Abstract

Prevailing city design in many countries has created sedentary societies that depend on automobile use. Consequently, architects, urban designers, and land planners have developed new urban design theories, which have been incorporated into the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design for Neighborhood Development (LEED-ND) certification system. The LEED-ND includes design elements that improve human well-being by facilitating walking and biking, a concept known as walkability. Despite these positive developments, relevant research findings from other fields of study have not been fully integrated into the LEED-ND. According to Zuniga-Teran (2015), relevant walkability research findings from multiple disciplines were organized into a walkability framework (WF) that organizes design elements related to physical activity into nine categories, namely, connectivity, land use, density, traffic safety, surveillance, parking, experience, greenspace, and community. In this study, we analyze walkability in the LEED-ND through the lens of the nine WF categories. Through quantitative and qualitative analyses, we identify gaps and strengths in the LEED-ND and propose potential enhancements to this certification system that reflects what is known about enhancing walkability more comprehensively through neighborhood design analysis. This work seeks to facilitate the translation of research into practice, which can ultimately lead to more active and healthier societies.

Keywords

Walkability ; LEED-ND ; Physical activity ; Urban design ; Well-being ; Built environment

1. Introduction

Architects, urban designers, and land planners have recognized that city design can contribute to the challenges faced by urban societies, including the trend toward urban sprawl and increased sedentariness (Frank et al., 2003 ). The U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) created the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design for Neighborhood Development (LEED-ND) rating system to certify sustainable development and provide design guidelines that can help address urban society challenges (http://www.usgbc.org/articles/getting-know-leed-neighborhood-development ). This study builds on a previous walkability study, which focused on the degree to which the built environment promoted physical activity as part of daily routine. In this study, we analyze walkability in the LEED-ND using the walkability framework (WF). We conduct quantitative and qualitative analyses of how walkability is captured in the LEED-ND and propose a walkability-enhanced version of the rating system.

1.1. The LEED initiative and LEED-ND

The USGBC is a nonprofit organization that acts as an independent entity. The USGBC verifies that sustainable practices are adopted in the design, construction, operation, and maintenance of buildings in the U.S. and internationally through its certification system known as LEED (http://www.usgbc.org/leed ). LEED certification has grown to include building design and construction, interior design and construction, building operations and maintenance, neighborhood development, and homes. The certification system for neighborhood development was launched in 2009, and hundreds of certified neighborhoods currently exist worldwide (http://www.usgbc.org/projects ).

All LEED certifications are based on a simple point-based rating system to ensure practicality. The rating system includes mandatory prerequisites that projects must comply with. Satisfying these prerequisites makes projects eligible to apply for certification, but points are not earned from prerequisites (http://www.usgbc.org/leed ). In addition to the prerequisites, optional credits are available that may be pursued for a given project. Each credit in the LEED has an associated number of points that are awarded to a project if it complies with the credit. The total number of points earned by a project determines its LEED certification level: certification (40–49 points), silver (50–59 points), gold (60–69 points), and platinum (80 points and above). A total of 110 optional points are available.

The LEED-ND places significant emphasis on neighborhood design. Thus, the site selection, design, and construction phases can ensure that buildings and supporting infrastructure are linked, supporting the relationships among neighborhoods, landscapes, and larger local and regional contexts (Sharifi and Murayama, 2013 ). Moreover, rather than relying solely on regulatory requirements for sustainable neighborhood development, the LEED-ND is intended to be a voluntary, market-driven approach with the aim of being comprehensive but readily implementable (Garde, 2009 ).

The LEED-ND is divided into five sections: (1) smart location and linkage (SLL), (2) neighborhood pattern and design (NPD), (3) green infrastructure and building (GIB), and (4) innovation and design process, with additional points that may be earned for extra significance in the local area under the optional section (5) “Regional Priority” (http://www.usgbc.org/resources/leed-v4-neighborhood-development-checklist ). Some prerequisites and credits offer several options from which the developer may choose. Other prerequisites are divided into cases, and developers must select the most appropriate case for their project. Finally, some prerequisites include several parts (e.g., a, b, and c), and the developers must comply with all of them. Some credits also include several items (e.g., a, b, and c), and the number of points earned depends on the number of items that the project complied with.

The LEED-ND integrates the sustainable development theories from new urbanism thinking and the smart growth policies that followed, as well as green building certification principles (Jackson, 2003 ). The LEED-ND attempts to address all of the key principles of sustainable neighborhood development, one of which is to provide compact development and integrated sustainable mobility, effectively reducing the need for automobile travel (Luederitz et al., 2013 ). By providing points for design elements that promote pedestrian activity, the LEED-ND indirectly encourages physical activity through enhanced walkability in neighborhoods (Lewin, 2012 ). Research has shown that LEED-ND projects are associated with increased physical activity in children (Stevens and Brown, 2011 ).

The LEED-ND appears to have been accepted by developers. Although concerns do exist within the development and building community, feedback suggests that the goal of making it practical and flexible has been met, based on surveys of developers (Garde, 2009 ; Knack, 2010 ; Sharifi and Murayama, 2014 ). Moreover, the LEED-ND has been adopted by several authorities to provide guidelines for urban development that support slow and incremental lifestyle changes that reduce demands on the environment (Lewin, 2012 ).

1.2. LEED-ND and walkability

The manner in which the LEED-ND addresses walkability is viewed as one of the strengths of the rating system; however, this strength may come at the expense of other categories. Sharifi and Murayama (2014) compared the LEED-ND with conceptually similar neighborhood sustainability assessment tools used in the United Kingdom and Japan and determined that LEED-ND addressed walkability well and that walkability played a pivotal role in receiving LEED-ND certification when applied by developers. However, the low cost of implementing the walkability criterion has a relatively high weight in the LEED-ND. The concern is that other important categories that have lower weights and/or involve greater costs are less frequently implemented in projects that receive certification (Garde, 2009 ; Knack, 2010 ; Sharifi and Murayama, 2014 ).

Encouraging results have been obtained in LEED-ND walkability research; LEED-ND-certified neighborhoods are correlated with increased physical activity. Stevens and Brown (2011) observed higher levels of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) in LEED-ND neighborhoods than that in other communities. Gallimore et al. (2011) compared a LEED-ND-certified neighborhood and an uncertified suburban neighborhood in terms of walking routes to school and determined that the LEED-ND-certified neighborhood provided better walking conditions for children. However, this finding does not mean that children would actually walk to school. Napier et al. (2011) noted that demographic and municipal policy trends in the U.S. were leading to fewer and larger schools. This finding indicates that fewer children will realistically be able to walk to school, even if the LEED-ND calls for safer routes, because they will likely live far from the school.

Since the advent of the LEED-ND, considerable research has been conducted on the effects of the built environment on walkability and physical activity in research domains outside urban design and architecture, including physical activity, thermal comfort, land planning and transportation, health and the built environment, and greenspace. The LEED-ND is considerably helpful to architects, land planners, and urban designers who wish to design sustainable neighborhoods because it provides specific design guidelines (Knack, 2010 ). However, this certification has not integrated the findings on walkability from other research domains. This study aims to address this gap and to integrate the findings from other research domains into the LEED-ND in a manner that adheres to the strengths of the certification system (relatively easy to implement and flexible), such that the suggested enhancements can be considered not only for their scientific value but also for their applicability to the current LEED-ND structure.

1.3. Walkability framework

The first stage of this research involved synthesizing findings on neighborhood design elements that are related to walkability from multiple research domains (Zuniga-Teran, 2015 ). This synthesis also treated the neighborhood design elements found in the LEED-ND as a representative of the architecture and urban design domain. As a result of this synthesis, we developed a conceptual framework, i.e., the WF, that comprises nine categories: (1) connectivity, (2) land use, (3) density, (4) traffic safety, (5) surveillance, (6) parking, (7) experience, (8) greenspace, and (9) community. Each category describes a set of neighborhood design elements that affect physical activity and human health (Table 1 ). Some neighborhood design elements are interrelated, such that they can be considered in several categories. For example, a strip of vegetation along the sidewalks provides safety from traffic (part of the traffic safety category) and reduces fumes and noise (part of the experience category).

| WF categories | Subcategories | Main aspect of the category |

|---|---|---|

| Connectivity | Provide a street network that gives multiple, direct, and short routes. | |

| Land use |

|

Locate a variety of small businesses within a 10 min walk (1/2 mile) from homes. |

| Density | Require a high residential and retail density. High-rise towers must consider the pedestrian scale at street level to avoid oppression. | |

| Traffic safety | Slow the traffic and give pedestrians and bikers safe places to travel. In addition, provide safe and comfortable bus stops and a frequent and reliable bus service. | |

| Surveillance | Design buildings such that pedestrians traveling on the street can be seen from the surrounding homes and businesses. | |

| Parking | Decrease parking availability and locate parking away from streets. | |

| Experience |

|

Provide a pleasant walking and biking experience by addressing streetscape proportions, aesthetics, wayfinding considerations, thermal comfort level, slope, presence of fumes, and presence of dogs/wildlife. |

| Greenspace | Include a variety of greenspace in size and proximity with easy access and vegetation throughout the neighborhood. | |

| Community | Provide spaces for social interactions among neighbors and encourage the participation of neighbors in the decision-making processes of the community. |

Some categories include multiple neighborhood design elements that can clearly be grouped into subcategories. The traffic safety category was further divided into four subcategories, namely, pedestrians, bicycles, transit systems, and traffic-calming treatments. Similarly, the experience category was divided into seven subcategories, namely, streetscape proportions, aesthetics, thermal comfort level, wayfinding considerations, slope, presence of fumes/noise, and presence of dogs.

Current research shows that all walkability categories are related to physical activity. Woldeamanuel and Kent (2016) reported that the availability and quality of sidewalks (traffic safety category) and the connectivity of the street network (connectivity category) were significantly associated with people accessing and using public transportation in San Fernando Valley, Los Angeles, U.S.A. Similarly, Stockton et al. (2016) developed a walkability model for London, where they measured connectivity, residential density, and land use mix, and observed a radial decay in walkability. People who lived in the center of London, which scored higher in walkability, were more likely to walk more than 6 h/week than those who lived in the peripheries of the city, which scored lower in walkability. In an effort to examine how the relationship between built environment and physical activity varied in low-income and middle-income countries, Adlakha et al. (2016) adopted the Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale questionnaire in India. This tool was developed by Cerin et al. (2006) and measures connectivity, density, traffic safety, safety from crime (surveillance category), land use mix, aesthetics (experience category), parking, and infrastructure for walking and bicycling. According to Adlakha et al. (2016) , this tool measured walkability in India acceptably and reliably.

With regard to greenspace category, Ward et al. (2016) reported that children who were exposed to greenspace in Auckland, New Zealand were positively related to MVPA and emotional well-being. Similarly, Veitch et al. (2016) observed that Australian women who lived close to parks were more likely to meet physical activity recommendations and less likely to be obese than women who do not live close to parks. In addition to greenspace, Soltero et al. (2015) examined the relationship between physical activity and its resources (i.e., parks and plazas) in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico. Soltero (2015) determined that plazas (community category) attracted more users than parks, particularly women, and their discussion suggested that the quality of amenities and incivilities were determinants of their use.

2. Methods

In applying the WF to the LEED-ND, identifying the prerequisites and credits in the LEED-ND that are related to walkability and human health and determining the percentage of points in the LEED-ND that are related to walkability are necessary. Then, we compared the LEED-ND with the design elements found in each of the nine WF categories. We added a column to the tables from the synthesis study (Zuniga-Teran, 2015 ) and identified which prerequisites and credits from the LEED-ND were related to the design elements for each category. This analysis identified walkability gaps and strengths in the LEED-ND (Table 4 , Table 5 , Table 6 , Table 8 , Table 9 , Table 10 , Table 11 ; Table 12 in the Appendix ).

Then, we determined the walkability score for LEED-ND for each category by calculating the percentage of neighborhood design elements included in the LEED-ND from the total number of neighborhood design elements in the WF for each category (Tables 4–12 in the Appendix ). Calculating these percentages allowed us to compare how well the LEED-ND supported walkability between categories.

The synthesis of findings from the first stage of this research yielded a summary table of the main aspects of each category (Table 1 ). This summary table was used to analyze LEED-ND qualitatively.

We scored the LEED-ND by comparing how the certification system addressed the main focus of each category in two ways: (i) by looking at the percentage of neighborhood design elements included in the LEED-ND and (ii) by evaluating how well the main focus of the category (Table 1 ) is enforced in the prerequisites. The first part of this analysis was based on the academic and professional experience of the team of coauthors. The team included two architects, who are LEED-accredited professionals with experience in the design of sustainable and walkable neighborhoods, and academic researchers with interdisciplinary backgrounds, including architecture, physical activity, landscape architecture, and spatial analysis. As a team, we established 50% as the threshold for neighborhood design elements to be included in the LEED-ND. The second part of the scoring was an evidence-based binary variable (yes/no). The variable examined whether the main focus of the categories was included in the LEED-ND as prerequisites for certification. This assessment included the review of all LEED-ND prerequisites and their relationship with walkability categories.

We assigned three scores, i.e., strong, moderate, and weak. Strong scores were given to the categories in which the main focus (as described in Table 1 ) was addressed in a prerequisite for certification and in which the LEED-ND includes 50% or more of the neighborhood design elements from the WF (Zuniga-Teran, 2015 ). Moderate scores were given to the categories in which the LEED-ND did not address the main focus of the category in a prerequisite, but in which more than 50% of the neighborhood design elements identified in the WF was included. Finally, weak scores were given to the categories in which the LEED-ND did not address the main focus of the category in a prerequisite and in which less than 50% of the neighborhood design elements from the WF was included.

On the basis of the outcomes of this analysis, we developed a walkability-enhanced LEED-ND that integrated the main aspects of the categories included in the WF. We called this proposed certification system the LEED-ND walkability plus (LEED-NDW+).

3. Results

In this study, we determined that walkability was addressed mainly in the first and second LEED-ND sections (i.e., SLL and NPD), with some credits appearing in the GIB section. The tally across all categories revealed that the LEED-ND in its current form considered walkability in 78 of the available 110 points (70.9%).

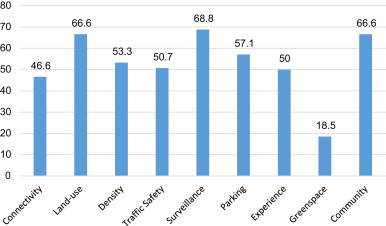

LEED-ND analysis through the lens of the nine categories of the WF provided a measure of how well walkability is represented in the LEED-ND in each category (Fig. 1 ; Table 2 )..

|

|

|

Fig. 1. Percent of design elements included in the LEED-ND. Percent of design elements related to walkability found in the literature that is addressed in the LEED-ND, according to the nine WF categories (see Tables 4-8 in Appendix). |

| WF categories | WF subcategories | Percent of design elements in the LEED-ND | Number of design elements required by the LEED-ND | Correspondence with the LEED-ND prerequisites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connectivity | 46.6 | 6 | Strong | |

| Land use | 66.6 | 8a | Moderate | |

| Density | 53.3 | 6 | Strong | |

| Traffic safety | 50.7 | 5 | Moderate | |

| Pedestrians | (61.5) | (3) | (Strong) | |

| Bicycles | (52.6) | (0) | (Moderate) | |

| Transit systems | (66.7) | (2)a | (Moderate) | |

| Traffic-calming treatments | (22.2) | (0) | (Weak) | |

| Surveillance | 68.8 | 2 | Strong | |

| Parking | 57.1 | 0 | Moderate | |

| Experience | 50.0 | 3 | Moderate | |

| Streetscape | (50) | (1) | (Strong) | |

| Aesthetics | (46.2) | (0) | (Weak) | |

| Thermal comfort | (88.8) | (2) | (Strong) | |

| Wayfinding | (0) | (0) | (Weak) | |

| Slope | (50) | (0) | (Moderate) | |

| Fumes/noise | (0) | (0) | (Weak) | |

| Dogs | (0) | (0) | (Weak) | |

| Greenspace | 18.5 | 0 | Weak | |

| Community | 66.6 | 0 | Moderate | |

a. Prerequisites that offer several options to achieve compliance, but not all options are related to the category.

The results show that the LEED-ND received a strong score in the density category, which includes more than 50% of the neighborhood design elements (53.3%), and some of these elements are required. For example, the NPDp2—Compact Development offers two options to achieve compliance: Option 1—Projects in Transit Corridors (locate the project within walking distance from a transit service and use a density of seven units per acre or more for those areas not within walking distance from a transit service) and Option 2—All Other Projects (must include a minimum density of seven units per acre). Both options are related to density. Therefore, an LEED-ND-certified neighborhood would necessarily address the main focus of the density category.

Similar to density, surveillance also received a strong score. This category includes more than 50% of the neighborhood design elements (68.8%), and some of these elements are required. For example, NPDp1—Walkable Streets have four sections (a–d) that are not optional; thus, the developer must comply with all of them. Surveillance is represented in section “a” (front façades of 90% of the buildings face a public street) and section “b” (a minimum building height-to-street width ratio of 1:3 for 15% of the street frontage, which ensures a short building setback and locates people inside the buildings who are close to the street).

Connectivity also received a strong score in this analysis. Although the percent of neighborhood design elements included in the LEED-ND is slightly less than 50% (46.6%), several prerequisites address this category, which ensures that some degree of connectivity is guaranteed. For example, NPDp3—Connected and Open Community offers two options to achieve compliance: Option 1—Projects with Internal Streets (projects must have at least 140 intersections per square mile) and Option 2—Projects without Internal Streets (adjacent connectivity is at least 90 intersections per square mile). Both options are related to connectivity. In addition to this prerequisite, connectivity is also required within options for other prerequisites ( Table 4 in the Appendix ). We gave this category a strong score because the main focus of the category was guaranteed to be addressed in an LEED-ND project.

The overall averaged result for the traffic safety category (average of the percentages of the four subcategories and sum of prerequisites) indicates that this category can have a strong rating. The category includes more than 50% of the neighborhood design elements (50.7%), and some of these elements are required. In addition, the pedestrian subcategory received a strong score. However, we gave this category an overall moderate score because the remaining subcategories received moderate or weak scores. For example, the bicycle subcategory received a moderate score because, although more than 50% of the neighborhood design elements (52.6%) was included in the LEED-ND, no prerequisite was required. Similarly, the transit system subcategory received a moderate score because the prerequisites offered several options to achieve compliance and not all options addressed this subcategory. Thus, a LEED-ND-certified neighborhood that completely ignores bicyclists and transit systems can be built. Finally, the traffic-calming treatment subcategory received a weak score because it included less than 50% of the neighborhood design elements (22.2%), and none of these elements are required. This finding indicates that overall traffic safety is not ensured in a LEED-ND neighborhood. We gave this category an overall moderate score because it has room for improvement.

The evaluation of the experience category was similar to the traffic safety evaluation described previously. The overall percentage and requirements would suggest a strong score; however, we obtained several weak and moderate scores. Therefore, the overall score of the experience category was moderate.

Land use was given a moderate score because, although the LEED-ND included more than 50% of the neighborhood design elements for this category (66.6%), the prerequisites did not ensure that this aspect of walkability was represented in the final product. For example, SLLp1—Smart Location offers four options to achieve compliance, and Option 4—Nearby Neighborhood Assets refers to land use (includes the residential component and locates the project close to services). However, a developer may choose one of the other three options that are unrelated to land use (i.e., Option 1—Infill Site , Option 2—Adjacent Site with Connectivity , and Option 3—Transit Corridor or Route with Adequate Transit Service ). Thus, we gave this category a moderate score.

Finally, greenspace received a weak score because few neighborhood design elements are included in this category (18.5%), and none of these elements are required. Greenspace does not have specific prerequisites or credit points. For example, the LEED-ND awards up to four points for including services close to homes in NPDc3—Mixed-use Neighborhood Centers , where a developer can choose from a list of 27 services (or diverse uses) to include in the neighborhood within walking distance from homes. In this list, a public park is an option. However, developers may choose one of the other 26 services on the list. Similarly, NPDc9—Access to Civic and Public Spaces offers one credit point for an open space and includes a park as an option, which can be substituted by a square, paseo, or plaza (open spaces without vegetation). This credit does not specifically ensure that a greenspace will be included. In addition, NPDc10—Access to Recreation Facilities offers one credit point for including a recreation facility, which can be indoor or outdoor, within walking distance from homes. In summary, greenspace does not have direct credit points or prerequisites in the LEED-ND.

4. Discussion and conclusion

This study determined that walkability was widely considered in the LEED-ND; 70.9% of the credit points available were related to walkability. However, when the LEED-ND treatment of walkability was compared with the WF, important gaps and strengths became evident. Connectivity, density, and surveillance were clear strengths of the LEED-ND because the certification system addressed the main aspects of these categories as prerequisites for certification and offered additional credits ( Table 2 ).

However, we observed important gaps in land use, traffic safety, parking, experience , and community . Although many neighborhood design elements related to these categories were included in the LEED-ND, no requirement was set to ensure that these aspects of walkability were included in a LEED-ND-certified neighborhood.

The most significant gap identified in the LEED-ND involved the greenspace category, which received a weak score. We considered all of the empirical evidence of the benefits of the presence of greenspace in cities to well-being ( Jackson, 2003 ; Chu et al ., 2004 ; Herrick, 2009 ; Clark et al ., 2010 ; Sandifer et al ., 2015 ), including its role as a catalyst for physical activity (Herrick, 2009 ). We determined that this aspect of the LEED-ND, along with the other categories that received moderate scores, urgently needs to be addressed. The LEED-ND is a practical tool used by developers, urban designers, and architects who wish to build sustainable and walkable neighborhoods. Thus, we decided to propose a modified version of the LEED-ND, called the LEED-NDW+(Table 3 ), to address the gaps identified in this study.

| Walkability category | Changes to the LEED-ND | Description | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connectivity | NPDc1—Walkable streets | Include two points for a grid street network in at least 50% of the neighborhood. | |||

| Land use | NPDp4—Mixed-use developments | Include at least 30% of the building footprint as mixed use, where the ground floor is used for retail, including corners. | |||

| NPDc15—Child care facilities | Include a child care facility within 1/4 mile (400 m) of homes. | ||||

| Density | NPDp9—Pedestrian scale | Push away high-rise towers (more than five stories high) from the street line and maintain a four to six stories height at the street level. | |||

| Traffic safety | Pedestrians | No change | Subcategory received a strong score in the LEED-ND. | ||

| Bicycles | NPDp5—Pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure | Provide sidewalks and bike lanes throughout the neighborhood, buffered from the road by on-street parking and a vegetated strip of at least 90 cm (approx. 3 ft). | |||

| Transit | Eliminate Option 2 in NPDp2 - Compact Development | By having Option 1 as the only option to comply with this pre-requisite, access to transit systems is ensured. | |||

| Traffic-calming treatments | NPDc16—Traffic-calming treatments | Include any five traffic-calming treatments for one point and seven traffic-calming treatments for two points (see the list in Table 7.4 in the Appendix ). | |||

| Surveillance | NPDc1—Walkable streets | Include front porches, balconies, and outdoor cafes. | |||

| GIBp5—Lighting | Provide lighting along the streets that follow light pollution guidelines. | ||||

| Parking | NPDp10—Parking location | Locate parking in the rear of buildings or in basements, but away from the front of the buildings (on-street parking is encouraged). | |||

| Experience | Streetscape | No change | Subcategory received a strong score in the LEED-ND. | ||

| Aesthetics | NPDp8—Tree-lined streets | Provide trees along all of the streets of the neighborhood on both sides of the streets at intervals of 12 m or less. | |||

| NPDc1—Walkable streets | Include street furniture (e.g., benches and waste bins). | ||||

| Thermal comfort | NPDc1—Walkable streets | Include water bodies (fountains).Note: NPDp8- Tree-lined streets (above) is also related to thermal comfort. | |||

| Wayfinding | NPDc17—Street design | Include signage, awnings, marquees, balconies, arcades, and galleries along the streets. An extra point can be earned for a landmark. | |||

| Slope | No change | Site specific. | |||

| Fumes/noise | GIBc16—Solid waste management | Locate waste containers away from the street. | |||

| NPDc13—Vegetated streetscapes | Provide a strip of vegetation of at least 1.5 m wide along the streets that buffers the sidewalks and bike lanes from the road. Vegetation must include grassy areas of at least 1.4 m2 every 30 m and include dog infrastructure (waste bags and waste containers), following green infrastructure design described in GIBc8. | ||||

| Dogs | |||||

| Greenspace | NPDp7—Greenspace | Include a small greenspace (2 ha or 4.9 acres) within walking distance of homes (1/4 mile or 400 m), and encourage small shops on its boundaries, including food trucks. | |||

| GIBc17—Green play space | Provide a grassy play space (0.40 ha or 1 acre) safeguarded from traffic with dwelling units overlooking the space within 100 m from homes. | ||||

| Community | NPDp8—Access to civic and public spaces | Provide a civic space (plaza) located in a central location also surrounded by small retail. | |||

Although connectivity received a strong score in this analysis, we decided to make a slight change to NPDc1—Walkable Streets . Considering that the WF consistently shows the grid street network as more walkable, we decided to add an optional credit point for this category that includes a grid street network for at least 50% of the land area.

For land use category, which received a moderate score in this study because of the lack of enforced prerequisites, we added the prerequisite NPDp4—Mixed-use Developments . This prerequisite ensures that a LEED-ND-certified neighborhood contains services (e.g., shops and restaurants) close to homes that provide destinations for walking. NPDc15—Child Care Facilities is also added because, similar to schools, this service is used daily by young families.

Density received a strong score in this study; however, the oppressive feeling of tall buildings has been well documented ( Jacobs, 1961 ; Montgomery, 2013 ; Gifford, 2014 ). Therefore, we decided to include the prerequisite NPDp9—Pedestrian Scale , which ensures that high-rise towers (more than five stories high) are pushed away from the street line, while maintaining the four-story height at the street level.

The traffic safety category showed gaps in the bicycle, transit, and traffic-calming treatment subcategories. Therefore, we included the prerequisite NPDp5—Pedestrian and Bicycle Infrastructure to ensure that bike lanes and sidewalks protected from traffic are present throughout the neighborhood. We also eliminated Option 2 from the NPDp2 - Compact Development, which is not related to transit systems. In addition, we added the credit NPDc16—Traffic-calming Treatments ; developers may earn up to two points for including several of the traffic-calming treatments listed in Table 7.4 in the Appendix .

Although the surveillance category received a strong score in this analysis, the LEED-ND could be further strengthened by incorporating additional design elements from WF. Thus, design elements related to surveillance were added to NPDc1 —Walkable Streets , which now included front porches, balconies, and outdoor cafes. These types of design elements facilitate observation of the streets, which increases surveillance. In addition, we decided to move GIBc17 —Light Pollution Reduction to a prerequisite position that we called GIBp5 —Lighting because lighting is essential for surveillance at night. This prerequisite follows the same light pollution guidelines from GIBc17, but it now ensures that all of the streets of a LEED-ND neighborhood are equipped with lighting fixtures.

Parking received a moderate score in this study because this category has no prerequisite. Therefore, we added the prerequisite NPDp10 —Parking Location , which requires parking to be located in the rear of buildings or in basements, and thus away from sidewalks. On-street parking is recommended because it provides safety to pedestrians from traffic.

Even though the streetscape and thermal comfort subcategories of the experience category received strong scores, we still proposed minor edits to these subcategories. We added the option to include a fountain or water body in NPDc1—Walkable Streets , which addresses thermal comfort. For the aesthetics subcategory, we moved NPDc14 —Tree-lined and Shaded Streets from a credit to a prerequisite position (NPDp6 —Tree-lined Streets ) to ensure that the streets of a LEED-ND-certified neighborhood contains trees. In addition, we included street furniture to NPDc1 —Walkable Streets as an additional item to choose from. For the wayfinding subcategory, we included a new credit, NPDc17 —Street Design , which offers a credit point for signage, awnings, marquees, balconies, arcades, and galleries along the streets. An additional point can be earned in this credit for a landmark. For slope, we did not make any changes because this subcategory is site specific, and the negative aspects of slopes are already addressed in SLLc6 —Steep Slope Protection . With regard to fumes/noise, we added a specification to the existing GIBc16 —Solid Waste Management to locate waste containers away from the streets, which would remove garbage fumes from the space used by pedestrians and cyclists. In addition, we created a new credit, NPDc14 —Vegetated Streetscape , by moving the former NPDc14 —Tree-lined and Shaded Streets to a prerequisite position (described previously). This new credit offers a point for providing a strip of vegetation along the sidewalks that buffers pedestrians and cyclists from the road. This credit enhances the experience of walking (in addition to making streets safer, which is part of the traffic safety category) because vegetation is known to remove pollutants from the air. Finally, for dogs, we included grassy areas and dog infrastructure (waste bags and containers) as guidelines for the same NPDc14 —Vegetated Streetscape .

An important gap was identified in the greenspace category, which was the only category to receive a weak score in this analysis. To address this gap and the findings that indicate that having access to a diverse range of greenspaces is essential for well-being, we propose the prerequisite NPDp7 —Greenspace , which ensures that a greenspace (2 ha or 4.9 acres) is available within walking distance from homes (Handley et al., 2003 ). The prerequisite also calls for small and diverse shops along the greenspace boundary, particularly food trucks, because having vendors around makes a greenspace safer (Jacobs, 1961 ; Zuniga-Teran, 2015 ). In addition, we included GIBc17 —Green Play Space , which offers one credit point for including a grassy play space (1 acre or 0.40–ha) safeguarded from traffic and with dwelling units overlooking the space. This space provides a safe area for children to play while adults continue their duties. This type of space has been observed to be used more frequently than traditional playgrounds (e.g., lots for tots ) because children can play without the need of a chaperone ( Jacobs, 1961 ; Mahdjoubi, 2014 ).

Finally, the community category received a moderate score in this study because it did not have a prerequisite in the LEED-ND. Thus, we moved NPDc9 —Access to Civic and Public Spaces from a credit to a prerequisite. This change ensures that a civic space will be placed in a central location within a LEED-ND-certified neighborhood. Similar to greenspace, this space should be surrounded by small and diverse retail.

The proposed LEED-NDW+ captures the main aspects of what our previous study has shown to be essential for facilitating physical activity and supporting human health (Table 13 in the Appendix ). The proposed LEED-NDW+ maintains the sustainable integrity of LEED-ND because the existing prerequisites and number of points are preserved. If implemented, the LEED-NDW+ has the potential to increase physical activity and improve human health, as the LEED-ND has been adopted by municipalities as a design guideline for development (Lewin, 2012 ).

Important caveats should be considered regarding the proposed changes to the LEED-ND. The proposed LEED-NDW+ may be more expensive and difficult to implement by developers because more prerequisites are included that cannot be ignored, and some of these prerequisites may result in loss of profit and/or additional costs. Getting a project LEED-ND certified is difficult. Lewin (2012) indicated that the rigidity of the prerequisites in the LEED-ND is already an impediment for certification for many projects. The proposed LEED-NDW+, which contains even more prerequisites, may discourage developers from pursuing certification.

Incorporating walkability into neighborhood design has been argued to enhance property values; however, the financial benefit comes mainly if low development costs are involved. Pivo and Fisher (2011) observed associations between walkability and higher office, retail, and apartment property values, but warned that developers benefit from this increased value only if it is not exhausted by expenses related to development. The LEED-ND certification process has been described as complex, time-consuming, and expensive for small projects (Lewin, 2012 ); thus, the proposed LEED-NDW+ may be regarded as such to a greater extent.

Although the proposed LEED-NDW+ may be more expensive to implement, and developers may be reluctant to pursue certification, the benefits of some of the proposed prerequisites may translate into elevated property values that may bring profit to developers. The new prerequisite for greenspace (NDPp7 —Greenspace ) means that a piece of land will be set aside for public use and will not bring in direct revenue to the developer in the form of dwelling units or commercial space to sell. However, evidence indicates that proximity to greenspace is correlated with increased property values ( Troy and Grove, 2008 ; Sander and Zhao, 2015 ). In addition, the proposed LEED-NDW+ requires trees along the streets of the neighborhood (NPDp6—Tree-lined Streets ). Although the benefits of trees (e.g., reduced air pollution and noise; increased safety and aesthetics) are not experienced directly by the developer, the presence of trees in a neighborhood is also correlated with increased property values ( Sander and Zhao, 2015 ), which may ultimately benefit developers.

Despite the potential reductions in revenue realized by developers, design guidelines for walkable neighborhoods should be documented and more research on this topic should be conducted. Once the public health benefits of walkable neighborhoods are more evident, and this knowledge is reflected in the market and in public health-driven regulations, having a practical tool, such as the LEED-NDW+, will be useful to guide development toward healthy communities.

The integration of landscape connectivity findings into the LEED-NDW+ should be the next step for this research. Greenspaces in cities should be connected to allow species to move across the urban matrix because urbanization has caused habitat fragmentation that threatens biodiversity (Andersson and Bodin, 2008 ). The LEED-ND must reflect this effect of neighborhood design on the environment, and future revisions should consider prerequisites for connected greenspace (e.g., greenways), which can also promote walkability.

Appendix

See Table 4 , Table 5 , Table 6 , Table 8 , Table 9 , Table 10 , Table 11 , Table 12 ; Table 13 .

| Design elements for connectivity category | LEED-ND Code | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | There must be at least 140 intersections per 2.6 km2 (~1 sqmi) or small blocks allowing intersections to occur at 91 m (~100 yd) or less. Intersections must be 4-way | SLLc1 |

| NPDp3 (case1)a | ||

| NPDc6 | ||

| 2 | Adjacent sites must have a connectivity of 90 intersections per 2.6 km2 (~1 sqmi) | SLLp1 (opt. 2)a |

| NPDp3(case 1)a | ||

| 3 | Avoid gated communities | NPDp3 (case 1)a |

| NPDc6 | ||

| 4 | There must be at least one through-street every 122 m (~400 ft) in the boundary | NPDp3 (case 2)a |

| NPDc6 | ||

| 5 | If there are any cul-de-sac, connect it to pedestrians and bicycles by streets or trails (without barriers) | NPDc6 |

| 6 | The neighborhood should be served by adequate transit system | SLLp1 (opt. 3)a |

| SLLp4 (opt. 3)a | ||

| 7 | Avoid cul-de-sac/ dead-end streets | SLLp1(opt. 2)a |

| 8 | Avoid freeways, railway lines, rivers | |

| 9 | Provide easy access to highways vs. avoid highways | |

| 10 | Avoid fences and allow access to the general public | |

| 11 | The street layout should be a grid | |

| 12 | Grid street networks in high-intensity streets must include visual interruptions like “T” junctures, bridges connecting buildings, slope, and short blocks | |

| 13 | In case of a grid, lay a diagonal across | |

| 14 | In case of a grid, add slight bends that follow topography | |

| 15 | In case of a grid, include a variety of street types and widths | |

| RATIO | 7/15 | |

a. Prerequisites for certification

| Design elements for land-use category | LEED-ND Code | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Provide number of fulltime jobs within 800 m (1/2 mile) of the geographic center of the project that is equal to or greater than the number of dwelling units in the neighborhood | SLLc5 |

| 2 | For office and residential buildings, the ground floor should be retail and must face at least 60% of the street | NPDc11 |

| 3 | Services on the ground floor must have direct access from sidewalk along a public space, not a parking lot | NPDp1-aa |

| NPDc11 | ||

| 4 | Include at least 4 types of services within 5 min walk (400 m) and at least 7 services within 10 min walk (800 m) from most dwelling units* | SLLp1(opt. 4)a |

| SLLc4 | ||

| NPDc3 | ||

| 5 | Services must include food retail with fresh produce | SLLp1(opt. 4)a |

| SLLc4 | ||

| NPDc3 | ||

| 6 | Ensure that at least 50% of the dwelling units are within 400 m (1/4 mile) from a bus or streetcar stop | SLLp1(opt. 3)a |

| SLLc3 | ||

| 7 | For neighborhood centers, entries to services must be within 91 m (~300 ft) from a single common point | NPDc3 |

| 8 | There must be a farmers market within a 10 min walk or 800 m (1/2 mile) from the project’s center | SLLp1(opt. 4)a |

| SLLc4 | ||

| NPDc3 | ||

| NPDc13 | ||

| 9 | There must be an elementary and middle school within a 10 min walk or 800 m (1/2 mile) from 50% of the homes | NPDc15 |

| 10 | There must be a high school within 1.6 km (~1 mile) from 50% of the homes | NPDc15 |

| 11 | Schools must be compact and not exceed an area of 6.ha (~15 acres) for high schools; 4 ha (~10 acres) for middle schools; and 2 ha (~5 acres) for elementary schools | NPDc15 |

| 12 | Include a variety of restaurants | SLLp1(opt. 4)a |

| SLLc4 | ||

| NPDc3 | ||

| 13 | Include mixed-use buildings that include residential/office and retail on the ground floor in all the streets of the neighborhood | NPDc1-l |

| 14 | Include child care services close to homes | SLLp1(opt. 4)a |

| SLLc4 | ||

| NPDc3 | ||

| 15 | No more than 1 bank per block | SLLp1(opt. 4)a |

| SLLc4 | ||

| NPDc3 | ||

| 16 | Avoid large sized services | NPDc1-d,e |

| 17 | Services must have different working hours | |

| 18 | Provide a variety of shops along the routes to school | |

| 19 | Avoid fast-food restaurants, corner markets, and liquor stores | |

| 20 | Open corridors between housing buildings must include a variety of uses | |

| 21 | Corners must have retail on the ground level | |

| 22 | Insure zoning for deliberate diversity that limits the amount of the same service within a certain area | |

| 23 | Insure that public buildings stay staunch even if property values increase | |

| 24 | In the case of “borders” such as waterfronts, railways, freeways, and other massive single uses (e.g., hospitals, university campuses), locate services that make direct use of the border itself | |

| RATIO | 16/24 | |

a. Prerequisites for certification.

| Type of density | Design elements for density category | LEED-ND Code | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residential | 1 | Suburbs must have a residential density of at least 17 dwelling units per ha (7 units per acre) | NPDp2(case 2)a |

| 2 | Semi-suburbs must have a residential density of 25–49 dwelling units per ha (10–20 units per acre) | NPDp2(case 1)a | |

| NPDc2 | |||

| 3 | Urban neighborhoods must have a residential density of at least 247 dwelling units per ha (100 units per acre) | ||

| 4 | High-rise buildings must not be too close to one another | ||

| Retail | 5 | Suburbs must have a retail density of at least 0.50 FAR | NPDp2(case 2)a |

| 6 | Semi-suburbs must have a retail density of 0.8–3.0 FAR | NPDp2(case 1)a | |

| NPDc2 | |||

| All | 7 | Locate the project on an infill site | SLLp1 (opt. 1)a |

| SLLp4 (opt. 2)a | |||

| SLLc1 | |||

| 8 | Locate the project in a redeveloped brownfield | SLLc2 | |

| 9 | Locate the project in a designated receiving area for development rights | SLLp4 (opt. 4)a | |

| 10 | Building frontage should maintain the pedestrian scale (low rise buildings/podium) pushing high-rise towers away from pedestrian sight | ||

| 11 | High-rise buildings must not be too close to one another | ||

| 12 | Space between buildings must have clear private and public spaces | ||

| 13 | Buildings should not cover more than 70% of the buildable land | ||

| 14 | Maintain a homogenous density of 37-74 dwelling units per ha (15–30 units per acre) throughout the city | ||

| Schools | 15 | Design compact schools: elementary – 2 ha (5 acres), middle school - 4 ha (10 acres), high-school – 6 ha (15 acres) | NPDc15 |

| RATIO | 8/15 | ||

a. Prerequisites for certification.

| Design elements for surveillance category | LEED-ND Code | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A principal entry faces a public space, not a parking lot | NPDp1-aa |

| 2 | All ground level retail uses that face a public space must have clear glass on at least 60% of their facades between 0.91 and 2.4 m (3–8 ft) above grade | NPDc1-f |

| 3 | For residential, the ground floor of at least 50% of the units must have an elevation of more than 60 cm (24 in) above the sidewalk | NPDc1-k |

| 4 | Ground floor of buildings must have retail, live/work or dwelling units that have access to public space | NPDc1-l |

| 5 | Avoid wide streets with low-rise buildings. Building height-to-street-width ratio of 1:3 | NPDp1-ba |

| NPDc1-m | ||

| 6 | Avoid blank walls (no windows or doors) longer than 15 m (50 ft) | NPDc1-g |

| 7 | Setbacks of 8 m (~25 ft) or less for 80% of street-facing buildings | NPDc1-a |

| 8 | Locate buildings close to the streets. Setbacks of 5 m (~18 ft) or less for 50% of street-facing buildings | NPDc1-b |

| 9 | Setbacks of 0.3 m (~1 ft) for at least 50% of mixed used and non-residential street-facing buildings | NPDc1-c |

| 10 | Building entries occur at an average of 9–23 m (~30–75 ft) or less along mixed or non-residential buildings | NPDc1-d |

| NPDc1-e | ||

| 11 | Include trees | NPDc14 |

| 12 | Setbacks of 3 m (10 ft) that include a front yard allow a semi-private space between homes and public space | |

| 13 | Garage doors facing the street should be avoided | |

| 14 | Include outdoor cafes on the streets | |

| 15 | Provide lighting on the streets and outdoor spaces | |

| 16 | Orient the buildings toward the street: front porches, windows, storefronts, balconies, entries | |

| RATIO | 11/16 | |

a. Prerequisites for certification.

| Design elements for parking category | LEED-ND Code | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reduce parking footprint. Either do not build off-street parking or build parking lots at the side or rear of buildings leaving frontages free of surface parking | NPDc5 |

| 2 | Do not allow more than 20% of footprint area is used for off-street parking | NPDc5 |

| 3 | Do not allow parking lots greater than 0.8 ha (~2 acres) | NPDc5 |

| 4 | For non-residential, provide carpool and/or shared-use vehicle parking spaces for 10% of parking, with signage and within 60 m (~200 ft) of building entries | NPDc5 |

| 5 | Parking spaces are sold or rented separately from the dwelling units or square footage of non-residential | NPDc8 |

| 6 | Provide on-street parking on 70% of both sides of the streets | NPDc1-i |

| 7 | Include at least one vehicle from a vehicle-sharing program within a 5 min walk of the dwelling units | NPDc8 |

| 8 | Integrate parking in the building base | NPDc5 |

| 9 | Downtown parking should be 200 spaces per 1000 workers | |

| 10 | If parking lots/garages cannot be avoided, surround these by small blocks (intersections occurring every 48 m or 160 ft) | |

| 11 | Surrounding areas of parking lots must have diverse services (e.g., shops, restaurants) | |

| 12 | Sharing parking between uses can significantly reduce the parking area requirements | |

| 13 | Screen or hide parking behind landscaping | |

| 14 | Locate parking and drop-off areas along secondary streets but within blocks of primary streets | |

| RATIO | 8/14 | |

| Design elements for experience category | LEED-ND Code | |

|---|---|---|

| Streetscape | ||

| 1 | Building-height-to-street-width ratio of 1:3 | NPDp1-ba |

| 2 | Avoid gaps in the street wall (empty lots or low rise buildings in high-rise street) | |

| Aesthetics | ||

| 3 | Include trees along most of the length of the sidewalks at intervals of no more than 12 m (50 ft) | NPDc14 |

| 4 | Maximize store-front transparency to create visual interest and void shutting windows at night. | NPDc1-h |

| 5 | Include a diversity of building types and ages. Provide affordable housing. | SLLc1 |

| NPDc4 | ||

| GIBc5 | ||

| 6 | Preserve historic resources | GIBc6 |

| 7 | Provide 2 units of soil per 1 unit of tree height to allow trees to grow big and tall | NPDc14 |

| 8 | Include a green infrastructure and a diversity of tree species to reduce risk of flooding | GIBc8 |

| 9 | Include landscaping along sidewalks and other outdoor areas | |

| 10 | Insure clean streets (e.g., cleaning programs) to avoid trash and graffiti | |

| 11 | For high-intensity streets, add “unifiers” such as trees spaced uniformly, pavements with strong patterns, or colored awnings | |

| 12 | For low-intensity streets, avoid “sameness” by using different design of facades and different building types | |

| 13 | Add street furniture such as benches facing passing crowds | |

| 14 | Provide awnings, marquees, arcades or galleries on the streets | |

| 15 | Provide continuous maintenance to vegetation | |

| Thermal comfort | ||

| 16 | Provide shade on at least 50% of the hardscape (e.g., plants that provide shade) | GIBc9 |

| 17 | Provide shade on the hardscape with a light colored roof finish (or SRI of at least 29) | GIBc9 |

| 18 | Use paving materials that are light-colored (SRI of at least 29) | GIBc9 |

| 19 | Low-slope roofs must have an initial SRI of 78 and steep-slope roofs must have an initial SRI of 29 | GIBc9 |

| 20 | Include vegetated roofs on at least 50% of the total roof area | GIBc9 |

| 21 | Include water bodies in outdoor spaces. Limit development within 15 m (~50 ft) of existing wetlands and 30 m (~100 ft) of existing water bodies | SLLp3(opt.1)a |

| SLLc7 | ||

| SLLc8 | ||

| SLLc9 | ||

| 22 | Include shading devices such as awnings in sidewalks | NPDc14 |

| 23 | Include high-rise buildings to provide shade to the streets | NPDp1-ba |

| 24 | Include deciduous trees | |

| Wayfinding | ||

| 25 | Include landmarks or artworks at key vista points or axial termini and corners | |

| 26 | Include radically different uses to increase landmarks and focal points | |

| 27 | Include appropriate signage, clear edges, distinctive buildings, and pathways | |

| Slope | ||

| 28 | Low slopes (<15%) are desirable | SLLc6 |

| 29 | Include hilly streets | |

| Fumes/noise | ||

| 30 | Include large areas of vegetation on heavy-traffic streets to improve air quality and reduce noise and fumes | |

| Dogs | ||

| 31 | Include high fences in dog areas away from children’s areas and busy roads | |

| 32 | Provide dog-related infrastructure (e.g., dog litter bags, bins, signage, accessible water sources) | |

| RATIO | 16/32 | |

| ||

| Design elements for greenspace category | LEED-ND Code | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Leave a portion of the site of 10%–20% that has not been developed undisturbed in order to maintain native vegetation and pervious surfaces | GIBc7 |

| 2 | Provide an accessible greenspace to all homes | NPDc3 |

| NPDc9 | ||

| 3 | Locate an outdoor or indoor public recreational facility of at least 0.40 ha (1 acre) for outdoors and 0.23 ha (1/2 acre) for indoors within 0.80 km (1/2 m) of 90% of the dwelling units | NPDc10 |

| 4 | Outdoor facility must include tot-lots for children, swimming pools and sports fields | NPDc10 |

| 5 | Provide an accessible 2 ha (4.9 acres) greenspace no more than 300 m (984 ft) from 100% of dwelling units. | NPDc3 |

| NPDc9 | ||

| 6 | Provide at least 1 accessible 20 ha (49.4 acres) greenspace within 2 km (1.24 miles) | |

| 7 | Provide at least 1 accessible 100 ha (247.1 acres) greenspace within 5 km (3.1 miles) | |

| 8 | Provide at least 1 accessible 500 ha (1235.5 acres) greenspace within 10 km | |

| 9 | Greenspace must be surrounded by a variety of shops and include inside vendors; all working different hours | |

| 10 | Avoid “superblocks” in surroundings of greenspace by including multiple public intersections with accesses to houses and stores | |

| 11 | Greenspace must promote a variety of uses by changing the rise in the ground, the grouping of trees and the openings leading to various focal points | |

| 12 | Design the greenspace so that it includes a center as a main crossroad | |

| 13 | Greenspace must have a variety of sun exposure (shaded vs. sunny areas) | |

| 14 | Greenspace must include spaces for cultural events | |

| 15 | Greenspace must include spaces for several activities like biking (washing, renting, repair), kite-flying (buying, repair), bar-b -ques, and ice-skating (cold weather) | |

| 16 | There must be vegetation (nature) throughout the entire neighborhood and accessible to all homes | |

| 17 | Promote businesses that sell products related to uses inside the greenspace and locate these vendors along the borders of the greenspace (e.g., bike rentals, kite shops, food trucks) | |

| 18 | Regulate the low-height of buildings on the south side of greenspace to allow the sun during winter months | |

| 19 | Include sheds for vendors’ carts on bordering streets of parks | |

| 20 | Locate a neighborhood park at the end of streets to discourage automobile-use | |

| 21 | Locate a greenspace close to high-rise towers so that all units have a view of nature | |

| 22 | Avoid playgrounds or locate them where parents can do alternative activities while watching the kids | |

| 23 | Link the greenspaces together by integrating nature into the neighborhoods | |

| 24 | Include greenspace with high biodiversity | |

| 25 | Provide continuous maintenance to vegetation | |

| 26 | Provide dog-related infrastructure | |

| 27 | Include well-fenced areas for off-leashed dogs, away from children’s play areas | |

| RATIO | 5/27 | |

| Design elements for community category | LEED-ND Code | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Include a diversity of housing types | SLLc1 |

| NPDc4 | ||

| 2 | Include affordable housing | NPDc4 |

| 3 | Increase the proportion of areas usable by people of diverse abilities | NPDc11 |

| 4 | Advertise an open community meeting and solicit their input on the design | NPDc12 |

| 5 | Conduct a charrette of at least 2 days open to the public to get input on the design | NPDc12 |

| 6 | Dedicate space for food production within the neighborhood | NPDc13 |

| 7 | Provide an accessible civic space of at least 0.67 ha (1/6 acre) within 1/4 mile of 90% of the homes. For projects larger than 10 acres must have a space of at least 0.4 ha (1 acre) | NPDc9 |

| 8 | The proportion of the civic space must not be narrower than 1 unit of width to 4 units of length | NPDc9 |

| 9 | Include trees | NPDc14 |

| 10 | Provide public spaces (e.g., community center, churches, parks, recreational facilities) | SLLc4 |

| NPDc3 | ||

| NPDc10 | ||

| 11 | Promote a self-governing body or neighborhood association | |

| 12 | Add irregularities to the building line along sidewalks to create niches that allow incidental play for children | |

| 13 | Avoid blacklisting neighborhoods for renovation credits | |

| 14 | Include a variety of dwelling units sizes in high-rise buildings (2 & 3 bedroom units) that can accommodate families | |

| 15 | Include shared outdoor spaces (e.g., shared facilities, open space) | |

| RATIO | 10/15 | |

| Code | Type | Design Element | Possible points for certification | Changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smart Location & Linkage (SLL) | ||||

| SLLp1 | Prereq | Smart Location | Required | |

| SLLp2 | Prereq | Imperiled Species and Ecological Communities | Required | |

| SLLp3 | Prereq | Wetland and Water Body Conservation | Required | |

| SLLp4 | Prereq | Agricultural Land Conservation | Required | |

| SLLp5 | Prereq | Floodplain Avoidance | Required | |

| SLLc1 | Credit | Preferred Locations | 2 | −8 |

| SLLc2 | Credit | Brownfield Remediation | 2 | |

| SLLc3 | Credit | Access to Quality Transit | 7 | |

| SLLc4 | Credit | Bicycle Facilities | 2 | |

| SLLc5 | Credit | Housing and Jobs Proximity | 3 | |

| SLLc6 | Credit | Steep Slope Protection | 1 | |

| SLLc7 | Credit | Site Design for Habitat or Wetland and Water Body Conservation | 1 | |

| SLLc8 | Credit | Restoration of Habitat or Wetlands and Water Bodies | 1 | |

| SLLc9 | Credit | Long-Term Conservation Management of Habitat or Wetlands & Water Bodies | 1 | |

| Total | 20 | |||

| Neighborhood Pattern & Design (NPD) | ||||

| NPDp1 | Prereq | Walkable Streets | Required | |

| NPDp2 | Prereq | Compact Development | Required | Eliminate Option 2 |

| NPDp3 | Prereq | Connected and Open Community | Required | |

| NPDp4 | Prereq | Mixed-use Development | Required | Prerequisite added |

| NPDp5 | Prereq | Pedestrian and Bicycle Infrastructure | Required | Prerequisite added |

| NPDp6 | Prereq | Tree-lined Streets | Required | Prerequisite added |

| NPDp7 | Prereq | Greenspace | Required | Prerequisite added |

| NPDp8 | Prereq | Access to Civic & Public Space | Required | Prerequisite added |

| NPDp9 | Prereq | Pedestrian Scale | Required | Prerequisite added |

| NPDp10 | Prereq | Parking Location | Required | Prerequisite added |

| NPDc1 | Credit | Walkable Streets | 12 | +3 |

| NPDc2 | Credit | Compact Development | 6 | |

| NPDc3 | Credit | Mixed-Use Neighborhoods | 4 | |

| NPDc4 | Credit | Housing Types and Affordability | 7 | |

| NPDc5 | Credit | Reduced Parking Footprint | 1 | |

| NPDc6 | Credit | Connected and Open Community | 2 | |

| NPDc7 | Credit | Transit Facilities | 1 | |

| NPDc8 | Credit | Transportation Demand Management | 2 | |

| NPDc9 | Credit | Access to Recreation Facilities | 1 | |

| NPDc10 | Credit | Visitability and Universal Design | 1 | |

| NPDc11 | Credit | Community Outreach and Involvement | 2 | |

| NPDc12 | Credit | Local Food Production | 1 | |

| NPDc13 | Credit | Vegetated Streetscapes | 2 | +1 |

| NPDc14 | Credit | Neighborhood Schools | 1 | |

| NPDc15 | Credit | Child Care Facility | 1 | +1 |

| NPDc16 | Credit | Traffic-Calming Treatments | 2 | +2 |

| NPDc17 | Credit | Street Design | 2 | +2 |

| Total | 49 | |||

| Green Infrastructure & Buildings (GIB) | ||||

| GIBp1 | Prereq | Certified Green Building | Required | |

| GIBp2 | Prereq | Minimum Building Energy Performance | Required | |

| GIBp3 | Prereq | Indoor Water Use Reduction | Required | |

| GIBp4 | Prereq | Construction Activity Pollution Prevention | Required | |

| GIBp5 | Prereq | Lighting | Required | Prerequisite added |

| GIBc1 | Credit | Certified Green Buildings | 5 | |

| GIBc2 | Credit | Optimize Building Energy Performance | 2 | |

| GIBc3 | Credit | Indoor Water Use Reduction | 1 | |

| GIBc4 | Credit | Outdoor Water Use Reduction | 2 | |

| GIBc5 | Credit | Building Reuse | 1 | |

| GIBc6 | Credit | Historic Resource Preservation and Adaptive Reuse | 2 | |

| GIBc7 | Credit | Minimized Site Disturbance | 1 | |

| GIBc8 | Credit | Rainwater Management | 4 | |

| GIBc9 | Credit | Heat Island Reduction | 1 | |

| GIBc10 | Credit | Solar Orientation | 1 | |

| GIBc11 | Credit | Renewable Energy Production | 3 | |

| GIBc12 | Credit | District Heating and Cooling | 2 | |

| GIBc13 | Credit | Infrastructure Energy Efficiency | 1 | |

| GIBc14 | Credit | Wastewater Management | 2 | |

| GIBc15 | Credit | Recycled and Reused Infrastructure | 1 | |

| GIBc16 | Credit | Solid Waste Management | 1 | Added specification for location |

| GIBc17 | Credit | Green Play Space | 1 | +1 |

| Total | 31 | |||

| Innovation & Design Process (IDP) | ||||

| IDPc1 | Credit | Innovation | 5 | |

| IDPc2 | Credit | LEED® Accredited Professional | 1 | |

| Total | 6 | |||

| Regional Priority Credits (RP) | ||||

| RPc1 | Credit | Regional Priority Credit: Region Defined | 1 | |

| RPc2 | Credit | Regional Priority Credit: Region Defined | 1 | |

| RPc3 | Credit | Regional Priority Credit: Region Defined | 1 | |

| RPc4 | Credit | Regional Priority Credit: Region Defined | 1 | |

| Total | 4 | |||

| TOTAL | 110 | |||

See Table 7.1 , Table 7.2 , Table 7.3 ; Table 7.4 .

| Design elements for the pedestrian section of the traffic safety category | LEED-ND Code | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Provide continuous sidewalks along both sides of 90% of the streets | NPDp1-ca |

| 2 | Sidewalks on residential areas must be at least 1.2–1.5 m (4–5 ft) wide | NPDp1-ca |

| NPDc1-j | ||

| 3 | Sidewalks on retail or mixed use blocks must be 2.4–3 m (~8–10 ft) wide | NPDc1-j |

| 4 | Provide on-street parking on 70% of both sides of the streets | NPDc1-i |

| 5 | No more than 20% of the street frontage are faced by garage openings and service bays | NPDp1-da |

| 6 | Minimize at-grade crossings of sidewalks with driveways | NPDc1-p |

| 7 | Guaranteed ride home | NPDc8 |

| 8 | Universal design: Design homes and streets that can be used by a wide spectrum of people regardless of ability or age | NPDc11 |

| 9 | Provide a strip of vegetation with large trees that separates the sidewalks from the roads | |

| 10 | Provide maintenance to the sidewalks to ensure evenness | |

| 11 | Provide pedestrian-only streets | |

| 12 | Widen sidewalks at intersections | |

| 13 | Provide pedestrian lights with countdown timers | |

| RATIO | 8/13 | |

a. Prerequisites for certification.

| Design elements for the bicycles section of the traffic safety category | LEED-ND Code | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Include a bicycle network and pedestrian trail within 400 m (1/4 mile) of the project | SLLc4 |

| 2 | For residential projects, a bicycle network is within 400 m (1/4 mile) of boundary and connects to a school or employment center within 4.8 km (3 miles) | SLLc4 |

| 3 | Include a bicycle network within 400 m (1/4 mile) of boundary that connects at least 10 diverse uses within 3.21 km (3 miles) | SLLc4 |

| 4 | Residential: provide bicycle parking and storage capacity of at least 1 space/dwelling unit | SLLc4 |

| NPDc5-a | ||

| 5 | Retail: provide bicycle parking and storage capacity of: 1 space/465 m2 (5,000 sqft) of retail space. Bicycle storage must be located within 30 m (~100 ft) of main entries | SLLc4 |

| NPDc5-b | ||

| 6 | Non-residential other than retail: provide 1 storage for 10% occupancy and visitor rack on-site of 1 space per 930 m2 (~10,000 sqft), and no less than 4 spaces per building | SLLc4 |

| NPDc5-c | ||

| 7 | Provide at least 1 on-site shower with changing facility for any development with 100 workers | SLLc4 |

| NPDc5-b | ||

| 8 | Bicycle racks must be located in visible areas from main entries of buildings, served with lighting. | SLLc4 |

| NPDc5-c | ||

| 9 | Guaranteed ride home | NPDc8 |

| 10 | Provide continuous bike lanes throughout the neighborhood | NPDc15 |

| 11 | Give bicycles priority at intersections | |

| 12 | Maintain bike lanes with smooth surfaces and remove loose gravel | |

| 13 | Devote space on the streets for bicycle and car-sharing businesses | |

| 14 | Include a bike lane on every street buffered from the road | |

| 15 | Elevate bike lanes and crossroads a few inches | |

| 16 | Include signalized intersections (stop-controlled) | |

| 17 | Provide lighting | |

| 18 | Color-pavement markings | |

| 19 | Avoid steep slopes for bike routes | |

| RATIO | 10/19 | |

| Design elements for the transit systems section of the traffic safety category | LEED-ND Code | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dwelling units must be located within a 10 min walk (800 m) from transit stops and 5 min walk (400 m) from bus stops | SLLp1(opt.3)a |

| 2 | There are short and direct routes from homes to bus stops (<400 m) and transit stops (<800 m) | SLLp1(opt.3)a |

| 3 | Provide safe, convenient, and comfortable transit waiting areas and safe and secure bicycle storage for transit users | NPDc7 |

| 4 | Provide kiosks, bulletin boards or signs that displays transit schedules and route information at each public transit stop | NPDc7 |

| 5 | Provide information about the journey on screens at each public transit stop or on smartphone apps | NPDc7 |

| 6 | Provide annual transit passes at a reduced price to residents and occupants of the buildings in the project | NPDc8 |

| 7 | Provide private transit service (vans, shuttles, buses) from a central point of the neighborhood to transit facilities or other important destinations sponsored by the developer | NPDc8 |

| 8 | Guaranteed ride home | NPDc8 |

| 9 | Buses must show-up every 15 min or less | |

| 10 | Boost the status of public transit by creating state-of-the-art public transit stops and units | |

| 11 | Provide bus-only lanes and intersection priority to transit systems | |

| 12 | Designate buses, taxis and trucks-only streets | |

| RATIO | 8/12 | |

a. Prerequisites for certification.

| Design elements for the traffic-calming treatments section of the traffic safety category | LEED-ND Code | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Speed limit on residential areas is 30 km/h (~19 mph) or less | NPDc1-n |

| 2 | Speed limit on non-residential or mixed-use streets is 40 km/h (~25 mph) or less | NPDc1-o |

| 3 | Include medians and crossroads every 244 m (~800 ft) on busy streets and access lanes with a speed limit of 40 km/h (~25 mph) | NPDc1-o |

| 4 | Provide a combination of traffic control and calming measures on routes from dwelling units to schools | NPDc15 |

| 5 | Include brightly painted crosswalks raised a few inches above the roadway on street intersections | |

| 6 | Widen sidewalks at the intersections | |

| 7 | Designate pedestrian zones/streets | |

| 8 | Toll on cars entering the city core | |

| 9 | Install speed bumps along streets | |

| 10 | Narrow streets | |

| 11 | Place a small park at the end of streets | |

| 12 | Use cobblestone for street paving | |

| 13 | Place trees and other elements (e.g., monuments) in the middle of the roads | |

| 14 | Small corner radii to force cars to slow down when turning | |

| 15 | Create woonerf streets | |

| 16 | Place roundabouts at street intersections | |

| 17 | Provide a shoulder lane on intersections between arterials and secondary roads | |

| 18 | Avoid multiple lane boulevards (more than 4 lanes) | |

| RATIO | 4/18 | |

References

- Adlakha et al., 2016 D. Adlakha, J.A. Hipp, R.C. Brownson; Adaptation and evaluation of the Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale in India (NEWS-India); Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 13 (2016), p. 401 http://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13040401

- Andersson and Bodin, 2008 E. Andersson, O. Bodin; Practical tool for landscape planning? An empirical investigation of network based models of habitat fragmentation; Ecography, 32 (1) (2008), pp. 123–132

- Cerin et al., 2006 E. Cerin, B.E. Saelens, J.F. Sallis, L.D. Frank; Neighborhood environment walkability scale: validity and development of a short form; Med. Sci. Sports Exerc., 38 (2006), pp. 1682–1691

- Chu et al., 2004 A. Chu, A. Thorne, H. Guite; The impact on mental well-being of the urban and physical environment: an assessment of the evidence; J. Public Ment. Health, 3 (2) (2004), pp. 17–32

- Clark et al., 2010 C. Clark, B. Candy, S. Stansfeld; A systematic review on the effect of the built and physical environment on mental health; J. Public Ment. Health, 6 (2) (2010)

- Frank et al., 2003 L.D. Frank, P.O. Engelke, T.L. Schmid; Health and Community Design: The Impact of the Built Environment on Physical Activity, Island Press, Washington DC, USA (2003)

- Gallimore et al., 2011 J.M. Gallimore, B.B. Brown, C.M. Werner; Walking routes to school in new urban and suburban neighborhoods: an environmental walkability analysis of blocks and routes; J. Environ. Psychol., 31 (2) (2011), pp. 184–191 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2011.01.001

- Garde, 2009 A. Garde; Sustainable by design? Insights from U.S. LEED-ND pilot projects; J. Am. Plan. Assoc., 75 (4) (2009), pp. 424–440 http://doi.org/10.1080/01944360903148174

- Gifford, 2014 Gifford, R., 2014. The consequences of living in high-rise buildings. Presented at the 51st International Making Cities Livable, Portland, Oregon.

- Handley et al., 2003 J. Handley, S. Pauleit, P. Slinn, A. Barber, M. Baker, C. Jones, S. Lindley; Accessible Natural Green Space Standards in Towns and Cities: a Review and Toolkit for Their Implementation; University of Manchester, Manchester, UK (2003) (Project undertaken on behalf of English Nature)

- Herrick, 2009 C. Herrick; Designing the fit city: public health, active lives, and the (re)instrumentalization of urban space; Environ. Plan. A, 41 (10) (2009), pp. 2437–2454 http://doi.org/10.1068/a41309

- Jackson, 2003 L.E. Jackson; The relationship of urban design to human health and condition; Landsc. Urban Plan., 64 (4) (2003), pp. 191–200

- Jacobs, 1961 J. Jacobs; The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Random House, Inc, New York, NY (1961)

- Knack, 2010 R.E. Knack; LEED-ND: what the skeptics say; Planning (2010), pp. 18–21

- Lewin, 2012 S.S. Lewin; Urban sustainability and urban form metrics; Coll. Publ., 7 (2) (2012), pp. 44–63

- Luederitz et al., 2013 C. Luederitz, D.J. Lang, H. Von Wehrden; A systematic review of guiding principles for sustainable urban neighborhood development; Landsc. Urban Plan., 118 (2013), pp. 40–52 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.06.002

- Mahdjoubi, 2014 Mahdjoubi, L., 2014. Active life enabled by child-friendly environment. Presented at the 51st International Making Cities Livable, Portland, Oregon.

- Montgomery, 2013 C. Montgomery; Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design; Farrar, Straus & Giroux, United States (2013)

- Napier et al., 2011 M.A. Napier, B.B. Brown, C.M. Werner, J. Gallimore; Walking to school: community design and child and parent barriers; J. Environ. Psychol., 31 (1) (2011), pp. 45–51 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.04.005

- Pivo and Fisher, 2011 G. Pivo, J.D. Fisher; The walkability premium in commercial real estate investments; Real. Estate Econ., 39 (2) (2011), pp. 185–219 http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6229.2010.00296.x

- Sander and Zhao, 2015 H.A. Sander, C. Zhao; Urban green and blue: who values what and where?; Land Use Policy, 42 (2015), pp. 194–209 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.07.021

- Sandifer et al., 2015 P.A. Sandifer, A.E. Sutton-Grier, B.P. Ward; Exploring connections among nature, biodiversity, ecosystem services, and human health and well-being: opportunities to enhance health and biodiversity conservation; Ecosyst. Serv., 12 (2015), pp. 1–15 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.12.007

- Sharifi and Murayama, 2013 A. Sharifi, A. Murayama; A critical review of seven selected neighborhood sustainability assessment tools; Environ. Impact Assess. Rev., 38 (2013), pp. 73–87 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2012.06.006

- Sharifi and Murayama, 2014 A. Sharifi, A. Murayama; Neighborhood sustainability assessment in action: cross-evaluation of three assessment systems and their cases from the US, the UK, and Japan; Build. Environ., 72 (2014), pp. 243–258 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2013.11.006

- Soltero, 2015 E.G. Soltero; Physical activity resource and user characteristics in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico; Retos: Nuevas Perspect. De. Educ. Física, Deporte Y. Recreación, 28 (2015), pp. 203–206

- Stevens and Brown, 2011 R.B. Stevens, B.B. Brown; Walkable new urban LEED_neighborhood-development (LEED-ND) community design and children׳s physical activity: selection, environmental, or catalyst effects?; Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Activity, 8 (2011), p. 139

- Stockton et al., 2016 J. Stockton, O. Duke-Williams, E. Stamatakis, J. Mindell, E.J. Brunner, N.J. Shelton; Development of a novel walkability index for London, United Kingdom: cross-sectional application to the Whitehall II study; BMC Public Health, 16 (2016), p. 416 http://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3012-2

- Troy and Grove, 2008 A. Troy, J.M. Grove; Property values, parks, and crime: a hedonic analysis in Baltimore, MD; Landsc. Urban Plan., 87 (3) (2008), pp. 233–245 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2008.06.005

- Veitch et al., 2016 J. Veitch, G. Abbot, A.T. Kaczynski, S.A. Wilhelm Stanis, G.M. Besenyi, K.E. Lamb; Park availability and physical activity, TV time, and overweight and obesity among women: Findings from Australia and the United States; Health Place (2016)

- Ward. et al., 2016 J.S. Ward, J.S. Duncan, A. Jarden, T. Steward; The impact of children׳s exposure to greenspace on physical activity, cognitive development, emotional wellbeing, and ability to appraise risk; Health Place, 40 (2016), pp. 44–50

- Woldeamanuel and Kent, 2016 M. Woldeamanuel, A. Kent; Measuring walk access to transit in terms of sidewalk availability, quality, and connectivity; J. Urban Plan. Dev., 142 (2) (2016), p. 04015019

- Zuniga-Teran, 2015 A.A. Zuniga-Teran; From Neighborhoods to Wellbeing and Conservation: Enhancing the Use of Greenspace Through Walkability (Dissertation Thesis), University of Arizona Press (2015)

Document information

Published on 12/05/17

Submitted on 12/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?