Abstract

Established in 1909, Tsinghua College was built on the base of a royal garden, and developed into a modern university through campus designs produced by Henry Murphy. The Auditorium, one of the Four Grand Buildings during Tsinghua׳s formative times, was a significant part of early construction and has become a symbol of the school. However, no thorough measuring work has ever been done to it since its completion in 1921. This paper delves into archives with combination of field survey and measurement, aiming to better understand the historical background in which the construction of the Auditorium was embedded, and technological and structural features of the Auditorium. Though the Guastavino system was indicated in the original design drawn by Murphy, concrete shell was applied in the end.

The first part combs up the intellectual origins and precedents of the campus planning by Henry Murphy. As the dome is a focal point of the study, a brief course on the history of dome construction in the West is needed. The third part, based upon field measurement in July 2013, compares the actual dome with its original design featured by the Guastavino method, deducing possible reasons that resulted in the differences, including architect׳s unfamiliarity with Guastavino Company and its parameters, considerations about cost, and local construction tradition.

Keywords

Guastavino system ; Dome ; Tsinghua University ; The Auditorium ; Structure

1. Introduction

The emergence and development of modern Chinese universities is an epitome of the top-down modernization in the first decade of the 20th century in China. Confronting the catastrophes caused by Boxer Uprising motivated by patriotic and anti-imperialistic sentiment in 1900, along with the Treaty of 1901 that fined China a large sum of money for war reparations, the Qing government started stated-led modernizing projects under a New Policy (xin zheng ). Learning from the West became an unanimous principle that featured the period of the New Policy (1901–1911), and a handful of schools and colleges were set up in line of Westernization, a synonym of modernization at that time. In addition to new curriculum and educational ideals, these newly built schools and colleges distinctly differed from traditional Chinese private schools in that Western influence is manifest in the physical construction and built environment of modern schools. For example, buildings of these modern colleges, such as the Beiyang Public School (present-day Tianjin University), considered the first modern college of China that was founded in 1895, two- and three-storied buildings made of brick and wood were fronted with Western facades and ornaments.

Tsinghua Preparatory School to America (qinghua youmei yiye guan ), known as Tsinghua University later which was founded in 1909, was somehow different from other contemporaneous state-sponsored schools. It was an “indemnity school,” as indicated in American newspapers, because the funding used to establish this school came from remissions of excessive part of the indemnity as prescribed in the Treaty of 1901 by the American government. A training school to prepare her students for advanced education in the US, Tsinghua had close ties with America, and even the administration of Tsinghua was put under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs instead of that of Education. 1

The selected site for Tsinghua was a former garden of a prince of the Qing, located in the North-western outskirts of Beijing. Up to 1911, two years after the decision of setting up such a school was made, Tsinghua was ready to recruit her first students, and the name was changed into “Tsing Hua College”. The special relationship between Tsinghua and the US government in that “its foreign faculties are all Americans, and its students are all trying for the honor of being sent to America, on the Boxer Indemnity Fund”2 resulted in administrative independence from the Chinese government during the tumultuous period between the 1910s and 1928s,3 in terms of curriculum, faculty, student communities, etc. Secured funding from abroad also allowed Tsinghua to expand her campus and added advanced facilities and equipments over years. Consequently, with rapid development of two decades, Tsinghua became a well-known higher educational institution.

It was a booming period of campus construction at Tsinghua in the 1910s and 1920s, and the campus planning and construction on campus during that period, such as the Southern Gate (also widely known as the Hall of Tsinghua College, the Second Gate, er xiaomen ), and Four Grand Buildings: the Auditorium, library, gymnasium, and Science Building, became a typical model of modern Chinese universities. 4 Nearly all famous buildings of Tsinghua that typified the built environment in her formative years were built up during that time. However, it remains very vague what examples the campus designs of Tsinghua referred, and for what reasons such patterns were adopted.

Toward the end of the 1920s, the main part of the campus of Tsinghua had already been put in order, and the Auditorium has been a landmark and symbol of Tsinghua University since its completion in April 1921. Interior renovations have been made to the Auditorium several times, but knowledge about its dome, which is the symbol of the symbols, is still a mystery to architects and scholars, partly because no change has ever been made to it. Hence, the author organized a full-scale measurement of the Auditorium in July 2013, with particular emphasis on its dome, to compare its structural form and technique construction with the original design found in Murphy Papers stored in the Sterling Memorial Library at Yale University.

The first part of this paper charts out the intellectual origins and precedents of the campus planning of Tsinghua College, and further elaborates the formal and structural characteristics of the Auditorium. Because the dome was the focal point of this paper, the second part gives a brief history of the construction of domes in the West up to the 1920s when the Auditorium was erected. The last part, based on recent data from field survey and measurement, compares the actual dome with its original design and deduces reasons for the differences.

2. Planning Tsinghua in the 1910s and the background of the construction of the Auditorium

The formulation and implementation of the early planning scheme for Tsinghua was closely intertwined with the social and historical background in which Tsinghua was embedded, her intimate connection with America, and the educational ideals and policies of her administrators.

2.1. Intellectual origins of the campus planning of Tsinghua

In the statement of design specifications, it makes clear that “[t]he University, for which Murphy & Dana are to prepare, immediately, a tentative block plan, will follow in general the plan of the American Universities, rather than the English plan of separate small Colleges.”5 Obviously the scheme for Tsinghua was, from its inception, based on American instead of English models of campus planning.

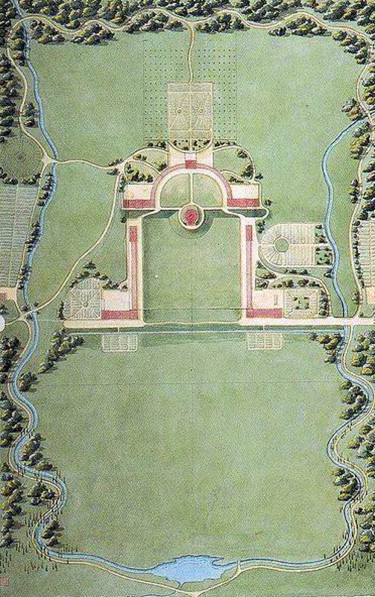

As Paul Turner elaborates, American campus planning deviated from the English enclosed quadrangular pattern in colonial times.6 One side of the quadrangular court was opened not only for sanitary reasons, but also in hope to match the vastness and an ideology of separation from the Old World.7 In America, preferable was an elongated campus, open at one end or partially at one side, as in the collegiate designs of Benjamin Henry Latrobe who played an important role in Jefferson׳s design for the University of Virginia, and in Joseph-Jacques Ramée׳s Union College in New York8 (Figure 1 ).

|

|

|

Figure 1. Plan of Union College, New York, 1812. Source : Paul Turner. Joseph Ramée. International Architect of the Revolutionary Era . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996:153. |

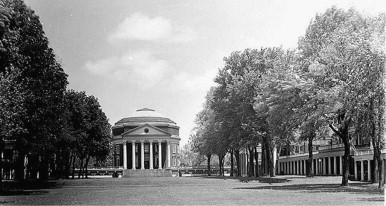

Though within this formula there were endless possible variations, the most influential one is the “Academical Village” of the University of Virginia designed by Thomas Jefferson in 1814. This village that aimed at promoting a collegiate life of faculty and students together consisted of a series of professors׳ houses (the “Pavilions”), alternating with groups of students׳ rooms, along the colonnaded sides of a mall (the “Lawn”), terminating at the north in a domed library (the “Rotunda”), and flanked to the east and west by gardens and outer rows of buildings (Figure 2 ).

|

|

|

Figure 2. Academical Village after reconstruction, Charlottesville, 1914. Source : Richard Wilson. Thomas Jefferson׳s Academical Village: The Creation of an Architectural Masterpiece . Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009:49. |

The essential character of Jefferson׳s design for the University of Virginia was determined by his vision of the ideal education. In his own college years, Jefferson׳s most rewarding experiences had been in his personal relationships with his teachers, and he evidently considered education to be the best when familial in character and based on close personal relationships.9 Jefferson׳s educational ideal was in fact largely American in spirit, and echoed the principles of other educators of the period in its collegiate commitment, its familial overtones, and its desire to withdraw from the life of cities and be a “village” unto itself, rather than being isolated from the outside world as in England, and such ideas became the touchstone for the campus planning of Tsinghua too.

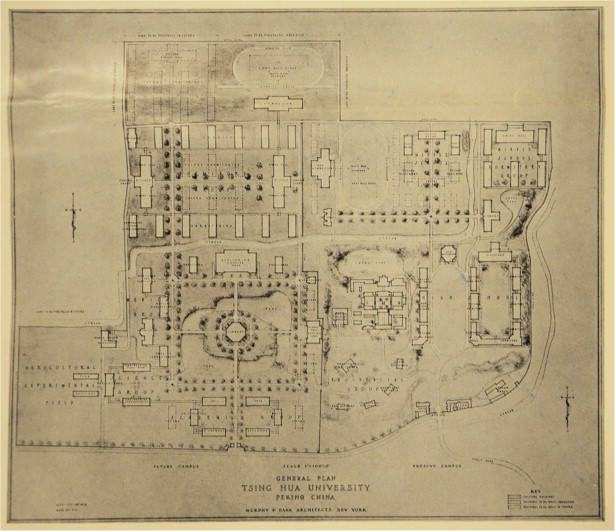

As such, the 1914 scheme for Tsinghua, which was the first serious plan of the entire campus produced by Henry K. Murphy, resonate with the intellectual and artistic trend of campus designs in the US at that time. The most popular pattern for a campus in America that emerged toward the end of the 19th century, within the Beaux-Arts context and the “City Beautiful” movement in America in the years following the Chicago Fair, was based on the form of Jefferson׳s University of Virginia: an extended rectangular space, defining a longitudinal axis, with a dominant structure as focal point at one end and subsidiary buildings ranged along the sides. Moreover, the fire that damaged Jefferson׳s Rotunda in 1895, followed by Stanford White׳s remodeling of it, brought the Virginia campus into the national news and also helped popularize it.10 The ordered monumentality of the Stanford plan was well suited to the new type of American university that emerged at the end of the nineteenth century, and the elongated rectangular form flanked with buildings on both sides was modeled in various ways both in the US and abroad.

As the President Zhou Yichun (spelt as Y.T. Tsur at that time) of Tsinghua was eager to develop the training school to a college and ultimately a future university,11 he contributed a lot for the rapid expansion of the school since his inauguration in 1913. As his contemporaneous commented, “President Zhou headed Tsinghua for four years and did more than other presidents for her development with great accomplishments. Grand buildings that mark Tsinghua have been erected in succession, and the curriculums have been greatly improved.”12 As Zhou persuaded the Ministry of Foreign Affair into purchasing the adjacent garden for future Tsinghua University, he invited an American architect, Henry K. Murphy for a three-day-long meeting in June 1914 to discuss adding more buildings for the school and a even more ambitious scheme for the future development (Figure 3 ).

|

|

|

Figure 3. Campus planning scheme by Murphy in 1914. Source : Murphy Papers. MS 231-Box 4, Folder 4. |

The plan produced by Murphy later is an imitation of the specific form of Jefferson׳s design – key elements including a mall lined with buildings arranged along both sides that defined a longitudinal axis, and a central structure as a focal point an extended rectangular space – became an emblem of the school׳s landscape, and began to exert a great influence on modern Chinese college planning (Figure 4 ). What is missing in Murphy׳s realized scheme of 1914 compared to American counterparts, however, is a subsidiary axis that enhances dramatic effects, so the lawn area at Tsinghua seems rather insipid by classically Beaux-Arts criteria. But it should be noted that the lawn area including the Auditorium and other buildings was only a central part of Tsinghua College of that time, and a much more ambitious plan for a university was also proposed on its west, but failed to be materialized.

|

|

|

Figure 4. Tsinghua University, 2013. Source : photo by the author. |

2.2. Architect and backdrop of the construction of the Auditorium

President Zhou Yichun (1883–1958), a native of Xiuning County, Anhui Province, got his Master׳s Degree in Education from Yale University in 1909.13 Upon his return he was assigned the vice president of Tsinghua College. When he became the second president of Tsinghua in 1913, he launched large-scale construction immediately and hired Henry Murphy as his architect. Zhou was quite confident to persuade the government of developing Tsinghua to a comprehensive university of the first class in China, partly because “the good architectural start it will have when the new buildings about to be built are completed,”14 hence it would be “more than likely to receive from the China Government the financial support necessary to carry out Pres. Tsur׳s plans for expansion.”15

By doing so, he introduced a wholesale American-style educational system to Tsinghua, and his educational policies “aim to set up an entirely Americanized university and Tsinghua is booming with construction on campus, and the Library, Science Building, the Gym, and the Auditorium have all been set up, and everything is imitating American universities.”16 On that score, Murphy was required to do two part of work: the finished working drawings and outline specifications for all of the buildings to be built immediately for the present “College” consisting of a Middle School and a High School, and to lay out the scheme for the ultimate development of a future “University”. Before Murphy intervened, several buildings had been erected in Tsinghua, one of which was designed by an Austrian architect Emil Sigmund Fischer.17 However, it was Murphy׳s reorganization of the space combining former gardens and his design of the lawn and the “Four Grand Buildings” that defined the character of the Tsinghua.

Both Zhou and Murphy were graduates from Yale, and more importantly, Zhou was the vice-president of the College of Yale-in-China in Changsha, in which Murphy excellently acted as the chief architect.18 It was not surprising that Zhou invited Murphy, who arrived in China in 1914 for the first time, instead of other foreign architects well based in Peking,19 to produce designs and campus planning for Tsinghua. However, it seemed Murphy did not know the role Zhou played in his Changsha project, yet he was excited to admit that the Tsinghua project would be “larger than all the rest of our Oriental work put together.” 20

Trained with Beaux-Arts inspired programs, Murphy graduated from Yale in 1899. He joined his partner, Richard Dana who also had connections with Yale,21 to open their architectural firm, Murphy & Dana Architects, in New York in 1908. Until 1914 Murphy and his firm worked on a series middle-class houses and small public buildings such as clubs, theaters and educational facilities. Because of their growing reputation on campus designs and also alumni of Yale, Murphy & Dana was selected by the Committee of Yale-in-China to design new buildings for a new college in Changsha in 1914.22 This project was the springboard for Murphy to expand his career to Asia, and after that Murphy was commissioned a series of missionary campus designs in China. In 1928 when the Nationalist Government established its capital in Nanjing, Murphy was appointed by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek as a councilor of Najing׳s capital planning, and he designed a national shrine close to the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum. As such, Henry K. Murphy became the most renowned American architect active in China in the first half of the 20th century, and was invited to deliver lectures in New Haven and other places in America.23

According to the memorandum of Henry Murphy and Zhou Yichun who met in June 13 to June 15, 1914, they discussed a number of critical issues relating to Tsinghua׳s general plan and construction.24 The most important of all concerned the selection of esthetic style:

“At first H.K.M. assumed that it was to be some form of Chinese; but on close study of the existing buildings, he found that none of them (with the exception of the “yamen” built by the Prince who formerly occupied the property) was really Chinese at all. The Chinese effect of the group comes almost solely from the gray brick of the walls, the gray Chinese tile of roofs and the fact that all but one of the buildings are only one story .… Although Pres. Tsur recognizes the educational value, to be Chinese, of a group of modern buildings in the Chinese style, as in the case of the new Yale Mission buildings at Changsha; he feels that the style, if at all well carried out, imposes many restrictions and limitations, from the utilitarian point of view, on the design of buildings intended for class-room and dormitory purposes. H.K.M. agreed with him in this, and advised that no attempt be made, in the new buildings, to carry out Chinese forms, except that the buildings should be of the same gray brick as the present buildings, and should be kept as low as would be consistent with economy of construction.”24

Zhou did not have a penchant for Chinese style. This was, as shown at the beginning of this paper, a sentiment echoing to the mindset of Chinese intellectuals at a time when Western influences began to infiltrate into every facet of Chinese society, in the aftermath of the Boxer Uprising. As a result, Murphy compromised to use Western styles for new buildings, but tried to apply Chinese materials and Chinese way of planning the ground and landscape. A respect of Chinese form and culture has underlined all Murphy׳s works in China, Tsinghua project included.

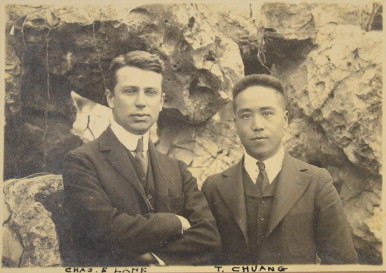

Other issues they agreed on in the memorandum included dates for production and revision of the blueprints which required Murphy and his firm to complete initial design in the early August of 1914, and hiring a superintendent of Murphy׳s selection to oversee the project in Peking. For the superintendent, Charles E. Lane was chosen and played an outstanding role in the next years, along with Zhuang Jun, a graduate from the University of Pennsylvania, who was hired by the Minister of Foreign Affairs as the Chinese architect in residence at Tsinghua25 (Figure 5 ).

|

|

|

Figure 5. Charles E. Lane and Zhuang Jun, representatives of the American architectural firm and Chinese authorities, respectively. Source : Murphy Papers. MS 231-Box 4, Folder 4. |

Regarding the Auditorium, the memorandum specifies if possibly combined with Library building it should be able to “seat one thousand persons, all with good view of Stage; Impressive Entrance, and easy exit facilities. Large stage (for graduation exercises, concerts etc.) with convenient separate entrance from outside.”26 Viewed from what was eventually erected, it is evident that the Rotunda at the Academical Village in the University of Virginia, which became a popular model in American campus design had great influence on Murphy׳s envisioning of Tsinghua. The specific form and crucial elements of Jefferson׳s design, i.e. a elongated lawn lined with buildings as the main axis with a classic domed structure at terminus, were embodied in Murphy׳s design.

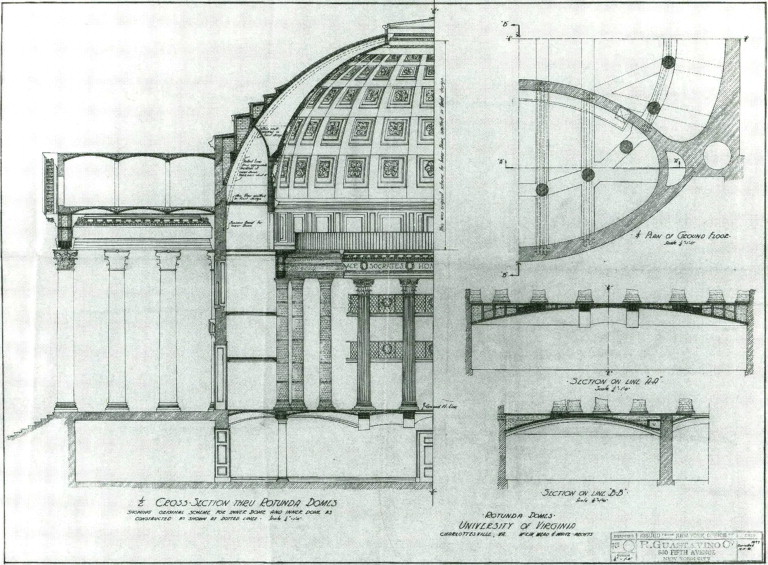

The image of Jeffersonian Rotunda is crucial of understanding Tsinghua׳s campus design. Jefferson׳s “academical village” was considered to represent perfectly the ideal of an intimate and enlightened dialog between students and teachers, and above all, the ideal of democracy and American Republicanism – the very objectives of Chinese in search of cultural and political modernity. In 1895, the Rotunda was severely damaged by fire, and Stanford White was hired to remodel the building and to design additional academic structures for the southern end of Jefferson׳s Lawn (Figure 6 ). In the reconstruction of the dome of the Rotunda, Stanford employed Guastavino Company to apply a fireproof structure (Figure 7 ). It was the same company and its technique that Stanford and his firm collaborated on many other famous educational projects including those in Columbia University and New York University.

|

|

|

Figure 6. The Rotunda at the University of Virginia caught in fire, 1895. Source : Susan Tyler Hitchcock. The University of Virginia: A Pictorial History . Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012:84. |

|

|

|

Figure 7. Section of the reconstructed Rotunda by Stanford White, 1903. Source : Janet Parks and Alan G. Neumann. The Old World Builds the New: the Guastavino Company and the technology of the Catalan vault, 1885–1962 . New York: Columbia University Press, 1996. |

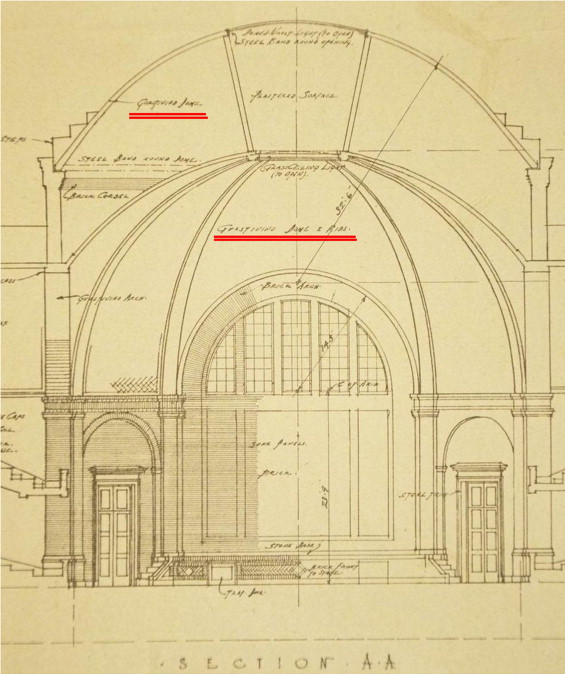

In Murphy׳s original design for the Auditorium, he used the same technique as Stanford did in the Rotunda, i.e., Guastavino system of constructing a dome. Most strikingly, both designs had oculus on the top, a benefit of the Guastavino technique (Figure 8 ). Though the design was abandoned in the end, the introduction of campus design and construction technique most popular in America to China was a vivid embodiment of global circulation of professionals and technologies in the turn of the 20th century, as well as an increasing Western influence in China.

|

|

|

Figure 8. Section of the original design for the Auditorium by Murphy in 1916. Note the two places (underlined in red by the author) referring to “Guastivino Dome & Ribs,” but “Guastavino” was misspelled for “Guastivino”. Source : Murphy Papers. MS 231-Box 4, Folder 4. |

3. A brief introduction of Guastavino Dome and Ribs System

The dome is the most significant element of the Auditorium. In its original design, the construction technique of the dome was clearly indicated as “Guastavino Ribs and Dome System”. What does it refer? To answer this question, it is necessary to briefly review the history of vaulting and dome construction in the West.

Dome structures made of various materials have a long architectural lineage. The basic barrel form, which appeared first in ancient Egypt and the Middle East, is in fact a continuous series of arches deep enough to cover huge space beneath it. Ancient Roman architects introduced that two barrel vaults that intersected at right angles formed a groin vault, which could cover rectangular areas when repeated in series. The Romans also discovered the large-scale masonry hemisphere that span large space and became a spectacular unifying element, as exemplified in the Roman Pantheon, a remarkable prototype for numerous domed buildings for millenniums to come.

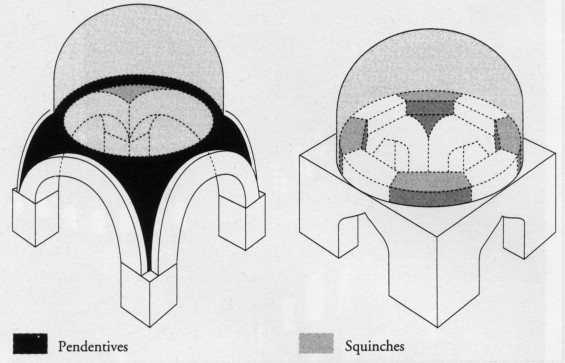

Vaulting was continued and improved in the Byzantine Empire and in the Islamic world. Two ways of resting a dome upon a square base were achieved by squinches and pendentives (Figure 9 ). Four squinches, one at each corner, effectively turn a square into an octagon – a shape on which it is possible to construct a dome, which was also used in the Auditorium at Tsinghua in the 1910s as can be seen in the next section.

|

|

|

Figure 9. Pendentives and squinches. Source : G. A. T. Middleton. Modern Buildings, Their Planning, Construction And Equipment . (Vol. 1). The Caxton Publishing Company, 1921. |

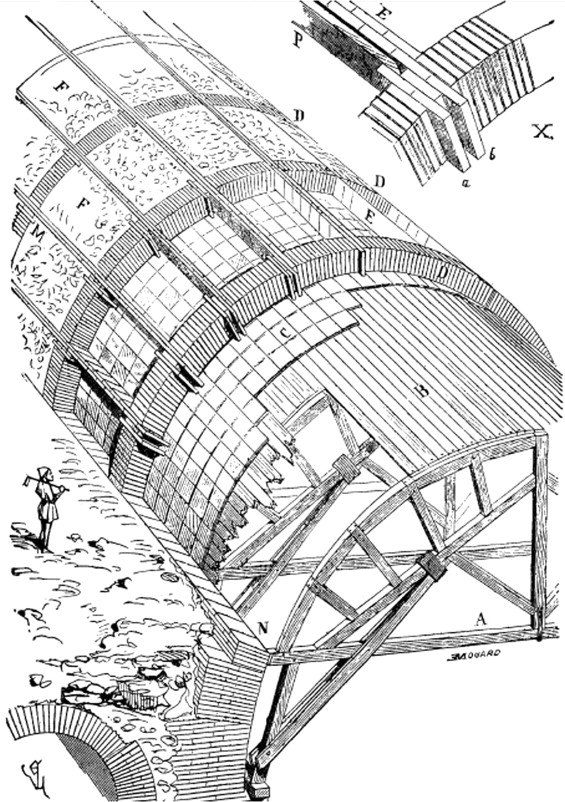

It is noteworthy that elements of conventional vaults are held together by friction produced by pressure of the elements against each other under the force of gravity.27 Because the vault׳s thrusts are concentrated at all four corners, its supporting walls need not be massive and require buttressing only where they support the vault. Moreover, Roman vault requires great precision in stone cutting, an extraordinarily expensive art that was declined in the West with the fall of Rome (Figure 10 ).

|

|

|

Figure 10. Presumed laborious work of centering the manner of the Romans in the construction of their concrete vaults. Note enormous wooden frame (A), single ply board (B), and a tile revetment-centering (C). Source : George R. Collins. The Transfer of Thin Masonry Vaulting from Spain to America. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians . Vol. 27, No. 3 (Oct., 1968). |

However, certain construction techniques of Roman domes were preserved. Inside the concrete hemispherical dome of the Pantheon, “with five diminishing rows of coffers verging toward the oculus,” vertical partitions of the coffering effectively serve as ribs, although this feature does not dominate visually.28 It is because of the ribs that an oculus can rest on the top inviting even light to shine through. Although the techniques employed were different, in practice domes built in the Renaissance, like Roman domes, also comprise a thick network of ribs supporting much lighter and thinner infilling, and both had a large opening on the top except that a lantern was supported by ribs in the Renaissance as in Brunelleschi׳s and Michelangelo׳s masterpieces.

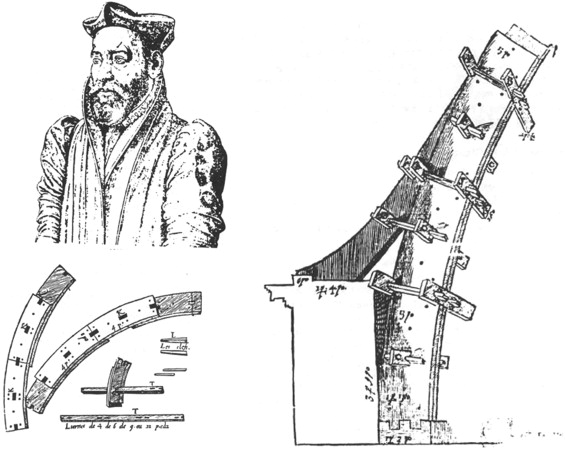

Due to economic considerations, wood was widely used in place of masonry ribs to construct of domes for many centuries. During the mid-16th century, Philibert Delorme (1515–1570), a prominent architect of the French court, invented a new means of vaulting arched and domed spaces by laminating short curved segments of wooden planks into long, continuous structural ribs, so called “Delorme׳s Manner”. Planks of Delorme׳s dome were inexpensive, prefabricated, and easy to assemble.29 As no centering was required, Delorme׳s wooden dome was a major advance over other timber vault construction or laborious methods of vaulting in brick or stone (Figure 11 ).

|

|

|

Figure 11. Philibert Delorme and his invention of building a dome with laminated curved planks. Source : Douglas Harnsberger. In Delorme׳s Manner. In David Yeomans (ed.) The Development of Timber as a Structural Material . Aldershot: Ashgate Variorum, 2005. |

Thomas Jefferson who was the American Ambassador in France carefully studied Delorme׳s Manner of constructing domes, and upon his return to his hometown in Charlottesville, he used this method to build his Monticello and the rotunda at the University of Virginia, both milestones in American architectural history.30 However, though lightweight, wooden ribs were vulnerable to fire. For example, the dome of the rotunda at the University of Virginia was destroyed by fire in 1895 and was reconstructed by Stanford White afterwards.

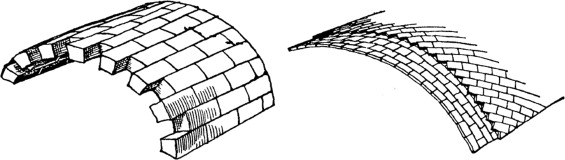

It was not until the late 19th century that a “new” technique of timbrel vault appeared in the US. Contrary to conventional vault, the timbrel vaults were thin and made of broad thin terracotta tiles that are laid “flat” with the curve of the vault, usually in two or more layers, deriving its rigidity not from massiveness or thickness but rather from its type of curvature (Figure 12 ).

|

|

|

Figure 12. A comparison of two methods of building a dome: rigidity deriving from gravity (left) and cohesiveness (right). Source : George R. Collins. The Transfer of Thin Masonry Vaulting from Spain to America. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians . Vol. 27, No. 3 (Oct., 1968). |

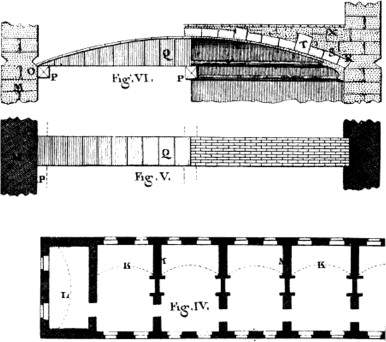

In fact, in the 17th century craftsmen in Roussilon area of South France developed a type of flat vault, so called Roussilon Vault, to be used in both public and private buildings. These vaults were built of one or more layers of thin tiles laid in quick-setting plaster mortar on a movable centering with a low elliptical profile. This technique was brought to Catalonia of Spain later, and because of cheap cost, for centuries “the builders of Catalonia and Roussillon had employed light, flat, tile vaults in barns, stables, granaries, coach houses, and even churches”31 (Figure 13 ). This system of vaulting differs from traditional vault construction in that they are thinner, have a lower rise, and are capable of covering greater spans than stone vaults, setting the foundation for Catalan vaulting manner to which the Guastavino system belonged. This method of vaulting, later considered as a symbol of the Catalan nationalistic movement, cannot only be used to build roofs and floors, but also applied to walls and facades, as innovatively shown in Antonio Gaudi׳s and Cesar Martinell׳s works.32

|

|

|

Figure 13. Roussilon vault as in Versailles: War, Marine, and Foreign Office drawn by Jacques-François Blondel. Source : W. Knight Sturges. Jacques-François Blondel. The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 11.1 (March 1952:16–19). |

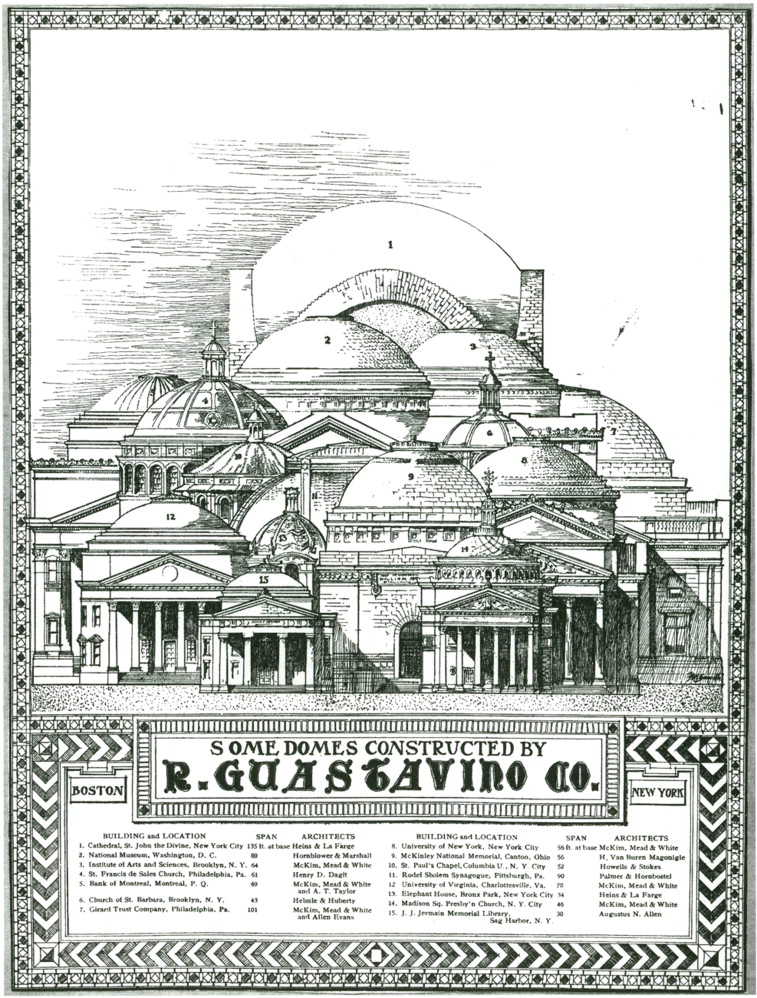

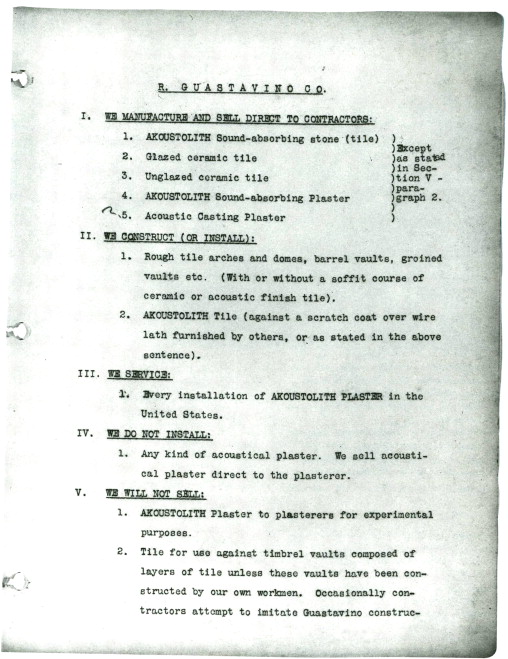

Rafael Guastavino, Sr. (1842–1908) is the pivotal figure that popularized this vaulting method and introduced it to the US. Trained in the art of Catalan construction and timbrel vaulting, Guastavino immigrated to the United States in 1881, bringing with him the technique of Catalan vaulting and his son, Rafael Guastavino, Jr. The elder Guastavino termed his vaulting method “Guastavino Dome and Ribs system” and focused on marketing the fireproof abilities of his construction methods and founded the Guastavino Fireproof Construction Company in 1889 (Figure 14 ). Meanwhile, newly invented Portland cement was used in place of mortar, so that workers were able to work overhand in assembling the vaults saving a lot of money and time, which neither freshly poured-concrete nor formed voussoir arches. Moreover, in the 1920s, Rafael Guastavino, Jr., collaborated with Harvard׳s acoustical expert, Wallace C. Sabine, in devising an acoustically effective tile for vault and wall surfaces, hence the Rumford Tile and its upgrade Akoustolith, were able to effectively absorb sounds to improve acoustic quality.33 For the next 70 years since its establishment, the Guastavino Company which obtained 24 patents all together would play a significant role in proliferating dome construction in other building types such as commercial and religious institutions34 (Figure 15 ).

|

|

|

Figure 14. Picture showing supporting ribs between outer and inner domes of Washington National Museum of Natural History. Taken during renovation of the museum in the 1990s. Source : by courtesy of Douglas Harnsberger. |

|

|

|

Figure 15. A pamphlet showing famous domed buildings constructed by the Guastavino Company. Source : Janet Parks and Alan G. Neumann. The Old World Builds the New: the Guastavino Company and the technology of the Catalan vault, 1885–1962 . New York: Columbia University Press, 1996. |

The introduction of the steel frame and domestic Portland-cement production, the imperative of developing fireproof-construction techniques, and the flowering of large-scale public architecture in America׳s cities presented tremendous opportunities for the Guastavino׳s system. In the years preceding the advent of Guastavino construction in America, significant dome construction generally appeared limited to State Capitol buildings and some educational institutions.35 These domes were typically of heavy masonry construction or cast iron, requiring metal framework to support the dome itself. Besides, finished Guastavino work was so attractive that the company׳s vaults began to be installed for purely esthetic reasons, apart from a building׳s structural system.36

When the 20th century opened, “Guastavino” became a house-hold word among American architects and the system of constructing domes was incorporated in most building manuals. Both headquartered in new York, Murphy׳s Architectural firm should have known Guastavino Company and their recently completed projects such as the rotunda of the University of Virginia, campus buildings at the United States Military Academy at West Point and Columbia University. However, no evidence has been found that the two had ever collaborated. It is in Tsinghua project that Murphy intended to introduce a European-rooted technique to another continent.

4. Field measurement and analysis of the Auditorium and its dome

Since its completion in April 1921, the Auditorium has gone through numerous renovation and maintenance.37 For example, in the 1960s, the foundation of the Auditorium was changed into an air-raid shelter, due to tense relation with the Soviet Union; in 1991 on the eve of Tsinghua׳s 90th anniversary, the inner dome was plastered; and then with acoustic renovation all chairs were replaced and the basement was enlarged in 2009. However, the Auditorium was never measured on a full scale, as no drawings or any records on the dome that is concealed beyond sight has ever been discovered, except for the original design of the dome produced by Murphy as shown in Figure 8 .

Therefore, the author organized students from the School of Architecture at Tsinghua University to measure the Auditorium in July 2013.38 Aware of the previous work, we put our emphasis on the actual structural form of the dome, in comparison to the original design.

4.1. Field measurement of the dome of the Auditorium

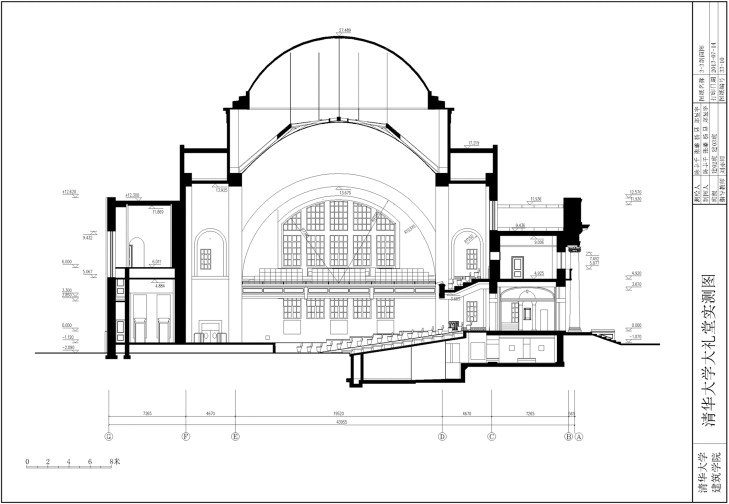

The Auditorium is a two-storied building. The ground floor, with a total area of 1156.0 m2 , is arranged with the entrance hall, stalls, the stage and dressing room, while balconies, film project room, audio control room and alike are laid out on the second floor totaling 659.2 m2 . The total height from the entrance hall to the summit of the outer dome, covered with copper, is about 27.4 m, and 19.6 m to the apex of the inner dome. The maximal rise within the building (from the lowest point on the first floor to the apex of the inner dome) measures 21.8 m (Figure 16 ).

|

|

|

Figure 16. Longitudinal section of the Auditorium. Source : Drawn by Yang Ao. |

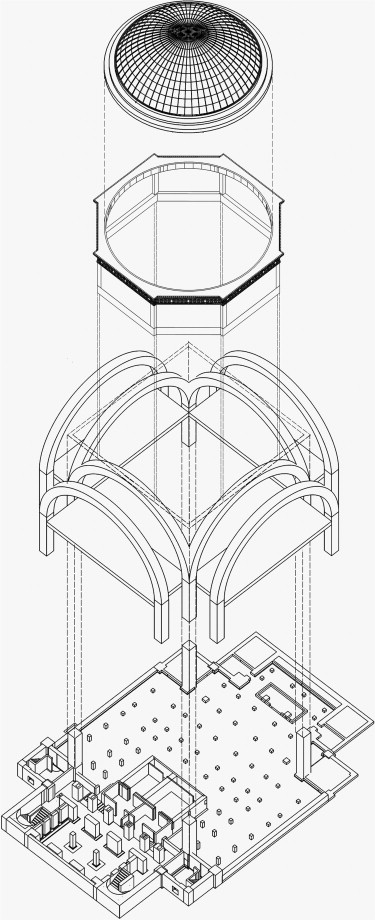

The plan of the Auditorium is based on a square, and adjunctive space is extended from four sizes with extra additional space in the south and north: the southern additional space is used as entrance hall, and the one on the North as dressing room. As a square is an ideal structural form that guarantees mechanical balance and stability, the four columns on each corner of the square constitute the fundamental structural system of the Auditorium that spread compression from the above unto the earth. The four parts that extends from the basic square are covered by cylinder vaults in a perfect hemispherical shape. Though theoretically no thrust exists at the foot of the vaults, four brick-framed tubes, used as stair cases and transitional spaces for side doors, are added at each of four corners to reinforce stability (Figure 17 ).

|

|

|

Figure 17. Structural analysis of the Auditorium. Source : drawn by Sun Xudong and Cheng Kun. |

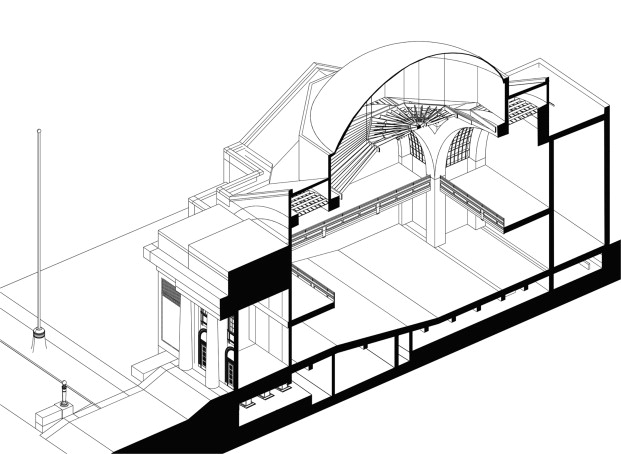

According to field survey, the shape of the dome of the Auditorium is an octagon which is formed by connecting one third of each side of the square in succession, forming squinches that ease the transition from a cubic base to the hemispherical dome. The eight sides of the octagon is made by concrete that form circular beams to support the six-meter-high drum and a hemispherical concrete dome above it (Figure 18 ). Reinforced bars extruding from columns and the shell along with imprints of wood moldboards on the shell can be clearly seen all around inside the dome. Columns at corners of the octagon that both buttress the drum and support the dome are also made in concrete, and they contort corresponding to the latitude of the hemisphere at the base, an amazing achievement of construction of that time. (Figure 19 ).

|

|

|

Figure 18. Circular concrete beams supporting the drum inside the dome. Source : photographed by Cheng Kun. |

|

|

|

Figure 19. Concrete columns supporting the concrete shell dome, contorting with circumference of the concrete hemisphere at the base with visible reinforced bars around. Source : photographed by Cheng Kun. |

Below the concrete dome there is a ceiling which forms the inner dome, and maximal height between the concrete shell and inner ceiling measures approximately 7.5 m. The ceiling is fixed beneath an inner octagonal wooden frame hung upon the concrete shell by 10 stranded steel wires (eight at the middle of each side and two at the center) from above, and beneath wooden ribs that connect the keel frame with circular concrete beams of the drum (Figure 20 ). Interestingly, the way wooden ribs are assembled is similar to the aforementioned Delorme׳s manner, but the ceiling in this case is held beneath the frame (Figure 21 ). Apparently, the ceiling forms a fake dome inside that becomes closer to audience and better matches acoustic principles. Judging from some part of the ceiling that peeled off, as it was remade in about two decades ago, the ceiling was made by fibrous plaster painted in gray green.

|

|

|

Figure 20. The inner octagonal wooden keel frame and the laminated beams connecting with the drum. Source : photographed by Cheng Kun. |

|

|

|

Figure 21. Section analysis of the Auditorium. Source : drawn by Sun Xudong and Cheng Kun. |

Therefore, the dome of the Auditorium is a double-shell structure. The outer dome is a concrete shell, covered with copper and painted with asphalt, and it is real structural part element that also resists water, while the inner dome is basically a plastered ceiling that forms a hemispherical shape.

4.2. Selection of construction techniques of the dome

According to field measurement, a reinforced concrete shell, rather than the Guastavino Dome and Ribs System, was used in the Auditorium. It is noteworthy that concrete structure was even more expensive than timbrel vault in the world, and normally, timbrel vault as exemplified by the Guastavino domes was widely used in relatively poor regions abounded with cheap labor but with limited access to expensive materials such as steel, concrete, etc.39 The choice of concrete instead of the relatively low-tech Guastavino at the time when China was impoverished and weak is somewhat astonishing.

In his letter of June 2, 1918 addressing to his partner in New York, Murphy discussed the style and techniques for the dome of the Auditorium that was under construction:

“Lane׳s Auditorium details are coming along well, though he has much still to do in the way of drawing. I urged Chao40to approve the use of Guastavino׳s Akoustolith [the $17,500 (gold) estimate, with the additional stairs required, … really amounts to about $28,000 (gold)] for the inner ceiling of the dome, barrel vaults, and certain parts. Chao is favorable, and will put the style in the budget; but of course it may be turned down by the ministry. The walls are to be of the sand lime brick, and the floor of Japanese cork tile … Lane׳s idea is to spray the dome ceiling in colors - red and gold and blue, to get a (?) effect; but I have warned him against getting it too dark, in trying to get it too rich. I favor more gold and lime red.”41

Murphy continued to discuss lighting issues and choice of lamps in this letter. Obviously he had given up the idea of an oculus to invite daylight as in the original scheme (Figure 8 ) which derived from Stanford White׳s reconstruction of the Rotunda, but still insisted on employing Guastavino to construct the dome. However, a careful reading of this letter shows that Murphy misspelled “ Akoustolith” for “Akouslotith,” while in the original section scheme Guastavino was misspelled for “Guastivino” twice. It is likely that neither Murphy׳s office nor Murphy himself was familiar with the Guastavino Company and how it was operated. It should also be noted that the Auditorium as of today deviates from Murphy׳s visualization dramatically, both in structural form and the interior effect such as ceiling color.

If Murphy had any knowledge that Guastavino Company only sold or installed domes on condition that they were “constructed by our own workmen,” (Figure 22 ) he would not recommend the Guastavino Dome and Ribs system to his client as late as in 1918. Rafael Guastavino, Sr. built Boston Public Library in 1889, the first grand vaulted building of Guastavino Co., with a cost of $85,554.04,42 and made the rules that domes could only be constructed under close supervision of technicians from the company. Stanford White employed Guastavino Company to rebuild the dome of the Rotunda in 1903, which spans 23 m with a cost of $57,773.43 The span of the Auditorium at Tsinghua is 18.3 m, close to that of the Rotunda. Therefore, taking inflations and cost for technicians-in-residence abroad for the project in Tsinghua in the late 1910s, the estimated cost for the Auditorium must far exceeds $28,000 as Murphy indicated in his letter.

|

|

|

Figure 22. Instructions to salesmen from the salesmen׳s manual. It states clearly that “we will not sell tiles for use against timbrel vaults composed of layers of tile unless these vaults have been constructed by our own workmen.” Source : Janet Parks. Documenting the Work of the R. Guastavino Company. APT Bulletin . Vol. 30, No. 4 (1999): 21–25. |

As is well known, Chinese craftsmen, though skillful with timber structure, were inexperienced with masonry, and it is unlikely to find qualified workers to construct timbrel vaults, let alone possible solutions to acoustic problems inside the Auditorium. In contrary, notwithstanding cost and sophistication of construction, concrete was used in China as early as in 1909,44 and then was widely used in a number of governmental buildings under the aegis of the New Policy in the first decade of the 20th century. Despite high cost (yet relatively more economic than the Guastavino dome), concrete shell became a practical solution, yet another challenge to local workers and contractors. As one of the Four Grand Buildings, the Auditorium outmatched the other three by both length of construction and cost (Table 1 ).

| Building names | Dates of construction and completion | Floor area (m2 ) | Total cost (yuan ) | Average Cost (yuan per m2 ) | Contractors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Library | 1916.4–1919.3 | 2114.44 | 175,000 | 82.76 | Tai Lai Co. |

| Gymnasium | 1916.4–1919.3 | 3593 | 244,500 | 68.04 | Tai Lai Co. |

| Science Building | 1917.9–1919.9 | 3549 | 124,000 | 34.93 | Gongshun Co. |

| Auditorium | 1917.9–1921.4 | 1843 | 155,000 | 84.10 | Gongshun Co. |

Source : Writing group of history of Tsinghua University. “Buildings on Campus, Library Books and Publications”. Manuscript of the History of Tsinghua University . Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1981:59. Cost information see Qinghua Zhoukan (Tsinghua Weekly). 1921.4.

Finally, double domes was hardly an architectural image ever seen in China, while an inner ceiling that reduced interior height better conformed to Chinese tradition. In his letter to Murphy on March 1, 1917, President Zhou Yichun mentioned that “[A]s the Library and Gymnasium cost us far too much, I gave Mr. Lane explicit instructions to cut down expense on the two buildings (referring the Auditorium and the Science Building) as far as possible, compatible with good substantial construction”45 . Because of restrained budget as well, a much cheaper ceiling was built in place of inner dome.

5. Conclusions

In order to expand Tsinghua from a language training school to a higher educational institution, Zhou Yichun launched the construction of major buildings and facilities on campus including the Auditorium. Historiographically, it was not until the 1980s when the campus designs and construction of Tsinghua became a serious research subject, and so far existing research falls into three main groups. The first is historical survey of the site of Tsinghua based on archeological discovery in recent years, which traces the historical origins of the former royal gardens and their relations to a modern college.46 Second, scholars looked into the establishment of Tsinhgua and her development, with a research focus on the formation of cultural landscape of the school. Third, information such as architects, contractors, sources of construction materials have also been studied, and those on Henry Murphy is the most productive research of all.

However, research on all three fronts on the research of Tsinghua׳s campus construction needs to be deepened and verified, especially for the last two. For example, no research on the intellectual origins or precedents is found, and no differentiation is made between the English model of planning campus and American one at the turn of the 20th century. When it comes to early construction on campus at Tsinghua, the following claim is oftentimes quoted without any doubt: “almost every aspect of Tsinghua College including curriculums, programs, textbooks, teaching methodologies, and not the least, facilities and buildings of all departments, are based on English and American models”.47 In fact, as Paul Turner has delicately elaborated, there is substantial difference between the campus planning of the two countries, not to mention diversity of American campus designs and transformation in history.

Regarding the central part of Tsinghua that includes the Auditorium, the lawn and flanking buildings, it is well-known that the Auditorium is a reduced imitation of the Rotunda of the University of Virginia, and the planning of the area a derivation from Academical Village. However, it remains largely unknown how or whether the two campuses are connected. Besides, no serious effort on pivotal figures such as Zhou Yichun, Zhao Guocai, C.E. Lane, Zhuang Jun amongst others can be found. Even research on Murphy deserves more work, though Murphy was the subject of some of the best work on modern Chinese architectural history.48 As such, painstaking archival work and comparative research in a global context will be two possible ways to deepen research of early campus planning and construction at Tsinghua.

As an essential part of the state-led modernization (or more accurately a wholesale Westernization) of the New Policy of the Qing, imitation of the West in all walks of Chinese society was omnipresent. In regard to physical construction, Western technologies, architectural styles, planning theories, and personnel were systematically introduced into China at a unprecedented rate. The building of the Auditorium in the 1910s showcases the nuanced interconnection with America, as exemplified in the attempted use of Guastavino dome and ribs system that was so popular in the Northeast region of the United States at that time. We cannot help imagining what if that technology had been made to the Auditorium, which must be an imposing image epitomizing modern Chinese architecture.

As discussed in previous pages, the technology used for the dome of the Auditorium was distinctly different from its original design. Both architects and local conditions contributed to the logic of technological selection in this case. However, the realized dome of the Auditorium in concrete shell was still the most advanced technology in the world at that time. The concrete dome was skillfully made with sophisticated construction techniques, and no fatal damage has ever been found on the dome in the past century since its completion. The dome of the Auditorium is an important episode of the technological development in modern Chinese history, reflecting how technologies originating in the West and professionals helped connect China to the outside world in the early 20th century. It is equally intriguing how some technologies were applied in place of others in specific local settings. As construction technology has been largely overlooked in modern Chinese architectural history, continuous research in this field, concerted with scholars from mechanics and civil engineering, may probably produce important work.

Notes

1. Wei Songchuan. A Study of Campus Planning and Architecture of Tsinghua University. Master thesis of School of Architecture, Tsinghua University. 1995:10–11.

2. Tsing Hua College. Memorandum Report of Interviews of June 13, 14, 15, 1914, at Tsingh Hua, Peking, China, between President TSUR & H.K. Murphy. June 26, 1914. Murphy Papers.

3. Since 1928 onwards, “the educational policies of Tsinghua embarked on a new era of creation from the imitation of its American model.” Qiu Chun. “Progress of Tsinghua׳s Education”. Qinghua Niankan (Tsinghua Annals). 1927. Collected in Historical Research Section of Tsinhgua University (ed.). Selected Historical Materials of Tsinghua University (Vol. 1). Beijing: Tsinghua University Press, 1991: 272.

4. Tsinghua was one of the first four universities that were designated as the National Preserved Cultural Relics. The other three are National Wuhan University (present-day Wuhan University), Northeast University and Yenching University (present-day Peking University). In a Forbes-conducted global selection, Tsinghua was also nominated as one of the 100 most beautiful universities in the world.

5. Tsing Hua College. Memorandum Report of Interviews of June 13, 14, 15, 1914, at Tsingh Hua, Peking, China, between President TSUR & H.K. Murphy. June 26, 1914. Murphy Papers.

6. Amongst earliest American colleges, Harvard was established in 1642, William & Mary in 1693, Yale in 1701, and Princeton in 1746. All are the earliest colleges in the New World during the colonial times, and none followed a quadrangular pattern in layout. See Paul Turner. Campus , An American Planning Tradition . Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1984.

7. Paul Turner. Campus , An American Planning Tradition . Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1984.

8. Union College was founded in 1811, 4 years before the construction at the University of Virginia started. See Paul Turner. Joseph Ramée. International Architect of the Revolutionary Era . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

9. Hugh Howard. Thomas Jefferson: Architect . New York: Rizzoli, 2003.

10. Stanford White built other educational edifices in American universities such as library at New York Universities with the same construction technique. MMW (Mckim, Mead and White), of which White was an associate, built magnificent buildings employing Guastavino Co. to build large domes in the end of the 19th century, such as Low Library at Columbia University. Domed architecture was widely adopted in blosoming American cities in the Northeast toward the end of the 19th century, as classic landmarks were badly needed in rapid urbanization in America in the time.

11. Luo Sen. Historical Development of Planning and Architecture of Tsinghua University, 1911–1981. Xin Jianzhu (New Architecture). 1984/4: 2–14. See also Luo Sen. Retrieving Campus Construction of Tsinghua University (A Commemoration of the 90th Anniversary of Tsinghua University). Jianzhushi lunwen ji (A Collection of Architectural Historical Papers) Vol. 14. Beijing: Tsinghua University Press, 2001: 24–35. The latter paper includes an earliest planning blueprint so far existing, a solid proof that counters the argument of no planning was ever made to Tsinghua College in the 1910s. See also Miao Rixin. A Historical Survey of Xichun Garden and Tsinghua Garden. Beijing: Tsinghua University Press, 2010: 388.

12. Anonymous author. “History of Our University”. Commemorative Brochure of the 20th Anniversary of Tsinghua University. Collected in Historical Research Section of Tsinhgua University (ed.). Selected Historical Materials of Tsinghua University (Vol. 1). Beijing: Tsinghua University Press, 1991: 49.

13. Jin Fujun. jinian zhou yichun xiaozhang danchen 130 zhounian (In Honor of the 130th Birthday of President Zhou Yichun). Shuimu Qinghua . 2013/11: 19–25.

14. Other reasons President Zhou gave are (1) there were no great national universities in China at the time; (2) advantage of Tsinghua׳s location in Beijing, the capital of the Republic, and it was a governmental institution; and (3) its close connection with the US.

15. Tsing Hua College. Memorandum Report of Interviews of June 13, 14, 15, 1914, at Tsingh Hua, Peking, China, between President TSUR & H.K. Murphy. June 26, 1914. Murphy Papers.

16. Qiu Chun. “Progress of Tsinghua׳s Education”. Qinghua Niankan (Tsinghua Annals). 1927. Collected in Historical Research Section of Tsinhgua University (ed.). Selected Historical Materials of Tsinghua University (Vol. 1). Beijing: Tsinghua University Press, 1991: 271.

17. Luo Sen. Historical Development of Planning and Architecture of Tsinghua University, 1911–1981. Xin Jianzhu (New Architecture). 1984/4: 2–14.

18. Marry Dounce. Yale Leading China Toward the Higher Education. The Sun. 1917–11–18. Murphy Papers. When Murphy met Zhou Yichun in June 1914, it seemed he did not know the role Zhou played in the College of Yale-in-China. In his letter of July 17, 1914 addressing to Dana, he claimed he and Zhou “never met before, and Pres. Tsur׳s action in engaging me after only a few hours׳ talk, without ever having seen me before, or nay of our work.” See Murphy׳s letter to Dana on July 17, 1914. Murphy Papers. Based on this letter, Jeff Cody in his renowned book on Murphy also deduced connections with Yale University of both Zhou Yichun and Henry Murphy was the only reason that Murphy got the commission, but the fact can be more nuanced as Zhou also played a critical role in Yale-in-China project since the late Qing. For Cody׳s deduction, see Jeffery Cody. Building in China: Henry Murphy׳s ‘Adaptive Architecture’ , 1914–1935. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 2001: 45.

19. One of Murphy׳s main competitors was Fellows & Associates that designed Cheloo Medical University.

20. Murphy׳s letter to Dana on July 17, 1914. Murphy Papers.

21. Dana was a graduate from Harvard (1901) and Columbia (1904), and received a Bachelor of Fine Arts from Yale. See Jeffery Cody. Building in China: Henry Murphy׳s ‘Adaptive Architecture’, 1914–1935 . Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 2001: 20–23.

22. After the College of Yale-in-China, Murphy produced designs for Tsinghua College (1914), Shanghai University (hujiang daxue, 1915), Fudan Christian University (1919), Fukien Union Medical College (1918), Ginling Women׳s College (1919) and Yenching University (1920). The International Banking Corporation also commissioned him to design six China branches between 1917 and 1923. In other regions of Asia such as Tokyo and Seoul Murphy also had imprints of his works. See Jeffery Cody. Building in China: Henry Murphy׳s ‘Adaptive Architecture’, 1914–1935 . Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 2001: 107–108.

23. Murphy Papers.

24. Tsing Hua College. Memorandum Report of Interviews of June 13, 14, 15, 1914, at Tsingh Hua, Peking, China, between President TSUR & H.K. Murphy. June 26, 1914. Murphy Papers.

25. Zhuang Shitao. My Late Father Zhuang Jun, the master architect of the 1901 Indemnity. Dang An Chun Qiu (Chronicles of Archives). 2010/4: 34–45.

26. Tsing Hua College. Memorandum Report of Interviews of June 13, 14, 15, 1914, at Tsingh Hua, Peking, China, between President TSUR & H.K. Murphy. June 26, 1914. Murphy Papers.

27. George R. Collins. The Transfer of Thin Masonry Vaulting from Spain to America. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians . Vol. 27, No. 3 (Oct., 1968): 176.

28. Spiro Kostof. A History of Architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995: 217.

29. Douglas Harnsberger. In Delorme׳s Manner. In David Yeomans (ed.) The Development of Timber as a Structural Material . Aldershot: Ashgate Variorum, 2005: 249–255.

30. Jefferson׳s Monticello was the first domed building in the America sitting on an octagonal plan.

31. Flat vault was applied to mansions and governmental buildings since the latter half of the 18th century, such as the Ministry of Millitary in Versailles, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. As such, flat vault, once considered a “folk” construction, was also called imperial vault. Turpin C. Bannister. The Roussillon Vault: The Apotheosis of a “Folk” Construction. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians , Vol. 27, No. 3 (Oct., 1968): 163–175.

32. Peter Austin, “Rafael Guastavino׳s Construction Business in the United States: Beginnings and Development,” APT Bulletin , No. 4 (1999): 15–19.

33. Richard Pounds, Daniel Raichel and Martin Weaver. The Unseen World of Guastavino Acoustical Tile Construction: History, Development, Production. APT Bulletin . Vol. 30, No. 4, (1999): 33–39.

34. George R. Collins. The Transfer of Thin Masonry Vaulting from Spain to America. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians . Vol. 27, No. 3 (Oct., 1968): 176–201.

35. Melargano, M. (1991). An Introduction to Shell Structures: The Art and Science of Vaulting . New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

36. In America the timbrel vault fell victim to increasing cost of handwork by masons and wider application of concrete after World War II, and the company was liquidated in 1962. However, in its heyday, its cost was remarkably little, and it was therefore used as a light and inexpensive substitute for voussoir vaulting in institutional, educational, commercial and religious buildings. In countries where hand labor is still not prohibitive the timbrel vault is still used instead of steel or concrete for many purposes. See Janet Parks and Alan G. Neumann. The Old World Builds the New: the Guastavino Company and the technology of the Catalan vault, 1885–1962 . New York: Columbia University Press, 1996.

37. For example, after the disastrous earthquake of 1976 that affected Beijing, no obvious crack was found at the auditorium though the seismic intensity at Tsinghua was classified as between 6 and 7. See Luo Fuwu. Structural System of the Auditorium at Tsinghua University. Jianzhu jishu (Architectural Technology). 2005/7, Vol. 32: 472–473.

38. The Division of Real Estates of Tsinghua University helped set up scaffold surrounding the auditorium, so that we were able to get to the dome from outside and cornice, etc. As such, the measuring can be more accurate.

39. For example, during the sanction against Cuba, Castro hired Spain craftsmen who worked with Gaudi to build a national institutes of fine arts, in which cohesive vault method that did not need steel and concrete was applied for the main building. John A. Loomis. Cuba׳s Forgotten Art Schools . New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1998.

42. Lisa J. Mroszczyk. Rafael Guastavino and the Boston Public Library . Thesis of Dept. Architecture at MIT, 2005: 22.

43. Philip Alexander Bruce. History of the University of Virginia, 1819–1919: The Lengthened Shadow of One Man . New York: MacMillan, 1921: 257–272.

44. Xie Shaoming. Lingnan daxue mading tang yanjiu (A Study of Martin Hall at Lingnan University). Huazhong Architecture . 1988/3: 95–99.

45. Zhou Yichun׳s letter to Murphy on March 1, 1917. Murphy Papers.

46. Miao Rixin. A Historical Survey of Xichun Garden and Tsinghua Garden. Beijing: Tsinghua University Press, 2010.

47. Writing group of history of Tsinghua University. Manuscript of the History of Tsinghua University. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1981:115.

48. J. Cody׳s book on Murphy published in 2001 is the first academic work of this subject, and has henceforth been frequently quoted an referred. However, there is no single entry on Rafael Guastavino and his company, and the part relating to Tsinghua lacks full elaboration. In addition, problems remain when it comes to reading archives.

Document information

Published on 12/05/17

Submitted on 12/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?