1. Introduction

In the context of the growing ecological and economic consideration of sustainability aspects, attention is increasingly focussing on the topic of energy. This article only considers electrical energy though aspects of it certainly also apply to other energy types. Rising energy prices and binding regulations for future climate targets make it necessary to evaluate existing industrial systems and design new processes efficiently. To this end, it is necessary to improve knowledge about existing systems and thus be able to make a quantified statement about the current status. This thesis describes an approach for measuring and interpreting electrical indicators.

The presented approach gives advice for brownfield quantification and optimization due to systematical measurement and contextualization. The knowledge gained is beneficial for new applications and technologies in a wide range of industries.The basis for this is a measurement concept consisting of mobile and static sensors in a common architecture and the evaluation of the data using a materiality-based matrix and an efficiency indicator. This approach can be used generically for electrical power and energy. The approach was developed and validated as part of the production of composite structures for the aviation industry with focus on a structural test part out of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Plastics (CFRP). The motivation is to increase the efficiency of technologies in the context of lightweight solutions.

2. Economic and Ecologic Context

In 2022, the energy cost in Europe saw a significant increase in cost and fluctuations. Since then, the EU has committed to more renewable energy via the Fit-for-55 EU [1] policy package and the RepowerEU plan [2,3]. Achieving significant CO2 emission reduction from electric energy, necessitates not only the growth of renewable energy but also the optimization of energy demands. Especially patterns and timings of energy intensive processes can contribute, for example energy intensive heating and cooling processes could be carried out when renewable energy is available. An international standard to optimize the energy demand and to manage complex energy systems is the ISO 50001[4]. It provides organizations with a framework for the implementation and improvement of energy management systems. The ambition is to improve energy efficiency, reduce energy costs, and minimize environmental impact through systematic approaches and continuous improvement.

Relevant is also the ISO 14040 Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) standard [5] to evaluate a product's sustainability. The LCA provides a holistic framework for evaluating impacts of products on multiple sustainability indicators throughout the whole lifecycle. It can be a basis for reducing the environmental footprint of a product and comparing products. It is the basis for the Environmental Footprint method proposed by the EU.

Based on the EU Green Deal [6] regulations for sustainability are shaping the future of energy practices. Recently the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation foresees the definition of sustainability requirements as well as the implementation of a digital product passport [7]. To provide sustainability data of a product's manufacturing phase for a digital product passport and to reduce its environmental impact, the carbon footprint has to be calculated which needs energy measurements. To attribute measured energy to a specific product the data needs to be correlated with production / process information. Only by correlating the information such as the beginning and end of a process can the energy needed to produce a specific product be known. For products produced in complex industrial systems today both information are not readily available or are stored in databases [8].

3. Integrated Measurement Approach

This article will explore the potential of relating energy production information. Firstly, mobile and static energy measurements as well as the common framework for handling production data, the Automation Pyramid, are introduced.

Mobile energy measurements are designed to provide flexibility, they are portable and can be used ad-hoc for energy monitoring across variable conditions and locations. They can be used to analyze complex systems ranging from a building to a machine and its components. Especially when there are little or no static energy measurements available. Static Energy Measurements are fixed installations within an energy infrastructure, for example inside electrical cabinets and energy distribution systems. They are used to meter energy consumption and provide data on variations in baseline energy consumption, identifying inefficiencies, and they support compliance with international standards such as ISO 50001. They are needed for long-term energy management and optimization strategies. While mobile energy measurements excel in flexibility, static measurements provide consistent, long-term data. They complement each enabling organizations to form a comprehensive energy measurement and management strategy. A comparison between mobile and static energy measurements is illustrated in Table 1 as an overview.

| Mobile Energy Measurements | Static Energy Measurements | |

| Deployment | Rapid, flexible deployment across different locations | Fixed installations with permanent monitoring setups |

| Data Acquisition | Short-term, situational data | Long-term data capturing trends |

| Scalability | Limited because measurements are ad-hoc and often unique | Scalable with integration in centralized systems and databases |

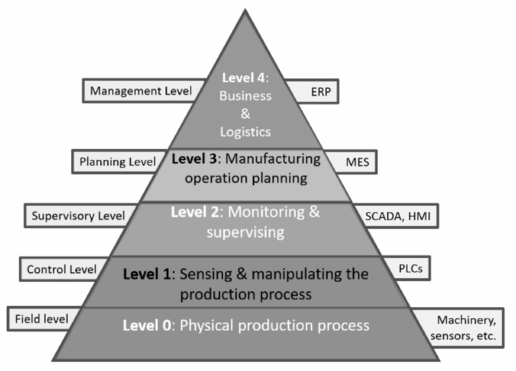

The Automation Pyramid (see Figure 1) is a layered framework for handling data and information flows in complex industrial systems. Each layer plays a distinct role in ensuring that data flows between the field, i.e. the shop floor and the top-level enterprise planning.

- Layer 1: Field

- Data acquisition and execution of actions.

- Layer 2: Programmable Logic Controllers (PLC)

- Execution of specific, local control and automation tasks at the equipment

- Layer 3: Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA)

- Monitor and control system operations incl visualizations, alarm handling and data logging.

- Level 4: Manufacturing Execution Systems (MES)

- Management of production planning, resource allocation and workflow execution as well as performance analysis.

- Level 5: Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP)

- Strategic decision-making, resource, finance and overall business management.

The integration of energy measurements into the automation pyramid allows for information to flow between Layer 1 and 5 and to connect energy data with production data. Mobile measurements can be used to optimize energy consumption by improving processes on a PLC level. Static measurements can be integrated on the field level as part of the framework. The data they provide can then be aggregated and processed on the SCADA, MES and ERP Level. Aggregated energy data has many used on the different levels for example:

- On SCADA Level data can for example be used to provide product specific data for future product passports,

- On MES Level it can be used to adjust operations in line with energy availability and consumption trends and

- The ERP Level leverages energy data for strategic planning.

In general, the integration of energy measurements in the automation pyramid enables an optimization of the energy system in line with ISO 50001, organizations can achieve a holistic approach to energy management, enhancing both performance and sustainability.

4. Power Materiality Matrix

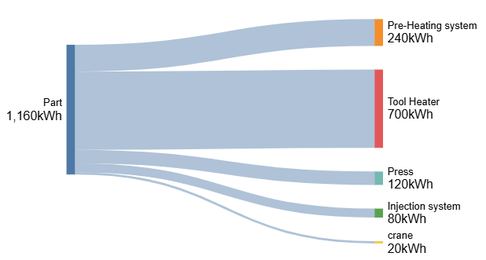

In order to be able to evaluate electrical power-related measurement data along defined boundary conditions, it is necessary to contextualise them. At an abstract level, it is necessary to describe the value chain in terms of electrical power drivers. Sankey diagrams (see Figure 2) are already widely used for the actual energy flows and ratios [10 and 11]. This is particularly suitable when it comes to visualising energy flows and understanding whether certain energy requirements are not yet being measured or analysed. For the design and planning of a building conversion or new construction, the maximum power is always specified in relation to a simultaneity factor. This simultaneity factor describes how many systems are used in parallel in order to determine the maximum required electrical power for the building. This shows the need for knowledge of the specific power requirement for the electrical grid and its planning [12 and 13].

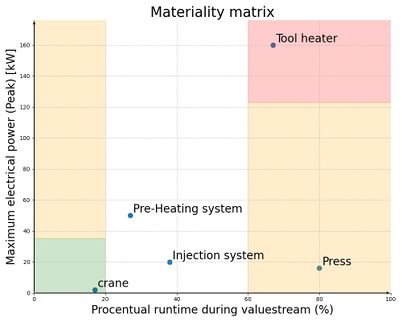

This information is also necessary for the evaluation of efficiency data. New approaches are required in order to split the data in terms of their maximum power and temporal distribution within the process. This is necessary because general energy information is not specific enough for efficiency rating. An approach based on a materiality matrix is chosen for this purpose. The maximum performance of a system is shown in relation to the percentage operating time in relation to the overall process.

The consideration of materiality comes from the area of environment analysis and company analysis. Here it is used to derive strategies in terms of their importance and thus enable prioritisation. The advantage is that different levels can be placed in context with each other. For a holistic ecological view of electrical energy, it is necessary to determine certain parameters. In addition to the flow of the electrical power, it is necessary to determine the maximum power of a system and the operating state. This information in relation to the actual measured physical variables (time and electrical power) is visualised directly in a diagram and shows which machines have a particular influence in terms of time of usage or electrical power.

The necessary data can be collected using suitable measurement systems and process analyses. As already described, a mobile or fixed approach can be chosen for measuring electrical power. The data can then be digitally processed and contextualized to provide a direct statement about the operating status and the associated power requirements.

The approach presented here refers to similar content as an Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE) analysis, but it has a differentiation by extending the information to include performance of the electrical power system. By linking nominal power requirement and process times for the specific systems (Table 2) the basis for the analysis is created. The energy productivity, defined as added cost value (€) in relation to energy consumption (kWh), can be evaluated by coupling this information with the specific value stream of the system during the specific process steps. The approach is usable for micro, meso and macro analysis and the boundary conditions depend on the use case.

For this validation the process itself with the specific systems sets the boundary conditions, a resin transfer moulding (RTM) process was used for the actual validation process. The component is a typical structural test component in aircraft construction. The process can be generalised as follows: The two-part mould is heated in the press to ensure homogeneous heat distribution. In parallel, additional tool parts are heated in a preheating station and then inserted into the hot tool together with the carbon fibre using a crane. The entire setup is then heated further to injection temperature and the resin is then infused using an injector. Once the injection is complete, the mould is heated further to the curing temperature and then cured. After the process, the component is removed by crane. As this is a research component with a large mould mass, the current cycle times are relatively high and not directly representative of an industrial series process.

| System | Nominal Power [kW] | Process Time [h] |

| Pre-Heating system | 50 | 04:00 |

| Tool heater | 160 | 08:00 |

| Press | 16 | 10:00 |

| Injection system | 20 | 05:00 |

| Crane | 2 | 02:00 |

The maximum electrical power output can be a temporary peak that occurs, for example, when the heating systems are started. This is necessary for the design of the electrical infrastructure and must be taken into account. In addition, this information is important for load shifting and planning methods in order to know exactly which processes consume high power.

The integral of the power over time describes the utilised energy of the system. Energy is viewed as an economic indicator, as this value is the basis for the cost charged by grid companies. The direct link between performance and percentage process time is particularly useful when specific attention areas (see Figure 3) are defined, this sets this visualisation apart from a standardised Sankey diagram. Figure 3 shows how the possible attention areas can be arranged in the materiality matrix. The areas are color-coded according to their criticality and potential for increasing energy efficiency, production rate, and integration of renewable energies.

The materiality matrix presented in Figure 3 serves as a critical analytical tool for energy assessment in CFRP manufacturing processes. This visualization maps the relationship between maximum electrical power (kW) and the percentage of runtime during the value-adding process cycle, enabling a systematic categorization of energy-consuming components based on their operational profiles. The matrix is divided into distinct regions characterized by varying levels of criticality.

In the green region (lower left quadrant), components such as the crane and partially the injection system exhibit both low power consumption and limited runtime during the value stream. These components contribute minimally to the overall energy consumption profile and connected load requirements, thus presenting limited opportunities for significant optimization outcomes. Per default the value is set up to 20% of the absolute value for both axes but the region can vary depending on the specific use case.

The orange regions warrant particular attention due to their specific operational characteristics. The left orange area encompasses systems with high maximum power output but relatively short runtime percentages, exemplified by the pre-heating system. These components significantly influence the connected load and transformer capacity requirements of the facility. Analysis of these systems reveals substantial potential for optimization through refined shutdown routines and standby logic implementation during non-value-adding periods. Such optimizations can effectively reduce infrastructure costs while maintaining process integrity.

Conversely, the right orange region contains systems characterized by lower power consumption but extended operational periods, such as the press system. These components are particularly relevant when considering cycle time increases and integration of renewable energy sources. Their predictable, extended operational profiles make them ideal candidates for load management strategies, including time-shifting and strategic energy supply planning, thereby facilitating effective integration into comprehensive energy management systems.

The red region (upper right quadrant) represents the most critical area of the matrix, where the tool heater is positioned. This region is defined by the challenging combination of high power consumption and prolonged runtime percentages, creating substantial constraints for process optimization. Systems in this category significantly impact total energy consumption, present limitations for cycle time improvements due to temporal constraints, and complicate renewable energy integration due to the combination of time limitations and substantial power demands. Consequently, components in this region necessitate prioritized attention in process optimization initiatives, factory planning, and process design considerations.

The materiality matrix methodology enables evidence-based prioritization of optimization measures in a wide range of processes. Components positioned in the red region merit highest priority assessment as they offer the greatest potential for energy savings and process improvement. Detailed analysis of the energy and temporal profiles of individual systems facilitates the identification of key components for energy efficiency measures, development of optimized control strategies for peak loads, integration of renewable energy sources through intelligent load management, and informed planning of connected load requirements and transformer capacities for new installations. This differentiated approach establishes the foundation for more sustainable and cost-efficient processes, where both energetic and process-specific parameters can be optimally aligned to achieve maximum efficiency and minimal environmental impact.

Continuous improvements can be visualised and integrated, because the axes of the diagram are dynamic, dependent on the absolute values of the individual systems, this results in an adaptive view. The visual representation can be automated and integrated into the automation pyramid, it can be used as an integrated solution with static sensors. For temporary and detailed analyses, mobile measurement systems can be used as additional data.

5. Conclusion

The energy-materiality matrix proposes a new approach in industrial process assessment. It combines energy usage and process information of industrial systems, enabling precise optimization of sustainability. In comparison to classical Sankey diagram analysis, which provides value for macro-analyses of energy flows, the materiality matrix offers a decision-oriented detailed perspective. The materiality matrix presented in this paper and the resulting quadrants represent a possibility for energy-adaptive process optimization.

In the current approach of materiality, only the primary conversion of electrical power/energy in the system is considered. If energy is reutilised during the process [14], this is not currently taken into account. Additional bidirectional fault lines could be considered here. These can show how the performance can be optimised through subsequent optimisations in the process.

In view of the description of Energy Performance Indicator (EnPIs) (ISO 50001), this approach offers a visualisation and prioritisation of optimisation potential. The approach described here will be expanded in future work by using a calculated factor. This describes the value of the specified points in terms of electrical power, energy, and active usage phase. This makes it possible to provide a concrete indicator in addition to the graphical solution and enables the direct quantification of the individual points within the materiality matrix.

In the future, the materiality matrix can be expanded by incorporating further levels of consideration. For example, an approach for evaluating the actual energy consumption in comparison to a best practice process could be used [15, 16]. This ratio would describe the efficiency and actuality of the system compared with a best practice and indicate further optimization potentials. This is particularly important for energy-intensive industries with long machine lifecycles such as aviation and aerospace industry and chemical companies. As a holistic approach to quantifying, contextualising and evaluating energy data in production, this approach is being further developed and offers the possibility of increasing efficiency in complex production systems for various industries.

6. References

[1] “Share of energy consumption from renewable sources in Europe,” European Environment Agency’s Home Page, Jan. 16, 2025. https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/share-of-energy-consumption-from

[2] Gawel, E., et al. (2023). REPowerEU: A critical assessment of the European Commission’s energy strategy. Energy Policy, 181, 113703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2023.113703

[3] European Commission, “State of the Energy Union 2022,” EUR-Lex. [Online]. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52022DC0547&qid=1666595113558. Accessed: Apr. 14, 2025.

[4] T.-Y. Chiu, S.-L. Lo und Y.-Y. Tsai, „Establishing an Integration-Energy-Practice Model for Improving Energy Performance Indicators in ISO 50001 Energy Management Systems“, Energies, Bd. 5, Nr. 12, S. 5324–5339, Dez. 2012, doi: 10.3390/en5125324.

[5] J. B. Guinée u. a., „Life Cycle Assessment: Past, Present, and Future“, Environmental Science & Technology, Bd. 45, Nr. 1, S. 90–96, Sep. 2010, doi: 10.1021/es101316v.

[6] European Commission, “The European Green Deal,” EUR-Lex. [Online]. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2019%3A640%3AFIN. Accessed: Apr. 14, 2025.

[7] Peña, C., et al. (2023). Digital product passports for a circular economy. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 27(3), 746-762. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.13370

[8] H. Diebler, „Energiemanagement in der Industrie“, Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftlichen Fabrikbetrieb, Bd. 111, Nr. 10, S. 633–634, Okt. 2016, doi: 10.3139/104.111596.

[9] E. M. Martinez, P. Ponce, I. Macias und A. Molina, „Automation Pyramid as Constructor for a Complete Digital Twin, Case Study: A Didactic Manufacturing System“, Sensors, Bd. 21, Nr. 14, S. 4656, Juli 2021, doi: 10.3390/s21144656.

[10] M. Schmidt, “The Sankey Diagram in Energy and Material Flow Management,” Journal of Industrial Ecology, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 173–185, Apr. 2008, doi: 10.1111/j.1530-9290.2008.00015.x.

[11] K. Soundararajan, H. K. Ho, and B. Su, “Sankey diagram framework for energy and exergy flows,” Applied Energy, vol. 136, pp. 1035–1042, Sep. 2014, doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2014.08.070.

[12] Low-voltage electrical installations – Part 100: Requirements for electrical installations, DIN VDE 0100-100, DKE, 2009.

[13] Electrical installations in residential buildings – Part 1: Planning principles, DIN 18015-1, DIN, 2020.

[14] J. Eckhoff, V. Adomat, C. Kober, M. Fette, R. Weidner, and J. P. Wulfsberg, “Towards a Framework for the Industrial Recommissioning of Residual Energy (IRRE): How to systematically evaluate and reclaim waste energy in manufacturing,” Machines, vol. 12, no. 9, p. 594, Aug. 2024, doi: 10.3390/machines12090594.

[15] G. Thiele, K. Grabowski, and J. Krüger, “Energieeffizienz in der intelligenten Fabrik,” Zeitschrift Für Wirtschaftlichen Fabrikbetrieb, vol. 114, no. 9, pp. 569–572, Sep. 2019, doi: 10.3139/104.112139.

[16] B. Karpuschewski, E. Kalhöfer, D. Joswig, and M. Rief, “Energiebedarf für die Hartmetallherstellung,” Zeitschrift Für Wirtschaftlichen Fabrikbetrieb, vol. 106, no. 7–8, pp. 496–501, Aug. 2011, doi: 10.3139/104.110599.

Document information

Accepted on 23/07/25

Submitted on 14/04/25

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?