Summary

Background/Objective

Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILC) is emerging as an alternative to standard four-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (4ILC). This study presents one surgeons experience of SILC and a retrospective analysis of the data.

Methods

Sixty-seven consecutive patients treated by a single surgeon and undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) for benign gallbladder diseases were enrolled. LCs were attempted with conventional instruments as follows: 24 three-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomies (3ILC); 10 two-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomies (2ILC); and 33 SILC.

Results

The procedure conversion rate into the SILC, 2ILC, and 3ILC groups was 9.1%, 0%, and 8.3% respectively. Operative time was significantly longer with SILC (111.1 ± 30.34 minutes) compared to 2ILC (79.1 ± 15.74 minutes) and 3ILC (80.2 ± 29.41 minutes) (p < 0.01). Post-operative pethidine dosage was significantly lower in the 2ILC group (0.29 ± 0.358 mg/kg) compared to the 3ILC group (1.02 ± 0.802 mg/kg) (p < 0.05). Length of hospital stay (LOS) was significantly shorter in the SILC group (2.52 ± 0.566 days) compared to the 3ILC group (3.1 ± 1.02 days) (p < 0.05). There were no complications.

Conclusions

SILC is a safe and feasible procedure that is comparable to multi-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (MILC). We have introduced a recommended step-by-step training program. SILC needed longer operative time than MILC but has potential benefits in terms of LOS and post-operative pain.

Keyword

laparoscopic cholecystectomy

1. Introduction

Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILC) is emerging as an alternative to standard four-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (4ILC). The potential benefits of SILC include less post-operative pain, faster recovery periods, and better cosmetic outcomes, but there are several issues with SILC that need to be addressed before this new technique can be adopted in routine clinical practice. The first issue is safety. Many studies have reported that SILC is very safe when performed by experienced surgeons.1; 2; 3; 4 ; 5 However, just how to gain that experience has rarely been discussed. The few studies that have analyzed the learning curve towards competency in the SILC procedure have resulted in inconsistent results,6; 7 ; 8 so reproducibility is the second issue. An appropriate training program needs to be established. Proving superiority of SILC over standard 4ILC is a third issue. In fact, its potential superiority is the main reason why surgeons attempt this more difficult procedure. The last issue is cost. Since SILC was introduced in 1997, a variety of techniques have been used and most of them use expensive instruments such as articulating instruments, curved instruments, multi-trocar ports, etc.9; 10; 11; 12; 13 ; 14 However, owing to the well-established cosmetic benefits of SILC, the cost of these instruments may be justified.

This study presents one surgeons experience of SILC, self-taught using conventional instruments, and a retrospective analysis of the data.

2. Patients and methods

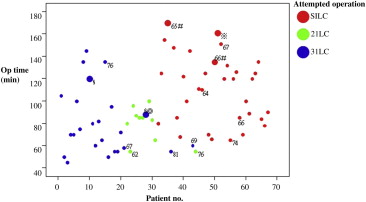

During the period from July 2009 to March 2011, 117 consecutive patients underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) for benign gallbladder diseases by one surgeon at the Mackay Memorial Hospital, Hsin-Chu Branch, Hsin-Chu City, Taiwan. Sixty-seven patients were enrolled, and the exclusion criteria were acute cholecystitis, concomitant choledocholithiasis, suspicious biliary tract malignancy, and previous major surgery of the upper abdomen. These patients were coded chronologically. LCs were attempted as follows: 24 three-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomies (3ILC), 10 two-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomies (2ILC), and 33 SILC (Fig. 1). The selection of the different procedures attempted was made at the surgeons discretion before the operations. The three-incision technique was used for Patients 1 through to 21. 2ILC was used for Patients 22 through to 31, except for Patient 28, who had severe liver cirrhosis and therefore 3ILC was selected. Finally, SILC was used for Patients 32 through to 67, except for Patients 36, 42, and 44. 3ILC was used for Patients 36 and 42, and 2ILC was performed for Patient 44 because of old age. From Patient 45 (the eleventh case) onwards, age was no longer concerned and SILC was used for the remaining patients. Instruments used were identical to those used in standard 4ILC. Patient age, body mass index, ASA classification, operative time, estimated blood loss, complications, post-operative narcotic use, length of hospital stay (LOS), and pathologic diagnosis were recorded. We defined the operative duration as the interval from initial skin incision to skin closure. The post-operative narcotic use was recorded as the intramuscular pethidine dose per kilogram of patient body weight. The hospital stay was defined as the duration between the day of surgery and the day of discharge.

|

|

|

Figure 1. Only patients over 60 years of age are shown. Big marks: patients undergoing converted procedures; # procedures converted to 2ILC; procedures converted to 3ILC; § procedures converted to 4ILC; a 52-year-old male patient had severe liver cirrhosis. |

The above data were analyzed by the Pearson chi-square test and one-way ANOVA. The Scheffé method was adopted for the post hoc test. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Surgical technique

3.1. SILC

The patient was placed in a reverse Trendelenburg position after endotracheal general anesthesia. The surgeon and the assistant stood on the left side of the patient. A 1.5–2 cm vertical paraumbilical incision was made on the left side. A pneumoperitoneum up to 15 mmHg was created using a Veress needle. Two 5 mm ports and a 3 mm port were inserted through three separate fasciotomies in a vertical line. A 5 mm 30-degree rigid laparoscope was inserted through the lower 5 mm optic port for visualization. A 3 mm grasper was inserted through the 3 mm port for retraction of the Hartmanns pouch of the gallbladder. A 5 mm hook electrocautery, curved dissector, and right angle dissector were inserted through the upper 5 mm working port alternatively to dissect the Calot triangle until the critical view of safety (CVS) described by Strasberg et al in 1995 was obtained.15 The CVS was documented by photographs. The cystic duct and the cystic artery were clipped with a 5 mm clip applier and then divided. The gallbladder was then dissected off the liver bed by a 5 mm hook electrocautery. The lower 5 mm port was upgraded to a 10 mm reusable port. An endobag was inserted into the abdominal cavity through the 10 mm port. The gallbladder was placed into the endobag, which was extracted through the 10 mm fasciotomy. All three fascial defects were sutured as well as the skin incision.

3.2. 2ILC

Two 5 mm ports were inserted via a 1.5 cm vertical paraumbilical incision after pneumoperitoneum was established. A 5 mm 30-degree laparoscope was inserted through the lower port. A third 5 mm port was inserted via a 5 mm transverse incision over the epigastrium. Both the epigastric port and the upper paraumbilical port were used as a retraction port or a working port.

3.3. 3ILC

A 10 mm reusable port was inserted via a 1 cm transverse incision below the umbilicus after pneumoperitoneum was established. A 10 mm 30-degree rigid laparoscope was used for visualization. Besides the 5 mm epigastric working port, another 5 mm port was inserted at the right flank for gallbladder retraction. Endobag insertion and specimen retraction was via the 10 mm infraumbilical port.

4. Results

There was no statistical difference in the baseline characteristics between the three groups of patients included (Table 1). In the SILC group (n = 33), SILC was successfully accomplished in 30 patients (90.9%) but conversion was required in 3 patients (9.1%) (Table 2). Two of the procedures were converted to 2ILC and the last one was converted to 3ILC. In the 3ILC group (n = 24), conversion was required in two patients (8.3%). Both these procedures were converted to 4ILC. There was no procedure conversion in the 2ILC group (n = 10). Estimated blood loss was similar (9.1 ± 11.69 mL, 5.0 ± 0 mL, and 10.4 ± 13.51 mL in the SILC, 2ILC, and 3ILC groups, respectively). Operative time was significantly longer with SILC (111.1 ± 30.34 minutes) compared to 2ILC (79.1 ± 15.74 minutes) and 3ILC (80.2 ± 29.41 minutes) (p < 0.01). Post-operative pethidine dosage was significantly lower in the 2ILC group (0.29 ± 0.358 mg/kg) compared to the 3ILC group (1.02 ± 0.802 mg/kg) (p < 0.05). LOS was significantly shorter in the SILC group (2.52 ± 0.566 days) compared to the 3ILC group (3.1 ± 1.02 days) (p < 0.05). There were no complications during or following any of the surgeries.

| SILC | 2ILC | 3ILC | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient numbers, n | 33 | 10 | 24 | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.381 | |||

| Male | 10 (30.3) | 1 (10.0) | 5 (20.8) | |

| Female | 23 (69.7) | 9 (90.0) | 19 (79.2) | |

| Age (y), mean ± SD (range) | 43.8 ± 14.3 (24–74) | 44.2 ± 17.2 (26–76) | 48.2 ± 15.3 (22–81) | 0.536 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD (range) | 24.3 ± 3.6 (18.5–32.1) | 25.3 ± 3.9 (21.1–31.2) | 25.1 ± 5.0 (18.5–34.1) | 0.700 |

| ASA score, mean ± SD (range) | 2.06 ± 0.50 (1–3) | 2.20 ± 0.42 (2–3) | 2.21 ± 0.66 (1–3) | 0.561 |

| Pre-operative diagnosis, n (%) | 0.835 | |||

| Biliary colic | 28 (84.8) | 9 (90.0) | 19 (79.2) | |

| GB polyp | 2 (6.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.2) | |

| Biliary colic and GB polyp | 3 (9.1) | 1 (10.0) | 4 (16.7) |

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI = body mass index; GB = gallbladder; 2ILC = two incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy; 3ILC = three incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

| SILC | 2ILC | 3ILC | p | Post hoc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients number, n | 33 | 10 | 24 | ||

| Conversion, n | 3 | 0 | 2 | ||

| 2ILC | 2 | — | — | ||

| 3ILC | 1 | 0 | — | ||

| 4ILC (standard LC) | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||

| OC | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Operative time (min), mean ± SD (range) | 111 ± 30.3 (65–170) | 79 ± 15.7 (55–100) | 80 ± 29.4 (45–145) | < 0.001 | SILC > 2ILC* SILC > 3ILC ** |

| Estimated blood loss (mL), mean ± SD (range) | 9 ± 11.7 (5–50) | 5 ± 0.0 (5–5) | 10 ± 13.5 (5–50) | 0.464 | |

| Pethidine dose (mg/kg), mean ± SD (range) | 0.87 ± 0.66 (0–2.98) | 0.29 ± 0.36 (0–1.07) | 1.02 ± 0.80 (0–3.38) | 0.021 | 3ILC > 2ILC* |

| Length of hospital stay (d), mean ± SD (range) | 2.5 ± 0.57 (2–4) | 2.5 ± 0.53 (2–3) | 3.1 ± 1.02 (2–5) | 0.016 | 3ILC > SILC* |

2ILC = two incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy; 3ILC = three incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy; 4ILC = four incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy; OC = open cholecystectomy.

- p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01.

5. Discussion

Many studies verifying the safety and efficacy of SILC have been presented since 2009.1; 2; 3; 4 ; 5 Several of them have advocated that experienced laparoscopic surgeons can undertake a steep learning curve to eventually become well trained in SILC.6; 7 ; 8 However, the details and stages of such a training have rarely been discussed.

In our study, we have suggested a step-by-step training program leading to competency in the SILC procedure using conventional instruments.

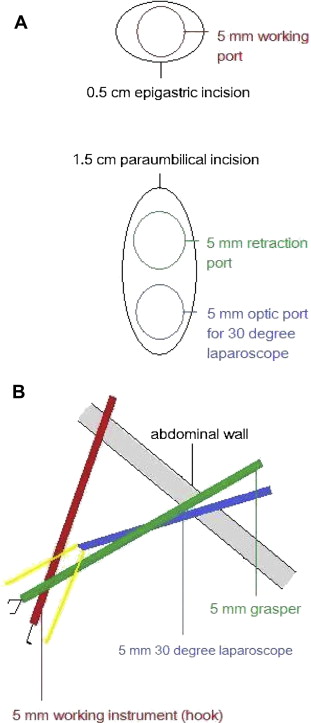

First, the surgeon must gain experience in the 3ILC procedure with a 30-degree laparoscope. Then the surgeon can move on to performing the 2ILC procedure mentioned above, initially by using the upper paraumbilical port for gallbladder retraction and the epigastric port for dissection (Fig. 2). This is the first stage of the 2ILC procedure. This should be easy for a beginner because the only difference between this technique and 3ILC is the retraction port, and the retraction port and the optic port in the same paraumbilical incision seldom cause collision.

|

|

|

Figure 2. (A) The skin incisions and port insertions during stage one of a two-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy; (B) lateral view (from the patients right side). |

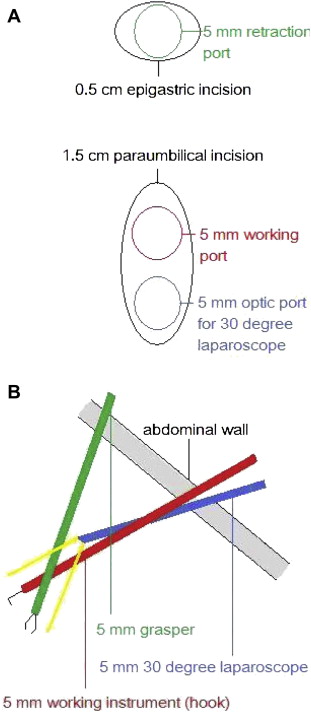

Once the surgeon is familiar with this technique, the roles of the epigastric port and the upper paraumbilical port can be exchanged (Fig. 3). This is the second stage of the 2ILC procedure. In this situation “sword fighting” of the two paraumbilical ports often happens and vision may be hindered by the working instrument. By using a 5 mm 30-degree laparoscope, this problem can be overcome. The key point in this stage is to delicately control the working port and the optic port in the paraumbilical incision.

|

|

|

Figure 3. (A) The skin incisions and port insertions during stage two of a two-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy; (B) lateral view (from the patients right side). |

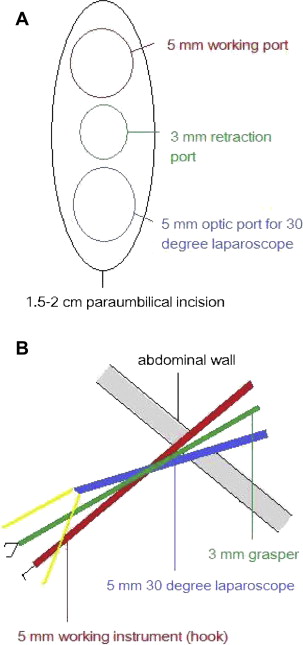

Finally, the surgeon can proceed to performing the SILC procedure (Fig. 4). “Sword fighting” of the three paraumbilical ports can be very troublesome. In our experience, placing the three ports in a vertical line can minimize this problem. For patients with a relatively long distance between the gallbladder and the umbilicus, or a firm gallbladder, the middle 3 mm retraction port can be replaced with a 5 mm port. In this situation, the paraumbilical incision may be extended to 2.5 cm in length to fit the three 5 mm ports.

|

|

|

Figure 4. (A) The skin incision and port insertions during a single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy; (B) lateral view (from the patients right side). |

Furthermore, we recommend a self-camera technique. The assistant stands at the surgeons right side to control the retraction grasper, and the surgeon controls the working instrument with the right hand and the laparoscope with the left hand. This avoids the difficult cross-hand technique. The surgeon can obviate the collision of the working port and the optic port by delicate movements, and rotating the instruments.

Although we recommend that beginners in this training program take a step-by-step approach to this learning period, just how many procedures the surgeon should complete before proceeding to the next stage remains subject to verification.

Several studies comparing SILC with 4ILC have been reported since 2010,9; 12; 13; 14; 16 ; 17 and the results vary with regard to patient post-operative pain and recovery times. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study comparing SILC, 2ILC, and 3ILC. Our study has shown a statistically significant difference in operative time (SILC > 2ILC and SILC > 3ILC), post-operative pethidine dosage (3ILC > 2ILC), and LOS (3ILC > SILC).

The retrospective nature of our study and the small patient numbers in the 2ILC procedure group were the limitations of our series. The exact role of SILC in benign gallbladder disease needs further investigation in randomized and prospective studies.

We only used conventional instruments in our procedures. However, the actual cost involves multiple factors, including operation room equipment, operative instruments, anesthesia, LOS, and personnel expenses. This issue needs more detailed evaluation.

6. Conclusions

SILC is a safe and feasible procedure that is comparable to 2ILC and 3ILC for treatment of benign gallbladder diseases. Because of the difficulty of this novel procedure, we introduced a recommended step-by-step training program. In our study, SILC needed longer operative time than 2ILC and 3ILC. SILC was superior to 3ILC in terms of LOS, and 2ILC caused less post-operative pain than 3ILC. All three procedures can be performed with conventional instruments. Further randomized and prospective studies are still required to validate our findings and recommendations.

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge administrative, technical, and material support from Miss Yi-Chun Liao.

References

- 1 P.G. Curcillo 2nd, A.S. Wu, E.R. Podolsky, et al.; Single-port-access (SPA) cholecystectomy: a multi-institutional report of the first 297 cases; Surg Endosc, 24 (8) (2010), pp. 1854–1860

- 2 J.K. Elsey, D.V. Feliciano; Initial experience with single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy; J Am Coll Surg, 210 (2010), pp. 620–626

- 3 H. Ravas, E. Varela, D. Scott; Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: initial evaluation of a large series of patients; Surg Endosc, 24 (2010), pp. 1403–1412

- 4 B. Bokobza, A. Valverde, E. Magne, et al.; Single umbilical incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy; initial experience of the Coelio Club; J Visc Surg, 147 (2010), pp. e253–257

- 5 H.J. Han, S.B. Choi, W.B. Kim, S.Y. Choi; Single-incision multiport laparoscopic cholecystectomy: things to overcome; Arch Surg, 146 (2011), pp. 68–73

- 6 A.J. Kravetz, D. Iddings, M.D. Basson, M.A. Kia; The learning curve with single-port cholecystectomy; JSLS, 13 (2009), pp. 332–336

- 7 Z. Qiu, J. Sun, Y. Pu, T. Jiang, J. Cao, W. Wu; Learning curve of transumbilical single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILS): a preliminary study of 80 selected patients with benign gallbladder diseases; World J Surg, 35 (2011), pp. 2092–2101

- 8 H.J. Han, S.B. Choi, M.S. Park, et al.; Learning curve of single port laparoscopic cholecystectomy determined using the non-linear ordinary least squares method based on a non-linear regression model: an analysis of 150 consecutive patients; J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci, 18 (2011), pp. 510–515

- 9 J. Marks, R. Tacchino, K. Roberts, et al.; Prospective randomized controlled trial of traditional laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: report of preliminary data; Am J Surg, 201 (2011), pp. 369–372

- 10 J. Hernandez, S. Ross, C. Morton, et al.; The learning curve of laparoendoscopic single-site (LESS) cholecystectomy: definable, short, and safe; J Am Coll Surg, 211 (2010), pp. 652–657

- 11 W. Ji, K. Ding, R. Yang, X.D. Liu, N. Li, J.S. Li; Outpatient single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy in 22 patients with gallbladder disease; Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int, 9 (2010), pp. 629–633

- 12 P.C. Lee, C. Lo, P.S. Lai, et al.; Randomized clinical trial of single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus minilaparoscopic cholecystectomy; Br J Surg, 97 (2010), pp. 1007–1012

- 13 F. Khambaty, F. Brody, K. Vaziri, C. Edwards; Laparoscopic versus single-incision cholecystectomy; World J Surg, 35 (2011), pp. 967–972

- 14 A. Chow, S. Purkayastha, O. Aziz, D. Pefanis, P. Paraskeva; Single-incision laparoscopic surgery for cholecystectomy: a retrospective comparison with 4-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy; Arch Surg, 145 (2010), pp. 1187–1191

- 15 S.M. Strasberg, M. Hertl, N.J. Soper; An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy; J Am Coll Surg, 180 (1995), pp. 101–125

- 16 E.C. Tsimoyiannis, K.E. Tsimogiannis, G. Pappas-Gogos, et al.; Different pain scores in single transumbilical incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus classic laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized controlled trial; Surg Endosc, 24 (2010), pp. 1842–1848

- 17 J.S. Fronza, J.G. Linn, A.P. Nagle, N.J. Soper; A single institutions experience with single incision cholecystectomy compared to standard laparoscopic cholecystectomy; Surgery, 148 (2010), pp. 731–734

Document information

Published on 26/05/17

Submitted on 26/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?