Abstract

Vernacular buildings across the globe provide instructive examples of sustainable solutions to building problems. Yet, these solutions are assumed to be inapplicable to modern buildings. Despite some views to the contrary, there continues to be a tendency to consider innovative building technology as the hallmark of modern architecture because tradition is commonly viewed as the antonym of modernity. The problem is addressed by practical exercises and fieldwork studies in the application of vernacular traditions to current problems. This study investigates some aspects of mainstream modernist design solutions and concepts inherent in the vernacular of Asia, particularly that of the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT). This work hinges on such ideas and practices as ecological design, modular and incremental design, standardization, and flexible and temporal concepts in the design of spaces. The blurred edges between the traditional and modern technical aspects of building design, as addressed by both vernacular builders and modern architects, are explored.

Keywords

Building technology ; Tradition-modernity ; Innovation ; Vernacular architecture

1. Introduction

Currently building technology and sustainable design are considered as fundamental to the growing field of contemporary architecture. Practicing architects have a challenging responsibility to design buildings that are environmentally sustainable with the change in the global concern regarding the use of energy and resources (Wines and Jodidio, 2000 ; Cox, 2009 ; Friedman, 2012 ). This new responsibility has prompted a sensible shift in trend from a biased preference of eye-catching, institutionalized building forms to more organic, humble, yet energy-efficient vernacular forms. Additionally, the local forms of construction capitalize on the users׳ knowledge of how buildings can be effectively designed to promote cultural conservation and traditional wisdom (Oliver, 2003 ; Rapoport, 2005 ).

A number of practitioners are also inspired by building traditions, given that the local vernacular forms have proven to be energy efficient and “green,” honed by local resources, geography, and climate (Fathy et al ., 1986 ; Curtis, 1996 ; Lewis, 2014 ). However, given the diversity of vernacular architecture in the global context, the techniques or technology-based research on vernacular architecture remains surprisingly limited beyond performance-based examples. This limitation stems from multiple factors, one being fundamentally hinged on the conventional notions of “traditional” and “modern” in the discourse of architecture.

In the discussion of vernacular architecture, ambiguities arise from the meanings of certain terms and concepts. The words “modern” and “traditional” are often considered as being in fundamental opposition to each other. One tends to suppose that vernacular architecture is a kind of traditional architecture, distinct from modern architecture. In this dualist view, the traditional is taken to be inept or technologically crude (Bourdier and Trinh, 1996 ).2 This view not only establishes the vernacular as a distinct category, but also implies that it is nearly immutable and static, “indeed unimprovable, since it serves its purpose to perfection” (Tzonis et al., 2001 ).3 However, a fragmented volume of empirically grounded works on Asian vernacular dwellings suggests that sly details, materiality, as well as adaptive and smart-space solutions and techniques are deployed ingeniously as much (or more so) by the local unknown builders in a traditional setting as by modern illustrious architects.

These findings are shunned by the limited development in research that explicitly addresses the application and use of vernacular knowledge and skills in contemporary architectural examples (Vellinga and Asquith, 2006 ).

1.1. Scope and approaches

Drawing upon the limitations, this study examines a specific type of vernacular architecture, which is shown to be consistent with contemporary design thinking and practice. The findings are based on a primary fieldwork4 conducted in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT), the hilly border region in the southeastern part of Bangladesh. From an ethno-linguistic perspective, CHT is the most complex region of Bangladesh,5 and this complexity is mirrored in the local hill settlements with distinctive, historically perfected features exhibiting ecologically sound lessons for sustainable or green architecture. Mainly dubbed as “primitive” or “indigenous” dwellings, the atypical upland examples of the Mru people are not seriously researched, remain outside architectural references, and are limited to casual comments and picturesque images (Ara and Rashid, 2003 ). Traditional hill-ethnic dwellings in the Chittagong Hills generally share striking similarities with some typologies of Southeast Asian traditional architecture rather than South Asian vernaculars (Brauns and Löffler, 1990 , 60).

Starting with reviews on the construction of modernism and its fuzzy boundaries in the context of architectural development, the follow-up sections of this paper illustrate how environmental issues and technology are manifested in Asian vernacular examples. Although the approach is largely qualitative, drawings and photos are used sequentially and analytically to ascertain the temporal dynamics of technology and spaces (Grills, 1998 ; Yin, 2003 ; Van Maanen, 1983 ; Ball and Smith, 1992 ). Analytical points are grouped under themes and then discussed under thematic parts. The approach avoids argumentative points and leans on similarities rather than comparative notes. Selected Asian vernacular examples, aside from the CHT, are drawn into the discussion to illustrate themes. This work has two main objectives. First is to contribute to an important debate on the relevance of any edge between the traditional and modern aspects of design decisions and technology. This perceived gap is a limiting factor in appreciation of local forms and technology. Second is to highlight materiality, design innovations, and ingenuity in local architecture, particularly in Asian vernacular examples, that are at par with or are more instructive than that in modern buildings. This context opens up possibilities for embracing vernacular as a model for technically honed sustainable forms in the 21st century.

1.2. Context, material, innovation, and technology: path to modern architecture

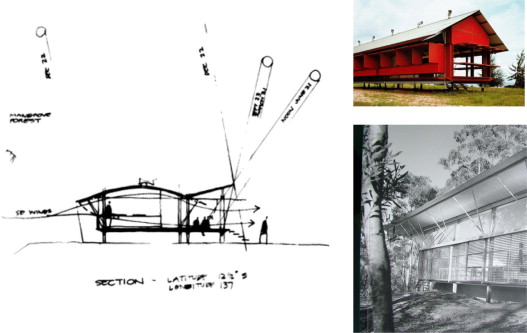

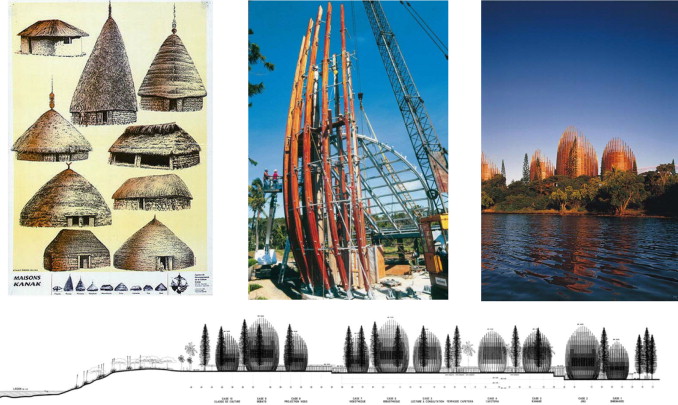

The concept of modernism in architecture is difficult to define despite being clearly conceived in opposition to late 19th century historicism, and rejecting historical precedents and traditional methods of building (Ching et al ., 2011 ; Curtis, 1996 ). Despite showing strong preferences for industrial building materials and production, the buildings of modern style have simple forms, visually expressive structures, abstract ornamentation, and functionality, in that there is a strong rational basis to the building volumes. Modernism redefined the aesthetic appreciation of buildings to value clarity and to highlight the philosophy “less is more” in appearance and detail. Paradoxically, however, the early 20th century pioneers of the movement also exhibited strong preferences for nature, environmental factors, structural precision, and material integrity – many of the features inherent in vernacular architecture. Wright talked about organic architecture in 1908, long before the term “ecology” became fashionable. He pioneered the ideas that buildings should be extensions of the environment and that their three-dimensional forms should depend upon the properties of materials (Wines and Jodidio, 2000 , 22–23). Modern masters, such as Corbusier and Aalto, aimed to build spiritually reviving environments in which man could live in harmony with nature (Menin and Samuel, 2003 , 73,81). Aalto believed that the natural energy of light and air should filter into the designed spaces and thus developed a variety of techniques to let natural light into interior spaces. Le Corbusier was well known for his deep concern for “sun, space, and greenery” in his designs. The Australian architect and Pritzker Prize winner Glenn Murcutt is known for designing earth-friendly structures (Figure 1 ) that are unpretentious, comfortable, and economical. His design approach responds to the site, the wind, and the sun, and he professes to share the aboriginal philosophy “touch the earth lightly.” In another contemporary example, Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Centre (Figure 2 ), Renzo Piano creates a seemingly impossible link between the high-tech and the vernacular through a successful fusion of material, form, technology and planning ideas borrowed from the vernacular knowledge of the Kanak tribe (Wines and Jodidio, 2000 , 126).

|

|

|

Figure 1. “Touch this earth lightly” – a modernist approach exhibits sustaining the ecology, sensitivity to the local landscape and particulars of the site. Left: Murcutt’s sketch relating building to the site. Marika-Alderton House , NSW 1991–94, Fromonot, Glenn Murcutt, p. 218. Top right: Designing on unspoiled landscape, Fromonot, Glenn Murcutt, p. 219. Bottom right: Simpson-Lee house. Cover Fromonot, Glenn Murcutt . |

|

|

|

Figure 2. Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Centre (New Caledonia, 1991/1998): The Centre followed two main guidelines – Kanak vernacular knowledge in construction competencies, on the other hand making use of modern materials, such as glass, aluminum, steel and advanced lightweight technologies (in addition to traditional materials wood and stone). These buildings strongly express the harmonious relationship with the environment that typifies the Kanak-tribe culture. Source : Renzo Piano Building Workshop. |

Technological perfection in Mru architecture, which is a perceived “primitive” architecture, is similarly derived from an understanding of the locally available materials and the constraints of the site, climate, and environment. The traditional design approaches do not differ significantly from the modernist design concepts and concerns just outlined. The durability of construction of a hill house without nails, screws, or wires was a noticeable point that anyone who visited the hill dwellings could hardly miss. Löffler describes:

Props and thong bindings offer ample support for a Mru house. Not only can dozens of people sit on the floor at the same time; they can dance on it and jump on it in rhythm. During the monsoon season these houses hold up repeatedly to storms. (Brauns and Löffler, 1990 , 70)

An earlier historical record by a colonial administrator of the hills presents a similar observation:

A hill house perched in an exposed position on the ridge or spur of a lofty eminence looks the frailest structure in the world; its strength however is surprising, and in spite of the fearful tempests that sometimes sweep over the hills, I never heard of a house having fallen or being injured by the wind. (Lewin, 1869 , 15)

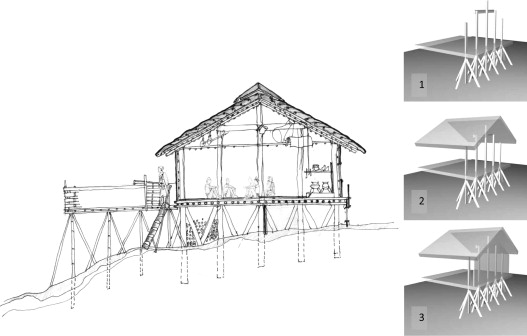

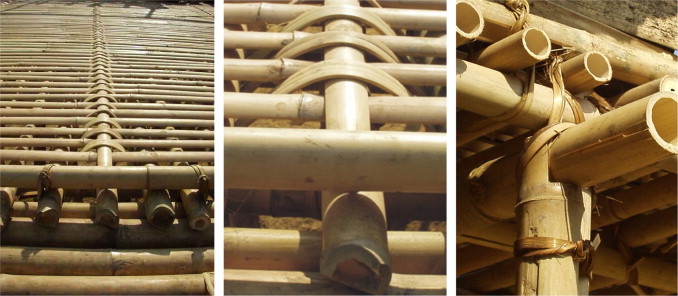

Building a house on stilts shows the ingenuity of the builders in solving the physical and natural constraints of the site. The stilt construction shows a high degree of specificity unique to this hilly region. Broadly, the stilt construction of CHT is distinguished from other pile structures of Southeast Asia by the three-dimensional quality of the propped structural members (see Figure 4 ). Geographical and climatic constraints are two important considerations in the construction of such pile structures. The perpendicular posts are propped up from three sides, making it possible for the structure to counteract any lateral sliding in case of soil shifts or earthquakes, given that mild earthquakes frequently occur in the region. Two earthquakes were recorded in 1950 and 1955 but no report of any damage to the hill dwellings was recorded (Ishaq, 1971 , 20). The indigenous solution provides substantial rigidity to the overall structure in balancing heavy wind load prevalent on high mountainous regions (Figure 3 ; Figure 4 ). Technicalities are also evident in the ingenious construction details. The lashing or clipping methods, in the absence of nails, used in stilt dwellings (Figure 5 ) is common in Southeast Asian vernacular examples. The lashing method is very popular for the recycling of materials and members for the addition, extension, relocation, and quick rebuilding of the house (Dawson and Gillow, 1994 ; 12; Knapp, 2003 , 263, 281; Waterson, 1990 , 74). Aside from structural logic, the material-logic is also intriguing in Asian vernacular examples.

The bamboo is literally the stuff of life. He builds his house of bamboo; he fertilizes his fields with its ashes; of its stem he makes vessels in which to carry water; with two bits of bamboo he can produce fire; its young and succulent shoots provide a dainty dinner dish; and he weaves his sleeping mat of fine slips thereof. (Lewin, 1869 , 9)

|

|

|

Figure 3. Modernist space – a flexible plan with freestanding pillars and movable walls. Left: The grid of the column layout in a Mru dwelling. Sketch by Author. Right: Maison Domino and the grid of the column in the free plan. Adapted from Le Corbusier selected drawings , p. 16 and p. 22. Sketches by authors. |

|

|

|

Figure 4. Five pillar construction. Left: A Mru house section. Right: Construction process starts from the two gable sides where 5 structural posts in two rows stand freely from enclosing panels. After setting structural posts and floor, roof is added. Enclosing walls come much later in phase three. Sketch & CAD analysis by authors. |

|

|

|

Figure 5. Work of art or innovative building technology? Photograph showing the method of clipping without nails and thongs to join loose construction members in the char (open raised terrace). Photo: authors. |

In the hills, the use of the bamboo in every aspect of life can still be observed. The use of this natural material in building construction has other implications, such as on the size of a dwelling. Although all Mru dwellings are comparatively larger than the huts or dwellings of the Bangali and other ethnic groups,6 the selection of materials depends on the strength and properties. The resultant size of the dwellings thus varies. The size of the public space, that is, the kim-tom or the living space, may range from approximately 23 m2 in a bamboo built dwelling, to approximately 60 m2 for a wood built dwelling. Thus, the material and its structural properties influence the size of the built form. The material-logic further establishes vernacular against the notion that native dwellings are irrational.

Bamboo is a common building material for traditional construction in most regions of Southeast Asia, whereas approximately half of the more than 700 species of bamboo known worldwide can be found. In the current trials of tensile strength, bamboo surprisingly outperforms most of other materials, even reinforcement steel. Bamboo achieves its strength through its hollow, tubular structure. The lightweight structure makes bamboo easy to harvest and transport. Owing to its incredibly rapid growth cycle and capability to grow in various areas, bamboo is considered as an economic construction material. Research indicates that bamboo structures have high endurance against storms and earthquakes, which are very common in Chittagong Hills (Dawson and Gillow, 1994 ).7 Bamboo has other advantages as a construction material. It produces no waste. It is a sustainable organic material that does not require much labor. It can be sliced and flattened easily with the simplest of tools. The shell can be chopped into suitable lengths. It can be split to produce half culm sand split-peeled to make binding or lashing materials. Bamboo splines can be woven to make partitions that are capable of breathing and screens that enable-diffused lighting. Conversely, bamboo has disadvantages, such as its susceptibility to buckling and limited resistance to wet soil. However, details can be worked out to solve these problems. The sophisticated technical details in bamboo that have been worked out to perfection in Mru architecture reflect the adaptability of Mru building practices to their native landscape, climate, topography, as well as available means and tools (Ara and Rashid, 2003 ).

1.3. Freeplan: pilotis and fluid space

One had therefore a structural system – skeleton – completely independent of the functions of the house plan. This skeleton simply carries the floor and the staircase. It is made of standard elements, combinable with each other, which permits great diversity in the grouping of houses. (Broadbent, 1973 , 47)8

Modern architecture is widely accepted to enable flexibility in design, often resulting from structural sophistication, such as in posts and beams as opposed to load bearing construction, portability of elements, compactness, standardization, prefabrication, and economy of structure. These features are commonly the result of technical developments. Modern practice increasingly uses smart design components that can be substituted, upgraded, replaced, maintained, or repaired.

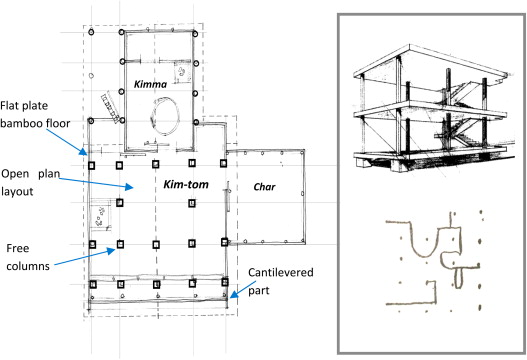

Walls are frequently movable and removable that is, non-load bearing, as facilitated by their modular design. Many of the same characteristics are found in Mru architecture. The vision of Domino flat plate with free columns without beams (Sandaker et al., 2011 ), which significantly influenced the development of a novel structural system during the modern architectural period and beyond, is clearly used in indigenous Mru dwellings (Figure 3 ). The thick triple layered bamboo floor of the Mru serves as a flat plate system that resists the upward shearing impact of columns.

The Mru building process is mostly standardize, such that most of the elements are made on the ground and then assembled together on site to create the final form. The walls are non-load bearing and stand free of the structural posts parallel to the gable ends in the public space. Along the gable ends, five pillars are found in the kim-tom irrespective of whether the construction is of bamboo or wood. The five posts are erected in two rows, flanking the core space of kim-tom in between. On the free gable end side of the kim-tom , a part of the floor space juts out in a cantilever from the structural posts, usually over the steep slope side of the site. The cantilever usually varies from approximately1 m to 1.5 m. The five pillars divide the space into approximately four parts, giving a flexible but precise reference grid for organizing other elements, such as the openings.9

The five-pillar arrangement has certain direct technical advantages (Figure 3 ; Figure 4 ). By increasing the number of posts, the roof load is more evenly distributed, thereby increasing the structural rigidity of the form. In houses of wooden construction, increasing the number of posts makes it possible to span a given space using tree trunks with smaller diameter. Builders generally reported that no exception to the five-pillar scheme exists. However, one unusual case refutes the universality of the rule. In the case of three pillars, 450 mm diameter tree trunks are used. This case possibly indicates that the larger diameter trees were once plentiful, and the scheme might have been prevalent. However, practical constraints, such as a shortage of larger trees and difficulties in handling them, may have resulted in a change of practice through which the five-pillar scheme came to prevail. A similar transformation might have occurred in southern China. The chaundau framework or five-pillar arrangement is also thought to have evolved in response to a shortage of timber of sufficient size for post-and-beam construction ( Knapp, 2000 , 86).

The elements of support in Mru houses are separated from the elements of enclosure. In the more private space, that is, the kimma (bedroom), the walls are tied to the structural posts and may either be exposed outside or stand within the enclosure. The structural logic of the construction is integrated with the function of the space, and the treatment of the cantilevered part, which projects from the five posts on gable end with a more porous slat grid work, is ingenious. This practice reduces dead load on the jutting part and creates a utilitarian extended floor that can be used as an aisle for storing agricultural items. Air from beneath the floor thus flows in through the open grid work and moderates humidity.

2. Expandable form and space

In contemporary design practice, researchers increasingly emphasize “smart architecture”, that is, architecture with an organic presence that is capable of growing according to the changing needs of the users:

The time factor and the fact that life is enacted in dynamic processes needs incorporating into the architectural design. A process-based architecture of this order brings about a process rather than a finished article, a set of possibilities that puts the product aspect in the hands of its users. … It does not need to be an immaterial, virtual architecture. On the contrary, the presence of a physical, spatial structure always will be a necessary condition for potential use. It is the form that is no longer stable, that is ready to accept change. Its temporary state is determined by the circumstances of the moment on the basis of an activated process and in-built intelligence and potential for change. (Hinte, 2003 , 130–133)

However, this description is not the only hallmark of what we define as modern architecture. This process-based incremental growth has long defined vernacular architecture, sometimes with more rigor and sophistication than generic modern architectural designs in which it has only been marginally evident.

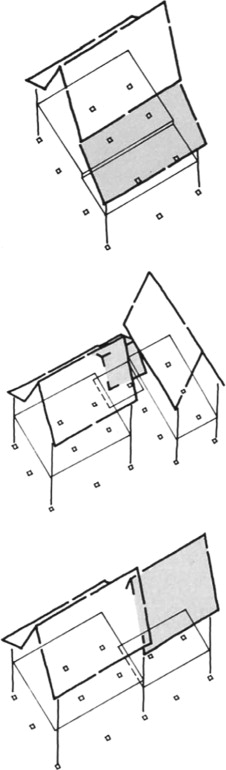

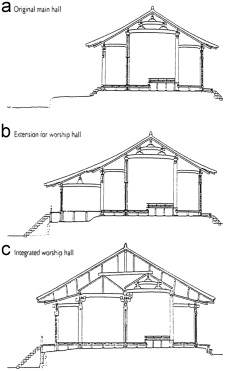

The traditional Malay house, the bumbung panjang , 10 shows sophistication and an additive system. The simple roof of the bumbung panjang is very efficient in making additions to the house ( Hashimah Wan, 2005 , 15). The core house is the rumah ibu , which is extended when addition is needed. This house satisfies the need of a small family. The rumah ibu can be big or small depending on the family. If the family expands or resources become available, a rumah ibu can be converted into a kitchen, whereas a larger rumah ibu is constructed. Additive elements can be attached to the main block with a distinction in the roof level as in the serambi gantung or gajah menyusu addition. Alternatively, these elements can have a transitional element, such as selang , 11 in the middle ( Figure 6 ; Figure 7 ). Addition by way of a common court is also possible. Addition can take place sidewise or parallel along the long axis or the short axis of the main structure (Lim, 1987 , 121).The Malay house achieves maximum utilization and minimum use of resources by adopting incremental housing solutions. The house is not a final product, but rather changes and grows along with the inhabitants. The connection of building modules through a terrace as the family expands is observed in a Bon Thai house. According to Marc Askew (cited in Knapp, 2003 )“ The modular house form and its adaptability is also present in Thai-Yuan [northern Thai] and southern Thai houses, despite differences in design details.”12 When a traditional Japanese house needs to be expanded, the expansion takes place in two directions. The long section can be extended, as in the Malay house, by the simple addition of a structural bay. A lean-to roof along the outer edge of the main roof is usually attached to the short section if a narrower addition is needed. Lean-to roofs, called hisashi , 13 are commonly used devices for the expansion of a Japanese house (Engel, 1985 ; 85; Young and Young, 2007 ). In traditional Japanese house types, the main and the extended roof are distinct. However, these features are indistinguishable in later versions, given that the lean-to roof became integrated with the whole extended roof structure (Knapp, 2003 ).14

|

|

|

Figure 6. Incremental dwelling: different addition possibilities in a Malay house. Addition by lean-to-roof block, addition by selang and expansion by adding similar but smaller bumbung panjang house form can be noted in the picture sequences. Lim, The Malay house , p. 120. |

|

|

|

Figure 7. Process of interior space expansion by hisashi in a Japanese structure. The sequences show how the interior space was expanded while the structure of the principal hall remained in its original condition. Knapp, Asia׳s old dwellings , p. 299. |

The additive quality is also observed in traditional Chinese houses. The smallest Chinese dwelling is composed of a single jian (bay), which is a multi-purpose space accommodating living, cooking, sleeping, and other activities. Space also has expandable qualities. The addition takes place by adding pairs of parallel columns and extending the overhead roof purlins ( Knapp, 1989 , 33-34). In a typical rural Bangali house, additional rooms are arranged perpendicular to the axis of the core rectangle (as in a courtyard dwelling in northern China), thus forming a court. The Mru dwelling15 also has a sophisticated additive quality. The kimma is the core house, which expands as the family׳s needs change. Connection of an additional module such as kim-tom , that is, the multi-functional living space, can occur with only a distinction at the roof level. More modules can be added to the verandah or machan, similar to the Malay house, if more space is needed. However, each extension takes place under a separate roof, and the long axis of the additive blocks is always parallel to the main axis of the core house called the kimma.

2.1. Minimalist house: the traditional and the modern

One important trend in modernist architecture is the minimalist design, which drew inspiration from the stylish simplicity of traditional Japanese architecture. In Japanese traditional houses, the spatial conception of the wall significantly differs from that in Western architecture, which is more dominant. In the absence of heavy walls, territorial claims are made through various symbolic expressions, such as by varying heights and differences in the materials used in finishing a floor. Delimitation of space is achieved through varying ceiling heights, changes in material finishes, placement of columns and beams, and even by a floor mat. In such architecture,“ boundaries are created [or] implied through a traditional code system and without the need to be defined by the explicit physical presence of wall” (Knapp, 2003 ).16

The definition of space enclosed not by physical boundaries. such as walls, but by mere “suggestion” is not something unique to the Southeast Asian traditional architecture. A similar observation is made by Bourdier about traditional Nuna villages in Africa. The uncovered cooking areas are set up in the open space and “are not clearly defined by walls, but simply suggested through a zone of packed earth” (Bourdier and Minh-Ha Trinh, 1985 , 57). In a single room, within a bahay kubo privacy, is a function of eye contact: One “disappears” or becomes “no longer present” by simply looking away (Knapp 2003). 17 When one is within the space but outside eye contact, one is within a private space. As Waterson cautions, the concept of privacy can prove to be completely different in many Southeast Asian societies. The Western lens can be inadequate to read a concept that is very much rooted in the social and cultural conventions of the dwellers (Waterson, 1990 , 170). In many of these societies, physical walls are non-existent simply because there is no need to have a wall, as social conventions quite adequately construct a non-physical wall by means of which privacy is maintained.

Apart from this complex relational feature between minimalism and the local perception of use and space, sophisticated optimized technology is also integrated into exemplary space saving physical solutions. In the hill, the traditional bamboo sliding panels as doorways outperform conventional swing doors in a very practical way. These lightweight sliding partitions, most unlikely modern details from a “primitive” dwelling, are made from thin bamboo splines weaved in the same way as stitching. In the absence of hinges, the sliding partitions can be constructed swiftly off site and be readily dismantled. When weaving the mat, the width is kept flexible, often exceeding the dimension of the gap left for the opening. This feature lends additional flexibility in constructing the screens without meticulous measurement. These mats are either secured freely in the cavity between the bamboo and wooden posts or hang and slide from top rails only. When sliding on a bamboo channel fixed on the ground, the screen is often made stiffer by anchoring to a bottom rail of bamboo. The thin exposed faces of the openings or cutouts in the bamboo panels are secured by edging with split or whole bamboo poles of smaller diameters that are bundled and clustered together. Horizontally laid bamboo poles, which are an integral part of the vertical frame securing the curtain walls, act as continuous skirting at the floor bottom and as top rails at the lintel level. Fixing of panels to the posts by lashing enables easy maintenance and replacement. This kind of ingenious solution creates not merely an optimized uncluttered space, but also an uninterrupted communally cohesive domain. 18

3. Conclusion

… what is needed at the beginning of the new millennium is an architectural perspective in which valuable vernacular knowledge is integrated with equally valuable modern knowledge… (Vellinga and Asquith, 2006 , 18)

The vision, though noted, is yet to be sculpted in the right direction. In current architectural discourse, a tendency in which contemporary examples are placed in a hermetic situation where traditional and modern architectural examples are displaced from one another, thereby subverting any possibility for transmission of ideas and lessons between the two despite emerging findings from local architectural case studies where technological innovations and environmental perception and knowledge are remarkably modern. Such tendency limits and slows the promise for the development of an ecologically inspired green /sustainable design-tuned architecture, though this appears to be a catchphrase now. The findings presented in this study do not propose utopian solutions from Asian vernacular examples that might be included in modern buildings. Rather, a few key merged notions between traditional and modern ways of building and construction are illustrated throughout the article. In doing so, we propose that ideas and issues be opened up for the exploration and identification of new directions in green/sustainable and innovative techniques, which might be channeled and filtered through local knowledge, practice, and wisdom as much as by new industrial innovations and emerging technology. Vernacular dwelling studies show a remarkable shift from the previous “image” and “notion” ideas of static old forms. By contrast, a section of current works is opting to highlight critical, creative, and procedural aspects of vernacular examples. This shift certainly lifts vernacular to a prominent position in architectural research, education and practice.

…if we understand…why a thing looks the way it does, or why it works the way it does, then we understand the principle, and that principle, not the form it produces, is transferable. (Glenn Murcutt, cited in Curtis, 1996 , 640)

In essence, this understanding is not so remote from the famous Miesian aphorism,“ Form is not the aim of the work, but only the result” (Fromonot, 2003 , 23).This result, as in the vernacular architecture of the Mru as well as in modern successful design practices, is hinged on some common dynamics. Any boundary between tradition and modernity is fluid and complex. The bypassed vernacular built solutions, such as material and structural sensibility, minimalism, modularity, adaptability, as well as tactile and temporality or fluidity, are essentially modern. Drawing upon the similarities in principles rather than in images, one can see the possibilities of transmission of ideas and techniques from traditional (in vernacular) to modern (as in contemporary examples) or from modern to vernacular in a two way directional process.

Needless to say, local vernacular examples offer a rich repertoire of architectural knowledge not only in the field of design, innovations, and sustainable techniques but also in other theoretical fields. Local solutions are obviously honed by culture and social logic (Rapoport, 2005 ; Oliver, 2003 ), thereby adding a deeper meaning to the given examples. Indeed, many of the defining criteria for modernist design (such as Le Corbusier׳s “five points of architecture”)19 that are often considered as radical innovations, are inspired by traditional or vernacular forms (Glancey, 2003 )20 in which social, cultural, spatial, physical, technological, and aesthetic factors combined into one complex definition.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Miles Lewis of Architecture Building and Planning (ABP), University of Melbourne , for his unwavering encouragement, useful critiques, and support for this work. Our gratitude to traveling companions MonKhia and PothiMong, for accompanying us to the remote CHT settlements. Lastly and foremost, deepest thanks to the Mru people in the Bandarban area, especially the karbaris of the ten hamlets, for letting us stay and for trusting and confiding in us. We would also like to thank Jean Pipite of Agence de Developpment de la Culture Kanak for granting the permission to use the photos showcasing Renzo Piano׳s work (Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Center ).

References

- Ara and Rashid, 2003 Dilshad Rahat Ara, Mamun Rashid; Rediscovering the vernacular architecture of the hill people: the Mru houses of the Chittagong Hill Tracts; J. Asiat. Soc. Bangladesh (Hum.), 48 (1) (2003), pp. 171–188

- Ball and Smith, 1992 M.S. Ball, Gregory W.H. Smith; Analyzing Visual Data, Qualitative Research Methods; vol. 24, Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA (1992)

- Bourdier and Minh-Ha Trinh, 1985 Jean-Paul Bourdier, T. Minh-Ha Trinh; African Spaces: Designs for Living in Upper Volta; Africana Pub. Co, New York (1985)

- Bourdier and Minh-Ha Trinh, 1996 Jean-Paul Bourdier, T. Minh-Ha Trinh; Drawn from African Dwellings; Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Ind (1996)

- Brauns and Löffler, 1990 Claus-Dieter Brauns, Lorenz G. Löffler; Mru: Hill People on the Border of Bangladesh; Birkha¨user, Boston (1990)

- Broadbent, 1973 Geoffrey Broadbent; Design in Architecture; Architecture and the Human Sciences; John Wiley & Sons, London, New York (1973)

- Ching et al., 2011 Frank Ching, Mark Jarzombek, Vikramaditya Prakash; A Global History of Architecture; Wiley, Hoboken, N.J (2011)

- Cox, 2009 Máire Cox; Living in the new millennium: houses at the start of the 21st century; Phaidon, London; New York, NY (2009)

- Curtis, 1996 William J.R. Curtis; Modern Architecture Since 1900; (3rd ed.)Phaidon Press, London (1996)

- Dawson and Gillow, 1994 Barry Dawson, John Gillow; The Traditional Architecture of Indonesia; Thames and Hudson, London (1994)

- Engel, 1985 Heino Engel; Measure and construction of the Japanese house; Books to Span the East & West (1st ed), C.E. Tuttle Co., Rutland, Vt (1985)

- Fathy et al., 1986 Hassan Fathy, Walter Shearer, Sultan Abd al-Rahman; Natural Energy and Vernacular Architecture: Principles and Examples with Reference to Hot Arid Climates; Published for the United Nations University by the University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1986)

- Friedman, 2012 A.V.I. Friedman; Fundamentals of Sustainable Dwellings; Island Press, Washington, DC (2012)

- Fromonot, 2003 Françoise Fromonot; Glenn Murcutt: Buildings+Projects, 1962–2003; (2nd ed.)Thames & Hudson, London; New York (2003)

- Glancey, 2003 Jonathan Glancey; The Story of Architecture. New/Foreword by Norman Foster Edition; Dorling Kindersley, London (2003)

- Grills, 1998 Scott Grills; Doing Ethnographic Research: Fieldwork Settings; Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, Calif. (1998)

- Hashimah Wan, 2005 Ismail Hashimah Wan; Houses in Malaysia: Fusion of the East and the West; (1st ed.)Penerbit Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Skudai, Johor Darul Ta׳zim (2005)

- Hinte, 2003 Ed van Hinte; Smart Architecture; 010 Publishers, Rotterdam (2003)

- Ishaq, 1971 Muḥammad Ishaq; Bangladesh District Gazetteers: Chittagong Hill Tracts; M. Ishaq (Ed.)Bangladesh Government Press, Dacca (Dhaka) (1971)

- Knapp, 1989 Ronald G. Knapp; China׳s Vernacular Architecture: House form and Culture; University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu (1989)

- Knapp Ronald, 2000 G. Knapp Ronald; China׳s Old Dwellings; University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu (2000)

- Knapp Ronald, 2003 G. Knapp Ronald; Asia׳s Old Dwellings: Tradition, Resilience, and Change; Oxford University Press, New York (2003)

- Lewin, 1869 Thomas Herbert Lewin; The Hill Tracts of Chittagong and the Dwellers Therein: With Comparative Vocabularies of the Hill Dialects; Bengal Printing Company, Calcutta (1869)

- Lewis, 2014 Lewis, J.I.M. 2014. The Native Builder. New York Times 2014 (cited 15.11.14). Available from 〈http://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/20/magazine/20murcutt-t.html?pagewanted=all〉 .

- Lim, 1987 Jee Yuan Lim; The Malay House: Rediscovering Malaysia׳s Indigenous Shelter System. [Pinang]; Institut Masyarakat, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia (1987)

- Menin and Samuel, 2003 Sarah Menin, Flora Samuel; Nature and Space: Aalto and Le Corbusier; Routledge, London; New York (2003)

- Oliver, 2003 Paul Oliver; Dwellings: the Vernacular House World Wide. Rev. Ed; Phaidon, London (2003)

- Rapoport, 2005 Amos Rapoport; Culture, Architecture, and Design, Architectural and Planning Research Book Series; Locke Science Pub. Co, Chicago (2005)

- Sandaker et al., 2011 Bjørn Normann Sandaker, Arne Petter Eggen, Mark Cruvellier; The Structural Basis of Architecture; (2nd ed.)Routledge, London; New York (2011)

- Tzonis et al., 2001 Alexander Tzonis, Liane Lefaivre, Bruno Stagno; Tropical Architecture: Critical Regionalism in the Age of Globalization; Wiley, Chichester (2001)

- Van Maanen, 1983 John Van Maanen; Qualitative Methodology; Sage, Beverly Hills (1983)

- Vellinga and Asquith, 2006 Marcel Vellinga, Lindsay Asquith; Vernacular Architecture in the Twenty-First Century: Theory, Education and Practice; Taylor & Francis, New York (2006)

- Waterson, 1990 Roxana Waterson; The Living House: An Anthropology of Architecture in South-East Asia; Oxford University Press, New York (1990)

- Wines and Jodidio, 2000 James Wines, Philip Jodidio; Green Architecture; Taschen, Köln; New York (2000)

- Yin, 2003 Robert K. Yin; Case study research: design and methods; Applied Social Research Methods Series (3rd ed), vol. 5, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, Calif. (2003)

- Young and Young, 2007 David E. Young, Michiko Young; The Art of Japanese Architecture; Tuttle Publishing, Tokyo; Rutland, Vt (2007)

Notes

2. Bourdier and Minh-ha, “Foreword” in Drawn from African Dwellings. According to the authors, the concept of tradition cannot be merely opposed to that of modernization without falling prey to the pitfalls of binary dualist thinking.

3. As quoted from Rudofsky, “Architecture without architects” in Tzonis, Lefaivre and Stagno [eds.], Tropical Architecture: Critical Regionalism in the Age of Globalization, p. 101.

4. The ethnographic and architectural findings, as well as the related visuals, used in this article draw upon a fieldwork conducted in 10 hamlets in Bandarban - the southernmost district of the CHT. The survey area was roughly dispersed around three major mouzas , Alikadam, Thanchi and Suwalak. Collection of ethnographic and architectural data was done through participant-observation involving interviews, photography, measured drawings(on-site), sketches and other forms of visual notes. Two Marma interpreters and guides helped in the interview process. Notes were audio recorded, written down and transcribed off-site.

5. Eleven indigenous groups, collectively known as the jhumias, reside in the CHT area. The ethnic communities (other than the Bangali) are Chakma, Marma, Tripura, Tangchangya, Khyang, Chak, Bawm, Lushai, Pangkhua, Mro[Mru] and Khumi. The three largest groups are the Chakma, Marma and the Tripura. Mru are the largest of the smaller groups. In general, language, culture, social structure, and traditional economic mode of production of the hill people are uniquely different compared with the Bangali, the mainstream people of the flood plains of Bangladesh.

6. The mainstream Bangla language speaking population of Bangladesh. Approximately 98% of the people of Bangladesh are Bangali.

7. For the Southeast Asian context, see Dawson and Gillow, Traditional Architecture of Indonesia , pp. 22–3.

9. Drawings and sketches from fieldwork, authors.

10. Various traditional houses classified mainly by their roof shapes can be identified in Peninsular Malaysia. The basic houseforms are the bumbung panjang , bumbung lima , bumbung perak and bumbung limas . The most common houseform is the bumbung panjang , characterized by a long gable roof. Retrieved from the website http://www.malaysiasite.nl/malayhouse.htm . See also Ismail, Malaysia: Fusion of the East and the West ,p 15.

11. A selang is a covered walkway. The two blocks remain distinct in roof line with a slightly lower roof over the selang.

12. Marc Askew, “Ban Thai ”: House and Culture in a transforming society’, in Knapp, Asia׳s Old Dwellings, p 263.

13. Lean-on lower roof for peripheral areas, such as verandah and wall openings, is common in a Japanese traditional house. See Engel, Measure and construction of the Japanese house , p 86.

14. Naonori, “Japan’s Traditional Houses,” in Knapp, Asia׳s Old Dwellings, p 298.

15. This study largely focuses on the architecture of the Mru (the largest of the smaller ethnic groups) in Bandarban hill region of the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT). Mru architecture is predominant and thriving in this southern most part of the CHT.

16. Naonori, “Japan’s Traditional Houses,” in Knapp, Asia׳s old dwellings , p. 307.

17. Augusto Villalon, “The Evolution of the Philippine Traditional House,” in Knapp, Asia׳s Old Dwellings , p 208.

18. It is interesting to note how technology is perfected to reach a social goal in the Mru architecture. Indeed, to be able to play a communal leadership role by hosting feasts and inviting guests is mush aspired by every member of theMru community. The kim-tom is designed as a large uninterrupted multi-purpose space with non-obtrusive sliding partitions to provide access and exit to other parts of the dwelling. Field notes, authors.

19. For example, Corbusier’s obsession with piloti is related to the uncovering of lake dwellings at Zurich in the mid-nineteenth century.

20. See influence of North African traditional forms on the practice and inspiration in Kahn and Corbusier. Glancey, Story of Architecture .

Document information

Published on 12/05/17

Submitted on 12/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?