Abstract:

The Robotic process automation (RPA) is software pre-configured to execute defined business rules in the context of a stand-alone application software. This type of technology is important and practical for the auditing profession because auditing has clear and systematic rules and also a major part of its operation is done through the business systems of the owners. A part of the audit process that has a specific workflow and repeatable judgments is a good option for performing an automated robotic process. The purpose of this study is to develop a framework for applying the automated robotic process in auditing. The use of such male software in auditing reduces costs, increases operational efficiency and more advanced analysis. However, the automated robotic process has challenges in deployment, such as: reduction of manpower, items that need multiple attention, privacy, security and so on. In a general analysis, it can be said that due to the continuous development of technology, auditing firms should move towards automation of their processes and if they do not use technology properly, they will lose their competitive advantage.

Key words: Robotic process automation, Audit Analysis, Audit Future, Information Technology, Emerging Technologies.

Reference to this paper should be made as follows: Minaiee, A., ‘A Review on Using Robotic Automation in Accounting Firms’, Eur. Account. Rev, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp.1410–1433.

Biographical notes: Amirhossein Minaiee is a research fellow in accounting at Islamic Azad University, West Tehran Branch, Tehran. He has worked at many companies as a researcher and sales manager and has much experience in business and data mining. Also, he took many courses in accounting and business. His main area of research is robotic accounting and business management.

1. Introduction

Firms are rapidly using software robots to perform routine business works by mimicking the routes that people interact with software applications. And the increasing growing market for robot process automation (RPA) is now displaying signs of an important emerging trend: Enterprises are starting to perform RPA along with cognitive technologies like speech recognition, natural language processing, and machine learning to automate perceptual and judgment-based functions once reserved for people (Corrado et al, 2018).

Industrialization has automated tasks with the aim of creating economic efficiency and improving product quality. The line of production invented by Henry Ford is generally a process that transformed manual production activities into repetitive and sequential activities through the study of time and motion. Process automation developed with the growth of sophisticated industrial machinery and tools and by imitating repetitive human work (Accenture, 2016). The issue of automation has not received much support in the auditing profession, and the tendency to do things traditionally and manually still remains a priority. Meanwhile, large auditing firms have begun to revise their processes to automate. They try to combine advanced automation technologies with their traditional analysis. This review process is integrated with the consulting services department that exists in these institutions (Early, 2015).

On the other hand, in the field of automated robotic process, studies on audit automation have generally been done and little research has been done on the method of automatic intelligentization of duplicate audit processes (IEEECAG, 2017). The way businesses and data sources are conducted has changed significantly from the past, but the audit framework and procedures have changed slightly. This has reduced the value and quality of auditing for companies (Issa et al, 2016).

Robotic Process Automation (RPA) is the employing of robots (standalone computer programs) to automate repetitive and common business processes. The use of robots in the accounting profession and in business in general is growing rapidly (Frey et al, 2013).

RPA’s potential advantages are manifold. They can include reducing costs (by cutting staff), lowering error rates, improving service, reducing turnaround time, increasing the scalability of operations, and improving compliance. For instance, a large consumer and commercial bank redesigned its claims process and deployed 85 software robots, or bots, running 13 processes, handling 1.5 million requests per year (Appelbaum et al, 2017). As a result, the bank was able to add capacity equivalent to around 230 full-time employees at approximately 30 percent of the cost of recruiting more staff (Peterson & George, 2017).

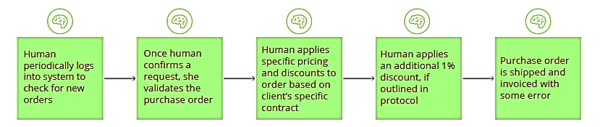

Beyond automating existing processes, companies use robots to implement new processes that would otherwise be impractical. For example, the UK retail group Shop Direct used RPA to identify flood-affected customers and automatically remove late payment fees from their accounts. Financial service providers also used such "one-time" RPA implementations to comply with legal requirements in areas such as Correction processing, monitoring, and reporting (Cooper et al, 2018). A typical back-office process before and after implementing RPA is shown in Figure 1.

(a)

Auditing can be divided into four main categories based on the use of data mining technology: a) risk assessment, b) evaluation of internal controls, c) basic analytical methods, d (other analytical methods, according to the overlap of capacities and Audit data mining functions in the four categories of auditing mentioned, the emergence of information technology, the possibility of automation, decision making using technology and the availability of big data, revision of audit processes and approaches are necessary for this purpose. The main category categorized (Lacity et al, 2015):

1) Parts of auditing that are prone to using regular workflows and time and movement studies.

2) Parts of the audit that have repeatable judgments and are generally considered definitive if there is specific information and evidence.

Judgments that are random in nature, such that auditors often do not formulate them in a similar way or disagree on similar results.

The first two categories are useful for automation and automation processes.

2- Advantages of Robotic process automation (RPA)

RPA focuses employees on goals and activities that require human judgment by doing daily, repetitive and structured work. In addition, RPA has other benefits that we divide into four groups (Lacity, 2016).

2.1. Reduction in costs

In according to research, PRA can save 25% to 50% on costs. PRA can also be used as 7 × 24. PRA can work without errors and is relatively inexpensive compared to work and human capacity. The cost of a software robot is one-third the price of a full-time employee outside the firm and one-fifth the price of a full-time employee inside the firm (PCAOB, 2017).

2.2. More efficiency

PRA provides a better service model by increasing speed and accuracy, as well as reducing activity cycle time and reducing the need for ongoing training. For example, according to experimental results at an auditing firm, an employee spends an average of 12 minutes doing insurance calculations, while a male software robot does it in one-third of that time (Alles et al, 2006).

2.3. More advanced analysis

PRA makes it easier to collect and organize data, so a company can better predict future events and improve its processes accordingly. Using advanced analytical techniques, it will be possible to create more feedback cycles. More advanced analysis improves processes, which in turn leads to better data generation and further improved processes and higher levels of efficiency (Li, 2017)

2.4. Improve performance and quality

There is always the possibility of error in human affairs. The risk of defects, shortcomings and fraud in manual systems is always higher than in automated systems. Robots are reliable, adaptable and tireless. They can do the same thing at any time and place without making mistakes or cheating (Moffitt et al, 2018).

3. Framework for implementing automated robotic process in accounting

There are four steps to using PRA in accounting: 1) selection of procedures, 2) modification of procedures, 3) application of PRA, and 4) evaluation and feedback (Kokina &Davenport ,2017).

3.1. Selection of procedures

At this stage, the audit firm evaluates the audit processes to determine where automation will add value. Accounting and auditing firms for planning to apply PRA, should first review the structure of their audit procedures and identify appropriate ones based on a number of components. Some of these components are listed below:

3.1.1. Criteria for RPA

The audit procedure should have three criteria for selecting the appropriate procedures of RPA performance mentioned above: First, well-defined processes are more automated. Second, large, repetitive tasks can benefit more automation. Third, complete tasks must be targeted. They have more predictable results and costs are clear (Keenoy, 1958).

3.1.2. Data compatibility

After reviewing the RPA criteria, the audit team should consider the second most important component of the RPA -based audit: Is there adequate data to establish a robotic automation process? The data must be in digital format or the data can be converted to digital format (Hindle et al, 2018). Even if the RPA software is able to extract and interpret unstructured textual information (such as images), structured data is preferred because of its greater accuracy and lower processing costs (McClimans, 2018). Evaluate the data and make sure that the data is structured and digitally available.

3.1.3. Complexity of procedures

Another component to deciding whether to use PRA in a particular audit procedure is complexity. Auditing firms should be aware that even if meta-implementation is relatively easy, the implementation process is time consuming and risky, and many implementations actually fail (Chappell, 2018). To reduce implementation risk, the audit firm should evaluate the complexity of the audit procedures and the usability of the PRA in a simple procedure through a pilot project. After becoming more familiar with the pilot project, auditors can use the PRA in more complex procedures.

3.2. Modification of procedures

After selecting appropriate procedures, auditors should consider modifying existing procedures to implement meta-based auditing. As a result, the auditing firm should review current procedures and, if necessary, modify the audit program to ensure that they are compatible with the PRA software. The auditing firm should also assess in its assessments whether the data used in the process is structured in digital form or capable of being digitized or not. Therefore, this stage can be divided into two more detailed stages (Kotarba, 2018).

3.2.1. Procedures modulation

After selecting the audit procedures, the PRA team should divide the audit procedures in these procedures into smaller categories. In order to software programs to function as planned, they need precise instructions. For example, one can understand and execute the "Open Email Account" command without specific instructions, but a software program requires a number of pre-programmed conditions to execute the same command. In this case, the software needs commands that are not related to opening the Internet browser, entering user information to log in and check email (Di, 2014).

The audit should define a set of activities for each procedure and a set of consecutive instructions for each activity, so that software programs can execute these instructions. The process that turns a procedure into several sets of consecutive commands is called modulation.

3.2.2. Data standardization

Data sources and labels must be considered to implement PRA-based audits. In addition, audits are generally based on the evaluation of financial and non-financial data supported by financial statements. The data must be structured and digital in order the PRA software can successfully interpret the audit procedures. The fact is that the data collected as audit evidence, even on a single subject, are collected from different sources and under different headings. For example, Report A may be titled "Sales", while Report B may be has the title "income". Such inconsistencies in the titles create interpretive challenges for the software program (Kaya et al, 2019). Therefore, Data standardization is essential to address this issue. Data standardization can be a template that uses appropriate titles for similar data. For example, the Audit Data Standard (ADS), the executive committee of the American Association of Certified Public Accountants, agrees with this view and outlines the benefits of data standardization. It also publishes copies of data standardization.

3.3. Application of automated robotic process

For implementation, auditing firms can purchase PRA software from providers such as UiPath and Blue Prism, or design and program PRA software within the organization. For the following reasons, it is suggested that software design and programming be done within institutions [24].

First, most PRA software comes with a user-friendly interface and are very simple to code. According to a recent interview with PRA team managers at four major auditing firms, it was stated that auditors can code the PRA program on their own, and that programmers are only required for complex programming.

Second, to successfully implement plans and reduce the risk of execution, auditors' understanding of the details of each client's procedures is essential.

Third, the audit firm has more control over the software by designing and coding within the organization, as well as better information security and confidentiality.

4. The application of RPA in accounting

Nowadays, accounting is among the most probably ones to be taken by software robots (Peccarelli, 2016). Recording accounting actions needs great accuracy, stability, and many of them involve the handy handling of repetitive implementation. An employee often gathers data from multiple systems and next processes the information (checks, submits for acceptance) before eventually saving them into an accounting system. Manual data collection and manipulation uses much time. Time can be saved, and the error ratio decreased when robots action over these tasks (Tucker, 2017). Accounting actions use prescribed rules and methods, which causes them relatively simple to automate. Meanwhile, automation supplies tracking checks, approvals and document management. Audit records of automated actions can include more detail levels than when performed by manual handling. Accounting rules and standards are subject to continuing evolutions (e.g. tax rule). Robots can be rapidly retrained (in a centralised way) to convince with the updated rule (Willcocks et al., 2017). Also, legacy systems can be devoid of solutions allowing traditional automation is another reason to consider RPA (Drum, Pulvermacher, 2016). Then, accounting processes are appropriate candidates for being taken over by software robots due to the concurrent use of modern and legacy software and the repeated of manual functions.

Many accounting actions have been outsourced to shared service centers. The important motivation for moving operations outside the firm is to decrease costs by operating them in regions with lower wages. However, it seems that the benefits of outsourcing are already understood by most companies. The labor cost benefit is reducing and is no longer the main reason for outsourcing. Traditional outsourcing needs more oversight than controlling processes outsourced to robots. Another reason for changing transaction processing to automation can be to maintain more control over data. Employees appear to be more open to the opinion of RPA than traditional outsourcing (Robotic Process Automation, 2019).

A 2018 survey of more than 500 managers found that outsourcing is now more about disruptive technologies (artificial intelligence, RPA, cloud computing) than labor arbitrage (Reshaping the future, 2018). Task automation is now the next alternative to enhance productivity and obtain a competitive benefit. But, the shared services business sector is considerably employing RPA, so it does not necessarily translate into bringing jobs back from offshore (Robotic process automation, 2015).

The accounting processes that can benefit from automation in terms of performance and accuracy consist of (Borthick & Pennington, 2017):

• Period-end closing – general ledger, subledgers closing, validation of journal entries, low-risk accounts reconciliation, consolidation;

- Reporting – monthly, quarterly close, internal performance and management reporting (aggregating and analyzing financial and operational data), external statutory and regulatory reporting;

• Accounts receivable and accounts payable – maintaining (updating, vetting) customer/supplier data, creating/processing/delivering invoices, automating approvals, validating and posting payments, collections, billing, matching invoices against sales and purchase orders;

• Cash management, general ledger accounting, intercompany transactions, inventory accounting, travel and expenses – reimbursement requests, audit and document expense reports, payroll, fixed asset accounting, tax accounting.

The processes most sometimes selected for RPA include purchase-to-pay, record-to-report and internal performance reporting, due to they are routine-based and do not need judgement or complicated decision-making. Some predict that up to 40% of current transactional accounting could be taken over by automata [34]. Robots are expected to replace humans in manual bookkeeping and help them in complex, multifaceted actions (like the financial close) (Tschakert et al, 2016).

Some cases from different industries of the robotic automation of accounting processes is shown in table 1. They connect mostly with transactional accounting (invoice processing, payments), in which the automation outcomes proved to be exclusively remarkable. Processing times were substantially decreased (some by 90%) and accuracy increase. Then, employees could be transferred to other works, or there was no requirement to hire a temporary workers. Moreover, the relatively short implementation times are valuable.

| cases |

|

|

Implementation period

| ||||

|

|

|

3 weeks

| ||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

| ||||

| Quad/Graphics,

USA, Printing |

|

|

| ||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

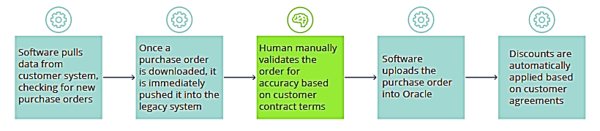

An automation example of an accounts payable process flow is shown in figure 2.

Software bots enter with their credentials, find new invoices, match them to orders, request and wait for approval, doing accounting and other data entry into internal systems, and eventually release the payment along with sending a remittance advice.

This process is repeated as long as there are pending invoices. Previously manual operations are automated and require little human intervention. Extracting, validating and entering transaction data from and into multiple systems is faster and more accurate than manual actions. An accountant can control several bots and intervenes only in exceptional cases. For example, these are related to data that does not conform to an accepted format, network problems, or malfunctions of other systems. The resource example explains the reduction in processing time and the reduction in the number of staff required.

There are various reasons to consider automating the end-of-period closing and reporting processes. Current regulatory reporting requirements (particularly for public companies) are an increasing part of the work of the modern accounting department. Closing the books, consolidating group outcomes and publishing reports in tight timeframes requires proper coordination and therefore not only demonstrates a competent finance team but also a company with good corporate governance.

The period-end closing process has a direct effect on the outcome of the report, as the usefulness of the report is derived from the accuracy, completeness, and timeliness of the data. 97% of CFOs surveyed admitted to being somewhat uncertain about the elements and outcomes of the reporting process. These principally include uncertainty about updating disclosures with the latest alters in accounts, the accuracy and integrity of information, and the inability to constantly monitor the process (Axson, 2015).

In large companies, month-end activities involve coordinating the collection and verification of large amounts of information from multiple entities, which can resulted to additional delays or risk. Much of this work is still perform manually and almost involves the use of "shadow systems", i.e. desktop files of individual employees that are not part of organizational systems. 69% of senior finance professionals admit to relying on spreadsheets for financial reporting (Future of Financial, 2017). A third of respondents reported having difficulty merging, linking or updating data from several sources that need manual information transfer, and 60% believed they spent too much time cleaning data. More than half of respondents admitted that when preparing financial reports, every time a change occurs, a lot of manual review is required afterward.

The progress of the closing and reporting processes is usually measured by checklists that include tasks and their completion and approval status. However, the reliability of the lists depends entirely on the human factor. The need to use multiple information sources and programs (including legacy sources), the repeatability of work, and the priority of accuracy, consistency, and timeliness of end-of-course and reporting processes make them good candidates for automation. Implementing RPA should decrease error rates and solve problems related to disparate documents and data integrity. Embedding robotic automation of period-end tasks into daily activities facilitates a continuous accounting approach, which distributes the workload evenly throughout the month. Companies are still exploring and understanding the benefits of RPA and other automation technologies. A global survey of more than 700 business leaders found that process automation has not yet reached maturity. Only a small number of responding companies adopted the use of automation in multiple use cases at scale. Most of them are in the experimental stage or have only automated a small part of their processes and functions. However, the rate of adoption is growing rapidly, with 72 percent of organizations surveyed either considering or in the process of implementing RPA (Traditional Outsourcing, 2018). The RPA market is expected to grow to approximately $2.7 million by 2023, a CAGR of 29% (Robotic Process Automation, 2019). More than 60 percent of companies across different industry sectors that have already implemented RPA chose rules-based automation, which is now a dominant solution. Intelligent cognitive automation is still in the early stages of development and adoption, with only 18 percent of surveyed organizations implementing it (Reshaping the future, 2018). However, rules-based automation is probably to be only an intermediate stage after macros and scripts and before artificial intelligence (AI) brings the advantage of optimizing processes thanks to its self-learning capabilities.

5. Cognitive technologies enhancing access to RPA

Robots can only perform their tasks using clear rules. This means that processes that require human judgments and complex scenarios cannot be performed automatically through the RPA. One of the RPA vendors reports that even his best customers automate up to 50 behind-the-scenes processes using robots, and most of his customers automate fewer processes. For this reason, some of these companies consider the RPA to be part of an "integrated" workforce in which robots work alongside employees and perform relatively simple tasks so that employees can focus on complex exceptions. But the gap between what humans and computers can do is changing.

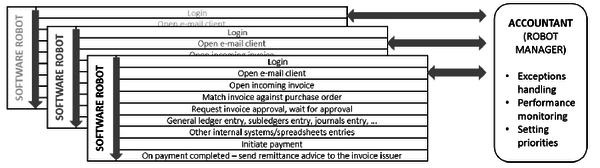

The integration of cognitive technologies with the RPA will make it possible to use automation in processes that require understanding or judgment. For example, by adding natural language processing, chat-bot technology, speech recognition, and image processing technology, robots are able to extract information and structure it into speech, text, or image sounds for later processing. Thus, machine learning can identify patterns and make predictions about process outcomes and help the RPA prioritize actions.

Cognitive RPA has far greater capabilities than basic automation and can deliver business results such as greater customer satisfaction, less error, and increased revenue. Figure 3 indicates that RPA and cognitive tools may be effective in automating the process shown in Figure 1.

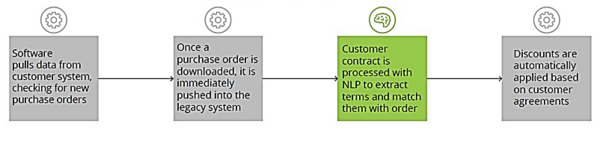

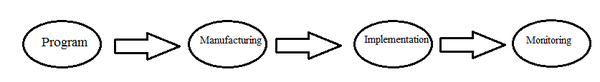

6. New risks arising from the use of intelligent automation technology in the organization

Organizations that use intelligent automation, like many similar organizations, have to answer questions about risk and leadership that begin with the ownership issue. The whole business unit, IT departments, organizational excellence centers and their sellers all contributes to intelligent automation. As a result, it is necessary to have programs to establish optimal monitoring, given key performance indicators (Kpis), key risk indicators (Kris), and processes for reducing or accepting new risks. The above monitoring forms a framework in which bots can be used in all computer programs, which are the heart of intelligent automation, so that strategies and programs, while protecting Support the stability and security of smart automation. The life cycle of intelligent automation is shown in figure 4.

Most organizations know how to evaluate their employees' skills in gaining confidence in their performance. But do they know how to use robotics skills in intelligent automation, especially those that use artificial intelligence and more complex tasks?

It is necessary to establish the necessary controls for the validation of these robots, to ensure the preservation, integrity, accuracy and correctness of the data. It is necessary to review the effectiveness of these controls and to apply them continuously throughout the life cycle of the intelligent automation program as shown in Figure 1. Moreover, common problems related to the considerations of the management system, risk management and control of these programs will arise along with the implementation of intelligent automation programs in organizations. Recognizing these potential problems and being aware of the cause and significance, they help the organization to design a plan to reduce or even prevent such problems in the direction of intelligent automation programs. In this case, there are several problems such as robot Automation, Risk and Strategy, Change Management and robot program and monitoring.

7. The future of automation robotics

RPA can potentially make significant improvements in audit performance, however, it currently has the fundamental limitation that software can perform only repetitive tasks and make limited decisions based on a set of clear and explicit rules. Therefore, current RPA software is not compatible with audit procedures that require professional judgment and cannot be translated into structured guidelines.

Recently, due to the advances in the use of artificial intelligence in industry, large auditing firms have carried out several projects to use this technology in accounting and auditing (Howieson, 2003). For example, the KPMG Accounting and Auditing Institute is partnering with IBM to use cognitive computing technology in its professional services. Moreover, experts have proposed an intelligent automation process to take advantage of the advances in artificial intelligence and overcome the limitations of current RPA software, which combines artificial intelligence, cognitive automation, deep learning and machine learning with RPA (The Future of Jobs, 2018).

IPA can use artificial intelligence capabilities to teach people how to make decisions, instead of mimicking how day-to-day business processes are done, resulting complex tasks faster and better. Accounting and auditing firms should consider using IPA to assist auditors in performing complex and unstructured audit procedures and making professional judgments.

8. Conclusion

In this article, using Robotic process automation or RPA is reviewed. The most obvious advantage of using RPA in auditing is the reduction of time spent on highly iterative processes. Using robots instead of humans creates more value for auditors. Other benefits of using RPA include greater reliability, impeccable auditing procedures, improved service quality, and improved security.

Assuming complete training, robots' ability to perform auditing tasks without error, leading to higher quality data, improved reporting, and less error correction functions. In addition, the use of robots can leave a reliable record of what has been done. Auditing by a robot is theoretically simpler than auditing by a human, due to a robot must operate within a specified script. Also, processes with RPA can lead to superior services.

Customer and supplier satisfaction increases simply by reducing the time between invoice and payment, requesting and approving a loan, or ordering and performing. Security is improved by reducing human interaction with sensitive systems. In a recent survey conducted by Capital Knowledge Group and commissioned by Blue Prism, three users were surveyed. Respondents claimed that RPA led to higher service quality, exceptional return on investment, increased process automation, improved compliance, greater organizational agility, and improved overall business value.

In addition to the benefits of using RPA, PRA implementation involves inherent risks. According to Capital Knowledge Group, about 30 to 50 percent of RPA projects fail. They also identified eight controllable areas of risk related to strategy, resources, tool selection, project time estimation, operations and execution, change management, maturity, and stakeholder engagement.

There is a potential risk of conflict with the IT department of the organization due to the involvement of stakeholders. RPA can also be implemented by non-technical users, but the IT department may consider these implementations as shadow IT projects, in short, the best thing to do to implement RPA is to coordinate with the IT department. This organizational problem must be solved in the first stages of planning by involving the stakeholders.

Another concern is that software robots are replacing human occupations. In fact, a key performance indicator of RPA is the number of human work hours stored each month, or the equivalent of the number of full-time employees currently employed by robots.

References

Corrado, C., Haskel, J., Jona-Lasinio, C. and Iommi, M. (2018), “Intangible investment in the EU and US before and since the great recession and its contribution to productivity growth”, Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, Vol. 2 No. 1,

Accenture. (2016). Getting robots right. How to Avoid the Six Most Damaging Mistakes in Scaling Up Robotic Process Automation. In. https://www.accenture.com/t00010101T000000__w__/au-en/_acnmedia/PDF-37/Accenture-Robotic-Process-Auto-POV-Final.pdf.

Earley, C. E. (2015). Data analytics in auditing: Opportunities and challenges. Business Horizons, 58(5), 493-500 .

IEEECAG. (2017). IEEE Guide for Terms and Concepts in Intelligent Process Automation. In. New York: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Corporate Advisory Group.

Issa, H., Sun, T., & Vasarhelyi, M. A. (2016). Research ideas for artificial intelligence in auditing: The formalization of audit and workforce supplementation. Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting, 13(2), 1-20 .

Frey, C. B., & Osborne, M. A. (2013). The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Technological forecasting and social change, 114, 254-280 .

Appelbaum, D., Kogan, A., & Vasarhelyi, M. A. (2017). Big Data and analytics in the modern audit engagement: Research needs. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 36(4), 1-27 .

Peterson, B. L., & George, R. P (2017). How Robotic Process Automation and Artificial Intelligence Will Change Outsourcing. Brussels. https://www.mayerbrown.com/en/perspectives-events/events/2017/09/how-rpa-and-ai-will-change-outsourcing

IRPAAI. (2017 b). Definition and Benefits. [https//:irpaai.com/definition-and-benefits/ https//:irpaai.com/definition-and-benefits/]

Cooper, L. A., Holderness Jr, D. K., Sorensen, T. L., & Wood, D. A. (2018). Robotic process automation in public accounting. Accounting Horizons. doi:10.2308/acch-52466

Lacity, M., Willcocks, L. P., & Craig ,A. (2015). Robotic process automation at Telefonica O2 .

Seasongood, S. (2016). Not just for the assembly line: A case for robotics in accounting and finance. 32. https://www.financialexecutives.org/Topics/Technology/Not-Just-for-the-Assembly-Line-A-Case-for-Robotic.aspx

IAASB. (2016). Exploring the Growing Use of Technology in the Audit, with a Focus on Data Analytics. In. NewYork: International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board.

PCAOB, P. C. A. O. B. (2017). Staff Inspection Brief. In (Vol. 2017/3): PCAOB Washington, DC.

Moffitt, K. C., Rozario, A. M., & Vasarhelyi, M. A. (2018). Robotic Process Automation for Auditing. Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting, 15(1), 1-10. doi:10.2308/jeta-10589

Alles, M., Brennan, G., Kogan, A., & Vasarhelyi, M. A. (2006). Continuous monitoring of business process controls: A pilot implementation of a continuous auditing system at Siemens. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 7(2), 137 - 161 .

Issa, H., & Kogan, A. (2014). A predictive ordered logistic regression model as a tool for quality review of control risk assessments. Journal of Information Systems, 28(2), 209-229 .

Li, H (2017) Three essays on cybersecurity-related issues. (Doctoral dissertation), The State University of New Jersey, New Jersey .

Deloitte. (2017). Deloitte Statement on Cyber-Incident. https://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/pages/about-deloitte/articles/deloitte-statement-cyber-incident.html

Palmrose, Z.-V. (1989). The relation of audit contract type to audit fees and hours. Accounting Review, 488-499 .

Alles, M. G., Kogan, A., & Vasarhelyi, M. A. (2002). Feasibility and economics of continuous assurance. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 21(1), 125-138 .

Kokina, J., & Davenport, T. (2017). The Emergence of Artificial Intelligence: How Automation is Changing Auditing. Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting, 14. doi:10 . 2308 / jeta-51730

Berruti, F., Nixon, G., Taglioni, G., & Whiteman, R. (2017). Intelligent process automation: the engine at the core of the next-generation operating model. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/digital-mckinsey/our-insights/intelligent-process-automation-the-engine-at-the-core-of-the-next-generation-operatingmodel

McClimans, F. (2016). Welcoming our Robotic Security Underlings. Point of View .

Hindle, J., Lacity, M., Willcocks, L., & Khan, S. (2018). Robotic Process Automation: Benchmarking the Client Experience. Knowledge Capital Partners .

Huang, F., & Vasarhelyi, M. A. (2019). Applying robotic process automation (RPA) in auditing: A framework. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 100433 .doi:10.1016/j.accinf.2019.100433

Chappell, D. (2017). Introducing Blue Prism. Robotic Process Automation for the Enterprise. In: Chappell & Associates San Francisco, CA.

Keenoy C.L. (1958), The Impact of Automation on the Field of Accounting, “The Accounting Review”, 33 (2), pp. 230–236.

Kokina J., Davenport T. (2017), The Emergence of Artificial Intelligence: How Automation is Changing Auditing, “Journal of Emerging Technologies in Accounting”, 14 (1), pp. 115–122,

Kotarba M. (2018), Digital Transformation of Business Models, “Foundations of Management”, 10, pp. 123–142,

Kaya C.T., Turkyilmaz M., Birol B. (2019), Impact of RPA Technologies on Accounting Systems, “Journal of Accounting & Finance”, 82, pp. 235–249.

Di Lernia C. (2014), Empirical Research in Continuous Disclosure, “Australian Accounting Review”, 24 (4), pp. 402–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/auar.12021.

Borthick A. F., Pennington R. R. (2017), When data become ubiquitous, what becomes of accounting and assurance?, “Journal of Information Systems”, 31(3), pp. 1–4, dx.doi.org/10.2308/isys-10554

Future of Financial Reporting Survey 2017 (2017), FSN The Modern Finance Forum, https://www.ac-countancyage.com/wpcontent/uploads/sites/3/2018/02/Workday_ffsn-survey-2017-the-future-of-fi-nancial-reporting.pdf (accessed 05.03.2019).

Tschakert N., Kokina J., Kozlowski S., Vasarhelyi M. (2016), The next frontier in data analytics, “Journal of Accountancy”, August, http://www.journalofaccountancy.com/issues/2016/aug/data-analytics-skills.html (accessed 15.08.2019).

Robotic Process Automation (RPA) Market Research Report- Forecast 2023 (2019), Market Research Fu-ture, https://www.marketresearchfuture.com/reports/robotic-process-automation-market-2209 (ac-cessed 25.03.2019).

Robotic process automation, Whitepaper (2015), EY, https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/ey-ro-botic-process-automation-white-paper/$FILE/ey-robotic-process-automation.pdf (accessed 10.04.2019).

Axson D.A.J. (2015), Finance 2020: Death by digital The best thing that ever happened to your finance or-ganization, Accenture, https://www.accenture.com/t20150902T015110_w_/us-en/_acnmedia/ Accen-ture/Conversion Assets/DotCom/Documents/Global/PDF/Dualpub_21/Accenture-Finance-2020-PoV. pdf (accessed 25.03.2019).

Future of Financial Reporting Survey 2017 (2017), FSN The Modern Finance Forum, https://www.ac-countancyage.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2018/02/Workday_ffsn-survey-2017-the-future-of-fi-nancial-reporting.pdf (accessed 05.03.2019).

Howieson B. (2003), Accounting practice in the new millennium: is accounting education ready to meet the challenge?, “The British Accounting Review”, 35, pp. 69–103, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0890-8389(03)00004-0.

The Future of Jobs Report 2018 (2018), World Economic Forum, http://www3.weforum.org/docs/ WEF_Future_of_Jobs_2018.pdf (accessed 26.04.2019).

Traditional outsourcing is dead. Long live disruptive outsourcing The Deloitte Global Outsourcing Survey 2018 (2018), Deloitte, https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/process-and-operations/us-cons-global-outsourcing-survey.pdf (accessed 10.04.2019).

Document information

Published on 03/02/23

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?