Summary

Background/Objective

Pilonidal sinus treatment includes various surgical and minimally invasive procedures, but there is still no standard treatment. Flap reconstructions and minimally invasive treatment options such as crystallized phenol application have recently been in the center of interest. The aim of this study is to compare crystallized phenol application as a minimally invasive treatment with modified Limberg flap reconstruction from many aspects.

Methods

Thirty-seven patients diagnosed with pilonidal sinus and treated with modified Limberg flap reconstruction, and 44 patients treated with crystallized phenol application were evaluated retrospectively in terms of age, sex, length of stay in hospital postoperatively, wound complications, and the cause and rate of recurrence.

Results

Length of hospital stay was decreased and no postoperative incision problems were found in the group treated with crystallized phenol application (p < 0.001 and p = 0.011, respectively). The difference between the groups in terms of recurrence rate was not statistically significant (p = 0.173). Although the recurrence rate was found to be higher in the patient group treated once with crystallized phenol application, the success rate following multiple applications of crystallized phenol was found to be 94.5%. Higher body mass index (> 24.9 kg/m2) and surgical site infection were strongly correlated with recurrence rate (p < 0.001).

Discussion

Crystallized phenol application is a good alternative to the modified Limberg flap procedure and other surgical procedures, because it has several advantages such as being a minimally invasive procedure performed under local anesthesia with higher success rate after multiple applications, decreased length of stay in hospital, and minimal scar tissue formation.

Keywords

Crystallized phenol;treatment;pilonidal disease;flap surgery

1. Introduction

Pilonidal sinus is a common disease of the sacrococcygeal region that is usually seen among young men. Numerous theories have been presented to explain its etiology, but the widely accepted view is that the disease is acquired.1 Although some of the patients experience severe acute pain, the disease manifests itself with chronic-continuous discharge. Because there is no standard treatment, and it has a high recurrence rate, studies on pilonidal sinus have a potential value.2 Treatment options of pilonidal sinus vary from minimally invasive surgical interventions to complicated flap techniques; yet none of them were suggested as the most effective procedure so far.3 Although some studies report that flap techniques are associated with lower recurrence rates and higher patient satisfaction in comparison with other surgical procedures, there are several studies suggesting that flap techniques are extreme surgical procedures.4; 5 ; 6 Modified Limberg flap reconstruction was first described by Mentes et al7 in 2004. In this technique, the lower edge of the incision is shifted laterally from the midline to prevent the inferomedial recurrence seen in classical Limberg flap reconstruction. The lower recurrence and complication rates in modified Limberg flap reconstruction in comparison with classical Limberg flap reconstruction8 ; 9 and other conversional flap reconstruction techniques10 ; 11 were reported in several studies.

The ideal treatment of pilonidal sinus disease should include minimum tissue excision with a lower recurrence rate. Additionally, the postoperative period should include short length of stay in the hospital, fast recovery back to normal life, minimum workforce loss, and minimal scar tissue formation. Thus, easily performed treatments such as pit excision, mechanical clearance of the sinus tract, and chemical therapies became popular.12

Phenol, also known as carbolic acid, has antiseptic, anesthetic, and strong sclerotic features. Phenol treatment is one of the current popular conservative options to treat pilonidal sinus. It can be used both in liquid or crystallized form.13

In the present study, crystallized phenol application as a minimally invasive treatment was compared with modified Limberg flap reconstruction as a current surgical treatment of pilonidal sinus from many aspects.

2. Methods

Between December 2013 and July 2015, a total of 94 patients were diagnosed with pilonidal sinus and treated at Dumlupınar University Evliya Çelebi Research and Education Hospital in Kutahya, Turkey. Their details were examined retrospectively in terms of age, sex, length of stay in hospital postoperatively, wound complications, recurrence rate, and recurrence causes.

Patients aged between 18 years and 65 years with pilonidal sinus disease who have not undergone any prior treatment were included in the study. The exclusion criteria include being under treatment for steroids, application to the clinic with a recurrence disease, being diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, being diagnosed with abscess formation following pilonidal disease, and concomitant pilonidal disease with malignant conditions.

Deep sinuses are not accepted as a contraindication for phenol treatment and can be managed as easily as superficial ones. Because phenol contact with cavity wall is enough to induce this effect, even a small amount of crystals can easily fill almost every cavity of pilonidal sinuses by melting at body temperature. Thus, patients with deep sinuses were not excluded from the study.

Forty-four of the patients were treated with modified Limberg flap reconstruction, whereas 37 patients were treated with crystallized phenol application. The patients with a higher body mass index (BMI; > 24.9 kg/m2) were grouped as overweight according to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines.14

A written consent was obtained from all participants. No patient identity information was disclosed, and there was no need for ethical approval as this is a retrospective study.

2.1. Surgical procedures

2.1.1. Crystallized phenol application

Crystallized phenol application was performed in 37 of the patients as described by Akan et al.13 After the application of local anesthetic, a millimetric circumferential incision was made to excise the pits with a fine blade. With the help of a curved clamp hair, debris and granulation tissue were removed from the sinus tract and the tract is curetted. Prior to crystallized phenol application, a pomade containing nitrofurantoin was applied in order to protect the surrounding tissue, and after that crystallized phenol particles were inserted to the tract with the help of a clamp (Figure 1). After dressing, the procedure was terminated and the patient was discharged immediately. The application was performed by an experienced surgical team.

|

|

|

Figure 1. After the pit excision and curettage of the sinus. |

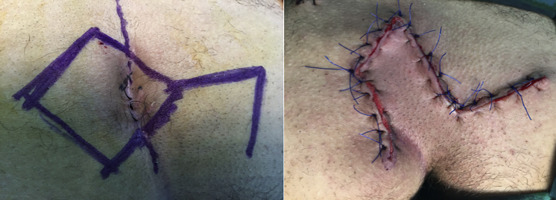

2.1.2. Modified Limberg flap reconstruction group

The operation was performed as described by Mentes et al.7 The skin incision was first marked out with a sterile pen and ruler, then a rhomboid excision including postsacral fascia was performed to excise all of the sinus tracts. The caudal end of the excision was extended 2 cm laterally from the midline to the opposite side of the donor area of the flap. A fasciocutaneous flap was prepared from the right or the left side of the gluteal region including gluteal fascia, then the flap was placed over a hemovac drain and sutured to the presacral fascia (Figures 2A and 2B). The operations were performed by the same surgical team.

|

|

|

Figure 2. After modified Limberg flap reconstruction. |

2.2. Statistical analysis

Normality of the distribution of variables was determined using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Data were expressed as numbers and percentages for categorical variables and mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables. Normally distributed data were compared using Student t test, whereas data with skewed distribution were compared with Kruskal–Wallis test. Statistical differences were considered significant when p was < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 18 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

Forty-four of the patients were treated with modified Limberg flap reconstruction, whereas 37 patients were treated with crystallized phenol application. Female patients in the group treated with modified Limberg flap reconstruction represented 13.6% (n = 6) of the total, whereas in the group treated with crystallized phenol application women accounted for 21.6% (n = 8); the median ages of patients in the Flap group and the Phenol group were 25.4 ± 5.9 years and 26 ± 6.6 years, respectively. There were no significant differences in age, sex, infection, and presence of hematoma between the two groups. Length of hospital stay in the group treated with modified Limberg flap reconstruction was calculated as 1.25 ± 0.4 days, whereas patients in the group treated with crystallized phenol application were discharged immediately after the procedure. Thus, shorter length of hospital stay and no postoperative incision problems were noted in the group treated with crystallized phenol application (p < 0.001). Wound dehiscence was noted in seven patients (15.9%) in the group treated with modified Limberg flap reconstruction. Follow-up periods of patients in the Flap group and Phenol group were 17.9 ± 2.6 months and 16.5 ± 4.4 months, respectively, and no significant difference between the two groups was found in terms of body mass (24.2 ± 2.6 and 24.5 ± 2.7, respectively; Table 1).

| Variables | Operation type | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modified Limberg flap reconstruction n (%) | Crystallized phenol application n (%) | ||

| Participants | 44 | 37 | |

| Sex (F) | 6 (13.6) | 8 (21.6) | 0.344 |

| Age (y) | 25.4 ± 5.9 | 26 ± 6.6 | 0.627 |

| Recurrence rate | 3 (6.8) | 7 (18.9) | 0.173 |

| Total sinus number | 58 (55.2) | 47 (44.8) | 0.669 |

| Surgical site infection | 8 (18.1) | 4 (14.8) | 0.271 |

| Presence of hematoma | 8 (18.1) | 3 (8.1) | 0.214 |

| Wound dehiscence | 7 (15.9) | 0 | 0.011 |

| Length of stay in hospital (d) | 1.25 ± 0.4 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Follow-up (mo) | 17.9 ± 2.6 | 16.5 ± 4.4 | 0.88 |

| Body mass index | 24.2 ± 2.6 | 24.5 ± 2.7 | 0.554 |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

Recurrence was noted in three patients (6.8%) in the group treated with modified Limberg flap reconstruction and in seven patients (18.9%) in the group treated with one-time crystallized phenol application (Table 2). In these seven patients, four were cured completely after the second session, one was cured completely after the third session, and two could not be cured even after the fourth session.

| Normal | Recurrence rate | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (F) | 12 (16.9) | 2 (20) | 0.344 |

| Age (y) | 25.3 ± 6.1 | 28 ± 6.5 | 0.212 |

| Body mass index | 24.4 ± 2.6 | 26.9 ± 2.2 | 0.001 |

| Surgical site infection | 6 (8.5) | 6 (60) | <0.001 |

| Presence of hematoma | 8 (11.3) | 3 (30) | 0.132 |

| Dehiscence | 7 (9.9) | 0 | 0.588 |

| Length of stay in hospital (d) | 0.67 | 0.7 | 0.922 |

| Follow-up period (mo) | 17.1 ± 3.5 | 18.4 ± 3.4 | 0.307 |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

The success rate after multiple applications of crystallized phenol was found to be 94.5%. Even though the recurrence rate was higher in one-time crystallized phenol application, the difference between two groups was not statistically significant (p = 0.173).

Higher BMI (overweight, > 24.9 kg/m2) and surgical site infection were strongly correlated with recurrence rate (p < 0.001). Age, sex, length of stay in hospital, wound dehiscence, and presence of hematoma had no statistically significant effect on recurrence.

4. Discussion

There have been many treatment options for pilonidal sinus disease. Most of them are surgical procedures such as primary repair or secondary intention or flap reconstruction following excision.15 ; 16 In recent years, minimally invasive procedures have been suggested for the treatment of pilonidal sinus, including the application of crystallized phenol.17 Because the effective treatment of pilonidal disease should be simple, painless, cost-effective, performed with local anesthesia, and should not require hospitalization, a long time off work, and should have a low recurrence rate,18 the aim of the present study was to compare modified Limberg flap reconstruction (1 of the most convenient surgical procedures) with phenol application for the treatment of pilonidal sinus disease.

Phenol is a monosubstituted aromatic hydrocarbon that has acidic properties. It is in the state of crystalline solid at room temperature and turns to liquid form at higher temperatures. It can be used as liquid or in its crystallized form. Crystallized phenol has several advantages over the liquid form—it has better purity and handling properties than the liquid variant.19 The most common postoperative complications after liquid phenol treatment have been reported as skin and fat tissue necrosis due to high phenol concentration or high-pressure injection.20 Crystallized phenol becomes liquid at body temperature; it irritates the inner wall of the pilonidal sinus cavity, induces granulation and contraction, and then results in closure of the cavity. This procedure has important advantages as it does not require operating room conditions and can be performed under local anesthesia in an outpatient clinic. The procedure has been reported to be well tolerated and cost-effective, and to result in quicker return to daily activities.17 ; 20 Phenol treatment has several advantages: it is a minimally invasive and outpatient procedure, does not require hospital stay, and leaves a minimal postoperative incision scar. Therefore, this procedure has been suggested to increase the quality of life of patients with pilonidal disease.21 The only disadvantage of this technique is its higher recurrence rates when compared with those obtained with flap surgery.22 However, most of the high recurrence data of phenol treatment have been derived from one application; subsequent phenol applications could be easily done and improve success rate.22

The present study was performed in order to compare crystallized phenol application and modified Limberg flap reconstruction in terms of age, sex, length of hospital stay, complications, infection, and recurrence rates, as well as the recurrence rate in patients with pilonidal sinus disease after one-time crystallized phenol application was found to have a higher rate compared with that in patients who underwent modified Limberg flap reconstruction. However, the difference was not statistically significant. Crystallized phenol application was repeated in patients with recurrence because it was previously reported that the rate of success increased with multiple phenol applications.17 ; 21 We recorded a success rate of 94.5%, with repeated applications.

There are several factors affecting the recurrence rate in pilonidal sinus disease. The recurrence rate of pilonidal sinus varies depending on the treatment method and the follow-up period. It has been previously suggested that the success rate for phenol applications was poor even after multiple applications in patients having more than three sinus orifices or a history of pilonidal cyst abscess drainage.23 In our study, recurrence was observed in patients with multiple sinus orifices even after repeated phenol applications, in agreement with this report. Surgical site infection and hematoma were also suggested to increase the recurrence rate in pilonidal sinus disease,24; 25 ; 26 whereas the correlation between BMI and recurrence rate is controversial.25 ; 27 In the present study, surgical site infection and increased BMI were found to be correlated with the recurrence rate in both study groups. Although the occurrence rates of infection and hematoma were lower in patients treated with phenol application, the difference between the groups was found to be statistically insignificant. Also, the rates of wound dehiscence and the length of stay in hospital were significantly decreased in the group treated with phenol application. Our data support the findings previously reported in several studies.14; 21 ; 22

Recurrent pilonidal sinus disease that occurs after surgery is usually treated with surgical techniques, whereas recurrence after crystallized phenol application is treated with minimally invasive techniques. This is the advantage of phenol application. It was also previously shown that phenol application performed to treat patients with recurrence after the surgery increased the success rate.26

Flap treatment of pilonidal sinus disease is mostly performed under general or spinal anesthesia, whereas in crystallized phenol application local anesthetics are used. Spinal anesthesia is known as an invasive process with complications such as headaches and urinary retention, and it is more costly than local anesthesia. Additionally it requires patient monitoring after the procedure.28 In patients who underwent crystallized phenol treatment, local anesthesia was used and these patients were discharged on the same day.

A large scar was observed after modified Limberg flap reconstruction, which generally causes an unpleasant esthetic look, whereas the scar left following phenol application is almost unremarkable (Figure 3).

|

|

|

Figure 3. Postoperative appearance of the application site. Crystallized phenol application leaves a relatively unremarkable scar. |

There are several studies comparing crystallized phenol application as a treatment option for pilonidal sinus disease with other methods including the flap procedure. Modified Limberg flap is a relatively new procedure, and it has several advantages over standard Limberg flap.9

The major aim of the flap surgery in pilonidal sinus is to prevent recurrence by excising maximum tissue as needed and lateralizing or flattening the midline. Although the Limberg flap procedure is an efficient surgical option to treat pilonidal sinus, recurrence was reported in the lower pole of the flap, as it stays intact within the intergluteal sulcus. Yet, the modified Limberg flap procedure, in which rhomboid excision is tailored asymmetrically to place the flap laterally, eliminates recurrence, which usually occurs in the inferior part of the midline.7

To our knowledge, our study is the first to compare crystallized phenol application with modified Limberg flap in the treatment of pilonidal sinus disease. Although this study is retrospective and the number of cases is relatively small, our results clearly showed that crystallized phenol is superior to modified Limberg flap. We are currently running a prospective study to add more data to this subject.

In summary, phenol treatment appears to be a convenient treatment of choice for pilonidal sinus disease because of its many advantages such as being a minimally invasive procedure, performed under local anesthesia, higher success rate after multiple applications, and decreased length of stay in hospital with minimal surgical scar tissue formation.

References

- 1 S. Chintapatla, N. Safarani, S. Kumar, N. Haboubi; Sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus: historical review, pathological insight and surgical options; Tech Coloproctol, 7 (2003), pp. 3–8

- 2 J. Bascom; Pilonidal disease: origin from follicles of hairs and results of follicle removal as treatment; Surgery, 87 (1980), pp. 567–572

- 3 T. Ertan, M. Koc, E. Gocmen, A.K. Aslar, M. Keskek, M. Kilic; Does technique alter quality of life after pilonidal sinus surgery?; Am J Surg, 190 (2005), pp. 388–392

- 4 T. Mahdy; Surgical treatment of the pilonidal disease: primary closure or flap reconstruction after excision; Dis Colon Rectum, 51 (2008), pp. 1816–1822

- 5 H. Ozdemir, Z. Unal Ozdemir, I. Tayfun Sahiner, M. Senol; Whole natal cleft excision and flap: an alternative surgical method in extensive sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease; Acta Chir Belg, 114 (2014), pp. 266–270

- 6 S. Petersen, R. Koch, S. Stelzner, T.P. Wendlandt, K. Ludwig; Primary closure techniques in chronic pilonidal sinus: a survey of the results of different surgical approaches; Dis Colon Rectum, 45 (2002), pp. 1458–1467

- 7 B.B. Mentes, S. Leventoglu, A. Cihan, E. Tatlicioglu, M. Akin, M. Oguz; Modified Limberg transposition flap for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus; Surg Today, 34 (2004), pp. 419–423

- 8 M.Z. Sabuncuoglu, A. Sabuncuoglu, O. Dandin, et al.; Eyedrop-shaped, modified Limberg transposition flap in the treatment of pilonidal sinus disease; Asian J Surg, 38 (2015), pp. 161–167

- 9 M. Akin, S. Leventoglu, B.B. Mentes, et al.; Comparison of the classic Limberg flap and modified Limberg flap in the treatment of pilonidal sinus disease: a retrospective analysis of 416 patients; Surg Today, 40 (2010), pp. 757–762

- 10 M. Sit, G. Aktas, E.E. Yilmaz; Comparison of the three surgical flap techniques in pilonidal sinus surgery; Am Surg, 79 (2013), pp. 1263–1268

- 11 T. Karaca; Yoldaş O, Bilgin BÇ, Ozer S, Yoldaş S, Karaca NG. Comparison of short-term results of modified Karydakis flap and modified Limberg flap for pilonidal sinus surgery; Int J Surg, 10 (2012), pp. 601–606

- 12 A. Isik, R. Eryılmaz, I. Okan, et al.; The use of fibrin glue without surgery in the treatment of pilonidal sinus disease; Int J Clin Exp Med, 7 (2014), pp. 1047–1051

- 13 K. Akan, D. Tihan, U. Duman, Y. Ozgun, F. Erol, M. Polat; Comparison of surgical Limberg flap technique and crystallized phenol application in the treatment of pilonidal sinus disease: a retrospective study; Ulus Cerrahi Derg, 29 (2013), pp. 162–166

- 14 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; The Practical Guide: Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults; National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. NIH Publication 00-4084 (2000)

- 15 A.L. Gidwani, K. Murugan, A. Nasir, R. Brown; Incise and lay open: an effective procedure for coccygeal pilonidal sinus disease; Ir J Med Sci, 179 (2010), pp. 207–210

- 16 H. Aydede, Y. Erhan, A. Sakarya, Y. Kumkumoglu; Comparison of three methods in surgical treatment of pilonidal disease; ANZ J Surg, 71 (2001), pp. 362–364

- 17 O. Dogru, C. Camci, E. Aygen, M. Girgin, O. Topuz; Pilonidal sinus treated with crystallized phenol: an 8 year experience; Dis Colon Rectum, 47 (2004), pp. 1934–1938

- 18 M. Girgin, B.H. Kanat, R. Ayten, et al.; Minimally invasive treatment of pilonidal disease: crystallized phenol and laser depilation; Int Surg, 97 (2012), pp. 288–292

- 19 I. Sakcak, F.M. Avsar, E. Cosgun; Comparison of the application of low concentration and 80% phenol solution in pilonidal sinus disease; JRSM Short Rep, 1 (2010), p. 5

- 20 C. Kayaalp, A. Olmez, C. Aydin, T. Piskin, L. Kahraman; Investigation of a one-time phenol application for pilonidal disease; Med Princ Pract, 19 (2010), pp. 212–215

- 21 O. Topuz, S. Sözen, M. Tükenmez, S. Topuz, U.E. Vurdem; Crystallized phenol treatment of pilonidal disease improves quality of life; Indian J Surg, 76 (2014), pp. 81–84

- 22 M. Girgin, B.H. Kanat; The results of a one-time crystallized phenol application for pilonidal sinus disease; Indian J Surg, 76 (2014), pp. 17–20

- 23 A. Dag, T. Colak, O. Turkmenoglu, A. Sozutek, R. Gundogdu; Phenol procedure for pilonidal sinus disease and risk factors for treatment failure; Surgery, 151 (2012), pp. 113–117

- 24 M. Ardelt, Y. Dittmar, R. Kocijan, et al.; Microbiology of the infected recurrent sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus; Int Wound J (2014) http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12274

- 25 A. Cubukcu, N.N. Gonullu, M. Paksoy, A. Alponat, M. Kuru, O. Ozbay; The role of obesity on the recurrence of pilonidal sinus disease in patients, who were treated by excision and Limberg flap transposition; Int J Colorectal Dis, 15 (2000), pp. 173–175

- 26 E. Aygen, K. Arslan, O. Dogru, M. Basbug, C. Camci; Crystallized phenol in nonoperative treatment of previously operated, recurrent pilonidal disease; Dis Colon Rectum, 53 (2010), pp. 932–935

- 27 H. Sievert, T. Evers, E. Matevossian, C. Hoenemann, S. Hoffmann, D. Doll; The influence of lifestyle (smoking and body mass index) on wound healing and long-term recurrence rate in 534 primary pilonidal sinus patients; Int J Colorectal Dis, 28 (2013), pp. 1555–1562

- 28 H. Sungurtekin, U. Sungurtekin, E. Erdem; Local anesthesia and midazolam versus spinal anesthesia in ambulatory pilonidal surgery; J Clin Anesth, 15 (2003), pp. 201–205

Document information

Published on 26/05/17

Submitted on 26/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?