Abstract

Architectural and personal influences on neighboring behaviors were studied in a residential neighborhood using both qualitative informal conversations, and systematic recording of activity in the neighborhood׳s social space. This dual approach produced new insights into neighboring behaviors and social networks. It was discovered that the residents who participated in the social space were only a portion of the resident population. There was an additional neighborhood-based network whose neighboring was not conducted in the social space; instead it was maintained by direct house-to-house contact. It was also found that some individuals chose not to participate in any neighborhood social network. The social space was an effective neighboring venue for those residents who chose to use it, but did not attract commingling of groups. Contrary to an assumption in previous neighboring research, there are social groups which develop and maintain themselves without participation in a social space.

Keywords

Neighborhood ; Social network ; Community ; Residential design ; Shared space

1. Introduction

Residential neighborhoods are places of potential social interaction and social relations. Understanding how those interactions and relations develop needs to be understood, because the development of community life is a fundamental process in social organization and experience (Almgren, 2001 ).

Neighborhoods expose their residents to factors distinct from (while operating in conjunction with) family processes inside the homes (Grannis, 2009 , pp. 1–3). Different neighborhoods have different types of effects; they could maintain social order or disorder, facilitate or inhibit cooperative action, and make neighbors appear as either resources or threats.

Gehl (2011 , p. 77) measured a public space׳s social success, whether in civic, shopping, or residential settings, by its total “liveliness”, that is, the total number of people participating in the space. He presumed that if the people are there, active and complex urban life including social interactions can follow. In residential settings specifically, Brower (2011) , Grannis (2009) , and Gutman (1966) have sought interaction networks more explicitly; through network formation, a residential neighborhoods׳ social relations can tend toward identification of “community”.

Putnam (2001) posited that social networks and their expectations of reciprocity have value, both to network members and, at least in some instances, to the general public. Even casual social interactions or connections have value; they increase the likelihood that one person will come to the aid of another when needed. Outcomes of social networks include child welfare, educational performance, personal health, public participation, compliance with laws, and frequency of crime (Holtan et al., 2015 and Putnam, 2001 ).

As will be cited in the next section, previous research has studied neighboring behaviors in residential neighborhoods, and the physical and social features that influence them. The study reported here aimed to extend knowledge in these areas by examining together both the architectural (design) and personal influences on neighboring behaviors and neighborhood networks. Specific questions addressed in this study were (1) the role of certain architectural features in facilitating neighborly participation, and (2) the influence on participation from individuals׳ personal characteristics and overall lifestyle concerns such as family and work obligations. As will be shown, this distinctive dual inquiry allowed the recognition of new insights into neighboring behaviors and neighborhood social networks.

2. Previous studies

Previous research has studied social networks and their values in residential neighborhoods, neighboring behaviors, the types of behaviors that occur in shared or public spaces, and design features that influence them. Important findings and viewpoints from these types of research are summarized here.

2.1. Social networks

The connections that hold social relations together are various, such as ethnic identity, religious congregation, kinship, friendship, economic status, work, profession, and political ideology. Some are formalized through institutions such as churches, clubs, or professional societies. Some are locally concentrated as in residential neighborhoods; others are globally dispersed. Different community memberships overlap with each other, and compete for participation and enforcement of norms (Chaskin, 1997 ). Many networks are shaped by complex exogenous social processes and issues (Almgren, 2001 ). People can be pulled away from local neighborhood networks by forces of modernization, urbanization, migration, and communication technology (Chaskin, 1997 and Wellman, 1996 ).

Some research has treated “community” as an ideal; in which to evolve into a “community” is a desirable achievement for the residents of any neighborhood. Long effort has been given to defining that ideal, including McMillan and Chavis׳ (1986) much-cited formulation, in which a complete community has four elements: membership (belonging and sharing), influence (making a difference to the group), fulfillment of needs (meeting of individuals׳ needs through the group), and shared emotional connection (common history, places, and experiences). None of the definitions have been final (Brower, 2011 , pp. xxviii–xxix). In this paper the term “community” is used without normative implications; it is used almost interchangeably with “social network”, with the implication only that it may represent a relatively strong and complete type of network.

Social networks can constitute useful resources. The concept of social capital, articulated by Coleman (1988) and widely applied by Putnam (2001) , refers to shared normative conditions based on neighbors׳ social ties and institutions. It builds obligations, expectations, and trust, as people do things for each other in expectation of reciprocity. It guides and facilitates action. It builds information channels. Most forms of social capital are created or destroyed as by-products of other activities. Its effectiveness depends on the strength of relations between individuals, and its reinforcement by other social relations and institutions. Those social relations persist, which are discovered to work for the individuals and the group.

The development of community is not always for the good (Grannis, 2009 , pp. 1–3; Putnam, 2001 ). An individual׳s commitment to one community could lead to separation from another (McMillan and Chavis, 1986 ). Social capital can inhibit some potential actions, or derail them from their original goals (Karner, 2001 ). Wilson (2012 , pp. 60–61; 259–260) emphasized the socially isolating and disorganizing effects created by macrolevel exogenous factors such as economic restructuring, concentrated poverty, and racial segregation. In neighborhoods influenced that way, gangs and other social affiliations based on fear, hatred, and crime, are arguably forms of community.

2.2. Neighboring behaviors

In residential neighborhoods, interactions among residents vary in intensity, frequency, and intimacy (Grannis, 2009 , p. 17; Gutman, 1966 ).

Gehl (2011 , pp. 15–21) distinguished between degrees of contact intensity. At the low end of his scale are passive contacts involving merely seeing and hearing others. These low-intensity contacts are sources of information about the social world, and opportunities for inspiration and stimulation. At greater levels of intensity, contacts include acquaintanceships, friendships, and finally close friendships. Each form of contact has value in itself, and, according to Gehl׳s formulation, is a prerequisite for more intense and complex interactions.

Similarly, Grannis (2009 , pp. 4 and 19–26) hypothesized that interaction among residents is the primary process producing neighborhood communities. He posited a scale of neighbor interaction frequency and quality. At his low level of interaction, neighbors encounter each other unintentionally, during which they have the opportunity to observe each other׳s behavior, to acknowledge each other׳s presence, and to initiate conversation. Unintentional contacts can be abundant among residents who live close to each other on streets with provisions for pedestrian movement. Passive contact is a “latent tie”, a possibility for further social interaction. At higher levels of Grannis׳ neighboring, residents intentionally initiate contact. The final level of neighboring consists of activities built upon mutual trust.

Among the personal characteristics influencing the scope and intensity of local networks are residential stability, and similarity of income, education, child-rearing practices, political ideology, ethnicity, life-cycle stage, and life style (Brower, 2011 , pp. 13–19; Wilkerson et al., 2012 ). Similar people tend to communicate with each other easily, to share values and aspirations, and to recognize and conform to group norms.

Children facilitate household interaction. They use neighborhood streets to play games, walk pets, ride bicycles, and walk to schools and parks. Through their neighborhood interactions, households with children are influenced by each other׳s norms and values; they become involved in the socialization of each other׳s children. Households with children tend to have neighboring relations much more abundant, and “neighbor networks” much larger, than those without (Grannis, 2009 , pp. xvi–xviii, 93–94, and 136–138; Marcus and Sarkissian, 1986 , p. 42).

Adults, unlike children, can have many venues for social relationships outside their neighborhoods, including work and voluntary activities. Commuting to work leaves little time for ties with residential neighbors (Marcus, 2003 ). Local neighbors tend to be only a minority of most adults׳ social ties, and many local relationships are weaker than others. Actions such as waving to one another on the street, chatting over a garden fence, borrowing a tool, or attending a neighborhood meeting do not necessarily imply intimacy or commitment. However the frequency of contact (interaction) is high in local neighborhoods, especially face-to-face contact (Brower, 2011 , p. xxix; Wellman, 1996 ).

Formal neighborhood organizations such as homeowners׳ associations are places for specific neighbor encounters and interactions as they work through shared interests and discordant agendas (Brower, 2011 , pp. 13–19).

In some neighborhoods, although residents are friendly on the sidewalks and in shared facilities and organizations, they do not come closer together. Their personal priorities emphasize family, work, and private life outside the neighborhood. Their neighborhood social ties remain superficial; they look to their residential areas more for privacy than cooperation, and have little interest in building local community (Brower, 2011 , pp. 54–56).

2.3. Architectural (design) features that influence behaviors

Neighbor relations grow up in networks of connected residential streets with pedestrian access and limited vehicular traffic (Grannis, 2009 , pp. xvi–xviii and 28). The pubic streets are neighborhoods׳ “social spaces”, where interactions between individuals from different households can occur. Residents consider streets with limited vehicular traffic as extended parts of their home territories (Appleyard and Lintell, 1972 ). Much initial interaction is limited to those who live within a few households of each other, or within sight of each other.

Neighborhood spaces that are formally shared among the households—“owned by a group and usually accessible only to group members”—are particularly strong social spaces. They are places for casual social interactions, shared responsibility, and development of social networks, among familiar neighborhood people (Marcus, 2003 and Marcus and Sarkissian, 1986 , pp. 40 and 119). Outdoor shared spaces are most significant if they are bounded and accessed by the dwellings they serve, entered at controlled points that distinguish them from public parks, and located to bring residents walking through them frequently. In them, canopy trees draw people to enjoy the restorative benefits of greenery, and make the spaces comfortable for lingering when they encounter neighbors (Coley et al., 1997 , Holtan et al., 2015 and Marcus and Sarkissian, 1986 , p. 219).

Like shared outdoor spaces, neighborhood shops such as diners, markets, and hair salons are places where residents may encounter each other (Oldenburg, 1997 ). In them residents can obtain neighborhood news, get to know each other, and identify others with shared special interests. Farahani and Lozanovska (2014) described analytically how local commercial areas could contribute to sharing and interaction among nearby residents. Wilkerson et al. (2012) found that neighboring feelings and behaviors increase with greater diversity of destinations to walk to.

Private front porches or fenced front gardens facing onto residential streets or other social spaces enable residents to sit in safety and personalized comfort while looking out at passersby (Gehl, 2010 , pp. 82–85 and 103; Marcus and Sarkissian, 1986 , pp. 185–187). Like other popular places for staying, they are along the edges of the space (Gehl, 2011 , pp. 155–159; Gehl and Svarre, 2011, p. 149). In their porches, residents protect private life and regulate public contacts. Private front entry paths, gates, and steps connect the private entrance to the public domain, within the household׳s territory. Wilson-Doenges (2001) found that front porches that are most frequently used have enough space to hold their furniture and activities, resident lifestyles that support front-porch use, limited automobile traffic on the street, and little competition from developed back-yard spaces, indoor air conditioning, or indoor electronic entertainment.

2.4. Activities in social spaces

Gehl (2011 , pp. 9–14 and 129) distinguished activities in public spaces which are necessary, optional, and social. Necessary activities are required by tasks or circumstances outside a space, such as going to work, waiting for a bus, or running errands; they are influenced little by the quality of local environments. Optional activities are voluntarily chosen, such as taking a walk or pausing to enjoy a setting or a view; they are greatly influenced by the quality of environments. Social activities evolve from and expand upon already-occurring necessary or optional activities, where other people are present.

Gehl (2010 , pp. 120–145) also distinguished activities which are moving or staying. Both are either necessary or optional. Examples of moving activities are strolling, exercising, and walking to destinations. Optional moving activities are encouraged by a route׳s safety, comfort, and interest. Examples of staying activities are outdoor labor, waiting for a bus, eating, watching, visiting, or playing.

Gehl (2010 , p. 72) observed in residential streets in Ontario, that staying activities lasted longer than moving activities, and therefore contributed most of the life in the streets. They consisted of playing, garden maintenance, talking, and sitting following what was going on.

In Australia, Gehl and Svarre (2013 , pp. 98–99) observed that residents frequently sat in their front gardens and spent time on recreation, eating, conversing, and minor tasks. “The prerequisite for street life was the building density, which encouraged many people to get around the area by foot. In turn, life on foot in front of the houses made spending time on the public side of the houses meaningful and interesting” (Gehl, 2010 , pp. 82-83).

3. Method

In this study, neighboring behaviors, design, and personal situations were observed in a residential neighborhood in the college town of Athens, Georgia. This neighborhood was selected for study because it has a shared space and other design features which, according to the research reviewed in the previous section, tend to favor neighborly interaction. This made it a test case for the response of various residents to those features, and the features׳ roles in residents׳ lives. In addition the two-year residence there of one of the co-authors (Bruce K. Ferguson, BKF) as a participant-observer enabled distinctive types of personal-situation and behavioral insights to be gained.

Although the neighborhood׳s individual homes were not unusual at the time of their construction in the mid-2000s, their arrangement around a shared space was not typical. This layout had come about from the long, narrow dimensions of the development site, which limited the number of dwellings that could be built and their possible arrangements, and compelled the provision of some sort of open space, not occupied by private homes. Consideration of the new-urbanist ideas of the time led to the dedication of the open space to a park-like level lawn (Josh Koons, personal communication, August 14, 2013).

3.1. Study site

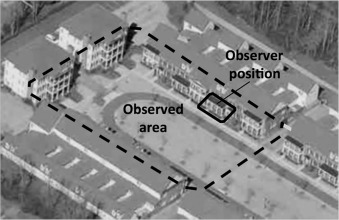

The neighborhood is shown in the upper left of Figure 1 , arranged as a single residential “cluster” around its central shared lawn. Along the two long sides of the cluster are 32 brick townhouses. At the end of the cluster are two white buildings holding 12 apartment units.

|

|

|

Figure 1. The study site (after Bing Maps, www.bing.com, 12 August 2015). |

An adjoining commercial area with its parking is shown in the lower right of Figure 1 , adjacent to a main street. The residential area is distinguished from the commercial area by a single entrance gate which closes at night. In the commercial area are three restaurants and several small shops. Outside of this complex, within 0.5 km along the main street, are large commercial areas with many grocery stores, drug stores, restaurants, pizza shops, coffee shops, etc.

As shown in Figure 2 , all of the dwellings bound and face onto the central space; two-thirds of the townhouses and all the apartments have front porches facing the space. The lawn is lined with trees. It is ringed by a vehicular lane and a sidewalk; cars tend to drive slowly on the narrow (4.9 m wide) loop road. The space is 42 m wide between porch fronts, which is big enough for a variety of uses without intruding on private dwellings. A common building also faces the shared space; residents use it for events such as children׳s birthday parties, holiday dinners, and morning bridge clubs. The central space and other shared facilities are used only by residents and their guests. Neighbors tend to be known to each other due to the neighborhood׳s small size, and the visibility of everyone who passes through the space.

|

|

|

Figure 2. House fronts and central shared space. |

Townhouse parking is in garages attached to the backs of the homes. Apartment parking is outdoors behind the apartment buildings. Visitor parking is along the street in front of houses. As shown in Figure 3 , the neighborhood׳s shared back lanes are used only for parking access and trash storage; they are utilitarian in character, and uninviting for personal or social use.

|

|

|

Figure 3. Garage access lane behind townhouses. |

The neighborhood׳s residents are middle- to upper-middle income, mostly white and college-educated. Many are empty-nesters retired from professional careers. Other residents are younger families, in or preparing at university for professional careers. The neighborhood׳s only children are toddlers under the care of young parents. All residents have private autos. Domestic tasks such as laundry and day care are within individual homes or otherwise taken care of privately. All dwellings are air-conditioned, which is valuable in the area׳s hot, humid summers.

Some of the dwellings are vacant for months at a time, as their owner-residents live seasonally in cooler climates or go on leisure travel. Other residential units, which are owned by the original developer for rental, are vacant from time to time between successive tenants׳ leases.

3.2. Data collection

Two kinds of data were gathered, using two different methods.

One method was informal conversations with neighborhood residents throughout the 24-month period when BKF was a fellow resident. He was familiar to all the residents, developed personal relationships with some of them, and was invited inside some of their homes. Multiple, unplanned, wide-ranging discussions with fellow residents yielded multi-faceted, qualitative information about residents׳ personal, family, and work situations, and their neighboring practices and motivations. Daily informal observations of residents׳ comings and goings gave further detailed knowledge of the residents׳ personal living situations.

The second method was systematic recording of outdoor activity observed in the central shared space. Preliminary observation and planning for this method were conducted in the first 12 months of BKF׳s residency, after which observations were recorded from May 2014 through May 2015. Since preliminary observations had found almost no pedestrian activity in the back lanes, the decision was made to record observations only in the central space, where activity occurred. The observed area is outlined in Figure 4 . It comprised about half of the neighborhood׳s central space. The almost-exclusive users of this area were the residents of the 14 townhouses and 12 apartments that faced onto it. All outdoor activities, including those on private porches, were recorded; everything outside the homes׳ front doors was considered to be in the functionally shared space where interaction could occur. To make observations BKF sat in his townhouse porch, known to neighbors as a resident and a university professor, working on academic papers while recording observed activities. No explanation or “cover story” for BKF׳s presence was necessary. The records followed what Gehl and Svarre (2013 , pp. 3–5 and 96–97) called a “diary method”. They included the identities of people, types of activity, interactions between people, time of day, location in the space, and factors that influenced activity such as weather and daily work and commuting schedules. Observations were made in a variety of seasons of the year, days of the week, and times of day. They were conducted on 24 occasions, totaling 16.33 h.

|

|

|

Figure 4. Location of outdoor behavior observations. |

Both methods were flavored by BKF׳s status as both participant and observer. Participant observation has the advantage of intimate familiarity with group members and their practices, through involvement with them in their environment. It has the disadvantage of influencing their behavior in a way which might not have otherwise occurred. During most of the study period, BKF had his own dogs, which he walked around the neighborhood, and kept with him on his porch while observing. They were well-behaved dogs, and were enjoyed by many residents who encountered them. They attracted porch-front conversations with passersby. When interesting activities started to happen with dogs or children on the central lawn BKF took the dogs out and joined them. BKF frankly enjoyed this life; he cheerfully encouraged interaction, and welcomed invitations into residents׳ homes. All encounters were opportunities for further informal conversations. It is acknowledged that BKF may to some degree have stimulated more interaction than would otherwise have occurred.

4. Results

Most activity events in the space were brief “comings and goings”, as visitors got into and out of cars, workmen came and went with their vehicles, or residents walked out to shops or restaurants. Many of those events were necessary activities (workmen׳s arrivals, commuting to work, walking to errands at management office).

The most active hours in the space were on weekends, morning through mid-day, when there were both “staying” activities on the lawn and porches, and numerous comings and goings as visitors arrived at homes and people conducted their special weekend activities. On weekdays there was sometimes a brief burst of activity between the end of the workday and dinner hour. The least active hours were dinner hour and weekday working hours, when young families (the principal outdoor participants) were occupied with work and family obligations. On any day of the week, activity was reduced in uncomfortable weather.

Prolonged outdoor events were staying activities. They consisted of sitting (often reading) on front porches, or playing actively with children or dogs on the central lawn, from which social activities sometimes grew. The porch was the place for those who were willing to interact (even if only to see and hear) but not necessarily to engage in physical activity.

Moving activities were on the sidewalk; they consisted of exercise-walking on the sidewalk loop, or walking out toward nearby restaurants. Walking to more distant restaurants or grocery stores was done only by the young families, and one older resident who walked for exercise. Public busses were not used, although they were available close by.

A “draw” for people to come into the shared space was other people already there. The most visible and interaction-stimulating group in the neighborhood was one of the young families, who exercised their dog and toddler on the lawn. When they were present, a number of other people with children or dogs sometimes came out and joined. BKF׳s dogs were another gathering point; some people paused when his dogs were about.

Table 1 lists the social networks found to reside or work in the dwellings facing the sample area. The different groups were not associated with the neighborhood׳s two types of dwellings (townhouses and apartments); residents in all groups lived in both types of dwellings.

| Community | Number of people | Number of households |

|---|---|---|

| Regular outdoor participants | 10 | 6 |

| Older “indoor” community | 8 | 5 |

| No local community (external associations, or no associations) | 10 | 9 |

| Dwellings vacant intermittently, or throughout study period | 0 | 6 |

| Laborers | 1 at a time, average | 0 |

| Total | 29 | 26 |

The regular outdoor participants were only a portion of the resident population, and were not representative of the population as a whole. It consisted of young families finishing graduate degrees at the nearby university and beginning professional careers. In the shared space, they were visible playing energetically with their dogs or young children, exercise-walking, and working with academic papers on their porches.

The “indoor” group were retired, longer-term residents. They were friends with each other. They were observed in the shared space only on brief errands to the management office or each other׳s houses, or sometimes walking together to nearby restaurants. Their social venues within the neighborhood were indoors: the shared building, and their private homes. They tended to participate in the homeowners׳ association, to run the grounds and newsletter committees, and to organize neighborhood holiday dinners. They were also active outside the neighborhood, such as in churches, local student-group support, and charity activities. Their neighboring behaviors were not conducted outdoors in the shared space, and were not built upon the precondition of shared-space contacts. Instead they were initiated by deliberate and direct house-to-house contact. One of them, when BKF׳s family first moved in, came into BKF׳s house with a plate of cookies and said, “we want to get together”. She invited the new arrivals into her home, and introduced them to others in her group at dinners in nearby restaurants.

One lady who is classified in Table 1 with the “older” group had a unique role in the neighborhood. She was both retired and anxious for family-like company, so she interacted intimately with young families from the “outdoor” group. She had tragically lost her whole family in a car accident, and now was living by herself. She said that she was never going to be the grandmother she had always wanted to be. She sat on her porch reading, making herself more visible than other older residents. She joined one of the young families whenever they were in the shared space. She evolved into the surrogate grandmother for the family׳s young child, to the extent that the parents sometimes brought their child to her front door, where she took him inside to take care of him. There were no other individuals from the “older” group who regularly participated in the outdoor space, and no other individuals who casually mingled between the different groups defined in Table 1 .

A third resident group was noticed which had essentially no neighborly connection, and is called the “No local community” group in Table 1 . Most pointedly, a lone lady of retirement age was seen only at a distance, walking a dog on the back lanes and avoiding contact. As another resident described her, “she just does not like people”. Residents of several other households said hello as they came and went, but had no further role in the neighborhood׳s networks. For these people, either their social associations were elsewhere, or they did not want any community.

All three resident groups had chances to interact together at semiannual neighborhood potluck dinners, to which all residents were invited via email. At the dinners, members of the younger “outdoor” and older “indoor” groups interacted cooperatively but not intimately. No members of the “no local community” group attended the dinners.

A further group of people visible in the outdoor space were non-resident laborers, asked to come in day by day by residents or property managers in an economic relationship. They included caregivers, cleaners and repairmen working inside individual homes, and outside painters, roofers, window-washers and lawn maintenance people. They were seen going to and from their assignments, or at work outdoors.

Residents did not have or participate in any neighborhood- based virtual (electronic) community or social space. Emails between members of the “older” group and email distribution of community newsletters to all residents were the only electronic communications among residents.

Outdoor activity declined in the last four weeks of observation, for three reasons which indicate the dependence of outdoor activity on details of individual family situations. One of the previously visible and playful dogs was now being brought out less, because he had misbehaved and had to be kept under stricter control. Secondly, a previously visible and playful young child was being dropped off inside a lady׳s house who cared for him inside. Thirdly, BKF׳s dogs had been moved out of the neighborhood in preparation for his own departure, and no longer invited conversation or joining in play.

5. Conclusions and discussion

This study׳s findings gave distinctive insights into neighborhood architecture and community.

5.1. Communities in and outside of neighborhood

This study discovered a type of behavior which has not been emphasized in previous studies of neighboring behaviors and neighborhood communities. There is in this neighborhood a community of residents who visibly interact in their shared space, and in addition other communities who do not.

Gehl (2011 , p. 15) and Grannis (2009 , p. 19) described ladders of intensifying neighboring relations in outdoor shared spaces, and posited that participation in them is the foundational process of community. Such experiences work for some residents, such as the “outdoor” community found in this study, but they are not, according to this study, the only way neighbors interact, and not the only avenue to neighborhood social relations. There are also neighborhood social networks which develop and maintain themselves without residents׳ participation in a shared space. This study found multiple communities coexisting in one small neighborhood, of different life stages, household priorities, and shared-space participation. It also found individuals who chose not to participate in any neighborhood community. It is recommended that future studies of neighboring behavior attempt to identify both the “visible” outdoor community, as previous research has done, and the “hidden” indoor or externally oriented communities that may coexist in the same neighborhoods.

This affirms that local neighborhoods are only one source of social association; in some people׳s lives, neighborhood associations can be supplemented or replaced by others. Examples of other social connections are family, work, faith, sports-team following, university and military backgrounds, and political ideologies. All are open, dynamic systems, in which membership and commitment are relative and shifting (Almgren, 2001 and Chaskin, 1997 ).

This site׳s three nearby restaurants supported the older community as shared interests and social venues. According to previous research (Farahani and Lozanovska, 2014 and Oldenburg, 1997 ) a more diverse and frequently visited commercial area might provide further shared venues for interaction, specifically for elderly residents who do not participate in an outdoor space.

The absence of a “virtual” social space in this neighborhood may have resulted from the mature age of the householders. A younger generation of school-age and college-age residents, accustomed to modern electronic devices, might make more use of virtual neighborhood-based communities.

5.2. Architectural (design) features

This site׳s central space is an effective venue for neighboring behaviors for those residents who choose to use it. The space is an extension of the houses that face it, like the actively used residential street described by Appleyard and Lintell (1972) . This finding confirms Marcus׳s (2003) (Marcus and Sarkissian, 1986 , pp. 40 and 119) emphasis on and design recommendations for formally shared spaces.

However the space was not strong enough to attract commingling of the neighborhood׳s different communities. Only one lady from the “older” group, who had unique personal reasons to seek companionship, came out to join shared-space activities; no other members of her group or of the “no local community” group participated in the space. Hence it is concluded that although properly designed shared space contributes to social networking, it does not necessarily overcome people׳s demographic differences or individual priorities.

Facing onto the space, this site׳s front porches are effective transitions between shared and private spaces and activities. Gehl (2010 , pp. 82-85) described semiprivate front porches and yards as “soft edges”; they are connecting links between public and private. In contrast, “hard”, non-active house fronts are dominated by garages or parking places, without transition between private interior and public exterior. Figure 5 illustrates that this site׳s porches are, like other places that attract sitting and staying (Gehl, 2010 , pp. 120–145), protected alcoves with a view out to the interesting space. What happens on the porch is under the residents’ knowledge and control. Facing out from the porch, residents survey (passively participate in) the shared space, with the house protecting the resident׳s back. At the same time, residents who use their porches present themselves visibly to their neighbors, potentially available for interaction. Every time BKF sat on his porch and somebody passed by on the sidewalk, at least a few neighborly words were exchanged. And, if BKF liked, he could go out into the shared space and join whatever activity was going on there.

|

|

|

Figure 5. View from a townhouse porch into the shared space. |

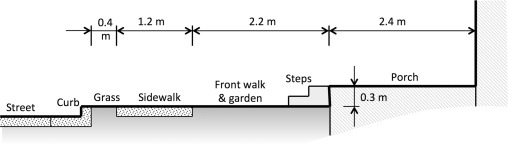

Marcus and Sarkissian (1986 , pp. 39 and 76–79) had recommended that a porch׳s distance to the public walkway should be large enough to avoid intrusiveness, and small enough to allow easy communication when it is desired, but did not cite specific dimensions that would achieve that. Since this site׳s porches and other edge features were found successful in these roles, their dimensions are given in Figure 6 . The porch is within talking distance of the sidewalk, horizontally and vertically. The boundaries between shared and private spaces are clear: progressing from the shared street and sidewalk are front walk and garden (grass and low shrubs), then two steps up, then the semiprivate porch, before the front door to the completely private interior.

|

|

|

Figure 6. Specific dimensions between townhouses and shared space. |

The site׳s back lanes make an absolutely different presentation to the public, although the same houses line them as on the front, and the same families live inside. A house, like a person, has a front and a back. A “back” is utilitarian and socially sacrificed; it is not a symbol of availability for social participation.

This study׳s discovery of a neighborhood-based community which made no significant use of the shared outdoor space raises the question of whether a neighborhood׳s architectural attributes have some role in the formation of such communities, even without being used for physical activity. For further study the hypothesis is offered that to make a neighborhood look in culturally recognized ways like it is lived-in and cared-for, might be as important to identity of some resident communities as outdoor personal interaction is to others.

Acknowledgment

Some of the work reported in this paper was done at the University of Georgia, Athens, Ga., where one of the co-authors (Bruce K. Ferguson) was formerly Franklin Professor of Landscape Architecture and Director of the School of Environmental Design.

References

- Almgren, 2001 Almgren, G., 2001. Community. In: Encyclopedia of Sociology (2nd edition). Mcmillan Reference USA, New York. Vol. 1, pp. 362–369.

- Appleyard and Lintell, 1972 D. Appleyard, M. Lintell; The environmental quality of city streets: the residents׳ viewpoint; J. Am. Inst. Plan., 38 (1972), pp. 84–101 Subsequently republished a number of times

- Brower, 2011 S. Brower; Neighbors and Neighborhoods: Elements of Successful Community Design, American Planning Association, Chicago (2011)

- Chaskin, 1997 R.J. Chaskin; Perspectives on neighborhood and community: a review; Soc. Serv. Rev., 71 (1997), pp. 521–547

- Coleman, 1988 J. Coleman; Social capital in the creation of human capital; Am. J. Sociol., 94 (1988), pp. S95–S120

- Coley et al., 1997 R.L. Coley, F.E. Kuo, W.C. Sullivan; Where does community grow? The social context created by nature in public housing; Environ. Behav., 29 (1997), pp. 468–494

- Farahani and Lozanovska, 2014 L. Farahani, M. Lozanovska; A framework for exploring the sense of community and social life in residential environments; ArchNet – Int. J. Arch. Res., 8 (2014), pp. 223–237

- Gehl, 2010 J. Gehl; Cities for People, Island Press, Washington (2010)

- Gehl, 2011 J. Gehl; Life Between Buildings; Island Press, Washington (2011)

- Gehl and Svarre, 2013 J. Gehl, B. Svarre; How to Study Public Life; Island Press, Washington (2013)

- Grannis, 2009 R. Grannis; From the Ground Up: Translating Geography into Community through Neighbor Networks; Princeton University Press, Princeton (2009)

- Gutman, 1966 R. Gutman; Site planning and social behavior; J. Soc. Issues, 22 (1966), pp. 103–115

- Holtan et al., 2015 M.T. Holtan, S.L. Dieterien, W.C. Sullivan; Social life under cover: tree canopy and social capital in Baltimore, Maryland; Environ. Behav., 47 (2015), pp. 502–525

- Karner, 2001 Karner, T.X., 2001. Social capital. In: Encyclopedia of Sociology (2nd edition). Macmillan Reference, New York. Vol. 4, pp. 2637–2641.

- Marcus, 2003 C.C. Marcus; Shared outdoor spaces; D. Watson, A. Plattus, R.G. Shibley (Eds.), Time-Saver Standards for Urban Design, McGraw-HIll, New York (2003), p. 6.9.1 to 6.9.12

- Marcus and Sarkissian, 1986 C.C. Marcus, W. Sarkissian; Housing as if People Mattered: Site Design Guidelines for Medium-Density Family Housing; University of California Press, Berkeley (1986)

- McMillan and Chavis, 1986 D.W. McMillan, D.M. Chavis; Sense of community; J. Community Psychol., 24 (1986), pp. 315–325

- Oldenburg, 1997 R. Oldenburg; Our vanishing “third places”; Plan. Comm. J., 25 (1997), pp. 6–10

- Putnam, 2001 R. Putnam; Social capital: measurement and consequences; Isuma: Can. J. Policy Res., 2 (2001), pp. 41–51 Retrieved from oecd.org 14 July 2015

- Wellman, 1996 B. Wellman; Are personal communities local? A dumptarian reconsideration; Soc. Netw., 18 (1996), pp. 347–354

- Wilkerson et al., 2012 A. Wilkerson, N.E. Carlson, I.H. Yen, Y.L. Michael; Neighborhood physical features and relationships with neighbors: does positive physical environment increase neighborliness?; Environ. Behav., 44 (2012), pp. 595–615

- Wilson, 2012 W.J. Wilson; The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy (2nd ed.), University of Chicago Press, Chicago (2012)

- Wilson-Doenges, 2001 G. Wilson-Doenges; Push and pull forces away from front porch use; Environ. Behav., 33 (2001), pp. 264–278

Document information

Published on 21/07/16

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?