Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Resumen

Digital media are present in all areas of society, even configured as a new space for political socialization. This is especially applicable in the case of young people due to their high use of new technologies, as they are also trained with the necessary skills to do so. In this context, social networks have prompted the emergence of a new type of political participation: which takes place online. Therefore, this study delves into the relationship between the socialization that occurs in the network, digital skills and political participation online and offline. A quantitative survey-based methodology was used with university students from three Ibero-American countries: Mexico, Spain and Chile. The fieldwork was conducted between the months of December 2017 and June 2018. The results obtained show that young people consume mainly digital media, which does not prevent them from being critical with the quality they deserve. In this sense, the political participation actions in which they are involved are mostly developed in the network, thus participating to a lesser extent offline. Therefore, young people enter the world of politics through the consumption of information on the Internet, which favors a subsequent online political participation.

Resumen

Los medios digitales están presentes en todos los ámbitos de la sociedad, configurándose incluso como un nuevo espacio para la socialización política. Ello es especialmente aplicable en el caso de los jóvenes debido al elevado uso que realizan de las nuevas tecnologías, al estar capacitados también con las habilidades necesarias para ello. En este contexto, las redes sociales han propiciado el surgimiento de un nuevo tipo de participación política: la que tiene lugar de forma online. Por tanto, esta investigación indaga sobre la relación existente entre la socialización que se produce en la red, las habilidades digitales y la participación política en línea y fuera de línea. Se utiliza una metodología cuantitativa a partir de la realización de encuestas a jóvenes universitarios de México, España y Chile. El trabajo de campo se desarrolló entre los meses de diciembre de 2017 y junio de 2018. Los resultados obtenidos muestran que los jóvenes consumen principalmente medios digitales, lo cual no impide que sean críticos con la calidad que merecen los mismos. En relación con ello, las acciones de participación política en las que se implican se desarrollan en su mayoría en la red, participando así en menor medida fuera de línea. Por tanto, los jóvenes se introducen en el mundo de la política a través de Internet mediante el consumo de información, lo que favorece una posterior participación política online.

Keywords

Online learning, cyberactivism, survey, skills, young people, digital media, online civic engagement, socialization

Keywords

Aprendizaje en línea, ciberactivismo, encuesta, habilidades, jóvenes, medios digitales, participación online, socialización

Introduction

Digital media and political participation

In the last few years, beginning with the surge of social media, there is a new form of participation that takes place within cyberspace (Vesnic-Alujevic 2012). Political participation is understood as the set of actions and attitudes of citizens aimed at influencing the political system (Pasquino, 1996). In academia, the main topics of discussion in this respect are focused on the influence of traditional communication media on the discussion that occurs in social networks (Sveningsson, 2014; Gualda, Borrero, & Cañada 2015; Zaheer, 2016), as well as the capacity of social media to promote political participation, either online or offline (Bosetta, Dotceac, & Trenz, 2018). In this context, digital media are being configured as a new space for socialization (Resina, 2010), through which the individuals learn how to manage in this new online world (García-Peñalvo, 2016). Youth will be especially enveloped in this dynamic, as they are digital natives still in the process of shaping themselves.

In this respect, one of the most important learning activities in which youth are involved consists on learning how to be citizens. In agreement with this, digital media, as a new environment for political socialization, could contribute in the empowerment of youth to acquire the necessary abilities for participating in public life, as well as to develop new forms of activism (Hernández & al., 2013).

Therefore, new technologies are being shaped as the new stage for political participation. This could facilitate the implication of citizens in public life in a context of disaffection (Dalton, 2004), by contributing with overcoming the existing obstacles for offline participation (Grossman, 1995). In any case, this new form of political activism through the Internet would not substitute the traditional political participation offline, but it could be a complementary activity. As previous works have shown in the Mexican case, there is a strong relationship between both types of participation, online and offline (De-la-Garza & Barredo, 2017).

However, the concept of the internet as a facilitator of political activism has generated diverse objections from the academic field due to the existence of a digital divide which is based, in part, to the economic inequalities of access (Norris, 2001; DiMaggio & Hargittai 2001), and on the other hand, the inequality related to the digital skills needed for political participation online (Van-Dijk & Hacker, 2003; Hargittai 2002). In this scenario, age would condition access to new technologies, as well as the possession of digital skills needed for becoming politically involved through the internet (Albrecht 2006; Min 2010), as has been previously shown for the case of Spain (Recuero, 2016). In this sense, a prior interest in politics is required from the users in order to participate either online or offline (Casteltrione, 2016). Thus, many research studies mention that social networks such as Facebook re-enforce the civil commitment of politically-active users (Vromen, Loader, Xenos, & Bailo, 2016; Mascheroni, 2017), aside from favoring their move towards political action either online or offline (Min & Wohn, 2018).

Therefore, an interconnection would be produced between the three elements: socialization, digital skills and online/offline political participation. Thus, firstly, youth’s socialization in new technologies enables them to acquire new digital skills needed for utilizing the internet from every angle. These skills are the ones that subsequently facilitate the political socialization of youth, as they tend to introduce themselves into public life through new technologies. Therefore, young people can start to learn how to be citizens through the internet by politically participating online. This could favor the acquisition of new skills and competences that are political in character and that facilitate involvement in other types of offline participation. With the aim of recognizing how this phenomenon behaves in today’s youth, who began their process of socialization with these digital tools (Crovi, 2013), a comparative study was conducted between youth from the following Ibero-American countries: Mexico, Spain and Chile.

Youth in Mexico, Spain and Chile

In the last few years, youth have protagonized diverse activities of political participation that have been linked to their origin and/or their development with digital media. Experiences of this type can be identified in the three countries analyzed in the present research work. In Chile, the Chilean Student Winter was able to place the subject of public education in the political agenda (Aguilera, 2012; Zepeda, 2014), with the use of social media emerging as important. In this context, Vierner, Cárcamo and Scheihing (2018) posited that as the young Chileans showed an interest in politics, they had a greater tendency of adopting a critical posture against the massive communication media. Nevertheless, there was a high degree of political disaffection in Chile in young people (Mardones, 2014; Manríquez & Augusti, 2015).

As for Mexico, according to Morales (2002), youth’s mobilization has been fundamental for provoking institutional changes. With social movements after the emergence of #YoSoy132, a more participative citizenry has been strengthened with a clear commitment to diverse matters that concern this country (Portillo, 2015). It should be highlighted that the emergence of the active political participation in social media took place mainly after the birth of #YoSoy132 (Quiñónez, 2014). In the case of Spain, the new generations have more distrust towards the traditional media than social networks (Fernández, 2015).

One of the most important learning activities in which youth are involved consists on learning how to be citizens. In agreement with this, digital media, as a new environment for political socialization, could contribute in the empowerment of youth to acquire the necessary abilities for participating in public life, as well as to develop new forms of activism.

In agreement with this, Spanish youth have provided signs of their activism through the new technologies. In sometimes occasions, this online political participation has even been transferred to the traditional public space through offline political participation (García & al., 2014). The 15M movement and the Movement for Decent Housing are examples of this (Hernández & al., 2013; Haro & Sampedro 2011).

Material and methods

Objectives

The main objective of this study is to analyze the existing relationship between socialization on the Internet, the acquisition of digital skills and the political participations in both of its aspects, online and offline. In previous research, it has been shown that youth have a greater degree of activism online, as age is a variable that conditions online political participation (Norris, 2001; DiMaggio & Hargittai, 2001). Nevertheless, it is necessary to have a more in-depth understanding of the characteristics and constraints of this type of participation conducted by young people. In this respect, it has also been shown that the level of studies is a relevant variable (Albrecht, 2006; Recuero 2016), so that the combination of being young and having a high level of education would foster a greater digital activism. Therefore, the present study is focused on examining university students from Mexico, Spain and Chile, as they can fully participate politically, as legal adults. The analysis of this collective will allow us to verify whether digital media are shaped as a space for political participation in which youth learn how to become citizens.

Research design

In this study, a quantitative methodology is utilized starting with the design, application and analysis of a questionnaire given to young university students from Mexico, Spain and Chile. In the design of the questionnaire, two large sets of questions were formulated, which allowed for the comparison between countries.

In first place, we find those related with media consumption, which are aimed at identifying the digital socialization of youth, and which therefore mirror their related skills. In second place, we find the questions related to the political participation online as well as offline. In the formulation of the questions, the items proposed by previous research studies were taken into account. Thus, the reliability of the indicators utilized is guaranteed, as well as its comparability with other studies. Therefore, with respect to the consumption of media, the indicators proposed by Gómez and others (2013) in their study on political culture in the context of the presidential election in 2012 in Mexico, were taken into account.

With respect to the questions on online political participation, the items proposed by two research studies were included. Thus, a few of the elements utilized by Gil-de-Zúñiga and others (2010) were selected, such as the online signing of petitions about collective matters with which the students were in agreement. From the contribution by Vesnic-Alujevic (2012), the following activities were recovered: search for information on politics, read humorous content related to politics, watch a political video, share political information with others, participate or read discussions about politics, post information about politics in their profile, and post a “like” on a comment or a message from another user.

As for offline political participation, sometimes of the questions applied by Oser and others (2013) were included, such as contacting a politician about a public interest matter, contributing with an organization that seeks to influence public policies and others. Starting with the data collected with the use of the questionnaire, a descriptive analysis was conducted on the consumption of media as well as online and offline political participation of Mexican, Spanish and Chilean university students.

Sample

The size of the sample obtained in the study was composed of 1,239 interviews in the Mexican case, 627 interviews in the Spanish case, and 1,058 in the Chilean case. These interviews were given to Mexican, Spanish and Chilean students from public and private universities enrolled in different degrees. A non-probabilistic, convenience sampling was conducted, with the field work conducted between the second semester of 2017, and the first semester of 2018. The poll was applied through the Internet using the Google Forms platform. For the student’s participation in the poll, they were contacted by the professors from the universities that participated and collaborated in the study, so that access through the classroom is highlighted.

Results

Consumption and trust of conventional media

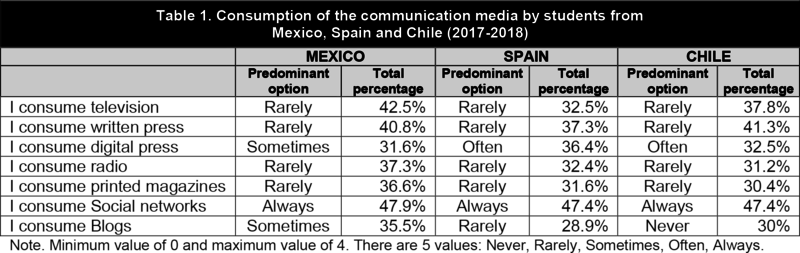

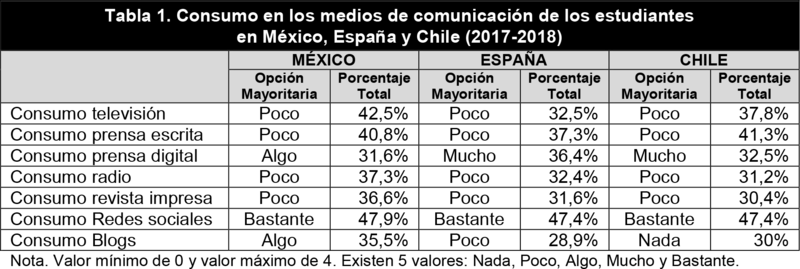

The results presented on Table 1 show the consumption of communication media for university students in Mexico, Spain and Chile. In this sense, the scarce exposure of this collective to audiovisual and written communication media was underlined. Thus, the type of media consumed least by Mexican youth was the television, as shown by most of those polled, with 42.5%, choosing the “rarely” option. In Spain and Chile, on their part, the printed press was the least consumed by university students, as most of them, 37.3% and 41.3%, respectively, indicated that they were exposed “rarely” to this medium. Following this, and with very similar results, we find the consumption of the printed press in the case of Mexican students (40.8%) and the consumption of television in the case of the Spanish and Mexican students (32.5% and 37.8%, respectively). Therefore, university youth from Mexico, Spain and Chile, have a scarce exposure to these types of media, with television and printed press reflecting the lowest consumption by all of them. Exposure to the other types of media is also reduced in the three countries examined, as shown by the numbers relative to the consumption of the radio and printed magazines.

In turn, the consumption of digital media was the greatest among the Mexican, Spanish and Chilean university students. In this respect, the high percentage of students in the three countries that confirmed utilizing social networks “always” was underlined, more specifically, 47.9% in Mexico, 47.4% in Spain, and 47.4% in Chile. The digital press, on its part, was consumed “often” by 36.4% of the Spanish and 32.5% of the Chileans, and “sometimes” by 31.6% of the Mexicans, a figure that is very close to those who declared being expose to it “often” (31.2%). As for the consumption of blogs, the behavior was less homogeneous. In this sense, it was notable that blogs were the digital media to which Ibero-American youth were least exposed to.

These data show how university students mainly and predominantly consume digital media, as compared to their scarce exposure to conventional media. Therefore, university youth share a pattern of behavior with respect to the consumption of media that is independent from the national context where they reside. This clearly shows that these young people are socializing through technological tools, so that they inform themselves about political matters through them.

|

|

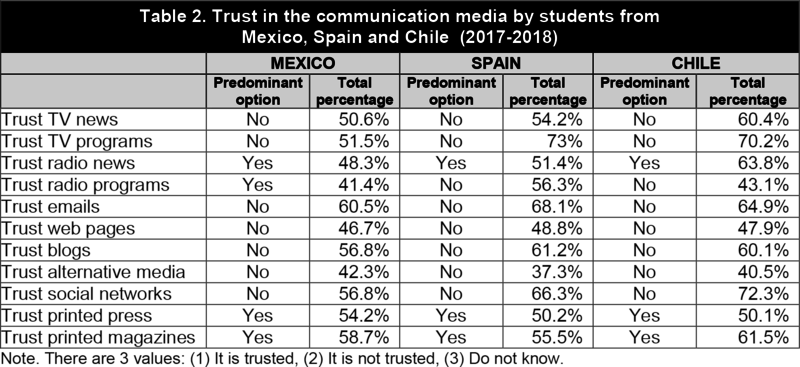

Nevertheless, the fact that these youths consume a type of media more than another does not imply that they are not able to discriminate their credibility. Related to this, Table 2 shows the results on the trust that the young Mexicans, Spanish and Chilean have on the communication media. It is noteworthy that the media that they trust the most are also the media that they least consume. Thus, most of the youth from Mexico, Spain and Chile only mentioned trusting the three conventional media. On the one hand, the printed magazines were trusted by 58.7% of the Mexican students, 55.5% of the Spanish students and 61.5% of the Chilean students, while on the other hand, and also predominantly, we find news from the radio, which generate credibility among 48.3% of Mexican youth, 51.4% of Spanish youth, and 63.8% of the Chilean youth. Lastly, 54.2% of those polled in Mexico, 50.2% in Spain, and 50.1% in Chile considered that the printed press also deserved credibility. Lastly, in the Mexican case, most of the students also trusted radio programs (41.4%).

The rest of the media, both conventional and digital, did not generate trust among the Ibero-American university students as a predominant option. As for the conventional media, the television programs generated the greatest consensus, as 51.5% of the Mexicans, 73% of the Spanish, and 70.2% of the Chileans did not trust them. The television news programs did not deserve credibility among most of the youth, with this option being predominant for 50.6% in Mexico, 54.2% in Spain, and 60.4% in Chile. As for the digital media, it is interesting to note that the students predominantly distrust them, despite their high consumption of this type of media. Thus, around six out of ten students did not trust email messages, social networks or blogs. In more detail, electronic mail did not generate trust among 60.5% of the Mexicans, 68.1% of the Spanish, and 64.9% of the Chileans.

|

|

In the case of the social networks, these numbers were 56.8%, 66.3% and 72.3%, respectively, with the results for blogs being 56.8%, 61.2% and 60.1%. Likewise, although the numbers were lower, the lack of trust on webpages were found to be 46.7% in Mexico, 48.8% in Spain, and 47.9% in Chile, with alternative media being 42.3% in Mexico, 37.3% in Spain and 40.5% in Chile. This information shows that the young, despite consuming digital media, are critical of the use they make of the new technologies. Thus, the fact that the young are socialized in the digital world enables them to have the ability to distinguish the quality of the medium they utilize.

Offline political participation

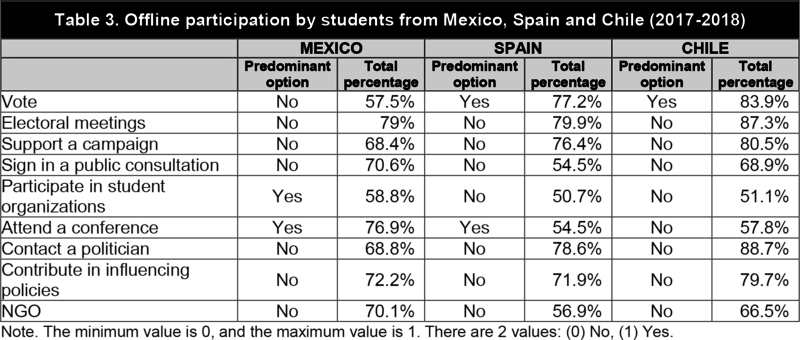

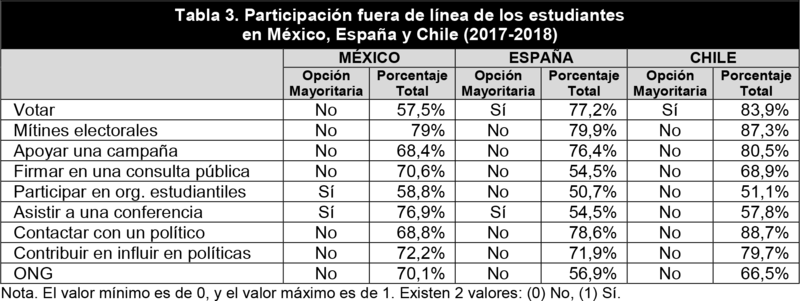

Table 3 shows the data on offline political participation by the young Ibero-American university students. In agreement with the results, this is mainly confined to the act of voting. Thus, most of those polled in Spain, 77.2%, and in Chile, 83.9%, confirmed being involved in the electoral political participation. Only Mexico was an exception to this pattern of behavior, as most of the young university students of the country, 57.5%, declared that they did not vote. In contrast, the Mexican students were greatly involved in other forms of offline political participation, such as attending a conference (76.9%) and participating in student organizations (58.8%). On the contrary, the Spanish and Chilean university students were not involved in other forms of participation, except for the former, with respect to attending a conference (54.5%).

The involvement of the youth on the remaining forms of offline activism was minor, especially in sometimes of them. Thus, more than seven out of ten polled attested to not participating in electoral meetings (79% in Mexico, 79.9% in Spain, and 87.3% in Chile), in contributing in influencing in public policies (72.2% in Mexico, 71.9% in Spain, and 79.7% in Chile), in contacting a politician (68.8% in Mexico, 78.6% in Spain, and 88.7% in Chile) and supporting a campaign (68.4% in Mexico, 76.4% in Spain, and 80.5% in Chile). These data show that the offline manners of participation mentioned were not an option for the youth for becoming involved politically. This modality can be favored by all of them and they are all related or promoted by the established political parties and the traditional political class. The participation in a NGO was also minor among the young university students in these countries, and it should be indicated that 70.1% of the Mexicans, 56.9% of the Spanish and 66.5% of the Chileans were not involved. Accordingly, most of the youth did not take part in the political participation activities offline, except for voting during elections. This implies the need to explore whether the political participation of university students is channeled through other venues, mainly through the Internet.

|

|

Online political participation

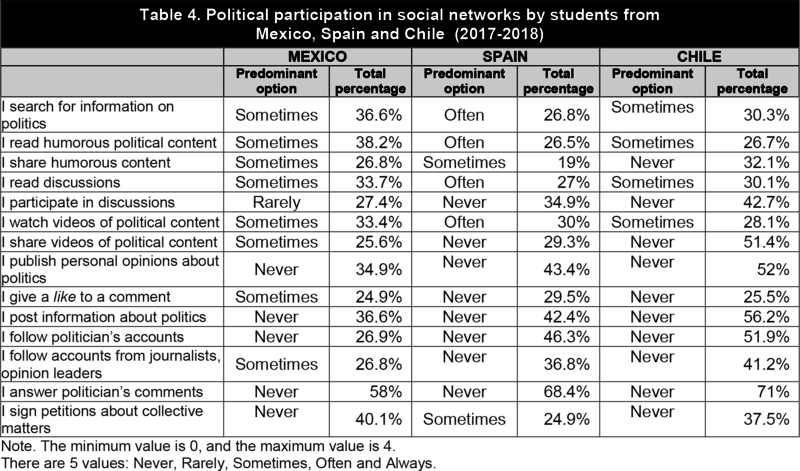

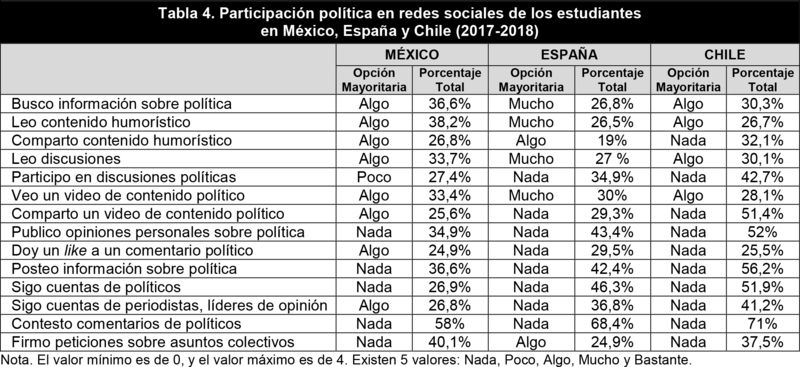

Table 4 shows the results related to online political participation. The existence of various forms of cyber activism that are conducted by most of the youth is notable. Thus, the most common acts of online participation conducted by Mexican, Spanish and Chilean university students were to search for information about politics, read humorous political content, read discussions on politics and watch political content.

Nevertheless, there are specificities between the different countries analyzed with respect to the diversity and intensity of the forms of online political participation conducted. In this sense, Mexicans were the ones who involved themselves to a greater degree in a great number of online participation activities, more specifically in nine of them. On the contrary, this participation did not reach a high intensity, as most of the students mentioned doing so “sometimes”. These forms of digital participation conducted “sometimes” by the Mexicans were: read humorous content about politics (38.2%), search for information about politics (36.6%), read discussions about politics (33.7%), watch videos of political content (33.4%), share humorous content about politics (26.8%), follow reporter’s and opinion leader’s accounts (26.8%), share a video of political content (25.6%), and give a “like” to a commentary about politics (24.9%). Likewise, 27.4% of the Mexicans participated in discussions about politics, although they did so “rarely”.

The Spanish on their part, became involved in a sometimeswhat smaller number of cyber activism activities, more specifically in six, although they did so with a greater intensity than the young Mexicans. Thus, most of the Spanish university students declared having participated “often” in watching videos of political content (30%), read discussion about politics (26.5%). Besides this, they affirmed having become involved “sometimes” in signing petitions about collective matters (24.9%) and in sharing humorous content about politics (19%). Lastly, the young Chileans were the ones that were the least involved in a smaller variety of online participation activities, more specifically, four. The intensity with which they participated in them was less than the Spanish university students, in line with what Mexican students do. Thus, most of the Chileans mentioned participating “sometimes” in searching information about politics (30.3%), read discussions about politics (30.1%), watch videos with political content (28.1%) and read humorous content about politics (26.7%).

The rest of the online participation activities were not conducted by most of the Ibero-American students. These forms of participation in which neither the Mexicans, Spanish nor Chileans were involved in, require a greater degree of activism. These are: publish personal opinions about politics, post information about politics, follow politician’s accounts and respond to politician’s comments. These results allow us to conclude that the young Mexican, Spanish and Chilean university students politically participate online to a greater degree than they do so offline. The forms of cyber activism they conducted had a passive component, as they are not related to the viewing or the reading of diverse types of content about politics. Nevertheless, the active search for political information is also a very commonly-conducted activity, which implies a more active role.

|

|

Discussion and conclusions

The new technologies have modified the habits of the citizens in all aspects of life. This new reality promotes the shaping of the digital media themselves into a new agent of socialization. In line with this, the political socialization that could be occurring at the heart of the internet takes on a special importance, especially with respect to the youth. In a time that the disaffection with the representation system pushes the citizens away from the traditional politics (Dalton, 2004), the new technologies could be shaping themselves as an alternative (Grossman, 1995). Due to this, it is of great interest to examine if the youth introduce themselves or not into politics through the Internet, and if this is the case, how this process is done and what the consequences are.

The aim of the present study was to investigate on the political socialization of the youth through the internet, the skills they have for this, and the political participation conducted online and offline. In this way, the intention was to verify if the youth initiated their contact with politics through the new technologies, hence previously requiring the necessary digital skills for this. Likewise, the aim of this contribution also aimed to observe if this online learning promoted or not the involvement of forms of online and offline participation. With this purpose, a poll was given to young university students from Mexico, Spain and Chile, reaching a sample size in each of the countries of 1,239, 627 and 1,058 students polled, respectively. The choice of the population studied is justified because the young university students are considered adults, which indicates that they can fully exercise their political rights, such as voting. The design of the poll was oriented towards obtaining information about two sets of questions. In first place, the consumption of media, as an indicator of political socialization, and on the trust placed on these media, as a reflection of the skills possessed by the youth. And in second place, on the political participation online as well as offline.

The results obtained show that the young Mexicans, Spanish and Chileans mainly consume digital communication media, so that they obtain political information through them. This is demonstrated by the social networks, followed by the digital press, being the sources to which they are most exposed to. Therefore, the youth introduced themselves to political matters through the new technologies, as it is through them that they know what is occurring in the political reality. This, together with their scarce exposure to the audiovisual and written communication media, confirms that the digital media play a political socialization role for these Ibero-American university students. Nevertheless, this political learning produced at the heart of the internet is not exempt of criticism by the youth. Thus, they are able to distinguish between credibility and trust that the media deserve, both conventional and digital. This especially important in the area of new technologies, in which the myriad of information available makes necessary being able to discriminate when facing the existence of numerous contents that are not reliable. In this sense, most of the university students from these countries do not trust the digital media they utilize, which implies that they count with an important ability to shape their own criteria, which is a necessity for performing as citizens. This civil socialization experienced by the youth in the internet seems to shape itself as a step prior to the learning of how to politically participate digitally. In this way, a significant part of the Spanish university students take part in activities of cyber activism. Nevertheless, the forms of online political participation they tend to conduct have a more passive character as they are related to reading or viewing of political content. In spite of this, they also take part in forms of participation that are more active, such a searching for political information.

As compared to the political activism that young Mexicans, Spanish and Chilean students partake in the digital networks, their decreased involvement is in offline political participation activities. Only the electoral participation, meaning voting, is predominant among the university students of the countries analyzed, except for Mexico. Nevertheless, and as already pointed out, both types of participation, online and offline, should not be considered completely different. In this sense, the consumption of political information on the internet by the youth, as well as the activities of activism they conduct online, can condition a posterior offline participation, such as voting. Nevertheless, it is necessary to continue to delve and broaden the analysis conducted in order to confirm the results obtained and to further delve into the learning about politics on the internet by the youth.

References

- AguileraO., . 2012.Repertorios y ciclos de movilización juvenil en Chile (2000-2012)Notas y Debates de la Actualidad 27(57):101-108

- AlbrechtS., . 2006.voice is heard in online deliberation? A study of participation and representation in political debates on the internet&author=Albrecht&publication_year= Whose voice is heard in online deliberation? A study of participation and representation in political debates on the internet.Information, Communication & Society 19(1):62-82

- BosettaM., DotceacA., TrenzH.J., . 2018.Political participation on Facebook during Brexit does user engagement on media pages stimulate engagement with campaigns?Journal of Language and Politics 17(2):173-194

- CasteltrioneI., . 2016.and political participation: Virtuous circle and participation intermediaries&author=Casteltrione&publication_year= Facebook and political participation: Virtuous circle and participation intermediaries.Interactions: Studies in Communication & Culture 7(2):177-196

- CroviD., . 2013.Jóvenes al fin, contraste de opiniones entre estudiantes y trabajadores. In: CroviD., GarayL.M., LópezR., PortilloM., eds. y apropiación tecnológica. La vida como hipertexto&author=Crovi&publication_year= Jóvenes y apropiación tecnológica. La vida como hipertexto. Distrito Federal: Sitesa/UNAM. 183-196

- DaltonR.J., . 2004.Democratic challenges, democratic choices. The erosion of political support in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- DarioDe-la-Garza,, DarioBarredo,, . 2017.Democracia digital en México: Un estudio sobre la participación de los jóvenes usuarios mexicanos durante las elecciones legislativas federales de 2015.Index Comunicación 7(1):95-114

- DiMaggioP., EHargittai, . 2001.From the ‘digital divide’ to ‘digital inequality’: Studying internet use as penetration increases. Working Paper nº 15. Center for Arts and Cultural Policy Studies, Woodrow Wilson School. Princeton: Princeton University.

- FernándezA., . 2015.que influyen en la confianza en los medios: explorando la asociación entre el consumo de medios y las noticias sobre el Movimiento 15M&author=Fernández&publication_year= Factores que influyen en la confianza en los medios: explorando la asociación entre el consumo de medios y las noticias sobre el Movimiento 15M.Hipertext 13:1-16

- GarcíaM.C., MercedesD.H., FernándezC., . 2014.comprometidos en la Red: El papel de las redes sociales en la participación social activa. [Engaged youth in Internet. The role of social networks in social active participation&author=García&publication_year= Jóvenes comprometidos en la Red: El papel de las redes sociales en la participación social activa. [Engaged youth in Internet. The role of social networks in social active participation]]Comunicar 43:35-43

- García-PeñalvoF.J., . 2016.socialización como proceso clave en la gestión del conocimiento&author=García-Peñalvo&publication_year= La socialización como proceso clave en la gestión del conocimiento.Education in the Knowledge Society 17(2):7-14

- H.Gil-de-Zúñiga,, A.Veenstra,, E.Vraga,, D.Shah,, . 2010.democracy: Reimagining pathways to political participation&author=H.&publication_year= Digital democracy: Reimagining pathways to political participation.Journal of Information Technology & Politics 7(1):36-51

- GómezS., TejeraH., AguilarJ., . 2013. , ed. cultura política de los jóvenes en México&author=&publication_year= La cultura política de los jóvenes en México. México: Colegio de México.

- GrossmanL.K., . 1995.The electronic republic: Reshaping democracy in the information age. New York: Viking.

- GualdaE., BorreroJ.D., CañadaJ.C., . 2015.‘Spanish Revolution’ en Twitter (2): Redes de hashtags y actores individuales y colectivos respecto a los desahucios en España&author=Gualda&publication_year= La ‘Spanish Revolution’ en Twitter (2): Redes de hashtags y actores individuales y colectivos respecto a los desahucios en España.Redes 26(1):1-22

- HargittaiE., . 2002.digital divide: Differences in people’s online skills&author=Hargittai&publication_year= Second-level digital divide: Differences in people’s online skills.First Monday 7(4):1-20

- HaroC., SampedroV., . 2011.Activismo político en Red: Del movimiento por la vivienda digna al 15M.Teknokultura 8(2):167-185

- E.Hernández,, M.C.Robles,, J.B.Martínez,, .interactivos y culturas cívicas: sentido educativo, mediático y político del 15M. [Interactive youth and civic cultures: The educational, mediatic and political meaning of the 15M&author=E.&publication_year= Jóvenes interactivos y culturas cívicas: sentido educativo, mediático y político del 15M. [Interactive youth and civic cultures: The educational, mediatic and political meaning of the 15M]]Comunicar 40:59-67

- ManríquezM.T., AugustiE.C., . 2015.Participación multi-asociativa de los jóvenes y espacio público: Evidencias desde el caso chileno.Revista Del CLAD Reforma y Democracia 62:167-192

- MardonesR., . 2014.encrucijada de la democracia chilena: una aproximación conceptual a la desafección política&author=Mardones&publication_year= La encrucijada de la democracia chilena: una aproximación conceptual a la desafección política.Papel Político 19(1):39-59

- MascheroniG., . 2017.A practice-based approach to online participation: Young people’s participatory habitus as a source of diverse online engagement.International Journal of Communication 11:4630-4651

- MinS.J., . 2010.the digital divide to the democratic divide: Internet skills, political interest, and the second-level digital divide in political internet use&author=Min&publication_year= From the digital divide to the democratic divide: Internet skills, political interest, and the second-level digital divide in political internet use.Journal of Information Technology & Politics 7(1):22-35

- MinS.J., WohnD., . 2018.the news that you don't like: Cross-cutting exposure and political participation in the age of social media&author=Min&publication_year= All the news that you don't like: Cross-cutting exposure and political participation in the age of social media.Computers in Human Behavior 83:24-31

- MoralesH., . 2002.de la movilización juvenil en México. Notas para su análisis&author=Morales&publication_year= Visibilidad de la movilización juvenil en México. Notas para su análisis.Última 17:11-39

- NorrisP., . 2001.Digital divide: Civil engagement, information poverty, and the internet worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- OserJ., HoogheM., MarienS., . 2013.online participation distinct from offline participation? A latent class analysis of participation types and their stratification&author=Oser&publication_year= Is online participation distinct from offline participation? A latent class analysis of participation types and their stratification.Political Research Quarterly 66(1):91-101

- PasquinoG., BartoliniS., CottaM., . 1996.de Ciencia Política&author=Pasquino&publication_year= Manual de Ciencia Política. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

- PortilloM., . 2015.Construcción de ciudadanía a partir del relato de jóvenes participantes del# YoSoy132.Global Media Journal México 12:1-18

- QuiñónezL.C., . 2014.y elecciones 2012: viejos y nuevos desafíos para la comunicación política en México&author=Quiñónez&publication_year= Medios y elecciones 2012: viejos y nuevos desafíos para la comunicación política en México.Nóesis 23(45):24-48

- RecueroF., . 2016. , ed. participación política online: Un análisis de sus condicionantes. Actas del XV Congreso Nacional de Educación Comparada: Ciudadanía mundial y educación para el desarrollo. Una mirada internacional&author=&publication_year= La participación política online: Un análisis de sus condicionantes. Actas del XV Congreso Nacional de Educación Comparada: Ciudadanía mundial y educación para el desarrollo. Una mirada internacional. Sevilla: Universidad Pablo de Olavide.

- ResinaJ., . 2010.Ciberpolítica, redes sociales y nuevas movilizaciones en España: El impacto digital en los procesos de deliberación y participación ciudadana.Mediaciones Sociales 7(2):143-164

- SveningssonM., . 2014.don’t like it and I think it’s useless, people discussing politics on Facebook´: Young Swedes’ understandings of social media use for political discussion&author=Sveningsson&publication_year= `I don’t like it and I think it’s useless, people discussing politics on Facebook´: Young Swedes’ understandings of social media use for political discussion.Cyberpsychology 8(3):1-16

- Van-DijkJ., HackerK., . 2003.digital divide as a complex and dynamic phenomenon&author=Van-Dijk&publication_year= The digital divide as a complex and dynamic phenomenon.The International Society 19(4):315-326

- Vesnic-AlujevicL., . 2012.participation and Web 2.0 in Europe: A case study of Facebook&author=Vesnic-Alujevic&publication_year= Political participation and Web 2.0 in Europe: A case study of Facebook.Public Relations Review 38(3):466-470

- ViernerM., CárcamoL., ScheihingE., . 2018.crítico de los jóvenes ciudadanos frente a las noticias en Chile. [Critical thinking of young citizens towards news headlines in Chile&author=Vierner&publication_year= Pensamiento crítico de los jóvenes ciudadanos frente a las noticias en Chile. [Critical thinking of young citizens towards news headlines in Chile]]Comunicar 54:101-110

- VromenA., LoaderB., XenosM., BailoF., . 2016.making through Facebook engagement: Young citizens’ political interactions in Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States&author=Vromen&publication_year= Everyday making through Facebook engagement: Young citizens’ political interactions in Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States.Political Studies 64(3):513-533

- ZaheerL., . 2016.Use of social media and political participation among university students.Pakistan Vision 17(1):295

- ZepedaR., . 2014.El movimiento estudiantil chileno: desde las calles al congreso nacional.RASE 7(3):689-695

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Los medios digitales están presentes en todos los ámbitos de la sociedad, configurándose incluso como un nuevo espacio para la socialización política. Ello es especialmente aplicable en el caso de los jóvenes debido al elevado uso que realizan de las nuevas tecnologías, al estar capacitados también con las habilidades necesarias para ello. En este contexto, las redes sociales han propiciado el surgimiento de un nuevo tipo de participación política: la que tiene lugar de forma online. Por tanto, esta investigación indaga sobre la relación existente entre la socialización que se produce en la red, las habilidades digitales y la participación política en línea y fuera de línea. Se utiliza una metodología cuantitativa a partir de la realización de encuestas a jóvenes universitarios de México, España y Chile. El trabajo de campo se desarrolló entre los meses de diciembre de 2017 y junio de 2018. Los resultados obtenidos muestran que los jóvenes consumen principalmente medios digitales, lo cual no impide que sean críticos con la calidad que merecen los mismos. En relación con ello, las acciones de participación política en las que se implican se desarrollan en su mayoría en la red, participando así en menor medida fuera de línea. Por tanto, los jóvenes se introducen en el mundo de la política a través de Internet mediante el consumo de información, lo que favorece una posterior participación política online.

ABSTRACT

Digital media are present in all areas of society, even configured as a new space for political socialization. This is especially applicable in the case of young people due to their high use of new technologies, as they are also trained with the necessary skills to do so. In this context, social networks have prompted the emergence of a new type of political participation: which takes place online. Therefore, this study delves into the relationship between the socialization that occurs in the network, digital skills and political participation online and offline. A quantitative survey-based methodology was used with university students from three Ibero-American countries: Mexico, Spain and Chile. The fieldwork was conducted between the months of December 2017 and June 2018. The results obtained show that young people consume mainly digital media, which does not prevent them from being critical with the quality they deserve. In this sense, the political participation actions in which they are involved are mostly developed in the network, thus participating to a lesser extent offline. Therefore, young people enter the world of politics through the consumption of information on the Internet, which favors a subsequent online political participation.

Keywords

Aprendizaje en línea, ciberactivismo, encuesta, habilidades, jóvenes, medios digitales, participación online, socialización

Keywords

Online learning, cyberactivism, survey, skills, young people, digital media, online civic engagement, socialization

Introducción

Medios digitales y participación política

En los últimos años, desde el surgimiento de los medios sociales, existe una nueva modalidad de participación que se ejerce dentro del ciberespacio (Vesnic-Alujevic, 2012). Por participación política entendemos el conjunto de acciones y actitudes de los ciudadanos orientadas a influir en el sistema político (Pasquino, 1996). En la academia los principales temas de discusión al respecto se centran en la influencia de los medios de comunicación tradicionales en la discusión que se da en las redes sociales (Sveningsson, 2014; Gualda, Borrero, & Cañada, 2015; Zaheer, 2016), así como en la capacidad de los medios sociales para promover la participación política, ya sea online u offline (Bosetta, Dotceac, & Trenz, 2018). En este contexto, los medios digitales se están configurando como un nuevo espacio de socialización (Resina, 2010), a través del cual los individuos aprenden a desenvolverse en este nuevo mundo en línea (García-Peñalvo, 2016). Los jóvenes se verían especialmente envueltos en esta dinámica al ser nativos digitales y encontrarse aún en proceso de formación.

A este respecto, uno de los aprendizajes más importantes en los que se ven envueltos los jóvenes consiste en aprender a ser ciudadanos. En consonancia con ello, los medios digitales, como nuevo ámbito de socialización política, podrían contribuir a capacitar a los jóvenes a adquirir las habilidades necesarias para participar en la vida pública, así como a desarrollar nuevas formas de activismo (Hernández, Robles, & Martínez, 2013). Por consiguiente, las nuevas tecnologías se están configurando como un nuevo escenario para la participación política. Ello podría facilitar la implicación de los ciudadanos en la vida pública en un contexto de desafección (Dalton, 2004), al contribuir a superar los obstáculos existentes para la participación offline (Grossman, 1995). En cualquier caso, esta nueva forma de activismo político a través de Internet no vendría a sustituir la tradicional participación política fuera de línea, sino que más bien sería un complemento de ella. Como reflejan trabajos previos en el caso mexicano, existiría una fuerte relación entre ambos tipos de participación, esto es, online y offline (De-la-Garza & Barredo, 2017).

Sin embargo, la concepción de la red como facilitador del activismo político ha generado diversas objeciones desde el ámbito académico por la existencia de una brecha digital basada, por una parte, en las desigualdades económicas de acceso (Norris, 2001; DiMaggio & Hargittai 2001) y, por otra, en la desigualdad relativa a las habilidades digitales necesarias para participar políticamente de forma online (Van-Dijk & Hacker, 2003; Hargittai 2002). En este escenario, la edad condicionaría tanto el acceso a las nuevas tecnologías como la tenencia de las habilidades digitales necesarias para implicarse políticamente a través de la Red (Albrecht, 2006; Min, 2010), algo que hemos constatado previamente en el caso español (Recuero, 2016). En este sentido, se requiere por parte de los usuarios un interés previo en la política para participar dentro o fuera de línea (Casteltrione, 2016). Así, diversas investigaciones señalan que las redes sociales como Facebook, refuerzan el compromiso cívico de los usuarios políticamente activos (Vromen, Loader, Xenos, & Bailo, 2016; Mascheroni, 2017), además de favorecer que pasen a la acción política tanto dentro como fuera de línea (Min & Wohn, 2018).

Por tanto, se produciría una interconexión entre tres elementos: socialización, habilidades digitales y participación política en línea y fuera de línea. Así, en primer lugar, la socialización de los jóvenes en la tecnología les capacita para adquirir las habilidades digitales necesarias para utilizar la Red en todas sus vertientes. Dichas habilidades son las que facilitan posteriormente la socialización política de los jóvenes, ya que suelen introducirse en la vida pública a través de la tecnología. Por tanto, los jóvenes pueden comenzar a aprender a ser ciudadanos a través de la Red participando políticamente de forma online. Ello puede favorecer la adquisición de habilidades y competencias de carácter político que faciliten la implicación en otras formas de participación offline. Con el fin de reconocer cómo se comporta este fenómeno en la juventud actual, que inició su proceso de socialización con estas herramientas digitales (Crovi, 2013), realizamos en este estudio una comparativa entre la juventud de los siguientes países iberoamericanos: México, España y Chile.

Juventudes en México, España y Chile

En los últimos años los jóvenes han protagonizado diversas acciones de participación política que han estado vinculadas en su origen y/o en su desarrollo con los medios digitales. Experiencias de este tipo pueden identificarse en los tres países objeto de análisis en la presente investigación. En Chile el movimiento Invierno Estudiantil Chileno logró posicionar en la agenda política el tema de la educación pública (Aguilera, 2012; Zepeda, 2014), siendo clave el uso de los medios sociales. En este contexto, Vierner, Cárcamo y Scheihing (2018) plantean que en la medida en que los jóvenes chilenos muestran interés en política, tienen una mayor tendencia a adoptar una postura crítica frente a los medios masivos de comunicación. No obstante, existiría un alto grado de desafección política en Chile por parte de la juventud (Mardones, 2014; Manríquez & Augusti, 2015).

En lo que respecta a México, según Morales (2002), la movilización de los jóvenes resulta fundamental para provocar cambios institucionales. Con las movilizaciones sociales posteriores a la emergencia del #YoSoy132, se ha fortalecido una ciudadanía más participativa con un compromiso claro con diversos asuntos que conciernen a este país (Portillo, 2015).

Uno de los aprendizajes más importantes en los que se ven envueltos los jóvenes consiste en aprender a ser ciudadanos. En consonancia con ello, los medios digitales, como nuevo ámbito de socialización política, podrían contribuir a capacitar a los jóvenes a adquirir las habilidades necesarias para participar en la vida pública, así como a desarrollar nuevas formas de activismo.

Cabe destacar que la emergencia de la activa participación política en medios sociales se dio fundamentalmente después del #YoSoy132 (Quiñónez, 2014). En el caso de España, las nuevas generaciones desconfían más de los medios tradicionales que de los medios sociales (Fernández, 2015). En consonancia con ello, los jóvenes españoles han dado muestras en los últimos años de su activismo a través de la tecnología. En algunas ocasiones esta participación política en línea ha conseguido incluso tener su traslado al espacio público tradicional a través de una participación política fuera de línea (García & al., 2014). El Movimiento del 15-M y el Movimiento por una Vivienda Digna serían reflejo de ello (Hernández & al., 2013; Haro & Sampedro 2011).

Material y métodos

Objetivos

El principal objetivo de este estudio es analizar la relación existente entre la socialización en Internet, la adquisición de habilidades digitales y la participación política en sus dos vertientes, esto es, en línea y fuera de línea. En investigaciones previas ha quedado demostrado que los jóvenes presentan un mayor grado de activismo en la red, al ser la edad una variable que condiciona la participación política en línea (Norris, 2001; DiMaggio & Hargittai, 2001). No obstante, es necesario conocer con mayor profundidad las características y condicionantes de este nuevo tipo de participación que desarrollan los jóvenes. A este respecto, también se ha demostrado que el nivel de estudios es una variable relevante (Albrecht, 2006; Recuero 2016), de modo que la conjunción entre ser joven y poseer un alto nivel educativo propiciaría un mayor activismo digital.

Por tanto, esta investigación se centra en examinar a los jóvenes universitarios de México, España y Chile, ya que son los que pueden participar políticamente de manera plena al ser mayores de edad. El análisis de este colectivo permitirá comprobar si los medios digitales se configuran o no como un espacio de participación política en el que los jóvenes aprenden a ser ciudadanos.

Diseño de la investigación

En este estudio se utiliza una metodología de carácter cuantitativo a partir del diseño, aplicación y análisis de una encuesta a los jóvenes universitarios mexicanos, españoles y chilenos. En el diseño del cuestionario se formularon dos grandes bloques de preguntas que permiten la comparación entre países. En primer lugar, aquellas relacionadas con el consumo de medios, las cuales están orientadas a identificar la socialización digital de los jóvenes y que reflejan, por consiguiente, las habilidades que disponen para ello. En segundo lugar, se encontrarían las preguntas relativas a la participación política tanto online como offline. En la formulación de las preguntas del cuestionario se tuvieron en cuenta los ítems propuestos por investigaciones previas. De este modo, se garantiza la fiabilidad de los indicadores utilizados y su comparabilidad con otros estudios. Así, en lo que respecta al consumo de medios, se tomaron en consideración los indicadores propuestos por Gómez y otros (2013) en su estudio sobre cultura política en el contexto de la elección presidencial de 2012 en México.

Con respecto a las preguntas sobre la participación política en línea, se incluyeron los ítems propuestos por dos investigaciones. En este sentido, se seleccionaron algunos de los elementos utilizados por Gil-de-Zúñiga y otros (2010), como la firma de peticiones en línea sobre asuntos colectivos con los que los jóvenes están de acuerdo. De la aportación de Vesnic-Alujevic (2012) se recuperaron las siguientes actividades: buscar información sobre política, leer contenido humorístico relacionado con política, ver un video político, compartir información sobre política con otros, participar o leer discusiones sobre política, postear información sobre política en su perfil y postear un «like» en un comentario o en algún mensaje de otro usuario. En cuanto a la participación política fuera de línea, se incluyeron algunas de las preguntas aplicadas por Oser y otros (2013), como contactar a un político sobre un asunto de interés público, contribuir en una organización que busca influir en políticas públicas y otras. A partir de los datos recabados con la aplicación de la encuesta, se realiza un análisis descriptivo sobre el consumo de medios y la participación política online y offline de los jóvenes universitarios mexicanos, españoles y chilenos.

Muestra

El tamaño de la muestra conseguido en el estudio consta de 1.239 entrevistas en el caso mexicano, de 627 entrevistas en el caso español y de 1.058 en el caso chileno. Dichas entrevistas fueron realizadas a jóvenes mexicanos, españoles y chilenos de universidades públicas y privadas de diferentes titulaciones. Se utilizó un muestreo no probabilístico de conveniencia, desarrollándose el trabajo de campo entre el segundo semestre del año 2017 y el primer semestre del año 2018. La encuesta fue aplicada a través de Internet mediante la plataforma Google Forms. El contacto con los estudiantes para su participación en la encuesta se realizó a través del personal docente de las universidades que participaron y colaboraron en el estudio, por lo que destaca el acceso a través del aula.

Resultados

Consumo y confianza en medios convencionales y digitales

Los resultados presentados en la Tabla 1 muestran el consumo de medios de comunicación de los jóvenes universitarios de México, España y Chile. En este sentido, destaca la escasa exposición de este colectivo a los medios de comunicación audiovisuales y escritos. Así, el medio que menos consumen los jóvenes en el caso de México es la televisión, al señalar la mayor parte de los encuestados, el 42,5%, la opción de «poco».

En España y Chile, por su parte, es la prensa escrita el medio menos consumido por los universitarios, ya que la mayor parte de los mismos, el 37,3% y el 41,3% respectivamente, indica que se expone «poco» a ella. Tras ello, y con cifras muy similares, se sitúa el consumo de prensa escrita en el caso de los estudiantes mexicanos (40,8%) y el consumo de televisión en el de españoles y chilenos, 32,5% y 37,8% respectivamente. Por tanto, los jóvenes universitarios de México, España y Chile presentan una escasa exposición a este tipo de medios, siendo los medios menos consumidos la televisión y la prensa escrita en todos ellos. La exposición al resto de medios también es reducida en los tres países examinados, como muestran las cifras relativas al consumo de radio y de revistas impresas. En cambio, el consumo de medios digitales es mayoritario entre los jóvenes universitarios mexicanos, españoles y chilenos. A este respecto destaca el elevado porcentaje que afirma en los tres países utilizar «bastante» las redes sociales, concretamente un 47,9% en México, un 47,4% en España y un 47,4% en Chile. La prensa digital, por su parte, es consumida «mucho» por el 36,4% de los españoles y el 32,5% de los chilenos; y «algo» por el 31,6% de los mexicanos, cifra bastante cercana a aquellos que declaran exponerse «mucho» a ella (31,2%).

En cuanto al consumo de blogs, el comportamiento es menos homogéneo. En este sentido, destaca que los blogs son los medios digitales a los que menos se exponen los jóvenes iberoamericanos. Estos datos muestran como los jóvenes universitarios consumen principalmente y de forma mayoritaria medios digitales, frente a su escasa exposición a los medios convencionales. De esta manera, la juventud universitaria comparte un patrón de comportamiento respecto al consumo de medios, independientemente del contexto nacional en el que viva. Ello refleja con claridad que los jóvenes se están socializando a través de las herramientas tecnológicas, de modo que se informan de los asuntos políticos a través de ellas.

|

|

No obstante, el hecho de que los jóvenes consuman un tipo de medios más que otros no implica que no sean capaces de discriminar la credibilidad de los mismos. En relación con ello, en la Tabla 2 se presentan los resultados relativos a la confianza que los jóvenes mexicanos, españoles y chilenos tienen en los medios de comunicación. Es reseñable que los medios en los que más confían los universitarios son aquellos que menos consumen. Así, la mayoría de los jóvenes de México, España y Chile solo señala confiar en tres medios convencionales. Por una parte, se sitúan las revistas impresas en las cuales confían el 58,7% de los mexicanos, el 55,5% de los españoles y el 61,5% de los chilenos. Por otra parte, y de forma también mayoritaria, se encuentran las noticias de radio, las cuales generan credibilidad entre el 48,3% de los jóvenes mexicanos, entre el 51,4% de los jóvenes españoles y entre el 63,8% de los jóvenes chilenos. Por último, el 54,2% de los encuestados en México, el 50,2% en España y el 50,1% en Chile considera que la prensa escrita también merece credibilidad. En el caso mexicano, además, la mayoría de los estudiantes confía también en los programas de radio (41,4%). El resto de medios, tanto convencionales como digitales, no genera confianza entre los universitarios iberoamericanos como opción mayoritaria. En cuanto a los medios convencionales, son los programas de televisión los que generan un mayor consenso, debido a que el 51,5% de los mexicanos, el 73% de los españoles y el 70,2% de los chilenos no confía en ellos. Las noticias de televisión tampoco merecen credibilidad entre la mayoría de los jóvenes, siendo esta la opción mayoritaria para el 50,6% en México, para el 54,2% en España y para el 60,4% en Chile.

En cuanto a los medios digitales, destaca el hecho de que los estudiantes no confíen de forma mayoritaria en ninguno de ellos a pesar del elevado consumo que realizan de los mismos. Así, en torno a seis de cada diez jóvenes no confían ni en los correos electrónicos, ni en las redes sociales, ni en los blogs. De modo más detallado, los correos electrónicos no generan confianza entre el 60,5% de los mexicanos, el 68,1% de los españoles y el 64,9% de los chilenos. En el caso de las redes sociales dichas cifras se sitúan en el 56,8%, el 66,3% y el 72,3% respectivamente, siendo en el caso de los blogs de un 56,8%, un 61,2% y un 60,1%. De modo similar, aunque con cifras inferiores, se sitúa la ausencia de confianza en las páginas web (46,7% en México, 48,8% en España y 47,9% en Chile) y en los medios alternativos (42,3% en México, 37,3% en España y 40,5% en Chile). Esta información muestra que los jóvenes, a pesar de realizar un alto consumo de medios digitales, son críticos en el uso que hacen de la tecnología. De este modo, el hecho de que los jóvenes estén socializados en el mundo digital posibilita que cuenten con la habilidad de distinguir la calidad del medio que utilizan.

|

|

Participación política offline

En la Tabla 3 pueden observarse los datos relativos a la participación política fuera de línea que realizan los jóvenes universitarios iberoamericanos. De acuerdo con los resultados, esta se circunscribe principalmente al acto de votar. Así, la gran mayoría de los encuestados en España, un 77,2%, y en Chile, un 83,9%, afirman implicarse en la participación política electoral. Solo el caso de México es una excepción a este patrón de comportamiento, debido a que la mayor parte de los jóvenes universitarios de este país, un 57,5%, declara que no acude a las urnas. Frente a ello, los estudiantes mexicanos se implican de forma mayoritaria en otras formas de participación política offline, como asistir a una conferencia (76,9%) y participar en organizaciones estudiantiles (58,8%). Por el contrario, los universitarios españoles y chilenos no se implican de modo mayoritario en otras acciones de participación, a excepción de los primeros en lo que respecta a asistir a una conferencia (54,5%).

|

|

La implicación de los jóvenes en el resto de formas de activismo fuera de línea es minoritaria, especialmente en algunas de ellas. Así, más de siete de cada diez encuestados afirman no participar en mítines electorales (79% en México, 79,9% en España y 87,3% en Chile), en contribuir a influir en políticas públicas (72,2% en México, 71,9% en España y 79,7% en Chile), en contactar con un político (68,8% en México, 78,6% en España y 88,7% en Chile) y en apoyar una campaña (68,4% en México, 76,4% en España y 80,5% en Chile). Estos datos muestran que las mencionadas formas de participación fuera de línea no son una opción para los jóvenes al implicarse políticamente. Esta modalidad puede verse favorecida por estas, todas ellas relacionadas o promovidas por los partidos políticos establecidos y la clase política tradicional. La participación en una ONG también es minoritaria entre los jóvenes universitarios de estos países, al indicar que no se implican en ella el 70,1% de los mexicanos, el 56,9% de los españoles y el 66,5% de los chilenos. Por consiguiente, la mayoría de los jóvenes no toma parte de las acciones de participación política fuera de línea, a excepción de la votación en elecciones. Ello supone la necesidad de explorar si la participación política de los universitarios se canaliza o no a través de otras vías, principalmente a través de la Red.

Participación política online

En la Tabla 4 se presentan los resultados relativos a la participación política online. Destaca la existencia de varias formas de ciberactivismo que son realizadas por una mayor proporción de los jóvenes. Así, las acciones de participación en línea más realizadas por los universitarios mexicanos, españoles y chilenos son buscar información sobre política, leer contenido humorístico sobre política, leer discusiones sobre política y ver vídeos de contenido político. No obstante, existen especificidades entre los diferentes países analizados respecto a la diversidad e intensidad de las formas de participación política online realizadas. En este sentido, los mexicanos son los que se implican en mayor proporción en un mayor número de acciones de participación en línea, concretamente en nueve. Dicha participación no alcanza por el contrario una gran intensidad, ya que la mayor parte de los jóvenes señalan realizarlas «algo». Estas formas de participación digital realizadas «algo» por los mexicanos son: leer contenido humorístico sobre política (38,2%), buscar información sobre política (36,6%), leer discusiones sobre política (33,7%), ver vídeos de contenido político (33,4%), compartir contenido humorístico sobre política (26,8%), seguir cuentas de periodistas y líderes de opinión (26,8%), compartir un vídeo de contenido político (25,6%), y dar like a un comentario sobre política (24,9%). Asimismo, el 27,4% de los mexicanos participa en discusiones sobre política, aunque lo hacen «poco».

|

|

Los españoles, por su parte, se implican en un número algo menor de acciones de ciberactivismo, concretamente en seis, aunque lo hacen con mayor intensidad que los jóvenes mexicanos. De este modo, la mayor parte de los universitarios españoles declara participar «mucho» en ver vídeos de contenido político (30%), en leer discusiones sobre política (27%), en buscar información sobre política (26,8%) y en leer contenido humorístico sobre política (26,5%). Además de ello, afirman implicarse «algo» en firmar peticiones sobre asuntos colectivos (24,9%) y en compartir contenido humorístico sobre política (19%).

Por último, los jóvenes chilenos son los que se implican en una menor variedad de acciones de participación en línea, concretamente en cuatro. La intensidad con la que participan en ellas es menor que la que desarrollan los universitarios españoles, estando en línea con la que ejercen los jóvenes mexicanos. Así, la mayor parte de los chilenos declaran participar «algo» en buscar información sobre política (30,3%), en leer discusiones sobre política (30,1%), en ver vídeos de contenido político (28,1%) y en leer contenido humorístico sobre política (26,7%). El resto de acciones de participación en línea no son realizadas por la mayor parte de los jóvenes iberoamericanos. Estas formas de participación en las que no se implican ni los mexicanos, ni los españoles, ni los chilenos requieren un mayor grado de activismo, siendo estas publicar opiniones personales sobre política, postear información sobre política, seguir cuentas de políticos y contestar comentarios de políticos. Estos resultados permiten concluir que los jóvenes universitarios mexicanos, españoles y chilenos participan políticamente de manera online en mayor medida de la que lo hacen fuera de línea. Las formas de ciberactivismo que más realizan tienen un componente pasivo, al estar relacionadas con el visionado o la lectura de diversos tipos de contenido sobre política. No obstante, la búsqueda activa de información política también es una actividad bastante realizada, lo cual implica un rol más activo.

Discusión y conclusiones

La tecnología ha modificado los hábitos de los ciudadanos en todas las facetas de la vida. Esta nueva realidad propicia que los propios medios digitales se configuren como un nuevo agente de socialización. En relación con ello, cobra especial importancia la socialización política que podría estarse produciendo en el seno de la red, especialmente en lo que respecta a los jóvenes. En un momento en el que la desafección con el sistema representativo lleva a los ciudadanos a alejarse de la política tradicional (Dalton, 2004), las nuevas tecnologías podrían estar configurándose como una alternativa (Grossman, 1995). Por ello, resulta de gran interés examinar si los jóvenes se introducen o no en política a través de Internet y, en caso afirmativo, cómo se produce dicho proceso y qué consecuencias tiene.

El presente estudio tenía como finalidad indagar sobre la socialización política de los jóvenes a través de la Red, las habilidades con las que cuentan para ello y la participación política que realizan en línea y fuera de línea. De este modo, se pretendía comprobar si los jóvenes inician su contacto con la política mediante las nuevas tecnologías, para lo cual deben contar previamente con las habilidades digitales necesarias. Asimismo, la finalidad de esta aportación también iba encaminada a observar si ese aprendizaje en línea propicia o no implicación en formas de participación política online y offline. Con este propósito se realizó una encuesta a los jóvenes universitarios de México, España y Chile, alcanzado un tamaño de muestra en cada uno de dichos países de 1.239, de 627 y de 1.058 encuestados respectivamente. La elección de la población de estudio se justifica porque los jóvenes universitarios cuentan con la mayoría edad, lo que supone que disfrutan del ejercicio pleno de sus derechos políticos, como el del voto. El diseño de la encuesta estuvo orientado a obtener información sobre dos bloques de cuestiones. En primer lugar, sobre el consumo de medios, como indicador de la socialización política, y sobre la confianza en dichos medios, como reflejo de las habilidades de las que disponen los jóvenes. Y, en segundo lugar, sobre la participación política tanto en línea como fuera de línea.

Los resultados obtenidos muestran que los jóvenes mexicanos, españoles y chilenos consumen principalmente medios de comunicación digitales, de modo que obtienen la información política a través de los mismos. Ello queda demostrado al ser las redes sociales, seguidas de la prensa digital, las fuentes a las que más se exponen. Por tanto, los jóvenes se introducen en los asuntos públicos a través de las nuevas tecnologías, ya que a través de ellas conocen lo que sucede en la realidad política. Esto, unido a su escasa exposición a los medios de comunicación audiovisuales y escritos, confirmaría que los medios digitales cumplirían una función de socialización política para estos universitarios iberoamericanos. No obstante, este aprendizaje político que se produce en el seno de la red no está exento de capacidad crítica por parte de los jóvenes. Así, estos son capaces de distinguir la credibilidad y la confianza que merecen los medios, tanto convencionales como digitales. Ello es especialmente importante en el ámbito de la tecnología, en el cual la infinidad de información disponible hace necesario ser capaz de discriminar ante la existencia de numeroso contenido de carácter no fiable. En este sentido, la mayor parte de los universitarios de estos países no tienen confianza en los medios digitales que utilizan, lo cual supondría que cuentan con una importante habilidad para conformar su propio criterio, algo necesario para ejercer como ciudadanos. Esta socialización cívica que los jóvenes experimentan en la Red parece configurarse como un paso previo para aprender a participar políticamente de forma digital. De esta manera, una parte significativa de los universitarios españoles toma parte en acciones de ciberactivismo. No obstante, las formas de participación política online que suelen realizar tienen más un carácter pasivo al estar relacionadas con la lectura o el visionado de contenido político. A pesar de ello, también toman partido de formas de participación más activas, como la búsqueda de información política.

Frente al activismo político que los jóvenes mexicanos, españoles y chilenos protagonizan en las redes digitales, se sitúa su menor implicación en acciones de participación política fuera de línea. Solo la participación electoral, es decir, votar, es mayoritaria entre los universitarios de los países analizados, a excepción de México. No obstante, y, como se señaló previamente, no deben considerarse como totalmente diferentes ambos tipos de participación, la online y la offline. En este sentido, el consumo de información política que los jóvenes hacen en Internet, así como las acciones de activismo que realizan en línea, pueden condicionar una participación offline posterior como el voto. A pesar de ello, es necesario seguir profundizando y ampliar los análisis realizados para confirmar los resultados obtenidos y ahondar en el aprendizaje que sobre política adquieren los jóvenes en Internet.

References

- AguileraO., . 2012.Repertorios y ciclos de movilización juvenil en Chile (2000-2012)Notas y Debates de la Actualidad 27(57):101-108

- AlbrechtS., . 2006.voice is heard in online deliberation? A study of participation and representation in political debates on the internet&author=Albrecht&publication_year= Whose voice is heard in online deliberation? A study of participation and representation in political debates on the internet.Information, Communication & Society 19(1):62-82

- BosettaM., DotceacA., TrenzH.J., . 2018.participation on Facebook during Brexit does user engagement on media pages stimulate engagement with campaigns?&author=Bosetta&publication_year= Political participation on Facebook during Brexit does user engagement on media pages stimulate engagement with campaigns?Journal of Language and Politics 17(2):173-194

- CasteltrioneI., . 2016.and political participation: Virtuous circle and participation intermediaries&author=Casteltrione&publication_year= Facebook and political participation: Virtuous circle and participation intermediaries.Interactions: Studies in Communication & Culture 7(2):177-196

- CroviD., . 2013.Jóvenes al fin, contraste de opiniones entre estudiantes y trabajadores. In: CroviD., GarayL.M., LópezR., PortilloM., eds. y apropiación tecnológica. La vida como hipertexto&author=Crovi&publication_year= Jóvenes y apropiación tecnológica. La vida como hipertexto.183-196

- DaltonR.J., . 2004.Democratic challenges, democratic choices. The erosion of political support in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- DarioDe-la-Garza,, DarioBarredo,, . 2017.Democracia digital en México: Un estudio sobre la participación de los jóvenes usuarios mexicanos durante las elecciones legislativas las elecciones legislativas federales de 2015.Index Comunicación 7(1):95-114

- DiMaggioP., EHargittai, . 2001.From the ‘digital divide’ to ‘digital inequality’: Studying internet use as penetration increases. Working Paper nº 15. Center for Arts and Cultural Policy Studies, Woodrow Wilson School. Princeton: Princeton University.

- FernándezA., . 2015.que influyen en la confianza en los medios: explorando la asociación entre el consumo de medios y las noticias sobre el Movimiento 15M&author=Fernández&publication_year= Factores que influyen en la confianza en los medios: explorando la asociación entre el consumo de medios y las noticias sobre el Movimiento 15M.Hipertext 13:1-16

- GarcíaM.C., MercedesD.H., FernándezC., . 2014.comprometidos en la Red: El papel de las redes sociales en la participación social activa. [Engaged youth in Internet. The role of social networks in social active participation&author=García&publication_year= Jóvenes comprometidos en la Red: El papel de las redes sociales en la participación social activa. [Engaged youth in Internet. The role of social networks in social active participation]]Comunicar 43:35-43

- García-PeñalvoF.J., . 2016.socialización como proceso clave en la gestión del conocimiento&author=García-Peñalvo&publication_year= La socialización como proceso clave en la gestión del conocimiento.Education in the Knowledge Society 17(2):7-14

- H.Gil-de-Zúñiga,, A.Veenstra,, E.Vraga,, D.Shah,, . 2010.democracy: Reimagining pathways to political participation&author=H.&publication_year= Digital democracy: Reimagining pathways to political participation.Journal of Information Technology & Politics 7(1):36-51

- GómezS., TejeraH., AguilarJ., . 2013. , ed. cultura política de los jóvenes en México&author=&publication_year= La cultura política de los jóvenes en México. México: Colegio de México.

- GrossmanL.K., . 1995.The electronic republic: Reshaping democracy in the information age. New York: Viking.

- GualdaE., BorreroJ.D., CañadaJ.C., . 2015.‘Spanish Revolution’ en Twitter (2): Redes de hashtags y actores individuales y colectivos respecto a los desahucios en España&author=Gualda&publication_year= La ‘Spanish Revolution’ en Twitter (2): Redes de hashtags y actores individuales y colectivos respecto a los desahucios en España.Redes 26(1):1-22

- HargittaiE., . 2002.digital divide: Differences in people’s online skills&author=Hargittai&publication_year= Second-level digital divide: Differences in people’s online skills.First Monday 7(4):1-20

- HaroC., SampedroV., . 2011.Activismo político en Red: Del movimiento por la vivienda digna al 15M.Teknokultura 8(2):167-185

- E.Hernández,, M.C.Robles,, J.B.Martínez,, . 2013.interactivos y culturas cívicas: Sentido educativo, mediático y político del 15M. [Interactive youth and civic cultures: The educational, mediatic and political meaning of the 15M&author=E.&publication_year= Jóvenes interactivos y culturas cívicas: Sentido educativo, mediático y político del 15M. [Interactive youth and civic cultures: The educational, mediatic and political meaning of the 15M]]Comunicar 40:59-67

- ManríquezM.T., AugustiE.C., . 2015.Participación multi-asociativa de los jóvenes y espacio público: Evidencias desde el caso chileno.Revista del CLAD Reforma y Democracia 62:167-192

- MardonesR., . 2014.encrucijada de la democracia chilena: una aproximación conceptual a la desafección política&author=Mardones&publication_year= La encrucijada de la democracia chilena: una aproximación conceptual a la desafección política.Papel Político 19(1):39-59

- MascheroniG., . 2017.A practice-based approach to online participation: Young people’s participatory habitus as a source of diverse online engagement.International Journal of Communication 11:4630-4651

- MinS.J., . 2010.the digital divide to the democratic divide: Internet skills, political interest, and the second-level digital divide in political internet use&author=Min&publication_year= From the digital divide to the democratic divide: Internet skills, political interest, and the second-level digital divide in political internet use.Journal of Information Technology & Politics 7(1):22-35

- MinS.J., WohnD., . 2018.the news that you don't like: Cross-cutting exposure and political participation in the age of social media&author=Min&publication_year= All the news that you don't like: Cross-cutting exposure and political participation in the age of social media.Computers in Human Behavior 83:24-31

- MoralesH., . 2002.de la movilización juvenil en México. Notas para su análisis&author=Morales&publication_year= Visibilidad de la movilización juvenil en México. Notas para su análisis.Última 17:11-39

- NorrisP., . 2001.Digital divide: Civil engagement, information poverty, and the internet worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- OserJ., HoogheM., MarienS., . 2013.online participation distinct from offline participation? A latent class analysis of participation types and their stratification&author=Oser&publication_year= Is online participation distinct from offline participation? A latent class analysis of participation types and their stratification.Political Research Quarterly 66(1):91-101

- PasquinoG., BartoliniS., CottaM., . 1996. , ed. de Ciencia Política&author=&publication_year= Manual de Ciencia Política. Madrid: Alianza.

- PortilloM., . 2015.Construcción de ciudadanía a partir del relato de jóvenes participantes del# YoSoy132.Global Media Journal México 12:1-18

- QuiñónezL.C., . 2014.y elecciones 2012: Viejos y nuevos desafíos para la comunicación política en México&author=Quiñónez&publication_year= Medios y elecciones 2012: Viejos y nuevos desafíos para la comunicación política en México.Nóesis 23(45):24-48

- RecueroF., . 2016. , ed. participación política online: Un análisis de sus condicionantes. Actas del XV Congreso Nacional de Educación Comparada: Ciudadanía mundial y educación para el desarrollo. Una mirada internacional&author=&publication_year= La participación política online: Un análisis de sus condicionantes. Actas del XV Congreso Nacional de Educación Comparada: Ciudadanía mundial y educación para el desarrollo. Una mirada internacional. Sevilla: Universidad Pablo de Olavide.

- ResinaJ., . 2010.Ciberpolítica, redes sociales y nuevas movilizaciones en España: el impacto digital en los procesos de deliberación y participación ciudadana.Mediaciones Sociales 7(2):143-164