| (15 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

==1 Introduction== | ==1 Introduction== | ||

| − | In mathematics, the term ''least squares'' refers to an approach for | + | In mathematics, the term ''least squares'' refers to an approach for “solving” overdetermined linear or nonlinear systems of equations. A common problem in science is to fit a model to noisy measurements or observations. Instead of solving the equations exactly, which in many problems is not possible, we seek only to minimize the sum of the squares of the residuals. |

| − | The algebraic procedure of the method of least squares was first published by Legendre in 1805 <span id='citeF-1'></span>[[#cite-1|[1]]]. It was justified as a statistical procedure by Gauss in 1809 <span id='citeF-2'></span>[[#cite-2|[2]]], where he claimed to have discovered the method of least squares in 1795 <span id='citeF-3'></span>[[#cite-3|[3]]]. Robert Adrian had already published a work in 1808, according to <span id='citeF-4'></span>[[#cite-4|[4]]]. After Gauss, the method of least squares quickly became the standard procedure for analysis of astronomical and geodetic data. There are several good accounts of the history of the invention of least squares and the dispute between Gauss and Legendre, as shown in <span id='citeF-3'></span>[[#cite-3|[3]]]. Gauss gave the method a theoretical basis in two memoirs <span id='citeF-5'></span>[[#cite-5|[5]]], where he proves the optimality of the least squares estimate without any assumptions that the random variables follow a particular distribution. In an article by Yves <span id='citeF-6'></span>[[#cite-6|[6]]] there is a survey of the history, development, and applications of least squares, including ordinary, constrained, weighted, and total least squares, where he includes information about fitting curves | + | The algebraic procedure of the method of least squares was first published by Legendre in 1805 <span id='citeF-1'></span>[[#cite-1|[1]]]. It was justified as a statistical procedure by Gauss in 1809 <span id='citeF-2'></span>[[#cite-2|[2]]], where he claimed to have discovered the method of least squares in 1795 <span id='citeF-3'></span>[[#cite-3|[3]]]. Robert Adrian had already published a work in 1808, according to <span id='citeF-4'></span>[[#cite-4|[4]]]. After Gauss, the method of least squares quickly became the standard procedure for analysis of astronomical and geodetic data. There are several good accounts of the history of the invention of least squares and the dispute between Gauss and Legendre, as shown in <span id='citeF-3'></span>[[#cite-3|[3]]] and references therein. Gauss gave the method a theoretical basis in two memoirs <span id='citeF-5'></span>[[#cite-5|[5]]], where he proves the optimality of the least squares estimate without any assumptions that the random variables follow a particular distribution. In an article by Yves <span id='citeF-6'></span>[[#cite-6|[6]]] there is a survey of the history, development, and applications of least squares, including ordinary, constrained, weighted, and total least squares, where he includes information about fitting curves and surfaces from ancient civilizations, with applications to astronomy and geodesy. |

| − | The basic modern numerical methods for solving linear least squares problems were developed in the late | + | The basic modern numerical methods for solving linear least squares problems were developed in the late 1960s. The <math display="inline">QR</math> decomposition by Householder transformations was developed by Golub and published in 1965 <span id='citeF-7'></span>[[#cite-7|[7]]]. The implicit <math display="inline">QR</math> algorithm for computing the singular value decomposition (SVD) was developed by Kahan, Golub, and Wilkinson, and the final algorithm was published in 1970 <span id='citeF-8'></span>[[#cite-8|[8]]]. Both fundamental matrix decompositions have since been developed and generalized to a high level of sophistication. Since then great progress has been made in methods for generalized and modified least squares problems in direct, and iterative methods for large sparse problems. Methods for total least squares problems, which allow errors also in the system matrix, have been systematically developed. |

| − | In this work we aim to give a simple overview of least squares for curve fitting. The idea is to illustrate, for a broad audience, the mathematical foundations and practical methods to solve this simple problem. Particularly, we will consider four methods: the normal equations method, the QR approach, the singular value decomposition (SVD), as well as a more recent approach based on neural networks. The last one has not been used as frequently as the classical ones, but it is very interesting because in modern days it has become a very important tool in many | + | In this work we aim to give a simple overview of least squares for curve fitting. The idea is to illustrate, for a broad audience, the mathematical foundations and practical methods to solve this simple problem. Particularly, we will consider four methods: the normal equations method, the QR approach, the singular value decomposition (SVD), as well as a more recent approach based on neural networks. The last one has not been used as frequently as the classical ones, but it is very interesting because in modern days it has become a very important tool in many fields of modern knowledge, like data science (DS), machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI). |

==2 Linear least squares for curve fitting and the normal equations== | ==2 Linear least squares for curve fitting and the normal equations== | ||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

There are many problems in applications that can be addressed using the least squares approach. A common source of least squares problems is curve fitting. This is the one of the simplest least squares problems, but still it is a very fundamental problem, which contains all important ingredients of commonly ill posed problems and, even worse, they may be ill conditioned and difficult to compute with good precision using finite (inexact) arithmetic in modern computer devices. We start with the linear least squares problem. | There are many problems in applications that can be addressed using the least squares approach. A common source of least squares problems is curve fitting. This is the one of the simplest least squares problems, but still it is a very fundamental problem, which contains all important ingredients of commonly ill posed problems and, even worse, they may be ill conditioned and difficult to compute with good precision using finite (inexact) arithmetic in modern computer devices. We start with the linear least squares problem. | ||

| − | + | Let’s assume that we have <math display="inline">m</math> noisy experimental observations (points) | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> (t_1,\ | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> (t_1,\hat{y}_1), (t_2,\hat{y}_2),\ldots ,(t_m,\hat{y}_m), </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | which relate two real quantities, as shown in figure [[#img-2|2]]. We want to fit a curve, represented by a real scalar function <math display="inline">y(t)</math>, to the given data. A linear model for the unknown curve can be represented as a linear combination of given (known) base functions <math display="inline">\phi _1</math>, <math display="inline">\phi _1</math>,...,<math display="inline">\phi _n</math>: | |

<span id="eq-1"></span> | <span id="eq-1"></span> | ||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>y(t) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>y(t) = c_1\phi _1(t) +c_2\phi _2(t)+ \ldots +c_n\phi _n(t) , </math> |

|} | |} | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (1) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (1) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | where <math display="inline"> | + | where <math display="inline">c_1,c_2,\ldots c_n</math> are unknown coefficients. A first naive approach to compute those coefficients is assuming that <math display="inline">\hat{y}_i = y(t_i)</math> for each <math display="inline">i = 1, 2,\ldots ,m</math>. This assumption yields the linear system <math display="inline">\hat{y}_i = c_1\phi _1(t_i) +c_2\phi _2(_i)+ \ldots + c_n\phi _n(t_i)</math>, <math display="inline">i=1,2, \ldots , m</math>, which can be represented as <math display="inline">A\,\mathbf{x}= \mathbf{b}</math>, where |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> A = \left[\begin{array}{cccc} \phi _1(t_1) &\phi _2(t_1) &\ldots &\phi _n(t_1)\\ \phi _1(t_2) &\phi _2(t_2) &\ldots &\phi _n(t_2) \\ \vdots & & \ddots & \vdots \\ \phi _1(t_m) &\phi _2(t_m) &\ldots &\phi _n(t_m) \end{array} \right], \qquad \mathbf{x}= \left[\begin{array}{c} c_1\\ c_2\\ \vdots \\c_n \end{array} \right], \qquad \mathbf{b}= \left[\begin{array}{c} \hat{y}_1\\ \hat{y}_2\\ \vdots \\\hat{y}_m \end{array} \right], </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | Depending on the problem or application, the base functions <math display="inline">\phi _j</math>, <math display="inline">1\le j \le n</math>, may be polynomials <math display="inline">\phi _j(t) = t^{j-1}</math>, exponentials <math display="inline">\phi _j(t) = e^{\lambda _j\, t}</math>, log-linear <math display="inline">\phi = K\,e^{\lambda \,t}</math>, among many others. | |

| − | + | There are some drawbacks and difficulties with the previous approach: vector <math display="inline">\mathbf{b}</math> must belong to the column space of <math display="inline">A</math>, denoted by <math display="inline">\operatorname{Col}(A)</math>, in order to get solution(s) of the linear system. The rank of <math display="inline">A</math> is <math display="inline">r = \dim \operatorname{Col}(A)</math>, and plays a important role. When <math display="inline">m>r</math>, most likely <math display="inline">\mathbf{b}\notin \operatorname{Col}(A)</math>, and the system has no solution; if <math display="inline">m<r</math>, the undetermined linear system has infinite many solutions; finally, when <math display="inline">m=r</math>, if the system has a solution, the computed curve produces undesirable oscillations, specially near the far right and left points, a well known phenomenon in approximation theory and numerical analysis, known as the Runge's phenomenon <span id='citeF-9'></span>[[#cite-9|[9]]], demonstrating that high degree interpolation does not always produce better accuracy. The least squares approach considers the residuals, which are the differences between the observations and the model values: | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | The residuals are the differences between the observations and the model values: | + | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| Line 70: | Line 57: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> r_i = | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> r_i = \hat{y}_i - \sum _{j=1}^n c_j\,\phi _j(t_i) \quad \hbox{or} \quad \mathbf{r}= \mathbf{b}- A\,\mathbf{x}. </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Ordinary least squares to find the best fitting curve <math display="inline">y(t)</math>, consists in finding <math display="inline">\mathbf{x}</math> that | + | Ordinary least squares to find the best fitting curve <math display="inline">y(t)</math>, consists in finding <math display="inline">\mathbf{x}</math> that minimizes the sum of squared residuals |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| Line 81: | Line 68: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \| \mathbf{r}\| ^2 = \sum _{j=1}^n r_i^2 = \Vert \mathbf{b}- A\,\mathbf{x}\Vert ^2 | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \| \mathbf{r}\| ^2 = \sum _{j=1}^n r_i^2 = \Vert \mathbf{b}- A\,\mathbf{x}\Vert ^2. </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | The least squares criterion has important statistical interpretations, since the residual <math display="inline">r_i</math> in | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| Line 92: | Line 79: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \hat{y}_i = y(t_i) + r_i, </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | may be considered as | + | may be considered as a measurement error with a given probabilistic distribution. In fact, least squares produces what is known as the maximum-likelihood estimate of the parameter estimation of the given distribution. Even if the probabilistic assumptions are not satisfied, years of experience have shown that least squares produces useful results. |

===2.1 The normal equations=== | ===2.1 The normal equations=== | ||

| Line 115: | Line 102: | ||

and the best fitting curve, of the form ([[#eq-1|1]]), is obtained with the coefficients <math display="inline">\widehat{\mathbf{x}} = [ \widehat{c}_1, \ldots , \widehat{c}_n]^T</math>. The linear system ([[#eq-2|2]]) can be solved computationally using the Cholesky factorization or conjugate gradient iterations (for large scale problems). | and the best fitting curve, of the form ([[#eq-1|1]]), is obtained with the coefficients <math display="inline">\widehat{\mathbf{x}} = [ \widehat{c}_1, \ldots , \widehat{c}_n]^T</math>. The linear system ([[#eq-2|2]]) can be solved computationally using the Cholesky factorization or conjugate gradient iterations (for large scale problems). | ||

| − | Example 1: The best fitting polynomial of degree <math display="inline">n-1</math>, say <math display="inline">y(t) = c_1 + c_2 t + \cdots + c_{n} t^{n-1}</math>, to a set of <math display="inline">m</math> data points <math display="inline">(t_1,\, | + | Example 1: The best fitting polynomial of degree <math display="inline">n-1</math>, say <math display="inline">y(t) = c_1 + c_2 t + \cdots + c_{n} t^{n-1}</math>, to a set of <math display="inline">m</math> data points <math display="inline">(t_1,\,\hat{y}_1),\,(t_2,\,\hat{y}_2), \ldots ,\,(t_m,\,\hat{y}_m)</math> is obtained solving the normal equations ([[#eq-2|2]]), where the design matrix is the Vandermonde matrix |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| Line 127: | Line 114: | ||

A sufficient condition for <math display="inline">A</math> to be full rank is that <math display="inline">t_1, \ldots ,t_m</math> be all different, which may be proved using mathematical induction. | A sufficient condition for <math display="inline">A</math> to be full rank is that <math display="inline">t_1, \ldots ,t_m</math> be all different, which may be proved using mathematical induction. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Remark 1: Rank deficient least squares problems, where the design matrix <math display="inline">A</math> has linearly dependent columns, can be solved with specialized methods, like truncated singular value decomposition (SVD), regularization methods, <math display="inline">QR</math> decomposition with pivoting, and data filtering, among others. These difficulties are studied and understood more clearly when we start from basic principles. So, in order to keep the discussion easy we first consider the simplest case, where matrix <math display="inline">A</math> is full rank, although it may be very ill-conditioned or near singular. | ||

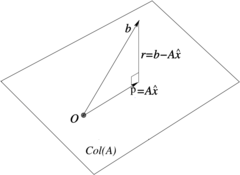

===2.2 An interpretation with orthogonal projections=== | ===2.2 An interpretation with orthogonal projections=== | ||

| Line 153: | Line 142: | ||

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image: | + | |[[Image:Review_960218438971-fig_01.png|240px|\operatornameCol(A) is orthogonal to the minimum residual \widehatr = b- A\,\widehatx = b- P<sub><sub>A</sub></sub>b.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | ''' | + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 1:''' <math>\operatorname{Col}(A)</math> is orthogonal to the minimum residual <math>\widehat{\mathbf{r}} = \mathbf{b}- A\,\widehat{\mathbf{x}} = \mathbf{b}- P_{_A}\mathbf{b}</math>. |

|} | |} | ||

===2.3 Instability of the normal equations method=== | ===2.3 Instability of the normal equations method=== | ||

| − | The normal equations approach is a very simple procedure to solve the linear least squares problem. It is the most used approach in the scientific and engineering community, and very popular in statistical software. However, it must be used with precaution, specially when the design matrix <math display="inline">A</math> is ill-conditioned and finite precision arithmetic in digital conventional devices is employed. In order to understand this phenomenon, it is convenient to show an example and then discuss the results. | + | The normal equations approach is a very simple procedure to solve the linear least squares problem. It is the most used approach in the scientific and engineering community, and very popular in statistical software. However, it must be used with precaution, specially when the design matrix <math display="inline">A</math> is ill-conditioned (or it is rank deficient) and finite precision arithmetic, in digital conventional devices, is employed. In order to understand this phenomenon, it is convenient to show an example and then discuss the results. |

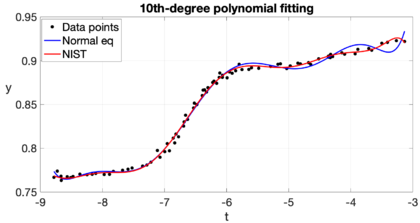

| − | Example 2: The National Institute of Standards and Technology (''NIST'') is a branch of the U.S. Department of Commerce responsible for establishing national and international standards. ''NIST'' maintains reference data sets for use in the calibration and certification of statistical software. On its website <span id='citeF- | + | Example 2: The National Institute of Standards and Technology (''NIST'') is a branch of the U.S. Department of Commerce responsible for establishing national and international standards. ''NIST'' maintains reference data sets for use in the calibration and certification of statistical software. On its website <span id='citeF-10'></span>[[#cite-10|[10]]] we can find the ''Filip'' data set, which consists of 82 observations of a variable <math display="inline">y</math> for different <math display="inline">t</math> values. The aim is to model this data set using a 10th-degree polynomial. This is part of exercise 5.10 in Cleve Molers' book <span id='citeF-11'></span>[[#cite-11|[11]]]. For this problem we have <math display="inline">m = 82</math> data points <math display="inline">(t_i, \hat{y}_i)</math>, and we want to compute <math display="inline">n = 11</math> coefficients <math display="inline">c_j</math> for the 10th-degree polynomial. The <math display="inline">m \times n</math> design matrix <math display="inline">A</math> has coefficients <math display="inline">a_{ij} = t_i^{j-1}</math>. In order to given an idea of the complexity of this matrix, we observe that its minimum coefficient is 1 and its maximum coefficient is a bit greater than <math display="inline">2.7\times 10^9</math>, while its condition number is <math display="inline">\kappa (A)\approx \mathcal{O}(10^{15})</math>. The matrix of the normal equations, <math display="inline">A^TA</math>, is a much smaller matrix of size <math display="inline">n\times n</math>, but ''more singular'', since its minimum and maximum coefficients (in absolute value) are close to 82 and <math display="inline">5.1\times 10^{19}</math>, respectively, with a very high condition number <math display="inline">\kappa (A^TA)\approx \mathcal{O}(10^{30})</math>. The matrix of the normal equations is highly ill-conditioned in this case because there are some clusters of data points very close to each other with almost identical <math display="inline">t_i</math> values. The computed coefficients <math display="inline">\widehat{c}_j</math> using the normal equations are shown in Table [[#table-1|1]], along with the certified values provided by ''NIST''. The ''NIST'' certified values were found solving the normal equations, but with multiple precision of 500 digits (which represents an idealization of what would be achieved if the calculations were made without rounding error). Our calculated values differ significantly from those of ''NIST'', even in the sign, the relative difference <math display="inline">\Vert \widehat{\mathbf{c}} - \mathbf{c}_{nist} \Vert / \Vert \mathbf{c}_{nist} \Vert </math> is about 118<math display="inline">%</math>. This dramatic difference is mainly because we are using finite arithmetic with 16-digit standard ''IEEE double precision'', and solving the normal equations with the Cholesky factorization yields a relative error amplified proportionately to the product of the condition number times the machine epsilon. The computed residual keeps reasonable, though. Figure [[#img-2|2]] shows ''Filip'' data along with the certified curve and our computed curve. The difference is most visible at the extremes, where our computed curve shows some pronounced oscillations. |

{| class="floating_tableSCP wikitable" style="text-align: center; margin: 1em auto;min-width:50%;" | {| class="floating_tableSCP wikitable" style="text-align: center; margin: 1em auto;min-width:50%;" | ||

| − | |+ style="font-size: 75%;" |<span id='table-1'></span> | + | |+ style="font-size: 75%;" |<span id='table-1'></span>Table. 1 Comparison of numerical results with the ''NIST'''s certified values. |

|- style="border-top: 2px solid;" | |- style="border-top: 2px solid;" | ||

| style="border-left: 2px solid;border-right: 2px solid;" | Polynomial coefficients | | style="border-left: 2px solid;border-right: 2px solid;" | Polynomial coefficients | ||

| Line 229: | Line 218: | ||

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image: | + | |[[Image:Review_960218438971-fig_02.png|420px|Computed polynomial curve along with ''NIST'''s certified one.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | ''' | + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 2:''' Computed polynomial curve along with ''NIST'''s certified one. |

|} | |} | ||

==3 Orthogonal projections and the QR factorization== | ==3 Orthogonal projections and the QR factorization== | ||

| − | The previous numerical results for solving a least square problem have shown instability for the normal equations approach, when the design matrix is ill-conditioned. However the normal equations approach usually yields good results when the problem is of moderate size as well as well-conditioned. For the cases where the design matrix is ill-conditioned the QR factorization method is an excellent alternative. The SVD factorization is convenient when the design matrix is rank deficient, as | + | The previous numerical results for solving a least square problem have shown instability for the normal equations approach, when the design matrix is ill-conditioned. However the normal equations approach usually yields good results when the problem is of moderate size as well as well-conditioned. For the cases where the design matrix is ill-conditioned the QR factorization method is an excellent alternative. The SVD factorization is convenient when the design matrix is rank deficient, as will be discussed below. |

===3.1 The QR factorization=== | ===3.1 The QR factorization=== | ||

| − | We begin with the following theorem in reference <span id='citeF- | + | We begin with the following theorem in reference <span id='citeF-9'></span>[[#cite-9|[9]]]. |

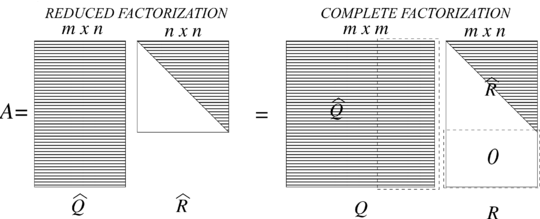

Theorem 1: Each <math display="inline">A \in \mathbb{C}^{m\times n} (m \ge n)</math> of full rank has a unique reduced <math display="inline">QR</math> factorization <math display="inline">A = \widehat{Q} \widehat{R}</math> with <math display="inline">r_{jj} > 0</math>. For simplicity we keep the discussion for the case <math display="inline">A\in \mathbb{R}^{m\times n}</math>. In this case <math display="inline">\widehat{Q}</math> is the same size than <math display="inline">A</math> and <math display="inline">\widehat{R} \in \mathbb{R}^{n\times n}</math> is upper triangular. Actually this factorization is a matrix version of the Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization algorithm. More precisely, let <math display="inline">\mathbf{a}_1,\mathbf{a}_2, \ldots ,\mathbf{a}_n \in \mathbb{R}^m</math> be the linear independent column vectors of <math display="inline">A</math> | Theorem 1: Each <math display="inline">A \in \mathbb{C}^{m\times n} (m \ge n)</math> of full rank has a unique reduced <math display="inline">QR</math> factorization <math display="inline">A = \widehat{Q} \widehat{R}</math> with <math display="inline">r_{jj} > 0</math>. For simplicity we keep the discussion for the case <math display="inline">A\in \mathbb{R}^{m\times n}</math>. In this case <math display="inline">\widehat{Q}</math> is the same size than <math display="inline">A</math> and <math display="inline">\widehat{R} \in \mathbb{R}^{n\times n}</math> is upper triangular. Actually this factorization is a matrix version of the Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization algorithm. More precisely, let <math display="inline">\mathbf{a}_1,\mathbf{a}_2, \ldots ,\mathbf{a}_n \in \mathbb{R}^m</math> be the linear independent column vectors of <math display="inline">A</math> | ||

| Line 346: | Line 335: | ||

where the projection matrices satisfy <math display="inline">P_{_{\widehat{Q}}} \mathbf{b}= P_{_A} \mathbf{b}</math> because the column space of <math display="inline">A</math> is equal to the column space of <math display="inline">\widehat{Q}</math>. | where the projection matrices satisfy <math display="inline">P_{_{\widehat{Q}}} \mathbf{b}= P_{_A} \mathbf{b}</math> because the column space of <math display="inline">A</math> is equal to the column space of <math display="inline">\widehat{Q}</math>. | ||

| − | A complete <math display="inline">QR</math> factorization of <math display="inline">A</math> goes further by adding <math display="inline">m-n</math> orthonormal columns to <math display="inline">\widehat{Q}</math>, and adding <math display="inline">m-n</math> rows of zeros to <math display="inline">\widehat{R}</math>, obtaining an orthogonal matrix <math display="inline">Q \in \mathbb{R}^{m\times m}</math> and an upper triangular matrix <math display="inline">R \in \mathbb{R}^{m\times n}</math> as shown in Figure [[#img-3|3]]. In the complete factorization the additional columns <math display="inline">\mathbf{q}_j</math>, <math display="inline">j = n+1, \ldots , m</math>, are orthogonal to the column space of <math display="inline">A</math>. Of course, the matrix <math display="inline">Q</math> is an orthogonal matrix, since <math display="inline">Q^T Q = I_m</math>, so <math display="inline">Q^{-1} = Q^T</math> <div id='img-3'></div> | + | A complete <math display="inline">QR</math> factorization of <math display="inline">A</math> goes further by adding <math display="inline">m-n</math> orthonormal columns to <math display="inline">\widehat{Q}</math>, and adding <math display="inline">m-n</math> rows of zeros to <math display="inline">\widehat{R}</math>, obtaining an orthogonal matrix <math display="inline">Q \in \mathbb{R}^{m\times m}</math> and an upper triangular matrix <math display="inline">R \in \mathbb{R}^{m\times n}</math> as shown in Figure [[#img-3|3]]. In the complete factorization the additional columns <math display="inline">\mathbf{q}_j</math>, <math display="inline">j = n+1, \ldots , m</math>, are orthogonal to the column space of <math display="inline">A</math>. Of course, the matrix <math display="inline">Q</math> is an orthogonal matrix, since <math display="inline">Q^T Q = I_m</math>, so <math display="inline">Q^{-1} = Q^T</math>. <div id='img-3'></div> |

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image: | + | |[[Image:Review_960218438971-fig_03.png|540px|The reduced and complete QR factorizations of A]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | ''' | + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 3:''' The reduced and complete <math>QR</math> factorizations of <math>A</math> |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 363: | Line 352: | ||

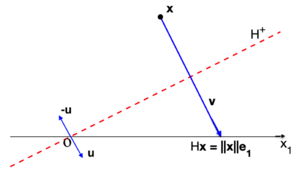

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

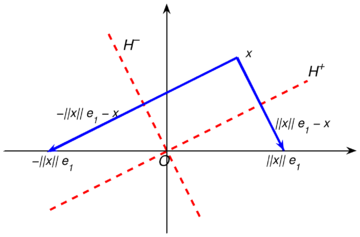

| − | |[[Image: | + | |[[Image:Review_960218438971-fig_04.png|300px|Householder reflection with vector v= ||x||\,e₁- x.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | ''' | + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 4:''' Householder reflection with vector <math>\mathbf{v}= ||\mathbf{x}||\,\mathbf{e}_1 - \mathbf{x}</math>. |

|} | |} | ||

This reflection reflects on a hyperplane <math display="inline">H^+</math> with normal unitary vector <math display="inline">\mathbf{u}</math>, and is given by | This reflection reflects on a hyperplane <math display="inline">H^+</math> with normal unitary vector <math display="inline">\mathbf{u}</math>, and is given by | ||

| Line 422: | Line 411: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> H_k = \left[\begin{array}{cc} I_{k | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> H_k = \left[\begin{array}{cc} I_{k} & \mathbb{O}^T \\ \mathbb{O} & H \end{array} \right]\,, </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | which is a symmetric orthogonal matrix (see <span id='citeF-12'></span>[[#cite-12|[12]]] for more details). Actually, for any vector <math display="inline">\mathbf{x}</math> there are two Householder refletions, as shown in Figure [[#img-5|5]], and each Householder matrix <math display="inline">H</math> is constructed with the election <math display="inline">\mathbf{v}= \operatorname{sign}(x_1) \| \mathbf{x}\| \,\mathbf{e}_1 + \mathbf{x}</math>. It is evident that this election allows <math display="inline">\| \mathbf{v}\| </math> to never be smaller than <math display="inline">\| \mathbf{x}\| </math>, avoiding cancellation by subtraction when dividing by <math display="inline">\Vert \mathbf{v}\Vert </math> to find <math display="inline">\mathbf{u}</math> in ([[#eq-5|5]]), thus ensuring stability of the method. | + | which is a symmetric orthogonal matrix (see <span id='citeF-12'></span>[[#cite-12|[12]]] for more details), <math display="inline">I_k</math> is the identity matrix of size <math display="inline">k \times k</math>, and <math display="inline">\mathbb{O}</math> is the zero matrix of size <math display="inline">(m-k) \times k</math>. Actually, for any vector <math display="inline">\mathbf{x}</math> there are two Householder refletions, as shown in Figure [[#img-5|5]], and each Householder matrix <math display="inline">H</math> is constructed with the election <math display="inline">\mathbf{v}= \operatorname{sign}(x_1) \| \mathbf{x}\| \,\mathbf{e}_1 + \mathbf{x}</math>. It is evident that this election allows <math display="inline">\| \mathbf{v}\| </math> to never be smaller than <math display="inline">\| \mathbf{x}\| </math>, avoiding cancellation by subtraction when dividing by <math display="inline">\Vert \mathbf{v}\Vert </math> to find <math display="inline">\mathbf{u}</math> in ([[#eq-5|5]]), thus ensuring stability of the method. |

<div id='img-5'></div> | <div id='img-5'></div> | ||

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image: | + | |[[Image:Review_960218438971-fig_05.png|360px|Two Huoseholder reflections, constructed from x.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | ''' | + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 5:''' Two Huoseholder reflections, constructed from <math>\mathbf{x}</math>. |

|} | |} | ||

| − | The above process is called ''Householder triangularization'' <span id='citeF-13'></span>[[#cite-13|[13]]], and currently it is the most widely used method for finding the <math display="inline">QR</math> factorization. There are two procedures to construct the reflection matrices: | + | The above process is called ''Householder triangularization'' <span id='citeF-13'></span>[[#cite-13|[13]]], and currently it is the most widely used method for finding the <math display="inline">QR</math> factorization. There are two procedures to construct the reflection matrices: ''Givens rotations'' and ''Householder reflections''. Here we have described only Householder reflections. For further insight, we refer the reader to <span id='citeF-14'></span>[[#cite-14|[14]]], <span id='citeF-12'></span>[[#cite-12|[12]]] and <span id='citeF-9'></span>[[#cite-9|[9]]]. |

We may compute the factorization <math display="inline">A=\widehat{Q} \widehat{R}</math>, with <math display="inline">\widehat{Q}=(H_n\cdots H_2H_1)^T</math>. However, if we are interested only in the solution of the least squares problem, we do not have to compute explicitly either matrices <math display="inline">H_k</math> or <math display="inline">\widehat{Q}</math>. We just find the factor <math display="inline">R</math> and store it in the same memory space occupied by <math display="inline">A</math>, and <math display="inline">\widehat{Q}^T\mathbf{b}</math> and store it in the same memory location occupied by <math display="inline">\mathbf{b}</math>. At the end, we solve the triangular system with backward substitution, as shown bellow. | We may compute the factorization <math display="inline">A=\widehat{Q} \widehat{R}</math>, with <math display="inline">\widehat{Q}=(H_n\cdots H_2H_1)^T</math>. However, if we are interested only in the solution of the least squares problem, we do not have to compute explicitly either matrices <math display="inline">H_k</math> or <math display="inline">\widehat{Q}</math>. We just find the factor <math display="inline">R</math> and store it in the same memory space occupied by <math display="inline">A</math>, and <math display="inline">\widehat{Q}^T\mathbf{b}</math> and store it in the same memory location occupied by <math display="inline">\mathbf{b}</math>. At the end, we solve the triangular system with backward substitution, as shown bellow. | ||

| Line 477: | Line 466: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | so we only need the vectors <math display="inline">\mathbf{v}</math> and <math display="inline">\mathbf{y}</math> at each step of the process. Numerical results are shown in Section 6. | |

==4 The singular value decomposition (SVD)== | ==4 The singular value decomposition (SVD)== | ||

| Line 542: | Line 531: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | respectively. The eigenvectors <math display="inline">\mathbf{v}_j</math> of <math display="inline">A^TA</math> are orthonormal. However, the eigenvectors of <math display="inline">A\,A^T</math> are only orthogonal (<math display="inline">(A\mathbf{v}_i)^TA\mathbf{v}_j = \mathbf{v}_i^T A^TA \mathbf{v}_j = \mathbf{v}_i^T \lambda _j \mathbf{v}_j = \lambda _j \delta _{ij}</math>), so we normalize them to get | + | respectively. The eigenvectors <math display="inline">\mathbf{v}_j</math> of <math display="inline">A^TA</math> are orthonormal. However, the eigenvectors of <math display="inline">A\,A^T</math> are only orthogonal (<math display="inline">(A\mathbf{v}_i)^TA\mathbf{v}_j = \mathbf{v}_i^T A^TA \mathbf{v}_j = \mathbf{v}_i^T \lambda _j \mathbf{v}_j = \lambda _j \delta _{ij}</math>), so we normalize them to get an orthonormal set <math display="inline">\mathbf{u}_1, \ldots ,\mathbf{u}_n</math> in <math display="inline">\mathbb{R}^m</math> |

<span id="eq-7"></span> | <span id="eq-7"></span> | ||

| Line 621: | Line 610: | ||

===4.3 Full SVD=== | ===4.3 Full SVD=== | ||

| − | In most applications, the reduced SVD decomposition is employed. However, in textbooks and many publications, the `'''full'''' SVD decomposition is used. | + | In most applications, the reduced SVD decomposition is employed. However, in textbooks and many publications, the `'''full'''' SVD decomposition is used. The reduced and full SVD are the same for <math display="inline">m = n</math>. We illustrate two cases: <math display="inline">m > n</math> and <math display="inline">m<n</math>. |

| − | * '''Case <math>m > n</math> | + | * '''Case <math>m > n</math>: the columns of the matrix <math>\widehat{U}</math> do not form a basis of''' <math display="inline">\mathbb{R}^m</math>. We augment <math display="inline">\widehat{U} \in \mathbb{R}^{m\times n}</math> to an orthogonal matrix <math display="inline">U\in \mathbb{R}^{m\times m}</math> by adding <math display="inline">m-n</math> orthonormal columns and replacing <math display="inline">\widehat{\Sigma } \in R^{n\times n}</math> by <math display="inline">\Sigma \in \mathbb{R}^{m\times n}</math> adding <math display="inline">m-n</math> null rows <math display="inline">\widehat{\Sigma }</math>: |

<span id="eq-11"></span> | <span id="eq-11"></span> | ||

| Line 642: | Line 631: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | * '''Case <math>m < n</math> | + | * '''Case <math>m < n</math>: the reduced decomposition is of the form''' <math display="inline">A = U\widehat{\Sigma }\widehat{V}^T</math>. The rows of <math display="inline">\widehat{V}^T</math> does not form a basis of <math display="inline">\mathbb{R}^n</math> so we must add <math display="inline">n-m</math> orthonormal rows to obtain an orthogonal matrix <math display="inline">V^T</math> and adding <math display="inline">n-m</math> null columns to <math display="inline">\widehat{\Sigma }</math> to get <math display="inline">\Sigma </math>: |

<span id="eq-12"></span> | <span id="eq-12"></span> | ||

| Line 679: | Line 668: | ||

===4.4 Computing the SVD=== | ===4.4 Computing the SVD=== | ||

| − | As stated in <span id='citeF- | + | As stated in <span id='citeF-9'></span>[[#cite-9|[9]]] (Lecture 23), the SVD of <math display="inline">A \in \mathbb{C}^{m\times n}</math> <math display="inline">(m>n)</math>, <math display="inline">A = U\,\Sigma \, V^*</math> is related to the eigenvalue decomposition of the covariance matrix <math display="inline">A^*A = V\,\Sigma ^*\Sigma \,V^*</math> and mathematically it may be calculated doing the following: |

<ol> | <ol> | ||

| Line 690: | Line 679: | ||

</ol> | </ol> | ||

| − | But the problem with this strategy is that the algorithm is not stable, mainly because it relies on the covariance matrix <math display="inline">A^*A</math>, which we have found before in the normal equations for least squares problems. Additionally, the eigenvalue problem in general is very sensitive to numerical perturbations in | + | But the problem with this strategy is that the algorithm is not stable, mainly because it relies on the covariance matrix <math display="inline">A^*A</math>, which we have found before in the normal equations for least squares problems. Additionally, the eigenvalue problem in general is very sensitive to numerical perturbations in computer’s finite precision arithmetic |

| − | An alternative stable way to | + | An alternative stable way to compute the SVD is to reduce it to an eigenvalue problem by considering a <math display="inline">2m\times 2m</math> Hermitian matrix and the corresponding eigenvalue system. |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| Line 705: | Line 694: | ||

since <math display="inline">A = U\Sigma V^*</math> implies <math display="inline">A\,V = U\Sigma </math> and <math display="inline">A^*U = V\,\Sigma </math>. Thus the singular values of <math display="inline">A</math> are the absolute values of the eigenvalues of <math display="inline">H</math>, and the singular vectors of <math display="inline">A</math> can be extracted from the eigenvectors of <math display="inline">H</math>, which can be done in an stable way, contrary to the previous strategy. This Hermitian eigenvalue problems are usually solved by a two-phase computation: first reduce the matrix to tridiagonal form, then diagonalize the tridiagonal matrix. The reduction is done by similarity unitary transformations, so the diagonal matrix contains the information about the singular values. | since <math display="inline">A = U\Sigma V^*</math> implies <math display="inline">A\,V = U\Sigma </math> and <math display="inline">A^*U = V\,\Sigma </math>. Thus the singular values of <math display="inline">A</math> are the absolute values of the eigenvalues of <math display="inline">H</math>, and the singular vectors of <math display="inline">A</math> can be extracted from the eigenvectors of <math display="inline">H</math>, which can be done in an stable way, contrary to the previous strategy. This Hermitian eigenvalue problems are usually solved by a two-phase computation: first reduce the matrix to tridiagonal form, then diagonalize the tridiagonal matrix. The reduction is done by similarity unitary transformations, so the diagonal matrix contains the information about the singular values. | ||

| − | Actually, this strategy has been standard for computing the SVD since the work of Golub and Kahan in the 1960s <span id='citeF-16'></span>[[#cite-16|[16]]]. The method involves in phase 1 applying Householder reflections alternately from the left and right of the matrix to reduce it to an upper bidiagonal form. In phase 2, the SVD of the bidiagonal matrix is determined with a variant of the QR algorithm. More recently, divide-and-conquer algorithms <span id='citeF-17'></span>[[#cite-17|[17]]] have | + | Actually, this strategy has been standard for computing the SVD since the work of Golub and Kahan in the 1960s <span id='citeF-16'></span>[[#cite-16|[16]]]. The method involves in phase 1 applying Householder reflections alternately from the left and right of the matrix to reduce it to an upper bidiagonal form. In phase 2, the SVD of the bidiagonal matrix is determined with a variant of the QR algorithm. More recently, divide-and-conquer algorithms <span id='citeF-17'></span>[[#cite-17|[17]]] have become the standard approach for computing the SVD of dense matrices in practice. These strategies overcome the computational difficulties associated with ill-conditioned or rank-deficient matrices during the SVD calculations. |

===4.5 Least squares with SVD=== | ===4.5 Least squares with SVD=== | ||

| − | Most of the software environments like ''MATLAB'' and ''Phyton'' incorporate very efficient algorithms and state of the art tools related to SVD. So, using those routines provide reasonable accurate results in most of the cases. | + | Most of the software environments, like ''MATLAB'' and ''Phyton'', incorporate very efficient algorithms and state of the art tools related to SVD. So, using those routines provide reasonable accurate results in most of the cases. |

| − | Concerning linear least squares problems, we know that often leads to | + | Concerning linear least squares problems, we know that this often leads to an inconsistent overdetermined system <math display="inline">A\mathbf{x}= \mathbf{b}</math> with <math display="inline">A\in \mathbb{R}^{m\times n}</math>, <math display="inline">m\ge n</math>. Thus, we seek the minimum of the residual <math display="inline">\mathbf{r}= \mathbf{b}- A\mathbf{x}</math>. We know that if <math display="inline">A</math> is of full rank <math display="inline">r=n</math>, then <math display="inline">A^TA</math> is positive definite symmetric and the least squares solution is given by |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| Line 762: | Line 751: | ||

With this definition <math display="inline">A^{\dagger }</math> is well defined and it has the same size as <math display="inline">A^T</math>. If <math display="inline">A</math> is full rank, then <math display="inline">A^{\dagger }</math> is called the left inverse of <math display="inline">A</math> since <math display="inline">A^{\dagger } A = I_n</math>, and <math display="inline">P_{_A} = A A^{\dagger }</math> defines the projection onto the column space of <math display="inline">A</math>. When <math display="inline">A</math> is an invertible square matrix <math display="inline">A^{\dagger } = A^{-1}</math>. | With this definition <math display="inline">A^{\dagger }</math> is well defined and it has the same size as <math display="inline">A^T</math>. If <math display="inline">A</math> is full rank, then <math display="inline">A^{\dagger }</math> is called the left inverse of <math display="inline">A</math> since <math display="inline">A^{\dagger } A = I_n</math>, and <math display="inline">P_{_A} = A A^{\dagger }</math> defines the projection onto the column space of <math display="inline">A</math>. When <math display="inline">A</math> is an invertible square matrix <math display="inline">A^{\dagger } = A^{-1}</math>. | ||

| − | '''Fitting data to a polynomial curve'''. Given the point set <math display="inline">(t_1, | + | '''Fitting data to a polynomial curve'''. Given the point set <math display="inline">(t_1,\hat{y}_1), \ldots , (t_m,\hat{y}_m)</math>. The algorithm for calculating <math display="inline">\widehat{\mathbf{x}} \in \mathbb{R}^{n+1}</math>, with the coefficients of the polynomial of degree <math display="inline">n</math>, consists of the following steps: |

<ol> | <ol> | ||

| Line 769: | Line 758: | ||

<li>Compute the SVD of <math display="inline">A = U\,\Sigma V^T</math>. Actually, the reduced SVD, <math display="inline">A = \widehat{U}\widehat{\Sigma }V^T</math>, is sufficient. </li> | <li>Compute the SVD of <math display="inline">A = U\,\Sigma V^T</math>. Actually, the reduced SVD, <math display="inline">A = \widehat{U}\widehat{\Sigma }V^T</math>, is sufficient. </li> | ||

<li>Calculate the generalized inverse <math display="inline">A^\dagger = V\,\Sigma ^\dagger U^T</math>. </li> | <li>Calculate the generalized inverse <math display="inline">A^\dagger = V\,\Sigma ^\dagger U^T</math>. </li> | ||

| − | <li>Calculate <math display="inline">\widehat{\mathbf{x}} = A^\dagger \mathbf{b}</math>, with <math display="inline">\mathbf{b}= \{ | + | <li>Calculate <math display="inline">\widehat{\mathbf{x}} = A^\dagger \mathbf{b}</math>, with <math display="inline">\mathbf{b}= \{ \hat{y}_j\} _{j=1}^m</math> being the vector of observations. </li> |

</ol> | </ol> | ||

| Line 779: | Line 768: | ||

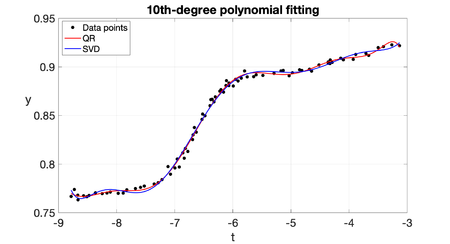

As before we consider the ''Filip'' data set, which consists of 82 observations of a variable <math display="inline">y</math> for different <math display="inline">t</math> values. The aim is to model these data set using a 10th-degree polynomial, using both, the QR factorization and SVD, to solve the associated least squares problem. In Section 2 we gave a description of the data and showed numerical results with the normal equations approach. Here we use the QR algorithm with Householder reflections, introduced in Section 3, and the SVD, described in Section 4. | As before we consider the ''Filip'' data set, which consists of 82 observations of a variable <math display="inline">y</math> for different <math display="inline">t</math> values. The aim is to model these data set using a 10th-degree polynomial, using both, the QR factorization and SVD, to solve the associated least squares problem. In Section 2 we gave a description of the data and showed numerical results with the normal equations approach. Here we use the QR algorithm with Householder reflections, introduced in Section 3, and the SVD, described in Section 4. | ||

| − | Table [[#table-2|2]] shows the coefficient values of the polynomial obtained with both algorithms. The coefficients obtained with the QR algorithm are very close to the certified values of ''NIST'' (shown in Table [[#table-1|1]]), while the coefficients obtained with SVD are far from the certified ones, with two or three orders of magnitude apart and different signs for most of them. In fact, the relative difference <math display="inline">\Vert \widehat{\mathbf{c}} - \mathbf{c} | + | Table [[#table-2|2]] shows the coefficient values of the polynomial obtained with both algorithms. The coefficients obtained with the QR algorithm are very close to the certified values of ''NIST'' (shown in Table [[#table-1|1]]), while the coefficients obtained with SVD are far from the certified ones, with two or three orders of magnitude apart and different signs for most of them. In fact, the relative difference <math display="inline">\Vert \widehat{\mathbf{c}} - \mathbf{c}_{nist} \Vert / \Vert \mathbf{c}_{nist} \Vert </math> of the coefficients obtained with the stable QR is insignificant, while the relative difference is as high as <math display="inline">100%</math> when the SVD is employed. However, the polynomial obtained with the SVD shows that the data still fit fairly well to the obtained curve, as shown in Figure [[#img-6|6]]. Again, the main differences between the accurate curve (red line) with respect to the less accurate (blue line) is more evident at the left and right extremes of the interval. |

| − | A better measure for accuracy is the norm of the residual <math display="inline">\Vert \mathbf{b}-A\,\widehat{\mathbf{x}} \Vert </math>, since the algorithms are designed to minimize this quantity. We observe that the residual obtained with the QR algorithm is very close to the certified one (shown in Figure [[#img-2|2]]) and, surprisingly this residual is slightly lower than the certified one, while the residual obtained with the SVD is higher than the certified one but lower than the one obtained with the normal equations. So we conclude that the best method for this particular problem is QR, followed by SVD and the less accurate is obtained with the normal equations. | + | A better measure for accuracy is the norm of the residual <math display="inline">\Vert \mathbf{b}-A\,\widehat{\mathbf{x}} \Vert </math>, since the algorithms are designed to minimize this quantity. We observe that the residual obtained with the QR algorithm is very close to the certified one (shown in Figure [[#img-2|2]]) and, surprisingly this residual is slightly lower than the certified one, while the residual obtained with the SVD is higher than the certified one but lower than the one obtained with the normal equations. So, we conclude that the best method for this particular problem is QR, followed by SVD and the less accurate is obtained with the normal equations. |

{| class="floating_tableSCP wikitable" style="text-align: center; margin: 1em auto;min-width:50%;" | {| class="floating_tableSCP wikitable" style="text-align: center; margin: 1em auto;min-width:50%;" | ||

| − | |+ style="font-size: 75%;" |<span id='table-2'></span> | + | |+ style="font-size: 75%;" |<span id='table-2'></span>Table. 2 Comparison of polynomial coefficients: QR and SVD. |

|- style="border-top: 2px solid;" | |- style="border-top: 2px solid;" | ||

| style="border-left: 2px solid;border-right: 2px solid;" | Polynomial coefficients | | style="border-left: 2px solid;border-right: 2px solid;" | Polynomial coefficients | ||

| Line 848: | Line 837: | ||

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image: | + | |[[Image:Review_960218438971-fig_06.png|450px|Computed polynomial curve with QR and SVD.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | ''' | + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 6:''' Computed polynomial curve with QR and SVD. |

|} | |} | ||

==6 Neural network approach== | ==6 Neural network approach== | ||

| − | Finally, we present a | + | Finally, we present a neural network (NN) framework to address the same fitting problem analyzed in the preceding sections. While NNs have historically been less common than classical methods, they have recently emerged as powerful tools across numerous scientific disciplines. Our goal is to develop a NN that can be used together with the known data for curve fitting. If we have <math display="inline">m</math> observations |

<span id="eq-16"></span> | <span id="eq-16"></span> | ||

| Line 863: | Line 852: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>(t_1,\, | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>(t_1,\,\hat{y}_1),\,(t_2,\,\hat{y}_2), \ldots ,\,(t_m,\,\hat{y}_m)\,, </math> |

|} | |} | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (16) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (16) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | where <math display="inline"> | + | where <math display="inline">\hat{y}_i</math>, <math display="inline">i=1,2, \ldots ,\,m</math>, are measurements of <math display="inline">y(t_i)</math>. The idea is to model <math display="inline">y(t)</math> as a NN of the form: |

<span id="eq-17"></span> | <span id="eq-17"></span> | ||

| Line 876: | Line 865: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>y(t)\approx \widetilde{y}(t,W,b), </math> | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>y(t)\approx \widetilde{y}(t,\mathbf{W},\mathbf{b}), </math> |

|} | |} | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (17) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (17) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | where <math display="inline">W</math> and <math display="inline">b</math> are two sets of parameters of the neural network, which must be determined. This | + | where <math display="inline">\mathbf{W}</math> and <math display="inline">\mathbf{b}</math> are two sets of parameters of the neural network, which must be determined. This NN model consists of an input layer, <math display="inline">L</math> hidden layers, each one containing <math display="inline">N_\ell </math> neurons, and an additional output layer. The received input signal propagates through the network from the input layer to the output layer, through the hidden layers. When the signals arrive in each node, an activation function <math display="inline">\phi :\mathbb{R}\to \mathbb{R}</math> is used to produce the node output <span id='citeF-18'></span><span id='citeF-19'></span><span id='citeF-20'></span>[[#cite-18|[18,19,20]]]. Neural networks with many layers (two or more) are called multi-layer neural networks. |

Example 3: The model corresponding to a neural network with a single hidden layer consisting of five neurons, each activated by the hyperbolic tangent function, and a scalar output obtained through a linear combination of the hidden activations, can be expressed as | Example 3: The model corresponding to a neural network with a single hidden layer consisting of five neurons, each activated by the hyperbolic tangent function, and a scalar output obtained through a linear combination of the hidden activations, can be expressed as | ||

| Line 890: | Line 879: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \widetilde{y}(t,W,b) = W^{2} \phi (W^{1} t + b^{1}) + b^{2}, </math> | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \widetilde{y}(t,\mathbf{W},\mathbf{b}) = W^{2} \phi (W^{1} t + b^{1}) + b^{2}, </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 901: | Line 890: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\widetilde{y}(t,W,b) = \, W^{2}_1 \tanh (W^{1}_{1} t + b^{1}_1) + W^{2}_2 \tanh (W^{1}_{2} t + b^{1}_2) + </math> | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\widetilde{y}(t,\mathbf{W},\mathbf{b}) = \, W^{2}_1 \tanh (W^{1}_{1} t + b^{1}_1) + W^{2}_2 \tanh (W^{1}_{2} t + b^{1}_2) + </math> |

|- | |- | ||

| style="text-align: center;" | <math> W^{2}_3 \tanh (W^{1}_{3} t + b^{1}_3) + W^{2}_4 \tanh (W^{1}_{4} t + b^{1}_4) + </math> | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> W^{2}_3 \tanh (W^{1}_{3} t + b^{1}_3) + W^{2}_4 \tanh (W^{1}_{4} t + b^{1}_4) + </math> | ||

| Line 913: | Line 902: | ||

Remark 2: It is known that any continuous, non-constant function mapping <math display="inline">\mathbb{R}</math> to <math display="inline">\mathbb{R}</math> can be approximated arbitrarily well by a multilayer neural network, see <span id='citeF-21'></span><span id='citeF-22'></span><span id='citeF-23'></span>[[#cite-21|[21,22,23]]]. This result establishes the expressive power of feedforward neural networks. Specifically, it shows that even a network with a single hidden layer, containing a sufficient number of neurons and an appropriate activation function, can approximate any continuous function on compact subsets of <math display="inline">\mathbb{R}</math>. | Remark 2: It is known that any continuous, non-constant function mapping <math display="inline">\mathbb{R}</math> to <math display="inline">\mathbb{R}</math> can be approximated arbitrarily well by a multilayer neural network, see <span id='citeF-21'></span><span id='citeF-22'></span><span id='citeF-23'></span>[[#cite-21|[21,22,23]]]. This result establishes the expressive power of feedforward neural networks. Specifically, it shows that even a network with a single hidden layer, containing a sufficient number of neurons and an appropriate activation function, can approximate any continuous function on compact subsets of <math display="inline">\mathbb{R}</math>. | ||

| − | ===6.1 General | + | ===6.1 General NN architecture=== |

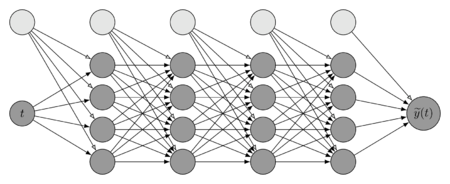

| − | In this work, the | + | In this work, the neural network is described in terms of the input <math display="inline">t \in \mathbb{R}</math>, the output <math display="inline">\widetilde{y} \in \mathbb{R}</math>, and an input-to-output mapping <math display="inline">t \mapsto \widetilde{y}</math>. For any hidden layer <math display="inline">\ell </math>, we consider the pre-activation <math display="inline">T^{\ell } \in \mathbb{R}^{N_\ell }</math> and post-activation <math display="inline">Y^{\ell } \in \mathbb{R}^{N_{\ell{+1}}}</math> vectors as |

<span id="eq-18"></span> | <span id="eq-18"></span> | ||

| Line 954: | Line 943: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | for <math display="inline">k=1,\dots ,N_{\ell }</math>. Here, <math display="inline">W^\ell _{k}</math> and <math display="inline">b^{\ell }</math> are the weights and bias parameters of layer <math display="inline">\ell </math>. Activation functions <math display="inline">\phi </math> must be chosen such that the differential operators can be readily and robustly evaluated using reverse mode automatic differentiation <span id='citeF-25'></span>[[#cite-25|[25]]]. Throughout this work,we have been using relatively simple | + | for <math display="inline">k=1,\dots ,N_{\ell }</math>. Here, <math display="inline">W^\ell _{k}</math> and <math display="inline">b^{\ell }</math> are the weights and bias parameters of layer <math display="inline">\ell </math>. Activation functions <math display="inline">\phi </math> must be chosen such that the differential operators can be readily and robustly evaluated using reverse mode automatic differentiation <span id='citeF-25'></span>[[#cite-25|[25]]]. Throughout this work, we have been using relatively simple feedforward neural networks architectures with hyperbolic tangent and sigmoidal activation functions. Results show that these functions are robust for the proposed formulation. It is important to remark that as more layers and neurons are incorporated into the NN the number of parameters significantly increases. Thus the optimization process becomes less efficient. |

| − | Figure [[#img-7|7]] shows an example of the computational graph representing a | + | Figure [[#img-7|7]] shows an example of the computational graph representing a NN as described in equations [[#eq-18|(18)]]–[[#eq-20|(20)]]. When one node's value is the input of another node, an arrow goes from one to another. In this particular example, we have |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| Line 963: | Line 952: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>layers = \big(N_\ell \big)_{\ell=1}^{L+ | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\hbox{layers} = \big(N_\ell \big)_{\ell=1}^{L+2} = (1,4,4,4,4,1).</math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | That is, the total number of hidden layers is <math display="inline">4</math>. The first entry corresponds to the input layer (<math display="inline">\ell=1</math>) and contains a single neuron. The next four entries correspond to the hidden layers, each one with <math display="inline">N_\ell = 4</math> neurons. Finally, the last layer is the output layer and contains one neuron, corresponding to a single solution value. Bias is also considered (light grey nodes), there is a bias node in each layer, which has a value equal to the unit and is only connected to the nodes of the next layer. Although, the number of nodes for each layer can be different; the same number has been employed in this paper for simplicity. | |

<div id='img-7'></div> | <div id='img-7'></div> | ||

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image: | + | |[[Image:Review_960218438971-fig_07.png|450px|Neural network with 4 hidden layers, one input and one output.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | ''' | + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 7:''' Neural network with 4 hidden layers, one input and one output. |

|} | |} | ||

===6.2 Optimization Algorithm=== | ===6.2 Optimization Algorithm=== | ||

| − | The parameters <math display="inline">W</math> and <math display="inline">b</math> in [[#eq-17|(17)]] are determined using a finite set of training points <math display="inline">\{ t_i, | + | The parameters <math display="inline">\mathbf{W}</math> and <math display="inline">\mathbf{b}</math> in [[#eq-17|(17)]] are determined using a finite set of training points <math display="inline">\{ t_i,\hat{y}_i\} _{i=1}^{m}</math> corresponding to the dataset in [[#eq-16|(16)]]. Here, <math display="inline">m</math> denotes the number of training points, which can be arbitrarily selected. The parameters are estimated by minimizing the mean squared error (MSE) loss |

<span id="eq-21"></span> | <span id="eq-21"></span> | ||

| Line 987: | Line 976: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>E = \frac{1}{N_u}\sum _{i=1}^{N_u} \left|\widetilde{y}(t_i,W,b)- | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>E = \frac{1}{N_u}\sum _{i=1}^{N_u} \left|\widetilde{y}(t_i,\mathbf{W},\mathbf{b})-\hat{y}_i\right|^2, </math> |

|} | |} | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (21) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (21) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | where <math display="inline">E</math> represents the error over the training dataset <math display="inline">\{ t_i, | + | where <math display="inline">E</math> represents the error over the training dataset <math display="inline">\{ t_i,\hat{y}_i\} _{i=1}^{m}</math>. The neural network defined in [[#eq-18|(18)]]–[[#eq-20|(20)]] is trained iteratively, updating the neuron weights by minimizing the discrepancy between the target values <math display="inline">\hat{y}_i</math> and the outputs <math display="inline">\widetilde{y}(t_i,\mathbf{W},\mathbf{b})</math>. |

Formally, the optimization problem can be written as | Formally, the optimization problem can be written as | ||

| Line 1,002: | Line 991: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\min _{[W,b]} E([W,b]), </math> | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\min _{[\mathbf{W},\mathbf{b}]} E([\mathbf{W},\mathbf{b}]), </math> |

|} | |} | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (22) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (22) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | where the vector <math display="inline">[W,b]</math> collects all unknown weights and biases. Several optimization algorithms can be employed to solve the minimization problem [[#eq-21|(21)]] and [[#eq-22|(22)]], and the final performance strongly depends on the residual loss achieved by the chosen method. In this work, the optimization process is performed using gradient-based algorithms, such as Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) or Adam <span id='citeF-26'></span>[[#cite-26|[26]]]. These methods iteratively adjust the network parameters in the direction that minimizes the loss function. Starting from an initial guess <math display="inline">[W^0,b^0]</math>, the algorithm generates a sequence of iterates <math display="inline">[W^1,b^1],\, [W^2,b^2],\, [W^3,b^3], \ldots , </math> converging to a (local) minimizer as the stopping criterion is satisfied. | + | where the vector <math display="inline">[\mathbf{W},\mathbf{b}]</math> collects all unknown weights and biases. Several optimization algorithms can be employed to solve the minimization problem [[#eq-21|(21)]] and [[#eq-22|(22)]], and the final performance strongly depends on the residual loss achieved by the chosen method. In this work, the optimization process is performed using gradient-based algorithms, such as Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) or Adam <span id='citeF-26'></span>[[#cite-26|[26]]]. These methods iteratively adjust the network parameters in the direction that minimizes the loss function. Starting from an initial guess <math display="inline">[\mathbf{W}^0,\mathbf{b}^0]</math>, the algorithm generates a sequence of iterates <math display="inline">[\mathbf{W}^1,\mathbf{b}^1],\, [\mathbf{W}^2,\mathbf{b}^2],\, [\mathbf{W}^3,\mathbf{b}^3], \ldots , </math> converging to a (local) minimizer as the stopping criterion is satisfied. |

The required gradients are computed efficiently using automatic differentiation <span id='citeF-27'></span>[[#cite-27|[27]]], which applies the chain rule to propagate derivatives through the computational graph. In practice, this process is known as backpropagation <span id='citeF-28'></span>[[#cite-28|[28]]]. All computations were carried out in Python using Pytorch <span id='citeF-26'></span>[[#cite-26|[26]]], a widely used and well-documented open-source library for machine learning. | The required gradients are computed efficiently using automatic differentiation <span id='citeF-27'></span>[[#cite-27|[27]]], which applies the chain rule to propagate derivatives through the computational graph. In practice, this process is known as backpropagation <span id='citeF-28'></span>[[#cite-28|[28]]]. All computations were carried out in Python using Pytorch <span id='citeF-26'></span>[[#cite-26|[26]]], a widely used and well-documented open-source library for machine learning. | ||

| Line 1,013: | Line 1,002: | ||

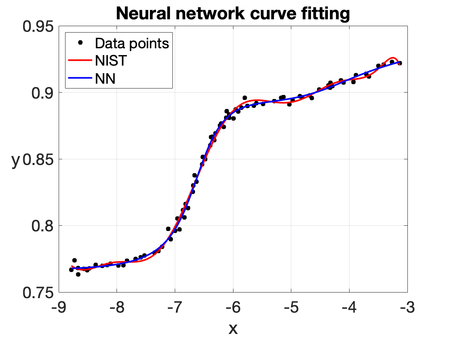

===6.3 Results=== | ===6.3 Results=== | ||

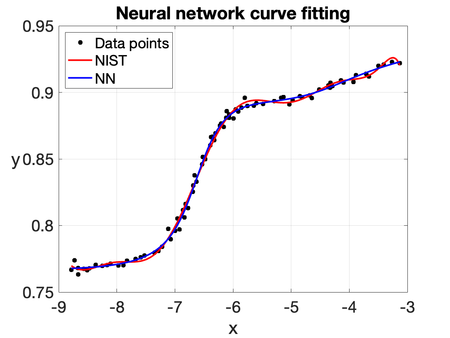

| − | To illustrate the capability of the | + | To illustrate the capability of the NN, we consider the same curve-fitting problem based on the ''Filip'' dataset, which consists of 82 observations of a variable <math display="inline">y</math> at different values of <math display="inline">t</math>. The computed solution is shown in Figures [[#img-8|8]] and [[#img-9|9]]. The predicted values of <math display="inline">y</math> are obtained by training all the parameters of a five-layer neural network: the first layer contains a single neuron, while each hidden layer consists of twenty neurons. The hyperbolic tangent and sigmoidal activation functions are used throughout the network. It is worth noting that the NN solution closely resembles the one obtained using a 10th-degree polynomial fit (''NIST''). Therefore, this example shows its potential for generalization and robustness in more challenging scenarios. |

<div id='img-8'></div> | <div id='img-8'></div> | ||

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image: | + | |[[Image:Review_960218438971-fig_08.png|450px|NN solution with the hyperbolic tangent as activation function.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | ''' | + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 8:''' NN solution with the hyperbolic tangent as activation function. |

|} | |} | ||

<div id='img-9'></div> | <div id='img-9'></div> | ||

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image: | + | |[[Image:Review_960218438971-fig_09.png|450px|NN solution with the sigmoidal as activation function.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | ''' | + | | colspan="1" | '''Figure 9:''' NN solution with the sigmoidal as activation function. |

|} | |} | ||

==7 Conclusions== | ==7 Conclusions== | ||

| − | Fitting a curve to a given set of data is one of the most simple of the so called ''ill-posed'' problems. This is an example of a broad set of problems called least squares problems. This simple problem contains many of the ingredients, both theoretical and computational, of modern challenge and complex problems that are of great importance in computational modelling and applications, specially when computer solutions are obtained using finite precision machines. Commonly there is no ''best computational algorithm'' for general problems, but for a particular problem, like the one considered in this article, we can compare results obtained with different approaches or algorithms. | + | Fitting a curve to a given set of data is one of the most simple of the so called ''ill-posed'' problems. This is an example of a broad set of problems called least squares problems. This simple problem contains many of the ingredients, both theoretical and computational, of modern challenge and complex problems that are of great importance in computational modelling and applications, specially when computer solutions are obtained using finite precision machines. Commonly there is no `''best computational algorithm''' for general problems, but for a particular problem, like the one considered in this article, we can compare results obtained with different approaches or algorithms. |

It is clear that the best fit to a 10th-degree polynomial is obtained with the QR algorithm, as it produces the smallest residual when compared to algorithms based on ''the normal equations'' and SVD. It is noteworthy that each method yields entirely different coefficients for this polynomial. Not only the sign of the coefficients but also the scale of the values differ drastically. These results demonstrate that even simple ill-posed problems must be studied and numerically solved with extreme care, employing stable state-of-the-art algorithms and tools that avoid the accumulation of rounding errors due to the finite arithmetic precision of computers. | It is clear that the best fit to a 10th-degree polynomial is obtained with the QR algorithm, as it produces the smallest residual when compared to algorithms based on ''the normal equations'' and SVD. It is noteworthy that each method yields entirely different coefficients for this polynomial. Not only the sign of the coefficients but also the scale of the values differ drastically. These results demonstrate that even simple ill-posed problems must be studied and numerically solved with extreme care, employing stable state-of-the-art algorithms and tools that avoid the accumulation of rounding errors due to the finite arithmetic precision of computers. | ||

| − | Concerning the | + | Concerning the neural network approach, we obtained qualitatively excellent numerical results. The resulting fitted curve is smooth and provides an accurate representation of the data, and it appears to offer a slightly improved approximation when compared to the QR-based fit, while maintaining sufficient flexibility to capture the overall behavior. These results suggest that the multi-layer neural networks constitute an effective and robust framework for curve fitting. Is the NN approach better than the QR algorithm for curve fitting? Again, this general question depends of what you are looking for. But if you are able to construct with NN a 10th-degree polynomial that fits the given experimental data, then you are able to answer this particular question. A diligent reader may put their hands on the problem in order to give an answer. |

'''Acknowledgements.''' We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Department of Mathematics at Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana–Iztapalapa for their valuable support of this research work. The authors also gratefully acknowledge partial support from the Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (Secihti) through the Investigadores e Investigadoras por México program and the Ciencia de Frontera Project No. CF-2023-I-2639. | '''Acknowledgements.''' We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Department of Mathematics at Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana–Iztapalapa for their valuable support of this research work. The authors also gratefully acknowledge partial support from the Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (Secihti) through the Investigadores e Investigadoras por México program and the Ciencia de Frontera Project No. CF-2023-I-2639. | ||

| Line 1,067: | Line 1,056: | ||

<div id="cite-9"></div> | <div id="cite-9"></div> | ||

| − | '''[[#citeF-9|[9]]]''' | + | '''[[#citeF-9|[9]]]''' Lloyd N. Trefethen and David Bau III. (1997) "Numerical Linear Algebra". SIAM |

<div id="cite-10"></div> | <div id="cite-10"></div> | ||

| − | '''[[#citeF-10|[10]]]''' | + | '''[[#citeF-10|[10]]]''' "Statistical Reference Datasets: Filip Data" https://www.itl.nist.gov/div898/strd/lls/data/Filip.shtml |

<div id="cite-11"></div> | <div id="cite-11"></div> | ||

| − | '''[[#citeF-11|[11]]]''' | + | '''[[#citeF-11|[11]]]''' Cleve B. Moler. (2004) "Numerical Computing with MATLAB". SIAM |

<div id="cite-12"></div> | <div id="cite-12"></div> | ||

| Line 1,103: | Line 1,092: | ||

<div id="cite-21"></div> | <div id="cite-21"></div> | ||

| − | '''[[#citeF-21|[21]]]''' | + | '''[[#citeF-21|[21]]]''' G. Cybenko. (1989) "Approximation by superpositions of a sigmoidal function", Volume 2. Mathematics of Control, Signals and Systems 4 303–314 |

<div id="cite-22"></div> | <div id="cite-22"></div> | ||

| − | '''[[#citeF-22|[22]]]''' | + | '''[[#citeF-22|[22]]]''' K. Hornik and M. Stinchcombe and H. White. (1989) "Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators", Volume 2. Neural Networks 5 359–366 |