (5,097 y 5,003 respectivamente) en la dimensión de autodirección.

Si nos fijamos en benevolencia (ítem 12 y 18) otro de los valores con puntuaciones más altas, San Francisco de Macorís obtiene una media de 5,162 seguido de Oruro que obtiene una media de 4,875. Estas puntuaciones son las más altas de todas las obtenidas en una escala donde el máximo era seis. Recordemos que al señalar benevolencia se están refiriendo a una persona que valora la preservación y mejora del bienestar de la gente con la que está en frecuente contacto personal.

Sin embargo, los valores más bajos se hallan en el valor conformidad (ítems 7 y 16). Así, Dublín obtiene una media de 3,332 y Zaragoza de 3,385. La conformidad se entiende como la persona que se caracteriza por su moderación en las acciones, inclinaciones e impulsos que puedan disgustar a otras personas. Ahora bien, nos interesa conocer la significación estadística de estas diferencias y su magnitud. Una vez realizada la prueba Anova se puede comprobar que todas son estadísticamente significativas (p=.000) excepto en las dimensiones de hedonismo F (7,1165=.753; p=.627) y autopromoción F (7,1158=1,834; p=.077).

No obstante, al analizar el tamaño del efecto, tomadas globalmente dichas diferencias, no son suficientemente importantes como para ser destacadas. Una vez efectuados los análisis del coeficiente «eta» se puede afirmar que las diferencias entre los ocho contextos estudiados apenas son relevantes. Así las de mayor cuantía se encuentran en universalismo (?2=.073) seguida de tradición (?2=.068) y de conformidad (?2=.042) y las de menor cuantía en hedonismo (?2=.005) seguido de estimulación (?2=.021).

Es decir, las diferencias de mayor cuantía se hallan en los ítems 7, 16, 9, 20, 12, 3, 8 que pertenecen a las valores de conformidad (que ha puntuado muy bajo en todos los contextos); tradición (con una media de 3,804 en Dublín y 4,910 San Francisco de Macorís); benevolencia (con una media de 4,688 en Málaga y 5,162 en San Francisco de Macorís). Respecto al universalismo, encontramos una media de 3,592 en Dublín y de 4,983 en San Francisco de Macorís.

4. Conclusiones

Si hacemos una valoración global, tomados los datos en su conjunto y de acuerdo a los objetivos previos de trabajo, se puede afirmar que los adolescentes perciben en su personaje favorito tanto valores individualistas (autodirección) como valores colectivistas (benevolencia); mientras que el valor de poder y el de conformidad aparecen como los menos percibidos por la totalidad de la muestra. Respecto a las diferencias transculturales, se hallan diferencias en todos los valores, exceptuando los valores de hedonismo y de logro. Ahora bien, estas diferencias que estadísticamente son significativas no son muy relevantes como se ha podido comprobar en los análisis de los resultados. Este hecho puede ser debido, probablemente, al tamaño de la muestra dado que, en un análisis detallado de los datos, estas diferencias de medias no son muy extremas ni se pueden observar tendencias claras que diferencien las distintas culturas. Es decir, nuestros datos no nos permiten hablar de contextos culturales más inclinados a percibir valores individualistas frente a valores colectivistas.

Estos datos coinciden con las investigaciones que se han expuesto en la introducción de este trabajo (Bendit, 2000; Dates, Fears & Stedman, 2008; Del Río, Álvarez & Del Río, 2004; Méndiz, 2005). Es decir, al igual que en la investigación previa se observa que, por un lado, la televisión transmite valores individualistas o presentistas y, al mismo tiempo, vehicula valores prosociales. No obstante, es preciso matizar que nuestros datos se refieren a los valores percibidos por los adolescentes.

La investigación previa concluye que la televisión transmite tanto valores individualistas como colectivistas, propios no sólo del adolescente sino que representan una de las características de las sociedades postmodernas (Castells, 2009; Goldsmith, 2010; Maeso Rubio, 2008). Aunque, en nuestro caso, si definimos el valor autodirección como el logro de metas personales, tampoco deberíamos hacer una interpretación como un valor que esté en contradicción con la benevolencia. Ambos valores, autodirección y benevolencia, permiten a la persona, por un lado ser competitiva o desarrollar sus capacidades al máximo (logro) y, por otro lado, preocuparse por los demás. Estas tendencias son perfectamente compatibles desde el punto de vista del desarrollo de valores.

No obstante, el aspecto que sí llama la atención en nuestros datos es la ausencia de diferencias contextuales importantes que podría estar apuntando hacia una globalización de los valores que se transmiten y se perciben en el medio televisivo. Aunque esta afirmación exige una profundización a través de estudios más cualitativos con entrevistas semiestructuradas a jóvenes de diferentes culturas, la hipótesis de trabajo tiene gran interés para la comprensión de cómo el medio televisivo puede favorecer la socialización y adquisición de valores en una etapa tan vulnerable como la adolescencia. ¿Podríamos afirmar que en la aldea global la percepción de valores por parte de los adolescentes se homogeneiza? Nuestros datos, en una primera lectura, nos indican que esto sí está ocurriendo y, además, tanto el valor de poder como el de conformidad son los menos percibidos. Esto indicaría, si tenemos en cuenta que hay una relación entre nuestros valores y los valores percibidos en el medio televisivo, que los adolescentes de nuestro estudio muestran poco interés por ser personas exitosas, ambiciosas y/o influyentes (poder). Así mismo, perciben a los personajes que «mejor les caen» como personas poco convencionales. Teniendo en cuenta las edades de la muestra y que una de las características de la adolescencia es la transgresión de las normas convencionales, este último dato ofrece consistencia al propio instrumento de evaluación.

¿Están reflejando estos hallazgos una tendencia en los valores de la sociedad actual? Realmente, son muchos los autores que ya nos han alertado de la ambivalencia en la transmisión de valores; sin embargo, en nuestro trabajo los adolescentes no perciben valores ambivalentes y curiosamente un valor individualista por excelencia, el valor poder, es uno de los menos percibidos. Resulta de gran interés y, en parte, contradice algunas investigaciones, el hecho de que los adolescentes perciban en último lugar valores como conformismo que se define como la moderación de las acciones, inclinaciones e impulsos que pueden disgustar o herir a otras personas y violar las expectativas o normas sociales y también como cortesía, persona obediente, autodisciplinada, honrar a padres, madres y personas ancianas. Estos datos no son congruentes con las investigaciones realizadas en el contexto americano donde se afirma que el medio transmite valores convencionales de la clase media (Potter 1990; Tan, Nelson, Dong & Tan, 1997).

Antes de concluir señalar alguna limitación y alguna aportación más allá de los propios datos. En cuanto a la limitación del trabajo ¿no podría ocurrir que el diseño de la propia prueba (una escala Likert de seis puntos con la definición de los valores en cada uno de los ítems) les favorezca el efecto de la deseabilidad social? Es decir, que respondan más de acuerdo a lo políticamente correcto que a lo que realmente piensan. Además, no debemos olvidar que, de acuerdo con la teoría de la recepción (Orozco, 2010), los adolescentes no perciben los mensajes como pizarras en blanco susceptibles de cualquier manipulación sino que los interpretan a partir de sus prejuicios, valores, maneras de pensar, etc.

Respecto a la aportación, hay que señalar que la Escala de Dominios de Valores televisivos (Val-Tv 0.2) además de su función evaluadora, se puede utilizar como un instrumento para favorecer la explicitación de los valores que los adolescentes perciben en los personajes de sus programas preferidos. La explicitación y reflexión acerca de los valores es una estrategia muy relevante desde el punto de vista psicoeducativo. El instrumento que se presenta puede ayudarnos a traducir los mensajes implícitos transmitidos por el medio, compartirlos con los demás y desarrollar una actitud crítica. La televisión puede tener, como señalan diferentes autores (Lejarza, 2010; Rajadell, Pujol & Violant, 2005), un efecto enormemente constructivo en la difusión de valores que hagan atractivo el aprendizaje y necesario el esfuerzo por conseguirlo. Sin duda enseñar y compartir la televisión será mucho más eficaz que restringirla o limitarla.

Reconocimientos

Investigación incluida en un proyecto financiado por el Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia con referencia EDU2008-00207/EDUC dentro del Plan Nacional de Investigación Científica, Desarrollo e Innovación Tecnología.

Referencias

Aierbe, A.; Medrano, C. & Martínez de Morentin, J.I. (2010). La privacidad en programas televi-sivos: percepción de los adolescentes. Comunicar, 35; 95-103.

Asamen, J.H.; Ellis, M.L. & Berry, G.L. (2008). Child Development, Multiculturalism, and Media. Londres: Sage.

Bauman, Z. (2003). Comunidad. En busca de seguridad en un mundo hostil. Madrid: Siglo XXI.

Bendit, R. (2000). Adolescencia y participación: una visión panorámica en los países de la Unión Europea. Anuario de Psicología, 31, 2; 33-57.

Bryant, J. & Vorderer, P. (2006). Psychology of Entertainment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawerence Erlbaum Associates.

Castells, M. (2009). Comunicación y poder. Madrid: Alianza.

Dates, J.L.; Fears, l.M. & Stedman, J. (2008). An Evaluation of Effects of Movies on Adolescent Viewers, en Asamen, J.H.; Ellis, M.L & Berry, G.L. (Eds.) Child Development, Multiculturalism, and Media. London: Sage; 261-277.

Del Moral, M.E. & Villalustre, L. (2006). Valores televisivos versus valores educativos: modelos cuestionables para el aprendizaje social. Comunicación y Pedagogía: Nuevas tecnologías y recursos didácticos, 214; 35-40.

Del Río, P.; Álvarez, A. & Del Río, M. (2004). Pigmalión. Informe sobre el impacto de la televisión en la infancia. Madrid: Fundación Infancia y Aprendizaje.

Entidad de Gestión de los Derechos de los Productores Audiovisuales EGEDA (2010). Panorama audiovisual, 2010. Madrid: EGEDA.

Fisherkeller, J. (1997). Everyday Learning about Identities Among Young Adolescents in Television Culture. Anthropology and Education Quaterly, 28, 4; 467-492.

Fundación Antena 3 (2010). En busca del éxito educativo: realidades y soluciones. Madrid: Fun-daciones Antena 3.

Goldsmith, S. (2010). The Power of Social Innovation. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Guarinos, V. (2009). Fenómenos televisivos ‘teenagers’: Prototipias adolescentes en series vistas en España. Comunicar, 33; 203-211.

Jonson, B. & Flanagan, C. (2000). Les idées des jeunes sur la justice distributive, les droits et les obligations: étude transculturelle. Revue International des Sciencies Sociales, 164; 223-236.

Lejarza, M. (2010). Desde los medios de comunicación: Enseñar y compartir la televisión, en Maeso Rubio, F. (Ed.). La TV y la educación en valores. Comunicar 31; 417-437.

Medrano, C. & Cortés, A. (2007). Teaching and Learning of Values through Television. Review International of Education, 53, 1; 5-21.

Medrano, C., Aierbe, A. & Orejudo, S. (2010). Television Viewing Profile and Values: Implications for Moral Education. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 15, 1; 57-76.

Méndiz, A. (2005). La juventud en la publicidad. Revista de Estudios de Juventud, 68; 104-115.

Murray, J.P. & Murray, A.D. (2008). Television: Uses and Effects, en Haith, M.M. & Benson, J. B. (Eds.). Encyclopedia of Infant and Early Childhood Development. NY: Academic Press; 309-318.

Orozco, G. (2010). Niños, maestros y pantallas. Televisión, audiencias y educación. Guadalajara (México): Ediciones de la Noche.

Pasquier, D. (1996). Teen Series Reception: Television, Adolescent and Culture of Feelings. Child-hood: A Global Journal of Child Research, 3, 3; 351-373.

Pindado, J. (2006). Los medios de comunicación y la construcción de la identidad adolescente. Zez, 21; 11-22.

Pinilla, E.R.; Muñoz, L.R. & al. (2003). Reality Show en Colombia: sobre la construcción social de valores. Bogotá: Comisión Nacional de Televisión CNTV.

Potter, W.J. (1990). Adolescents´perceptions of the Primary Values of Televisión Programming. Journalism Quarterly, 67; 843-853.

Raffa, J.B. (1983). Televisión: The Newest Moral Educator? Phi Delta Kappan, 65, 3; 214-215.

Rajadell, N.; Pujol, M.A. & Violant, V. (2005). Los dibujos animados como recurso de transmisión de valores educativos y culturales. Comunicar, 25.

Schwartz, S.H. & Boehnke, K. (2003). Evaluating the Structure of Human Values with Confirma-tory Factor Analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 38; 230-255.

Schwartz, S.H.; Sagiv, L. & Boehnke, K. (2000). Worries and Values. Journal of Personality, 68; 309-346.

Smith, S.W.; Smith, S.L. & al. (2006). Altruism on American Television: Examining the Amount of, and Context Surronding. Acts of Helping and Sharing. Journal of Comunication, 56, 4; 707-727.

Tan, A.; Nelson, L.; Dong, Q. & Tan, G. (1997). Value Acceptance in Adolescent Socialization: A Test of a Cognitive-functional Theory of Television Effects. Communication Monographs, 64; 82-97.

Document information

Published on 30/09/11

Accepted on 30/09/11

Submitted on 30/09/11

Volume 19, Issue 2, 2011

DOI: 10.3916/C37-2011-03-03

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?