1. Introduction

A significant challenge in the manufacturing of composite materials is process-induced distortions (PIDs), as cured components deviate from their nominal design geometries. These distortions arise from a complex combination of different factors, such as ply stacking sequence, thermal expansion mismatches, matrix shrinkage, or property evolution during curing. Consequently, the design and production processes require iterative refinements, involving multiple mould design modifications, manufacturing adjustments, and repeated curing cycles that demand considerable time, effort, material, energy and, ultimately, economic costs.

A promising strategy to reduce these challenges is the integration of numerical simulations capable of predicting PIDs [1, 2] into the design and manufacturing workflows. Widely adopted in industry, such simulations can reduce the number of costly design iterations. However, these simulations are often computationally intensive due to the multi-physics and multi-scale nature of the problem. This complexity makes implementation and design validation time-consuming and resource-intensive.

To address these issues, Machine Learning (ML) or surrogate models offer a viable alternative. Given the complex, interrelated parameters governing PIDs, surrogate models can effectively determine the influence of each parameter and predict distortions based on input data. Once trained, these models provide rapid and cost-efficient predictions, potentially reducing or eliminating the need for computationally-intensive numerical simulations on a regular basis in the design process. As a result, surrogate models can significantly accelerate the design and industrialization of composite components while reducing associated costs.

Nevertheless, the high sensitivity of PIDs to various manufacturing parameters, and the nearly infinite diversity of composite configurations, necessitates extensive training datasets for these ML tools. In response, the present work introduces a synthetic data generation framework that leverages High-Performance Computing (HPC) environments to simulate PIDs in composite material components. This framework is specifically designed to generate large datasets for training surrogate models, enabling accurate predictions of PIDs in L-shaped composite panels. It thereby demonstrates the feasibility of integrating HPC-driven multi-physics and multi-scale numerical simulations to develop surrogate models that predict PIDs in a fast, accurate, and computationally efficient manner.

2. Physical Modelling and Numerical Simulation Framework

The manufacturing process of composite components inherently involves a multi-physics problem containing heat transfer, curing kinetics, and solid mechanics. These phenomena are governed by a first-order ordinary differential equation (ODE) that describes the resin’s curing rate and two partial differential equations (PDEs): the heat equation (energy balance) and the linear momentum balance. These governing equations have been implemented within the Alya [3] framework, the HPC multi-physics finite element method (FEM) simulation code, and more specifically making use of the solid mechanics module [4] applied to composite materials [5].

2.1. Heat Transfer

The heat transfer problem is modelled by a transient orthotropic heat equation with an internal heat source representing the exothermic curing reaction, described by Eq. 1 and 2 respectively. The boundary conditions use a Robin (convective) formulation to prescribe a temperature and a heat transfer rate equivalent to the conditions of an autoclave during the curing cycle.

|

|

(1) |

where denotes density, is the specific heat capacity, T is the temperature, K is the orthotropic thermal conductivity of the composite, and is the internal heat source term.

|

|

(2) |

where is the density, is the resin reaction enthalpy, and the rate of cure of the resin.

2.2. Curing Kinetics

The curing process transforms the resin from a liquid to a solid state through a polymerization reaction. This reaction is typically modelled using the Kamal-Sourour formulation [6]. In the proposed framework, a modified Kamal-Sourour model with an additional polynomial correction is employed, as given by Eq. 3, which is an ODE that is solved using a 4th-order Runge-Kutta method.

|

|

(3) |

where is the degree of cure (0.0 , m and n are the reaction orders, and and are temperature-dependent parameters determined via the Arrhenius equation. The function , which captures the transition from kinetic to diffusion-controlled regimes, is defined by Eq. 4.

|

|

(4) |

where represents the diffusion coefficient, and represents the critical conversion at which transition occurs. This value is temperature-dependent and is fitted from isothermal DSC experiments using a 3rd-order polynomial as in Eq. 5.

|

|

(5) |

where are the fitting parameters.

2.3. Evolution of Material Properties

The framework incorporates various material properties of both fibers and resin for the 8552/AS4 material. Many parameters were obtained from the literature, some were obtained experimentally, and others, such as the resin’s chemical volumetric shrinkage coefficient, were estimated using a Morris sensitivity analysis with subsequent fitting to experimental results.

The resin properties evolve during the curing process. Their evolution is modelled using an intermediate hyperbolic tangent function fitted to experimental data as described by Eq. 6. Subsequently, resin properties such as Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio are computed using Eq. 7.

|

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

where denotes the Young’s modulus, stands for the Poisson’s ratio, the subscript stands for resin, subscript involves the glassy state of the resin, and subscript involves the rubbery state of the resin.

2.4. Micromechanical Homogenization

The homogenized mesoscale mechanical properties of a long fiber-reinforced unidirectional composite ply are determined using the micromechanics model by Bogetti and Gillespie [7]. This model derives effective ply properties from the individual microscale properties of the resin and fibres. The homogenized properties are then used for the mesoscale solid mechanics.

2.5. Mesoscale Mechanical Distortion

The mesoscale solid mechanics problem is formulated using a Total Lagrangian approach, which allows considering the nonlinear effects associated with large displacements and rotations from process-induced distortions in composite panels. Although large deformations are considered, the strain regime is assumed to be small, justifying the use of a Saint-Venant-Kirchhoff constitutive model. Both elastic and inelastic deformations are captured via a multiplicative decomposition of the deformation gradient tensor [8]. The solid mechanics problem is governed by the balance of linear momentum PDE in the equilibrium case, described by Eq. 8.

|

|

(8) |

where indicates the divergence in the reference configuration, is the First Piola-Kirchhoff stress tensor, and are the body forces in the reference configuration.

2.6. Multiphysics Coupling

A strong two-way coupling exists between the heat transfer and curing kinetics problems, as the internal heat generation depends on the degree of cure, which in turn is temperature-dependent. An iterative coupling scheme is employed to solve these two problems simultaneously until convergence is reached, yielding consistent temperature and degree of cure fields. Based on these results, the evolving mechanical properties are computed and homogenized. In contrast, the solid mechanics problem is treated as one-way coupled, under the assumption that mechanical deformation does not significantly influence the thermal or kinetic responses. As a result, the mechanical analysis is performed sequentially, following the resolution of the heat transfer and curing kinetics problems.

3. Experimental Verification of the Numerical Framework

The proposed numerical simulation framework has been validated against multiple experimentally manufactured panels. In the initial test, a 400 x 400 mm flat panel with 11 layers in a [45/0/ -45/ -45/90/0/90/45/45/0/45] stacking sequence was manufactured using 8552/AS4 material. A Morris sensitivity analysis revealed that the resin’s chemical volumetric shrinkage coefficient significantly influences the model output. Although its initial value was obtained from the literature, a manual fine-tuning of this parameter was performed, resulting in simulation predictions that closely matched the experimental results.

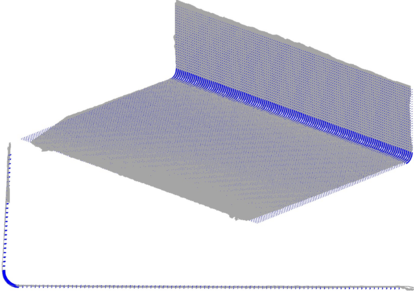

Subsequent blind tests on additional panels provided good results with the previously calibrated framework. For instance, an L-shaped panel (400 × 400 mm) with 100 mm and 300 mm wings was produced using an 8-layer laminate with a [0/90/0/90/90/0/90/0] stacking configuration. A comparison between the experimental measurements and the blind-test simulation results is illustrated in Fig. 1 and demonstrates a high degree of correlation.

These and other experimental verifications confirm that the numerical framework is a robust foundation for generating synthetic datasets via physics-based numerical simulations for training ML models.

4. Data Generation Workflow

Synthetic data generation in HPC infrastructures must rely on task parallelisation to accelerate workflows and address complex, multidisciplinary challenges. While HPC offers significant performance advantages, major difficulties often arise during setup and deployment, particularly in AI-focused applications that require autonomous and robust workflows. To address these issues, the proposed data generation workflow has been implemented using Python COMP Superscalar (PyCOMPSs) [9], a task-based parallel programming model that enables dynamic execution across distributed resources. This approach provides an HPC-native framework that maximises infrastructure utilisation while minimising human intervention during data generation.

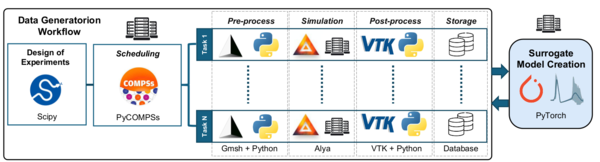

Figure 2 shows a representation of the synthetic task-based workflow created for the data generation of curing distortion simulations. The workflow begins with an initial sequential stage in which a design of experiments is constructed, efficiently exploring the solution space using, for example, the Latin Hypercube Sampling technique available in the SciPy library. Once the parameter sets are defined, a scheduling phase is executed in which PyCOMPSs orchestrates the parallel execution of all tasks across the HPC infrastructure, distributing the allocated resources efficiently. Each of these tasks consists of the typical phases of a numerical simulation: (i) a pre-processing stage where the numerical model is prepared, including mesh generation using Gmsh, definition of boundary conditions, material properties, and simulation parameters; (ii) a simulation stage where a single run is executed using Alya, leveraging the HPC resources provisioned and managed by the orchestrator to ensure optimal efficiency; (iii) a post-processing stage where the variables of interest are extracted using Python scripting with the VTK library; and (iv) a storage stage where results are saved in a standardised format for further use. The figure also illustrates how this workflow can interface with an AI-driven framework through one or multiple integration points, depending on the specific requirements of the application.

5. Case Study: L-shaped Panel Distortion Prediction with ML

This case study demonstrates how the proposed synthetic data generator, deployed on an HPC platform, can produce a representative training dataset for surrogate models. Once trained, these surrogate models are capable of accurately and rapidly predicting process-induced distortions in L-shaped panels.

5.1. Geometry and Material Properties

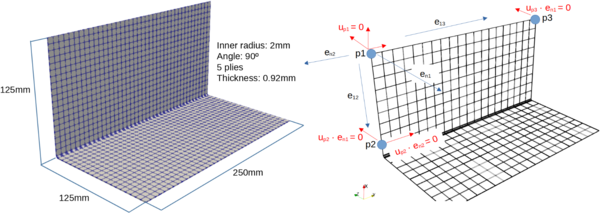

The study employs an L-shaped panel as the test geometry, with dimensions illustrated in Fig. 3. The material characteristics used in the simulation correspond to the 8552/AS4 composite. To ensure numerical accuracy and minimize locking effects, multiple geometric convergence tests have been performed, resulting in a mesh composed of HEX27 quadratic elements. In the wing sections of the panel, the mesh elements have dimensions of 6.25mm x 6.25mm x 0.184mm. For the curved region, element dimensions vary from 0.63mm to 0.92mm in the radial direction, while maintaining 6.25mm x 0.184mm in the other dimensions, to accurately capture the geometry.

The boundary conditions applied to the model serve to constrain the rigid-body motions while allowing for free deformation of the panel, as depicted in Fig. 3.

5.2. Synthetic Data and Surrogate Model

Using the L-shaped panel geometry, and the proposed dataset generation workflow, a dataset has been generated and a surrogate model has been trained to exemplify the applicability of the proposed framework.

To ensure a manageable yet representative input space, the stacking sequences have been restricted to five plies, with ply orientations sampled from –90° to 90° in 15° increments, capturing the most commonly used angles in composite design. This choice reflects a representative subset of typical layup configurations used in practice, balancing model complexity with sufficient variability to capture meaningful deformation behaviour during curing. The dataset is composed of 4000 samples. These samples were generated using 80 nodes of the General Partition of MareNostrum 5, equipped with Intel Sapphire Rapids processors offering 112 cores per node. PyCOMPSs orchestrated a total of 80 tasks running in parallel, each employing 56 MPI processes to ensure sufficient memory availability for the direct solver. The full data generation process took approximately 10 hours and 20 minutes.

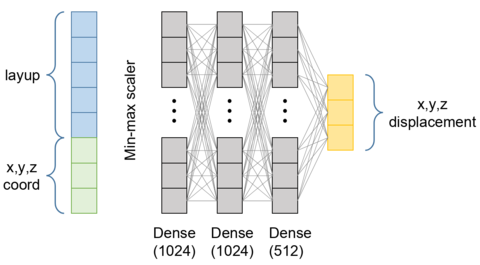

The presented surrogate model is a fully connected multilayer perceptron (MLP) comprising four linear layers, as shown in Figure 4. The input layer takes an 8-dimensional feature vector: the first 5 represent the stacking sequence of the laminate, while the last 3 correspond to the spatial coordinates of the point at which the displacement is evaluated. The input feature vector is normalized using min-max scaling to ensure consistent feature magnitudes and improve training stability.This is followed by two hidden layers with 1024 neurons each, and one with 512 neurons, all using linear transformations. The output layer produces a 3-dimensional displacement vector. The model is trained using mean squared error (MSE) loss to regress the displacement field. A total of 1.5 million parameters are used in the model.

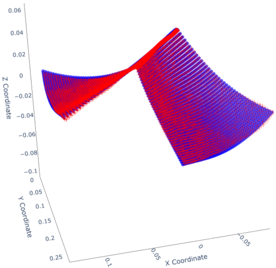

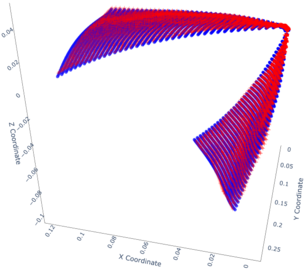

The model has been trained using the Adam optimizer with a batch size of 4096 and a learning rate of . Training was conducted across 3 NVIDIA H100 GPUs to leverage parallel processing for enhanced performance. Figure 5 presents a comparison of the displacement fields for two layups. Both predictions demonstrate strong agreement with the FEM results. The blue colour represents the original FEM data, while the red colour corresponds to the predictions.

|

|

| (a) [-15, -45, 60, 30, 60] | (b)[-45, 90, -90, 15, 30] |

6. Discussion and Conclusions

A synthetic data generation tool has been developed based on a multi-physics numerical simulation framework implemented in Alya, and orchestrated via PyCOMPSs to leverage high-performance computing (HPC) capabilities. This framework enables the generation of large datasets of PIDs simulations in composite panels. Specifically, a training dataset comprising 4000 simulations of L-shaped composite panels was generated and used to train a surrogate model aimed at providing fast and accurate PID predictions.

The surrogate model, a fully connected multilayer perceptron (MLP) with four linear layers, demonstrated good predictive capability, reproducing displacement fields comparable to those obtained via full finite element method (FEM) simulations using the proposed numerical framework.

This work shows that synthetic data generation pipelines, based on high-fidelity numerical simulations and supported by HPC resources, can produce large and high-quality datasets suitable for training surrogate models. These models could significantly reduce the reliance on time-consuming and computationally expensive FEM simulations during the design phase of composite components, accelerating design iterations and reducing associated costs and resource usage.

Future work will aim to extend the tool’s scope by incorporating variable ply counts and diverse stacking sequences to enhance general applicability. Additionally, introducing variability in material properties, such as resin and fiber characteristics and processing parameters, could enable the simulation of material and process uncertainty. Improvements to the surrogate model could also be explored, including alternative ML architectures and strategies, with the goal of further enhancing prediction accuracy and generalization.

7. Acknowledgements

This work has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No. 101056682 (DIDEAROT project). A. Quintanas-Corominas was supported by the “Generación D” initiative, Red.es, Ministerio para la Transformación Digital y de la Función Pública, for talent attraction (C005/24-ED CV1), funded by the European Union’s NextGenerationEU program through the PRTR. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

The authors would like to acknowledge Isabel Harismendy Ramirez De Arellano and Mildred Puerto from TECNALIA for providing the experimental data used in this work, within the context of the DIDEAROT project.

8. References

[1] Brauner, C., Bauer, S., & Herrmann, A. S. (2015). Analysing process‑induced deformation and stresses using a simulated manufacturing process for composite multispar flaps. Journal of Composite Materials, 49(4), 387–402. DOI: 10.1177/0021998313519281.

[2] Traiforos, N., Turner, T., Runeberg, P., Fernass, D., Chronopoulos, D., Glock, F., Schuhmacher, G., & Hartung, D. (2021). A simulation framework for predicting process‐induced distortions for precise manufacturing of aerospace thermoset composites. Composite Structures, 275, 114465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2021.114465.

[3] M. Vázquez, G. Houzeaux, S. Koric, A. Artigues, J. Aguado‑Sierra, R. Arís, D. Mira, H. Calmet, F. Cucchietti, H. Owen, A. Taha, E. D. Burness, J. M. Cela y M. Valero, «Alya: Multiphysics engineering simulation toward exascale,» Journal of Computational Science, vol. 14, pp. 15–27, 2016. DOI: 10.1016/j.jocs.2015.12.007.

[4] Casoni, E., Jérusalem, A., Samaniego, C., Eguzkitza, B., Lafortune, P., Tjahjanto, D. D., Sáez, X., Houzeaux, G., & Vázquez, M. (2015). Alya: Computational Solid Mechanics for Supercomputers. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering, 22(4), 557–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-014-9126-8.

[5] Quintanas‑Corominas, A., Maimí, P., Casoni, E., Turon, A., Mayugo, J. A., Guillamet, G., & Vázquez, M. (2018). A 3D transversally isotropic constitutive model for advanced composites implemented in a high performance computing code. European Journal of Mechanics – A/Solids, 71, 278–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euromechsol.2018.03.021.

[6] Kamal, M. R. & Sourour, S. “Kinetics and thermal characterization of thermoset cure,” Polymer Engineering and Science, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 59–64, 1973. DOI: 10.1002/PEN.760130110.

[7] Bogetti, T. A. & Gillespie Jr, J. W. “Process‑Induced Stress and Deformation in Thick‑Section Thermoset Composite Laminates,” Journal of Composite Materials, vol. 26, nº 5, pp. 626–660, 1992. DOI: 10.1177/002199839202600502.

[8] Vujošević, L. & Lubarda, V. A. “Finite‑strain thermoelasticity based on multiplicative decomposition of deformation gradient,” Theoretical and Applied Mechanics, vol. 28‑29, pp. 379–399, 2002. DOI: 10.2298/TAM0229379V.

[9] PyCOMPSs: Parallel computational workflows in Python, Enric Tejedor, Yolanda Becerra, Guillem Alomar, Anna Queralt, Rosa M. Badia, Jordi Torres, Toni Cortes, Jesús Labarta, IJHPCA 31(1): 66-82 (2017), DOI: 10.1177/1094342015594678

Document information

Accepted on 26/06/25

Submitted on 09/05/25

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?