Abstract

The planning process in a planning studio demonstrates a microcosm of diverse concepts of ideologies and identities seeking acknowledgment and spatial recognition. In the modern world of multiple and dynamic identities and ideologies, aspiring for the self-recognition of regions, towns, and communities, a place-based identity has become a core aspect that needs to be taken into planning consideration. The analytic planning method used is iterative of both top–down and bottom–up approaches, thereby creating multi-dimension and coherent planning alternatives where spatial solutions arise from communities along their changing processes. We present two spatial alternative plans that were developed in the studio course and are based on this line of thinking. Results were very dynamic aspiring complex plans, which are also highly applicable and flexible, thereby addressing a wide range of ideologies and identities.

Keywords

Multi-criteria ; Planning studio ; GIS analysis ; Place-based identity ; Multi-identity

1. Need for a place-based identity-ideology planning process

Variety is an issue that needs to be considered in the modern world of multiple and dynamic identities. This recognition is an output of the place-based identity of regions, towns, communities, and individuals. Thus, it should be a core aspect of planning. This spatial diversity corresponds to the theories of multiculturalism that point out the advantage of variety (Goldberg, 1994 ; Sandercock and Lysiottis, 1998 ), individualism (Healey, 1997 ; Bellah et al., 2007 ), pluralism (Davidoff, 1965 ; Hayden, 1994 ), and cosmopolitan (Binnie et al., 2006 ; Bloomfield and Bianchini, 2003 ). However, in contrast to the theories that modern societies aim to adopt, we identify a lack of planning tools that address the main issues of multiculturalism, pluralism, and individualism on the regional level.

This article discusses the outcome of a regional planning studio that deals mainly with the development of a long-term comprehensive regional plan (50 years forward) and offers a multi-identity planning process developed by several student teams, allowing reference for different and diverse communities and identities. This process displays products that combine conceptual pluralism and the regional perspective of a bottom–up planning approach based upon the integration of spatial information technology and a multi-parametric analysis of regional planning.

1.1. Planning studio

The course methodology includes comprehensive planning that addresses complex and integrated questions of development, conservation, spatial justice, economy, transport, employment, and demographics. The planning process needs to present solutions for places situated in a dynamic process of change, where their place-based identity and self-recognition are changing and the future of their identity/identities is still unclear. This intensive course requires high investments in both methodology and technique within a limited period. The course is built upon five phases, as follows: (1) a review of the current situation (according to a spatial capital assets model); (2) individual planning concept development based on their ideological perceptions; (3) students work in teams for a comprehensive regional program development; (4) students work in teams to develop the spatial plan; and (5) an evaluation of the diverse spatial plans using analytical and political tools.

The studio methodology allows students to address different aspects of comprehensive spatial planning as part of their training as planners and as part of the formulation of a “professional voice” and planner identity. The students are required to develop a working model that answers their “professional voice” and references the characteristics and constraints of reality. The planning work is done in a given area, wherein each student׳s team provides a planning alternative. In Phase 5 of the course, all the alternatives are evaluated by the students, and the pros and cons of each alternative are discussed.

During the course, a number of student teams deal with a planning dilemma that relates to the inflexibility of the planning process of representing multi-identities or societies/communities and the difficulty of addressing differences between groups, types of identities, or communities. Criticism in planning has intensified as the real world has become more pluralistic, diverse, and multicultural.

The following are the questions we asked in a metropolitan planning studio that gave our students a chance to translate and transform their conceptual ideas into spatial policy plans. Is it possible to combine the differences between communities and types of identities that characterize the complexity and the pluralistic world we live in today in a coherent planning process that places the principle of multiculturalism as a working model premise? Can we plan for a “reasonable” person in a multicultural world or a multi-identity world? Can we combine different ideologies/identities in integrative coherent planning?

1.2. Multicultural assumptions in planning

The growth of a multicultural society is one of the known trends in the global and dynamic world and constitutes a challenge for planning. Planning has succeeded in the past by characterizing the uniform local cultural characteristics of a region or characterizing nationality with a common direction, alignment, and commitment to a common vision. Currently, such definitions are less common and agreed upon in a multicultural society, which is composed of a mosaic of communities.

This mosaic of communities has been addressed in the spatial capital assets model, which declares that a region is defined by the unique mixture of the diverse forms of capital it possesses (see e.g. Friedmann, 2002 ; Kitson et al ., 2004 ; Frenkel and Porat, 2013 ). This complex view of multi-capital assets is essential to the understanding and analysis of urban and regional complexity and the dimensions of sustainability (Friedmann, 2002 ; Nilsson, 2007 ).

Each community has its own unique mixture of capital assets, identity, and needs to fulfill its vision and goals. Communities need space and amenities to fulfill shared values, but even communities aspiring for similar goals and visions will require different needs because of spatial differences and differences in local authority policies (Walters and Brown, 2004 ). The number of processes of creating a multicultural society is increasing. On one hand, the spatial outcomes are segregations; on the other hand, a need for integration exists (Burayidi, 2000 ). However, both need a planning process that will identify their uniqueness in the first place and will address them in comprehensive planning (Hague and Jenkins, 2005 ; Devine-Wright, 2009 ). This spatial diversity corresponds with several theories, such as multiculturalism (Goldberg, 1994 ; Sandercock and Lysiottis, 1998 ), individualism (Healey, 1997 ; Bellah et al., 2007 ), pluralism (Davidoff, 1965 ; Hayden, 1994 ), and cosmopolitan (Binnie et al., 2006 ; Bloomfield and Bianchini, 2003 ) theories that point out the advantage of variety. However, in contrast to these theories, which modern societies aim to adopt, we identify a lack of planning tools addressing multiculturalism, pluralism, and individualism at the regional level that can be adopted in the planning process.

Another tool that may assess the advantage of variety is the public participatory, which is a bottom–up practice that allows connecting to multiculturalism and the needs of the stakeholders. Public participation (P2) involves diverse communities and stakeholders (usually from the same location) to understand the needs and preferences of different kinds of end-users and innovation better and to influence the planning process of a region (Rowe and Frewer, 2000 ). In a studio process, we identify a lack of geographic information system (GIS) planning tools addressing the connection between different communities aspiring for multiculturalism and end-users’ need for the regional level. PGIS, an emergent practice from participatory approaches to planning, can be adopted in this planning process; it combines a range of geo-spatial information management tools and methods to represent peoples’ spatial knowledge in the form of physical maps that are used as interactive tools for spatial analysis, discussion, information exchange, and decision-making (Corbett and Keller, 2005 ).

Therefore, planning is obligatory in mitigating the negative aspects and developing the positive aspects of diversity. The negative aspects refer to aspects of segregation and closings, and positive aspects refer to the opening of possibilities, variety, choice, and the possibility of self-determination and self-expression. Only a few cities, i.e., those that are recognized as world-class cities, have succeeded in providing multiculturalism and a hyper-diverse life for their populations. Most regions and cities prefer to differentiate themselves from other regions and have adopted homogeneous identities. Under this approach, the goal of the studio planning process is to provide the optimal combination of diversity on the one hand and not to impose pluralism on the other hand.

2. Multicultural planning model in a planning studio

Diversity and variety are addressed in planning mainly by refining the diversity of land use. In most planning fields, an increase in urban usage exists, such as green areas of different types, residential diversity and textures, density levels and urban fabric types, variety of public service, and mixed uses. This increases the variety of usage types as an outcome of the need to address a more complex existence and the need for a unique policy in a growing number of land parcels.

Currently, there is a shift in the way the urban planning process is developed around the world. This change occurs because of several transformations and changes. One example is technology change, such as implementing the GIS platform in planning (Talen, 2000 ). The development of new methods and tools for planning as form-based code (FBC) comes as an alternative to conventional zoning planning. At its base is the idea of a neighborhood or city as a whole, rather than its division by specific land uses (Parolek et al., 2008 ). The Buffalo Green Code was developed for a new approach to guiding development. This new approach is called “place-base planning,” which is a way to shape the city by concentrating on the look and potential of places and their forms and characters instead of focusing only on the conventional categories of land use. Using this code will map the entire city by place type. This will be followed by a comprehensive zoning ordinance that will create a new set of rules to encourage development that fits with the desired character of the place (http://www.buffalogreencode.com/what-is-place-based-planning/ ).

The studio projects react to these changes in the planning field, especially in the studio program. For example, the change in planning terminology developed as an outcome of a top–down planning approach. The diversity of urban usages increases the variety of zoning types and serves as a solution to complex and wide variety of laws and building regulations. The planning process tries to cope with the wide variety of laws and regulations by developing innovative and creative terminologies for the land use types. Zoning terminology is inherently general and relates to a wide variety of regions and plans; it is not created to address place-based planning. Zoning terminology is not an outcome of a bottom–up process in most planning processes, but given as a fact. Zoning terminology assumes that its richness of land uses can cope with the variety and complexity of reality; otherwise, the plan will reduce the variety to an existing terminology. In addition, a bottom–up place-based planning approach that addresses the existing and future varieties in a specific area requires a different model of zoning. It requires a model that will be sufficiently flexible to develop an appropriate spatial policy for different communities and ideologies. Despite the high-level of flexibility, the model should be generic and based on space-based analysis. Hence, these specifications require a new planning model.

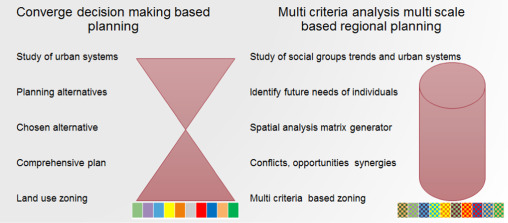

A classic planning model is built as a double funnel or a sand clock. First, information and knowledge on the region are collected. This knowledge is abstracted and simplified for representation of urban systems. This knowledge is further abstracted into planning principles, alternatives, and finally, a chosen alternative. The chosen alternative undergoes a process of expansion, deepening, and development of policy measures and spatial details that mature the process to a complete comprehensive plan (Altshuler, 1966 ; Hax and Majluf, 1996 ; Chadwick, 2013 ). The “narrow waist” of the planning process should be expanded to produce a bottom–up plan that addresses a variety of identities and different ideologies. Multiple alternatives should be reflected throughout the planning process instead of a single chosen alternative, side by side from the initial stages of data collection to the development of a comprehensive plan.

Different alternatives fit different ideologies and identities that provide a plan for the exact identity it serves. All plans have their own internal logic and an overall view that incorporates and integrates a comprehensive plan on a spatial and conceptual level. This place-based planning process creates a mosaic of programs at different levels. Thus, every level will provide a harmonious plan. The outcome plans will expose all communities and local identities and create links between communities and regions and between neighbors and similar neighbors, all at the same time. A sample of identifying future trends can be described as a combination of the following: accessibility, transportation, access to employment, housing, economic capital; education level, marital status, spatial environment, social relationship, spatial relationships; nationality, religion, gender, and language. Furthermore, different levels of the region plan will be addressed, as follows: (a) the relationship between nearby places that share community life; and (b) ideological or conceptual system between distant places. The latter is similar to the concept of an ecological corridor that connects regions to create an ecosystem. This principle will be used to connect places of common ground ideology in the formation of an ideo-system, which might be a knowledge base of similar conceptions.

This planning approach is based upon the use of GIS spatial information technology as an integral part of the planning process. This technology enables the development of multiple local plans of different characteristics and policies in one region and creates mutual connections between them. Spatial information systems can contain hundreds of attributes of information for all spatial objects and examine spatial adjustments between objects depending on their spatial and functional relationships. A similar approach can be seen at the “bottom–up GIS (BUGIS)” model developed by Talen (2000) , which included an understanding of residents׳ perceptions and preferences of local issues based on a GIS planning analysis of spatial complexity, spatial context, interactivity, and interconnection.

This place-based planning process fits ideology to an identity with an appropriate set of policies of its own and for neighboring communities. The methodology is based upon an analytic process of development of an identity matrix and a generator/influence matrix, which defy the development characteristics for different ideologies and identities as well as the mutual influences between different identities and between identities and their surroundings. The methodology may be perceived as too rigid. However, the actual reference to a wide variety of different parameters allows the extensive and complex variation of land use, which is a view to the feature that encourages plan flexibility. Parallel to the development of the influence matrix generator, an extensive set of typical identities is formed as part of the planning process. This planning model concept allows the representation of each identity׳s needs in the matrix. The set of identities represents the diversity of the population in the region and addresses future variations. The future variation of identities is set according to the current trends of global societies.

The major trends that have been introduced to the influence matrix generator represent a strengthening of self-definition based on nationality, religion, language, gender, education, economic capital, sexual orientation, marital status, and geographic identity. These processes increase the range of property needs of the society. The system may seem too rigid and categorically defines characteristics for existing and future identities. However, the opposite is true. The development of various land-use policies for an extensive set of typical identities increases the diversity across the region. This is bottom–up planning relates to the characteristics of personalities in a complex and profound way. Furthermore, this type of planning creates a wide variety of residential and employment areas, education amenities, and leisure spaces and places. This variety fits the needs of the place and also enables wide choices for future communities.

Bottom–up planning has an added value at the regional level. The classification and characterization of identities allow for identifying opportunities and conflicts, communities׳ synergistic elements, and possible collaborations. Identifying opportunities, conflicts, synergies, and potential collaborations during the planning process allows conflict mitigation and region management in a way that encourages cooperation by development. These elements play a significant role in the regional planning process, which allows and supports a variety of space-place developments and copes with the regional challenges of economies of scale, efficient transportation, employment mix, a variety of services, and optimal spatial management.

Fig. 1 describes in a schematic way the differences between a classic planning process featuring the convergence of decision-making-based planning, multi-criteria analysis of different ideologies and identities, and place-based planning process.

|

|

|

Fig. 1. A schematic presentation of classic planning process vs a place based planning process that fits different ideologies and identities. |

The following section will demonstrate the place-based planning methodology on two examples of students׳ studio course demonstration of plans. The metropolitan plans were conducted in different regions of Israel and each illustrates in its own planning process way the principles presented above.

3. Description of the planning process in the studio

3.1. Two planning areas

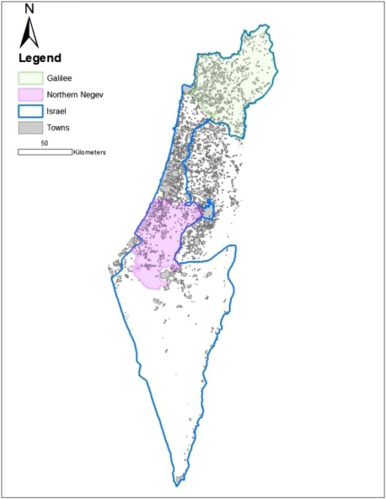

The alternative plans presented are located in heterogeneous areas at the outskirts of metropolitan core areas, one at the north of Israel, the Galilee area, and the second at the southern area of Israel, called the Northern Negev region (see Fig. 2 ). The Galilee area is a rural region that includes small towns of different Jewish and Arab cultures, with traditional employment, agriculture industries, and rural villages. The Northern Negev region is an intermediate region between the three main metropolitan areas of Israel, which are Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, and Beer-sheba, and is characterized by small- and medium-size cities, traditional employment and lifestyle, and diverse communities of Jews, Arabs, and ultra-religious Jews.

|

|

|

Fig. 2. Areal map of the two alternative plans: the Galilee alternative at the northern part of the country and the Negev alternative plan at the southern part of the country. |

The students learn and review the current situation in the planning region according to the spatial capital assets model. The data collection for this model is related to different spatial capital assets (Frenkel and Porat, 2013 ) and based (in this studio course) on open and available data sources from the Israeli Bureau of Statistics, National Insurance Institute, Ministry of Interior, Ministry of Transportation, and other open data sources and also on local survey and knowledge. According to this data analysis, the students define the spatial capital of each region and sub-regions and identified the groups, narratives, conflicts, and social trends that emerge from the analysis.

The motivation for both planning processes comes from a critical approach to the existing statutory planning that choose to ignore the variety of populations׳ narratives, identities, conflicts, and residence types in the alternative areas. The existing statutory plan defines most of the areas as rural and ignores the complexity and uniqueness of the nature of both regions. The spatial policy suffers from a lack of reference to the distinctive features that create identity and internal unity. The towns and villages in these regions are scattered and separated because of the absence of unique identity.

3.2. Definition of existing and future identities in both regions

The first stage of the planning process includes the definition of different identities and distinction between the identities in the region. The definition of identities and ideologies in the studio are based on local knowledge and common narratives of different social groups and their social trends in the public space (in the region) and on their shared characters, desires, vision, and goals. In this studio, the student involves stakeholders only as part of the planning administration and not as part of the identities.

In both alternatives, the current planning needs of various communities are examined and defined according to different routes:

3.2.1. The Galilee alternative

The plan provides a unique planning statement and individual treatment for each settlement in the space/place and for the multi-dimensional connection between them. The idea is to create alternatives for people searching for a different lifestyle and to provide a generic solution for the types of settlements that people are looking for. The place-based models provide solutions for the differences that were identified between the “needs” and “wants” of people in search of alternatives to the conventional urban lifestyle. The main emphasis is on developing models that offer conditions required for specific lifestyles that will be provided at maximum flexibility to the residents in accordance with their wants and needs. The main idea based on this notion was to categorize the existing planning process behind these settlements, which according to the old model are developed according to a specific available area with appropriate space.

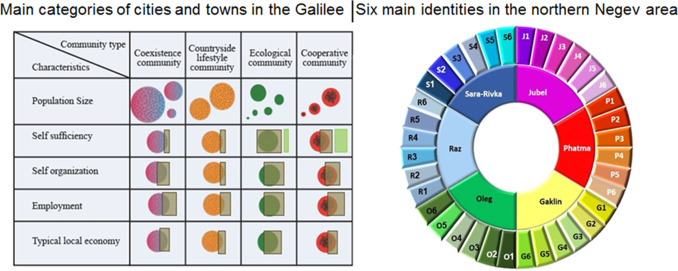

Different community types are defined by their different characteristics, such as population size, self-sufficiency, self-organization level, mix of employment types, and typical local economy. The results are based on four different types of towns, as follows:

- Ecological – According to research, ecological towns are viable only for small populations (up to 1000 residents). The distances to the city can be long because most of the residents work within the settlement. Being located close to environmentally sensitive areas suggests that these settlements have minimal environmental effect and tourism makes up a significant part of their income.

- Cooperative – Distances from the city can be long because the towns can provide work, food (from their agriculture), and services.

- Coexistence – The same as a house in a countryside, a community apparatus that is more complex and requires employment in the settlement is necessary.

- Country side, house in the countryside – The town can be larger and closer to the city and to employment centers.

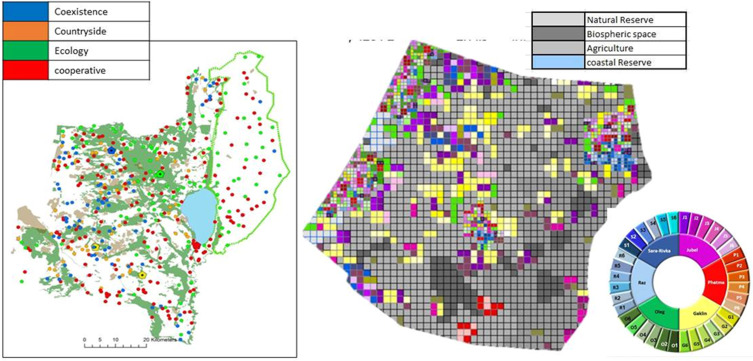

Each combination displays a different level of performance in each characteristic, as shown in Fig. 1 a.

3.2.2. The Negev alternative

In this plan, the students identify six different types of generic personal identities in the region desiring different needs and characteristics. These identities are determined through the following process. First, an analysis of the existing population characteristics is conducted. The students provides an overview of the populations living in the region and deliberately defined six stereotype figures that represent different identities living in the region, as manifested in different dimensions, such as religion, ethnicity, gender, and age. Each of the six identities has difficulties or is in conflict with the reality in the region today. These six figures are characteristics and are defined as parameters in a multi-parametric matrix. For example, Jubel (identity) is a student and a farmer׳s son deliberating between staying on the farm and leaving the farm; Phatma is a young Bedouin woman; J′aklin is a single mother living in a small traditional town; Oleg is an immigrant from the former Soviet Union who works as an engineer; Raz is a gay person who tries to find a suitable community for his modern family; and Sara-Rivka is an ultra-orthodox woman and a mother of five who works as a software programmer. Each of these generic identities provide possible future developments of these identities, as shown in Fig. 1 b. Each of the ideologies and identities also have spatial characteristics, such as transportation accessibility and access to employment, and social characteristics, such as nationality, religion, gender, language, identity, education, marital status, and economic capital.

This identity analysis characterizes the variety of present communities and their future development needs. The place-based planning process tries to cope with a range of future possibilities, such as strengthening existing traditional elements, providing a mix of traditional and modern life, or a drastic change and abandonment of social tradition and adoption of some existing trends in Israeli society and global perspectives. The analysis refers to current trends in Israeli society and global trends that will be intensified in the future, such as women׳s employment, the growth of new family types, and the blurring of gender, individualism, liberalism, and education. Each of the identities/ideologies has undergone a similar expansion process that tried to outline the future possibilities. Obviously, this process cannot predict all directions of personal development, but this kind of thinking creates a vast mosaic of various mixtures that may characterize the majority of the population (see Fig. 3 b).

|

|

|

Fig. 3. Ideologies in the Galilee and identities possible future development in the Northern Negev area. (On the left): displays the categories of cities and towns in the Galilee. Main categories of cities and towns in the Galilee are defined and its future possible relationship toward land and spatial attributes is determined. (On the right): displays six main identities in the Northern Negev area and the possible future development of these identities into 36 sub-identities. |

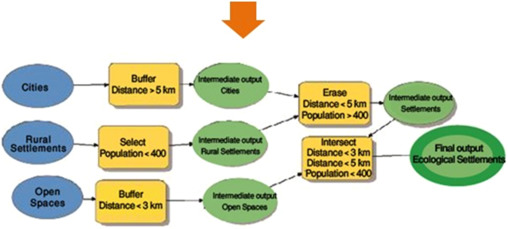

The next step in the planning process includes the characterization of the towns and villages, which will provide the needs of the different communities, such as town size and type, occupation structure, social structure, regional identity, and relationship to the natural environment. These provide the basic elements of the identity matrix generator. Each alternative plan uses a different methodology for their planning performance, as follows. (1) The Galilee alternative metropolitan plan is based on an ARCview GIS model builder that assists in creating spatial locations in a region, where each town and village can define its own spatial future and still be a part of a collective ideology (see Fig. 4 and Table 1 ). (2) The Negev alternative metropolitan plan simulates spatial locations for a mixture of future identities based on present identities and the different routes each identity may take during its growth process and possibilities of identity changes over time (see Table 2 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 4. Identity matrix generator in ARCview model builder for the Galilee alternative. |

| Distance from protected areas (km) | Distance from employment centers (km) | Distance from the city (km) | Population size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3> | – | 5< | 400> | Ecology |

| X | – | 5< | 1000> | Cooperative |

| – | 7> | 5> | 500–200 | Coexistence |

| – | 5> | 5> | 2000> | House in the countryside |

| Identity | Approximate town size | Community type | Residential type | Profession | Environment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | Medium | Traditional | Small app | Services | Suburb |

| G2 | Very large | Close | Small app | Industry | Suburb |

| G3 | Large | Open | Medium app | Academy | City |

| G4 | Medium | Medium | House | Tourism | Town |

| G5 | Small | Traditional | Medium app | Free profession | Village |

| G6 | Very large | Individual | Medium app | Free profession | Metro |

| P1 | Small | Close | Medium app | Free profession | Village |

| P2 | Small | Traditional | House | Agriculture | Farm |

| P3 | Large | Open | Large app | Academy | City |

| P4 | Large or very large | Multi | Medium app | Tourism | City |

| P5 | Very large | Open | Medium app | Hi-tec | Metro |

| P6 | Very large | Individual | Small app | Clean-tec | City |

| S1 | Very large | Close | Large app | Hi-tec | City |

| S2 | Metro | Individual | Small app | Services | Metro |

| S3 | Very large | Open | Medium app | Free profession | City |

| S4 | Large | Multi | Medium app | Academy | Town |

| S5 | Very large | Traditional | Large app | Industry | City |

| S6 | Large | Individual | Small app | Academy | Town |

| J1 | Very small | Individual | House | Tourism | Village |

| J2 | Very small | Open | Farm | Agriculture | Village |

| J3 | Large | Close | Small app | Hi-tec | City |

| J4 | Medium | Multi | Medium app | Academy | Town |

| J5 | Medium | Individual | Split Level | Free profession | Town |

| J6 | Very small or very large | Multi | Medium app | Services | Suburb |

| R1 | Small | Individual | Split Level | Agriculture | Farm |

| R2 | Very large | Multi | Medium app | Free profession | City |

| R3 | Very large | Open | Large app | Services | Metro |

| R4 | Small | Open | Split Level | Tourism | Village |

| R5 | Very small | Close | Split Level | Free profession | Village |

| R6 | Large | Individual | Medium app | Academy | Town |

| O1 | Very large | Individual | Large app | Hi-tec | City |

| O2 | Metro | Multi | Small app | Academy | Metro |

| O3 | Very large | Open | Large app | Services | City |

| O4 | Very small | Individual | Split Level | Free profession | Village |

| O5 | Very large | Traditional | Small app | Industry | City |

| O6 | Metro | Close | Medium app | Clean-tec | Metro |

3.3. Development of identity matrix generator

The next stage of the methodology is based on a generator of ideologies and their transportation accessibility, access to employment, and social characteristics, such as nationality, religion, gender, language, identity, education, marital status, and economic capital. All of these are translated to define the spatial environment for each community and type of housing, employment, social relationship, and spatial relationships between different ideologies. These matrices are known as the “identity matrix generator .” The matrix contains ideology types that were identified in the first stage and future ideologies that were developed based on social trends. The Galilee alternative developed the generator according to geographical characteristics (see Fig. 4 and Table 1 ), and the Northern Negev alternative developed the generator according to social indicators (see Table 2 ).

Diverse ideologies are identified to cater to the characteristics of each existing and future identity and the towns and villages that will provide an opportune environment for communities. This matching process is accompanied by a development of policy measures for required adjustments that include, e.g., the establishment of specialized employment centers, educational institutions, and entertainment directed toward the needs of the communities. The policy measures also include a basis for future establishment of new settlements designated if required.

The implementation of this methodology for large regional areas includes hundreds of different kinds of settlements that will allow specific reference to versatile ideologies and different communities that were the result of individual plans (see Fig. 4 ). The spatial distribution of towns and villages allowed a versatile identities mix for different communities, complex spatial pattern, and differentiated spatial policy for different types of ideologies.

The implementation of the spatial identity matrix generator methodology over a large area includes hundreds of different kinds of identity combinations that allow specific reference for versatile ideologies, where different communities receive individual plans, thereby providing spatial patterns of ideologies in the Galilee and the Northern Negev alternatives. This specific methodology treatment for hundreds of options is possible because of GIS technologies.

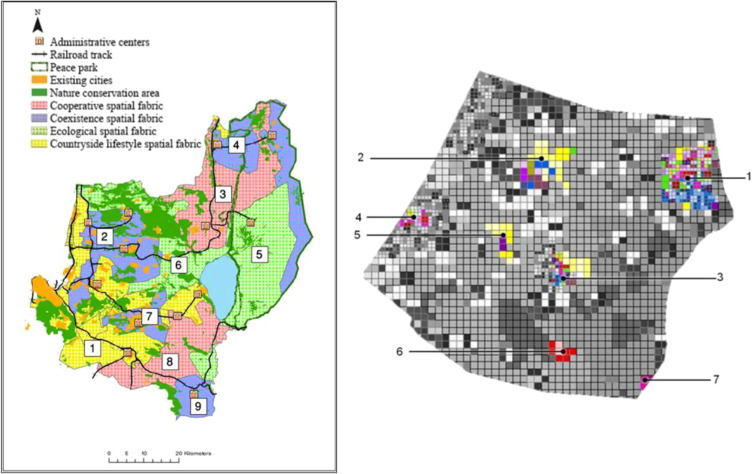

The pattern of ideologies, as shown in Fig. 5 , support a complex of sub-regional divisions, providing opportunities for regional collaboration and cooperation, conflict recession, identifying opportunities, and synergies between localities and communities.

|

|

|

Fig. 5. Spatial patterns of ideologies: on the left side are the ideologies settlements in the Galilee alternatives; on the right side the ideologies in the Northern Negev alternatives. |

The Galilee alternative addresses the northern part of Israel and defines the core areas that will assist in connecting towns and villages of similar characteristics and empower them in areas, such as economics of scale, transportation efficiency, and employment mix. In addition, core areas of specific aspects that will support the ideologies based pattern are developed, as follows: (1) establishing a core area for community towns in Carmiel; (2) strengthening four core areas of mixed community towns in Maalot, Tarshiha, Massada, and Bet Shean; (3) developing core areas for agriculture-based villages in Kryat-Shmona, Shfaram, and Kafar Kama; and (4) developing core areas for ecological villages in Kazrin and Tiberious.

The Negev alternative addresses the southern part of Israel and emphasizes opportunities and conflicts in that area, as follows: (1) religious/secular conflict in the town of Bet-Shemes; (2) social decline in the very homogeneous city of Kiryat-Malahi; (3) social opportunity in a heterogeneous city, Kiryat-Gat, adjacent to an agricultural landscape; (4) opportunity for heterogeneous city on the seashore of Ashkelon; (5) social conflict between old conceptions and new ones in the village of Nehora; (6) opportunity for spatial interaction in new Bedouin villages; and (7) opportunity for ecological communities.

Both alternative plans (see Fig. 6 ) represent a vast variety of towns and village types, having complex spatial plans that were created in an analytic process and offer a spatial pattern that supports a variety of ideologies. Mapping the spatial distribution of different types of towns and villages allows planners to connect and link communities of similar characteristics or complementing characteristics. Both pattern alternatives support a complex of sub-regional divisions, which provide opportunities for regional collaboration and cooperation, conflict recession, identifying opportunities, and synergies between localities and communities. The product of this analysis allows for the examination of the spatial role of different communities in future situations (see Fig. 6 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 6. Subdivision of spatial fabrics in the Galilee alternative (on the left side) and opportunities and conflicts in the Negev alternative (on the right side). |

4. Discussion and conclusion

The planning process that was developed in the metropolitan planning studio shows that both plans relate to the tension between planning at the individual level (community and ideology) and are involved in comprehensive planning. Both alternative plans indicate that vital and extensive information related to ideologies and a regional way of life may be lost in classic comprehensive planning approach, including information that deals with the needs and desires of individuals. In addition, both alternative plans began by assuming that this personal information needs to be at the core of the planning process, and a future approach to decision-making and planning models should keep this information throughout the planning process until the formulation of the plan (Ho et al., 2010 ).

In both alternative plans, the planning policy relates differently to various ideologies and regional policies that point out different characteristics of the land uses in every location in the region, considering the characteristics of existing and future types of ideologies. The plans tell personal stories of various ideologies found in the region, trying to deal with the different paths each identity will take in the future by drawing alternative paths of diverse personal development of various identities according to global and local trends.

Future relationships between identities and communities in the region are defined by the influence of the matrix generator. This matrix generator defines the relationship between characteristics and different ideologies and types of towns/villages in the regions. This generator is a geo-social matrix that addresses the spatial needs of various ideologies, such as settlement sizes, proximity to employment, proximity to services, and closeness to nature.

This planning methodology enables the multi-resolution observation of the process. The methodology allows a user to zoom in on different types of communities and examine the conditions for their flourish, identify conflicts, regional opportunities, and ways to resolve/mitigate controversies between communities. The methodology allows for zooming out on overall connections and relations between communities and addressing mutual influences. This multi-resolution observation provides multi-level solutions of spatial conflicts and identifies spatial opportunities.

Such a detailed approach of the characters of each identity can be operated and managed by users through GIS and the ability to manage and control hundreds, thousands, or even more features in an attribute matrix table. The attribute matrix table allows a multi-parametric approach to the different identities with no need to reduce parameters. In the case presented here, different identities were characterized by 17 different characteristics concerning a variety of spaces, such as personal, cultural, social, and spatial. These data have not been analyzed in a process that lowers the number of variables, such as cluster or factor analysis. On the contrary, processing the data increased the variance and the analysis enhanced and enriched the data. We would like to point out that the rapid technological development in the last decade has enabled planners to develop this form of planning process for special development and contributed to the studio working plan.

The analysis of the spatial distribution of identities identified spatial conflicts and opportunities, addressing and presenting a complete picture of the region and the policies derived for different identities. This multi-parametric analysis produces two alternative plans with very different spatial structures but very similar ways of addressing different identities.

Both alternative plans represent a vast variety of towns and village types, having complex spatial patterns that support a variety of ideologies. Mapping the spatial distribution of different types of towns and villages allows planners to connect and link communities of similar characteristics or complementing characteristics.

However, this approach has several limitations. First, the process requires very good data of the planning region, social assets, and social trends, and such data are not always available. Second, a high degree of predictability of the future plans exists and forecasting of complex social trends is still too complex to be done. In addition, open and available data relating to capital resources estimation and characterization of identities, which are important to the planning process, are limited. Relationship to planning requires an open and flexible planning system.

Therefore, this identification offers a regional planning dimension of connectors, bridges, and links based on relationships, opportunities, conflicts, and complementarity of diverse issues, thereby allowing for the tailoring of specific planning solutions as appropriate. This regional dimension is based on the complex layout of towns and villages, and it deals with questions of economies of scale and efficiency on the one hand and spatial diversity benefits management, conflict management, and spatial opportunities arising from the diversity on the other hand.

References

- Altshuler, 1966 Alan A. Altshuler; The City Planning Process: A Political Analysis; Cornell University Press, United States of America (1966)

- Bellah et al., 2007 Robert N. Bellah, Richard Madsen, William M. Sullivan, Ann Swidler, Steven M. Tipton; Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life, University of California Press, United States (2007)

- Binnie et al., 2006 Binnie, Jon, Holloway, Julian, Millington, Steve, Young, Craig, 2006. Cosmopolitan Urbanism. (Eds.), Routledge, United Kingdom

- Bloomfield and Bianchini., 2003 Bloomfield, J., Bianchini, F., 2003. Planning for the cosmopolitan city. In: Proceedings of COMEDIA and International Cultural planning and Policy Unit (ICPPU). De Montfort University, Leicester.

- Burayidi, 2000 Michael A. Burayidi; Urban Planning in a Multicultural Society; Greenwood Publishing Group, United States (2000)

- Chadwick, 2013 George Chadwick; A Systems view of Planning: Towards A Theory of the Urban and Regional Planning Process; Elsevier, The Netherlands (2013)

- Corbett and Keller, 2005 J.M. Corbett, C.P. Keller; An analytical framework to examine empowerment associated with participatory geographic information systems (PGIS); Cartogr.: Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Geovisualization, 40 (4) (2005), pp. 91–102

- Davidoff, 1965 Paul Davidoff; Advocacy and pluralism in planning; J. Am. Inst. Plan., 31 (4) (1965), pp. 331–338

- Devine-Wright, 2009 Patrick Devine-Wright; Rethinking NIMBYism: The role of place attachment and place identity in explaining place-protective action; J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol., 19 (6) (2009), pp. 426–441

- Frenkel and Porat, 2013 Frenkel, A., Porat, I., 2013. An integrative spatial capital based model for strategic local planning. In: Proceedings of the Regional Studies association, Winter Conference on: Mobilizing Regions: Territorial Strategies for Growth. London, UK, November 22nd, 2013.

- Friedmann, 2002 John Friedmann; The Prospect of Cities, University of Minnesota Press, United States (2002)

- Goldberg, 1994 David Goldberg; Multiculturalism: A Critical Reader (1994)

- Hayden, 1994 Dolores Hayden; Who plans the USA? A comment on “advocacy and pluralism in planning”; J. Am. Plan. Assoc., 60 (2) (1994), pp. 160–161

- Hague and Jenkins, 2005 Cliff Hague, Paul Jenkins; Place Identity, Participation and Planning, 7, Psychology Press, United Kingdom (2005)

- Hax and Majluf, 1996 Arnoldo C. Hax, Nicolas S. Majluf; Strategy Concept Process: A Pragmatic Approach (1996), pp. 360–375

- Healey, 1997 Patsy Healey; Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies; Ubc Press, Canada (1997)

- Ho et al., 2010 William Ho, Xu Xiaowei, Prasanta K. Dey; Multi-criteria decision making approaches for supplier evaluation and selection: a literature review; Eur. J. Oper. Res., 202 (1) (2010), pp. 16–24

- Kitson et al., 2004 Michael Kitson, Ron Martin, Peter Tyler; Regional competitiveness: an elusive yet key concept?; Reg. Stud., 38 (9) (2004), pp. 991–999

- Nilsson, 2007 Kristina L. Nilsson; Managing complex spatial planning processes; Plan. Theory Pract., 8 (4) (2007), pp. 431–447

- Parolek et al., 2008 Daniel G. Parolek, Karen Parolek, Paul C. Crawford; Form Based Codes: A Guide for Planners, Urban Designers, Municipalities, and Developers; John Wiley & Sons (2008)

- Rowe and Lynn, 2000 Gene Rowe, J. Frewer Lynn; Public participation methods: aframework for evaluation; Sci. Technol. Hum. Values, 25 (1) (2000), pp. 3–29

- Sandercock and Lysiottis, 1998 Leonie Sandercock, Peter Lysiottis; Towards Cosmopolis: Planning for Multicultural Cities (1998)

- Talen, 2000 Emily Talen; Bottom–up GIS: a new tool for individual and group expression in participatory planning; J. Am. Plan. Assoc., 66 (3) (2000), pp. 279–294

- Walters and Brown., 2004 David Walters, Linda Luise Brown; Design First: Design-Based Planning for Communities, Routledge, (2004) (http://urbed.coop/projects/nottingham-city-centre-design-guide http://www.buffalogreencode.com/what-is-place-based-planning/)

Document information

Published on 12/05/17

Submitted on 12/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?