Abstract

The research of modern Chinese architectural history formally started in the mid-1980s and the first conference held in 1986 in Beijing marks the establishment of the field. Over the past 26 years, this emerging field has developed fast and steadily. As a result, thirteen biennial conferences have been held since 1986, and academic products of various forms with over ten million characters have been published. This article surveys the development of modern Chinese architectural history as a field of scholarly inquiry in China and outlines some of keystone events in the past 26 years. It also charts out how some key concepts of the field, such as timeline, geography and research approaches have been evolving over time. The article introduces some of the most significant studies in modern Chinese architectural history from the middle 1980s to the present.

Keywords

Modern Chinese architectural history ; Chronology ; Early modern times ; Method

1. Introduction

In the West, modern history or modern era refers to that of the historical period following the Middle Ages, roughly after the sixteenth century. In China, however, unlike that in the West, the term “modern history,” which has often appeared on previous pages, has a different connotation.

It has been widely accepted that Chinas modern times began along with the first Opium War (1840–1842), and ended in 1949 when the Peoples Republic of China was founded. The history before 1949 belongs to “feudal times,” while the period after 1949 up to now is called contemporary history, describing the span of historical events that are immediately relevant to the present time under the Communist regime. As such, Chinese modern times (jindai ) is a specific concept referring to the period between 1840 and 1949 ( Liangyu, 2002 ).

It is now crystal that various projects in Chinese modern times are part of the longer process of modernization to build a strong and wealthy state that is still ongoing nowadays. The term “modern” contains a larger meaning than that before 1949. Therefore, in order to acknowledge this fact and reduce confusion among audience outside China, “early modern times” is used to translate the Chinese expression of jindai in this paper, which deals with the history between 1840 and 1949.

In China, the research on modern Chinese architectural history bracketing the time period 1840–1949 can be generally divided into two stages: the first spanned from the 1940s to the 1970s, and the second that is ongoing at present began in the mid-1980s. After years of preparations, the first symposium on modern Chinese architectural history was held in Beijing in October 1986, which marked the emergence of a new field. It has been 26 years since the first conference of modern Chinese architectural history with considerable achievements. A general review of the origin and development of the emerging field in the past 26 years since 1986 onwards is imperative.

2. Relevant research before the 1980s

In 1944, Liang Sicheng, the founding father of the discipline of Chinese architectural history, finished his landmark book History of Chinese Architecture . In its last chapter, titled “Conclusions—Architecture in the late Qing Dynasty and the Republic,” Liang (2001) gave a concise summary of the recent practice of modern architecture in China. This is an early historical account of modern Chinese architecture.

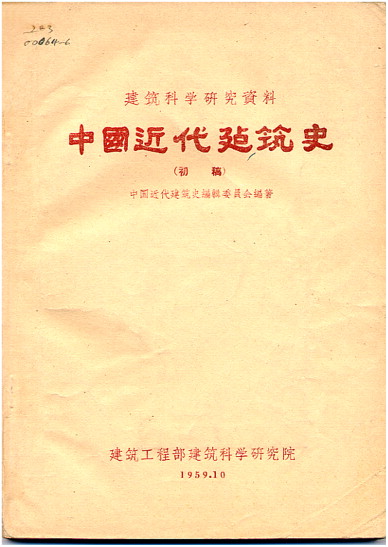

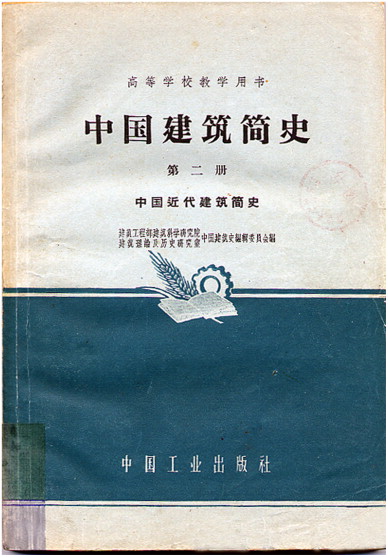

The first formal attempt of comprehensive research on Chinese modern architecture history in China was initiated by the National Institute of Building Science under the Ministry of Construction between October 1958 and October 1961. As a result, a national survey of existing modern architecture was conducted in 1958, and material compilation of “the three history” on architecture after the national “Architectural History Symposium” in October 1958 came to the fruition of The Brief History of Chinese Modern Architecture (first draft) 1 . (Figure 1 ) It was the first textbook on modern Chinese architectural history, though still a rough draft at this time, for higher educational institutions. Compiling this draft mobilized all strength possible and attracted preeminent scholars to work together. Formally-published in 1962 with substantial revisions to the first draft, it set up a solid foundation for succeeding research and had an important place in the field of modern Chinese architectural history. (Figure 2 )

|

|

|

Figure 1. The cover of The Brief History of Chinese Modern Architecture (first draft). |

|

|

|

Figure 2. The cover of The History of Chinese Modern Architecture published in 1962. |

Two years later after the first textbook was published in the mainland, Su Gin-djih, a vigorous architect in the nineteen twenties and thirties, published his book Chinese Architecture—Past and ContemporarySu, 1964 in Hong Kong, who included modern Chinese architectural development since the Republic (1911–1949) in his book. It is an important monograph on the research of modern Chinese architecture published outside the mainland.

In mainland China, however, architectural research was interrupted during Cultural Revolution. It was not until July 1979, the History of Chinese Architecture was published, and was used as the textbook for the course of Chinese architectural history in colleges. The second part, “Modern Chinese Architecture” in this book was basically an abridged version of the 1962 edition of The Brief History of Chinese Modern Architecture , and has been reprinted several times 2 . However, compared to its first draft in 1958, the content was considerably cut down, because the part on modern Chinese architectural history is merely added to the book at the end after elucidation of traditional Chinese architecture as the main part of the book.

The abovementioned accomplishments on the research of modern Chinese architectural history before the 1980s have prepared bedrocks for further development, yet the research before the reform era was sporadic and limited in general. With political and economic restrictions in the 1960s and the 70s, the research on modern Chinese architectural history, like other academic disciplines, generally came to a halt.

3. Establishment of the field and its early years: 1986–93

In the early 1980s, debates on the theories and methodology of historical research sprang up, especially on the study of the cultural exchange between China and the West in jindai period, or early modern times (1840–1949). In the field of architectural history, discussions on the relationship between traditional and modern architectural styles surfaced, involving many scholars in debate. Architectural scholars and historians, both at home and abroad, began to pay more attention to Chinese architectural history in the early modern period that connects the imperial and modern times as the nexus of cultural confrontation between China and the West.

As China opened her door to the outside world, a Japanese PhD student from the School of Engineering at Tokyo University, Muramatsu Shin, came to Tsinghua University in September 1981 to do archival work for his dissertation on the subject of modern Chinese architectural history. Muramatsu stayed at Tsinghua for four years ending in 1984, and went on fieldtrips to many Chinese cities with his colleagues at the Department of Architecture at Tsinghua University. It was a state policy in the early 1980s that foreigners had to be companied when going to other places out of their sojourning city. It was through the fieldtrips and exchange of archive that Chinese scholars were surprised to know the gap of the research on modern Chinese architecture between Japan and China, and realized it was imperative to restart the research in an organized way.

Consequently, in April 1985, Professor Wang Tan and his young assistant, Zhang Fuhe, presented Report on Conducting Research on Chinese Modern History Architecture to the dean of the Department of Architecture at Tsinghua University. The report proposed that “for the development of modern Chinese architecture at present, and for the future of Chinese architecture, it is needed to closely examine the history of modern Chinese architecture and evaluate the value as soon as possible” ( Wang and Zhang, 1985 ).

In August 1985, Tsinghua University organized a small seminar on the research of Chinese modern architectural history Zhang, 1986 , ending with issuing the “Appeal to Immediately Carry on the Protection of Modern Chinese Architecture”. In this sense, this event signaled the research of modern Chinese architectural history in its formal stage. In November 1985, the “International Conference on the Research of Japanese and East Asian Modern Architectural History” was held in the University of Tokyo, which Professor Wang Tan and Mr. Zhang Fuhe were both invited to attend. This marks the beginning of the research of modern Chinese architectural history with cooperation on a global scale3 .

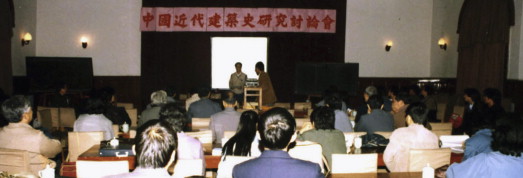

In October 1986, “the Symposium on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History,” the first of its kind, was convened in Beijing, thanks to the organization of Tsinghua University under the leadership of Professor Wang Tan. This was the first nation-wide academic conference on the research of modern Chinese architectural history, which is unanimously regarded as the establishment of the field4 (Figure 3 ).

|

|

|

Figure 3. The first conference held in Beijing in 1986. Professor Wang Tan was on the far background. |

In January 1987, the National Natural Science Foundation and the Ministry of Construction announced to co-fund the project of “the study of modern Chinese architectural history,” which put impetus to initiate the research under financial support from the government.

In October 1986 and May 1987, two professors from the University of Tokyo, Terunobu Fujimori5 and Muramatsu Gackt6 , visited Tsinghua University respectively; in November 1987, the Society of Modern Chinese Architectural History chaired by Wang Tan and the Japanese Academic Society of Modern Asian Architectural History chaired by Terunobu Fujimori had a preliminary agreement on conducting a survey of modern Chinese architecture in a few Chinese cities.

In February 1988, Professor Wang Tan headed a delegation working on modern Chinese architecture to visit Japan, and delivered a speech on modern Chinese architectural history in a meeting sponsored by Japanese Society of Modern Asian Architectural History7 . In this visit, Professors Wang Tan and Terunobu Fujimori signed the “Agreement on Cooperation of the Investigation of Modern Chinese Architecture”. As a result, the Sino-Japanese international cooperation on investigating modern Chinese architecture had full momentum in time.

In May 1988, the Workshop of the Study of Modern Chinese Architecture was held in Tianjin; in April 1989, an experimental survey of important modern buildings took place in Yantai, a treaty port city in Shandong Province8 . Both events were preliminary preparations for the upcoming investigation in fifteen other modern Chinese cities with joint efforts of Chinese and Japanese scholars.

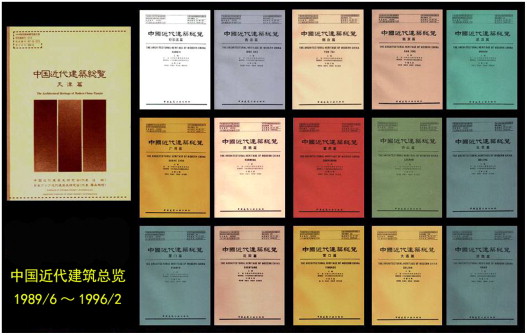

In June 1989, the first book of the Sino-Japanese cooperation project, The Survey of Architectural Heritage of Modern China: Tianjin, was published in Tokyo ( Zuyun et al., 1989 ). It thus marked the early achievements of this four-year project. In October 1991, the survey of modern architecture in 16 Chinese cities were eventually completed, which filled up a total of 2612 tables of on-site investigation with rich records of various forms including original blueprints, survey drawings, photographs, etc. The Sino-Japanese cooperation of investigating modern Chinese architectural history is a success story, and helped promote the knowledge of the field of modern Chinese architectural history in its early and crucial years. By February 1996, the 16 volumes of the Survey of the Architectural Heritage of Modern China were all published 9 . (Figure 4 , also see Appendix 1 )

|

|

|

Figure 4. The covers of the 16 volumes of the Survey of Architectural Heritage of Modern China. |

In April 1988, “the Second Symposium on the Research of Modern Chinese Architectural History” was convened in Wuhan, Hubei10 . Two years later, in October 1990, the third of this kind was held in Dalian, Liaoning11 . When the 1986 symposium was held in Beijing, organizers were not fully confident if there would be following conferences alike for the coming years. However, in less than five years with support both domestically and internationally, the biennial conferences was institutionalized, a sign that the emerging field was developing fast with growing influence.

In between the 2nd and 3rd symposiums, the Ministry of Construction, with the joint effort of the Ministry of Culture, issued the Notice on Major Investigation and Protection of Excellent Modern Architecture on November 10, 1988. This notice spoke of official recognition and evaluation of modern Chinese architecture; henceforth the preservation and reuse of modern Chinese architecture began to gain more attention throughout the country. In March 1991, the Department of Urban Planning of Ministry of Construction, Sate Cultural Relic Bureau, and Architectural Society of China jointly called on a few famous architectural scholars and experts on conservation to attend the Meeting of Appraisal of Fine Modern Chinese Architecture in Beijing, and proposed the List of Excellent Modern Architectures Recommended by Experts as a result 12 .

In October 1992, “the Fourth Symposium on the Research of Modern Chinese Architectural History” was held in Chongqing13 . During the 7 years between 1986 when the field of study was established and 1992, four conferences were held supported by many scholars throughout Chinese colleges and research institutions. These conferences accepted a total of 179 papers, 92 of which were collected in four formally-published proceedings accordingly. The four conferences that were held in four different cities, as well as the progress of the survey of modern Chinese architecture with cooperation of Japanese scholars, became a remarkable sign that the formal stage of the field set off successfully, and made good progress in its early years.

4. Development of the field, 1993–2008

The fifteen years since 1993 witnessed fast development of the field, which bears two characteristics: first, research has been integrated with the broader social and economic development, and has been more and more closely associated with preservation and reutilization; second, academic organization of the field of modern Chinese architectural history has been effectively strengthened, while the scope and scale of research has been largely expanded.

4.1. Integration of research with social concerns and practical preservation

With the advent of the reform era and economic globalization, the preservation of modern Chinese architecture has received more and more attention in concurrence with drastic urbanization in China. For modern Chinese architectural history, it demands that research has to do with social and economic development, and it plays a crucial role in contemporary construction.

Under the circumstances of booming urban construction in China, historical buildings are facing problems such as renovation or demolition. Answers to these problems are closely related to historical research and strategies of preservation in relation to larger urban development. As the crux of the matter consisted in how to evaluate historical buildings, the value of these buildings generally predicts on the means of preservation, or as simple as demolition.

Values of historic buildings consist of two main parts. The first is historical value, and the other practical value, such as whether a building functions well or not. For historic buildings, the assessment of historical value is first and foremost. Because without historical value as background, practical value cannot be recognized in a proper setting. As such, biennial conferences on modern Chinese architecture since 1993 have paid more attention to the issues of preservation and appropriate reuse of modern architecture.

In September 1996, the Fifth Symposium on the Research of Modern Chinese Architectural History was held in Mt. Lu (Lushan). 68 papers were submitted for this conference, of which 13 pieces discussed historic preservation, accounting for 19% of the total amount of submissions14 (Figure 5 ).

|

|

|

Figure 5. Covers of the proceedings of the first five conferences, published as the Proceedings of the Forth Seminar on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History. |

In October 1998, the 1998 International Conference on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History was convened in Taiyuan, the provincial seat of Shanxi. It accepted 72 pieces of papers, 22 of which, or 30% of the total, concerned preservation15 . It is noteworthy that since 1998, “international” was added to the title of the biennial conference showing the growing emphasis on global cooperation on research and other events.

In July 2000, the 2000 International Conference on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History was held in Guangzhou for the first half of sessions, and in Macau for the other half. The major theme of this conference was “Preservation and Reuse of Modern Architecture and Historical District”. This conference accepted 76 papers and 37 papers at the 48% of all discussed the subject of preservation16 .

In August 2002, the 2002 International Conference on Modern Chinese Architectural History was held in Ningbo, Zhejiang province. The major theme was “the Preservation of Modern Architecture and the Development of Modern Chinese City”. 82 pieces of papers were accepted, of which 21 pieces or more than 25% of the total amount of papers concerned preservation17 .

In July 2004, the 2004 International Conference on Modern Chinese Architectural History was held in Kaiping, Guangdong. The major theme was “Watchtower-like Buildings (Diaolou) in Kaiping and the Study on Preservation of Vernacular Architecture in Modern China”. 74 papers were received, and more than 40% (29 papers) of all had to do with preservation (Figure 6 ).

|

|

|

Figure 6. A photo taken on opening ceremony of the 2004 conference. Vernacular architecture became an object of research and one of the major themes in this conference. |

In July 2006, the 2006 International Conference on Modern Chinese Architectural History was convened in Beihai, Guangxi. Its theme was “the Study and Preservation of Early Modern Chinese Architecture and Shophouse Streets”. It accepted 95 papers, of which nearly 25% or 22 essays talked on preservation (Figure 7 ).

|

|

|

Figure 7. Covers of the four proceedings of the biennial conferences during 1998–2004, published as Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture Volume One to Four. |

It is noteworthy that the title of the proceedings of biennial conferences changed into “Research and Preservation of Modern Chinese Architecture” since 2000 that coincided with preservation emerging as a main intellectual inquiry.

As architectural study is closely related to national economy and the peoples livelihood, basic research of engineering subjects, particularly architecture history, should combine practical needs, and research should guide practical planning and construction. If not so, historical research on architecture and urbanism will be confined in “the ivory tower,” hence doomed to be marginalized and declined. Scholars of modern Chinese architectural history, pioneered by Professor Zhang Fuhe when Professor Wang Tan passed away in 2000, have been keenly aware of contemporary construction in China. Research has hence been tied to realities concerning Chinese urban development. That is how the field of modern Chinese architectural history started in 1986 on a weak and limited foundation, but has been able to be developing rapidly in the next two decades.

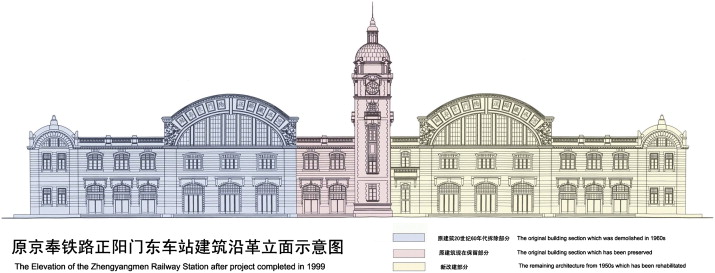

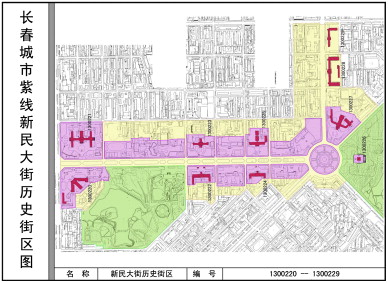

For example, during the 15 years from 1993 to 2008, the team of Tsinghua University under Professor Zhang Fuhes leadership completed several projects of preservation and renovation of modern Chinese architecture, which set a good example for the combination of research and practical work. Typical projects include the reconstruction of “Zhengyangmen Eastern Railway Station” (1993–98)18 , (Figure 8 ) the extension schematic design of Original Beijing Brunch of Japanese Yokohama Specie Bank (1994), the renovation of the original Zhongwei door of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, Ministry of Finance (1998) (Fuhe, 2000) , the rehabilitation of St. Josephs Church at Wangfujing, Beijing and the reconstruction of its gate (2000)19 , the Conservative Planning of Consulate District of Dongjiaominxiang in Beijing (2000)20 , the Conservative Planning of the Central Street in Kuling, Lushan (2001) (Fuhe et al., 2002 ), the reconstruction of original Hu Jin-fang hotel in Lushan (2002), Preservation of Cultural Resources in the Overall Plan of Lushan 2004–20 (2003–04), Research on the Culture and History of Changchun City and Purple Lines Management for the Integral Urban Design (2004–05)21 , (Figure 9 ) the Investigation of Capital Steel Companys Historical and Cultural Resources (2006), the Investigation of Modern Architecture in Anshan City (2006–07),the research and protection of the West Gymnasium in Tsinghua University (2007)22 , amongst others.

|

|

|

Figure 8. Reconstruction of Zhengyangmen Eatsrern Railway Station, now used as National Railway Museum (1998). |

|

|

|

Figure 9. An exemplary table of the Purple Line Designation of Historic Architecture in Changchun (2004). |

In the meantime, Tsinghua has led the path of educating and training both undergraduate and graduate students through research and preservation projects pertaining modern Chinese architecture23 . In 1995, a series of lectures on modern Chinese architectural history was given at the School of Architecture at Tsinghua University, which also introduced research methods and latest practical experience to undergraduate students by scholars like Zhang Fuhe and his colleagues24 . After years of continuous modification of the curriculum, the length of this course, Chinese Modern Architecture History, has been expanded to 32 h in every spring semester, starting from 2001. It is the first course on modern Chinese architectural history in China25 . Due to the accumulation of extensive research and practical experiences on preservation projects throughout China, this course has been warmly applauded by students ever since26 .

4.2. Enhancement of organization and expansion of research field

In August 1998, Architectural Society of China decided to set up the Commission of Specialty of Chinese Modern Architectural History (the name was changed into “Academic Committee of Modern Architecture History” in June 2001) to oversee the research of Chinese modern architecture history, a milestone of the institutional construction of the field to provided reliable guarantee in organization. The operation of the Academic Committee of Modern Architecture History under Architectural Society of China since its establishment has played a positive role in the growth of field, as exemplified in the conscious guidance of research direction.

In October 1998, “the 1998 International Conference on Modern Chinese Architectural History” was convened in Taiyuan. The theme of the conference was “the Comparison between Modern Architecture in the Southeastern China and the Central and Western China”. This conference was the first event organized by the Academic Committee of Modern Architecture History with conscious guidance in deciding themes since its establishment in August 1997.

With advent of the 21st century, research on modern Chinese architecture as well as preservation and renovation of modern buildings has become a critical subject as Chinese government adopted the policy of Great Western Development Strategy. The new policy aimed to promote economic development of western provinces and narrow down regional economic gap to maintain the stability and unity of the country, which responds to the trend and needs of modern Chinese architectural research. It has been proved that the 1998 conference in Taiyuan, a major city in Western China, has cast profound influence on the research and preservation of modern architecture in western China for years to come.

In modern Chinese architectural history, the vast area of central and western region includes 19 provinces that accounted for nearly 90% of Chinas property, and has 2/3 of the total size of population. Therefore, understanding architectural forms and the transformation in modern times in central and western China can be equally, if not more, significant as the research in the Southeast. The comparison of modern Chinese architectural development amongst different regions is indispensable to deepen the research of Chinese modern architecture history. This is the background when the Academic Committee of Modern Architecture History was set up in the late 1990s.

With rapid development of both depth and scope of the field, the cultural connotation of modern architecture demanded further research. Meanwhile, it is widely recognized that the scale of research should not be restricted on single buildings; instead, buildings should be situated in a larger district and urban environment for accurate analysis and the evaluation of its historical value. The diverse and multi-dimensional methods of research will certainly facilitate the expansion of the field and break the path of future research. Therefore, the conference in Kaiping took up the major theme of “Watchtower-like Houses in Kaiping and Preservation of Vernacular Architecture in Modern Chinese Architecture History,” which also resulted from the conscious guidance of research directed by the Committee27 .

Veranda style, or colonial style as called by Chinese scholars in the 1950s, was a major architectural style imported by Westerners since the first Opium War28 . A similar style with veranda buildings is shop house that has also been a subject attracting the attention of many scholars29 . As the field of modern Chinese architecture has been extended to less researched parts of China, the uniqueness of the various representations of veranda style buildings and shophouses on Zhuhai road and Zhongshan road in Beihai, Guangxi province has attracted scholars' attention. In July 2006, the 2006 International Conference on Modern Chinese Architectural History was held in Beihai. The theme of the conference, “the Study and Preservation of Early Modern Architecture and Shophouse Streets,” was also worked out by the Committee and local sponsors.

In July 2008, the 2008 International Conference on Modern Chinese Architectural History took place in Kunming, Yunnan. Its theme was “Regionalism and Internationalism of Modern Chinese Architectural History,” once again an embodiment of the academic guidance under the Committee.

The 2008 conference in Kunming received 125 papers, covering ten different sub-themes. The papers were authored by 221 scholars, professionals, of which 59 were students that accounted for more than 25% of all. The increase of ratio of students demonstrated that the research of modern Chinese architecture has engaged more and more young researchers to participate. If the enhancement of organization and expansion of research field are the hallmark of the field of modern Chinese architectural history in its formal stage, the increasingly active participation of young scholars have input impetus that undergirded the development, which will be the most valued treasure for future development.

5. Recent development since 2008

5.1. Insitutional enhancement and expansion of research in scale and scope

The 2008 conference in Kunming, alongside “the International Conference on Chinese Industrial Architectural Heritage” was co-sponsored by the Committee that was convened in Fuzhou in December 2008, signaling the deepening of the research on modern Chinese architectural history.

The development of the field between 1993 and 2008 has successfully made the first attempt of integrating research with society as exemplified in various preservation projects, and established and enhanced institutional organization for the field. On the other hand, recent development of the field since 2008 bears two identifying marks. First, first it encourages theoretical enquiries, while continues to promote case studies and fieldwork; second, it complements the organization, enhancing the institutional building of the Committee.

In October 1986, modern Chinese architectural history as a new field emerged and the first conference was convened in Tsinghua University. In the following 24 years, biennial conferences were convened in cities including Wuhan, Dalian, Chongqing, Lushan, Taiyuan, Guangzhou-Macao, Ningbo, Kaiping, Beihai and Kunming. In July 2010, the 2010 International Conference on Modern Chinese Architectural History, the twelfth of its kind, was once again held in Tsinghua University in Beijing, which became an important event in the “deepening” stage and marked a milestone of the research of Chinese modern Architecture (Figure 10 ).

|

|

|

Figure 10. A photo taken at the opening ceremony of the 12th biennial conference in Tsinghua. Professor Zhang Fuhe stood at the far background. |

The 2010 conference in Beijing has a significant place in the development of the field. In order to help deepen the research of the field, the 2010 conference took the following measures on institutional buildup.

First of all, the conference adopted the major theme of “Research of Chinese Modern Architecture and Preservation of Modern Architecture” that encouraged historiographical review of the field and its development in the past 25 years. 122 papers were submitted to the conference, of which 88 pieces were collected in the proceedings (that is 69% of the total submission). These 88 papers were authored by 126 persons and covered 9 different sub-themes.

The first sub-theme was “the Research of Modern Architectural History”, aiming to highlight theoretical and historiographical inquiry. Along with the second sub-theme “the Research on the Style Evolution of Modern Architecture”, the two sections contained 22 papers, or 25% of the papers accepted. The high percentage of papers reflected a shift in the research of modern Chinese architecture from investigation on a case-study basis to a theoretical level.

A newly-added sub-theme of “Problems and Strategies of the Preservation of Modern Architecture” included 6 papers, or 6.8% of all papers in the proceedings. Though a minor proportion in the total, this part reflected that researchers have begun to concern about theories and history of preservation beyond a mere description of how modern buildings were preserved technically.

Second, during the past 24 years from October 1986 to July 2010, “the Conference on Modern Chinese Architectural History” has become a regular official conference of Academic Committee of Modern Architecture History every two years, and has been widely recognized as the most authoritative event of the field in China. In order to continue with this tradition, the Beijing conference officially changed the name of the conference from “the 2010 International Conference on Modern Chinese Architectural History” to “the 12th Academic Biennale Conference of Chinese Modern Architecture”. Hence the first of the conferences can be dated back to the 1986 Beijing symposium.

Third, the symbol of “The Academic Biennial Conference of Chinese Modern Architectural History” was decided during the arrangement of “the 12th Academic Biennale Conference of Chinese Modern Architecture”. The composing element of the symbol is the acronym of “The Academic Biennial Conference of Chinese Modern Architectural History” (ABCCMAH), with the background colors of green, purple and grey. (Figure 11 ) “ABC” suggests the status of early development of the field. Although the biennial conferences have been held for thirteen times (as of 2012), the research of Chinese modern architecture is still in its initial stage.

|

|

|

Figure 11. The emblem of the Academic Biennial Conference of Chinese Modern Architectural History, designated in 2010. |

Accordingly, the acronym of the Academic Committee of Chinese Modern Architecture History (ACCMAH) defines the composition of the emblem against the background colors of red, purple and gray (Figure 12 ).

|

|

|

Figure 12. The emblem of the Academic Committee of Chinese Modern Architecture History, designated in 2010. |

Lastly, the series of multi-volume Research and Preservation of Modern Chinese Architecture has been funded and edited by the Academic Committee of Chinese Modern Architectural History since 1998, and was published as the proceedings of “the Academic Biennale Conference of Chinese Modern Architecture” in 2010. The title of The Journal of the 12th Academic Biennial Conference of Chinese Modern Architectural History 2010 was put on the head page of Research and Protection of Chinese Modern Architecture vol. 7.

In July 2012, the thirteenth Academic Biennale Conference of Chinese Modern Architecture was held in two cities on both sides of the Straight, i.e., Xiamen and Jinmen. The organization of conference reflected a broader sense of collaboration on a global level. The University of Tokyo was the earliest international partner that contributed to the establishment and early development of the field of modern Chinese architectural history, and has become a reliable supporter in organizing biennial conferences in the past 26 years. The latest conference, however, has included more partners from other part of the world. For example, the University of California at Berkeley, USA, and Quemoy University, Taiwan, China have become the co-sponsors of the thirteen conference, which reflects the research of modern Chinese architecture has attracted global attention and global cooperation has extended well beyond East Asia (Figure 13 ).

|

|

|

Figure 13. The front page of the Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture (Vol. 8), indicating the collaborative sponsors in China, Japan and the USA. |

The latter half of the thirteenth conference was moved to Jinmen, which was the first time that the biennial conference crossed the Straight. A significant percentage of papers submitted to the conference examined modern Chinese architecture and preservation on the “edge,” i.e., frontier provinces such as Guangxi, Yunnan, and largely overlooked chapter of Taiwan. The trend of broader collaboration and expanding research into less researched area to restore a full picture of the development of modern Chinese architecture will continue into the next conferences30 .

The Journal of the 13th Academic Biennial Conference of Chinese Modern Architectural History (vol. 8), the proceedings of the thirteenth conference, was published in July 2012, before the conference was held. As a result, there have been 755 papers published over the past 26 years as a result of 13 biennial conferences. These papers are the achievements of persistent hard work in the field of modern Chinese architectural history, and have left solid foundation for the further development of modern Chinese architectural research (Figure 14 ).

|

|

|

Figure 14. Covers of the proceedings of the biennial conferences between 2006 and 2012, published as Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture (vol. 5–8). |

However, the further development of the field confronts several problems, both academic and institutional. For example, a monograph of modern Chinese architectural history that incorporates research in the past 26 years should be produced. The problem of giving classes on modern Chinese architectural history with no official reference book can be solved when a textbook as such is published. Also, as China was incorporated in the world system, the emergence and development of modern Chinese architecture should also be studied from a global perspective. For the first move, materials scattered around the world such as missionary archive should be collected and studied carefully. Moreover, the organization of Academic Committee of Chinese Modern Architectural History needs enhancement and completion in organization. Being a subordinate organization of Architectural Society of China, the Committee should enlarge its members and elect vice director, secretary general and other staff to strengthen its position in guiding and promoting the development of the field.

5.2. Rethinking the keywords of the field

After the field has developed for almost three decades, it is crucial to broadly introduce the research of modern Chinese architectural history to audience both in China and abroad, an intriguing task confronting us. As such, it necessary to clarify some of the key concepts based upon the research of the previous decades.

5.2.1. Timeframe: “modern times”

Since the field of modern Chinese architectural history was established in 1986, it is the consensus that the timeframe of the field of study should fall into the period between 1840 and 1949 as well. However, cultural exchange between China and other part of the world has a much longer history. For example, the formation and development of Macau originated in 1535, long before the first Opium War. Besides, the Western-style buildings in royal Yuanmingyuan Garden erected in the mid-18th century and the thirteen foreign companies in canton in the early nineteenth century are a focus of study in modern Chinese architectural history. Hence, research of the field can go beyond 1840 as the upper time limit.

This kind of “overflow” can also be said to the lower time limit. As history is a continuous by nature, historical research can hardly be isolated from its preceding times. Scholars have argued that although Maoist socialism aimed to reorganize Chinese society at large and indeed presented many unique aspects of the new life, the socialist inventions were restricted and diluted by the past. For example, corporation housing was a usual practice in Shanghai, as exemplified in that of Bank of China (Yeh, 1997 ), which heralds work unit or danwei in socialist China. The subtle connections between the colonial past and socialist present and the processes through which the new system came to underpin a new revolutionary “science” of population and economy certainly need more exploration. Colonial relations of power and techniques of urban governance in the past, as post-colonial studies have shown, still linger in the post-colonial period, “which has already had a certain duration (and still continue) in any nation that was involved in imperialism either as the colonizer or the colonized ( Tamanoi, 2008 ).”

Consequently, the general timeframe of modern Chinese architectural studies should not confine research within its parameters. Instead, the proper way of deciding timeframe depends on substantial research projects, and it varies from case to case31 .

5.2.2. Geographical boundary: “Chinese” architecture

Regarding the object of research, in the early years of the field of modern Chinese architectural history, “Chinese” refers to Chinese cities, especially for coastal and riverine cities. For example, the cooperated Sino-Japanese survey was conducted in sixteen cities as such32 . The research of this period mainly focused on Western-style buildings in foreign concessions in treaty port cities, and on Chinese Revival buildings under the aegis of the Kuomintang since the 1920s, both of which are urban-based studies.

Later on, as the scope of research expanded to less urbanized areas, vernacular architecture and buildings built by peasants became objects of study. For example, the 2004 International Conference on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History was held in Kaiping, a village inhabited by relatives of overseas Chinese famous for thousands of watch-tower-like mansions, and the major theme of this conference was study and preservation of this unique kind of modern Chinese architecture. Obviously, definition of “Chinese” architecture in early modern times expanded from coastal cities under remarkable foreign impact to hinterland cities and rural areas.

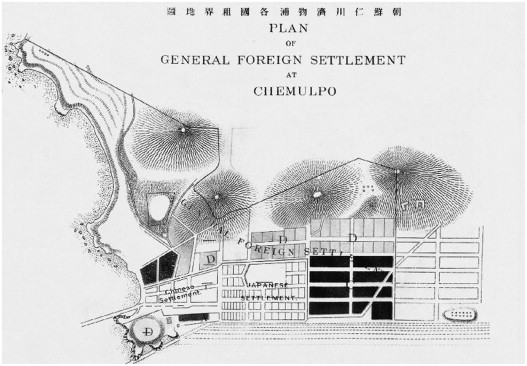

As modern Chinese architecture is a sub-field of Chinese architectural history, the term “Chinese” generally defines the spatial limit of research within Chinese territory including buildings in Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau. However, new materials that have been discovered in recent years help broaden the understanding of modern “Chinese” architecture. For example, shortly following the 1882 military riot, Yu Shikai and his armies took over Korea and a commercial agreement between the Qing and Korea was stipulated33 . Establishment of Chinese Concession in April 1884 signaled the beginning of Chinatown in Incheon (also known as Chemulpo). (Figure 15 ) Like foreign concessions in China, Chinese Concession in Incheon was entitled to extraterritoriality. Following the establishment of Chinese Concession, it began to flourish as the major trading post of the Chinese merchants. In contrast to the negative image of China in the West, such as stagnant, barbarian, and unsanitary (Broudehoux, 2001 ), buildings of Chinese Concession in Incheon were applauded as “modern” and “advanced,” and also an emblem of the achievements of the Self-Strengthening Movement outside China (Lucy Bird, 1898 ). Moreover, a comparison of contemporaneous architectural styles and perceptions in the Chinatown located in Incheon, South Korea and the Chinatown in San Francisco contributes to the understanding of diversity of Chinatown architecture ( Yun, 2010 ).

|

|

|

Figure 15. Map of the Chinese Concession in Incheon, 1884. Source : Incheon Institute of Historical Research. |

Therefore, “Chinese” architecture in early modern times contains object of study on three scales: architecture built within Chinese territory, those built by overseas Chinese in foreign countries, and those built for Diaspora Chinese.

5.2.3. Methodological approach: architectural history

History is about trying to understand the past in a critical way. Architectural history is like other histories in that it is concerned with understanding and finding explanations for the past, but differs in the nature of evidence and methods developed to evaluate that evidence. The built environment can provide an effective analytical perspective to observe history, while material culture and physical construction should be situated in a broader socio-political and historical context, and should be analyzed on a global scale.

Modern Chinese architecture emerged at a time when China was incorporated into a world system dominated by the West, indicating the necessity of taking what happened elsewhere tino account toward a better understanding of all the forces of nature and of man which mold our environment. Early research in the 1980s and 1990s put much emphasis on surveying modern buildings themselves, albeit more descriptive than analytical. Later on, especially after 2000 when younger scholars who earned their doctorates both in and outside China have come to the foreground of the field, research approaches have become increasingly diversified, with collaboration with art historians, sociologists, anthropologists and geographers34 . The subjects of research have been expanded to include architects, architectural technology, colonial architecture, urban history, etc., while research has been more theoretical and comparative in nature than before (Liu, 2012 ). More recently, the historiography of the field has been the subject of several dissertations and articles35 .

Obviously, the research of a special history like modern Chinese architectural history cannot be isolated from other fields of humanities and social sciences. Actually, architecture is a social product and any building is intertwined with society and history that it is embedded. In the recent years, scholars have realized that micro and medium research should be situated in a larger historical context from a longer lens of time for study. With a view of total history that connects various parts of social life and fields of study such as urban history, intellectual history, anthropology, etc., the scope and scale of modern Chinese architectural research can be effectively broadened. As a proponent of interdisciplinarity in research and teaching, scholars of modern Chinese architectural history should also conceive their role as that of a mediator among fields of knowledge production.

6. Concluding remarks

The earliest research on modern Chinese architecture began in the 1940s, first led by Liang Sicheng and then as part of a textbook project of Chinese architectural history in the late 1950s and early 1960s. However, comprehensive research on modern Chinese architectural history as a new field did not emerge until in the mid-1980s. In 1986, due to the accumulation of research in the previous years and the advantage of international exchange with Japanese scholars, the first conference on modern Chinese architectural history was hosted in Tsinghua University, which marked the establishment of the field. Since then, Tsinghua has been the center of organizing various events including biennial conferences amongst other academic activities to promote knowledge on modern Chinese architecture and urbanism. In August 1998, the Academic Committee of Modern Architecture History was formed and Tsinghua was designated as the headquarters of the Committee.

Since 1986, thirteen biennial conferences have been continuously held in cities throughout China, a phenomenon that deserves closer examination in historiography. (Appendices 2 and 3) The popularity of the research on modern Chinese architectural history over the past 26 years has been greatly stimulated, of course, by the tremendous developments that have occurred in the reform period, and it is much needed to explore proper means for preservation and renovation of modern buildings. In the course of the rise of modern Chinese architectural history over the past 26 years, many scholars have gained a strong appreciation for aspects of the built environment in early modern times in China, long overlooked due to the overwhelming scholarly on classic traditional architecture, and political emphasis along a revolutionary paradigm of research. The achievements of the field have been described in detail in previous pages.

To what extent can modern Chinese architectural history contribute to contemporary urban construction and vice versa? At present, the examples of effective cooperation are relatively few. More architects and urban planners, as the statistics of the background of authors in biennial conferences indicates, have looked back into the history of modern Chinese architecture and urbanism to gain knowledge and inspiration, to guide contemporary construction and conservation of historic streets. This is a fine example of the combination of academic research and professional practice. It is however painful to admit that research on modern architecture and relevant preservation projects remain relatively little known outside of China itself.

We believe that there is much more potential for cooperative work in a broader sense that will enrich our understanding of the history of modern Chinese architecture and urbanism and the state of Chinese urbanization today. With a interdisciplinary perspective, and with a global collaboration on research and practice, architectural historians, social scientists, architects and planners can also work together to develop a better understanding of precedents and practices relating to the use and management of the legacies left in the early modern times both in cities and rural areas.

Acknowledgements

Professor Zhang Fuhe of Tsinghua Unversity kindly provided his paper “[T] wenty Years of Modern Chinese Architectural History,” published in the 2006 conference proceedings, and all historical photographs in this paper. Without Professor Zhangs support this paper would not be completed. The author also acknowledges the financial support from the National Post Doctoral Funding.

Appendix 1. The 16 volumes of The Architectural Heritage of Modern China

| Series no. | Volume subtitles | Date of publication | Publisher |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tianjin | June 1989 | The Research Society of Chinese Modern Architecture history, and the research society of Japanese Asia modern architecture history (Tokyo) |

| 2 | Harbin | February 1992 | China Architecture & Building Press (Beijing) |

| 3 | Qingdao | ||

| 4 | Yantai | ||

| 5 | Nanjing | ||

| 6 | Wuhan | ||

| 7 | Guangzhou | ||

| 8 | Kunming | November 1993 | |

| 9 | Chongqing | ||

| 10 | Lushan | ||

| 11 | Beijing | December 1993 | |

| 12 | Xiamen | ||

| 13 | Shenyang | December 1995 | |

| 14 | Yingkou | ||

| 15 | Dalian | ||

| 16 | Jinan | February 1996 |

Appendix 2. The details of the past 13 conferences on modern Chinese Architectural history (1986–2012)

| Conference | Date | Venue | Sponsor(s) | Number of submissions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Symposium of the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History | October 14–16, 1986 | Beijing | Department of Architecture Tsinghua University | 16 |

| 2 | The Second Symposium on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History | April 1988 | Wuhan | Wuhan University & the journal of Huazhong Architecture | 47 |

| 3 | The Third Symposium on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History | October 18–23, 1990 | Dalian | Department of Architecture Dalian University of Technology | 62 |

| 4 | The Forth Symposium on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History | October 5–10, 1992 | Chongqing | Department of Architecture Chongqing Institute of Architecture and Engineering | 54 |

| 5 | The Fifth Symposium on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History | September 2–5, 1996 | Lushan | The Building Branch of Lushan administration | 68 |

| 6 | The 1998 International Conference on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History | October 5–8, 1998 | Taiyuan | Taiyuan City Designing Studying administration & Institute | 72 |

| 7 | The 2000 International Conference on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History | July 24–28, 2000 | Guangzhou &. Macau | Higher Education Architecture Design & Plan institute of Go Pro & Instituto Cultural do Governo da R.A.E. de Macau | 92 |

| 8 | The 2002 International Conference on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History | August 9–12, 2002 | Ningbo | Taizhou Planning Bureau, College of Architecture, Civil Engineering of Ningbo University | 97 |

| 9 | The 2004 International Conference on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History | July 27–30, 2004 | Kaiping | The municipal government of Kaiping | 74 |

| 10 | The 2006 International Conference on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History | July 17–19, 2006 | Beihai | The municipal government of Beihai & Architectural Society of Guangxi | 95 |

| 11 | The 2008 International Conference on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History | Jul 24–26, 2008 | Kunming | Kunming University of Science and Technology | 125 |

| 12 | The 12th Seminar on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History (the 2010 International Conference on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History) | July 13–15, 2010 | Beijing | School of Architecture, Tsinghua University & Chinese Academy of Cultural Heritage | 127 |

| 13 | The 13th Seminar on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History | July 16–21, 2012 | Xiamen &. Jinmen | Huaqiao University, Quemoy University, the University of California at Berkeley (USA) | 112 |

| Total | 1041 | ||||

Note : the School of Architecture at Tsinghua University and the Institute of Industrial technology at the University of Tokyo have been two constant co-sponsors for the past conferences that are not listed above.

Appendix 3. The statistics of papers that appeared on conference proceedings, formally-published as the series of the Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture History (1986–2012)

| Publication titles | Number of papers | Date of publication | Publisher |

|---|---|---|---|

| Huazhong Architecture 1987 no. 2 (Special issue of The Symposium of the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History) | 16 | June 1987 | Huazhong Architecture (Wuhan) |

| Huazhong Architecture 1988 no. 3 (Special issue of the Second Seminar on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History) | 24 | September 1988 | |

| The Proceedings of the Third Seminar on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History | 25 | July 1991 | China Architecture & Building Press (Beijing) |

| The Proceedings of the Forth Seminar on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History | 27 | October 1993 | |

| The Proceedings of the Fifth Seminar on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History | 25 | December 1997 | |

| Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture (vol. 1) | 56 | September 1999 | Tsinghua University Press (Beijing) |

| Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture (vol. 2) | 55 | April 2001 | |

| Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture (vol. 3) | 62 | April 2004 | |

| Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture (vol. 4) | 74 | July 2004 | |

| Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture (vol. 5) | 95 | July 2006 | |

| Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture (vol. 6) | 125 | June 2008 | |

| Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture (vol. 7) (also titled as “The Journal of the 12th Academic Biennial Conference of Chinese Modern Architectural History 2010”) | 88 | July 2010 | |

| Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture (vol. 8) (also titled as “The Journal of the 13th Academic Biennial Conference of Chinese Modern Architectural History 2012”) | 83 | July 2012 | |

| Total | 755 | ||

References

- Broudehoux, 2001 Broudehoux, Anne-Marie, 2001. Learning from Chinatown: the search for a modern Chinese architectural identity. In: Nezar AlSayyad (Ed.), Hybrid Urbanism: On the Identity Discourse and the Built Environment, pp. 156–180.

- Fuhe, 2000 Zhang Fuhe; Renovation of the Gate of the Former Ministry of Finance; Collected Papers of Architectural History, vol. 13, Tsinghua University Press, Beijing (2000)

- Fuhe et al., 2002 Zhang Fuhe, Qian Yi, Ouyang Huailong; Constructive Planning of the Central Street of Kuling in Mt. Lu”; Collected Papers of Architectural History, vol. 16, Tsinghua University Press, Beijing (2002)

- Liang, 2001 Sicheng Liang; The Corpus of Liang Sicheng, 4, China Architecture & Building Press, Beijing (2001), pp. 215–222

- Liangyu, 2002 Li Liangyu; On periodization of modern Chinese history; Fujian Forum (Version of Social Sciences), 1 (2002), pp. 76–83

- Liu, 2012 Yishi Liu; The main thread and periodization of the develpoment of modern Chinese architecture; Architectural Journal, 5 (2012), pp. 70–75

- Lucy Bird, 1898 Isabella Lucy Bird; Korea and Her Neighbors: A Narrative of Travel, with an Account of the Recent Vicissitudes and Present Position of the Country; Revell, New York (1898)

- Su, 1964 Gin-Djin Su; Chinese Architecture—Past and Contemporary; The Sin poh Amalgamated (H.K.) Limited, Hong Kong (1964)

- Tamanoi, 2008 Mariko Asano Tamanoi; Memory Maps: State and Manchuria in Postwar Japan; University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu (2008), p. 3

- Wang and Zhang, April 1, 1985 Wang, Tan, Zhang, Fuhe. Report on starting research on modern Chinese architectural history, unpublished, by courtesy of the author, April 1, 1985.

- Yeh, 1997 Yeh, Wen-hsin. 1997. Republican origins of the Danwei. In: Xiaobo Lu (Ed.). Danwei: The Changing Chinese Workplace in Historical and Comparative Perspective. M.E. Sharpe, London

- Yun, 2010 Yun, Jieheerah, 2010. The tale of the two Chinatowns: seeking Chinese identities abroad, 1880–1940. In: Zhang Fuhe (Ed.), Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture, vol. 7. Tsinghua University Press, Beijing.

- Zhang, 1986 Fuhe Zhang; Synopsis of the symposium of modern Chinese architectural history; New Architecture (1)) (1986)

- Zuyun and Fuhe, 1989 Zhou Zuyun, Zhang Fuhe (Eds.)The Research Society of Chinese Modern Architecture history, and the Research Society of Japanese Asia Modern Architecture History, Tokyo (1989)

Notes

1. The Committee of Compilation of Modern Chinese Architectural History (members including Yang Shenchu, Huang Shuye, Hou Youbin, Lu zuqian, Wang Shiren, and Wang Shaozhou). Modern Chinese Architectural History (First Draft). Beijing: Institute of Compilation and Translation on Architectural Science and Information Press, 1959. This edition was printed for internal circulation but not formally published.

2. Compilation Group of Chinese Architectural History. Chinese Architectural History. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press, 1982 (first edition); 1986 (second edition); 1993 (third edition); 2001 (fourth edition); 2004 (fifth edition).

3. In this event, in addition to Wang Tans speech, other Chinese scholars presented their research, including Zhang Fuhe’s study on Western-style buildings in Yuanmingyuan Garden, Lu Bingjies study on Cathedrals in Shanghai, Wang Shirens study on Modern Chinese architecture in national style. Scholars including Li Qianlang (paper presented on local influence on modern architecture) and Huang Qiuyue (on modernization of cities in Taiwan island) attended the event as well. This was the first meeting where scholars from China, and Japan met up to exchange their research on modern Chinese architecture in a larger context.

4. Huazhong Architecture: 1987(2) (Special issue of The Symposium of the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History). See Appendix 3 .

5. Terunobu Fujimori (

, 1946–~ earned his masters and doctoral degrees in the University of Tokyo, and became a professor at the Institute of Industrial Technology at the University of Tokyo. He published numerous books and articles concerning modern Japanese architecture, architects, and cities. In the 1980s, he was leading the research and survey of modern Japanese architecture, and called on researchers to “go on streets to observe and discover architectural history,” a famous point of view at the time. Since November 1987, Professor Fujimori, on behalf of the Society of Asian Modern Architecture of Japan, started a cooperative project with Chinese scholars to conduct nation-wide survey in Chinese cities. This work lasted four years with tremendous influence. In the first conference in Beijing, Professor Fujimori delivered a speech. See Terunobu Fujimori. A Report of the Research on Modern Japanese Architecture in Japan. World Architecture: 1986(6).

6. Muramatsu Gackt (

, 1924–97) graduated from the University of Tokyo with doctoral degree. He was a professor at the University of Tokyo between 1974–85. Professor Muramatsu pioneered the research of modern Japanese architecture in Japan, and educated many young scholars. After his retirement, his teaching position was replaced by Professor Terunobu Fujimori. In the first conference in Beijing, Professor Muramatsu delivered a speech as well. See Muramatsu Gackt. Methods of Modern Architectural History, and Preservation and Reuse of Modern Architecture. World Architecture: 1987(4).

7. In this event, Chinese scholars presented their research, including Professors Wang Tan, Zhou Zuyun, and Zhangfuhe. See Wang Tan. “On the Research of Modern Chinese Architectural History”. World Architecture: 1988(2); Zhou Zuyun. “A Brief History of Modern Architecture in Tianjin”. In Zhang Fuhe. The Consulate District in Dongjiao Minxiang and Historicism. Architectural Journal, 1987(3).

8. In both events, a group of young Chinese scholars came from universities and design institutes and later became pivotal scholars of the field in doing research for years to come.

9. The 16-volume, The Survey of Architectural Heritage of Modern China has a remarkable imprint on the development of modern Chinese architectural history. It was awarded the second price of Technological Progress of the Ministry of Construction in 1998. The volume on Beijing was awarded the Excellency Price in Social Sciences in Beijing.

10. Huazhong Architecture: 1988(3) (Special issue of the Second Symposium of the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History). See Appendix 3 .

11. The Proceedings of the Third Symposium on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History. See Appendix 3 .

12. A total of 96 projects were put on the list. See Synopsis of the Meeting of Evaluation of Fine Modern Chinese Architecture, July 2, 1991. By courtesy of the author.

13. The Proceedings of the Fourth Symposium on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History. See Appendix 3 .

14. The Proceedings of the Fifth Symposium on the Research of Chinese Modern Architecture History. See Appendix 3 .

15. Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture (vol. 1). See Appendix 3 .

16. Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture, vol. 2. See Appendix 3 .

17. Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture, vol. 3. See Appendix 3 .

18. See Zhang Fuhe and Dong Xiaojing. “Report on the Renovation and Reconstruction of the Railway Station at Gate Zhengyangmen”. Architect: 1992(2), no. 86. See also Study and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture, vol. 1.

19. Collected in Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture, vol. 2. See Appendix 3 .

20. Chen Yue and Zhang Fuhe. “The Formation of the Consulate District in Dongjiao Minxiang and Its Influence”. Collected in Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture, vol. 3. See Appendix 3 . See also Beijing Committee of City Planning. The 25 Historic Districts in Beijing. Yanshan Press, Beijing, 2002.

21. Collected in Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture, vol. 4. See Appendix 3 .

22. Collected in Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture, vol. 6. See Appendix 3 .

23. For example, at the School of Architecture at Tsinghua, masters theses in recent years include pieces as follows. Dong Yugan. “The Planning of Xiangchang District in Beijing - the first attempt of modern planning practice in China, 1914–18” (1996); Dong Xiaojing. “A Preliminary Study of the Preservation and reuse of Modern Railway Stations in China” (1998); Wang Zhiqiang. “Survey and Evaluation of Modern Chinese Architecture in Jilin Province” (2000); Qian Yi. “Preservation and Reuse of Modern Architecture in Kuling at Mt. Lu” (2001); Chen Yue. “The Consulate District in Dongjiao Minxiang in Beijing and Its Architecture” (2002); Feng Tiehong. “A Study of Early Development and Architectural Activities of Kuling at Mt. Lu” (2004); Du Fanding. “A Historical Study of Watchtower-like Buildings in Kaiping” (2005); Liu Yishi. “A Historical Study of the Evolution of Changchun in Modern Times” (2006); Xie Rujun. “A Study on Verandah Style Architecture in Beihai” (2006); Wang Li. “A Historical Study of Modern Architecture in Anshan” (2008); Fang Xue. “Henry Murphy’s Modern Architecture in China and His Influence” (2010).

24. At the beginning a series of lectures were given to students on a basis of two to three hours per semester.

25. For more detail on teaching classes of modern Chinese architectural history in Chinese universities and its curriculum, see Liu Yishi, 2012. Teaching modern chinese architectural history: a review and prospect. New Architecture (6), 4–9.

26. Ibid.

27. Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture, vol. 4. See Appendix 3 .

28. Terunobu Fujimori. Verandah Style Architecture—The Starting Point of Modern Chinese Architectural History. Collected in Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture, vol. 4. See Appendix 3 .

29. There are a total of 19 papers collected in the proceedings over the past 26 years. To name a few, see (1) Xie Xuan and Luo Jianyun. “Spacial Characteristics of Shophouse Architecture in the Old District of Beihai”. Collected in Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture (vol. 5). See Appendix 3 . (2) Lin Chong. “A Discussion of Shophouse in Taiwan”. (3) Xu Zheng. “A Preliminary Study of Six Shophouse Buildings in Quanzhou”; (4) Chen Zhihong. “Shophouse Construction and Municipal Reform in Xiamen”. The three articles are collected in Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture (vol. 3). See Appendix 3 . And Zhang Fuhe, Li Yinan and Fang Xue. “Renovation and Reconstruction of the Façade of Shophouse Street in Yacheng, Sanya”. Collected in Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture (vol. 7). See Appendix 3 . The 2006 conference made the research on early modern Chinese architecture and shophouse as its main theme with 10 papers collected in the proceedings of Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture (vol. 4). The 2012 conference was held in Xiamen and Jinmen, and mansions built by returning overseas Chinese in Fujian was one of the main themes. See Research and Preservation of Chinese Modern Architecture (vol. 8).

30. The Fourteenth Academic Biennial Conference of Chinese Modern Architecture will be held in Guiyang, the seat of Guiyang province in Southwestern China, in 2014.

31. Wang Yeyang, 2000. On the lower limit of modern chinese history and other issues. Tianjin Social Sciences (5); see also Zhang Haipeng, 1998. On the periodization and time limits. Journal of Modern Chinese Historical Studies (2).

32. See Appendix 1.

33. The envoys of Princess Min asked the Qing government for help in the breakout of military riot in 1882 (

).

34. To name a few, see Lai Delin, 2002. From Grand narrative to case study: a review of the research on modern Chinese architecture in the recent 15 years. Architectural Journal, 6, 59–61. Lai Delin and Wang Haoyu (Ed.), 2006. Lives and Works of Chinese Architects in the Modern Times. China Hydraulic and Electricity Press, Beijing. Yishi Liu, 2010. Modern Chinese Archiectural History: the field and its development, vol. 6, pp. 1–5.

35. Besides this paper, scholars at Tsinghua University and their Japanese colleagues who participated in the early stage of the field in the 1980s have produced several other works. See Zhang Fuhe, 2009. Understanding Modern Chinese Architecture. New Architecture 3, pp. 133–135. Li Yinan, 2012. Develpoment of modern Chinese architectural history as a field, Dissertation. Tsinghua Univeristy. Nishizawa Yasuhiko, 2012. The compilation of general surveys of modern archiecture in Japan and China: a methodological note. Architectural Journal 5, pp. 76–78.

Document information

Published on 12/05/17

Submitted on 12/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?