Summary

Objective

Based on a large series of histopathologically confirmed hepatic angiomyolipomas, we retrospectively studied the typical diagnostic features of hepatic angiomyolipoma and proposed a treatment strategy for this disease.

Materials and methods

From December 1997 to December 2007, 74 consecutive patients who received definitive treatment for hepatic angiomyolipoma, at a single tertiary center, were studied.

Results

There was a marked female predominance (54 females vs. 20 males) and the mean age was 42 years. Forty patients had no symptoms and the tumors were detected incidentally during a medical check-up. From this study, we proposed the typical diagnostic features of hepatic angiomyolipoma to be the absence of risk factors for malignancy, normal tumor marker levels, and typical imaging features on ultrasound (USG), abdominal contrast computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Only 23% of patients could have been diagnosed before surgery using these features. One patient (1.4%) had a malignant angiomyolipoma, and died with distant metastases 14 months after surgery. After a median follow-up of 64 months, there was no recurrence in the other 73 patients.

Conclusion

Patients with typical diagnostic features suggestive of hepatic angiomyolipoma could be observed with regular surveillance. Definitive treatment should be performed when the tumor has symptoms/complications, when the tumor is enlarging, or when a malignant lesion cannot be ruled out.

Keywords

hepatectomy;hepatic angiomyolipoma;imaging;liver neoplasm;pathology

1. Introduction

Angiomyolipoma occurs most commonly in the kidneys. Hepatic angiomyolipoma represents the second most common site of involvement. It is a rare, benign, hepatic mesenchymal neoplasm, first described in 1976 by Ishak.1 Tuberous sclerosis is accompanied by renal angiomyolipoma in about 20% of patients.2 However, most patients with hepatic angiomyolipoma do not have tuberous sclerosis. Most hepatic angiomyolipomas are small and asymptomatic, but they can grow to a large size and thus mimic a malignant tumor. They have an extremely low risk of malignant transformation.3 ; 4

Hepatic angiomyolipoma has three components: smooth muscle cells, adipose tissue, and vessels. These components can vary greatly within the tumor, and between different tumors. The accuracy of preoperative diagnosis is very low as a result of variable imaging appearances, due to the varying proportion of the three components and the rarity of hepatic angiomyolipoma.5; 6; 7 ; 8 The definitive diagnostic study remains the histopathological examination of the surgically resected tumor, coupled with immunohistochemical analysis, specifically with homatropine methylbromide-45 (HMB-45). The smooth muscle cells are the only specific and diagnostic components of hepatic angiomyolipoma and are characteristically immunostained positive for HMB-45 and Melan-A.2; 9 ; 10

With advancements in imaging technology, hepatic angiomyolipoma is being diagnosed with increasing frequency. Overall, hepatic angiomyolipoma is a benign lesion with good prognosis.2; 11; 12; 13 ; 14 If the diagnosis of hepatic angiomyolipoma can be made, conservative treatment with regular surveillance is recommended. Partial hepatectomy is only performed when the tumor has symptoms/complications, when it is enlarging, or when a malignant lesion cannot be ruled out. However, hepatic angiomyolipoma poses a diagnostic challenge clinically, radiographically, and morphologically.

Based on a large series of histopathologically confirmed hepatic angiomyolipomas, the present study aimed to study the typical diagnostic features of hepatic angiomyolipoma and to propose a treatment strategy for this disease.

2. Methods

From December 1997 to December 2007, all patients with hepatic angiomyolipoma who received curative treatment with partial hepatectomy or local ablative therapy at the Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital (Shanghai, China), were studied. The diagnoses were confirmed histopathologically in all patients. Data on clinical features, serology, tumor characteristics, preoperative imaging, and outcome of treatment were collected prospectively and analyzed retrospectively.

2.1. Preoperative evaluation

All patients had a chest X-ray, ultrasonography (USG) of the abdomen, and contrast computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Laboratory blood tests including hepatitis B surface antigen, antibodies to hepatitis C, serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), serum albumin, serum total bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and prothrombin time were obtained, and the Pugh’s modification of Child’s criteria was determined.15 ; 16

2.2. Statistical analysis

Continuous data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (range).

3. Results

From December 1997 to December 2007, 74 consecutive patients with hepatic angiomyolipoma received definitive treatment. Patients and tumor characteristics are shown in Table 1. There was a marked female predominance (54 females vs. 20 males) and the mean age was 42 years with a range of 24–71 years. Forty patients had no symptoms and were detected incidentally at a medical check-up. No patients had tuberous sclerosis and renal angiomyolipoma. Five patients were HBsAg positive. Serum AFP, CEA and CA19-9 were normal in all patients.

| Age (y) | 43.1 ± 10.4 |

| Sex (M:F) (n) | 20:54 |

| HBsAg positive (n) | 5 |

| Anti-HCV positive (n) | 0 |

| Liver cirrhosis (n) | 3 |

| Alcoholism (n) | 7 |

| Presentation (n) | |

| No symptoms | 40 |

| Abdominal pain | 19 |

| Abdominal fullness | 6 |

| Palpable mass | 6 |

| Weight loss | 3 |

| Fever | 0 |

| Preoperative laboratory results | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.5 ± 4.6 |

| Platelet count (109/L) | 186.1 ± 48.3 |

| Bilirubin (μmol/L) | 14.2 ± 5.3 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 40.2 ± 8.3 |

| Tumor markers, median (range) | |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 4 (0.1–8) |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 2 (0–6) |

| CA19-9 (U/mL) | 8 (0–23) |

| Size of tumor (cm) | |

| <5 | 34 |

| 5–10 | 29 |

| 10.1–20 | 5 |

| >20 | 4 |

| Site of tumor (n) | |

| Right hemi-liver | 43 |

| Left hemi-liver | 23 |

| Caudate lobe | 7 |

| Both hemi-livers | 1 |

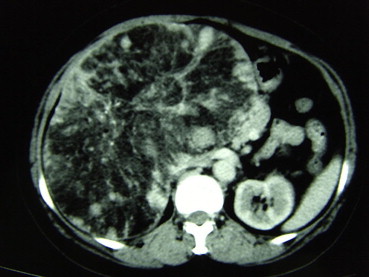

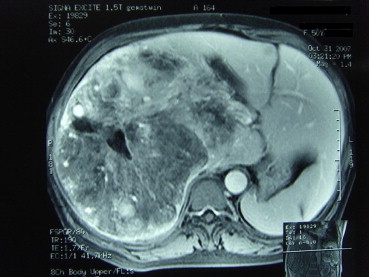

All patients had USG examination. Fifty-eight patients underwent both plain CT and intravenous contrast-enhanced CT examination (Fig. 1) and 35 patients underwent MRI examination (Fig. 2). After we analyzed our data, we were able to suggest the diagnostic features of hepatic angiomyolipoma (Table 2). Unfortunately, using these criteria, only 23% of patients with hepatic angiomyolipoma could be diagnosed before treatment.

|

|

|

Figure 1. CT showing peripheral angiomyomatous component with soft-tissue alternation, a fatty component and prominent central vessels. |

|

|

|

Figure 2. MRI showing peripheral angiomatous component, a fatty component and prominent central vessels. |

| Absence of risk factors of liver malignancy |

| ● No history of malignancy |

| ● Hepatitis B or C negative |

| ● No alcoholism |

| ● No liver cirrhosis |

| Normal tumor markers |

| ● AFP, CEA and CA19-9 |

| Typical imaging features |

| ● USG - a heterogeneously hyperechoic mass |

| ● Plain CT scan - a heterogeneously low density mass with low attenuation value (< −20 HU) |

| ● Contrast-enhanced CT scan - marked enhancement of the soft tissue components in the arterial phase and enhancement in the portal venous phase |

| ● MRI - presence of hypointensity or hyperintensity on T1-weighted imaging and hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging |

Of the 74 patients, partial hepatectomy was carried out in 73 patients and ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation (RFA) after liver biopsy was carried out in one. For the partial hepatectomy patients, 64 patients had Pringle maneuver (mean vascular clamping time, 19.5 ± 6.7 minutes) and 15 patients required intraoperative blood transfusion. The mean ± SD volume of intraoperative blood loss was 392 ± 54 mL. The overall complication rate and hospital mortality rate were 24.8% and 0%, respectively (Table 3). The postoperative hospital stay was 8.5 ± 2.6 days.

| Treatment | |

| Partial hepatectomy | 73 |

| RFA | 1 |

| Type of hepatectomy (n) | |

| Wedge resection | 7 |

| Segmentectomy | 11 |

| Bi-segmentectomy | 21 |

| Right hepatectomy | 17 |

| Left hepatectomy | 9 |

| Left lateral sectionectomy | 8 |

| Complications (n) | |

| Liver failure | 0 |

| Bleeding | 0 |

| Bile leak | 0 |

| Intra-abdominal collection/abscess | 7 |

| Pleural effusion | 10 |

| Procedure related mortality (n) | 17 |

The diagnoses were confirmed histopathologically, with the presence of the specific and diagnostic components of the smooth muscle cells and positivity for HMB-45. Only one female patient (1.4%) was found to have a malignant angiomyolipoma after the operation. The pathological features showed local infiltration and features of malignancy. The surgical margins were clear. Three other patients were found to have mitotic figures in the specimens.

At the time of the census, seven patients (9%) were lost to follow up. The median follow up was 64 months (30–120 months). Only the female patient with malignant angiomyolipoma developed local and distant metastases 6 months after the operation and she died 14 months after the operation. No tumor recurrence or metastasis was found in the other patients during the follow-up period.

4. Discussion

Hepatic angiomyolipomas are rare, and altogether, only approximately 200 cases have been reported in medical literature. To the best of our knowledge, our cohort is the largest reported.

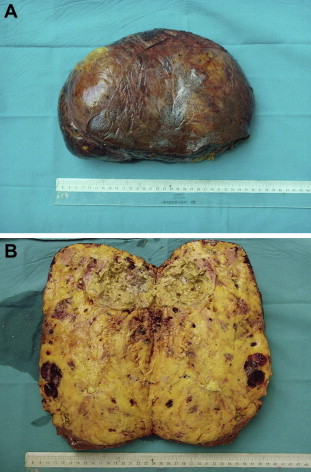

Fat-containing tumors of the liver belong to a heterogeneous group of tumors with characteristic histopathological features, variable tumor behavior, and variable imaging findings. Fat can be present in a variety of benign and malignant liver lesions. The presence of fat can allow a specific diagnosis to be made, or narrow down the list of differential diagnoses of liver lesions. Benign liver lesions that contain fat include steatosis, adenoma, focal nodular hyperplasia, lipoma, angiomyolipoma, cystic teratoma, and hepatic adrenal rest tumor. Malignant liver lesions that can contain fat, include hepatocellular carcinoma, primary and metastatic liposarcoma, and hepatic metastases.5 ; 6 Hepatic angiomyolipoma has three components: smooth muscle cells, adipose tissue, and vessels (Fig. 3). These components can vary greatly within the lesion, or between lesions. The accuracy of preoperative diagnosis is very low, as a result of the variable imaging appearances due to the varying proportion of the three components and the rarity of the tumor. Hepatic angiomyolipoma has usually been misdiagnosed as other fat-containing tumors, particularly hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), as a significant overlap of imaging features happens in more than 50% of patients.17 Hepatic angiomyolipoma poses a real diagnostic challenge.

|

|

|

Figure 3. (A) Hepatic angiomyolipoma. (B) Cut surface showing tumor with adipose tissue, large vessel spaces and solid components of smooth muscle cells. |

Multiple modalities of tests have been used to aid in the diagnosis of hepatic angiomyolipoma. Laboratory tests, such as viral markers for hepatitis, tumor markers, and liver function, have been negative or have not been proven to be specific or helpful in the diagnosis of hepatic angiomyolipoma. Identification of fat within a liver lesion can be critical in characterization of the lesion. Radiographically, hepatic angiomyolipoma has the characteristic imaging features of fatty tissue, yet the diagnosis is only correctly suggested in a minority of cases. Although a combination of USG, CT, MRI is able to increase the accuracy in preoperative diagnosis, hepatic angiomyolipoma usually shows non-typical patterns in imaging studies.7; 8; 9 ; 10 The difficulty in imaging diagnosis occurs because of the wide variation in the proportions of vessels, muscles, and fatty tissue in different tumors. Consequently, hepatic angiomyolipoma is difficult to diagnose on imaging studies alone. USG is currently the first screening method for liver tumors, but USG findings of most liver tumors are nonspecific. As hyperechoic liver nodules cannot be characterized by USG, subsequent examination using CT, MRI, or even fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is necessary.18 CT, and MRI typically demonstrate the fat component and prominent central vessels. At CT scan, hepatic angiomyolipoma has been reported to consist of two parts: a peripheral angiomyomatous component with soft-tissue attenuation and a fatty component with an attenuation value less than –20 HU.5; 6; 7 ; 8 MRI characteristics vary, depending on the proportion of intratumoral fat. Frequently, hepatic angiomyolipoma has a high fat content, with high signal intensity on T1-weighted images and a significant drop in signal intensity on fat-suppressed images.5; 6; 7 ; 8 Diagnosis using FNAC or biopsy is again difficult, because of the heterogeneity of the lesion. The smooth muscle cells are the only specific and diagnostic components of hepatic angiomyolipoma and are characteristically immunostained positive for HMB-45 and Melan-A. This portion of tissue may or may not be sampled. The definitive diagnostic tool remains the histopathologic examination of the surgically resected specimen, coupled with immunohistochemical staining.

Based on our study, only 23% of patients with hepatic angiomyolipoma could have been reliably diagnosed before the operation. A preoperative diagnosis of hepatic angiomyolipoma is difficult and its treatment remains controversial. Hepatic angiomyolipoma is, in general, a benign lesion with a good prognosis. In our series, only 1.4% of patients had a malignant hepatic angiomyolipoma. In a patient without risk factors for liver malignancy (such as chronic hepatitis B or C carrier, liver cirrhosis, previous history of malignancy), with negative serologic tumor markers, and with imaging features suggestive of hepatic angiomyolipoma, conservative treatment with regular surveillance is recommended. Partial hepatectomy should be performed when the tumor has symptoms/complications, when the tumor is enlarging, or when a malignant lesion cannot be ruled out.

References

- 1 K.G. Ishak; Mesenchymal tumors of the liver; K. Okuda, R.L. Peters (Eds.), Hepatocellular Carcinoma, John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY (1976), pp. 247–307

- 2 A.A. Petrolla, W. Xin; Hepatic angiomyolipoma; Arch Pathol Lab Med, 132 (2008), pp. 1679–1682

- 3 T.T. Nguyen, B. Gorman, D. Shields, Z. Goodman; Malignant hepatic angiomyolipoma: report of a case and review of literature; Am J Surg Pathol, 32 (2008), pp. 793–798

- 4 I. Dalle, R. Sciot, R. de Vos, et al.; Malignant angiomyolipoma of the liver: a hitherto unreported variant; Histopathology, 36 (2000), pp. 443–450

- 5 S.R. Prasad, H. Wang, H. Rosas, et al.; Fat-containing lesions of the liver: radiologic-pathologic correlation; Radiographics, 25 (2005), pp. 321–331

- 6 C. Basaran, M. Karcaaltincaba, D. Akata, et al.; Fat-containing lesions of the liver: cross-sectional imaging findings with emphasis on MRI; AJR Am J Roentgenol, 184 (2005), pp. 1103–1110

- 7 S.C. Low, W.C. Peh, M. Muttarak, H.S. Cheung, I.O. Ng; Imaging features of hepatic angiomyolipomas; J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol, 52 (2008), pp. 118–123

- 8 F. Yan, M. Zeng, K. Zhou, et al.; Hepatic angiomyolipoma: various appearances on two-phase contrast scanning of spiral CT; Eur J Radiol, 41 (2002), pp. 12–18

- 9 A. Nonomura, Y. Mizukami, N. Takayanagi, et al.; Immunohistochemical study of hepatic angiomyolipoma; Pathol Int, 46 (1996), pp. 24–32

- 10 W.M. Tsui, R. Colombari, B.C. Portmann, et al.; Hepatic angiomyolipoma: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases and delineation of unusual morphologic variants; Am J Surg Pathol, 23 (1999), pp. 34–48

- 11 C.Y. Yang, M.C. Ho, Y.M. Jeng, R.H. Hu, Y.M. Wu, P.H. Lee; Management of hepatic angiomyolipoma; J Gastrointest Surg, 11 (2007), pp. 452–457

- 12 T. Li, L. Wang, H.H. Yu, et al.; Hepatic angiomyolipoma: a retrospective study of 25 cases; Surg Today, 38 (2008), pp. 529–535

- 13 Y.M. Zhou, B. Li, F. Xu, et al.; Clinical features of hepatic angiomyolipoma; Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int, 7 (2008), pp. 284–287

- 14 L. Xu, Y. Shao, H. Zhang, H. Wang; Hepatic angiomyolipoma: report of 8 cases and review of literature; Asian J Surg, 25 (2002), pp. 82–86

- 15 C.G. Child, J.G. Turcotte; Surgery and portal hypertension; C.G. Child (Ed.), The Liver and Portal Hypertension, Saunders, Philadelphia (1964), pp. 50–64

- 16 R.N. Pugh, I.M. Murray-Lyon, J.L. Dawson, M.C. Pietroni, R. Williams; Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices; Br J Surg, 60 (1973), pp. 646–649

- 17 T.Y. Jeon, S.H. Kim, H.K. Lim, W.J. Lee; Assessment of triple-phase CT findings for the differentiation of fat-deficient hepatic angiomyolipoma from hepatocellular carcinoma in non-cirrhotic liver; Eur J Radiol, 73 (3) (2010), pp. 601–606

- 18 A. Blasco, J. Vargas, P. de Agustín, M. López-Carreira; Solitary angiomyolipoma of the liver. Report of a case with diagnosis by fine needle aspiration biopsy; Acta Cytol, 39 (1995), pp. 813–816

Document information

Published on 26/05/17

Submitted on 26/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?