m (Scipediacontent moved page Draft Content 983047476 to Gordillo et al 2019a) |

|||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | <span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_es"></span>[[#article_en|Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)]]</span> | |

| + | |||

| + | [[Media:Gordillo_et_al_2019a-75829.pdf|<span style="color:#0645AD; font-weight: bold">Download the PDF version</span>]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Resumen == | ||

| + | |||

| + | Despite the efforts made, there is still an alarming difference between the digital competence that teachers have and the one they should have in order to develop their students' digital competence. The lack of teacher training in safe and responsible use of ICT is a special cause for concern. Online courses in MOOC format meet all the required conditions to offer a possible solution to the unavoidable and urgent need for initial and in-service teacher training in this area of digital competence. However, there is currently no evidence in the literature on the effectiveness of these courses for this purpose. This study examines the instructional effectiveness of courses in MOOC format for teacher training in the safe and responsible use of ICT by analysing three different official courses. The courses were analysed using three different methods: a questionnaire to measure participants’ perceptions, pre-tests and post-tests to measure the knowledge acquired, and LORI (Learning Object Review Instrument) to measure the quality of digital educational resources created by the participants. The results suggest that online courses in MOOC format are an effective way to train teachers in the safe and responsible use of ICT, and that these courses can enable the development of digital competence in the area of content creation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =Resumen= | ||

| + | |||

| + | A pesar de los esfuerzos realizados, aún existe una alarmante diferencia entre la competencia digital que tienen los profesores y la que deberían tener para desarrollar la competencia digital en sus alumnos. De especial preocupación es la carencia de formación del profesorado en uso seguro y responsable de las TIC. Los cursos en línea con formato MOOC reúnen todas las condiciones necesarias para ofrecer una posible solución a la ineludible y apremiante necesidad de formación inicial y continua del profesorado en esta área de la competencia digital. Sin embargo, no existe actualmente evidencia en la literatura sobre la efectividad de estos cursos para tal cometido. Este estudio examina la efectividad instruccional de los cursos con formato MOOC para la formación del profesorado en el uso seguro y responsable de las TIC mediante el análisis de tres cursos oficiales diferentes. Estos se analizaron empleando tres instrumentos diferentes: un cuestionario para medir la percepción de los participantes, pre-tests y pos-tests para medir los conocimientos adquiridos y el instrumento LORI (Learning Object Review Instrument) para medir la calidad de recursos educativos digitales creados por los participantes. Los resultados sugieren que los cursos en línea con formato MOOC constituyen una forma efectiva de formar al profesorado en el uso seguro y responsable de las TIC, y que estos cursos pueden ayudar al desarrollo de la competencia digital en el área de creación de contenidos. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Keywords==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Digital competence, digital literacy, online courses, MOOC, online learning, teacher education, online protection, digital contents | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Keywords==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Competencia digital, alfabetización digital, cursos en línea, MOOC, aprendizaje en línea, formación del profesorado, protección en línea, contenidos digitales | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Introduction and state of the art== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Digital competence is one of the basic competences that all students should have acquired by the end of their compulsory education in order to develop as individuals and be able to successfully integrate in society (Diario Oficial de la Unión Europea, 2006). This competence can be defined as "that which involves the creative, critical and safe use of information and communication technologies in order to meet the goals related to work, employability, learning, use of free time, inclusion, and social participation” (Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, 2015: 10). In its most recent policies, actions and communications, the European Commission has confirmed that acquiring an adequate level of proficiency in the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) is one of its most relevant priorities (Comisión Europea, 2010, 2018). | ||

| + | |||

| + | In order to improve citizens’ level of digital competence, the European Commission has developed the framework “DigComp: The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens” (Vuorikari, Punie, Carretero, & Van den Brande, 2016). Despite the efforts made by government institutions, recent studies indicate that younger people, in spite of being considered “digital natives”, have an insufficient level of digital competence (Johnson & al., 2014; Pérez-Escoda, Castro-Zubizarreta, & Fandos-Igado, 2016). This fact is proof that digital competence is not inherently acquired by having access to the Internet and making intensive use of technology, but rather, specific training is required, an issue that had been previously pointed out in the literature (Fernández-Cruz & Fernández-Díaz, 2016; Napal, Peñalva-Vélez, & Mendióroz, 2018; Pérez-Escoda & al., 2016). Another related issue that previous studies have also raised is the threat of a new digital divide, not due to lack of access to technology, but due to lack of digital competence (Pérez-Escoda & al., 2016; Van-Deursen & Van-Dijk, 2011). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Teachers should play a central role in ensuring that their students acquire the digital competence they lack. Nonetheless, in order to successfully achieve this goal, it is necessary that teachers themselves have an adequate level of digital competence. In this regard, it should be taken into account that the use that educators make of ICT is very different from that of other professions (Røkenes & Krumsvik, 2014). For this reason, the term “teacher’s digital competence” has been coined to refer specifically to the “set of abilities, knowledge, skills, dexterity and attitudes related to the critical, safe and creative use of the information and communication technologies in education” (INTEF, 2017a: 2). In order to facilitate the development of teacher’s digital competence, several initiatives have emerged at both national and international levels. UNESCO published a framework describing the competences that teachers need to have in order to effectively use ICT in their professional practice (UNESCO, 2011). Subsequently, the European Commission developed the framework “DigCompEdu: European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators” (Redecker & Punie, 2017) with the aim of defining the digital competence that educators must have in order to succeed in making students digitally competent. In addition, the European Commission has elaborated a digital education action plan that includes eleven initiatives to support ICT use and development of digital competence in the educational context, which are meant to be applied before the end of 2020 (Comisión Europea, 2018). In Spain, the Instituto Nacional de Tecnologías Educativas y de Formación del Profesorado (INTEF) published the “Marco Común de Competencia Digital Docente”, conceived as a reference framework for diagnosing and improving the digital competence of teachers (INTEF, 2017b). Despite the numerous actions taken by different national and international organisations, results of recent research show that there is an alarming difference between the digital competence that teachers should have in order to develop digital competence in their students, and the one they actually have (Almerich, Suárez, Jornet, & Orellana, 2011; Falcó, 2017; Fernández-Cruz & Fernández-Díaz, 2016; Fernández-Cruz, Fernández-Díaz, & Rodríguez-Mantilla, 2018; Kaarakainen, Kivinen, & Vainio, 2018; Napal & al., 2018; Suárez-Rodríguez, Almerich, Díaz-García, & Fernández-Piqueras, 2012). Therefore, there is a compelling need for initial and in-service teacher training in digital competence. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Teacher’s digital competence encompasses multiple areas, as shown by the different frameworks developed to date (INTEF, 2017b; Redecker & Punie, 2017; UNESCO, 2011). Among the areas in which lack of training is of special concern, that related to safety and responsible use of technology stands out. There is strong evidence that teachers have a clear lack of knowledge in this area (De-los-Arcos & al., 2015; Falcó, 2017; Govender & Skea, 2015; Mannila, Nordén, & Pears, 2018; Napal & al., 2018; Pusey & Sadera, 2011; Shin, 2015). Specifically, previous studies have shown the lack of teacher training concerning the different risks to which children are exposed on the Internet (Govender & Skea, 2015; Mannila & al., 2018; Pusey & Sadera, 2011; Shin, 2015), device and personal data protection (Mannila & al., 2018; Napal & al., 2018; Pusey & Sadera, 2011), digital identity (Napal & al., 2018; Pusey & Sadera, 2011), rules of behaviour on the Internet (Falcó, 2017; Napal & al., 2018; Pusey & Sadera, 2011), and copyright and licensing of digital educational materials (De-los-Arcos & al., 2015; Falcó, 2017; Mannila & al., 2018; Napal & al., 2018; Pusey & Sadera, 2011; Shin, 2015). Without knowledge of these topics, teachers will hardly be able to educate their students in safe and responsible use of technology, as demanded by the teacher’s digital competence frameworks developed. This deficiency in teacher training is a severe problem given that there is a clear need to teach children to use technology in a safe and responsible way since they lack the necessary knowledge (Ey & Cupit, 2011; Gamito, Aristizabal, Vizcarra, & Tresserras, 2017; Sharples, Graber, Harrison, & Logan, 2009). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Teachers should play a central role in ensuring that their students acquire the digital competence they lack. Nonetheless, in order to successfully achieve this goal, it is necessary that teachers themselves have an adequate level of digital competence. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Children are not fully aware of many of the risks that Internet use entails (Ey & Cupit, 2011; Gamito & al., 2017), which is specially concerning considering that most of them are exposed to these risks from a very young age, sometimes leading them to experience adverse incidents (Garmendia, Jiménez, Casado, & Marcheroni, 2016). For this reason, educational institutions should teach children not only about privacy, digital identity, and rules of behaviour on the Internet, but also how to protect themselves against the various dangers of the Internet. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Another major deficiency is the lack of digital competence in creating digital educational materials (Fernández-Cruz & al., 2018; Napal & al., 2018; Ramírez-Montoya, Mena, & Rodríguez-Arroyo, 2017). One consequence of this deficiency is that currently, most teachers do not use authoring tools to create digital educational resources (Fernández-Cruz & al, 2018), which have proven to be capable of providing several benefits for student learning (Gordillo, Barra, & Quemada, 2017; Gürer & Yıldırım, 2014). This deficiency is not only due to the lack of skills in using authoring tools but also to the aforementioned lack of knowledge with regard to licensing of digital materials and copyright, which makes it difficult for teachers to reuse existing content on the web as well as to distribute their own creations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In view of the unavoidable and compelling need to train teachers to effectively develop their digital competence, new training actions must be undertaken. One possible solution is the use of courses in MOOC format for teacher training. MOOCs are online courses that allow for massive participation and that can be accessed without restriction and free of charge (Siemens, 2013). The overwhelming student-teacher ratio in MOOCs makes individual guidance and monitoring unfeasible, which is why these courses adopt instructional designs that are different from those of traditional online courses in order to allow massive assessment and feedback. The instructional design of a MOOC is a key aspect since it exerts a great influence on the motivation and academic performance of participants (Castaño, Maiz, & Garay, 2015). Based on MOOCs, new types of online courses have emerged such as SPOCs: courses with the same characteristics as MOOCs, except that the number of participants is relatively small and access is only granted to a specific group of people. The term “courses in MOOC format” encompasses all online courses with instructional designs that are characteristic of MOOCs, that is to say, courses that are designed to allow massive participation even if it does not occur. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Courses in MOOC format meet all the necessary conditions to offer a low-cost solution for initial and continuous training of all teachers in digital competence. In fact, prior studies have pointed out that teachers find these courses attractive for digital competence training (Castaño-Muñoz, Kalz, Kreijns, & Punie, 2018; Gómez-Trigueros, 2017; Ortega-Sánchez & Gómez-Trigueros, 2019). The suitability of courses in MOOC format for addressing teacher training deficiencies has not gone unnoticed by the European Union either, who led an initiative in 2018 to train teachers in safe Internet use through a MOOC (Better Internet for Kids, 2018). Although there is a notable and growing amount of research about MOOCs in the scientific literature (Chiappe-Laverde, Hine, & Martínez-Silva, 2015; Deng, Benckendorff, & Gannaway, 2019; Liyanagunawardena, Adams, & Williams, 2013; Veletsianos & Shepherdson, 2016), not enough attention has been devoted to examining the instructional effectiveness of these courses since, as Deng and others (2019) point out in their recent literature review, the measures of learning outcomes in MOOCs taken to date are not very sophisticated and are often based on a single variable such as the final grade or the completion rate. The majority of existing scientific literature on MOOCs has focused on topics such as course characteristics, types of MOOCs, challenges, potential impacts on education, participant characteristics and behaviour, and certification (Chiappe-Laverde & al., 2015; Deng & al., 2019; Liyanagunawardena & al., 2013; Veletsianos & Shepherdson, 2016). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Existing evidence on the effectiveness of courses in MOOC format aimed at teacher training in digital competence is even weaker than that which exists for MOOCs in general. Different experiences have been reported in the literature in which courses in MOOC format were used to train teachers in different areas of digital competence (Castaño-Muñoz & al., 2018; De-La-Roca, Morales, Teixeira, Hernandez, & Amado-Salvatierra, 2018; Gómez-Trigueros, 2017; Ramírez-Montoya & al., 2017; Sánchez-Elvira & Santamaría-Lancho, 2013; Tsvetkova, 2016). Notwithstanding, several of these studies did not carry out any evaluation of the effectiveness of the courses, and those that did only provided evidence obtained by means of questionnaires completed by the participants themselves as the sole instrument for gathering information. Whereas current evidence on the effectiveness of courses in MOOC format for training in teacher’s digital competence is scarce and weak, evidence that these courses can be effective in educating teachers in safe and responsible use of ICT is directly non-existent. Thus, further research is needed on the ability of courses in MOOC format to produce positive impacts on teachers in terms of learning outcomes related to digital competence and especially to the safe and responsible use of technology. This study examines the instructional effectiveness of courses in MOOC format for teacher training in safe and responsible use of ICT by means of the analysis of three official courses. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Research method== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The aim of this study is to provide empirical evidence on the effectiveness of online courses in MOOC format for teacher training in safe and responsible use of ICT, in order to determine whether this type of instruction is an adequate solution to remedy the existing lack of teacher training on this subject. The research questions were as follows: | ||

| + | |||

| + | a) Are courses in MOOC format an effective way of training teachers in safe and responsible use of ICT? | ||

| + | |||

| + | b) Are courses in MOOC format an effective way of developing in teachers the digital competence to create digital educational materials for teaching safe and responsible use of ICT? | ||

| + | |||

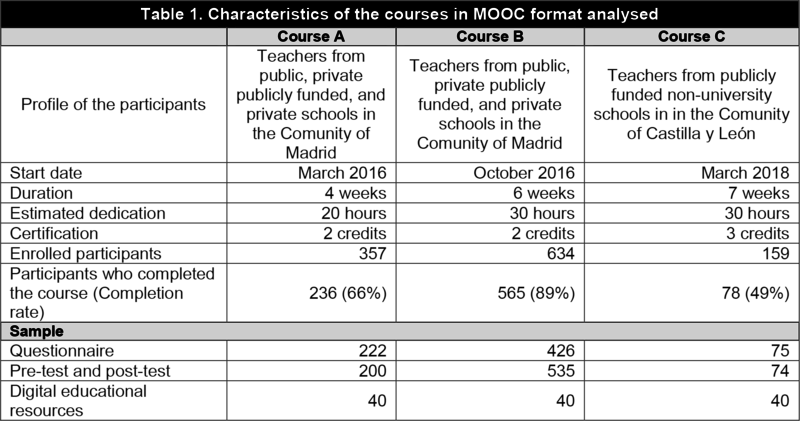

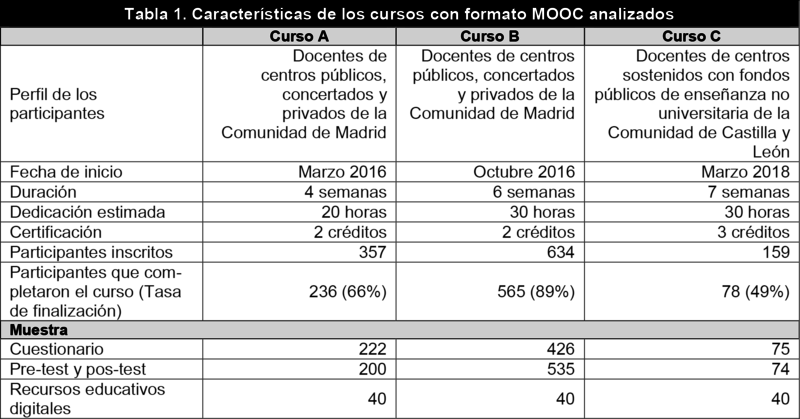

| + | Evidence of effectiveness was obtained through the analysis of three courses in MOOC format organised by official public entities, whose characteristics are summarised in Table 1. The three courses covered the following topics on safe and responsible use of ICT: digital identity, privacy management, risks for children associated with Internet use (including access to inappropriate content, identity theft, cyberbullying, grooming, sexting, dangerous online communities, and technology addiction), good practices in the use of social networks, rules of behaviour on the Internet (netiquette), and licensing of digital materials. These are subjects in which, as seen in the introduction, teachers generally have a great lack of knowledge. In addition to providing training in the aforementioned topics, the courses also aimed to help teachers develop their digital competence to create digital educational materials. The courses were delivered through a virtual learning environment and consisted of a wide range of resources and activities, including videos recorded by experts, interactive multimedia resources (which presented examples of practical cases), additional materials to be used in the classroom with students, video tutorials on how to use different applications, forums, links to external resources, self-assessment tests, guided exercises, and digital resource creation workshops with peer review evaluation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The final task in all the courses consisted of a workshop in which participants had to employ an authoring tool to create a digital educational resource about any of the topics related to safe and responsible use of ICT covered in the course. The aim of this final task was for participants to apply the digital competence acquired throughout the course to create and publish an educational resource that could be later utilised, both by themselves to teach their students how to make safe and responsible use of technology, as well as by other members of the educational community to educate on this subject and create new digital educational resources. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Gordillo_et_al_2019a-75829-cb201f6c-6bd7-43ab-ad6a-ce3698ded162-ueng-09-01.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/94e459dc-4253-4806-bc52-e840cc3b1053/image/cb201f6c-6bd7-43ab-ad6a-ce3698ded162-ueng-09-01.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Three different instruments were used for the analysis of the courses. In order to measure the participants’ perception of the different characteristics of the courses, a questionnaire was used, which had Likert questions with five possible answers (1 totally disagree – 5 totally agree) and closed-ended questions. These questionnaires were completed by the participants after finishing the courses. Two additional measures were taken with the aim of analysing the learning outcomes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On the one hand, the knowledge about safe and responsible use of ICT acquired by the participants during each course was measured by means of a pre-test and a post-test. The pre-test was the first activity completed by the participants whereas the post-test was the last one. Both tests were identical and were comprised of multiple-choice questions. On the other hand, with the aim of obtaining a measure of the digital competence for creating digital educational materials on safe and responsible use of ICT acquired by the participants during each course, the LORI instrument (Leacock & Nesbit, 2007) was used for evaluating, in each course, the quality of 40 educational resources created by participants chosen at random. Thus, 120 resources were evaluated, 14% of the total. Each one of these resources was evaluated by three reviewers with extensive experience in the use of LORI and in the creation of digital educational materials. The score for each criterion was obtained by averaging all the evaluations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Results== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Participants’ perception=== | ||

| + | |||

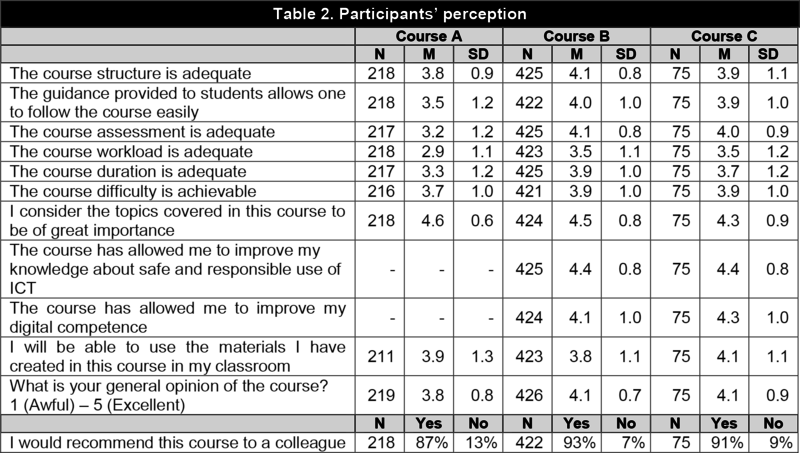

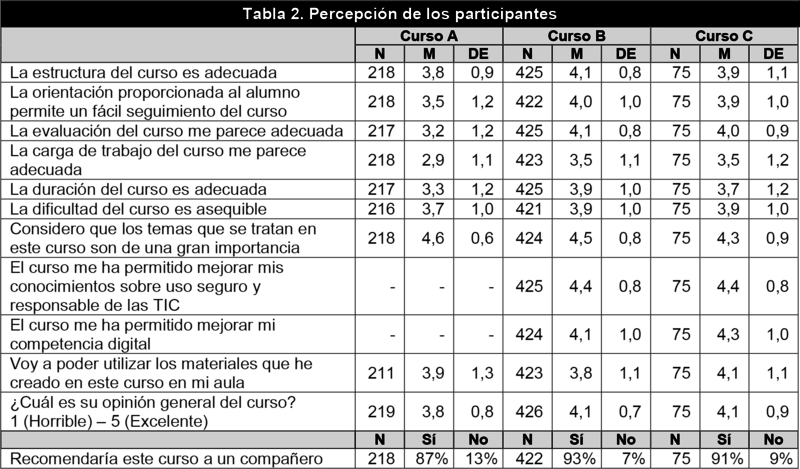

| + | The results of the questionnaire completed by the participants are shown in Table 2. The overall course scores lie within a range of 3.8-4.1 on a scale of 1 to 5, indicating that participants were, in general, satisfied with the training. The high degree of acceptance of the courses is also reflected in the fact that between 87 and 93% of the participants stated that they would recommend them to other teachers. The courses were rated positively in terms of structure, guidance, assessment, duration, and difficulty, although it is true that, in one of the courses analysed, the participants did not agree that the workload was adequate. The results evidence that the safe and responsible use of ICT is an important topic for teachers, and that the courses were effective for teacher training, not only in this area, but also in other areas of digital competence, such as digital content creation. Further proof of this latter fact is that teachers claimed that the digital resources they had created during the courses were of high enough quality that they could be used to teach their students how to use technology in a safe and responsible way. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Gordillo_et_al_2019a-75829-42730825-78f5-4629-bcff-496e9977ccf6-ueng-09-02.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/94e459dc-4253-4806-bc52-e840cc3b1053/image/42730825-78f5-4629-bcff-496e9977ccf6-ueng-09-02.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Acquired knowledge=== | ||

| + | |||

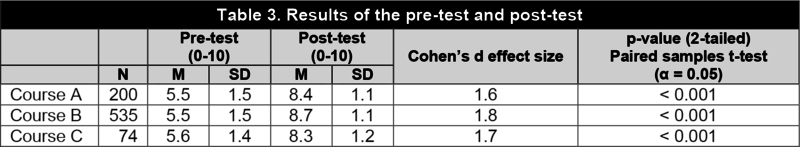

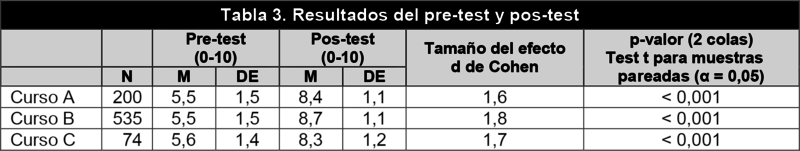

| + | Table 3 shows the results of the pre-test and post-test taken by the participants of the courses analysed. In order to determine the magnitude of the difference between the scores achieved by the participants in the post-test and the pre-test, the Cohen’s d effect size (Cohen, 1992) was calculated. When using Cohen’s d, a value of 0.2 indicates a small effect size; a value of 0.5, a medium one, and a value over 0.8, a large one. In all courses it was found that the difference between post-test and pre-test scores was statistically significant with a large effect size (with Cohen’s d values ranging from 1.6 to 1.8). These results prove that the courses had a strong positive impact on the participants in terms of knowledge acquired regarding safe and responsible use of ICT. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Gordillo_et_al_2019a-75829-51ab9f2e-a44c-4af6-8075-1584736619c5-ueng-09-03.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/94e459dc-4253-4806-bc52-e840cc3b1053/image/51ab9f2e-a44c-4af6-8075-1584736619c5-ueng-09-03.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Digital content creation=== | ||

| + | |||

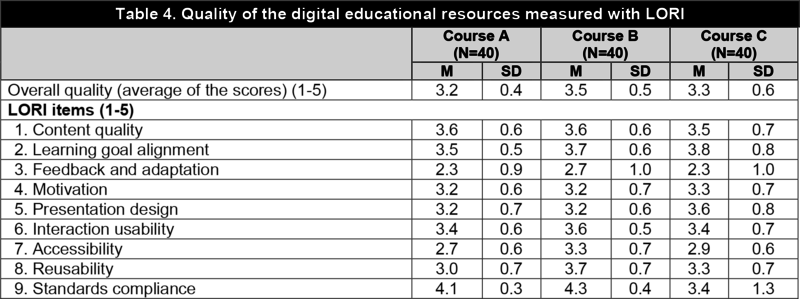

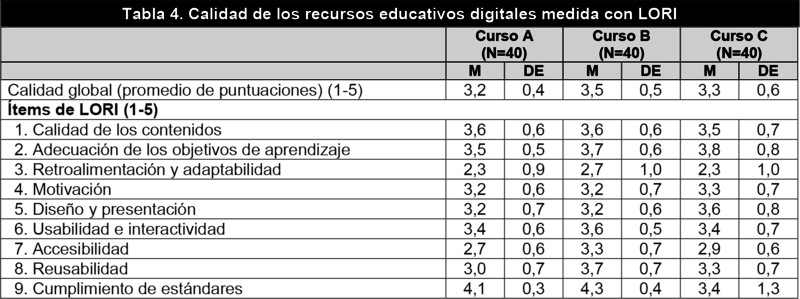

| + | Table 4 shows the results of the evaluation conducted with LORI to measure the quality of a sample of the digital educational resources created by the participants during the courses. The overall quality of the resources evaluated, calculated as the average of the scores obtained for each of the LORI items, reached an average score greater than 3 on a scale of 1 to 5 in all courses. Taking into account that educational resources rated above that threshold using LORI can be considered of good quality (Gordillo, Barra, & Quemada, 2014), it can be stated that most participants finished the course with an acceptable digital competence to create digital educational materials. However, about 30% of the participants of courses A and C, and 13% of those of course B were not capable of creating high-quality resources. Overall, the resources evaluated were positively rated in terms of content quality, learning goal alignment, motivation, design, usability, reusability and standards compliance. However, notable deficiencies were observed regarding the resources’ ability to provide feedback to students and adapt to their behaviour. Quality evaluations also show that teachers had difficulty creating accessible resources. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Gordillo_et_al_2019a-75829-73715474-d228-4a46-bdb5-42d76c0ff155-ueng-09-04.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/94e459dc-4253-4806-bc52-e840cc3b1053/image/73715474-d228-4a46-bdb5-42d76c0ff155-ueng-09-04.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Discussion and conclusions== | ||

| + | |||

| + | This study provides, for the first time, strong empirical evidence that online courses in MOOC format are an effective way of training teachers in safe and responsible use of ICT. Based on the results obtained, it can be stated that these courses offer a possible solution to the concerning lack of teacher training in the area of digital competence related to the safe and responsible use of technology. Given that measurements of learning outcomes in MOOCs reported in the scientific literature to date are overly simplistic and frequently based on a single variable such as the completion rate or the final grade (Deng & al., 2019), this study makes an important contribution to research on MOOC courses by reporting on the measurement of learning outcomes from three different courses, which is based on three aspects: the participants' perception, the knowledge acquired by the participants calculated as the difference between the scores achieved in a post-test and a pre-test, and the quality of a set of digital educational resources created by the participants during the courses. In this respect, an important finding of this study is that completion rates of courses in MOOC format should not be used as a measure of learning outcomes. Although the completion rate for the three courses analysed in this study was very varied (49%, 66% and 89%), the knowledge acquired by the participants who completed them was very similar. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This study also provides solid empirical evidence on the effectiveness of courses in MOOC format in the development of teacher’s digital competence to create digital content aimed at teaching how to make safe and responsible use of technology. Although Ramírez-Montoya and others (2017) previously reported on the use of a MOOC to train teachers in the creation of digital learning resources, that work did not provide any evidence on the real effectiveness of the course for that purpose. The results of this study show that most participants of the courses were capable of creating good-quality educational resources on safe and responsible ICT use and considered that they would be able to use these resources with their students. However, the results also show that a significant percentage of the participants (between 13% and 30% depending on the course) did not acquire the digital competence needed to create high-quality digital educational resources. Moreover, difficulties were observed on the teachers’ part in creating content with a high level of accessibility, as well as educational resources with the ability to provide feedback and adapt to the students’ behaviour. Nevertheless, these difficulties had their origin not only in a lack of digital competence, but also in the limitations of the current authoring tools. While the results obtained suggest that courses in MOOC format can be of great help for developing teacher’s digital competence to create digital educational materials, these also indicate that this help might not be sufficient for some educators. Future works should investigate the profile of these educators for whom other training activities could turn out to be more effective. The results also indicate that the training activities that address the content creation area of the digital competence should, in addition to teaching teachers how to use authoring tools, pay special attention to technical aspects such as accessibility and content reusability, and delve into the creation of adaptive resources and the provision of feedback. These training activities should include active learning, one of the most popular strategies for teacher training in ICT use (Røkenes & Krumsvik, 2014). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Future research works should examine the instructional effectiveness of online courses in MOOC format for teacher training in areas of teacher’s digital competence other than safe and responsible use of ICT and digital content creation. Another interesting line of research would be to compare the instructional effectiveness of courses in MOOC format with that of other training activities. Of special interest would be to analyse effectiveness according to the profile of the participants since, that way, it would be possible to determine when the use of courses in MOOC format is the most suitable solution for overcoming the training shortcomings of teachers, and when the most suitable solution is another type of training activity. Although the evidence provided by this study suggests that online courses in MOOC format can be an effective solution to the unavoidable need to train teachers in certain areas of digital competence, there might exist other training activities that are more effective for teachers with a specific profile. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ol><li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | AlmerichG., SuárezJ., JornetJ., OrellanaM., . 2011.[http://bit.ly/2XOU7by Las competencias y el uso de las tecnologías de información y comunicación (TIC) por el profesorado: estructura dimensional].Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa 13(1):28-42 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Better Internet for Kids (Ed.). 2018.[https://bit.ly/2TmG5PL #SaferInternet4EU campaign and Safer Internet Day 2018: Public report on campaign activities and successes]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Castaño-MuñozJ., KalzM., KreijnsK., PunieY., . 2018.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Who is taking MOOCs for teachers’ professional development on the use of ICT? A cross-sectional study from Spain&author=Castaño-Muñoz&publication_year= Who is taking MOOCs for teachers’ professional development on the use of ICT? A cross-sectional study from Spain].Technology, Pedagogy and Education 27(5):607-624 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | CastañoC., MaizI., GarayU., . 2015.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Diseño, motivación y rendimiento en un curso MOOC cooperativo. [Design, Motivation and Performance in a Cooperative MOOC Course]&author=Castaño&publication_year= Diseño, motivación y rendimiento en un curso MOOC cooperativo. [Design, Motivation and Performance in a Cooperative MOOC Course]]Comunicar 22(44):19-26 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Chiappe-LaverdeA., HineN., Martínez-SilvaJ.A., . 2015.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Literatura y práctica: Una revisión crítica acerca de los MOOC. [Literature and practice: A critical review of MOOCs]&author=Chiappe-Laverde&publication_year= Literatura y práctica: Una revisión crítica acerca de los MOOC. [Literature and practice: A critical review of MOOCs]]Comunicar 22(44):9-18 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | CohenJ., . 1992.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=A power primer&author=Cohen&publication_year= A power primer].Psychological Bulletin 112(1):155-159 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Comisión Europea (Ed.). 2010.[https://bit.ly/2VLzmk3 Comunicación de la Comisión al Parlamento Europeo, al Consejo, al Comité Económico y Social Europeo y al Comité de las Regiones: Una agenda digital para Europa]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Comisión Europea (Ed.). 2018.[https://bit.ly/2YCsVwN Comunicación de la Comisión al Parlamento Europeo, al Consejo, al Comité Económico y Social Europeo y al Comité de las Regiones sobre el plan de acción de educación digital]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | De-La-RocaM., MoralesM., TeixeiraA., HernandezR., Amado-SalvatierraH., . 2018.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=The experience of designing and developing an edX’s MicroMasters program to develop or reinforce the digital competence on teachers&author=De-La-Roca&publication_year= The experience of designing and developing an edX’s MicroMasters program to develop or reinforce the digital competence on teachers]. In: , ed. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Proceedings of the 2018 Learning With MOOCS conference (LWMOOCS 2018)&author=&publication_year= Proceedings of the 2018 Learning With MOOCS conference (LWMOOCS 2018)]. 2018:34-38 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | BrauDe-los-Arcos,, EshCirigottis, Gem, NacEgglestone,, RoiFarrow,, PolMcAndrew,, ArtPerryman, Lau, MarWeller,, . 2015.[https://bit.ly/2U97WzM OER data report 2013-2015: Building understanding of open education]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | DengR., BenckendorffP., GannawayD., . 2019.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Progress and new directions for teaching and learning in MOOCs&author=Deng&publication_year= Progress and new directions for teaching and learning in MOOCs].Computers and Education 129:48-60 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Diario Oficial de la Unión Europea (Ed.). 2006.[https://bit.ly/2JTJLDr Recomendación del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo de 18 de diciembre de 2006 sobre las competencias clave para el aprendizaje permanente (2006/962/CE)] | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | EyL.A., CupitC.G., . 2011.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Exploring young children’s understanding of risks associated with Internet usage and their concepts of management strategies&author=Ey&publication_year= Exploring young children’s understanding of risks associated with Internet usage and their concepts of management strategies].Journal of Early Childhood Research 9(1):53-65 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | FalcóJ.M., . 2017.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Evaluación de la competencia digital docente en la Comunidad Autónoma de Aragón&author=Falcó&publication_year= Evaluación de la competencia digital docente en la Comunidad Autónoma de Aragón].Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa 19(4):73-83 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fernández-CruzF.J., Fernández-DíazM.J., . 2016.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Generation Z's teachers and their digital skills. [Los docentes de la Generación Z y sus competencias digitales]&author=Fernández-Cruz&publication_year= Generation Z's teachers and their digital skills. [Los docentes de la Generación Z y sus competencias digitales]]Comunicar 24(46):97-105 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fernández-CruzF.J., Fernández-DíazM.J., Rodríguez-MantillaJ.M., . 2018.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=El proceso de integración y uso pedagógico de las TIC en los centros educativos madrileños&author=Fernández-Cruz&publication_year= El proceso de integración y uso pedagógico de las TIC en los centros educativos madrileños].Educación XX1 1(21):395-416 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | GamitoR., AristizabalM.P., VizcarraM.T., TresserrasA., . 2017.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=La relevancia de trabajar el uso crítico y seguro de Internet en el ámbito escolar como clave para fortalecer la competencia digital&author=Gamito&publication_year= La relevancia de trabajar el uso crítico y seguro de Internet en el ámbito escolar como clave para fortalecer la competencia digital].Fonseca 15:11-25 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | GarmendiaM., JiménezE., CasadoM.A., MarcheroniG., . 2016.[https://bit.ly/2EeNiaI Net Children go mobile: Riesgos y oportunidades en Internet y uso de dispositivos móviles entre menores españoles (2010-2015)] | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gómez-TriguerosI.M., . 2017.[http://bit.ly/2ZpELuC El MOOC como recurso para la adquisición de la competencia digital en la formación de los maestros de educación primaria].Revista de Tecnología de Información y Comunicación en Educación 11(1):77-88 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | GordilloA., BarraE., QuemadaJ., . 2014.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Towards a learning object pedagogical quality metric based on the LORI evaluation model&author=Gordillo&publication_year= Towards a learning object pedagogical quality metric based on the LORI evaluation model]. In: , ed. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Proceedings of the 2014 Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE 2014)&author=&publication_year= Proceedings of the 2014 Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE 2014)].3088-3095 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | GordilloA., BarraE., QuemadaJ., . 2017.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=An easy to use open source authoring tool to create effective and reusable learning objects&author=Gordillo&publication_year= An easy to use open source authoring tool to create effective and reusable learning objects].Computer Applications in Engineering Education 25(2):188-199 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | GovenderI., SkeaB., . 2015.[https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1681-4835.2015.tb00505.x Teachers’ understanding of e-safety: An exploratory case in KZN South Africa].Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries 70(1):1-17 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | M.D.Gürer,, Z.Yıldırım,, . 2014.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Effectiveness of learning objects in primary school social studies education: Achievement, perceived learning, engagement and usability&author=M.D.&publication_year= Effectiveness of learning objects in primary school social studies education: Achievement, perceived learning, engagement and usability].Egitim ve Bilim 39(176):131-143 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | INTEF (Ed.). 2017a.[https://bit.ly/2Eeyp8e Cinco años de evolución de la competencia digital docente]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | INTEF (Ed.). 2017b.[https://bit.ly/2BSzanb Marco Común de Competencia Digital Docente]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | JohnsonL., Adams-BeckerS., EstradaV., FreemanA., KampylisP., VuorikariR., PunieY., . 2014.[https://doi.org/10.2791/83258 Horizon report Europe: 2014 schools edition]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | KaarakainenM.T., KivinenO., VainioT., . 2018.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Performance-based testing for ICT skills assessing: A case study of students and teachers’ ICT skills in Finnish schools&author=Kaarakainen&publication_year= Performance-based testing for ICT skills assessing: A case study of students and teachers’ ICT skills in Finnish schools].Universal Access in the Information Society 17(2):349-360 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | LeacockT.L., NesbitJ.C., . 2007.[http://bit.ly/2F9IXqM A framework for evaluating the quality of multimedia learning resources].Educational Technology & Society 10(2):44-59 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | LiyanagunawardenaT.R., AdamsA.A., WilliamsS.A., . 2013.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=MOOCs: A systematic study of the published literature 2008-2012&author=Liyanagunawardena&publication_year= MOOCs: A systematic study of the published literature 2008-2012].The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning 14(3):202-227 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | MannilaL., NordénL.Å., PearsA., . 2018.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Digital competence, teacher self-efficacy and training needs&author=Mannila&publication_year= Digital competence, teacher self-efficacy and training needs]. In: , ed. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Proceedings of the 2018 ACM Conference on International Computing Education Research (ICER ’18)&author=&publication_year= Proceedings of the 2018 ACM Conference on International Computing Education Research (ICER ’18)].78-85 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte (Ed.). 2015.[http://bit.ly/2XOVyGY Orden ECD/65/2015]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | M.Napal,, A.Peñalva-Vélez,, A.M.Mendióroz,, . 2018.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Development of digital competence in secondary education teachers’ training&author=M.&publication_year= Development of digital competence in secondary education teachers’ training].Education Sciences 8(3):104-115 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ortega-SánchezD., Gómez-TriguerosI.M., . 2019.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Massive open online courses in the initial training of social science teachers: Experiences, methodological conceptions, and technological use for sustainable development&author=Ortega-Sánchez&publication_year= Massive open online courses in the initial training of social science teachers: Experiences, methodological conceptions, and technological use for sustainable development].Sustainability 11(3):578-588 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pérez-EscodaA., Castro-ZubizarretaA., Fandos-IgadoM., . 2016.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Digital skills in the Z Generation: Key questions for a curricular introduction in primary school. [La competencia digital de la Generación Z: Claves para su introducción curricular en la Educación Primaria]&author=Pérez-Escoda&publication_year= Digital skills in the Z Generation: Key questions for a curricular introduction in primary school. [La competencia digital de la Generación Z: Claves para su introducción curricular en la Educación Primaria]]Comunicar 24(49):71-79 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | PuseyP., SaderaW.A., . 2011.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Cyberethics, cybersafety, and cybersecurity: Preservice teacher knowledge, preparedness, and the need for teacher education to make a difference&author=Pusey&publication_year= Cyberethics, cybersafety, and cybersecurity: Preservice teacher knowledge, preparedness, and the need for teacher education to make a difference].Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education 28(2):82-85 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ramírez-MontoyaM.S., MenaJ., Rodríguez-ArroyoJ.A., . 2017.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=In-service teachers’ self-perceptions of digital competence and OER use as determined by a xMOOC training course&author=Ramírez-Montoya&publication_year= In-service teachers’ self-perceptions of digital competence and OER use as determined by a xMOOC training course].Computers in Human Behavior 77:356-364 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | RedeckerC., PunieY., . 2017. , ed. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=European framework for the digital competence of educators. DigCompEdu&author=&publication_year= European framework for the digital competence of educators. DigCompEdu]. Luxembourg: EU Publications. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | RøkenesF.M., KrumsvikR.J., . 2014.[http://bit.ly/2Rgk5SZ Development of student teachers’ digital competence in teacher education - A literature review].Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy 9(4):250-280 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sánchez-ElviraA., Santamaría-LanchoM., . 2013.[http://bit.ly/2XmEDyQ Developing teachers and students’ digital competences by MOOCs: The UNED proposal]. In: , ed. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Proceedings of the 2013 Open and Flexible Higher Education Conference&author=&publication_year= Proceedings of the 2013 Open and Flexible Higher Education Conference].362-376 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | SharplesM., GraberR., HarrisonC., LoganK., . 2009.[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2008.00304.x E-safety and Web 2.0 for children aged 11-16].Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 25(1):70-84 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ShinS.-K., . 2015.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Teaching critical, ethical and safe use of ICT in pre-service teacher education&author=Shin&publication_year= Teaching critical, ethical and safe use of ICT in pre-service teacher education].Language Learning & Technology 19(1):181-197 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | SiemensG., . 2013.[http://bit.ly/2RhB5bs Massive open online courses: Innovation in education?] In: McGrealR., KinuthiaW., MarshallS., eds. [https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Open Educational Resources: Innovation, research and practice&author=McGreal&publication_year= Open Educational Resources: Innovation, research and practice]. Athabasca University: Commonwealth of Learning. 5-16 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Suárez-RodríguezJ.M., AlmerichG., Díaz-GarcíaI., Fernández-PiquerasR., . 2012.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Competencias del profesorado en las TIC. Influencia de factores personales y contextuales&author=Suárez-Rodríguez&publication_year= Competencias del profesorado en las TIC. Influencia de factores personales y contextuales].Universitas Psychologica 11(1):293-309 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | TsvetkovaM.S., . 2016.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=The ICT competency MOOCs for teachers in Russia&author=Tsvetkova&publication_year= The ICT competency MOOCs for teachers in Russia].Olympiads in Informatics 10:79-92 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | UNESCO (Ed.). 2011.[https://bit.ly/2V9TuYC UNESCO ICT competency framework for teachers]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Van-DeursenA., Van-DijkJ., . 2011.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Internet skills and the digital divide&author=Van-Deursen&publication_year= Internet skills and the digital divide].New Media and Society 13(6):893-911 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | VeletsianosG., ShepherdsonP., . 2016.[https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=A systematic analysis and synthesis of the empirical MOOC literature published in 2013-2015&author=Veletsianos&publication_year= A systematic analysis and synthesis of the empirical MOOC literature published in 2013-2015].International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 17(2):198-221 | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | VuorikariR., PunieY., CarreteroS., Van-den-BrandeL., . 2016.[https://doi.org/10.2791/11517 DigComp 2.0: The digital competence framework for citizens. Update phase 1: the conceptual reference model]. Luxembourg: EU: Publications. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | </ol> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<hr> | <hr> | ||

<span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_en"></span>[[#article_es|Click to see the English version (EN)]]</span> | <span style="color:#FFFFFF; background:#ffffcc"><span id="article_en"></span>[[#article_es|Click to see the English version (EN)]]</span> | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | [[Media:Gordillo_et_al_2019a-75829_ov.pdf|<span style="color:#0645AD; font-weight: bold">Descarga aquí la versión PDF</span>]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Resumen == | ||

| + | |||

| + | A pesar de los esfuerzos realizados, aún existe una alarmante diferencia entre la competencia digital que tienen los profesores y la que deberían tener para desarrollar la competencia digital en sus alumnos. De especial preocupación es la carencia de formación del profesorado en uso seguro y responsable de las TIC. Los cursos en línea con formato MOOC reúnen todas las condiciones necesarias para ofrecer una posible solución a la ineludible y apremiante necesidad de formación inicial y continua del profesorado en esta área de la competencia digital. Sin embargo, no existe actualmente evidencia en la literatura sobre la efectividad de estos cursos para tal cometido. Este estudio examina la efectividad instruccional de los cursos con formato MOOC para la formación del profesorado en el uso seguro y responsable de las TIC mediante el análisis de tres cursos oficiales diferentes. Estos se analizaron empleando tres instrumentos diferentes: un cuestionario para medir la percepción de los participantes, pre-tests y pos-tests para medir los conocimientos adquiridos y el instrumento LORI (Learning Object Review Instrument) para medir la calidad de recursos educativos digitales creados por los participantes. Los resultados sugieren que los cursos en línea con formato MOOC constituyen una forma efectiva de formar al profesorado en el uso seguro y responsable de las TIC, y que estos cursos pueden ayudar al desarrollo de la competencia digital en el área de creación de contenidos. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =ABSTRACT= | ||

| + | |||

| + | Despite the efforts made, there is still an alarming difference between the digital competence that teachers have and the one they should have in order to develop their students' digital competence. The lack of teacher training in safe and responsible use of ICT is a special cause for concern. Online courses in MOOC format meet all the required conditions to offer a possible solution to the unavoidable and urgent need for initial and in-service teacher training in this area of digital competence. However, there is currently no evidence in the literature on the effectiveness of these courses for this purpose. This study examines the instructional effectiveness of courses in MOOC format for teacher training in the safe and responsible use of ICT by analysing three different official courses. The courses were analysed using three different methods: a questionnaire to measure participants’ perceptions, pre-tests and post-tests to measure the knowledge acquired, and LORI (Learning Object Review Instrument) to measure the quality of digital educational resources created by the participants. The results suggest that online courses in MOOC format are an effective way to train teachers in the safe and responsible use of ICT, and that these courses can enable the development of digital competence in the area of content creation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Keywords==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Competencia digital, alfabetización digital, cursos en línea, MOOC, aprendizaje en línea, formación del profesorado, protección en línea, contenidos digitales | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Keywords==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Digital competence, digital literacy, online courses, MOOC, online learning, teacher education, online protection, digital contents | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Introducción y estado de la cuestión== | ||

| + | |||

| + | La competencia digital es una de las competencias básicas que todos los estudiantes deben haber adquirido una vez finalizada la enseñanza obligatoria para desarrollarse como personas y poder integrarse adecuadamente en la sociedad (Diario Oficial de la Unión Europea, 2006). Esta competencia se puede definir como «aquella que implica el uso creativo, crítico y seguro de las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación para alcanzar los objetivos relacionados con el trabajo, la empleabilidad, el aprendizaje, el uso del tiempo libre, la inclusión y participación en la sociedad» (Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, 2015: 10). La adquisición de un nivel adecuado en el manejo de las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación (TIC) se ha confirmado como una de las prioridades más relevantes de la Comisión Europea en sus políticas, acciones y comunicaciones más recientes (Comisión Europea, 2010; 2018). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Con el objetivo de mejorar el nivel de competencia digital de los ciudadanos, la Comisión Europea ha desarrollado el marco «DigComp: The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens» (Vuorikari, Punie, Carretero, & Van-den-Brande, 2016). A pesar de los esfuerzos realizados por las instituciones gubernamentales, recientes estudios indican que los más jóvenes, aunque son considerados «nativos digitales», tienen un nivel de competencia digital insuficiente (Johnson & al., 2014; Pérez-Escoda, Castro-Zubizarreta, & Fandos-Igado, 2016). Este hecho es una prueba de que la competencia digital no se adquiere de forma inherente por disponer de acceso a Internet y hacer un uso intensivo de la tecnología, sino que es necesaria una formación específica, una cuestión que ya había sido manifestada previamente en la literatura (Fernández-Cruz & Fernández-Díaz, 2016; Napal, Peñalva-Vélez, & Mendióroz, 2018; Pérez-Escoda & al., 2016). Otra cuestión relacionada que también han planteado estudios anteriores es el peligro de una nueva brecha digital, no debida a la falta de acceso a la tecnología sino a la falta de competencia digital (Pérez-Escoda & al., 2016; Van-Deursen & Van-Dijk, 2011). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Los docentes deben desempeñar un papel central en la tarea de lograr que sus alumnos adquieran la competencia digital de la que adolecen. No obstante, para realizar esta labor con éxito, es necesario que ellos mismos tengan un nivel de competencia digital adecuado. A este respecto, debe tenerse en cuenta que el uso que los educadores hacen de las TIC es muy diferente al de otras profesiones (Røkenes & Krumsvik, 2014). Por este motivo, se ha acuñado el término «competencia digital docente» para hacer referencia específicamente al «conjunto de capacidades, conocimientos, habilidades, destrezas y actitudes en relación al uso crítico, seguro y creativo de las tecnologías de la información y comunicación en la docencia» (INTEF, 2017a: 2). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Con la finalidad de facilitar el desarrollo de la competencia digital docente del profesorado, han surgido diferentes iniciativas tanto a nivel nacional como internacional. La UNESCO publicó un marco que describe las competencias que los profesores necesitan para usar las TIC de una manera efectiva en su práctica profesional (UNESCO, 2011). Posteriormente, la Comisión Europea desarrolló el marco «DigCompEdu: European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators» (Redecker & Punie, 2017) a fin de definir la competencia digital docente que deben tener los educadores para conseguir que los estudiantes sean competentes digitalmente. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Además, la Comisión Europea ha elaborado un plan de acción de educación digital que incluye once iniciativas para apoyar el uso de las TIC y el desarrollo de la competencia digital en el ámbito educativo, las cuales se tiene intención de aplicar antes de que termine el año 2020 (Comisión Europea, 2018). En el ámbito español, el Instituto Nacional de Tecnologías Educativas y de Formación del Profesorado (INTEF) publicó el «Marco Común de Competencia Digital Docente», ideado como un marco de referencia para el diagnóstico y la mejora de la competencia digital del profesorado (INTEF, 2017b). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pese a las numerosas acciones llevadas a cabo por los diferentes organismos nacionales e internacionales, los resultados de investigaciones recientes muestran que existe una alarmante diferencia entre la competencia digital docente que deberían tener los profesores para desarrollar la competencia digital en sus alumnos y la que verdaderamente tienen (Almerich, Suárez, Jornet, & Orellana, 2011; Falcó, 2017; Fernández-Cruz & Fernández-Díaz, 2016; Fernández-Cruz, Fernández-Díaz, & Rodríguez-Mantilla, 2018; Kaarakainen, Kivinen, & Vainio, 2018; Napal & al., 2018; Suárez-Rodríguez, Almerich, Díaz-García, & Fernández-Piqueras, 2012). Por tanto, existe una necesidad imperiosa de formación inicial y continua del profesorado en competencia digital docente. | ||

| + | |||

| + | La competencia digital docente abarca múltiples áreas, como así lo muestran los diferentes marcos desarrollados hasta la fecha. Entre las áreas donde la falta de formación resulta especialmente preocupante destaca aquella relativa a la seguridad y al uso responsable de la tecnología. Existe una fuerte evidencia de que los profesores tienen una clara falta de conocimientos en esta área (De-los-Arcos & al., 2015; Falcó, 2017; Govender & Skea, 2015; Mannila, Nordén, & Pears, 2018; Napal & al., 2018; Pusey & Sadera, 2011; Shin, 2015). Concretamente, estudios anteriores han puesto de manifiesto la falta de formación de los profesores sobre los diferentes riesgos a los que están expuestos los menores en Internet (Govender & Skea, 2015; Mannila & al., 2018; Pusey & Sadera, 2011; Shin, 2015), protección de dispositivos y datos personales (Mannila & al., 2018; Napal & al., 2018; Pusey & Sadera, 2011), identidad digital (Napal & al., 2018; Pusey & Sadera, 2011), normas de comportamiento en la red (Falcó, 2017; Napal & al., 2018; Pusey & Sadera, 2011) y derechos de autor y licencias de materiales educativos digitales (De-los-Arcos & al., 2015; Falcó, 2017; Mannila & al., 2018; Napal & al., 2018; Pusey & Sadera, 2011; Shin, 2015). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Los docentes deben desempeñar un papel central en la tarea de lograr que sus alumnos adquieran la competencia digital de la que adolecen. No obstante, para realizar esta labor con éxito, es necesario que ellos mismos tengan un nivel de competencia digital adecuado. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sin conocimientos sobre estas materias, difícilmente podrán los profesores formar a sus alumnos en el uso seguro y responsable de la tecnología, como así lo demandan los marcos de competencia digital docente desarrollados. Esta deficiencia en la formación docente es un grave problema dado que existe una necesidad clara de enseñar a los menores a hacer un uso seguro y responsable de la tecnología, ya que estos carecen de los conocimientos necesarios (Ey & Cupit, 2011; Gamito, Aristizabal, Vizcarra, & Tresserras, 2017; Sharples, Graber, Harrison, & Logan, 2009). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Los menores no son plenamente conscientes de muchos de los riesgos que conlleva el uso de Internet (Ey & Cupit, 2011; Gamito & al., 2017), lo cual es especialmente preocupante teniendo en cuenta que la mayoría de ellos se expone a estos riesgos desde edades muy tempranas, llevándoles a experimentar en ocasiones incidentes negativos (Garmendia, Jiménez, Casado, & Marcheroni, 2016). Por este motivo, los centros educativos deberían enseñar a los menores, no solamente sobre privacidad, identidad digital y normas de comportamiento en línea, sino también a protegerse frente a los diversos peligros de Internet. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Otra carencia importante en la formación docente es la falta de competencia digital para crear materiales educativos digitales (Fernández-Cruz & al., 2018; Napal & al., 2018; Ramírez-Montoya, Mena, & Rodríguez-Arroyo, 2017). Una consecuencia de esta carencia es que actualmente la mayoría de profesores no utilizan herramientas de autor para crear recursos educativos digitales (Fernández-Cruz & al., 2018), los cuales han demostrado ser capaces de brindar beneficios significativos para el aprendizaje de los estudiantes (Gordillo, Barra, & Quemada, 2017; Gürer & Yıldırım, 2014). Esta carencia no se debe exclusivamente a la falta de habilidades para manejar herramientas de autor, sino también al desconocimiento en materia de licencias de materiales digitales y derechos de autor señalado anteriormente, el cual dificulta a los profesores reutilizar contenidos existentes en la red, así como distribuir sus propias creaciones. | ||

| + | |||

| + | En vista de la ineludible y apremiante necesidad de formar al profesorado para que desarrolle de forma efectiva su competencia digital, se deben emprender nuevas acciones formativas. Una posible solución es la utilización de cursos con formato MOOC para la formación del profesorado. Los MOOC son cursos en línea que permiten una participación masiva y a los que se puede acceder de forma libre y gratuita (Siemens, 2013). | ||

| + | |||

| + | El abrumador ratio estudiante-profesor en los MOOC provoca que la orientación y seguimiento individual de los estudiantes sea inviable, por lo que estos cursos adoptan diseños instruccionales distintos a los cursos en línea tradicionales a fin de permitir la evaluación y retroalimentación masiva. El diseño instruccional de un MOOC es un aspecto crucial, ya que tiene una alta influencia en la motivación y rendimiento académico de los participantes (Castaño, Maiz, & Garay, 2015). De la mano de los MOOC, han surgido nuevos tipos de cursos en línea basados en ellos como los SPOC: cursos con las mismas características que los MOOC, a excepción de que la cantidad de participantes es relativamente pequeña y el acceso está permitido solamente a un conjunto especifico de personas. El término «cursos con formato MOOC» abarca todos los cursos en línea con diseños instruccionales característicos de los MOOC, es decir, diseñados para permitir una participación masiva, aunque esta no se produzca. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Los cursos con formato MOOC reúnen todas las condiciones necesarias para ofrecer una solución de bajo coste para la formación inicial y continua de todos los docentes en competencia digital. De hecho, estudios anteriores han señalado que los profesores encuentran estos cursos atractivos para la formación en competencia digital (Castaño-Muñoz, Kalz, Kreijns, & Punie, 2018; Gómez-Trigueros, 2017; Ortega-Sánchez & Gómez-Trigueros, 2019). La idoneidad de los cursos con formato MOOC para resolver las carencias de formación docente tampoco ha pasado desapercibida para la Unión Europea, la cual llevó a cabo una iniciativa en el año 2018 para formar a profesores en el uso seguro de Internet a través de un MOOC (Better Internet for Kids, 2018). A pesar de existir una notable y creciente cantidad de investigaciones sobre los MOOC en la literatura científica (Chiappe-Laverde, Hine, & Martínez-Silva, 2015; Deng, Benckendorff, & Gannaway, 2019; Liyanagunawardena, Adams, & Williams, 2013; Veletsianos & Shepherdson, 2016), no se ha dedicado la suficiente atención a examinar la efectividad instruccional de estos cursos ya que, como señalan Deng y otros (2019) en su reciente revisión de la literatura, las medidas de los resultados de aprendizaje en los MOOC realizadas hasta la fecha son poco sofisticadas y a menudo se basan en una única variable, como la calificación final o la tasa de finalización. | ||

| + | |||

| + | La mayoría de la literatura científica existente sobre los MOOC se ha centrado en temas como las características de los cursos, tipos de MOOC, desafíos, impactos potenciales para la educación, características y comportamiento de los participantes y certificación (Chiappe-Laverde & al., 2015; Deng & al., 2019; Liyanagunawardena & al., 2013; Veletsianos & Shepherdson, 2016). La evidencia existente sobre la efectividad de cursos con formato MOOC destinados a la formación del profesorado en competencia digital es todavía menor a la existente para los MOOC en general. En la literatura se han reportado distintas experiencias en las que se emplearon cursos con formato MOOC para formar a docentes en distintas áreas de la competencia digital (Castaño-Muñoz & al., 2018; De-La-Roca, Morales, Teixeira, Hernandez, & Amado-Salvatierra, 2018; Gómez-Trigueros, 2017; Ramírez-Montoya & al., 2017; Sánchez-Elvira & Santamaría-Lancho, 2013; Tsvetkova, 2016). No obstante, varios de estos estudios no realizaron ninguna evaluación de la efectividad de los cursos, y los que sí lo hicieron solo aportaron evidencias obtenidas mediante la utilización de cuestionarios completados por los propios participantes como único instrumento de recogida de información. Si bien la evidencia actual sobre la efectividad de cursos con formato MOOC para la formación de la competencia digital docente es escasa y débil, la evidencia de que estos cursos pueden ser efectivos para educar a los profesores en el uso seguro y responsable de las TIC es directamente inexistente. Por tanto, resulta necesaria más investigación sobre la capacidad de los cursos con formato MOOC para producir impactos positivos en los docentes en términos de resultados de aprendizaje relacionados con la competencia digital, y en especial con el uso seguro y responsable de la tecnología. Este estudio examina la efectividad instruccional de los cursos con formato MOOC para la formación del profesorado en uso seguro y responsable de las TIC mediante el análisis de tres cursos oficiales. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Método de la investigación== | ||

| + | |||

| + | El objetivo de este estudio es aportar evidencia empírica sobre la efectividad de los cursos en línea con formato MOOC para la formación docente en uso seguro y responsable de las TIC, a fin de determinar si este tipo de instrucción constituye una solución adecuada para remediar la existente carencia de formación del profesorado en esta materia. Las preguntas de investigación fueron las siguientes: | ||

| + | |||

| + | a) ¿Son los cursos con formato MOOC una forma efectiva de formar al profesorado en el uso seguro y responsable de las TIC? | ||

| + | |||

| + | b) ¿Son los cursos con formato MOOC una forma efectiva de desarrollar en los profesores la competencia digital para crear materiales educativos digitales para la enseñanza del uso seguro y responsable de las TIC? | ||

| + | |||

| + | La evidencia sobre la efectividad se obtuvo mediante el análisis de tres cursos con formato MOOC organizados por entidades públicas oficiales, cuyas características se resumen en la Tabla 1. Los tres cursos cubrieron los siguientes temas sobre uso seguro y responsable de las TIC: identidad digital, gestión de la privacidad, riesgos para los menores asociados al uso de Internet (incluyendo acceso a contenidos inapropiados, suplantación de identidad, ciberacoso, «grooming», «sexting», comunidades virtuales peligrosas y tecnoadicciones), buenas prácticas para el uso de redes sociales, normas de comportamiento en la red (netiqueta) y licencias de uso de materiales digitales. Estos son temas de los cuales, como se ha visto en la introducción, los profesores tienen en general un gran desconocimiento. Además de proporcionar formación en los temas enumerados anteriormente, los cursos también tenían por objetivo ayudar a los profesores a desarrollar su competencia digital para crear materiales educativos digitales. Los cursos se impartieron mediante un entorno virtual de aprendizaje, y estaban compuestos por una amplia variedad de recursos y actividades, incluyendo vídeos grabados por expertos, recursos multimedia interactivos (los cuales presentaban ejemplos de casos prácticos), materiales adicionales para utilizar en el aula con los alumnos, videotutoriales para aprender cómo utilizar diferentes aplicaciones, foros, enlaces a recursos externos, cuestionarios autocorregibles, ejercicios guiados y talleres de creación de recursos digitales con evaluación por pares. En todos los cursos, la tarea final consistió en un taller, en el cual los participantes tuvieron que crear un recurso educativo digital sobre alguno de los temas relacionados con el uso seguro y responsable de las TIC, empleando una herramienta de autor. El objetivo de esta tarea final era que los participantes aplicasen la competencia digital adquirida para crear y publicar un recurso educativo que pudiera ser utilizado posteriormente, tanto por ellos mismos para enseñar a sus alumnos cómo hacer un uso seguro y responsable de la tecnología, como por otros miembros de la comunidad educativa para educar sobre esta materia y crear nuevos recursos educativos digitales. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Gordillo_et_al_2019a-75829_ov-f43b4e48-81fc-461e-8560-084f448521a9-u06-01.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/82a171be-b109-4b6e-8041-50d4a49be456/image/f43b4e48-81fc-461e-8560-084f448521a9-u06-01.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Para el análisis de los cursos se utilizaron tres instrumentos diferentes. Para medir la percepción de los participantes sobre diferentes características de los cursos se utilizó un cuestionario con preguntas tipo Likert con cinco opciones de respuesta (1 totalmente en desacuerdo – 5 totalmente de acuerdo) y preguntas cerradas. Estos cuestionarios fueron completados por los participantes tras la finalización de los cursos. A fin de analizar los resultados de aprendizaje, se realizaron dos mediciones adicionales. Por un lado, se midieron los conocimientos sobre uso seguro y responsable de las TIC adquiridos por los participantes durante cada curso mediante la realización de un pre-test y un pos-test. | ||

| + | |||

| + | El pre-test fue la primera actividad completada por los participantes, mientras que el pos-test fue la última. Ambos cuestionarios eran idénticos y estaban formados por preguntas de opción múltiple. Por otro lado, con el objetivo de obtener una medida de la competencia digital para crear materiales educativos digitales sobre uso seguro y responsable de las TIC adquirida por los participantes durante cada curso, se utilizó el instrumento LORI (Leacock & Nesbit, 2007) para evaluar la calidad de 40 recursos educativos creados por los participantes seleccionados al azar. Por tanto, se evaluaron 120 recursos, un 14% del total. Cada uno de estos recursos fue evaluado por tres revisores con amplia experiencia en el uso de LORI y en la creación de materiales educativos digitales. La puntuación de cada criterio fue obtenida promediando todas las evaluaciones. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Resultados== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Percepción de los participantes=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Los resultados del cuestionario completado por los participantes se muestran en la Tabla 2. Las valoraciones globales de los cursos están en el rango 3,8-4,1 en una escala de 1 a 5, lo que indica que los participantes estuvieron, en general, satisfechos con la acción formativa. El alto grado de aceptación de los cursos también se refleja en el hecho de que entre un 87 y un 93% de los participantes afirmó que los recomendarían a otros profesores. Los cursos fueron valorados positivamente en cuanto a su estructura, orientación, evaluación, duración y dificultad, aunque es cierto que, en uno de los cursos analizados, los participantes no estuvieron de acuerdo en que la carga de trabajo fuese adecuada. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Los resultados evidencian que el uso seguro y responsable de las TIC es un tema importante para los profesores, y que los cursos fueron efectivos para la formación docente, no solo en esta materia, sino también en otras áreas de la competencia digital como la creación de contenidos digitales. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Otra prueba de este último hecho es que los profesores afirmaron que los recursos digitales que habían creado durante los cursos tienen suficiente calidad como para ser utilizados para enseñar a sus alumnos cómo usar la tecnología de forma segura y responsable. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Gordillo_et_al_2019a-75829_ov-286ecd5a-17c3-4d0f-81e8-fe2e1fedf5c0-u06-02.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/82a171be-b109-4b6e-8041-50d4a49be456/image/286ecd5a-17c3-4d0f-81e8-fe2e1fedf5c0-u06-02.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Conocimientos adquiridos=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | La Tabla 3 muestra los resultados del pre-test y pos-test realizado por los participantes de los cursos analizados. A fin de determinar la magnitud de la diferencia entre las puntuaciones logradas por los participantes en el pos-test y el pre-test, se calculó el tamaño del efecto d de Cohen (Cohen, 1992). Cuando se utiliza la d de Cohen, un valor de 0,2 indica un tamaño del efecto pequeño; un valor de 0,5, uno medio, y un valor por encima de 0,8, uno grande. | ||

| + | |||

| + | En todos los cursos se encontró que la diferencia entre las calificaciones del pos-test y el pre-test es estadísticamente significativa con un tamaño del efecto grande (con valores de la d de Cohen comprendidos entre 1,6 y 1,8). Estos resultados demuestran que los cursos tuvieron un fuerte impacto positivo en los participantes en términos de conocimientos adquiridos sobre uso seguro y responsable de las TIC. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Gordillo_et_al_2019a-75829_ov-8fd14e87-7a99-45c3-b639-2dafbe5e6809-u06-03.png|center|800px|https://typeset-prod-media-server.s3.amazonaws.com/article_uploads/82a171be-b109-4b6e-8041-50d4a49be456/image/8fd14e87-7a99-45c3-b639-2dafbe5e6809-u06-03.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Creación de contenidos digitales=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | La Tabla 4 expone los resultados de la evaluación realizada con LORI para medir la calidad de una muestra de los recursos educativos digitales creados por los participantes durante los cursos. La calidad global de los recursos evaluados, calculada como el promedio de las puntuaciones obtenidas en cada uno de los ítems de LORI, obtuvo una media superior a 3 en una escala de 1 a 5 en todos los cursos. Teniendo en cuenta que los recursos educativos calificados por encima de ese umbral empleando LORI pueden ser considerados como de buena calidad (Gordillo, Barra, & Quemada, 2014), se puede afirmar que la mayoría de los participantes terminaron el curso con una competencia digital para crear materiales educativos digitales aceptable. Sin embargo, en torno a un 30% de los participantes de los cursos A y C y un 13% de los del curso B no fueron capaces de crear recursos de alta calidad. En términos generales, los elementos evaluados fueron calificados positivamente en términos de calidad de los contenidos, adecuación de los objetivos de aprendizaje, motivación, diseño, usabilidad, capacidad de reutilización y cumplimiento de estándares. No obstante, se observaron deficiencias notables en cuanto a la capacidad de los recursos para proporcionar retroalimentación a los alumnos y adaptarse a su comportamiento. Las evaluaciones de calidad también muestran que los profesores tuvieron dificultades para crear recursos accesibles. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid #BBB; margin: 1em auto; max-width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||