Highlights

- We evaluated a possible pathway from social anxiety to GPIU among undergraduates.

- Social anxiety had a direct effect of on GPIU levels among both genders.

- Socially anxious people use SNSs to self-present positively and to be assertive.

- The need for self-presentation could be a pathway to GPIU for socially anxious males.

Abstract

Introduction

Following the theoretical frameworks of the dual-factor model of Facebook use and the Self Determination Theory, the present study hypothesizes that the satisfaction of unmet needs through Social Networking Sites (SNSs) may represent a pathway towards problematic use of Internet communicative services (GPIU) for socially anxious people.

Methods

Four hundred undergraduate students (females = 51.8%; mean age = 22.45 + 2.09) completed three brief scales measuring the satisfaction via SNSs of the need to belong, the need for self-presentation and the need for assertiveness, the Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale 2 and the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale. Structural equation modeling was performed separately for males and females.

Results

A direct effect of social anxiety on GPIU was found among both genders. Socially anxious males and females tend to use SNSs for self-presentation purposes, as well as for the opportunity to be more assertive. The association between social anxiety and GPIU was partially mediated by the need for self-presentation only among males.

Conclusions

The present results extend our understanding of the development of problematic use of Internet communicative services, based on the framework of the dual factor model of Facebook use and the Self Determination Theory. The fulfillment of an unmet need for self-presentation (i.e. the desire to create a positive impression of ones self in others) through SNSs could be one of the possible pathways to GPIU for socially anxious males.

Keywords

Internet addiction;Social networks addiction;Computer-mediated-communication;Need to belong;Self-presentation;Social anxiety

1. Introduction

1.1. Explaining online behavior: the contribution of the psychology of needs

The recent growth in the use of Social Networking Sites (SNSs) has stimulated some hypotheses regarding the psychological needs that underpin such widespread use. The dual-factor model of Facebook use (Nadkarni & Hofmann, 2012) proposes that such use is motivated by two basic social needs: (1) the need to belong, which refers to the intrinsic drive to feel close and accepted by others and gain social acceptance; and (2) the need for self-presentation, which is associated with the process of impression management. The central role that the need to belong has in determining behavior was already underlined by Baumeister and Leary (1995) and, more recently, through the self-determination theory (SDT) proposed by Deci and Ryan, 1985 ; Deci and Ryan, 2000. Whereas these two perspectives focus on the need for belongingness, SDT also postulates two other basic psychological needs: a need for competence (i.e., to feel effective, skillful, and able to master the challenges of life) and a need for autonomy (i.e., to feel that one causes, identifies with, and endorses ones own behavior). Such needs are considered to be truly fundamental since they are believed to elicit goal-oriented behavior designed to satisfy them, beyond the fact that they apply to all people and are not derivative of other motives. As Sheldon and Gunz (2009) state, if the three needs proposed by the SDT are truly fundamental, then “a person who feels lonely should seek company, a person who feels incompetent should try to improve his or her skills, and a person who feels controlled should try to seek greater freedom” (p.1469). In other words, Sheldon and Gunz (2009) propose that if a particular need is currently satisfied, then people should turn their attention to less satisfied needs. It is expected that if a person currently feels very competent but not very connected to others, then she should be pressed to become more connected than to become more competent.

1.2. What unsatisfied needs can socially anxious people meet online?

In keeping with both the dual-factor model of Facebook use and the SDT, the need for belongingness (often called social connectedness in this field) has frequently been reported as one of the primary reasons in terms of motivating web use among socially anxious people (e.g., Roberts, Smith, & Clare, 2000). Individuals with high levels of social anxiety often resolve their desire to avoid painful feelings they anticipate from interpersonal interactions through avoidance and social isolation (e.g. Di Blasi et al., 2014). On the other hand, communicating online has been conceptualized as a safety behavior that allows those with social anxiety to communicate with others while minimizing any potential threats (Erwin, Turk, Heimberg, Fresco, & Hantula, 2004). For socially anxious individuals, communicating with others on the Internet in a text-based manner may allow them to avoid aspects of social situations they fear, while at the same time partially meeting their needs for interpersonal contact and relationships (Erwin et al., 2004). This hypothesis is consistent with empirical findings showing that the fear of being negatively evaluated is generally lower during online interaction than during face-to-face interaction among subjects with high social anxiety (Yen et al., 2012). This is also consistent with the social compensation hypothesis (Valkenburg & Peter, 2009), which states that those with poor friendships will benefit from online communication because threats that are present in face-to-face interactions are not present when interacting online. As Lee and Stapinsky pointed out (2012), “researcher have speculated that the text-based nature of the Internet, and the lack of visual cues when communicating online, allows those with social anxiety to conceal, and therefore control, the aspects of their appearance they perceive as leading to negative evaluation, such as sweating and stammering” (p.198).

Interestingly, whereas the search for acceptance and closeness through computer mediated communication (CMC) among socially anxious people has been theoretically supposed, there is dearth of empirical research on this topic. Moreover, the use of SNSs for self-presentation purposes (the other basic need postulated by the dual-model of Facebook use) that has recently been widely investigated among general population samples, has instead been scarcely explored among people with high socially anxiety levels. This is quite surprising since there is a great consensus about the fact that social anxiety arises from the desire to create a positive impression of ones self in others, along with a lack of self-presentational confidence (e.g., Caplan, 2007 ; Schlenker and Leary, 1982). As a consequence, CMC might represent an ideal tool for communicating among those people who are concerned with displays of imperfection due to fears of being judged and negatively evaluated.

Although the need for belongingness and self-presentation might be useful in explaining SNS use among the general population, the SDT appears to be more exhaustive as a theoretical framework that enables us to understand what socially anxious people are likely to find online. Indeed, among people with social anxiety the need for self-presentation might be better conceptualized as the need for presenting the self as more competent in terms of effectiveness, skillfulness, and ability to master the challenges of life. Moreover, besides the need for belongingness and self-presentation, the personal and social advantages found online by people with high levels of social anxiety might include the possibility for greater autonomy in terms of causes, identification, and endorsement of ones own behavior. They might, in other words, allow individual users to be more assertive. Wolpe, 1958 ; Wolpe, 1973 has long argued that assertion training is beneficial for social phobics, since anxiety and assertion are incompatible. More recently, Azais and Granger (1995) place so much emphasis on the relationship between low levels of assertiveness and social anxiety that they define the social anxiety spectrum as an assertiveness disorder. Empirical research (e.g., Arrindell et al., 1990 ; Orenstein et al., 1975) confirms that assertiveness relates inversely and significantly with measures of interpersonal anxiety among both men and women. Interestingly, low levels of assertiveness have also been found to be positive predictors of a problematic use of the web (Evren, Dalbudak, Evren, & Demirci, 2014).

1.3. Satisfying needs through SNSs: a pathway towards problematic Internet use for socially anxious people?

Caplan, 2007 ; Caplan, 2010 warns us that those who attempt to obtain social benefits or social control via the Internet are also likely to experience negative outcomes and may be at-risk for problematic Internet use. This hypothesis has recently stimulated a variety of research focused on the subjective importance attached to the unique characteristics of CMC by people with social anxiety. Young and Lo (2012) found that those with higher social anxiety trait attach higher self-relevance to CMC attributes (reduced cues, temporal flexibility and anonymity) which, in turn, predicted the willingness to spend time on interacting with people online. Similarly, Casale, Tella, and Fioravanti (2013) found that the lower the level of assertiveness, perceived autonomy, and self-directiveness in thought and action, the higher the subjective importance attached to the temporal flexibility offered by SNSs in message construction. Moreover, the perceived relevance of controllability significantly mediates the relationship between this intrapersonal intelligence ability and preference for online social interaction levels, one of the main cognitive precursors of problematic Internet use related to social networks (GPIU; Caplan, 2010).

The perception of computer mediated communication by people with social anxiety has been deeply explored, but the association between the social benefits found online and the development of GPIU has been scarcely investigated. The few studies available show that a preference for online social interaction arises from a perceived increase in self-presentational efficacy, and a reduction in perceived threat that socially anxious people experience when engaged in online social interaction (Caplan, 2005). However, Weidman et al. (2012) found that individuals who report higher levels of social anxiety and frequently engage in online communication report lower levels of self-esteem satisfaction and higher levels of depression, suggesting that their attempts to compensate for offline social inadequacies may fail to improve well-being. Based on the framework of the SDT, Wong, Yuen, and Li (2014) found that individuals who are psychologically disturbed because their basic needs are not being met are more vulnerable to becoming reliant on the Internet when they seek needs satisfaction from online activities.

The present study aims to extend these results, using the Facebook-use model (Nadkarni & Hofmann, 2012) and the STD as theoretical framework. We hypothesize that satisfying unmet needs through SNSs may represent a pathway towards GPIU for socially anxious people. Three specific needs were supposed to mediate the association between social anxiety and Social Network addiction: the need to belong, the need for self-presentation, and the need for autonomy in terms of major opportunities to be assertive. Specifically, the following direct and indirect hypotheses were proposed and tested:

H1.

Social anxiety is a positive predictor of the need to belong.

H2.

Social anxiety is a positive predictor of the need for self-presentation.

H3.

Social anxiety is a positive predictor of the need for assertiveness.

H4.

The need to belong is a positive predictor of GPIU levels.

H5.

The need for self-presentation is a positive predictor of GPIU levels.

H6.

The need for assertiveness is a positive predictor of GPIU levels.

H7.

There is a positive indirect relationship between social anxiety and GPIU levels that is mediated by the need to belong.

H8.

There is a positive indirect relationship between social anxiety and GPIU levels that is mediated by the need for self-presentation.

H9.

There is a positive indirect relationship between social anxiety and GPIU levels that is mediated by the need for assertiveness.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The participants in the present study were recruited from the University of Florence, Italy. Research assistants explained the study procedures and asked for consent from the participants. Informed consent was received from 400 undergraduates (females = 51.8%; mean age = 22.45 ± 2.09). Data collection consisted of written questionnaires that were filled out in a classroom setting. The participants were guaranteed confidentiality. No rewards or extra-credit were given for the participation.

2.2. Measures

The Italian adaptation (Sica et al., 2007) of the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS) (Mattick & Clarke, 1998) was used. The SIAS subscale focuses specifically upon fears of interacting with others (e.g., I have difficulty making eye contact with others or I am tense while mixing in a group). Each item on the subscale is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (from “not at all” to “extremely”). The Cronbachs alpha in the current study was α = .88.

The degree to which an individual feels satisfied with regard to the need to belong and the need for self-presentation through the use of SNSs was assessed by two brief scales (consisting of 4 items, respectively). A sample item of the need to belong scale is “I feel more accepted by others when communicating in SNSs than in face to face contexts,” whereas a sample item for the need for self-presentation scale is “I can appear more competent when communicating in SNSs than in face to face contexts”. The Cronbachs alpha for the need to belong and the need for self-presentation scales was respectively α = .88 and α = .75. The possibility to be more autonomous, that is the degree to which an individual perceives himself to be more assertive online than in face-to-face contexts, was assessed by a brief scale consisting of 5 items. A sample item for the need for assertiveness scale is “I have less fear to express my opinions to others even when they disagree when communicating in SNSs than in face to face contexts”. The Cronbachs alpha in the current study was α = .83. Each item on the three subscales that assess needs satisfaction was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (from “completely disagree” to “completely agree”).

The Italian adaptation (Fioravanti, Primi, & Casale, 2013) of the Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale 2 (GPIUS2; Caplan, 2010) was used to assess the degree to which an individual experiences the types of cognitions, behaviors, and outcomes that arise because of the unique communicative context of the Internet. In the present study, participants were asked to focus on their use of SNSs. The GPIUS2 contains 15 Likert-type items rated on an 8-point scale (from “definitely disagree” to “definitely agree”). Participants' scores on the 15 items can be added up to create an overall GPIU score. The Cronbachs alpha in the current study was α = .89.

2.3. Data analysis

The hypothesized model was tested for males and females separately via a structural equation modeling analysis using LISREL 8.8 and the Robust Maximum Likelihood (RML) estimation method. The following profile of goodness of fit indices was considered: the χ2 (and its degrees of freedom and p-value), the Standardized Root Mean square Residual (SRMR)

close to 0.09 or lower, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI)

close to 0.95 or higher, and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) less than 0.08 ( Browne & Cudeck, 1993). Indirect effects were tested each with a distribution of product coefficients (P) test developed by MacKinnon, Lockwood, and Hoffman (1998).

3. Results

Descriptive statistics and Pearsons correlations among the study variables are shown in Table 1.

| Total sample (n = 400)M (SD) | Males (n = 193)M (SD) | Females (n = 207)M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Sias | 20.75(10.57) | 20.92(10.87) | 20.59(10.32) | – | .369⁎⁎ | .316⁎⁎ | .439⁎⁎ | .442⁎⁎ |

| (2) Need to belong | 6.75(3.36) | 7.17(3.57) | 6.37(3.12) | .088 | – | .418⁎⁎ | .662⁎⁎ | .488⁎⁎ |

| (3) Need for self-presentation | 8.53(3.49) | 9.24(3.49) | 7.88(3.37) | .199⁎⁎ | .447⁎⁎ | – | .542⁎⁎ | .382⁎⁎ |

| (4) Need for assertiveness | 10.51(4.44) | 11.14(4.38) | 9.93(4.44) | .222⁎⁎ | .557⁎⁎ | .566⁎⁎ | – | .467⁎⁎ |

| (5) GPIUS2 | 32.05(15.49) | 33.89(15.46) | 30.33(15.56) | .224⁎⁎ | .259⁎⁎ | .292⁎⁎ | .277⁎⁎ | – |

Note. Correlations for males (n = 193) are presented above the diagonal, while correlations for females (n = 207) are presented below the diagonal. Sias = Social Interaction Anxiety Scale; GPIUS2 = Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale 2.

⁎⁎. p < .001.

Statistically significant correlations in the expected direction were found between the independent variable, the mediators, and the GPIU levels among both males and females. However, given the different magnitudes of the Pearsons correlation between the predictor and the outcome, the model was tested separately for males and females.

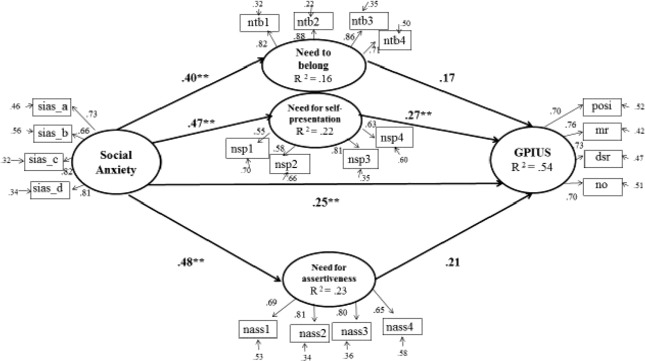

Among males, the assessed structural model produced good fit to the data [χ2 = 256.33, df = 160, p < .001; RMSEA = 0.05 (90% C.I. = 0.04–0.06), CFI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.05]. The variables in the model accounted for the 54% of the variance in GPIU levels. The standardized estimates are shown in Fig. 1.

|

|

|

Fig. 1. Standardized estimates for structural model among males (n = 193). Note. sias_a, sias_b, sias_c, sias_d = Social Interaction Anxiety Scale parcels; ntb1, ntb2, ntb3, ntb4 = need to belong scale items; nsp1, nsp2, nsp3, nsp4 = need for self-presentation scale items; nass1, nass2, nass3, nass4 = need for assertiveness scale items; posi = preference for online social interaction scale; mr = mood regulation scale; dsr = deficient self-regulation scale; no = negative outcomes scale; ** p < .001. |

All coefficients estimated for the measurement model and the estimates of error variances were significant (p < .001). All the hypothesized direct effects were significant (H1, H2, H3, H4, H5 ; H6), with the exception of the direct effect of the need to belong on GPIU (H4) and the direct effect of the need for assertiveness on GPIU (H6). In terms of indirect effects, the current results support the hypothesized indirect relationship between social anxiety and GPIU mediated by the need for self-presentation (H8; p = 11.25, p < .05). However, the data did not support the hypothesized indirect relationships between social anxiety and GPIU as mediated by the need to belong and the need for assertiveness respectively (H7 ; H9). A significant effect of social anxiety on GPIU levels not mediated by the needs to belong, for self-presentation, and for assertiveness was also found.

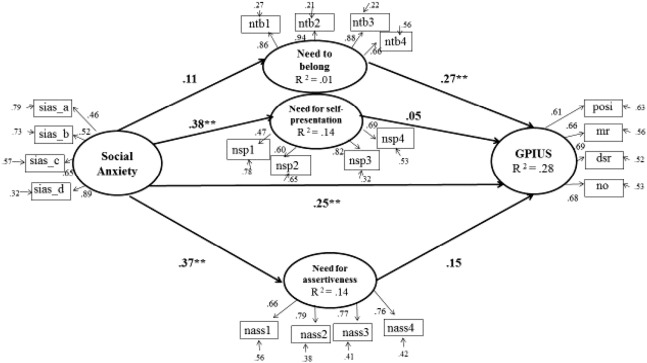

Among females, the assessed structural model produced good fit to the data [χ2 = 270.06, df = 156, p < .001; RMSEA = 0.06 (90% C.I. = 0.05–0.07), CFI = 0.97, SRMR = 0.05]. The variables in the model accounted for the 28% of the variance in GPIU levels. The standardized estimates are shown in Fig. 2.

|

|

|

Fig. 2. Standardized estimates for structural model among females (n = 207). Note. sias_a, sias_b, sias_c, sias_d = Social Interaction Anxiety Scale parcels; ntb1, ntb2, ntb3, ntb4 = need to belong scale items; nsp1, nsp2, nsp3, nsp4 = need for self-presentation scale items; nass1, nass2, nass3, nass4 = need for assertiveness scale items; posi = preference for online social interaction scale; mr = mood regulation scale; dsr = deficient self-regulation scale; no = negative outcomes scale; ** p < .001. |

All coefficients estimated for the measurement model and the estimates of error variances were significant (p < .001). All the hypothesized direct effects were significant (H1, H2, H3, H4, H5 ; H6), with the exception of the direct effect of social anxiety on the need to belong (H1) and the direct effects of the need for self-presentation and the need for assertiveness on GPIU (H5 ; H6). In terms of indirect effects, the current results do not support the hypothesized indirect relationships (H7, H8 ; H9). A significant effect of social anxiety on GPIU levels not mediated by the needs to belong, for self-presentation, and for assertiveness was found.

4. Discussion

The present study hypothesized that satisfying unmet needs through SNSs may represent a pathway towards problematic Internet use for socially anxious people. Such hypothesis derived from previous research (e.g., Caplan, 2007) suggesting a positive association between social anxiety and problematic use of Internet communicative services because of the peculiar characteristics of computer mediated communication. The present study confirmed the already known significant effect of social anxiety on GPIU levels among both males and females, and extended previous findings highlighting how such effect might be mediated by unmet needs in face-to-face interactions among socially anxious people. However, a different pattern emerged for male and female students.

With regard to male students, the need for self-presentation – operationalized in terms of the degree to which the individual was satisfied with the possibility of appearing more competent and avoiding displays of imperfection – has been found to partially explain the association between social anxiety and GPIU levels. Among male students, SNSs' compulsive use seems to be motivated by the satisfaction of the need to avoid public displays of imperfection due to concerns about being negatively judged, which is a core aspect of social anxiety. The mediational role of the need for self-presentation found in the current study confirmed that the perceived increase in self-presentational efficacy available online, experienced by socially anxious people when engaged in online social interactions, could be responsible for a problematic use of Internet communicative services (Caplan, 2005). In line with a previous study (Casale, Fioravanti, Flett, & Hewitt, 2015), CMC could represent an ideal tool for communicating among those people who are concerned over displays of imperfection. The satisfaction of this particular need might represent a pathway from social anxiety to GPIU that is specific to undergraduate males. On the other hand, whereas the present study confirms the role of the need for belongingness as a motivation for the use of the web among socially anxious people (e.g., Roberts et al., 2000), an effect of the satisfaction of the need of closeness on GPIU has not been detected. Similarly, social anxiety predicts the degree to which people regard the online environment as a means of being more assertive, but this opportunity did not lead to a compulsive use of computer mediated communication. In other words, male students with high levels of social anxiety feel that they can satisfy their needs for self-presentation, closeness, and autonomy online. However, only the satisfaction via web of the need to appear more competent might be a risk factor for the development of GPIU among undergraduate males. This result supports the social compensation hypothesis (Valkenburg & Peter, 2009), while similarly suggesting that the use of the web to satisfy unmet needs does not necessarily produce negative effects.

With regard to female students, both the satisfaction of the need for self-presentation and the need for assertiveness motivated the use of the web among socially anxious people. Socially anxious undergraduate females tend to use Internet communicative services as a means of gaining more autonomy, becoming more assertive, being less influenced by the judgment of other people, and fulfilling a desire to appear more competent and skillful than they might be in face-to-face interactions. Nonetheless, satisfying all of these particular needs has not been found to be a pathway to GPIU. Indeed, the satisfaction of the need to belong via the web was the only predictor of the compulsive use of Internet communicative services among female students. This supports previous studies (e.g., Caplan, 2007) which found that those who attempt to obtain social bonds via the Internet are also likely to experience negative outcomes from such use and may be at-risk for problematic Internet use. However, levels of social anxiety were not related to the need for connectedness through online interactions among females. Future studies should clarify the psychosocial difficulties that lead undergraduate females to satisfy their need for connection through the web, since the opportunity offered by CMC has been found to predict GPIU.

The results of the current study, as a whole, support the proposition that the exploration of these unsatisfied needs could be instrumental in explaining the motivational components of Internet use and abuse (Wong et al., 2014). Future research should pay attention to gender differences, as social anxious female students have been found to give less importance to the satisfaction of the need to belong through SNSs, whereas the need to appear more competent has been found to predict GPIU only among males. This is a preliminary result, since no previous study has investigated gender differences in the psychological needs of SNS use among social anxious people. Future studies should also take into consideration other psychological needs, such as the need to escape or the need to control.

One important limitation of the current study is that the cross-sectional data limits the ability to formally test causality. Thus, the mediation findings suggest possible (rather than definitive) casual pathways to problematic use of Internet communicative services for people with social anxiety. Longitudinal studies are needed in order to confirm the directionality of the established associations. Moreover the possibility of a reverse causation could not be excluded. The individuals disposition toward the satisfaction of social needs through SNSs might lead to higher social anxiety in face-to-face relationships and/or it might be related to a higher-order personality factor (e.g., the Openness factor), which in turn could explain social anxiety. An additional limitation involves the measures used to assess the satisfaction of unmet needs through SNSs. Although the internal consistency was good for all the scales, future studies are needed to further evaluate their psychometric properties. Moreover, it should be noted that the generalization of the present results is limited by the fact that the sample was entirely composed by undergraduate students. Further studies conducted on different general population samples as well as on clinical samples are needed. Additionally, subsequent studies ought to replicate the current findings in a clinical sample of socially anxious patients. It is possible that different or stronger associations between the study variables will be found in a treatment-seeking sample.

4.1. Conclusions

The present study extends previous findings regarding the unsatisfied needs that socially anxious people can attain online. As far as we know, this is one of the first studies that has investigated the effect of social anxiety on the tendency to satisfy the need for autonomy and self-presentation in an online setting. The results extend our understanding of the development of problematic use of Internet communicative services among socially anxious people, based on the framework of the dual factor model of Facebook use and self-determination theory.

Role of funding sources

No financial support for the conduct of the research was provided.

Contributors

Silvia Casale and Giulia Fioravanti designed the study and wrote the protocol. Silvia Casale conducted literature searches and provided summaries of previous research studies. Silvia Casale and Giulia Fioravanti conducted the statistical analysis. Silvia Casale wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

No actual and potential conflict of interest exists.

References

- Arrindell et al., 1990 W.A. Arrindell, R. Sanderman, W.J.J.M. Hageman, M.J. Pickersgill, M.G.T. Kwee, H.T. Van der Molen, et al.; Correlates of assertiveness in normal and clinical samples: A multidimensional approach; Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy, 12 (1990), pp. 153–282

- Azais and Granger, 1995 F. Azais, B. Granger; Disorders of assertiveness and social anxiety; Annales Médico-Psychologiques, 153 (1995), pp. 667–675

- Baumeister and Leary, 1995 R.F. Baumeister, M.R. Leary; The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation; Psychological Bulletin, 117 (1995), pp. 497–529

- Browne and Cudeck, 1993 M.W. Browne, R. Cudeck; Alternative ways of assessing model fit; K.A. Bollen, J.S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models, Sage, Newbury Park, CA (1993), pp. 136–162

- Caplan, 2005 S.E. Caplan; A social skill account of problematic Internet use; Journal of Communication, 55 (2005), pp. 721–736

- Caplan, 2007 S.E. Caplan; Relations among loneliness, social anxiety and problematic Internet use; Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 10 (2) (2007), pp. 234–242

- Caplan, 2010 S.E. Caplan; Theory and measurement of generalized problematic Internet use: A two-step approach; Computers in Human Behavior, 25 (2010), pp. 1089–1097

- Casale et al., 2015 S. Casale, G. Fioravanti, G.L. Flett, P.L. Hewitt; Self-presentation styles and problematic use of Internet communicative services: The role of the concerns over behavioral displays of imperfection; Personality and Individual Differences, 76 (2015), pp. 187–192

- Casale et al., 2013 S. Casale, L. Tella, G. Fioravanti; Preference for online social interactions among young people: Direct and indirect effects of emotional intelligence; Personality and Individual Differences, 54 (2013), pp. 524–529

- Deci and Ryan, 1985 E.L. Deci, R.M. Ryan; The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality; Journal of Research in Personality, 19 (1985), pp. 109–134

- Deci and Ryan, 2000 E.L. Deci, R.M. Ryan; The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior; Psychological Inquiry, 11 (2000), pp. 227–268

- Di Blasi et al., 2014 M. Di Blasi, P. Cavani, L. Pavia, R. Lo Baido, S. La Grutta, A. Schimmenti; The relationship between self-image and social anxiety in adolescence; Child and Adolescent Mental Health (2014) http://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12071

- Erwin et al., 2004 B.A. Erwin, C.L. Turk, R.G. Heimberg, D.M. Fresco, D.A. Hantula; The Internet: Home to a severe population of individuals with social anxiety disorder?; Anxiety Disorders, 18 (2004), pp. 629–646

- Evren et al., 2014 C. Evren, E. Dalbudak, B. Evren, A.C. Demirci; High risk of Internet addiction and its relationship with lifetime substance use, psychological and behavioral problems among 10th grade adolescents; Psychiatria Danubina, 26 (2014), pp. 330–339

- Fioravanti et al., 2013 G. Fioravanti, C. Primi, S. Casale; Psychometric evaluation of the Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale 2 in an Italian sample; Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 16 (2013), pp. 761–766

- Lee and Stapinski, 2012 B.W. Lee, L.A. Stapinski; Seeking safety on the Internet: Relationship between social anxiety and problematic Internet use; Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26 (2012), pp. 197–205

- MacKinnon et al., 1998 D.P. MacKinnon, C. Lockwood, J. Hoffman; A new method to test for mediation; Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Prevention Research, Park City, UT (1998)

- Mattick and Clarke, 1998 R.P. Mattick, C.J. Clarke; Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety; Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36 (1998), pp. 455–470

- Nadkarni and Hofmann, 2012 A. Nadkarni, S.G. Hofmann; Why do people use Facebook?; Personality and Individual Differences, 52 (2012), pp. 243–249

- Orenstein et al., 1975 H. Orenstein, E. Orenstein, J.E. Carr; Assertiveness and anxiety: A correlational study; Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 6 (1975), pp. 203–207

- Roberts et al., 2000 L.D. Roberts, L.M. Smith, M.P. Clare; U r a lot bolder on the net; W.R. Crozier (Ed.), Shyness, development, consolidation, and change, Routledge, London (2000), pp. 121–137

- Schlenker and Leary, 1982 B.R. Schlenker, M.R. Leary; Social anxiety and self-presentation: A conceptualization and model; Psychological Bulletin, 92 (1982), pp. 641–669

- Sheldon and Gunz, 2009 K.M. Sheldon, A. Gunz; Psychological needs as basic motives, not just experiential requirements; Journal of Personality, 77 (2009), pp. 1467–1492

- Sica et al., 2007 C. Sica, I. Musoni, L.R. Chiri, B. Bisi, V. Lolli, C. Sighinolfi; Social Phobia Scale (SPS) e Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS): traduzione ed adattamento italiano [Social Phobia Scale (SPS) and Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS): their psychometric properties on Italian population]; Bollettino di Psicologia Applicata, 252 (2007), pp. 59–71

- Valkenburg and Peter, 2009 P.M. Valkenburg, J. Peter; Social consequences of the Internet for adolescents: A decade of research; Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18 (2009), pp. 1–5

- Weidman et al., 2012 A.C. Weidman, K.C. Fernandez, C.A. Levinson, A.A. Augustine, R.J. Larsen, T.L. Rodebaugh; Compensatory Internet use among individuals higher in social anxiety and its implications for well-being; Personality and Individual Differences, 53 (2012), pp. 191–195

- Wolpe, 1958 J. Wolpe; Psychotherapy by reciprocal inhibition; Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA (1958)

- Wolpe, 1973 J. Wolpe; The practice of behavior therapy; Pergamon Press, New York (1973)

- Wong et al., 2014 T. Wong, K. Yuen, W. Li; A basic need theory approach to problematic Internet use and the mediating effect of psychological distress; Frontiers in Psychology, 5 (2014), p. 1562

- Yen et al., 2012 J.Y. Yen, C.F. Yen, C.S. Chen, P.W. Wang, Y.H. Chang, C.H. Ko; Social anxiety in online and real-life interaction and their associated factors; Cyberpsychology, Behavior & Social Networking, 15 (2012), pp. 7–12

- Young and Lo, 2012 C.M.Y. Young, B.C.Y. Lo; Cognitive appraisal mediating relationship between social anxiety and Internet communication in adolescents; Personality and Individual Differences, 52 (2012), pp. 78–83

Document information

Published on 26/05/17

Submitted on 26/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?