Abstract

The Mughal settlements are an integral part of Old Dhaka. Uncontrolled urbanization, changes in land use patterns, the growing density of new settlements, and modern transportation have brought about rapid transformation to the historic fabric of the Mughal settlements. As a result, Mughal structures are gradually turning into isolated elements in the transforming fabric. This study aims to promote the historic quality of the old city through clear and sustainable integration of the Mughal settlements in the existing fabric. This study attempts to analyze the Mughal settlements in old Dhaka and correspondingly outline strategic approaches to protect Mughal artifacts from decay and ensure proper access and visual exposure in the present urban tissue.

Keywords

Mughal settlement ; Urban transformation ; Integration

1. Introduction

Dhaka was established as a provincial capital of Bengal during the Mughal period. The focal part of Mughal City is currently located in old Dhaka, which has undergone successive transformations. The Mughal settlements are considered the historic core of Mughal City. The old city covers an area of 284.3 acres with a population of 8,87,000. The area is home to 15% of the total population of urban Dhaka while occupying only 7% of its gross built-up area (DMDP, 1995–2015, Vol ll). Most parts of the place are undergoing gradual physical deterioration. The scarcity of open spaces, coupled with the high plot coverage, limits the scope of recreational and cultural activities. The social characteristics of the old district have also undergone changes. Historic buildings have been subdivided for multiple families, densities have risen to inordinate levels, and new settlements are growing rapidly without due consideration of the historic settlements. This study examines the Mughal settlements and their successive transformations in the old fabric to suggest corresponding comprehensive guidelines for integration.

2. Methodology

The study is conducted as a “desk-top research”, which includes a review of related literature and field survey. Historical research1 method is adopted partly to establish the chronology and legacy of physical growth patterns. Then, qualitative research2 method is used to address the research problems. This study will use two approaches:

- The theoretical part will be based on literature review.

- The field research will be based on an empirical survey that will involve the collection and analyses of two types of data:

Quantitative data: Involve architectural survey and analysis of numerical data, such as data on land use, infrastructure, and on-site investigation at a small scale.

Qualitative data: Involve analysis of data obtained through interviews and historical assessment.

Documentary research and on-site investigations will be important in identifying historic interventions and urban elements. This research will be a continuation of the authors previous study on the same heritage site.

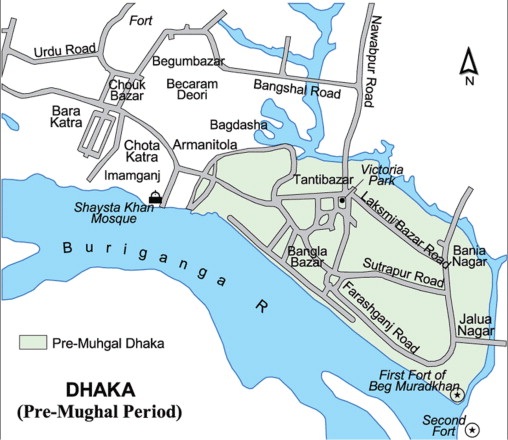

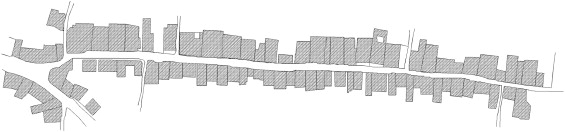

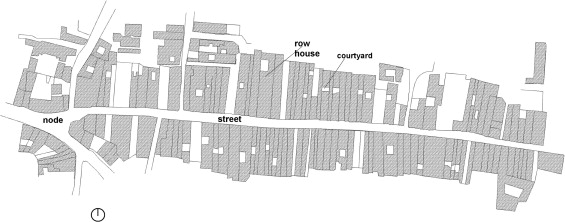

3. Pre-Mughal settlements (before 1608)

Before the Mughal period, Dhaka was successively ruled by Sena, Turkish, and Afghans (Taifoor, 1956 ). Dhaka was a trading center for the pre-Mughal capital located at Sonargaon and consisted of a few market centers, along with few localities comprising craftsmen and businessmen. All of these localities were confined within the circuit of the old Dholai Khal. The tantis (weaver) and the sankharis (shell cutter) are believed to be the oldest inhabitants of the city, and they still live in the area ( Dani, 1962 ). In most of the localities, the houses of local craftsmen had small factories. The row houses of Shankhari Bazaar had a narrow frontage of 6–10 feet, depth of 30–40 feet, and a height up to 4 stories (Taifoor, 1956 ). Tanti Bazaar also had similar types of settlements. The linear organization of houses at both sides along narrow lanes resulted in very compact settlement patterns (See Figure 1 ; Figure 2 and Table 1 ).

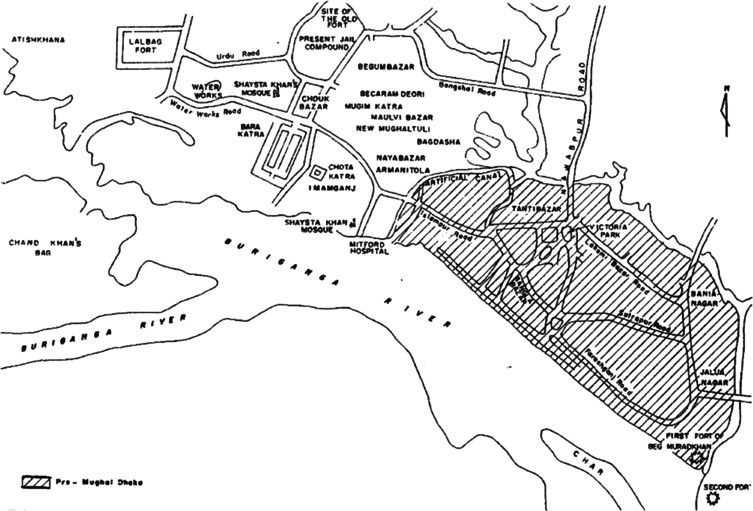

4. Mughal settlements (1608–1764)

During the Mughal period, Dhaka became an important metropolis and capital of Bengal because of its administrative, commercial, and infrastructural importance. It started to extend westward up to Sarai Begampur and northward to Badshahi Bagh (Dani, 1962) . Under Shaista Khan (1662–1679), the city extended to 12 miles in length and 8 miles in breadth and served as a home to nearly 1,000,000 people ( Taifoor, 1956 ).

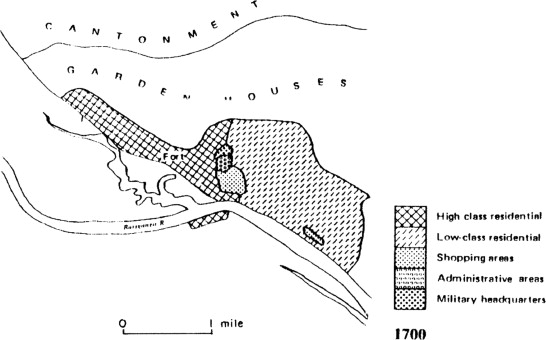

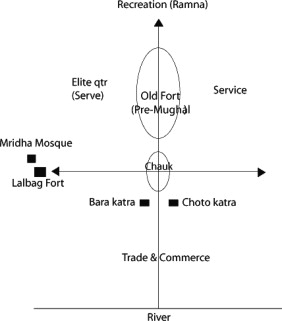

Local roads were filled with pedestrians, and river and canals were the important traffic conduit of the city. Therefore, landing platforms at the river bank, locally known as ghats , were the significant feature of Mughal City. Several bridges in Mughal Dhaka are completely lost now. The city was divided into a number of neighborhoods, which were a cluster of houses webbed with intricate narrow lanes ( Islam, 1996a ). These narrow lanes were paved with bricks in 1677–1679 (Dani, 1962 ). Two principal roads can be found: one that ran parallel to the river from Victoria Park to the western fringe of the city, and another that extended from Victoria Park to Tejgaon.3 The intersections of narrow lanes formed wide and irregular nodes that acted as a civic space at the local level. The sense of enclosure of these spaces was very intimate in scale. Some of the local nodes turned into chowks (squares) of mohallahs (neighborhood), whereas other nodes were rather intimate in nature and held local social gatherings ( Nilufar, 2011 ). Dhaka lacked any kind of corporate or municipal institutions during the Mughal period (Gupta, 1989 ) (See Figure 3 , Figure 4 , Figure 5 , Figure 6 , Figure 7 , Figure 8 ; Figure 9 and Table 2 ). A magnificent view of the Mughal buildings was observed from the river because the river front was the most dominant part of Mughal City that can be approached through the river route. The functional zoning of Mughal Dhaka was as follows.

4.1. The residential zone

The areas to the south and southwest of the Old Fort up to the river bank grew mainly as commercial areas, whereas the areas to the north and northeast grew as residential areas (Chowdhury and Faruqui, 1991 ). The neighboring localities of Lalbagh Fort, namely, Rahmatganj, Kanserhata, Urdu Bazaar, Bakshi Bazaar, Atishkhana, Shaikh Sahebs Bazaar, Chaudhury Bazaar, Qasimnagar, Bagh Hossainuddin, Nawabganj, and Enayatganj, including Qazirbagh and Hazari Bagh, were the Mughal colonies of officers. The entire area of Bakshi Bazaar and Dewan Bazaar served as the residence of provincial ministers, dewans , and secretaries. Large palatial buildings were found at Becharam Dewri, Aga Sadeq Dewri, Ali Naqi Dewri, and Amanat Khan Dewri. The Mughal elites, including princes, had palaces along the riverfront ( Dani, 1962 ).

4.2. Service zone

The cottage industries and trading areas of the pre-Mughal period and some other localities were used to house the major part of the citys low-class population that consisted of artisans, laborers, and traders. Pre-Mughal localities, which were confined within the circuit of the old Dholai Khal Canal, were turned into the service zone of Mughal City. These localities were almost segregated from the high-class residential areas.

4.3. Central business district

During the Mughal period, Chauk Bazaar was developed as the main business center near Bara-Katra. The market was well located to serve both upper- and lower-class residential areas. Chauk Bazaar was connected to Sadarghat (a landing platform at the bank of Buriganga River) by a road running parallel to the river. Another commercial center was located at Bangla Bazaar, which was the main shopping center before the Mughal period (Taifoor, 1956 ) (See Table 3 ).

4.4. Recreational zone

The Mughal elites had garden houses for recreation, festivities, and receptions. In the present Ramna area, a number of two- or three-storied mansions with spacious reception halls can be found. Gardens can also be found at Hazaribagh, Qazirbagh, Lalbagh, Bagh Chand Khan, Bagh Hosainuddin, Bagh Musa Khan, Arambagh, Rajarbagh, Malibagh, and Bagh-i-Badshahi (Dani, 1962 ).

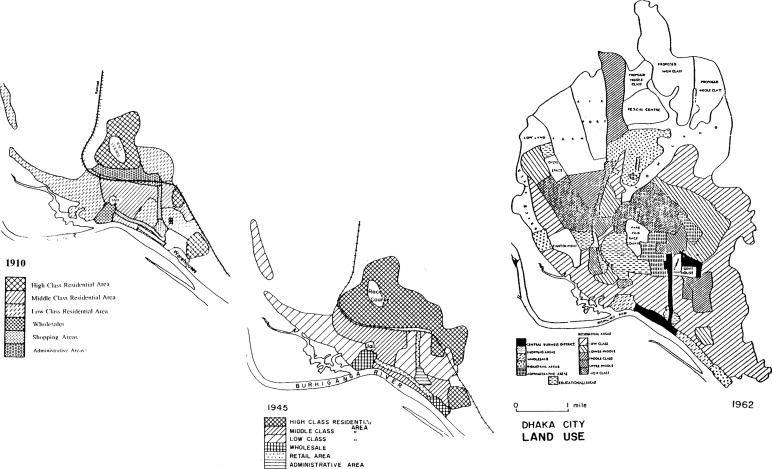

5. Post-Mughal transformation

During the British period (1765–1947), the old Mughal town did not expand, but it underwent some forms of renewal. The medieval Dhaka transformed into a modern city with metal roads, open spaces, street lights, and piped water supply (Ahmed, 1986 ). Some roads within the old city were widened, and new buildings were erected near Victoria Park for administrative and educational purposes (Dani, 1962 ). The Old Fort was turned into a jail. However, most of the residential quarters were within the historic core; the river front and the area near Victoria Park was a prized location for high-class residents (Islam, 1996). After the partition of British-India in 1947, Dhaka served as the capital of then East Pakistan. After the liberation in 1971, Dhaka became the capital of Bangladesh. Dhaka continued to expand farther to the north. The old city has gradually become congested because of unplanned growth. Since 1947, most parts of the area have been losing residential quality and transforming rapidly into wholesale and retail areas. Historic buildings have been subdivided for multiple uses, and densities have risen to inordinate levels because of encroachment and growth of informal settlements around. Cannals, such as Dholai Khal and Begunbari Khal, that worked as important traffic conduit are filled up to create land for new settlements (See Fig. 10 ).

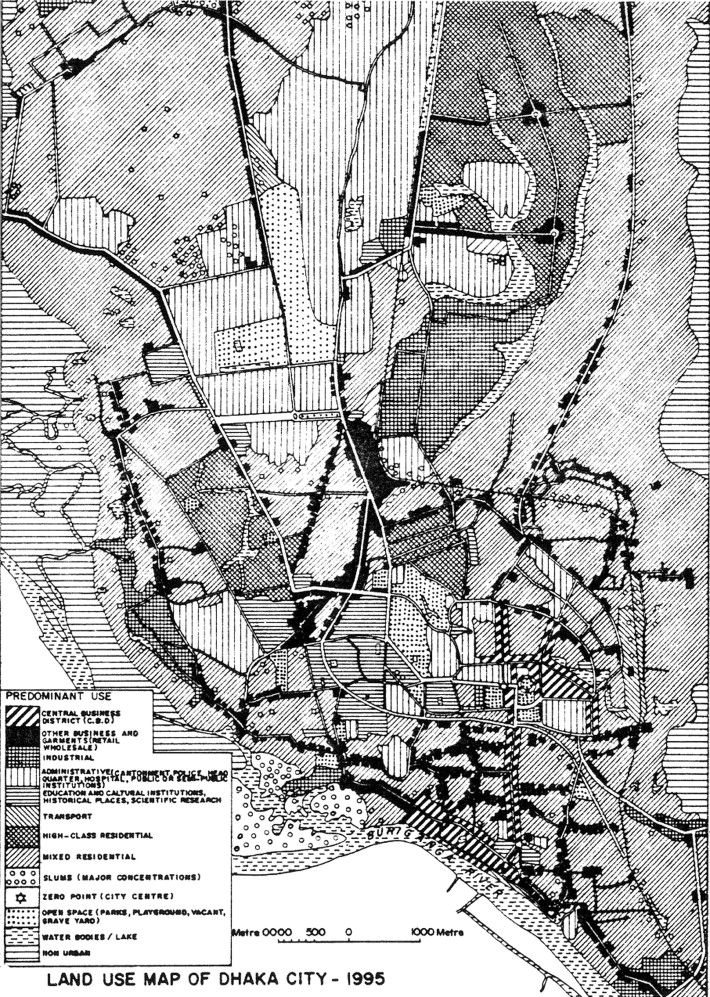

6. Existing fabric

The old city is currently considered the historic core and commercial nerve of Dhaka. The existing city web is very difficult to maintain because organic growth has remained apparently unaffected by coerced geometry, and many design qualities are inherent in such a townscape. Because of changes in its course, the riverbank has now moved away from the Mughal settlements, and the newly built settlements around the artifacts create obstacles to the visibility of historic structures from the river and different parts of the old city (See Fig. 11 and Table 4 ).

6.1. Urban pattern and spatial divisions

Socio-cultural dynamics in the area resulted in the formation of a spontaneous neighborhood, known as para mahalla , which acts as the basic spatial unit of the organic pattern in the urban web. The basic pattern evolved a hierarchy of spaces: courtyards, narrow lanes, nodes, and bazaars that manifested the socio-cultural quality of urban life ( Mowla, 1997a ). The formation of major streets is significantly related to the course of the river. Documentation of the informal units of the urban web is necessary and should cover primary measurements, including height, nature of internal divisions, and use. A comprehensive strategy may be required to determine the different levels of interventions for different spatial divisions on the basis of their townscape value. Ghats (landing platforms) at river banks establish a significant linkage between streets and rivers. Typical lanes and the lanes of old Dhaka, in particular, are extremely narrow, with curves that often create difficulties for modern transport but offer changing views during pedestrian movement. The streets are typically accompanied by urban services. The Buckland embankment that once used to offer recreational facilities for quality urban life has undergone changes because of the growth of informal settlements (See Figs. 12 and 13 ).

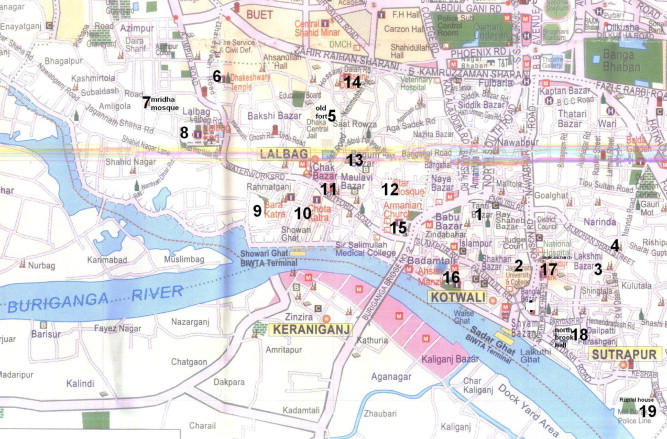

6.2. Historic buildings and sites

The Mughal buildings stand in great contrast to post-Mughal structures. The Mughal buildings have almost become isolated elements in the present fabric. Very few of the artifacts are preserved: most of them exist in deplorable conditions and are gradually deteriorating because of lack of maintenance. Architectural conservation of these historic artifacts is obviously needed. The historic structures are hidden within newly developed dense settlements that create a visual obstacle and poor access to the artifacts (See Figure 14 , Figure 15 , Figure 16 , Figure 17 , Figure 18 ; Figure 19 and Table 5 ).

7. Strategies for integration

The dynamics of rapid urbanization, shifting economic activities, changes in land use pattern, growing density in new settlements, and modern transportation have transformed the city structure. These dynamics need to be managed through the integration of historic urban elements within the existing fabric. Shifting the focus from individual buildings to the urban context during integration may reinforce the incorporation of the new structures by the urban pattern into the old fabric. Therefore, the integration of the Mughal settlements may be considered as a planning concept and tool to justify the urban form in incorporating the new and the old to maintain urban continuity and identity. Furthermore, establishing guidelines on the nature of interventions is important to meet the standards of historic value and adopt those that respond to the economic and social realities within which the buildings will to be used. The strategies to integrate the Mughal settlements in old Dhaka may be as follows.

7.1. Special planning zone

The entire old city may be considered as a special planning zone to protect the scale, visual exposure, skyline, and different qualities of the Mughal fabric. The Dhaka Metropolitan Building Construction, Development, Protection, and Removal Rule of 2008 introduced construction restrictions within a 250-meter radius of the encircling area around historic structures. This rule still needs to give specific guidelines for color, texture, material, façade design, height, function, orientation, and other design specifications for any new structures in the existing fabric, so that identical new structures may ensure the authenticity and integrity of the urban structures. Moreover, an effective buffer zone should be introduced to protect the Mughal structures from traffic vibration, noise pollution, air pollution, water pollution, and other threats.

7.2. Traffic control

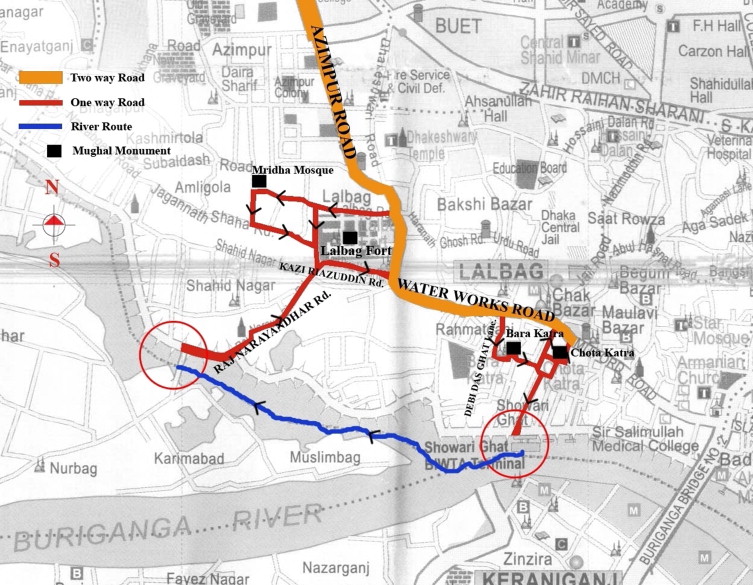

Narrow and curve streets, irregular crossings, and the shortage of parking spaces in the Mughal fabric are not suitable for the modern mechanical traffic system because the old urban setting was tailored for pedestrian movement. Traffic vibration is a major constraint that needs to be considered to manage the damage and decay of the old fabric. Moreover, the unrestricted access of slow and fast-moving vehicles results in protracted congestion. Introducing strong control over mechanical traffic at the area is needed. Parking may be considered on the perimeter outside the ring road with loops into the center. The center may be restricted to pedestrian movements, light vehicles, and a limited number of heavy vehicles. The transportation route should be developed to establish a link between the periphery and the new city and thus reduce traffic load because of commercial activity. Shifting the focus on water transportation may also reduce traffic load on existing roads. Small routes for heritage walk may be developed within the present fabric to promote cultural tourism. The traffic route4 in Fig. 20 proposes a heritage walk with a focus on the Mughal settlements along the river bank.

| Type | Settlement |

|---|---|

| Market centers | Sankhari Bazaar (shell cutters locality), Tanti Bazaar (weavers market), Laksmi Bazaar, Bangla Bazaar |

| Localities of craftsmen and businessmen | Kumartoli (potters' locality), Patuatuli (jute-silk painters' area), Sutrapur (carpenters' area), Bania Nagar (traders' area), Jalua Nagar (fishermens area), Bania Nagar, and Goal Nagar |

| Fort | Old Afghan fort |

| Religious areas | Dhakeshwari Temple, Jaykali Temple, Lukshminarayan Temple, Binat Bibi Mosque |

| Type | Monument |

|---|---|

| Mosques and other religious buildings | Khan Mohammad Mridha Mosque, Kartalab Khans Mosque, Star Mosque, Armanitola Mosque, Nawab Shaista Khans Mosque, Chauk Bazaar Mosque, Farrukhsiyar Mosque, Hussaini Dalan, etc. |

| Tombs | Tomb of Bibi Pari, Bibi Champa, etc. |

| Caravan sari | Bara Katra and Choto Katra |

| Fortresses | Incomplete Fortress at Lalbagh |

| Bridges | Tanti Bazaar Bridge, Masandi Bridge, Narinda Bridge, Amir Khans Bridge, Srichak Bridge, Babu Bazaar Bridge, Rai Shahebs Bazaar Bridge, Nazir Bazaar Bridge, Chand Khans Bridge |

| Type | Building |

|---|---|

| Trade center | Chauk and Bangla Bazaar |

| Caravan sari | Bara Katra and Chota Katra |

| Administrative headquarters and residence of the prince and other imperial officers and soldiers | Old Afgan Fort reconstructed during the Mughal period |

| Actor | Role |

|---|---|

| Department of Archeology | Under the “Antiquities Act,” Bangladesh has both the explicit and implicit mandate of heritage resource protection and conservation. |

| RAJUK (Capital Development Authority) | Introduce rules to control new developments within and around historic sites under the Building Construction Act |

| Department of Tourism | Promote tourism |

| Dhaka City Corporation | Provide municipal services |

| Mughal Structure | Legal status | Accessibility and visibility | Physical condition | Present use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tanti Bazaar | RAJUK listeda | Poor | Extremely dilapidated condition with alterations and extensions | Shop house |

| Shakhari Bazaar | RAJUK listed | Poor | Extremely dilapidated condition with alterations and extensions | Shop house |

| Binat Bibi Mosque | RAJUK listed | Poor | Extremely dilapidated condition with alterations and extensions | Originally used as a mosque |

| Dhakeshwari Temple | RAJUK listed | Good | Requires proper maintenance | Original use |

| Old Fort | Not listed as a heritage building | Accessible but not visible from a distance because of the newly built surrounding structures | Existing with several alterations to the original structure | Central Jail |

| Khan Mohammad Mridhas Mosque | DOAb and RAJUK listed | Accessible but not visible from a distance because of the newly built surrounding structures | Preserved and maintained by the Department of Archeology | Originally used as a mosque |

| Lalbaghfort | DOA and RAJUK listed | Accessible but not visible from a distance because of newly built surrounding structures | Preserved and maintained by the Department of Archeology. Some portions are still encroached. | Museum |

| Bara Katra | DOA and RAJUK listed | Extremely poor | Extremely dilapidated condition, with inner court and surroundings extensively encroached. | Subdivided and used as a warehouse, school, residence, shop, etc. |

| Chota Katra | DOA and RAJUK listed | Extremely poor | Extremely dilapidated condition, with inner court and surroundings extensively encroached. | Subdivided and used as a warehouse, school, residence, shop, etc. |

| Star Mosque | RAJUK listed | Accessible but not visible from a distance because of newly built surrounding structures | Existing with several alterations to the original structure. Requires proper preservation and maintenance. | Originally used as a mosque |

| Kartalab Khans Mosque | RAJUK listed | Accessible but not visible from a distance because of newly built surrounding structures | Existing with alterations to the original structure. Requires proper preservation and maintenance. | Originally used as a mosque |

| Hussaini Dalan | RAJUK listed | Accessible and partly visible from a distance | Existing with alteration to the original structure. Requires proper preservation and maintenance. | Originally used as the religious center for the Shia community |

a. Listed by RAJUK (Capital Development Authority) as a heritage site.

b. Listed by the Department of Archeology for protection as a heritage building.

|

|

|

Figure 1. Pre-Mughal Dhaka. Source:Islam, 1996b . |

|

|

|

Figure 2. Layout of Shankhari Bazaar in the Late 18th Century (Ahmed, 2012 ). |

|

|

|

Figure 3. Hussaini Dalan in 1982. Source: Aga Khan Visual Archive, MIT. |

|

|

|

Figure 4. Kartalab Khan Mosque in 1982. Source: Aga Khan Visual Archive, MIT. |

|

|

|

Figure 5. Demarcation between pre-Mughal and Mughal Dhaka (Dani, 1962 ). |

|

|

|

Figure 6. Land Use Plan of Dhaka during the Mughal Period (Ahsan, 1991 ). |

|

|

|

Figure 7. Schematic Layout of the Mughal Quarters in old Dhaka. Source: based on Mowla, 1997b . |

|

|

|

Figure 8. Chota Katra from the River Bank in 1875. Source: Department of Archeology, Bangladesh. |

|

|

|

Figure 9. South Wing from the Court Yard of Bara Katra in 1870. Source: British Museum. |

|

|

|

Figure 10. Land Use of Dhaka in 1910 and 1945 (Ahsan, 1991 ) and Land Use of Dhaka in 1962 (Islam, 1996b ). |

|

|

|

Figure 11. Land Use Map of Dhaka in 1995 (Islam, 1996b ). |

|

|

|

Figure 12. Historic Artifacts in Dense Settlements (Hossain, 2007a ). |

|

|

|

Figure 13. Historic Artifacts in Dense Settlements (Hossain, 2007a ). |

|

|

|

Figure 14. Mughal Monuments in Old Dhaka: 1. Tanti Bazaar, 2. Shakhari Bazaar, 3. Lakhsmi Bazaar, 4. Binat Bibi Mosque, 5. Old Fort, 6. Dhakeshwari Temple, 7. Khan Mohammad Mridhas Mosque, 8. Lalbaghfort, 9. Bara Katra, 10. Chota Katra, 11. Chauk Bazaar Mosque, 12. Star Mosque, 13. Kartalab Khans Mosque, 14. Hussaini Dalan. |

|

|

|

Figure 15. Road approaching Choto Katra (Hossain, 2007b ). |

|

|

|

Figure 16. Courtyard and the Southern Wing of Bara Katra (Hossain, 2006 ). |

|

|

|

Figure 17. Existing Riverside of Chawkbazar and Lalbagh Area. Source : http://dhakadailyphoto.blogspot.com/2007_05_01_ archive.html . |

|

|

|

Figure 18. Layout of row houses at Shankhari Bazaar in 2006 (Ahmed, 2012 ). |

|

|

|

Figure 19. Existing condition of the Row Houses at Shankhari Bazaar (Bahauddin, 2010 ). |

|

|

|

Figure 20. A traffic route for the heritage walk (Hossain, 2007b ). |

|

|

|

Figure 21. Lagbag fort complex after conservation (http://www.bpedia.org/T_0200.php ). |

|

|

|

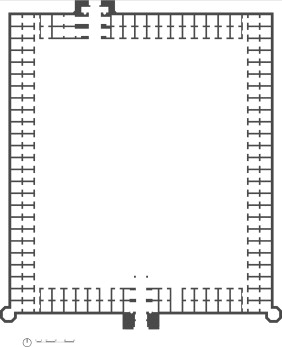

Figure 22. Original form of barakatra with enclosed courtyard (Hossain, 2008 ). |

|

|

|

Figure 23. Ground floor plan of choto katra with an enclosed courtyard. |

|

|

|

Figure 24. Street elevation of Shankari Bazaar. Source : Urban Study Group. |

7.3. Access, exposure, and buffer

The Mughal buildings along the river bank already lost their original approach from the riverside and inner city because of the change in the river course and the newly imposed settlements on the fabric. The access linkage between the artifacts and the ghats should be improved to ensure an interesting approach from the river bank. Many Mughal buildings in old Dhaka had substantial open spaces, such as gardens and courts, which are now mostly encroached by newly built informal settlements. These settlements create obstacles to the visibility and access to the historic artifacts. Some of such open spaces were recovered during the conservation of Lalbagh Fort and Khan Mohammad Mridha Mosque. Recovering such open spaces in other historic buildings, such as Bara Katra and Choto Katra, is needed to ensure proper access and visual exposure, as well as to establish a substantial buffer for the historic buildings. View corridors may also be created through the fabric to get a distant and interesting view of the Mughal buildings (See Figure 21 , Figure 22 ; Figure 23 ).

7.4. Preserving the street elevation and the river front

The riverside elevations of the Mughal buildings need to be recovered to reveal the identity and integrity of the historic city. The street front should be considered as an important part of integration because the continuous façade of old settlements, such as Shankhari Bazaar and Tanti Bazaar, represent a strong urban character. The facades of the historic buildings should be preserved and restored to maintain the continuity of the riverfront and the street elevations of the old city (See Fig. 24 ).

7.5. Civic management

One of the major constraints to manage the conservation of the Mughal buildings is the complex landownership pattern. The Katras5 are in dispersed form of submission6 , which resulted in the lack of interest by concerned parties to invest in the proper maintenance of the buildings. Owners, users, and all stakeholders need to unite on a common platform to generate collective action that will protect the heritage properties. Traditional community-based management systems that have substantial control over the local society may be considered, along with government systems, to manage urban services from the neighborhood to city levels.

7.6. Relocation and adaptive reuse

The relocation of informal shelters and commercial establishments may be considered outside the old city to reduce densities. Substantial parts of Bara Katra and Choto Katra are currently used as warehouses and wholesale areas. After restoration, these historic buildings, such as Lalbag Fort, may not need to be converted into museums. The historic buildings can be used for sustainable purposes, such as serving as hotels, restaurants, souvenir shops, art galleries, craft shops, libraries, and administrative buildings. The relocation of the Central Jail may introduce huge possibilities for the area to reduce emerging pressure on the old fabric.

8. Epilogue

Old Dhaka, as a historic city of more than 400 years, should be considered for comprehensive urban schemes to integrate its historically sensitive Mughal settlements. This study initially examines the transformations of Mughal City to understand its heterogeneous tissue. Preventive strategies are mainly emphasized as intermediate guidelines to manage the decay and damage of the old fabric. A substantial buffer, construction restrictions, and traffic restrictions may not only reduce the possibility of physical deterioration but also ensure proper access and visual exposure. The preservation of building envelops is highlighted to maintain street and river side elevations to strengthen the state of authenticity and integrity at the urban level. Different degrees of interventions may be synthesized for different Mughal monuments to avoid rigidity in architectural conservation. Therefore, conventionally conserving the historic artifacts in the area is unnecessary. The integration of Mughal monuments within the present urban fabric through the development of contextual circulation patterns can also promote interrelation among monuments. Managing the urban dynamics to control the increasing pressure on establishment functions that cause rapid transformation is important. Policy and plans should be formulated to focus on the adaptive reuse of monuments and thus safeguard historical patrimony and ensure social and economic viability.

References

- Ahmed, 2012 Ahmed, Iftekhar, 2012. A Study of Architectural Heritage Management by Informal Community bodies in Traditional Neighborhoods of Old Dhaka. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis. National University of Singapore.

- Ahmed, 1986 S.U. Ahmed; Dacca: A Study in Urban History and Development; Curzon, Press, Dhaka (1986), p. 1986

- Ahsan, 1991 R.Majid Ahsan; Changing Pattern of the Commercial Area of the Dhaka City; Sharif Uddin Ahmed (Ed.), Dhaka Past Present Future, The Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka (1991)

- Akbar, 1988 J. Akbar; Crisis in the Built Environment—A Case Study of Muslim Cities; Concept Media Pte Ltd, Singapore (1988)

- Bahauddin, 2010 Bahauddin, Md, 2010. Conservation of Shakhari Bazar. Unpublished training Report, submitted at Lund University Sweden.

- Chowdhury and Faruqui, 1991 A.M. Chowdhury, Shabnam Faruqui; Physical Growth of Dhaka; Sharif Uddin Ahmed (Ed.), Dhaka Past Present Future, The Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka (1991)

- Dani, 1962 A.H. Dani; Dacca—A Record of its Changing Fortune; Asiatic Society, Dhaka (1962)

- Denzin and Lincoln, 2000 N.K. Denzin, Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research (SecondEdition), Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA (2000)

- Gupta, 1989 N. Gupta; Urbanization in South Asia in the colonial centuries; Sharif Uddin Ahmed (Ed.), Dhaka Past Present Future, 1989, The Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka (1989), pp. 595–605

- Hossain, 2006 Hossain, Mohammad Sazzad, 2006. Conservation and Management of Bara Katra. Unpublished training Report submitted at Lund University Sweden.

- Hossain, 2007a Hossain, Mohammad Sazzad, 2007a. Planning the Heritage Cities—a case for Dhaka. Published in the Society Architects and Emerging Issues, published by Commonwealth Association of Architects (CAA) & Institute of Architects of Bangladesh (IAB).

- Hossain, 2007b Hossain, Mohammad Sazzad, 2007b. Revitalizing the Mughal settlements in Old Dhaka, Published in Protibesh, Journal of the Departmetnt of Architecture. BUET, Dhaka. Vol. 11 (2). pp. 49–54.

- Hossain, 2008 Hossain, Mohammad Sazzad, 2008. Preventive Maintenance Strategy of Bara Katra in Protibesh. Journal of the Department of Architecture, BUET, Dhaka. July 2008, Vol. 12 (2). pp. 5–14

- Islam, 1996a Islam, N., 1996a. Megacity Management in the Asian and Pacific Region. In: Giles Clarke, Jeffry, R. Stubbs (Eds.), Vol. 2. Megacity Management in the Asian and Pacific Region. ADB.

- Islam, 1996b Islam, N., 1996b. Dhaka from City to Mega City: Perspective on People, Places, Planning and Development Issues: Urban Studies Programme. Department of Geography. University of Dhaka. Reprint.

- Islam and Khan, 1964 Nazrul Islam, F. Karim Khan; High class residential areas in Dacca city; The Oriental Geographer, Vol. viii (1964)

- Landman, 1988 W.A. Landman; Navorsingsmetodologiese Grondbegrippe/Basic Concepts in Research Methodology; Serva, Pretoria (1988)

- Mowla, 1997a Q.A. Mowla; Settlement texture: study of Mahalla in Dhaka; Journal of Urban Design, 2 (3) (1997), pp. 259–275 (U.K.)

- Mowla, 1997b Mowla, Q.A., 1997b. Morphological evolution of Urban Dhaka. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis. University of Liverpool. UK.

- Nilufar, 2011 Nilufar, Farida, 2011. Urban Morphology of Dhaka City: Spatial Dynamics of Growing City and the Urban Core, an Article published in 400 Years of Capital Dhaka and Beyond, Vol. III, Urbanization and Urban Development, Published by Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, Dhaka. pp. 187–210.

- Taifoor, 1956 Syed Muhammed Taifoor; Glimpses of Old Dhaka; Pioneer, Dhaka (1956)

Notes

1. Historic research is based on a description of the past. This type of research includes, for instance, investigations that record, analyze, and interpret events of the past with the purpose of discovering generalizations and deductions that can be useful to understand the past, present, and, to a limited extent, the future (Landman, 1988 ).

2. Qualitative research is a multi-method in terms of focus because it involves an interpretive, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. Qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings and attempt to make sense of or interpret phenomena in terms of the meaning people bring to them. Qualitative research involves studies that use and collect a variety of empirical materials. Qualitative research is especially effective in obtaining culturally specific information about the values, opinions, behaviors, and social context of a particular population (Denzin and Lincoln, 2000 ).

3. The roads had no names, but the mohallas had names at that time. The roads were named after the establishment of the Dhaka Municipality in 1864; the former one is the Patuatoli-Islampur-Mughal Toli Road, and the latter one seems to be the Nawabpur Road (Source: Islam and Khan, 1964 ).

4. The proposed traffic route in the existing layout starts as a continuation of Azimpur Road and approaches Lalbag to establish a link between the city center and the Lalbag group of monuments. The route continues towards Chauk through Waterworks roads to establish a link with Katra buildings. The later phase of the route permits the choice of a river trip launched from Swarighat. A one-way access loop for vehicular movement can be introduced around the artifacts to reduce regular traffic congestions on the roads. Chompatuli Lane may be expanded in width to establish a proper linkage between Bara Katra Lane and Chota Katra Ghat Road through Swoarighat Road and Chompatuli Lane. The narrow part of Chota Katra Ghat Road and Debidas Ghat Road should be expanded to ensure easy traffic movement. As far as possible, some space may be cleared around the artifacts to increase accessibility and visibility (Hossain 2007b ).

5. Katra , an introvert shopping area around a courtyard, includes living spaces for travelers (Mowla, 2003)

6. In a dispersed form of submission, three parties share a property: one party uses it, a second party controls it, and a third party owns it (Akbar, 1988 ).

Document information

Published on 12/05/17

Submitted on 12/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?