Abstract

The Rumeli Fortress has a unique place in world history. This study presents information on the castle and Fatih period, explains the aspects of castle thought to be important, and discusses the gradually ruined areas of the castle.

Keywords

Architectural research ; History research method ; Scientific research ; Bogazkesen ; Rumeli Fortress ; Restoration

1. Introduction

Rumeli Fortress is a castle built by the order of Fatih in 1452. This unique example of Ottoman military architecture survives as a primary source of evidence for architecture researchers in their study of history. The main sources of evidence are Ayverdi, Gabriel, and Dağtekin (Erişmiş, 2012 ; Ayverdi, 1974 ; Ayverdi, 1953 ; Ilgaz, 1941 ; Dağtekin, 1963 ).

2. Method

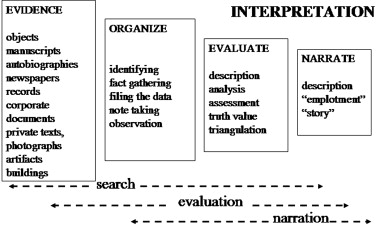

Archer, Togan and Standords ideas on methodology is used in this paper and this study is prepared according to the methodology of interpretive architectural view. The interpretive research scheme is summarized in Fig. 1 . The research subject is determined to be the Rumeli Hisarı. First, an academic report on the Rumeli Fortress is given. The sources of information for this report provide the basis for the survey of the Rumeli Hisarı. Most of the sources are criticized, and a number of errors were identified, especially during the evaluation step of the interpretive research scheme (Alyanak, 1999 ; Togan, 1981 ; Stanford, 1994 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 1. Interpretive research scheme. |

Research is defined by Archer as a systematic inquiry that aims to communicate new knowledge or understanding (Alyanak, 1999 ). Popper argues that the scientist must seek to disprove his hypothesis because even a large number of confirmations of a rule would be incapable of proving such rule. One counter example would suffice to disprove the rule. However, when a rule remains to stand despite attempts by numerous people to disprove it, then a greater likelihood exists that such rule approximates the truth (Stanford, 1994 ).

Togan defines three types of history: reference, pragmatic, and genetic. Reference history narrates or spreads rumors without analysis and systematization. Pragmatic history is concerned with gaining more knowledge about a historical event to reach a useful conclusion. Genetic history asks “why” and “how” questions regarding the occurrence of events to clarify the development of humanity and the reasons behind such development (Togan, 1981 ).

The aim of history is to find the truth. The science of history has revealed certain facts, and the insufficient findings on materials regarding less known events do no harm to the scientific value of a study. The vital part of the historical method is “intikad” or criticism, which is divided into two branches: external and internal. Consciousness of whether a source leads to the truth falls under external criticism. Internal criticism involves the study and judgment of a source by a scholar of history to determine the usefulness of the source in shedding light on a particular event (Togan, 1981 ).

Stanford claims that three cardinal sins should be avoided at all costs: subordinating history to any non-historical theory or ideology, such as religious, economic, philosophical, sociological, and political; neglecting breadth (i.e., failing to take all considerations into account and to do justice to all concerned); and ignoring the suppressing evidence (Stanford, 1994 ). The first step toward reaching a historical conclusion is to evaluate and criticize all views found in the references (Dobson and Ziemann, 2009 ).

3. Result of source criticism

Analyzing references or information sources from a critical perspective is necessary. References do not contain absolute truths and could actually contain mistakes that can be detected by discerning minds. In the process of studying the Rumeli Fortress, 52 reference sources were analyzed, and numerous minor and some major mistakes were detected (Erişmiş, 2012 ).

The pieces of information that do not match were identified on subjects such as the physical properties of the castle, number and geometric forms of bastions, positioning of the structure on the land, dimensions of the castle, and distance across the bosphorus. Varying dates were also given for the same events in these sources (Erişmiş, 2012 ).

Another point to be critiqued is that the events in the reference sources were narrated in first person with insufficient evidence. Some of the references that were analyzed contain internally invalid texts that are irrelevant to the historical and scientific method. For example, Eren and Babinger mentions about the hadith which played a motivational role in conquest of Istanbul, however chain of rumour to test the validity of these words is not shared. (Erişmiş, 2012 ; Eren, 1994 ; Babinger, 1978 ).

Some references of history were written in a romantic style without attempting to attain objectivity. In some sources, generalizations were made without evidence. Some non-existing properties of the Rumeli Fortress were also shown to be extant. In fact, the very name of the castle “Rumeli Hisarı or Boğazkesen” is rumored to be false in some accounts (Erişmiş, 2012 ).

In summary, references may contain several mistakes, and criticism or “intikad,” which is vital part of history science, should be applied to these sources; otherwise, reaching an unrealistic and unscientific historical conclusion may be regarded as the natural result of a study (Erişmiş, 2012 ).

4. Castle and Fatih period

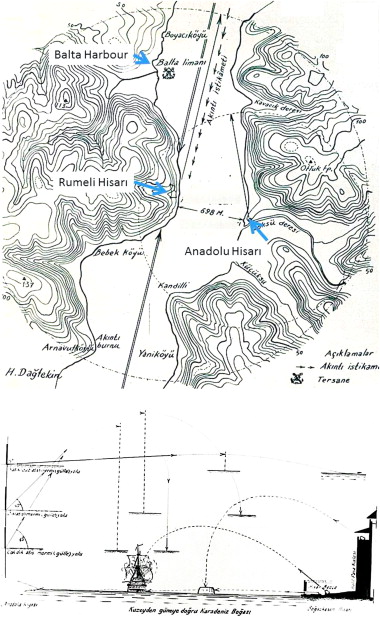

Fatih Sultan Mehmed (Mehmed II) is the son of Murad II. His grandfather, Bayezıt I, ordered for Anadolu Hisarı to be a strategic base in 1394 (Fig. 2 ; Fig. 3 ). Rumeli Hisarı is built on the narrowest area of the bosphorus and was named Boğazkesen in the period of Fatih. The purposes of the structure were to manage the passing ships in the bosphorus, to create a military-financial control point, and to provide a strong fulcrum-resistance base. The acceptance of Fatih on the policy of conquests or “fütühat", which aimed to conquer İstanbul, resulted in the construction of Rumeli Hisarı. The fortress fulfilled its function of cutting the strait in 1453 (Ayverdi, 1974 ; Kılıçlıoğlu et al ., 1992 ; Freely, 2011 ; Eren, 1994 ; Uyar and Erickson, 2009 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 2. Relationship map of the castle and its surroundings. |

|

|

|

Fig. 3. Satellite image and map of the bophorus (A: Rumeli Hisarı). |

Conquering large castles involves the construction of small fortresses near the city civilizations to weaken the city in question. A few soldiers inhabited these small castles to paralyze the logistic flow of the large castles, which resulted in the weakening and subsequent conquering of the fortress. Bursa, which was the first city taken by the Ottomans, was conquered through this strategy (Ayverdi, 1974 ; Sünbüllük, 1950 ).

Rumeli Hisarı was built as a dominant base of the region that served as a military center to prevent the ships that carry food from the black sea side from reaching the Constantinople Castle. The fortress was built to inhibit the resources of the castle and to weaken the soldiers that inhabit the castle (Ayverdi, 1974 ; Ayverdi, 1953 ; Kılıçlıoğlu et al ., 1992 ; Tamer, 2001 ).

Once the castle was constructed, Firuz Bey was assigned as the commander of the few soldiers in the castle. He was given the authority to control the ships that passed the bosphorus in front of the castle. The ships were forced to pay a certain amount of tax, and those who refused to pay were sunk by canons, which were mostly placed in the front garden (hisar peçe) by the sea. In 1452, some ships managed to pass despite the canons. However, the bosphorus sea traffic was effectively cut in 1453 (Erişmiş, 2012 ; Freely, 2011 ; Tamer, 2001 ; Tracy, 2000 ).

The main materials used in the building included rubble-stone, lime, brick, iron, and wood. The materials and master builders were gathered from various regions of the state. Most of the references determined that the construction of the building was completed within a short period of time under a dense working environment. In 1949 Çetintaş argued that It was impossible to construct such a building in such short period of time, even too much money is spent (Erişmiş, 2012 ; Ayverdi, 1974 ; Ayverdi, 1953 ; Freely, 2011 ; Nicolle and Hook, 2000 ; Sünbüllük, 1950 ; Erdenen, 2003 ).

Rumeli Hisarı is a fortress built by the order of Fatih in 1452. This structure, which is based on Ottoman military architecture and exhibits unique properties, has survived as primary evidence for researchers of architectural history despite the damage it has incurred in several occasions.

5. Importance of fortress

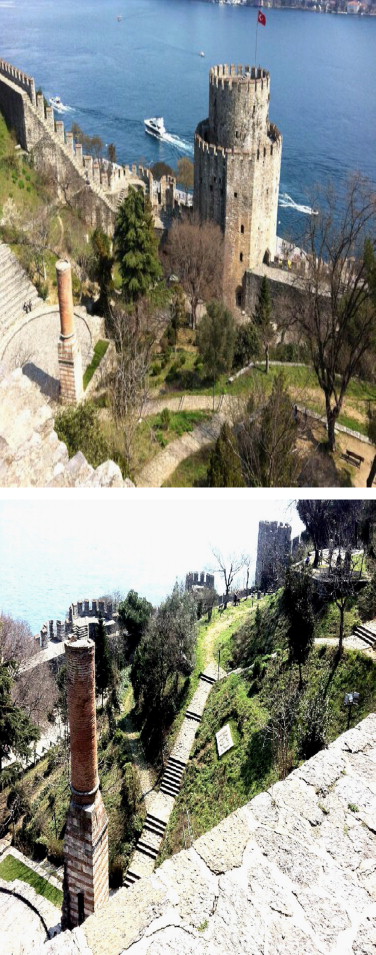

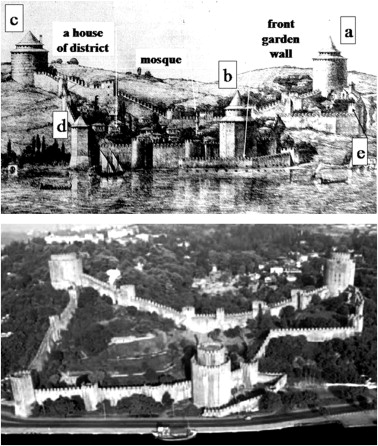

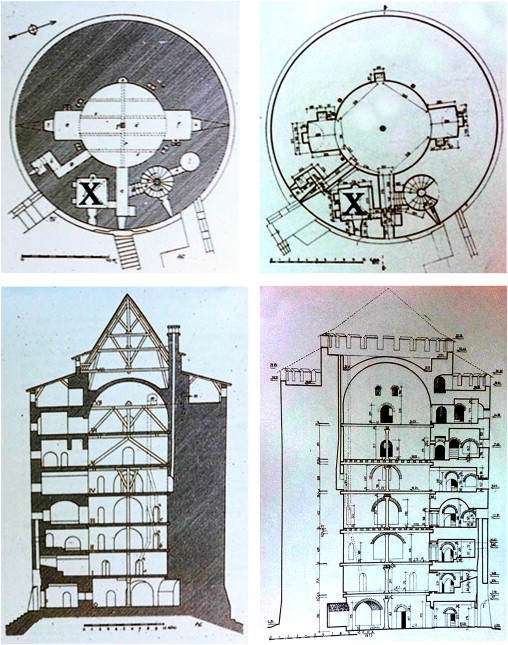

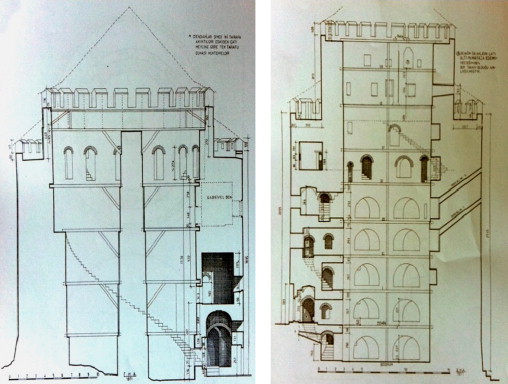

Högg and Ayverdi explained the Turkish contributions of the building (Ayverdi, 1974 ; Ayverdi, 1953 ; Dağtekin, 1963 ). The fortress and its towers are among the largest surviving fortification structures in the world (Fig. 4 , Fig. 5 , Fig. 6 ; Fig. 7 and 8 a–c). The castle was used as a testing site to develop the canon technology during the period. Within 52 years, the canon technology of the Ottomans developed from a state-of-the-art status to the best of its time. One of these canons is exhibited in the London Canon Museum (Dağtekin, 1963 ; Tracy, 2000 ).

|

|

|

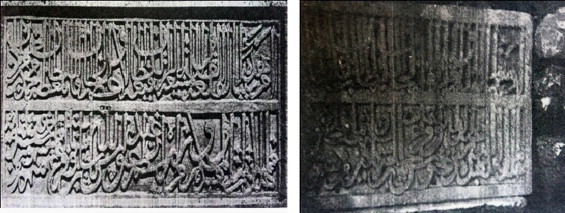

Fig. 4. Inscriptions on the Big and Small ZPT. |

|

|

|

Fig. 5. Ruins of the Front Garden (Hisar Peçe). |

|

|

|

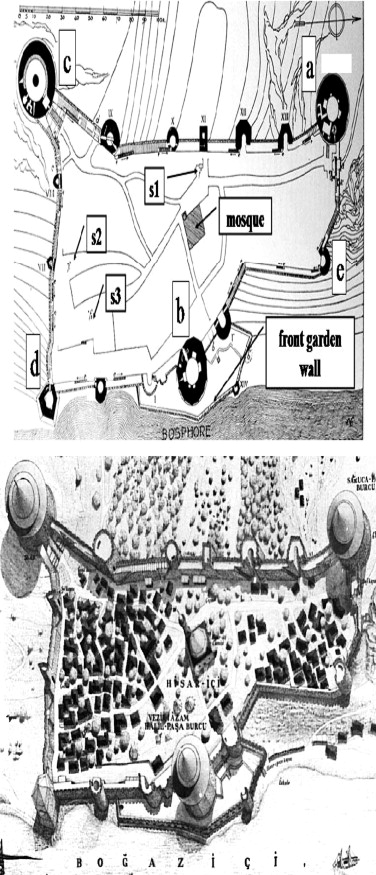

Fig. 6. Plan and aerial view of the Rumeli Fortress. |

|

|

|

Fig. 7. Recent view of the fortress garden. |

|

|

|

Fig. 8. Realistic rendering vs. recent view of the Rumeli Fortress. |

The first Ottoman mosque built in Istanbul is situated in the castle garden (Fig. 4 , Fig. 5 , Fig. 6 ; Fig. 9 ) (Ayverdi, 1974 ; Ayverdi, 1953 ; Ilgaz, 1941 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 9. Fourth floor plan and section view of SPT, Gabriel vs. Ayverdi. |

The width of the castle walls was thrice the size of Constantinople, which is 2.5 m. The canon ball technology at this period proved to be insufficient to destroy walls with a thickness of 7 m (Ayverdi, 1974 ; Kılıçlıoğlu et al ., 1992 ; Erdenen, 2003 ).

The first two Ottoman inscriptions of İstanbul were placed on the Small and Big ZPTs (Fig. 4 , Fig. 5 ; Fig. 6 , and 10 c,d) (Ayverdi, 1974 ; Ayverdi, 1953 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 10. Section view of ZPT and HPT. |

The fortress served a key function in the process of conquest by cutting the bosphorus, which led to a new age. The building was used as a base point and enabled the commander of the fortress to realize offensive attacks. The castle also had a strategic role in the Ottoman Western conquests (Erişmiş, 2012 ).

After the conquest, a district evolved in castle, which was used as a habitation unit (Fig. 4 , Fig. 5 , Fig. 6 ; Fig. 9 ). During World War I, the building was used as a signal-processing site, which diverged from the initial construction purpose (Genim, 2006 ; Sünbüllük, 1950 ).

6. Ruined parts of the building

The front garden wall (hisar peçe), bosphorus observation point, lead-covered conical rooftops of towers, internal furnishing of towers, mosque in the garden, district, and springs were destroyed. The front garden wall (hisar peçe), observation point (e), towers (a, b, c, d), springs (s1, s2, s3), and mosque are shown in Fig. 11 , Fig. 4 ; Fig. 6 (Erişmiş, 2012 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 11. Image from inside the castle in 1890 and an old postcard. |

The first Ottoman mosque of İstanbul, which is presently a ruin, has drawn considerable attention (Fig. 4 , Fig. 5 ; Fig. 6 ). The drawings of Melling and Gabriel reveal that the roofs of four large towers are covered with lead. These roofs are no longer extant (Figs. 4 and 6 a–d). Another element that did not survive is the inner furnishings of the towers (Fig. 7 ; Fig. 8 ). The houses of the district that evolved inside castle were removed. The front garden of the castle, which is called “hisar peçe,” was destroyed and was replaced by houses and a telegram office. The coastal road building part of the front garden wall was also destroyed. The front garden wall, wherein the great canons were placed, also turned to ruin (Fig. 11 ) (Ilgaz, 1941 ; Erdenen, 2003 ).

One of springs (Figs. 6 , s1) was built out of concrete, and a museum management building was added during the restoration attempts in the 1950s. The walls of the first mosque of İstanbul were destroyed, and the minaret part was left as a ruin. The Mosque was replaced by a theater scene, which is irrelevant to the historical context of the building, and concrete steps were placed around this scene (Fig. 5 ). Not only were some castle parts destroyed, but historically irrelevant parts were also added to the building. The castle suffered from natural disasters, such as fires and earthquakes, and some incapable people, who were called architects or architectural organizers, turned the building into its current irrelevant appearance by ignoring the historical context of its construction (Erişmiş, 2012 ).

7. Proposed method of restoration

The chronology table (Table 1 ) shows that numerous attempts to restore Rumeli Hisarı were undertaken. The restoration strategy for the castle should include an initial assessment of these attempts. Ayverdi and Gabriel conducted extensive building surveys on Rumeli Hisarı. Other surveys from archives and photographic evidence have also been gathered. Fig. 9 shows two photographs related to the history of castle. Conferences may also be organized to focus the academic studies on the castle and to understand the building in depth (Liu, 2013 ).

| Date | Presented key events |

|---|---|

| 1452 | Rumeli Fortress was built. On 10 November 1452, two Venetian galleys passed from the Black Sea despite the guns under the authority of Girolamo Morosini. In 2 December 1452, Captain Antonio Rizo was impaled after his vessel had been sunk. The dead from the Byzantinian attack were buried in the hill of Nafi Baba. |

| 1460–4 | The castle was restored. |

| 1509 | An earthquake occurred. |

| 1510–5 | The castle was restored. |

| 1600s | The north tower was used as a prison. |

| 1650 | Sultan Mahmud I had the top cones restored. |

| 1700s | A large fire took place. |

| 1746 | The ZPT and HPT were completely destroyed by a fire. |

| 1773–94 | The castle was restored. |

| 1800s | Canons were fired for the celebration as well as to greet the Sultans. |

| 1804 | An architect analyzed the repair costs of mending the lead roof and rooms. |

| 1819 | Melling drew the lead-covered cones of the three large towers that remained. |

| 1824 | A decision paper was written on the construction, including building a kemer above the tower under the present lead roof, which is to be filled with soil, and building a second new lead roof under the current one. |

| 1830 | The roofs were lost. |

| 1841 | A decision paper is written on painting the small ZPT and repairing the mosque. |

| 1850 | The public living in the castle wanted Meclis-i Vala to repair the gates. |

| 1890 | A photograph of the building was taken by Guillaume Breggen. A district evolved in the fortress. A telegraph, a police station, mansions, and a dock were present. |

| 1918 | Small-scale repair works were carried out. |

| 1940 | A coastal road was constructed in front of the castle. |

| 1938 | A restoration report was prepared. |

| 1918s | Cemal Paşa (minister of marine) intended to build a sea museum. Swedish Architect Maximillien Zürcher began the restoration. |

| 1930 | Albert Gabriel took photos. |

| 1950 | The government placed a cable assembly in this region. The PTT Office building was built on the walls by the sea. A total of 2500 people in 300 houses resided in the castle. |

| 1951 | The graveyard by the shore was partly turned into a casino. |

| 1952 | A beach road was constructed. SPT was opened as a museum. |

| 1953 | The settlements inside were demolished. |

| 1955 | The fortress was restored. |

| 1956 | The walls of the mosque were destroyed, and the area was rebuilt as an amphitheater concert hall. |

| 1960 | The castle has been used as a theater and museum since then. |

The stockaded villages of the Qiang nationality, which comprise watchtowers and watch-houses, are an important part of the cultural heritage of the country similar to Rumeli Hisarı. In 2006, the watchtowers and stockaded villages of the Qiang nationality were placed in the preparatory declaration list of world cultural heritage in China and became a minority architectural heritage with potential value for world cultural heritage. The Wenchuan earthquake, which occurred in 12 May 2008, caused severe damage to the settlements of the Qiangs in the upper reaches of the Min River, including the “Tangping Qiang Village,” which serves a prominent function in the Qiang stockaded villages. We observed the idea “everything for heritage value” in the conservation of this important architectural heritage (Chen, 2012 ). The restoration looks to the future and not to the past. The restoration also has educational and commemorative functions for the youth and future generations (Carbonara, 2012 ).

Obtaining the ideas of the residents may improve the restoration. For instance, the removal of these important buildings may not have occurred if the members of the district inside castle (especially the house owners) had been asked for their ideas (Sotoudeh and Abdullah, 2013 ). Restoration attempts were undertaken despite the insufficiency of information. Fig. 12 shows a part of the bastions before and after restoration.

|

|

|

Fig. 12. Bastions before and after the restoration. |

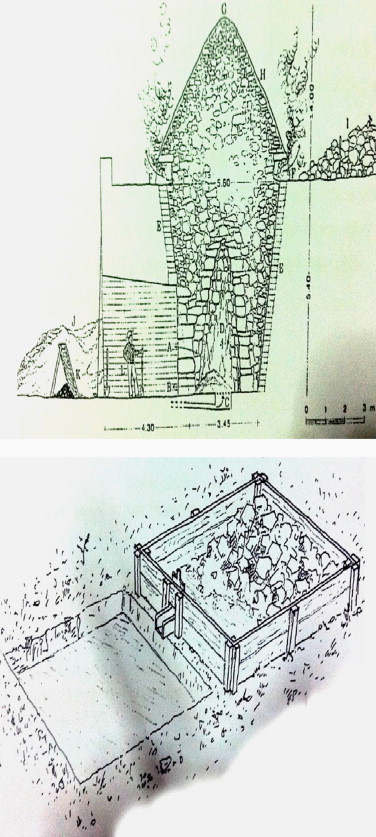

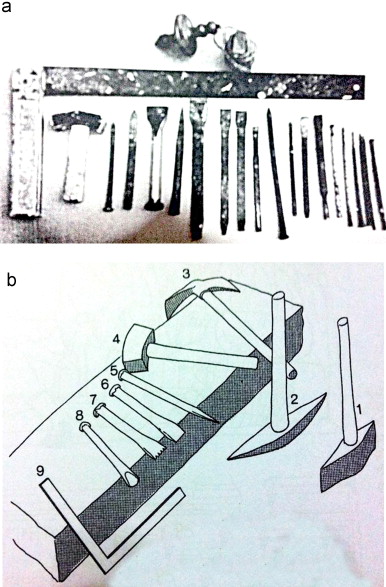

A realistic three-dimensional computer model and rendered pictures should be produced. Production drawings of the castle parts to be repaired may also be drawn. After obtaining the final approval from restoration experts, repair activities should be conducted. Interdisciplinarity, as part of the principle of unity of restoration methods, is viewed as the principal tool for the consistent and complete combination of the different skills necessary for the study and conservation of monuments because the true nature of restoration is a complete fusion of historical and technical–scientific expertise (Carbonara, 2012 ). Restoration activities should also remain loyal to the original building technology of the castle from the 15th century. Historical production methods for wood, lead, and stone should be used. Fig. 13 shows the production method of lime, which is used to bond the rubble-stones of the walls. Similarly, Fig. 14 shows the walling tools (Tayla, 2007 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 13. Lime production, furnace, and sleak pit. |

|

|

|

Fig. 14. |

Finally, a modern material analysis of the building may be conducted, and the restoration may be supported by archeological excavation data (Zhang and Chen, 2013 ; Hou et al ., 2012 ). The architectural heritage conservation activity of China, which is an integral part of the world conservation movement, may be used in benchmark studies (Zhu, 2012 ).

8. Results and discussion

The preservation of Rumeli Hisarı should remain loyal to the original form of the structure as much as possible. The main parts that should be preserved are the mosque of İstanbul at the center of the garden, the lead-covered conic rooftops of the towers, and the springs and front garden walls. The parts that are irrelevant to the historical background of castle must be removed.

First, architectural methods should be used. Technical drawings of the castle and computer-aided analysis should also be conducted. The parts must be placed based on the original structure. The studies of Gabriel, Tamer, and Ayverdi may be useful in this endeavor (Ayverdi, 1974 ; Ayverdi, 1953 ; Ilgaz, 1941 ; Tamer, 2001 ).

In his book “Tarih'te Usul,” Togan suggested the questioning of sources and the removal of irrelevant ones using a certain methodology. However, Dobson and Ziemann, (2009) revealed that scholars transform resources based on their worldview. These researchers do not mention physical objects. However, repairing using a methodological condition is valid for this castle, which is a physical material. The castle may be an example of transformation caused by worldview. The theater building, which is irrelevant to the historical context of the castle, mars the historical value of the building. In an institutional level, the act contradicts the cultural heritage protection philosophy of the United Nations International Childrens Fund (Togan, 1981 ; Dobson and Ziemann, 2009 ).

Therefore, the main actions to be undertaken are as follows: The organization of the garden, which is said to be in line with the old Turkish castle tradition, must be canceled. The elements irrelevant to the history of castle must immediately be removed. The mosque of the castle must be restored. The inner district should also be revitalized if possible. Authorities make relevant comments on the subject (Erişmiş, 2012 ; www.hurriyet.com.tr, 19.08.2006 ).

9. Conclusion

Methodology has an important function in obtaining valid data, and some information sources have numerous mistakes. The castle built during the period of Fatih Sultan Mehmed is one of the key strategic elements of the conquest that ended an age and began a new one.

The building may have been restored numerous times, but the current state of the structure slightly differs from its original form. Several parts of the building were damaged, destroyed, or are about to be destroyed. The restoration of the building should be based on its original design. In such an attempt, state-of-the-art technology must be used, and parallel works in varying countries may be analyzed for the purpose of benchmarking.

In this paper, historical information on the castle is shared, and suggestions on the repair of the castle are given. This study should be further evaluated to contribute to the discussions on the castle, which has a unique place in world history.

References

- Alyanak, 1999 Alyanak, Ş., 1999. On the Methods of Research Bruce Archer. Lyle, F. R. U.S. Patent 5 973 257, 1985. Chemical Abstract, vol. 65. METU Faculty of Architecture Press. Ankara, p. 2870.

- Ayverdi, 1974 E.H. Ayverdi; Osmanlı Mimarisinde Fatih Devri, 855–886, Baha Matbaası, İstanbul (1974), pp. 1451–1481

- Ayverdi, 1953 E.H. Ayverdi; Fatih Devri Mimarisi, İstanbul Fethi Derneği, İstanbul Matbaası, İstanbul (1953)

- Babinger, 1978 F. Babinger; Mehmet the Conqueror and His Time; Princeton University Press, New Jersey (1978)

- Carbonara, 2012 G. Carbonara; An Italian contribution to architectural restoration; Frontiers of Architectural Research, Volume 1 (Issue 1) (2012), pp. 2–9 (March 2012)

- Chen, 2012 T. Chen; The rescue, conservation, and restoration of heritage sites in the ethnic minority areas ravaged by the Wenchuan earthquake; Frontiers of Architectural Research, Volume 1 (Issue 1) (2012), pp. 77–85 (March 2012)

- Dağtekin, 1963 Dağtekin, H., 1963. Rumeli Hisarı Hisar Beççesi Üzerine Yapılan Araştırmalar, Doçentlik Tezi. Ankara Üniversitesi Dil ve Tarih Coğrafya Fakültesi. Ankara.

- Dobson and Ziemann, 2009 M. Dobson, B. Ziemann; Reading Primary Sources: The Interpretation of Texts from 19th and 20th Century History; Taylor & Francis Group, New York (2009)

- Erdenen, 2003 Erdenen, O., 2003. Adım Adım İstanbul: Ahırkapı Feneri'nden Rumeli Hisarı'na 2700 Yıllık Bir Yürüyüş. İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi, İstanbul.

- Eren, 1994 M. Eren; Zağnos Paşa, Zağnos Kültür ve Eğitim Vakfı (1994)

- Erişmiş, 2012 M.C. Erişmiş; A Historical Evaluation On “Rumeli Fortress”: From 15th Century to Present; Lambert Academic Publishing, Saarbrücken (2012)

- Freely, 2011 J. Freely; A History of Otoman Architecture; WIT Press, Boston (2011)

- Genim, 2006 Genim, M.S., 2006. Konstantiniye'den İstanbul'a XIX. Yüzyıl Ortalarından XX. Yüzyıl'a Boğaziçi'nin Rumeli Yakası Fotoğrafları. Suna ve İnan Kıraç Vakfı. İstanbul.

- Hou et al., 2012 W. Hou, W. Wang, X. Yan; The protection project of Hanyuan Hall and Linde Hall of the Daming Palace; Frontiers of Architectural Research, Volume 1 (Issue 1) (2012), pp. 69–76 (March 2012)

- Ilgaz, 1941 A. Ilgaz; İstanbul Türk Kaleleri, Albert Gabriel, Tercüman Gazetesi, İstanbul (1941)

- Kılıçlıoğlu et al., 1992 S. Kılıçlıoğlu, N. Araz, H. Devrim; Meydan Larousse Büyük Lügat ve Ansiklopedi; Sabah Gazetesi, İstanbul (1992)

- Liu, 2013 Y. Liu; A chronology of the field of modern Chinese architectural history; Frontiers of Architectural Research Volume 2; (2013), pp. 1986–2012

- Mustafa Kinali, 2006 Mustafa Kinali, 2006. 〈http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/gundem/4943955_p.asp 〉.

- Nicolle and Hook, 2000 Nicolle, D. Hook, C. (2000). Constantinople 1453 The End of Byzantium, Osprey Publishing, Oxford.

- Sotoudeh and Abdullah, 2013 H. Sotoudeh, M.Z. Abdullah; Evaluation of fitness of design in urban historical context: from the perspectives of residents; Frontiers of Architectural Research, Volume 2 (Issue 1) (2013), pp. 85–93 (March 2013)

- Stanford, 1994 M. Stanford; A Companion to the Study of History; Blackwell, Oxfordshire (1994)

- Sünbüllük, 1950 Sünbüllük, E. S., 1950. İstanbul'un Fethi Yadigârı Beş Yüzüncü Yıldönümü Hatırası. Anadolu ve Rumeli Hisarları Tarihi. Onan Basımevi. İstanbul.

- Tamer, 2001 C. Tamer; Rumeli Hisarı Restorasyonu: belgelerle anılarla 1955-1957; Türkiye Turing Otomobil Kurumu, İstanbul (2001)

- Tayla, 2007 H. Tayla; Geleneksel Türk Mimarisinde Yapı Sistem ve Elemanları, Türkiye Anıt Çevre Turizm Değerlerini Koruma Vakfı, İstanbul (2007)

- Togan, 1981 Togan, Z. V. (1981). Tarih'te Usul, Enderun Kitabevi, İstanbul.

- Tracy, 2000 D.J. Tracy; City Walls: The Urban Enceinte in Global Perspective; Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2000)

- Uyar and Erickson, 2009 M. Uyar, E.J. Erickson; A Military History of the Ottomans: From Osman to Atatürk; Greenwood Publishing Group, Santa Barbara (2009)

- Zhu, 2012 G. Zhu; Chinas architectural heritage conservation movement; Frontiers of Architectural Research, Volume 1 (Issue 1) (2012), pp. 10–22 (March 2012)

- Zhang and Chen, 2013 J. Zhang, W. Chen; Materials analysis of traditional Chinese copper halls using XRF and GIS: Kunming Copper Hall as a case study; Frontiers of Architectural Research, Volume 2 (2013), pp. 74–84 (March)

Document information

Published on 12/05/17

Submitted on 12/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?