1. Introduction

Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) refers to an approach for assessing the condition and integrity of a structure over time. It involves the continuous or periodic acquisition of data through a network of sensors that are either surface-mounted or embedded within the structural components. These sensors collect various types of physical or mechanical responses such as strain, vibration, or acoustic emissions which are then analyzed using signal processing and diagnostic algorithms. The ultimate goal of SHM is to assess structural conditions, and support informed decision-making related to maintenance, safety, and lifecycle management of infrastructure systems [1], [2].

One of the most promising techniques for SHM is guided wave (GW) SHM utilizing piezoceramic transducers (PCTs). This approach has evolved into a relatively mature technology in detecting damage or defects within structural components. Due to their ability to generate and detect guided elastic waves over long distances with minimal energy loss, PCT-based systems are particularly effective for continuous monitoring of large and complex structures. Their compact size, ease of integration, and compatibility with various signal processing methods have led to their use in the SHM of advanced composite materials commonly used in aerospace, automotive, and civil engineering sectors [2], [3].

However, scaling GW-based SHM system is hindered by the extra weight and complexity added by wires and connecting components [4]. A critical vulnerability in these systems lies in the intricate network that joins sensors to the interrogator unit. Traditionally, cables often made of copper serve as these connections, but they not only increase the overall weight of the system but also complicate cable management, particularly over large monitoring areas with extensive wiring. Moreover, the production of copper wiring is both cost-intensive and a complex process and prone to corrosion.

In response to these challenges, recent research has focused towards using printed circuits as an alternative to traditional cables. Early studies have demonstrated the feasibility of using silver ink to create conductive paths, showing promise in reducing weight and simplifying system design [4]. Others have used nanoparticle-doped epoxy with carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene nanoparticles (GNPs) as conductive paths for other applications because they are cheaper to produce and have high corrosion resistance [5].

This work explores the use of silver ink both in unmodified form and enhanced with carbon-based nanoparticles namely CNT and GNP, as well as carbon based nanoparticle-doped epoxy inks. The goal is to characterize and compare the electrical of these inks when used in printed conductive paths. By investigating different ink formulations, the study aims to identify lightweight, durable, and cost-effective alternatives to traditional wiring methods in SHM systems.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

The silver ink which is a syringe-printable paste was obtained from Dycotec Materials (UK). The carbon filler-based inks were prepared by dispersing CNTs and/or GNPs into Epolam 8052, (Axson Technologies, France). The CNTs used are multi-walled, known as NC7000TM from Nanocyl (Belgium), with an average diameter of 9.5 nm and a length of about 1.5 µm, supplied in powder form by XG Sciences (USA) having an average thickness of 6-8 nm and an average lateral size of 25 µm. Kapton was used as a substrate to print these inks.

The piezoelectric transducers were from supplied from PI Ceramic® (Lederhose, Germany). These are special transducers in which the piezoceramic is embedded in a polymer and a mechanical pre-compression is provided to form an “acoustic-ultrasonic composite transducer (AUCT) [6]”

2.2. Ink preparation and printing

The epoxy was initially mixed with carbon-based nanoparticles using manual blending, followed by the application of a calendering technique to achieve proper dispersion of the nanoparticles throughout the epoxy matrix. Five calendering cycles were carried out using a three-roll mill calendering machine. For the silver ink, however, nanoparticle dispersion was achieved using a sonication technique. Following the dispersion process, the silver ink was degassed to remove any trapped air bubbles, ensuring a smooth and consistent application during printing.

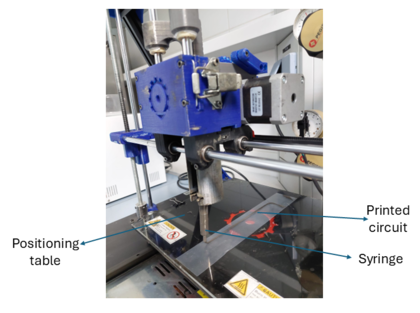

Both types of inks were printed using a BCN3D Plus 3D printer, equipped with a paste extruder module. A syringe attached to the extruder was used to deposit the conductive paths. The complete printing setup is illustrated in Figure 1. After printing, the nanoparticle-doped epoxy ink was initially cured at room temperature, followed by a post-curing step using Joule heating to enhance their mechanical and electrical properties [5]. The silver ink was sintered at 150 °C after printing.

2.3. Electric characterization and signal transmission

The electrical conductance of the printed circuits was evaluated using a source meter unit (KEITHLEY 2410, Ohio, USA). Conductance was determined by applying Ohm’s law by measuring the slope of the current-voltage (I-V) curve. For repeatability, a minimum of three samples were tested for each type of circuit across a voltage range of 0–10 V.

To assess the signal transmission performance of the printed circuits, GWs were transmitted and received using a National Instruments PXIe-1082 setup, with a three-pulse sine wave actuation signal featuring a Hanning window and a 3-Volt amplitude. As a baseline for comparison, initial signal measurements were taken using standard coaxial copper cables. The printed circuits were then introduced between the coaxial cables and the AUCTs, and the same signal measurements were repeated, as shown in Figure 2. This setup allowed any additional resistance or signal degradation introduced by the printed circuits to be directly reflected in the measurements, enabling reliable comparisons with traditional copper cables.

2.4. Film bonding by induction heating

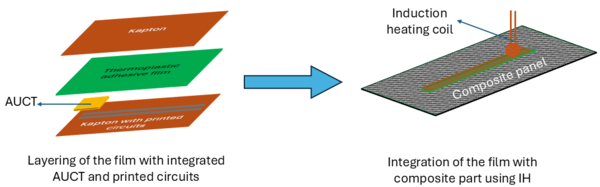

To demonstrate the practical application of printed circuits in developing lightweight, easily integrable SHM systems, a flexible multi-layered film was fabricated featuring integrated AUCTs and silver-based printed conductive paths. This film was successfully bonded to a CF-PEEK (HTA-40) thermoplastic composite panel using induction heating, a rapid and non-intrusive technique that enables localized bonding without the need for additional adhesives or mechanical fasteners [7].

The fabrication process of the film, along with its subsequent bonding using inductive heating, is illustrated in Figure 3. This method supports efficient, and scalable installation, making it highly suitable for automated or semi-automated manufacturing environments. By streamlining the integration process and minimizing system weight, this approach significantly enhances the practicality and industrial applicability of SHM systems, particularly in sectors such as aerospace, automotive, and wind energy.

3. Results

3.1. Weight comparison

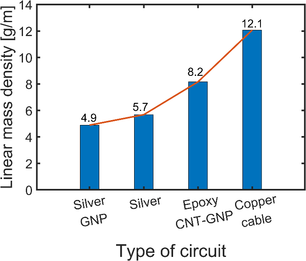

In Figure 4, the linear mass density of four different circuit materials are compared. Silver-GNP exhibits the lowest mass density, followed by silver. Copper cable has the highest linear mass density of the four materials. The graph suggests that silver-GNP and Epoxy CNT-GNP offer a significant reduction in linear mass density compared to traditional conductive materials such as copper cable. This reduction could be beneficial in applications where weight is critical, such as in aerospace. Additionally, while silver has a marginally higher density than silver-GNP, the differences between these materials imply that slight modifications in composition can influence the overall mass without necessarily compromising functionality.

3.2. Conductivity and signal transmission

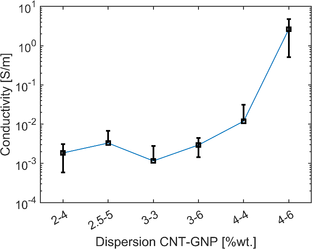

The electrical conductivity of the nanoparticle-doped epoxy inks as a function of filler weight fraction is shown in Figure 5. At low concentrations (approximately 2.4–4.4 %wt.), the conductivity increases modestly, indicating the formation of isolated conductive clusters that do not yet span the material. However, a pronounced enhancement is observed at around 4.6 %wt., marking the percolation threshold where a continuous, interconnected network of CNT-GNP is formed. This network formation results in a jump of nearly five orders of magnitude in conductivity, demonstrating the critical role of filler interconnectivity. The synergistic interaction between CNTs and GNPs appears to facilitate more effective electron transport pathways, as their combined geometries promote contact and bridging across the composite matrix.

Figure 5: Conductivity of CNT-GNP doped epoxy ink for different dispersions.

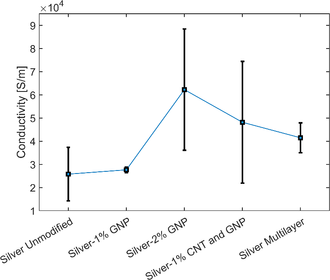

Figure 6 presents the electrical conductivity of several silver-based inks, both pure and modified with different nanoparticle loadings. The unmodified silver ink achieves a conductivity of approximately 2.58 × 10⁴ S/m, which increases significantly with the addition of nanomaterials. Incorporating 1 %wt. GNP increases the conductivity by roughly 7% over the baseline, whereas a 2 %wt. GNP modification boosts it to approximately 2.4 times the original value. In comparison, adding 1 %wt. CNT-GNP results in an increase to about 1.9 times the baseline conductivity, while the multilayer silver ink achieves a conductivity near 1.6 times that of the unmodified ink. Although the inclusion of CNT does enhance the conductivity, the improvement is lower than that observed with GNP alone. Microscopic examination of the printed circuits indicated that dispersing CNT uniformly within the silver ink is challenging, likely leading to less effective conductive network formation. This suggests that the superior performance of the GNP-modified inks is partly due to their more consistent dispersion, which facilitates better particle connectivity and, consequently, enhanced electron transport.

3.3. Signal transmission

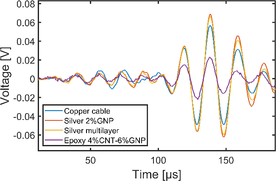

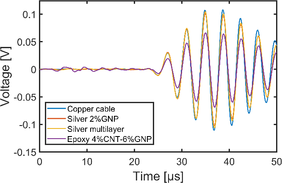

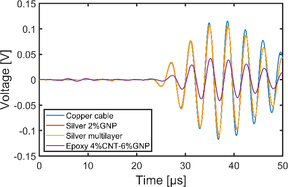

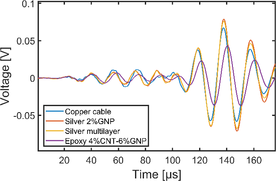

A comparative analysis of signal transmission for different interconnection configurations between AUCTs and GW generator and receiver equipment is presented in Figure 7. The results are presented for four ink types: silver ink containing 2 %wt. GNP, multilayered silver ink, and a nanoparticle-doped epoxy matrix incorporating 4 %wt. CNT and 6 %wt. GNP. The results are presented for two different frequencies 50 kHz and 250 kHz representing which represent cases where two fundamental modes namely A0 and S0 generally emerge for similar material, with similar layup and thickness [8]. The signals transmitted and received through both the copper cables and the silver-based printed circuits particularly incorporating GNPs exhibited nearly identical waveforms in terms of amplitude and signal fidelity. This indicates that silver-based printed circuits possess excellent transmission characteristics, closely matching those of traditional copper conductors, and thus represent a viable lightweight alternative for signal transmission. Notably, at the lower excitation frequency of 50 kHz, silver circuits demonstrated even higher signal amplitudes than copper cables in some configurations, underscoring their potential to enhance signal quality while reducing system weight. On the other hand, circuits fabricated with nanoparticle-doped epoxy also supported signal propagation but exhibited significantly higher resistive losses. Specifically, when the actuator–receiver configuration involved the epoxy-based printed circuit, the signal amplitude was reduced by a factor of approximately three at 50 kHz when the circuit served as a receiver, and by a factor of two when acting as an actuator. Interestingly, this behavior reversed at 250 kHz: the signal loss was greater when the epoxy-based circuit functioned as an actuator (approximately threefold compared to copper) and comparatively lower about twofold when used as a receiver. These observations highlight the influence of both frequency and material conductivity on signal transmission, with silver-based printed circuits offering better performance across both tested frequencies.

(a) (b)

|

(c) (d)

3.4. AUCT-printed circuit film bonding

The developed AUCT-printed circuit film is shown in Figure 8. The printed circuits were directly connected to the AUCT’s electrical contacts, eliminating the need for traditional soldered copper cables, which are prone to mechanical failure. This direct integration has the potential to improve connection reliability, though further mechanical testing is needed to confirm this.

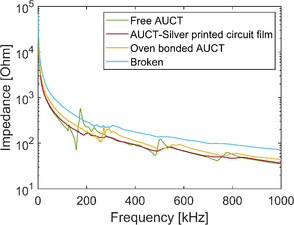

The impedance spectra of the AUCT under various bonding configurations, including a free AUCT, a broken AUCT, an oven-bonded AUCT, and the AUCT integrated within the printed circuit film is presented in Figure 9. A comparison between the impedance response of the integrated film AUCT and the broken AUCT confirms that the transducer remained operational following the bonding process. Notably, the resonant frequency of the integrated AUCT shifted toward that of the oven-bonded configuration, suggesting successful bonding. These results highlight the feasibility of fabricating and bonding flexible, printed circuit films with integrated AUCTs for scalable SHM system integration, though further optimization is needed for improved performance and stability.

4. Conclusion

The results presented in this study highlight the potential advantages of using nanoparticle-doped inks and printed circuit technologies over conventional copper wiring for SHM applications. In terms of weight, silver-GNP and epoxy-based CNT-GNP circuits demonstrated a substantial reduction in linear mass density compared to traditional copper cables.

Electrical conductivity measurements further revealed that the incorporation of carbon-based nanoparticles, particularly in hybrid CNT-GNP formulations, leads to dramatic improvements in conductivity once the percolation threshold is reached. Silver-based inks showed even greater conductivity, with GNP additions proving especially effective due to superior dispersion and inter-particle connectivity. While CNTs also improved conductivity, their limited dispersibility in silver ink hindered the formation of robust conductive networks compared to GNP-enhanced variants.

Signal transmission experiments confirmed the functional viability of printed circuits as lightweight interconnects. Silver-based inks, especially those modified with GNPs, closely matched copper cables in terms of waveform amplitude and fidelity. In some cases, silver circuits even outperformed copper in signal amplitude, particularly at the lower frequency. Meanwhile, epoxy-based circuits with CNT-GNP fillers, though capable of signal transmission, exhibited greater resistive losses and performance variability depending on their role as actuators or receivers and the excitation frequency. These findings underscore the importance of both material composition and operating conditions in determining transmission efficiency.

Overall, the results demonstrate that silver-based printed circuits, particularly those modified with GNPs, offer a promising lightweight and high-performance alternative to traditional wiring in SHM systems. Meanwhile, epoxy-based composites show potential for less demanding applications or where flexibility and integration with structural components are priorities.

5. References

[1] A. Güemes, A. Fernandez-Lopez, A. R. Pozo, and J. Sierra-Pérez, “Structural health monitoring for advanced composite structures: A review,” 2020, MDPI AG. doi: 10.3390/jcs4010013.

[2] X. Qing, W. Li, Y. Wang, and H. Sun, “Piezoelectric transducer-based structural health monitoring for aircraft applications,” Feb. 01, 2019, MDPI AG. doi: 10.3390/s19030545.

[3] F. Lambinet and Z. Sharif Khodaei, “Development of hybrid piezoelectric-fibre optic composite patch repair solutions,” Sensors, vol. 21, Aug. 2021, doi: 10.3390/s21155131.

[4] D. G. Bekas, Z. Sharif-Khodaei, and M. H. Ferri Aliabadi, “An innovative diagnostic film for structural health monitoring of metallic and composite structures,” Sensors (Switzerland), vol. 18, no. 7, Jul. 2018, doi: 10.3390/s18072084.

[5] A. Cortés, A. Jiménez-Suárez, M. Campo, A. Ureña, and S. G. Prolongo, “3D printed epoxy-CNTs/GNPs conductive inks with application in anti-icing and de-icing systems,” Eur Polym J, vol. 141, Dec. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2020.110090.

[6] Peter Wierach, “Electromechanical Functional Module and Associated Process,” US7274132B2, 2005

[7] T. Sofi, J. A. García, M. R. Gude, and P. Wierach, “A novel and rapid method of integrating sensors for SHM to thermoplastic composites through induction heating,” Composites Part C: Open Access, vol. 17, Jul. 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.jcomc.2025.100568.

[8] T. Feng and M. H. Ferri Aliabadi, “Structural integrity assessment of composites plates with embedded PZT transducers for structural health monitoring,” Materials, vol. 14, Oct. 2021, doi: 10.3390/ma14206148.

Document information

Accepted on 25/06/25

Submitted on 13/04/25

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?