Abstract

One of the objectives of the redevelopment project for Trajan׳s Market, which spanned from 2000 to 2002, was to rearrange the market׳s accessibility and the visiting paths that connect and cross the entire site. The purpose was to extensively expose its beauty and thus invite more tourists into the area. The project design consisted of a series of catwalks placed at different levels and was conceived with respect to three criteria: (1) the didactic significance of forms and materials; (2) the coherence between architectural forms, techniques, and materials with the identity of the place; and (3) the possibility of removing, if necessary, newly added elements without damaging the relics. The project also involved the rearrangement and reconstruction of the former “Giardino delle Milizie” (2002–2007) to allow public access to the archaeological stratification and to the ancient Roman street located at its bottom. Consequently, the vaults of the convent were suspended upon a system of steel beams, which, together with several wooden pillars, also support the glass roof of the space, offering a close view of the ancient Roman walls. The structure and architectural forms coincide, implying that each of these elements is necessary and genuine.

Keywords

Conservation ; Charters ; Place ; Palimpsest ; Heritage ; Trajan׳s Market

1. Architecture and such things: restoration works at Trajan׳s Market

1.1. Premise

The International Restoration Charter, also known as the Venice Charter, celebrated its 50th founding anniversary on May 31, 2014. The Charter was signed during the International Congress of Architects and Monuments Technicians. It is an international document establishing guidelines for the preservation and restoration of historical monuments and sites.

The numerous existing laws and codes that regulate the preservation of Italy were conceived because of the vast presence of archaeological sites and historical monuments within the country. The relevance of Italian contribution to the field of restoration and conservation is fully recognized by Cesare Brandi2 , who initiated critical restoration theory3 . In particular, this theory further applies the concepts and ideas introduced by Prof. Giovanni Carbonara within the postgraduate course on the Architectural Conservation of Sapienza University of Rome, also known as the “Scuola di Specializzazione in Beni Architettonici e del Paesaggio,” which was founded in 19574 .

A relevant issue in this field is the definition of the term “place,” which can be briefly characterized as a combination of material features that can either be natural or anthropic. These material features include the orography, vegetation, and water sources of a site, and even the bricks, stones, and wooden structures of buildings. Place may also be explained as a system of formal relations, which may involve colors, geometry, alignments, and relevant points. Each relationship is both objective and subjective, and is filtered by personal experience and analogical memory. Individual images and feelings may be conveyed in various manners, such as “the light of my grandfather׳s house,” “a book I have read,” “a film I saw,” “a place I liked,” and “a building I visited”. The inventory of objects constituting place or palimpsest5 must be filtered by personal experience.

In this regard, Louis Kahn wrote:

No object is entirely apart from its surroundings and, therefore, cannot be represented convincingly as a thing in itself; also the presence of our own individuality causes it to appear differently as it would to others… There is no value in trying to imitate exactly. Photographs will serve you best of all, if that is your aim. We should not imitate when our intention is to create – to improvise … I try in all my sketching not to be entirely subservient to my subject, but I have respect for it, and regard it as something tangible and alive from which to extract my feelings.

(Louis I Kahn. L’uomo. il maestro . By Alessandra Latour, Kappa ed.1986, Rome).

The current essay intends to analyze my two projects for the archeological area of Trajan׳s Market in Rome according to the aforementioned theoretical and historical contexts.

Some interventions emerged from structural issues, whereas others ensued from the gap between two orographic6 levels. All the works were designed according to the history and recollection of the place. In particular, the architect tried to understand and appropriately resolve the demands of the place.

A short note about the title: The title was contrived from the analogy with a book written by Heinrich Tessenow in 1916 entitled House-Buildings and Such Things. This particular document sets the guidelines for architecture, which was then understood as craft practice without any reference to style and language. Tessenow was mainly interested in construction, logic of design, and building as basic aims for the project. I agree with his assumptions that the final goal of an architect is to build, not draw, and that a designer׳s practice passes through this daily attention to craftsmanship.

2. International documents for preserving and restoring cultural heritage

Preservation and restoration charters are documents conceived in international agreement conferences and predominantly aim to establish guidelines for interventions on historical monuments7 . In particular, the charters on conserving cultural heritage established guidelines for key laws promulgated by many different countries and for all architects. Therefore, each international charter8 involves “abstract or general” principles that must be reconciled with the characteristics of ancient sites and interpreted by the sensibility of the designers. Meanwhile, the primary charters generally aim to prevent complete reconstructions, encourage anastylosis9 , respect the past without erasing any traditional style, and design novel interventions for promoting new technologies and materials while avoiding drastic changes to any historical artifact.

In this essay, two treaties are noted because of their importance in the modern conception of cultural heritage. The first is the “ Charter of Venice” (1964), which is the leading international agreement on preservation through which the urban environment and landscape are given cultural and historical value for the first time. The second is the “European Charter for the Historic Heritage,” which is the so-called Charter of Amsterdam (1975). This document extended the area of interest of preservation from the single monument to the urban context and throughout the entire fabric of the city. In this event, the term “integrated restoration” was introduced, indicating that historical knowledge, conservation, cultural behavior, and social benefits are interconnected. Such a rationale updated the concept of “monument,” which was considered an international asset. Accordingly, the resources for restoring monuments can be acquired from the international community, not only from the state in which ancient buildings or archeological sites are situated.

Today, we recognize the difficulty of establishing global measures for any situation. A design must be a flexible instrument that answers to different conditions and multidisciplinary approaches. Moreover, the relevance of efficiently managing cultural heritage should be acknowledged. The “value” of historical and artistic objects is not only remarkable in terms of one׳s knowledge and memory, but also concerns the role of these objects as possible sources of inaugurating societies and economies. Therefore, today׳s idea of preservation is connected to environmental damage (e.g., pollution, urban speculation, and tourism), which bargains economic advantages with the need to preserve historical monuments.

3. Place, context

Architecture is the making of a room; an assembly of rooms. The light is the light of that room. Thoughts exchanged by one and another are not the same in one room as in another. A street is a room; a community room by agreement. Its character from intersection to intersection changes and may be regarded as a number of rooms (Latour, 1986) .

The end or the beginning of a restoration project is the inclusion of buildings in the urban context , a Latin word composed of cum , which denotes together, and texto , which means fabric. Therefore, when referring to architecture, the word context does not only indicate a set of things around buildings (i.e., the sum of objects or materials, volumes, and colors), but also the relationship that exists between them. Context also includes “intangible” relationships, such as the memory and history of a specific urban context that transform geometrical spaces in palimpsest .

What is “place”? For an architect, place essentially refers to a 3D physical environment and pertains to the intersection of different morphological systems, including slope, surface, rock and water, and earth and sky. An architect identifies the geometrical sets that organize what the human senses perceive, such as an axis, alignment, and shape. Subsequently, pedestrian paths, vehicular roads, squares, and buildings are constructed. Place is also determined as equally real in spite of it being deemed as tangible or intangible. This particular rationale of place may be defined as the product of emotions and memories that the observer or designer acknowledges to a certain space due to its history, culture, symbols, or by analogy with other known sites.

4. Project for Trajan׳s Market: a short story

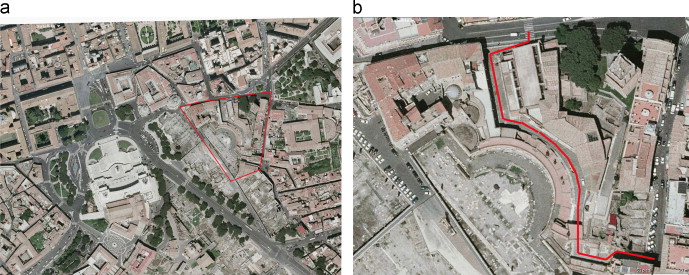

Trajan׳s Market is a large archeological complex within the city of Rome located on one side of Via dei Fori Imperiali, which connects Piazza Venezia and the Coliseum, and crosses the ruins of Rome׳s Imperial Fora [ Figure 1 a and b].

|

|

|

Figure 1. (a and b) Site of Trajan׳s Market within the historical center of Rome; Ancient Via Biberatica crossing the entire area. |

Trajan׳s Market was constructed between 100 AD and 110 AD and was inaugurated in 113 AD. This monumental historical structure was supposedly designed by Apollodorus of Damascus, a Greek architect of Trajan׳s retinue to whom the emperor entrusted the design of his Forum. The construction of this historical site was aimed to form a retaining wall against Quirinal Hill. Accordingly, the existing buildings and structures were nestled on the side of the hill forming an exaedra , a semicircular space, to support the ground.

During the Middle Ages, the complex was revolutionized with the addition of floor levels and the construction of military sites, such as the Torre delle Milizie (the Tower of the Militia), which was built in the 20th century. A convent dedicated to St. Catherine was later assembled between 1620 and 1641, but was demolished in 1930 during the Fascist regime to restore the imperial idea of Rome.

Archaeologists initially considered the structures of Trajan׳s Market as a retail space, though recent research suggests that the multilevel structure housed the administrative offices of Trajan׳s empire.

In any case, the site has witnessed large-scale changes with the development of the city from the imperial age to the present day, constantly being reused and transformed. In particular, the site has been used as a strategic administrative center of the Imperial Fora, noble residence, military fortress, prestigious convent, and military barrack. Trajan׳s Market has undergone a continuous process of urban evolution, in which each architecture has changed. All traces of these different historical phases are still visible.

Today, Trajan׳s Market houses the Museum of Rome׳s Imperial Fora[Figure 2] .

|

|

|

Figure 2. Area of Trajan׳s Forum around the Giardino delle Milizie during demolitions in the 1930 s. |

5. Aims, criteria, and references of the project

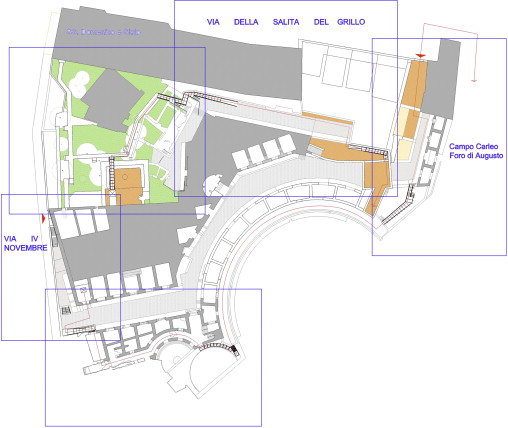

The primary goal of the project was to provide access to the spaces of Trajan׳s Market, with respect to the existing laws, and to significantly reduce the architectural barriers along the paths that represent the connective tissue of the archaeological area and the site׳s orography [ Figure 3 ]. This particular design strategy was preferred to restore the original pavements of the site and to obtain flat and smooth surfaces, with specific solutions identified for each situation and requirement. The results of the design process must be carefully coordinated with regard to the homogeneity of materials and the construction techniques to maintain the integrity of the archaeological landscape in terms of colors, different alignments, and perspectives. Each new intervention, either for architectural or preservation concerns, has been designed according to the below principles.

- Clear distinction of the new additions placed upon the archaeological or historical substratum to avoid confusion among different historical layers.

- “Minimal intervention” approach to provide new elements only if strictly necessary for preserving or restoring the original walls and pavements, while providing an access to the different levels of the monument.

- Reversible systems to make every new intervention removable, unless critically essential for structural or conservation issues.

|

|

|

Figure 3. Plan of the interventions. |

The place or palimpsest of Trajan׳s Market was the main reference for the project in terms of urban context and neighboring buildings. The secondary reference was the archeological system of the existing axes, alignments, materials, colors, and volumes. The archeological ruins still underground were also considered in outlining the project. In this event, emerging lines were engraved on the pavement to show the underlying structures. With regard to the orography of the site, different catwalks made of steel and wood were designed to bridge the gaps between different levels. These catwalks could be easily removed when necessary. Meanwhile, the architectural details by Carlo Scarpa and Danilo Guerri 10 were kept as a design reference. The memory of the former walls, today ruins, also suggested the idea of using wooden carpentry during the construction. In this case, the structures in steel and wood were explicitly designed to show their mechanical and temporary nature. In this process, a relationship with Piranesi׳s drawings was implied, particularly the etchings of The Prisons , which clearly exhibits techniques and materials ( Piranesi, 1975 ).

6. Archeological parterre

These interventions were realized to accomplish three main purposes; specifically, to conserve the original pavements, to make the archaeological parterre accessible to visitors and propose the idea of original spaces both inside and outside, and to reveal the underlying traces and alignments of the original structures. Based on these principles, the restoration of the pavement in the area of “Piccolo Emiciclo” was designed, and the uneven alignment of the “basolato” (the large rounded flint stones used by the Romans to pave streets; the road pavements made by the Romans were approximately 50–60 cm wide) along the sidewalk of Via Biberatica was adjusted. These projects were realized to restore the original inside–outside conditions of the large space toward Via Salita del Grillo. Three pavement typologies were then adopted to complete the archaeological soil. One typology was made with small fragments of basalt to integrate the “basolato” pathways with elements of the same color and material, but with different dimensions. Such a technique was used to reveal the exterior spaces. The second and third types of pavement were constructed with fragmented bricks that have two different dimensions. The larger dimensions (circa 7–10 cm wide) were employed to underline the alignments with the Roman walls that still exist under the floor surface. Meanwhile, the smaller brick fragments were used to fill the original pavement areas and to show the interiors of the archeological buildings.

Drawings, materials, and construction techniques were designed according to the existing colors and archeological materials, as well as respected previous restoration works dating back to the 1930 s. These works are now part of the historical and contemporary landscape of Trajan׳s Market.

The new pavements were conceived with the concept of “neutral” reintegration expressed by Cesare Brandi11 and Roberto Pane12 , and were envisioned according to the teachings of Paul Philippot13 , the former director of ICCROM14 . This particular condition signifies that all interventions on the archaeological parterre were realized to protect the Roman ruins and to construct comfortable paths for visitors without any modern decorative or stylistic design.

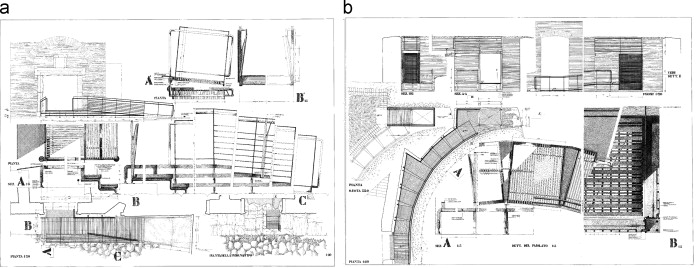

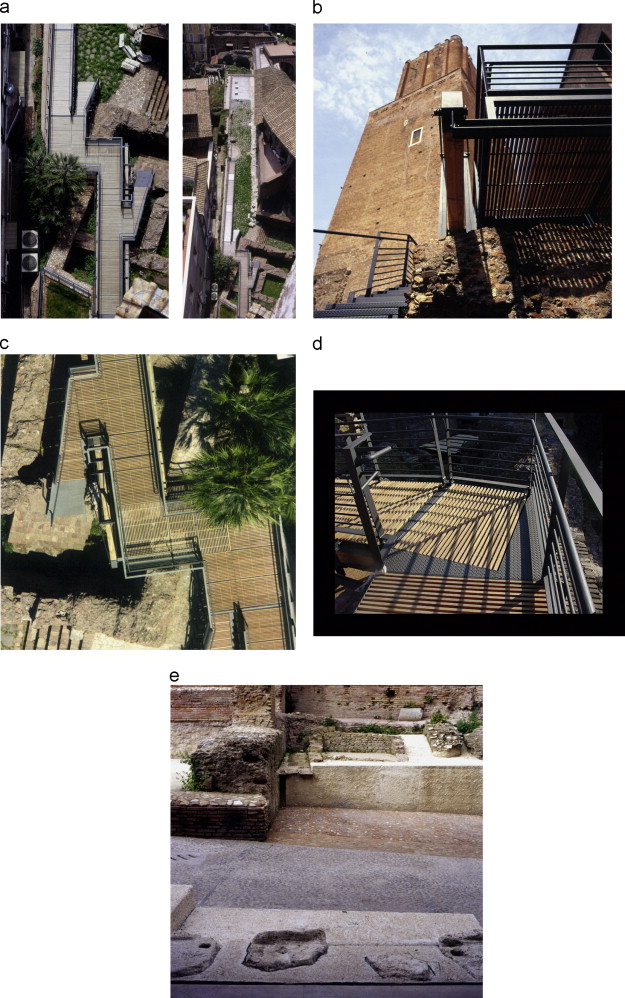

7. Barrier removal elements

The interventions for removing architectural barriers were completed under Italian legal obligations15 because of the public nature of the site. Despite the functional role that different solutions have in the archaeological context, the elements designed to remove these barriers became part of the image of the place, thereby transforming the original landscape. Different typologies of catwalks were designed in accordance with the orography and alignments of the site [ Figure 4 a–c]. The relation between the archeological ruins and the memory of the Roman building were conveyed by the idea of using mechanical details in steel and wood, which were the materials that existed at the time when Trajan׳s Market was built. The structural design of the catwalks was intended to be clearly expressed with the use of asymmetrical steel consisting of reinforced wooden beams, hinges, and supports, with nuts and bolts for railings. The asymmetry also endeavors to determine different foundation possibilities and to offer various perspectives from multiple sides [ Figure 5 a–e]. The catwalk floors were designed to be transparent, allowing tourists to view the archaeological ruins below, creating a pattern of wooden lathes alternately arranged with empty spaces of the same size. When a change in direction was necessary, metal sheets were used so that the rotation was compatible with the rigidity of the wooden floors [ Figure 6 a–c].

|

|

|

Figure 4. (a and b) Schematics of the catwalks, ramps, and stairs along the visiting path. |

|

|

|

Figure 5. (a–e) Catwalk along Via della Torre as seen from above; Transparency of the walking surfaces as seen from below; Details of the structure and the new paving. |

|

|

|

Figure 6. (a–c) New paving of the visiting path between Via Biberatica and Salita del Grillo; Materials used to connect the new structures and archaeological relics. |

All the above mechanisms emphasize the temporary nature of the modern structures, which are not only completely removable, without any aggressive support inserted into the Roman walls, but are clearly temporary as wooden structures. Moreover, the catwalks were assembled with a didactic function to solve the issue of mobility in the area. In particular, the alignments of these catwalks were planned to underscore specific views and archeological remains that have been kept in situ .

8. Works at the Giardino delle Milizie

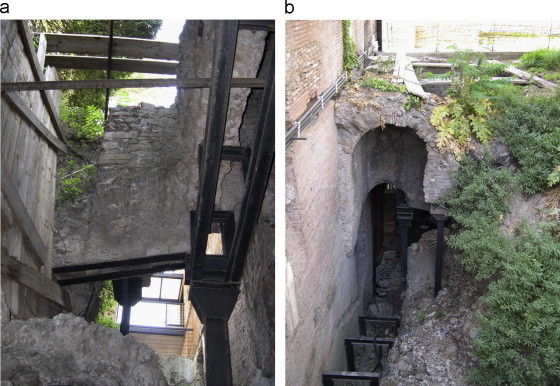

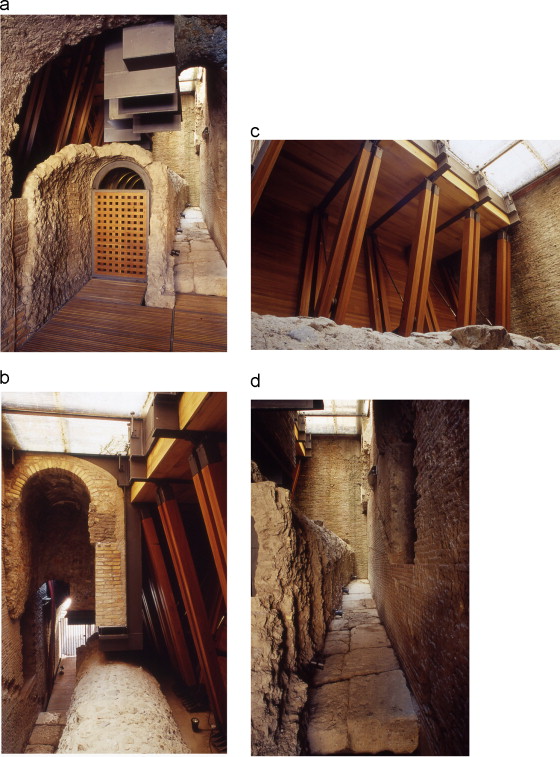

The Giardino delle Milizie (Militia Garden) is a space resulting from demolitions conducted in 1919 and between 1926 and 1934. This site was also developed from archeological excavations during the 1980 s and 1990 s. Behind the eastern elevation of the “Grande Aula,” which is the main entrance to the complex and, today, the Museum of the Imperial Fora , a large cavity about 6 m-deep that contained the ruins of the convent of St. Caterina was observed and was, therefore, saved by the Fascist demolitions [ Figure 7 a–d]. The hypogeal ruins consisted of two sections of vaulted arches, which were once placed to cover a Renaissance road, and a vaulted corridor, which was part of an abandoned convent. Meanwhile, a pavement made of thick slabs of travertine (about 20–25 cm) was discovered in the space between the vaulted corridor and the ancient masonry. This pavement, dating back to the reign of Trajan, witnessed the level of the original Roman building and, consequently, the original elevation of Trajan׳s Market. Such an elevation was difficult to identify because two large 17th-century cisterns were directly placed upon the original Roman foundations in front of the main façade of the building [ Figure 8 a and b].

|

|

|

Figure 7. (a–d) Catwalk within the Giardino delle Milizie as seen from above; Details of the load-bearing structure. |

|

|

|

Figure 8. (a and b) Hypogeal space within the Giardino delle Milizie prior to the reconstruction projects. |

The project was designed to redefine the excavation area by building a retaining wall against the ground. In particular, the opposite of the “lightness” of the new wooden structure, pillars, and planking revealed the modern difficulty of constructing a new structure in that place. The reasons behind this limitation are the narrowness of the foundation level and the probable presence of archaeological remains underneath.

In this context, the project aimed to resolve three main issues: to retain the ground slope obtained after the excavations, to make the hypogeal space safe for visitors, and to show the ruins of Trajan׳s travertine pavement still in place. The design for consolidating the 17th-century structures was based on the observation that it was impossible to either reduce or introduce structural loads on the vertical plane of the original foundation. Hence, the modern structures were designed to redirect the weight mainly against the new retaining wall. This same reason was applied in designing the wooden pillars as a “V” system, each reinforced with a steel tie rod and strut.

The ancient vaults were suspended. The steel beams were curved to offer structural resistance along the original alignments of the vaults. All the vaults, two major and one minor, were organically reconnected to maintain a formal and structural unity for restoring the original spatial quality and for distinguishing the stratified history of the place. Clearly, the structures in this project do not simply support the weights. In fact, these structures contribute to the architectural image of the entire site and define the modern space close to the archaeological structures while avoiding direct contact.

Another purpose of the design was to clarify the new space as a hypogeal one with natural light coming from above. For this reason, the new wooden lathe floor on the garden level was kept about 200 cm away from the Roman wall. In such a gap, a designed skylight offers a view from below onto the garden outside and, vice versa, a view from above onto the ancient Roman street. As previously mentioned, wood and steel were the materials employed for the project to describe the modernity and temporary status of the interventions [ Figure 9 a–d].

|

|

|

Figure 9. (a–d) Novel arrangement of hypogeal space within the Giardino delle Milizie: the access, load-bearing structure, and vaults; Pillars and skylight; Characteristics of the street during Trajan׳s reign arising among the layers of historical stratification. |

9. Conclusions according to the “Charter of Venice”

The works on Trajan׳s Market were achieved according to the main principles of the 1964 Charter of Venice. In particular, certain relevant paragraphs in the charter states that the new accessibility of the archaeological complex increased the number of visitors while avoiding any alteration of the excavations (paragraph no. 5). The project “did not allow any new construction, destruction or use that could alter relations among volumes and colours” (paragraph no. 6). Context and history were used as the precedents of our project with respect to the “spirit of the place”; the new design for conserving this monument included environmental preservations (paragraph no. 7). The restoration was ended “at the point where hypotheses started.” Each new inserted element was also designed to be recognizable from the original layers (paragraph no. 9). Traditional construction techniques were used in terms of materials, colors, and memory (paragraph no. 10). Removing any of the existing historical layers was not feasible because “the stylistic homogeneity is not the proper scope of restoration … when it is possible to see different historic layers on the same building … the judgement of their value cannot be decided only by the design author” (paragraph no. 11). The elements used to replace the lost pieces were carefully integrated, “distinguishing the new elements from the original ones in order not to falsify the monument and respect both the aesthetic and the historic value” (paragraph no. 12).

In conclusion, according to the principles stated by the “Charter of Venice,” new elements should not be added to Trajan׳s Market if not strictly required for structural, aesthetic, or conservation reasons. In any case, new insertions must always be recognizable to allow conservation and to re-establish the continuity of forms, colors, and form of the monument.

Accessibility is what the site currently needs to exhibit its archeological remains and organize paths open to tourists and visitors, thus providing them with historical information and expanding their cultural understanding and architectural sensibility.

The palimpsest of Trajan׳s Market refers to the archeological site and urban context, the observation of the historical relationships of different objects, and the inventory of remains, monuments, paths, new buildings, and spaces. All these elements must be jointly considered as an organic combination that should always be recognized as a place .

References

- Latour, 1986 Latour A., 1986. Louis I Kahn. L׳uomo. Il maestro, Rome.

- Piranesi, 1975 Piranesi G.B. 1975. Carceri d’invenzione. In: Praz, M. (Ed.). Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Le carceri. Rizzoli, Milano, pp. 1745–1761.

Notes

2. Cesare Brandi was born in Siena on April 8, 1906, and died in Vignano on January 19, 1988.

3. We recall Roberto Pane (Naples), Renato Bonelli (Rome), and Cesare Brandi (Siena) as the main theorists of critical restoration. The latter defines restoration as “The methodological moment of recognition of the work of art in its physical form and its dual aesthetic and historical polarity, in view of its transmission to the future.”

4. Giovanni Carbonara was the director of the institution until November 2013. He stated that, “Any intervention seeking to preserve and pass on to the future ancient and archeological traces is understood as Restoration : it is based on the respect for original material and authentic documents. Restoration is also a non-verbal critical interpretations expressed in concrete ways.”

5. A palimpsest is a manuscript, scroll, or page of a book that has been scraped or washed off to be used again. Its root word is Greek and is composed of πάλιν (again) and ψάω (to scrape), which mean “scraped, clean, and used again.” This rationale does not only imply the action to erase, but also to understand and decide what can or must be erased and what should be maintained.

6. The root word of this term is Greek and is composed of όρος (hill) and γραφία (to write), referring to the intent to study the territory׳s relief.

7. The term monument comes from the Latin verb moneo , which means “I remember.”

8. The main charters are the International Charter for Restoration, which is the so-called Charter of Athens, 1931; the Italian Charter of Restoration, 1932; the International Charter of Restoration, called the “Charter of Venice,” 1964; the European Charter for the Historic Heritage, also known as the “Charter of Amsterdam,” 1975; the International Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas, also called the “Washington Declaration,” 1987; and the Principles for Conservation and Restoration of Built Heritage, the so-called Charter of Kracow, 2000.

9. It originates from the Greek word άναστήλωσις, which signifies “back into a standing position.”

10. Carlo Scarpa (1906–1978) and Danilo Guerri (1939).

11. Cesare Brandi (Siena, April 8, 1906–Vignano, January 19, 1988) was an Italian art historian, art critic, and essayist; he was also a specialist in the theory of restoration.

12. Roberto Pane (Taranto, November 21, 1897–Sorrento, July 29, 1987) was an Italian architect and architectural historian.

13. Paul Philippot (Bruxelles, Belgium, 1925) became the vice director for ICCROM in 1958 and was the director between 1971 and 1977. He met Cesare Brandi in Rome and collaborated with him for the Restoration Central Institute and the High School of Monument Preservation.

14. The International Centre for the Study of Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property was conceived by UNESCO to promote the conservation of monuments and sites of historical, artistic, and archaeological interest; ICCROM is an intergovernmental organization (IGO) dedicated to conserving cultural heritage. It exists to serve the international community as represented by its current 132 member states.

15. These are the main Italian Laws on the matter at hand: n. 13/1989, n. 104 del 1992, and D.P.R. n. 503/1996

Document information

Published on 12/05/17

Submitted on 12/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?