1. Problem understanding and motivation

Focusing on the civil aviation decarbonization, we can proudly say that our last generation aircrafts emit 20-25% less CO2 per seat/kilometre compared to the previous generation airplanes (before 2015), thanks to continuous aircraft developments with respect to engines, aerodynamics and material technologies. Lightweight composite materials like CFRP (Carbon Fiber Reinforced Plastics) have contributed significantly to reach the current aircraft emissions and in-service operation performances.

Thus, it is a fact that the use of composites lowers the aircraft operational environmental footprint compared to aluminum, due to weight saving and less part replacement needed due to better corrosion and fatigue behavior. However, in the other life cycle assessment phases of composite materials, e.g. raw material production, design, supply chain, manufacturing and end of life, composites have a comparably high environmental burden. This is related to e.g. dependency on currently oil derived precursors and chemicals (some in the radar of the Health & Safety regulation, e.g. REACH) for fiber and resins, energy intensity of carbon fiber and part manufacturing, and limited economical viable solutions for recycling.

Triggered by these antagonizing facts, the legitimate question arises, if we should use such a kind of material in the future of aviation. In the past the answer was often related to making products economically more attractive to the operator by saving fuel and maintenance costs. However, today the decision criteria has to be complemented by sustainability. This decision implies complex considerations about socioeconomic, human rights and for sure environmental integrity. The latter is often evaluated in Life Cycle Assessments (LCA) considering the global warming potential - GWP (kg CO2-eq), as well as other indicators, e.g. energy consumption, land use, renewability, abiotic resource depletion, water demand, ecotoxicity, hazardous substances, waste circularity…. The complex interactions between them have been studied extensively in literature as well as in research projects, then, the knowledge in this field is still growing.

Thus, the second question we should reflect about is: can we achieve the goal of sustainable CFRP?. The short answer is: Yes, we can. There are some basic leverages that can be employed, which will lead to a successive reduction of environmental footprint, like the usage of green energy, bio-based feedstocks, power to X technologies as well as new technologies (TRL<3), which can create a corridor for CO2 saving for CFRP production to reach similar or even lower value than aluminium before 2050, taking also into account CO2 reduction corridor for Al alloys.

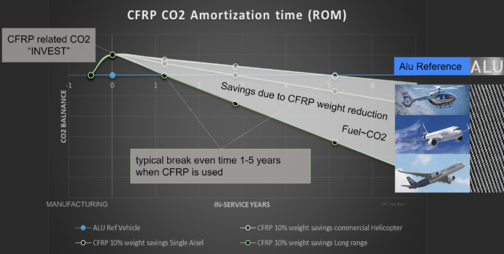

The next relevant question is: are composites an inevitable element to reach current and future commercial aviation sustainability targets?. The easy answer is they have the highest known lightweight potential among all structural materials, which correlates directly with CO2 emission saving, and one can define a CO2 related amortization time similarly to the cost amortization time. As shown in figure 1 the as of today undesirable initial higher CO2 emitted due to usage of CFRP to produce aircraft amortizes very early in the lifespan of an aircraft. As a rule of thumb, assuming a under-estimated 10% aircraft weight saving due to use of CFRP vs. aluminium and without considering buy to fly ratio values, the break even is as early as 1 year for a long range aircraft and about 5 years for an Helicopter, see figure 1. With regard to the service life of about 20-30 years this considerable positive impact of CFRP can not be ignored as it sums up to 3-25 times higher savings than initial drawbacks.

As these rough estimations are considering classic kerosene propelled vehicles, it is only valid for short to medium term timeframe. But this is even more relevant for next gen aircrafts based on cleaner but costly propulsion energies (SAF or H2), thus, the undesirable initial primary energy invested due to CFRP use will amortize even quicker, with the same 10% weight saving. As a rule of thumb break even is estimated to be well below 2 years, and with regard to the 20-30 years life this positive impact of CFRP will sum-up 15-50 times higher savings than initial drawbacks.

Additionally, it is relevant to mention other motivations to improve the carbon footprint of aircraft composites, specifically CFRP, like regulatory pressure, CO2 emissions targets adopted by all companies in the value chain (Scope 1, 2 and 3), social responsibility and ESG - Environmental Social Governance, and opportunities related for example with composite circular economy.

2. As-is situation

2.1 Raw material production

Currently, most used composites in airframes are carbon fiber epoxy resin composites, mainly in the prepreg format, due to their specific properties and industrial maturity. Both the carbon fiber and the epoxy are obtained from fossil feedstocks:

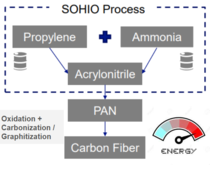

- Carbon fiber: is produced from poly-acrilonitrile (PAN) precursor, following a high energy demanding process, which includes following steps: oxidation (220-270ºC, 1 to 2 hours), carbonization (700-1500ºC, 2 to 10 min), (optionally) graphitization (2000-3000ºC, 1 min) and sizing. The precursor PAN is obtained from acrylonitrile, which is produced by Sohio process from propylene and ammonia, which both come from fossil resources. The carbon footprint of carbon fiber is 20-50 kg CO2 eq / kg [1], depending on type of energy used to produce the fiber, and it comes mainly from the processing of the PAN (polymerization, spinning…), approximately 40%, as well as the process to obtain the carbon fiber, which involves around 45% of the total impact, and most of the carbon fiber footprint is electricity and thermal energy (80%). It is important to remark that these data are rough estimations, provided by carbon fiber suppliers, then, can be different depending on the supplier. The trend is positive due to the higher use of more renewable energy to produce carbon fibers. See figure 2 a).

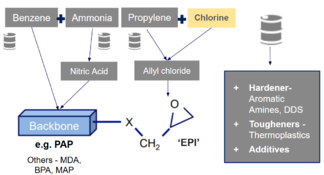

- Epoxy resin: the base epoxy monomer comes from fossil feedstocks, i.e. from chemical intermediaries obtained from benzene, propylene and ammonia, other components of the resin are the hardener, tougheners and additives, as it can be seen in following figure 2 b).

|

- Prepreg: are obtained from unidirectional carbon fiber or fabrics and epoxy resin with hardener (mono-component), by following processes:

- Filming route: in hot-melt mixing, which is the most commonly used, there are no solvents and so direct emissions are zero. If solvent coating is used (rare) then solvent is driven off after the coating stage. Paper used to support the films are ‘release liners’. UD carbon fiber prepreg is exclusively made following this process. As a rough estimation, the prepreg carbon footprint comes still mainly from the PAN and carbon fiber processing, while the production of the resin / film and prepreg involves only around 15% of the total prepreg carbon footprint.

- Solution / tower: the resin is mixed and dissolved in solvent, the carbon fiber fabric is immersed through lacquer, then, lacquer is dried (solvent lost), finally, the prepreg is rolled up.

2.2 Part production

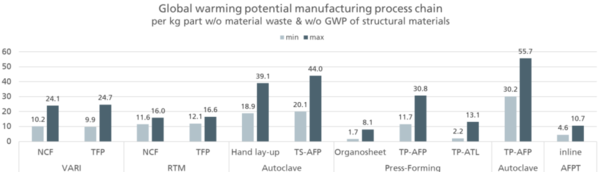

Thermoset and thermoplastic carbon fiber composite parts can be manufactured by different manufacturing processes, including in and out-of-autoclave processes. A preliminary analysis of the energy consumption and the resulting global warming potential (CO2eq / kg of composite part) of typical processing routes to obtain CFRP structures for aerospace applications was performed in collaboration with Fraunhofer (figure 3), considering following assumptions:

- Scenario 2018: electricity grid mix of the European Union, natural gas as fuel for the production of thermal energy and steam are recognized. The trend for the future is positive due to the use of greener energy sources.

- Relevant production parameters were varied (maximum & minimum energy consumption). Some parameters remain constant, e.g. carbon fiber volume content (60%), fiber and resin density, part dimensions (length: 1m, width: 1m, thickness: 2 mm).

- Data used were most measured in previous projects and published [2-4]. Only data used for thermal consolidation in an autoclave comes from the literature [5].

- AFP + Autoclave processes (either with thermoset or thermoplastic carbon fiber materials) shows the highest GWP. A maximum value of 55.7 kg CO2eq / kg part can be obtained for thermoplastic prepreg and 44 kg CO2eq / kg part for thermoset prepreg.

- However, as expected, out of autoclave processes, show lower GWP. In case of thermoplastic CFRP: inline AFPT shows a maximum value of 10.7 kg CO2eq / kg part, while ATL + press forming has a maximum of 13.1 kg CO2eq / kg part. For thermoset CFRP: RTM maximum values are 16 kg CO2eq / kg part (NCF) and 16.6 kg CO2eq / kg part (TFP).

2.3 Waste generation

It is key to make a clear differentiation between production and end of life wastes. In case of production scrap, which is currently either landfilled or incinerated, to mention following types:

- Structural materials: CFRP (carbon fiber reinforced plastics) - epoxy carbon fiber prepregs - uncured and cured, liquid epoxy resin, dry carbon fiber textiles, mono and multi-layer scraps, surface layers integrated with CFRP: copper foils, glass fiber epoxy prepregs, aramid / glass fiber honeycomb, epoxy film / paste adhesives.

- Auxiliary materials: vacuum bags (polyamide), breathers (polyester, polyamide), release films (PTFE, ETFE…).

Regarding end of life (EoL) scrap - It is relevant to mention Airbus PAMELA Project to develop a process for Advanced Management of End-of-Life aircraft, started in 2006 [6]. Thanks to this project, the current end of life metallic airframe is deconstructed in TARMAC Aerosave to segregate different metal types, which are sent for recycling and valorization. However, end of life composite structural or cabin parts are still landfilled currently. It is also important to note that current Airbus aircrafts that have already reached end of life are: A320, A330/40 and A380, which include following key composite parts:

- Cabin: GFRP - phenolic resin + aramid honeycomb, many other non-metallic materiales

- Airframe: mainly CFRP - epoxy resin, all models: HTP & VTP, belly fairing, movables, A380: additionally includes the Section 19 & 19.1, Central Wing Box, Rear Pressure Bulkhead.

On top, the perspective for the future shows a high increase of the end of life composites due to last generation aircrafts with higher composite content, e.g. A350 (+CFRP fuselage & wing) or A220 (+CFRP wing), with EoL from 2028 / 2030, as well as the expectation to further composite use in next generation single aisle aircraft as explained in paragraph 1.

Based on the Airbus Global Market Forecast 2024 [7], the estimated EoL composite waste to be retired between 2023-2043 from passenger aircrafts is 250.000 Tons, 65% from structure and the rest from cabin. Additionally, it can be highlighted that, currently, a maximum of 5% of all thermoset composite waste is recycled [8], a figure that can be extrapolated to the aeronautical sector and, in this case, all the recycled composite material is coming from production waste.

3. Opportunities and trends

3.1 Biosourced composites

The biobased chemical industry is a fast growing sector. In fact, from 2008 to 2019, the biobased chemicals and plastics sector in the EU-28 has increased its turnover by 68 % [9]. As summarized in paragraph 2.1, today's composite materials rely on the petrochemical industry to produce carbon fibers and resins. But it is demonstrated that carbon fibers and resins can also be obtained from sustainable biosources or biomass, which involve a positive environmental impact and can even contribute with a negative carbon footprint. Among the biosourced composites, drop-in (same material from biosources) are always preferred versus look-alike (different materials, from different biosourced molecules or raw materials), since this last approach can lead to a performance decrease, therefore, the increase of in-service footprint will be the critical consequence. So the overall carbon footprint for any technology switch has to be carefully considered.

In order to secure the use of biosourced feedstocks, raw materials and intermediary chemicals in the supply chain (resins and/or fibers), a chain of custody model needs to be implemented. Among the different models, the one which is fully recognized in the chemical industry and, then, can be applicable to composites is the mass balance. This model involves the mixing of biobased or circular feedstocks with standard fossil based feedstocks at the beginning production process and allocate or attribute them to one or several final materials or products, thus, this approach does not guarantee a specific biosourced or circular content in a final material lot. This calculation-based principle offers multiple advantages, mainly the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and fossil feedstocks, while the final products or materials remain the same. Then, the mass balancing easily enables the drop-in approach but it is not mandatory for it and must not be mixed up with it. Additionally, a mass balance certification of the material, e.g. carbon fiber or resin, is needed by an independent body [10].

Main challenges to be highlighted in the implementation of mass balance carbon fibers and epoxy resins: likely final material cost increase associated with the availability of biosources, value assessment for the OEM or final user, secure traceability and control of the materials.

3.2 Substance compliance

Environmental regulation organizations, such as ECHA (European Chemicals Agency) with REACH regulation, are progressively more actively working for the safe use of chemicals, which is heavily impacting the aircraft industry in recent years (e.g. chromates). The aviation industry must comply with the airworthiness requirements derived from EU Regulation No 216/2008 in Europe - EASA (European Aviation Safety Agency), and with similar airworthiness requirements in all countries where aeronautical products are sold. All components, from seats and galleys to bolts, equipment, materials and processes incorporated in an aircraft fulfil specific functions and must be qualified and certified. If a substance used in a material, process, component or equipment needs to be changed, an extensive process has to be followed in order to be compliant with the airworthiness requirements. In this frame, a cooperation memo between ECHA and EASA has been published in 2017 to establish a direct channel and collaboration between both entities [11].

Thus, in order to be compliant with this regulation, several anticipation and derisking activities have arisen, especially in the composite area, to secure the aviation industry. Current substances under REACH radar are: formaldehyde (used to produce phenolic resin used in interior composites), BPA - Bisphenol A (precursor to obtain epoxy resin), PFAS - per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (present in auxiliary materials to produce composites, like release films), etc. Moreover, for those materials impacted by the current main proposals launched, PFAS and BPA, advocacy activities are ongoing. Finally, it is also key to pay attention to substance compliance for biosourced composites, since bioderived does not mean substance compliant.

3.3 Industrial footprint

Regarding industrial eco-efficiency in composite production in terms of energy consumption, we can split between initiatives by materials and part suppliers. Additionally, it is also important to highlight that all of these initiatives will also involve an important benefit to reach the future demanding targets in terms of production rate and cost.

- PAN-based carbon fiber production technologies by material suppliers, e.g. microwave heating, which can save around 90% energy in first phase of carbon fiber production, or electrical heating, work on the precursor at molecular level to steer the carbonization phase towards the lowest temperature range (additives, catalyst,...), alternative precursor sourcing, ie: lignin/cellulose, the usual costly multiple purification steps of PAN (in total 5) could be replaced only by enzymatic purification…

- In terms of composite component production by OEMs, key fields are: development of out of autoclave technologies, relaxation of the storage and clean area conditions to work with thermoset prepregs, net shape technologies, fast curing and lay-up materials and technos.

3.4 Recycling and recyclate technologies

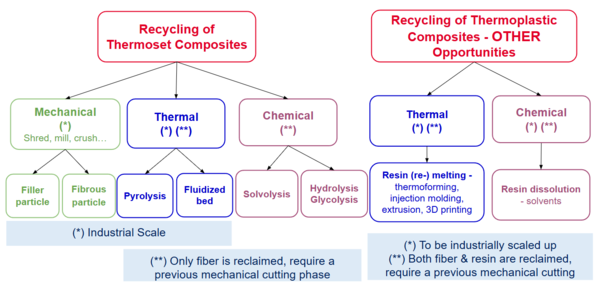

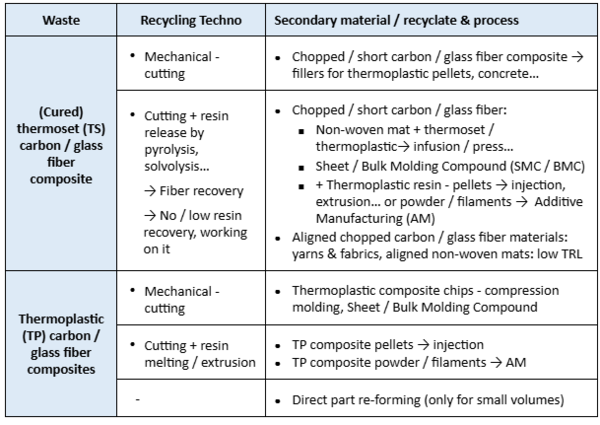

Current recycling technologies to valorize carbon fiber composites are summarized in figure 4, for both thermoset and thermoplastic composites. In case of thermoplastics, due to the resin nature that can be remelted, there are additional opportunities to recover both resin and fiber.

But the next key step after recycling is the production of recyclates or secondary materials from recovered or recycled carbon fibers or composites, suitable to obtain new parts (see table 1).

3.5 Recyclable thermoset resins

As mentioned in previous paragraphs one of the key disadvantages of current thermoset composite materials mainly used in aerospace is the difficulty to recycle crosslinked resins. Although thermoplastic composites can overcome this disadvantage to some degree, as indicated in paragraph 3.4, their use comes with some disadvantages versus thermoset composites, like the higher material cost and processing temperature, as well as the lack of compatible auxiliary materials .

Thus, one of the current key trends and research focus in the composite industry is the development of reshapable, recyclable and reparable polymer materials or resins. Several alternatives are being developed in order to obtain new thermoset resin formulations that exhibit strength, durability and chemical resistance approaching that of traditional thermosets, while exhibiting end of life recyclability, reprocessability and repairability capabilities.

Vitrimers, which are associative covalent adaptive networks (CAN) based on exchangeable dynamic covalent bonds, have been identified as potential candidates because they offer a promising solution by enabling re-processability while maintaining the main advantages of current thermoset resin (processing conditions/temperature, means, mechanical properties...). Although several vitrimers are arising in the market, they do not meet yet the aeronautical requirements, e.g. in terms of glass transition temperature.

Therefore, CIDETEC in collaboration with Airbus are developing vitrimers for aircraft application from 2021, based on dynamic aromatic disulfide bonds. Currently, this research is still ongoing by means of producing a 100% dynamic vitrimer epoxy formulation with competitive mechanical properties and exploring their capabilities to be shipped, stored and used at >0 ºC or ultimately at room temperature for unlimited time, which we have called enduring prepreg (unlike thermoset materials, which need -18ºC storage and have limited shelf life), minimising the production energy consumption, then, positioning them closer to thermoplastic resins [12].

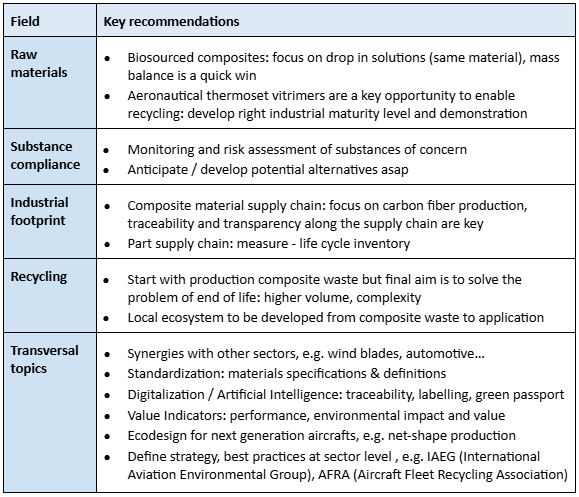

4. Recommendations

Although composites are the material of choice for current and next generation aircrafts, due to lightweight capabilities leading to non-questionable CO2 saving during operational life, the full end to end lifecycle of the composites need to be also considered at the right priority to anticipate future regulations and social pressure, which can affect aeronautical composite materials and industry as we know them today.

It is very relevant to work on more sustainable solutions or improvement areas for current flying composites, without involving any detrimental effect in their performance, since the impact on the end to end carbon footprint will be much higher. However, it is even more relevant to apply lessons learnt from them, as well as to consider new more sustainable composite opportunities and technologies for next generation aircraft from the very beginning, e.g. initial research and design phase. From all the fields considered in the article, recommendations summarized in table 2 can be derived.

5. Acknowledgments

Authors would like to acknowledge the contribution to this article of Uwe Beier, from Airbus Central Research & Technology (CRT), and David Tilbrook, from Hexcel, for providing key information and insights. Also, thanks to Nerea Markaide and Alaitz Rekondo from CIDETEC regarding the development of aeronautical vitrimers in collaboration with Airbus. This development was started in OPTIMUS project, funded by the Spanish funding body CDTI (‘Centro para el Desarrollo Tecnológico Industrial’) with grant number MIG-20211010, through the 2021 call for granting funds for Science and Innovation Missions (‘Misiones’), within the Recovery, Resilience and Transformation Plan (funded by the Next Generation EU funds – Recovery and Resilience Mechanism) and the State Program to catalyze the Innovation and Business Leadership of the State Plan for Scientific and Technical Research and Innovation 2021-2023. Vitrimer resin development between Airbus and CIDETEC is currently ongoing in the EconCARBon project funded by CDTI with support from the Ministry of Science and Innovation under grant number MIG-20241002, as part of the 2024 call for the Missions of Science and Innovation Program. It is also integrated into the Scientific, Technical, and Innovation Research Plan 2024-2027, under the Recovery, Transformation, and Resilience Plan.

6. Bibliography

[1] https://www.cf-composites.toray/aboutus/sustainability/lci.html

[2] Andrea Hohmann, Stefan Albrecht, Jan Paul Lindner, Bernhard Voringer, Philip Leistner. Resource efficiency and environmental impact of fiber reinforced plastic processing technologies. Production Engineer-ing 2018;12(3).

[3] CORDIS. In situ manufactured carbon-thermoplast curved stiffened panel. EU-project INSCAPE. [March 15, 2023.493Z]; Available from:https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/686894/de.

[4] Hohmann A. Ökobilanzielle Untersuchung von Herstellungsverfahren für CFK-Strukturen zur Identifikation von Optimierungspotentialen. Dissertation, Technische Universität München.

[5] Katsiropoulos CV, Loukopoulos A, Pantelakis SG. Comparative Environmental and Cost Analysis of Alternative Production Scenarios Associated with a Helicopter’s Canopy. Aerospace 2019;6(1):3.

[6] https://aircraft.airbus.com/en/newsroom/news/2022-11-end-of-life-reusing-recycling-rethinking

[7] https://www.airbus.com/sites/g/files/jlcbta136/files/2024-07/GMF%202024-2043%20Presentation_4DTS.pdf

[9] Olaf Porc, Nicolas Hark, Michael Carus (nova-Institut), Dr. Dirk Carrez (BIC), European Bioeconomy in Figures 2008–2019, October 2022

[10] https://www.iscc-system.org/certification/chain-of-custody/mass-balance/

[11] https://echa.europa.eu/-/echa-and-easa-signed-an-agreement-of-cooperation

[12] E. del Puerto-Nevado, T. Blanco-Varela, N. Markaide, A. Ruiz de Luzuriaga, A.M. Salaberria. Aeronautical Vitrimer Resin for Prepreg Application. ECCM21 – 21st European Conference on Composite Materials

Document information

Published on 21/10/25

Accepted on 11/08/25

Submitted on 22/04/25

Volume 09 - Comunicaciones MatComp25 (2025), Issue Núm. 2 - Reciclaje y Sostenibilidad, 2025

DOI: 10.23967/r.matcomp.2025.09.14

Licence: Other