Abstract

Doha, Qatar is continuously positioning itself at the forefront of international urbanism with different qualities of expression in terms of economy, culture, and global outlook, and is characterized by fast-tracked urban development process with large-scale urban interventions in the old center. Although the unprecedented urban growth of this city continues to be a subject of discussion, little attention has been given to investigate the new interventions and the resulting effects they have on the old center. This study aims to examine three important urban interventions, namely, the Museum of Islamic Art, the reconstruction of the traditional market called Souq Waqif, and the Msheireb urban regeneration project. It examines local and global issues, universal standard practices, and traditional knowledge. This study employs a descriptive analysis of these interventions to explore the impact of change in the old center, exemplified by socio-spatial and typo-morphological aspects. Reference is made to a number of empirical studies, including behavioral mapping, GIS population statistics, and analysis of historical maps. Results analytically narrate the reactions of these interventions to the possibility of simultaneously adopting universal practices with local knowledge, and whether prioritizing local influences would represent narrow-mindedness in shaping the city.

Keywords

Doha ; Old center ; Urban intervention ; Change ; Socio-spatial impacts ; Typo-morphological impacts

1. Introduction

Historically, Doha, Qatar was a fishing and pearl diving hamlet. This city has acquired geostrategic importance since the discovery and production of liquefied natural gas in the mid-1990s, in addition to oil production. Today, this capital city is home to more than 90% of the country׳s 1.8 million people, with over 80% comprising professional expatriates from other countries. Doha is portrayed as an important emerging global capital in the Persian Gulf, characterized by fast-tracked urban development processes, the highest global connectivity in this region (Wiedmann et al., 2012 ), and the strong presence of global flows of capital, people, media, education, and oil and gas industries (Salama, 2011a ) (Figure 1 ).

|

|

|

Figure 1. The new skyline of a globalizing Doha. (Source : Authors). |

After Qatar׳s national independence in 1971, the British consultant Llewelyn Davis was appointed by the new town planning authority to design the first master plan of Doha for 1990. His plan was based on a ring concept with a clear definition and a functional distribution of land uses for each ring, which emphasized the old settlement area as the main urban center. In the 1970s, the remaining Qatari neighborhoods were replaced and the indigenous population was relocated to the new suburban developments (Nagy, 2006 ). One main objective of the plan was to establish a modern city center to replace the old one. For this purpose, constructing informal commercial buildings was no longer possible and the last remaining traditional buildings were demolished to provide space for access roads and multistory developments. The Doha׳s prime business and administration center developed in proximity to the old center because of the presence of various office projects in areas adjacent to the latter. However, the historic district was home to a rapidly growing immigrant population in densely built areas. The rapid population growth from 89,000 in 1970 to over 434,000 in 1997 led to the establishment of numerous services outside the old center. Subsequently, new shopping malls in urban peripheries replaced the central retail districts, as the old city center witnessed a gradual deterioration process because of the high concentration of housing for low-income groups (Nagy, 2000 ). The waterfront with main commercial and administrative buildings remained the representative façade. However, the historic city center was exclusively used by low-income groups (Ahmadi, 2008 ). This situation resulted in Doha having no identifiable main center, and existing urban centers were perceived depending on income and cultural backgrounds (Salama, 2011b ).

While the unprecedented urban growth of the city continues to be a subject of discussion, little attention has been given to examine urban interventions in the old city, including the understanding of the resulting impacts these interventions have on the old center. Therefore, this study aims to examine three important urban interventions in the old center, namely, the new Museum of Islamic Art, the reconstruction of the traditional market place called Souq Waqif, and the large-scale Msheireb urban regeneration project (Figure 2 ).

|

|

|

Figure 2. The old center of Doha illustrating the sites of the examined three urban interventions. (Source : Google Earth). |

This study examines local and global issues, universal standard practices, and traditional knowledge. Although the objective is not to compare the three cases, this study employs a descriptive analysis of these interventions to explore the impact of change in the old center, exemplified by socio-spatial and typo-morphological aspects. Reference is made to a number of empirical studies undertaken by the authors, including surveys of city residents, behavioral mapping, GIS population statistics, and analysis of historical maps. This paper concludes with analytical reflections that narrate the reactions of these interventions to the questions of simultaneously addressing local and global issues, adopting universal best practices without ignoring local knowledge, and whether prioritizing local influences would represent narrow-mindedness.

2. Three aspiring levels of urban interventions

Three types of change in the city׳s old center are envisioned. Each type represents a level of urban intervention. They are identified in terms of iconic architectural change , where a building or territory is projected to impose a visual and power statement; remanufacturing urban heritage , where an urban intervention engages local knowledge with its technical and social meanings; and iconic urban change , where an urban regeneration intervention integrates tradition and modernity. The three types represent aspirations that are typically adopted by rulers and government officials who advocate traditional imaging to impress upon the local society their origin and to boast the profile of the capital city while reacting to global conditions (Figure 3 ).

|

|

|

Figure 3. The old center of Doha showing the Msheireb urban intervention dominating the scene, with the Museum and the Souq at the top right corner. (Source : Courtesy and © Msheireb Properties, 2013). |

2.1. Aspiring image making: the museum of Islamic art

Designed by I.M. Pei, the Museum of Islamic Art was inaugurated in 2008. Its 30-hectare site extended the public realm along the Corniche1 , with a park surrounding its two main buildings. The site marks the eastern end of Doha׳s historic settlement and sets an intended juxtaposition with the opposite waterfront development of West Bay and its high-rise cluster. Toward the inland, the museum manifests its connection to the old part of Doha by its immediate position at the end of an urban spine facing the old center (Figure 4 ). Its exposed location has made it visible from various directions, which has led to a certain visual reconnection between the old center and the waterfront. The design aspiration was to present a new image of the city while evoking a new interpretation of the regional heritage (Salama, 2011a ). The intervention embraces two cream-colored limestone buildings, a five-story main building, and a two-story Education Wing, all connected across a central courtyard. The main building׳s angular volumes step back as they rise to an approximately five-story high domed atrium. An oculus at the top of the atrium captures and reflects patterned light within the faceted dome. The museum park offers a green urban context with a site-specific public artwork titled “7” by internationally acclaimed American artist Richard Serra (Al Khemir and Jodidio, 2009 ). Featuring 3 km of lit pedestrian pathways shaded by native palm trees, the park offers cultural, educational, and recreational programs for people of different age groups and cultural and socio-economic backgrounds. Year-round public activities include film screenings, sports events, storytelling programs, and art workshops.

|

|

|

Figure 4. Generated behavioral maps based on observation periods at Souq Waqif. (Source : Authors, 2013). |

2.2. Aspiring positioning of traditional knowledge: the Souq Waqif market place

The reconstruction of Souq Waqif represents another manifested aspiration of revitalizing the past of a country. The literal translation of the area name is “the standing market,” a Souq with an old history said to span across 200 years. Historically, it contained different types of sub-markets for wholesale and retail trades, with buildings characterized by high walls, small windows, and wooden portals, as well as open air stalls for local vendors. Bedouins used to hold their own markets on Thursdays by selling timber and dairy products. The market place was also a gathering space for fishermen. The Souq acquired its importance not just because of its unique character but also because of its geostrategic location at the eastern end of the old center: facing the waterfront that was once characterized by the strong presence of fishing boats and dockyards, currently the location of the Museum of Islamic Arts and the Emir Ruling Palace. The Souq was the major accessible entry point to the old city, called Msheireb Valley. The Souq was derelict and most of its unique buildings became dilapidated because of urban development and modernization needs that started in the 1970s and continued over a period of three decades from the 1960s (AKDN, 2013 ). With an initiative from the Private Engineering Office of the Emiri Diwan (the Ruling Palace), the Souq has acquired a new image by being restored to its original condition, including reconstruction and renovation using authentic materials and skills. However, although it retained its function, new art galleries, traditional cafes and restaurants, cultural events, and local concerts were introduced as new functions, attracting many city residents and visitors (Figure 5 ).

|

|

|

Figure 5. Visitors׳ activities in the main pedestrian spine of Souq Waqif. (Source : Authors). |

2.3. Aspiring place making and urban regeneration

Within close proximity to Souq Waqif, the Msheireb development stands as an under construction urban regeneration mega-project on the remains of a historic residential site. The site includes a few intact traditional open courtyard houses and other deteriorated ones. Decision makers were concerned with the way it affects the city׳s authentic image. The driving philosophy was to deliver a sustainable mixed-use intervention that reflects Qatari culture and heritage not just by its authentic representation but also through its spatial environment. With a master plan developed by EDAW-AECOM, the initial designs reflect the essence of traditional architecture in Qatar with state-of-the-art technology and urban living quality. The project involves different dimensions of urban regeneration and serves as a new neighborhood in the old center. The intervention “is to initiate large-scale, inner-city regeneration that will create a modern Qatari homeland rooted in traditions and to renew a piece of the city where global cultures meet but not melt” (Law and Underwood, 2012 :131). Physically, the project is designed to reduce the use of cars and to attract locals back to the old center by providing a public realm, with an attempt to integrate local identity and advanced sustainable technologies. In a harmonious balance, the master plan encompasses five main districts, each of which has its own character. Regeneration is accentuated by the reinterpretation of old architectural language and the emphasis on creating a traditional sense of community while projecting local culture and heritage that invoke Doha׳s earliest physical and social foundations (Msheireb, 2011 ).

The three urban interventions introduced in Doha׳s historic center are top-down governed developments, pushed for rapid and high quality urban change. In addition, the majority of society accepts the three urban transformations because of the direct transfer of wealth from the supreme power to city developers and consumers. Similar to other cities in the Persian Gulf, Doha will experience an increase in the tourism industry, multinational corporations, and real estate developments, thus giving extra importance to the historic core. Nevertheless, decision makers delivered these developments through transparent, yet uni-authoritarian governance. The decision-making process was fast and effective toward a predefined vision. However, such developments lacked grassroots social organization or sociopolitical components, as sustainability requires.

3. Exploring the impact of change on the old center of Doha

Reference to a wide spectrum of studies that were previously conducted by the authors is made to explore the impact of change on the old urban center of Doha. The types of impact are identified in two categories: the first relates to key socio-spatial dimensions and the second is concerned with typo-morphological impacts.

3.1. Socio-spatial impacts

Typical in museum architecture, the relationship between the building from inside-the elegant receptacle and its outside-the spectacle appears to be paradoxical. Such a relationship seems to be well addressed in Pei׳s museum design (Salama, 2011a ). In addressing this notion, the building has a strong presence from the outside and dramatic scenes from inside in addition to the spectacular views generated by the park design. Considering that the site is not physically positioned in the heart of the old center, its impact on the traditional sense of place and the old center׳s historic essence is minimal. However, it is an iconic landmark that adds to the generic urban landscape of the area and can be regarded as an exceptional intervention that represents an aesthetical merger between regionalism and post-modernism while adopting the needs of the city׳s inhabitants.

The Souq Waqif reconstruction can be seen as a successful heritage-led project that introduced change to promote a sense of place through the creation of a vibrant public realm. It hosts various activities that cater to a wide spectrum of people, some with cultural meanings and others with commercial functions and authentic restaurants. The argument is that “Souq Waqif can be portrayed as an exemplar of urban space diversity in the Gulf region” (Salama, 2011a :179). During national and religious festivals, the Souq offers several cultural and tourist activities that foster a sense of interaction between local citizens and the expatriate community. The importance of Souq Waqif versus the Museum can be elucidated in a recent survey involving 490 residents of different cultural backgrounds to explore urban space diversity and the way in which the two urban interventions are identified among eight new urban projects (Salama and Gharib, 2012 ). Notably, 57% of the respondents identify the Souq as a center for the city, 49% identify it as a project that represents the city, and 39% identify it as the most visited space. Less significant figures are generated in the responses to the Museum intervention (Table 1 ).

| Identification of the Project | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identified as center (%) | Identified as periphery (%) | Identified as representing the city (%) | Identified as most visited (%) | |

| Souq Waqif | 57 | 8 | 49 | 39 |

| Museum of Islamic Art | 22 | 20 | 16 | 16 |

(Source : Salama and Gharib, 2012 ).

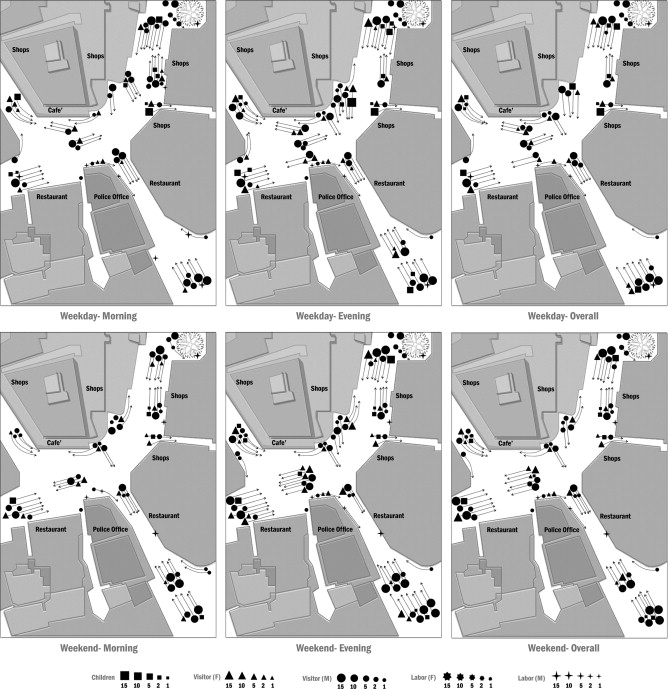

A closer look at one of the key settings within Souq Waqif reveals the way in which it has become one of the most attractive leisure spaces in Doha; it caters to diverse groups, including tourists, Qataris, and expatriate residents. Conducting behavioral mapping of the selected setting within the Souq discloses the authentic use of the space (Salama and Wiedmann, 2013 ) (Figure 6 ; Figure 7 ). Qataris and non-Qataris have been observed to visit the immigration office for various reasons, including authenticating documents or renewing visas. Other users, including residents and tourists, frequented the space for dining or socialization, because the area has a diverse variety of ethnic restaurants and attractive outdoor cafés. Tourists who stop over in Doha en route to other destinations often visited the space to shop, to admire the “traditional” architecture representative of the reconstructed and renovated Souq buildings, and to experience or to investigate several cultural aspects of Qatar. Typically, groups of tourists were observed to visit traditional shops prior to relaxing in cafés or dining. A low representation of children, probably because of lack of activities and facilities that would cater to them, was also noted. Male Asian workers would sometimes visit the space from nearby residential areas located south of the Souq. However, security police stand in front of and near the immigration office and have been known to repel certain visitors, particularly unwelcome laborers or those who have been observed as annoying. Mounted police officers also frequently patrol the streets and are one of the attractions, especially for tourists.

|

|

|

Figure 6. Generated behavioral maps based on observation periods at Souq Waqif. (Source : Salama and Wiedmann, 2013 ). |

|

|

|

Figure 7. Visitors׳ activities in the main pedestrian spine of Souq Waqif. (Source : Authors, 2013) |

The mapped space is one of the major arteries of the Souq; it is lined by various restaurants with roof terraces and outdoor cafés. In generic terms, the space is lively and well frequented at all times. However, it is more vibrant on weekends than on weekdays, and in the evenings rather than in the mornings. The reason may likely be the opening times of restaurants and cafés. Visitors generally go there for a meal or coffee with friends and family, whereas others may go shopping. The space was observed to be primarily used in the mornings as a space en route to shops or the immigration office, whereas it was used in the evenings for dining in restaurants or cafés, as well as for shopping in the adjacent traditional market or handicraft shops. Crowds were bigger in the evenings rather than in the mornings because the majority of visitors, other than tourists, were more likely to be at work. The space, as part of a pedestrian passageway to the traditional market area, seemed to be functioning well. However, the lack of activities and venues for children was also noted.

Although Msheireb urban intervention remains under construction, certain socio-spatial impacts can be conveyed. The urban design concept integrates the courtyard typology by translating it into modern blocks, which, however, is suggestive of European city cores rather than traditional Islamic cities. The large share of commercial use transforms the earlier residential neighborhoods into a major business hub. Although this shift to mixed and commercial use is needed to re-establish Doha׳s old core as one of the main urban centers, it also implies a discontinuation of a historic urban scene. Moreover, the project thrust to deliver a benchmark for emerging lifestyles attempts to create an intervention that is not just a glass or metal greenhouse but one rooted in local culture, with plazas acting as urban lungs for the development, while drawing from Qatari traditional architecture as a main quality of the proposed surrounding buildings.

3.2. Typo-morphological impacts

The three urban interventions in the old center are introducing significant impacts on urban morphologies, including land uses, urban densities, and spatial configuration. In the case of Souq Waqif, the agglomeration of warehouses and stores was replaced with a replicate of the historic market. The museum project replaced 15 ha of potential commercial projects and extended the public realm along the Corniche. However, the most significant morphological transformation is expected in the Msheireb urban regeneration project, where a wide spectrum of new typologies and uses are introduced. As part of a comprehensive research project (Wiedmann et al., 2013 ), a survey based on historic photography and GIS data unveils that the district was occupied by residences that made up approximately 60% of the total gross floor area (GFA) (Table 2 ). Offices and retail and light industries occupied the remaining plot area. Moreover, the majority of buildings were medium-rise apartment buildings with retail and services on the ground floors. Approximately 25% of the built area was occupied by low-rise residential buildings. Based on GIS population statistics, between 10,000 and 15,000 inhabitants lived in Msheireb before the district was demolished.

| Category | Msheireb 2006 GFA (m2 ) | (%) | Msheireb 2006 GFA (m2 ) | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residential | 192950 | 60 | 221,643 | 29.0 |

| Apartments | 141,950 | 199,159 | ||

| Houses/townhouses | 51,000 | 22,483 | ||

| Offices | 63,000 | 19 | 253,855 | 33.5 |

| Public sector offices | 0 | 74,327 | ||

| Retails | 65,000 | 20 | 93,646 | 12.5 |

| Community services | 2400 | 1 | 19,137 | 2.5 |

| Mosques | 2400 | 4560 | ||

| Schools | 0 | 5996 | ||

| Hotels | 0 | 0 | 116,813 | 15.5 |

| Cultural–national archive | 0 | 0 | 54,519 | 7.0 |

| Total | 323,350 | 100 | 759,613 | 100 |

(Source : Wiedmann et al., 2013 ).

Based on the Msheireb project master plan, GFA for residential use is increased to 221,643 m2 , which is only approximately 30,000 m2 more than in the previous district. However, the residential share of the total GFA will decrease to 29%, which is caused by the overall GFA increase to 759,613 m2 (Msheireb, 2011 ). Thus, the overall built density is significantly increased to 310% of the total plot area compared to the previous district. By contrast to the former configuration, offices will occupy almost one-third of the total GFA, which will result in four times more office space. In addition, 33% more retail space will be integrated, mainly on the ground floors. While the previous district did not have hotels, approximately 16% of the future total GFA is reserved to hotel developments. Art galleries and the National Archive will further underscore the cultural importance of the new district. The most significant transformation can be expected from the resettlement of high-income groups. The northern part of the district and approximately one-fifth of the residential GFA is reserved for local communities, whereas the southern and more densely built part accommodates medium- to high-income expatriates and their families. This reallocation of the local community in Doha׳s old center is part of the idea to introduce urban lifestyles and to initiate gentrification processes. However, the overall population density within the district can be expected to drop significantly to 200 inhabitants per hectare compared to the earlier average of approximately 500 inhabitants per hectare.

The high built density of the Msheireb project is mainly caused by the gradual increase in building height from three to seven floors in the northern part of the project to 20–30 floors in the southern part. By contrast to the previous district, where approximately 300 small-scale buildings were built side-by-side in dense clusters, the new development includes approximately 100 buildings, mainly built in large blocks (Figure 8 ). However, the close proximity between buildings remained a key characteristic despite the increase in building heights. Another main difference to the past morphology is the introduction of nine public plazas in strategic locations and the introduction of various modes of transportation, including bicycle and bus routes.

|

|

|

Figure 8. A typological comparison between the Msheireb district in 2004 and the new master plan. (Source : Google Earth and authors). |

4. Critique: mapping urban interventions on types of change in historic centers

Ideally, a change in old and historic centers aims to introduce new interventions with the best contextual harmony. The three types of change for achieving urban harmony are “contextual uniformity, or contextual juxtaposition, or contextual continuity or a combination of these” (Tiesdell et al., 1996 : 188–190). On the one hand, Souq Waqif is considered a change by contextual uniformity because it repeats the historic beats and replicate past closures and morphologies. Although copying is typically rejected by many contemporary urban theorists, it is required to sustain images of lost heritage in certain cases. In this case, the restoration and reconstruction were sensitive, either in the materials used or in the local technology utilized, to the historic architectural elements. Contextual juxtaposition exists within the two interventions of the Museum of Islamic Arts and the Msheireb regeneration – as they are new additions to the old center – that attempt to respect the contextual particularities of their sites. Specifically, the Msheireb urban regeneration introduces an extra layer of esthetic integrity to the local context in an effort to offer a new interpretation of local architectural language. On the ground level, all three interventions share the objective of creating public activities through pedestrian movement and continuity. The ground level is also surrounded by a variety of commercial and cultural activities.

On the other hand, contextual continuity often refers to the respect of architectural layers from the ground level and upwards, such as that new interventions may need to respect the notion of activity continuation, for example, retail frontals size and height. This continuity appears to be missing in the three interventions because of their functional differences and the peculiarity of each. The danger of such discontinuities is that new interventions may produce, through time, a sense of local character dilution with greater loss of traditional fabrics. Despite the relative success of the Museum and the Souq, and the anticipated realization of the Msheireb development, the old center may be at risk if further changes are introduced without sufficient and effective respect to the whole. In such a case, a change by contextual uniformity will be the most appropriate to retain the historic sense of place. Currently, this situation is quite challenging in the old center of Doha because the vision of the planning authorities is to reach global standards leading to further utilization of contextual juxtaposition, compromising the old center׳s uniqueness.

5. Conclusion: the “local–global” delicacy of change in Doha׳s old center

Despite being large-scale and typologically different, the three levels of urban interventions introduced at Doha׳s old center represent reactions to the global condition, the aspirations of rulers, and a sense of history and local tradition. With varying degrees, the three typologies positively answer the question of “Can a practice or a design solution be simultaneously local and global?” The aspiring image making and the iconic architectural intervention of the Museum and its park simultaneously address global and local issues by consciously attempting to react to global cultural flows, translating the cultural aspirations of Qatar into a manifestation that speaks to the world architecture while addressing demands placed on the design by context and the regional culture. The reconstruction of urban heritage exemplified in the Souq Waqif validates the notion of simultaneity of global and local issues through a wide spectrum of activities and the diversity of users. The aspiring place making and urban regeneration evident in the Msheireb urban regeneration reflects global aspirations while rooting such aspirations into the local vernacular.

Responding to the question of adopting universal best practices without ignoring local knowledge , the three interventions integrate quality international standards while addressing local knowledge. This idea is manifested in realizing a world-class museum designed by a renowned architect who was able to incorporate international experience into regional environmental imagery. Universal best practices are evident in the master plan and in the design qualities of the Msheireb urban regeneration intervention. Such practices invigorate the development of a new architectural language that envisages the selection of historic references plowing from local and regional heritage. Notably, the reconstruction of Souq Waqif focuses exclusively on local factors, as exemplified by the use of indigenous materials and construction techniques.

In reacting to the question of whether prioritizing local influence would represent narrow-mindedness , the two interventions of the Museum and the Souq generate a new urban discourse in the city on diversity, usability, accessibility, and connectivity. Serving people of different age groups and cultural and socio-economic backgrounds does not represent blind resistance to the global or blind adherence to the local, but creates a harmonious balance between the two. However, the absence of sufficient activities for children in the Souq and limiting its use to middle- and upper-income groups should be noted. The public has yet to see how the Msheireb urban regeneration project addresses these notions and whether it will achieve its promises.

References

- Ahmadi, 2008 A. Ahmadi; The Urban Core of Doha: Spatial Structure and the Experienced Centre; (MSc Thesis in Advanced Architectural Studies) University College London, London (2008)

- AKDN, 2013 AKDN – Aga Khan Development Network, 2013. Souk Waqif 〈http://www.akdn.org/architecture/project.asp?id=3564〉 (retrieved 17.03.13.).

- Al Khemir and Jodidio, 2009 A. Al Khemir, P. Jodidio; Museum of Islamic Art; Prestel Publishing, Doha, Qatar, New York (2009)

- Law and Underwood, 2012 R. Law, K. Underwood; Msheireb heart of Doha: an alternative approach to urbanism in the gulf region; Int. J. Islam. Archit., 1 (1) (2012), pp. 131–147

- Msheireb, 2011 P. Msheireb; Msheireb – Downtown Doha; Msheireb Properties, Doha (2011)

- Nagy, 2000 S. Nagy; Dressing up downtown: urban development and government public image in Qatar; City Soc., 12 (2000), pp. 125–147

- Nagy, 2006 S. Nagy; Making room for migrants, making sense of difference: spatial and ideological expression of social diversity in urban Qatar; Urban Stud., 43 (2006), pp. 119–137

- Salama, 2011a A.M. Salama; Identity flows: the Arabian Peninsula, emerging metropolises; Luis Fernández-Galiano (Ed.), Atlas Architectures of the 21st Century – Africa and Middle East, Fundación BBVA, Madrid (2011), pp. 175–221

- Salama, 2011b Salama, A.M. 2011b. A dialogical understanding of urban center(s) and peripheries in the city of Doha, Qatar. In: Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Architectural Humanities Research Association: Peripheries 2011, Queen׳s University, Belfast.

- Salama and Gharib, 2012 A.M. Salama, R.Y. Gharib; A perceptual approach for investigating urban space diversity in the city of Doha; Open House Int., 37 (2) (2012), pp. 24–32

- Salama and Wiedmann, 2013 A.M. Salama, F. Wiedmann; Demystifying Doha: On Architecture and Urbanism in an Emerging City; Ashgate Publishing Ltd., Surrey (2013)

- Tiesdell et al., 1996 S. Tiesdell, T. Oc, T. Heath; Revitalizing Historic Urban Quarters; Architectural Press, Oxford (1996)

- Wiedmann et al., 2013 F. Wiedmann, V. Mirnicheva, A.M. Salama; Urban reconfiguration and revitalization: public mega projects in Doha׳s historic centre; Open House Int., 38 (4) (2013), pp. 27–36

- Wiedmann et al., 2012 F. Wiedmann, A.M. Salama, A. Thierstein; Urban evolution of the city of Doha: the impact of economic transformations on urban structures; J. Fac. Archit., 29 (2) (2012), pp. 35–61

Notes

1. The definition of “Corniche” – a term taken from the French language – is “a road built along a coast or along the face of a cliff”, and it is derived from the Latin word “Corniche” an architectural term that designates the top edge of a façade, where it meets the roof. It is widely used in the Mediterranean and the Middle East, where new maritime facades were designed in major coastal cities – often by French architects and urbanists – during or following French decolonization.

Document information

Published on 12/05/17

Submitted on 12/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?