Abstract

More than 60% of older Americans have sedentary lifestyles1 and are recommended more physical activities for health benefit. Nearby outdoor environments on residential sites may impact older inhabitants׳ physical activities there (defined as walking, gardening, yard work, and other outdoor physical activities on residential sites). This study surveyed 110 assisted-living residents in Houston, Texas, regarding their previous residential sites before moving to a retirement community and physical activities there. Twelve environmental features were studied under four categories (typology, motivators, function, and safety). Based on data availability, a subset of 57 sample sites was analyzed in Geographic Information Systems. Hierarchical linear modeling was applied to estimate physical activities as a function of the environments. Higher levels of physical activity were found to be positively related with four environmental features (transitional-areas, connecting-paths, walk-ability, and less paving).

Keywords

Physical activity ; Residential site ; Environments ; Older adults ; Survey ; Geographic Information Systems

1. Introduction

Associated with generally increased life expectancy, aging is a global phenomenon. World-wide monthly growth of the senior population group (65 and older) was 795,000 in 2000 and estimated to be 847,000 in 2010 (Kinsella and Velkoff, 2001 ). From 2000 to 2030, this population segment will increase from 35 million to 71.5 million in the U.S. (FIFARS, 2004 ). For Americans aged 65 years, the current life expectancy is 19.2 more years on average (FIFAS, 2012 ). More than 60% of older Americans have sedentary lifestyles (DHHS, 1996 ). It was found that older adults spend an average of 19.5 h per day at their homes, which was the longest found among different age groups (Brasche and Bischof, 2005 ; Moss and Lawton, 1982 ).

For older adults, the U.S. Surgeon General recommends at least 30 min of moderate physical activities most days of the week (DHHS, 2001 ). By engaging in appropriate physical activities, the risk of heart disease, diabetes, colon cancer, and high blood pressure can be reduced; the strength of bones, joints, and muscles can be improved (CDC, 1996 ). Outdoor environments near home, including neighborhoods and the outdoors on residential sites or properties, can be the most readily available places for older adults to engage in physical activities. The most popular physical activities among older adults include walking, gardening, and yard work (DHHS, 1996 ). These activities are inexpensive, require minimal equipment, and can adapt flexibly to different schedules. Furthermore, by being physically active in the yard or on the property in which they live, older adults can access to nature and possibly engage in social interactions. Viewing delightful nature scenes may tend to increase positive emotions and reduce depression (Ulrich, 1991 ). Engaging in social interactions can reduce the risk of dementia in older adults (Wang et al., 2002 ).

To make older adults more physically active, their nearby outdoor environments should make physical activities more attractive, functional, and safe. In the neighborhoods with functional pedestrian facilities, such as comfortable sidewalks along walking routes, senior residents were found to engage in more physical activities (Owen et al ., 2004 ; Patterson and Chapman, 2004 ; Wang and Lee, 2010 ). Moreover, having desirable destinations within walking distance from home may motivate people to walk outdoors. In traditional urban neighborhoods, where pedestrians have access to recreational and utilitarian destinations for daily living, older adults have high levels of outdoor physical activities (Patterson and Chapman, 2004 ; Saelens et al ., 2003 ; Wister, 2005 ). Further, environmental safety from traffic and crime could be a critical concern of less-competent older adults going outside. Neighborhood safety is related to older adults׳ outdoor physical activities (Humpel et al ., 2002 ; Owen et al ., 2004 ). Most of the above findings were regarding neighborhood environments. There is limited evidence to indicate the specific site environmental factors related with physical activities.

Immediately adjacent to home, residential site environments such as yards are both origins of outdoor trips and destinations on the way back to home. Distinguished from necessary physical activities (such as walking to bus stations for a daily commute), most physical activities on residential sites or properties are optional. As older adults are typically more environmentally docile than young people, the quality of residential site environments is an important concern in promoting physical activities among the elderly (Lawton, 1985 ; Lawton, 1989 ; Lawton and Simon, 1968 ). Adding value to the previous literature, this research studied twelve environmental features on and around residential sites, which are thought to be associated with older adults’ physical activities.

2. Methodologies

The structure of relationships between physical activities and personal factors, social and physical environmental factors was described in the Social Ecological Model (Zimring, Joseph et al., 2005 ). Based on this model, the value of physical environmental factors on residential sites in predicting levels of older adults׳ physical activities was examined in this study. Table 1 listed the studied personal and social factors.

| Personal variables | Social variables |

| 1. Age⁎ | 1. Living arrangement (alone or not) |

| 2. Gender | 2. Building ownership⁎ |

| 3. IADLs (a measure of functional competence) | 3. Environmental safety from traffic |

| 4. Self-efficiency | 4. Environmental safety from Crime |

| 5. Education⁎ |

Notes : p -Value determines the significance of results in hypothesis tests; a small p -value (typically≤0.05) indicates strong evidence supporting the hypothesis.

⁎. Significant variables, p <0.05. Italic: test variables filtered from all variables of interest by correlation tests. IADLs: Instrumental Activities of Daily Living – a measure of functional competence.

Focus of this study is the residential site environments, which older adults can access without crossing streets or vehicular traffic. The environments should be attractive, functional and safe, as perceived by older adults both from the indoors and in the outdoor settings. Based on findings from previous research, twelve environmental factors were studied under four categories: (1) Typology, (2) Motivators, (3) Functionality, and (4) Safety (Table 2 ).

| Category | Variable | Collection method |

|---|---|---|

| Typology | 1. Site type (corner lot or not) | GIS |

| 2. Parcel size | GIS | |

| 3. Lot coverage | GIS | |

| Motivators | 4. Yard landscaping | Survey |

| 5. Presence of transitional-areas⁎ | GIS | |

| Functionality | 6. Perceived site walkability⁎ | Survey |

| 7. Sum of connecting-paths⁎ | GIS | |

| 8. Average width of side-areas | GIS | |

| 9. Presence of paving⁎ | Survey | |

| 10. Shading of tree canopy | GIS, Survey | |

| Safety | 11. Distance from site entrance to the nearest street intersection | GIS |

| 12. Building setback from streets |

Notes:'p -Value determines the significance of results in hypothesis tests; a small p -value (typically≤0.05) indicates strong evidence supporting the hypothesis.

⁎. Significant variables, p <0.05. Italic: test variables filtered from all variables of interest by correlation tests.

If people could pass through multiple spaces while traversing a residential site/lot and have destinations (e.g., gardens) to visit there, the site environments should be attractive to those who consider engaging in site walking and gardening. This research studied the presence of transitional-areas (e.g., side-yards and other areas relatively independent or semi-enclosed) and landscaping as motivators to older adults׳ physical activities. Moreover, the environments can be functional to physical activities if there are convenient paths connecting separated areas around the building. This study included the sum of connecting paths (defined as outdoor paths of at least 10 feet wide), presence of paving, canopy shading, and perceived walkability in the category of functionality factors. Along with the social factors of safety, the size of building setback and the distance from site entrance to the nearest street intersection were studied as physical environmental factors of safety.

Physical activities studied in this research included walking, gardening, yard work, and other outdoor physical activities on residential sites or properties. Physical activities were measured at high, medium and low levels, ranging from less than once every two days to at least twice per day for the frequency variable, and from less than ten minutes per occurrence to at least one hour per occurrence for the duration variable.

Data of this study were collected through survey and in Geographic Information Systems (GIS). A survey questionnaire was specially developed for this research. The draft questionnaire was refined after a pilot study conducted in an assisted-living facility in Bryan, TX in 2006. The 1st part of the questionnaire asked about participants׳ previous home address and the personal and social factors. The 2nd part collected data on participants׳ physical activities and perceived environmental features. Levels of perceived environmental features (e.g., safety) were scored in quartile, with 4th and 1st used to represent the highest and lowest level respectively. To control possible confounding variables such as different facility policies of entry admissions, research participants were recruited from one long-term care management system in Houston, TX. In this system, researchers conducted surveys in five assisted-living facilities. All the residents were invited and facility caregivers helped to screen participants to verify their cognitive competence for answering the survey questions. Participants were included only if they agreed to join the study. Response rates ranged from 25% to 30% in these facilities. Among the 110 participants, the average age was 84.2 years and 82% of them were female. Based on the survey data, 72 out of the 110 sample sites were single-family homes.

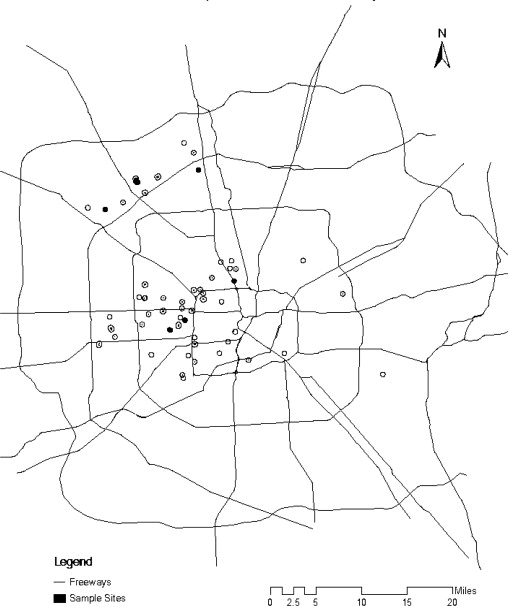

By geo-coding participants׳ mailing addresses in GIS, 57 of the 110 sites were identified in the area of Houston, TX (Appendix A ). By using GIS instruments, objective measures of environmental features on the 57 sites were collected. The data sources included the websites of the Geographic Information & Management System of Houston, the Harris County Appraisal District, the Houston- Galveston Area Council, the Texas Natural Resource Information System (TNRIS), the U.S. Geological Survey, the U.S. Census Bureau, and the Environmental Systems Research Institute. GIS layers applied in this study included Parcel, Parcel measure, Building footprint, Street outline, Freeway, Zip-code, DOQ (a digital mapping product with aerial photographs acquired in 2004), and Satellite photo (Figure 1 ).

|

|

|

Figure 1. Sample sites of apartment buildings. |

For quantitative data analyses, the Statistics Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 13.0) was applied. Bivariate correlations among variables were analyzed by t -test and Chi-square test. t -Tests are widely used to assess whether or not the means of two groups are statistically different from each other. Chi-square tests examine the association between two groups of variable as the row and column variables. Only one of the variables which were significantly correlated with each other (p <0.05, two tailed) was selected for multivariate analyses. Hierarchical linear regression models were applied to examine the value of physical environments on residential sites in predicting levels of older adults׳ physical activities. Hierarchical linear models also called multilevel regression models group the data into a hierarchy of regressions and widely used where the data have a natural hierarchical structure. With personal factors and social factors in the models, physical environmental factors were entered as the last block in modeling process. Both full models and nested models were applied. In full models, variables entered and their sequences of entering were decided by theoretical concerns. In nested models, the procedure itself selected predictor variables to enter the modeling by using the stepwise function of SPSS.

3. Results

Compared with less active participants, site walkability was rated significantly higher among the participants who had engaged in physical activities at least one time per day or at least ten minutes per occurrence (p <0.02) (Table 3 ). Residential sites were less likely reported being paved among the participants who had engaged in physical activities at least ten minutes per occurrence than less active participants (p <0.03). In full models entered with all test variables, the presence of transitional-areas on site was positively related to the duration of older adults׳ physical activities per occurrence (p <0.05). Without the variable of transitional-areas in full models, the variable of connecting-paths was positively associated with both the frequency of older adults׳ physical activities and the duration per occurrence (p <0.05).

| Yard activities | Site walkability (mean out of 4) | Sample size | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | |||

| At least 1 time/day | 3.0 | 61 | <0.02 |

| Less than 1 time/day | 2.71 | 48 | |

| Duration | |||

| At least 10 min/occurrence | 3.26 | 74 | <0.03 |

| Less than 10 min/occurrence | 2.57 | 35 |

Notes:'p -Value determines the significance of results in hypothesis tests; a small p -value (typically≤0.05) indicates strong evidence supporting the hypothesis. t -Tests are widely used to assess whether or not the means of two groups are statistically different from each other.

Age and building ownership were found to be positively related to the duration of physical activities per occurrence (p <0.05). Older participants who owned their previous residences were likely to have longer-lasting physical activities per occurrence than younger participants who rented their previous residences. Male reported higher levels of self-efficiency and environmental safety, and had more frequent physical activities than female (p <0.05). Participants in lower education levels had engaged in physical activities more frequently than participants in higher education levels (p <0.05).

4. Discussion

The following discussion utilizes the hypotheses and findings from this study to generate some preliminary guidelines for designing residential sites for older adults. These guidelines can be further tested in future studies. Early in the design process of design and planning, appropriately dealing with issues of building orientation, ground plan, configuration, and placement has a significant impact on the quality of site environments.

4.1. Promoting environmental motivators

To promote physical activities, environmental motivators could be addressed by fine-grained spaces with transitional-areas and inviting landscap ing in the outdoor settings.

Along with landscaping, the presence of transitional-areas could improve the complexity of site environments. Complexity should be considered as a means of increasing the attractiveness of site environments. As most physical activities happening on residential sites are “staying-activities” among older adults, they have a lot of time to process detail. Similar to the complexity of streetscape, which can be expressed by the number of differences noticeable to pedestrians per unit time (Rapoport, 1987 ), the complexity of site environments could be expressed by the number of differences noticeable to older adults per unit time. To promote the complexity, the following design factors should be considered: appropriate building orientations, a ground plan in a multi-edge shape, and a proper placement of the main building in harmony with accessory buildings and existing environments.

4.2. Developing functional outdoor environments

Residential site environments should be senior-friendly and have features convenient to older adults׳ physical activities, such as walkable areas, continuous walking paths, and good areas for gardening. Designers should consider placing the building properly on the site, applying a relative slim ground plan along the long axis of site, making a transparent building part or other mid-spaces connecting the front and back areas around the building, and keeping some sunny areas unpaved for gardening.

Walkable environments support physical activities (Cunningham and Michael, 2004 ; Suminski et al ., 2005 ). Having high-quality landscaping in the yard or on the property may make site walking and other physical activities there enjoyable. People may then feel the environments walkable. Reported by participants in this study, parcel sizes and lot coverages were not significantly associated with levels of perceived site walkability.

Measured in GIS by analyzing parcel data and satellite photos, the sum of connecting-paths around the building was found to be positively associated with physical activities among older adults. Connecting-paths allow older adults opportunities to pass different outdoor spaces while traversing the site. To save side-areas for connecting-paths, building ground plans in relatively slim shapes along the long axis of site should be considered. To improve the attractiveness of side-areas, side-porches are suggested. Also suggested include transparent porches or other mid-spaces linking separated buildings, building parts, and spaces.

Un-paved areas in the yard or on the property may provide older adults opportunities to do gardening if they wish. Fifty-one percent of the participants did gardening on their former residential sites. Among the active participants who had engaged in physical activities at least ten minutes per occurrence, paving was less likely to be reported (p <0.03). More research is needed to investigate the relationship between paving and physical activities.

In this research, both the distance from site entrance to the nearest street intersection and the size of building setback were not related to levels of physical activities. The safety from traffic and crime was rated high (3 out of 4 on average). In the surveys, participants seemed to feel confident about their security on former residential sites and most of them reported good health situations when living there.

This research has limits. As the majority of participants were women and the majority of sample sites were single family homes, the findings may better predict the physical activities among older women living in single family houses than those in other population groups. Barely half of the sample sites had no GIS measures due to limited data availability and quality. In addition, recall accuracy may limit the power of research as the survey questions required recalling of past behaviors and perceptions. However, the issues of recall difficulty had been carefully examined in previous research and the survey results were found to hold sufficient validity for the purpose of this study (Wang and Lee, 2010 ).

Future studies should enlarge the sample size and use higher-quality GIS data. Characteristics of neighborhood environments, such as land-use mix and population density, should be considered in predicting physical activities of older adults in residential site environments. Field trips to selected sample sites are suggested to collect first-hand data on the nearby outdoor environments.

Appendix A. Location of sample sites in GIS – Harris County, TX.

References

- Brasche and Bischof, 2005 S. Brasche, W. Bischof; Daily time spent indoors in German homes – baseline data for the assessment of indoor exposure of German occupants; Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health, 208 (4) (2005), pp. 247–253

- CDC, 1996 CDC; A Report from the Surgeon General: Physical Activity and Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA (1996)

- Cunningham and Michael, 2004 G.O. Cunningham, Y.L. Michael; Concepts guiding the study of the impact of the built environment on physical activity for older adults: a review of literature; Am. J. Health Promot., 18 (6) (2004), pp. 435–443

- DHHS, 1996 DHHS; A Report of the Surgeon General: Physical Activity and Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA (1996)

- DHHS, 2001 DHHS; Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health (2nd ed.), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA (2001)

- FIFARS, 2004 FIFARS; Older Americans 2004: Key Indicators of Well-Being, U.S. Government Printing Office, Federal Interagency Forum on Aging Related Statistics, Washington, DC (2004)

- FIFAS, 2012 FIFAS; Older Americans 2004: key Indicators of Well-Being, U.S. Government Printing Office, Federal Interagency Forum on Aging Related Statistics, Washington DC (2012)

- Humpel et al., 2002 N. Humpel, N. Owen, E. Leslie; Environmental factors associated with adults׳ participation in physical activity – a review; Am. J. Prev. Med., 22 (3) (2002), pp. 188–198

- Kinsella and Velkoff, 2001 K. Kinsella, V.A. Velkoff; An Aging World: 2001, US Census Bureau, Washington, DC (2001) (Series P95/01-1)

- Lawton, 1985 M.P. Lawton; The elderly in context: perspectives from environmental psychology and gerontology; Environ. Behav., 17 (1985), pp. 501–519

- Lawton, 1989 M.P. Lawton; Environmental proactivity and affect in older people; S. Spacapan, S. Oskamp (Eds.), Social Psychology of Aging, Sage, Newbury Park, CA (1989), pp. 135–164

- Lawton and Simon, 1968 M.P. Lawton, B. Simon; The ecology of social relationships in housing for the elderly; Gerontologist, 8 (1968), pp. 108–115

- Moss and Lawton, 1982 M. Moss, M.P. Lawton; Time budgets of older people: a window on four life styles; J. Gerontol., 8 (1982), pp. 108–115

- Owen et al., 2004 N. Owen, N. Humpel, E. Leslie, J. Sallis; Understanding environmental influences on walking; Am. J. Prev. Med., 27 (2004), pp. 67–76

- Patterson and Chapman, 2004 P.K. Patterson, N.J. Chapman; Urban form and older residents׳ service use, walking, driving, quality of life, and neighborhood satisfaction; Am. J. Health Promot., 19 (1) (2004), pp. 45–82

- Rapoport, 1987 A. Rapoport; Pedestrian street use: culture and perception; A.V. Moudon (Ed.), Public Streets for Public use, Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York (1987), pp. 80–94

- Saelens et al., 2003 B.E. Saelens, J.F. Sallis, J.B. Black, D. Chen; Neighborhood-based differences in physical activity: an environment scale evaluation; Am. J. Public Health, 93 (9) (2003), pp. 1552–1558

- Suminski et al., 2005 R.R. Suminski, W.S.C. Posten, R.L. Petosa, E. Stevens, L.M. Katzemoyer; Features of the neighborhood environment and walking by U.S. adults; Am. J. Prev. Med., 28 (2) (2005), pp. 149–155

- Ulrich, 1991 R.S. Ulrich; Effect of interior design on wellness: theory and recent scientific research; J. Health Care Inter. Des., 3 (1991), pp. 97–109

- Wang et al., 2002 H.X. Wang, A. Karp, B. Windblad, L. Fratiglioni; Late-life engagement in social and leisure activities is associated with a decreased risk of dementia: a longitudinal study from the Kungsholmen project; Am. J. Epidemiol., 155 (12) (2002), pp. 1081–1087

- Wang and Lee, 2010 Z. Wang, C. Lee; Site and neighborhood environments for walking among older adults; Health & Place, 16 (6) (2010), pp. 1268–1279

- Wister, 2005 A.V. Wister; The built environment, health, and longevity: multi-level salutogenic and pathogenic pathways; J. Hous. Elder., 19 (2) (2005), pp. 49–70

- Zimring et al., 2005 C. Zimring, A. Joseph, G.L. Nicoll, S. Tsepas; Influences of building design and site design on physical activity, research and intervention opportunities; Am. J. Prev. Med., 28 (2S2) (2005), pp. 186–193

Notes

1. According to DHHS (1996) .

Document information

Published on 12/05/17

Submitted on 12/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?