1. Introduction

The industry has obtained a relative confidence in the numerical models for composite failure. However, the computational cost associated with available modelling methods represents a limitation for large structures. Delamination is the main failure mode leading to the necessity for a finer modelling, when compared to classical materials such as metals and polymers.

The modelling of delamination necessitates finer out-of-plane and in-plane discretisations. The out-of-plane discretisation, with at least 1 element per ply, is necessary to capture the out-of-plane stress driving delamination. The in-plane discretisation is a requirement associated with the use of cohesive elements representing the brittle behaviour of the delamination crack tip. Specifically, the cohesive elements need to be smaller than the interface fracture process zone, which is typically smaller than 1 mm. Additionally, the stable time increment for dynamic solvers is typically 5 to 10 times lower than that for metal structures due to the fine discretisation and introduced cohesive elements. Overall, the computational cost associated with composite delamination can be multiplied by 50 to 1000 (depending on the number of plies, ply thickness, interface properties, etc.) with respect to classical materials.

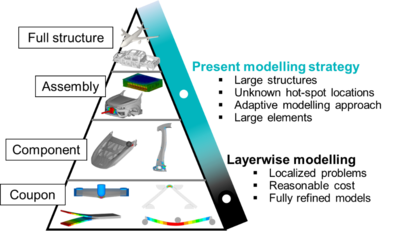

The present work showcases a novel strategy for the modelling of composite delamination. The objective is to reduce the computational cost such that delamination assessment can be integrated in the industrial development of large structures subjected to dynamic load cases, see Figure 1.

2. Model description

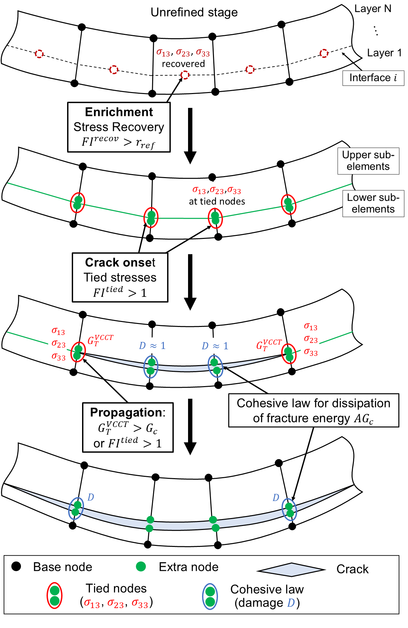

The strategy is based on an adaptive modelling framework minimizing the level of discretization [1, 2]. That is, the model starts in an unrefined state with a single through-the-thickness element representing the entire laminate. If and when a crack initiates, the model is enriched by introducing extra nodes to represent the displacement jump. Thus, the out-of-plane enrichment is limited to specific cracked interfaces in localised areas. Then, the use of an energy-based crack propagation criterion allows for comparatively large in-plane element length, from 2 to 5 mm, throughout the enrichment procedure.

The modelling strategy is illustrated in Figure 2. The model initiates with single solid-shell representing the thickness of the laminate. At predefined time intervals during the simulation, the out-of-plane stresses are accurately recovered across the laminate using a previously published method based on stress equilibrium equations [3]. An enrichment index is computed at each layer interface using

|

|

(1) |

where and are respectively the mode I and mode II strengths. The enrichment criterion is defined through

|

|

(2) |

where is an enrichment threshold. When the criterion is met at a layer interface, the model is enriched on the fly by adding extra node pairs at the corresponding interface throughout the laminate. The laminate is thereby split between the newly defined lower and upper sub-elements. Upon enrichment, the new node pairs are tied together. The associated tied stresses are computed by summing the internal force contributions of the sub-elements below the interface at the tied node pair. Then, a nodal failure index is evaluated also using Equation (1). When the crack initiation criterion

|

|

(3) |

is triggered at a node pair, its tied constraint is released, and a nodal cohesive law is introduced. The cohesive law uses a novel formulation designed for large elements [4,5]. The cohesive law progressively releases the node pair while dissipating the fracture energy , where is the cracked area and is the critical fracture toughness. is estimated with the Benzeggagh-Kenane equation [6] with the mixed-mode ratio defined as

|

|

(4) |

After initiation of a crack, the propagation can be assessed with the Virtual Crack Closure Technique, extended for arbitrarily shaped delamination front [5]. The crack propagates when the energy release rate reaches the interface fracture toughness,

|

|

(5) |

While subsequent propagation through neighboring elements could be governed solely by the Virtual Crack Closure Technique, the stress-based criterion of Equation (3) is maintained in parallel. Thus, propagation is triggered at any node pair by the first of the two criteria Equation (3) or Equation (5) that is reached. The energy-based criterion presents the advantage to conserve accuracy even when the elements are larger than the fracture process zone, eliminating the need to capture the stress singularity at the crack tip. However, in case of large fracture process zones, an energy-based criterion relying on fracture toughness corresponding to stable propagation would appear more resistant compared to reality at propagation onset. Thus, it is convenient to also rely on the stress-based criterion in the cases where the elements are smaller than the fracture process zone. It is here emphasised that the actual energy dissipation associated with the crack propagation is always governed by the cohesive law. In that sense, the stress-based and energy-based propagation criteria are complementary. It is worth mentioning that when both criteria are met at the same time increment, priority is given to the energy-based criterion as the estimation of the mode-mixity is judged more accurate.

3. Numerical example

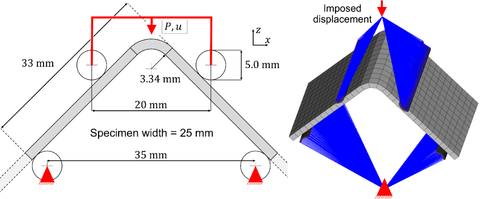

The modelling strategy is illustrated with the case of an L-shaped specimen unfolded by means of a 4-point bending test. The test has been carried out using the dimensions shown in Figure 3. Due to confidentiality reasons, the stacking sequence and material properties cannot be revealed. However, all the layers are made of the same unidirectional carbon-fibre reinforced polymer, and the laminate is highly disoriented such that around 67% of the layers are either 45º or -45º plies. The remaining layers are 90º (≈22%) or 0º (≈11%) plies.

The specimen is modelled with the novel modelling approach using an average in-plane element length of 2 mm, see Figure 3. The stress recovery procedure is applied every 100 time increments (12.1 μs based on the initial time step) and the enrichment threshold is set at . The Virtual Crack Closure Technique and the stress-based criterion are applied every 10 time increments (1.21 based on the initial time step).

Two configurations are used by varying an enforced minimum number of consecutive plies between enriched interfaces. In the first case (labelled 1REF), a minimum of 4 consecutive plies is enforced, resulting in a single interface to be enriched during the simulation. In the second case (labelled 2REF), a minimum of 2 consecutive plies is enforced, resulting in two interfaces to be enriched.

Conventional simulations using 0.5 mm and a 2 mm in-plane element sizes are performed to provide comparison. Based on layerwise modelling, a separate layer of elements is used for each laminate ply and conventional cohesive elements are introduced at each interface. The cohesive elements use a penalty stiffness associated to confidential interface strengths and fracture toughnesses. The 2 mm layerwise model does not meet the recommendation for cohesive elements to be smaller than the fracture process zone of the interface [7]. However, a layerwise model with a coarser in-plane mesh is often preferred in the industry due to the unbearable cost of finer modelling for large structures. Finally, a reference single layer model with no delamination modelling capabilities is made using the same 2 mm mesh as used by the novel modelling strategy.

In all the numerical models, the load is introduced through an imposed displacement of 5 mm applied progressively in the span of 20 ms. The outer part of the rollers is meshed with 0.5 mm solid elements with steel properties, , , and a density artificially increased to allow for larger stable time steps. A sliding contact with low Coulomb friction coefficient of 0.01 mimics the rollers free rotation.

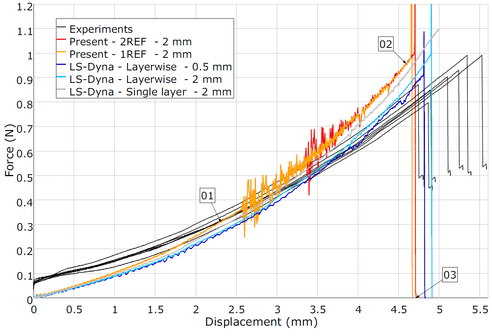

The force-displacement curves for the experiments and simulations are shown in Figure 4. The novel modelling strategy (red and orange curves) is able to capture the brittle collapse of the structure with a maximum force in the range of values observed in the experiments (black curves). The cases with a single and two adaptively enriched interfaces obtain similar results. Although the conventional 2 mm layerwise model (light blue curve) does not meet the recommendation for cohesive elements to be smaller than the fracture process zone of the interface, accurate results are obtained due to the test configuration producing a brittle failure where the structure collapses immediately after the strength-driven crack onset appears in the radius area.

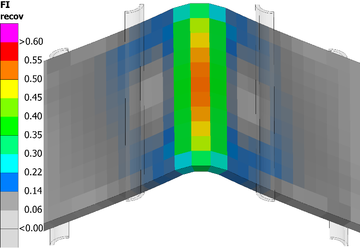

In the following, the enrichment and failure sequence for the 2REF case is explained referring to simulation states labelled with numbers in Figure 4. The first enrichment is triggered at a displacement of 2.56 mm. The field of enrichment index (elemental maximum over the interfaces) is shown in Figure 5 for the simulation state 01, prior to enrichment. The interface triggering this first enrichment is located slightly below the laminate middle surface, at the expected central element of the radius area. The second enrichment occurs at a displacement of 3.34 mm at an interface towards the inner radius of the specimen.

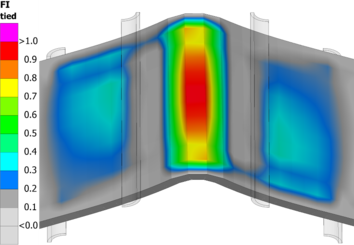

The brittle failure is predicted at a displacement of 4.70 mm. The crack onset is triggered under mode I failure at the first interface enriched. The field for the nodal failure index is presented in Figure 6 for this interface at the simulation state 02 (see Figure 4), prior to crack onset.

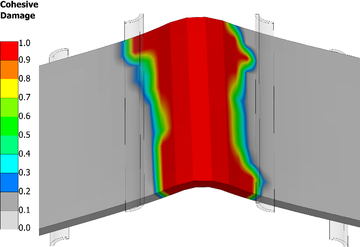

Immediately after crack onset, the brittle collapse of the structure leads to an unstable crack propagation. The simulation state 03 corresponds to the final extension of the crack, which is visible through the cohesive damage plot Figure 7. The crack onset is located at the centre of the radius area. Following the first opening node pairs, the Virtual Crack Closure Technique can be computed, propagating the crack up to the vicinity of the rollers. The second interface enriched, closer to the bottom surface of the laminate, does not reach crack nucleation. The enrichment and failure sequence are identical for the 1REF case, except for the second enrichment being prevented by the required minimum of 4 consecutive plies per sub-element.

Figure 5: Enrichment index (elemental maximum over the interfaces) prior to the first enrichment for the adaptive modelling strategy, corresponding to the simulation state 01 of the 2REF curve in Figure 4.

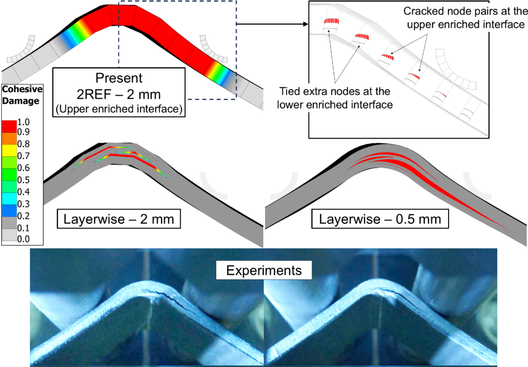

The resulting crack extension observed from the side of the specimen is compared between the experiments and the numerical models in Figure 8. A crack slightly below the laminate middle surface can be observed extending from the radius area to the contact point with the upper right roller. The 2 mm adaptive model presents a similar crack. The extra nodes of the two enriched interfaces are shown using transparency in the upper right image of Figure 8, showing the crack at the upper enriched interface. The 2 mm layerwise model shows several cracks in the radius area but none extend up to the right rollers. In that case, the large cohesive elements compared to the fracture process zone could affect the accuracy of the predicted crack propagation.

The computational times of the different numerical methods are compared in Table 1. The fine layerwise modelling is computationally costly due to the high number of degrees-of-freedom and small stable time step. This fine modelling is the current standard for accuracy-driven modelling. The present adaptive approach is order-of-magnitudes more efficient (about 26 times faster for the 1REF case) while maintaining accuracy.

The present strategy is also more efficient than the 2 mm layerwise model with identical in-plane discretisation. Thus, the novel method offers an efficient alternative while allowing for the accurate modelling of propagation in the case of element larger than the interface fracture process zone.

As a remark, caution must be exercised when extrapolating the computational gains to other problems. The efficiency gains of the novel approach are expected to vary significantly depending on factors such as the number of plies, the ply thickness, the in-plane discretisation and the enforced minimum number of consecutive plies per sub-element.

| Layerwise

0.5 mm |

Layerwise

2 mm |

Single layer1

2 mm |

Present

2REF 2 mm |

Present

1REF 2 mm | |

| Initial number of

degrees-of-freedom2 |

353,484 | 27,216 | 8,784 | 8,784 | 8,784 |

| Final number of

degrees-of-freedom2 |

353,484 | 27,216 | 8,784 | 13,392 | 11,088 |

| Number of

time increments |

640,787 | 530,680 | 186,498 | 231,115 | 171,876 |

| Computational time

[hrs:min:s] |

4:43:09 | 0:19:46 | 0:05:49 | 0:15:11 | 00:10:48 |

| 1No delamination modelling capabilities. | |||||

| 2The 0.5 mm mesh of the rollers accounts for 6,480 degrees-of-freedom that are included in the presented numbers. | |||||

4. Conclusions

The modelling of the L-shaped specimen represents a proof-of-concept for the novel modelling strategy. This example illustrates how the previously published out-of-plane stress recovery procedure [3] and energy release rate-based cohesive method [4,5] can be integrated into an adaptive approach to enable an orders-of-magnitude more efficient solution. A thorough validation of the method in large components is yet to be carried out. However, the formulated modelling strategy offers a promising solution for the efficient simulation of delamination in large structures, enabling more frequent simulations from component-level to full-scale models.

5. References

[1] J. Främby, M. Fagerström and J. Karlsson: An adaptive shell element for explicit dynamic analysis of failure in laminated composites Part 1: Adaptive kinematics and numerical implementation, Engineering Fracture Mechanics, 240, 2020, 107288.

[2] J. Främby and M. Fagerström: An adaptive shell element for explicit dynamic analysis of failure in laminated composites Part 2: Progressive failure and model validation, Engineering Fracture Mechanics, 244, 2021, 107364.

[3] P. Daniel, J. Främby, M. Fagerström and P. Maimí, Complete transverse stress recovery model for linear shell elements in arbitrarily curved laminates, Composite Structures, 252, 2020, 112675.

[4] P. Daniel, J. Främby, M. Fagerström and P. Maimí, An efficient ERR-Cohesive method for the modelling of delamination propagation with large elements, Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing, 165, 2023, 107423.

[5] P. Daniel, J. Främby, M. Fagerström and P. Maimí, A method for modelling arbitrarily shaped delamination fronts with large and distorted elements, Engineering Fracture Mechanics, 306, 2024, 110193.

[6] M. L. Benzeggagh and M. Kenane, Measurement of mixed-mode delamination fracture toughness of unidirectional glass/epoxy composites with mixed-mode bending apparatus, Composites Science and Technology, 56, 1996, 439–449.

[7] A. Turon, C. G. Dávila, P. P. Camanho, J. Costa, An engineering solution for mesh size effects in the simulation of delamination using cohesive zone models, Engineering Fracture Mechanics, 74, 2007, 1665–1682.

Document information

Accepted on 14/07/25

Submitted on 14/04/25

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?