Summary

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most prevalent human cancers in the world, but its prognosis is extremely poor. HCC is considered a hypervascular tumor. Thalidomide, which has been known to inhibit growth factor-induced neovascularization, is a convenient alternative to target therapy such as sorafenib. We report a 65-year-old male patient with alcoholic liver cirrhosis that was diagnosed having multiple HCCs during surveillance. The patient was assessed as inoperable and unsuited for transhepatic arterial chemoembolization or systemic chemotherapy. After discussing the therapeutic alternatives, he decided to receive low-dose thalidomide (100 mg daily) therapy. Fortunately, follow-up liver biochemical tests, serum α-fetoprotein level, and dynamic computed tomography showed complete remission of the HCCs 4.5 months after thalidomide treatment and this was documented for more than 22 months without evidence of tumor recurrence.

Keywords

Complete remission ; Hepatocellular carcinoma ; Thalidomide

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most prevalent human cancers in the world, especially in Asia and Africa, but its prognosis is extremely poor. Surgical resection and local radiofrequency ablation therapy are curative in only a minority of patients and systemic chemotherapy is difficult for HCC patients to tolerate because liver function reserve is often impaired due to underlying cirrhosis, which is accompanied by hypersplenism and peripheral cytopenia. HCC is a relatively chemoresistant tumor and is highly refractory to cytotoxic chemotherapy. Transhepatic arterial chemoembolization (TACE) is the most widely used locoregional treatment for patients with intermediate stage HCC, but it is contraindicated in patients with main portal vein thrombosis or poor liver function reserve. Sorafenib, an oral multikinase inhibitor that suppresses tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis, is the standard of care for patients with advanced stage disease. However, sorafenib for advanced HCC is still not easy for Asian physicians to prescribe due to high cost. Therefore, advanced and unresectable HCC remains incurable, with a median survival of <6 months. Generally, HCC is considered a hypervascular tumor. Increased levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and high microvessel density have been found in HCC. Therefore, inhibition of angiogenesis represents a potential therapeutic target. Thalidomide, which has been known to inhibit growth factor-induced neovascularization, is a convenient alternative to treatment with cytotoxic agents. We report a male patient with alcoholic liver cirrhosis and advanced HCC after thalidomide treatment that achieved complete HCC remission.

Case report

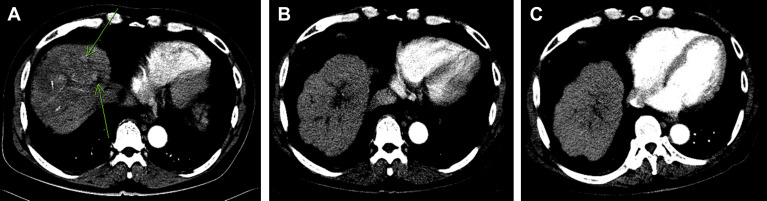

A 65-year-old man was a victim of alcoholic liver cirrhosis (Child–Pugh class B) with ascites under diuretics (oral furosemide 80 mg and spironolactone 200 mg daily) control and received periodic HCC surveillance every 4 months for 14 years. Unfortunately, his α-fetoprotein (AFP) level was highly elevated and abdominal ultrasonography detected multiple liver tumors in November 2005. Physical examination revealed jaundice, mild hepatomegaly with a span of 13 cm on the right middle clavicle line and an irregular margin with a hard consistency that measured 2 cm below the right costal margin. The spleen was impalpable. No fever, skin rash, ascites, spider angioma, or palmar erythema was noted. Laboratory studies disclosed the following results: hemoglobin, 13.5 g/dL; leukocytes, 5.2 × 109 /L; platelets, 110 × 109 /L; albumin, 3.6 g/dL, globulin, 3.1 g/dL; total bilirubin, 4.2 mg/dL (normal, <1.3 mg/dL); serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 222 U/L (normal, <34 U/L); serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 51 U/L (normal, <36 U/L); alkaline phosphatase, 210 IU/L (normal, <94 IU/L); prothrombin time, 12.4 seconds (control, 10.0 seconds); international normalized ratio, 1.12; and AFP 4935 ng/mL (normal < 3 ng/mL). Hepatitis B surface antigen and antibody to hepatitis C virus were both negative. Abdominal ultrasonography showed multiple hyperechoic and mixed echoic tumors in cirrhotic parenchyma, the largest being 5.9 cm in diameter, without the presence of ascites. Dynamic computed tomography (CT) showed multiple arterially enhanced tumors, mainly in the right lobe having a portal- and delayed-phase washed-out appearance. The invasion of tumors into the main portal trunk and its proximal branches with suspicion of biliary tree compression are shown in Fig. 1 A. The tumors were considered HCCs because of the presence of the characterized arterial vascularization and rising AFP levels. This patient appeared to be asymptomatic and was staged as Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage C.

|

|

|

Figure 1. (A) Prior to thalidomide therapy, multiple arterially enhanced tumors were located in the right lobe (arrow), and multiple infiltrating tumors were located in the central portion of the liver with portal vein thrombi. (B) Follow-up examination after 4.5 months of thalidomide therapy showed complete remission of liver tumors and significant regression of portal vein thrombi. (C) Follow-up examination after 20 months of thalidomide therapy showed complete remission of liver tumors and portal vein thrombi. |

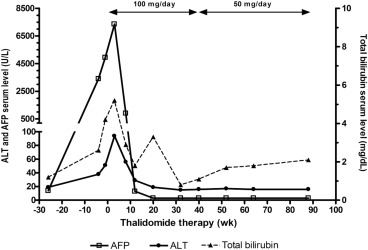

The patient was assessed as inoperable and unsuited for TACE or systemic chemotherapy. Attending a clinical trial with target therapy was suggested initially, but the patient refused. He agreed to receive thalidomide (50 mg capsule; TTY Biopharm, Taipei, Taiwan) 50 mg twice daily after obtaining written informed consent and followed at an outpatient clinic. Three weeks after thalidomide therapy, he occasionally complained of skin eruptions with itching. There was no fever, nausea, constipation, vomiting, fatigue, or somnolence. Laboratory studies disclosed the following: AST, 436 U/L; ALT, 94 U/L; total bilirubin, 5.2 mg/dL; and serum AFP, 7350 ng/mL. He continued to take thalidomide 100 mg daily without specific complaint. Follow-up liver biochemical tests after 3 months of thalidomide therapy showed the following: AST, 44 IU/L; ALT, 29 IU/L; total bilirubin, 1.8 mg/dL; and serum AFP, 13 ng/mL. The clinical course is shown in Fig. 2 . Dynamic CT showed significant regression of the portal vein thrombi and complete remission of tumors 4.5 months after initial diagnosis (Fig. 1 B). Thalidomide dose was reduced to 50 mg daily after 9 months treatment because of serum AFP and ultrasonography showing no evidence of HCC recurrence. Abdominal CT or ultrasonography at 20 months after thalidomide therapy showed complete tumor regression (Fig. 1 C). The AST, ALT, and AFP levels remained within normal limits. Unfortunately, he succumbed to a perforated duodenal ulcer with multiple organ failure 22 months after initial diagnosis.

|

|

|

Figure 2. Changes in serum α-fetoprotein (AFP) levels before and after thalidomide therapy. ALT = alanine aminotransferase. |

Discussion

The clinical, laboratory, and image modalities on presentation and the subsequent clinical course of this particular patient indicated that he was a patient with HCC who showed complete response to oral thalidomide therapy.

HCC is a highly prevalent disease in many Asian countries, accounting for 80% of victims worldwide. This patient was a victim of alcoholic liver cirrhosis (Child–Pugh class B) and multiple HCCs (BCLC stage C). According to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver guidelines, only sorafenib is recommended for BCLC stage C HCC. However, the treatment recommendation of the Asian Pacific Association for the study of liver and Asian experts disclosed not only sorafenib but also many therapeutic options such as surgical resection, TACE, hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy, and external radiation can be tried for advanced stage [1] . Unfortunately, our patient had impaired functional liver reserve and multinodular tumors with portal vein invasion, and antiangiogenic treatment was the favorable therapy. However, sorafenib was not available in Taiwan in 2005. Thalidomide, an antiangiogenesis agent, was found to have a modest effect in patients with advanced HCC. It is an alternative therapy in patients with advanced HCC at a much lower cost than sorafenib. Although the development of target agents indeed represents an important advance in the treatment of advanced HCC, studies of the efficacy of thalidomide are less frequently reported [2] .

Complete response to thalidomide therapy is rarely seen in advanced HCC. Three phase II studies have evaluated the utility of thalidomide in the treatment of advanced HCC and demonstrated a response rate of 3–5% [3] ; [4] ; no patient showed a complete response. To the best of our knowledge, there were two patients with advanced HCC under thalidomide therapy who subsequently showed complete remission. In a retrospective study, one of 53 patients with advanced HCC (1.9%) achieved a complete response; however, the patient had prior TACE [2] . In another report, the complete response was observed in a 62-year-old man with chronic hepatitis C and metastasis to multiple lymph nodes and to the peritoneum [5] ; he had received thalidomide 200–300 mg/day and had remained in a remission state for more than 11 months. Demeria et al [6] administered 100 mg thalidomide once daily to a 73-year-old man with multiple HCCs. Although a dramatic reduction in the tumor size was seen after 1 month of therapy, he succumbed to tumor recurrence 17 months after the initial diagnosis. In our patient, complete remission of HCC was documented for a period of 22 months without evidence of tumor recurrence.

Different dosages of thalidomide have been used in the treatment of advanced HCC patients. It is well known that thalidomide toxicity, but not necessarily efficacy, increases with higher dosage. Chen et al [7] reported a patient whose advanced HCC achieved durable remission after low-dose thalidomide (50–100 mg) therapy. A retrospective study also showed that for treating advanced HCC, low-dose thalidomide (100 mg) has comparable single-agent activity but less treatment-related toxicity compared to high-dose thalidomide [8] . Our case demonstrates that a low dose of thalidomide 50–100 mg daily can be effective for treating advanced HCC and can even achieve a long-term complete response.

Serum AFP levels are routinely monitored for tracking post-treatment HCC recurrence. Alterations in serum AFP levels have been shown to reflect accurately the response of HCC to systemic chemotherapy and to TACE. Chen et al [9] reported that AFP response can more accurately reflect the biological response of advanced HCC to thalidomide therapy than can radiographic response. In their series, radiographic response was observed in all AFP responders. AFP levels fell to nadir after 4–16 weeks (median 8 weeks) of thalidomide therapy. Furthermore, early AFP response (defined as decline > 20% from baseline after 2–4 weeks of treatment) had better survival outcomes for patients with advanced HCC who receive antiangiogenic therapy [10] . In our case, a rapid fall of AFP after 8 weeks of therapy was observed. Therefore, we suggest that the evaluation of the therapeutic effect of therapy should incorporate AFP responses, especially in the early phase of treatment. If there is early AFP response, low-dose thalidomide can be effective in patients with advanced HCC.

This patient with liver cirrhosis and advanced HCC under low dose thalidomide therapy achieved complete remission. We suggest that thalidomide can be considered as an alternative treatment in patients with advanced HCC, who cannot afford sorafenib therapy.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1] M. Omata, L.A. Lesmana, R. Tateishi, P.J. Chen, S.M. Lin, H. Yoshida, et al.; Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver consensus recommendations on hepatocellular carcinoma; Hepatol Int, 4 (2010), pp. 439–474

- [2] Y.Y. Chen, H.H. Yen, K.C. Chou, S.S. Wu; Thalidomide-based multidisciplinary treatment for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective analysis; World J Gastroenterol, 18 (2012), pp. 466–471

- [3] Y.Z. Patt, M.M. Hassan, R.D. Lozano, A.K. Nooka, I.I. Schnirer, J.B. Zeldis, et al.; Thalidomide in the treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase II trial; Cancer, 103 (2005), pp. 749–755

- [4] B. Chuah, R. Lim, M. Boyer, A.B. Ong, S.W. Wong, H.L. Kong, et al.; Multi-centre phase II trial of Thalidomide in the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma; Acta Oncol, 46 (2007), pp. 234–238

- [5] C. Hsu, C.N. Chen, L.T. Chen, C.Y. Wu, P.M. Yang, M.Y. Lai, et al.; Low-dose thalidomide treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma; Oncology, 65 (2003), pp. 242–249

- [6] D. Demeria, I. Birchall, V.G. Bain; Dramatic reduction in tumour size in hepatocellular carcinoma patients on thalidomide therapy; Can J Gastroenterol, 21 (2007), pp. 517–518

- [7] S.C. Chen, H.J. Tsai, C.M. Jan, Y.H. Wang, L.T. Chen; Low dose of thalidomide can be effective in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma; J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 21 (2006), pp. 1868–1869

- [8] T. Yau, P. Chan, H. Wong, K.K. Ng, S.H. Chok, T.T. Cheung, et al.; Efficacy and tolerability of low-dose thalidomide as first-line systemic treatment of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma; Oncology, 72 (2007), pp. 67–71

- [9] L.T. Chen, T.W. Liu, Y. Chao, H.S. Shiah, J.Y. Chang, S.H. Juang, et al.; alpha-fetoprotein response predicts survival benefits of thalidomide in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma; Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 22 (2005), pp. 217–226

- [10] Y.Y. Shao, Z.Z. Lin, C. Hsu, Y.C. Shen, C.H. Hsu, A.L. Cheng; Early alpha-fetoprotein response predicts treatment efficacy of antiangiogenic systemic therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma; Cancer, 116 (2010), pp. 4590–4596

Document information

Published on 15/05/17

Submitted on 15/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?