Amanda32507 (talk | contribs) |

Amanda32507 (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 177: | Line 177: | ||

=4. Discussion = | =4. Discussion = | ||

| − | The overall data of the study showed that giving frequent reminders may have led to a decrease in the evening electricity consumption. Although a statistically significant difference was observed between the control group and the frequent reminders group, it was difficult to confirm if it was from custodian behavior since other external factors interfered with data collection regarding lights. Figure 2 suggests that there was little change regarding the amount of lights on, showing no significance. Due to these other factors, the extent to which custodian behavior was altered when daily reminders were sent is unclear. This somewhat supports our hypothesis, since daily reminders had caused a statistically significant decrease in electricity, but it is hard to clearly confirm if the reminders were followed. The change in electricity did not align with a change in the percentage of lights on, with the exception of the third week, which had a very slight correlation. ANOVA was used to find significance differences with the p-values. These findings suggest that it is difficult to determine if turning off the lights had a major impact on custodian behavior in a New York Public High School setting, and that other factors need to be examined. In Figure 7, evening and overall electricity consumption were compared over the 30 days of the experiment. The data showed that changes in electricity consumption overnight correlated to changes in the total electricity consumption of the day. In addition, the electricity usage during evenings made up a significant portion of the total electricity used in the duration of the entire day meaning that a change in the electricity consumption during the evening may lead to a significant change in the overall electricity usage. | + | The overall data of the study showed that giving frequent reminders may have led to a decrease in the evening electricity consumption. Although a statistically significant difference was observed between the control group and the frequent reminders group, it was difficult to confirm if it was from custodian behavior since other external factors interfered with data collection regarding lights. Figure 2 suggests that there was little change regarding the amount of lights on, showing no significance. Due to these other factors, the extent to which custodian behavior was altered when daily reminders were sent is unclear. This somewhat supports our hypothesis, since daily reminders had caused a statistically significant decrease in electricity, but it is hard to clearly confirm if the reminders were followed. The change in electricity did not align with a change in the percentage of lights on, with the exception of the third week, which had a very slight correlation. ANOVA was used to find significance differences with the p-values. These findings suggest that it is difficult to determine if turning off the lights had a major impact on custodian behavior in a New York Public High School setting, and that other factors need to be examined. In Figure 7, evening and overall electricity consumption were compared over the 30 days of the experiment. The data showed that changes in electricity consumption overnight correlated to changes in the total electricity consumption of the day. In addition, the electricity usage during evenings made up a significant portion of the total electricity used in the duration of the entire day meaning that a change in the electricity consumption during the evening may lead to a significant change in the overall electricity usage. We hypothesis that the discrepancy between the lack of a significant difference in the lights and the significant difference in the electricity consumption could also be in part because of how the custodians might have become more vigilant of their actions and the surroundings when cleaning the classrooms. For instance, the computers in the computer room or the smartboards in the room might have been noticed as well, and were turned off along with the lights. Reminders to perform these actions might have also been distributed along with the reminders to turn off the lights of the classroom. The reminder to turn off the lights might have also been extended to other rooms within the school, including the teacher's lounge, principal's office, or other areas. |

During this study, several factors may have influenced the results of this experiment. The duration of the experiment was conducted during a number of school holidays, which were not included in the data. These holidays would cause various gaps in the study, as seen from the missing days on day 29 and 30. This caused inaccurate data as the electricity consumption was significantly lower due to almost no faculty/students being in the building. To compensate for such gaps, the duration of the experiment could be extended in future experiments. When the lights inside the classrooms were inspected, students and faculty were already present, which means that some classrooms might have been turned on prior to data collection. This could cause inaccuracy for reminders collecting (Table 2). To avoid this, the experiment could begin at an earlier time, prior to the arrival of students and faculty. The time of day at which the data was collected might contribute to the accuracy when inspecting classrooms since human error needs to be taken into consideration. To handle this issue, the individuals that are inspecting the classroom lights could sleep at an earlier time. Furthermore, night activities have been conducted within the school, which could have made the reminders less effective since lights may have been turned back on. For this reason specifically, permission was not granted to inspect the lights after the school day was over. To address this issue, further information on the night activities could be collected and considered when implementing reminders and observing the collected data. Additionally, there was no way of confirming that the supervisor told the custodians to turn off the lights. To handle this issue, the supervisor can be asked regularly to ensure that the reminders are distributed at the appropriate times. There was also no method to confirm if the custodians followed the reminders that were distributed. This potentially contributed to the difficulties previously mentioned regarding the cause of the electricity reduction. To handle this, custodians who received the reminder can be asked if any actions were taken to turn off the lights through email messages or a survey. There was also confusion regarding the rooms that should be inspected during the study. To handle this issue, there could be a more detailed review of what rooms in the school should be inspected prior to beginning the experiment. Seasonal factors such as the temperature might also influence the electricity expenditure, causing abnormal spikes in electricity usage. For example, in the beginning of the experiment, the temperature has started to get cold, causing the school to turn on heating creating huge spikes in electricity usage. These huge spikes would cause inaccuracy in the electricity usage. Due to these seasonal changes, some data from Figure 2 and 4 had to be removed due to a diastatic gap, which can be seen in Figure 7. Days 1-4 had to be removed due to the implementation of heating on Day 5 of the experiment. Day 29 and 30 were removed due to school holidays, when no classes were in session. To avoid this, the experiement can start at the beginning or end of a season, such as the beginning of fall or the end of spring, could help account for these abnormal spikes. In addition, it is difficult to conduct further trials to determine whether the results found were accurate. For instance, it was difficult to conduct a second trial since the behavior of the custodians could have been permanently altered, meaning that the initial conditions of the study would be difficult to replicate. To resolve this issue, future studies could explore different schools and observe results obtained from these schools. These studies could also determine if the implementation of energy efficient behavior reminders led to the results obtained in this study. Future studies can address this by exploring the effects of these reminders in a different school with similar conditions. | During this study, several factors may have influenced the results of this experiment. The duration of the experiment was conducted during a number of school holidays, which were not included in the data. These holidays would cause various gaps in the study, as seen from the missing days on day 29 and 30. This caused inaccurate data as the electricity consumption was significantly lower due to almost no faculty/students being in the building. To compensate for such gaps, the duration of the experiment could be extended in future experiments. When the lights inside the classrooms were inspected, students and faculty were already present, which means that some classrooms might have been turned on prior to data collection. This could cause inaccuracy for reminders collecting (Table 2). To avoid this, the experiment could begin at an earlier time, prior to the arrival of students and faculty. The time of day at which the data was collected might contribute to the accuracy when inspecting classrooms since human error needs to be taken into consideration. To handle this issue, the individuals that are inspecting the classroom lights could sleep at an earlier time. Furthermore, night activities have been conducted within the school, which could have made the reminders less effective since lights may have been turned back on. For this reason specifically, permission was not granted to inspect the lights after the school day was over. To address this issue, further information on the night activities could be collected and considered when implementing reminders and observing the collected data. Additionally, there was no way of confirming that the supervisor told the custodians to turn off the lights. To handle this issue, the supervisor can be asked regularly to ensure that the reminders are distributed at the appropriate times. There was also no method to confirm if the custodians followed the reminders that were distributed. This potentially contributed to the difficulties previously mentioned regarding the cause of the electricity reduction. To handle this, custodians who received the reminder can be asked if any actions were taken to turn off the lights through email messages or a survey. There was also confusion regarding the rooms that should be inspected during the study. To handle this issue, there could be a more detailed review of what rooms in the school should be inspected prior to beginning the experiment. Seasonal factors such as the temperature might also influence the electricity expenditure, causing abnormal spikes in electricity usage. For example, in the beginning of the experiment, the temperature has started to get cold, causing the school to turn on heating creating huge spikes in electricity usage. These huge spikes would cause inaccuracy in the electricity usage. Due to these seasonal changes, some data from Figure 2 and 4 had to be removed due to a diastatic gap, which can be seen in Figure 7. Days 1-4 had to be removed due to the implementation of heating on Day 5 of the experiment. Day 29 and 30 were removed due to school holidays, when no classes were in session. To avoid this, the experiement can start at the beginning or end of a season, such as the beginning of fall or the end of spring, could help account for these abnormal spikes. In addition, it is difficult to conduct further trials to determine whether the results found were accurate. For instance, it was difficult to conduct a second trial since the behavior of the custodians could have been permanently altered, meaning that the initial conditions of the study would be difficult to replicate. To resolve this issue, future studies could explore different schools and observe results obtained from these schools. These studies could also determine if the implementation of energy efficient behavior reminders led to the results obtained in this study. Future studies can address this by exploring the effects of these reminders in a different school with similar conditions. | ||

Revision as of 02:45, 20 August 2024

Abstract

Excessive electricity consumption negatively affects the economic growth of developing countries, and is a major cause of carbon emissions throughout the globe. The objectives of this study is to investigate how the use of energy efficient behavior reminder affects electricity conservation in a New York City Public High School. In this experiment, during the first 10 days of the experiment, custodians were not reminded to turn off lights. From Day 11-20, reminders were sent to custodians every Monday and Fridays to turn off the light. During Day 21-30, reminders were sent everyday to remind custodians to turn off the lights. The results showed daily reminders had a significant decrease in electricity consumption compared to when no reminders were sent, but there was no significant difference between the percentage of lights being on, making it difficult to confirm if the custodians followed the reminders. The reminder of turning off lights was not a major source of electricity consumption and other factors might have consumed a larger portion of electricity.. More schools should be studied in order to validate the results. Future studies/research can test the effects of energy saving behavior reminders on electricity conservation from turning off electronic devices, such as smart boards or computers, at the end of the day.

1. Introduction

1.1 Issues of Electricity Consumption

Electricity contributes greatly to carbon emissions. Carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gasses trap heat in the form of solar radiation within the atmosphere, leading to an increase in the global water temperature and overall global temperature (Raval & Ramanathan, 1989). An increase in global temperature can disrupt the equilibrium of Earth’s ecosystems, leading to adverse effects for both people and animals. For instance, as a result of increasing carbon dioxide levels, oceans have become more acidic. The increased acidity makes the ocean uninhabitable to marine life and upsets the balance of the ocean ecosystems (Cornwall, 2021).

In the U.S, 32% of the overall amount of carbon emissions came from electricity usage (EIA, U., 2020), making it an important factor to consider if the US wants to achieve net zero emissions by 2035 (Anonymous, 2023). It was also found that, in the EU, 20% of all carbon dioxide produced comes from electricity use, also making it important in curbing the carbon emissions in Europe (Eurostat, 2023).

Behavior, habits, and awareness relating to electricity usage plays a role in electricity conservation. One study revealed that providing feedback on electricity through a website led to a 15% reduction in electricity use in residential households (Vassileva et al., 2012). Another study found a 13% reduction in electricity usage when a feedback system that allowed office workers to compare electricity use with others was used (Gulbinas & Taylor, 2014). Therefore, it is clear that altering behavior can be an effective strategy to conserve electricity.

1.2 Purpose and hypothesis

This objective of this study is investigate the effects of energy efficient behavior reminders on energy conservation in a public high school setting. It was hypothesized that energy saving actions implemented through behavior will reduce electricity consumption in a high school setting when they are implemented daily. Schools, a major source of energy usage, contribute to a large amount of the current carbon dioxide output. This large contribution can be attributed to the fact that 12.5% of New York’s population is made up of students. (Anonymous, 2022) (US Census Bureau, 2023). In order to reduce energy consumption as well as the resulting carbon output, New York schools must decrease the amount of electricity used. By using a New York public high school as a model, the effectiveness of altering behavior on electricity use can be gauged in a public school setting and could potentially be applied to several public high schools both in and outside of New York.

1.3 Literature Review

There have been several studies that have attempted to reduce electricity usage or develop more environmentally friendly, energy efficient devices. For instance, it was found that by replacing compact fluorescent lamps (CFL) with light emitting diodes (LED), a 33-35% reduction in lighting energy expenditure can be seen. A further reduction of 13-15% can be seen if smart-LEDs were used instead of LEDs (Moadab et al., 2021). The reduction in electric lighting energy usage can lead to a decrease in carbon emissions. Several studies have also made improvements to heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems (HVAC). One such instance is the use of the Berkley Retrofitted and Inexpensive HVAC Testbed for Energy Efficiency (BRITE) on the Berkeley campus, which adjusts depending on temperature to prevent a room from overcooling. BRITE was found to be 30-70% more energy efficient compared to two-position control, another way HVAC is controlled (Aswani et al., 2011). Another example can be seen in the development of solar-powered air conditioners. Solar-powered air conditioners rely on solar energy, which does not result in the production of carbon dioxide. In addition, solar-powered air conditioners are more energy efficient than conventional air conditioners, providing an incentive for its use (Zheng et al., 2018). The development of environmentally friendly devices and the illustration that they work demonstrate that there is great potential in reducing the amount of electricity consumed.

While studies testing electricity depletion and behavior have been done, there are few instances where the impact of energy efficient behavior reminders on electricity consumption was investigated in a high school setting. Several studies have observed how habits such as turning off appliances (G. Kavulya, B. Becerik-Gerber, 2012) or one’s political ideology (Gromet et al., 2013) have influenced electricity conservation, but these were often done in offices or residential buildings and were not explored in a New York City public high school. This makes it important that a New York City public high school is investigated to determine whether or not a public high school setting needs to be viewed and regarded in a different light.

2. Methods

2.1 Preparation

Prior to sending any reminders, the amount of classrooms and room numbers were recorded onto an excel spreadsheet prior to the experiment. This was done to eliminate the process of skipping any classrooms and to keep the data collected as consistent as possible. Additionally, every sunday an email was sent to our AP Science coordinator to call the custodian's supervisor to relay the messages on specific days (Depending on the experimental group). The timing of the call is completely dependent on our AP Science coordinator. The custodian supervisor will then relay the message to the custodians.

2.2 Experimental Setup

From Days 1 to 10 of the experiment, there were no reminders sent to custodians. Following that, from Days 11 to 20, reminders were sent to custodians through direct contact every Friday and Monday. Then, from Days 21-30, reminders were sent to custodians through direct contact every school day. During the beginning of the school day, the amount of classrooms with light and smartboards on were recorded between 7:10 AM and 7:20 AM for 20-30 minutes. Other aspects were not included in this experiment. The control group consisted of no reminders to custodians throughout the whole duration of this experiment. The first experimental group consisted of reminders every Monday and Friday to turn off the lights and smartboards. The second experimental group consisted of reminders everyday to custodians on turning off lights and smartboards.

Table 1. Experimental Setup

| Time | Reminder Frequency | Content of Reminder |

| Day1 - Day 10

(control group) |

No | N/A |

| Day 11 - Day 20

(Experimental group 1) |

twice /week (Monday and Friday) | To turn off the lights |

| Day 21-30

(Experimental group 2) |

Weekday (Monday to Friday) | To turn off the lights |

2.3 Measurements/Data Collection

The electricity consumption was accessed from the website “[1]” and recorded onto a 4 GB USB drive. Every Friday, the website was accessed from an office on the first floor of the school. When assessing the website, it was crucial to select the correct school, time , and day of the data you are recording. Specifically, the elecricity comsumption was recorded in 15 minutes increments. After exporting onto the USB drive, it was then taken home and analyzed on Saturday. The data was then analyzed and put onto excel. After the experiment was over, the data was averaged out and compared to other experimental group by using the line/bar graph function on excel.

2.4 Safety

To ensure safety for the participants, when recording data on the number of rooms with either smartboard or light on, they were not allowed to touch anything in the room. A supervisor knew when the participants were performing the experiment in case of any incidents. Additionally, the participants moved carefully throughout the halls when observing classrooms.

2.5 Data Analysis

The amount of electricity, in kilowatt-hours, was accessed from the website “http://nuenergen.com” and recorded onto a 4 GB USB drive. The data on the percentage of classrooms and electricity consumption was stored in an excel spreadsheet. The mean and standard deviation was calculated using the function on excel. The percentage of lights was calculated by dividing the number of classrooms lights on with the total number of classrooms. The data was put into a line graph and the electricity consumption was put into another line graph. It was then compared to see if the impact of setting reminders can reduce electricity consumption. With the data, it was then put into ANOVA to find if there was a significant difference. ANOVA (Analysis of variance) was used on https://astatsa.com/OneWay_Anova_with_TukeyHSD/.

3. Results

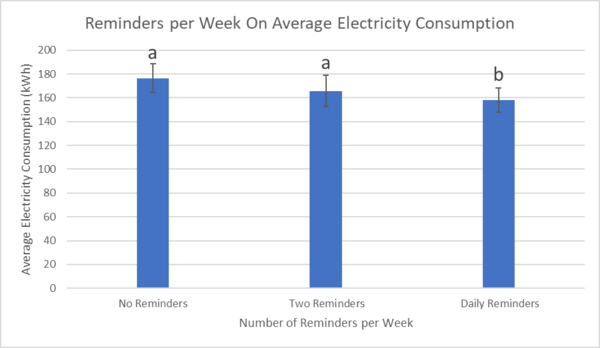

| Figure 1. The comparison between the reminders sent per week and the average electricity consumption from 6:00 PM to 7:15 AM.

Figure 1. The comparison between the reminders sent per week and the average electricity consumption from 6:00 PM to 7:15 AM. There are six days in the no reminders group, 10 days in the infrequent reminder group, and eight days in the daily reminders. The week with no reminders only consisted of six days because the first four days were discarded due to the sharp increase in electricity consumption on Day 5 as a result of heating. The daily reminders only consisted of 8 days because the last two days were on school holidays, where no classes were in session, which would result in a significant decrease in electricity consumption. The error bars represent the standard deviation. ANOVA with Tukey HSD was used to determine the significant difference. Daily reminders were significantly different compared to no reminders (labeled with different letters). The 2 reminders per week group are not statistically significant to the control group while the daily reminder group is statistically different from the control group. Groups labeled with the same letter (a) are not significantly different.

|

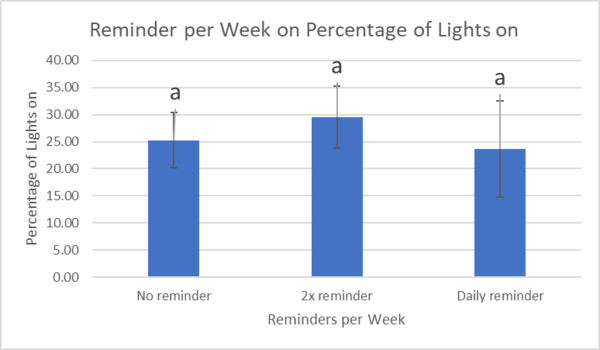

| Figure 2: The comparison between the reminders sent per week and the average percentage of lights on.

Figure 2. The comparison between the reminders sent per week and the average percentage of lights on. Each group consisted of 10 different values and was averaged. The error bars represent the standard deviation. ANOVA with Tukey HSD was used to determine the significant difference of experimental groups compared to the control group. The 2 reminders per week and daily reminder group are statistically similar to the control group. This suggests that reminders had no effect on the lights and that it is difficult to confirm if the reminders altered custodian behavior. Groups labeled with the same letter (a) are not significantly different.

|

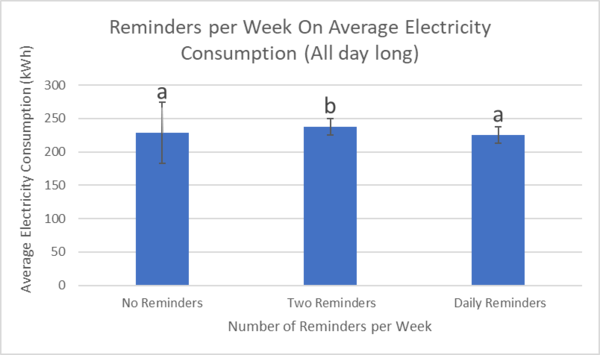

| Figure 3:The comparison between the reminders sent per week and the average electricity consumption for all day long

Figure 3. The comparison between the reminders sent per week and the average electricity consumption for all day long. There are six days in the no reminders groups, 10 days in the infrequent reminders group, and eight days in the daily reminders group. The no-reminders week only consisted of six days because the first four days were discarded due to the sharp increase in electricity consumption on Day 5 as a result of heating. The daily reminders only consisted of 8 days because the last two days were on school holidays, where no classes were in session, which would result in a significant decrease in electricity consumption. The error bars represent the standard deviation. ANOVA with Tukey HSD was used to determine the significant difference of experimental groups compared to the control group. The infrequent reminders group is statistically different to the control group (labeled with different letters) while the daily reminder group is not significantly different from the control group (labeled with the same letter).

|

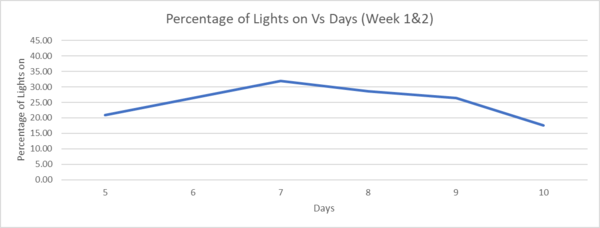

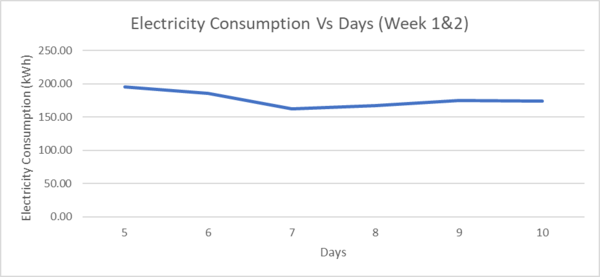

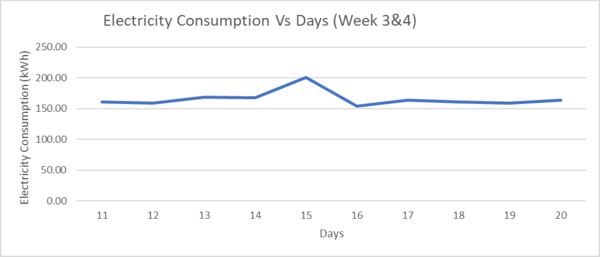

| Figure 4: Week 1&2 Comparison between Percentage of Lights on and Electricity Consumption (6:00 PM - 7:15 AM)

Figure 4. Week 1&2 Comparison between Percentage of Lights on and Electricity Consumption (6:00 PM - 7:15 AM). There was no reminder sent during the first ten days. The first four days were discarded due to the sharp increase in electricity consumption on Day 5 as a result of heating. The percentage of lights on does not correlate with the electricity consumption, since the rise or decrease in lights do not result in a rise or decrease in electricity consumption. This suggests that other factors play a more important role in electricity consumption. |

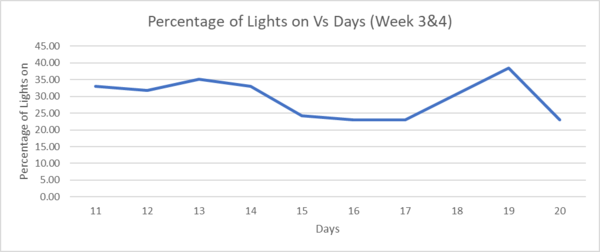

| Figure 5: Week 3&4 Comparison between Percentage of Lights on and Electricity Consumption (6:00 PM - 7:15 AM)

Figure 5. Week 3&4 Comparison between Percentage of Lights on and Electricity Consumption (6:00 PM - 7:15 AM). The back lines represent the days where reminders were sent from Days 11-20. Between Days 11-13, the percentage of lights on showed a slight correlation with the electricity consumption. After Day 13, there was no correlation between the percentage of light since the rise and decrease in the amount of lights was inconsistent with the rise or decrease in electricity consumption. This suggests that the lights do not play a major role in electricity consumption, and that other factors should be considered.

|

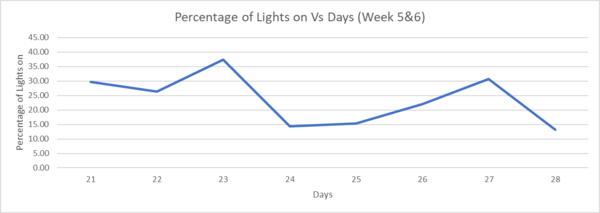

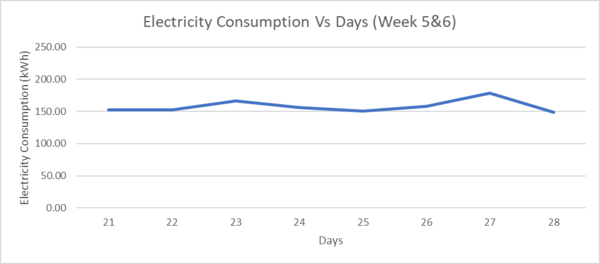

| Figure 6: Weeks 5&6 Comparison between Percentage of Lights on and Electricity Consumption (6:00 PM to 7:15 AM)

Figure 6. Weeks 5 & 6 comparison between the percentage of lights on and the electricity consumption during 6:00 PM to 7:15 AM. Daily reminders were sent everyday in this group. Days 29 and 30 were removed because no classes were in session due to school holidays, which resulted in a significant decrease in electricity consumption. The percentage of lights on has a slight correlation with the electricity consumption, with the spikes in the amount of lights on during Days 23 and 27 correlating with the slight spikes in electricity consumption on those same days. This suggests that the lights had a minor impact on the electricity consumption.

|

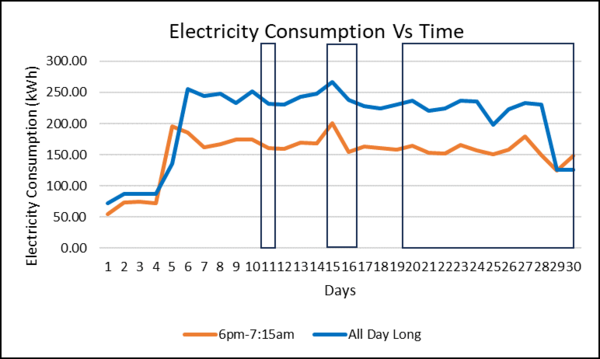

| Figure 7: Comparison of Electricity Consumption and Different Intervals of Time

Figure 7. Weeks 1-6 comparison between the percentage of lights on and the electricity consumption during 6:00 PM to 7:15 AM and all day long. The orange line represents the time from 12:00 AM to 12:00 AM of the next day. The blue line represents the time from 6:00 PM to 7:15 AM. Since the two lines correlate with each other, this will mean that the change in the evening affects the overall electricity consumption of the day considerably. The electricity used between 6 PM and 7:15 AM made up a sizable portion of the total electricity consumption. The boxed areas represent when the reminders were sent. |

4. Discussion

The overall data of the study showed that giving frequent reminders may have led to a decrease in the evening electricity consumption. Although a statistically significant difference was observed between the control group and the frequent reminders group, it was difficult to confirm if it was from custodian behavior since other external factors interfered with data collection regarding lights. Figure 2 suggests that there was little change regarding the amount of lights on, showing no significance. Due to these other factors, the extent to which custodian behavior was altered when daily reminders were sent is unclear. This somewhat supports our hypothesis, since daily reminders had caused a statistically significant decrease in electricity, but it is hard to clearly confirm if the reminders were followed. The change in electricity did not align with a change in the percentage of lights on, with the exception of the third week, which had a very slight correlation. ANOVA was used to find significance differences with the p-values. These findings suggest that it is difficult to determine if turning off the lights had a major impact on custodian behavior in a New York Public High School setting, and that other factors need to be examined. In Figure 7, evening and overall electricity consumption were compared over the 30 days of the experiment. The data showed that changes in electricity consumption overnight correlated to changes in the total electricity consumption of the day. In addition, the electricity usage during evenings made up a significant portion of the total electricity used in the duration of the entire day meaning that a change in the electricity consumption during the evening may lead to a significant change in the overall electricity usage. We hypothesis that the discrepancy between the lack of a significant difference in the lights and the significant difference in the electricity consumption could also be in part because of how the custodians might have become more vigilant of their actions and the surroundings when cleaning the classrooms. For instance, the computers in the computer room or the smartboards in the room might have been noticed as well, and were turned off along with the lights. Reminders to perform these actions might have also been distributed along with the reminders to turn off the lights of the classroom. The reminder to turn off the lights might have also been extended to other rooms within the school, including the teacher's lounge, principal's office, or other areas.

During this study, several factors may have influenced the results of this experiment. The duration of the experiment was conducted during a number of school holidays, which were not included in the data. These holidays would cause various gaps in the study, as seen from the missing days on day 29 and 30. This caused inaccurate data as the electricity consumption was significantly lower due to almost no faculty/students being in the building. To compensate for such gaps, the duration of the experiment could be extended in future experiments. When the lights inside the classrooms were inspected, students and faculty were already present, which means that some classrooms might have been turned on prior to data collection. This could cause inaccuracy for reminders collecting (Table 2). To avoid this, the experiment could begin at an earlier time, prior to the arrival of students and faculty. The time of day at which the data was collected might contribute to the accuracy when inspecting classrooms since human error needs to be taken into consideration. To handle this issue, the individuals that are inspecting the classroom lights could sleep at an earlier time. Furthermore, night activities have been conducted within the school, which could have made the reminders less effective since lights may have been turned back on. For this reason specifically, permission was not granted to inspect the lights after the school day was over. To address this issue, further information on the night activities could be collected and considered when implementing reminders and observing the collected data. Additionally, there was no way of confirming that the supervisor told the custodians to turn off the lights. To handle this issue, the supervisor can be asked regularly to ensure that the reminders are distributed at the appropriate times. There was also no method to confirm if the custodians followed the reminders that were distributed. This potentially contributed to the difficulties previously mentioned regarding the cause of the electricity reduction. To handle this, custodians who received the reminder can be asked if any actions were taken to turn off the lights through email messages or a survey. There was also confusion regarding the rooms that should be inspected during the study. To handle this issue, there could be a more detailed review of what rooms in the school should be inspected prior to beginning the experiment. Seasonal factors such as the temperature might also influence the electricity expenditure, causing abnormal spikes in electricity usage. For example, in the beginning of the experiment, the temperature has started to get cold, causing the school to turn on heating creating huge spikes in electricity usage. These huge spikes would cause inaccuracy in the electricity usage. Due to these seasonal changes, some data from Figure 2 and 4 had to be removed due to a diastatic gap, which can be seen in Figure 7. Days 1-4 had to be removed due to the implementation of heating on Day 5 of the experiment. Day 29 and 30 were removed due to school holidays, when no classes were in session. To avoid this, the experiement can start at the beginning or end of a season, such as the beginning of fall or the end of spring, could help account for these abnormal spikes. In addition, it is difficult to conduct further trials to determine whether the results found were accurate. For instance, it was difficult to conduct a second trial since the behavior of the custodians could have been permanently altered, meaning that the initial conditions of the study would be difficult to replicate. To resolve this issue, future studies could explore different schools and observe results obtained from these schools. These studies could also determine if the implementation of energy efficient behavior reminders led to the results obtained in this study. Future studies can address this by exploring the effects of these reminders in a different school with similar conditions.

Future studies could include the effects of energy efficient behavior reminders on the electricity consumption when turning off electronic devices such as smart boards or computers at the end of the day. For example, the experiment could have the same methodology as this experiment but instead of collecting the amount of lights that were on or off, it can collect the amount of computers and smartboard that were on or off at the beginning of the day. Additionally, the effect of energy efficient behavior reminders on the electricity consumption when using air conditioners in classrooms could also be explored. For example, the experiment could have the same methodology as this experiment but instead of collecting the amount of lights that were on or off, it would collect the usage of air conditioner/heating throughout the day. This can be collected through a google form where it asks teachers whether the AC or heating was used during each period/day. Furthermore, research could also investigate how reminders would affect the electricity consumption and amount of lights off over a longer duration of time. The methodology will be the same but instead of having 2 weeks per trial, it can range from 1 month to 2 months. However, there will be many seasonal factors that may affect the results. In addition, researchers could also investigate on why the reminders had lowered electricity consumption but didn't have an effect on custodians behavior. Future research can conduct extensive interviews with the custodian in the beginning and the end of the trial to get their insight when performing this experiment.

Conclusions

Figure 1 showed a p-value between the daily reminder and the control group of less than 0.05, suggesting that daily reminders resulted in a statistically significant reduction in electricity usage. In Figure 2, it was found that the use of reminders did not affect custodian behavior. Figure 3 demonstrated that when infrequent reminders were sent, there was a statistically significant increase in everyday electricity consumption. This may be attributed to an external factor. In Figures 4 and 5, it was found that the amount of lights remained relatively consistent and had little effect on the total electricity consumption, further supporting that lights do not play a major role in electricity consumption In Figure 6, it was found that there was a slight correlation between the amount of lights on and the average electricity consumption, meaning that when daily reminders to turn off the lights are implemented, electricity consumption can be decreased. Due to the small changes observed in the electricity consumption compared to the change in the lights, it is likely that any effects on the lights had minimal effects on the overall usage of electricity. Figure 7 is an accumulation of all the electricity consumption throughout each day of the experiment, which compares the electricity consumption overnight to the whole day. It was found that changes in electricity consumption overnight correlated to the changes in electricity consumption throughout the whole day and made up a large amount of the total electricity used during the whole day, meaning that any changes affecting electricity use overnight might have similar and meaningful effects on the overall electricity usage. Due to the possibility of a false positive, this study should be conducted in different schools of similar sizes and populations to clearly determine if the relationship between reminders and electricity consumption is genuine.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. D. Marmor, Mrs. N. Jaipershad, Dr. L. Wang, Dr. B.A.B. Blackwell, Dr. J. Cohen,

Dr. S. Lin, Mr. Z. Liang, Mrs. C. Rastetter, Ms. Amy and Ms. DePietro and the FLHS Science Research Program.

References

Abdallah, L., & El-Shennawy, T. (2013). Reducing carbon dioxide emissions from electricity sector using smart electric grid applications. Journal of Engineering, 2013.

Aksoezen, M., Daniel, M., Hassler, U., & Kohler, N. (2015). Building age as an indicator forenergy consumption. Energy and Buildings, 87, 74-86.

Anonymous. (2023, April 19). National Climate Task Force. The White House [https://www.whitehouse.gov/climate/#:~:text=Reducing%20Emissions%20and%20Accelerating%20Clean%20Energy

Anonymous, 2022. DOE Data at a Glance. NYC Department of Education. Accessed: January 18, 2023. https://www.schools.nyc.gov/about-us/reports/doe-data-at-a-glance

Aswani, A., Master, N., Taneja, J., Culler, D., & Tomlin, C. (2011). Reducing transient and steady state electricity consumption in HVAC using learning-based model-predictive control. Proceedings of the IEEE, 100(1), 240-253.

Cornwall, C. E., Comeau, S., Kornder, N. A., Perry, C. T., van Hooidonk, R., DeCarlo, T. M., ... & Lowe, R. J. (2021). Global declines in coral reef calcium carbonate production under ocean acidification and warming. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(21), e2015265118.

EIA, U. (2020). How much of US carbon dioxide emissions are associated with electricity Generation. [https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=77&t=11#:~:text=In%202022%2C%20the%20U.S.%20electric,sector%20accounted%20for%20about%2031%25

Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). EPA. Climate change indicators: U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-us-greenhouse-gas- emissions#:~:text=In%202020%2C%20U.S.%20greenhouse%20gas,pounds)%20of%20carbon%20dioxide%20equivalents

Eurostat. (2023, May 15). EU economy greenhouse gas emissions: -4% in Q4 2022. Eurostat News. [https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20230515-2

Gromet, D. M., Kunreuther, H., & Larrick, R. P. (2013). Political ideology affectsenergy-efficiency attitudes and choices. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(23), 9314-9319.

IEA. (2023, February 1). Methane emissions remained stubbornly high in 2022 even as soaring energy prices made actions to reduce them cheaper than ever - news. IEA. [https://www.iea.org/news/methane-emissions-remained-stubbornly-high-in-2022-even-as-soaring-energy-prices-made-actions-to-reduce-them-cheaper-than-ever

Kavulya, G., & Becerik-Gerber, B. (2012). Understanding the influence of occupant behavior on energy consumption patterns in commercial buildings. In Computing in Civil Engineering (2012) (pg. 569-576).

Moadab, N. H., Olsson, T., Fischl, G., & Aries, M. (2021). Smart versus conventional lighting in apartments-Electric lighting energy consumption simulation for three different households. Energy and Buildings, 244, 111009.

Raval, A., & Ramanathan, V. (1989). Observational determination of the greenhouse effect.Nature, 342(6251), 758-761.

Rimas Gulbinas, et al. “Effects of Real-Time Eco-Feedback and Organizational Network Dynamics on Energy Efficient Behavior in Commercial Buildings.” Energy and Buildings, Elsevier, 23 Aug. 2014, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378778814006598.

U.S. Census Bureau quickfacts: New York City, New York. (n.d.). Retrieved March 20, 2023, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/newyorkcitynewyork

Vassileva, I., Odlare, M., Wallin, F., & Dahlquist, E. (2012). The impact of consumers’ feedback preferences on domestic electricity consumption. Applied Energy, 93, 575-582.

World Bank Group. (2022, October 12). China’s transition to a low-carbon economy and climate resilience needs shifts in resources and technologies. World Bank. [https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/10/12/china-s-transition-to-a-low-carbon-economy-and-climate-resilience-needs-shifts-in-resources-and-technologies

Zheng, L., Zhang, W., Xie, L., Wang, W., Tian, H., & Chen, M. (2019). Experimental study on the thermal performance of solar air conditioning system with MEPCM cooling storage. International Journal of Low-Carbon Technologies, 14(1), 83-88.

Document information

Published on 09/02/26

Submitted on 04/07/24

Volume 8, 2026

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?