Qzone 1968 (talk | contribs) |

Qzone 1968 (talk | contribs) m (Following the same Model template for consistency of all published manuscripts in this journal.) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

<!-- metadata commented in wiki content | <!-- metadata commented in wiki content | ||

| − | = Evaluation of the Mechanical performance of HMA containing PET plastic and CHA as a filler material = | + | == Evaluation of the Mechanical performance of HMA containing PET plastic and CHA as a filler material == |

| − | <sup>1</sup>Nahusenay M. TESSERA, <sup>2</sup>Emer T. QUEZON, <sup>1</sup>Thomas BEZABIH | + | ===<sup>1</sup>Nahusenay M. TESSERA, <sup>2</sup>Emer T. QUEZON, <sup>1</sup>Thomas BEZABIH=== |

| − | == Abstract == | + | === Abstract === |

In road construction, various materials are used in the production of hot mix asphalt (HMA). Among them, bitumen and filler materials play a major role in the mechanical behavior of HMA. Bitumen properties and filler material govern HMA pavement performance. HMA pavements are associated with extremely high-temperature and high-traffic volume conditions, which can cause rutting, fatigue cracking, and permanent deformation. Pavement distress shortens service life and increases maintenance costs. This research focused on enhancing pavement resistance to distress by modifying the properties of bitumen with Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) plastic and utilizing alternative fillers, such as coffee husk ash (CHA). In this study, two phases were used. The first phase involved collecting samples, and the second phase consisted of three sub-phases. To design a material quality test, the first step was to develop a Marshal mix design and three types of mixtures: a mixture of normal HMA with SD filler, a mixture of normal HMA with CHA filler, and a combination of CHA filler and 3%, 6%, 9%, and 12% PET plastic. Marshal mix was used to analyze the marshal and volumetric properties of HMA pavement. According to the Marshall test, the CHA filler exhibits better performance than the SD filler in HMA mixtures. At 6.8% optimum PET plastic higher stability (15.9KN) and density value (2.268g/cm<sup>3</sup>) and lower flow (2.96mm), VMA (14.83%), and VFA value (73.01%) as compared with unmodified bitumen of 14.30KN, 3.5mm, 2.256g/cm<sup>3</sup>, 15.62%, and 75.06% value respectively at 4% air void provided. Therefore, the evaluation showed that the HMA containing a combination of 6.8% PET plastic and 3.2% CHS filler shows better mechanical performance in terms of Marshall stability and the volumetric properties of HMA. | In road construction, various materials are used in the production of hot mix asphalt (HMA). Among them, bitumen and filler materials play a major role in the mechanical behavior of HMA. Bitumen properties and filler material govern HMA pavement performance. HMA pavements are associated with extremely high-temperature and high-traffic volume conditions, which can cause rutting, fatigue cracking, and permanent deformation. Pavement distress shortens service life and increases maintenance costs. This research focused on enhancing pavement resistance to distress by modifying the properties of bitumen with Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) plastic and utilizing alternative fillers, such as coffee husk ash (CHA). In this study, two phases were used. The first phase involved collecting samples, and the second phase consisted of three sub-phases. To design a material quality test, the first step was to develop a Marshal mix design and three types of mixtures: a mixture of normal HMA with SD filler, a mixture of normal HMA with CHA filler, and a combination of CHA filler and 3%, 6%, 9%, and 12% PET plastic. Marshal mix was used to analyze the marshal and volumetric properties of HMA pavement. According to the Marshall test, the CHA filler exhibits better performance than the SD filler in HMA mixtures. At 6.8% optimum PET plastic higher stability (15.9KN) and density value (2.268g/cm<sup>3</sup>) and lower flow (2.96mm), VMA (14.83%), and VFA value (73.01%) as compared with unmodified bitumen of 14.30KN, 3.5mm, 2.256g/cm<sup>3</sup>, 15.62%, and 75.06% value respectively at 4% air void provided. Therefore, the evaluation showed that the HMA containing a combination of 6.8% PET plastic and 3.2% CHS filler shows better mechanical performance in terms of Marshall stability and the volumetric properties of HMA. | ||

| Line 22: | Line 21: | ||

'''License:''' This article is published under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license. | '''License:''' This article is published under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license. | ||

| − | |||

| − | = 1. Introduction = | + | |

| + | == 1. Introduction == | ||

Road networks make a significant contribution to a country's socio-economic activity. It is directly associated with the movement and accessibility of communities to use the road networks. (Obeta & Njoku, 2016). Ethiopia has approximately 110,414 km of roads spread throughout the country, comprising 14,055 km of flexible pavement road networks. (Road sector development program, 2015). It comprises subgrade, base course, subbase, and surface course layers (Babu, 2016; Flamarz Al-Arkawazi, 2017). Flexible pavement defects are caused by the quality and proportion of the material, affecting the performance of the HMA pavement structure (A. R. Prasad & Sowmya, 2015). The common types of pavement defects include rutting, cracking, depression, potholes, and raveling. These failures result from external conditions, such as traffic volume or load-associated factors and environmental influences, or non-load-associated factors, and internal conditions, including the quality and proportion of the material. (Ahmad et al., 2017; Aodah et al., 2012; Aziz et al., 2015; Hafeez et al., 2013). | Road networks make a significant contribution to a country's socio-economic activity. It is directly associated with the movement and accessibility of communities to use the road networks. (Obeta & Njoku, 2016). Ethiopia has approximately 110,414 km of roads spread throughout the country, comprising 14,055 km of flexible pavement road networks. (Road sector development program, 2015). It comprises subgrade, base course, subbase, and surface course layers (Babu, 2016; Flamarz Al-Arkawazi, 2017). Flexible pavement defects are caused by the quality and proportion of the material, affecting the performance of the HMA pavement structure (A. R. Prasad & Sowmya, 2015). The common types of pavement defects include rutting, cracking, depression, potholes, and raveling. These failures result from external conditions, such as traffic volume or load-associated factors and environmental influences, or non-load-associated factors, and internal conditions, including the quality and proportion of the material. (Ahmad et al., 2017; Aodah et al., 2012; Aziz et al., 2015; Hafeez et al., 2013). | ||

| Line 41: | Line 40: | ||

In this study, coffee husk ash is used as a filler material. PET plastic serves as a bitumen modifier in the production of HMA mixtures due to its ready availability and relatively low cost in our country. Therefore, modification of HMA pavements using an alternative or local material is an essential objective. It enhances performance and service life while reducing the maintenance costs of the road (Mosa, 2017). | In this study, coffee husk ash is used as a filler material. PET plastic serves as a bitumen modifier in the production of HMA mixtures due to its ready availability and relatively low cost in our country. Therefore, modification of HMA pavements using an alternative or local material is an essential objective. It enhances performance and service life while reducing the maintenance costs of the road (Mosa, 2017). | ||

| − | =2. Materials and Research Methods= | + | ==2. Materials and Research Methods== |

| − | ==2.1. Study Area== | + | ====2.1. Study Area==== |

The study was conducted at the Yirgalem Construction PLC laboratory in Hawassa, Ethiopia, which was equipped with complete laboratory facilities for undertaking the necessary tests. Hawassa is the city of the Sidama region and is located about 275 km from Addis Ababa. It is approximately located between 7°02'51´´ N Latitude and 38°29'44´´ E Longitude, and at an average elevation of 1716m above mean sea level. | The study was conducted at the Yirgalem Construction PLC laboratory in Hawassa, Ethiopia, which was equipped with complete laboratory facilities for undertaking the necessary tests. Hawassa is the city of the Sidama region and is located about 275 km from Addis Ababa. It is approximately located between 7°02'51´´ N Latitude and 38°29'44´´ E Longitude, and at an average elevation of 1716m above mean sea level. | ||

| − | ==2.2. Materials== | + | ====2.2. Materials==== |

The raw materials used for the laboratory study include aggregate, stone dust (SD), and coffee husk ash (CHA) filler, Bitumen 60/70 penetration grade, and shredded PET plastic. The materials used for this study are described in <span id='cite-_Ref79697497'></span>[[#_Ref79697497|''Table 1'']]''.'' | The raw materials used for the laboratory study include aggregate, stone dust (SD), and coffee husk ash (CHA) filler, Bitumen 60/70 penetration grade, and shredded PET plastic. The materials used for this study are described in <span id='cite-_Ref79697497'></span>[[#_Ref79697497|''Table 1'']]''.'' | ||

| Line 81: | Line 80: | ||

Source: ''(Manju, 2017; Mosa, 2017; Nega et al., 2013; Sarir et al., 2019)'' | Source: ''(Manju, 2017; Mosa, 2017; Nega et al., 2013; Sarir et al., 2019)'' | ||

| − | ===2.2.1. Coffee husk ash as filler=== | + | ====2.2.1. Coffee husk ash as filler==== |

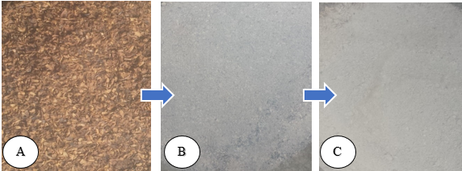

The dry coffee husk was collected from Yirgalem town in the Sidama region. It is located 255 Kilometers from Addis Ababa and 35 kilometers from Hawassa city. The coffee husk was burned in the furnace at 550 °C for 4 hours to produce ash, and after complete combustion, the ash was allowed to cool for an additional 24 hours. The burnt ash was collected and sieved through a 0.075mm sieve, and the fractions passing through the sieve were used throughout the test. The sieved ash was stored in a container to prevent moisture absorption. <span id='cite-_Ref79697824'></span>[[#_Ref79697824|''Figure 1'']] Shows the product obtained after processing coffee husk. | The dry coffee husk was collected from Yirgalem town in the Sidama region. It is located 255 Kilometers from Addis Ababa and 35 kilometers from Hawassa city. The coffee husk was burned in the furnace at 550 °C for 4 hours to produce ash, and after complete combustion, the ash was allowed to cool for an additional 24 hours. The burnt ash was collected and sieved through a 0.075mm sieve, and the fractions passing through the sieve were used throughout the test. The sieved ash was stored in a container to prevent moisture absorption. <span id='cite-_Ref79697824'></span>[[#_Ref79697824|''Figure 1'']] Shows the product obtained after processing coffee husk. | ||

| Line 93: | Line 92: | ||

Coffee husk is the primary residue or byproduct of coffee processing. According to the International Coffee Organization (2016), Ethiopia is the fifth-largest coffee producer in the world, with approximately 384,000 metric tons produced annually. From this production, approximately 192,000 metric tons of coffee husk residual, or by-product, are generated during the processing of coffee. The solid waste (coffee husk) is used as an extra for animal feed, but most of this waste, around 134,400 metric tons, is discarded, filled, and burned in the ground (Sime et al., 2017). By doing this, it can pollute the environment. Hence, proper use of this waste material can reduce storage requirements and mitigate environmental concerns associated with disposal. | Coffee husk is the primary residue or byproduct of coffee processing. According to the International Coffee Organization (2016), Ethiopia is the fifth-largest coffee producer in the world, with approximately 384,000 metric tons produced annually. From this production, approximately 192,000 metric tons of coffee husk residual, or by-product, are generated during the processing of coffee. The solid waste (coffee husk) is used as an extra for animal feed, but most of this waste, around 134,400 metric tons, is discarded, filled, and burned in the ground (Sime et al., 2017). By doing this, it can pollute the environment. Hence, proper use of this waste material can reduce storage requirements and mitigate environmental concerns associated with disposal. | ||

| − | ==2.3. Research Design== | + | ====2.3. Research Design==== |

The study employed an experimental research method to address the research question and achieve the objectives. The study work consists of two phases: the first phase involved sample collection. At this phase, Aggregate, Bitumen 60/70 penetration grade, coffee husk, and shredded PET plastic were collected. The second phase involved a laboratory test, which followed the procedures of ERA, AASHTO, and ASTM. This phase is further classified into two steps. Step I: Quality Testing - The quality of the aggregate and bitumen was tested, compared, and verified to ensure compliance with the ERA specification. Step II: Marshal Mix Design - During the marshal mix design step, three types of mixtures were designed. A mixture of normal HMA with stone dust as a filler, coffee husk ash as a filler, and a combination of 3.2% coffee husk ash filler by weight of aggregate and shredded PET plastic at 3, 6,9, and 12% with HMA. Finally, it calculated the stability, flow, and volumetric properties of the mixture, assessed these properties, and checked whether they are suitable as a wearing course material. The aggregate and asphalt quality tests are shown in <span id='cite-_Ref79699680'></span>[[#_Ref79699680|''Table 2'']]'' ''and <span id='cite-_Ref79699711'></span>[[#_Ref79699711|''Table 3'']]''.'' ''' ''' | The study employed an experimental research method to address the research question and achieve the objectives. The study work consists of two phases: the first phase involved sample collection. At this phase, Aggregate, Bitumen 60/70 penetration grade, coffee husk, and shredded PET plastic were collected. The second phase involved a laboratory test, which followed the procedures of ERA, AASHTO, and ASTM. This phase is further classified into two steps. Step I: Quality Testing - The quality of the aggregate and bitumen was tested, compared, and verified to ensure compliance with the ERA specification. Step II: Marshal Mix Design - During the marshal mix design step, three types of mixtures were designed. A mixture of normal HMA with stone dust as a filler, coffee husk ash as a filler, and a combination of 3.2% coffee husk ash filler by weight of aggregate and shredded PET plastic at 3, 6,9, and 12% with HMA. Finally, it calculated the stability, flow, and volumetric properties of the mixture, assessed these properties, and checked whether they are suitable as a wearing course material. The aggregate and asphalt quality tests are shown in <span id='cite-_Ref79699680'></span>[[#_Ref79699680|''Table 2'']]'' ''and <span id='cite-_Ref79699711'></span>[[#_Ref79699711|''Table 3'']]''.'' ''' ''' | ||

| Line 144: | Line 143: | ||

| − | ==2.4. Mixing of PET plastic with bitumen== | + | ====2.4. Mixing of PET plastic with bitumen==== |

The shredded PET plastic that passed through the 4.75mm sieve was used. The mixed aggregates were heated in a chamber at 180 °C. (ERA Manual, 2013) Recommend that the heated temperature of aggregate exceeded the compaction temperature of the asphalt mixture by a range of 10-300 °C, and use a temperature of 150 °C heated asphalt binder for 60/70 grade asphalt binder. Then the shredded PET plastic was put into the chamber and heated along with the aggregate. Until the plastic gets coated uniformly over the aggregate within 30min-45min, an oily coating was given to the aggregate mixture. Similarly, the asphalt was heated to a temperature of 150 °C (Chukka & Carr, 2016). When this process is applied to achieve good binding and prevent weak bonding, as the plastic exhibits a double binding property, it improves the surface properties of the aggregates. This process is practical in all types of climates, as the emission of toxic gases is not possible below 270 °C. When the plastic is heated above 270 °C, it decomposes, and above 750°C, it burns to produce toxic gases. The most important thing to keep in mind is monitoring the temperature. In the next step, the hot aggregate mix was mixed with the hot asphalt at a temperature between 140 °C - 170 <sup>0</sup>C (Bale, 2011). This dry process was employed in the Marshall mix design, incorporating the addition of shredded PET plastic (Appiah et al., 2016; Farhana et al., 2017; Movilla-Quesada et al., 2019; Sahu & Singh, 2016). | The shredded PET plastic that passed through the 4.75mm sieve was used. The mixed aggregates were heated in a chamber at 180 °C. (ERA Manual, 2013) Recommend that the heated temperature of aggregate exceeded the compaction temperature of the asphalt mixture by a range of 10-300 °C, and use a temperature of 150 °C heated asphalt binder for 60/70 grade asphalt binder. Then the shredded PET plastic was put into the chamber and heated along with the aggregate. Until the plastic gets coated uniformly over the aggregate within 30min-45min, an oily coating was given to the aggregate mixture. Similarly, the asphalt was heated to a temperature of 150 °C (Chukka & Carr, 2016). When this process is applied to achieve good binding and prevent weak bonding, as the plastic exhibits a double binding property, it improves the surface properties of the aggregates. This process is practical in all types of climates, as the emission of toxic gases is not possible below 270 °C. When the plastic is heated above 270 °C, it decomposes, and above 750°C, it burns to produce toxic gases. The most important thing to keep in mind is monitoring the temperature. In the next step, the hot aggregate mix was mixed with the hot asphalt at a temperature between 140 °C - 170 <sup>0</sup>C (Bale, 2011). This dry process was employed in the Marshall mix design, incorporating the addition of shredded PET plastic (Appiah et al., 2016; Farhana et al., 2017; Movilla-Quesada et al., 2019; Sahu & Singh, 2016). | ||

| Line 152: | Line 151: | ||

Marshall Stability test was used to determine the optimum bitumen content and evaluate the stability, flow, and volumetric properties of the HMA mixture. It is a peak load carried by a compacted sample at a test temperature of 60 °C. The flow value is the deformation at which the sample undergoes during the loading up to the peak load in a 0.25 mm unit (Ararsa et al., 2019; Sarkar, 2019; Yohannes et al., 2020). For this study, three scenarios were conducted. First, prepared HMA by a normal mix using stone dust filler. Second, prepared the HMA mixture, entirely replacing the stone dust filler with Coffee husk ash, i.e., 3.2% by weight of the total mix. Third, a combination of CHA and shredded PET plastic was prepared on the HMA. It was done by 3%, 6%, 9%, and 12% PET by weight of optimum bitumen content (OBC). The HMA mixture was tested, and the stability, flow, and volumetric properties were calculated according to the Marshall mix design. Their properties were assessed, and it was checked whether the properties are suitable as a wearing course material. | Marshall Stability test was used to determine the optimum bitumen content and evaluate the stability, flow, and volumetric properties of the HMA mixture. It is a peak load carried by a compacted sample at a test temperature of 60 °C. The flow value is the deformation at which the sample undergoes during the loading up to the peak load in a 0.25 mm unit (Ararsa et al., 2019; Sarkar, 2019; Yohannes et al., 2020). For this study, three scenarios were conducted. First, prepared HMA by a normal mix using stone dust filler. Second, prepared the HMA mixture, entirely replacing the stone dust filler with Coffee husk ash, i.e., 3.2% by weight of the total mix. Third, a combination of CHA and shredded PET plastic was prepared on the HMA. It was done by 3%, 6%, 9%, and 12% PET by weight of optimum bitumen content (OBC). The HMA mixture was tested, and the stability, flow, and volumetric properties were calculated according to the Marshall mix design. Their properties were assessed, and it was checked whether the properties are suitable as a wearing course material. | ||

| − | ===2.5.1 Marshal Mix preparation=== | + | =====2.5.1 Marshal Mix preparation===== |

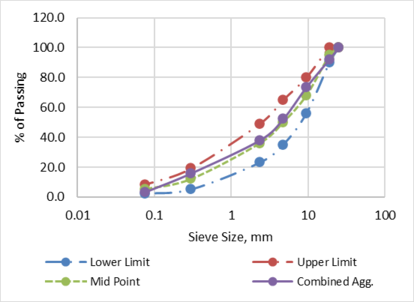

Before the marshal test, conducting the quality of bitumen and aggregate, then available aggregate materials, coarse aggregate (9.5mm-19mm), intermediate aggregate (4.75mm-9.5mm), fine aggregate (0-4.75mm), and filler, were integrated to get the proper gradation within the allowable limits according to ERA specifications using the trial and error method. The selected nominal maximum stone size was 19mm to consider a heavy traffic load. | Before the marshal test, conducting the quality of bitumen and aggregate, then available aggregate materials, coarse aggregate (9.5mm-19mm), intermediate aggregate (4.75mm-9.5mm), fine aggregate (0-4.75mm), and filler, were integrated to get the proper gradation within the allowable limits according to ERA specifications using the trial and error method. The selected nominal maximum stone size was 19mm to consider a heavy traffic load. | ||

| Line 166: | Line 165: | ||

After this, a marshaled mix was prepared by weighing the mixture, first calculating the percentage retained of each aggregate size in each sieve size, and then converting it into a retained weight for each fraction size. The retained weight on each fractional size in each sieve size is the product of the total weight of the HMA mixture, the percentage composition of each fraction, and the percentage retained of each size of aggregate. Then, finally, calculated the Retained Weight on each fraction size by the Weight of the Mixture (ERA Manual, 2013; MS-2 Asphalt Institute, 2014). | After this, a marshaled mix was prepared by weighing the mixture, first calculating the percentage retained of each aggregate size in each sieve size, and then converting it into a retained weight for each fraction size. The retained weight on each fractional size in each sieve size is the product of the total weight of the HMA mixture, the percentage composition of each fraction, and the percentage retained of each size of aggregate. Then, finally, calculated the Retained Weight on each fraction size by the Weight of the Mixture (ERA Manual, 2013; MS-2 Asphalt Institute, 2014). | ||

| − | ===2.5.2. Sample preparation=== | + | =====2.5.2. Sample preparation===== |

The mix design was handled by preparing three samples for each bitumen content. For all mixes, five different bitumen contents were selected by 0.5% increments. A sample consists of a combined aggregate weighing 1200 g. The aggregate and asphalt are then mixed at a temperature of 160–170 °C. The mixed samples were placed into a mold and compacted with 75 blows on each side by a 4.5kg hammer falling from 457mm height (MS-2 Asphalt Institute, 2014). From the total of forty samples prepared for the first, second, and third scenarios. In the first scenario, each sample with a weight of 1200 g was prepared using five different asphalt contents: 3.8%, 4.3%, 4.8%, 5.3%, and 5.8% by 0.5% increments, i.e., three samples for each asphalt content to obtain an average value. According to the ERA standard protocol (2013), first, the combined aggregate with SD filler and binding materials was heated to temperatures of 170-180 °C and 150 °C, respectively. Then, these ingredients were mixed at a temperature of 140-170 <sup>0</sup>C. MS-2 Asphalt Institute (2014) stated that the mixture was placed in the preheated mold and compacted at a temperature of 135-155 °C, using 75 blows on each side of the sample. The above procedure was repeated for the second scenario, with the only difference being that the stone dust filler was replaced with a coffee husk ash filler material. After obtaining OBC, the third scenario was done with the same procedures. Fifteen samples were prepared by considering four different proportions of PET shredded plastic, namely 3%, 6%, 9%, and 12% by weight of OBC, using a dry process method. | The mix design was handled by preparing three samples for each bitumen content. For all mixes, five different bitumen contents were selected by 0.5% increments. A sample consists of a combined aggregate weighing 1200 g. The aggregate and asphalt are then mixed at a temperature of 160–170 °C. The mixed samples were placed into a mold and compacted with 75 blows on each side by a 4.5kg hammer falling from 457mm height (MS-2 Asphalt Institute, 2014). From the total of forty samples prepared for the first, second, and third scenarios. In the first scenario, each sample with a weight of 1200 g was prepared using five different asphalt contents: 3.8%, 4.3%, 4.8%, 5.3%, and 5.8% by 0.5% increments, i.e., three samples for each asphalt content to obtain an average value. According to the ERA standard protocol (2013), first, the combined aggregate with SD filler and binding materials was heated to temperatures of 170-180 °C and 150 °C, respectively. Then, these ingredients were mixed at a temperature of 140-170 <sup>0</sup>C. MS-2 Asphalt Institute (2014) stated that the mixture was placed in the preheated mold and compacted at a temperature of 135-155 °C, using 75 blows on each side of the sample. The above procedure was repeated for the second scenario, with the only difference being that the stone dust filler was replaced with a coffee husk ash filler material. After obtaining OBC, the third scenario was done with the same procedures. Fifteen samples were prepared by considering four different proportions of PET shredded plastic, namely 3%, 6%, 9%, and 12% by weight of OBC, using a dry process method. | ||

| − | ===2.5.3. Volumetric Analysis=== | + | =====2.5.3. Volumetric Analysis===== |

The volumetric properties are determined using mass and volume measurements, as well as the constituent components, including a binder, aggregate, and air void. The relationship between mass and volume is determined by the material's specific gravity (G) (Yohannes et al., 2020). | The volumetric properties are determined using mass and volume measurements, as well as the constituent components, including a binder, aggregate, and air void. The relationship between mass and volume is determined by the material's specific gravity (G) (Yohannes et al., 2020). | ||

| Line 237: | Line 236: | ||

The Marshall test was used to determine the optimum binder content. Five different percentages of asphalt were examined to determine the optimum percentage for the aggregates used, including 3.8%, 4.3%, 4.8%, 5.3%, and 5.8% by weight of the mix, with three samples for each percentage. According to ERA Manual (2013)Define the OBC by determining the asphalt content corresponding to 4% air void, and fix the values of stability, density, flow, VMA, and VFA. The 2013 ERA specification, AASHTO, and other Countries' specifications, like those in the Philippines, generally state that the percentage of air void in the mixture is 3-5%. | The Marshall test was used to determine the optimum binder content. Five different percentages of asphalt were examined to determine the optimum percentage for the aggregates used, including 3.8%, 4.3%, 4.8%, 5.3%, and 5.8% by weight of the mix, with three samples for each percentage. According to ERA Manual (2013)Define the OBC by determining the asphalt content corresponding to 4% air void, and fix the values of stability, density, flow, VMA, and VFA. The 2013 ERA specification, AASHTO, and other Countries' specifications, like those in the Philippines, generally state that the percentage of air void in the mixture is 3-5%. | ||

| − | =3. Results and Discussion= | + | ==3. Results and Discussion== |

| − | + | ====3.1. Effect of fillers on the Marshal Properties of HMA mixture==== | |

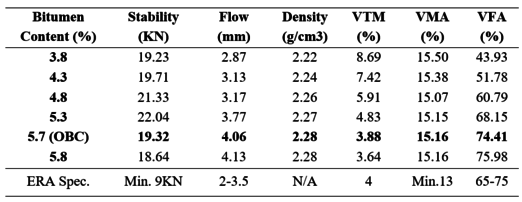

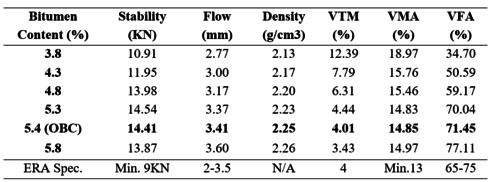

The results of Marshal Tests on bituminous mixes are prepared by using coffee husk ash (CHA) and stone dust filler (SD), and compared with each other at the same optimum percentage of 3.2% by weight of aggregate from the job mix formula. The relationships between binder content and the properties of mixtures From the test results, the optimum bitumen content (OBC), stability, flow, density, VTM, VMA, and VFA were selected and compared. <span id='cite-_Ref79701366'></span>[[#_Ref79701366|''Table 4'']]'', ''and <span id='cite-_Ref79701377'></span>[[#_Ref79701377|''Table 5'']] indicate the properties of the mixtures obtained for the two filler mixtures. | The results of Marshal Tests on bituminous mixes are prepared by using coffee husk ash (CHA) and stone dust filler (SD), and compared with each other at the same optimum percentage of 3.2% by weight of aggregate from the job mix formula. The relationships between binder content and the properties of mixtures From the test results, the optimum bitumen content (OBC), stability, flow, density, VTM, VMA, and VFA were selected and compared. <span id='cite-_Ref79701366'></span>[[#_Ref79701366|''Table 4'']]'', ''and <span id='cite-_Ref79701377'></span>[[#_Ref79701377|''Table 5'']] indicate the properties of the mixtures obtained for the two filler mixtures. | ||

| Line 255: | Line 254: | ||

[[Image:Draft_Quezon_352077040-image4.png|492px|alt='<spanid='_Toc76647910'></span>''3.1.1. Effect of filler on the Optimum Bitumen Content'''|<span id='_Toc76647910'></span>''3.1.1. Effect of filler on the Optimum Bitumen Content'']] </div> | [[Image:Draft_Quezon_352077040-image4.png|492px|alt='<spanid='_Toc76647910'></span>''3.1.1. Effect of filler on the Optimum Bitumen Content'''|<span id='_Toc76647910'></span>''3.1.1. Effect of filler on the Optimum Bitumen Content'']] </div> | ||

| − | + | =====3.1.1. Effect of filler on the Optimum Bitumen Content===== | |

<span id='cite-_Ref79701366'></span>[[#_Ref79701366|''Table 4'']] and <span id='cite-_Ref79701377'></span>[[#_Ref79701377|''Table 5'']] indicated that the corresponding OBC for the mix was found to be 5.7 and 5.4% at 4% air void with stone dust and coffee husk ash filler, respectively. This result explains that the OBC of the SD filler is higher by 0.3% than that of the CHA filler. To observe that the SD filler is finer than the CHA filler. This may occur because most of the Void between the aggregate skeleton in the mixture is excessively filled by SD filler, reducing the air void, which results in a denser pavement, increased stability, and reduced flexibility. Additionally, the SD filler absorbs more bitumen, leading to an increase in the OBC of the mixture. This occurred because SD filler has a higher surface area, allowing it to absorb more bitumen and form more asphalt-mastic, resulting in higher lateral flow compared with CHA filler. Due to this situation, the pavement becomes cracked, and permanent deformation occurs when heavy vehicles move on the pavement before the design period. | <span id='cite-_Ref79701366'></span>[[#_Ref79701366|''Table 4'']] and <span id='cite-_Ref79701377'></span>[[#_Ref79701377|''Table 5'']] indicated that the corresponding OBC for the mix was found to be 5.7 and 5.4% at 4% air void with stone dust and coffee husk ash filler, respectively. This result explains that the OBC of the SD filler is higher by 0.3% than that of the CHA filler. To observe that the SD filler is finer than the CHA filler. This may occur because most of the Void between the aggregate skeleton in the mixture is excessively filled by SD filler, reducing the air void, which results in a denser pavement, increased stability, and reduced flexibility. Additionally, the SD filler absorbs more bitumen, leading to an increase in the OBC of the mixture. This occurred because SD filler has a higher surface area, allowing it to absorb more bitumen and form more asphalt-mastic, resulting in higher lateral flow compared with CHA filler. Due to this situation, the pavement becomes cracked, and permanent deformation occurs when heavy vehicles move on the pavement before the design period. | ||

| − | + | =====3.1.2. Effect of filler on Marshal Stability and flow===== | |

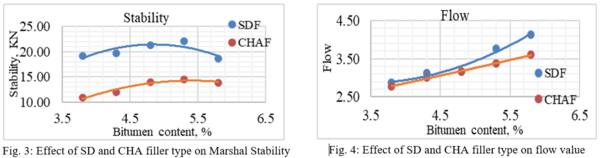

''Tables 4 and 5 ''found OBCs of 5.7% and 5.4% for the mixtures, which contain stone dust and coffee husk ash as filler materials. At these optimum values, the Stability and flow values were 19.32 KN, 4.06 mm, and 14.41 KN, 3.41 mm, respectively. <span id='cite-_Ref79703608'></span>[[#_Ref79703608|''Figure 3'']]'' ''show that the Marshall stability value obtained for stone dust and coffee husk ash filler is increased by 114.7% and 60.1%, respectively, from the minimum ERA specification (Min. 9KN) this is a much higher value compared with non-conventional filler (Coffee husk ash) because of stone dust fillers is highly finer than the coffee husk ash filler and extremely fill the Void between the aggregate skeleton in the mixture and increase the stability value besides non-conventional filler samples show optimum stability value (14.41 kN) compared to conventional filler(stone dust) samples (19.32 kN). Hence, the higher value of stability exhibited by a denser pavement results in a loss of flexibility, approaching a rigid state. Due to this situation, the pavement becomes cracked due to the brittleness of the mixture during its life period, and is permanently deformed by the heavy vehicles moving on it. Furthermore, <span id='cite-_Ref79703536'></span>[[#_Ref79703536|''Figure 4'']] shows that at 5.7% of OBC, the flow value of SD filler is 4.06 mm, which is out of the ERA specification (2-3.5%), and at 5.4% of OBC, the flow value of CHA filler is 3.41 mm, which is within the range of the specification. This effect occurs at higher temperatures, where the fine filler mixes with bitumen to form a highly flexible mastic asphalt pavement. As the pavement develops lateral movement, permanent deformation occurs when a heavy vehicle moves over it. | ''Tables 4 and 5 ''found OBCs of 5.7% and 5.4% for the mixtures, which contain stone dust and coffee husk ash as filler materials. At these optimum values, the Stability and flow values were 19.32 KN, 4.06 mm, and 14.41 KN, 3.41 mm, respectively. <span id='cite-_Ref79703608'></span>[[#_Ref79703608|''Figure 3'']]'' ''show that the Marshall stability value obtained for stone dust and coffee husk ash filler is increased by 114.7% and 60.1%, respectively, from the minimum ERA specification (Min. 9KN) this is a much higher value compared with non-conventional filler (Coffee husk ash) because of stone dust fillers is highly finer than the coffee husk ash filler and extremely fill the Void between the aggregate skeleton in the mixture and increase the stability value besides non-conventional filler samples show optimum stability value (14.41 kN) compared to conventional filler(stone dust) samples (19.32 kN). Hence, the higher value of stability exhibited by a denser pavement results in a loss of flexibility, approaching a rigid state. Due to this situation, the pavement becomes cracked due to the brittleness of the mixture during its life period, and is permanently deformed by the heavy vehicles moving on it. Furthermore, <span id='cite-_Ref79703536'></span>[[#_Ref79703536|''Figure 4'']] shows that at 5.7% of OBC, the flow value of SD filler is 4.06 mm, which is out of the ERA specification (2-3.5%), and at 5.4% of OBC, the flow value of CHA filler is 3.41 mm, which is within the range of the specification. This effect occurs at higher temperatures, where the fine filler mixes with bitumen to form a highly flexible mastic asphalt pavement. As the pavement develops lateral movement, permanent deformation occurs when a heavy vehicle moves over it. | ||

| Line 266: | Line 265: | ||

[[Image:Draft_Quezon_352077040-image5.png|600px|alt='<spanid='_Toc76647912'></span>''3.1.3. Effect of Filler on the Density of a Mixture'''|<span id='_Toc76647912'></span>''3.1.3. Effect of Filler on the Density of a Mixture'']] </div> | [[Image:Draft_Quezon_352077040-image5.png|600px|alt='<spanid='_Toc76647912'></span>''3.1.3. Effect of Filler on the Density of a Mixture'''|<span id='_Toc76647912'></span>''3.1.3. Effect of Filler on the Density of a Mixture'']] </div> | ||

| − | + | =====3.1.3. Effect of Filler on the Density of a Mixture===== | |

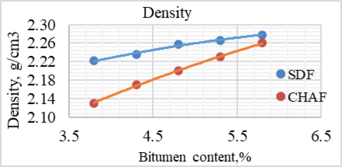

The result of both filler types on the unit weight of compacted mixes is shown in <span id='cite-_Ref79703456'></span>[[#_Ref79703456|''Figure 5'']]. It is shown that at 3.2% filler content, the CHA filler of a mixture possessed a slightly lower unit weight value (2.25 g/cm<sup>3</sup>) than the stone dust filler (2.28 g/cm<sup>3</sup>). This indicates that the size of the SD filler is finer and able to fill more Voids in the mix. Due to this, increase the density of the mixture as compared with the CHA filler. However, the mix becomes stiffer, which requires a more significant compaction effort (Bohara & Tamrakar, 2017). | The result of both filler types on the unit weight of compacted mixes is shown in <span id='cite-_Ref79703456'></span>[[#_Ref79703456|''Figure 5'']]. It is shown that at 3.2% filler content, the CHA filler of a mixture possessed a slightly lower unit weight value (2.25 g/cm<sup>3</sup>) than the stone dust filler (2.28 g/cm<sup>3</sup>). This indicates that the size of the SD filler is finer and able to fill more Voids in the mix. Due to this, increase the density of the mixture as compared with the CHA filler. However, the mix becomes stiffer, which requires a more significant compaction effort (Bohara & Tamrakar, 2017). | ||

| Line 276: | Line 275: | ||

<span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">Fig. 5: Effect of SD and CHA filler type on the Bulk specific gravity of the mixture</span></div> | <span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">Fig. 5: Effect of SD and CHA filler type on the Bulk specific gravity of the mixture</span></div> | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | =====3.1.4. Effect of filler on the Voids in Mineral Aggregate (VMA) and Voids Filled with Asphalt binder (VFA)===== | |

VMA indicates the available space for bitumen to coat each aggregate particle adequately, and VFA is the void space in the mineral aggregate that is filled with bitumen. This parameter describes the richness of a bituminous-bound mix (Mohammed & Fadhil, 2018). ERA Manual (2013) specifies that the minimum VMA is 13%, and the VFA value is in the range of 65% - 75%. This criterion plays a vital role in the durability of mixes and is linked to the effective bitumen content in the mix. If the percentage of VFA is lower than the limit shown, there is a lower bitumen film around the aggregate particles. Lower bitumen films are more susceptible to moisture and weather effects, which can cause them to separate from the aggregate particles, resulting in lower performance. On the other hand, if the limit is exceeded, more voids are filled with bitumen than required for durability. This can be explained as the asphalt film around aggregate particles is thicker, and lower voids are left than required. This increased amount of effective asphalt results in bleeding and lower stiffness of the mix (Tefera et al., 2018). <span id='cite-_Ref79704471'></span>[[#_Ref79704471|''Figure 6'']]'' ''illustrates the available space for bitumen to coat each aggregate particle adequately. The VMA values of SD and CHA filler (15.16% and 14.85%) are considerably 0.31%, slightly higher than those of CHA filler. This illustrates the difference in filler size between the two materials. In addition, <span id='cite-_Ref79704663'></span>[[#_Ref79704663|''Figure 7'']] exhibits the VFA value of SD and CHA fillers, which are 74.41% and 71.45%, respectively. This is also noticeably 2.96%, slightly higher than the CHA filler. However, there is no significant variation between the two filler materials in terms of VMA and VFA. Al-Shamsi et al. (2017) defined VMA as the intergranular void space in a compacted asphalt mix. It is the volume of air voids and the volume of effective asphalt, and is an important parameter in HMA mix design. It is said that an optimum VMA requirement is necessary to ensure adequate bitumen content and Durability for HMA. | VMA indicates the available space for bitumen to coat each aggregate particle adequately, and VFA is the void space in the mineral aggregate that is filled with bitumen. This parameter describes the richness of a bituminous-bound mix (Mohammed & Fadhil, 2018). ERA Manual (2013) specifies that the minimum VMA is 13%, and the VFA value is in the range of 65% - 75%. This criterion plays a vital role in the durability of mixes and is linked to the effective bitumen content in the mix. If the percentage of VFA is lower than the limit shown, there is a lower bitumen film around the aggregate particles. Lower bitumen films are more susceptible to moisture and weather effects, which can cause them to separate from the aggregate particles, resulting in lower performance. On the other hand, if the limit is exceeded, more voids are filled with bitumen than required for durability. This can be explained as the asphalt film around aggregate particles is thicker, and lower voids are left than required. This increased amount of effective asphalt results in bleeding and lower stiffness of the mix (Tefera et al., 2018). <span id='cite-_Ref79704471'></span>[[#_Ref79704471|''Figure 6'']]'' ''illustrates the available space for bitumen to coat each aggregate particle adequately. The VMA values of SD and CHA filler (15.16% and 14.85%) are considerably 0.31%, slightly higher than those of CHA filler. This illustrates the difference in filler size between the two materials. In addition, <span id='cite-_Ref79704663'></span>[[#_Ref79704663|''Figure 7'']] exhibits the VFA value of SD and CHA fillers, which are 74.41% and 71.45%, respectively. This is also noticeably 2.96%, slightly higher than the CHA filler. However, there is no significant variation between the two filler materials in terms of VMA and VFA. Al-Shamsi et al. (2017) defined VMA as the intergranular void space in a compacted asphalt mix. It is the volume of air voids and the volume of effective asphalt, and is an important parameter in HMA mix design. It is said that an optimum VMA requirement is necessary to ensure adequate bitumen content and Durability for HMA. | ||

| Line 284: | Line 283: | ||

[[Image:Draft_Quezon_352077040-image7.png|600px]] </div> | [[Image:Draft_Quezon_352077040-image7.png|600px]] </div> | ||

| − | + | ====3.2. The Effect of PET plastic on the Marshal Properties of HMA==== | |

| − | ===3.2.1. The Effect of PET on the Optimum Bitumen Content=== | + | =====3.2.1. The Effect of PET on the Optimum Bitumen Content===== |

<span id='_Toc76647916'></span>From <span id='cite-_Ref79701377'></span>[[#_Ref79701377|''Table 5'']]'' ''the corresponding OBC using coffee husk ash filler for the mix is 5.4% at 4% air void. After obtaining OBC, to assess the effect of adding shredded PET plastic to bitumen mixture samples by considering four different proportions of shredded plastic: 3%, 6%, 9%, and 12% of PET plastic by the weight of OBC <span id='cite-_Ref79701377'></span>[[#_Ref79701377|''Table 5'']]'' ''show that the percentage of PET plastic increased with decreased OBC and modifies the Marshal properties of a mixture. The combination of optimum PET plastic and bitumen content, at 6.8% by weight of OBC and 5.04% by weight of aggregate, with 4% air void, was the optimum value to achieve good performance of the mixture. This indicates that PET plastic is used as a bitumen modifier to achieve the ERA specification at this optimum level. | <span id='_Toc76647916'></span>From <span id='cite-_Ref79701377'></span>[[#_Ref79701377|''Table 5'']]'' ''the corresponding OBC using coffee husk ash filler for the mix is 5.4% at 4% air void. After obtaining OBC, to assess the effect of adding shredded PET plastic to bitumen mixture samples by considering four different proportions of shredded plastic: 3%, 6%, 9%, and 12% of PET plastic by the weight of OBC <span id='cite-_Ref79701377'></span>[[#_Ref79701377|''Table 5'']]'' ''show that the percentage of PET plastic increased with decreased OBC and modifies the Marshal properties of a mixture. The combination of optimum PET plastic and bitumen content, at 6.8% by weight of OBC and 5.04% by weight of aggregate, with 4% air void, was the optimum value to achieve good performance of the mixture. This indicates that PET plastic is used as a bitumen modifier to achieve the ERA specification at this optimum level. | ||

| − | ===3.2.2. Effect of PET plastic on the Marshal Stability and flow=== | + | =====3.2.2. Effect of PET plastic on the Marshal Stability and flow===== |

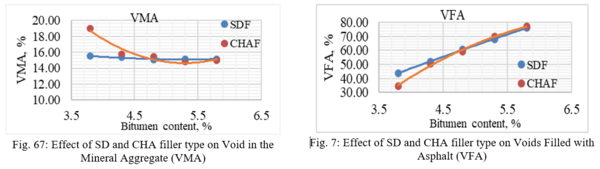

<span id='cite-_Ref79751902'></span>[[#_Ref79751902|''Figure 8'']]'' ''exhibits the effect of PET plastic contents on Marshall Stability. It shows that increasing the PET plastic decreases the OBC in the mixture; Marshall Stability also increases up to 9% value of PET content and then declines. This is because voids at lower bitumen content and higher PET content are too high, and the voids need to be filled with PET plastic coated over the aggregate and then separate aggregate interlock; hence, the effects tend to decrease the stability values. The stability value of modified bitumen (Bitumen with PET) is 15.9 KN, higher than that of unmodified bitumen, 14.3 KN, by 1.6 KN variation. It demonstrates the enhancement of asphalt mix stability with optimum PET plastic, which establishes a stronger bond between bitumen and PET plastic-coated aggregates through intermolecular bonding; this intermolecular attraction improves the stability of the mix. In addition, flow refers to the vertical deformation of the sample. High flow values typically indicate that the pavement becomes permanently deformed under the weight of traffic. In contrast, low flow values suggest an HMA mix with higher-than-normal voids and inadequate bitumen, resulting in reduced durability. Due to this, the pavement structure becomes cracked because of the brittleness of the mixture during the pavement's life. | <span id='cite-_Ref79751902'></span>[[#_Ref79751902|''Figure 8'']]'' ''exhibits the effect of PET plastic contents on Marshall Stability. It shows that increasing the PET plastic decreases the OBC in the mixture; Marshall Stability also increases up to 9% value of PET content and then declines. This is because voids at lower bitumen content and higher PET content are too high, and the voids need to be filled with PET plastic coated over the aggregate and then separate aggregate interlock; hence, the effects tend to decrease the stability values. The stability value of modified bitumen (Bitumen with PET) is 15.9 KN, higher than that of unmodified bitumen, 14.3 KN, by 1.6 KN variation. It demonstrates the enhancement of asphalt mix stability with optimum PET plastic, which establishes a stronger bond between bitumen and PET plastic-coated aggregates through intermolecular bonding; this intermolecular attraction improves the stability of the mix. In addition, flow refers to the vertical deformation of the sample. High flow values typically indicate that the pavement becomes permanently deformed under the weight of traffic. In contrast, low flow values suggest an HMA mix with higher-than-normal voids and inadequate bitumen, resulting in reduced durability. Due to this, the pavement structure becomes cracked because of the brittleness of the mixture during the pavement's life. | ||

| Line 299: | Line 298: | ||

[[Image:Draft_Quezon_352077040-image8.png|600px|alt='''3.2.3. Effect of PET plastic on the Density of a Mixture'''|''3.2.3. Effect of PET plastic on the Density of a Mixture'']] </div> | [[Image:Draft_Quezon_352077040-image8.png|600px|alt='''3.2.3. Effect of PET plastic on the Density of a Mixture'''|''3.2.3. Effect of PET plastic on the Density of a Mixture'']] </div> | ||

| − | ===3.2.3. Effect of PET plastic on the Density of a Mixture=== | + | =====3.2.3. Effect of PET plastic on the Density of a Mixture===== |

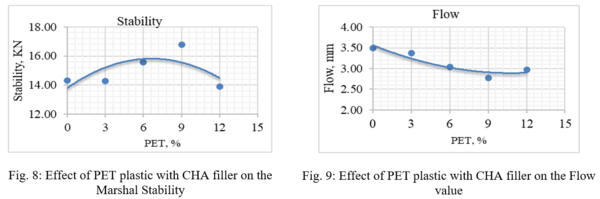

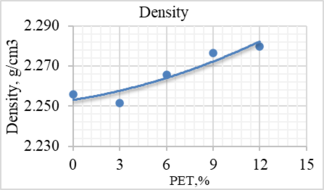

The effect of PET plastic content on the unit weight of the mixture is shown in <span id='cite-_Ref79752159'></span>[[#_Ref79752159|''Figure 10'']]. The bulk specific gravity of the mixture initially decreases and then increases with an increase in the percentage of PET plastic. The density value of modified bitumen (Bitumen with PET) is 2.268 g/cm<sup>3</sup>, slightly higher than that of unmodified bitumen, 2.256 g/cm3, by 0.012 g/cm<sup>3</sup> variation. This is because PET plastic has a higher unit weight than the binder used to coat the aggregate, increasing the unit weight of a mixture. | The effect of PET plastic content on the unit weight of the mixture is shown in <span id='cite-_Ref79752159'></span>[[#_Ref79752159|''Figure 10'']]. The bulk specific gravity of the mixture initially decreases and then increases with an increase in the percentage of PET plastic. The density value of modified bitumen (Bitumen with PET) is 2.268 g/cm<sup>3</sup>, slightly higher than that of unmodified bitumen, 2.256 g/cm3, by 0.012 g/cm<sup>3</sup> variation. This is because PET plastic has a higher unit weight than the binder used to coat the aggregate, increasing the unit weight of a mixture. | ||

| Line 309: | Line 308: | ||

Fig. 10: Effect of PET plastic with CHA filler on the Bulk specific gravity of the mixture</div> | Fig. 10: Effect of PET plastic with CHA filler on the Bulk specific gravity of the mixture</div> | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | =====3.2.4. Effect of PET plastic on the Voids in Mineral Aggregate (VMA) and Voids Filled with Asphalt binder (VFA)===== | |

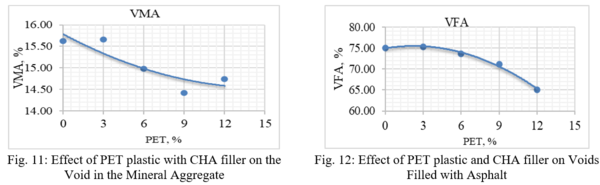

The minimum VMA is crucial for mixtures to accommodate sufficient asphalt content, allowing aggregate particles to be coated with an adequate asphalt film thickness. This consequently results in a durable asphalt paving mixture (Al-Shamsi et al., 2017). <span id='cite-_Ref79752381'></span>[[#_Ref79752381|''Figure 11'']] shows the lower VMA in the mixtures with an increment of PET plastic content. Here, the modified asphalt mixes generally have a lower VMA value than conventional asphalt mixes. This indicates that the Void here may be filled with PET plastic, which reduces the VMA. In general, the VMA percentage of the modified HMA mixtures (14.83%) is lower than the conventional asphalt concrete mixture value of 15.62% at an optimum PET plastic content of 6.8%; the results satisfy the ERA specification (minimum VMA = 13%). In addition to this, the effect of PET plastic content on the voids filled with the mixture's asphalt property is shown in <span id='cite-_Ref79752423'></span>[[#_Ref79752423|''Figure 12'']]''.'' It indicates that the VFA percentage of the modified asphalt decreases as the percentage of PET plastic increases. The Voids filled with conventional asphalt binder (15.62%) have a value greater than the PET plastic content (14.83%) at an optimum PET plastic content of 6.8%. | The minimum VMA is crucial for mixtures to accommodate sufficient asphalt content, allowing aggregate particles to be coated with an adequate asphalt film thickness. This consequently results in a durable asphalt paving mixture (Al-Shamsi et al., 2017). <span id='cite-_Ref79752381'></span>[[#_Ref79752381|''Figure 11'']] shows the lower VMA in the mixtures with an increment of PET plastic content. Here, the modified asphalt mixes generally have a lower VMA value than conventional asphalt mixes. This indicates that the Void here may be filled with PET plastic, which reduces the VMA. In general, the VMA percentage of the modified HMA mixtures (14.83%) is lower than the conventional asphalt concrete mixture value of 15.62% at an optimum PET plastic content of 6.8%; the results satisfy the ERA specification (minimum VMA = 13%). In addition to this, the effect of PET plastic content on the voids filled with the mixture's asphalt property is shown in <span id='cite-_Ref79752423'></span>[[#_Ref79752423|''Figure 12'']]''.'' It indicates that the VFA percentage of the modified asphalt decreases as the percentage of PET plastic increases. The Voids filled with conventional asphalt binder (15.62%) have a value greater than the PET plastic content (14.83%) at an optimum PET plastic content of 6.8%. | ||

| Line 317: | Line 316: | ||

[[Image:Draft_Quezon_352077040-image10.png|600px|alt='<spanid='_Toc76647913'></span>'''4. Conclusion and Recommendation''''|<span id='_Toc76647913'></span>'''4. Conclusion and Recommendation''']] </div> | [[Image:Draft_Quezon_352077040-image10.png|600px|alt='<spanid='_Toc76647913'></span>'''4. Conclusion and Recommendation''''|<span id='_Toc76647913'></span>'''4. Conclusion and Recommendation''']] </div> | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | =4. Conclusion and Recommendation= | + | ==4. Conclusion and Recommendation== |

This study tries to evaluate the mechanical performance of HMA containing PET plastic and CHA filler. Based on the results obtained from this study, the following conclusions can be made: | This study tries to evaluate the mechanical performance of HMA containing PET plastic and CHA filler. Based on the results obtained from this study, the following conclusions can be made: | ||

| Line 330: | Line 329: | ||

In general, it can be stated that the HMA containing a combination of 6.8% PET plastic and 3% coffee husk ash filler exhibits better mechanical performance in terms of Marshall stability and volumetric properties compared to the conventional HMA. Therefore, it is recommended to use it for asphalt pavement construction. | In general, it can be stated that the HMA containing a combination of 6.8% PET plastic and 3% coffee husk ash filler exhibits better mechanical performance in terms of Marshall stability and volumetric properties compared to the conventional HMA. Therefore, it is recommended to use it for asphalt pavement construction. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ====Acknowledgment:==== | |

The researchers would like to acknowledge the faculty of the Civil Engineering Department, School of Architecture and Civil Engineering, Institute of Technology, Hawassa University, Hawassa City, Ethiopia, and the College of Engineering and Architecture, Carig Campus, Cagayan State University, Philippines, for their unwavering support in finishing this research. | The researchers would like to acknowledge the faculty of the Civil Engineering Department, School of Architecture and Civil Engineering, Institute of Technology, Hawassa University, Hawassa City, Ethiopia, and the College of Engineering and Architecture, Carig Campus, Cagayan State University, Philippines, for their unwavering support in finishing this research. | ||

| − | + | ====Funding:==== | |

The authors received no direct funding for this research. | The authors received no direct funding for this research. | ||

| − | + | ====Conflict of Interest:==== | |

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article. | The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article. | ||

Revision as of 13:06, 12 October 2025

Affiliations:

2Cagayan State University, Carig Campus, College of Engineering and Architecture, Civil Engineering Department, Tuguegarao City, Philippines

ORCID: 2[0000-0003-0612-500X]

ISSN (Online): 2985-XXXX

License: This article is published under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license.

1. Introduction

Road networks make a significant contribution to a country's socio-economic activity. It is directly associated with the movement and accessibility of communities to use the road networks. (Obeta & Njoku, 2016). Ethiopia has approximately 110,414 km of roads spread throughout the country, comprising 14,055 km of flexible pavement road networks. (Road sector development program, 2015). It comprises subgrade, base course, subbase, and surface course layers (Babu, 2016; Flamarz Al-Arkawazi, 2017). Flexible pavement defects are caused by the quality and proportion of the material, affecting the performance of the HMA pavement structure (A. R. Prasad & Sowmya, 2015). The common types of pavement defects include rutting, cracking, depression, potholes, and raveling. These failures result from external conditions, such as traffic volume or load-associated factors and environmental influences, or non-load-associated factors, and internal conditions, including the quality and proportion of the material. (Ahmad et al., 2017; Aodah et al., 2012; Aziz et al., 2015; Hafeez et al., 2013).

The mechanical properties of the HMA mixture depend on the bitumen properties and the volumetric properties of the mixture components, including aggregate, asphalt, filler, and air voids (AL-Sahaf, 2015). The bitumen content, amount of filler added, and the provided air void in the mixture are the primary parameters used to characterize the volumetric composition and evaluate the performance of HMA pavements (Mirković et al., 2019). However, for a comprehensive assessment of the HMA mixture, the following mechanical properties—such as stiffness, resistance to fatigue cracking, and permanent deformation—are crucial (Choudhary et al., 2019). In road construction, the most common types of filler materials used in the production of asphalt mixture are Limestone, Portland cement, hydrated lime, fly ash, and stone dust. Due to this factor, the production of filler material is insufficient (Ararsa et al., 2019; Wagaw et al., 2018). However, in the construction of flexible pavements, the main issue is how to obtain an adequate amount of high-quality, locally available materials. Based on this issue, it is recommended to find alternative materials to replace the conventional filler with a filler material that provides better performance in the production of HMA mixtures (Varma & Lakshmayya, 2018).

Nowadays, it is difficult to control the quality of bitumen during the refining process, but using another alternative way to utilize modifier materials like polymer, fibers, sulfur, and other additive materials to modify the quality of bitumen (Habib et al., 2010; Mashaan et al., 2021). The addition of polymers improved durability, rutting, and cracking, and protected the environment from pollution (Chukka & Carr, 2016). In addition, filler material also plays a significant role in the mechanical behavior of hot mix asphalt (Likitlersuang & Chompoorat, 2016). It has two primary functions. One approach is to fill the Void between the aggregate skeleton in the mixture, making it denser, raising stability, and improving rutting resistance of the pavement by increasing the aggregate-to-aggregate contact surface area. Secondly, during the mixed preparation of filler materials with asphalt binder and form asphalt-mastic (Miró et al., 2016; Modupe et al., 2019; Remisova, 2015; Sarir et al., 2019). This property is modified to enhance the adhesive properties and overcoating binding nature, thereby increasing durability and improving the properties of the asphalt binder by reducing the binder's inherent temperature susceptibility. Therefore, this plays an essential role in controlling the mechanical properties of the asphalt mixture. (Arbabpour Bidgoli et al., 2019; Baby et al., 2017; Bi & Jakarni, 2019).

Different researchers have been carried out the possibility of conventional materials replacing by-products and bitumen modifiers material used in road construction those materials such as Bagasse ash, Rice husk ash, Fly ash, waste glass powder, sub-base course dust, Sawdust ash, Ceramic dust, Brick dust, Marble dust, Coal waste, wood ash and also bitumen modifier materials like polymer, fibers, sulfur, and other additive materials to modify the quality of bitumen. (Mashaan et al., 2021; Sangiorgi et al., 2017).

Sarir et al. (2019) Stated that the mechanical stability of bagasse ash filler increased by 20% and reduced the flow by half compared to the conventional stone dust filler. According to (Baby et al., 2017), waste glass powder used as a filler material in the asphalt mixture exhibited higher stability and lower flow values, approximately 44% and 3.79% lower than those of normal mixes with quarry dust. Likewise, Modupe et al. (2019) used Cow bone ash to replace quarry dust filler with 50% cow bone ash material in the HMA mixture. The result showed increased stability, reduced flow, and improved volumetric properties of filler compared with quarry dust. Zainudin et al. (2016) had utilized Bagasse ash as a filler material in the HMA mixture. The results showed that the filler effectively increased the Resilient Modulus, Marshall stability, and flow by 17.4%, 0.6%, and 4.9%, respectively, compared to the ordinary asphalt mixture. Rashwan (2016) have experimented with limestone powder as a filler in the production of an asphalt mixture. The results showed increased marsh stability, density, and indirect tensile strength, as well as decreased flow and fewer voids in the mineral aggregate, compared with conventional filler, leading to strain failure. On the other hand (Bi & Jakarni 2019) used wood ash as a filler material in the asphalt mixture. Compared with conventional filler, the result showed better resistance to permanent deformation, increased resilient modulus, decreased rutting, and improved fatigue performance. However, a few researchers have utilized coffee husk ash as a stabilizer in subgrade treatment and as a partial replacement for cement in concrete production. Still, no one can use coffee husk ash as a filler material in asphalt mixtures. Still, our country produces a massive quantity of coffee husk during coffee production and poorly utilizes this waste material.

Different experimental investigations have used PET plastic material as a bitumen modifier and an aggregate coating. Prasad & Sowmya (2015) stated that PET had been used as an asphalt modifier, and the optimum content was obtained at 6% by weight of bitumen to improve pavement stability. Azizi & Rashid (2018) pointed out that modified bitumen by plastic shows good properties compared to the original asphalt. Prasad et al. (2013) Investigated the possibility of using PET plastic as a binder modifier, and mixed it in proportions of 2-10% (by weight of OBC) at an interval of 2%. Ultimately, this resulted in higher resistance to rutting due to their higher softening point compared to conventional bitumen. Sahu & Singh (2016) reported that aggregate coating by plastics reduces the porosity and absorption of moisture, and improves the soundness of aggregate. Used as in the asphalt wearing course as an aggregate coat, and the optimum value is 12% of HMA by the weight of OBC.

In this study, coffee husk ash is used as a filler material. PET plastic serves as a bitumen modifier in the production of HMA mixtures due to its ready availability and relatively low cost in our country. Therefore, modification of HMA pavements using an alternative or local material is an essential objective. It enhances performance and service life while reducing the maintenance costs of the road (Mosa, 2017).

2. Materials and Research Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study was conducted at the Yirgalem Construction PLC laboratory in Hawassa, Ethiopia, which was equipped with complete laboratory facilities for undertaking the necessary tests. Hawassa is the city of the Sidama region and is located about 275 km from Addis Ababa. It is approximately located between 7°02'51´´ N Latitude and 38°29'44´´ E Longitude, and at an average elevation of 1716m above mean sea level.

2.2. Materials

The raw materials used for the laboratory study include aggregate, stone dust (SD), and coffee husk ash (CHA) filler, Bitumen 60/70 penetration grade, and shredded PET plastic. The materials used for this study are described in Table 1.

| Materials | Description | |

| Raw

Materials |

Coarse aggregate | Distribute the vehicle loads to the subgrade by grain-to-grain contact through the pavement structure safely. |

| Fine aggregate | To improve the density and strength of the HMA mix. | |

| Filler Material (Coffee husk-ash) | Coffee husk-ash fills the voids in the mixture and the dense aggregate skeleton, forming asphalt mastic. | |

| Bitumen | For binding and overcoating the aggregate. | |

| Shredded plastic (PET) | It is used as an aggregate coat and bitumen modifier of the asphalt mixture. | |

Source: (Manju, 2017; Mosa, 2017; Nega et al., 2013; Sarir et al., 2019)

2.2.1. Coffee husk ash as filler

The dry coffee husk was collected from Yirgalem town in the Sidama region. It is located 255 Kilometers from Addis Ababa and 35 kilometers from Hawassa city. The coffee husk was burned in the furnace at 550 °C for 4 hours to produce ash, and after complete combustion, the ash was allowed to cool for an additional 24 hours. The burnt ash was collected and sieved through a 0.075mm sieve, and the fractions passing through the sieve were used throughout the test. The sieved ash was stored in a container to prevent moisture absorption. Figure 1 Shows the product obtained after processing coffee husk.

Coffee husk is the primary residue or byproduct of coffee processing. According to the International Coffee Organization (2016), Ethiopia is the fifth-largest coffee producer in the world, with approximately 384,000 metric tons produced annually. From this production, approximately 192,000 metric tons of coffee husk residual, or by-product, are generated during the processing of coffee. The solid waste (coffee husk) is used as an extra for animal feed, but most of this waste, around 134,400 metric tons, is discarded, filled, and burned in the ground (Sime et al., 2017). By doing this, it can pollute the environment. Hence, proper use of this waste material can reduce storage requirements and mitigate environmental concerns associated with disposal.

2.3. Research Design

The study employed an experimental research method to address the research question and achieve the objectives. The study work consists of two phases: the first phase involved sample collection. At this phase, Aggregate, Bitumen 60/70 penetration grade, coffee husk, and shredded PET plastic were collected. The second phase involved a laboratory test, which followed the procedures of ERA, AASHTO, and ASTM. This phase is further classified into two steps. Step I: Quality Testing - The quality of the aggregate and bitumen was tested, compared, and verified to ensure compliance with the ERA specification. Step II: Marshal Mix Design - During the marshal mix design step, three types of mixtures were designed. A mixture of normal HMA with stone dust as a filler, coffee husk ash as a filler, and a combination of 3.2% coffee husk ash filler by weight of aggregate and shredded PET plastic at 3, 6,9, and 12% with HMA. Finally, it calculated the stability, flow, and volumetric properties of the mixture, assessed these properties, and checked whether they are suitable as a wearing course material. The aggregate and asphalt quality tests are shown in Table 2 and Table 3.

| Aggregate Physical Test | Test Method |

| The grain size distribution of Aggregates | AASHTO T 27 |

| Specific gravity and water absorption of aggregates. | AASHTO T 85-91 and ASTM C 127-88 |

| Aggregate Shape Test | BS 812: Section 105.1: 1989 |

| Aggregate Crushing Value Test-ACV | BS 812: Part 110: 1990 |

| Los Angeles abrasion test-LAA | AASHTO T 96-94 |

| Ten Percent Fines Value-TFV | BS 812-111:1990 |

| Asphalt cement physical test | Test Method |

| Penetration Grade test | AASHTO T 49 |

| Ductility test for asphalt | AASHTO T 51-94 |

| Softening point test | AASHTO T53-06 |

2.4. Mixing of PET plastic with bitumen

The shredded PET plastic that passed through the 4.75mm sieve was used. The mixed aggregates were heated in a chamber at 180 °C. (ERA Manual, 2013) Recommend that the heated temperature of aggregate exceeded the compaction temperature of the asphalt mixture by a range of 10-300 °C, and use a temperature of 150 °C heated asphalt binder for 60/70 grade asphalt binder. Then the shredded PET plastic was put into the chamber and heated along with the aggregate. Until the plastic gets coated uniformly over the aggregate within 30min-45min, an oily coating was given to the aggregate mixture. Similarly, the asphalt was heated to a temperature of 150 °C (Chukka & Carr, 2016). When this process is applied to achieve good binding and prevent weak bonding, as the plastic exhibits a double binding property, it improves the surface properties of the aggregates. This process is practical in all types of climates, as the emission of toxic gases is not possible below 270 °C. When the plastic is heated above 270 °C, it decomposes, and above 750°C, it burns to produce toxic gases. The most important thing to keep in mind is monitoring the temperature. In the next step, the hot aggregate mix was mixed with the hot asphalt at a temperature between 140 °C - 170 0C (Bale, 2011). This dry process was employed in the Marshall mix design, incorporating the addition of shredded PET plastic (Appiah et al., 2016; Farhana et al., 2017; Movilla-Quesada et al., 2019; Sahu & Singh, 2016).

2.5. Marshal test

Marshall Stability test was used to determine the optimum bitumen content and evaluate the stability, flow, and volumetric properties of the HMA mixture. It is a peak load carried by a compacted sample at a test temperature of 60 °C. The flow value is the deformation at which the sample undergoes during the loading up to the peak load in a 0.25 mm unit (Ararsa et al., 2019; Sarkar, 2019; Yohannes et al., 2020). For this study, three scenarios were conducted. First, prepared HMA by a normal mix using stone dust filler. Second, prepared the HMA mixture, entirely replacing the stone dust filler with Coffee husk ash, i.e., 3.2% by weight of the total mix. Third, a combination of CHA and shredded PET plastic was prepared on the HMA. It was done by 3%, 6%, 9%, and 12% PET by weight of optimum bitumen content (OBC). The HMA mixture was tested, and the stability, flow, and volumetric properties were calculated according to the Marshall mix design. Their properties were assessed, and it was checked whether the properties are suitable as a wearing course material.

2.5.1 Marshal Mix preparation

Before the marshal test, conducting the quality of bitumen and aggregate, then available aggregate materials, coarse aggregate (9.5mm-19mm), intermediate aggregate (4.75mm-9.5mm), fine aggregate (0-4.75mm), and filler, were integrated to get the proper gradation within the allowable limits according to ERA specifications using the trial and error method. The selected nominal maximum stone size was 19mm to consider a heavy traffic load.

The trials are continued until the percentage of each aggregate size is within allowable limits. An optimum aggregate proportion that meets both criteria was then selected. The aggregate blending proportions of 23%, 27%, and 50% were prepared for each of the three fractional sizes: 9.5mm-19mm, 4.75mm-9.5mm, and 0-4.75mm, respectively. Aggregates blending results are presented in Figure 2.

After this, a marshaled mix was prepared by weighing the mixture, first calculating the percentage retained of each aggregate size in each sieve size, and then converting it into a retained weight for each fraction size. The retained weight on each fractional size in each sieve size is the product of the total weight of the HMA mixture, the percentage composition of each fraction, and the percentage retained of each size of aggregate. Then, finally, calculated the Retained Weight on each fraction size by the Weight of the Mixture (ERA Manual, 2013; MS-2 Asphalt Institute, 2014).

2.5.2. Sample preparation

The mix design was handled by preparing three samples for each bitumen content. For all mixes, five different bitumen contents were selected by 0.5% increments. A sample consists of a combined aggregate weighing 1200 g. The aggregate and asphalt are then mixed at a temperature of 160–170 °C. The mixed samples were placed into a mold and compacted with 75 blows on each side by a 4.5kg hammer falling from 457mm height (MS-2 Asphalt Institute, 2014). From the total of forty samples prepared for the first, second, and third scenarios. In the first scenario, each sample with a weight of 1200 g was prepared using five different asphalt contents: 3.8%, 4.3%, 4.8%, 5.3%, and 5.8% by 0.5% increments, i.e., three samples for each asphalt content to obtain an average value. According to the ERA standard protocol (2013), first, the combined aggregate with SD filler and binding materials was heated to temperatures of 170-180 °C and 150 °C, respectively. Then, these ingredients were mixed at a temperature of 140-170 0C. MS-2 Asphalt Institute (2014) stated that the mixture was placed in the preheated mold and compacted at a temperature of 135-155 °C, using 75 blows on each side of the sample. The above procedure was repeated for the second scenario, with the only difference being that the stone dust filler was replaced with a coffee husk ash filler material. After obtaining OBC, the third scenario was done with the same procedures. Fifteen samples were prepared by considering four different proportions of PET shredded plastic, namely 3%, 6%, 9%, and 12% by weight of OBC, using a dry process method.

2.5.3. Volumetric Analysis

The volumetric properties are determined using mass and volume measurements, as well as the constituent components, including a binder, aggregate, and air void. The relationship between mass and volume is determined by the material's specific gravity (G) (Yohannes et al., 2020).

The Mixture volumetric parameters include Percentage of voids in the total mix (VTM), Percent void in mineral aggregate (VMA), Percent voids filled with asphalt (VFA), Percent aggregate (Ps), Percent Binder (Pb), Percent Binder Effective, (Pbe), Percent Binder Absorbed (Pba) (AL-Sahaf, 2015; ERA Manual, 2013; MS-2 Asphalt Institute, 2014; Yohannes et al., 2020).

- 1. Percentage of voids in the total mix (VIM)

VIM is the whole volume of air void throughout a compacted paving mixture, stated as a percent of the bulk volume of the compacted paving mixture

Where: Va = Air voids in the compacted mixture, Gmm = maximum specific gravity of paving mixture, Gmb = bulk specific gravity of the compacted mixture.

- 2. Percent void in mineral aggregate (VMA)

VMA is the volume of void space between aggregate particles of the compacted paving mixture. It includes air voids and the volume of asphalt not observed in the aggregate, expressed as a percentage of the total volume.

Where: VMA = voids in the mineral aggregate, Gsb= bulk specific gravity of total aggregate, Gmb = bulk specific gravity of the compacted mixture, Ps = aggregate content, percent by mass of total mixture, and Pb = percent of a binder.

- 3. Percent voids filled with bitumen (VFB)

VFB is the percentage of VMA that is filled with bitumen. It is calculated using:

Where: VFB = voids filled with bitumen (percent of VMA); VMA = voids in mineral aggregate, percent of bulk volume VIM = air voids in the compacted mix, percent of total volume.

- 4. Percent aggregate (Ps)

The total percentage of aggregate in the asphalt mixture is expressed as a percentage of the total mass of the mix.

Where: Ps = percentage of aggregate and Pb = percentage of bitumen content by total mix.

- 5. Percent Binder Effective (Pbe)

The functional portion of the asphalt binder that stays on the outside of the aggregate is not absorbed into the aggregate, expressed as a percentage of the total mix mass.

Where: Pbe = Effective binder content of a paving mixture, Pb = percent of bitumen content by total mixture, Pba = percent of binder absorbed, and Ps = percent aggregate by total mix weight.

- 6. Percent Binder Absorbed (Pba)

The asphalt binder that is absorbed into the aggregate is expressed as a percentage of the total aggregate. It is calculated by:

Where: Pba = Binder absorption, Gb = Specific gravity of bitumen, Gse = Effective specific gravity of aggregate, and Gsb = Bulk specific gravity of aggregate.

2.5.4. Optimum Bitumen Content Determination

The Marshall test was used to determine the optimum binder content. Five different percentages of asphalt were examined to determine the optimum percentage for the aggregates used, including 3.8%, 4.3%, 4.8%, 5.3%, and 5.8% by weight of the mix, with three samples for each percentage. According to ERA Manual (2013)Define the OBC by determining the asphalt content corresponding to 4% air void, and fix the values of stability, density, flow, VMA, and VFA. The 2013 ERA specification, AASHTO, and other Countries' specifications, like those in the Philippines, generally state that the percentage of air void in the mixture is 3-5%.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of fillers on the Marshal Properties of HMA mixture

The results of Marshal Tests on bituminous mixes are prepared by using coffee husk ash (CHA) and stone dust filler (SD), and compared with each other at the same optimum percentage of 3.2% by weight of aggregate from the job mix formula. The relationships between binder content and the properties of mixtures From the test results, the optimum bitumen content (OBC), stability, flow, density, VTM, VMA, and VFA were selected and compared. Table 4, and Table 5 indicate the properties of the mixtures obtained for the two filler mixtures.

3.1.1. Effect of filler on the Optimum Bitumen Content

Table 4 and Table 5 indicated that the corresponding OBC for the mix was found to be 5.7 and 5.4% at 4% air void with stone dust and coffee husk ash filler, respectively. This result explains that the OBC of the SD filler is higher by 0.3% than that of the CHA filler. To observe that the SD filler is finer than the CHA filler. This may occur because most of the Void between the aggregate skeleton in the mixture is excessively filled by SD filler, reducing the air void, which results in a denser pavement, increased stability, and reduced flexibility. Additionally, the SD filler absorbs more bitumen, leading to an increase in the OBC of the mixture. This occurred because SD filler has a higher surface area, allowing it to absorb more bitumen and form more asphalt-mastic, resulting in higher lateral flow compared with CHA filler. Due to this situation, the pavement becomes cracked, and permanent deformation occurs when heavy vehicles move on the pavement before the design period.

3.1.2. Effect of filler on Marshal Stability and flow