| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

==1 Introduction== | ==1 Introduction== | ||

| − | The modified Helmholtz equation appears in a common physical model | + | The modified Helmholtz equation appears in a common physical model, and its numerical solution remains an active line of research. See the discussion in Yaman & zdemir <span id='citeF-1'></span>[[#cite-1|[1]]] and the recent Yaman et al <span id='citeF-2'></span>[[#cite-2|[2]]]. In the former, an integral equation method is proposed for the numerical solution. In this work, a Galerkin approach is preferred for the numerical solution of perturbations of the modified Helmholtz equation. |

| − | The classical Galerkin approach is the | + | The classical Galerkin approach is the continuous Galerkin, Finite Element Method (FEM). A recent and attractive alternative is the Discontinuous Galerkin (DG) method. Unlike FEM, it is locally conservative and <math display="inline">H^p</math>-adaptative. On the downside, the application of the Discontinuous Galerkin Method to elliptic problems usually leads to underdetermined linear systems, and penalization or suitable constraints are required. Moreover, Discontinuous Galerkin methods are more expensive because of the need for numerical fluxes at the edges of the mesh elements, thus yielding more coupled unknowns than FEM. See Riviere <span id='citeF-3'></span>[[#cite-3|[3]]] and Di Pietro & Ern <span id='citeF-4'></span>[[#cite-4|[4]]] for a thorough exposition. |

| − | These shortcomings of the DG method can be addressed in part by its descendant, the Hybrid Discontinuous Galerkin Method (HDG), Bui Tahn <span id='citeF-5'></span>[[#cite-5|[5]]]. The numerical flux is ''hybridized'', introducing unknowns on the edges of the mesh, | + | These shortcomings of the DG method can be addressed in part by its descendant, the Hybrid Discontinuous Galerkin Method (HDG), Bui-Tahn <span id='citeF-5'></span>[[#cite-5|[5]]]. The numerical flux is ''hybridized'', introducing additional unknowns on the edges of the mesh, which reduces the coupling between elements. The global solution is then obtained by solving small and independent linear systems on each element. |

For the elliptic problem under study, we use a simple, physically motivated hybrid numerical flux that yields a well-posed linear system. This is guaranteed by the dominant reaction term in the modified Helmholtz equation. | For the elliptic problem under study, we use a simple, physically motivated hybrid numerical flux that yields a well-posed linear system. This is guaranteed by the dominant reaction term in the modified Helmholtz equation. | ||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

The outline is as follows. In Section 2, we follow the HDG methodology and introduce a first-order system associated with the perturbed modified Helmholtz equations. Then, we delve into the discretization of the first-order system and show that the resulting finite-dimensional problem is well posed. Numerical tests are presented in Section 3. First, we illustrate its performance as a Poisson solver in a preliminary comparison with a leading method in the literature. Accurate approximations are also shown for some benchmark Helmholtz problems in Coastal Ocean Modeling. In all examples, we highlight approximations on coarse meshes. We close our exposition with conclusions and future work. | The outline is as follows. In Section 2, we follow the HDG methodology and introduce a first-order system associated with the perturbed modified Helmholtz equations. Then, we delve into the discretization of the first-order system and show that the resulting finite-dimensional problem is well posed. Numerical tests are presented in Section 3. First, we illustrate its performance as a Poisson solver in a preliminary comparison with a leading method in the literature. Accurate approximations are also shown for some benchmark Helmholtz problems in Coastal Ocean Modeling. In all examples, we highlight approximations on coarse meshes. We close our exposition with conclusions and future work. | ||

| − | ==2 | + | ==2 Numerical solution of the modified Helmholtz equation== |

| + | |||

| + | In what follows, we build on the theoretical and numerical aspects of the finite element method (FEM) as presented, for instance, in the text <span id='citeF-6'></span>[[#cite-6|[6]]]. | ||

===2.1 A first order system for perturbations of the modified Helmholtz equation=== | ===2.1 A first order system for perturbations of the modified Helmholtz equation=== | ||

| Line 36: | Line 38: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\lambda \vert \xi \vert ^2\leq \xi ^T\mathbf{D}(x)\xi \leq \Lambda \vert \xi \vert ^2,\quad \xi \in \mathbb{R}^d </math> | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>\lambda \vert \xi \vert ^2\leq \xi ^T\mathbf{D}(x)\xi \leq \Lambda \vert \xi \vert ^2,\quad \xi \in \mathbb{R}^d. </math> |

|} | |} | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (2) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (2) | ||

| Line 65: | Line 67: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \mathcal{K}=\left(\begin{matrix} \mathbf{D}^{-1}&\mathbf{0}\\ -\mathbf{v}^T\mathbf{D}^{-1}&c \end{matrix}\right) | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \mathcal{K}=\left(\begin{matrix} \mathbf{D}^{-1}&\mathbf{0}\\ -\mathbf{v}^T\mathbf{D}^{-1}&c \end{matrix}\right), </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 83: | Line 85: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \mathbf{u}:=\left(\begin{matrix} \mathbf{z}\\ u \end{matrix}\right),\quad \mathbf{f}:=\left(\begin{matrix} \mathbf{0}\\ | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \mathbf{u}:=\left(\begin{matrix} \mathbf{z}\\ u \end{matrix}\right),\quad \mathbf{f}:=\left(\begin{matrix} \mathbf{0}\\ b \end{matrix}\right). </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 104: | Line 106: | ||

Here we introduce the essentials of HDG, for full details see Bui-Thanh <span id='citeF-5'></span>[[#cite-5|[5]]]. | Here we introduce the essentials of HDG, for full details see Bui-Thanh <span id='citeF-5'></span>[[#cite-5|[5]]]. | ||

| − | For any matrix <math display="inline">\mathbf{M}</math>, we denote by <math display="inline">\mathbf{M}_i,\, \mathbf{M}^j</math> its row <math display="inline">i</math> | + | For any matrix <math display="inline">\mathbf{M}</math>, we denote by <math display="inline">\mathbf{M}_i,\, \mathbf{M}^j</math> its row <math display="inline">i</math> and column <math display="inline">j</math> respectively. |

Let us define | Let us define | ||

| Line 139: | Line 141: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | We can write | + | We can write system ([[#eq-3|3]]) in the form |

<span id="eq-4"></span> | <span id="eq-4"></span> | ||

| Line 154: | Line 156: | ||

Assume we have a valid element partition of the domain <math display="inline">\Omega </math>. In DG, functions are approximated locally in each element by polynomials, then coupled with others in adjacent elements by means of a numerical flux. The basic process is as follows. | Assume we have a valid element partition of the domain <math display="inline">\Omega </math>. In DG, functions are approximated locally in each element by polynomials, then coupled with others in adjacent elements by means of a numerical flux. The basic process is as follows. | ||

| − | Let <math display="inline">\tau </math> be an element in the partition. Compute the <math display="inline">(L^2)^m</math> inner product on <math display="inline">\tau </math> of each side of ([[#eq-4|4]]) with a | + | Let <math display="inline">\tau </math> be an element in the partition. Compute the <math display="inline">(L^2)^m</math> inner product on <math display="inline">\tau </math> of each side of ([[#eq-4|4]]) with a test function <math display="inline">\mathbf{v}</math>, to obtain |

<span id="eq-5"></span> | <span id="eq-5"></span> | ||

| Line 167: | Line 169: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | Denoting the inner product in th eboundary of <math display="inline">\tau </math> by <math display="inline">\langle \cdot ,\cdot \rangle _{\partial \tau }</math> we obtain after integrating by parts, | |

<span id="eq-6"></span> | <span id="eq-6"></span> | ||

| Line 175: | Line 177: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>-(F(\mathbf{u}),\nabla \mathbf{v})_\tau{+\langle}F(\mathbf{u})\cdot \mathbf{n},\mathbf{v}\rangle _{\partial \tau } +(B\mathbf{u},\mathbf{v})_\tau =(\mathbf{f},\mathbf{v})_\tau | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>-(F(\mathbf{u}),\nabla \mathbf{v})_\tau{+\langle}F(\mathbf{u})\cdot \mathbf{n},\mathbf{v}\rangle _{\partial \tau } +(B\mathbf{u},\mathbf{v})_\tau =(\mathbf{f},\mathbf{v})_\tau{.} </math> |

|} | |} | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (6) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (6) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Continuity is not enforced at the boundary of adjacent elements. Therefore, the boundary term <math display="inline">F(\mathbf{u})</math> is replaced with a boundary numerical flux <math display="inline">F^*(\mathbf{u}^*)</math> where <math display="inline">\mathbf{u}^*\equiv \mathbf{u}^*(\mathbf{u}^-,\mathbf{u}^+)</math> solves a Riemann problem with Cauchy data <math display="inline">\mathbf{u}^-,\, \mathbf{u}^+</math>. As | + | Continuity is not enforced at the boundary of adjacent elements. Therefore, the boundary term <math display="inline">F(\mathbf{u})</math> is replaced with a boundary numerical flux <math display="inline">F^*(\mathbf{u}^*)</math> where <math display="inline">\mathbf{u}^*\equiv \mathbf{u}^*(\mathbf{u}^-,\mathbf{u}^+)</math> solves a Riemann problem with Cauchy data <math display="inline">\mathbf{u}^-,\, \mathbf{u}^+</math>. As is standard, the – superscript denotes limits from the interior of <math display="inline">e</math>, and the <math display="inline">+</math> superscript, limits from the exterior. In this context, element <math display="inline">\tau </math> is denoted by <math display="inline">\tau ^-</math> and the outer normal <math display="inline">\mathbf{n}</math> by <math display="inline">\mathbf{n}^-</math>. |

| − | To hybridize the flux, and break the coupling, <math display="inline">\mathbf{u}^*</math> is regarded as an extra unknown to be solved on the skeleton of the mesh. Renaming <math display="inline">\mathbf{u}^*</math> as <math display="inline">\hat{\mathbf{u}}</math> and <math display="inline">F^*</math> as <math display="inline">\hat{F}</math>, the problem is to propose a suitable hybrid numerical flux <math display="inline">\hat{\mathbf{F}}(\mathbf{u})</math>. | + | To hybridize the flux, and break the coupling, <math display="inline">\mathbf{u}^*</math> is regarded as an extra unknown to be solved on the skeleton (the set of element edges <math display="inline">\mathcal{F}</math>) of the mesh. Renaming <math display="inline">\mathbf{u}^*</math> as <math display="inline">\hat{\mathbf{u}}</math> and <math display="inline">F^*</math> as <math display="inline">\hat{F}</math>, the problem is to propose a suitable hybrid numerical flux <math display="inline">\hat{\mathbf{F}}(\mathbf{u})</math>. |

Let us apply this scheme to equation ([[#eq-1|1]]) under the following condition | Let us apply this scheme to equation ([[#eq-1|1]]) under the following condition | ||

| Line 210: | Line 212: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Notice dependence only in the unknown <math display="inline">\hat{u}</math>. | + | Notice the dependence only in the unknown <math display="inline">\hat{u}</math>. |

For each element <math display="inline">\tau </math>, the DG local unknown <math display="inline">\mathbf{u}</math> and the extra ''trace'' unknown <math display="inline">\hat{u}</math> need to satisfy | For each element <math display="inline">\tau </math>, the DG local unknown <math display="inline">\mathbf{u}</math> and the extra ''trace'' unknown <math display="inline">\hat{u}</math> need to satisfy | ||

| Line 225: | Line 227: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | This is complemented by a weak jump condition in the skeleton | + | This is complemented by a weak jump condition in the skeleton. Namely, for each edge <math display="inline">e</math> |

<span id="eq-10"></span> | <span id="eq-10"></span> | ||

| Line 233: | Line 235: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>(\lbrack\lbrack \mathbf{z}\cdot \mathbf{n}+u-\hat{u}\rbrack\rbrack , w)_e =0 | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>(\lbrack\lbrack \mathbf{z}\cdot \mathbf{n}+u-\hat{u}\rbrack\rbrack , w)_e =0, </math> |

|} | |} | ||

| style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (10) | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;" | (10) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | where <math display="inline">\mathbf{v}</math> in ([[#eq-9|9]]), <math display="inline">w</math> in ([[#eq-10|10]]) are polynomial test functions defined on elements <math display="inline">\tau </math> and edges <math display="inline">e</math> respectively. | |

Here, <math display="inline">\lbrack\lbrack \cdot \rbrack\rbrack </math> is the jump operator, | Here, <math display="inline">\lbrack\lbrack \cdot \rbrack\rbrack </math> is the jump operator, | ||

| Line 287: | Line 289: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Let <math display="inline">\mathbf{w}=\mathbf{z}, w=u</math>, and add equations ([[#eq-11|11]]) | + | Let <math display="inline">\mathbf{w}=\mathbf{z}, w=u</math>, and add equations ([[#eq-11|11]]) and ([[#eq-13|13]]) to obtain |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| Line 348: | Line 350: | ||

Since <math display="inline">\mathbf{w}</math> is arbitrary, <math display="inline">\nabla u=0</math>, and consequently <math display="inline">u\equiv 0</math> in each element <math display="inline">u</math>. | Since <math display="inline">\mathbf{w}</math> is arbitrary, <math display="inline">\nabla u=0</math>, and consequently <math display="inline">u\equiv 0</math> in each element <math display="inline">u</math>. | ||

| − | We conclude that <math display="inline">u=0, \mathbf{z}=\mathbf{0}</math> in <math display="inline">\Omega </math>. <math display="inline">\blacksquare </math> | + | We conclude that <math display="inline">u=0, \mathbf{z}=\mathbf{0}</math> in <math display="inline">\Omega </math>. <math display="inline">\blacksquare </math> |

'''Remark. ''' Notice that the result is valid for Poisson problems, <math display="inline">c=0</math>, <math display="inline">\mathbf{v}=\mathbf{0}</math>. | '''Remark. ''' Notice that the result is valid for Poisson problems, <math display="inline">c=0</math>, <math display="inline">\mathbf{v}=\mathbf{0}</math>. | ||

| Line 354: | Line 356: | ||

==3 Numerical results== | ==3 Numerical results== | ||

| − | Here we | + | Here, we illustrate some numerical results on a variety of problems, where the perturbed modified Helmholtz equation HDG solver serves as the computational engine. |

| − | + | The full code of the numerical implementation is available on GitHub: | |

| − | + | https://github.com/Danalie/Hibrid-Discontinuos-Galerkin-DG2 | |

| − | To report the | + | We will test benchmark problems in rectangular geometries and regular meshes for simplicity. |

| + | |||

| + | We use the classical element functions on the reference segment <math display="inline">[-1,1]</math> for 1D applications. We denote by <math display="inline">HDG_p</math> a <math display="inline"> p</math>-order bilinear approximation. In 2D, <math display="inline">HDG_2, HDG_4</math> refer to basis functions on the reference square <math display="inline">[-1,1]\times [-1,1]</math>, as products of first-order and second-order one-dimensional 1D basis functions, respectively. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To report the accuracy of the approximation, we use the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). Sometimes, we normalize by the corresponding norm of the exact solution to obtain the Normalized Root Mean Square Error (NRMSE). | ||

===3.1 Poisson problems=== | ===3.1 Poisson problems=== | ||

| Line 384: | Line 390: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>-\Delta p=0, | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>-\Delta p=0, (x,y) \in \Omega ,</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> p=1+x+y+xy, | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> p(x,y)=1+x+y+xy, (x,y)\in \partial \Omega{.} </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | The exact solution is <math display="inline">p(x, y)=1+x+y+xy</math>. The numerical solution using <math display="inline">HDG_2</math> on a <math display="inline">10\times 10</math> grid yields <math display="inline">RMSE | + | The exact solution is <math display="inline">p(x, y)=1+x+y+xy</math>. The numerical solution using <math display="inline">HDG_2</math> on a <math display="inline">10\times 10</math> grid yields <math display="inline">RMSE=0</math> to machine precision; no further refinement is necessary. |

The DG method is <math display="inline">H^p</math>-adaptative. Local high order is straightforward, and accurate approximations are possible on coarse meshes. For instance, we use <math display="inline">HDG_4</math> for the Dirichlet problem | The DG method is <math display="inline">H^p</math>-adaptative. Local high order is straightforward, and accurate approximations are possible on coarse meshes. For instance, we use <math display="inline">HDG_4</math> for the Dirichlet problem | ||

| Line 399: | Line 405: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>-\Delta p=-6, \quad | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math>-\Delta p=-6, \quad (x,y)\in \Omega=(0, 1)\times (0, 1),</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> p=1+x^2+2y^2, \quad | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> p(x,y)=1+x^2+2y^2, \quad (x,y)\in \partial \Omega{.} </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | On a <math display="inline">10\times 10</math> grid the <math display="inline">RMSE | + | On a <math display="inline">10\times 10</math> grid the <math display="inline">RMSE</math> is again zero to machine precision. |

| − | A preliminary comparison with the method in <span id='citeF- | + | A preliminary comparison with the method in <span id='citeF-7'></span>[[#cite-7|[7]]]. The latter relies on an internal-penalty numerical flux requiring a penalty parameter chosen heuristically, see (34) therein. Accuracy is shown in an exhaustive list of test problems. The simplest of such is the Dirichlet problem |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%; text-align: left;" | ||

| Line 424: | Line 430: | ||

{| class="floating_tableSCP wikitable" style="text-align: center; margin: 1em auto;min-width:50%;" | {| class="floating_tableSCP wikitable" style="text-align: center; margin: 1em auto;min-width:50%;" | ||

| − | |+ style="font-size: 75%;" |<span id='table-1'></span> | + | |+ style="font-size: 75%;" |<span id='table-1'></span>Tabla. 1 Convergence of the two-dimensional Poisson problem using the Root means square error (RMSE). <math>\mathcal{P}</math> is the order of approximation |

|- style="border-top: 2px solid;" | |- style="border-top: 2px solid;" | ||

| style="border-left: 2px solid;border-right: 2px solid;" | '''Elements by dimension''' | | style="border-left: 2px solid;border-right: 2px solid;" | '''Elements by dimension''' | ||

| Line 470: | Line 476: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | By inspection of Figure 7 in <span id='citeF-7'></span>[[#cite-7|[7]]], it is apparent that our results compare favorably. A full comparison is to be carried out. | |

===3.2 Helmholtz equation=== | ===3.2 Helmholtz equation=== | ||

| − | We consider two benchmark problems in Coastal Ocean Modeling (COM) that lead to Helmholtz equations. A comparison is made with the Finite Volume (FVCOM) as presented in Chen et al <span id='citeF- | + | We consider two benchmark problems in Coastal Ocean Modeling (COM) that lead to Helmholtz equations. A comparison is made with the Finite Volume (FVCOM) as presented in Chen et al <span id='citeF-8'></span>[[#cite-8|[8]]]. Therein, FVCOM is applied for the modeling of tidal simulation in a semienclosed basin with tidal forcing at the open boundary under near-resonance conditions. |

Here we apply HDG to illustrate the accurate simulation of the troublesome near resonance case. We remark that for the Helmholtz equation, condition ([[#eq-7|7]]) is not valid. Nevertheless, the numerical results are highly satisfactory. | Here we apply HDG to illustrate the accurate simulation of the troublesome near resonance case. We remark that for the Helmholtz equation, condition ([[#eq-7|7]]) is not valid. Nevertheless, the numerical results are highly satisfactory. | ||

| Line 480: | Line 486: | ||

====3.2.1 A Rectangular Channel==== | ====3.2.1 A Rectangular Channel==== | ||

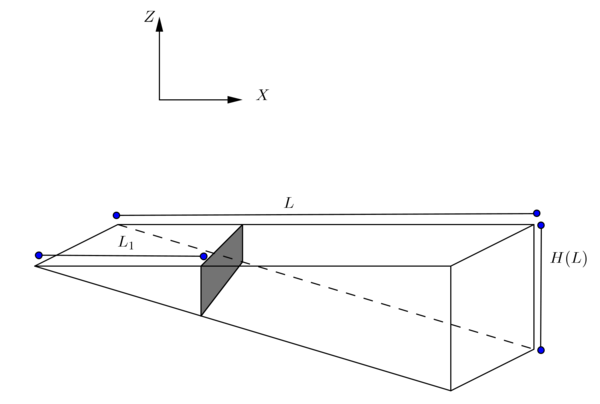

| − | Consider a fluid layer of uniform density that propagates along a channel aligned with the <math display="inline">x-</math>direction. More precisely, a semienclosed narrow channel with length <math display="inline">L</math> and variable depth <math display="inline">H(x)</math> and a closed boundary at <math display="inline">x=L_1</math> and an | + | Consider a fluid layer of uniform density that propagates along a channel aligned with the <math display="inline">x-</math>direction. More precisely, a semienclosed narrow channel with length <math display="inline">L</math> and variable depth <math display="inline">H(x)</math> and a closed boundary at <math display="inline">x=L_1</math> and an open boundary at <math display="inline">x=L</math>. |

Neglecting Coriolis force and advection of momentum, the governing equations modeling tidal waves propagation in the semienclosed channel (see Figure [[#img-1|1]]) are given as | Neglecting Coriolis force and advection of momentum, the governing equations modeling tidal waves propagation in the semienclosed channel (see Figure [[#img-1|1]]) are given as | ||

| Line 489: | Line 495: | ||

{| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | {| style="text-align: left; margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \frac{\partial u}{\partial t}+g\frac{\partial \zeta }{\partial x}=0;\quad \frac{\partial \zeta }{\partial t}+g\frac{\partial uH}{\partial x}=0; \quad (x,t)\in ( | + | | style="text-align: center;" | <math> \frac{\partial u}{\partial t}+g\frac{\partial \zeta }{\partial x}=0;\quad \frac{\partial \zeta }{\partial t}+g\frac{\partial uH}{\partial x}=0; \quad (x,t)\in (L_1,L)\times (0,T). </math> |

|} | |} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Here, <math display="inline">H(x)</math> is the total water depth, <math display="inline">g</math> is acceleration due to gravity, <math display="inline">u</math> is speed in the <math display="inline">x-</math>direction, and <math display="inline">\zeta </math> is sea-level elevation . | + | Here, <math display="inline">H(x)</math> is the total water depth, <math display="inline">g</math> is acceleration due to gravity, <math display="inline">u</math> is speed in the <math display="inline">x-</math>direction, and <math display="inline">\zeta </math> is sea-level elevation. |

<div id='img-1'></div> | <div id='img-1'></div> | ||

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image: | + | |[[Image:Review_259681306732-canal_1d.png|600px|''Configuration of the semienclosed channel.'']] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | ''' | + | | colspan="1" | '''Figura 1:''' ''Configuration of the semienclosed channel.'' |

|} | |} | ||

Assuming harmonic solutions, | Assuming harmonic solutions, | ||

| Line 613: | Line 619: | ||

{| class="floating_tableSCP wikitable" style="text-align: center; margin: 1em auto;min-width:50%;" | {| class="floating_tableSCP wikitable" style="text-align: center; margin: 1em auto;min-width:50%;" | ||

| − | |+ style="font-size: 75%;" |<span id='table-2'></span> | + | |+ style="font-size: 75%;" |<span id='table-2'></span>Tabla. 2 Relative root mean square error for <math>\mbox{HDG}_2</math> and FV. |

|- style="border-top: 2px solid;" | |- style="border-top: 2px solid;" | ||

| style="border-left: 2px solid;border-right: 2px solid;" | Elements | | style="border-left: 2px solid;border-right: 2px solid;" | Elements | ||

| Line 658: | Line 664: | ||

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

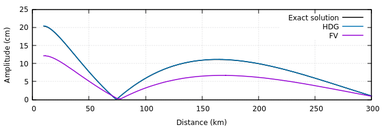

| − | |[[Image: | + | |[[Image:Review_259681306732-canalHDG_2.png|384px|Solution for the rectangular channel near resonance case, with HDG nodal with polynomials of degree 2 and 80 elements.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | ''' | + | | colspan="1" | '''Figura 2:''' Solution for the rectangular channel near resonance case, with HDG nodal with polynomials of degree 2 and 80 elements. |

|} | |} | ||

| − | '''Remark. '''As pointed out in Chen et al <span id='citeF- | + | '''Remark. '''As pointed out in Chen et al <span id='citeF-8'></span>[[#cite-8|[8]]], regardless of the numerical method, a proper selection of horizontal resolution recover accurately this tidal resonance problem. We argue that the accuracy attained by HDG in coarse meshes yields a better choice. |

====3.2.2 A Sector Channel==== | ====3.2.2 A Sector Channel==== | ||

| Line 674: | Line 680: | ||

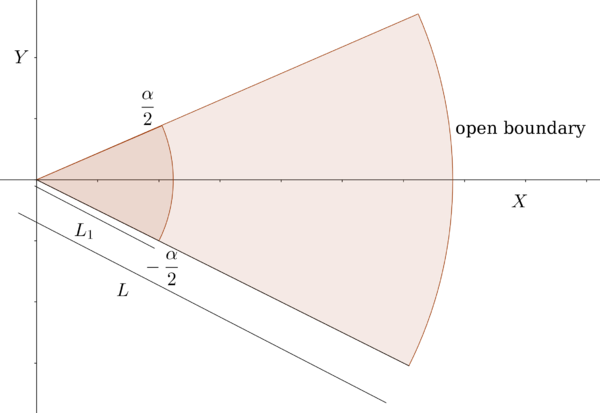

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image: | + | |[[Image:Review_259681306732-canal_2d.png|600px|Semienclosed sector channel in the polar region L₁≤r≤L, -\fracα2≤θ≤\fracα2. The sector is open at r=L and closed elsewhere.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="1" | ''' | + | | colspan="1" | '''Figura 3:''' Semienclosed sector channel in the polar region <math>L_1\leq r\leq L</math>, <math>-\frac{\alpha }{2}\leq \theta \leq \frac{\alpha }{2}</math>. The sector is open at <math>r=L</math> and closed elsewhere. |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 817: | Line 823: | ||

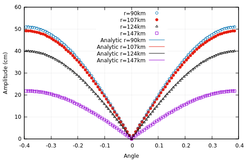

{| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | {| class="floating_imageSCP" style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; width: 100%;max-width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image: | + | |[[Image:Review_259681306732-cortes_r.png|248px|]] |

| − | |[[Image: | + | |[[Image:Review_259681306732-cortes_theta.png|273px|Comparison between the analytic solution to the sector problem with the HDG₄ solution using 30×50 elements. a) Solution for some r values, b) Solution for some θ values.]] |

|- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | |- style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="2" | ''' | + | | colspan="2" | '''Figura 4:''' Comparison between the analytic solution to the sector problem with the <math>\mbox{HDG}_4</math> solution using <math>30\times 50</math> elements. a) Solution for some <math>r</math> values, b) Solution for some <math>\theta </math> values. |

|} | |} | ||

{| class="floating_tableSCP wikitable" style="text-align: center; margin: 1em auto;min-width:50%;" | {| class="floating_tableSCP wikitable" style="text-align: center; margin: 1em auto;min-width:50%;" | ||

| − | |+ style="font-size: 75%;" |<span id='table-3'></span> | + | |+ style="font-size: 75%;" |<span id='table-3'></span>Tabla. 3 Relative root mean square error for <math>\mbox{HDG}_4</math> and FV. |

|- style="border-top: 2px solid;" | |- style="border-top: 2px solid;" | ||

| style="border-left: 2px solid;border-right: 2px solid;" | Elements | | style="border-left: 2px solid;border-right: 2px solid;" | Elements | ||

| Line 850: | Line 856: | ||

'''Remark. '''Noteworthy, the <math display="inline">10\times 10</math> <math display="inline">\mbox{HDG}_4</math> solution is of grater quality that the <math display="inline">40\times 40</math> FV solution. In regards to execution time, the former is attained in half a second on a personal laptop. A solution of the same quality would require in the order of minutes with the Finite Volume Method in a much finer mesh. | '''Remark. '''Noteworthy, the <math display="inline">10\times 10</math> <math display="inline">\mbox{HDG}_4</math> solution is of grater quality that the <math display="inline">40\times 40</math> FV solution. In regards to execution time, the former is attained in half a second on a personal laptop. A solution of the same quality would require in the order of minutes with the Finite Volume Method in a much finer mesh. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==4 Conclussions== | ==4 Conclussions== | ||

| − | We have introduced a first-order system formulation for a regularly perturbed Modified Helmholtz equation. A discretization is derived by means of the Hybrid Discontinuous Galerkin method with an ad-hoc numerical flux. The | + | We have introduced a first-order system formulation for a regularly perturbed Modified Helmholtz equation. A discretization is derived by means of the Hybrid Discontinuous Galerkin method with an ad-hoc numerical flux. The well-posedness of the finite-dimensional HDG discrete linear system follows from a dominant reaction condition. |

The preliminary comparison with a leading Poisson solver shows promise as a competitive alternative. Research on this is ongoing. | The preliminary comparison with a leading Poisson solver shows promise as a competitive alternative. Research on this is ongoing. | ||

| − | The proposed HDG discrete method is also applied to | + | The proposed HDG discrete method is also applied to Helmholtz's problems arising from coastal ccean modeling. It outperforms the Finite Volume method commonly used in this setting. |

The application to irregular regions with more general meshes is more elaborate but straightforward. Also, a parallel computing implementation is desired. Both tasks are left for future work. | The application to irregular regions with more general meshes is more elaborate but straightforward. Also, a parallel computing implementation is desired. Both tasks are left for future work. | ||

| Line 978: | Line 885: | ||

<div id="cite-6"></div> | <div id="cite-6"></div> | ||

| − | '''[[#citeF-6|[6]]]''' | + | '''[[#citeF-6|[6]]]''' Gockenbach, Mark S. (2006) "Understanding and implementing the finite element method". SIAM |

<div id="cite-7"></div> | <div id="cite-7"></div> | ||

| − | '''[[#citeF-7|[7]]]''' Chen, Changsheng and Huang, Haosheng and Beardsley, Robert C and Liu, Hedong and Xu, Qichun and Cowles, Geoffrey. (2007) "A finite volume numerical approach for coastal ocean circulation studies: Comparisons with finite difference models", Volume 112. Wiley Online Library. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans C3 | + | '''[[#citeF-7|[7]]]''' Fischer, Nils L and Pfeiffer, Harald P. (2022) "Unified discontinuous Galerkin scheme for a large class of elliptic equations", Volume 105. APS. Physical Review D 2 024034 |

| + | |||

| + | <div id="cite-8"></div> | ||

| + | '''[[#citeF-8|[8]]]''' Chen, Changsheng and Huang, Haosheng and Beardsley, Robert C and Liu, Hedong and Xu, Qichun and Cowles, Geoffrey. (2007) "A finite volume numerical approach for coastal ocean circulation studies: Comparisons with finite difference models", Volume 112. Wiley Online Library. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans C3 | ||

Latest revision as of 21:13, 27 December 2025

1 Introduction

The modified Helmholtz equation appears in a common physical model, and its numerical solution remains an active line of research. See the discussion in Yaman & zdemir [1] and the recent Yaman et al [2]. In the former, an integral equation method is proposed for the numerical solution. In this work, a Galerkin approach is preferred for the numerical solution of perturbations of the modified Helmholtz equation.

The classical Galerkin approach is the continuous Galerkin, Finite Element Method (FEM). A recent and attractive alternative is the Discontinuous Galerkin (DG) method. Unlike FEM, it is locally conservative and -adaptative. On the downside, the application of the Discontinuous Galerkin Method to elliptic problems usually leads to underdetermined linear systems, and penalization or suitable constraints are required. Moreover, Discontinuous Galerkin methods are more expensive because of the need for numerical fluxes at the edges of the mesh elements, thus yielding more coupled unknowns than FEM. See Riviere [3] and Di Pietro & Ern [4] for a thorough exposition.

These shortcomings of the DG method can be addressed in part by its descendant, the Hybrid Discontinuous Galerkin Method (HDG), Bui-Tahn [5]. The numerical flux is hybridized, introducing additional unknowns on the edges of the mesh, which reduces the coupling between elements. The global solution is then obtained by solving small and independent linear systems on each element.

For the elliptic problem under study, we use a simple, physically motivated hybrid numerical flux that yields a well-posed linear system. This is guaranteed by the dominant reaction term in the modified Helmholtz equation.

The outline is as follows. In Section 2, we follow the HDG methodology and introduce a first-order system associated with the perturbed modified Helmholtz equations. Then, we delve into the discretization of the first-order system and show that the resulting finite-dimensional problem is well posed. Numerical tests are presented in Section 3. First, we illustrate its performance as a Poisson solver in a preliminary comparison with a leading method in the literature. Accurate approximations are also shown for some benchmark Helmholtz problems in Coastal Ocean Modeling. In all examples, we highlight approximations on coarse meshes. We close our exposition with conclusions and future work.

2 Numerical solution of the modified Helmholtz equation

In what follows, we build on the theoretical and numerical aspects of the finite element method (FEM) as presented, for instance, in the text [6].

2.1 A first order system for perturbations of the modified Helmholtz equation

For a bounded Lipschitz domain in , let us consider the diffusion-advection-reaction equation for the unknown function ,

|

|

(1) |

The diffusion term is uniformly elliptic, that is is symmetric and there exist constants such that for almost all

|

|

(2) |

Also, assume that , and .

For and , equation (1) is known as the modified Helmholtz equation. To construct a Discontinuous Galerkin approximation, a first step is to construct a hyperbolic-like first-order system. A small advection term is allowed; the smallness condition is made precise below.

Define the new variable (flux) . Since the matrix is invertible, , we obtain the following system

|

|

Let , and be the th canonical vector. Define

|

|

|

|

|

|

The system becomes

|

|

(3) |

2.2 A Hybrid Discontinuous Galerkin Method

Here we introduce the essentials of HDG, for full details see Bui-Thanh [5].

For any matrix , we denote by its row and column respectively.

Let us define

|

|

and

|

|

We apply operators component-wise. For instance, for the divergence operator, we have,

|

|

We can write system (3) in the form

|

|

(4) |

Assume we have a valid element partition of the domain . In DG, functions are approximated locally in each element by polynomials, then coupled with others in adjacent elements by means of a numerical flux. The basic process is as follows.

Let be an element in the partition. Compute the inner product on of each side of (4) with a test function , to obtain

|

|

(5) |

Denoting the inner product in th eboundary of by we obtain after integrating by parts,

|

|

(6) |

Continuity is not enforced at the boundary of adjacent elements. Therefore, the boundary term is replaced with a boundary numerical flux where solves a Riemann problem with Cauchy data . As is standard, the – superscript denotes limits from the interior of , and the superscript, limits from the exterior. In this context, element is denoted by and the outer normal by .

To hybridize the flux, and break the coupling, is regarded as an extra unknown to be solved on the skeleton (the set of element edges ) of the mesh. Renaming as and as , the problem is to propose a suitable hybrid numerical flux .

Let us apply this scheme to equation (1) under the following condition

|

|

(7) |

This condition implies a dominant reaction term, which yields a tamed advection. Consequently, the diffusive flux is assumed to be continuous across any interface. Instead of the Riemann problem solution approach, we set the hybrid flux

|

|

(8) |

Notice the dependence only in the unknown .

For each element , the DG local unknown and the extra trace unknown need to satisfy

|

|

(9) |

This is complemented by a weak jump condition in the skeleton. Namely, for each edge

|

|

(10) |

where in (9), in (10) are polynomial test functions defined on elements and edges respectively.

Here, is the jump operator,

|

|

On each element, we are led to solving the equations (9) and (10). Let us show that this finite-dimensional problem is well-posed by showing that under null data, the solution is the trivial one.

Lemma. Assume condition (7) holds. If and on , then in .

Proof.

Let us split the test function in the form . The equation (9) using the hybrid flux can be written as

|

By integration by parts in (12)

|

|

(13) |

Let , and add equations (11) and (13) to obtain

|

|

.

Notice that in the boundary term, is the inner limit .

We are led to

|

|

Hence, on , and in . Equation (11) becomes

|

|

Integrating by parts

|

|

|

|

Since is arbitrary, , and consequently in each element .

We conclude that in .

Remark. Notice that the result is valid for Poisson problems, , .

3 Numerical results

Here, we illustrate some numerical results on a variety of problems, where the perturbed modified Helmholtz equation HDG solver serves as the computational engine.

The full code of the numerical implementation is available on GitHub:

https://github.com/Danalie/Hibrid-Discontinuos-Galerkin-DG2

We will test benchmark problems in rectangular geometries and regular meshes for simplicity.

We use the classical element functions on the reference segment for 1D applications. We denote by a -order bilinear approximation. In 2D, refer to basis functions on the reference square , as products of first-order and second-order one-dimensional 1D basis functions, respectively.

To report the accuracy of the approximation, we use the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). Sometimes, we normalize by the corresponding norm of the exact solution to obtain the Normalized Root Mean Square Error (NRMSE).

3.1 Poisson problems

For and in (1) we have the pure diffusion equation

|

|

To illustrate the HDG method with continuous diffusion numerical flux, as a Poisson solver, we consider as the identity matrix.

First a smooth Dirichlet Problem for Poisson's equation on the domain ,

|

|

The exact solution is . The numerical solution using on a grid yields to machine precision; no further refinement is necessary.

The DG method is -adaptative. Local high order is straightforward, and accurate approximations are possible on coarse meshes. For instance, we use for the Dirichlet problem

|

|

On a grid the is again zero to machine precision.

A preliminary comparison with the method in [7]. The latter relies on an internal-penalty numerical flux requiring a penalty parameter chosen heuristically, see (34) therein. Accuracy is shown in an exhaustive list of test problems. The simplest of such is the Dirichlet problem

|

|

with analytic solution is . Our solution is in Table 1.

| Elements by dimension | ||||

| 20 | 0.0051 | 1.97 | 5.71e-5 | 2.94 |

| 30 | 0.0022 | 2.07 | 1.7e-5 | 2.98 |

| 50 | 0.00079 | 2.00 | 3.7e-6 | 2.98 |

| 70 | 0.00041 | 1.94 | 1.34e-6 | 3.01 |

| 100 | 0.00022 | 1.74 | 4.57e-7 | 3.01 |

| 150 | 8.93e-5 | 2.22 | 1.34e-7 | 3.02 |

By inspection of Figure 7 in [7], it is apparent that our results compare favorably. A full comparison is to be carried out.

3.2 Helmholtz equation

We consider two benchmark problems in Coastal Ocean Modeling (COM) that lead to Helmholtz equations. A comparison is made with the Finite Volume (FVCOM) as presented in Chen et al [8]. Therein, FVCOM is applied for the modeling of tidal simulation in a semienclosed basin with tidal forcing at the open boundary under near-resonance conditions.

Here we apply HDG to illustrate the accurate simulation of the troublesome near resonance case. We remark that for the Helmholtz equation, condition (7) is not valid. Nevertheless, the numerical results are highly satisfactory.

3.2.1 A Rectangular Channel

Consider a fluid layer of uniform density that propagates along a channel aligned with the direction. More precisely, a semienclosed narrow channel with length and variable depth and a closed boundary at and an open boundary at .

Neglecting Coriolis force and advection of momentum, the governing equations modeling tidal waves propagation in the semienclosed channel (see Figure 1) are given as

|

|

Here, is the total water depth, is acceleration due to gravity, is speed in the direction, and is sea-level elevation.

|

| Figura 1: Configuration of the semienclosed channel. |

Assuming harmonic solutions,

|

|

we obtain the one dimensional Helmholtz problem for

|

|

(14) |

We specify a periodic tidal forcing with amplitude at the mouth of the channel,

|

|

and a no-flux boundary condition at the wall,

|

|

Let the channel depth decrease linearly toward the end of the channel, so that can be written as

|

|

It is readily seen that (14) is a Bessel's equation. With the given boundary conditions, the analytic solution is given by

|

|

where

|

|

are the Bessel's functions of degree zero and one respectively.

To compare with the HDG approximation, we solve the system,

|

|

Here we have defined in (14).

The following parameters are considered for a channel very close to resonance.

|

|

The HDG method is applied using nodal polynomials of degree 2 (). It is compared with the FV method and the analytic solution. For consistency with the FV method, we consider the approximation at the middle point of the element . As illustrated in Table 4, a second-order approximation with HDG in a coarse resolution is of greater quality than FV.

| Elements | NRMSE | NRMSE |

| 10 | 0.180784 | 22.3052 |

| 20 | 0.0748017 | 0.585413 |

| 40 | 0.0235224 | 0.553751 |

| 80 | 0.00684013 | 0.43336 |

| 160 | 0.00187985 | 0.297118 |

| 320 | 0.000495726 | 0.181964 |

| 640 | 0.000127432 | 0.102475 |

| 1280 | 0.0546902 |

The analytic solution describes a standing wave with a node point near the closed side of the channel. As expected, the reproduction of these features by HDG is accurate. See Figure 2

|

| Figura 2: Solution for the rectangular channel near resonance case, with HDG nodal with polynomials of degree 2 and 80 elements. |

Remark. As pointed out in Chen et al [8], regardless of the numerical method, a proper selection of horizontal resolution recover accurately this tidal resonance problem. We argue that the accuracy attained by HDG in coarse meshes yields a better choice.

3.2.2 A Sector Channel

Now consider a flat bottom channel in the form of a semicircular section, which in polar coordinates is defined from to in the radial direction and from to in the angular direction.

The semicircular line of radius corresponds to an open border, while along the semicircular line of radius and the two sides, they are closed, (Figure 3).

|

| Figura 3: Semienclosed sector channel in the polar region , . The sector is open at and closed elsewhere. |

The following equations govern the nonrotating tidal oscillation,

|

is the constant water depth, are the radial and angular velocity components, and is the free surface water elevation.

Assuming a harmonic solution,

|

|

we can reduce the equations (15-17) to an elliptic equation

|

|

(18) |

The physical boundary conditions are as follows

- At the open mouth of the channel, a harmonic tidal forcing is assumed,

- On the solid walls, null flux is prescribed,

|

|

|

|

The analytic solution of this boundary-value problem is:

|

|

where

|

|

are the th-order Bessel function of the first and second types.

Let us show the HDG solution in the rectangular domain .

Let denote the gradient with respect to and let

|

|

Equation (18) becomes a perturbation of the two-dimensional Helmholtz equation,

|

|

(19) |

We apply the fourth order () scheme developed above for a near-resonance case. The geometric parameter values are:

|

|

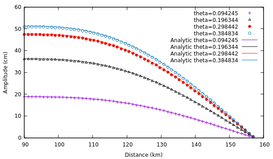

Figure (4) compares the analytic and numerical solutions. The relative mean square error is shown in Table 3.

|

|

| Figura 4: Comparison between the analytic solution to the sector problem with the solution using elements. a) Solution for some values, b) Solution for some values. | |

| Elements | NRMSE | NRMSE |

| 0.441213 | 0.920939 | |

| 0.009879 | 0.887757 | |

| 0.0026408 | 0.803039 | |

| 0.00115041 | 0.794262 |

Remark. Noteworthy, the solution is of grater quality that the FV solution. In regards to execution time, the former is attained in half a second on a personal laptop. A solution of the same quality would require in the order of minutes with the Finite Volume Method in a much finer mesh.

4 Conclussions

We have introduced a first-order system formulation for a regularly perturbed Modified Helmholtz equation. A discretization is derived by means of the Hybrid Discontinuous Galerkin method with an ad-hoc numerical flux. The well-posedness of the finite-dimensional HDG discrete linear system follows from a dominant reaction condition.

The preliminary comparison with a leading Poisson solver shows promise as a competitive alternative. Research on this is ongoing.

The proposed HDG discrete method is also applied to Helmholtz's problems arising from coastal ccean modeling. It outperforms the Finite Volume method commonly used in this setting.

The application to irregular regions with more general meshes is more elaborate but straightforward. Also, a parallel computing implementation is desired. Both tasks are left for future work.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

[1] Yaman, Olha Ivanyshyn and zdemir, Gazi. (2021) "Numerical solution of a generalized boundary value problem for the modified Helmholtz equation in two dimensions", Volume 190. Elsevier. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation 181–191

[2] Ivanyshyn Yaman, Olha and zdemir, Gazi. (2025) "An interior inverse generalized impedance problem for the modified Helmholtz equation in two dimensions", Volume 105. Wiley Online Library. ZAMM-Journal of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics/Zeitschrift für Angewandte Mathematik und Mechanik 1 e202300711

[3] Riviere, Béatrice. (2008) "Discontinuous Galerkin methods for solving elliptic and parabolic equations: theory and implementation". SIAM

[4] Di Pietro, Daniele Antonio and Ern, Alexandre. (2011) "Mathematical aspects of discontinuous Galerkin methods", Volume 69. Springer Science & Business Media

[5] Bui-Thanh, Tan. (2015) "From Godunov to a unified hybridized discontinuous Galerkin framework for partial differential equations", Volume 295. Elsevier. Journal of Computational Physics 114–146

[6] Gockenbach, Mark S. (2006) "Understanding and implementing the finite element method". SIAM

[7] Fischer, Nils L and Pfeiffer, Harald P. (2022) "Unified discontinuous Galerkin scheme for a large class of elliptic equations", Volume 105. APS. Physical Review D 2 024034

[8] Chen, Changsheng and Huang, Haosheng and Beardsley, Robert C and Liu, Hedong and Xu, Qichun and Cowles, Geoffrey. (2007) "A finite volume numerical approach for coastal ocean circulation studies: Comparisons with finite difference models", Volume 112. Wiley Online Library. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans C3

Document information

Published on 27/12/25

Submitted on 02/12/25

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?