Abstract

The paper deciphers the Chinese literature to English speaking scholars and bridges the gap between China and the western countries on the topics of therapeutic landscapes and healing gardens. Three parts of contents are included in the paper. Firstly, four schools of theories explaining how and why nature can heal, are introduced based on the studies in western countries with the examination of terminology used. In the second part, 71 publications in Chinese are systematically reviewed, with 19 significant studies analyzed in details, including focus areas, the research method, and major findings. In the final part, Chinese studies are evaluated in relation to the theories in western countries.

Keywords

Therapeutic landscapes ; Healing garden ; Literature review ; China ; Western countries

1. Introduction

There have been accumulated research interests on the therapeutic effects of nature since 1970s in western countries. Research evidences have explained how and why natural views and landscape sceneries ease people′s pressure and change their mood from various perspectives, including medical geography (Gesler, 2003 ), environmental psychology (Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989 ; Kaplan, 1992 ; Ulrich, 1984 ; Ulrich, 19991999 ), ecological psychology (Wang and Li, 2012 ; Moore and Cosco, 20102010 ), and horticultural therapy (Detweiler et al ., 2012 ; Söderback et al ., 2004 ). The once disappeared courtyards in hospitals revives in the early 1990s accompanied by the increasing research interest of therapeutic landscapes/healing gardens in the United States. Researches on this topic in western countries have a great impact on China.

Aiming to decipher the Chinese literature to English speaking scholars and bridge the gap between China and the western countries on the topics of therapeutic landscapes and healing gardens, three parts of contents are included in the paper. Firstly, four schools of theories explaining how and why nature can heal are introduced based on the studies from western countries, with the examination of terminology used. In the second part, 71 publications in Chinese are systematically reviewed, with 19 significant studies analyzed in details, including focus areas, the research method, and major findings. In the final part, Chinese studies are evaluated in relation to the theories and studies in western countries.

2. Theories and terminology of therapeutic landscapes and healing gardens in the western countries

There has been a long tradition to view nature as “healer” in different cultures. Garden for the ill first appears in Europe during the Middle ages, with monastic hospitals providing enclosed vegetation gardens with an earnest wish for the spiritual transformation of patients (Gerlach-Spriggs et al., 1998 ). The therapeutic effects of nature to improve patients′ recovery has been, for the first time, precisely written and published by Florence Nightingale in Notes on Nursing in 1860. She believes that visual connections to nature, such as natural scenes through window and bedside flowers, aid the recovery of patients ( Nightingale, 1863 ).

Since the 1970s there have been continuous empirical studies in western countries indicating that natural environments have therapeutic effects. For instance, Olds (1985) examines the therapeutic effects of nature by interviewing focus groups in a coherent workshop for several years, and concludes that places with natural features can heal people′s emotional depression. Francis and Cooper Marcus (1991) conducted similar interviews and found out that people went to natural environment for “self-help” under stressed or depressed conditions. As a result, several schools with different bodies of knowledge emerged, establishing a relationship between landscape and health to explore the healing mechanisms of nature (Table 1 ). In the following text, the author discusses four major schools based on the studies in western societies, including: medical geography, environmental psychological, “salutogenic environment” and the ecological approach, and horticultural therapy.

| School | Terminology | Theories | Representatives | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Medical geography | Therapeutic landscape | Sense of place; four dimensions of therapeutic landscapes: natural environment, built environment, symbolic environment and social environment | Gesler (2003) |

| 2 | Environmental psychology | Restorative environment | Attention-Restoration Theory (ART); four features as restorative environment: being away, extent, fascination, and action and compatibility | Kaplan and Kaplan (1989) ; Kaplan (1992) ; Kaplan and Berman (2010) |

| Therapeutic landscapes and healing garden | Esthetic-Affective Theory (AAT); psycho-evolution theories; three features of healing gardens: relief from physical symptoms, illness or trauma; stress reduction for individuals dealing with emotionally and/or physically stressful experiences; and an improvement in the overall sense of well-being | Cooper-Marcus and Barnes (1999) ; Cooper-Marcus and Sachs (2013) ; Ulrich, 1984 ; Ulrich, 19991999 ; Ulrich, et al. (1991) ; Ulrich and Parsons (1992) . | ||

| 3 | Ecological psychology | Salutogenic environment and therapeutic landscape | Theories of environmental affordances; ecological psychology | Heft (1999, 2010) ; Grahn et al. (2010) ; Grahn and Stigsdotter (2003) . |

| 4 | Horticultural Therapy | Healing garden and therapeutic garden | Theory of “flow experience”; sensory stimulation theories | Söderback et al. (2004) ; Detweiler, et al. (2012) . |

2.1. Medical geography

In view of explaining the healing effects of nature, a significant amount of research come from cultural geography leading to the development of the medical geography school. The concept of “therapeutic landscape” is first introduced by medical geographers, to define places with natural or historic features for the maintenance of health and well being (Velarde et al., 2007 ). The term “therapeutic landscape” has traditionally been used to describe landscapes with “enduring reputation for achieving physical, mental and spiritual healing” (Gesler, 2003 ; Verderber, 1986 ). This term has also been linked to sense of place, leading to four dimensions of therapeutic landscape including: natural environment, built environment, symbolic environment and social environment (Gesler, 2003 ). Branched from environmental psychology, two streams of theories have explained the therapeutic effects of nature with discussions as followed.

2.2. Environmental psychology

2.2.1. Attention-Recreation Theory and the restorative environment

Kaplan and Kaplan starts the research of restorative environment, which describes the types of environments that help people recover from mental fatigue (Kaplan, 1992 ; Vries, 20102010 ). According to their Attention-Restoration Theory (ART), people process surrounding information through two kinds of attention: directed attention and fascination or involuntary attention (Kaplan, 1992 ; Kaplan and Berman, 2010 ). Directed attention is employed in tasks such as problem solving. Directed attention fatigue is a type of temporary symptom of the brains that makes people feel distractible, impatient, forgetful, or cranky, and hence result in a decline of working efficiency (ibid.). Recovery of directed attention is enhanced best in restorative environments where fascination system is used. Additionally, nature encompasses four features as a restorative environment: being away, extent, fascination, and action and compatibility; hence performs well in mental fatigue recovery (ibid.). The following paragraphs introduce another stream of theories in the framework of environmental psychology.

2.2.2. Psycho-evolution theories and healing gardens

Another stream of research reveals that environmental stressors (e.g., crowding, noise) can elicit substantial stress in people, while visual access to nature shows effects on stress recovery (Ulrich et al ., 1991 ; Ulrich and Parsons, 1992 ). Psycho-evolution theories consider that the nature′s therapeutic effect is a matter of unconscious processes and affects located in the oldest, emotion-driven parts of the brain that inform people when to relax (Grahn et al ., 20102010 ; Velarde et al ., 2007 ). Backed up by these theories, a significant quasi-experimental study conducted by Ulrich (1984) concludes that patients get recovered more quickly when looking out of a window with natural scenes. Ulrich (1999) and Cooper-Marcus and Barnes, 1995 ; Cooper-Marcus and Barnes, 1999 refer the term “healing garden” to gardens or landscape settings as “…variety of garden features that have in common a consistent tendency to foster restoration from stress and have other positive influences on patients, visitors, and staff or caregivers”. They also present that a healing garden has either one or a mixture of the three following processes: relief from physical symptoms, illness or trauma; stress reduction and increased levels of comfort for individuals dealing with emotionally and/or physically tiring experiences; and an improvement in the overall sense of well-being (Cooper-Marcus and Barnes, 1999 ). Moving forward, the term “healing garden” has been widely recognized, referring to green outdoor spaces in healthcare facilities that provide a chance of stress relief for patients, staff and families (Eckerling, 1996 ; Gharipour and Zimring, 2005 ; Lau and Yang, 2009 ; Szczygiel and Hewitt, 2000 ).

2.3. Salutogenic environments and the ecological approach

Landscape architects and psychologists also believe that green urban open spaces improve quality of everyday life by providing salubrious environments and perceived visual esthetics to the public. Frederick Law Olmsted, who is internationally renowned as the founder of modern landscape architecture in America, practices dynamically towards healthful environments and landscape designs for the improvement of public health, defined as “salubrious landscape” (Szczygiel and Hewitt, 2000 ). He stated that an environment containing vegetation or other nature “employs the mind without fatigue and yet experiences it… gives the effect of refreshing rest and reinvigoration to the whole (health) system” (Olmsted, 1865 ). Olmsted′s ideas about the healthful, therapeutic nature in cities is still a major influence today on urban park system and community green open spaces (Ulrich and Parson, 1992 ).

Since the 1970s, perceptual psychologists, represented by J.J. Gibson, suggests an environment-behavior model identifying that the environment affords certain behaviors (Kleiber et al ., 2011 ; Greeno, 1994 ). The model no longer considers viewers as receptors of meaningless environmental stimulations; conversely, they emphasize on the dynamic and reciprocal relationship between perceiver and what the environment affords—that is, environmental affordances (Heft, 20102010 ; Gibson, 1979 ). This approach of perceptual research is known as ecological approach. In this framework, researchers believe that environmental affordance in landscape plays a key role in alleviating the so-called lifestyle-related symptoms (e.g., burnt out disease, stress-related pain), by stimulating physical activity, facilitating social contacts and social cohesion among residents (Vries, 2010 ), and encouraging meaningful communications among children and the environment (Moore and Cosco, 2010 ). Theories and applications related to “salutogenic environment” in a manner of ecological psychology have been elaborated in Innovative Approaches to Researching Landscape and Health: Open Space: People Space 2 edited by Thompson, Aspinall and Bell (2010).

2.4. Horticultural therapy school

The horticultural therapy school believes that working in a garden is particularly obvious, meaningful, and enjoyable, hence therapeutic (Stigsdotter and Grahn, 2002 ). Leisure theories back up their research in the way that adults feel rewarded during gardening activities and may go through “flow experiences” with feelings of well-being, total commitment, and forgetfulness of time and self (Czikszentmihalyi, 1990 ). Horticultural therapy scientists usually refer to “healing gardens” or “therapeutic gardens” as settings that provide places for gardening activities and encourage physical movements, such as therapeutic walking (Detweiler et al., 2012 ). In recent decades in the United States, some healing gardens focus on the design of sensory stimulation and accommodation of horticultural activities. This approach has been proven beneficial for the patients with dementia or post-traumatic stress symptoms(Detweiler et al ., 2012 ; Stigsdotter and Grahn, 2002 ).

To broaden the views of research, this paper refers to “therapeutic landscapes” as general public open spaces that improve people′s physical, mental/ spiritual/ emotional, and social well being. Additionally, the term “healing garden” is referred to gardens and natural settings in healthcare facilities that support users′ stress reduction and enhance patients′ recovery. Following the author systematically reviews Chinese literature in realm of therapeutic landscapes/healing gardens. Research topics, research methods and major findings are discussed.

3. Systematic literature review of therapeutic landscapes/healing gardens in China

In view of understanding the current philosophies of therapeutic landscapes/healing gardens in China, this part systematically reviews 71 publications in Chinese language using the search engine of CNKI database—China Knowledge Resource Integrated Database, which records academic publications and outstanding dissertations with English abstract and keywords since 1979. Research methods and results of the literature review are discussed in the following section.

3.1. Keywords and search combinations

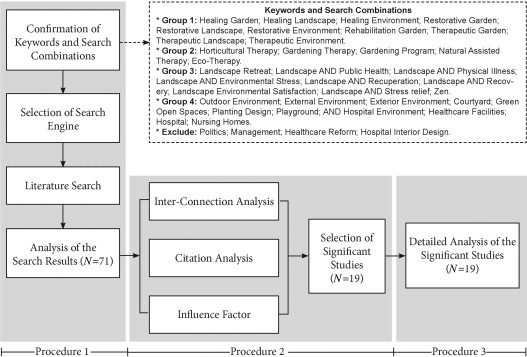

Keywords and search combinations are set up for the literature search after the discussion with experts (shown in Figure 1 ). A systematic review strategy is developed including three procedures: (1) literature search using the keywords and combinations; (2) analysis of the inner connections among the search results, amount of citations and influence factors of the literatures; (3) analysis of the significant studies. 71 Studies written by Chinese scholars are analyzed, including 33 peer-reviewed articles, 2 books and 36 dissertations. The analysis of citations and influences of the 71 research studies are shown in the next section.

|

|

|

Figure 1. Flow chart of systematic literature review. |

3.2. Analysis of 71 studies written by Chinese scholars

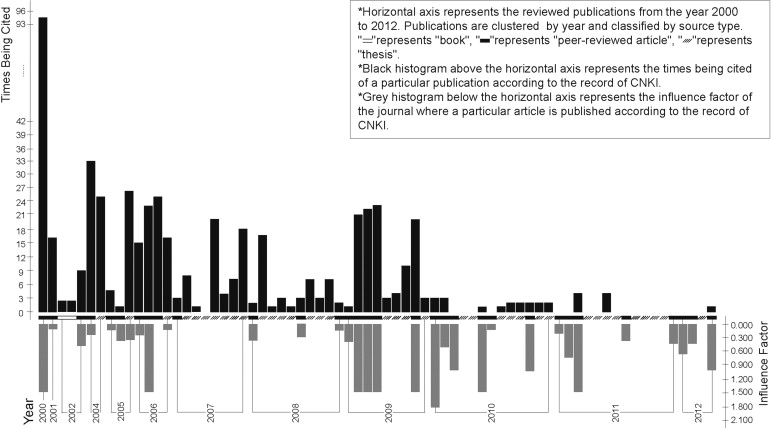

In Figure 2 , horizontal axis represents the reviewed publications from the year 2000 to 2012. Publications are clustered by year and classified by source type. The black histogram above the horizontal axis represents the times being cited of the particular publication according to the record of CNKI. The gray histogram below the horizontal axis represents the influence factor of the journal where the particular article is published according to the record of CNKI.

|

|

|

Figure 2. Analysis of 71 studies written by Chinese scholars. |

This figure shows that intrinsic research interests in realm of therapeutic landscapes starts from the study of horticultural therapy (Li, 2000a ; Li, 2000b ).The application of salubrious plantings in garden design emerges from the understanding of traditional Chinese medicine (Zhao, 2001 ; Chen, 2004 ). In 2009, the most influential Chinese journal in the realm of landscape architecture—Chinese Landscape Architecture —edits a special issue of therapeutic landscapes/healing gardens in which research topics and theories in the western countries are generally introduced to Chinese scholars.

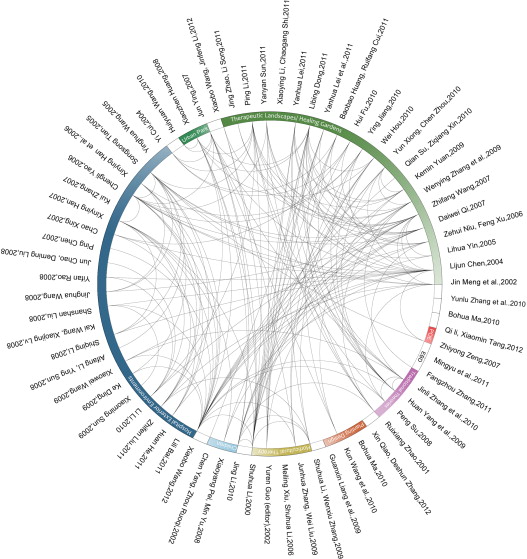

According to Figure 3 , the 71 reviewed studies generally fall into 9 categories of topics, including: general introduction of therapeutic landscapes/healing gardens (22/71); hospital exterior environments (24/71); therapeutic urban parks (3/71); therapeutic environments especially for children (3/71); horticultural therapy (5/71); hospital planting design (4/71); application of traditional Chinese medicine in therapeutic landscapes (5/71); evidence-based design (1/71) and post occupancy evaluation of healing gardens (2/7). Two among the 71 studies are unclassified; an article introduces Zen and Japanese meditation garden (Zhang et al., 2010 ), and a thesis talks about landscape design of post-disaster trauma center on basis of Wenchuan earthquake (Ma, 2010 ). Among all the categories, therapeutic landscapes/healing gardens and hospital exterior environmental study have gained the most research interests. Inter-connections of the 71 studies are illustrated in a circular literature map (shown in Figure 3 ). All the studies are arranged along a circle. Each line represents that the connected two studies are closely related. Connections are identified according to the citation and bibliography in the end of each study. The top 19 studies with the most connections are selected for the further analysis, as discussed in the following section.

|

|

|

Figure 3. Inter-relationship among 71 studies written by Chinese scholars. |

3.3. Detailed analysis of the 19 studies

Among the 19 studies there are 2 empirical studies, and 9 case studies. 13 Sources discuss design recommendations for therapeutic environments informed by the authors′ literature researches but not based on empirical evidences. 7 sources report that healing garden design should combine “Yin” and “Yang” and “five elements” (i.e., metal, wood, water, fire and soil) from the theories of traditional Chinese medicine. 5 studies focus on the appropriate application of medicinal plants in the design of therapeutic landscapes. 1 introduces evidence-based approach as the major research method in this realm, and 1 study talks about the evaluation issue that a grading standard from the professional opinions excluding users′ experience and satisfaction is suggested (shown in Table 2 ).

| No. | Source type | Author(s) and year | Focus area | Research method | Major findings | Design recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Article | Li, 2000a ; Li, 2000b | Horticultural therapy and design of healing gardens for gardening activities | Case study: University of Hyogo (Awaji Campus) Horticultural Therapeutic Garden, Awaji Island, Japan | Three benefits of horticultural therapy: spiritual, social and physical aspects; procedures of horticultural therapy: pre-evaluation, set the therapeutic goal, implementation, key steps of the program, post-program evaluation | China should combine traditional Chinese medicine into its own horticultural therapy program and healing garden design |

| 2 | Article | Zhao, R. (2001) | Nature has therapeutic effects; treatments of traditional Chinese medicine integrated into therapeutic landscape design | Literature research | Treatment using natural resources can heal illness; viewing natural scenes helps to reduce stress | – |

| 3 | Article | Chen, L. (2004) | Therapeutic landscapes and planting design; the application of medicinal plants | Literature research | People-centered design principles based on the public behavior psychology; the application of medicinal plants can heal and improve well-being | Make medicinal plants the fundamental plant in the whole planting community; using a large amount of plants to form visual comfort ability; fitness equipment can be placed near to the medicinal planting community |

| 4 | Master thesis | Cui, Y. (2004) | Hospital exterior environments; related theories and design recommendations | Survey to patients at hospitals in Beijing, Nanjing and Zhengzhou, China Case study of 3 hospitals in USA and 2 hospitals in China | Garden is a key component of hospital healing environment; therapeutic landscape settings help users relief stress, enhance recovery from illness and change mood | Healing gardens should focus on planting design; multi-dimensional design of green open spaces in hospital environment; visual connections from inward to outdoor natural environment is essential to patients |

| 5 | Master thesis | Tian, S. (2005) | Hospital exterior environments; related theories and design recommendations | Case study of multiple hospitals inside and outside China | Five types of hospital exterior open spaces are classified, including: traffic space, gathering space, relaxation space, viewing space and roof garden | Design for different users′ needs. Accessibility, visibility, adaptability for multi-use, esthetic attractiveness, and “borrowed” landscapes for the patients and families; private gardens should be designed for caregivers |

| 6 | Article | Han, X., et al. (2006) | Hospital exterior environment and healing gardens; design recommendations | Case study of multiple hospitals inside and outside China | Employing sustainable garden design strategies; visual connections to healing gardens can facilitate patient recovery | Hospital courtyards should be designed according to users′ needs; Healing gardens should be esthetic, accessible and visible. Proper selection of plants, organized paths, water elements of landscape design, and the selection of art work with positive meanings |

| 7 | Article | Niu, Z. and Xu, F. (2006) | Horticultural therapy and healing gardens; integration of traditional Chinese medical into healing garden design | Literature research | People-centered design principles; landscape design according to “five elements” in traditional Chinese medicine; design using knowledge of environmental psychology | Properly use of different landscape elements, such as water, medicinal plants and sunlight; design of topography and paths to encourage therapeutic exercise. |

| 8 | Article | Xiu, M. and Li, S. (2006) | Influence of horticultural therapy activities on the physical and mental health of the elderly | Quasi-experiment: Self-report and measurement of blood pressure (n =40) residences at Holly Nursing Home, Beijing | Horticultural Therapy program can help the elderly people ameliorate cardio- vascular system degradation, change the mood positively and improve the sense of well-being | – |

| 9 | Master thesis | Yao, C. (2006) | Hospital exterior environments; related theories and design recommendations | Case study of 1 hospital in Beijing, China and 2 hospitals in Shenyang, China | Features of hospital outdoor environment include: privacy, sense of territory, and recognizability. Healing gardens should be designed for various activities and needs of different user groups | Buffer zone near the entrance; interior-exterior visual connections; accessibility to the garden; spatial design encouraging physical activities; high accessibility of the healing garden and barrier-free design. Application of medicinal plants |

| 10 | Master Thesis | Wang, Z. (2007) | Healing garden design; design principles and special needs for children and the elderly patients | Literature research | Healing garden should fulfill various needs of patients, visitors and staff. The garden should be visible and contain diverse spaces. Cold color, quiet environment with fragrance of plants can enhance recovery | Organized traffic and clear spatial layout, plants and water are important design elements; comfortable seats, paths with smooth materials and wide enough for wheels, positive art works; surveillance space near children′s playground |

| 11 | Master thesis | Ying, J. (2007) | Urban therapeutic open spaces for people′s physical and mental health; healing gardens design | Case study: The Elizabeth & Nova Evans Restorative Garden, Cleve- land, OH | Green open spaces are beneficial to the patients′ health outcomes. Healing gardens should be designed according to varied needs of patients, visitors and caregivers | Design different types of spaces for privacy and social communication; a large amount of plants in the garden provides a sense of amenity; the use of medicinal plants assists patients′ recovery according to the “five elements” in traditional Chinese medicine |

| 12 | Article | Li, S. and Zhang, W. (2009) | A review of the methodologies employed in horticultural therapy worldwide; Introduction of horticultural therapy in USA, European countries, Japan and China | Literature research | The research trend in this realm in China: urban green spaces and the public health, plant and its contribution to human well-being through the five sensory stimuli, horticultural activities and its effect to mental and physical symptoms | – |

| 13 | Article | Yang, H., et al. (2009) | Application of traditional Chinese theories in healing garden design. Comparison of design guidelines between China and the West | Case study of a healing garden designed by the author for a professor with minor depression and insomnia | Theories influencing the design of healing gardens include: sense of control, social support, natural distractions, physical movement and exercise. Differences of design guidelines between China and the West: design philosophy, people-nature relationship, concept, and the application of traditional Chinese medicine | Design to keep the balance between body and mind, people and nature, “Yin” and “Yang”; “five elements” and landscape elements should be closely related in design |

| 14 | Article | Zhang, W., et al. (2009) | Nature has therapeutic effects. Evidence-based design as primary methodology of healing garden research and design; common features of healing gardens and design recommendations | Case study: Buehler Enabling Garden, Chicago, MI; William T. Bacon Sensory Garden, Chicago, MI | Primary goal of healing garden is stress relief; features of healing garden include: clarity, access, gathering spaces, private/intimate spaces, people-nature connections. Three approaches through which healing gardens promote people′s well-being: natural environment facilitating physiological process, sensory perception and psychological stimuli and activities for physical fitness | Healing garden design should emphasize sensory environment: green visual scenery, sound of birds and water, aroma from plants to stimulate the sense of smell, design encouraging people to touch plants and water, art works with positive meanings; design should combine horticultural therapy and learn from traditional Chinese medicine |

| 15 | Article | Jiang, Y. (2009) | Introduction to 2 cases of healing gardens in United States | Case study: Healing garden of the Oregon Burn Center at Legacy Emanuel Hospital, Portland, OR; healing garden of Good Samaritan Regional Medical Center, Phoenix, AZ | Design of healing gardens should also focus on special needs for disadvantaged population | – |

| 16 | Article | Zhang, J., et al. (2010) | Introduction of Taoism culture and the application of Taoism theories in healing garden design | Literature research | Well-designed ecological environment can contribute to people′s physical and psychological health. Taoist health preservation culture provides great inspiration to healing garden design | The application of Taoism theories including: a balance of person-nature relation- ship, forms of the space should follow both “stillness” and “movement”, and “Yin” and “Yang”. Selection of medicinal plants based on the “five elements” theory |

| 17 | Article | Lei, Y., et al. (2011) | A brief review of history and current research status of healing garden in western and eastern countries | Case study: Joel Schnaper Memorial Garden, New York, NY; The Elizabeth & Nova Evans Restorative Garden, Cleveland, OH | Four stages of healing garden design: forming stage, rudiment period, silent period, development period; Western country has implemented theories to healing garden design practice, while it is still theoretical research period in China on this topic | Healing garden design should learn from traditional Chinese medicine and design in humanist approaches |

| 18 | Article | Wang, X. and Li, J. (2012) | Intention and extension of the meanings of “therapeutic landscapes” and terminology discrimination | Literature research | Therapeutic landscapes include healing gardens, rehabilitation gardens, meditation gardens and memorial gardens. A healing garden is usually the place where horticultural therapy activities happen | – |

| 19 | Article | Li, Q. and Tang, X. (2012) | Development of quality evaluation index system of healing garden | Post-occupancy evaluation | Qualitative evaluation index system of healing gardens is established by using “level analyzing method” | – |

There are also 2 important translated studies which have great impact to Chinese studies. One is Healing Garden in Hospitals originally written by Cooper-Marcus and translated by Cooper-Marcus et al., 2009 . In this article, a survey to 143 users of 4 hospitals in San Francisco bay area is introduced. It has been stated that gardens in hospitals can reduce users′ stress, enhance patients′ sense of control and then facilitate patients′ recovery. Detailed recommendations of healing garden design are also suggested in the translated article. Another article introducing case studies done by Cooper-Marcus and Barnes (1999) is included in the detailed analysis (Jiang, 2009 ).Comparison of the research philosophies, historical research on therapeutic landscapes/healing gardens, focus areas and methodology is further analyzed in the third part of the paper.

4. Comparison of research status between China and western countries

4.1. Terminology

As Gerlach-Spriggs and Healy (2010) states, “health care gardens are described by a broad and vague collection of overlapping terms …”. Different terms are used from various perspectives in both Chinese and western societies. In western studies, Medical Dictionary defines “therapeutic” as including the “healing powers of nature” ( Hooper, 1839 ). Discussion of terminology issues can be retrieved from the first part of the paper and Table 1 .

In China, Jiang (2009) refers “healing landscape” to “green spaces in healthcare facilities”, and Wang and Li (2012) refer “healing landscape” to landscape which has therapeutic effect on physical and mental health. However, the most commonly used definition by Chinese scholars is “healing garden” described by Eckerling (1996) : healing garden is “…a garden in a healing setting designed to make people feel better” (Lei et al ., 2011 ; Li and Tang, 2012 ). Lei et al. (2011) have classified “healing gardens” into two categories: (1) gardens in healthcare facilities which can improve the recovery process of patients; (2) public parks for people suffering from “life-style depression”. Wang and Li (2012) discriminates the meanings of the terms used in this realm and have stated that healing gardens are usually the places where horticultural therapy activities happen. While therapeutic landscapes consist of various natural settings with therapeutic effects, including healing gardens, rehabilitation gardens, meditation gardens and memorial gardens. Historical researches of therapeutic environments, especially gardens in hospital environments, are comparatively different between China and the west, as discussed in the following paragraph.

4.2. Historical research

One Chinese research briefly reviews the history of therapeutic environment in China (Tian, 2005 ). “BeiTian Yuan”, built around the year 717 A.D., is the first public hospice/hospital in ancient China. Temples located in the remoteness with wild natural surroundings are the places where monks provide treatments and palliative care (ibid.). Between the year1085 A.D. and 1145 A.D., the first public “hospital” is opened to patients where green settings become essential in the form of courtyards. However, no additional research is found on the history and development of therapeutic landscapes/healing gardens.

Comparatively, there are already plenty of studies on history and development of therapeutic landscapes/healing gardens in western countries. A chronologically based historical introduction of healing gardens, from the Medieval, Renaissance, until the 19th century, can be found from Restorative Gardens: The Healing Landscape ( Gerlach-Spriggs et al., 1998 ). Architectural historian Hickman (2013) has systematically studied hospital gardens in England since 1800. In addition, Ziff (2012) narratives the stories behind the landscape design of asylums in Ohio after Civil War in the United States. In the 20th century, Cooper-Marcus and Barnes (1999) clarifies that, from the year 1950 to 1990, the healing garden almost disappeared from hospitals in most western countries because of the influence of the “International Style” and high-rise buildings which dominates hospital designs. Empirical studies since the 1980s have revealed that nature has positive influences on health outcomes, and the 1990s patient-centered care movement triggers the revival of therapeutic landscapes and healing gardens (ibid.). There are also several differences between Chinese studies and the western studies regarding the research focus and theories, discussed in the following paragraphs.

4.3. Research focus and methods

In China, studies on horticultural therapy and the design of facilities accommodating horticultural activities have gained most interest. Topics on hospital exterior environments stably gain interest from the year 2007, and the topic of “healing garden” becomes popular since the year 2010. There had also been a few number of Chinese scholars who talked about therapeutic landscapes/healing gardens for unique user groups, such as children and the elderly people.

Methods used in Chinese studies are mainly literature research and case study; very few of them conduct empirical studies or controlled trails. As mentioned in the first part of the article, the western literature encompasses 40 years′ study on theories and mechanism of the therapeutic effects of nature, some of which have been proven by scientific evidences (Ulrich et al ., 1991 ; Vincent, 2009 ); post-occupancy evaluation is also an effective way to summarize design guidelines (Cooper-Marcus and Barnes, 1999 ). Western studies in this realm are rather highly specialized with topics covering various user groups (i.e., children′s hospital gardens, gardens for the veterans, gardens for the old people, gardens of crisis shelters, etc.), various disease (i.e., gardens for dementia patients, gardens for cancer patients, gardens for visual impaired patients, gardens for mental and behavioral health facilities, and hospice gardens etc.), and various activities (i.e., gardens for rehabilitation, gardens for horticulture therapy and public open spaces with restorative features) (Cooper-Marcus and Barnes, 1999 ; Cooper-Marcus and Sachs, 2013 ). Currently, for the research of healing gardens in western societies, evidence-based approach has become a dominating method. Learnt from evidence-based medicine, design guidelines of healing gardens should be proven by empirical studies; a systematic evaluation of the actual therapeutic effects of the setting may also be included (Cooper-Marcus and Sachs, 2013 ).

4.4. Theories

Theories discussed in the Chinese literature are mainly from the realm of horticultural therapy and traditional Chinese medicine. Among the 19 detailed analyzed studies, 7 studies mention using theories from traditional Chinese medicine in the healing garden design. Planting design with medicinal vegetation is also important in Chinese culture, which can be seen in 5 studies. There have been well established theoretical frameworks in western countries in this realm (see the four major schools of theories discussed in the first part), by contrast, Chinese studies are relatively segmented. There is a significant gap in Chinese literature that theoretically, scholars suggest using traditional Chinese medicine theories in healing garden design. However, when talking about the application of theories, most of the studies learn from western cases and employ design guidelines suggested by western scholars. There is a need to integrate traditional theories from Chinese culture into the western frameworks and work in a multiculturalist approach.

5. Conclusions

To understand the research status in both China and western countries, also to discriminate the terms used in the realm of therapeutic landscapes/healing, terminology has been comparatively examined; research topics, research methods and related theories are also examined. It has been found that in both cultures, the term “therapeutic landscapes” is referred to green public spaces which are beneficial to people′s physical, mental and social health, by providing spaces for therapeutic activities and contemplation, relieving pressures and encouraging social communications. Studies of “healing gardens” in healthcare facilities aim to improve the quality of hospital environment and reduce stress accompanied by the stressful hospitalization experience. Also, the appearance of healing gardens and natural settings in hospitals can enhance the sense of well being for caregivers in such high-pressure work places. Results of the analysis have shown that research of therapeutic landscapes/healing gardens in China are being heavily influenced by horticultural therapy. Meanwhile, Chinese researches focus on the application of medicinal plants and traditional Chinese medicine theories in healing garden design. However, the body of knowledge has not been well formed in Chinese context and empirical tests to the design recommendations are needed in the future.

Acknowledgement

Thanks Deborah Franqui, Ph.D. candidate at Clemson University, for reviewing the draft manuscript.

References

- Chen, 2004 L. Chen; On the construction of healthcare garden; J. Shaoyang Univ. (Natural Science), 1 (4) (2004) (108–109, 114)

- Cooper-Marcus and Barnes, 1995 C. Cooper-Marcus, M. Barnes; Gardens in the Healthcare Facilities: Uses, Therapeutic Benefits, and Design Recommendations; Center for Health Design, Martinez, CA, USA (1995)

- Cooper-Marcus and Barnes, 1999 C. Cooper-Marcus, M. Barnes (Eds.), Healing Gardens: Therapeutic Benefits and Design Recommendations, Wiley, New York, NY, USA (1999)

- Cooper-Marcus and translated by Cooper-Marcus et al., 2009 C. Cooper-Marcus, H. Luo, H. Jin; Healing gardens in hospitals; Chin. Lands. Archit., 7 (2009), pp. 1–6

- Cooper-Marcus and Sachs, 2013 C. Cooper-Marcus, N.A. Sachs; Therapeutic Landscapes: An Evidence-Based Approach to Designing Healing Gardens and Restorative Outdoor Spaces; John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ,USA (2013)

- Cui, 2004 Y. Cui; Research of the Method on Humanistic Medical Environment Design (Master′s dissertation); Southeast University, Nanjing, China (2004)

- Czikszentmihalyi, 1990 M. Czikszentmihalyi; Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience; LidovéNoviny, Paha (1990)

- Detweiler et al., 2012 M.B. Detweiler, T. Sharma, J.G. Detweiler, P.F. Murphy, S. Lane, J. Carman, K.Y. Kim; What is the evidence to support the use of therapeutic gardens for the elderly?; Psychiatry Invest., 9 (2) (2012), pp. 100–110

- Eckerling, 1996 M. Eckerling; Guidelines for designing healing gardens; J. Hortic. Ther., 8 (1996), pp. 21–25

- Francis and Cooper Marcus, 1991 Francis, C., Cooper Marcus, C., 1991. Places people take their problems. In: EDRA Proceedings, vol. 22, pp. 178–184.

- Gesler, 2003 W.M. Gesler; Healing Places; Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, Maryland, USA (2003)

- Gerlach-Spriggs et al., 1998 N. Gerlach-Spriggs, R.E. Kaufman, S.B. Warner; Restorative Gardens: The Healing Landscape; Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, USA (1998)

- Gerlach-Spriggs and Healy (2010) Gerlach-Spriggs, N., Healy, V., The therapeutic garden: a definition, ASLA: Healthcare and Therapeutic Design Newsletter, Spring 2010. Retrieved from http://www.asla.org/ppn/Article.aspx?id=25294

- Gharipour and Zimring, 2005 M. Gharipour, C. Zimring; Design of gardens in healthcare facilities. In WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, vol. 85, WIT Press, WIX Press, Southampton, UK (2005)

- Gibson, 1979 J.J. Gibson; The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Houghton-Mifflin, Boston (1979)

- Grahn and Stigsdotter, 2003 P. Grahn, U.A. Stigsdotter; Landscape planning and stress; Urban Fores. Urban Green., 2 (1) (2003), pp. 1–18

- Grahn et al., 20102010 P. Grahn, C.T. Ivarsson, U.K. Stigsdotter, I.L. Bengtsson; C.W. Thompson, P. Aspinall, S. Bell (Eds.), Innovative Approaches to Researching Landscape and Health: Open Space: People Space, Routledge (2010), p. 2 C.W. Thompson, P. Aspinall, S. Bell (Eds.), Innovative Approaches to Researching Landscape and Health: Open Space: People Space, Routledge, New York, NY, USA (2010), p. 2

- Greeno, 1994 J.G. Greeno; Gibson′s affordances; Psychol. Rev., 101 (2) (1994), pp. 336–342

- Han et al., 2006 X. Han, D. Yu, J. Zhang; Study on the hospital environment planning and design; J. Qingdao Technol. Univ., 5 (2006), p. 013

- Heft, 20102010 H. Heft; Affordances and the perception of landscape: an inquiry into environmental perception and esthetics; C.W. Thompson, P. Aspinall, S. Bell (Eds.), Innovative Approaches to Researching Landscape and Health: Open Space: People Space, 2, Routledge (2010)C.W. Thompson, P. Aspinall, S. Bell (Eds.), Innovative Approaches to Researching Landscape and Health: Open Space: People Space, 2, Routledge, New York (2010)

- Hickman, 2013 C. Hickman; Therapeutic Landscapes: A History of English Hospital Gardens Since 1800; Manchester University Press, Manchester, UK (2013)

- Hooper, 1839 R. Hooper; Medical DictionaryNew York, Harper (1839)

- Jiang, 2009 Y Jiang; Two examples of western medical gardens; Chinese Landscape Architecture, 25 (8) (2009) (16–18)

- Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989 R. Kaplan, S. Kaplan; The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; CUP Archive, Cambridge University Press, New York (1989)

- Kaplan, 1992 S. Kaplan; The restorative environment: nature and human experience; Role of Horticulture in Human Well-being and Social Development: A National Symposium, Timber Press, Portland, OR, USA (1992)

- Kaplan and Berman, 2010 S. Kaplan, M.G. Berman; Directed attention as a common resource for executive functioning and self-regulation; Perspect. Psychol. Sci., 5 (1) (2010), pp. 43–57

- Kleiber et al., 2011 D.A. Kleiber, R.C. Mannell, G.J. Walker; A Social Psychology of Leisure; Venture Pub., Incorporated, State College, PA, USA (2011)

- Lau and Yang, 2009 S.S. Lau, F. Yang; Introducing healing gardens into a compact university campus: design natural space to create healthy and sustainable campuses; Lands. Res., 34 (1) (2009), pp. 55–81

- Lei et al., 2011 Y. Lei, H. Jin, J. Wang; The current status and prospect of healing garden; Chin. Landsc. Archit., 4 (2011), pp. 31–36

- Li and Tang, 2012 Q. Li, X. Tang; Quality evaluation index system of healing gardens; J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. (Agricultural Science), 30 (3) (2012), pp. 58–64

- Li, 2000a S. Li; Call for efforts to establish the horticultural therapy theory and practice with Chinese characteristic in the near future (part one); Chin. Landsc. Archit., 16 (3) (2000), pp. 17–19

- Li, 2000b S. Li; Call for efforts to establish the horticultural therapy theory and practice with Chinese characteristic in the near future (part two); Chin. Landsc. Archit., 16 (4) (2000), pp. 32–34

- Li and Zhang, 2009 S. Li, W. Zhang; Progress in horticultural therapy scientific research; Chin. Landsc. Archit., 25 (8) (2009), pp. 19–23

- Ma, 2010 B. Ma; Research on the Construction of Post-Disaster Trauma Center (Master′s thesis); Shenyang Ligong University, Shenyang, China (2010)

- Moore and Cosco, 20102010 R.C. Moore, N.G. Cosco; Using behavior mapping to investigate healthy outdoor environments for children and families: conceptual framework, procedures and applications; C.W. Thompson, P. Aspinall, S. Bell (Eds.), Innovative Approaches to Researching Landscape and Health: Open Space: People Space, 2, Routledge (2010)C.W. Thompson, P. Aspinall, S. Bell (Eds.), Innovative Approaches to Researching Landscape and Health: Open Space: People Space, 2, Routledge, New York (2010)

- Nightingale, 1863 F. Nightingale; Notes on Nursing; Dover publications, New York (1863)

- Niu and Xu, 2006 Z. Niu, F. Xu; The construction of healthcare garden; Mod. Landsc.Archit., 3 (2006), pp. 24–27

- Olds, 19851985 A.R. Olds; Nature as healer; J. Werser, T. Yeomans (Eds.), Readings in Psychosynthesis: Theory, Process & Practice, The Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (1985)J. Werser, T. Yeomans (Eds.), Readings in Psychosynthesis: Theory, Process & Practice, The Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (1985)

- Olmsted, 1865 Olmsted, F.L., The value and care of parks. Report to the Congress of the State of California. 1865, [Reprinted in R. Nash, Ed. (1976). The Americam Environment. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 8–24].

- Söderback et al., 2004 I. Söderback, M. Söderström, E. Schälander; Horticultural therapy: the “healing garden” and gardening in rehabilitation measures at Danderyd hospital rehabilitation clinic, Sweden; Dev. Neurorehabil., 7 (4) (2004), pp. 245–260

- Stigsdotter and Grahn, 2002 U. Stigsdotter, P. Grahn; What makes a garden a healing garden; J. Ther. Hortic., 13 (2) (2002), pp. 60–69

- Szczygiel and Hewitt, 2000 B. Szczygiel, R. Hewitt; Nineteenth-century medical landscapes: John H. Rauch, Frederick Law Olmsted, and the search for salubrity; Bull. Hist. Med., 74 (4) (2000), pp. 708–734

- Tian, 2005 S. Tian; Research on the Exterior Space Environment Design of Hospital Buildings. (Master′s dissertation); Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China (2005)

- Ulrich, 1984 R.S. Ulrich; View through a window may influence recovery from surgery; Science, 224 (4647) (1984), pp. 420–421

- Ulrich et al., 1991 R.S. Ulrich, R.F. Simons, B.D. Losito, E. Fiorito, M.A. Miles, M. Zelson; Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments; J. Environ. Psychol., 11 (3) (1991), pp. 201–230

- Ulrich and Parsons, 1992 R.S. Ulrich, R. Parsons; Influences of passive experiences with plants on individual well-being and health; The Role of Horticulture in Human Well Being and Social Development (1992), pp. 93–105

- Ulrich, 19991999 R.S. Ulrich; Effects of gardens on health outcomes: theory and research; C.C. Marcus, M. Barnes (Eds.), Healing Gardens: Therapeutic Benefits and Design Recommendations, Wiley (1999)C.C. Marcus, M. Barnes (Eds.), Healing Gardens: Therapeutic Benefits and Design Recommendations, Wiley (1999)

- Velarde et al., 2007 M.D. Velarde, G. Fry, M. Tveit; Health effects of viewing landscapes–landscape types in environmental psychology; Urban For. Urban Green., 6 (4) (2007), pp. 199–212

- Verderber, 1986 S. Verderber; Dimensions of person-window transactions in the hospital environment; Environ. Behav., 18 (4) (1986), pp. 450–466

- Vincent, 2009 E.A. Vincent; Therapeutic Benefits of Nature Images on Health (Doctoral dissertation); Clemson University, Routledge, New York (2009)

- Vries, 20102010 S.D. Vries; Nearby nature and human health: looking at mechanisms and their implications; C.W. Thompson, P. Aspinall, S. Bell (Eds.), Innovative Approaches to Researching Landscape and Health: Open Space: People Space, 2, Routledge (2010)C.W. Thompson, P. Aspinall, S. Bell (Eds.), Innovative Approaches to Researching Landscape and Health: Open Space: People Space, 2, Routledge (2010)

- Wang and Li, 2012 X. Wang, J. Li; Analysis of the healing landscape and its relevant conceptions; J. Beijing Univ. Agric., 27 (2) (2012), pp. 71–73

- Wang, 2007 Z. Wang; Research on Therapeutic Landscapes with Contemporary Hospital Environments (Master thesis); Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China (2007)

- Xiu and Li, 2006 M. Xiu, S. Li; A preliminary study of the influence of horticultural operation activities on the physical and mental health of the elderly; Chin. Lands. Archit., 22 (6) (2006), pp. 46–49

- Yang et al., 2009 H. Yang, B. Liu, P.A. Miller; Traditional Chinese medicine as a framework and guidelines for therapeutic garden design; Chin. Lands. Archit., 7 (4) (2009), pp. 13–18

- Yao, 2006 C. Yao; Environmental design of hospital exterior space (Master′s dissertation); Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, China (2006)

- Ying, 2007 J. Ying; The research of city green space for the human healthy influence of body and mind (Master′s dissertation); Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, China (2007)

- Zhang et al., 2009 W. Zhang, Y. Wu, D. Xiao; Design integrating healing: healing gardens and therapeutic landscapes; Chin. Lands. Archit., 8 (15) (2009), pp. 7–11

- Zhang et al., 2010 J. Zhang, K. Wang, C. Wang; The application of Taoist ecological ethics and health preservation culture to the healing landscape; Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull., 26 (13) (2010), pp. 284–288

- Zhao, 2001 R. Zhao; Application and development of natural landscape in convalescent medicine; Chin. J. Conval. Med., 10 (4) (2001), pp. 1–3

- Ziff, 2012 K. Ziff; Asylum on the Hill: History of a Healing Landscape; Ohio University Press, Athens, OH, USA (2012)

Document information

Published on 12/05/17

Submitted on 12/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?