- 1. Introduction

Polymers are key materials in aerospace and automotive industries due to their light weight and mechanical versatility. Among them, thermoplastics and thermosets represent the two main classes, with distinct mechanical and thermal properties. Thermosets offer excellent chemical, thermal, and dimensional stability, but their permanent cross-linked network severely limits recyclability posing a challenge in the context of sustainable material design [1]. To overcome this drawback, Leibler et al. introduced vitrimers, a novel class of covalent adaptable networks (CANs) that combine the structural integrity of thermosets with the reprocess ability of thermoplastics [2]. Thanks to dynamic bond exchange reactions activated above the glass transition temperature, vitrimers exhibit stress relaxation [3], reshaping capabilities [4], and self-healing [5], making them highly attractive for advanced structural applications [6].

Effectively exploiting these properties in engineering design requires predictive computational models [7] capable of capturing the complex response of vitrimers under various loading conditions. While the finite element method (FEM) is a widely adopted framework for structural analysis, its accuracy depends on the underlying constitutive models [8]. Conventional damage mechanics describes material degradation through irreversible scalar damage variables, accounting for the progressive loss of stiffness due to mechanical, thermal, or environmental effects [9]. However, vitrimers challenge this paradigm, as their dynamic bond exchange mechanisms enable partial mechanical recovery, a reversible damage process reminiscent of biological self-healing systems [10], which can delay failure and extend the material service life [6].

In this study, we propose a thermodynamically consistent constitutive model for vitrimers that captures the interplay between damage accumulation and healing driven [11] by bond reorganization. The model introduces an effective damage variable to describe the evolving material state, accounting for stress relaxation and partial recovery under mechanical loading. Implemented within a finite element framework, the formulation is validated through numerical simulations, demonstrating its capability to replicate key features of vitrimer behaviour. This approach provides a predictive tool for the design and analysis of self-healing polymer structures.

- 2. Methods

Experimental stress-relaxation tests on vitrimers reveal that stress decay over time, strongly dependent on temperature, is associated with internal molecular reorganisation. In the healing process, this reorganisation acts as a recovery mechanism [5]. Based on this observation, we assume that the rate of stress relaxation corresponds to the healing rate.

Classical energy-based models cannot capture this behaviour, as healing in vitrimers is primarily driven by the dynamic reconfiguration of disulfide bonds at the microscopic scale [12].

To describe this mechanism, we propose a constitutive model capable of predicting the mechanical response of self-healing materials, accounting for both isotropic damage evolution and healing dynamics.

A central aspect of the model is the introduction of a new damage activation function, , which allows us to distinguish between the purely elastic regime and the onset of damage. This function depends on the thermodynamic driving forces and the internal damage variable , which represents the mechanical isotropic damage. These forces are derived to ensure full compliance with the Clausius–Duhem inequality, thus guaranteeing thermodynamic consistency.

Since is defined as an irreversible variable, it cannot decrease in time and therefore cannot capture the material’s ability to recover. For this reason, we introduce an effective damage variable ( ), which accounts for the competition between mechanical degradation and the healing process. This effective damage reflects the actual state of the material and allows the model to describe the gradual recovery of mechanical integrity under suitable conditions.

The constitutive framework is completed by defining the damage evolution law and a threshold function. The resulting equations are solved through an iterative Newton–Raphson scheme, ensuring robustness and accuracy even in complex loading scenarios.

Constitutive Model Coupling Damage and Healing

The proposed constitutive model is based on two scalar internal variables: , ranging between (undamaged state) and (fully damaged state) [11], and , representing the fraction of healed damage, ranging between (unhealed state) and (fully healed from damage).

In self-healing materials (vitrimers), the combines and :

|

|

(1) |

The model accounts for stiffness degradation (damage) and recovery (healing) through the effective stress :

|

|

(2) |

where is the total strain and is the elastic constitutive tensor.

Damage Activation, Evolution and Threshold Functions

The Helmholtz free energy per unit volume is defined as a function of the and :

|

|

(3) |

where , is the elastic energy of the undamaged material. To delineate elastic and damage regimes, an activation function is introduced, defining the elastic domain ( ) and the onset of damage growth ( ), is derived as:

|

|

(4) |

With the thermodynamic force conjugate to damage. is the damage threshold function, a material-specific function that determines the critical thermodynamic force required for damage progression and can take different forms (e.g., linear, quadratic, exponential) depending on the material response to provide a flexible framework for modelling different damage behaviours. These functions are calibrated using the material’s fracture energy ,

|

(5) |

which represents the total energy dissipated during complete failure. The calibration ensures that the damage evolution remains thermodynamically admissible, meaning it satisfies the irreversibility condition (non-negative dissipation ) while matching experimental observations.

The evolution of the damage variable d is governed by the activation function , which defines the boundary between elastic and damage regimes. The loading/unloading conditions are given by:

|

|

(6) |

During active damage growth , the consistency condition must hold, leading to the evolution law:

|

|

(7) |

Numerical Solution via Newton-Raphson Method

For numerical implementation, the nonlinear system is solved iteratively using the Newton-Raphson method. At each time step, the damage variable is updated to satisfy :

|

|

(8) |

The algorithm terminates when the error tolerance is met, ensuring convergence to the damage activation boundary.

Healing Evolution

The healing rate is modeled analogously to stress relaxation, driven by thermally activated bond reorganization:

|

|

(9) |

where , , and are material constants, and is temperature. The evolution of is then:

|

|

(10) |

This framework captures the competition between damage accumulation and healing, enabling the simulation of partial or complete recovery under suitable conditions.

- 3. Results and Discussion

To validate the proposed constitutive model on the vitrimer [13], a dedicated code was developed to verify the correct implementation of the mathematical model. In particular, the constitutive behaviour was tested considering a linear damage threshold function under uniaxial deformation along the X-direction. The analysis was carried out at the integration point level using a single Gauss point.

Subsequently, the constitutive model was implemented within a finite element analysis (FEA) code. After checking its correct behaviour at a Gauss point, it was applied to the simulation of a 3D structure, moving toward the analysis of more realistic and complex structural problems.

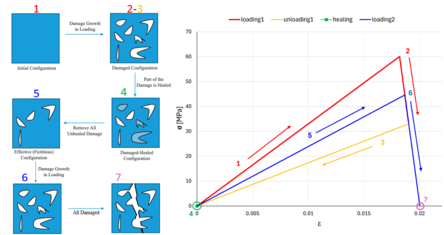

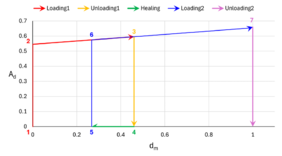

The results, reported in the following figure, are obtained from the code undergoing the material to four stages: loading until partial damage, unloading, healing, and loading until complete failure.

The process showed in Figure 1 begins with loading initiation (1, red), where the material deforms until it exceeds the damage threshold, triggering damage activation (2, red) and causing softening along with stiffness loss ( ≈ 0.46); this is followed by an unloading phase (3, yellow), returning the material to its initial state. Subsequently, a healing temperature ( = 180°C) is applied without deformation, enabling partial recovery (4, green) of effective damage ( = 0.26). In a new loading phase (5, blue), the mechanical damage is updated ( = 0.26), and the material exhibits partial stiffness recovery. However, upon exceeding the critical threshold again (6, blue), further damage accumulates until failure, after which the material unloads in a fully damaged state (7, purple).

Damage is triggered when the activation function , meaning the thermodynamic force exceeds the threshold . Healing, defined as the reverse of damage, healing only activates if damage exists, and its rate is temperature-driven (Eq.9).

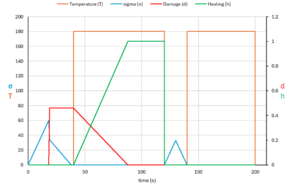

Verified the correct functioning of the developed code for the implementation of the constitutive model, we could move on to analyse a slightly easy 3D structure. The simulation was thermo-mechanically coupled, in which mechanical deformation and thermal activation are applied in a sequential and non-concurrent manner. Specifically, the mechanical loading phase is performed under isothermal conditions (without thermal effects), while the healing stage is thermally activated with the mechanical deformation being deactivated.

The simulation lasts 24 seconds and is divided into several substages. The temperature is defined as a piecewise function: it remains at 0°C from 0 to 2 seconds, rises to 180°C for 20 seconds to activate the healing mechanism, and then returns to 0°C until the end of the simulation. This thermal profile allows to capture the evolution of the damage variable throughout the different phases of the process: mechanical loading from 0 to 1 second, unloading from 1 to 2 seconds, 20 seconds of heating at 180°C without mechanical load to promote healing, and a final 2-second stage replicating the initial loading/unloading conditions.

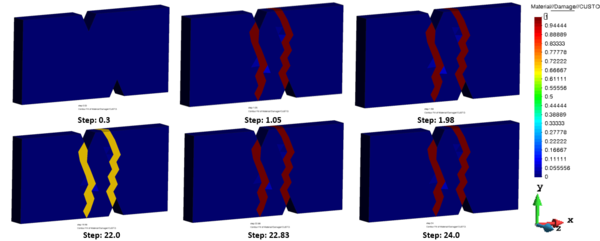

The considered geometry, characterized by the presence of two notches, was divided into 3754 tetrahedra elements of 0.5 mm (931 nodes). The structure, fixed in de left side in X and Z, is initially subjected to a uniaxial tensile loading until complete failure occurs. This is highlighted in the contour plots of Figure 1 where the evolution of the damage variable is shown: undamaged regions are represented in blue (damage = 0), while fully fractured regions are shown in red (damage = 1).

Once the complete fracture is reached (Step 1.98 in Fig 4), the structure is unloaded, and the thermal healing phase is activated. During this phase, the material is heated up to 180°C and maintained at this temperature for a total duration of 20 seconds. As a result, a partial healing effect is observed in the damaged region, with the damage variable progressively decreasing and stabilizing around a value of 0.5 (yellow colour), as shown in Step 22.0 and Step 22.83.

Subsequently, a new mechanical loading is applied on the partially healed structure. Due to the presence of residual damage, the structure fails again. This behaviour demonstrates the capability of the proposed healing model to recover part of the mechanical properties of the material, delaying the final failure with respect to the initial configuration where the structure was completely damaged.

- 4. Conclusion

In this work, a damage-healing constitutive model for vitrimers has been developed and implemented to simulate the damage-healing behaviour of Vitrimers. The model, based on a custom constitutive formulation, allows to describe both the irreversible mechanical degradation and the thermally activated healing phenomena through an effective damage variable. The numerical strategy adopted allows the sequential activation of mechanical deformation and healing, reflecting the experimental evidence where damage occurs under stress while healing is activated, in presence of damage, by heating in the absence of mechanical loading. Furthermore, the formulation required the definition of new thermodynamic driving forces, essential to accurately describe the behaviour of vitrimers.

The results obtained from the simulations confirm the ability of the model to capture the main features of the healing process: after an initial loading phase leading to complete failure, the material undergoes a partial recovery of its mechanical properties during the thermal treatment before being loaded again to failure. The evolution of the damage variable, together with the delayed failure observed after the healing phase, demonstrates the potential of vitrimers to extend the lifetime of structures by recovering part of their load-bearing capacity.

Future developments of this work will focus on extending the model to simulate simultaneous damage and healing processes, exploiting the potential activation of bond exchange reactions by internal residual stresses. In addition, the integration of pressure effects, non-uniform thermal fields and the investigation of complex damage geometries are key aspects to be explored to improve the predictive capabilities of the model. The implementation of such advanced features will be crucial for the application of vitrimers in more realistic scenarios, such as self-healing composites or protective coatings, where multiple healing cycles, damage variability and energy-efficient activation mechanisms need to be addressed.

- 5. References

[1] A. B. Strong, Plastics: materials and processing, 3. ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2006.

[2] D. Montarnal, M. Capelot, F. Tournilhac, and L. Leibler, ‘Silica-Like Malleable Materials from Permanent Organic Networks’, Science, vol. 334, no. 6058, pp. 965–968, Nov. 2011, doi: 10.1126/science.1212648.

[3] D. Sanchez-Rodriguez et al., ‘Processability and reprocessability maps for vitrimers considering thermal degradation and thermal gradients’, Polym. Degrad. Stab., vol. 217, p. 110543, Nov. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2023.110543.

[4] S. Ando, M. Hirano, L. Watakabe, H. Yokoyama, and K. Ito, ‘Environmentally Friendly Sustainable Thermoset Vitrimer-Containing Polyrotaxane’, ACS Mater. Lett., vol. 5, no. 12, pp. 3156–3160, Dec. 2023, doi: 10.1021/acsmaterialslett.3c00895.

[5] D. Sanchez-Rodriguez et al., ‘Time-temperature-transformation diagrams from isoconversional kinetic analyses applied to the processing and reprocessing of vitrimers’, Thermochim. Acta, vol. 736, p. 179744, Jun. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.tca.2024.179744.

[6] J. Zheng et al., ‘Vitrimers: Current research trends and their emerging applications’, Mater. Today, vol. 51, pp. 586–625, Dec. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.mattod.2021.07.003.

[7] S. S. M. Wong, Computational methods in physics and engineering, 2. ed. Singapore: World Scientific, 1997.

[8] E. Oñate, Structural Analysis with the Finite Element Method Linear Statics. in Lecture Notes on Numerical Methods in Engineering and Sciences. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2013. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-8743-1.

[9] S. Oller, Nonlinear Dynamics of Structures. in Lecture Notes on Numerical Methods in Engineering and Sciences. Cham: Springer, 2014. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-05194-9.

[10] E. Comellas, T. C. Gasser, F. J. Bellomo, and S. Oller, ‘A homeostatic-driven turnover remodelling constitutive model for healing in soft tissues’, J. R. Soc. Interface, vol. 13, no. 116, p. 20151081, Mar. 2016, doi: 10.1098/rsif.2015.1081.

[11] H. Shahsavari, M. Baghani, R. Naghdabadi, and S. Sohrabpour, ‘A thermodynamically consistent viscoelastic–viscoplastic constitutive model for self-healing materials’, J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct., vol. 29, no. 6, pp. 1065–1080, Apr. 2018, doi: 10.1177/1045389X17730914.

[12] I. Azcune and I. Odriozola, ‘Aromatic disulfide crosslinks in polymer systems: Self-healing, reprocessability, recyclability and more’, Eur. Polym. J., vol. 84, pp. 147–160, Nov. 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2016.09.023.

[13] L. An, R. Xiang, and H. Bai, ‘Tensile, compressive, flexural, torsional and impact properties of vitrimer’, Polymer, vol. 307, p. 127301, Jul. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2024.127301.

Document information

Accepted on 23/07/25

Submitted on 12/04/25

Licence: Other