Abstract

China has achieved economic growth while great carbon emissions reduction in recent years. Amid Chinas effort to reduce emissions, the Five-Year Plans have guided and motivated local and foreign forces from the government, industries, and society to work together. This paper showed that a medium–high economic growth gate, industry structure adjustment, and energy structure adjustment, which are guaranteed under the Five-Year Plan, all contribute to energy saving in China. The economy entered a stable growing phase during the 12th Five-Year Plan, while the economic growth rate declined to 7.8% from 11.2% in the 11th Five-Year Plan. Simultaneously, the CO2 emissions growth rate declined from 8.32% (2009–2012 mean) to 1.82% (2012–2014 mean). Industrial structure adjustment canceled out nearly one-third of the CO2 emissions caused by economic growth. Under the 13th Five-Year Plan, China will continue its energy saving efforts on the green development path, with greener quotas, a stricter implementation process, and more key projects.

Keywords

The Five-Year Plan ; Energy saving emissions reduction ; Governance tool ; Effective evaluation

1. The situation of energy saving and emissions reduction in China

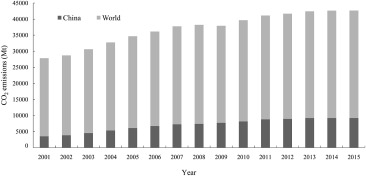

Chinas total carbon emissions has been rising continuously in the past decade and constituted more than 27.5% of the worlds emissions in 2014, exceeding the emissions of the U.S. and the EU and making China the top carbon emitter in the world. This situation is directly linked to Chinas rapid economic development and is also strongly influenced by the worlds transfer of industrial chains. According to Men (2014) , through international trade in 2011, the U.S. made a CO2 net transfer of 760 Mt to China, while the amounts from Japan and the EU were 55 and 640 Mt, respectively. To deal with the situation, China implemented a series of national programs to address climate change, contributing the most towards reducing carbon emissions worldwide while being the largest emitter.

British Petroleum data (BP, 2016 ) indicated that the total global carbon emissions rose from 24,305.2 Mt in 2001 to 33,508.4 Mt in 2015, and that of China rose from 3486.2 Mt to 9153.9 Mt (Fig. 1 ), the carbon emissions data of China from BP is higher than that from National Bureau of Statistics of China. In 2013, Chinas CO2 emissions per unit of GDP were 28.56% lower than that in 2005, which means the emissions reduction was around 2.5 Gt of CO2 .1

|

|

|

Fig. 1. CO2 emissions produced by China and the whole world from 2001 to 2015 (BP, 2016 ). |

The World Bank data (1960–2013)2 showed that CO2 emissions per unit of GDP in China dropped continuously since 2011. Compared with the fact that GDP per capita in China of 2004 was only US$2625.9 (at constant 2005 prices, similarly here after), CO2 emissions per unit of GDP in the U.S. had declined steadily before 1960s, and emissions peaked in 1970 when the GDP per capita in the U.S. was US$2,1183.2. From this perspective, China achieved a Kuznets curve, which indicates that it reduced CO2 emissions per unit of GDP and achieved a preliminary transition of economic growth pattern.

Scholars have analyzed the transition of economic growth pattern, especially energy consumption per unit of GDP and CO2 emissions reduction, from different perspectives. For instance, Guo et al. (2008) explained the change of energy consumption per unit of GDP in China by using the change of primary energy consumption structure, and Peng and Zhu (2011) analyzed the effect of industrial structure on energy consumption per unit of GDP in China. However, these studies applied only a single perspective and failed to conduct an overall study of the mechanism of energy saving and emissions reduction in China from the perspective of national governance tools.

This thesis believes that the Five-Year Plans, as a governance tool, play a vital role in energy saving and emissions reduction in China.

2. The Five-Year Plan in China: a robust governance tool for energy saving

The Five-Year Plan is one of the most significant national policy tools in China. It provides a clear national strategy and intention, and it is vital for propelling the management and implementation of the nation. Constant practice has turned the Five-Year Plan into a unique driver of economic and social development in China. The Five-Year Plan essentially provides a structural guidance for macroeconomic activities and a basis for the government to carry out public service duties. The Five-Year Plan has become a vital tool in national governance and a key guideline for evaluating management performance. The Five-Year Plan has the three following features:

First, it promotes management according to objectives. A long-term goal of five years is set by the central government and distributed to the local governments. Setting such a long-term goal can help guarantee the implementation of policies, perfect the index system of macroeconomic regulation and control that covers vital areas. It can also highlight key points, integrate various efforts, and provide clear directions of development. It especially distinguishes and establishes anticipated and obligatory indices to allow local agencies to define and reach their goals efficiently.

Second, it connects the target accomplishment with local achievement evaluation. The achievement of goals is ensured through supervision, evaluation, assessment, reward, and punishment while implementing goals at the provincial government level. Evaluation results are used as critical evidence during general assessment and evaluation of the leading group and officials of the provincial government. Thus, local governments strengthen their sense of responsibility with the objectives, and the constraint force of the plan is enhanced (Yan et al., 2014 ).

Third, the scenarios of government management and market are considered. The Five-Year Plan motivates both the government and the market; the market plays a decisive role in resource allocation, and the government can operate more effectively. The government and the market are two “hands” of the economy in China, and both must be useful.

3. Influence of the Five-Year Plan on energy saving and emissions reduction of homogeneity research on surface climate data

Chinas energy saving and emissions reduction approach has its own advantage because of the Five-Year Plan. A macro level mechanism is needed to realize energy saving and emissions reduction. This thesis believes that the economic growth rate, industrial structure, and energy structure are the three elements that significantly influence the reduction of energy consumption and carbon emissions intensity per unit.

The central government used the Five-Year Plan to regulate and control the three elements effectively through national goal governance, obligatory index policy, and key projects. During the 11th and 12th Five-Year Plans, China promoted the obligatory index policy of energy saving and emissions reduction by setting obligatory index and key projects in three aspects, namely, economic growth rate, industrial structure, and energy structure, to provide a comprehensive protection mechanism for reducing carbon emissions and thus achieve energy saving and emissions reduction goal.

3.1. Medium-high speed of economic growth rate

Two factors influence the relation between economic growth and carbon emissions: one is energy intensity, which is the amount of energy needed to produce a unit of GDP; the other is the carbon intensity of energy, which is the amount of CO2 emitted to produce a unit of energy. GDP, energy intensity, and carbon intensity of energy determine the amount of carbon emissions. As seen in the historical experience of China, excessively rapid economic development may lead to the fast increase of energy consumption and pollution gas emissions. The 9th and 10th Five-Year Plans are compared as an example. During the 9th Five-Year Plan (1996–2000), the economic growth rate was 8.6%, but the energy consumption growth rate was only 1.1%. Thus, the coefficient elasticity of energy consumption demand growth was 0.127. Data in 2000 showed that the same factors were 17.1% lower than that in the peak year of 1996 and was the same as that in 1993. However, the development pattern changed during the 10th Five-Year Plan; the economic growth rate was 10.2%, which was only 1.6% higher than that in the 9th Five-Year Plan, but the energy consumption and CO2 emissions rose largely, which had a negative effect on the ecological environment. The energy consumption growth rate was as high as 9.4%. As a result, CO2 emissions growth rate was as high as 18.4%.

Medium–high speed of development is a concept contrary to high-speed development. From 1979 to 2011, after the Reform and Opening-up, China experienced an annual economic growth rate of 9.87%, staying in the high-speed development phase. Maintaining such a high development rate is impossible given the changes in both domestic and international economies nowadays. Under such circumstance, a rational choice for current domestic economic development is to maintain the medium–high development rate of around 7.5%.3

The anticipated economic growth rate in the 11th Five-Year Plan was 7.5% and that in the 12th Five-Year Plan was 7.0%. Unlike the planned rate of 7.0% in the 10th Five-Year Plan, the 12th Five-Year Plan indicated a return to the steady phase. Viewed from the practical situation, the economic growth rate was 11.2% and 7.8% in the 11th and 12th Five-Year Plan periods, respectively. A shift from high speed to medium–high speed development creates considerable space for energy consumption growth rate in China. The China Statistical Abstract (NBSC, 2015 ) shows that in the periods of 2001–2008, 2009–2012, and 2012–2014, the growth rate of electricity output decreased continuously from 12.5% to 9.3% and then 8.9%. The growth rate of coal consumption dropped from 10.8% (2001–2008) to 4.4% (2009–2012) and then appeared to have a negative growth of −1.85% (2012–2014). The changes triggered the fall of the growth rate of CO2 emissions; CO2 emissions fell to 9.94% in 2001–2008, 8.32% in 2009–2012, and 1.82% in 2012–2014, which was a significant reduction during the middle and late periods of the 12th Five-Year Plan and showed the preliminary success of energy saving and emissions reduction.

3.2. Adjusting the industry structure

The industry structure and the allocation of and articulation among factors of production in different sectors within a country signal changes in that countrys mode of economic development and affect its ecosystem (Peneder, 2003 ). Li and Zhou (2012) performed grey relational analysis in China on the relationship between the carbon emissions and the industry structure. Their analysis revealed that compared with the primary sector and the service sector, the secondary sector has greater effects on carbon emissions. Developing the service sector in a “low carbon” way and therefore increasing its share will benefit the environment.

Since the Reform and Opening-up in China, industrialization, especially in the heavy industry, has contributed considerably to the increasing carbon emissions, of which the high energy-consuming industry has a large share and the service sector has a relatively small share. For China to pursue green development, the industry structure has to be further adjusted and optimized, with the share of the service sector being increased. In the period of 2010–2013, the industry structure in China has demonstrated noticeable changes. The share of the secondary sector dropped from 56.8% to 48.3% and that of the service sector rose from 39.3% to 46.8%. The coefficient of elasticity of energy declined slightly from 0.58 to 0.48. In this case, as China enters the era of a “New Normal” and processes the expansionary policies that were applied previously, the decline of the coefficient of elasticity of energy due to changes in the industry structure is relatively limited.

The 11th Five-Year Plan targeted that the percentage of its share in the economy of service sector increase by 40.5%, and 43.0% was achieved; the employment rate target in the service sector was 31.3%, and 34.8% was achieved. The 12th Five-Year Plan targeted that the percentage of its share in the economy of service sector increase by 47.0%, and 50.5% was achieved. The 11th Five-Year Plan proposed that optimizing the industry structure and adjusting the economy structure will shift the driving force of economic growth from industrialization, increase the amount of the service sector, and upgrade and optimize the structure. The 12th Five-Year Plan specified that significant progress in adjusting the structure remained one of the seven major targets. Constant optimization and upgrading contributed to and promoted progress in energy saving and emissions reduction, thereby significantly reducing the carbon emissions. The percentage of the secondary sector in the GDP drops to 15.0% from 2013 to 2030, which indicates that the adjustment of the industry structure is the major contributor to the improvement in energy efficiency and carbon emissions reduction. Therefore, energy-intensive industries, including the steel industry, the building material industry, the non-metal mining industry, the chemical industry, and the petrochemical industry, should be restricted. Furthermore, outdated production methods should be phased out to avoid focusing on energy-, carbon emissions-, and capital-intensive industries, and to speed up the development of modern services, especially the information-, knowledge-, and job-intensive services, with the ultimate goal of making modern services the dominant sector in Chinas economy (Hu et al., 2015 ).

3.3. Adjusting the energy structure

The energy structure is closely related to carbon emissions, as illustrated in many academic texts. Schipper et al. (2001) applied Adaptive Weighting Divisia (AWD) index decomposition to analyze the contributory factors for CO2 emissions in 13 IEA countries and found that the strength of energy and the structure of energy consumption are responsible for most changes in the volume carbon emissions. Niu and Wang (2011) conducted a shift-share analysis to study the relationship between the structure of energy consumption and carbon emissions in Heilongjiang province. This proved that the comparatively slow growth of energy consumption and carbon emissions in Heilongjiang, which was slower than the national average, was directly related to the relative advantage in its energy structure. In brief, adjusting the energy structure could somehow lower the amount of carbon emissions.

Unlike the U.S., which uses petroleum as its primary source of energy and where clean energy and sustainable energy make up a relatively large proportion of the energy consumption, China uses coal as its primary source of energy, although the proportion of coal in Chinas energy structure shows an annual declining trend. Moreover, as shown in Table 1 , clean energy and sustainable energy constitute a rather small part of the energy consumption in China. In addition, the emissions per unit energy emit has remained at a high level for quite a time. An increase in the proportion of non-fossil energy consumption is the long-term goal of green development and low-carbon development. The goal is to increase the proportion of non-fossil energy consumption to 11.4% in 2015 and almost 20% in 2020.

| Year | U.S. | China | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coal | Petroleum | Natural gas | Hydropower, nuclear power, wind power (new energy) | Coal | Petroleum | Natural gas | Hydropower, nuclear power, wind power (new energy) | |

| 2000 | 22.9 | 39.0 | 23.4 | 14.7 | 69.2 | 22.2 | 2.2 | 6.4 |

| 2005 | 23.5 | 39.1 | 23.3 | 14.0 | 70.8 | 19.8 | 2.6 | 6.8 |

| 2008 | 22.9 | 39.4 | 24.3 | 13.4 | 70.3 | 18.3 | 3.7 | 7.7 |

| 2009 | 22.8 | 39.4 | 24.4 | 13.3 | 70.4 | 17.9 | 3.9 | 7.8 |

| 2010 | 22.6 | 39.5 | 24.9 | 13.0 | 68.0 | 19.0 | 4.4 | 8.6 |

| 2011 | 22.5 | 39.5 | 25.2 | 12.8 | 68.4 | 18.6 | 5.0 | 8.0 |

| 2012 | 22.4 | 39.6 | 25.4 | 12.7 | 66.6 | 18.8 | 5.2 | 9.4 |

| 2013 | 22.3 | 39.7 | 25.6 | 12.4 | 66.0 | 18.4 | 5.8 | 9.8 |

Source: Hu et al. (2015) .

Energy consumption also needs to decrease. At present, the energy consumption of China is twice that of the world average energy consumption. According to Xie,4 if energy efficiency could be increased by double, then the aggregate economic volume would double without increase in resource or energy.

When the above case is applicable, the energy policy should also be adjusted to increase the percentage of clean energy of high quality and to decrease that of carbon energy in total energy consumption. To be more specific, resource of unconventional natural gas should be further exploited and utilized. By 2020, the volume of natural gas consumption is expected to reach 650 billion m3 or 10%–15% of the total energy consumption in China. By contrast, the percentage of coal consumption is expected a decrease to 60% in 2020 and to below 50% in 2030. By 2030, an energy structure supported by coal, oil, gas, nuclear, and sustainable energy will be preliminarily formed.

The 11th Five-Year Plan targeted the energy consumed per GDP at 20.0%, and 19.1% was achieved. The 12th Five-Year Plan lowered the target to 16.0%, and 18.2% was realized. The 12th Five-Year Plan added the goal of lowering the CO2 emissions per GDP to 17.0%; the actual volume dropped to 20.0%. Aside from setting the obligatory targets, the 11th and 12th Five-Year Plans had also promoted other relevant projects. The 11th Five-Year Plan highlighted 10 important energy saving projects, including transformation of inefficient coal-fired industrial boilers, combination of the production of heat and power within districts, and collection and recycling wasted heat and pressure to reduce power consumption of petroleum and motor systems. Moreover, pilot projects have been launched, including the establishment of focal industry and industrial parks, and the collection and reuse of sustainable energy and metal. The 12th Five-Year Plan proposed four essential energy saving projects, namely, energy saving reconstruction, beneficial products that save energy, demonstration of the industrialization of energy saving techniques, and further implementation of energy management contracts. It also proposed seven essential projects for recycling economy, ranging from comprehensive utilization of resources to the demonstration of the recycling system of worn-out merchandise. In addition, four essential environmental projects were proposed, which include city wastewater treatment and construction of garbage disposal facilities, desulfurization and denitrification, heavy metal pollution prevention and control, and improvement of the water environment in critical river basins. In sum, the proposals of the 11th and 12th Five-Year Plans promote energy saving and emissions reduction projects.

3.4. Different factors' contribution to carbon emissions reduction

According to Hu et al. (2015) , as shown in Table 2 , economic growth generally has a relatively strong positive effect on CO2 emissions in every period. Such effect is especially noticeable during the 9th and the 12th Five-Year Plans as a result of the negative effects of the industry structure, energy consumption, and energy emissions. During the 12th Five-Year Plan, the CO2 emissions contributed by energy emissions per unit dropped considerably compared with that during the 9th Five-Year Plan, thereby proving the great breakthroughs and achievements in energy saving and emissions reduction during the later period. A possible conclusion is that the 12th Five-Year Plan achieved the best results in CO2 emissions reduction, followed by the 9th and the 11th Five-Year Plans (2005–2007). The worst results were achieved during the 10th Five-Year Plan, during which all the four factors had positive effects.

| Period | Economic growth | Industry structure | Energy consumption per GDP | Energy emissions per GDP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8th Five-Year Plan (1991–1995) | 201.2 | 34.7 | −120.7 | −15.2 |

| 9th Five-Year Plan (1996–2000) | 967.4 | −33.5 | −793.2 | −40.7 |

| 10th Five-Year Plan (2001–2005) | 90.0 | 5.0 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| 11th Five-Year Plan (2006–2010) | 149.0 | −0.8 | −35.3 | −12.9 |

| 12th Five-Year Plan (2011–2014) | 532.1 | −57.6 | −177.2 | −197.2 |

Source: Gao and Wang (2007) ; Hu et al. (2015) .

4. The 13th Five-Year Plan and energy saving and emissions reduction

China currently has the second highest cumulative total CO2 emissions among all countries and contributes the largest proportion to global CO2 emissions increase. However, global climate change will potentially create a mechanism of reversal pressure for China in its transitional development stage. When China successfully makes the transition from black development to green development, it will transform from the worlds highest carbon emitter country into a prominent green energy producer, turning its black debt into green contributions. China has a long way to go before such a transition can take place, given its enormous potential in further development and four Five-Year Plans, which cover a total of 20 years (2006–2025). However, it is not impossible for China to go from relative emissions reduction to complete emissions reduction in less time than the U.S. did, disconnect economic growth from carbon emissions, and make a decisive contribution to the process of disconnecting economic growth from carbon emissions on a global scale. The Fifth Plenum of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China applied a comprehensive strategic arrangement and disposition in the 13th Five-Year Plan, which features green development as one of the five key development concepts. Thus, the 13th Five-Year Plan is another brand-new milestone in Chinas green development history. The plan meshes well with Chinas transition from efficiency emissions reduction to aggregate emissions reduction, as seen in the plans goal of reducing unit GDP CO2 emissions by 18%. The plan also presents “improve the overall ecological environment quality” as a core objective for the first time, and the relevant activities include boosting the efficiency of energy resource usage; effectively controlling water consumption, construction space usage, and carbon emissions; significantly decreasing pollution discharge; and forming development priority zones and ecological security barriers. The achievement of such goals will signify Chinas entry into the third stage of ecological environment, and it goes hand in hand with the concept of the Chinese economy running under a sensible framework and making progress in structural adjustment.

First and foremost, the 13th Five-Year Plan points out that China should “maintain a medium–high economic growth,” because when the economic growth rate is between 6.5% and 7.0%, energy consumption growth elasticity, especially that of coal, will demonstrate a downward trend or even negative growth elasticity.

Second, the proportion of the service industry in the GDP is expected to rise, whereas that of traditional industries will fall, thereby marking the entry of post-industrialization and the golden age of service industry, which facilitates the progress of completely disconnecting economic growth from the consumption of major resources and pollution discharge.

In addition, the following actions are recommended: speeding up new energy development, making active innovation a priority instead of passive imitation, integrating the Internet with various industries to breathe new life into the economic environment as a whole and spur green energy revolution, promoting Internet-driven digitization, and green manufacturing revolution, which all serve to advance China into the third stage of its ecological environment.

In general, the 13th Five-Year Plan aims to realize energy saving and emissions reduction with the following working emphases: first, greener plans are made, which involve setting more green quotas; second, using a stricter implementation process with a meticulous appraisal system; and third, setting in motion more key projects and covering more aspects.

4.1. Greener quotas

First, the 13th Five-Year Plan increases the number of green development quotas to 10 (33 in practice), compared with the 11th Five-Year Plan, which has 7 (8 in practice), and the 12th Five-Year Plan, which has 8 (12 in practice). In terms of the proportion of green development quotas to the total of practical quotas for the recent Five-Year Plans, the 11th takes up 34.8%, the 12th raises it to 42.9%, and the 13th raises it again to 48.5%. In terms of binding practical quotas, the 11th has 6, the 12th has 11, and all 16 practical quotas of the 13th Five-Year Plan are binding, which is important in compelling all levels of the government to shoulder their respective environmental protection duties, thereby guaranteeing all green development quotas will be met or even exceeded as scheduled.

Second, the Plan lists 11 priority green development quotas as an important addition, which will become key quotas to meet for special national programs and help guide various departments in their work, especially for comprehensive management departments (National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Finance, etc.) and ecological environment departments (the Ministry of Land and Resources, the Ministry of Environmental Protection, the Ministry of Water Resources, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, the National Energy Commission, the State Forestry Administration, and the State Oceanic Administration).

4.2. Stricter implementation mechanism

The 11th Five-Year Plan established the basic principle of “down play base and verify increment and decrement.” The focus of the 12th Five-Year Plan was the promotion of Six-One emissions reduction project, in which a reliable performance management system is employed with the help of measures such as objective liability statement, daily overseeing, regular verifying, procurement alert, and penal terms to ensure the proper pollution control and emissions reduction responsibility on a local level. The state breaks down all emissions reduction tasks to manageable portions for all levels of government and related enterprises, as well as ensures accountability through strict scrutiny. Since the 11th Five-Year Plan, the environment department has implemented environmental restricted approval on 3 provinces, 9 corporations, and 21 prefecture-level cities. It has also issued executive supervision on 216 enterprises, imposing fines on excess electricity and pollution. The implementation and supervision process of the 13th Five-Year Plan will be stricter.

4.3. More key projects

The 13th Five-Year Plan lists 8 key green development projects, which consist of 39 items. This ecological investment is the largest that China has ever made and is projected to be the largest green investment in the next five years worldwide, doubling the budget of the 12th Five-Year Plan. These projects are fundamental, of overall significance, and are for the public good. Not only are they aimed at the weak links in the construction of Chinas ecological environment, but they are also effective investments with positive driving and spillover effects while integrating material, technological, and labor capital. The impact of these projections of the sustainable development of society, economy and ecology will be profound and lasting. In column 16, five key resource saving and recycling projects, including national energy saving movement, national water saving movement, sparing yet intensive usage of construction space, green mining exemplary region development, and pioneering recycling development, will comprehensively improve the status of Chinas energy and resource consumption.

5. Conclusions

Chinas energy saving and emissions reduction approach has its own advantage because of the Five-Year Plan. Economic growth rate, industrial structure, and energy structure are the three elements that significantly influence the reduction of energy consumption and carbon emissions intensity per unit. The central government use Five-Year Plan to regulate and control the three elements effectively through national goal governance, obligatory index policy, and key projects. This paper showed that a medium–high economic growth gate, industry structure adjustment, and energy structure adjustment, which are guaranteed under the Five-Year Plan, all contribute to energy saving in China.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, the conflict between human and nature in China has become increasingly apparent. Resources and energy, ecology and environment, carbon emissions and climate change have become some of the biggest roadblocks and limiting factors for the development of Chinas economy and society. In the face of these challenges, China has responded positively by constructing a green development concept and a modern five-in-one modern framework (specifically for the construction of an ecological civilization) while setting in motion an unprecedented revolution of green energy, manufacture, consumption, and innovation. After four Five-Year Plans, China has become a pioneer in green development and the biggest green energy country in the world. From 2005 to 2014, the proportion of Chinas hydro generation capacity to the global total increased from 13.6% to 27.4%, the proportion of wind power generation rose from 2.1% to 30.7%, and the proportion of solar power generation rose from 1.3% to 15.6%. These numbers will rise to a new high by 2020.

Chinas vigorous actions in green development have not only benefited the Chinese people, but also the world. For example, with regard to the issue of climate change, thanks to relevant policies of the 12th Five-Year Plan, Chinas annual energy consumption during that period dropped by more than one-third, which is a greater decrease than usual. During the 10th and 11th Five-Year Plans, Chinas carbon emissions annually dropped by 430 Mt, and during the 12th Five-Year Plan, it dropped by another 280 Mt every year. Carbon emissions worldwide in 2014 and 2015 remained the same as in the previous year, and energy intensity and carbon content per energy unit dropped significantly as a result of Chinas indisputable emissions reduction efforts.

In Chinas emissions reduction efforts, the Five-Year Plans have provided guidance and motivation, as well as promoted cooperation between the government and the market, the state and society, the central and the local governments, and local and foreign entities. This synergy has and will continue to lead and guide the world towards further green development and make monumental green contributions to the well-being of humanity.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the “study of Green space management system and protection” of mechanism Economic Development Research Center of State Forestry Administration (ZDWT-2014-3 ).

References

- BP, 2016 BP (British Petroleum); BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2016; (2016) http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.ATM.CO2E.KD.GD?locations=CN

- Gao and Wang, 2007 Z.-Y. Gao, Y. Wang; The decomposition analysis of change of energy consumption for production in China; Stat. Res., 24 (3) (2007), pp. 52–57 (in Chinese)

- Guo et al., 2008 J. Guo, J. Chai, Y.-M. Xi; Primary energy consumption structure changes influence on energy consumption per in China; Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ., 4 (2008), pp. 38–43 (in Chinese)

- Hu et al., 2015 A.-G. Hu, Y.-L. Yan, J.-Y. Zhang, et al.; Report of Contemporary China; Institute for Contemporary China Studies Tsinghua University, Beijing (2015) (in Chinese)

- Li and Zhou, 2012 J. Li, H. Zhou; The analysis of the relations of carbon density and industry structure in China; Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ., 22 (1) (2012), pp. 7–14 (in Chinese)

- Men, 2014 S.-L. Men; Analysis and countermeasures on carbon transfer emissions in Chinas foreign trade; Int. Finance, 2 (2014), pp. 54–58 (in Chinese)

- NBSC, 2015 NBSC (National Bureau of Statistics); China Statistical Digest 2015; China Statistics Press, Beijing (2015)

- Niu and Wang, 2011 X.-G. Niu, H.-L. Wang; The empirical research on the relations between energy consumption structure and carbon emissions in Heilongjiang province; Res. Financial Econ. Issues, 8 (2011), pp. 29–35 (in Chinese)

- Peng and Zhu, 2011 L.-S. Peng, Y. Zhu; The analysis of industry structures influence on the energy consumption per GDP in China; Industrial Sci. Tribune, 10 (5) (2011), pp. 37–39 (in Chinese)

- Peneder, 2003 M. Peneder; Industrial structure and aggregate growth; Struct. Change Econ. Dyn., 4 (4) (2003), pp. 427–448

- Schipper et al., 2001 L. Schipper, M. Scott, K. Marta, et al.; Carbon emissions from manufacturing energy use in 13 IEA countries: long-term trends through 1995; Energy Policy, 29 (2001), pp. 667–688

- Yan et al., 2014 Y.-L. Yan, J. Lü, A.-G. Hu; Integrated knowledge and governance of the commons: understanding the Five Year Plan in the context of market economy; Manag. World, 12 (2014), pp. 70–78 (in Chinese)

Notes

1. http://www.mlr.gov.cn/xwdt/jrxw/201409/t20140902_1328638.htm .

2. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.ATM.CO2E.KD.GD?locations=CN .

3. http://theory.people.com.cn/n/2014/0915/c40531-25659605.html .

Document information

Published on 15/05/17

Submitted on 15/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?