m (Tag: Visual edit) |

(Tag: Visual edit) |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

==Abstract== | ==Abstract== | ||

| − | + | In exploring the performance-enhancing effects of compression sportswear, this study investigates its impact on trunk muscle activation during core stability training, with a particular focus on the biomechanical implications of this relationship. This research posits the existence of an Equilibrium Point of Motion (EPM) and employs surface Electromyography (EMG) to measure muscular responses in the Erector Spinae (ES), External Oblique (EO), and Rectus Abdominis (RA) during exercises performed with and without compression wear. Results revealed that compression garments significantly augment root mean square (RMS) values for ES and EO muscles, suggesting differential muscle activation patterns. Further, the application of OpenSim modeling of full-body musculoskeletal mechanics facilitated a novel analysis of muscle forces and activations, enhancing the understanding of sportswear functionality in an ergonomic context. This approach uncovered significant correlations between actual and simulated muscle activations, particularly for the ES and EO during a gluteal bridge exercise. These insights contribute to the development of ergonomically-engineered sportswear aimed at optimizing athletic performance and provide a valuable reference for future sportswear design and research. | |

| − | '''Keywords''': | + | '''Keywords''': Sportswear; Model Simulation; Surface-Electromyography; Core training; Tight shorts; Compression |

==1. Introduction== | ==1. Introduction== | ||

| − | + | Tight-fitting sportswear has received much attention due to its effect on the body's performance, which is related to the mechanics of contraction of pressure and activity [1,2]. The core stability training lies at the heart of many aspects of fitness and professional sports, in addition, to an evolving emphasis on functional integration for dynamic athletic performance [3]. | |

| − | + | Core stability training is a mode of exercise focused on strengthening the trunk muscles, which include the abdomen, back, pelvis, and hips, and also is clouded by sportswear shorts [4, 5, 6,7]. Two main methods to monitor or evaluate performance are subjective assessment of core stability through observation and objective measurement of biofeedback, including electromyography, motion capture, and further calculation or simulation of torque, and strength [8, 9]. Many researchers have supported some positive effects of the sportswear pressure impact on the overall impact of sportswear on the sensorimotor system and may decrease muscle soreness and pain [10, 11]. There remains a lack of detailed exploration into specific areas. Whereas, the effect mechanisms and extent of tight-fitting shorts are unclear to the performance of body core stability, focusing on the abdomen and waist region [12, 13]. To further explore the association between sportswear and body performance, comparing different wear conditions in experimental data. | |

| − | + | Previous studies encompass the impact of wear conditions on core dynamics, ranging from the influence of footwear on muscle response time to the differentiated effects of wearable products on specific muscle groups [14,15]. Lee and Do distinguish tight-fitting shorts from compression stockings [16]. Their evaluation of the functions of these products, with a specific focus on the lower back during core training. This research suggests that the unified recruitment of abdominal and back muscles, coupled with additional support to erector spinae (ES), rectus abdominis (RA), and external oblique (EO), can be achieved through these wearables [17]. Maximal voluntary isometric contraction and peak muscle power after motion were greater than without compression garments with a slight effect [2] It provides a perspective on wearable products' potential impact on specific muscle groups during core training [18,19]. Because compression garment materials and pressures may alter the response to movement, previous reviews recommended that all compression garment studies measure and report pressures at multiple sites and specify the materials used [10,20]. | |

| − | + | While studies have reported positive effects, such as reduced muscle soreness and pain, there is a relative paucity of research on how these garments specifically affect core stability, particularly in the lower back and abdominal region. To address this gap, our study concentrates on a largely unexplored aspect: the activation patterns of core muscles, with an emphasis on the lumbar region, during core stability exercises while wearing compression shorts. This focus provides a novel vantage point by isolating the lower back area, a crucial element in core training, yet often overlooked in compression garment studies. | |

| − | + | Despite extensive research on the biomechanical impact of tight sportswear, previous studies have predominantly centered on the generalized effects of sportswear pressure on muscle response and sensorimotor function. Significant gaps remain in our understanding, particularly concerning the activation patterns of muscles in the lower back and waist area during core stability exercises. This paper proposes to fill these gaps by exploring the specific biomechanical and ergonomic impacts of lower back compression afforded by tight-fitting shorts. This represents an innovative direction in textile performance research, with the potential to deepen our grasp of how compression garments influence core muscle activation, with implications for both athletic performance optimization and the design of sportswear that supports the lower back. | |

| − | ===2.1 | + | This research is pioneering in that it not only documents the muscle activation patterns but also quantifies the degree of compression and its direct correlation with muscle activation in the lumbar region. This duality in focus – examining both the physical pressure exerted by the garment and the physiological response of the body – marks a significant departure from previous work, which often neglects the lower back coverage and its specific activation during core exercises. |

| + | |||

| + | In recent years, in the field of research on sports biomechanics and muscle structure simulation, various methods and kinetic simulation software applications have provided insights into understanding muscle activity, muscle geometry, and muscle performance when subjected to loads. Stokes and Gardner-Morse constructed a mathematical model incorporating the abdominal muscles and performing optimization calculations with Matlab software [21]. It revealed how abdominal muscle activity reduces the load on the spine by increasing intra-abdominal pressure. Beaucage and Gauvreau estimated the forces on the lower lumbar spine during symmetric and asymmetric weightlifting tasks using OpenSim software [22]. The study revealed the specific effects of various tasks on spinal forces involving the gluteus maximus, psoas maximus, and paravertebral muscle groups, which provided new perspectives on the assessment of exercise mechanics loading. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Branyan and Menguc synthesized a personalized anatomical curve muscle geometry model to simulate the mechanical behavior of muscles such as latissimus dorsi, extensor spinae, rectus abdominis, and obliquus abdominis [23]. The geometric model of curved muscles was also mapped by incorporating muscle geometry, moment arms, and fiber direction paths. Guo and Ren refined and optimized the microfilm element embedded in a flexible multibody dynamics model to enhance the understanding of the role of the core musculature in regulating the pressure distribution and stability of the spine [24]. The model included core muscle groups such as rectus abdominis, obliques, adductors, and multifidus. In summary, these studies, through the use of quantitative measurements and model simulation techniques, provide a simulation basis for a comprehensive understanding of the behavior of human muscles during exercise states and the interactions between muscles and bones, which in turn helps to facilitate the optimization of sports equipment design. Key research results and major findings of previous researchers provide valuable references in the field of muscle biomechanics modeling and simulation analysis. This study seeks to reveal how varying levels of tightness and the anatomical fit of the shorts could modulate this muscle activity, thereby contributing to a more targeted approach in the design of compression sportswear. The ultimate aim is to provide empirical data that could lead to enhanced ergonomic design of sportswear, precisely engineered to improve core training outcomes and reduce injury risk associated with lower back strain. This paper advocated that the relationship between the compression of sportswear and subject ergonomic aids and mechanisms should be further enhanced by achieving an equilibrium of muscle activation and pressure level. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==2. Methodology== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===2.1 Subjects === | ||

| + | |||

| + | The experiment was approved by the institution’s human research ethics committee (EST-2024-001). Written informed consent was obtained from fifteen healthy male participants (22.4±2.7 years old, 68.5±1.6 kg, 178±2.2 cm). The study involved subjects' surface electromyography (EMG) during various exercises to measure muscle activity. EMG data were used to infer characteristics of muscular strength. All participants were healthy, and they had agreed to and understood the content of the experiment. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === 2.2. Standardized Compression === | ||

| + | The study meticulously detailed the protocol implemented to ensure that each subject experienced a similar level of compression from the tight-fit shorts. Different sizes of shorts were provided to the subjects according to their somatotypes to ensure consistent clothing pressure. The clothing pressure experienced by the subjects was measured to confirm uniformity and compared against the pressure of cotton shorts, which served as a no-pressure control. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === 2.3. Instrumentation === | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== 2.3.1. Subjective Clothing Pressure Comfort Evaluation ==== | ||

| + | Subjects were instructed to wear standardized tight-fit shorts for consistency. Following a tactile test, subjects completed a questionnaire regarding the comfort of the fabric. This subjective evaluation data was compiled and analyzed to compare comfort performance across various fabric types. Feedback on perceived compression was recorded, providing qualitative data to complement the quantitative analysis. Data analysis included assessing averaged pressure values and inter-subject variability to confirm a standardized perception of tightness among all participants. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== 2.3.2. Electromyography ==== | ||

| + | Surface electromyography (EMG) was used to capture muscle activity during different core training exercises. EMG data were collected using the Delsys Trigno Avanti sensor hardware and EMGworks software (version EW4, Inc, USA) at a high sampling rate of 1092 Hz. Subjects participated under two wear conditions: tight-fitting sports shorts and cotton shorts without pressure. This aimed to explore the impact of sportswear on muscle activation. Table 1 provides an overview of the placement of EMG sensors on various muscles. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Table 1 Placement of EMG Sensors on Muscles in the Human Body | ||

| + | {| class="MsoNormalTable" | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>EMG(NO.) | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Position | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Muscle | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Illustration | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>1 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>left | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Rectus Abdominis | ||

| + | |||

| + | | rowspan="6" | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Back Front | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>2 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>right | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Rectus Abdominis | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>3 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>left | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>External Oblique | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>4 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>right | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>External Oblique | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>5 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>right | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Erector Spinae | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>6 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>left | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Erector Spinae | ||

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== 2.3.3. Testing Sport Shorts ==== | ||

| + | The tight-fit shorts were selected and standardized to ensure each subject experienced uniform compression according to their somatotypes. The shorts' compression attributes were indicated by their elastic modulus in both warp and weft directions. Comparative analyses were conducted against control garments (cotton shorts with no compression features). This approach ensured a comparative analysis to discern potential differences in muscle activation patterns based on the type of sportswear worn during core exercises. Table 2 illustrates the fabric content of pants provided to participants. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Table 2 Detail of Various Garments Provided to Participants | ||

| + | {| class="MsoNormalTable" | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Nylon Content (%) | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Spandex Content (%) | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Longitudinal Elasticity Modulus (MPa) | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Latitudinal Elasticity Modulus (MPa) | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Subjective Comfort Score | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Compression Score | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>88 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>12 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>166.62 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>106.70 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>4.2 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>4.5 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | | colspan="6" | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Cotton Content (%) | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | | colspan="6" | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>100 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== 2.3.4. Motion Capture ==== | ||

| + | Inverse kinematics values for actual motion capture inputs in OpenSim. Optical motion capture system that captures data from the subject during hip bridge movements. When performing hip bridge motion capture experiments, the marker points were determined based on anatomical knowledge and in conjunction with the bony prominence points of the human body (see Figure 1). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Figure 1 Schematic diagram of reflective dots attached to the human body | ||

| + | |||

| + | === 2.4. Experiment Protocol === | ||

| + | The experimental protocol was meticulously designed to ensure consistency, accuracy, and reproducibility in investigating EMG responses during core training exercises. Participants were briefed on the study's objectives and provided informed consent. Before starting the exercises, participants underwent a standardized warm-up routine to minimize injury risk and ensure optimal muscle activation. This routine included light activity and specific dynamic stretches targeting core muscle groups. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Participants performed a series of core training exercises (Table 3), including the gluteal bridge and seated leg raise [25]. Each exercise was repeated for a predetermined number of sets and repetitions. To control for rhythm and cadence during exercise execution, participants were provided with auditory cues from electronic metronomes set to 60 bpm. This control minimized variability in muscle activation patterns, ensuring observed differences were due to sportswear type rather than movement cadence [26]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Table 3 Demonstration of each exercise and details in number of sets, repetitions, and rest intervals | ||

| + | {| class="MsoTableGrid" | ||

| + | |||

| + | | rowspan="2" | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>No | ||

| + | |||

| + | | rowspan="2" | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Motion | ||

| + | |||

| + | | colspan="3" | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Procedure | ||

| + | |||

| + | | rowspan="2" | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Repeat time | ||

| + | |||

| + | | rowspan="2" | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Count | ||

| + | |||

| + | | rowspan="2" | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Rest (s) | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | colspan="2" | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Start position | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>End position | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>1 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Gluteal bridge | ||

| + | |||

| + | (GB) | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | | colspan="2" | | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>10 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>3 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>60 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>2 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Seated leg raise | ||

| + | |||

| + | (SLR) | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | | colspan="2" | | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>10 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>3 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>60 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | For the gluteal bridge (GB): | ||

| + | |||

| + | - Initial position: Subject lay on their back with knees bent, supported by heels, elbows, and head. | ||

| + | |||

| + | - Process: Lift the waist, arch the body so that hips are raised, and abdomen levels with knees, then slowly lower to the initial posture. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For the seated leg raise (SLR): | ||

| + | |||

| + | - Initial position: Lean back to maintain balance and keep the lower back straight. | ||

| + | |||

| + | - Process: Contract abdominal muscles, lean back slightly to maintain balance, and bend knees to lift legs [27]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The comprehensive experiment protocol, including standardized warm-up, exercise demonstration, controlled repetitions, and rhythm management, contributed to the robustness and validity of the observed EMG responses to varying sportswear conditions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Data were analyzed using EMGworks Analysis software. EMG signals from six muscles were calculated in absolute value and filtered using a Butterworth bandwidth between 4 and 400 Hz. RMS procedures were applied, and data were subsetted by time point. Motion EMG data were averaged using SPSS to compare different wear conditions. Amplifiers (Trigno Wireless System, Delsys Inc., Boston, USA) were used for all participants. Peak and mean muscle activity were averaged for the right and left muscles. Ten repetitions were analyzed and averaged to form an "ensemble average" curve, summarizing typical movement characteristics. RMS was used for the time normalization of repetition cycles. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Analysis was performed using repeated measures ANOVA in SPSS (version, IBM Institute Inc., NC) with two within-subject factors (wear status, and exercise motion) [2]. As Mauchly’s test of sphericity did not satisfy the assumptions, the results were based on multivariate ANOVA. The study aimed to compare the impact of tight-fitting sports shorts on athlete performance during core training exercises, extending findings on the impact of sportswear on biomechanical aspects [9]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Our findings support functional sports device design and contribute to rehabilitation research with smart garments [28]. The repeated ANOVA of six EMG zones identified distinct patterns in motion curves when participants wore tight-fitting shorts compared to loose-fitting cotton underwear. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==3. Results== | ||

| + | |||

| + | === 3.1 Impact of Compression Garments on RMS === | ||

| + | The examination of various wear statuses during core training revealed substantial variability in RMS values compared to instances involving cotton shorts and tight shorts. As depicted in Table 4, there were significant differences in almost all measurements (RMSRA, RMSEO, and RMSES (sig=0.000<0.05) for both the wearing state and the motor task. the state of dress and the motor task had a significant effect on the measurements, with the specific effect size being measured by the partial Eta square. It is important to note that the observed power in Table 5 (Wear status: 285.534, Exercise motion: 2968.996) is also high, indicating that different exercise motions could be influential in our findings. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Table 4 Multivariate Tests of Muscle RMS Value Between-subjects Effects and In-subject Comparison Testing | ||

| + | {| class="MsoTableGrid" | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Effect | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Method | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Value | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Sig. | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Partial Eta Squared | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Observes Power | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Wear status | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Pillai’s Trace | ||

| + | |||

| + | Wilk’s Lambda | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hotellin’s Trace | ||

| + | |||

| + | Roy’s Largest Root | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.817 | ||

| + | |||

| + | 0.183 | ||

| + | |||

| + | 4.461 | ||

| + | |||

| + | 4.461 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.000 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.817 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>285.534 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Exercise motion | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Pillai’s Trace | ||

| + | |||

| + | Wilk’s Lambda | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hotellin’s Trace | ||

| + | |||

| + | Roy’s Largest Root | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.980 | ||

| + | |||

| + | 0.020 | ||

| + | |||

| + | 48.672 | ||

| + | |||

| + | 48.672 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.000 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.980 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>2968.996 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Table 5 The Result of Multivariate Testing | ||

| + | {| class="MsoTableGrid" | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Effects | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Muscle | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Sig. | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Partial Eta Squared | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Observes Power | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | rowspan="3" | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Wear status | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>RMSRA | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.000 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.455 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>1.000 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>RMSEO | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.000 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.383 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>1.000 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>RMSES | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.000 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.772 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>1.000 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | rowspan="3" | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Exercise motion | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>RMSRA | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.000 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.895 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>1.000 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>RMSEO | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.000 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.941 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>1.000 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>RMSES | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.000 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.793 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>1.000 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| + | In exercise motion, we observed pronounced enhancements in the Erector Spinae (EO) muscles during the Straight Leg Raise (SLR) regimen across all groups and exercises. This phenomenon was particularly decreased when participants wore tight-fitting shorts, underscoring the potential impact of clothing on muscle engagement [41]. The muscles in the back group, specifically the erector spinae (ES), exhibited increased recruitment of muscle units during the hip bridge (HB) exercise. The primary functional contribution was attributed to ES, with relatively lesser involvement of the rectus abdominis (RA) and external oblique (EO).In the initial phase of the seated leg raise exercise, the activation of the erector spinae(EO) in the control group wearing cotton shorts and rectus abdominis (RA) in the group wearing shorts is modest. Notably, towards the middle and end of the exercise sequence, there was a significant surge in EO activation with cotton pants. A parallel trend was observed in RA during the latter part of the exercise. In comparison to muscles without tight-fitting shorts, RA's root mean square (RMS) value in wearing tight shorts demonstrated a more balanced and consistent level throughout the entire duration. This suggests that the utilization of tights may contribute to a more measured and evenly distributed strength training experience. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === 3.2 Validation and analysis of muscle activation simulation results === | ||

| + | The measured muscle activation was calculated using electromyography (EMG) data. The muscle forces calculated from the simulation were synchronized to correspond with the muscle activation values obtained from the EMG experiments. Each muscle was compared between the simulation-calculated muscle activation and the measured EMG activation. Trends and values of the two sets of results were analyzed. If the simulated activation shows a consistent trend with the measured EMG data and is numerically similar or can be reasonably calibrated to match, the model is considered to be relatively accurate. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The OpenSim model calculates the muscle joint moments by the static optimal solution method based on the results derived from reverse engineering [42,43]. The accuracy of the model and the consistency of the experimental data were assessed by constructing a model simulation of the core muscles of the low back in the hip-bridge movement (see Figure. 2, Figure. 3) and validating it in comparison with the experimental data of electromyography (EMG). The model including rectus abdominis, external abdominal obliques, and erector spinae was successfully modeled by the OpenSim multibody dynamics platform. The hip bridge maneuver was evaluated as an example to compare the trend of EMG signal curves with the simulated muscle force curves to verify the reasonableness of the established exercise biomechanics model. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Figure 2 Simulation of the core muscles during hip-bridge movements (initial state) | ||

| + | |||

| + | Figure 3 Simulation of the core muscles during hip-bridge (process state) | ||

| + | |||

| + | When comparing the ratio of the root-mean-square (RMS) value of electromyographic values during an actual movement to the maximum voluntary contraction (MVC), the unit usually used is the percentage, which represents the intensity of electromyographic activity as a relative value of the MVC. RMS, on the other hand, is usually measured in microvolts (µV), which directly reflects the change in amplitude of the electrical signal. For the muscle force data output from the OpenSim motion model, the units are usually Newtons (N). Since the strength of the EMG signal is not directly equivalent to the force produced by the muscle, a transformation or normalization method is required to correlate these two different measurements when making comparisons. Since the focus of the study was on the relative changes in muscle activity, this chapter chose to directly compare the trends of each of the two parts of the data without converting the force into units of the electrical signal. Despite the non-uniformity of the measures, the degree to which the model agrees with reality can be assessed qualitatively by analyzing the activity trend similarities and correlations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this study, the OpenSim multibody dynamics model was validated by comparing it with electromyography (EMG) experimental data. By comparing the muscle activation data in the model with the EMG data collected in the experiments one by one, the results showed that the two showed a high degree of consistency and maintained relatively close numerical proximity in terms of activation (Figure. 4, Figure.5, Figure. 6). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Figure 4 Comparison of EMG and simulated values of the erector spinae muscle | ||

| + | |||

| + | Figure 5 Comparison of EMG measurements of the external abdominal oblique muscle with simulated values | ||

| + | |||

| + | Figure 6 Comparison of electromyographic eigenvalues of the rectus abdominis muscle with simulated values | ||

| + | |||

| + | The lumbar back muscle force in the simulation calculation model corresponded to the root mean square amplitude data of EMG activities collected by the actual EMG. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==4. Discussion== | ||

| + | To investigate the impact of tight-fitting sports shorts on athlete performance during core training exercises, focusing on the electromyographic (EMG) activity of the rectus abdominis (RA), external oblique (EO), and erector spinae (ES) muscles. We established a novel measurement approach and aimed to contribute to the understanding of sportswear's ergonomic influence on musculoskeletal function in core training. Our methodology involved comparing EMG signals across different muscle groups, particularly emphasizing the potential variations in muscle activation patterns associated with the use of tight-fitting sports shorts during core training exercises. During core stability training, the RA, EO, and ES muscles were strengthened to achieve body stability. The effect mechanisms of the abdomen and lower back region are likely related to tights wearing [29]. It is therefore speculated that body core training muscle activation from focus is hardly negligible at the same level [30]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The findings presented a nuanced perspective on muscle activation. While no significant differences were observed in testing times for EMG activity in the RA group, the ES muscles exhibited weaker RMS volume and a flatter curve. This suggests a potential influence of sportswear on the engagement of specific muscle groups, particularly the ES muscles. Additionally, the study revealed intriguing patterns during the seat leg raise exercise, indicating that the engagement of the external oblique (EO) muscles was influenced by the characteristics of the tight-fitting shorts. This observation adds complexity to our understanding of how sportswear may affect muscles. The result may guide the design and development of compression garments for optimal performance and benefits during core training. The implications of our findings extend beyond the immediate scope of this study. The identified patterns in muscle activation provide valuable insights for the design of sportswear that aims to optimize muscle engagement during core training. This has practical applications not only in sports performance but also in rehabilitation, aligning with the growing interest in smart garment applications for health-related interventions. Furthermore, the observed differences in muscle activation patterns suggest that athletes and individuals engaging in core training exercises may benefit from sportswear tailored to specific muscle groups, potentially enhancing exercise performance and minimizing the risk of injury. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === 4.1. Influence of Compression Garments on RMS === | ||

| + | There has been a limited focus on examining the functional effects of athletic shorts specifically tailored for core sports [8]. The neuromuscular efficiency of trunk muscles increases with trunk flexion (Weston et al., 2018). Consequently, one of the novel aspects of this research is its selection of a specific sport to conduct an in-depth analysis of the electromyography (EMG) activation patterns associated with wearing compression shorts during athletic performance [32,16]. The previous work has proved that pattern muscle movement of retraining. Results showed evidence that core exercise. However, the existing literature lacks a comprehensive investigation into the functionality of compression shorts during core sports activities [33,34]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To bridge this research gap, this study emphasizes and compares the effects of wearing compression shorts and non-compression shorts, specifically examining their influence on muscle activation patterns (as measured by EMG) during sporting activities. By evaluating the outcomes of this study, it becomes possible to establish the link between the results obtained and those of previous researchers, both their similarities and discrepancies. A similar conclusion of the overall results of the meta-analyses suggests a slight likelihood of the benefit of compression garments on exercise recovery [10,20]. The results suggest that compression garments may be recommended after resistance training or eccentric exercise to aid recovery of maximal strength, power, and endurance performance. Garment fabric deformation and generated internal stresses on the body have demonstrated that clothing pressure has a greater effect on relieving muscle fatigue. Our results are in general agreement with the previous study on wearing the tights status of the muscles implying a decreased EMG amplitude and the peak torque of muscle contractions decreased approximately, compared to the control group [35]. Our current findings expand prior work with trunk muscle of RA, ES, EO activation mode, and tight shorts in core training, which derived a decrease in muscle strength and a lower EMG activity in the control group [14]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === 4.2 Equilibrium Point of Motion (EPM) === | ||

| + | The findings of this research demonstrate that wearing compression shorts during core sports activities elicits specific EMG activation patterns in the muscles involved. These observations are consistent with the existing research on compression garments and their influence on muscle activation. Nam measured that a garment wear pressure above 4 kPa is regarded as harmful to health [36], by considering the broader implications of sportswear on various aspects of athletic performance—such as fatigue mitigation. Former findings suggested that wearing compression short-tights with a pressure intensity of 15-20 mm Hg at the thigh can reduce the development of fatigue in thigh muscles during submaximal running exercise in healthy adult males [37,38]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | RMS values do not always rise with linear increases in elastic modulus. There was a tendency for excessively high thresholds of compression to affect muscle activity, resulting in a decrease in EMG RMS. As the meridional elastic modulus increases, the EMG signal may rise slightly and then fall. A higher modulus of elasticity initially increases the level of muscle activation but then decreases this activation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The point of motor equilibrium of muscle activation concerning time and stress. This equilibrium point may be a point in time and a specific stress value at which muscle activation is optimal or most adaptive. Moreover, this study provides support for the idea that compression shorts can enhance athletic performance by reducing muscle fatigue and improving exercise efficiency. The unique contribution lies in both the selected sport and the focused investigation of the effects of compression shorts on muscle activation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === 4.3 Correlation analysis of simulated muscle force and electromyographic data === | ||

| + | In this study, the statistical method of correlation analysis was used for consistency analysis to assess the strength of correlation between simulated and experimental data by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient to assess the consistency between simulated and experimental data. The correlation between the model and the experimental real data is high. As can be seen from Table 6 below, correlation analysis was utilized to go over the correlation between the EMG measured values and the model output muscle strength, using the Pearson correlation coefficient to indicate the strength of the correlation. The correlation coefficient value between the measured and simulated values of the erector spinae, and rectus abdominis muscles of the gluteal bridge is 0.747 and shows significance at the 0.01 level, thus indicating a significant positive correlation between the two. The value of the correlation coefficient for external abdominal obliques was 0.455 and showed significance at a 0.05 level. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Table 6 Correlation analysis of analog and electromyographic eigenvalues of muscles | ||

| + | {| class="1" | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | | colspan="3" | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>EMG eigenvalues | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Model output muscle strength | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Erector spinae muscle | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>External abdominal obliques | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Rectus abdominis muscle | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>Pearson's correlation coefficient | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.747** | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.455* | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.824** | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>P value | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.000 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.038 | ||

| + | |||

| + | | | ||

| + | <nowiki> </nowiki>0.000 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| + | <nowiki>*</nowiki> ''p''<0.05 ** ''p''<0.01 | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the statistical comparison plots (Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7), it can be observed that the overall trend of the simulated and measured data possesses a clear consistency, although a certain degree of error occurs in individual data points. The average error estimate from the overall analysis is around 8%, which shows that although there are minor deviations in the model, they are not enough to affect the validity of the model. Therefore, we can consider that the established virtual model can better reproduce and verify the rule of change of electromyography and its dynamic characteristics in the experiment. This model not only verifies the authenticity of the muscle force and activity trend but also can be used for further simulation and theoretical research, which provides a reliable tool for deepening the understanding of the mechanism of low back movement. The possible reasons for the errors on individual data points are attributed to two aspects. One is that the model simplifies the biomechanical system to a certain extent and may not fully reflect all detailed features. Parameters in the model are usually set based on mean values, which may differ from actual individuals. The experimental data reflect the physiological characteristics of a limited number of individuals, whereas the model is based on general anatomical and biomechanical parameter settings, and there may be bias due to individual differences. Second, EMG data acquisition in experiments may be affected by equipment limitations, noise interference, and other factors, resulting in data errors. Specific movements involve complex muscle synergies, and it is difficult for the model to fully capture the synergistic dynamics. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Simulation models based on similar schemes have been developed previously to analyze muscle vitality ratios. A comparison of computational and experimental results with this literature revealed that the measured EMG data showed activity levels of the lumbar muscles that matched the data obtained in the text [39.40]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==5. Conclusions== | ||

| + | 1. '''Performance Improvement through Compression Shorts:''' Our study underscores the potential performance enhancement achievable by wearing compression short tights during exercise, particularly in activities involving core training. The application of appropriate pressure intensity was found to influence muscle activation patterns positively. We introduced a novel measurement approach to contribute to a deeper understanding of the ergonomic impact of sportswear on musculoskeletal function during core training. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2'''. Muscle Activation Patterns and Core Stability:''' Our methodology involved a comprehensive comparison of EMG signals across different muscle groups, with a specific focus on the RA, EO, and ES muscles during core stability training. The observed strengthening of these muscles might indicate improved core stability, emphasizing the efficacy of high waist compression shorts in targeted trunk muscle engagement. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 3. '''Advocation equilibrium of muscle activation and compression from sportswear''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The relationship between the compression of sportswear and subject ergonomic aids and mechanisms should be further enhanced by achieving an equilibrium of muscle activation and pressure level. This study provides support for the idea that compression shorts can enhance athletic performance by reducing muscle fatigue and improving exercise efficiency. | ||

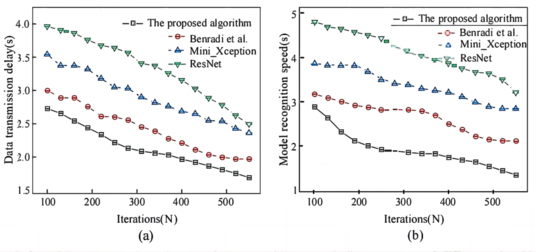

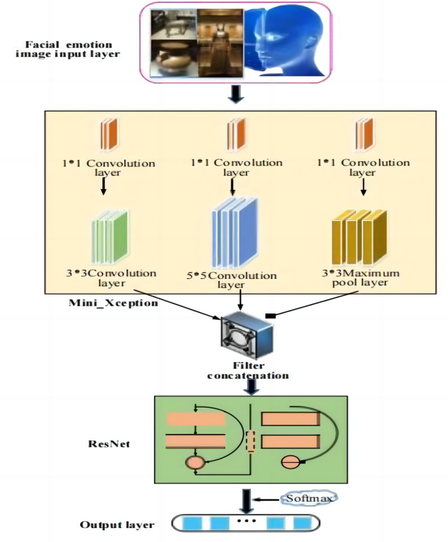

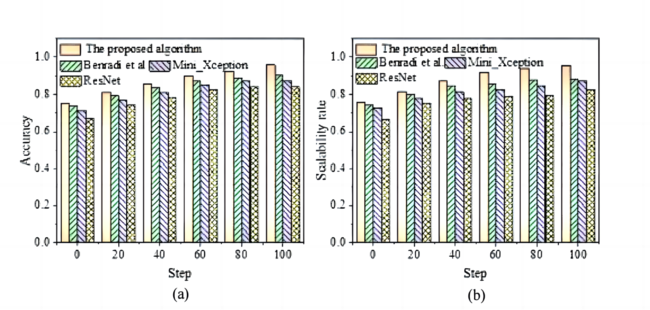

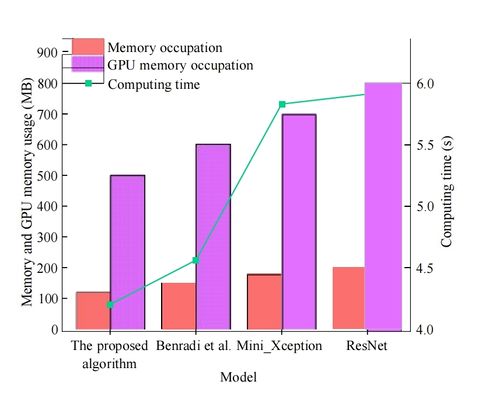

In the context of relevant CNN research, Sakai et al. [4] employed graph CNN to anticipate the pharmacological behavior of chemical structures, utilizing the constructed model for virtual screening and the identification of a novel serotonin transporter inhibitor. The efficacy of this new compound is akin to that of in-vitro- marketed drugs and has demonstrated antidepressant effects in behavioral analyses. Rački et al. [5] utilized CNN to investigate surface defects in solid oral pharmaceutical dosage forms. The proposed structural framework is evaluated for performance, demonstrating cutting-edge capabilities. The model attains remarkable performance with just 3% of parameter computations, yielding an approximate eight fold enhancement in drug property identification efficiency. Yoon et al. [6] employed CNN and generative adversarial networks to synthesize and explore colonoscopy imagery through the development of a proficiently trained system using imbalanced polyp data. Generative adversarial networks were harnessed to synthesize high-resolution comprehensive endoscopic images. The findings reveal that the system augmented with synthetic image enhancement exhibits a 17.5% greater sensitivity in image recognition. Benradi et al. [7] introduced a hybrid approach for facial recognition, melding CNN with feature extraction techniques. Empirical outcomes validate the method's efficacy in facial recognition, significantly enhancing precision and recall. Ahmad et al. [8] proposed a methodology for recognizing human activities grounded in deep temporal learning. The amalgamation of CNN features with bidirectional gated recurrent units, along with the application offeatureselection strategies, enhances accuracy and recall rates. Experimental results underscore the method's substantial practicality and accuracy in human activity recognition. | In the context of relevant CNN research, Sakai et al. [4] employed graph CNN to anticipate the pharmacological behavior of chemical structures, utilizing the constructed model for virtual screening and the identification of a novel serotonin transporter inhibitor. The efficacy of this new compound is akin to that of in-vitro- marketed drugs and has demonstrated antidepressant effects in behavioral analyses. Rački et al. [5] utilized CNN to investigate surface defects in solid oral pharmaceutical dosage forms. The proposed structural framework is evaluated for performance, demonstrating cutting-edge capabilities. The model attains remarkable performance with just 3% of parameter computations, yielding an approximate eight fold enhancement in drug property identification efficiency. Yoon et al. [6] employed CNN and generative adversarial networks to synthesize and explore colonoscopy imagery through the development of a proficiently trained system using imbalanced polyp data. Generative adversarial networks were harnessed to synthesize high-resolution comprehensive endoscopic images. The findings reveal that the system augmented with synthetic image enhancement exhibits a 17.5% greater sensitivity in image recognition. Benradi et al. [7] introduced a hybrid approach for facial recognition, melding CNN with feature extraction techniques. Empirical outcomes validate the method's efficacy in facial recognition, significantly enhancing precision and recall. Ahmad et al. [8] proposed a methodology for recognizing human activities grounded in deep temporal learning. The amalgamation of CNN features with bidirectional gated recurrent units, along with the application offeatureselection strategies, enhances accuracy and recall rates. Experimental results underscore the method's substantial practicality and accuracy in human activity recognition. | ||

Revision as of 06:26, 10 December 2024

Abstract

In exploring the performance-enhancing effects of compression sportswear, this study investigates its impact on trunk muscle activation during core stability training, with a particular focus on the biomechanical implications of this relationship. This research posits the existence of an Equilibrium Point of Motion (EPM) and employs surface Electromyography (EMG) to measure muscular responses in the Erector Spinae (ES), External Oblique (EO), and Rectus Abdominis (RA) during exercises performed with and without compression wear. Results revealed that compression garments significantly augment root mean square (RMS) values for ES and EO muscles, suggesting differential muscle activation patterns. Further, the application of OpenSim modeling of full-body musculoskeletal mechanics facilitated a novel analysis of muscle forces and activations, enhancing the understanding of sportswear functionality in an ergonomic context. This approach uncovered significant correlations between actual and simulated muscle activations, particularly for the ES and EO during a gluteal bridge exercise. These insights contribute to the development of ergonomically-engineered sportswear aimed at optimizing athletic performance and provide a valuable reference for future sportswear design and research.

Keywords: Sportswear; Model Simulation; Surface-Electromyography; Core training; Tight shorts; Compression

1. Introduction

Tight-fitting sportswear has received much attention due to its effect on the body's performance, which is related to the mechanics of contraction of pressure and activity [1,2]. The core stability training lies at the heart of many aspects of fitness and professional sports, in addition, to an evolving emphasis on functional integration for dynamic athletic performance [3].

Core stability training is a mode of exercise focused on strengthening the trunk muscles, which include the abdomen, back, pelvis, and hips, and also is clouded by sportswear shorts [4, 5, 6,7]. Two main methods to monitor or evaluate performance are subjective assessment of core stability through observation and objective measurement of biofeedback, including electromyography, motion capture, and further calculation or simulation of torque, and strength [8, 9]. Many researchers have supported some positive effects of the sportswear pressure impact on the overall impact of sportswear on the sensorimotor system and may decrease muscle soreness and pain [10, 11]. There remains a lack of detailed exploration into specific areas. Whereas, the effect mechanisms and extent of tight-fitting shorts are unclear to the performance of body core stability, focusing on the abdomen and waist region [12, 13]. To further explore the association between sportswear and body performance, comparing different wear conditions in experimental data.

Previous studies encompass the impact of wear conditions on core dynamics, ranging from the influence of footwear on muscle response time to the differentiated effects of wearable products on specific muscle groups [14,15]. Lee and Do distinguish tight-fitting shorts from compression stockings [16]. Their evaluation of the functions of these products, with a specific focus on the lower back during core training. This research suggests that the unified recruitment of abdominal and back muscles, coupled with additional support to erector spinae (ES), rectus abdominis (RA), and external oblique (EO), can be achieved through these wearables [17]. Maximal voluntary isometric contraction and peak muscle power after motion were greater than without compression garments with a slight effect [2] It provides a perspective on wearable products' potential impact on specific muscle groups during core training [18,19]. Because compression garment materials and pressures may alter the response to movement, previous reviews recommended that all compression garment studies measure and report pressures at multiple sites and specify the materials used [10,20].

While studies have reported positive effects, such as reduced muscle soreness and pain, there is a relative paucity of research on how these garments specifically affect core stability, particularly in the lower back and abdominal region. To address this gap, our study concentrates on a largely unexplored aspect: the activation patterns of core muscles, with an emphasis on the lumbar region, during core stability exercises while wearing compression shorts. This focus provides a novel vantage point by isolating the lower back area, a crucial element in core training, yet often overlooked in compression garment studies.

Despite extensive research on the biomechanical impact of tight sportswear, previous studies have predominantly centered on the generalized effects of sportswear pressure on muscle response and sensorimotor function. Significant gaps remain in our understanding, particularly concerning the activation patterns of muscles in the lower back and waist area during core stability exercises. This paper proposes to fill these gaps by exploring the specific biomechanical and ergonomic impacts of lower back compression afforded by tight-fitting shorts. This represents an innovative direction in textile performance research, with the potential to deepen our grasp of how compression garments influence core muscle activation, with implications for both athletic performance optimization and the design of sportswear that supports the lower back.

This research is pioneering in that it not only documents the muscle activation patterns but also quantifies the degree of compression and its direct correlation with muscle activation in the lumbar region. This duality in focus – examining both the physical pressure exerted by the garment and the physiological response of the body – marks a significant departure from previous work, which often neglects the lower back coverage and its specific activation during core exercises.

In recent years, in the field of research on sports biomechanics and muscle structure simulation, various methods and kinetic simulation software applications have provided insights into understanding muscle activity, muscle geometry, and muscle performance when subjected to loads. Stokes and Gardner-Morse constructed a mathematical model incorporating the abdominal muscles and performing optimization calculations with Matlab software [21]. It revealed how abdominal muscle activity reduces the load on the spine by increasing intra-abdominal pressure. Beaucage and Gauvreau estimated the forces on the lower lumbar spine during symmetric and asymmetric weightlifting tasks using OpenSim software [22]. The study revealed the specific effects of various tasks on spinal forces involving the gluteus maximus, psoas maximus, and paravertebral muscle groups, which provided new perspectives on the assessment of exercise mechanics loading.

Branyan and Menguc synthesized a personalized anatomical curve muscle geometry model to simulate the mechanical behavior of muscles such as latissimus dorsi, extensor spinae, rectus abdominis, and obliquus abdominis [23]. The geometric model of curved muscles was also mapped by incorporating muscle geometry, moment arms, and fiber direction paths. Guo and Ren refined and optimized the microfilm element embedded in a flexible multibody dynamics model to enhance the understanding of the role of the core musculature in regulating the pressure distribution and stability of the spine [24]. The model included core muscle groups such as rectus abdominis, obliques, adductors, and multifidus. In summary, these studies, through the use of quantitative measurements and model simulation techniques, provide a simulation basis for a comprehensive understanding of the behavior of human muscles during exercise states and the interactions between muscles and bones, which in turn helps to facilitate the optimization of sports equipment design. Key research results and major findings of previous researchers provide valuable references in the field of muscle biomechanics modeling and simulation analysis. This study seeks to reveal how varying levels of tightness and the anatomical fit of the shorts could modulate this muscle activity, thereby contributing to a more targeted approach in the design of compression sportswear. The ultimate aim is to provide empirical data that could lead to enhanced ergonomic design of sportswear, precisely engineered to improve core training outcomes and reduce injury risk associated with lower back strain. This paper advocated that the relationship between the compression of sportswear and subject ergonomic aids and mechanisms should be further enhanced by achieving an equilibrium of muscle activation and pressure level.

2. Methodology

2.1 Subjects

The experiment was approved by the institution’s human research ethics committee (EST-2024-001). Written informed consent was obtained from fifteen healthy male participants (22.4±2.7 years old, 68.5±1.6 kg, 178±2.2 cm). The study involved subjects' surface electromyography (EMG) during various exercises to measure muscle activity. EMG data were used to infer characteristics of muscular strength. All participants were healthy, and they had agreed to and understood the content of the experiment.

2.2. Standardized Compression

The study meticulously detailed the protocol implemented to ensure that each subject experienced a similar level of compression from the tight-fit shorts. Different sizes of shorts were provided to the subjects according to their somatotypes to ensure consistent clothing pressure. The clothing pressure experienced by the subjects was measured to confirm uniformity and compared against the pressure of cotton shorts, which served as a no-pressure control.

2.3. Instrumentation

2.3.1. Subjective Clothing Pressure Comfort Evaluation

Subjects were instructed to wear standardized tight-fit shorts for consistency. Following a tactile test, subjects completed a questionnaire regarding the comfort of the fabric. This subjective evaluation data was compiled and analyzed to compare comfort performance across various fabric types. Feedback on perceived compression was recorded, providing qualitative data to complement the quantitative analysis. Data analysis included assessing averaged pressure values and inter-subject variability to confirm a standardized perception of tightness among all participants.

2.3.2. Electromyography

Surface electromyography (EMG) was used to capture muscle activity during different core training exercises. EMG data were collected using the Delsys Trigno Avanti sensor hardware and EMGworks software (version EW4, Inc, USA) at a high sampling rate of 1092 Hz. Subjects participated under two wear conditions: tight-fitting sports shorts and cotton shorts without pressure. This aimed to explore the impact of sportswear on muscle activation. Table 1 provides an overview of the placement of EMG sensors on various muscles.

Table 1 Placement of EMG Sensors on Muscles in the Human Body

|

EMG(NO.) |

Position |

Muscle |

Illustration |

|

1 |

left |

Rectus Abdominis |

Back Front |

|

2 |

right |

Rectus Abdominis | |

|

3 |

left |

External Oblique | |

|

4 |

right |

External Oblique | |

|

5 |

right |

Erector Spinae | |

|

6 |

left |

Erector Spinae |

2.3.3. Testing Sport Shorts

The tight-fit shorts were selected and standardized to ensure each subject experienced uniform compression according to their somatotypes. The shorts' compression attributes were indicated by their elastic modulus in both warp and weft directions. Comparative analyses were conducted against control garments (cotton shorts with no compression features). This approach ensured a comparative analysis to discern potential differences in muscle activation patterns based on the type of sportswear worn during core exercises. Table 2 illustrates the fabric content of pants provided to participants.

Table 2 Detail of Various Garments Provided to Participants

|

Nylon Content (%) |

Spandex Content (%) |

Longitudinal Elasticity Modulus (MPa) |

Latitudinal Elasticity Modulus (MPa) |

Subjective Comfort Score |

Compression Score | |

|

88 |

12 |

166.62 |

106.70 |

4.2 |

4.5 | |

|

Cotton Content (%) | ||||||

|

100 | ||||||

2.3.4. Motion Capture

Inverse kinematics values for actual motion capture inputs in OpenSim. Optical motion capture system that captures data from the subject during hip bridge movements. When performing hip bridge motion capture experiments, the marker points were determined based on anatomical knowledge and in conjunction with the bony prominence points of the human body (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of reflective dots attached to the human body

2.4. Experiment Protocol

The experimental protocol was meticulously designed to ensure consistency, accuracy, and reproducibility in investigating EMG responses during core training exercises. Participants were briefed on the study's objectives and provided informed consent. Before starting the exercises, participants underwent a standardized warm-up routine to minimize injury risk and ensure optimal muscle activation. This routine included light activity and specific dynamic stretches targeting core muscle groups.

Participants performed a series of core training exercises (Table 3), including the gluteal bridge and seated leg raise [25]. Each exercise was repeated for a predetermined number of sets and repetitions. To control for rhythm and cadence during exercise execution, participants were provided with auditory cues from electronic metronomes set to 60 bpm. This control minimized variability in muscle activation patterns, ensuring observed differences were due to sportswear type rather than movement cadence [26].

Table 3 Demonstration of each exercise and details in number of sets, repetitions, and rest intervals

|

No |

Motion |

Procedure |

Repeat time |

Count |

Rest (s) | ||

|

Start position |

End position | ||||||

|

1 |

Gluteal bridge (GB) |

10 |

3 |

60 | |||

|

2 |

Seated leg raise (SLR) |

10 |

3 |

60 | |||

For the gluteal bridge (GB):

- Initial position: Subject lay on their back with knees bent, supported by heels, elbows, and head.

- Process: Lift the waist, arch the body so that hips are raised, and abdomen levels with knees, then slowly lower to the initial posture.

For the seated leg raise (SLR):

- Initial position: Lean back to maintain balance and keep the lower back straight.

- Process: Contract abdominal muscles, lean back slightly to maintain balance, and bend knees to lift legs [27].

The comprehensive experiment protocol, including standardized warm-up, exercise demonstration, controlled repetitions, and rhythm management, contributed to the robustness and validity of the observed EMG responses to varying sportswear conditions.

Data were analyzed using EMGworks Analysis software. EMG signals from six muscles were calculated in absolute value and filtered using a Butterworth bandwidth between 4 and 400 Hz. RMS procedures were applied, and data were subsetted by time point. Motion EMG data were averaged using SPSS to compare different wear conditions. Amplifiers (Trigno Wireless System, Delsys Inc., Boston, USA) were used for all participants. Peak and mean muscle activity were averaged for the right and left muscles. Ten repetitions were analyzed and averaged to form an "ensemble average" curve, summarizing typical movement characteristics. RMS was used for the time normalization of repetition cycles.

Analysis was performed using repeated measures ANOVA in SPSS (version, IBM Institute Inc., NC) with two within-subject factors (wear status, and exercise motion) [2]. As Mauchly’s test of sphericity did not satisfy the assumptions, the results were based on multivariate ANOVA. The study aimed to compare the impact of tight-fitting sports shorts on athlete performance during core training exercises, extending findings on the impact of sportswear on biomechanical aspects [9].

Our findings support functional sports device design and contribute to rehabilitation research with smart garments [28]. The repeated ANOVA of six EMG zones identified distinct patterns in motion curves when participants wore tight-fitting shorts compared to loose-fitting cotton underwear.

3. Results

3.1 Impact of Compression Garments on RMS

The examination of various wear statuses during core training revealed substantial variability in RMS values compared to instances involving cotton shorts and tight shorts. As depicted in Table 4, there were significant differences in almost all measurements (RMSRA, RMSEO, and RMSES (sig=0.000<0.05) for both the wearing state and the motor task. the state of dress and the motor task had a significant effect on the measurements, with the specific effect size being measured by the partial Eta square. It is important to note that the observed power in Table 5 (Wear status: 285.534, Exercise motion: 2968.996) is also high, indicating that different exercise motions could be influential in our findings.

Table 4 Multivariate Tests of Muscle RMS Value Between-subjects Effects and In-subject Comparison Testing

|

Effect |

Method |

Value |

Sig. |

Partial Eta Squared |

Observes Power |

|

Wear status |

Pillai’s Trace Wilk’s Lambda Hotellin’s Trace Roy’s Largest Root |

0.817 0.183 4.461 4.461 |

0.000 |

0.817 |

285.534 |

|

Exercise motion |

Pillai’s Trace Wilk’s Lambda Hotellin’s Trace Roy’s Largest Root |

0.980 0.020 48.672 48.672 |

0.000 |

0.980 |

2968.996 |

Table 5 The Result of Multivariate Testing

|

Effects |

Muscle |

Sig. |

Partial Eta Squared |

Observes Power |

|

Wear status |

RMSRA |

0.000 |

0.455 |

1.000 |

|

RMSEO |

0.000 |

0.383 |

1.000 | |

|

RMSES |

0.000 |

0.772 |

1.000 | |

|

Exercise motion |

RMSRA |

0.000 |

0.895 |

1.000 |

|

RMSEO |

0.000 |

0.941 |

1.000 | |

|

RMSES |

0.000 |

0.793 |

1.000 |

In exercise motion, we observed pronounced enhancements in the Erector Spinae (EO) muscles during the Straight Leg Raise (SLR) regimen across all groups and exercises. This phenomenon was particularly decreased when participants wore tight-fitting shorts, underscoring the potential impact of clothing on muscle engagement [41]. The muscles in the back group, specifically the erector spinae (ES), exhibited increased recruitment of muscle units during the hip bridge (HB) exercise. The primary functional contribution was attributed to ES, with relatively lesser involvement of the rectus abdominis (RA) and external oblique (EO).In the initial phase of the seated leg raise exercise, the activation of the erector spinae(EO) in the control group wearing cotton shorts and rectus abdominis (RA) in the group wearing shorts is modest. Notably, towards the middle and end of the exercise sequence, there was a significant surge in EO activation with cotton pants. A parallel trend was observed in RA during the latter part of the exercise. In comparison to muscles without tight-fitting shorts, RA's root mean square (RMS) value in wearing tight shorts demonstrated a more balanced and consistent level throughout the entire duration. This suggests that the utilization of tights may contribute to a more measured and evenly distributed strength training experience.

3.2 Validation and analysis of muscle activation simulation results

The measured muscle activation was calculated using electromyography (EMG) data. The muscle forces calculated from the simulation were synchronized to correspond with the muscle activation values obtained from the EMG experiments. Each muscle was compared between the simulation-calculated muscle activation and the measured EMG activation. Trends and values of the two sets of results were analyzed. If the simulated activation shows a consistent trend with the measured EMG data and is numerically similar or can be reasonably calibrated to match, the model is considered to be relatively accurate.

The OpenSim model calculates the muscle joint moments by the static optimal solution method based on the results derived from reverse engineering [42,43]. The accuracy of the model and the consistency of the experimental data were assessed by constructing a model simulation of the core muscles of the low back in the hip-bridge movement (see Figure. 2, Figure. 3) and validating it in comparison with the experimental data of electromyography (EMG). The model including rectus abdominis, external abdominal obliques, and erector spinae was successfully modeled by the OpenSim multibody dynamics platform. The hip bridge maneuver was evaluated as an example to compare the trend of EMG signal curves with the simulated muscle force curves to verify the reasonableness of the established exercise biomechanics model.

Figure 2 Simulation of the core muscles during hip-bridge movements (initial state)

Figure 3 Simulation of the core muscles during hip-bridge (process state)

When comparing the ratio of the root-mean-square (RMS) value of electromyographic values during an actual movement to the maximum voluntary contraction (MVC), the unit usually used is the percentage, which represents the intensity of electromyographic activity as a relative value of the MVC. RMS, on the other hand, is usually measured in microvolts (µV), which directly reflects the change in amplitude of the electrical signal. For the muscle force data output from the OpenSim motion model, the units are usually Newtons (N). Since the strength of the EMG signal is not directly equivalent to the force produced by the muscle, a transformation or normalization method is required to correlate these two different measurements when making comparisons. Since the focus of the study was on the relative changes in muscle activity, this chapter chose to directly compare the trends of each of the two parts of the data without converting the force into units of the electrical signal. Despite the non-uniformity of the measures, the degree to which the model agrees with reality can be assessed qualitatively by analyzing the activity trend similarities and correlations.

In this study, the OpenSim multibody dynamics model was validated by comparing it with electromyography (EMG) experimental data. By comparing the muscle activation data in the model with the EMG data collected in the experiments one by one, the results showed that the two showed a high degree of consistency and maintained relatively close numerical proximity in terms of activation (Figure. 4, Figure.5, Figure. 6).

Figure 4 Comparison of EMG and simulated values of the erector spinae muscle

Figure 5 Comparison of EMG measurements of the external abdominal oblique muscle with simulated values

Figure 6 Comparison of electromyographic eigenvalues of the rectus abdominis muscle with simulated values

The lumbar back muscle force in the simulation calculation model corresponded to the root mean square amplitude data of EMG activities collected by the actual EMG.

4. Discussion

To investigate the impact of tight-fitting sports shorts on athlete performance during core training exercises, focusing on the electromyographic (EMG) activity of the rectus abdominis (RA), external oblique (EO), and erector spinae (ES) muscles. We established a novel measurement approach and aimed to contribute to the understanding of sportswear's ergonomic influence on musculoskeletal function in core training. Our methodology involved comparing EMG signals across different muscle groups, particularly emphasizing the potential variations in muscle activation patterns associated with the use of tight-fitting sports shorts during core training exercises. During core stability training, the RA, EO, and ES muscles were strengthened to achieve body stability. The effect mechanisms of the abdomen and lower back region are likely related to tights wearing [29]. It is therefore speculated that body core training muscle activation from focus is hardly negligible at the same level [30].

The findings presented a nuanced perspective on muscle activation. While no significant differences were observed in testing times for EMG activity in the RA group, the ES muscles exhibited weaker RMS volume and a flatter curve. This suggests a potential influence of sportswear on the engagement of specific muscle groups, particularly the ES muscles. Additionally, the study revealed intriguing patterns during the seat leg raise exercise, indicating that the engagement of the external oblique (EO) muscles was influenced by the characteristics of the tight-fitting shorts. This observation adds complexity to our understanding of how sportswear may affect muscles. The result may guide the design and development of compression garments for optimal performance and benefits during core training. The implications of our findings extend beyond the immediate scope of this study. The identified patterns in muscle activation provide valuable insights for the design of sportswear that aims to optimize muscle engagement during core training. This has practical applications not only in sports performance but also in rehabilitation, aligning with the growing interest in smart garment applications for health-related interventions. Furthermore, the observed differences in muscle activation patterns suggest that athletes and individuals engaging in core training exercises may benefit from sportswear tailored to specific muscle groups, potentially enhancing exercise performance and minimizing the risk of injury.

4.1. Influence of Compression Garments on RMS

There has been a limited focus on examining the functional effects of athletic shorts specifically tailored for core sports [8]. The neuromuscular efficiency of trunk muscles increases with trunk flexion (Weston et al., 2018). Consequently, one of the novel aspects of this research is its selection of a specific sport to conduct an in-depth analysis of the electromyography (EMG) activation patterns associated with wearing compression shorts during athletic performance [32,16]. The previous work has proved that pattern muscle movement of retraining. Results showed evidence that core exercise. However, the existing literature lacks a comprehensive investigation into the functionality of compression shorts during core sports activities [33,34].

To bridge this research gap, this study emphasizes and compares the effects of wearing compression shorts and non-compression shorts, specifically examining their influence on muscle activation patterns (as measured by EMG) during sporting activities. By evaluating the outcomes of this study, it becomes possible to establish the link between the results obtained and those of previous researchers, both their similarities and discrepancies. A similar conclusion of the overall results of the meta-analyses suggests a slight likelihood of the benefit of compression garments on exercise recovery [10,20]. The results suggest that compression garments may be recommended after resistance training or eccentric exercise to aid recovery of maximal strength, power, and endurance performance. Garment fabric deformation and generated internal stresses on the body have demonstrated that clothing pressure has a greater effect on relieving muscle fatigue. Our results are in general agreement with the previous study on wearing the tights status of the muscles implying a decreased EMG amplitude and the peak torque of muscle contractions decreased approximately, compared to the control group [35]. Our current findings expand prior work with trunk muscle of RA, ES, EO activation mode, and tight shorts in core training, which derived a decrease in muscle strength and a lower EMG activity in the control group [14].

4.2 Equilibrium Point of Motion (EPM)

The findings of this research demonstrate that wearing compression shorts during core sports activities elicits specific EMG activation patterns in the muscles involved. These observations are consistent with the existing research on compression garments and their influence on muscle activation. Nam measured that a garment wear pressure above 4 kPa is regarded as harmful to health [36], by considering the broader implications of sportswear on various aspects of athletic performance—such as fatigue mitigation. Former findings suggested that wearing compression short-tights with a pressure intensity of 15-20 mm Hg at the thigh can reduce the development of fatigue in thigh muscles during submaximal running exercise in healthy adult males [37,38].