1. Introduction

Multilayered composite and sandwich structures have been widely used in different engineering fields, including aerospace, marine, civil, energy, and automotive, thanks to their specific and attractive properties. Generally, they combine different materials to enhance the mechanical properties such as high strength-to-weight ratio, good fatigue properties and tailorability [1]. However, the variation of the mechanical properties along the thickness-wise direction leads to a more pronounced transverse anisotropy and transverse shear and normal deformability. This might lead to catastrophic failures such as debonding and delamination in the worst-case scenario. To correctly describe their complex behaviour, a three-dimensional solution of the elasticity problem is desirable, but from a mathematical point of view, this can be done only for a limited combination of load, boundary conditions, and laminate lay-up [2–4]. For other cases, 3D finite elements can be adopted to obtain an accurate and reliable solution, but for more complex structures requiring a large number of elements, this methodology increases the computational cost. Approximated models such as Equivalent Single Layer (ESL) and Layer-Wise theories have often been adopted to describe the structural response of multilayered composite and sandwich structures. For instance, the ESL ones are computationally attractive since the displacement field is generally described by a limited number of kinematic variables [5]. Among them are worthy to be cited the Kirchhoff plate theory, the Reissner-Mindlin plate model and Reddy’s Third order shear deformation theory. Although accurate in predicting global quantities such as maximum displacement, frequencies and buckling loads, they are more inaccurate in through-the-thickness displacement, strain and stress predictions. This inaccuracy is higher for highly heterogenous or thicker multilayered structures. Conversely, the LW models [6] assume a displacement field for each lamina. This approach increases the model’s predictivity, improving displacement and stress predictions, but in structures with several layers, the computational cost becomes relevant and limiting. Between the computational advantages of ESL and the accuracy achieved with the LW ones, the ZigZag Theories (ZZTs) represent an alternative approach to describe the structural behaviour of multilayered composite and sandwich structures [7]. The displacement field of ZZTs is generally described as a superposition of two contributions: the global one, which gives a general description of the whole laminate with few kinematic variables (such as the ESL one), and a local refinement characterized by appropriate through-the-thickness functions, i.e. the “zigzag function”, that takes into account of the layer-wise effect of material variation. In contrast with the Reissner-Mindlin model, the ZZTs do not require any shear correction factor to evaluate the transverse shear deformability correctly. Different approaches have been developed in the literature to characterize the zigzag contribution: geometrically based, such as Murakami [8], or physically based, such as Di Sciuva [9]. The latter approach has been demonstrated as the more adequate to obtain accurate results. Among the most recent formulations, the Refined Zigzag Theory developed by Tessler and co-workers [10,11] has demonstrated its accuracy and numerical efficiency in different case scenarios, including non-linear analysis, [12] Functionally Graded materials [13], Iso-Geometric Analysis [14], and structural monitoring [15,16]. Moreover, higher-order and mixed-variational formulations have been implemented to address thicker multilayered structures and improve the stress-field predictions, see for instance Refs. [17–20]. It should be remarked that the RZT cannot address angle-ply lamination cases since, in the formulation of the zigzag functions, the shear coupling typical of general anisotropic structures is not addressed. The recently enhanced-RZT (en-RZT) [21] takes into account this coupling effect thanks to two additional zigzag functions. This work briefly presents the recent formulation of an efficient finite element for the analysis of multilayered composite sandwich structures [22] and a numerical assessment with 3D reference solution to highlight the major advantages and relative limitations. Some remarks and possible future perspectives are presented in the conclusion section.

2. The en-RZT: theoretical background and finite element formulation

Let us consider a multilayered flat plate made of N perfectly bonded layers. Assuming as V the plate volume, h the whole thickness, the points of the plate are referred to an orthogonal Cartesian coordinate system where are the in-plane coordinates of the reference surface, here referred with Ω. The reference plane is chosen to be the middle plane of the plate, so that . The superscript is used to indicate the quantities corresponding to the kth-layer (with k=1,…,N), whereas the subscript denotes the quantity evaluated at the kth-interface between the kth and the (k-1)th layer (with k=1,…,N).

The displacement field of the en-RZT can be described as follows:

|

|

(1) |

where , and are the orthogonal components of the displacement vector along the coordinate. In the en-RZT the transverse displacement is assumed constant along the thickness. The are the uniform in-plane displacements, the average bending rotation, and the zigzag rotations. The matrix is the set of the through-the-thickness piecewise continuous zigzag functions. They are characterized by the partial enforcement of the transverse shear continuity at the layer interfaces, and the vanish condition of these functions on the bottom and top external surfaces of the plate, i.e. . According to Ref. [21] their expression reads:

|

|

(2) |

where the zigzag slopes are defined as follows:

|

|

(3) |

with the symmetric matrix of the transverse shear compliant coefficients of the kth-layer.

Assuming the linear strain-displacement relations, the strain in-plane ( ) and transverse strain ( ) components follow:

|

|

(4) |

where

|

|

(5) |

|

|

(6) |

|

|

(7) |

It should be noted that in Eq. (4), for general lamination schemes, is a full matrix. Thus, the transverse shear strain components and , are influenced by both zigzag rotations.

The linear elastic constitutive relations for plane stress condition can be written as follows:

|

|

(8) |

where and are the in-plane and transverse shear stress components, respectively. Moreover, and are, respectively, the in-plane reduced and transverse shear elastic stiffness coefficients of the kth layer expressed in the plate axes.

The governing equations and variationally consistent boundary conditions can be derived using the d’Alembert principle. It reads:

|

|

(9) |

In Eq. (9), denoting with the variational operator, appear (from left to the right) the virtual variation of the inertia forces, the virtual variation of the internal work and the virtual variation of the external works.

For general plate problems, a robust and efficient finite element formulation can be used. The kinematic variables of a generic quadrilateral element (e), i.e. , can be approximated by using the anisoparametric constrained interpolation strategy. This procedure, originally developed for Mindlin-based elements, has also been applied for RZT-based formulation to manage the shear-locking problem. In this scheme, the transverse displacement is interpolated using polynomials with one degree higher than those used for the other kinematic variables. The additional mid-edge nodes required for this interpolation are then condensed out by enforcing the following condition along the element edges (s is the local edge coordinate), i.e. . It results:

|

|

(10) |

where

|

|

(11) |

and

|

|

(12) |

are the shape functions for quadrilateral element. Moreover, are the coordinates in the element natural plane. Besides the anisoparametric constrained interpolation strategy, an appropriate element shear correction (ESC) factor can be introduced to better address the element energy balancing between the bending and transverse shear contributions that cause the shear-locking problem in ultra-thin regimes. Denoting it with , according to its definition, is inverse proportionally to the ratio between the trace of the shear and the bending matrices that form the elemental stiffness matrix. In thick regimens, where the shear locking is not relevant, the ESC factor tends to the unity, whereas in thinner ones, it has very low values closer to 0. The ESC factor is used to correct only the element constitutive en-RZT relations at the level of shear stiffness. In the enRZT-Q4c element full integration (3x3 gauss points) is adopted. For more details, see the whole formulation in Refs [22,23].

3. Numerical assessment

In this section, a brief numerical assessment is presented to highlight the capabilities of the en-RZT finite element to evaluate the static and dynamic response of a multilayered composite and sandwich structure. For this purpose, a rectangular angle-ply anti-symmetric sandwich plate (S) is considered, with a=8 mm, b=4 mm and thickness h=1 mm. The face-sheets are made of a CFRP material, whereas the core is made of Rohacell® WF110 foam. Material properties and lamination stacking sequence are reported in Table 1 and Table 2.

| Material name | E1 [GPa] | E2=E3 [GPa] | ν12= ν13= ν23 | G12=G13 [GPa] | G23 [GPa] | ρ [kg/m3] |

| A | 175 | 7 | 0.25 | 3.5 | 1.4 | 1000 |

| Core | 0.194 | 0.194 | 0.45 | 0.067 | 0.067 | 110 |

| Laminate name | Lamina materials | Normalized thickness h(k)/h | Orientation [deg] |

| S | [A/A/Core/A/A] | [0.125/0.125/0.5/0.125/0.125] | [-30/45/0/-45/30] |

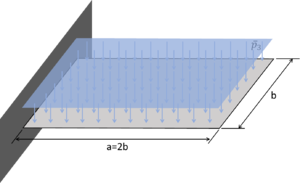

A 3D reference solution has been obtained using the MSC Patran/Nastran software, where HEXA20 solid elements are used to solve this problem. More specifically, 80 elements are along x1 direction, 40 along x2 one and 16 elements along the thickness, which results in 661299 dofs. The anti-symmetric angle-ply sandwich plate is clamped on one side, whereas a uniform load pressure is applied on the top and bottom surface, i.e. where , in order to reduce the effect of transverse normal deformability that cannot be addressed by the present en-RZT model. A scheme of the problem is provided in Figure 1.

The en-RZT model of the sandwich plate is made of 80x40 elements along x1 and x2, respectively, with a total number of dofs 23247, nearly thirty times less than those present in the high-fidelity 3D Nastran model. Hereafter are presented the results concerning the static bending analysis in terms of through-the-thickness distributions of displacements and strains.

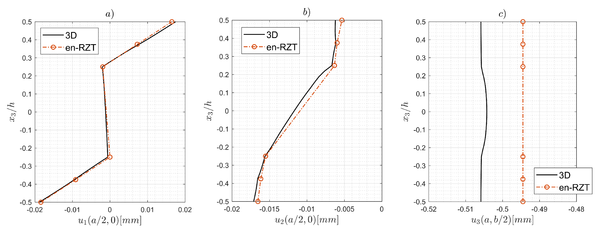

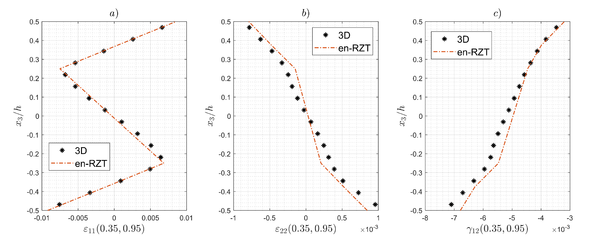

According to Figure 2, the through-the-thickness distributions of the in-plane displacements are in good agreement with the 3D ones. Although there are some discrepancies, the percent error of the transverse displacement with respect to the average 3D value is -2.14 %. Higher errors are observed in the core layer due to the intrinsic limitation of the en-RZT linear displacement field. Figure 3 reports the through-the-thickness distribution of the in-plane strains. The en-RZT results are able to follow, in some cases with remarkable accuracy, the 3D strain distributions. Again, the differences that are present, especially in the core layer, are mainly due to the limitation of the current linear model for in-plane displacements, and the assumption of neglecting the transverse normal deformability.

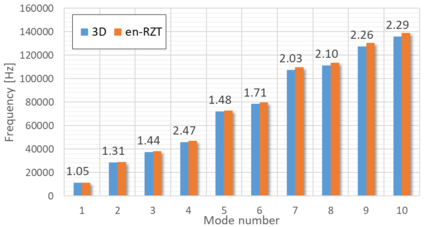

A free vibration analysis on the anti-symmetric angle-ply sandwich rectangular plate has been conducted to evaluate the en-RZT predictive capability for dynamic problems. The first 10 natural frequencies of sandwich S are computed using the same model for static analysis and the results are compared with those obtained using the 3D Nastran model and reported in Figure 4. The selected frequencies are for both flexural and torsional modes. Additionally, for each mode, the percent error on the en-RZT frequency with respect to the 3D one is also reported. It is worth noting that the en-RZT shows a remarkable accuracy in predicting the frequency even at higher modes, with an error that does not exceed 2.3 %. These results confirm the accuracy of the en-RZT model in making accurate predictions for static and dynamic problems at an affordable computational cost.

4. Conclusions

This work has briefly presented a general overview of the recent advancements on the refined zigzag model for analyzing multilayered composite and sandwich plates. Focusing on the enhanced-Refined Zigzag Theory (en-RZT) its formulation and finite element implementation have been described. The en-RZT is capable, thanks to the set of zigzag functions to address the shear coupling typically present in multilayered anisotropic laminates. Moreover, the en-RZT only requires C0-continuous functions to formulate simple and efficient finite elements. The shear-locking problem is solved by using anisoparametric interpolation strategy in conjunction with an element-based correction factor. A numerical assessment is presented to highlight the present theory's advantages and limitations. The en-RZT confirms its remarkable accuracy in addressing static and dynamic problems, obtaining accurate through-the-thickness distributions of displacements and strains. In modal analysis, remarkable accuracy is achieved by the en-RZT, even for higher frequencies. Moreover, the computational cost required by the en-RZT is very little if compared with that necessary for 3D models. Some limitations in the accuracy have been observed, mainly due to the linear displacement field assumed in this model that the core layer is not enough to predict the more complex behaviour. In fact, higher-order zigzag models are more suitable for thicker structures; these are not directly addressed in this work but are available in the available literature. However, the simplicity and computational attractiveness of the en-RZT might open some future perspectives, including multi-scale problems, dynamic response, non-linear material behaviour (such as 3D printed materials) and optimization problems.

5. Bibliography

[1] D.K. Rajak, D.D. Pagar, R. Kumar and C.I. Pruncu, “Recent progress of reinforcement materials: a comprehensive overview of composite materials”, Journal of Materials Research and Technology, vol. 8, 2019, pp. 6354–6374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2019.09.068.

[2] N.J. Pagano, “Exact Solutions for Rectangular Bidirectional Composites and Sandwich Plates”, Journal of Composite Materials, vol. 4, 1970, pp. 20–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/002199837000400102.

[3] N.J. Pagano, “Influence of Shear Coupling in Cylindrical. Bending of Anisotropic Laminates”, Journal of Composite Materials, vol. 4, 1970, pp. 330–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/002199837000400305.

[4] A.K. Noor and W.S. Burton, “Three-Dimensional Solutions for Antisymmetrically Laminated Anisotropic Plates”, Journal of Applied Mechanics, vol. 57, 1990, pp. 182–188. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.2888300.

[5] S. Abrate and M. Di Sciuva, “Equivalent single layer theories for composite and sandwich structures: A review”, Composite Structures, vol. 179, 2017, pp. 482–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2017.07.090.

[6] K.M. Liew, Z.Z. Pan and L.W. Zhang, “An overview of layerwise theories for composite laminates and structures: Development, numerical implementation and application”, Composite Structures, vol. 216, 2019, pp. 240–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2019.02.074.

[7] M. Di Sciuva and M. Sorrenti, “New Accomplishments on the Equivalence of the First-Order Displacement-Based Zigzag Theories through a Unified Formulation”, Journal of Composite Science, vol. 8, 2024, pp. 1–33. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs8050181.

[8] H. Murakami, “Laminated Composite Plate Theory With Improved In-Plane Responses”, Journal of Applied Mechanics, vol. 53, 1986, pp. 661–666. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3171828.

[9] M. Di Sciuva, “Development of an anisotropic, multilayered, shear-deformable rectangular plate element”, Computers & Structures, vol. 21, 1985, pp. 789–796. https://doi.org/10.1016/0045-7949(85)90155-5.

[10] A. Tessler, M. Di Sciuva and M. Gherlone, “Refinement of Timoshenko Beam Theory for Composite and Sandwich Beams using Zigzag Kinematics”, NASA/TP-2007-215086, 2007, pp. 1–45. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20070035078.

[11] A. Tessler, M. Di Sciuva and M. Gherlone, “Refined Zigzag Theory for Laminated Composite and Sandwich Plates”, NASA/TP-2009-215561, 2009, pp. 1–53. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20090007494

[12] A. Ascione, M. Gherlone and A.C. Orifici, “Nonlinear static analysis of composite beams with piezoelectric actuator patches using the Refined Zigzag Theory”, Composite Structures, vol. 282, 2022, pp. 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2021.115018.

[13] L. Iurlaro, M. Gherlone and M. Di Sciuva, “Bending and free vibration analysis of functionally graded sandwich plates using the Refined Zigzag Theory”, Journal of Sandwich Structures & Materials, vol. 16, 2014, pp. 669–699. https://doi.org/10.1177/1099636214548618.

[14] K.A. Hasim and A. Kefal, “Isogeometric static analysis of laminated plates with curvilinear fibers based on Refined Zigzag Theory”, Composite Structures, vol. 256, 2021, pp. 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.113097.

[15] A. Kefal and A. Tessler, “Delamination damage identification in composite shell structures based on Inverse Finite Element Method and Refined Zigzag Theory”, in: J. Amdahl and C.G. Soares (Eds.), Developments in the Analysis and Design of Marine Structures, Taylor & Francis Group, London, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003230373-41.

[16] A. Kefal, I.E. Tabrizi, M. Yildiz and A. Tessler, “A smoothed iFEM approach for efficient shape-sensing applications: Numerical and experimental validation on composite structures”, Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, vol. 152, 2021, pp. 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2020.107486.

[17] R.M.J. Groh and P.M. Weaver, “A computationally efficient 2D model for inherently equilibrated 3D stress predictions in heterogeneous laminated plates. Part I: Model formulation”, Composite Structures, vol. 156, 2016, pp. 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2015.11.078.

[18] A. Kutlu, “Mixed finite element formulation for bending of laminated beams using the refined zigzag theory”, Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part L: Journal of Materials: Design and Applications, vol. 235, 2021, pp. 1712–1722. https://doi.org/10.1177/14644207211018839.

[19] M. Sorrenti and M. Gherlone, “Numerical and experimental predictions of the static behaviour of thick sandwich beams using a mixed {3,2}-RZT formulation”, Finite Elements in Analysis and Design, vol. 242, 2024, pp. 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.finel.2024.104267.

[20] H. Wimmer, A. Tessler and C. Celigoj, “Extended refined zigzag theory accounting for two-dimensional thermoelastic deformations in thick composite and sandwich beams”, Composite Structures, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2025.119076.

[21] M. Sorrenti and M. Di Sciuva, “An Enhancement of the Warping Shear Functions of Refined Zigzag Theory”, Journal of Applied Mechanics, vol. 88, 2021, pp. 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4050908.

[22] M. Sorrenti and M. Gherlone, “Robust TRIA3 and QUAD4 Finite Elements Based on the En-RZT Kinematics for the Analysis of General Anisotropic Multilayered Composite Plates”, Mechanics of Composite Materials, vol. 60, 2024, pp. 1001–1026. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11029-024-10241-y.

[23] M. Sorrenti, M. Di Sciuva and A. Tessler, “A robust four-node quadrilateral element for laminated composite and sandwich plates based on Refined Zigzag Theory”, Computers & Structures, vol. 242, 2021, pp. 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruc.2020.106369.

Document information

Accepted on 22/09/25

Submitted on 13/04/25

Licence: Other