Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

In the framework of the «Project I: CUD» (Internet: Creatively Unveiling Discrimination), carried out in the United Kingdom, Italy, Belgium, Romania and Spain, we conducted a study into the expressions of discrimination used by young people on social network sites (SNS). To do so we designed a methodological strategy for detecting discriminatory content in 493 Facebook profiles and used this strategy to collect 363 examples for further analysis. Our aims were to compile information on the various types of discriminatory content and how they function online in order to create tools and strategies that can be used by trainers, teachers and families to combat discrimination on the Internet. Through this study we have detected patterns between young men and young women that reveal that there is a feminine and a masculine way of behaving on the Internet and that there are different ways of expressing discrimination on SNS. Men tend to be more direct in their posting and sharing of messages. Their messages, which are also more clearly discriminatory, focus more on discrimination towards ethnic groups and cultural minorities. Women, on the other hand, tend to use indirect (reactive) discriminatory strategies with a less obvious discriminatory component that mainly focuses on sociocultural status and physical appearance.

1. Introduction and state of the question

Our research focused on compiling information about different types of discriminatory content and their online presence. Our main aim was to detect differences between behavioural patterns on Facebook (our sample SNS) in an attempt to further our understanding of how discriminatory content is transformed on SNS and its patterns disseminated. Having obtained information about young people’s1 behaviour, our next step was to give practical advice to create tools or strategies to fight against discrimination and its expressions on the Net.

To this end, in the I:CUD project, we defined the concept of digital discrimination as the representation of discriminatory content and attitude by digital means. This definition implies that digital discrimination represents not a new reality, but a new way of expressing and disseminating discriminatory content.

1.1. Social networks: paths for interaction

As a starting point we would like to contextualize the research in the general framework of SNS and Internet sociability. For Schneider & al. (2009) and Rambaran & al. (2015), an online social network is a community of individuals who share interests, activities, experiences and/or friendship. Most networks are available on the Web, and users can publish profiles with text, image and video, and interact with other members. The research conducted by Garton, Haythornthwaite & Wellman (1997) shows that virtual communities can be understood as relational communities in which sociability has quantitative and qualitative patterns that are different from those of classical physical sociability. For Quan-Haase & Wellman (2002) and Haythornthwaite & Wellman (2002), communities created around the Internet are «personal communities» (communities based on individual interests and affinities between people who decide to connect).

SNS make new interactions possible and, therefore, help to create new forms of sociability. Martuccelli (2002), for example, states that the Internet is a strong support in the process of individuation. For many users, the main purpose of the World Wide Web is to create contacts (Kadushin, 2013), and SNS increase the individual social capital of young people (Ellison, Steinfield, & Lampe, 2007). Even so, some researchers conclude that the Internet and SNS help to create weak relational ties, quite unlike the strong ties2 created in other fields of socialization (Haythornthwaite, 2005). Far from being a negative feature of networks, this is its distinctive mark: networks make it possible to create infinite weak contacts, but it is also useful for strengthening those strong ties created in offline relations. Likewise, Castells (2001) concludes that this ongoing tendency decreases physical community-based sociability. Other researchers (Steffes & Burgee, 2009) have shown that people who are connected through SNS have homophile relations, different tie strengths and similar decision-making patterns. The behavioural patterns in small-medium relational circles are similar and the number and intensity of the interpersonal links strengthen these patterns (Centola, 2015). Stefanone & Jang (2007) concluded that the main personal attitudes and skills that lead to using blogs are the same as those that are required to maintain strong-tie networks: extroversion and self-revelation. On the other hand, they concluded that age, gender and educational level are not correlated to network size, blog content or the use of blogs to maintain relations and strong ties.

Wellman & al. (2001) proved the correlation between bigger physical social networks and Internet use. This is what they define as «the more, the more». And the opposite is also true: the more individuals use Internet social networks, the more they will use offline networks. Boyd (2007) has studied the potential audiences technologies can have. These audiences help to develop the properties of technology and the applications that are derived from it. According to Boyd, the audience is partially determined by the following features: 1) persistence, 2) searchability, 3) reproducibility and 4) invisible audiences. These features help to understand the Internet as a double-edged sword if you are not discerning enough to distinguish between the contents that are being transmitted. Those contents are persistent, but they are also easily reproducible. They are often inaccurately summarized or generate stereotyped versions of the initial contents, reaching the invisible audiences that Boyd described. Joinson (2003) underlined the synchrony created by the swiftness in which individuals enter into conversation on the net. Internet helps to create constant interactive situations and opportunities because of the low connection costs, the ease in which computers and applications can be reached, the anonymity of the connection and the possibility of enjoying privacy in a conversation with multiple speakers. Joinson also warns of the quandaries associated with the fraudulent use of net content and the negative impacts of anonymous criminal behaviour. However, he describes the paradox of the coexistence of research that shows that the Internet helps both to desocialize people and to strengthen preexisting relational and social skills. For him, the Internet can help to share life’s experiences and vicissitudes, and can be a practical self-help platform for problem solving and finding company in difficult situations. He concludes that there are benefits in virtual communities and websites, from both the emotional point of view, and the point of view of information exchange.

1.2. Theoretical framework: Women and men on the Net1.2.1. Is there a masculine and a feminine way of interacting in SNS?

The number of Facebook users is estimated to be three times the number of inhabitants of the US. At the end of 2012, Facebook had 800 million users around the world. A total of 65% of North-American adults had entered a profile in some sort of SNS and 92% of these profiles had been created on Facebook. Of the young users of Internet, 80% are active users of SNS, and over half of these write and send messages regularly through networks (García, Alonso, & del-Hoyo, 2013). It is estimated that 75% of Internet users under the age of 25 have an SNS profile (Lenhart, 2009). It is undeniable then that the use of SNS is gaining enormous importance in teenagers’ lives.

In the Spanish case, 93% of young people between 11 and 20 years old take part in SNS (Urueña & al., 2011; Fundación Pfizer, 2009). This high percentage of SNS use can be understood as an indicator of the ongoing revolution in the ways young people communicate, but it also means that their process of socialization is different. Although the framework of socialization used to be the family and school, it has now extended to include social networks. As many authors have stated, networks have a great impact on socialization, particularly on gender socialization (Gómez, 2010; Huffaker & Calvert, 2005; Bortee, 2005; Thelwall, 2008). Therefore, gender, sexuality and identity are becoming more and more open and Internet gender socialization is a new way of socialization that is based on a modern definition of gender and revolves around the concepts of fluidity, construction and performance. Although Livingstone & al. (2014) focused on kids’ online behavior (9 to 16) and found few differences between the tastes and interests of girls and boys, Bringué & Sádaba (2011) obtained interesting results on gendered approaches to online activity: teenage girls are keener than boys to surf the net with friends, teachers or parents.

Social networks are a necessary socialization space for contemporary youngsters: they have become places where they can meet and get to know each other, introduce and represent themselves, build their identity, share their hobbies and tastes, and learn new skills and abilities that help in their personal and social development. Contemporary youth cannot be understood without taking the transformative power of the Internet into account. SNS have become an environment for exploring self-identity and for the self-representation of young people (Tortajada, Araüna, & Martínez, 2013; Stern, 2004; Manago & al., 2008). Espinar & González-Río (2009: 88) state that there is little information available about the new phenomena of SNS on the Internet and its use by young people. In particular, there is little data on the different possible uses made of them by men and women. They also point out that the differences between men and women are not linked to how much, but to how they use Internet.

As far as interaction is concerned, Valkenburg, Schouten, & Peter (2005) analyzed the different strategies of self-representation that are used by the different genders when preparing their personal pages on the Internet. Men tend to emphasize their status, capacities and competences, and generally use shapes and icons linked to technology. For their part, women tend to present themselves as nice and attractive, and use drawings of flowers and pastel colours. In their study, after analyzing 609 teenagers, they concluded that 50% of the young people interviewed changed their identity. Younger teenagers were keen to alter or transform identity, and some gender differences were detected in the changes made: men tended to reinforce masculine stereotypes, while women tried to adopt adult attitudes and transform their physical appearance.

1.2.2. Gender system and SNS

Masculinity and femininity are core concepts in the definition of the gender system. They involve the values, experiences and meanings that are associated with women and men and which define feminine and masculine images. These notions change from one period to another and from one culture to another, but they are expressed in every particular situation through beliefs and expectancies (Alvesson & Billing, 1997). Gender, then, is a social construct not a natural quality. It is organised hierarchically and legitimates different treatment for men and women. The distinction between sex and gender represented an important break from the functionalist paradigm of traditional sexual roles, and allowed feminists to explore the cultural basis of sexism (Amorós, 1994; Valcárcel, 1994).

The origin of the concept of gender can be found in the work of Rubin (1975). From the very beginning, gender theory suggested that there was a difference between sex and gender. Sex is understood as a biological category linked to individual chromosomes and expressed in genital organs and hormones. Gender, on the other hand, is associated with a complex set of social processes that create and maintain differences between men and women.

The gender system makes it possible to understand a model of society in which biological differences between men and women are translated into social, political or economic inequalities between sexes, with women being the more disadvantaged (Rubin, 1975). These elements of the gender system contribute to the creation of omnipresent structures that organize human behaviours and social practices in terms of differentiation between men and women (Bourdieu, 2000; Fenstermaker & West, 2002). In other words, this system helps to produce two different types of person: women and men. Women develop as they do because they have a shared assumption of what being a woman means. The same can be said of men. These beliefs are not created ex novo: they are linked to predominant cultural ideologies (Alvesson & Billing, 1997; Deaux & Stewart, 2001). The messages about gender come from diverse and fragmented sources that are often contradictory: society, subcultures, organisations, family, school, media or individuals. As a result, gender identity can have multiple forms and often conceals considerable ambivalence. Individuals can choose whether to accept or reject these cultural associations in their own thoughts, actions and self-comprehensions (Deaux & Stewart, 2001). The social definition of men as power owners, for example, can be translated into an image of masculinity tied not only by beliefs, behaviours and emotional states, but also by physical strength or the body positions adopted by men. This example shows how male power can be understood as part of the natural order (Connell, 1993; Valcárcel, 1994). In contemporary societies, hegemonic masculinity (Connell, 1993) tends to emphasise authority, autonomy and self-sufficiency, while idealised femininity is linked to the satisfaction of men’s desires. Obviously these images do not necessarily correspond to what most women and men are, but large numbers of people share these ideas. Connell (2002) described other forms of masculinity: the subordinated masculinities that are based on their identification with femininity. The range of forms that masculinity adopts is partially determined by the interaction between gender and such other variables as ethnic group or social class (Curington, Lin & Lundquist, 2015).

2. Materials and method

Our research took place between December 2012 and November 2014 in five different cities at the same time: and Barcelona/Tarragona. The methodological framework provided information about how discriminatory expressions are, consciously and unconsciously, transformed to adapt to the Internet environment.

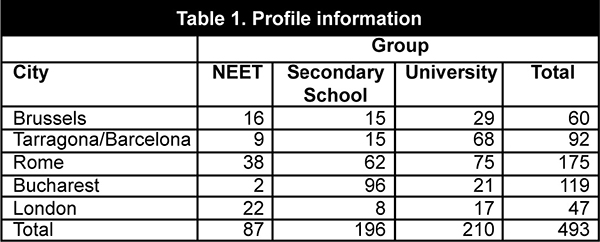

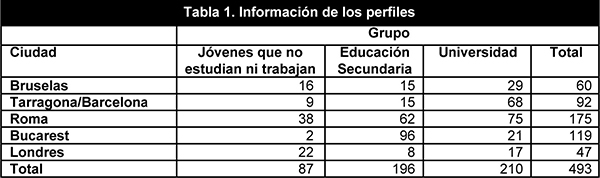

The methodology consisted of a discourse analysis of the contents collected after creating 15 profiles (three per city) and 50 friends per profile (table 1). These three profiles were constructed in accordance with the position of the participant in the educational system (university student, secondary-school student and NEET [Not in Education, Employment or Training]). To ensure that participants could freely take part in the project and that they were aware of what participation involved, each new «friend» received a message from the profile with information about the project and the methodology and a guarantee of data protection.

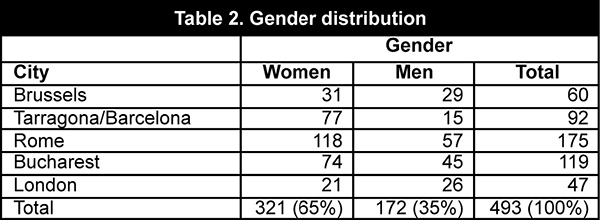

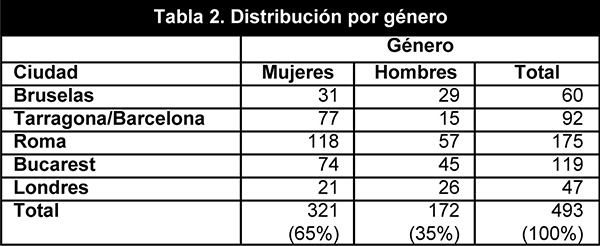

The final number of participants was 493. The final sample is made up of 65% women and 35% men (table 2). Many factors may contribute to this higher ratio of women in our sample: they may be closer to the organisations that participate in the project or they may be more willing to participate in a project on discrimination issues. Ultimately, however, these values are similar to the gender distribution in Facebook (Dugan & Brenner, 2013). As far as age is concerned, most of the sample members are concentrated between 17 and 24 years old. Even the concept of young is wide and undefined at the extremes but, generally, this period in life is between 16 and 30 years old.

We checked the information that these 493 participants were posting on Facebook in order to detect content or activities that could be regarded as discriminatory. Every item that we found was described and categorized. Following this methodology we finally collected, described and categorized 363 examples of discriminatory content.

We asked the researchers to evaluate the intensity of discriminatory content with a subjective Likert scale from 1 (slightly discriminatory) to 5 (highly discriminatory). We carried out an internal consistency test to check the dispersion of results of the various researchers, who are members of NGOs devoted to discrimination prevention. The Rho Spearman test highly correlated between all the members of the research team (for 9 of 10 possible combinations), which pointed to a high internal consistency in the evaluative criteria used by the research team and validated the discrimination scale as an analytical variable.

3. Analysis and results

3.1. Discriminatory intensity

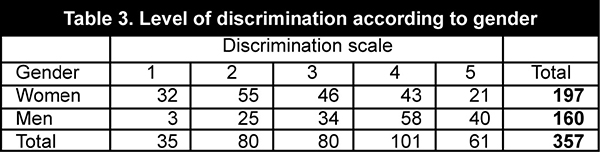

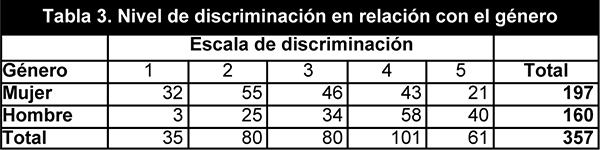

We found significant differences when crossing the data of the discrimination scale. The discriminatory content posted by the Neets and the secondary school pupils was significantly more intense than the content of the university group. Likewise, examples of discrimination posted by women are considered to be significantly less discriminatory than those posted by men. These data indicate that differences depend on educational level and gender. Young men are the group that is expected to be the most discriminatory and university women the least (table 3).

The chi-square test gave significant results when gender was crossed with the discrimination scale (42.5 and a=0,000 for a 95% significance level) and with the type of discrimination (66.8 and a=0,000 for a 95% significance level).

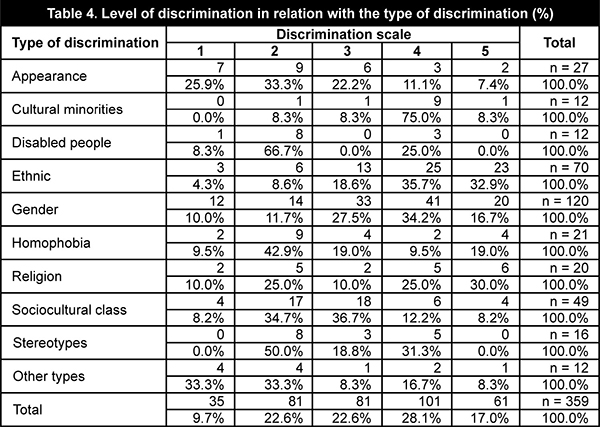

Some of the types of discrimination on the discriminatory scale were rated as highly discriminatory (for example, ethnic or religious). Gender discrimination occupied a medium position, while discrimination of physical appearance, socio-cultural class or homosexuals appears to be easily concealed. In general these types of discrimination are considered to be highly incorrect or aggressive in society and are the same as the types that are considered to be most discriminatory. It must be assumed that the researchers’ process of evaluation ultimately depends on the subjective approach that individuals have to the reality analysed, and those elements that are generally considered to be highly discriminatory tend to be reproduced. It is easy to regard some types of discrimination as strong but this merely points to the need to work with types of discrimination other than «the traditional ones», which need to be much more aggressive if they are to be considered in the same way. This unconscious difference between different types of discriminatory attitudes can give some clues to understanding how some content is easily disseminated. Facebook enables some content to be tagged as inappropriate and deleted, but if users only detect traditional forms of discrimination, the rest can easily survive.

Tables 3 and 4 show that discrimination is greatest on gender issues. There are significant differences between the way in which boys and girls use discriminatory content: boys are more focused on gender discrimination and more aggressive in their comments. Girls, on the other hand, focus more on physical appearance and social class, which are «lighter» forms of discrimination according to our scale. To further classify individual attitudes to discrimination, we created categories to describe how young people were disseminating discriminatory content and comments:

a) «Like» to discriminatory comments made by others.

b) «Like» to discriminatory content posted by others.

c) Discriminatory comment made by him/herself.

d) Discriminatory comment made by others on his/her wall.

e) Link to discriminatory content posted by him/herself.

f) Other option.

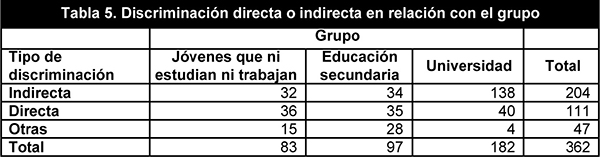

In an attempt to apply the principle of parsimony (provide the simplest explanations possible without losing information), we decided to reduce those categories to three, depending on who is taking the action:

a) Direct discrimination: the users themselves create/post the content.

b) Indirect discrimination: the users accept/agree with discriminatory content, and help to spread it by their action.

c) Other options.

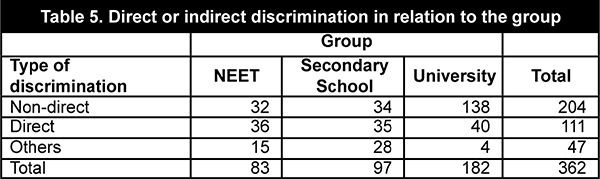

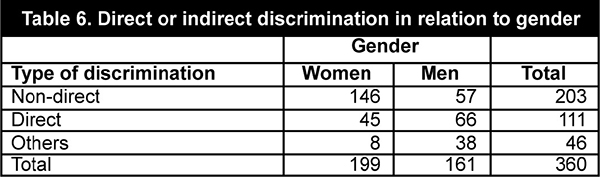

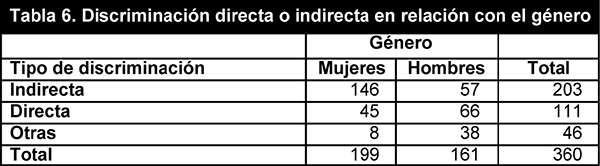

These new categories show that attitudes depend on the participant’s gender and the group they are in (table 5 and 6). Secondary-school students, NEETS and men tend to create or publish contents on their own, while university students and women tend to accept comments published by others. This difference reinforces the idea that men and women have different attitudes towards content and makes it possible to define masculine and feminine patterns of «facebooking».

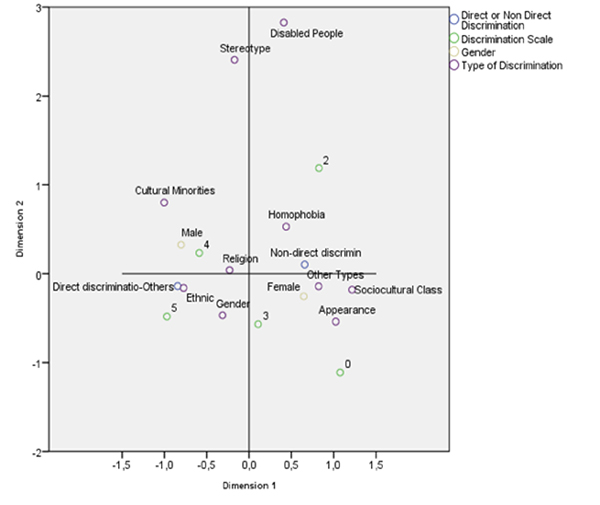

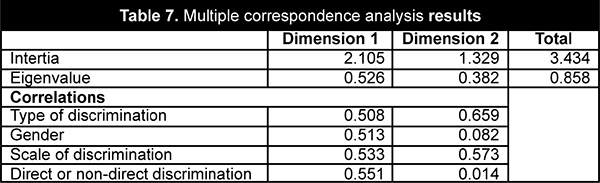

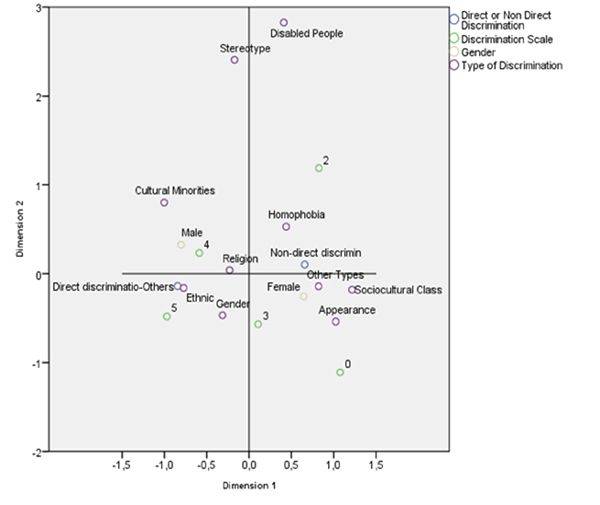

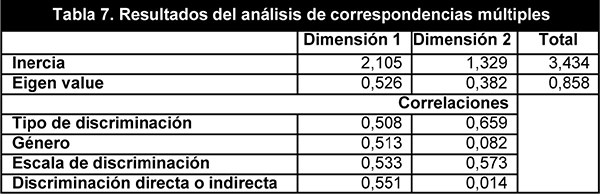

Finally, the holistic analysis of the data presented above suggests the existence of multiple correlations among the variables in the system. To obtain information about the significance and direction of these multiple relations, we developed a multiple correspondence analysis3.

The results reveal that two variables (gender and type of discrimination) explain 85.8% of the model variance (table 7). The correlation of the variables with the two dimensions resulting from the ACM are significant. The first axis is defined by direct/indirect discrimination and intensity, and can be understood in terms of gender differences. The second axis is defined by the type of discrimination. These results are important as they reveal that men are associated with aggressive, direct discriminatory content that is focused on ethnic, gender and religious issues. Women’s attitudes are less aggressive, indirect and focused on physical appearance, sociocultural class and homophobic issues.

4. Conclusions and discussion

As Bernárdez-Rodal (2006: 81) states «the dichotomous structure of genders around the masculine and feminine axes neither disappears nor changes, even when conditions are ideal. Despite interacting in cyberspace, the body is still important. In one way or another, interaction still takes place through it». The fact that the Internet allows you to abandon your body has been considered, at least by some feminist theorists, as an opportunity for feminine liberation, because women have been so subject to its corporeality. However, no teenagers, neither boys nor girls, seem to wish to do so. Gender determinism is still fundamental, and when «body» is not present, «word» takes its place.

We have shown that boys and girls express themselves differently when they are interacting on Facebook in three different ways: 1) the type of discrimination, 2) the scale of discrimination and 3) the way they produce these discriminatory expressions. We have also combined all these variables to find multiple correspondences between masculine and feminine patterns of behaviour on SNS and also significant differences. These differences are so important that it seems that males and females behave differently on the Internet and have different approaches to discrimination on social networks. Likewise, Mascheroni, & Ólafsson (2014) showed differences in terms of the approach to privacy: men are more likely to have public profiles, while women tend to have private ones.

Boys tend to make discriminatory comments about ethnic origin, gender issues and cultural minorities, while girls focus on physical appearance and social class. The discriminatory comments of men have been labelled as more intense on the discrimination scale, particularly the comments linked to gender; on the other hand, women make lighter comments. In summary, men use direct discriminatory attitudes, while women use indirect ones.

In general, discrimination tends to be understood and scaled in terms of the topic or the collective focus of its impact, as some categories or groups are more easily identified than others. Discrimination for ethnic origin and gender –especially the former– has traditionally been the objective of several campaigns to raise awareness about what it involves. Meanwhile, other types of discrimination have been socially accepted or have remained invisible (for example, social class or appearance). In this research, we have underlined the importance of sex differences for understanding discriminatory attitudes. The intensity, type and way in which discrimination is expressed and reproduced can be tied to sex. Men’s tendency to have more discriminatory attitudes on the three levels can be understood as a pattern of affirming masculinity during youth.

Figure 1. Multiple Correspondence Analysis results.

We should point out that this research does have some weaknesses (for example, the delimitation of some concepts or the limits of the object of study). Therefore, the issue of how youngsters and teenagers are using SNS needs to be further investigated. It is particularly necessary to carry out ethnographic research to analyse how boys and girls behave on the Net, and how language and power are used.

Finally, we should not forget that SNS act as loudspeakers that give visibility to attitudes that are common in young people and that used to be expressed only in a physical and individual way. SNS record these attitudes in a public or semi-public way, making the content available to a wider range of people and lasting over time. When young people post content, the pattern of expression is still determined by our oral face-to-face tradition. They do not generally think that these contents do not follow the same rules and need longer reflexive processes to avoid possible impacts on other people or their own future.

Notes

1The young people were informed about what their participation involved, in accordance with the legislation of each of the participating countries.

2 The concepts of weak and strong ties were developed as a tool to describe interpersonal relations in networks. Granovetter (1973) described the strength of an inter-individual tie as a combination of the amount of time, the emotional intensity, the intimacy and the mutual services that characterise the relation. He also underlines the leading role that weak ties play in promoting integration and in constructing community. For this author, weak ties are indispensable for individual opportunities.

3 The aim of MCA is to help to reduce the complexity of the holistic analysis by gathering data into simple patterns of interpretation. It creates a coordinate axes display in which the information is grouped according to the closeness of the answers.

Funding and acknowledgement

The I:CUD project is a project co-funded by the Fundamental Rights and Citizenship Programme of the European Union, coordinated by CEPS Projectes Socials, Barcelona (www.asceps.org) and developed by the SBRlab research group of the Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona (www.sbrlab.com), Fundatia PACT, Bucharest (www.fundatiapact.ro), Pour la Solidarité, Brussels (www.pourlasolidarite.eu), Collage Arts, London (www.collage-arts.org) and CIES, Rome (www.cies.it). For further information about the research, project and outcomes, visit the project site: www.digitaldiscrimination.eu.

References

Alvesson, M., & Billing, Y. (1997). Understanding Gender and Organizations. London: Sage Publications.

Amorós, C. (1994). Feminismo: igualdad y diferencia. México: UNAM.

Bernárdez-Rodal, A. (2006). A la búsqueda de una ‘habitación propia’: comportamiento de género en el uso de Internet y los chats en la adolescencia. Revista de Estudios de la Juventud, 73, 69-82. (http://goo.gl/8kXFfT) (30-07-2015).

Bortee, D.S. (2005). Presentation of Self on the Web: An Ethnographic Study of Teenage Girls. Education, Communication & Information, 5(1), 25-39. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14636310500061102

Bourdieu, P. (2000). Poder, derecho y clases sociales. Bilbao: Desclée de Brouwer.

Boyd, D. (2007). Why Youth Heart Social Network Sites: The Role of Networked Publics in Teenage Social Life. Cambridge: Berkman Centre for Internet & Society at Harvard University. Research Publication 2007-16. (http://goo.gl/bTm3NK) (30-07-2015).

Bringué, X., & Sádaba, C.C. (2011). Menores y redes sociales. Foro Generaciones Interactivas. Madrid: Fundación Telefónica.

Castells, M. (2001). Internet y la sociedad red. Lección inaugural del Programa de Doctorado sobre la sociedad de la información y el conocimiento. Barcelona: UOC. (http://goo.gl/Ga4Xs7) (30-07-2015).

Centola, D. (2015). The Social Origins of Networks and Diffusion. American Journal of Sociology, 120(5), 1295-1338. (http://goo.gl/Zhh0CT) (31-07-2015).

Connell, R.W. (1993). Gender and Power. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Connell, R.W. (2002). Gender Short Introductions. Cambridge: Polity Press, Blackwell Publishers.

Curington, C. V., Lin K-H., & Lundquist, J. H. (2015). Positioning Multiraciality in Cyberspace: Treatment of Multiracial Daters in an Online Dating Website. American Sociological Review 80, 764-788. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0003122415591268

Deaux, K., & Stewart, A. (2001). Framing Gendered Identities. In R.K. Unger (Ed.), Handbook of the Psychology of Women and Gender. Canada: John Wiley & Sons.

Dugan, M., & Brenner, J. (2013). The Demography of Social Media Users 2012. (http://goo.gl/IlfeUA) (12-07-2014).

Ellison, N.E., Stein?eld, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The Bene?ts of Facebook ‘Friends’: Social Capital and College Students Use of Online Social Network Sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1143-1168. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x

Espinar, E., & González-Río, M.J. (2009). Jóvenes en las redes sociales virtuales. Un análisis exploratorio de las diferencias de género. Feminismo/s, 14, 87-106. (http://goo.gl/5eCEXu) (30-07-2015)

Fenstermaker, S., & West, C. (2002). Doing Gender, Doing Difference: Inequality, Power and Institutional Change. New York: Routledge.

Fundación Pfizer (2009). La juventud y las redes sociales en Internet. Madrid: Fundación Pfizer. (https://goo.gl/3heSgn) (30-07-2015).

García, M.C., Alonso, J., & del Hoyo, M. (2013). La participación de los jóvenes en las redes sociales: finalidad, oportunidades y gratificaciones. Anàlisi, 48, 95-110. (https://goo.gl/qpYGKn) (30-07-2015).

Garton, L., Haythornthwaite, C., & Wellman, B. (1997). Studying Online Social Networks. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 3(1). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.111/j.1083-6101.1997.tb00062.x

Gómez, A.G. (2010). Lexical Encoding of Gender Relations and Identities. In R.M. Jiménez-Catalán (Coord.), Gender Perspectives on Vocabulary in Foreign and Second Languages (pp. 238-263). New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Granovetter, M.S. (1973). The Strength of Weak Ties. The American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1.360-1.380. (https://goo.gl/qhKbKs) (30-07-2015).

Haythornthwaite, C. (2005). Social Networks and Internet Connectivity Effects. Information, Community & Society, 8(2), 125-147. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13691180500146185

Haythornthwaite, C., & Wellman, H. (2002). The Internet in Everyday Life: An Introduction. In C. Haythornthwaite, & B. Wellman (Ed.), The Internet in Everyday Life (pp. 1-41). Malden: Blackwell Publishers.

Huffaker, D.A., & Calvert, S.L. (2005). Gender, Identity, and Language Use in Teenage Blogs. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 10(2). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2005.tb00238.x

Joinson, A.N. (2003). Understanding the Psychology of Internet Behaviour Virtual Worlds, Real Lives. Gales: Palgrave MacMillan.

Kadushin, C. (2013). Comprender las redes sociales. Teorías, conceptos y hallazgos. Madrid: CIS.

Lenhart, A. (2009). Adults and Social Network Websites (http://goo.gl/9rDtPq) (05-12-2013).

Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Görzig, A., & Ólafsson, K. (2014). Children’s Online Risks and Opportunities: Comparative Findings from EU Kids Online and Net Children Go Mobile. London: LSE. (http://goo.gl/PhuQoa) (30-07-2015).

Manago, A.M., & al. (2008). Self-presentation and Gender on MySpace. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 29(6), 446-458. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2008.07.001

Martuccelli, D. (2002). Grammaires de l’individu. Paris: Gallimard.

Mascheroni, G., & Ólafsson, K. (2014). Net Children go Mobile: Risks and Opportunities. Milano: Educatt.

Quan-Haase, A., & Wellman, B. (2002). Capitalizing on the Net: Social Contact, Civic Engagement and Sense of Community. In C. Haythornthwaite, & B. Wellman (Ed.), The Internet in Everyday Life (pp. 291-324). Malden: Blackwell Publishers.

Rambaran, A., Dijkstra, J.K., Munniksma, A. & Cillessen, A. (2015). The Development of Adolescents’ Friendships and Antipathies: A Longitudinal Multivariate Network Test of Balance Theory. Social Networks, 43, 162-176. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2015.05.003

Rubin, G. (1975). The Traffic in Women: Notes on the ‘Political Economy’ of Sex. In R. Reiter (Ed.), Toward an Anthropology of Women (pp. 157-210). New York: Monthly Review Press (http://goo.gl/FwEc54) (30-07-2015).

Schneider, F., Feldmann, A., Krishnamurthy, B., & Willinger, W. (2009). Understanding Online Social Network Usage from a Network Perspective. Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM Conference on Internet, Measurement (pp. 35-48). New York: ACM. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/1644893.1644899

Stefanone, M.A., & Jang, C.Y. (2007). Writing for Friends and Family: The Interpersonal Nature of Blogs. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 13(1), 123-140. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00389.x

Steffes, E.M., & Burgee, L.E. (2009). Social Ties and Online Word of Mouth. Internet Research, 19(1), 42-59. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/10662240910927812

Stern, S.R. (2004). Expressions of Identity Online: Prominent Features and Gender Differences in Adolescents’ World Wide Web Home Pages. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 48(2). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem4800_4

Thelwall, M. (2008). Social Networks, Gender, and Friending: An Analysis of MySpace Member Profiles. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 59(8), 1.321-1.330. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/asi.20835

Tortajada, I., Araüna, N., & Martínez, I. (2013). Advertising Stereotypes and Gender Representation in Social Networking Sites. Comunicar, 41(21), 177-186. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C41-2013-17

Urueña, A., Ferrari, A., Blanco, D., & Valdecasa, E. (2011). Las redes sociales en Internet, Observatorio Nacional de las Telecomunicaciones y de la Sociedad de la Información. (http://goo.gl/jxMYnF) (05-12-2014).

Valcárcel, A. (1994). Sexo y filosofía. Sobre la mujer y el poder. Barcelona: Anthropos.

Valkenburg, P.M., Schouten, A.P., & Peter, J. (2005). Adolescents’ Identity Experiments on the Internet. New Media & Society, 7, 383-402. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1461444805052282

Wellman, B., Haase, A.Q., Witte, J., & Hampton, K. (2001). Does the Internet Increase, Decrease, or Supplement Social Capital? Social Networks, Participation, and Community Commitment. American Behavioural Scientist, 45(3), 436-455. (http://goo.gl/oSYTZV) (30-07-2015).

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

En el marco del Proyecto «I:CUD» (Internet: Desenmascarando la discriminación creativamente), llevado a cabo en el Reino Unido, Italia, Bélgica, Rumanía y España, hemos desarrollado una investigación sobre las expresiones de discriminación utilizadas por los jóvenes en las redes sociales (SNS). Para la realización de esta investigación, se ha diseñado una estrategia metodológica de detección de contenidos discriminatorios en 493 perfiles de Facebook que ha permitido encontrar 363 ejemplos para su análisis. El objetivo de la misma ha sido la obtención de información acerca de los tipos de contenidos discriminatorios y su forma de funcionamiento on-line, para facilitar la creación de herramientas y estrategias para luchar contra la discriminación en la Red, y su utilización por parte de formadores, docentes y familias. Como resultado, hemos detectado algunos patrones diferenciales entre hombres y mujeres jóvenes que nos permiten afirmar la existencia de una forma femenina y otra masculina de comportarse en Internet y un uso diferencial de las SNS en relación con la discriminación. En cuanto a ésta, los hombres tienden a tener más actividad directa (publicando y compartiendo mensajes), con contenidos más claramente discriminatorios y, sobretodo, centrados en la discriminación hacia grupos étnicos y minorías culturales. Las mujeres, por su parte, tienden a utilizar estrategias de discriminación no directas (reactivas), con una menor evidencia del componente discriminatorio. Ellas, mayoritariamente, dirigen las actitudes discriminatorias hacia la situación sociocultural y la apariencia física.

1. Introducción y estado de la cuestión

Nuestra investigación se centró en la recogida de información sobre diferentes tipos de contenidos discriminatorios y su presencia on-line. El objetivo consistió en la detección de diferencias entre los patrones de comportamiento en Facebook (como ejemplo de red social) para ampliar la comprensión acerca de los contenidos discriminatorios en las redes sociales y su difusión. Obtenida la información acerca del comportamiento de los jóvenes1, nuestro siguiente paso fue establecer recomendaciones para la creación de herramientas y estrategias para la lucha contra la discriminación y sus expresiones en la Red.

Con este objetivo, en el proyecto I:CUD definimos el concepto de discriminación digital como la representación de contenidos y actitudes discriminatorias por medios digitales. Esta definición implica que la discriminación digital, sin ser una realidad nueva, representa una nueva forma de expresión y difusión de contenidos discriminatorios.

1.1. Redes sociales: caminos para la interacción

Como punto de partida, contextualizamos la investigación en el marco de las redes sociales y la sociabilidad en Internet. Para Schneider y otros (2009), y Rambaran y colaboradores (2015), una red social on-line es una comunidad de individuos que comparten intereses, actividades, experiencias y/o amistad. Muchas de ellas están disponibles en la web y, en ellas, sus usuarios pueden publicar perfiles con texto, imagen y vídeo, e interactuar. La investigación de Garton, Haythornthwaite y Wellman (1997) muestra que las comunidades virtuales se pueden entender como comunidades relacionales en las que la sociabilidad tiene patrones cuantitativos y cualitativos distintos de los patrones clásicos de sociabilidad. Para Quan-Haase y Wellman (2002), y Haythornthwaite y Wellman (2002), las comunidades creadas alrededor de Internet son «comunidades personales» (comunidades basadas en intereses y afinidades individuales entre personas que deciden conectarse).

Las redes sociales han permitido el surgimiento de nuevas interacciones y de nuevas formas de socialización. Martucelli (2002), por ejemplo, afirma que Internet es un fuerte apoyo en el proceso de individuación. Muchos usuarios tienen como principal objetivo en la web la creación de contactos (Kadushin, 2013), y las redes sociales aumentan el capital social de los y las jóvenes (Ellison, Steinfield, & Lampe, 2007). A pesar de ello, algunos investigadores afirman que Internet y las redes animan a la creación de enlaces débiles, a diferencia de los enlaces fuertes2 creados en otros campos de socialización (Haythornthwaite, 2005). Lejos de ser una característica negativa de las redes, es una marca distintiva: las redes facilitan la creación de una infinidad de contactos débiles que resultan útiles para fortalecer los enlaces fuertes creados en relaciones off-line. De manera similar, Castells (2001) concluye que esta tendencia actual reduce la sociabilidad basada en la comunidad física. Otros investigadores (Steffes & Burgee, 2009) han demostrado que las personas conectadas mediante redes tienen diferentes intensidades relacionales, relaciones homofílicas y patrones de toma de decisiones similares. Los patrones de comportamiento en grupos pequeños y medianos son similares entre sí y el número y la intensidad de los enlaces interpersonales refuerza estos enlaces (Centola, 2015). Stefanone y Jang (2007) concluyeron que las principales actitudes y habilidades que llevan a la utilización de blogs son las mismas que se requieren para mantener redes fuertes: extroversión y revelación de los propios pensamientos, emociones o actitudes (self-revelation). Por otro lado, concluyeron que la edad, el género y el nivel educativo no guardan relación con el tamaño de la red, el contenido de los blogs o el uso de blogs como forma de mantener relaciones fuertes.

Wellman y otros (2001) confirmaron la correlación entre el tamaño de la red social off-line y el uso de Internet, definiendo esta relación como «the more, more». Y su opuesto también sería cierto: a mayor utilización de redes sociales, mayor creación de redes off-line. Boyd (2007) estudió los usuarios potenciales de la tecnología, como elementos que ayudan al desarrollo de la misma y sus potencialidades. En concreto, la audiencia viene parcialmente determinada por: 1) la persistencia; 2) la capacidad de búsqueda; 3) la capacidad de reproducción y 4) las audiencias invisibles. Así, Internet se convierte en una hoja de doble filo si uno no es capaz de razonar lo suficiente como para distinguir entre los distintos contenidos que se transmiten, siendo éstos persistentes y, a la vez, fáciles de reproducir. Éstos se pueden encontrar a menudo presentados de forma imprecisa y/o estereotipada de los contenidos iniciales, alcanzando las audiencias invisibles (Boyd). Joinson (2003) subrayó la sincronía creada por la velocidad con la que las personas entran en conversaciones en la Red, ayudando a la creación de oportunidades y situaciones interactivas constantes, debido al bajo coste de la conectividad, el anonimato y la posibilidad de disfrutar de privacidad en una conversación con muchos interlocutores. Joinson también advierte acerca de los dilemas que se asocian al uso fraudulento de los contenidos de la Red y los impactos negativos del comportamiento criminal anónimo. Sin embargo, describe la paradoja de la coexistencia de investigaciones que demuestran cómo Internet ayuda tanto a des-socializar a las personas así como a fortalecer relaciones anteriores y habilidades sociales. Para él, Internet puede ayudar a compartir experiencias vitales y puede ser una plataforma práctica de autoayuda. Concluye que hay beneficios tanto emocionales como de intercambio de información en las comunidades virtuales y páginas web.

1.2. Marco teórico: Mujeres y hombres en la Red1.2.1. ¿Hay una forma masculina y femenina de interactuar en las redes sociales?

Se estima que el número de usuarios de Facebook es tres veces el número de habitantes de Estados Unidos. A finales de 2012, Facebook tenía 800 millones de usuarios en el mundo. Un 65% de los norteamericanos adultos habían creado un perfil en alguna red social y un 92% de ellos lo habían creado en Facebook. Entre los usuarios jóvenes de Internet, un 80% son usuarios activos de las redes, y más de la mitad de ellos escriben y mandan habitualmente mensajes mediante la Red (García, Alonso, & del-Hoyo, 2013). Se estima que un 75% de los usuarios de Internet menores de 25 años tienen un perfil en alguna red social (Lenhart, 2009). Es innegable que la utilización de las redes tiene una enorme importancia en la vida de los jóvenes.

En el caso español, un 93% de los jóvenes entre 11 y 20 años han participado en alguna redes (Urueña & al., 2011; Fundación Pfizer, 2009). Este porcentaje tan elevado puede ser entendido como un indicador de la revolución en las formas de comunicación en la actualidad, pero también muestra la existencia de diferencias en la socialización. Si bien tradicionalmente la socialización ha descansado en la familia y la escuela, actualmente se ha extendido también a las redes. Tal y como diversos autores sostienen, las redes tienen un gran impacto en la socialización y particularmente en la socialización de género (Gómez, 2010; Huffaker & Calvert, 2005; Bortee, 2005; Thelwall, 2008). Por lo tanto, el género, la sexualidad y la identidad están abriéndose y la socialización de género en Internet está convirtiéndose en una nueva forma de socialización basada en una definición moderna de género que gira alrededor de los conceptos de fluidez, construcción y actuación. A pesar de que Livingstone y otros (2014), centrándose en el comportamiento on-line de niños/as (9 a 16), encontraron pocas diferencias entre los gustos y los intereses de chicas y chicos, Bringué y Sádaba (2011) obtuvieron resultados interesantes en relación al género y la actividad on-line: las adolescentes presentaban una mayor tendencia que los adolescentes a navegar acompañadas (amigos, profesores, familiares).

Las redes sociales son un espacio de socialización necesario para los jóvenes: se han convertido en lugares de encuentro y de relación, en los que introducirse, construir la propia identidad y auto-representarse, compartir gustos y hobbies, y adquirir conocimientos y habilidades para el desarrollo personal y social (Tortajada, Araüna, & Martínez, 2013; Stern, 2004; Manago & al., 2008). La juventud contemporánea no puede ser entendida sin tener en consideración el poder transformador de Internet. Espinar y González-Río (2009: 88) afirman que hay poca información disponible sobre el nuevo fenómeno de las redes sociales en Internet y su utilización por parte de la juventud; en particular, sobre los diferentes usos posibles dados por hombres y mujeres. También señalan que las diferencias entre hombres y mujeres no se producen en cuanto usan Internet sino en su utilización.

En relación con la interacción, Valkenburg, Schouten, & Peter (2005) analizaron las distintas estrategias de autorrepresentación utilizadas en la preparación de páginas de Internet. Los hombres tienden a remarcar su estatus, capacidades y competencias, utilizando, generalmente, formas e iconos conectados con la tecnología. Las mujeres, por su parte, tienden a presentarse a sí mismas como guapas y atractivas, utilizando dibujos de flores y colores pastel. En su estudio, después de analizar 609 jóvenes, concluyeron que el 50% de los jóvenes cambiaron su identidad, detectando algunas diferencias de género en estos cambios: los hombres tendieron a reforzar estereotipos masculinos, mientras que las mujeres intentaron adoptar actitudes adultas y transformar su apariencia física.

1.2.2. El sistema de género y las redes sociales

Masculinidad y feminidad son conceptos centrales en la definición del sistema de género. Vinculan valores, experiencias y significados que se asocian con el hombre y la mujer, la imagen masculina y la femenina. Estas nociones cambian de una época a otra, así como de una cultura a otra, y se expresan mediante creencias y expectativas (Alvesson & Billing, 1997). El género, pues, es un constructo social, no una cualidad natural. Se organiza de manera jerárquica y legítima un trato distinto para hombres y mujeres. La distinción entre sexo y género representó una fractura importante respecto al paradigma funcionalista de los roles sexuales tradicionales y permitió al feminismo explorar la base cultural del sexismo (Amorós, 1994; Valcárcel, 1994).

El origen del concepto de género se puede hallar en el trabajo de Rubin (1975). Desde sus inicios, la teoría de género apuntó a la existencia de diferencias entre sexo y género: entendiendo el sexo como una categoría biológica que se expresa a través de los órganos genitales y las hormonas; mientras que el género se asocia a los procesos sociales que crean y mantienen las diferencias entre hombres y mujeres.

El sistema de género permite entender un modelo de sociedad en la cual las diferencias biológicas entre hombres y mujeres se transforman en desigualdades a nivel social, político o económico, siendo las mujeres las más desfavorecidas (Rubin, 1975). Estos elementos del sistema de género contribuyen a la creación de estructuras omnipresentes que organizan los comportamientos humanos y las prácticas sociales en términos de diferenciación entre hombres y mujeres (Bourdieu, 2000; Fenstermaker & West, 2002). En otras palabras, este sistema crea dos tipos distintos de personas: mujeres y hombres. Las mujeres se han desarrollado del modo en que lo han hecho porque tienen una asunción compartida de lo que implica ser una mujer, y lo mismo puede decirse de los hombres. Estas creencias no han sido creadas ex novo: están conectadas con las ideologías culturales dominantes (Alvesson & Billing, 1997; Deaux & Stewart, 2001). Los mensajes sobre el género vienen de fuentes diversas y fragmentadas, a menudo contradictorias: sociedad, subcultura, organización, familia, escuela, medios de comunicación o individuos. Como resultado, la identidad de género presenta múltiples formas, en ocasiones ambivalentes. Los individuos pueden escoger entre aceptar o rechazar estas asociaciones culturales en sus acciones, pensamientos o auto-comprensiones (Deaux & Stewart, 2001). La definición social del hombre como poseedor del poder, por ejemplo, se puede traducir en una imagen de masculinidad ligada no sólo a sus creencias, comportamientos o emociones, sino también a la fortaleza física o a las posiciones corporales adoptadas por ellos. Así, el poder masculino puede ser entendido como parte del orden natural (Connell, 1993; Valcárcel, 1994). En las sociedades contemporáneas, la masculinidad hegemónica (Connell, 1993) tiende a enfatizar la autoridad, la autonomía y la autosuficiencia, mientras que la feminidad idealizada está ligada a la satisfacción de los deseos masculinos. Obviamente, estas imágenes no corresponden necesariamente con lo que son la mayoría de las mujeres y hombres, pero son compartidas por un gran número de personas. Connell (2002) describió otras formas de masculinidad: las masculinidades subordinadas que se basan en su identificación con la feminidad. El rango de formas adoptadas por la masculinidad se determina parcialmente por la interacción entre el género y otras variables como el grupo étnico o la clase social (Curington, Lin, & Lundquist, 2015).

2. Materiales y método

Nuestra investigación se desarrolló entre diciembre de 2012 y noviembre de 2014 en cinco ciudades distintas simultáneamente: Londres, Roma, Bucarest, Bruselas y Barcelona/Tarragona. El diseño metodológico seguido permitió obtener información acerca de cómo las expresiones de discriminación son transformadas, de manera consciente e inconsciente, para adaptarse al entorno de Internet.

La metodología consistió en el análisis de los discursos de los contenidos recogidos a partir de la creación de 15 perfiles de Facebook (3 por ciudad) y 50 amistades por perfil (tabla 1). Estos tres perfiles se construyeron de acuerdo con la posición de los participantes en el sistema educativo (estudiantes de universidad, de educación secundaria y jóvenes que ni estudian ni trabajan). Para asegurar la libre participación de los participantes en el proyecto y que fueran conscientes de lo que ello implicaba, cada nuevo «amigo» recibió un mensaje del perfil con información acerca del proyecto, la metodología y la garantía de protección de datos.

El número final de participantes fue de 493, y la muestra final estuvo formada por un 65% de mujeres y un 35% de hombres (tabla 2). Diversos factores explican este hecho: las mujeres pueden ser más cercanas a las organizaciones que participaban en el proyecto o más proclives a participar en un proyecto enfocado a trabajar sobre aspectos discriminatorios. De todos modos, estos valores presentan una distribución similar por géneros a la existente en Facebook (Dugan & Brenner, 2013). La mayoría de participantes en la muestra tenían edades comprendidas entre los 17 y los 24 años. Pese a que el concepto de juventud es amplio y poco definido en sus extremos, generalmente se sitúa entre los 16 y los 30 años.

A partir del análisis de la información que los 493 participantes colgaban en Facebook, se detectaron contenidos que fueron considerados discriminatorios y, para cada ítem detectado, se procedió a su descripción y categorización. Siguiendo esta metodología, se recogieron, describieron y categorizaron 363 ejemplos de contenidos discriminatorios.

Se pidió a cada investigador la evaluación de la intensidad de los contenidos discriminatorios mediante una escala subjetiva Likert de 1 (poco discriminatorio) a 5 (muy discriminatorio). Se desarrolló un test de consistencia interna para comprobar la dispersión de los resultados de los investigadores participantes, miembros de las ONG que trabajan sobre la prevención de la discriminación. El test Rho de Spearman ofreció elevadas correlaciones entre todos los miembros del equipo de investigación (para 9 de las 10 combinaciones posibles), lo que señaló una importante consistencia interna en relación con el criterio evaluativo seguido por el equipo de investigación, validando la utilización de la escala de discriminación como instrumento analítico.

3. Análisis y resultados

3.1. Intensidad de la discriminación

Encontramos diferencias significativas al cruzar los datos de la escala de discriminación. Los contenidos discriminatorios colgados por los jóvenes que ni estudian ni trabajan y los estudiantes de secundaria fueron significativamente más intensos que los obtenidos por los estudiantes universitarios. Significativamente también, los ejemplos de discriminación colgados por mujeres fueron menos intensamente discriminatorios que los colgados por hombres. Estos datos señalan la existencia de diferencias en función del nivel educativo y el género: los hombres jóvenes con menos estudios pueden ser considerados como el grupo más discriminatorio, mientras que las mujeres universitarias, el que menos (tabla 3).

El test chi-cuadrado ofreció resultados significativos al cruzar el género y la escala de discriminación (42.5 y a=0,000 para un nivel de confianza del 95%) y con el tipo de discriminación (66.8 y a=0,000 para el mismo nivel de confianza).

Algunos de los tipos de discriminación fueron considerados más intensos por etnia o religión siguiendo la escala de discriminación. La discriminación por razón de género ocupó una posición intermedia, mientras que la discriminación por apariencia física, clase social o por razón de homosexualidad obtuvo valores más bajos. Los tipos de discriminación que suelen ser socialmente penalizados y considerados incorrectos obtuvieron también, valores más elevados en la escala de discriminación. La escala de discriminación propuesta dependió, finalmente, de la aproximación subjetiva de cada individuo respecto de la realidad analizada, reproduciendo en las evaluaciones aquellos elementos que son considerados como más discriminatorios. Los tipos de discriminación más intensos son fáciles de detectar, apuntando a la necesidad de trabajar en los tipos de discriminación que se salen de «los habituales», y que necesitan ser mucho más agresivos y explícitos para obtener consideraciones similares. Esta diferencia entre los distintos tipos de discriminación aportó ideas para entender la fácil difusión de ciertos contenidos. El mismo Facebook permite etiquetar ciertos contenidos como inapropiados y eliminarlos, pero si los usuarios tan sólo detectan las formas tradicionales de discriminación, el resto puede pervivir con facilidad.

Las tablas 3 y 4 muestran que la discriminación por motivo de género es la más numerosa y presentan diferencias significativas en la forma en que hombres y mujeres utilizan contenidos discriminatorios: los hombres se concentran más en discriminar por razón de género y son más agresivos en sus comentarios. Las mujeres se centran en la apariencia física y la clase social, que representan formas de discriminación «light», de acuerdo con nuestra escala. Para una posterior clasificación de las expresiones individuales de discriminación, se crearon categorías para describir la difusión de los contenidos y comentarios discriminatorios:

a) «Like» a comentarios discriminatorios realizados por otros.

b) «Like» a contenidos discriminatorios colgados por otros.

c) Comentarios discriminatorios realizados por uno mismo.

d) Comentarios discriminatorios realizados por otros en su muro.

e) Enlaces a contenidos discriminatorios colgados por uno mismo.

f) Otras opciones.

Aplicando el principio de parsimonia (ofrecer las explicaciones más simples posibles sin perder información), se decidió reducir estas categorías a tres, en función de la persona sobre la que recae la acción:

a) Discriminación directa: el propio usuario crea/cuelga el contenido.

b) Discriminación indirecta: el usuario acepta contenido discriminatorio y ayuda a su difusión mediante sus acciones.

c) Otras.

Estas nuevas categorías muestran las diferencias de género y de grupo en relación con la acción desarrollada en Internet (tablas 5 y 6). Los estudiantes de educación secundaria, los jóvenes que ni estudian ni trabajan y los hombres tienden a crear o publicar sus propios contenidos, mientras que los estudiantes universitarios y las mujeres tienden a aceptar comentarios creados por otros. Esta diferencia refuerza la idea de que hombres y mujeres muestran diferencias en relación con los contenidos discriminatorios, llevando a aceptar la existencia de distintos patrones de comportamiento en Facebook.

Finalmente, el análisis global de los datos anteriormente presentados sugiere la existencia de múltiples proximidades entre las categorías de las variables del sistema. Para obtener información sobre la significancia y dirección de estas múltiples relaciones, llevamos a cabo un análisis de correspondencias múltiples3.

Los resultados muestran la existencia de dos dimensiones que explican el 85,8% de la varianza total (tabla 7). Las correlaciones de las variables con las dos dimensiones resultantes son significativas y permiten definir la primera dimensión a partir de la discriminación directa/indirecta y la intensidad, pudiendo ser entendidos a partir del género. La segunda dimensión se define por el tipo de discriminación. Estos resultados revelan la asociación de los hombres con una forma de proceder en relación a la discriminación, que se puede definir como agresiva, basada en la creación de contenidos discriminatorios directos, y dirigida hacia la etnia, el género y la religión. La actitud de las mujeres puede ser asociada con una menor agresividad, una relación indirecta con los contenidos discriminatorios y una mayor propensión a la apariencia física, la clase social y cultural y la homofobia.

4. Conclusiones y discusión

Tal y como indica Bernárdez-Rodal (2006: 81), «la estructura dicotómica de géneros alrededor de los ejes masculino/femenino ni desaparece ni cambia, a pesar de tener las condiciones ideales para ello. Pese a interactuar en el ciberespacio, el cuerpo sigue siendo importante. De un modo o de otro, la interacción sigue teniendo lugar a través suyo». El hecho de que Internet permita el abandono del cuerpo ha sido considerado, por lo menos por algunas teóricas feministas, como una oportunidad para la liberación femenina, puesto que las mujeres han estado tradicionalmente ligadas a su cuerpo. A pesar de ello, parece que los adolescentes, sean hombres o mujeres, no desean que esto suceda. El determinismo de género sigue siendo fundamental, a pesar que el «cuerpo» haya sido substituido por la «palabra».

Hemos mostrado cómo hombres y mujeres se expresan de modo diferente cuando interactúan en Facebook a partir de tres ejes: 1) en el tipo de discriminación; 2) en la escala de discriminación y 3) en la forma como se producen estas expresiones de discriminación. Se han combinado todas estas variables para encontrar correspondencias múltiples entre patrones masculinos y femeninos de comportamiento en las redes sociales y sus diferencias significativas. Éstas son suficientemente importantes como para poder hablar de comportamientos diferenciados en hombres y mujeres en Internet, así como para definir aproximaciones distintas en relación con la discriminación en las redes. De manera similar, Mascheroni y Ólafsson (2014) mostraron diferencias en relación con el uso de la privacidad, teniendo los hombres una mayor tendencia a tener perfiles abiertos, mientras que las mujeres tienden a tenerlos cerrados.

Los hombres tienden a realizar comentarios discriminatorios sobre el origen étnico, el género o las minorías culturales, mientras que las mujeres se centran en la apariencia física y la clase social o cultural. Los comentarios discriminatorios de los hombres tienden a ser más intensos, particularmente aquellos vinculados con el género, mientras que las mujeres tienden a realizar comentarios más suaves. En resumen, los hombres usan patrones directos de discriminación y las mujeres, indirectos.

En general, la discriminación se entiende y se modula en relación con el tema o el colectivo al que se dirige, siendo algunas categorías más fáciles de identificar que otras. La discriminación de origen étnico y de género ha sido tradicionalmente objeto de muchas campañas para llamar la atención acerca de su impacto. Por el contrario, otros tipos de discriminación han sido socialmente aceptados o han permanecido invisibles (como puede ser la clase social o la apariencia). En esta investigación se ha subrayado la importancia de las diferencias de género para entender la comprensión de estas actitudes discriminatorias. La intensidad, el tipo y la forma en la que se expresa la discriminación pueden estar ligadas al género. El hecho que los hombres obtengan valores más elevados para los tres ejes de este análisis puede ser entendido como un patrón de afirmación de la masculinidad durante la juventud.

Figura 1. Resultados del análisis de correspondencias múltiples.

Somos conscientes que esta investigación presenta algunos puntos débiles –como, por ejemplo, la delimitación de algunos conceptos o los límites del objeto de estudio–. A pesar de ello, los resultados muestran que la relación entre los jóvenes y las redes sociales debe ser un objeto de estudio en el futuro, siendo necesaria una aproximación más etnográfica al comportamiento de hombres y mujeres en la Red y los distintos usos del lenguaje y el poder.

Finalmente, no debemos olvidar que las redes sociales son un altavoz que permite visibilizar actitudes que son comunes en la juventud, que han sido tradicionalmente expresadas de manera individual en el entorno off-line. Las redes sociales permiten registrar estas actitudes en un espacio público o semipúblico y darles mayor alcance y permanencia. En el momento en que los jóvenes están colgando estos contenidos, sus patrones de expresión siguen determinados por las normas de comunicación cara a cara, no siendo generalmente conscientes de que estos contenidos no siguen las mismas normas y requieren de una mayor reflexión para evitar posibles impactos en otras personas o en su propio futuro.

Notas

1 Los y las jóvenes fueron informados sobre el impacto de su participación, de acuerdo con la legislación de cada país participante.

2 Los conceptos de enlace débil o fuerte fueron desarrollados como herramientas para describir las relaciones interpersonales en las redes sociales. Granovetter (1973) describió la fuerza de los enlaces inter-individuales como una combinación del tiempo invertido, la intensidad emocional, la intimidad y los servicios mutuos que caracterizan la relación. También subrayó el papel que los enlaces débiles juegan en promover la integración y la creación de comunidad. Para este autor, los enlaces débiles son indispensables para las oportunidades individuales.

3 El objetivo del ACM es la reducción de la complejidad del análisis holístico mediante la agrupación de datos en patrones de interpretación más simples. Crea unos ejes de coordenadas en los que se distribuye la información de acuerdo con la proximidad de las categorías.

Apoyos y agradecimientos

El proyecto I:CUD es un proyecto financiado por el Programa de Fundamental Rights and Citizenship de la Unión Europea, coordinado por CEPS Projectes Socials, Barcelona (www.asceps.org) y desarrollado por el grupo de investigación SBRlab de la Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona (www.sbrlab.com), Fundatia PACT, Bucarest (www.fundatiapact.ro), Pour la Solidarité, Bruselas (www.pourlasolidarite.eu), Collage Arts, Londres (www.collage-arts.org) y CIES, Roma (www.cies.it). Para más información sobre la investigación, proyecto y resultados, consultad el sitio web del proyecto: www.digitaldiscrimination.eu.

Referencias

Alvesson, M., & Billing, Y. (1997). Understanding Gender and Organizations. London: Sage Publications.

Amorós, C. (1994). Feminismo: igualdad y diferencia. México: UNAM.

Bernárdez-Rodal, A. (2006). A la búsqueda de una ‘habitación propia’: comportamiento de género en el uso de Internet y los chats en la adolescencia. Revista de Estudios de la Juventud, 73, 69-82. (http://goo.gl/8kXFfT) (30-07-2015).

Bortee, D.S. (2005). Presentation of Self on the Web: An Ethnographic Study of Teenage Girls. Education, Communication & Information, 5(1), 25-39. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14636310500061102

Bourdieu, P. (2000). Poder, derecho y clases sociales. Bilbao: Desclée de Brouwer.

Boyd, D. (2007). Why Youth Heart Social Network Sites: The Role of Networked Publics in Teenage Social Life. Cambridge: Berkman Centre for Internet & Society at Harvard University. Research Publication 2007-16. (http://goo.gl/bTm3NK) (30-07-2015).

Bringué, X., & Sádaba, C.C. (2011). Menores y redes sociales. Foro Generaciones Interactivas. Madrid: Fundación Telefónica.

Castells, M. (2001). Internet y la sociedad red. Lección inaugural del Programa de Doctorado sobre la sociedad de la información y el conocimiento. Barcelona: UOC. (http://goo.gl/Ga4Xs7) (30-07-2015).

Centola, D. (2015). The Social Origins of Networks and Diffusion. American Journal of Sociology, 120(5), 1295-1338. (http://goo.gl/Zhh0CT) (31-07-2015).

Connell, R.W. (1993). Gender and Power. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Connell, R.W. (2002). Gender Short Introductions. Cambridge: Polity Press, Blackwell Publishers.

Curington, C. V., Lin K-H., & Lundquist, J. H. (2015). Positioning Multiraciality in Cyberspace: Treatment of Multiracial Daters in an Online Dating Website. American Sociological Review 80, 764-788. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0003122415591268

Deaux, K., & Stewart, A. (2001). Framing Gendered Identities. In R.K. Unger (Ed.), Handbook of the Psychology of Women and Gender. Canada: John Wiley & Sons.

Dugan, M., & Brenner, J. (2013). The Demography of Social Media Users 2012. (http://goo.gl/IlfeUA) (12-07-2014).

Ellison, N.E., Stein?eld, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The Bene?ts of Facebook ‘Friends’: Social Capital and College Students Use of Online Social Network Sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1143-1168. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x

Espinar, E., & González-Río, M.J. (2009). Jóvenes en las redes sociales virtuales. Un análisis exploratorio de las diferencias de género. Feminismo/s, 14, 87-106. (http://goo.gl/5eCEXu) (30-07-2015)

Fenstermaker, S., & West, C. (2002). Doing Gender, Doing Difference: Inequality, Power and Institutional Change. New York: Routledge.

Fundación Pfizer (2009). La juventud y las redes sociales en Internet. Madrid: Fundación Pfizer. (https://goo.gl/3heSgn) (30-07-2015).

García, M.C., Alonso, J., & del Hoyo, M. (2013). La participación de los jóvenes en las redes sociales: finalidad, oportunidades y gratificaciones. Anàlisi, 48, 95-110. (https://goo.gl/qpYGKn) (30-07-2015).

Garton, L., Haythornthwaite, C., & Wellman, B. (1997). Studying Online Social Networks. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 3(1). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.111/j.1083-6101.1997.tb00062.x

Gómez, A.G. (2010). Lexical Encoding of Gender Relations and Identities. In R.M. Jiménez-Catalán (Coord.), Gender Perspectives on Vocabulary in Foreign and Second Languages (pp. 238-263). New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Granovetter, M.S. (1973). The Strength of Weak Ties. The American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1.360-1.380. (https://goo.gl/qhKbKs) (30-07-2015).

Haythornthwaite, C. (2005). Social Networks and Internet Connectivity Effects. Information, Community & Society, 8(2), 125-147. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13691180500146185

Haythornthwaite, C., & Wellman, H. (2002). The Internet in Everyday Life: An Introduction. In C. Haythornthwaite, & B. Wellman (Ed.), The Internet in Everyday Life (pp. 1-41). Malden: Blackwell Publishers.

Huffaker, D.A., & Calvert, S.L. (2005). Gender, Identity, and Language Use in Teenage Blogs. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 10(2). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2005.tb00238.x

Joinson, A.N. (2003). Understanding the Psychology of Internet Behaviour Virtual Worlds, Real Lives. Gales: Palgrave MacMillan.

Kadushin, C. (2013). Comprender las redes sociales. Teorías, conceptos y hallazgos. Madrid: CIS.

Lenhart, A. (2009). Adults and Social Network Websites (http://goo.gl/9rDtPq) (05-12-2013).

Livingstone, S., Haddon, L., Görzig, A., & Ólafsson, K. (2014). Children’s Online Risks and Opportunities: Comparative Findings from EU Kids Online and Net Children Go Mobile. London: LSE. (http://goo.gl/PhuQoa) (30-07-2015).

Manago, A.M., & al. (2008). Self-presentation and Gender on MySpace. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 29(6), 446-458. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2008.07.001

Martuccelli, D. (2002). Grammaires de l’individu. Paris: Gallimard.

Mascheroni, G., & Ólafsson, K. (2014). Net Children go Mobile: Risks and Opportunities. Milano: Educatt.

Quan-Haase, A., & Wellman, B. (2002). Capitalizing on the Net: Social Contact, Civic Engagement and Sense of Community. In C. Haythornthwaite, & B. Wellman (Ed.), The Internet in Everyday Life (pp. 291-324). Malden: Blackwell Publishers.

Rambaran, A., Dijkstra, J.K., Munniksma, A. & Cillessen, A. (2015). The Development of Adolescents’ Friendships and Antipathies: A Longitudinal Multivariate Network Test of Balance Theory. Social Networks, 43, 162-176. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2015.05.003

Rubin, G. (1975). The Traffic in Women: Notes on the ‘Political Economy’ of Sex. In R. Reiter (Ed.), Toward an Anthropology of Women (pp. 157-210). New York: Monthly Review Press (http://goo.gl/FwEc54) (30-07-2015).

Schneider, F., Feldmann, A., Krishnamurthy, B., & Willinger, W. (2009). Understanding Online Social Network Usage from a Network Perspective. Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM Conference on Internet, Measurement (pp. 35-48). New York: ACM. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/1644893.1644899

Stefanone, M.A., & Jang, C.Y. (2007). Writing for Friends and Family: The Interpersonal Nature of Blogs. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 13(1), 123-140. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00389.x

Steffes, E.M., & Burgee, L.E. (2009). Social Ties and Online Word of Mouth. Internet Research, 19(1), 42-59. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/10662240910927812

Stern, S.R. (2004). Expressions of Identity Online: Prominent Features and Gender Differences in Adolescents’ World Wide Web Home Pages. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 48(2). doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem4800_4

Thelwall, M. (2008). Social Networks, Gender, and Friending: An Analysis of MySpace Member Profiles. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 59(8), 1.321-1.330. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/asi.20835

Tortajada, I., Araüna, N., & Martínez, I. (2013). Advertising Stereotypes and Gender Representation in Social Networking Sites. Comunicar, 41(21), 177-186. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C41-2013-17

Urueña, A., Ferrari, A., Blanco, D., & Valdecasa, E. (2011). Las redes sociales en Internet, Observatorio Nacional de las Telecomunicaciones y de la Sociedad de la Información. (http://goo.gl/jxMYnF) (05-12-2014).

Valcárcel, A. (1994). Sexo y filosofía. Sobre la mujer y el poder. Barcelona: Anthropos.

Valkenburg, P.M., Schouten, A.P., & Peter, J. (2005). Adolescents’ Identity Experiments on the Internet. New Media & Society, 7, 383-402. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1461444805052282

Wellman, B., Haase, A.Q., Witte, J., & Hampton, K. (2001). Does the Internet Increase, Decrease, or Supplement Social Capital? Social Networks, Participation, and Community Commitment. American Behavioural Scientist, 45(3), 436-455. (http://goo.gl/oSYTZV) (30-07-2015).

Document information

Published on 31/12/15

Accepted on 31/12/15

Submitted on 31/12/15

Volume 24, Issue 1, 2016

DOI: 10.3916/C46-2016-07

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?