Abstract

This paper used Active Radio Frequency Identification (Active RFID) technology to identify in which rooms fathers and their child tend to stay together and talk, and in which rooms they stay separately in seven one-child families living in Chinese urban apartment houses. The father was found to stay together with the child 0.5%–25% of the time when both father and child stayed at home. The use of the living room as the place in which the child stays with the father and talks was found to be highest (five out of seven families), followed by the dining room and the childs room. In over half of the cases when the child stays with the father in the living room or dining room and either of them talk, the child spoke over 1.6 times more than the father. However, in the childs room, the child always spoke less than the father, and the duration of the childs speech was less than 70% of that of the father. Findings showed that the instances in which child and father stay in different rooms fell into two groups. First, five of the seven subject fathers tended to stay in the living room, whereas the children stayed either in their room or in their parents' room to use the PC. Second, two fathers stayed in the studio or dining room to work, while their children stayed in the living room or their own rooms. For both groups, the duration of these periods of stay covered 30.0%–81.4% of the time during which both the father and child stayed at home.

Keywords

Father–child communication ; One-child family ; Apartment house ; Active radio frequency identification technology (Active RFID)

1. Introduction

In this study, we attempt to quantitatively identify the rooms in which fathers and their child communicate in urban Chinese one-child family apartments by using Active RFID and an audio recorder.

1.1. Background and previous studies

The Chinese governments one-child policy has produced over 100 million single-child families, many of which consist of a couple and one child, which is considered the basic family unit in urban China (Xinhua net, 2008). In this type of family, parents spend a lot of energy taking care of their child and place a lot of hope in him/her. The parent–child relationship is one of the most important relationships in the family. However, when the child becomes an adolescent1 , a gap often develops between parents and the child, especially between the father and child. A questionnaire investigation of 1855 urban middle school students and their parents in 14 Chinese cities showed that the father–child relationship is more estranged than the mother–child relationship. The children felt that they met and talked with their mother more at home, and they considered their mother to be a person who understands them (Feng, 2002 ). Another questionnaire investigation of 644 families with children over the age of 10 in Shanghai showed that the father spent less time communicating with his child than the mother, and less than 20% of the fathers sampled communicated with their children very often (Liu et al., 2005 ). Some research findings have also suggested that increasing face-to-face communication between fathers and their children could improve parent–child relationships (Chen, 2006 ).

Ideas for solving this communication problem may be learned from Japan, which has faced a similar problem in parent–child communication. Among Japanese homes, with increasing respect for personal privacy, the childs room, an individual room where the child can study, play, and sleep, has been a necessary component of the dwelling plan. However, the childs room has increasingly become an independent space that can be accessible directly from the entrance in many dwellings; thus, it can cause separation between children and parents. Reconsideration of the position of the living room, as well as the whole dwelling plan, is necessary to improve parent–child conversation (Central Council for Education, 1998 ). With this motivation, Tomoda et al. (1991) clarified childrens evaluation of the relationship between the childs room and the living room in a house comprised of individual rooms that may be accessed from the living room (L-hall type). Taniguchi and Ohgaki (2002) used questionnaires to show that communication durations tend to be longer in layouts where residents reach the stairs by passing through the living room. Using a questionnaire, Fujino and Kitaura (2006) classified parent–child communication into three types and clarified the relationship of each type of communication to the use of the family room. They found that the families of elementary school students who were on relatively intimate terms with their parents tend to use the family room frequently, whereas the families of high school students use the family room less frequently. Ohta and Yanase (1990) found that housewives feel that it was easy to talk with the family when doing housework in the kitchen, which directly faces the living room. Kitaoka and Machida (2001) investigated 261 housewives and 300 senior school students and found that the subjects tend to feel that it is easy to communicate with their family when the living room and dining room are adjacent.

Sawachi and Matsuo (1989) asked a group of mothers, fathers, and children to record their daily activities, in which room they carried out these activities, and when, investigating the time allocation on a basis of 30-minute periods. The researchers also identified, for each group of people (mother, father, and children), the probability of the room they stayed in and the living activities carried out every 30 min. Activities related to communication were concentrated between 19:00 and 21:00 for both mother and child.

Although many factors in the relationship between parent–child communication and dwelling spaces have been clarified by questionnaires, the actual communication, especially father–child communication, has not been recorded continuously and identified quantitatively by data on a per-minute basis. Additionally, knowledge of room use when fathers and children stay separated remains scanty. Comprehensive identification of the rooms in which both individuals stay together and talk, and the rooms in which they stay in when separated, as well as an understanding of the reasons for these, could form a basis for providing spatial conditions that increase opportunities for parent–child communication.

1.2. Active RFID investigation

There are three major ways to impart meaning in face-to-face communication among humans: body language, voice tonality, and words (Mehrabian, 1967 ). In face-to-face communication, while seeing each other is the most important precondition, talking is also an important part of the process. In the present study, we regard instances where a parent and child stay in the same room or adjacent rooms that open to each other (hereafter referred to as “connected rooms”) as events that have a high probability of visual and verbal contact (this kind of stay is hereafter referred to as “staying together”). Thus, the probability of face-to-face communication is quantified by the duration and frequency of a parent and child staying in the same room or connected rooms and the duration of speech that occurs during that same period. The use of certain rooms is quantified by the duration and frequency of subjects staying there. The duration and frequency of stays or speech are obtained by the continuous recording of each family members stay and speech in each room for seven individual cases using Active RFID and an audio recorder.

To identify room use precisely, we use Active RFID, which can continuously record what time each subject was in a room and in which room each subject stayed in without causing them much burden. Similar studies on activity recognition in houses using ring-type RFID (Enta et al., 2009 ), studies that examine the accuracy of slipper-type RFID (Enta et al., 2008 ), studies on the living patterns of elderly people who live alone (Qu and Matsushita, 2010 ) have been conducted. To the best of our knowledge, however, studies that focus on the communication between multiple residents are limited in number and scope.

Unlike studies that aim to clarify the universal behavior of a certain group of people by surveying large samples, this study focuses on a deeper understanding of specific room use for seven individual cases. This is a small sample, but for each case, when and in which room each subject stays and talks are recorded continuously for two to four days without burdening the subjects. The findings in this study may not be able to represent the behavior of most Chinese one-child families with adolescents, but it does show the characteristics of stays in room and speech of specific subjects over a specific period (students' summer vocation), which are realities that we should not ignore.

1.3. Purpose

The authors aim to clarify in which rooms the father and child tend to stay together and talk, and in which rooms they stay separately in seven one-child families using Active RFID devices and an audio recorder. The authors are interested in the following questions:

- In which room (or connected rooms) do the father and child tend to stay in together and talk?

- In which room do they tend to stay when they are separated (each stays in different rooms that are not connected)?

- Who is the main speaker when they stay in the same room?

2. Method of data collection

2.1. Devices

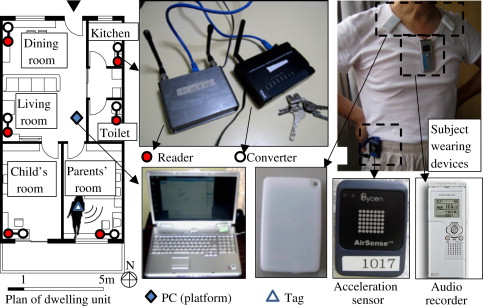

- Active RFID devices

The components of the Active RFID device are as follows:

- Active RFID Tag (tag)

- Active RFID Reader (reader)

- PC (platform)

- Wireless Ethernet Converter (converter)

The tag sent a signal with a unique ID on a per-second basis. Each reader was assigned a static IP and installed in each room of the dwelling unit. The converter connected the PC and readers through a wireless LAN. The PC recorded the IP of the reader that received signals from the tag, providing continuous data on when and in which room the subjects were present. Fig. 1 shows the configuration of the device.

|

|

|

Fig. 1. Configuration of the device. |

- Acceleration sensor

In order to fill in the missing values in the Active RFID data, an acceleration sensor was used; this device allowed the authors to correctly determine whether or not the subjects had moved.

- Audio recorder

An audio recorder was used to record the speech of the subjects. The recorded audio files were then transformed into data that only showed whether or not the subjects talked without determining the content of their speech. The survey was conducted after all subjects understood the above details and agreed to cooperate.

2.2. Investigation subjects and period

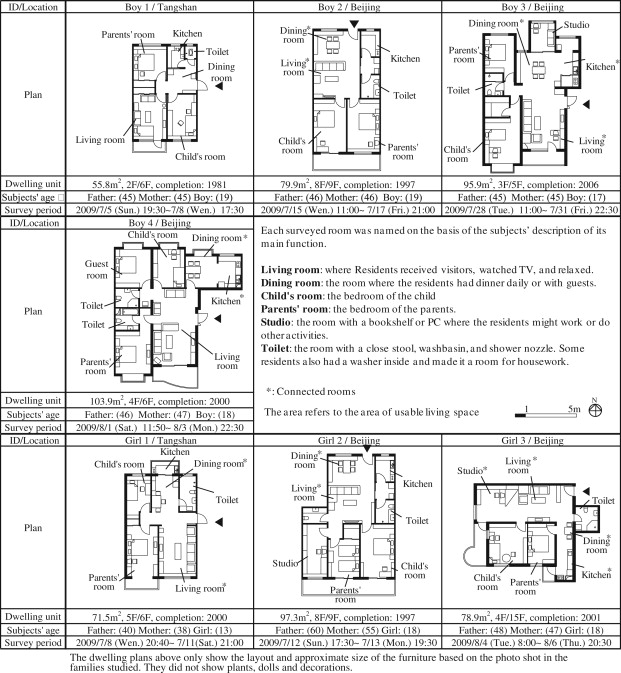

The investigation was conducted in Tangshan2 and Beijing, two prefecture-level cities in North China. Seven ordinary one-child families with adolescent children—four boys and three girls aged 13 to 19 years (subjects were identified by gender)—cooperated in our survey. Since the current study employed a case study design and did not aim to clarify the universal characteristics of adolescents or compare adolescents at different ages, no regard was given as to the age of the adolescents during subject selection.3

The subject dwelling units were common types found among the urban apartment houses of North China. Each subject dwelling unit had a living room, dining room, parents' room, childs room, kitchen, toilet, and, in some cases, a studio. On the basis of Chinese residents' general concept of rooms, the rooms in this study are described as a space, the main function of which is different from that of the adjacent space, regardless of whether or not it is enclosed by partitions. Thus, rooms in an open space were regarded as different rooms rather than a single room; such rooms are referred to as connected rooms in this paper (e.g., the living and dining rooms in the dwelling of Boy 2 in Fig. 2 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 2. Basic information about the surveyed families. |

It is interesting to note that, although there was only one child per family, the childs room was larger and better oriented than the parents' room in more than half of the subject families (Boys 1 and 3, and Girls 2 and 3). The parents said that this was because they wanted their child to have a more wholesome study environment.

2.3. Investigation flow

- Readers were installed in every room of the dwelling unit.

- An investigator wore the tags and moved among the rooms, adjusting the parameters of the devices to ensure that they correctly recorded which room the tag was in and when.

- The investigator instructed the residents on when and how to wear the devices.

- The investigation started after the investigator left. Every family member wore the tag, acceleration sensor, and audio recorder between rising and going to bed when inside the house. They also wrote down when they took the device off.

- The investigation lasted two to four days and ended when the investigator withdrew the devices.

- Upon clarification of the room in which subjects tended to stay most, the authors asked the subjects about the main activities they had performed in each room through a short interview.

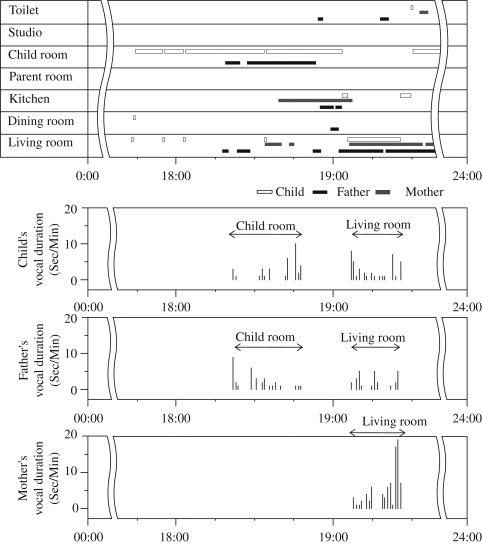

2.4. Time series data

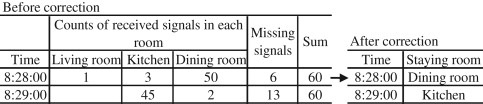

The database included location data and vocal duration. The location data was obtained by correcting the Active RFID data,4 (Fig. 4 ) which showed which room the residents stayed in and what time they stayed there between rising and going to bed. The time period during which the subject stayed at home between rising and going to bed is hereafter referred to as “stayed at home.”

Vocal duration is the number of seconds in a minute during which the subject talked; this was measured by calculating the average sampling value that showed the intensity of the sound per second in the recorded audio file by using a software tool.5 The voice of the speaker could be identified in all rooms except the kitchen, where the noise created in the process of cooking food was too loud. Thus, the authors did not calculate vocal duration in the kitchen. Fig. 3 illustrates a sample of the database.

|

|

|

Fig. 3. A sample of the location data and vocal duration during the period when parent and child stayed together (Boy 4 on August 3, 2009). |

|

|

|

Fig. 4. Example of data correction. |

3. Findings about communication in room use

3.1. Comparison of time spent together and speech between the child and their father and mother

The authors calculated the proportion of the duration that a child stayed together with their father (PDF ), their mother (PDM ), and with both of them (PDP ), for the total duration that s/he had stayed together with a parent.

The girls tended to stay together with their mother and spent very little time with both parents, whereas the boys tended to stay together with both parents, except for Boy 1, who stayed together with his mother for a relatively longer period. For all subjects, the duration that a child stayed together with his/her father tended to be less than the duration that she/he stayed together with the mother (PDF <PDM in 6 out of 7 cases, hereafter expressed as “6/7”).

Considering that the duration that both the father and child stayed at home (DFH ) tended to be shorter than that of the mother (DMH ) (5/7), the authors also calculated the proportion of the duration that a child stayed together with the father (PDFH ) or the mother (PDMH ) for the total duration that the child and the parent were both at home. In five out of seven cases, the PDFH was 1.6%–43.6% smaller than PDMH , indicating that the father tended to stay together with his child for a lesser duration than the mother (Table 1 ). On average, the duration that the child and father stayed separately (DFS ) represented 80.6% of the total time that both of them stayed at home.

| ID | Survey period [Day] | DF [Min] | DM [Min] | DP [Min] | DS [Min] | PDF [%] | PDM [%] | PDP [%] | DFH [Min] | DMH [Min] | PDH [%] | PDH [%] | DFS [Min] | PDFS [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boy 1 | 4 | 22 | 135 | 88 | 245 | 9 | 55.1 | 35.9 | 535 | 1377 | 4.1 | 9.8 | 425 | 79.4 |

| Boy 2 | 3 | 26 | 30 | 64 | 120 | 21.7 | 25 | 53.3 | 335 | 407 | 7.8 | 7.4 | 245 | 73.1 |

| Boy 3 | 4 | 120 | 155 | 352 | 627 | 19.1 | 24.7 | 56.2 | 2486 | 2416 | 4.8 | 6.4 | 2014 | 81 |

| Boy 4 | 3 | 53 | 18 | 189 | 260 | 20.4 | 6.9 | 72.7 | 972 | 959 | 5.5 | 1.9 | 730 | 75.1 |

| Girl 1 | 4 | 200 | 448 | 43 | 691 | 29 | 64.8 | 6.2 | 780 | 878 | 25.6 | 51 | 537 | 68.8 |

| Girl 2 | 2 | 9 | 111 | 6 | 126 | 7.1 | 88.1 | 4.8 | 149 | 224 | 6 | 49.6 | 134 | 89.9 |

| Girl 3 | 3 | 1 | 67 | 6 | 74 | 1.4 | 90.5 | 8.1 | 204 | 464 | 0.5 | 14.4 | 197 | 96.6 |

| Average | 3.3 | 61.6 | 137.7 | 106.9 | 306.4 | 15.4 | 50.7 | 33.9 | 780.1 | 960.7 | 7.9 | 20.1 | 611.7 | 80.6 |

DF : duration that only child and father stayed together; DM : duration that child and mother stayed together; DP : duration that child and parents stayed together; DS=DF+DM+DP; PDF =DF ×100/DS , PDM=DM× 100/DS, PDP=DP× 100/DS ; DFH : duration that child and father both stayed at home ;DMH : duration that child and mother both stayed at home; PDFH=DF× 100/DFH, PDMH=DM× 100/DMH; DFS : duration that child and father stayed separately; DFS=DFH−DF−DP, PDFS=DFS× 100/DFH .

The authors also compared the vocal duration of the father and mother by using the proportion of the vocal duration of the father (PVF ) or that of the mother (PVM ) for the total vocal duration that occurred when she/he stayed together with the child. For six out of seven cases, the father talked 11.4%–62.8% less than the mother. Averagely, the father talked about 20% less than the mother (Table 2 ).

| ID | Survey period [Day] | VF [Second] | VM [Second] | VC [Second] | VS [Second] | PVF [%] | PVM [%] | PVC [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boy 1 | 4 | 93 | 684 | 164 | 941 | 9.9 | 72.7 | 17.4 |

| Boy 2 | 3 | 900 | 672 | 429 | 2001 | 45 | 33.6 | 21.4 |

| Boy 3 | 4 | 522 | 870 | 1078 | 2470 | 21.1 | 35.2 | 43.7 |

| Boy 4 | 3 | 655 | 872 | 264 | 1791 | 36.6 | 48.7 | 14.7 |

| Girl 1 | 4 | 1292 | 2436 | 3680 | 7408 | 17.4 | 32.9 | 49.7 |

| Girl 2 | 2 | 37 | 66 | 151 | 254 | 14.6 | 26 | 59.4 |

| Girl 3 | 3 | 66 | 515 | 556 | 1137 | 5.8 | 45.3 | 48.9 |

| Average | 3.3 | 509.3 | 873.6 | 903.1 | 2286.0 | 21.5 | 42.1 | 36.5 |

VF : Fathers vocal duration in the period when he stayed together with the child; VM : Mothers vocal duration in the period when she stayed together with the child; VC : Childs vocal duration in the period when (s)he stayed together with at least one parent; VS=VF+VM+VC PVF=VF× 100/VS , PVM=VM× 100/VS, PVC=VC× 100/VS .

3.2. The distribution of the rooms that the father and child stayed in and the duration

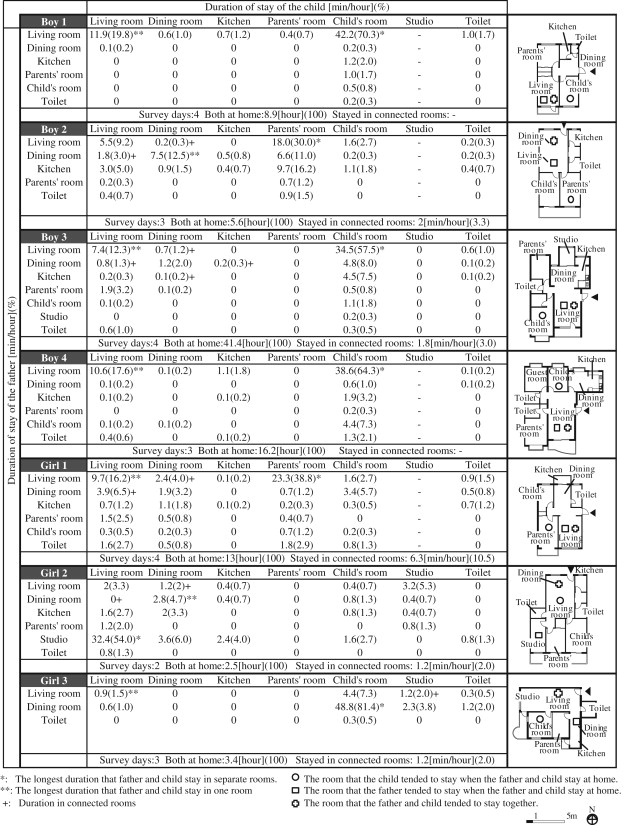

Depending on the specific activities of the father and child, they may stay in the same or different rooms during a specific period. Fig. 5 shows the rooms that they stayed in and the duration when they are both at home for the whole survey period. Whether or not the mother was present is not shown. The number at the crossing of the row and column in the table of Fig. 5 shows the duration (percentage) that the father and child stayed in the same room or given pairs of rooms at the same time. For example, for Boy 1, the figure “11.9 [min/h] (19.8[%])” at the intersection of row one and column one indicates the average minutes per hour and percentage that the father and child stayed together in the living room over the whole period that they were at home (8.9 h). Further, “42.2 [min/h] (70.3[%])” indicates the average duration and percentage that the child stayed in her/his room while the father stayed in the living room.

|

|

|

Fig. 5. Distribution of the rooms that the father and child stayed in and the duration of their stay during the period when they were both at home. |

The child and father of each subject family had a tendency to stay in a certain pair of rooms during the period they stayed in different rooms. The proportion of the longest duration that the father and child stayed in different rooms was 30.0%–81.4%. The subjects could be classified into two groups according to the room that the father stayed in:

- Father stayed in the living room (all Boys and Girl 1)

In this group, Boys 1, 3, and 4 had the same tendencies regarding room use. The child tended to stay in the childs room when the father was in the living room, which was also the room that they tended to stay in together. On the other hand, Boy 2 and Girl 1 tended to stay in the parents' room when their fathers stayed in the living room. In the interview, they answered that this was because the only PC in the house was in the parents' room and they were allowed to play PC games during summer vacation when the survey was conducted. This kind of stay, in which the father stayed in the living room and the child stayed in the childs room or parents' room, occupied 30%–70.3% of the time when the father and child both stayed at home.

- Father stayed in other rooms (Girls 2 and 3)

Compared with group (i), the children in this group spent less time with their father in the same room. Girl 2 tended to stay in the living room, but her father tended to stay in the studio. Girl 3 tended to stay in the childs room when her father stayed in the dining room, and they only met for a total of three minutes in the living room. When interviewed, the two fathers indicated that they stayed in that room not because they preferred quiet or solitude, but so they could install their PC on the table and work there. Although there was a studio in the house of Girl 3, it was occupied by the mother. This kind of stay, in which the fathers stayed in the studio or dining room to work while their children stayed in the living room or childs room, occupied over 50% of the time when the father and child both stayed at home.

The duration that the child and father stayed in connected rooms was short for all the subjects who had connected rooms in their respective dwellings (no more than 5% for Boys 2 and 3, and Girls 2 and 3), except for Girl 1 (10.5%).

For Girls 2 and 3, who did not stay together with their fathers long, this kind of stay, which was observed when the fathers stayed in the living room (Girls 2 and 3 stayed in the dining room and studio, respectively), may be meaningful. The findings indicate that the father could have had more opportunities to be with the child if he had stayed in the living room.

3.3. Duration and frequency of time spent together and speech between the child and the father

There are four ways in which a child stays together with his/her father:

- The child stays with the father in the same room.

- The child stays with both the father and mother in the same room.

- The child and father stay in connected rooms (e.g., when the child stays in the living room and the father in the dining room in the house of Boy 2), and the mother is absent.

- The child and father stay in connected rooms, and the mother stays with either of them.

The average duration (D ) and frequency (F ) of the father and child staying together per hour that they both stayed at home over the whole survey period were calculated. The authors also calculated the average duration (Dt [Min]) and frequency (Ft [times]) that either the child or the father spoke per hour of the time they both stayed at home.

When ① or ② occurred, most subjects tended to stay and talk in one room (either of D , F , Dt , or Ft was highest in this room), and they tended to talk every time they stayed there (F1 =Ft1 , F2 =Ft2 ). ② for Girl 2 was the exception: she tended to stay in the dining room longer but also stayed frequently and talked in the living room. When ① occurred, Girl 2 and her father tended to stay and talk in both the living and dining rooms.

Boys 1 and 3, and Girls 1 and 3 tended to stay together with their fathers and talk in the living room when ① or ② occurred. Boy 2 tended to stay together with his father and talk in the dining room when ① or ② occurred. Boy 4 tended to stay together with his father and talk in the childs room in ①, and they tended to stay and talk in the living room in ②.

The living room was the most-used room, followed by the dining room; it is in these rooms that the child and the father stayed together and talked most often (Table 3 ; Table 4 ).

| Living room | Dining room | Kitchen | Parents' room | Childs room | Sum | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1(F1) | Dt1(Ft1) | D1(F1) | Dt1(Ft1) | D1(F1) | Dt1(Ft1) | D1(F1) | Dt1(Ft1) | D1(F1) | Dt1(Ft1) | D1(F1) | Dt1(Ft1) | |

| Boy 1 | 2a (0.7b ) | 0.8a (0.7b ) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | – | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.5(0.3) | 0.4(0.3) | 2.5(1) | 1.2(1) |

| Boy 2 | 1.6(0.7) | 1.3(0.7) | 2.3a (0.9b ) | 2.1a (0.9b ) | 0.4(0.4) | – | 0.7(0.5) | 0.5(0.5) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 5(2.5) | 3.9(2.5) |

| Boy 3 | 2.3a (0.5b ) | 1.3a (0.5b ) | 0.2(0.1) | 0.2(0.1) | 0(0) | – | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.9(0.4) | 0.7(0.4) | 3.4(1.1) | 2.2(1.1) |

| Boy 4 | 0.2(0.2) | 0.2(0.2) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.1(0.1) | – | 0(0) | 0(0) | 3a (0.7b ) | 1.8a (0.7b ) | 3.3(1) | 2(1) |

| Girl 1 | 9.2a (2.3b ) | 9.1a (2.3b ) | 1.5(0.4) | 1.3(0.4) | 0.1(0.1) | – | 0.2(0.2) | 0.2(0.2) | 0.2(0.1) | 0.2(0.1) | 11.2(3) | 10.8(3) |

| Girl 2 | 1.2a (0.4b ) | 0.4a (0.4b ) | 1.2a (0.4b ) | 0.4a (0.4b ) | 0(0) | – | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 2.4(0.8) | 0.8(0.8) |

| Girl 3 | 0.3a (0.3b ) | 0.3a (0.3b ) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | – | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.3(0.3) | 0.3(0.3) |

D1 [min/h]: average duration that the child and father stayed in same room per hour that they stayed at home; F1 [times/h]: average frequency that the child and father stayed in same room per hour that they stayed at home; Dt1 [min/h]: average duration that the child and father stayed in same room and either of them had talked per hour that they stayed at home; Ft1 [times/h]: average frequency that the child and father stay in same room and either of them had talked per hour that they stayed at home.

a. The longest duration.

b. The highest frequency.

| Living room | Dining room | Kitchen | Parents’ room | Childs room | Sum | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D2(F2) | Dt2(Ft2) | D2(F2) | Dt2(Ft2) | D2(F2) | Dt2(Ft2) | D2(F2) | Dt2(Ft2) | D2(F2) | Dt2(Ft2) | D2(F2) | Dt2(Ft2) | |

| Boy 1 | 9.9a (0.7b ) | 5.2a (0.7b ) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | – | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 9.9(0.7) | 5.2(0.7) |

| Boy 2 | 3.9(0.2) | 3.8(0.2) | 5.2a (0.7b ) | 5.2a (0.7b ) | 0(0) | – | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 9.1(0.9) | 8.9(0.9) |

| Boy 3 | 5a (0.6b ) | 3.3a (0.6b ) | 1(0.2) | 0.8(0.2) | 0(0) | - | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.2(0) | 0.2(0) | 6.3(0.9) | 4.3(0.9) |

| Boy 4 | 10.3a (1b ) | 7.9a (1b ) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | – | 0(0) | 0(0) | 1.4(0.1) | 1.2(0.1) | 11.7(1.2) | 9.1(1.2) |

| Girl 1 | 0.5a (0.3b ) | 0.5a (0.3b ) | 0.4(0.1) | 0.4(0.1) | 0(0) | - | 0.2(0.1) | 0.2(0.1) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 1.1(0.5) | 1.1(0.5) |

| Girl 2 | 0.8(0.8b ) | 0.4a (0.4b ) | 1.6a (0.4) | 0(0) | 0(0) | – | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 2.4(1.2) | 0.4(0.4) |

| Girl 3 | 0.6a (0.3b ) | 0.6a (0.3b ) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | – | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.6(0.3) | 0.6(0.3) |

D2 [min/h]: average duration that the child and parents stayed in same room per hour that they stayed at home; F2 [times/h]: average frequency that the child and parents stayed in same room per hour that they stayed at home; Dt2 [min/h]: average duration that the child and parents stayed in same room and either child or father had talked per hour that they stayed at home; Ft2 [times/hour]: average frequency that the child and parents stayed in same room and and either child or father had talked per hour that they stayed at home.

a. The longest duration.

b. The highest frequency.

When staying together in connected rooms (③ and ④), the subjects tended to stay and talk in the living and dining rooms that were connected to each other. The subjects talked almost every time they stayed in connected rooms, with the exception of Boy 3, whose duration and frequency of speech were less than those in the period during which they stayed in connected rooms (Table 5 ; Table 6 ).

| Living room and dining room | Dining room and kitchen | Living room and studio | Sum | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D3(F3) | Dt3(Ft3) | D3(F3) | Dt3(Ft3) | D3(F3) | Dt3(Ft3) | D3(F3) | Dt3(Ft3) | |

| Boy 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Boy 2 | 0.6(0.2) | 0.6(0.2) | – | – | – | – | 0.6(0.2) | 0.6(0.2) |

| Boy 3 | 0.1(0.1) | 0.1(0.1) | 0.1(0.1) | – | – | – | 0.2(0.2) | 0.1(0.1) |

| Boy 4 | – | – | 0 | – | – | – | 0 | – |

| Girl 1 | 4.8(2.2) | 4.7(2.2) | – | – | – | – | 4.8(2.2) | 4.7(2.2) |

| Girl 2 | 1.2(0.4) | 1.2(0.4) | – | – | – | – | 1.2(0.4) | 1.2(0.4) |

| Girl 3 | – | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

D3 [min/h]: average duration that the child and father stayed in connected rooms per hour that they stayed at home; F3 [times/h]: average frequency that the child and father stayed in connected rooms per hour that they stayed at home; Dt3 [min/h]: average duration that the child and father stayed in connected rooms and at least one of them had talked per hour that they stayed at home; Ft3 [times/h]: average frequency that the child and father stayed in connected rooms and at least one of them had talked per hour that they stayed at home—there was no such space in the subject house.

| Living room and dining room | Dining room and kitchen | Living room and studio | Sum | |||||

| D4(F4) | Dt4(Ft4) | D4(F4) | Dt4(Ft4) | D4(F4) | Dt4(Ft4) | D4(F4) | Dt4(Ft4) | |

| Boy 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Boy 2 | 1.4(0.9) | 1.4(0.9) | – | – | – | – | 1.4(0.9) | 1.4(0.9) |

| Boy 3 | 1.4(0.6) | 1(0.5) | 0.2(0.1) | – | – | – | 1.6(0.7) | 1 (0.5) |

| Boy 4 | – | – | 0 | – | – | – | 0 | – |

| Girl 1 | 1.5(0.5) | 1.5(0.5) | – | – | – | – | 1.5(0.5) | 1.5(0.5) |

| Girl 2 | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | – | 0 | 0 |

| Girl 3 | – | – | 0 | 0 | 1.2(0.9) | 1.2(0.9) | 1.2(0.9) | 1.2(0.9) |

D4 [min/h]: average duration that the child and father stayed in connected rooms per hour that they stayed at home(mother stayed in either room); F4 [times/h]: average frequency that the child and father stayed in connected rooms per hour that they stayed at home(mother stayed in either room); Dt4 [min/h]: average duration that the child and father stayed in connected rooms and at least one of them had talked per hour that they stayed at home(mother stayed in either room); Ft4 [times/h]: average frequency that the child and father stayed in connected rooms and at least one of them had talked per hour that they stayed at home(mother stayed in either—there was no such space in the subject house.

The authors compared the summation of duration and frequency of time spent together and speech in ① and ③, which focus on time spent between the child and father, with ② and ④, which focus on the time that both the child and father spent in the presence of the mother. For the boys, the duration and frequency of staying and talking in ③ and ④ tended to be less than that in ① and ②, respectively, and the duration of staying and talking in ③ and ④ were less than 1/4 of that in ① and ②. Boy 2 in ④ was an exception, and the frequency of his stays and talks was equal to that in ②. For the girls who spent time in ③ and ④, the duration and frequency of stays and talks for Girl 1 in ③ was less than that in ①. The duration of stays and talks of the two girls in ④ was more than that when ② occurred (Table 3 , Table 4 , Table 5 ; Table 6 ).

3.4. Comparison of vocal duration when child and father stayed together

To determine who was more vocal when the father and child stayed together, the authors compared their vocal durations. Since the child stayed with both parents, the possibility that vocal duration will include speech with the mother exists, so the authors compared the vocal duration only for the periods when the child stayed together with the father.

A child staying with his/her father in a certain room and either of them talking was regarded as one case. In over half of the cases when the child stayed with the father in common rooms (living room, dining room, or the space where the living room connected with the dining room), the child spoke over 1.6 times more than the father. However, in the individual rooms (parents' or childs room), especially in the childs room, the child always spoke less than the father, and the duration of the childs speech was less than 70% of that of the father (Table 7 ).

| ID | Common room | Individual room | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stay in the same room | Stay in connected rooms | Stay in the same room | |||||||||||||

| Living room | Dining room | Living room and dining room | Parents' room | Childs room | |||||||||||

| Vc | Vf | Vc/Vf | Vc | Vf | Vc/Vf | Vc | Vf | Vc/Vf | Vc | Vf | Vc/Vf | Vc | Vf | Vc/Vf | |

| Boy 1 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 0.4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.7 |

| Boy 2 | 6.3 | 7 | 0.9 | 11.3 | 35 | 0.3 | 7.1 | 3.8 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 3.2 | 0.2 | - | - | - |

| Boy 3 | 4.2 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 4 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | - | - | - | 1.3 | 3.6 | 0.4 |

| Boy 4 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 1.6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.7 | 4 | 0.7 |

| Girl 1 | 41 | 58.6 | 0.7 | 6.5 | 8 | 0.8 | 34.1 | 14.1 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Girl 2 | 7.6 | 13.2 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0 | ∞ | 5.2 | 0 | ∞ | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Girl 3 | 6.8 | 1.2 | 5.7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Vf<Vc | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Vf>Vc | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||||||||||

Vc [s/h]: Childs average vocal duration per hour when both the father and child stayed at home; Vf [s/h]: Fathers average vocal duration per hour when both the father and child stayed at home—the child did not stay together with the father in this room/space.

4. Conclusion

In this paper, the authors identified which rooms the father and child tended to stay in together and talk, and which rooms they stayed in separately using Active RFID devices and an audio recorder. The reasons they stayed there were obtained by conducting short interviews. The findings are as follows:

- The father tended to stay in the same room or connected rooms with the child for less time than the mother. On average, when with the child, the duration of fathers speech is about 20% shorter than the mother.

- The instances in which child and father stayed in different rooms fall into two groups: (i) five of the seven subject fathers tended to stay in the living room, whereas the children stayed in the childs room or in the parents' room to use the PC; (ii) two fathers stayed in the studio or dining room to work, while their children stayed in the living room or the childs room. For both groups, the duration of these periods of stay covered 30.0%–81.4% of the time when both the father and child stayed at home.

- The father stayed together with the child for 0.5%–25% of the time when both the father and child were at home. The use of the living room as the place, in which the child stay with the father and either of them had talked, was found to be the highest (five out of seven families), followed by the dining room and the childs room. They also stayed and talked in living and dining rooms that were connected to each other. For the boys, the duration of this kind of time spent together tended to be less than 1/4 of that if they stayed with the father in the same room.

- In over half of the cases in which the child stayed with the father in the living room or dining room, the child spoke over 1.6 times more than the father. However, in all cases in individual rooms, particularly the childs room, the child always spoke less than the father, and the duration of the childs speech was less than 70% of that of the father.

Based on the detailed room use analyzed above, the following points are important for room layout planning for only-child families: the child is likely to speak more than his father in common rooms, which can therefore be considered as places where equal levels of conversation may occur and are better places for communication than individual rooms. Thus, to improve father–child communication, it is important to increase their time spent together in the common rooms, particularly in the living room.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the cooperation of the seven subject families and the valuable help of Zhang Xinnan, Xu Weimin, Zhang Ying, Qu Xiansheng, Xu Dong, and Xu Qun. We also appreciate the efforts of Sun Miqin, who designed the software that was used to identify vocal duration. This work is supported by KAKENHI (no. 19686036 ).

References

- Central Council for Education Central Council for Education, 1998. For educating the next generation, who are facing a new world. p. 6

- Chen, 2006 S.M. Chen; Investigation on mental influence of parent–child communication on middle school students; Journal of Shanghai Normal University, Elementary Education Edition, 12 (2006), pp. 125–128

- Enta et al., 2008 A. Enta, K. Hayashida, H. Watanabe; Tracing of human walk by using slipper-type RFID Reader; Journal of Architecture and Planning, AIJ, 630 (2008), pp. 1847–1852

- Enta et al., 2009 A. Enta, Y. Otsuka, H. Watanabe; Monitoring of contact behavior by using Ring-Tpe RFID reader; Journal of Architecture and Planning, AIJ, 646 (2009), pp. 2739–2744

- Feng, 2002 X.T. Feng; Relationship between urban middle school students and their parents-image from different view point; Youth Studies, 8 (2002), pp. 36–40

- Fujino and Kitaura, 2006 J. Fujino, K. Kitaura; A study on the family room from the view point of parent-child communication: an analysis of the childs development in the case of school child and high school student; Journal of Architecture and Planning, AIJ, 602 (2006), pp. 1–6

- Kitaoka and Machida, 2001 Y. Kitaoka, R. Machida; The space of family-communication in a house: in a case of Keihoku-cho in Kyoto: a house-plannning study for establishing the individual in the family (3). The scientific reports of Kyoto Prefectural University; Human Environment and Agriculture, 53 (2001), pp. 27–34

- Liu et al., 2005 N. Liu, X.K. Chen, Z.Y. Wen; Analysis on parent–child communication situation and its influential factors in nuclear families in Shanghai; Chinese Journal of Public Health, 21 (2) (2005), pp. 167–169

- Mehrabian, 1967 A. Mehrabian; Inference of attitude from nonverbal communication in two channels; The Journal of Counseling Psychology, 31 (1967), pp. 248–252

- Ohta and Yanase, 1990 S. Ohta, T. Yanase; A study on the living space planning relating to the form of kitchen (Part 1), the relation between the form of kitchen and the housewives' participation in the family-communication; Journal of Home Economics of Japan, 41 (9) (1990), pp. 875–886

- Sawachi and Matsuo, 1989 T. Sawachi, Y. Matsuo; Daily cycles of activities in dwellings in the case of husbands and children: study on residents' behavior contributing to formation of indoor climate, Part 3; Journal of Architecture and Planning and Evironment Engineering, Transactions of AIJ, 404 (1989), pp. 23–36

- Taniguchi and Ohgaki, 2002 N. Taniguchi, N. Ohgaki; Study on communication in the family of detached houses in Sapporo area; Summaries of Technical Papers of Annual Meeting, AIJ, F-1 (2002), pp. 1231–1232

- Tomoda et al., 1991 H. Tomoda, T. Kaneko, R. Takashima, Y. Tamazaki; A phenomenological analysis of “house-space”: Part 18 Evaluation of environmental psychology about the L-Hall type. Summaries of technical papers of annual meeting architectural institute of Japan; Architectural planning and design rural planning, 8 (1991), pp. 73–74

- Qu and Matsushita, 2010 X.Y. Qu, D. Matsushita; Observation on room-staying behavior by using active RFID; Journal of Architecture and Planning, AIJ, 650 (2010), pp. 1847–1852

Notes

1. According to World Health Organizations definition, adolescents are those between the ages of 10–19 years.

2. Tangshan is an industrial city in Hebei Province, located southeast of Beijing. Its area is 13,472 km2 and its population is 7.35 million (as of June 2009).

3. Since previous research (Refs. in Chapter 1) has indicated that the problem of fathers communicating with their children less frequently than mothers occurs among adolescents in general rather than among adolescents of a certain age, the authors did not limit the subjects to senior or middle school students. Additionally, in our opinion, since our purpose is not a comparison between senior and middle school students but rather a clarification of the characteristics of individual cases, it does not matter if the authors used subject girls aged 13, 17, or 19 years. According to the results, while the subject girl aged 13 (Girl 1) stayed with her father longer and more frequently than the older subjects, she faced the same problem as the other subjects in that she stayed with the father for a lesser duration than the mother. This indicates that this does not conflict with our purpose.

4. Depending on the specific location of the resident, the reader in the adjacent room might receive signals sporadically, which the authors regarded as noise. In order to reduce noise, RFID data were filtered every minute. The signals received by each reader in a minute were counted, and the room in which the reader received the most signals in a minute was specified as the residents “staying room” in that minute (Fig. 4 ).

5. The software that can identify vocal duration was designed by Sun Miqin.

Document information

Published on 12/05/17

Submitted on 12/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?